ANA MORENA PINHO

+351 912 684 862

anamorenapinho@hotmail.com

ABOUT ME:

Newly graduated architect, dedicated and organized, with experience in group work and creative problem solving. My studies so far have allowed me to obtain foundations in social architecture and bioconstruction. I am interested in the areas of landscape and urban design, and eager to learn new softwares and skills. Overall, my main goal is to help people through architecture.

WORK EXPERIENCE:

D.Architects

Model maker dec 2022 - feb 2023

• Created process and presentation models, in varying project scales.

Pedro Brígida Arquitetos

Intern aug 2020 - sept 2020

• Developed drawings for the preliminary studies of a competition project.

Sambou Toura Drame

School Competition

Participant sept 2019 - nov 2019

• Open competition, for which a primary school was designed. The project focused on using local materials, such as clay bricks, tires, wood beams and metal roofing sheets.

GeraBrasil Arquitetura e Consultoria

Intern aug 2019

• Worked in drawings and panels for the Casa das Birutas project, used for the Tomie Ohtake Institute AkzoNobel Award.

EDUCATION:

Integrated Masters in Architecture University of Coimbra | 2017 - 2022

• Developed a Master Thesis titled “Empowerment in Architecture: Community Center for refugees in Fontaínhas”.

LANGUAGES:

• Portuguese (native)

• English (advanced)

PERSONAL SKILLS:

• Proactive

• Team worker

• Creative

• Resourceful

OTHER ACCOMPLISHMENTS AND EXPERIENCES:

TAPE: Faculty’s best project Exhibition

2019

• Participated with my 1st year project.

TIBÁ-RIO: Workshop in bamboo construction may 2017

Scounting Union of Brazil: Member (scout) 2006 - 2015

• Learned how to work with knots, joints, and bamboo structures.

TECHNICAL SKILLS:

Archicad Illustrator Indesign Photoshop AutocadARCHITECTURE OF EMPOWERMENT: COMMUNITY CENTER FOR REFUGEES IN FONTAÍNHAS

INDIVIDUAL MASTER THESIS

This thesis project, developed in the Project Studio O estrangeiro from the University of Coimbra, seeks to understand how marginalized groups can be better integrated in cities. The research, in its theoretical aspect, focused on the empowerment of such groups, through the formation of a support community, the democratization of education and culture, and the occupation of central spaces in the city. In its practical aspect, the research materialized in the creation of a new public equipment: a Community Center for refugees in the region of Fontaínhas, in Porto, Portugal.

Within the municipality of Porto, the Fontaínhas region is in a peculiar condition –close to the historic center, but disconnected from transport, commerce and service networks. The first step in establishing these connections was, therefore, to propose a urban revitalization, with the intention of demarginalizing the region by improving public spaces and stimulating the influx of people and investments to it. In the process of analyzing Fontaínhas, some characteristics that form it’s image were identified, in addition to strengths and opportunities.

Fontaínhas organizes itself around three main nodes: the area of the Old Rest Home and the Fontaínhas Lane (node 1); the Alegria Square (node 2); and the Padre Baltasar Guedes Square (node 3). These three areas are important meeting points of roads and people, and are associated with notable facilities (landmarks). Among these three sites, the 1st one was chosen as the location for the new Community Center, based on its great visibility and connections to important squares and avenues.

DouroRiver

Mapping of Fontaínhas current conditions

NODE 3

NODE 1

Within this first node, the Old Rest Home building was chosen to house the Community Center, with the intervention being done through a rehabilitation project.

