The best adventure sunglasses on Earth.

Recycled Frames

Lifetime Warranty

All-Day Comfort Polarized Lenses

favoriteAvailableatyourlocalretailers

The best adventure sunglasses on Earth.

Recycled Frames

Lifetime Warranty

All-Day Comfort Polarized Lenses

favoriteAvailableatyourlocalretailers

WHEN EVERY. SINGLE. GRAM. COUNTS.

Taking the ultralight platform we’ve built with our Exos/Eja thru-hiking backpacks and going even lighter, the new Exos/Eja Pro relies on featherweight NanoFly™ fabric and an essentialist approach to features to deliver a remarkably comfortable, durable and capable pack that weighs in just under one kilogram.

AVAILABLE AT:

P.13 Editors' Message

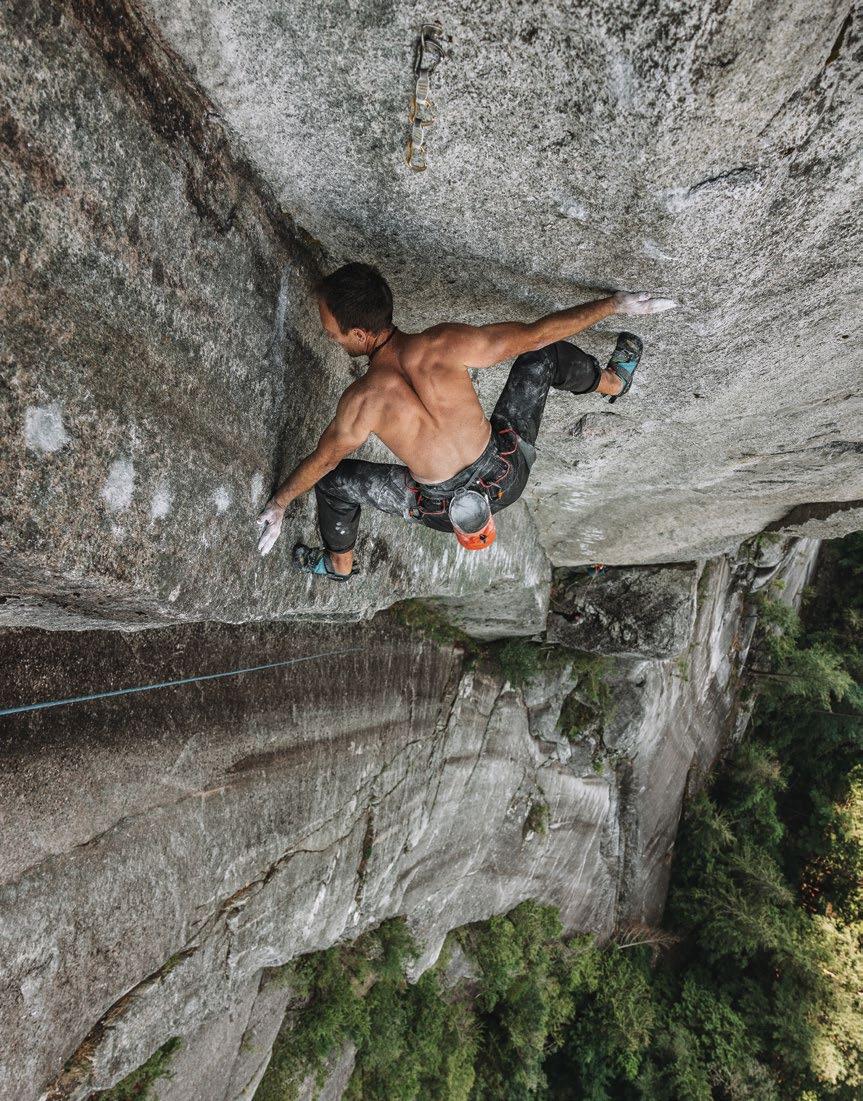

P.15 Artist: Precarious by Nature

P.19 Know Your Neighbour: The Whyte Museum

P.26 Trail and Error

Matt Hadley Figures It Out

P.40 The Reconciliation Trail

Bridging a Cultural Gap

P.50 Juxtapose

The Role of Hunting in Conservation

P.58 Below the Surface

Renegotiating the Columbia River Treaty

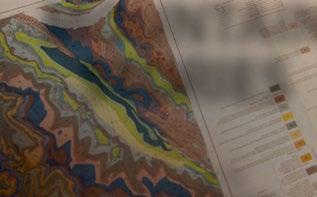

P.23 Enviro: Stratigraphy & Storytelling

P.36 Artist Profile: Captain Baguette

P.65 Steep Thoughts: Pheelin’ Like a Phony?

P.68 Trail Mix

P.72 Gallery

In the spirit of respect and truth, we honour and acknowledge that Mountain Life Rocky Mountains is published in the traditional Treaty 7 Territory which includes the ancestral lands of the Stoney Nakoda First Nations of Bearspaw, Chiniki and Wesley, the Tsuut’ina First Nation, the Blackfoot Confederacy First Nations of Siksika, Kainai, and Piikani, and the Métis Nation of Alberta, Region 3. We acknowledge these Nations to honour, raise awareness, and express gratitude for the Indigenous peoples who have cared for these lands for generations.

PUBLISHERS

Kristy Davison kristy@mountainlifemedia.ca

Jon Burak jon@mountainlifemedia.ca

Todd Lawson todd@mountainlifemedia.ca

Glen Harris glen@mountainlifemedia.ca

EDITOR

Kristy Davison kristy@mountainlifemedia.ca

CREATIVE & PRODUCTION DIRECTOR, DESIGNER

Amélie Légaré amelie@mountainlifemedia.ca

MANAGING EDITOR

Erin Moroz erin@mountainlifemedia.ca

COPY EDITOR

Susan Butler susan@mountainlifemedia.ca

WEB EDITOR

Ned Morgan ned@mountainlifemedia.ca

DIRECTOR OF MARKETING, DIGITAL & SOCIAL

Sarah Bulford sarah@mountainlifemedia.ca

FINANCIAL CONTROLLER

Krista Currie krista@mountainlifemedia.ca

CONTRIBUTORS

Les Anthony, Kenzie Beeman, Agathe Bernard, Ryan Creary, Matt Coté, Lindsay Donovan, Corrie DiManno, Megan Dunn, Andrea Eitle, Leah Evans, Andrew Findlay, John Gibson, Pete Golden, Matt Hadley, Kevin Hjertaas, Karsten Heuer, Reuben Krabbe, Lada Kvasnicka, Cecelia Leddy, Britt Lynn, Zoya Lynch, Lynn Martel, Heather Mosher, Steve Ogle, Bryan Peters, Alex Ratson, Greg Rogers, Steve Shannon, Cody Shimizu, Georgi Silckerodt, Luke Solomon, Laura Szanto, Peter White.

SALES & MARKETING

Kristy Davison kristy@mountainlifemedia.ca

Jon Burak jon@mountainlifemedia.ca

Todd Lawson todd@mountainlifemedia.ca

Glen Harris glen@mountainlifemedia.ca

Published by Mountain Life Media, Copyright ©2023. All rights reserved. Publications Mail Agreement Number 40026703. Tel: 604 815 1900. To send feedback or for contributors guidelines email kristy@mountainlifemedia.ca. Mountain Life Rocky Mountains is published every October and May and circulated throughout the Rockies from Revelstoke to Calgary and Jasper to Fernie. Reproduction in whole or in part is strictly prohibited. Views expressed herein are those of the author exclusively. To learn more about Mountain Life, visit mountainlifemedia.ca. To distribute Mountain Life in your store please email Kristy at kristy@mountainlifemedia.ca.

Mountain Life is printed on paper that is Forest Stewardship Council ® (FSC ®) certified. FSC ® is an international, membership-based, non-profit organization that supports environmentally appropriate, socially beneficial and economically viable management of the world’s forests.

Mountain Life is PrintReleaf certified. It measures paper consumption over time automatically reforested at planting sites in Canada.

O, to be sure, we laugh less and play less and wear uncomfortable disguises like adults, but beneath the costume is the child we always are, whose needs are simple, whose daily life is still best described by fairy tales. –Leo

RostenWhen does the shift happen—the one where we go from carefree, laying-on-our-backs-watching-the-clouds-goby free time, just wanting to have a laugh with our pals to…that other thing? When and why do our lives seem to evolve away from everyday exploration and play? When does that begin: 18, 14, 10? Are we inadvertently steering our kids away from those pointless, unscheduled, unstructured good times as early as elementary school?

Play—real, purposeless, silly play—is everything but pointless. Heck, we’ll go as far as to say it’s essential to our existence. As we mark 20 years of Mountain Life magazines across the country this year, this issue of the Rockies mag is a nod to those existential, playful threads that have woven our mountain communities together over the past couple of decades.

In this issue, aerialist Sasha Galitzki illustrates impermanence as she dangles artfully amongst glaciers; writer Matt Coté witnesses cross-cultural play on the newly-minted Reconciliation Trail; photographer Agathe Bernard makes play her life’s work; and athlete Matt Hadley musters humour and ingenuity to continue to play to his strengths when confronted with a catastrophic injury.

