African Modernism

Works from The Collection of Helen Elaine Jackson

Works from The Collection of Helen Elaine Jackson

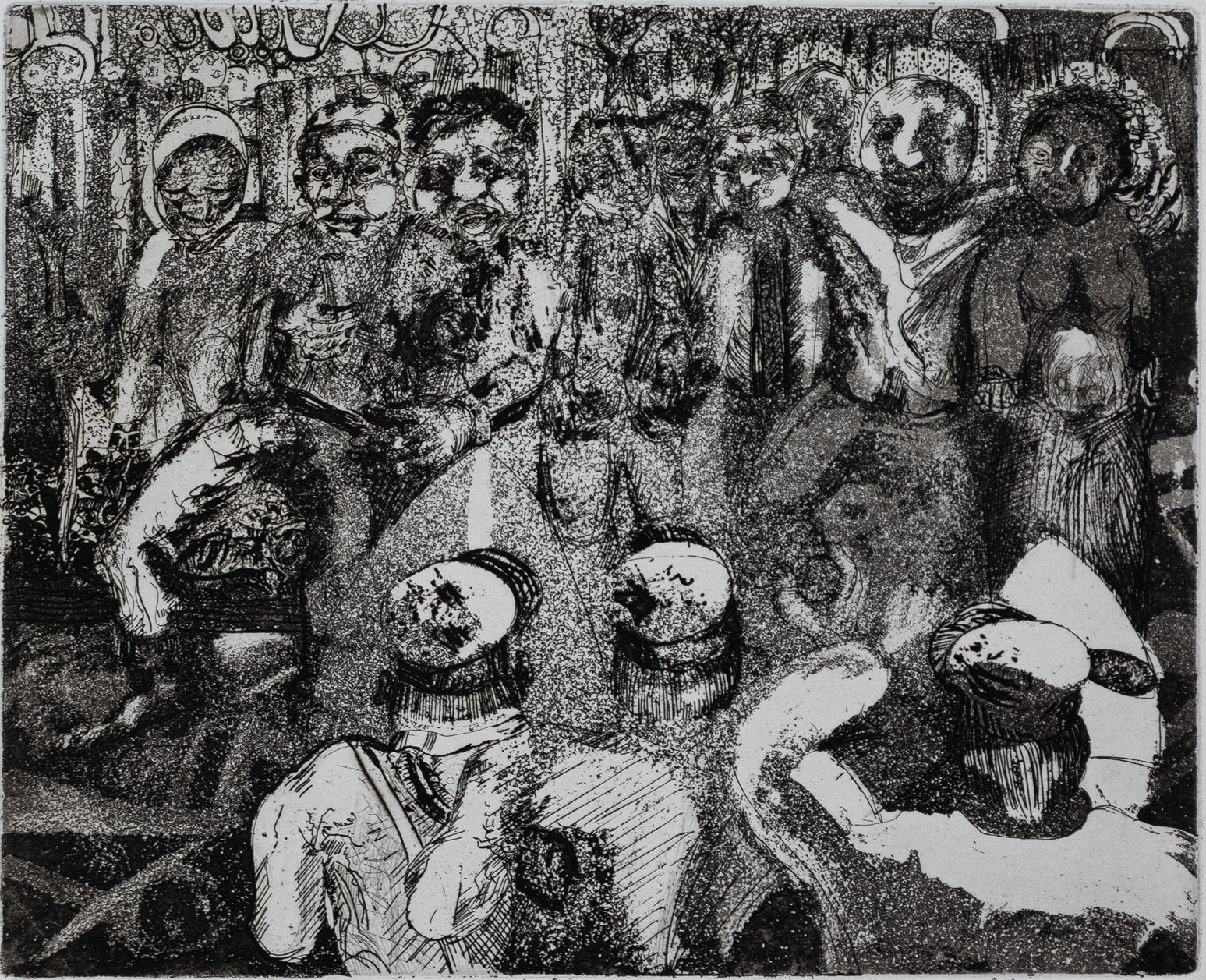

Zwelidumile Geelboi Mgxaji Mhlaba “Dumile” Feni (1942 – 1991), Voices from Exile, 1985; offset lithographic poster from Voices From Exile: The South African Exhibit Project, 24 x 18 inches.

Helen Elaine Jackson operated the wellknown art gallery, Capitol East Graphics, from her home at 600 E Street (SE) in Washington, D.C. for four decades, meeting and representing the work of artists from all over the world. Helen also arranged significant exhibitions outside her gallery, such as Voices From Exile: The South African Exhibit Project, which was showcased at the Peace Museum in Chicago (1980s) and a 2018 exhibition at the Brentwood Arts Exchange (MD) which featured graphic works from the African Diaspora.

Helen Elaine Jackson was born in 1946 in Washington, D.C. Her parents were Marion and Thelma Jackson, and her grandfather was Thomas Buchanan Frost, who founded Jarvis Christian College, an HBCU in Hawkins, Texas in 1912.

She attended public schools in Washington, D.C. growing up, graduating from Roosevelt High School. She attended Goddard College in Vermont and earned her BA. She also spent a year at a language school in Lausanne, Switzerland, but returned home upon the news of the death of Martin Luther King, Jr. Helen began studying at George Washington University as an art major upon her return. She also studied printmaking at the Art Student’s League. In the 1970s, she began working as an associate editor at Doubleday Publishers in New York City. At Doubleday, she promoted writers of the Caribbean diaspora. This interest evolved into her independent project, Antillean Bookshelf, which supported contemporary writers of the region.

Helen was brought back to the D.C. area when she inherited a house, and that prompted the birth of Capitol East Graphics. The gallery had a special focus on graphic media, but artists whose work was represented were from the U.S., Europe, Africa, and the Caribbean. Jackson said,

“They could expect me to show AfroAmericans and maybe even famous black artists like Romare Bearden, but when they see these major printmakers from Yugoslavia and Israel and Paris and Stockholm, it throws ‘em” (1)

In 1983, she presented a group exhibition which included works by Ed Clark, Norma Morgan, Herbert Gentry, Vincent Smith, and Earl Miller, among many others. Voices From Exile: The South African Exhibit Project was a touring exhibition sponsored by the Association for the South African Exhibit Project, which presented the work of several Black South African artists who had been forced to live outside their homeland due to the limitations placed on their creative professional expressions by the apartheid system. The Association for the Defense of Artists-USA (AIDA-USA) was a co-sponsor of the project.

signed and dated, 5 ‘89

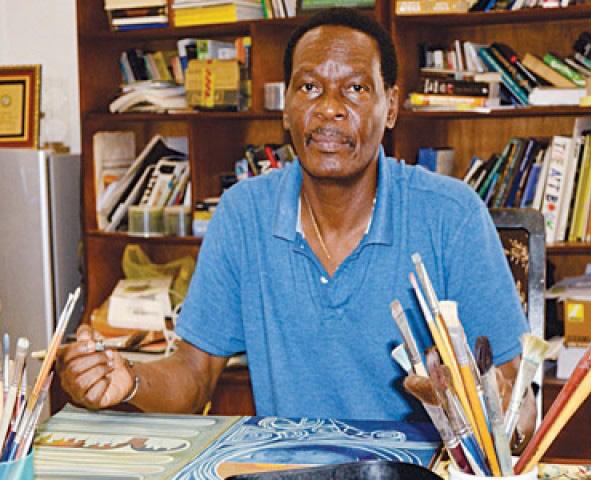

Tayo Adenaike, who is of Yoruba parentage, was born in 1954 in Idanre, in southwestern Nigeria. He studied art at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka, where he received his bachelor’s degree in 1979 and his master’s of fine arts degree three years later. Since graduating he has largely worked in advertising, and he currently serves as artistic director of Dawn Functions, Ltd., a major Nigerian firm in Enugu.

Although he occasionally works in oil and acrylics, Adenaike’s forte is watercolor on paper. A gifted watercolorist, Adenaike deftly utilizes uli styles and akika, traditional wall uli background swirls. In recent years he has incorporated nsibidi motifs into his richly colored compositions and sometimes combines both design forms in one work.

His complex designs are based on personal reflections, political commentaries, scenes from everyday life, portraits, and animal forms. Adenaike’s work is topical and at times deeply personal, with subconscious elements. Human faces, distorted or in agony, often appear in his work. Inspired by his Yoruba childhood and life experience, Adenaike creates works that explore Igbo and Nsukka styles with uncommon insight.

As a painter, Adenaike has said that he views himself as a third generation painter, a successor to fellow Nsukka artists

Uche Okeke and Chike Aniakor in the first generation and his teacher Obiora Udechukwu in the second generation.

The Nsukka group is the name that was given to a group of Nigerian artists who were associated with the University of Nigeria, Nsukka in the 1970s. They are especially known, as a group that was working to revive the practice of uli (the traditional designs drawn by the Igbo people of Nigeria) and they incorporated its designs into contemporary art using media such as acrylic paint, tempera, gouache, pen and ink, pastel, oil and watercolor.

Tayo Adenaike has held eighteen solo exhibitions and participated in many joint and group exhibitions in Nigeria, United States, England and Germany.

REF: National Museum of African Art

Photo: The Guardian Nigeria, April 19, 2015

15-1/2 x 21 inches (image)

20 x 28 inches (sheet)

signed, dated and numbered 34/78

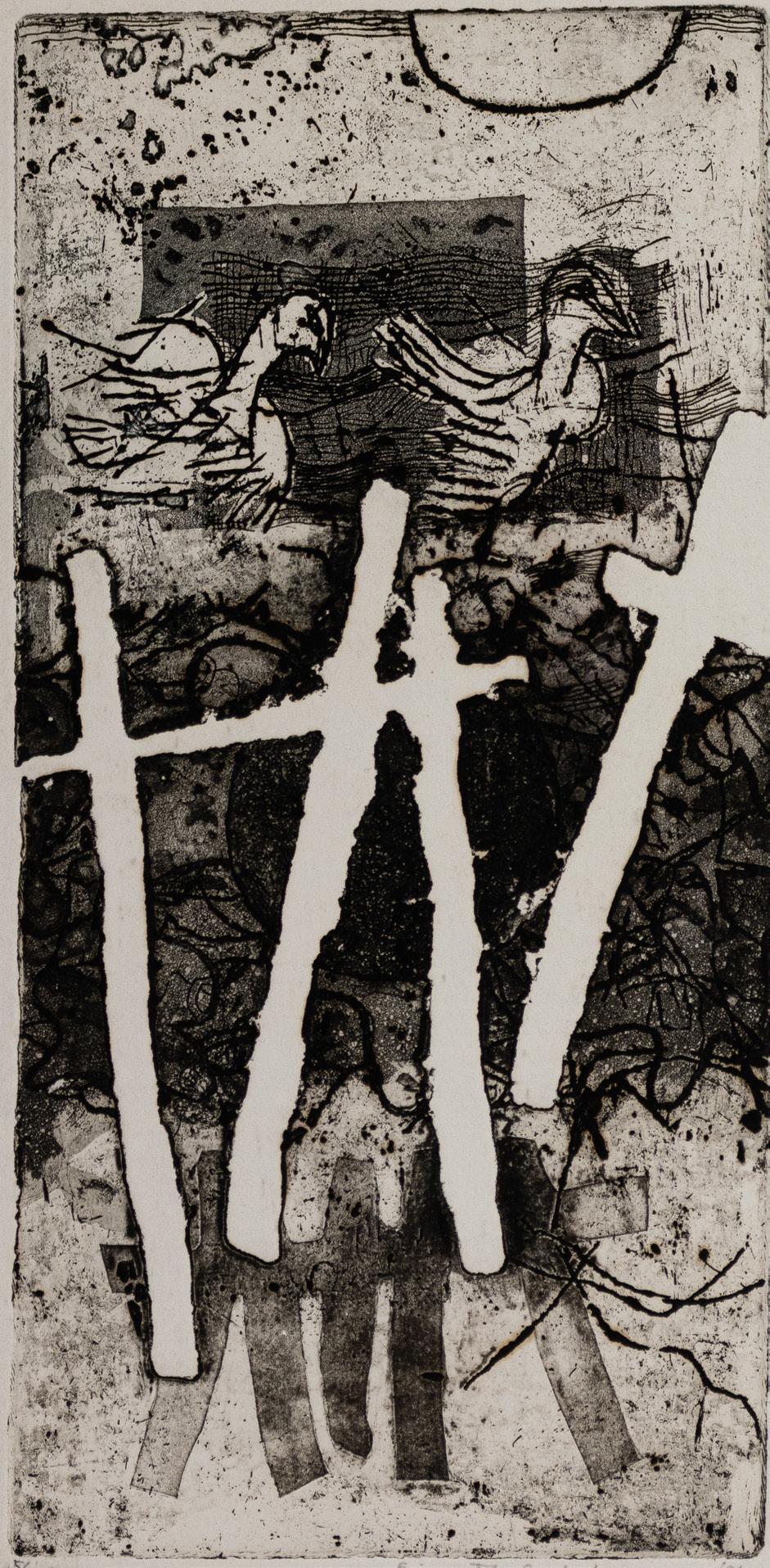

Bongiwe Dhlomo-Mautloa is a Zulu South African printmaker, arts administrator and activist.

