5 minute read

Intentional Architecture

Marcelyn Gow

In “Changing my mind: Occasional Essay’s”; Zadie Smith Informs readers of her experiences throughout her career. She describes how her opinions have shifted since the beginning of her career as she was mainly a reader, and after moving onto the present time, as now she is mainly an author. The premise for this shift in perspective comes courtesy of Roland Barthes, and Vladimir Nabokov respectively. Smith compares, and contrasts Barthes’ “Death of the Author”, versus Nabokov’s “Good readers and good writers”. In essence, Smith found herself aligning with Barthes, at the beginning of her career, and Nabokov at the current point in her career. While Smith’s text remains neutral on the subject matter, it does leave the reader questioning what is perhaps the correct argument to side with. This argument could be applied to all creative fields, architecture being one of them, where the same argument runs deep and poses the same question. What is the relationship between the designer, and the end user? On the other hand, is all architecture built and designed in the Nabokov style of thinking?

Advertisement

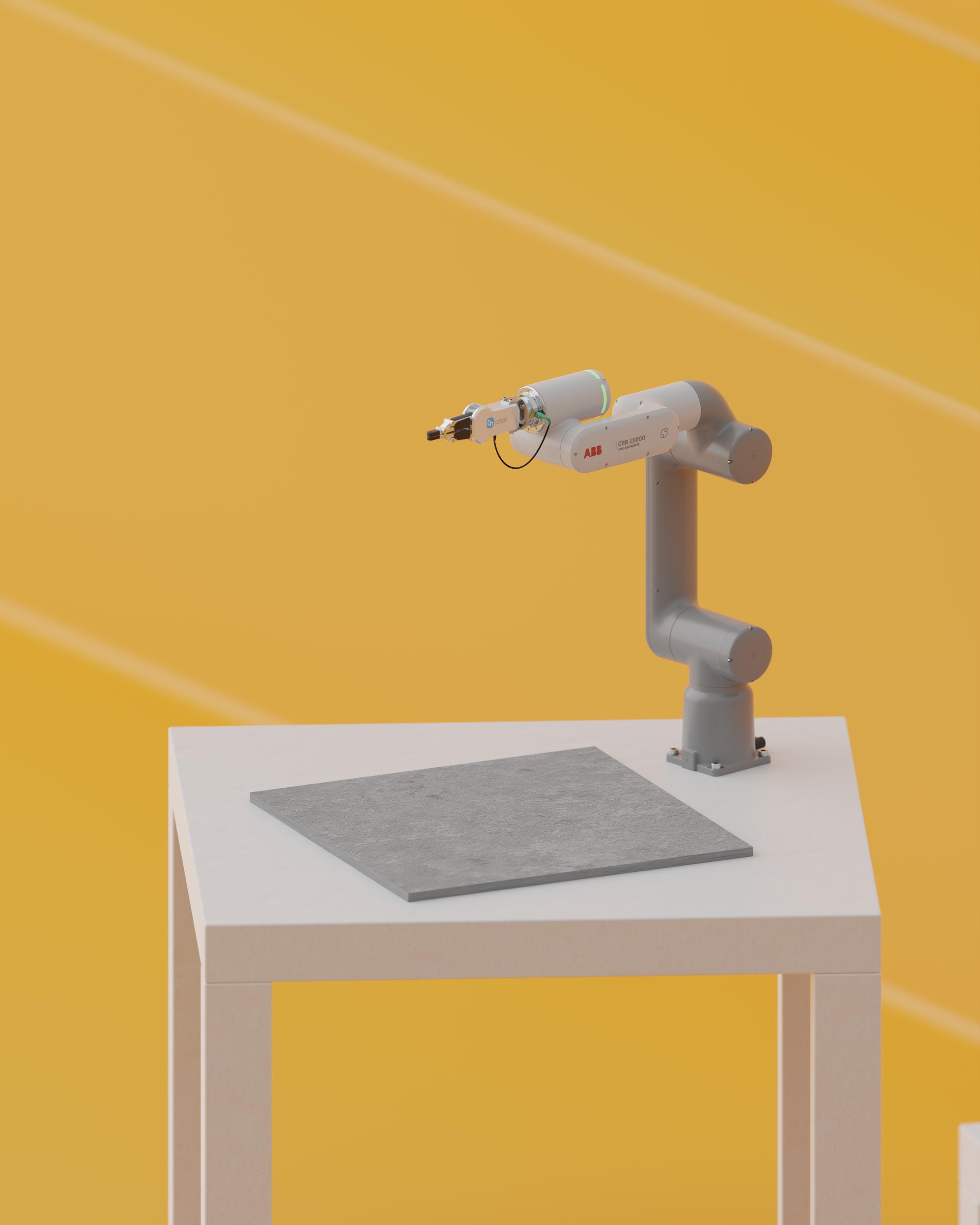

The topic of voice in architecture is incredibly relevant in today’s day and age, simply because as emerging technologies, the likes of AI, allow for the rethinking of the role of designers in the contemporary workflow. As a result, it is imperative to define the role of the “authors” of a particular piece of architecture.

It can be argued that all architecture is erected with the intentional ‘Nabokov’ style of thinking as every design decision is intentional, whether be it consciously, or unconsciously. In Smith’s text, both arguments are pitted against one another. To dive deeply, Barthes’ argument stems from an anti-intentional background meaning that a text “is not a line of words releasing a single ‘theological’ meaning”1, but rather that the meaning of the text is up to the reader to formulate. Meanwhile, Nabokov’s argument is rooted in the concept that the reader must attempt deciphering and understanding the ultimate intent of the text, surrendering himself to the world the writer depicts. However, a shift of perspective shows that the arguments fall under the same scope of thought. The shift in perspective argues that Nabokov’s argument of deciphering is the overarching argument, to which Barthes’ argument of disentangling falls under. In essence, even the disentangling act that Barthes is urging for, is granted by the deciphering act of Nabokov. Ultimately, the disentangling act is a form of deciphering that an author orchestrates, but intentionally broadens the borders of control.