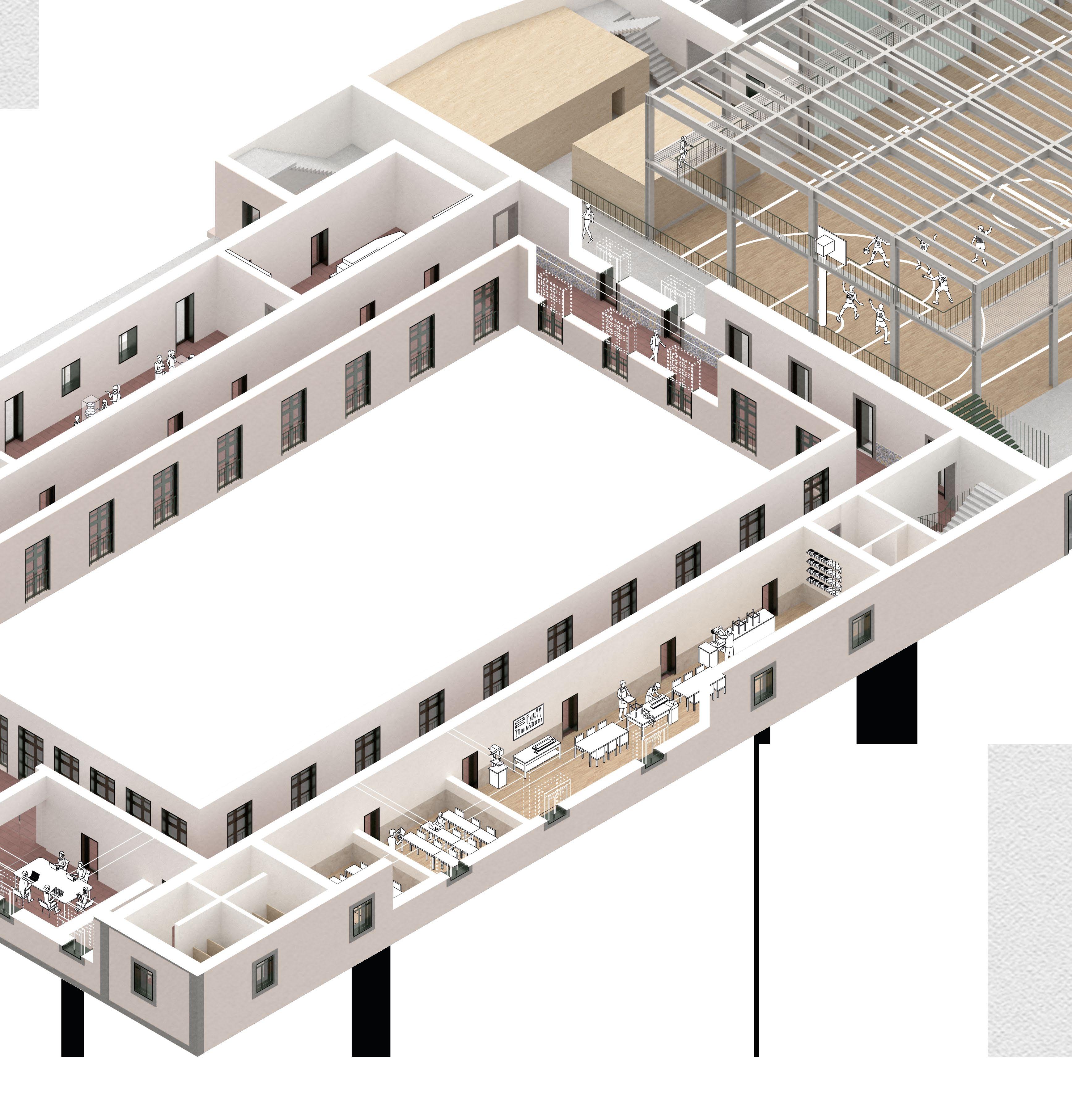

Intended to be a space for creating connections and strengthening the local community, the Center houses cultural, sports, training, and educational programs. To the side, you can see the organization chart of the initial distribution of the programs, which given the preexisting structure of the building, are arranged in its four wings built around a central courtyard.