She was born in Vryheid, KwaZulu-Natal, and educated at St Chad's School in Ladysmith and Inanda Seminary School. She furthered her studies at Rorke's Drift Art and Craft Centre studying printmaking and gained a diploma in fine arts. She worked at the African Art Centre in Durban (19801983), then at the Grassroots Gallery in the same city, before moving to Johannesburg where she curated exhibitions at the FUBA Gallery and the Goodman Gallery.

She was a founder and project coordinator of the Alexandra Art Centre in Johannesburg. She was Outreach and Development Project Coordinator of the 1995 Johannesburg Biennale, which was called Africus, and was the administrator of the 1997 event, titled Trade Routes: History and Geography.

She has said that the Soweto uprising of 1976, when she was aged 20, politicised her, and her prints have been described as

"always political, documenting such historical events as the 1976 Soweto uprising as well as less overtly political activities such as women working".

In April 2023, Dhlomo-Mautloa was bestowed the National Order of Ikhamanga (Silver) by the South African Government for her contributions to arts.

REF: “Bongiwe Dhlomo-Mautloa.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 22 May 2023, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bongiwe_ Dhlomo-Mautloa.

13-1/2 x 9-1/4 inches (image)

19-1/2 x 13-3/4 inches (sheet)

signed, dated, titled

South African artist who was a member of the Artist Proof Studio as a mentor and teacher. The Artist Proof Studio (APS) offers a three-year printmaking-training program to diverse young people from across South Africa as well as neighbouring countries. Co-founded by the artists Kim Berman and Nhlanhla Xaba who act as mentors and teachers, this community-based arts organisation was built in the spirit of the country’s first democratic president, Nelson Mandela’s insistence on reconciliation and reconstruction. The two individuals came from two different backgrounds of Gauteng to build a multiracial printmaking centre. Currently the Studio trains 80 to 100 students yearly in drawing, printmaking, business skills and visual literacy. These young, dynamic artists continue to populate the South African visual arts landscape.

Donga’s work was included in the exhibiton, The Boston - Jo’Burg Connection: Collaboration and Exchange at the Artist Proof Studio, 1983-2012, held at the Tufts University Art Gallery, Medford, MA in 2012.

REF: Artist Proof Studio | South African History Online, www.sahistory.org.za/article/ artist-proof-studio. Accessed 6 Sept. 2023.

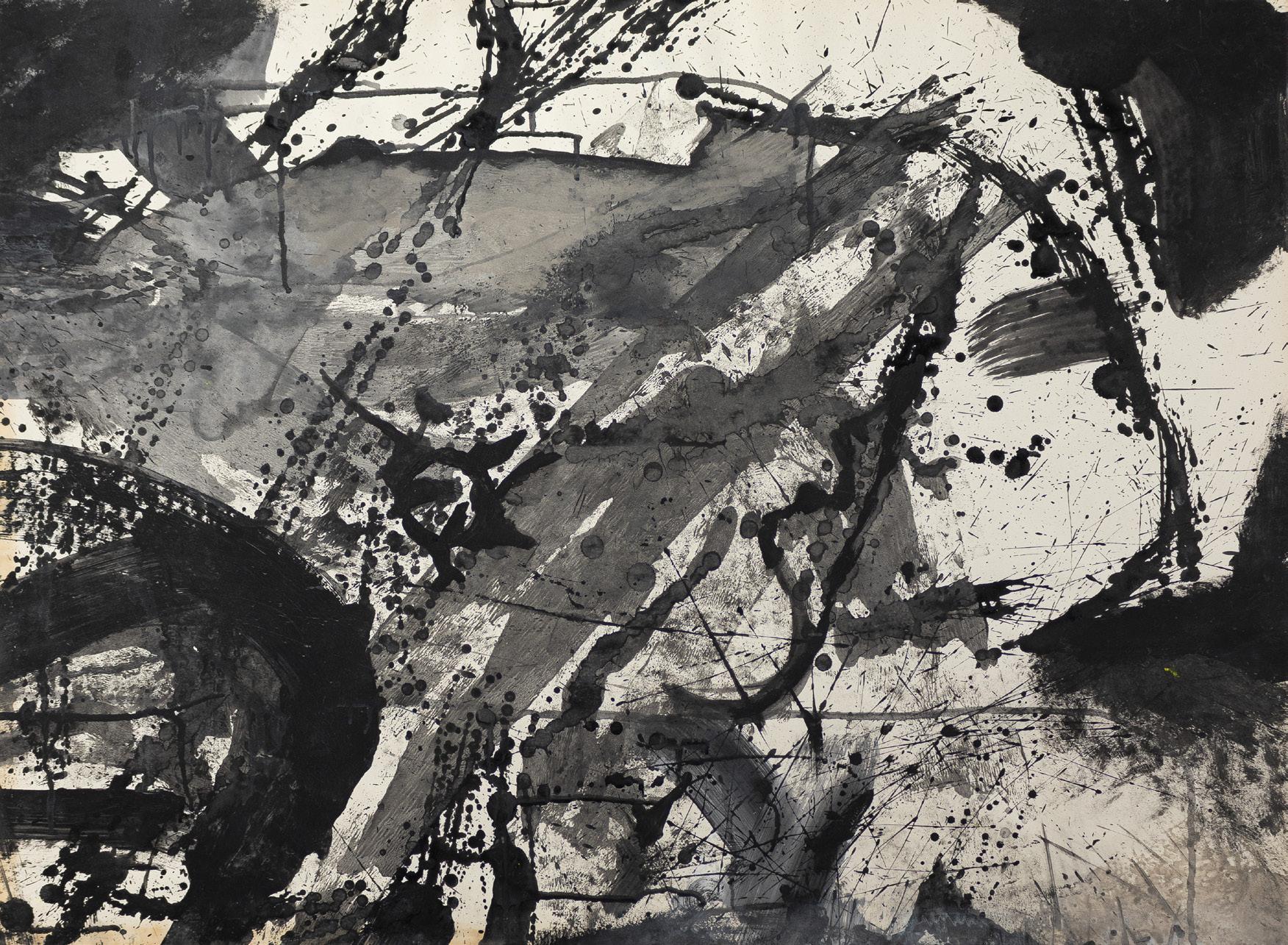

ink drawing

16

24 x 18 inches (sheet)

signed and dated

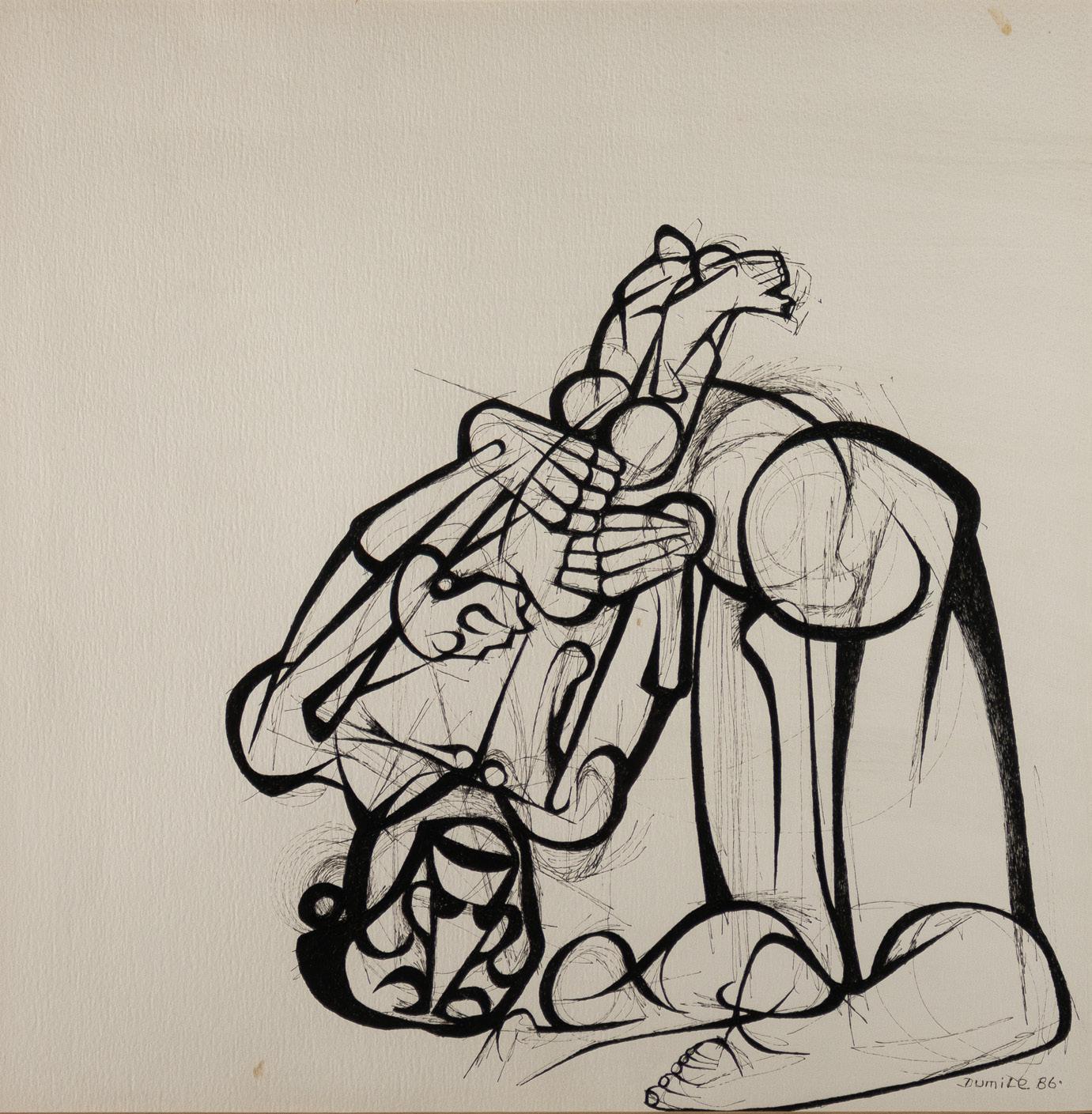

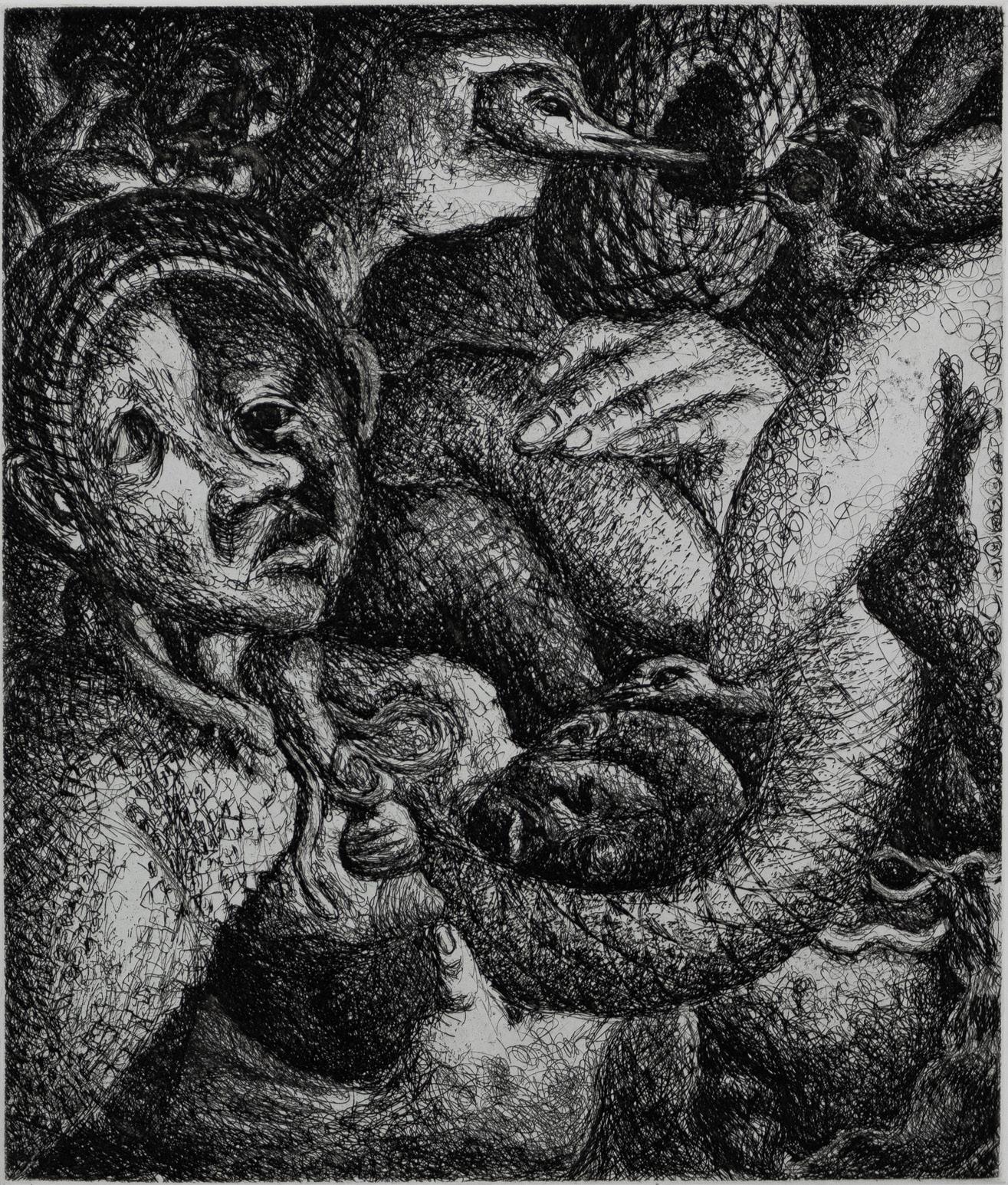

Dumile Feni was a South African contemporary visual artist known for his drawings and paintings that included sculptural elements as well as sculptures, which often depicted the struggle against Apartheid in South Africa. Although his work was featured in numerous exhibitions in South Africa and across the globe, he lived in exile and extreme poverty for most of his art career.