The disentangling act that Barthes refers to relies on vagueness to be successful. Vagueness, as Michelle Chang describes it, is when “discrepancies arise between the precise meanings of words, vision, and images”2. In this case, specifically, the disentangling act relies upon the author, or designer to set up a vague borderline case, where the boundaries of a case lack specificity. This intentional lack of specificity is the prerequisite for the Barthes argument to fall under the Nabokov argument. Moreover, it could be an author intends to allow the reader to begin disentangling, which in itself is a deciphering act since it was the author’s intention for the reader to set on his own journey of thoughts, which is enabled by the vagueness that was intentionally placed.3 It is important to highlight that most bodies of text are usually not one or the other, but rather a weave of both alternating between each other. Architecturally speaking this happens often. Most buildings are not Euclidean in the way they are planned, meaning there are portions of a building that are meant to be deciphered very easily, and some that are meant to be explored, and disentangled within certain limits that are placed by the designer of the physical space. It is the architect’s role in this case to guide users on a journey, and it is the architect that dictates when it is permissible for the user to decipher, and when it is time for a user to set off on an untangling journey. Moreover, the very best designers, are the ones that are able to employ these strategies, allowing users to go in between both states as they experience a certain piece of architecture. The Jewish Museum in berlin is a great building to illustrate how the two arguments of Nabokov, and Barthes are building upon each other. The Jewish Museum was designed by Daniel Libeskind, plotted throughout the museum, are plenty of moments where users are required to decipher and others to disentangle. To begin with, the exterior facades of the building are very intentionally vague, and non-memorable, the height, and the proportions are much the same (Figure 1). This design is very intentionally vague in that, playing a secondary role to the surrounding baroque architecture (Figure 2), it does not hint at what the contents of the building could be. That is precisely why an act of disentangling is required. While it may seem accidental, it is not at all. The designer invites the user to indulge themselves in an act of free thinking. Nevertheless, it is important to highlight that the designer orchestrated the entire progression. Libeskind did have the opportunity to create a façade system that is more expressive of what the building beholds, which would more “classically” follow Nabokov’s argument, yet he deliberately decides to leave room for interpretation, thereby engaging a user in a multitude of experiences. Moving towards the interior, and the end of the exhibition guests enter a narrow, dark, grey concrete room with a narrow sliver of a skylight that allows sunrays to enter the space (Figure 3). This is a clear example where Nabokov’s argument is being classically used. Libeskind intentionally creates a very detailed rich space for users to begin to decipher the meaning behind the light. Users are forced to think much like the designer himself, recreating the journey that the designer undertook to reach that particular end product.4