Old Rest Home of Fontaínhas

- originally built in 1796; - passed through different uses until it was closed in 2018 (currently abandoned);

- current structure made of masonry walls and wooden and concrete slabs;

Elementos preexistentes Elementos novos

O prédio escolhido para abrigar este novo programa foi o antigo asilo da mendicidade do Porto. Ele é um edifício com grande impacto na paisagem urbana, que se encontra num nó importante, próximo da ponte do infante, da alameda das Fontaínhas e de um futuro parque. É um prédio com história e que faz parte da identidade do local, para o qual será elaborado um projeto de reabilitação. Em relação a disposição interna do edifício, algumas paredes serão retiradas e outras feitas para abrigar os novos programas do centro comunitário, mais especificamente: áreas expositivas, café, salas de aula, salas polivalentes, zonas de coworking, auditório, estacionamento e área desportiva, que pelo seu tamanho foi colocada em um novo volume, construído de raiz.

O prédio escolhido para abrigar este novo programa foi o antigo asilo da mendicidade do Porto. Ele é um edifício com grande impacto na paisagem urbana, que se encontra num nó importante, próximo da ponte do infante, da alameda das Fontaínhas e de um futuro parque. É um prédio com história e que faz parte da identidade do local, para o qual será elaborado um projeto de reabilitação. Em relação a disposição interna do edifício, algumas paredes serão retiradas e outras feitas para abrigar os novos programas do centro comunitário, mais especificamente: áreas expositivas, café, salas de aula, salas polivalentes, zonas de coworking, auditório, estacionamento e área desportiva, que pelo seu tamanho foi colocada em um novo volume, construído de raiz.

O motivo construtivo deste novo volume surge de uma intenção criada ainda durante a fase da intervenção urbana, na qual novas construções foram feitas em estrutura metálica, para referenciar a ponte dona maria pia, que conecta as Fontaínhas à Gaia. Mantendo esse motivo, o novo volume foi feito na forma de uma uma gaiola metálica que entra na preexistência como uma gaveta. Essa estrutura de pilares e vigas entra até certo ponto da preexistência de modo que o contraste entre o novo e o antigo fique claro não só por fora do edifício, mas também por dentro.

O motivo construtivo deste novo volume surge de uma intenção criada ainda durante a fase da intervenção urbana, na qual novas construções foram feitas em estrutura metálica, para referenciar a ponte dona maria pia, que conecta as Fontaínhas à Gaia. Mantendo esse motivo, o novo volume foi feito na forma de uma uma gaiola metálica que entra na preexistência como uma gaveta. Essa estrutura de pilares e vigas entra até certo ponto da preexistência de modo que o contraste entre o novo e o antigo fique claro não só por fora do edifício, mas também por dentro.

Seeking to maintain the original structure of the building, the programs were inserted inside their rooms with only a few changes to the interior walls. The only exception was the sports area, whose court required the creation of a new volume, due to its dimensions. To contrast with the solid and traditional character of the original construction, the new volume was made with metal beams and columns, that were inserted into the preexisting building like a drawer.

Original plan of the building (1st floor)

New plan for the Community Center (1st floor)

Communal kitchen

Greenhouse

Exhibition area

Café and restaurant

Atelier

Sports court

Communal kitchen

Greenhouse

Exhibition area

Café and restaurant

Atelier

Sports court

stone masonry walls, plastered, and slabs with wooden beams

CONSTRUCTIVE SYSTEMS

masonry walls and composite floor with steel deck

1. Compacted earth

2. gravel

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

15.

16.

columns and beams in H and I metal profiles

concrete walls and slabs

17. Preexisting stone lintel

18. Gypsum plasterboard 1,25cm

19. Mineral wool insulation 9cm

20. Wood ring beam 10 x 20cm JULAR

21. Joist 15 x 20cm JULAR

22. Rafter 15 x 25cm JULAR

23. Insulation beams

24. Wooden backing board

25. Vapor barrier

26. Wood beam

27. Counter batten

28. Batten

29. Marseille tile

30. Barrel tile

31. Gutter

32.stone door frame

33. HEB 300 steel column FERRO

34. Channel glass Bendheim

SAMBOU TOURA DRAME SCHOOL

GROUP COMPETITION PROJECT

The following work is a proposal for the requalification of the Sambou Toura Drame Elementary School, in the city of Marsassoum, Senegal. The competition brief emphasized the importance of using locally sourced materials and easily replicable construction techniques, so the residents of Marsassoum can learn and apply them on future projects.