Feni was born on 21 May 1942 in Worcester, Western Cape. His mother died when he was only five or six years old and he went to live with relatives in Cape Town until the age of eleven when he began working for his father, a trader and preacher.

While travelling, Dumile continued to exercise his childhood passion for carving and drawing. In the early 1950s he moved to Johannesburg and began working as an apprentice at the Block and Leo Wald Sculpture, Pottery and Plastics Foundry in Jeppe. In 1963 and 1964, while a patient at the Charles Hurwitz South African National Tuberclosis Association (SANTA) Hospital in Johannesburg, Dumile was given art materials, with which he decorated numerous walls in the hospital.

Dumile exhibited successfully for a number of years in Johannesburg and was selected as one of the artists to represent South Africa at the 1967 Sao Paulo Biennale. However, he was severely criticised by his fellow artists in Durban-where he was living at the time- for being disposed to represent the apartheid regime on an international exhibition. On his return to Johannesburg and faced with the prospect of being deported to either Queenstown or Worcester under the notorious Pass Laws, Dumile

decided to go into voluntary exile in London. He arrived there at the beginning of 1968. In London, Feni exhibited at the Grosvenor Gallery and Camden Art Centre.

In 1979, Feni relocated to the United States, where he made his home in Los Angeles and New York City. He made a living designing record covers and illustrating books, posters, and calendars. In 1991, shortly before his planned return to South Africa, he died from heart failure while shopping at his favourite music store, Tower Records in New York. His body was returned to South Africa and he is buried in Johannesburg.

Described while in Johannesburg as the ‘Goya of the townships’, Dumile found his subject matter in the life and events he observed around him. Working primarily with graphic art in monochromatic hues, the artist had the ability and vision to transform the particular into the universal. His works also reflect his deep love of music, especially jazz.

REF: South African History Online, Dumile Feni Biography, Sophia Reuss

Contortion, 1986

18

37-1/4 x 26-3/4 inches

signed, dated and inscribed Proof

inscribed, “For Frank.

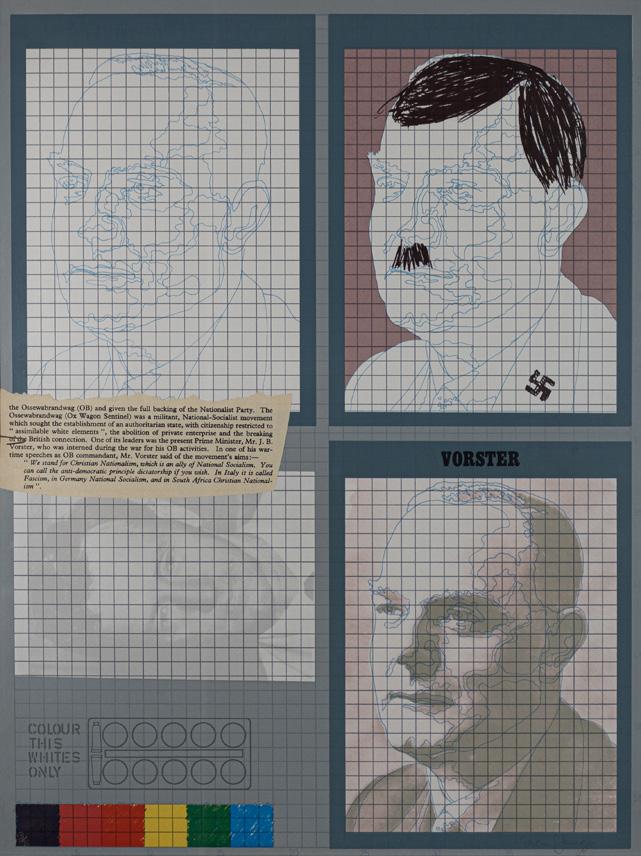

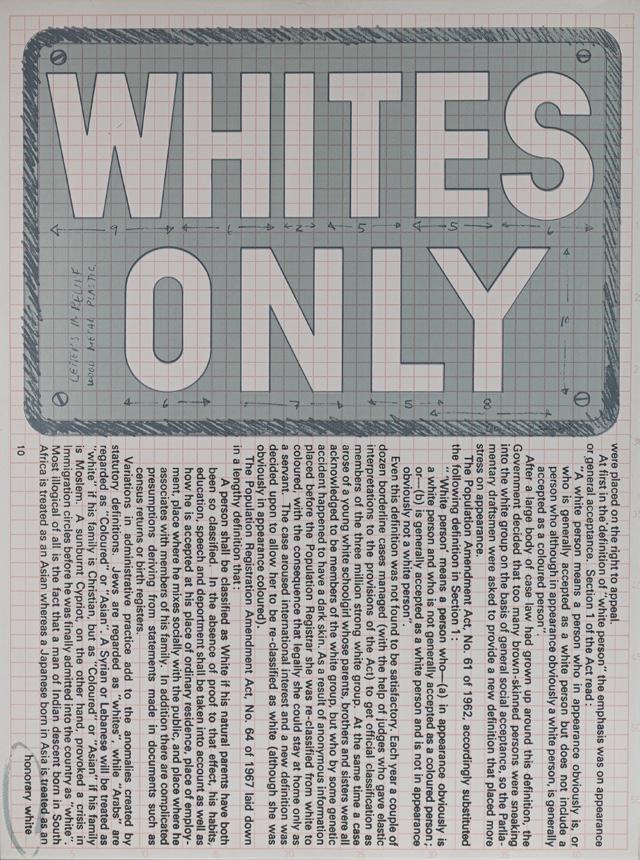

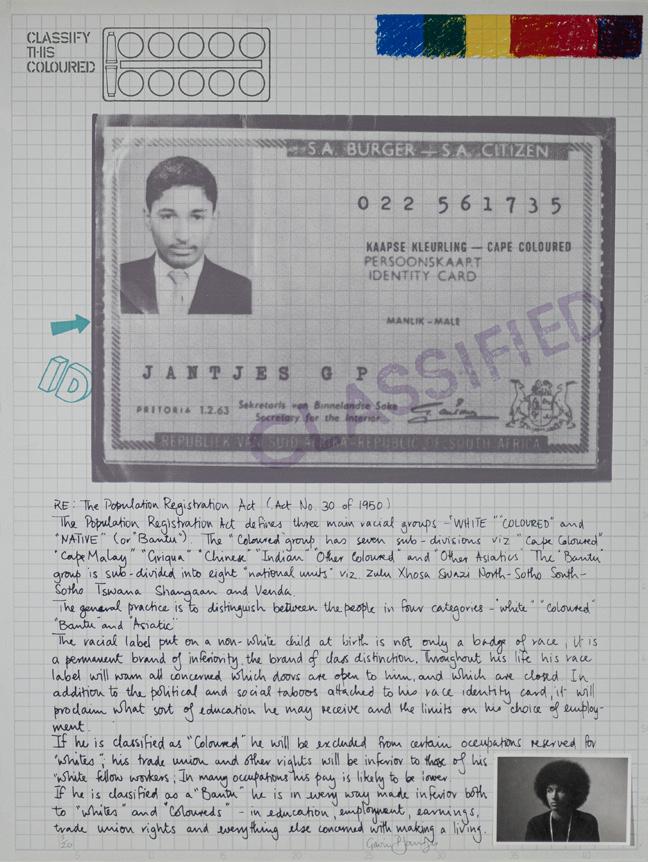

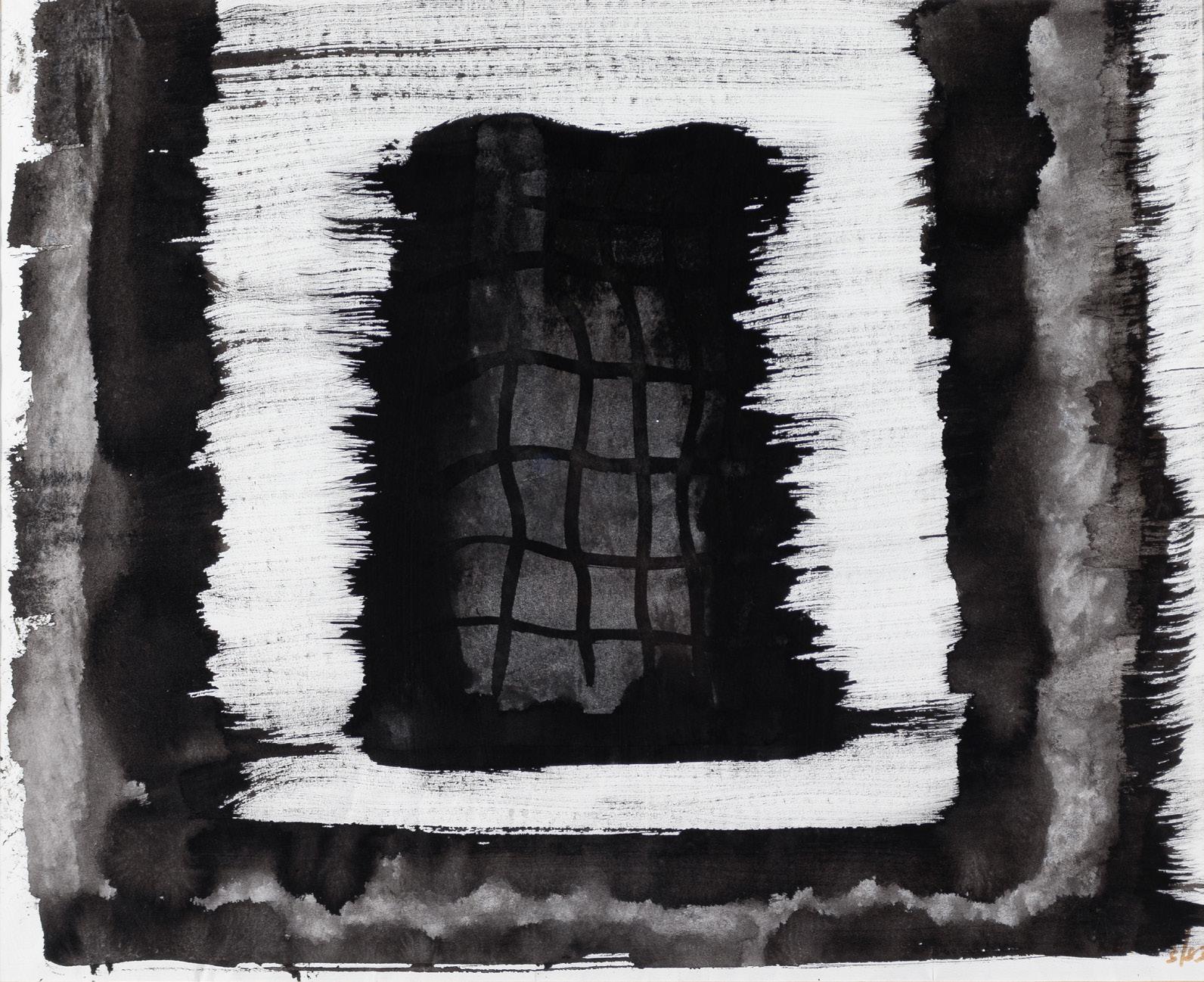

Gavin Jantjes was born in 1948 in Cape Town, South Africa. During his childhood Jantjes had the opportunity to study art at the Children’s Art Centre in District 6. In 1969 he completed his B.A. at Michaelis School of Fine Art, Cape Town.