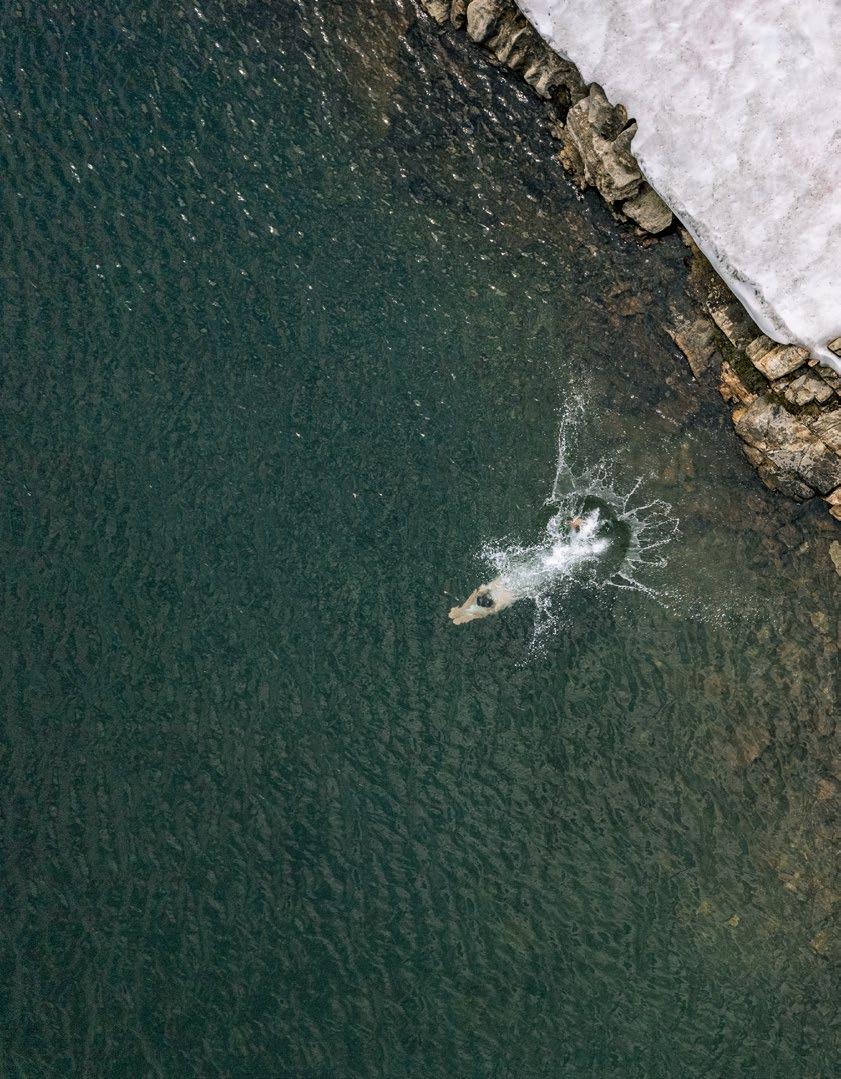

This summer, we’ve got big plans for diving headfirst into newness, weirdness, wild and unruliness that takes us outside our comfort zone, the only goal being to risk failure for the sake of a laugh. Whatever the kid inside you is craving, we hope to see you out there answering the call.

words: Matt Coté

words: Matt Coté

Performance artist, Sasha Galitzki, is reinventing the circus arts by dancing with glaciers. An accomplished skier, mountaineer and silk dancer, Galitzki blends art with alpinism, environmentalism and photography, turning her performances into major feats of endurance. Wearing minimal clothing, she dangles free solo in minus-ten-degreeCelsius temperatures up to three storeys above the frozen ground to create flowing human shapes in the foreground of some of nature’s greatest sculptures. The images she captures serve to interrogate the essence of vulnerability, and the fleeting nature of time, place and body.

It’s a practice that’s nearly unique in the world. While some silk dancers stage bold performances high above desert canyons, very few are performing without a harness, and almost none are doing it nearly naked in the blasting cold.

Though Galitzki’s day job is to direct strategy and finance for a California food company, she grew up in Washington State’s Olympic Mountains and has always been outdoorsy. She spent seven years as a ski patroller in Tahoe, California, before moving north to be with her partner, a mountain guide who now works visitor safety for Parks Canada. She first discovered the circus arts in British Columbia’s Sea to Sky Corridor years ago, but developed her own unique take on the practice during the pandemic while living in Waterton, Alberta—a Parks Canada town of about 20 people. It was a time during which isolation was compounded, but so was inspiration. More than just creating intriguing shapes, it’s now Galitzki’s desire to expose her own limitations to fully express the intensity of the short time she can dance in these places before she risks crashing back down to earth from loss of sensation.

“My time in the air is limited, and no amount of clothing is going to change that,” she says. “Knowing I can’t be there

She dangles free solo in minus-ten-degree-Celsius temperatures to create flowing human shapes in the foreground of some of nature’s greatest sculptures. The images she captures serve to interrogate the essence of vulnerability, and the fleeting nature of time, place and body.

for long, I lean into my vulnerability and embrace it. To me, this feels like a way to show respect to these environments. They are so fragile themselves, that by acknowledging my own fragility within them, I hope to somehow meet them halfway.”

In that light, the photos she brings home force the viewer to reckon with both the temporary nature of performance, and the vulnerability of these otherwise hard and inhospitable landscapes, which will disappear within our lifetimes due to climate change. “I am always hoping people will see the connection of the human element in the wild world,” says Kristopher Andres, one of the photographers Galitzki works with, “seeing the natural integration of the performer and the intent of the story.”

The photos represent a relationship frozen in time that will never exist in the same way again. Many of the crevasses and caves in them have already closed in and melted over.

“Glaciers have always been characterized by constant change,” Galitzki explains. “They naturally ebb and flow over time. But now the change is increasingly in one direction.”

Her performances, then, are a meditation on the impact of the human form on the natural landscape in more ways than one. And because there’s no audience, that process is always a collaborative one.

In a small town where some folks pride themselves on protecting their privacy, these particular Banff neighbours encourage you to be nosy. In fact, they’d love it if you rang ‘em up, made an appointment and

Yuzwa also recounts families who’ve come in to look for their loved ones’ names written in hut registers. In some cases, this is where a missing climber’s name has been scrawled for the last time.

arrived with a notebook full of questions. Yep, the archivists at the Whyte Museum are always ready to spill some tea.

Walking through the sun-bathed reading room transports you back to a more sepia-toned time with its mid-century modern furniture, wood-paneled

ceiling and nostalgic scent of old books. From there, this room leads you to the Archives and Special Collections department, where you will be greeted with big librarian-boss energy by archivist Kate Nielsen and archives assistant for The Alpine Club of Canada (ACC), Hannah Yuzwa.

“At its core, it’s a community resource: built by the community, here for the community,” says Nielsen. “The archives are accessible to everyone. You don’t need a master’s degree to be able to research anything.”

With 700,000 photos and more than 800 fonds and collections, the Archives and Special Collections holds the history, happiness, and heartbreak of the Canadian Rockies. In recent years, this has also become the official basecamp of the ACC library and records, with international mountaineering periodicals dating from the mid-1600s to today. Like their wild cousin the pack rat, they collect and manage everything from maps, newspapers, and magazines to alpine journals from every country.

“We have international researchers looking up specific and niche information as well as long-time locals who are looking to fill in the blanks about their family through the ACC collection,” says Nielsen. “Chic Scott pretty much lives here now too.”

Banff-based mountaineer, historian and author (read: the man, the myth, the legend), Scott has been commissioned by the ACC to take on the epic task of writing a book on their comprehensive history. Since August 2022, Yuzwa has helped by processing a backlog of ACC materials that Scott now draws from for his research. She says working on this project feels like experiencing time travel.

Walking through the sun-bathed reading room transports you back to a more sepia-toned time with its mid-century modern furniture, wood-paneled ceiling and nostalgic scent of old books.

“It is fascinating to see how mountain culture has changed through time,” she says, highlighting photos of ACC camps from 1906 where you would see folks ready to give‘r on a climb with nothing but a hemp rope.

Of the 28 metres side-by-side of archival boxes full of ACC materials that have been entered into the database (with 25 metres side-by-side yet to go), some of Yuzwa’s favourite records to scour are the hut registers, because they show a range of humanity, from hilarity to hardship. She also recounts families who’ve come in to look for their loved ones’ names written in these weathered books. In some cases, this is where a missing climber’s name has been scrawled for the last time.

In her travels through the collection, Nielsen has also begun to recognize the reappearing presence of a group of women from Calgary who have been hiking together since the ‘70s who call themselves the Tuesday Hikers.

“This group doesn’t see it [their register entries] as detailed citizen science observations or realize that these can be used in the future,” she says of the group’s notes—which include everything from details about the landscape to stories of trailhead calamities (like accidentally running over a backpack).

“They also paint the image of women bonding over everyday hiking and being outside for the fun of it.”

Mountains of text are ready to be unearthed by curious campers in the Archives and Special Collections, because most importantly, “these stories are everybody’s stories to come and read.”