The plot has a Moraceae tree in the center (from the fig tree family), which has big leaves that provides shade. In order to maintain the area around the tree as a space of rest and communion, the buildings made for the proposal were placed at the limits of the plot, creating a courtyard, with the tree as its focal point. From this, two openings were made in the built volume: one for a vegetable garden and corral, and another for planting larger trees. water and food are not widely available in the region, and with these features the school can produce its own food, and simultaneously teach the students how to be self-sufficient.

The covered area of the proposal accommodates classrooms, a principal’s office, a teachers’ room, a canteen, a library, and a composting toilet. The spatial organization was the result of the intention to relate the library to the corral and garden, manifesting a relationship between teaching areas that are not necessarily classrooms, and to relate the canteen to an outside area, allowing the appropriation of this space if necessary.

ZINC ROOF

BAMBOO RODS

WODDEN ROOF STRUCTURE

BAMBOO COLUMNS

JALI BRICK WALL

TIRE FOUNDATION

In order to create a connection between interior and exterior, two types of openings were made in the facades: one in the adobe brick wall and the other between the wall and the roof, with a sequence of bamboos, which allow light and ventilation to enter. The sloping roof to the patio allows the harvest of rainwater, which goes through the gutters to the cistern, passing through a sand filter and eliminating any impurities, making the water ready for consumption. This reservoir has two manual water pumps for use in the toilet, in the canteen and in the garden irrigation. The cistern also has an inspection box that is accessed through the bathroom floor, and its depth can be changed in the future, if a survey of the soil shows that it is necessary.

The dry toilet transforms the excrement into compost and doesn’t require the use of water. With this system, the sewage does not pollute the soil or the river, and generates fertilizer that can be used in the garden, or donated to Marsassoum residents.

ESSAYS

The following essays are two subchapters of my Master Thesis, in which I reference works by Foucault and Ismail Serageldin to talk about the relation between architecture and power. I chose to include them in my portfolio because they sum up well the theoretical basis of my research, and they were my favorite parts to write.

POWER AND REFUGEES

Power, noun, is a concept for which there is no single definition. Theorizing the idea of power in a universal way is impossible, since there is no consensus in the academy about what power is, or how it manifests itself (Foucault, 2000 [1982]). Power relations permeate all spheres of society, and their imbalances generate the social hierarchies from which inequalities are born. To analyze power relations and their influences on sociospatial inequality, this section of the paper will draw on Michel Foucault’s reflections on power and the subject, Maria Cristina Santinho’s1 research on the situation of refugees in Europe, and Jorge2 e Aline Rocha’s3 studies and interpretations of some concepts posited by Foucault.

Thought of as an expression of will, or just having that possibility, power is not an inherently good or bad “potency” - after all, nothing is. It is just a capacity. And social inequality is a convenient product for the maintenance of power relations that dictate what an individual is and how they should act within a society. In this context, Foucault states that the study of power, in its lack of definition, should always be accompanied by a spatial and temporal contextualization to really understand how it can be analyzed.

In the case of this dissertation, the context of the study of power relations is both the current Fontaínhas region, with its underutilized spaces and marginal character, and the Fontaínhas of the future, post urban revitalization plan and with a new group of immigrant residents looking for their place. And then a first question is posed: how can the architect help marginalized groups find “their place”?

Foucault says that the notion of individuality that

1 Maria Cristina Santinho is a researcher at the Center for Research and Studies in Sociology, Research Network in Anthropology, ISCTE - Instituto Universitário de Lisboa, Portugal.

2 Jorge Alberto da Costa Rocha is a professor at the State University of Feira de Santana (UEFS), PhD in Teaching, Philosophy, and History of Science from the Federal University of Bahia (UFBA).