Much of Jantjes’s artistic practice is undoubtedly shaped by his time spent in exile. He left South Africa in 1970 on a scholarship to the Hochschule für Bildende Künste, in Hamburg, Germany, where he received an M.A. in 1972. He lived and worked in Hamburg from 1970–82, choosing not to return to a country organized around the hate of apartheid. In 1982 he moved to Britain where he was an active participant in the art scene. He curated a number of exhibitions, lectured widely and served on the advisory boards of several galleries.

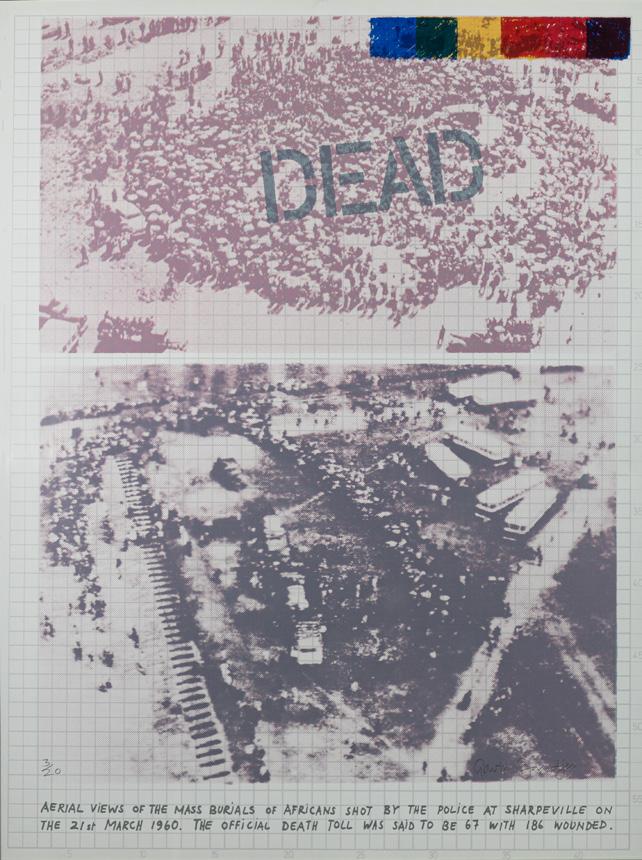

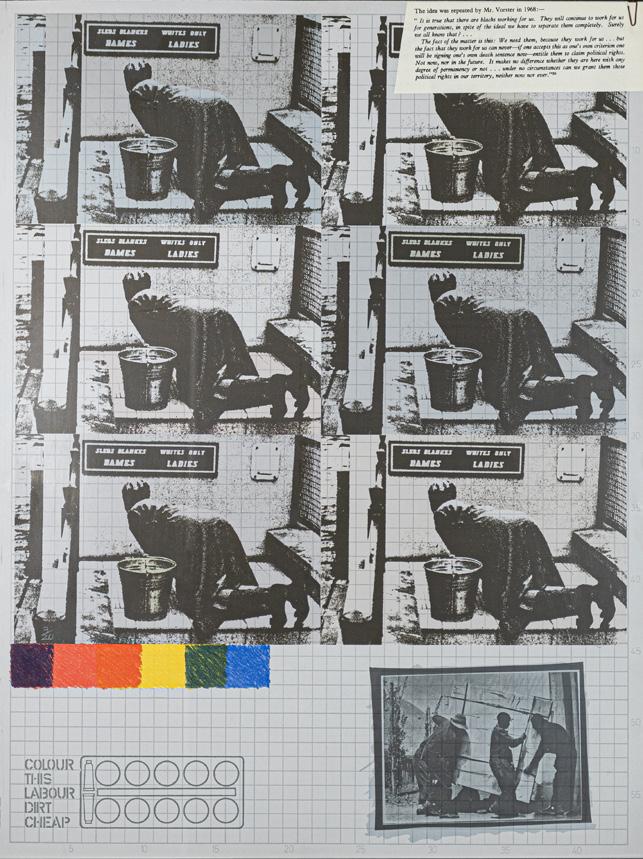

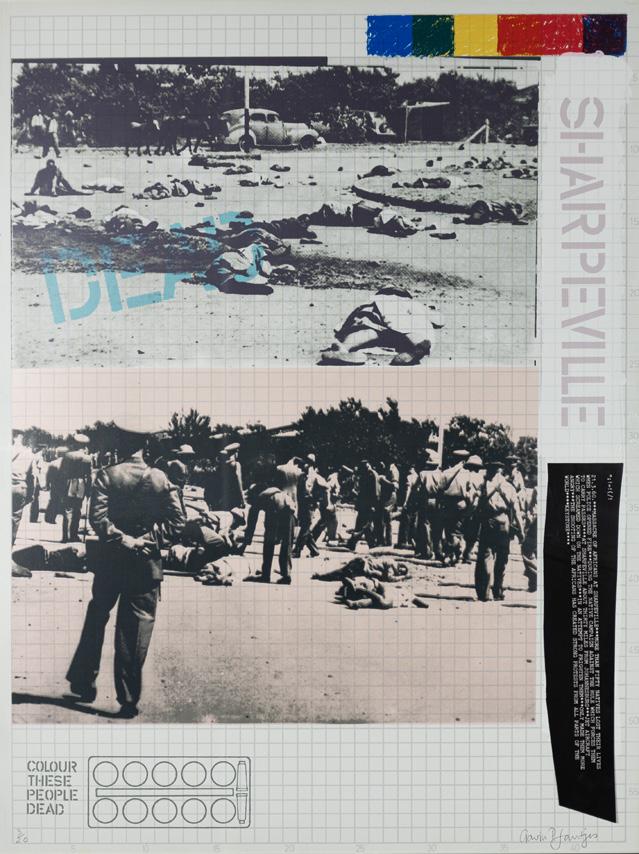

Jantjes is best known for his seminal, work, A South African Colouring Book, a critical commentary on the period of apartheid in South Africa. The work showed the artist’s skill as master printer and collagist

Jantjes’s work has been exhibited extensively and can be found in the collections of several renowned institutions such as the Tate, the V&A Museum, the National Museum of African Art Smithsonian, the Baltimore Museum of Art, the South African National Gallery Cape Town, the Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg, Russia, Gothenburg Art Museum, Henie Onstad Art Center, Oslo, Norway, as well as numerous prominent

private and corporate collections. The artist has also received several commissions from the United Nations Refugee Council and the UN Special Committee Against Apartheid.

During his time spent in the UK, Jantjes served as a trustee of the Tate as well as the Whitechapel and Serpentine Galleries and was responsible for the Arts Council of England’s national policy on cultural diversity. In 2018, Jantjes also took part in the 13th edition of the Biennial of Contemporary African Art, Dak’Art.

Jantjes published Visual Century: South African Art in Context 1907-2007 Vol I-IV, a multi volume publication aimed at contextualizing the role of South African artistic production within the country’s broader cultural identity.

REF: National Museum of African Art, Smithsonian Institution

(south african, B. 1948)

When I began my studies at the Hamburg Art Academy in West Germany, in 1970, I was amazed to discover that my fellow German students, who were politically active in the anti-Vietnam war protests, knew little about South Africa and apartheid. South Africa’s apartheid government was given free rein to propagate its rule as a benevolent system of control on the influence of Communism. In West German popular consciousness, apartheid South Africa was a friend and business partner. In the German media there was little sympathy for the selfdetermination of African people and most mainland European broadcasters presented very few facts about what apartheid meant to the majority of South Africans. When curious young Europeans asked about my home, I often recognised the same ignorance about apartheid in their questions, as the white South Africans, who had not made that daring step across the dividing line into a black South African township. The issues of race and identity within national cultures as postulated by W.E.B. Du Bois and Franz Fanon had not yet penetrated the almost impervious rhetoric of the Marxists, Marxist-Leninist and Maoist student groups of the day, not to mention the conservatives.

Against this background I decided to follow Bertold Brecht’s idea of art as an instrument of political struggle and make a work that could be understood as a tool for knowledge about South African apartheid politics. I also wanted to make this work using the new and popular technologies of photographic silkscreen printing invented for

mass production. Most importantly it allowed photographic images to be integrated into a work of art. Photography in those days represented the real. It was seen as indisputable fact.

My research for ‘A South African Colouring Book’ took me to the offices of the African National Congress (ANC) and the International Defence and Aid Fund (IDAF) in London. Their archives provided some visual and textual material. Many photographs came from Ernest Cole’s seminal book ‘A House of Bondage’ and the German Magazine, ‘Stern’. There was also a great amount of material in the UN and UNESCO archives.

I had to organise the abundant research material into chapters and then edit the material down to one composite image. I understand each sheet of the ‘Colouring Book’ as a heading for a much larger text on apartheid. This also applies to the folder and together these twelve images operate as an archive, perhaps an incomplete one.

The work’s main title has references to art, early learning and politics. I wanted it to conjure an image of early learning and first steps in art, such as painting by numbers, but simultaneously the prints reveal something completely different. The main and sub-titles of the work play with the euphemisms for institutionalised racial discrimination such as ‘the colour question’ or ‘the colour bar’. In cultures where human creativity has a low status, and

art is not taught in schools, the ubiquitous colouring book replaces the encouragement that children need to express their ideas. The prints draw attention to the issue of creativity, to alternative ways of making art. The ‘Colouring Book’ is an extension of European Pop Art ideas of ‘multiples’ and ‘artists’ books’ of the 70s. It mirrors the dichotomy of a brutal and inhuman interior, camouflaged by an exterior of innocence.

Inside South Africa few contemporary artists, myself included, dared to address the issues of apartheid through a direct criticism of the status quo. The political consequences were dire. Some did it indirectly, many avoided it completely. In the late 60s and early 70s, discourses around late modernist abstraction could, and very often, did deflect debate away from the issue of an artist’s role in an undemocratic society. It provided an escape from any political expressions.

‘A South African Colouring Book’ was first exhibited at the Hamburg art academy in 1974. In 1976, at the time of the Soweto uprising, it was on exhibition at the ICA in London and in 1997, upon the request of Joseph Beuys, it was exhibited in the artist’s Free International University space

at Documenta 6. In 1978, after exhibiting the work at the World Council of Churches in Geneva, a replica of ‘A South African Colouring Book’ was produced by the International University Exchange Fund (IUEF) and distributed by the UN Special Commission on Apartheid.

In April 1979 the work was banned under the South African Publication Act.

Copies of ‘A South African Colouring Book’ are held in various private collections as well as the following institutional collections: Victoria and Albert Museum, London (1974); Hellias Foundation for Human Rights, Palo Alto, California (1982); Arts Council Collection, London (1991); The South African National Gallery, Cape Town (1998); Tate Gallery, London (2002); Sindika Dokolo Foundation, Luanda (2016); and the Baltimore Museum of Art, Maryland (2017).

REF: Jantjes, Gavin. “Gavin Jantjes: A South African Colouring Book.” Sothebys. Com, www.sothebys.com/en/auctions/ ecatalogue/2018/modern-contemporaryafrican-art-l18802/lot.79.html. Accessed 14 Sept. 2023.