Ready to dig? You can search the online database at archives.whyte.org or make an appointment Tuesday-Friday. It’s also open to drop-in visitors from 1:00-5:00 p.m. on Thursdays and Fridays.

Or contribute to documenting The Alpine Club of Canada’s history, by donating at: bit.ly/ACC-history

ABIGAIL LAPELL - ANDRINA TURENNE - ALEKSI CAMPAGNE

ALLISON RUSSELL - THE ARROGANT WORMS - DAVID KEENAN

THE FRETLESS WITH MADELEINE ROGER - HARLEY KIMBRO LEWIS - INN ECHO

IRISH MYTHEN - JAKE VAADELAND AND THE STURGEON RIVER BOYS

THE MBIRA RENAISSANCE BAND - THE MCDADES - OKAN

OVER THE MOON - RICHARD THOMPSON - SERENA RYDER

SUZIE VINNICK WITH SPECIAL GUEST TONY D

SCHOOL OF SONG FEATURING: BRIANNA LIZOTTE - JED AND THE VALENTINE - KAELEY JADE - MARI ROSEHILL - SAMMY VOLKOV

THE CAVE ARCADE - IRENE POOLE - THE ISAAC BROTHERS

MIKE TOD - MISTER BIRD - THE NICO TOBIAS BAND

PHILLIP ALEXANDER NUGENT - RICK SIMON

THE TREBLEMAKERS - ZEBRA

canmore folk festival

CANMOREFOLKFESTIVAL.COM OR 1.888.655.9090 FOR TICKETS

While standing on the Columbia Icefield, Bow Valley author and storyteller, Lynn Martel, and ACMG Hiking Guide, Tim Patterson, contemplate how the layers found in a glacier mirror the complex layers of storytelling that make up our history.

words :: Lynn Martel

words :: Lynn Martel

From foothills to rocky summits, mountains are experienced in layers. First-time visitors are awed by the grand landscape, the expansive vistas and majestic peaks. Those who return, or who stay, see layers that reveal themselves over time and with familiarity. They recognize the individual character of lakes and creeks and aspen stands. Those who explore the ridges, the cliffs, the summits and the glaciers nurture deeper connections—the feel of limestone under fingertips, the scent of splintered spruce in melting avalanche debris in June, the deep blue of a bottomless crevasse.

In the Canadian Rockies, the mountains were formed of layers of sediments piled one onto the next in a shallow seabed, and then thrust upward as tectonic plates pushed layers atop others. Successive ice ages brought more layers to the landscape, when cold temperatures persisted over centuries, millennia, causing snow layers to pile up until the accumulated weight compressed that snow into ice. Swelling glaciers bulldozed their way along the terrain, pushing rocks and earth, grinding on bedrock. When the glaciers melted, they left behind rock piles, called moraines, and more layers of our geological history.

Every individual glacier is formed of its own unique layers, influenced by the bedrock supporting

its mass, and the substances that fall from the atmosphere. When glaciers flow over a steepening slope, the ice splits and cracks into crevasses and seracs. Those chasms and unstable towers reveal layers that tell stories of the glacier’s life, like the rings of a tree trunk. Amidst stripes of glimmering glacier blue and frosty white, a dark layer of soot announces a volcanic eruption, or an intense wildfire season. Those ice layers trap natural gasses and manmade chemicals, sealing them in a time capsule.

Just like the layers of ancient ice that form a glacier, the layering of narratives is especially true in Indigenous storytelling, says Tim Patterson of Zuc’min Guiding. Patterson is a member of the Lower Nicola Indian Band that belongs to the Scw̓éxmx (people of the creeks), a branch of the Nlaka’pamux (Thompson) Nation of the Interior Salish peoples of British Columbia. He grew up in Revelstoke, B.C., within the Sn-səlxcin (Sinixt-Lakes) territory, exploring the Selkirk and West Kootenay mountains.

Indigenous stories, he explains, have three layers: the individual, the family or community, and the greater world. And, just as glaciers are dynamic and constantly changing, the knowledge shared in those stories is never static, it’s cumulative, and they continually add to dimensions of a place, and to the story of people, and time.

In Indigenous storytelling, Patterson explains, the meaning extends deeper still.

“In Indigenous experiences, our significant places are only genuinely recognized by the individual or family that contributed to the narrative of that specific place,” he says. With each Nation, another story layer is formed.

Indigenous stories often encompass the critical role of water. For the Shuswap people, water provides a vehicle for renewal. Those stories hold personal, individual experiences, which, like water flowing downstream, merge with stories of family connections to water and community life. Similar to how a river expands when fed by tributaries to ultimately pour into an ocean, the stories expand to encompass the larger landscape and extended community—the grand story.

Today’s stories incorporate another layer, that of melting ice. Scientists predict that Western Canada’s glaciers will decrease by 90 per cent by 2100. The melting peels away layers, erasing established mountaineering routes, making them impassible. Sometimes gear or bodies melt out, exposing evidence of past events.

As we stand together, our boots touching the surface of the Athabasca Glacier, thousands of years of history frozen in time below us, Patterson adds, “Now we’re part of the story.”

In 2019, the strengths Matt Hadley had honed through a lifetime of working and playing hard were tested when he suffered a catastrophic injury that resulted in the loss of his right leg. This Canmore-based trail builder and ex-pro mountain biker’s life is a story of ingenuity, determination, community and a pure love for the outdoors that exemplifies what’s possible when we live life knowing that if we really want something, we’ll figure it out. Even if that means doing things a little differently.

words :: Kristy Davison

You know when you’re riding your bike up a big hill, feeling super good about yourself for being out there in the rain, even if you are gasping for breath and your legs are kind of dying, and a guy with one leg rides by you and smiles a friendly hello, breathing about as hard as if he’s been out for a stroll by the river? It might be Matt Hadley.

Matt and his wife Catherine Vipond met while competing on the Canada Cup mountain biking circuit. Matt will tell you it was his creative problem-solving that made her fall for him, referring to a time he had the brilliant idea to wear yellow dish gloves during a race to keep his hands dry in the rainy conditions. She tells me, "Yeah, no, that wasn’t it. But they did make him stand out."

The two put down roots in Canmore in 2011, continuing their training and competition and eventually sharing their knowledge with young local riders as mountain biking coaches with the Rundle Mountain Cycling Club (RMCC), where they have inspired a whole generation of riders with their love for the sport and focus on experience over outcomes.

Together, they’ve recovered from more than their share of sportrelated injuries including severe concussion, pneumonia, even Lyme disease. But not even these things could have prepared them for what was to come in 2019.

Matt and Catherine were hiking near Moab, Utah. Above them, a basketball-sized rock was careening earthward, unseen. In an instant, the two worlds collided, shattering Matt’s right leg, right hand, and life as they knew it.

In survival mode, Catherine began first aid and signalled a nearby hiker to call 911, summoning the local EMS and Search and Rescue teams. They were evacuated to a waiting ambulance and taken to hospital in Grand Junction where his first surgery—a transtibial (below-the-knee) amputation was performed. The following day, air ambulance rushed them to Denver where he underwent a further transfemoral (above-the-knee) amputation necessary to save his life.

Matt’s brother, Adam, flew down to meet Catherine and Matt the next day, and his parents, Eric and Jane, arrived soon after. Together, they endured the next couple of weeks: a blur of surgeries (on both his leg and his hand), intermittent sedation, IVs, feeding tubes, pain killers, skin grafts, dialysis machines, and ice chips for dinner.

“The doctors told us that if it weren’t for how physically fit Matt is, how amazing his lungs are, they probably wouldn’t have been able to save his life,” says Catherine, reflecting on how close they’d come to tragedy.

After 16 days in Denver, Matt was deemed stable enough to fly home to Foothills Hospital in Calgary. It was good timing, too, because their accident insurance had run out.

At Foothills, as his appetite and strength started to make a comeback, rehab began. Unbeknownst to the doctors, he had actually already begun doing little workouts in secret with Catherine, who is a physiotherapist, and these had put him ahead of the

curve. Movement was a balm, and thanks to the freedom provided by a walker, Matt dedicated himself to wearing a hole through the linoleum in the hallways of the hospital. “He made every challenge into a game,” remembers Catherine.

This rehabilitation process would be a marathon, not a sprint. For Catherine and Matt, who competed with the world’s top endurance athletes for years, and had persisted through some serious physical setbacks together before, this concept was second nature.

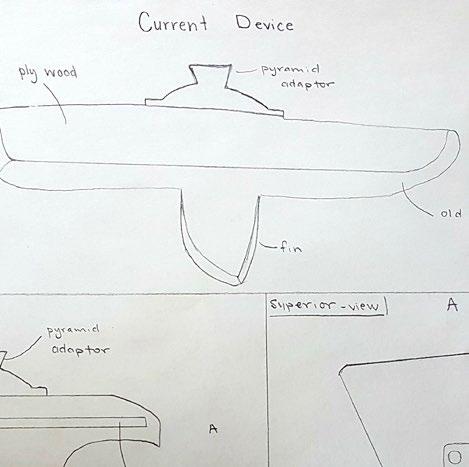

The trail of Matt’s recovery was waiting to be built, with thousands of unknowns and hurdles stretched out before him. But he had never been beaten by a problem before. Laying in his hospital bed one night, he began to break down his newest obstacle into manageable parts; first up: “How am I going to make a prosthetic touring foot that will work with my backcountry ski bindings…”

“I’ll figure it out.”