3 Aline Santana dos Santos Rocha is a professor at Salvador University (UNIFACS), with a Master’s degree and a degree in History from UEFS.

leads each subject to recognize their place, their influence, and their power is shaped by truths that are told to them during their lifetime. Through the truths, which determine by antagonism the falsities (Rocha & Rocha, 2019) - or what follows the norm and what diverges from it - each individual understands their place as a subject in society, and consequently the place of the other. The subject is, therefore, a product of the discourses deferred by the bodies that have the power to transmit truths, namely the government, science, school, family, and all the systems that reproduce them.

“[...] as truth I understand not a kind of general norm, a series of propositions. I understand as truth the set of procedures that allow at each instant and to each one to pronounce statements that will be considered as true.”

(“Pouvoir et savoir”, DE, III, 1994, p. 407, apud. Rocha & Rocha, 2019, p. 38. Translated by the author.)

Through discourses of truth, individuals have their existence validated or invalidated by processes designated by Foucault as dividing practices. The information they consume, the “facts”, end up creating a database by which everyone conforms, and dictating ways to act as well as to punish. Society regulates itself in this way: the subjects insert themselves into a state of order, and within it identify and correct those who break the rule (Foucault, 2000 [1977]). This differentiation automatically creates a division between “us” and “them,” a differentiation that is essential for the maintenance of existing power relations.

The “us” and the “them,” in the framework of this dissertation, are respectively the local population of a country and the refugees who go there seeking shelter. Beyond the dividing discourses that associate being different with something negative, refugees have to face a lack of trust that further complicates a bureaucratic process already created to their disadvantage. Santinho’s studies in her text Afinal, que asilo é este que não nos protege? put forward some points that allow us to understand the various layers of political and economic discourse that have contributed to the marginalization of refugees:

1. During the years of capitalism’s growth, migration between countries was at many times stimulated in order to create a large proletarian contingent for an expanding economic system. Today, however, with the system already consolidated and evolved, this need no longer exists, and the movement of capital and information is much more valued than the movement of people.

2. Several historical events have led to the increasing vilification of “all those who are perceived as strangers” (Santinho, 2013), such as the creation of walls on the US-Mexico border, the occupation of territories in Palestine, the refugee “crisis” that has affected Europe since 2012, among other examples. Moreover, the “war on terror” that gained traction after September 11, 2001, has led to a generalized distrust of all asylum seekers and the validity of their claims.

3. The conceptualization of the idea of forced migration, as compared to unforced migration, has created a hierarchy in which the former has become synonymous with unwanted migration. And the propagation of this “truth” (related to the ideas of truth posed by Foucault) has ultimately shaped the way that both the population and the law deals with refugees.

The reality is that border policies are not designed to guarantee the human rights of immigrants, as was decreed by the Geneva Convention in 1951. The only ones protected by legislation are, in fact, the borders. The state thus inserts itself in a cyclical system: since immigration policies are created around the truth that the state must protect the population from outsiders - to prevent terrorism, to save their jobs, to stop the illegal transportation of refugees, among other commonly disseminated justifications - if the government suddenly favored them, the whole regime of truths would be called into question, and with it the validity of the state.

What the process of marginalization does, therefore, is strip refugees of their power. In a vulnerable situation, as a result of unplanned immigration for survival, the position of asylum seekers in Europe in the face of endless

bureaucracies is one of submission and waiting.

“[Refugees] Are therefore trapped in a determined time and place, subject not to their own decisions about how they will conduct their lives from then on, but conditioned by border policies at the global level or social policies at the national level, which will make them tendentially dependent and passive beings, for a long period.” (Santinho, 2013. Translated by the author.)

Given this context, we return to the question: how can architects help marginalized groups find “their place”?