(south african, B. 1948)

A South African Colouring Book, 1974-75

20 of an edition of 20 + 3APsilkscreen prints on paper

23-¾ by 17-¾inches (each image) signed and numbered 3/20

Source, 1980 silkscreen print 33 x 20 inches

signed, dated and numbered, AP IV

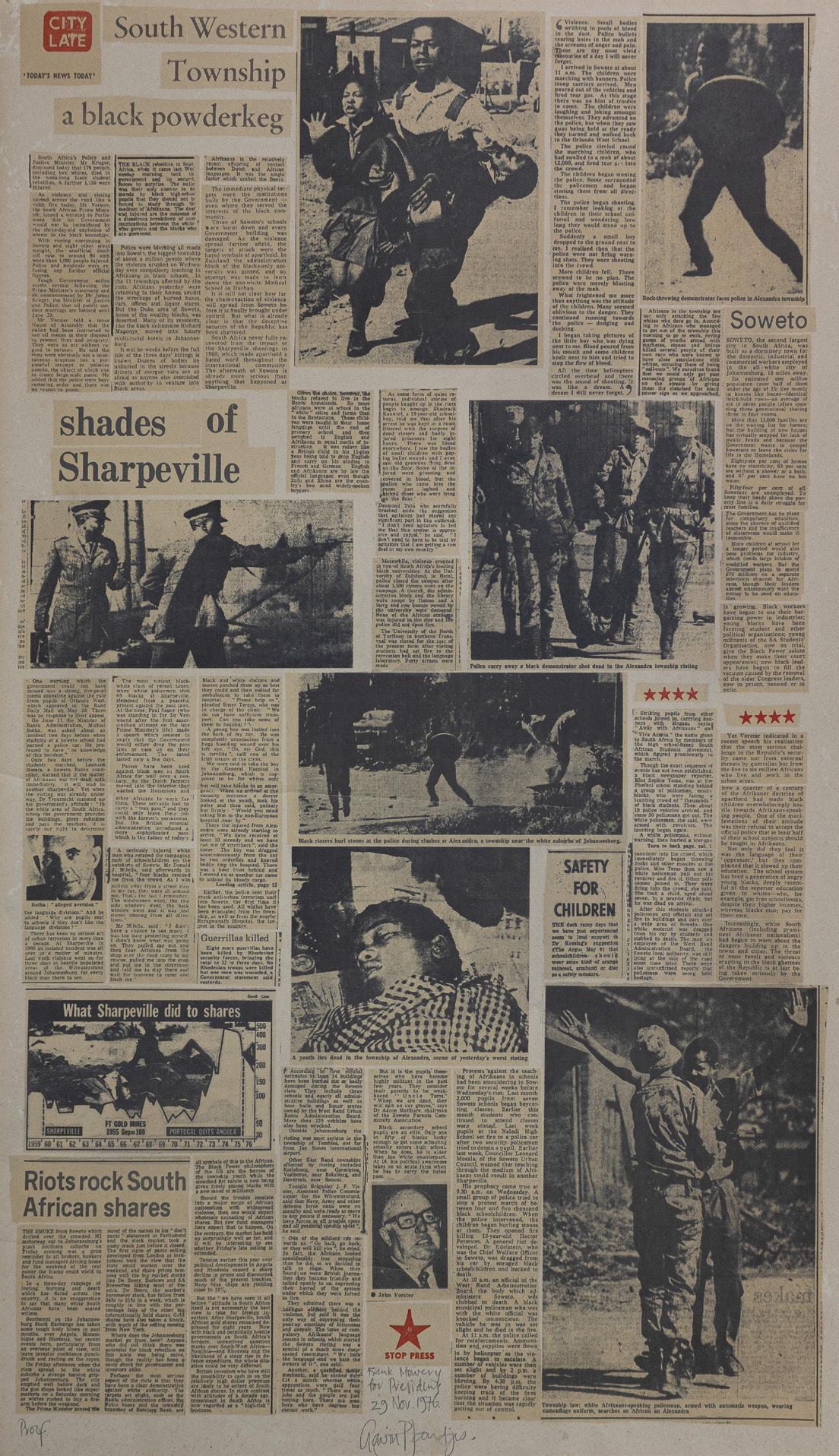

Frank Mowery for President, 1976 screen print on cream paper 32 x 18 inches (image) signed, dated, Nov 29, 1976; titled, with “Proof”

Rosemary Karuga was born in 1928, in Meru in the east of Kenya, to a Ugandan father and a Kenyan mother. Her artistic journey began when an Irish nun at a Catholic primary school noticed her talent and later recommended her to study at the still new School of Fine Art at Makerere University in Uganda. Karuga would, by all accounts, be the influential school’s first female student.

Between 1950 and 1952 she studied design, painting and sculpture at Makerere. After graduating, she moved back to Kenya to become a full time teacher until she retired in 1987 as she approached the age of 60.

It was not until the late 1980s that one of her daughters visited from London and encouraged her to pursue her art practice. The Kenyan art scene in the early 1980s lacked gallery presence, with Gallery Watatu and Paa Ya Paa Arts Centre being the only two active galleries in the capital city Nairobi. It was through an artist-in-residency position at Paa Ya Paa that Karuga’s work began to be more widely seen. Despite her reported failing eyesight and hearing, she had embarked on the start of her professional artistic career.

Karuga’s artistic expression is very personal with a unique technique that is inspired by Byzantine mosaics. Her medium of choice includes coloured paper scraps –from newspapers, glossy magazines and packaging materials – that create elevated torn and cut paper collages, mostly figurative portraits and landscapes, of rural Kenyan environments.

In the 1990s Karuga was commissioned to illustrate an edition of Nigerian writer Amos Tutuola’s groundbreaking novel The PalmWine Drinkard. This helped her work to travel and her international breakthrough came in the US in 1992 with a group exhibition at the

Studio Museum in Harlem, New York called Contemporary African Artists: Changing Tradition. The show featured 75 artworks from nine top artists of African origin, such as El Anatsui, Bruce Onobrakpeya, Ablade Glover and Tapfuma Gutsa. Karuga was the only female artist on the show.

In 2006, she received a lifetime achievement award from the African Voice newspaper, becoming the first East African woman to do so. This is an accolade presented to Africans for their achievements and contributions to Irish society. Karuga had been visiting family there and it became medically unsafe for her to travel. She would live out her final years in Ireland.

In 2017 she was given her due at home when she was featured as the first artist of the month in a new program at the National Museums of Kenya. Her work today forms part of their collection as well as the collections of the Kenya National Archives, Murumbi Trust’s African Heritage, the Watatu Foundation, Red Hill Art Gallery and many private collections.

REF: Anne Mwiti “The Importance of Remembering Kenyan Artist Rosemary Karuga.” The Conversation, 16 July 2023, theconversation.com/the-importance-ofremembering-kenyan-artist-rosemarykaruga-155777.

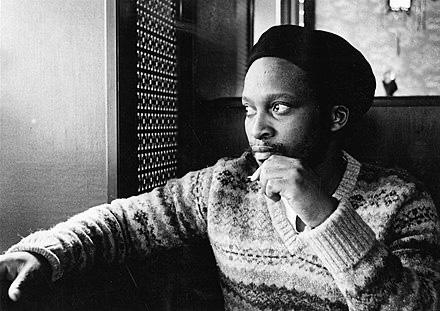

In work that was fundamentally grounded in abstraction, the artist employed symbols to express his connections to spirituality, his personal experience, his vision of identity and what it means to be African. Both as an islander – born on 17 April 1946 on the island of Gorée, Senegal, where he was exposed to artistic practices from a young age – and as a proud member of the Mandinka ethnic group, Keita’s character was infused with a deep sense of selfknowledge.

Souleymane Keita is regarded as a pioneer of contemporary artistic creation in Senegal. At the Dakar National Fine Arts Academy, where he enrolled at age 13, he studied under the painter Iba Ndiaye (1928-2008). In 1969 he organized his first solo exhibition.

Two years later, he showed his work in Nouakchott, Mauritania and proceeded from there to travel the world. He and his work were welcomed for exhibitions at galleries across Africa, the United States, Japan, Mexico, France, and Canada over a period of nearly twenty years (1972–1991).

Keita taught ceramic and painting at Jamaica Arts Center in New York. His paintings drew momentum from jazz, of which he was a passionate fan. With his pictorial approach and interrogation of the material, he stayed true to an abstract art that remained consequential across a range of media.

He dreamed of creating a cultural space around 50 kilometers from Dakar where he

would reassemble his artwork that had been exhibited in galleries around the world.

“The time has come to establish a cultural space between four walls. I have so many works of art at galleries in France and the United States. I want to repatriate them. That’s what I’m working on.”

He had his own perspective on the Biennale of Contemporary African Art in Dakar (Dak’Art), reminding people of Senegalese artists’ desire to see their capital become a global hub for the art market. Souleymane Keita also cautioned of the risk that the event would be “co-opted by outsiders.”

In his view, it was “urgent to build a contemporary art museum in Dakar,” providing infrastructure for exhibiting the work of artists such as Iba Ndiaye, Ousmane Faye, and Seydou Barry; publishing artists’ monographs; reestablishing the Academy of Fine Arts; and fostering artistic patronage.

REF: “A Brilliant Creative Spirit Leaves His Mark.” Contemporary And, contemporaryand.com/magazines/ souleymane-keita-a-brilliant-creative-spiritleaves-his-mark/. Accessed 23 Aug. 2023.

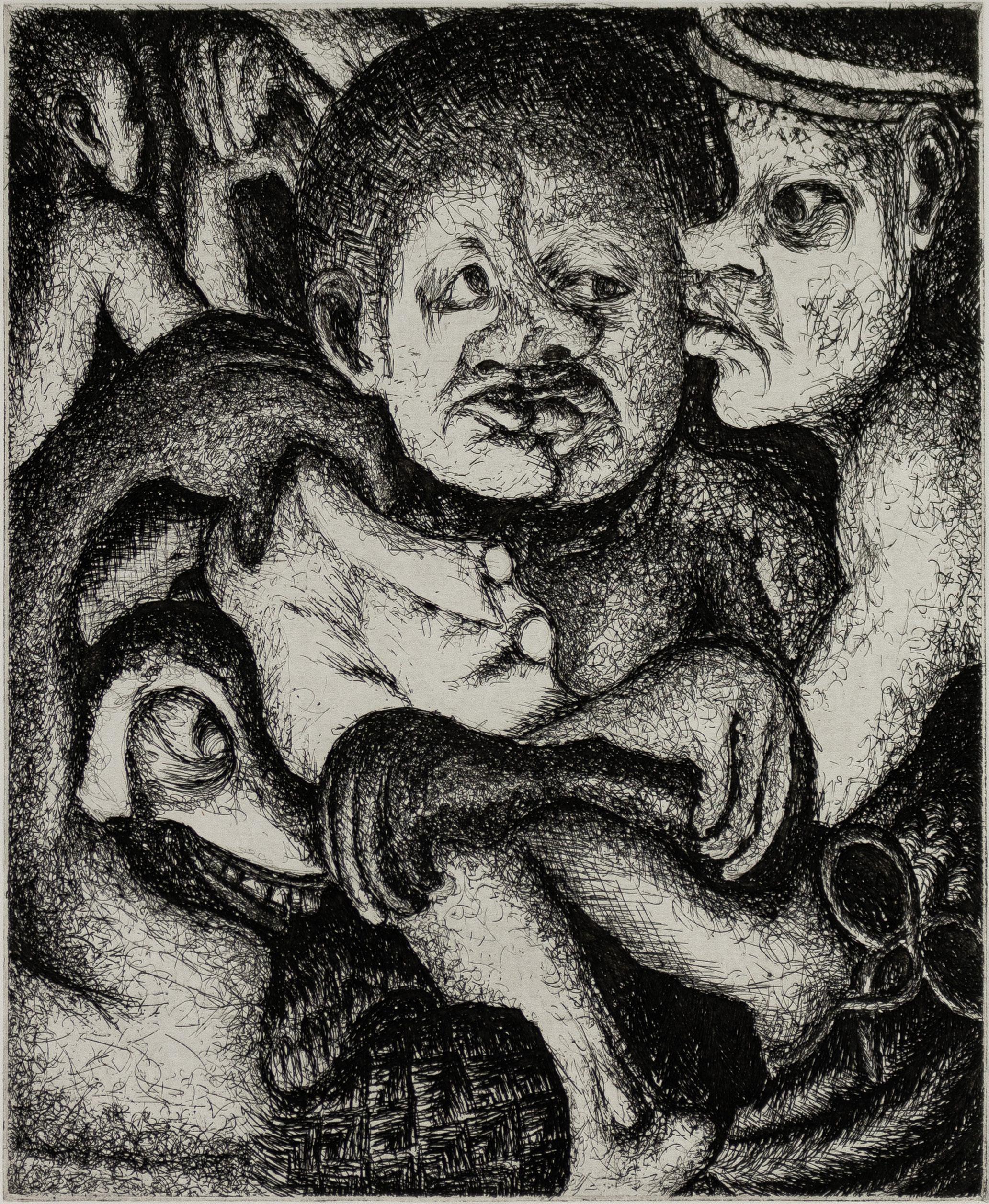

Maqhubela was born in Durban, South Africa, in 1939. His parents moved to Johannesburg in 1949, while he and his sisters were sent to live with their aunt in the rural town of Matatiele in the country’s Eastern Cape province, until they joined their parents three years later.

Maqhubela was a member of artist and teacher Durant Sihlali’s weekend artists group from 1955 to 1957. From 1957 to 1959, while still at school in Soweto, he studied under the direction of Cecil Skotnes – known for his painted and incised wooden panels, woodblock prints, tapestries and sculpture – and sculptor Sydney Kumalo at the Polly Street Art Centre. The centre was housed in a hall in Johannesburg and focused on black art students. It exhibited artists of all races, defying the racial segregation of the white minority government’s apartheid policy that saw black citizens moved into townships outside of cities.