These are the words Matt repeats in his head before doing something challenging that he’s never done before. “I use it when I’m dropping into a line when I’m skiing or biking, or the first time I’m hiking a mountain. And I’ve applied it to making feet or other gadgets to attempt to replace what a human leg can do,” he says.

Anything he needed to get back to mountain biking, skiing, waterskiing, climbing, canoeing, hiking and all of the other activities he loves, he would build it.

Getting down to work on his growing collection of custom feet for outdoor sports, anything goes, but lightweight and overall functionality is his greatest concern. The feet he needs don’t exist,

“The doctors told us that if it weren’t for how physically fit Matt is, how amazing his lungs are, they probably wouldn’t have been able to save his life.” –Catherine VipondEarly x-ray of Matt's transfemoral amputation. COURTESY OF MATT HADLEY. Catherine, Graham and Matt outside their home in Canmore GEORGI SILCKERODT

*Outriggers are specialized poles with short skis on them that assist disabled skiers with things like balancing, stopping, turning, and getting on and off the lift.

“I’d say his style is pretty function-over-form. He’s not concerned about whether it looks sexy, as long as it does the job.” –Catherine VipondGEORGI SILCKERODT

and his needs are so specific to his own body and the sports he wants to do, that the only way to get them is to make them himself. For simplicity, he has manufactured each of his sport attachments to connect directly to the curved carbon fibre foot at the end of his prosthetic leg using the same particular style of bolt. “I never leave home without a 4mm Allen key, and it’s all I need,” he says.

Friends and neighbours have pitched in plenty of castoffs: broken skis, boots, and leftover materials like out-of-use trail signs that he can play and experiment with. What started as a hobby has turned into a real fetish. Wood is his material of choice for prototyping, and, as the design evolves, materials can be anything from found pieces of plastic, rubber and metal, to the soles of old boots, skate blades, and even 3D printed elements.

“I also use Crazy Carpets (yes, that’s right, the sled) to make a bushwhacking foot so I don’t get caught on all the shrubs when I’m hiking.” This bright blue foot protector looks slightly like a cone of shame on a sick puppy, but it works.

“I’d say his style is pretty function-over-form,” Catherine weighs in. “He’s not concerned about whether it looks sexy, as long as it does the job.”

Matt’s commuter bike rig, on the other hand, is beautiful unit. Catherine remembered she had a crank that worked each leg independently from her days of national team race training. They installed this onto Matt’s bike to enable him to continuously pedal with his left leg and to rest his prosthetic leg when needed.

When asked whether she’s amazed at how calmly and creatively Matt has approached facing challenges resulting from the accident,

Catherine replies “Am I amazed? Not really. He’s always been like this. His creativity has just become more visible to others now.”

In June 2021, Matt took experiments with enhancing his mobility to the next level, opting for a procedure called osseointegration. In this process, a porous metal implant is surgically anchored into the bone. Over time, it becomes permanently integrated into the body as the bone grows into and around the metal. When the healing is complete, a titanium pin will be left protruding through the skin and is intended to connect seamlessly to a prosthetic limb, making the limb feel more like an extension of the body.

Does it work? “It’s night and day compared to the struggles I was having with the socket on my original prosthetic, which would lose suction and fall off all the time,” he says, laughing. “That doesn’t happen anymore. And now I can actually feel the difference between walking on carpet and walking on hardwood.”

Besides your dang leg falling off when you’re out for a walk, osseointegration solves a ton of other problems caused by socketstyle prosthetics, like pinching, sweatiness, poor control, nerve pain, skin irritation, blisters, bruising and the like. Matt suffered through all of these, and badly, because he was still attempting big days outside. Osseointegration has yet to become commonplace as an alternative to the traditional socket-style prosthetic. This is something Matt hopes will change, and he advocates for normalizing this procedure in Canada whenever and wherever he can.

passionate folks. If you’ve ever hooted and hollered along trails like Mad Handler (a play on his own name), the Laundry Chutes, FYI, Blue Coal Chutes, Road to Ruin (version #2), or the Eye Dropper, you’ve enjoyed the fruits of Matt’s and his team’s labour. He also designed the super-fun Killer Bees and Long Loop Trail with Odyssey, Iliad and the Rundle Connector.

In 2014, Matt was hired by McElhanney—a construction engineering company—as a trails technologist: he’s worked on the new Ha Ling trail above Canmore, the High Rockies Trail, improvements on Îyâmnathka (which required him to make a hellish hike up a scree slope on crutches at least 15 times during construction), and flood repairs to the Jewell Pass trail.

One of the unique features of the Ha Ling trail redesign that reopened in 2019 is the “floating stairs.” Matt’s father, Eric, was a parks planner back in New Brunswick. He’s been on a trip to the Sahara Desert and marvelled at the sand dune “ladders” he saw there. He played around with the concept and applied it on a trail build back home. Matt recalled his dad’s inspiration and ingenuity, and together with the McElhanney team was able to find a way to successfully apply a similar solution on the most slippery scree section on Ha Ling.

Matt attributes much of his recovery to all of the people in the community who’ve been generous with their skills, experience, and support. From a tricycle race fundraiser hosted by the RMCC, to folks who’ve donated gear and/or time towards custom builds; from friends who offered to chauffeur, to those who brought food by the house; from the crucial care of his physiotherapists (Catherine included), to connection with fellow amputee athletes and the steady support and love of his family, he is quick to share his gratitude for all who’ve contributed to his incredible comeback.

In particular, connecting with Rocky Mountain Adaptive (RMA), a Bow Valley-based charity whose mission is to “create and provide accessible adventures for individuals living with physical and/or neuro-divergent challenges,” was a pivotal opportunity that helped him find his balance with skiing on one leg, a set of new skills that eventually got him back where he wanted to be, in his happy place in the backcountry.

“A whole lot of the participants at RMA inspire me. Their accomplishments might not be climbing a mountain, but…it might as well be,” he says.

Essential to Matt’s success has been his open mindedness to receiving help. On outdoor adventures, friends assist by carrying his gear—and when it comes to backcountry skiing, Catherine adds power by towing him with a rope on the up-track. The silver lining?

“It’s great exercise for everyone,” he says with a chuckle.

An East Coast sense of humour and unfailing optimism delivered moments of warmth and humour through the darkest days following the accident, and family remains a source of inspiration and encouragement.

Adam was there the first day Matt sneakily tiptoed up onto a bike again, just two weeks after being released from hospital. Catherine rounded the hill and stumbled upon the two brothers spinning laps up and down Hospital Hill, bypassing steps three to five of the six-step plan he had promised to adhere to.

“Once in a while Catherine will tell me something is a terrible idea, which is also helpful,” he laughs.

LIFA INFINITY PROTM is our most innovative and sustainable waterproof/breathable technology to date, made without any chemical treatments. Developed with professionals around the world, to protect them from the elements while not harming the environment they work in.

What happened in Utah was the kind of disaster that brings out the best or the worst in a person, and, thankfully for everyone, Matt’s natural superpowers shone through early on. Coming to terms with the loss of a leg was as painful as you’d imagine, but Matt’s approach to pushing himself to the edges of his abilities, shaped by an in-born persistence, boundless (and genetic) ingenuity, ready acceptance and a seemingly bottomless capacity for figuring out how to make things better has made almost anything possible.

He is also busy passing along the Hadley family hobby of crafting homemade bike parts, rigging up his son Graham’s strider bike the way his dad did for him, providing the next generation with a sense of freedom and independence from a young age.

Graham loves to mimic his daddy, including taking a “crutch” (a pole) with him on outdoor wanders, and using Matt’s foot brush to clean off his own shoes before coming in the back door. “Kids pick up on everything. They’re always watching us,” Catherine says. Growing up with these two as parents, Graham is witnessing resilience and adaptability as the standard, as his parents continuously create fresh and different ways to pursue adventure and spend quality time in the outdoors.

I once asked him if he felt like there was anything he couldn’t do. He took some time to think and then answered, “Maybe surfing?” Then I watched as his mind went straight to how, actually, he probably could surf if he wanted to: he was imagining what it would take to build a surf leg right before my eyes.

For a guy who’s as humble as the trail is long, the only thing Matt gets a little puffed up about (aside from his life-saving lung capacity)

is his custom-built leg and the plethora of parts he’s whipped up to improve it. Don’t be surprised if he opens up his custom, zippered pant leg on the street and shows you his newest gadget.

“I’ll show off my leg the same way I’d show off my bike,” he says. “I don’t have a leg, and I have a really cool rod coming out of it — want to see?”

More images and videos: mountainlifemedia.ca/matt-hadley

Matt would like to give thanks to the local businesses who have donated time, skills and/or gear to help him out, including Bow-Cor Welding, Monods, Outside Bike and Ski, Bike Therapy, Lone Tree Enterprises and Colman Prosthetics.

