7 minute read

50th Anniversary SS Great Britain by John Greeves

50th Anniversary of the SS Great Britain

Advertisement

by John Greeves

50th anniversary of the return of the world’s first great ocean liner- SS Great Britain.

Fifty years ago the spectacular return of Brunel’s SS Great Britain being towed up the River Avon and under the Clifton Suspension Bridge was greeted by thousands of spectators that lined the banks of the river to catch a glimpse of this famous hull before she was finally manoeuvred into the Great Western Dry Dock for the final time. The ship was launched on 19 July 1843 and was a technical marvel designed far ahead of its time, being the first ocean going ship built of iron and the first large vessel fitted with a screw propeller, a double bottom and water tight bulk heads. She is often recognised as the greatgreat grandmother for all modern ships.

In 1882, her propelling machinery was removed and she became a ‘Fully Rigged Sailing Vessel’ but unfortunately ran into a fierce storm off Cape Horn with a cargo of coal. Badly damaged she put into Port Stanley in the Falkland Islands. Her repair cost was considered uneconomical so she was purchased locally and used as a storage hulk in Port Stanley for many years.

Later in 1936 the Great Britain was towed to Sparrow Cove by a Whale Catcher and small tug and she was allowed to sink in shallow water.

This could have been the last we heard of the great ship, had it not been for the pioneering effort of Dr Ewan Corlett that involved salvage crews achieving a number of awe-inspiring ‘firsts.’ These included positioning the largest ship ever re-floated onto a pontoon then undertaking the longest ever salvage tow of this kind from the Falkland

Islands to Bristol; an 8,000-mile journey taking 87 days

which has never been beaten. Funding was given by the English philanthropist Sir Jack Hayward who gave £150,000 to fund the ship’s rescue and bring her back to Bristol.

The operation on paper seemed straight-forward, patch up the holes, pump out the water, let the ship float, then manoeuvre her over a submersible pontoon before towing her home. The reality was to prove something else; it was an immensely difficult challenge that was going to take tremendous skill and resolve and a large measure of good luck.

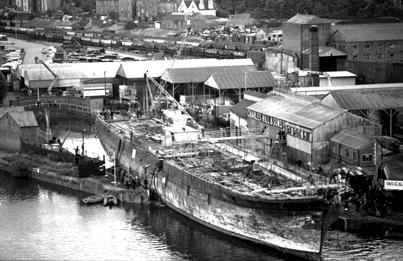

The operation involved two associated companies. The Southampton salvage company of Risdon Beazley Marine Ltd whose job was to re-float this 2,000 ton hull just long enough over the submerged pontoon (Mulus 3). The pontoon would then be raised with the SS Great Britain in place. The Hamburg Salvage company of Ulrich Harms would then take over and undertake the long tow home.

Four salvage divers were hand-picked by Bill O’Neil, (senior salvage officer of Risdon Beazley) each with their own speciality. Falklands born Lyle CraigieHalkett, was one of the divers selected for his local knowledge and specialized in diving and rigging.

When the team arrived in Sparrow Cove in the Falklands in March 1970, they found the condition of the SS Great Britain much worse than anyone had anticipated. Lyle recalls: “The main decking where it existed was completely rotten; the Tween decks had no decking at all so placing any equipment on it such as pumps was very hazardous. Inside the bottom of the ship there was at least a couple of metres of mud and debris that had accumulated over the years. The most obvious and ominous structural damage was a huge split in the Starboard side. On diving and digging a tunnel under the ship’s hull we found the split extended right round the Bilge also the Garboard Strake, and only stopped at the keel. If this wasn’t enough, the hull was also riddled with hundreds of wastage holes of varying sizes.”

Lyle and the other divers worked hours on end, in dark, muddy and freezing conditions patching the multitude of holes. They used 3 ply, rubber strips to make seals and in some places oakum and tallow as used for many years. Meanwhile an appeal went out on local radio for mattresses. The enormous crack was plugged with donated mattresses which would pinch together once the ship was re-floated. “We stuffed the mattresses from the keel to well above where the Salvage Officer said the maximum draft should be. It was quite hard going, pulling the mattresses under the ship, as it took ages before the air would escape particularly with a few mattresses that were of the rubber foam variety. We put plywood over the mattresses, and similar to the holes in the ship’s side, we used hook bolts to hold everything in position,” Lyle says.

After two weeks of meticulous work taking down the masts, and patching up holes it was finally time to see if the SS Great Britain would float. On Sunday 5th April the salvage team started to pump the hull out while the Varius 2 (the powerful German stern trawler) manoeuvred the pontoon (Mulus 3) into deeper water and was gently submerged onto the seabed. Pumping began, taking many hours before the salvage team could see any difference in the water level. The usual blocked suction inlets occurred, but the most exhausting task was shifting the large pumps mounted on and a multitude of rigging had to be used to reposition them. When the water did start to subside numerous new holes appeared that required patching. A non-stop 9-10 gale was blowing during the whole of this operation making the job of further patching even more difficult. Lyle recalls the event: “We had been working very hard, and had continued without sleep for two nights or even a decent meal. It was laborious to say the least to get out of our diving suits and scramble on the Varius 2 to a sit down meal, so the five of us made do with sandwiches and as much coffee as they could bring us from the ship.”

The water level had gone down considerably and the Great Britain should have been afloat but refused to move. Lyle and his fellow divers in desperation decided to add one final patch after high water. Then they went off for a well-earned shower and breakfast. Meanwhile, assisted by the non-stop force 9-10 gale buffeting, the ship began to rock slightly, bubbles appeared indicating the

suction to

the seabed had broken and she was now afloat. The jubilant team left their breakfast and rushed to see the ship afloat once again after 37 years. It was now the task for the German crew to get the SS Great Britain onto the submerged wheels. There was no firm deck to pull them along

pontoon.

During the subsequent days, the ship was secured. On 24th April 1970, SS Great Britain began an 87- day journey back to Bristol. Towed by the Varius 2 with the SS Great Britain’s hull firmly secure on the Mulus 3 pontoon, the strange flotilla made its way through 8000 miles of the Atlantic back to its home city of Bristol to tumultuous acclaim and applause.

The danger and difficulties of this salvage cannot be underestimated. While many received the accolades on the quay side and in the press, Lyle believes that Bill O’Neil, The Salvage Officer in overall charge was never given the recognition he truly deserved for the salvage of the SS Great Britain, and was not even introduced to the Duke of Edinburgh. Bill O’Neil was a modest and a very shy man, plus no stranger to the Falklands being a survivor from H.M.S. Sheffield “The Battle of The River Plate”. Lyle believes had it not been for him, the SS Great Britain would have been lost to the Nation forever.

Link: https://www.ssgreatbritain.org/

John Greeves originally hails from Lincolnshire. He believes in the power of poetry and writing to change people’s lives and the need for language to move and connect people to the modern world. Since retiring from Cardiff University, Greeves works as a freelance journalist who's interested in an eclectic range of topics.