Maqhubela started work as a commercial artist but from 1960 he was commissioned to create paintings and mosaics in hospitals, schools, halls and bar lounges in and around Soweto township. Skotnes facilitated a commission to create four large-scale oil paintings for public buildings

Maqhubela was successful, but the obstacles he and his family faced in apartheid South Africa proved too great for them. They moved to the Spanish island of Ibiza in 1973 and settled in London in 1978.

He studied at Goldsmiths College (198485) and the Slade School of Art (1985-88). At the Slade, Maqhubela was exposed to printmaking and in 1986 he produced a series of etchings that count among the most significant in his oeuvre. He continued to exhibit extensively in South Africa, in group as well as solo shows and featured

prominently in Esmé Berman’s book, The Story of South African Painting (1975).

In 1998, Maqhubela’s gouache on paper, Tyilo-Tyilo (1997), was purchased by the Smithsonian National Museum of African Art, in the USA. The painting celebrates the music of the 1960s from the South African townships. The year before, the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, UK, acquired an untitled Maqhubela oil painting with etching on paper. It depicts etched figures, lines and shapes with a dreamy, child-like quality, yet the careful composition reveals the hand of a master draughtsman.

Maqhubela is represented in all the major public collections in South Africa. The exhibition A Vigil of Departure – Louis Khehla Maqhubela, a retrospective 19602010 first opened at the Standard Bank Gallery, Johannesburg in 2010 and travelled to the Iziko South African National Gallery in Cape Town and the Durban Art Gallery.

REF: Marilyn Martin, Honorary Research Associate at Michaelis School of Fine Art. “Remembering Louis Maqhubela, Pioneering and Enigmatic South African Painter.” The Conversation, 13 Sept. 2022, theconversation.com/remembering-louismaqhubela-pioneering-and-enigmatic-southafrican-painter-174897.

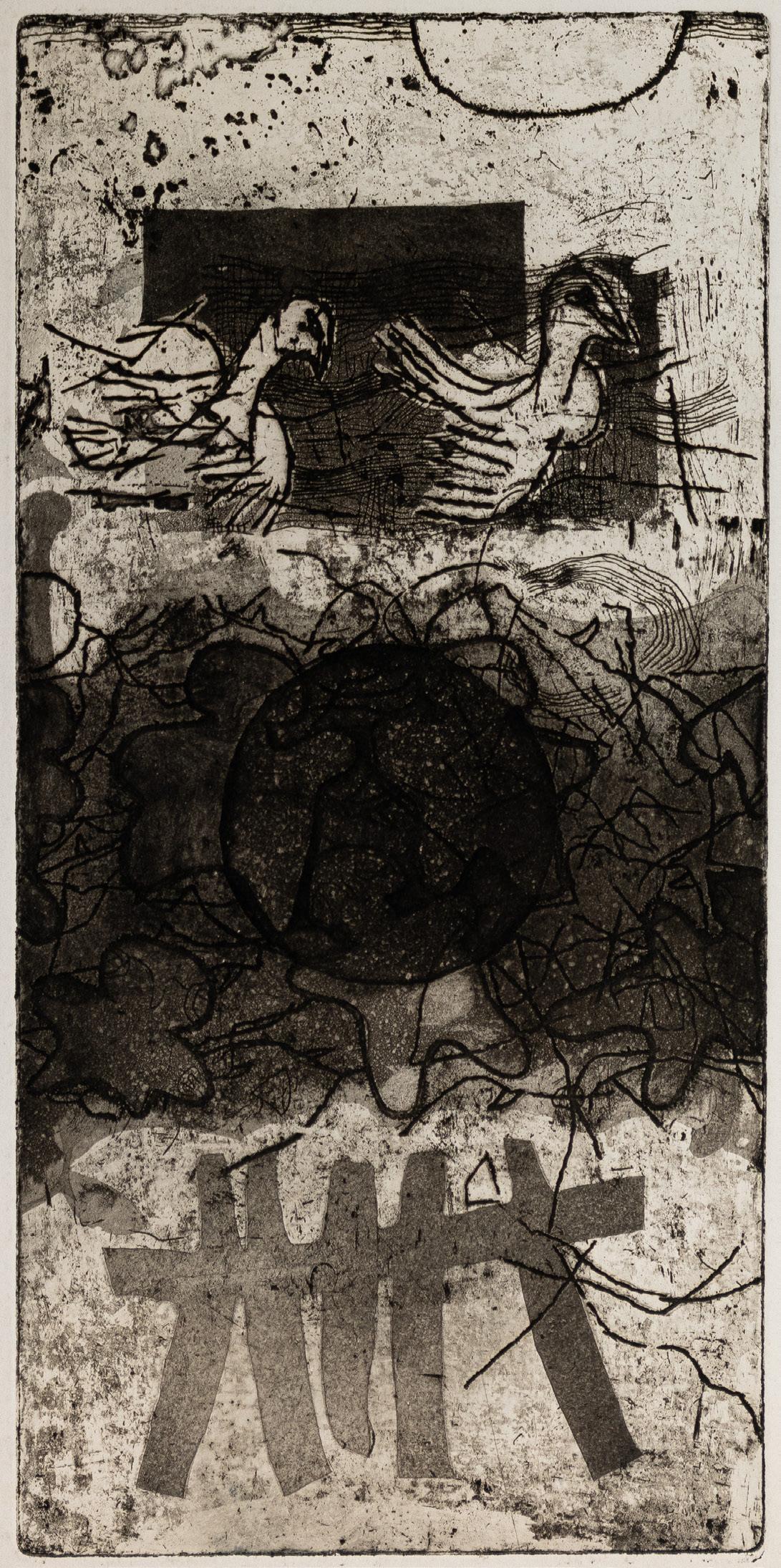

Untitled, 1986

etching

6 x 6 inches (image)

17-3/4 x 12-1/2 inches (sheet)

signed, dated, and numbered 6/30-II

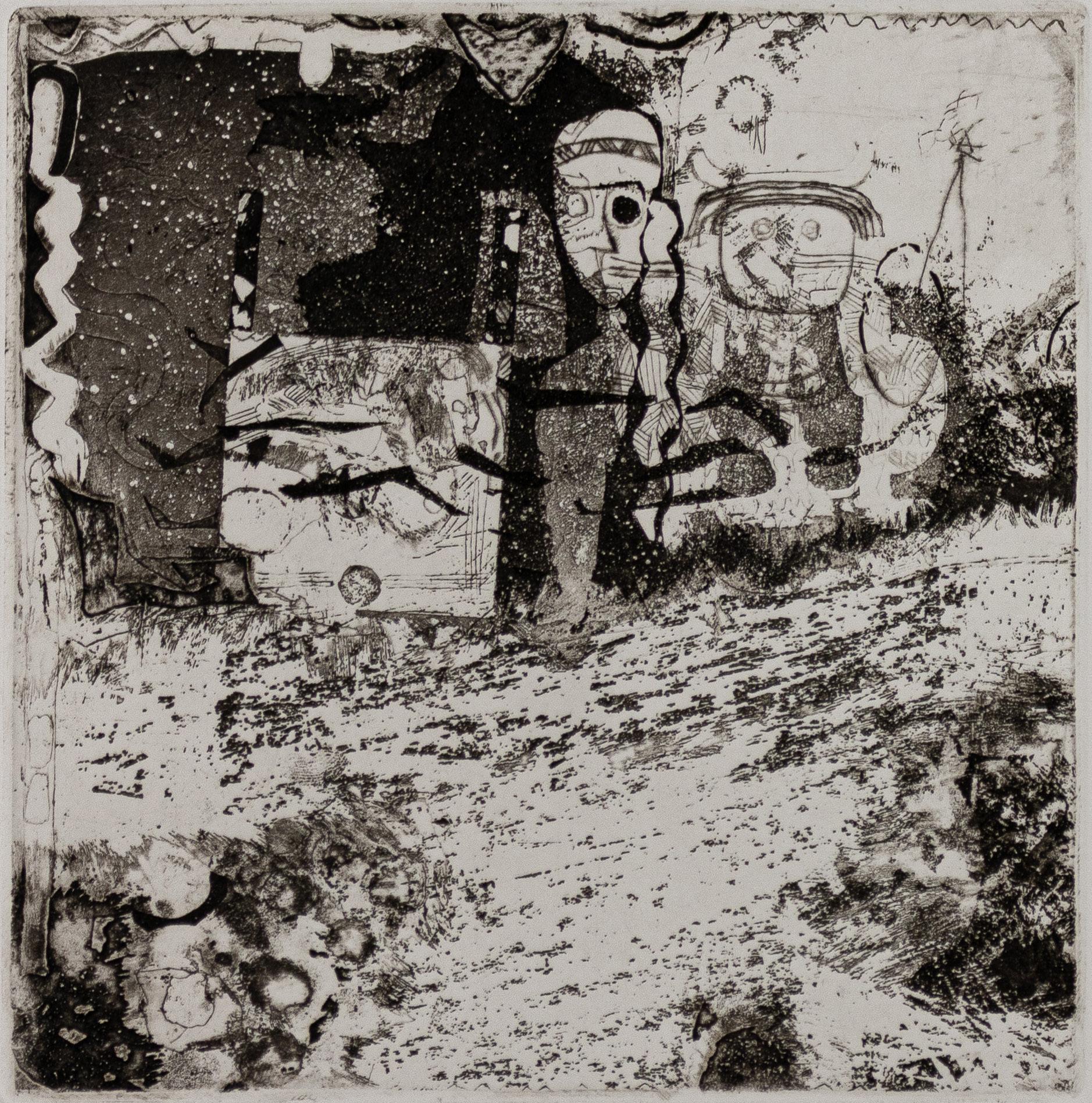

Island, 1986

etching

11-1/2 x 11-1/2 inches. (image)

23 x 19 inches (sheet)

signed, titled, dated and numbered 7/25

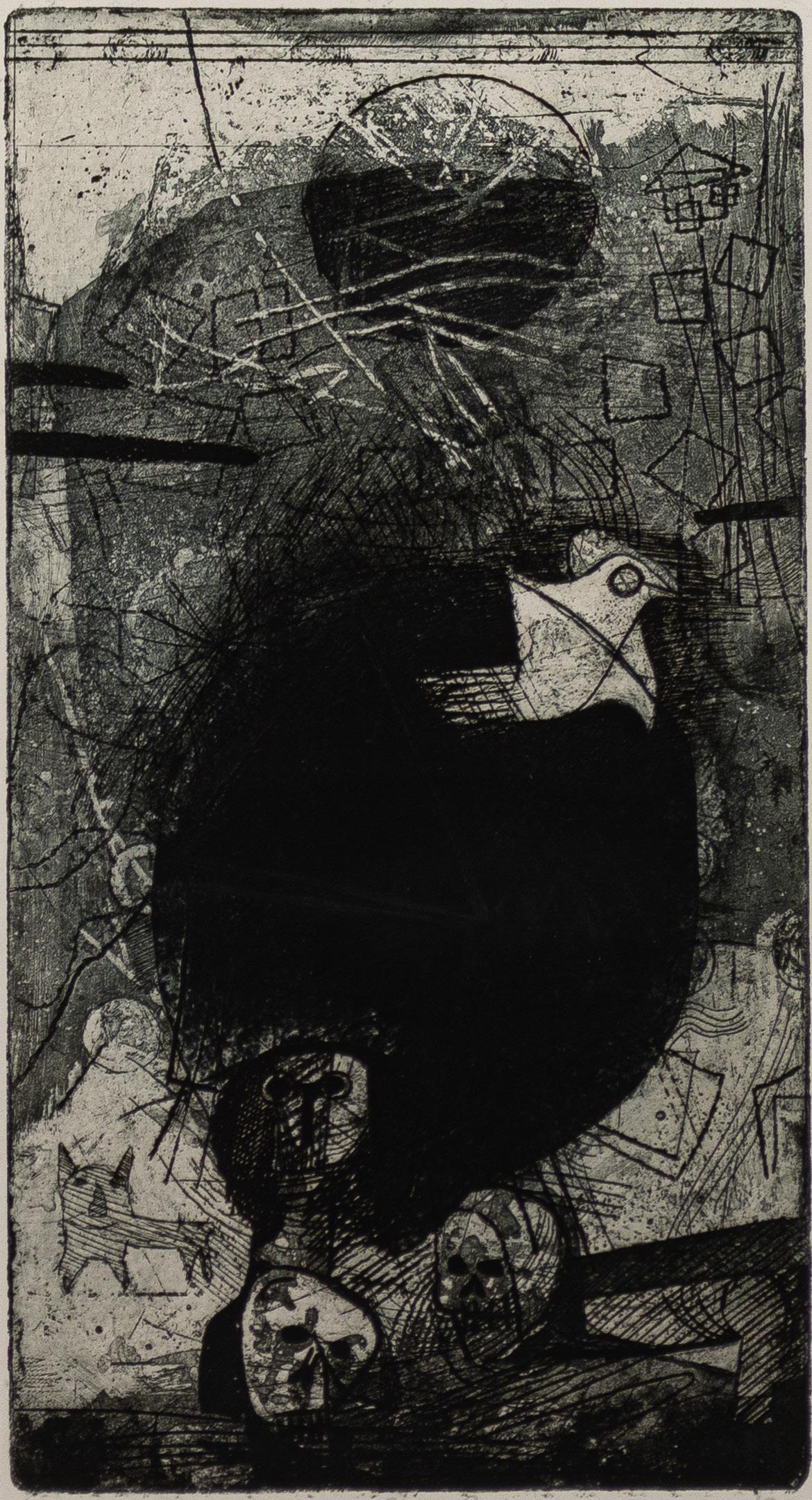

Tension, 1987

etching

12 x 6 inches (image)