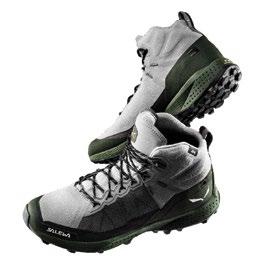

PEDROC PRO MID POWERTEX BOOT

PEDROC PRO MID POWERTEX BOOT

My uncle was losing his battle against cancer when I took this photo, and sending him images became my way of supporting him. I wanted to find an image that would give him certitude he would be with us long after he left—like this beautiful tree floating and leaving the estuary towards saltier water. I shared the photo with my uncle who replied, “Your photo is like a balm for the soul and the earth.” That was our last communication.

A beloved ML Rockies contributor, Agathe Bernard, shares the evolution of her nomadic existence and how life on the move creates opportunities to behold moments of unexpected beauty.

words :: Erin Moroz

Agathe (pronounced Agat), is known by many names. Friends around the globe know her as Doctor Love, Backcountry Mom, the Adventure Queen or Captain Baguette. But her real name was inspired by the fiery-coloured beach pebbles—agate—back home in the volcanic depositions of Gaspésie, Quebec, where her dad grew up.

The nomadic tendencies that have driven her to pursue a life of near-constant movement were set in stone long before #vanlife became a hashtag. Born in her parents’ car during a snowstorm, the road has always felt like home.

When she started sneaking out of her bedroom window and hitchhiking to watch a much older boy do a van build, she was just 12. At 16, in college, she always had enough underwear and supplies packed away for an adventure in case something popped up. “I’ve always been ready to go,” she says, laughing kindly at herself.

A peruse through Agathe’s website is a feast for the eyes, a glimpse into passion projects and adventures that portray her foundation as an earth scientist. It’s a window into the natural world through the eyes of a true wanderer, environmentalist, crusader, and voice for the voiceless. Part documentary, part love note, Agathe’s subtle and symbolic imagery invites the viewer to dive deep with her into the mysteries of earth, fire and water, and the people who find meaning there.

“Being a nomad is in my blood,” says Agathe, from her temporary home base, a rented cabin in Shirley, British Columbia. The day after we chat, she’s off again, this time to Ucluelet for a couple of shoots and then to the utopia of Sointula, where her renovated sailboat and a seven-month journey along the north island awaits. The skyrocketing cost of everything—fuel not excepted— forced Agathe’s drifter tendencies from the open road to the open ocean. This trip, Agathe will visit friends who’ve become family and document the life of grizzlies, whales and Indigenous communities along the coast. Then, it’s over to Africa to raft the Zambezi River with a gaggle of Kootenay musicians.

See more of Agathe’s imagery in the Below the Surface article, page 58 of this issue.

I was lucky my parents took us on long camping trips as a kid; this was a beach with wild horses in Virginia, circa 1988

My favourite van, and the day Leo bounded into my life. Famous painter and friend Stephanie Gauvin painted a ski touring scene on one side and a mountain biking scene on the other. Revelstoke, 2016

Travelling as light as possible: drinking soup from a seashell. Australia, circa 2003

“I have nothing to reconcile,” Tom Eustache says plainly to a room of 200 white people, followed by a small but exasperated chuckle into his microphone. A member of the Simpcw First Nation, Eustache has just been asked how non-Indigenous folks can help First Nations with reconciliation. His answer, softly and affably delivered, belies an inescapable fact: Reconciliation is a colonial burden, not an Indigenous one. And yet, when it comes to this fraught process, First Nations continue to come to the table.

In this case, that’s the biannual Mountain Bike Tourism Association (MBTA) symposium at SilverStar Mountain Resort in British Columbia, where Eustache is speaking on a guest panel. As a rider and a trail builder himself, he’s found common ground with everyone in the room—something that’s been elusive in the grander scheme of Canadian reconciliation. For the Simpcw and other Nations, trails have become a way to reoccupy their territory and bring health and happiness back to places clouded by the legacy of Canada’s residential school system.

To help heal his home community of Chu Chua, B.C., about an hour north of Kamloops, Eustache—as both the Simpcw’s public works manager and a volunteer—has been coordinating the construction of a growing network of trails in conjunction with the Indigenous Youth Mountain Bike Program (IYMBP) and First Journey Trails. The forest floor here is sandy and dry, the spacing between the pine and spruce ideal for sightlines, the hills rising in gentle gradients from the wide, lazy river that settlers named the North Thompson. It’s as perfect a place to ride fat tires as there is in B.C., situated midway between the storied freeride epicentres of Kamloops and Williams Lake. But, for the Simpcw, mountain bike trails aren’t just an amenity—they’re an invitation.

On the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation, only a few weeks after the MBTA symposium, a hundred riders gather in Chu Chua at the inaugural Allies Mountain Bike Festival. It’s an open call to come celebrate and enjoy the flowing lines the Simpcw have carved into their territory. Non-Indigenous riders with a mind toward reconciliation have travelled from all corners of B.C. and as far away as India. Riders from four other B.C. First Nations—the Squamish, Musqueam, Ucluelet and Wet’suwet’en—have gathered here, too, alongside Indigenous mountain bikers from Waterhen Lake First Nation on Treaty 6 territory in Saskatchewan and from the Navajo Nation in the southern United States.

“You’re next,” says Tina Donald, a Simpcw councilwoman leading the welcome circle as she systematically asks each individual to introduce themselves. It takes a while to make the full round, as even latecomers aren’t skipped over. On such an auspicious day, each of us must take the time to see and hear one another. A welcome song by drum follows, performed by Leon Eustache, Tom’s nephew, and then it’s time to ride. For the remainder of the day, all further formality is out the window. The purpose is simply to be together.

The crowd disperses towards the trailhead, just a few hundred metres up the road from the Neqweyqwelsten School, and disappears into the woods. Some load into shuttles, others choose to pedal up the Fish Trap climbing trail. The loops are short and gratifying; you can bang out multiple descents on trails that match the best in the province. Step It Up, with modern flow and well-calibrated jumps, proves a group favourite; Section Zero is similar but faster, with dirt that feels like Velcro; Section One feels more natural, with technical sections throughout.

The world-class network begs a simple question: Given what Indigenous people have lost to European settlers and their descendants, why invite any of us when they could keep it to themselves? “To show everybody how we gather and how we share,” says Tom Eustache. “I can sit here and talk to you. And maybe because we’re together here in a different light, you can listen, and you’re able to hear. Because we just went for a ride, we have the opportunity to be calm, to sit down with like-minded things.”

Millar, whose irrepressible excitement commands every bit of his body language, says building trails and learning to ride has both lifted him from hard times and given him something to strive for.Gathering at the Simpcw network's trailhead, Terrence Yazzie, Tom Eustache, MT Garcia and others bask in sunshine and friendship between laps.

It’s such a generous answer it almost shames the question. But another part of it, Eustache admits, is that when you build something you’re proud of, you want to show it off. There’s an innate satisfaction in having people from the best-known mountain bike towns in B.C. visit your trails and say, “These are awesome!”

“I hope you guys have fun here,” he beams. “It just has me so proud of who we are. That’s something I’ve been feeling more and more lately—proud of who I am and where I’m from. A lot of First Nations don’t get to feel that.”

Pride is also becoming a familiar feeling for Jay Millar, visiting from the Ucluelet First Nation. The Ucluelet, too, have been etching trails into their unceded territory, often resurrecting old hunting routes in steep, rugged rainforest where, as he says, “the ocean slams into the mountains.” As part of the trail-building crew, Millar confesses to being tugged at by an impulse to keep the trails secret, while also wanting to use them to reach more people. “It’s a bit of both,” he says. “Through education, one can hopefully move on from what was in the past. With more and more bikes coming out, it’s a necessity for our community—and a way to get Indigenous people on the land.”

Millar, whose irrepressible excitement commands every bit of his body language, says building trails and learning to ride has both lifted him from hard times and given him something to strive for. He grew up surfing, but is now saving to buy a carbon mountain bike to be better able to enjoy his own work and to explore his ancestral territory even further. It makes him feel connected, but moreover, it’s just a lot of fun.

The sentiment resonates with Chelsie McCutcheon, a Wet’suwet’en rider from Smithers, B.C. “Fun is a healing agent,” she explains, her daughter riding with other kids in the background. “For a lot of First Nations communities, there’s a sense of hopelessness—a whole that needs to be stitched back together. And it seems so basic, but having fun is a really big part of that.”

McCutcheon now lives in Squamish, where she helps run the Squamish Nation Youth Mountain Bike Program and has also been involved in the Indigenous Life Sport Academy. Depression, she recounts, is an ongoing scourge in Indigenous communities. But sports like mountain biking and snowboarding have helped keep her own head above water, and she believes they can build a foundation for generational healing.

“We’re in a place where, in modern society, it’s not appropriate to show you’re grieving. And so, when you have to hide that, you get stuck. But [on the trails], incantations of healing are embedded in that suffering,” she says. “It feels like your throat is burning, but it’s a different type of suffering. Back home, you’re grieving over death and tragedy, but suffering [through exercise] almost strips away that ability to talk down to yourself.”