Well, if in order to recognize “one’s place” one must recognize themselves and realize their power, in the sense of feeling that they have their truths validated, then spaces must be created in order to empower marginalized groups. Since power is what legitimizes an individual’s actions to them and others, the process of empowerment allows refugees to feel comfortable enough to take ownership of a space. Being currently on the oppressed side of power relations, the only way out is resistance: clashing with the current power and creating a new regime of truths (Rocha & Rocha, 2019).

POWER AND SPACE

Parallel to the deepening of Foucault’s studies, the book The Architecture of Empowerment, by Ismail Serageldin, was an important work for the foundation of the research. Many architects and urban planners investigate the issue of socio-spatial inequality, but few mention empowerment, despite pursuing the same goals. There are diverse ways of appropriating a space, and therefore, starting from the point of view of power relations and how they can be changed is a way to move the research away from vagueness and specify it. In this regard, Serageldin’s book validates this thought by studying and defining the “architecture of empowerment”:

“There are, indeed, many distinguished and sensitive architects and urban planners who have joined forces with social activists and imaginative financiers to create what might be called the ‘architecture of empowerment’; that is, a built environment which responds to the needs of the poor and destitute, while respecting their humanity and putting them in charge of their own destinies.”(Serageldin, 1997).

In this book, Serageldin has gathered case studies that show ways to achieve the empowerment of marginalized groups - through the rehabilitation of old buildings, the reactivation of historic centers, the creation of new residential clusters, among other examples. The present research sought to find the key points of these proposals, the common methods that encourage new power relations between architecture, the user, and society.

The central point of the architecture of empowerment, mentioned earlier by Serageldin, is the recognition of the needs of groups for which it is designed. Ideally, these needs are verified through dialogue between architect and said groups (the clients); however, in the case of the Fontaínhas Community Center, this research was done based on Santinho’s studies of the refugee situation in Portugal. The inclusion of the users in the process of conceptualizing the work is indeed essential for empowerment. But, considering that the dissertation addresses an academic project whose target audience is a

variable group, in the sense that one cannot define just one country of origin or the certain period that the refugees will stay in Portugal, this pre-conceptualization dialogue could not be done.

The guide O Meu Lar, O Meu Refúgio, mentioned by Santinho in her paper, makes explicit some needs of refugees that go beyond respect and integration. Refugees need subsidies, rights, documentation, housing, job training, and various other practicalities that fundamentally give them a better quality of life. To provide this support, the Community Center needs to offer educational, training, and cultural programs, and to be a hub of information and support for its users. With power and knowledge being intrinsically linked (Foucault, 2000), through communication and information sharing these individuals move closer and closer to the “new regime of truths”.

Serageldin also argues that the creation of a sense of community is necessary for the individual to realize their own power. The feeling of belonging to a group causes individuals to develop trust and familiarity with each other, and thus to create a community, a crucial pillar of support for marginalized groups. Together, individuals can more

easily claim their causes, and spatially, they can appropriate spaces and make them their own. The appropriation of public spaces, especially open spaces such as streets, squares, and spaces between buildings, is important for community visibility and integration, and the possibility of programmatic expansion that these spaces allow is also a representation of the different future options for their users (Serageldin, 1997). Furthermore, in addition to being appropriable, the space must be adaptable, allowing it to change according to the user’s needs. The center, therefore, will evolve according to its use, being characterized not as a crystallization of the architect’s intentions, but as a building in constant transformation.

Finally, through empowerment the project intends to make users feel in control of their immediate environment, and consequently feel in control of their future (Serageldin, 1997). Given the methods posited by Serageldin to enable empowerment through space, it is clear that empowerment should be noted more as an intention than an action. Since power is a capacity that, like freedom, must be practiced, this dissertation aligns itself with Foucault in saying that architecture has no way of being empowering in itself. In it, empowerment happens in the convergence between the intentions of the architect and the intentions of the user.

PANELS

MODELS

Community Center for refugees in Fontaínhas

Model done for my Master thesis project. It was used along the design process, being here shown in its final version, 2022.

Windmill house

Process model made during my internship at D.Architects, 2022.