22-1/2 x 15 inches (sheet)

signed, titled, dated, and numbered 1/25

Exit-Entry, 1987

etching on paper

11-1/2 x 6 inches (image)

signed, dated, titled and numbered 1/25

Stan-Eclipse, 1983 oil on paper 22-1/2 x 30 inches signed, titled, and dated

Untitled, 1985 etching 11-1/2 x 11-1/2 inches (image) signed and dated

Untitled, 1986 etching on paper

12 x 6 inches (image)

17-3/4 x 11-1/2 inches (sheet)

signed, dated and numbered, 5/25

Where to Go, 1991

etching

10 x 8-1/4 inches (image)

26 x 19-1/2 inches (sheet)

signed, titled, dated, and numbered 22/45

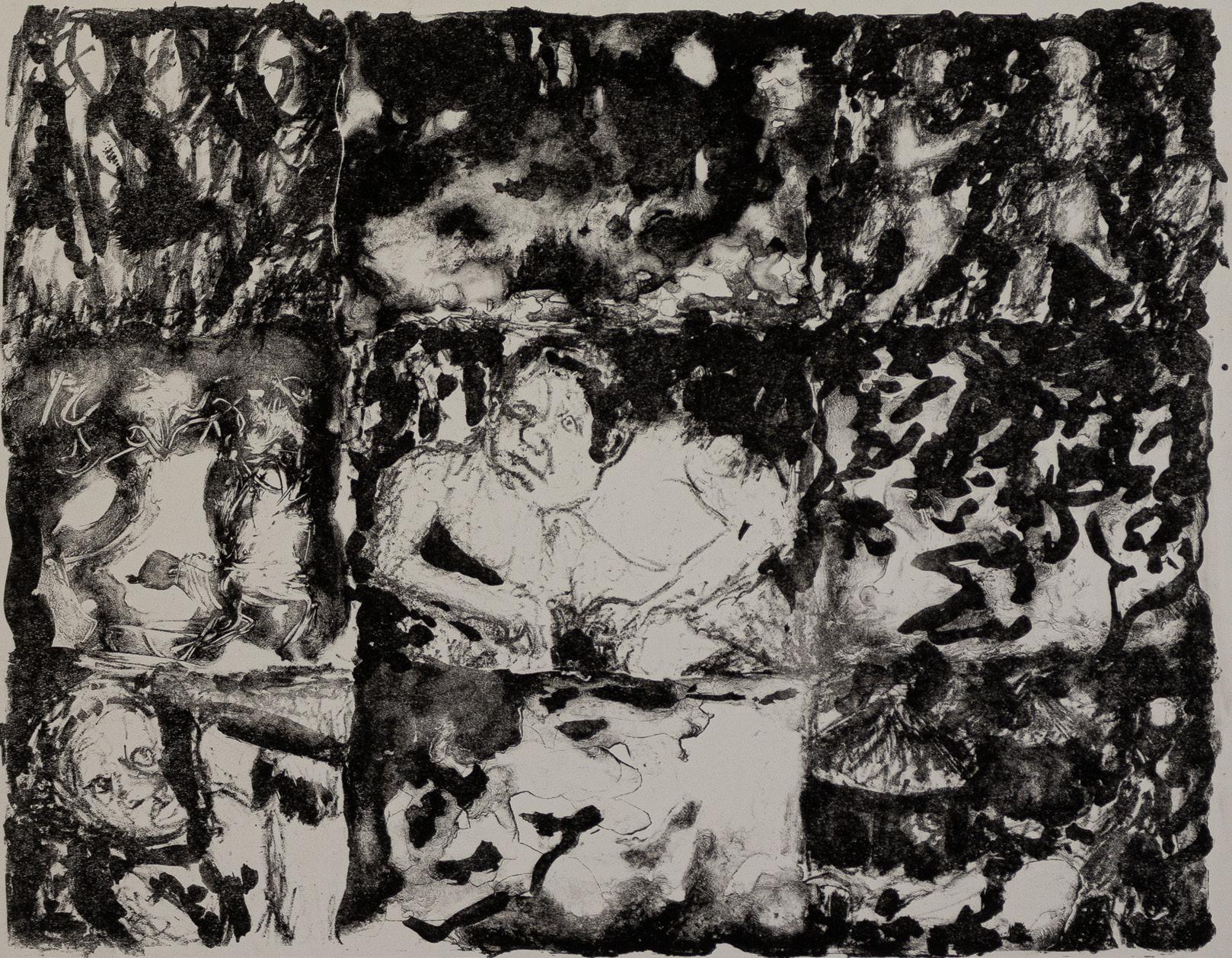

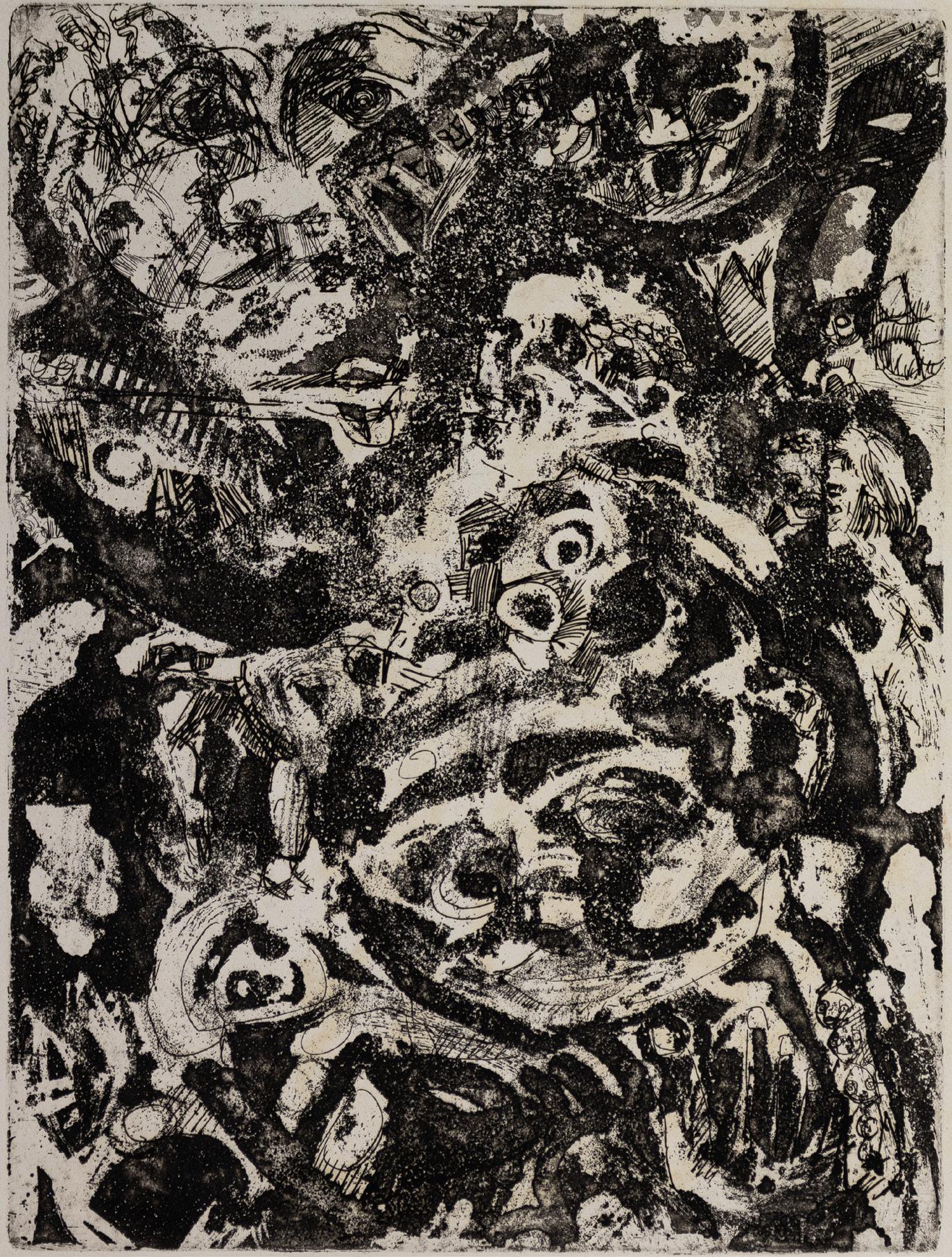

Mmapula Mmakgoba Helen Sebidi was born in Marapyane, near Hammanskraal, in 1943. She developed a life-long love for the designs of traditional arts and crafts when as a young girl she accompanied her grandmother who was a traditional wall and floor painter.

While Sebedi was earning a living as a domestic worker in Johannesburg, she pursued her own creativity as a hobby until her work was discovered by her employer. Realising that she needed to receive formal lessons in the art of painting, Sebidi enrolled at the remarkable White Studio from 1970 to 1973.

With a firm grounding in the fundamentals of painting technique and composition, Sebidi’s art made a qualitative leap. She broadened the scope of her medium and her work began to be noticed within the art world. The Johannesburg Artists under the Sun exhibitions in the early 1980s represented a commercial breakthrough for her, enabling her to make a decent living from her art for the first time.

Having experienced the difficulty of pursuing art as a career, Sebidi was concerned with the development of art appreciation and art education. In 1985 she took up a teaching position at the Katlehong Art Centre near Germiston. Between 1986 and 1988 she worked for the Johannesburg Art Foundation while teaching at the Alexandra Art Centre. She also participated in numerous art projects with community organisations such as the Funda Art Centre, and the Thupelo Art Workshop.

Sebidi draws her inspiration for her work on the happenings and experiences of daily township life. The suffering and disruption inflicted by apartheid, especially on women, are common themes, often executed with complementary techniques.

Sebidi was awarded a Fulbright Scholarship to travel to the USA and exhibit at the Worldwide Economic Contemporary Artists’ Fund Exhibition. In 1989 she was awarded the Standard Bank Young Artist Award. Helen Sebidi, as she is known professionally, has become a recognized artist in South Africa and internationally. Her work is exhibited regularly in major galleries across the country and abroad, and routinely included in standard reference books on South African art.

REF: Mapula Helen Sebidi (1943 - ), www. thepresidency.gov.za/national-orders/ recipient/mapula-helen-sebidi-1943. Accessed 23 Aug. 2023.

signed, titled, and numbered 6/30

Like A Dream, 1991

etching 10 x 8 inches (image)

26 x 20 inches (sheet)

signed, titled, dated, and numbered 22/45

Far In Between, 1992

etching 9-3/4 x 8-1/2 inches

26 x 19-3/4 inches

signed, titled, dated, and numbered 22/45

Second Conference of Negro Writers and Artists, 1959; color lithograph, 23-7/8 x 16-1/2 inches, signed.