While it’s true movement is a powerful agent for both mental health and physical well-being, McCutcheon is clear-headed about the fact that getting people moving is a whole other task. It takes infrastructure—like the Chu Chua and Ucluelet trails, which have become a model of cooperation. While governments at all levels continue

For everything that makes us different, there is much more that makes us the same. Give us two wheels and a hill to play on, and you’ll see for yourself.The Dalai Lama said, “A zero itself is nothing, but without a zero you cannot count anything; therefore a zero is something, yet zero.” Matt Coté investigates this claim on the Section Zero trail.

to flail at this task, mountain bikers are becoming good at it. The IYMBP and First Journey Trails—among other groups—have assisted dozens of northern and coastal communities in building trails. Of course, it helps that B.C. is one of the most desirable mountain-biking destinations in the world, with riding both a nearly universal part of the culture and a significant economic driver.

If B.C. has become ground zero for Indigenous-led trail development, it’s likely because of one thing: unlike most of Canada, there are virtually no land treaties here, with almost the entire province remaining unceded. The same is true of Yukon, where the Tagish First Nation undertook a similar trail initiative in Carcross as far back as 2011, and now has a tourism amenity drawing thousands each summer to its trails, shops and food services. As First Nations develop their own networks, they can begin to share in those economic opportunities. According to the MBTA publication 2016 Sea to Sky Corridor Overall Economic Impact of Mountain Biking, which summarized studies of the Highway 99 axis between North Vancouver and Pemberton, trails produced $70.6 million in visitor spending, $35.9 million in wages and $18.6 million in tax revenues that year—doubling the amounts from a previous study in 2006.

And the sport’s benefits aren’t isolated to Canada’s westernmost province. In the U.S., the Navajo Nation now hosts the monumentally popular Rezduro—billed as the world’s first Indigenous-led mountain bike enduro race—on a growing network of self-constructed trails.

Terence Yazzie and MT Garcia are visiting from the Navajo Nation to compare notes. Their sizeable reservation spans portions of three states—Arizona, Utah and New Mexico. Yazzie and Garcia advocate for trails within it. Garcia works to spread mountain biking to school kids, and over the course of only a couple years she’s seen more than 40 Navajo youth take up the sport.

“Myself and other trail builders, and people in the community advocating for cycling, are trying to build a safe space,” Yazzie says, acknowledging the discomfort that comes with trying something new. He was drawn to the sport at a young age, growing up mountain biking in Flagstaff, Arizona, with British racer Steve Peat as his idol. In Chu Chua, we see that influence in action: Yazzie rails corners with perfect bike-body separation, and still runs his brakes reversed (Brit style) in homage to his childhood hero.

Although reconciliation in the Canadian context is a new word to him, Yazzie well understands the concept. “I think it’s just sharing the cultural significance of all the people in the world, right? Like, because you’re not Indigenous doesn’t mean you don’t have culture. So then we get to share this with each other and build community.”

At this gathering, that notion of sharing plays out all day on the trails, but also at night by the campfires, where McCutcheon explains the significance of the potlatch—an Indigenous ceremony around giving and sharing meals—and how B.C.’s early colonial government banned it. Eustache likewise explains to Vinay Menon, from Pune, India, that Indigenous language in Canada was entirely oral, and was thus nearly wiped out by the residential schools. Menon is shocked to learn there were no scrolls, and recounts the tribal diversity of his homeland that persists largely thanks to paper records.

Coming into these exchanges with wholehearted curiosity is a tact that Sean Bickerton is interested in exploring. He’s a non-Indigenous resident of Squamish, attending the Allies Fest with his two young children. A natural resource officer for the B.C. government who works in Indigenous relations, Bickerton admits that the position—a form of law enforcement—has historically been an arm of colonialism. As such, he worries about being perceived as an enemy, but is continually blown away by the welcome he feels when he visits First Nations. It’s become important for him to normalize the feeling of “We all belong together” for his kids. “I wanted to step away from the work side and actually just come in the open, you know? The message of the Indigenous Youth Mountain Bike Program is, ‘Come in a good way.’ So I wanted to come together in a good way in a community I’ve never been to before.”

For Bickerton’s kids, the immersion part of the experience is the most compelling. It’s something you just can’t learn in school, where Indigenous people are too often only a concept. “We could have stayed in our home community for National Truth and Reconciliation Day, or we could come and visit this event as mountain bikers, and hopefully expose my kids to how this First Nation community works. To live and to learn, and to do it by bike. It makes an immediate piece that kids can relate to—a vehicle to come and absorb new information.”

Yazzie puts the culmination of that process on display at the festival’s close, with a bannock dinner and farewell ceremony at the school. Instead of piling inside, he and Tom Eustache’s pre-teen son, Theo, are rapt in doing skids, cutties and 180s against a grass bank. A dozen other riders join in, noodling on the impromptu feature, falling, laughing and making themselves late for dinner. Time seems malleable as everyone returns to a simpler state—childhood, in all its uncomplicated wonder. For everything that makes us different, there is much more that makes us the same. Give us two wheels and a hill to play on, and you’ll see for yourself.

Back inside, youth from the Squamish Nation pull Tom Eustache aside to present him with a carving as a gift, and Leon drums out a farewell song. He says a tearful goodbye to the group of mostly white mountain bikers, telling them his heart is big from seeing everyone on the territory. “Come back, come ride the trails again,” he says in his native Secwepemctsin, “and when you do, come say hello—weyt-kp.”

“That’s something I’ve been feeling more and more lately—proud of who I am and where I’m from. A lot of First Nations don’t get to feel that.”Leon Eustache sings a welcome song to a circle of riders newly arrived to celebrate Simpcw mountain biking and culture.

RIDE FARTHER. RIDE FASTER. RIDE FREE.

The first dusting of snow lies on the backcountry of Banff National Park. In its fresh white icing are imprinted steps: squirrels’ parallel tracks, a bird's three-toed pattern, hare’s tiny front and comically large hind paws. But the larger animals have worn this trail through the spruce forest, and deer and elk hooves can be seen in the snow as well. Pete White has been noting them for kilometres and recording all the tracks he crosses in a small yellow field book.

White and other biologists have walked this transect for years, observing, counting and reporting the tracks they find. Along with wildlife cameras and collars, this is how they monitor wildlife and record how their patterns shift over time.

White sees more than a recreational hiker would on his 20-kilometre loop through these mountains. The tracks tell a story of deer in various groups moving from areas rich in food to terrain safer from predators. He sees the movement of an elk herd post-rutting season. And then he sees the cat prints layered over top. He sees where the cougar has followed the trail and where it has quietly slid into the forest and gained higher ground. He can imagine how the cat tracked the elk—not that different from how he is now.

As a biologist, White does a lot more than hike in the woods. “The job looks at how people and development co-exist with wildlife and how we manage that; either reactively by hazing a bear out of town, let’s say, or proactively through education or signage and temporary closures,” he explains. This work of protecting wildlife from humans, and vice versa, is a full-time job for roughly a dozen people in the Bow Valley.

White has a quiet, sturdy way about him; a humble, upright sort of presence you’d imagine comes from lots of time alone in the mountains and a compassion for humanity that surely gets tested at work. “Part of the job is certainly the ability to deal with people,” he says. “Staying calm in stressful situations with wildlife, but also with people because so much of the job also involves working with visitors and residents. Coexistence has the pressures of all that, what the wildlife are doing, and what the humans are doing.”

In summer, White and his colleagues spend a lot of time responding to calls: elk in people’s yards, bears on the highway or coyotes eating garbage in a campground. Come fall, those calls decrease, and they have time to catch up on office work like reporting, special projects and connecting the data they’ve collected all summer with research. But the soul of the job is somewhere out there in the mountains, moving through the wilderness, observing, tracking and trying to understand the lives of wild animals.

On fall weekends, White wakes up before dawn and is out walking game trails far outside Banff National Park, in the foothills where snow has not yet fallen, but the predawn air is cold, and the ground crunches with first frost.

He’s been walking this land a lot lately, observing the wild lives that are unfolding here, and learning their patterns. How many deer are there, and what groups are they moving in? Are they healthy? Where are they finding food and water? Are there older bucks who aren’t mating anymore? Does that doe have a fawn? He looks for signs of predators, too—other predators.

Eventually, over weeks, he triangulates the three things deer need: water, food and cover, and comes to understand the deers’ movements between those areas. Finally, with the scouting done, he returns to a spot near the middle of that triangle. And hidden in a place with clear sight lines, he waits. Early in the hunting season, he waits with his bow; later in the season, he has his bolt-action rifle. He’s likely practised the shot that he’s waiting for and, as he sits, sometimes for hours, he rehearses it in his mind.

When White talks about hunting, he does so with a reverence that he doesn’t have for his other recreational activities like snowboarding or climbing. It’s on par with the respect he expresses for his profession. Over a beer, in a reminiscent tone, he explains, “It’s special to have an interaction where you are being completely still and quiet, to allow wildlife to come right up to you. I’ve had an experience sitting on a hillside where a pack of wolves come right up beside me—come to within ten feet of me and sniff around. It’s an intense feeling, really special.”

As the deer White’s been waiting for approaches, tension grows. Frozen fingers slowly grasp the rifle and gently raise it to his cheek. After weeks of prep, this is the moment, and once he fires, it will be over one way or the other. “I’ve had it go both ways, where I wasn’t able to stay calm, or where I was shaking and breathing heavy, or I’ve broken a twig [and scared the deer off]. But there are other days where you’re able to be in the moment and be calm, take a breath and make the shot and successfully harvest that animal.”

on purpose. If a wounded animal crosses into the park after being shot, it’s a bureaucratic pain in the butt for everyone. So, no, being near the national park is not what draws hunters to this area.