Highlighting intentionality is a key aspect in the discourse of architecture. Architecture is always intentional, which is an important statement amid the current developing nature of technology within architectural design. Breakthroughs in form finding, and image-making technology regularly question the role of designers in all creative fields. Nabokov’s argument proves that all decisions made by designers are intentional because it is the intentionality that cements the idea that a designer is always the genesis of a design no matter what tool is used to produce an outcome. It is that human ownership of the design, that breathes the sentient qualities into the non-sentient elements of architecture, which ultimately translates into more humanistic experiences for end users.

Bibliography

Berlin Jüdisches Museum Und Der Libeskind-Bau (Cropped).Jpg. n.d. https://upload. wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/a/a5/Berlin_J%C3%BCdisches_Museum_und_der_ Libeskind-Bau_%28cropped%29.jpg.

Chang, Michelle. “Something Vague.” Essay. In Log 44, 103–13. Anyone Corporation, n.d.

“The Death of the Author.” Roland Barthes, 1967, 74–88. https://doi. org/10.4324/9780203634424-13.

Foucault, Michel. What Is an Author?, 1969.

Introduction to Nabokov (as Critic). YouTube. YouTube, 2017. https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=ugsgW0PTRVs.

Jewish Museum Berlin. n.d. https://libeskind.com/work/jewish-museum-berlin/.

Jewish Museum. March 21, 2022. Berlin Attractions. https://www.berlin.de/en/attractionsand-sights/3560999-3104052-jewish-museum.en.html.

LaValley, Michael. “Architecture and Ego: The Architect’s Unique Struggle With ‘Good’ Design.” Architizer. Accessed October 2, 2022. https://architizer.com/blog/practice/ details/architecture-and-ego/.

Libeskind, Daniel. “She Has Brought to Architectural Photography a Mysterious Dimension”: Daniel Libeskind on Hélène Binet. December 16, 2021. https://www.royalacademy.org.uk/ article/ra-magazine-daniel-libeskind-helene-binet.

Loomans, Taz. “DEAR ARCHITECTS, PLEASE STOP TRYING TO IMPRESS OTHER ARCHITECTS AND JUST BE MORE HUMAN.” Web log. Blooming Rock (blog), November 27, 2012. DEAR ARCHITECTS, PLEASE STOP TRYING TO IMPRESS OTHER ARCHITECTS AND JUST BE MORE HUMAN.

Roland Barthes’ Death of the Author Explained | Tom Nicholas. YouTube. YouTube, 2019. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=B9iMgtfp484.

Roland Barthes’s “Death of the Author,” Explained. YouTube. YouTube, 2022. https://www. youtube.com/watch?v=JcNoDMSBHP4.

Smith, Zadie. “Rereading Barthes and Nabokov.” Essay. In Changing My Mind Occasional Essays. London: Penguin, 2011.

Wimsatt, W., and Monroe Beardsley. “11. ‘The Intentional Fallacy’.” Authorship, 1954, 90–100. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781474465519-013.