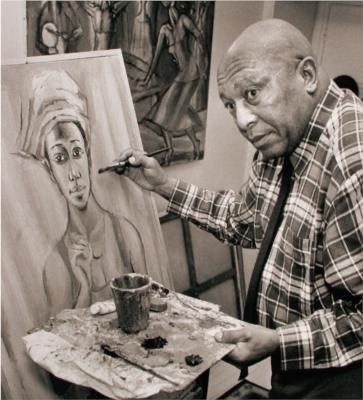

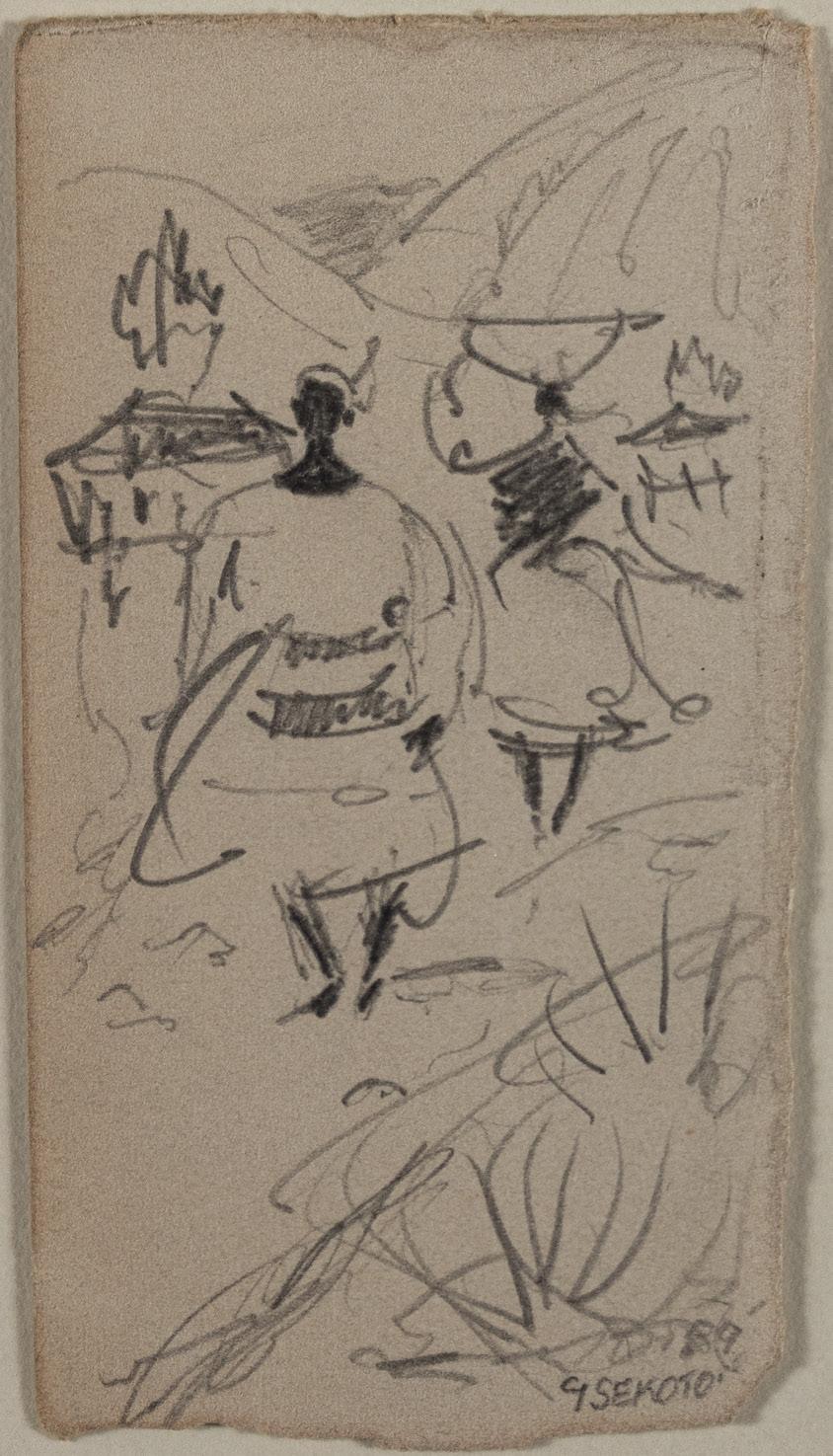

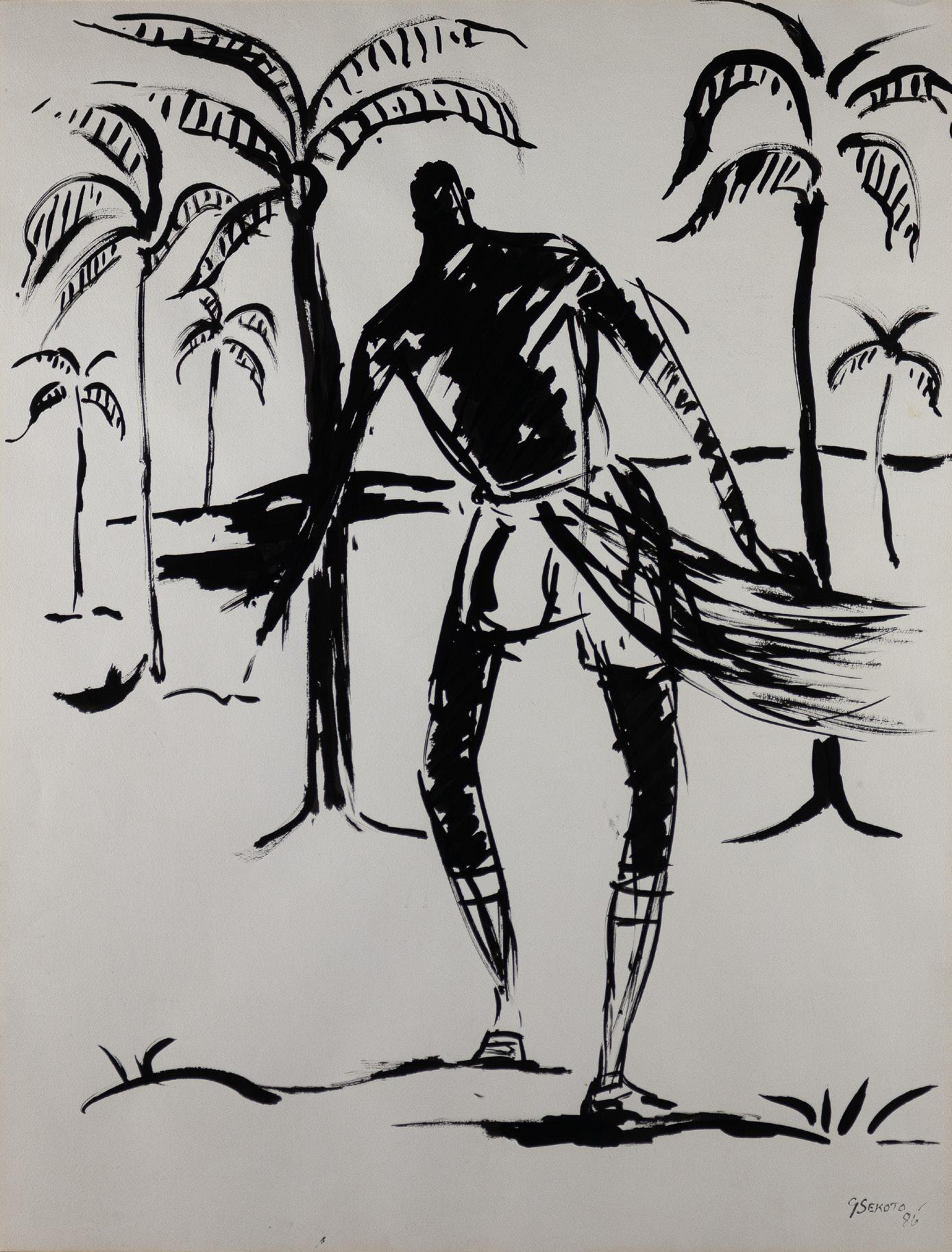

Gerard Sekoto’s rural upbringing in the Lutheran Mission Station in Botshabelo and periods of residence in Johannesburg, Cape Town and Pretoria nourished his perspective on the South African people, primarily the impoverished black population.

He had trained as a school teacher but decided, as a self-taught artist, to launch his professional art career in 1938. He left the rural areas of northern South Africa to travel to Johannesburg where free association between different races was still possible. Here he was introduced to the liberal artistic White community and amongst others, met an artist, Judith Gluckman, who offered to teach him how to paint with oils. He quickly assimilated these techniques and was soon recognised as a notable artist in Johannesburg art circles. He wished to familiarise himself with the country and in 1942, having sold enough paintings to pay his way, travelled to Cape Town to live in District 6 and then to Eastwood, Pretoria in 1945. Apartheid policies, legislated from 1948, resulted in the destruction of Sophiatown, District 6 and Eastwood in the 1950s. Sekoto’s paintings remain as vivid historical records of these vibrant urban environments and the people who lived there.

In 1947 Sekoto left South Africa in voluntary exile for Paris, planning to expose himself to what he believed would be the centre of the international art world. The artist would never

to return to the country that inspired his stirring and colourful depictions of cultural activity and racial tensions. Sekoto’s position as one of South Africa’s first and most important modernists and social realists has been reinforced by a retrospective exhibition of his work at the Johannesburg Art Gallery in 1989, an honorary doctorate from the University of Witwatersrand, the presence of his work at the South African National Gallery, record sales of his paintings at recent auctions in London and Johannesburg, and a recent mural-painting project featuring Sekoto’s work as painted by apprentices though the Gerard Sekoto Foundation.

Untitled, 1989 graphite drawing 5 x 2-3/4 inches signed and dated

In the Location, 1986

watercolor on paper 21-1/2 x 29-1/2 inches

signed and dated; titled verso exhibition label verso

watercolor

17-1/4 x 12-1/4 inches signed and dated; titled verso

So-We-To, 1979 etching 8 x 9-3/4 inches signed, titled, dated, and numbered 6/140

The biography of this artist has eluded us after considerable research. We do know he was one of the artists represented by Helen Jackson in the exhibition, Voices From Exile: South African Exhibit Project (1986). It seems that he worked in Soweto, a southern township in the city of Johannesburg. Louis Maqhubela also worked there in the 1960s, so it is likely they crossed paths decades before “reuniting” in the Voices from Exile show.

Gathered, 1979 etching on paper

13-1/4 x 10 inches (image)

22-1/4 x 14-1/2 inches (sheet)

signed, dated, titled and numbered 1/50

Mother and Young Warriors, 1984 serigraph on parchment

29 x 20 inches (image)

36-1/2 x 24 inches (sheet)

signed, titled, and dated First Proof, edition to be 70 prints

The Southern Tip, 1984 etching

11-1/2 x 10 inches (image)

16 x 10 inches (sheet)

signed, titled, dated, and inscribed, Jan Van Who AP

Moratorium, 1985

1985

conte crayon/charcoal on paper

22 x 30 inches (image)

signed on verso in pencil with an alternate title: Youth of Unity identified and dated on labels verso

Lefifi Tladi is a South African painter, poet, sculptor and musician. As a member of the black consciousness movement he was exiled from South Africa in 1976. He lived in exile, primarily in Stockholm, Sweden, until the abolition of apartheid, and in 1997 returned to South Africa for the first time in over 20 years. In 2021 he was awarded the lifetime achievement award by the South African Literary Awards.

He was born in 1949 in the township of Lady Selborne, Pretoria, South Africa. His involvement in the cultural world started in 1966 when he co-founded a youth club known as De-Olympia in the township of GaRankuwa, north-west of Pretoria. The club hosted workshops, recited poetry, dance and music. The group subsequently formed a jazz band, Malombo Jazz Messengers, later renamed Dashiki. During the 1970s Lefifi started to get more involved in the Black Consciousness Movement via its cultural events where he performed with Dashiki. Dashiki also became regulars at the United States Embassy’s jazz appreciation sessions under the management of Geoff Matlherane Mphakathi.

In 1971, De-Olympia was transformed into an art studio, gallery and museum of contemporary Black art. The aim was to exhibit art, stimulate research, and encourage the documentation of African arts. Among others, Lefifi worked with Motlhabane Mashiangwako, Victor Mkhumbuza, Fikile Magadlela, and Harry Moyaga. They also organized numerous Black art exhibitions and workshops at some of the major Black universities and schools. This was in response to the “Bantu Educations” discouragement of Black people’s creativity. After being active for three years the apartheid authorities forced the museum to close down in 1974.

In 1976 Lefifi was arrested and detained by the security police for participating in the

Soweto uprising. He was kept in solitary confinement for over two months before he was released on bail. When he was out on bail he decided to not stay in South Africa due to the severity of the charges he was facing and fled across the border to Botswana. While in Botswana he and fellow artists established the Tuka Cultural Unit, a cultural formation meant for organizing group exhibitions as well as sustaining working relations with artists in South Africa. In 1977, they took part in the month-long event, Festac ’77 – the pan-African international festival of arts and culture in Lagos, Nigeria.

Lefifi got in contact with a Swedish diplomat while holding an exhibition at the Botswana National Museum in 1980. This encounter led to Lefifi receiving a scholarship to study fine arts and art history at the Gerlesborg School of Fine Art in Stockholm. He moved to Stockholm the following year.

While in Sweden Lefifi continued to be active in anti apartheid movement. He participated in the exhibition Art Against Apartheid in Amsterdam, Holland and the SIDAsponsored End White Rule in Black South Africa exhibition.

Since 2016 he lives in Stockholm full time and continues to exhibit and host poetry and art workshops. He is passionate about education and is involved with various art education projects in South Africa from a distance.

REF: “Lefifi Tladi.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 14 Mar. 2023, en.wikipedia.org/ wiki/Lefifi_Tladi.