When things go right, a full freezer to start the winter is a hunter’s reward. Simple in a way, but White admits, “I’ve never been involved in an activity that’s so contentious.” Many people would be perplexed by a biologist shooting an animal on their weekend.

Protected areas, like national parks, are full of these apparent juxtapositions. Sometimes land managers preserve forests; sometimes, they burn them. Some fish get protected while others get exterminated. Some men and women work all week to protect wildlife from human interference like trains, open picnic boxes and habitat destruction. And a surprising number of them fish and hunt outside of the parks on their days off. As odd as this may seem, it has a long history. The Alberta Wilderness Association, for example, was started by hunters in the 1960s, and there have been avid hunters in the Parks Canada warden service since its inception more than 100 years ago.

“It’s a matter of habitat,” White explains. Hunters are there despite the possible hassle, for the same reason the animals are because it’s some of the only good wildlife habitat left in the Bow Valley. The growth of the town of Canmore on one side, coupled with good foraging of the Fairholme prescribed burn of 2003 on the other, has made the tiny slice of land a busy wildlife area. Hunters, biologists (and likely the animals themselves if you could ask them) all agree the greatest threat to wildlife is habitat reduction due to human development.

There was a time when animals and hunters roamed freely in the Bow Valley (before there were national parks, golf courses and condo buildings), and there was no perceived contradiction between conservation and hunting. The first humans on this landscape hunted freely. And when Treaty 7 was signed in 1877, it stated these First Nations retained the right to use the land for hunting.

In 1885, when the first slice of what would become Banff National Park was protected, wildlife was considered “game” and the Ministry of the Interior’s stated management goal for wildlife was to benefit the tourist experience while providing residents with “wild meat”.

If you are driving west from Canmore on the TransCanada Highway on a fall morning, you’re likely to see a truck or two pulled into the broad grassy ditch running through the Bow Valley corridor. The vehicle’s owners have parked and, shouldering their hunting bows, hiked up onto the sunny terrace between the multi-lane highway and the peaks of the Fairholme Range. Seeing hunters so close to protected land, you may imagine them waiting for unsuspecting animals to cross the boundary, but during hunting season, wardens patrol the park boundary regularly, and hunters rarely cross it

But Indigenous harvesting was never seen as favourable by the settlers of this area—regardless of what Treaty 7 stated. In 1894, the assistant commissioner of Indian Affairs, A.E. Forget, wrote, “kindly also have orders issued that no Indians are to be allowed to hunt or trap within the limits of the Rocky Mountain Park. The N.W.M. Police have been asked to cooperate with you in enforcing this prohibition by driving out of the park any Indians found hunting or trapping therein.”

To further help enforcement, Park Superintendent Howard Douglas helped create the Game Guardians that would be the start of the Parks warden service. These early wardens had the conflicting tasks of both protecting wildlife and “killing pests,” which, at the time, could include hunting predators such as wolves, in an attempt to increase other populations. In part, due to hunting, wolves were completely driven out of the Bow Valley and wouldn’t return until the mid-1980s.

Travelling on foot far from human development, cresting a windy ridge to see a wild herd of bison below is a powerful experience that recalls a bygone time.

Summertime in the Canadian Rockies is a terrific time, and it means many things to many people.

To some, casting a fly to a rising trout in a backcountry lake epitomizes the season; to others, the months of dirt and dust flying off a 29" wheel bring a rugged smile to their face. No matter which medium you choose to paint your perfect summer canvas, we here at Wild Life Distillery want you to know that we share your passion for the season.

We’ve worked hard at our craft to bring you the perfect ready-to-drink backcountry beverages: Slim 355ml cans, for ease of fitting into your pack; fresh and balanced flavours, to keep your palate clean and uplifted; fun and playful names, to spice up your special occasions. WLD Canned Cocktails are designed with your next adventure in mind. It’s this mountain life that excites us too, a balance that informs every ounce we pour.

For our team, there is nothing more inspiring than hearing stories and seeing photos of special occasions made even better by the inclusion of our product, so we invite you to round up some Thirsty Cougars, pack your gear, and take your backcountry bevvy game to the next level.

Drop us a line @wldspirits

We’ll either be on our own adventures, or hard at work, taking great pride in being a small part of yours.

Happy Summer,

Happy Summer,

- The WLD Team

These days it’s the bison’s turn to return to Banff National Park. In 2018, wild bison were reintroduced after more than a 100-year absence. Through the reintroduction of this keystone species, managers hoped to improve ecosystem integrity and cultural connection. Five years on, most people see it as a great success and White has been lucky enough to be a part of the team monitoring the animals, maintaining fencing and writing reports.

By January, winter has eclipsed hunting season and White dons skis to cover 100 kilometres of remote backcountry on a four-day field trip. With heavy packs, he and his teammates ski to a series of tiny backcountry patrol cabins. They are collecting bison dung along the way and carrying it back to town to learn more about the herd’s diet.

Travelling on foot far from human development, cresting a windy ridge to see a wild herd of bison below is a powerful experience that recalls a bygone time. The return of bison to the park, which began in 2017, has been described as an act of reconciliation. The reintroduction started with an Indigenous blessing ceremony and a Parks promise to engage all Treaty 7 Nations throughout the project.

Parks has recently released a report on the project’s first five years, and though there is no mention of hunting, it’s easy to see that the herd is growing (projected to hit 200 animals within eight years), and that land for them to roam is limited. If all goes well, they will likely need to be culled to some degree, as elk around Banff and Jasper have been in years past.

The Stoney Nakoda Nations, who once hunted wild bison on this land for subsistence and included the animals in their cultural and spiritual practices, have released their own report on the project. Enhancing the Reintroduction of Plains Bison in Banff National Park Through Cultural Monitoring and Traditional Knowledge states that they, too, see the reintroduction as an act of reconciliation, and they would like to see the project expanded. It also recommends enhancing the project through ceremony, cultural monitoring, and, eventually, harvesting some of the animals like they had done before the park was established, before they were banned from hunting their traditional lands, and before the bison were driven to near extinction.

Many modern hunters have thought long and hard about the future of wildlife conservation. They have a vested interest, obviously, and they spend a lot of hours sitting quietly. They also see the impacts we all have on the environment. They witness how new developments change wildlife routes or how more hikers on a trail affect when and how animals use it.

Today there are a number of non-profit hunting organizations like Backcountry Hunters and Anglers, and Ducks Unlimited who advocate for research, habitat restoration, and the protection of public lands that support the needs of both people and wildlife.

When the rest of us bike past a deer or a bear on the trails, we rarely stop and observe them for hours or return week after week to check on them as hunters do. We’ve likely already scared the animal by the time we spot them. Even supposed low-impact sports affect wildlife daily. In contrast, hunters try hard not to be noticed: camouflaging themselves, quietly hiding behind bushes or blinds, some even conceal their scent by wearing clothes left in airtight containers when they aren’t in the field. Hunters have as little impact as possible on wildlife until they have a final, fatal impact.

Some differentiate these types of recreation as

consumptive (hunting and fishing) and non-consumptive (our outdoor sports that impact wildlife differently) which hints at societies mindset. But is hunting really recreating? Or is it human’s natural role in the ecosystem? There’s a discussion to be had there that wouldn’t be entirely comfortable at most dinner parties. But between hunting and conservation, urban growth and environmental preservation or even colonialism and reconciliation, is the messy middle ground where White spends a lot of his time.

“I was drawn to hunting by working conservation and studying biology. And through hunting, I’ve been inspired to continue with that work. Being a conservationist has made me a better hunter, but being a hunter has made me a better conservationist, too. Thinking back to my master’s degree, the time spent in the field hunting gave me the ability to see things on the landscape and not just on the computer screen of wildlife data. You need that balance of being out there.”

“In a utopian world, we’d all see the benefits of hunting, and hunters would be very conservationminded and ethical. I acknowledge that there are people that don’t do it ethically. But ideally non-hunters would recognize the role the hunters have to play in conservation as well. That’s a piece that’s forgotten.”

In 1961, the damming of the Columbia River in Canada flooded fertile valleys and old-growth forests, it displaced people, killed wildlife and forced Indigenous nations from traditional land. The 60-year-old treaty that affected the lives of thousands is currently being renegotiated.

words

Flames licked up the side of houses in Grahams Landing. They were the last of the buildings to be torched in this farming community located in the fertile narrows between Upper and Lower Arrow Lakes. By October 1968, work had been completed on the Hugh Keenleyside Dam upstream of Castlegar—six months ahead of schedule.

Spanning the valley for nearly a kilometre, this concrete and earthen dam was the second of three Columbia River Treaty dams. The Mica and Duncan were the other two that Canada would build as part of its obligations under the Columbia River Treaty signed with the United States in 1961 and ratified three years later against a backdrop of grassroots protest and controversy. Canada was also required to provide 15.5 million acre-feet of water storage annually (an acre foot is enough to cover a football field in a foot of water). In addition, the treaty gave the U.S. the right to build a fourth dam at Libby, Montana, which would flood a swath of southeastern British Columbia for water storage.

It was a far-reaching agreement aimed at protecting communities in B.C., Washington and Oregon from flooding and generating hydroelectricity.

In the name of downstream flood control, the waters of the Arrow Lake Reservoir were soon to rise and submerge upstream communities in Burton, Fauquier and Grahams Landing.

“Around 2,100 settlers were displaced. A third relocated to New Burton and New Fauquier, a third just picked up and left, and a third moved to Nakusp,” says Kyle Kush, a lifelong Nakusp resident and archivist at the Arrow Lakes Historical Society. “The Columbia River Treaty is still a big deal around here. It depends on who you talk to. Some people say it was a positive thing, others say it was negative.”

Many of the forcibly relocated lost their livelihoods and were impoverished. The Hugh Keenleyside dam sat on top of what was then Daisy Welsh’s family property at a rural farming community known as High Arrow.

“Going back to BC Hydro, to the men that represented them, there was no standards. They treated us all like we were just little children,” Welsh describes

in a video interview for the Columbia Basin Trust. “Where did the people of Arrow Lakes stand? They were right down there and taken advantage of in every way possible.”

In Nakusp and other Columbia River communities, the politics of water are never far from mind even 60 years after the ink dried on the Columbia River Treaty. Nor are they among the Secwepemc, Ktunaxa and Okanagan Nations whose territories lie within this vast watershed; the Columbia River Treaty cut to the core of who they are as a culture and people. This is also traditional territory of the Sinixt Nation which was literally rendered invisible by a 1956 Canadian government decision that conveniently declared them extinct. Since then, they’ve had to fight to prove that they exist, culminating in a landmark 2021 decision by the Supreme Court of Canada recognizing their right to hunt and fish across the international border in a territory spanning from Washington State to Revelstoke.

Unpacking this treaty is like opening a Pandora’s box as complicated as the swirling currents of a glacier-fed river. Now this complex treaty is being modernized and First Nations have a seat at the table.

• Communities flooded by Dams

* treaty dams

power dams

united states

On a warm summer morning, an osprey perches regally on a dead snag above the north end of Columbia Lake near Canal Flats in southeastern B.C. Mule deer browse willows nearby, flicking their ears at the annoying buzz of mosquitoes. A slow current gathers at the north end of the lake where the Columbia, the fourth largest river system on the continent, begins its peaceful unassuming life. From there it heads northward, soon meandering through the rich wetlands of the Rocky Mountain Trench, home to more than 260 species of birds.

As it flows past Golden, the Columbia gathers force, fed by tumbling tributaries like the Kicking Horse, Blaeberry and countless other mountain rivers. After the river passes beneath the Trans Canada Highway at Donald, it enters the Kinbasket Reservoir, a

slack, ecologically bankrupt body of water that rose behind the Mica Dam in 1973. In a rush to flood this valley bottom forest and riparian habitat, just 20 per cent of an estimated 5 million cubic metres of timber

The tree stumps on the shore of the Arrow Lakes, Kinbasket, and Lake Koocanusa reservoirs are a vivid reminder of what was and what became of these once pristine valleys and landscapes filled with old growth cedar, white pine and fir.

was harvested ahead of the rising waters. The rest was submerged and wasted. That was the ethic of the era; get it done as fast as possible and never mind the ecological and human cost. To say

the impacts of human interference on the Columbia River are profound barely even scratches the surface. The tree stumps on the shore of the Arrow Lakes, Kinbasket, and Lake Koocanusa reservoirs are a vivid reminder of what was and what became of these once pristine valleys and landscapes filled with old growth cedar, white pine and fir.

When it was negotiated, the terms of the treaty were narrow, and by the narrow terms of flood abatement and power generation it could be called a success. It helped avoid billions of dollars in flood damage and generated billions of dollars in electricity for Canada and the U.S. Back then, the environmental movement was nascent and the concept of Indigenous rights and title unheard of.

In the ensuing years, the negatives have piled up as the impacts of dams and reservoirs have been studied by groups like the Northwest Power and Conservation Council. For example, more than 40 per cent of steelhead and salmons spawning and rearing habitat in the Columbia River Basin has been lost. The concept of clean hydroelectricity also needs a rethink. BC Hydro, the provincial Crown corporation that manages the power grid, still touts hydroelectricity as green power, but it’s a simplistic term that masks the ecological and human costs of its generation. The Columbia

construction of Washington State’s Grand Coulee dam in 1941.

“We took one of the greatest natural ecosystem powerhouses on the planet and shut it down to produce electricity,” wrote William Sandford, Deborah Harford and Jon O’Riordan, coauthors of the book The Columbia River Treaty: A Primer “Dam construction caused convulsions throughout the entire natural energy cycle of the Columbia River.”

Though there remains much work to be done on true reconciliation, Canada’s appreciation—and recognition—of Indigenous

people, in the words of Sandford, Harford and O’Riordan: “In the minds of Treaty-makers, Indigenous interests were non-existent …”.

In 1972, when the Americans completed the Libby Dam on the Kootenai River in Montana, it flooded Ktunaxa territory in B.C. Neither government asked nor consulted this East Kootenay First Nation. Their losses were simply collateral damage in a transnational flood control and power scheme.

“It’s been over 80 years since the Ktunaxa have been able to harvest salmon within the Columbia Basin,’ says Kathryn Teneese, chair of the Ktunaxa Nation Council who is shaping treaty negotiations along with representatives from Secwepemc and Syilx Okanagan Nations (government chose not to include the Sinixt). “Overall, the impacts are immense.”

River salmon that nourished people and ecosystems, and once counted hundreds of tributaries in the Columbia and Rocky Mountains, were decimated in a process of river management that started with the

rights has advanced light years since the 1960s when they were universally ignored. From the flooding of burial sites and hunting grounds to the loss of salmon, the treaty had “catastrophic consequences” on Indigenous

They lost precious mountain caribou habitat and some of the best agricultural lands. Cultural sites were damaged and destroyed. Teneese says the submersion of waterfalls on the Kootenay and Columbia rivers cannot be measured but their “importance to the Ktunaxa is very high.”

Bringing salmon back to this tortured watershed is a monumental undertaking that could require the building of complex fish ladders to allow salmon to bypass dams.THIS PAGE Revelstoke Lake Reservoir above Revelstoke Dam. PREVIOUS SPREAD "Vitamin Hope," the waters of the Columbia River. PREVIOUS SPREAD MAP Directional flow and major dams on the Columbia River. Credit: A River Captured: the Columbia River Treaty and Catastrophic Change and the Nelson Museum.

She says the elders have made it clear—a modern treaty must include reconciliation and redress for what happened to the Ktunaxa.

“It needs to include significant reductions in the ecological and cultural impacts of the operation of the treaty dams and reservoirs, support for salmon restoration, full participation in the governance of the CRT system and in the economic benefits of the treaty,” Teneese says.

Wayne Kukpi7 Christian, a former Splatsin chief and chair of the Shuswap Tribal Council, is one of the leaders who lobbied the federal government to get Indigenous representation at the negotiation table. We’re in the room now; we weren’t before,” he says. “Bringing salmon back is central to what we want. It was a resource that ensured our people would survive. But it was more than a food source, it was a way of life.”

Spawning salmon once migrated to the north end of the wild Columbia’s natural arch through B.C., near a place known as “Big Bend.” Not anymore. This is where the tamed Columbia springs back to life from the doldrums of the Kinbasket reservoir and roars through the spillways of Mica Dam. From there, it courses through the steep sided valley dividing the Monashee and Selkirk mountains. It has become a glacier-fed powerhouse—literally. The Mica has capacity to generate 2,746 MW (megawatt)—enough electricity for two million homes.

But the river’s sudden freedom to flow is short-lived. In less than 50 kilometres, it swirls to a standstill at Lake Revelstoke, a reservoir formed after the government constructed the 2,480-MW Revelstoke Dam and generating station in 1984.

That is the ultimate trade-off when it comes to massive hydro-electric projects. Sacrifice the natural life of a river, hundreds of thousands of hectares of terrestrial habitat,

From the flooding of burial sites and hunting grounds to the loss of salmon, the treaty had “catastrophic consequences” on Indigenous people.ABOVE Shelly Boyd, member of the Sinixt Nation and Arrow Lakes Facilitator of the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation. BELOW Sockeye salmon.

birds, deer, bear, mountain caribou and myriad other wildlife species, in exchange for the luxury of taking endless showers in water heated by cheap hydroelectricity.

What really burns about the original Columbia River Treaty for many people is B.C.’s defacto role as a place to store water. When the Hugh Keenleyside was first commissioned it was for flood control only (it wasn’t until 2000 that a 185-MW power generation plant was added). The dam on the Duncan River, a tributary watershed that once teemed with waterfowl, still has the no other purpose than to retain water for American interests.

“The Duncan produces no electricity, and destroyed what was a very large and very rich ecosystem largely to support hydroelectric generation south of the border,” said Rod Retzlaff in a recent letter to the Nelson Star. “The Duncan Valley and Kootenay system are too valuable for us to continue to allow the Americans to use them as a big storage tank.”