A Selection of Works from the Horseman Foundation

Black Art Auction is pleased to present a selection of deaccessioned works by African American artists from the Horseman Foundation, offered by private sale and auction.

Since its inception in 2012, the Foundation has championed artists working outside the narrow parameters of the art historical canon due to their race, gender, or geographic locale. Through its Art Answers initiative, the Foundation facilitates access to, lends, and donates works of art, organizes and sponsors exhibitions and programming, and provides financial support for artists and scholars seeking to expand the dialogue of 20th and 21st-century American art.

The idea of deaccessioning by an institution (or collector) might sometimes be perceived in a negative light. Usually, complex internal reasons drive the process. In this case, it is just that: repetition within an artist’s body of work, very similar subjects, space and theme issues, etc. The simple, good news is that this makes for a fantastic opportunity to acquire these works that would otherwise never be available. The paintings and sculptures are primarily from the second half of the 20th century and would be worthwhile additions to a museum or significant private collection.

If you have interest or questions, please contact me directly at thom@blackartauction.com or my cell (314)378-2165.

Ralph Chessé was born in New Orleans and was primarily self-taught as an artist, with the exception of a few months study at the Art Institute of Chicago in 1918. He traveled to Southern California in 1923 and eventually headed north to the Bay Area in the early 1930s, where he painted and worked as a professional puppeteer in children’s theater, an activity he mastered and continued throughout his life.

Chessé worked for the Public Works Art Project in 1933, contributing to the Coit Tower murals in the Telegraph Hill neighborhood of San Francisco. His fresco reflects his work in children’s theater by depicting children at play, and seems to present its characters in an almost puppetlike manner. Each child is separated in space and frozen in movement, almost as if they are posing for a picture or pretending to play. Its design was inspired by the work of early American primitive limners, who traveled the land in the years before the spread of photography. They brought along with them canvases pre-painted with bodies––headless bodies waiting for individual face portraits to be added. Chessé linked his physically isolated children by way of a gravel path that guides the eye downward from left to right through the mural and past each child at play. He continued this approach to figure painting throughout his career.

Moses and the Idolators and Canaan both

illustrate this concept. Although there is a narrative to each work, the image appears as a “still”, thus allowing the viewer to contemplate the scene at a desired pace. The character development is static, so betrayal is impossible, and the scene becomes symbolic, instead of a fleeting image that may have been spied out of context.

Chessé explored many styles of Modernist painting, and was strongly motivated by color. In the 1940’s, Chessé painted AfricanAmerican figures, many of them dock workers, in social-realist scenes recalling his boyhood in New Orleans. He also used religious themed motifs derived from The Bible. During World War II, he created paintings of the shipyards in the Bay Area. Later, Chessé moved to Oregon where he painted in a more abstract, but still figurative style, until his death at the age of 90.

He exhibited his paintings at the Gildea Gallery and the Lucien Labaudt Gallery in San Francisco, the Duncan Gallery in New York, and the Marc Antony Gallery in New Orleans. He was a member of the San Francisco Art Association and the Oakland Art Association. His work was included in group exhibitions at the Oakland Art Gallery (now the Oakland Museum of California) and the de Young Museum. A solo exhibition of his work was mounted at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

Strong Bearing the Infirmities of the Weak, 1995 mixed media on canvas 45-1/2 x 59 inches signed, dated, titled Provenance: the collection of the artist

Kevin Cole’s iconographic symbolism balances the aesthetic and political content of his work against the backdrop of African and Asian origins, as well as an uniquely American history. Although the symbolic use of the necktie in Cole’s work has regal and international references, its symbolic use of tied necks within the African American experience is referenced in Billie Holiday’s song, Strange Fruit. Nationwide lynchings exemplified the worst aspect of the human condition and the social and economic contempt for Black American men, women, and families. Working in a range of mediums, use of repetitive form, and color create three dimensional structures that invite those who experience his work to reflect upon abstracted references to a necktie used for status, beauty, fashion and the destruction of human life. Cole’s work celebrates history, survival, and a personal memory of a time and place.

---Halima TahaKevin Cole studied at University of Arkansas Pine Bluff (BS), University of Illinois (MA) and Northern Illinois University (MFA). His work has been included in numerous significant exhibitions, including at the Dallas African American Art Museum, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Corcoran Gallery of Art, and the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art.

In 2020, Cole received the Brenda and Larry Thompson Award from the Georgia Museum of Art at the University of Georgia. This award is given to an African American Artist who has made significant but often lesser-known contributions to the visual arts tradition and has roots or major connections to Georgia.

Cole’s work is prominently featured at the National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Cousins was born and raised in Washington, D.C. and attended Howard University. He studied art at the Art Students League in NYC, but left for Paris in 1949, to work with Ossip Zadkine. His first major exhibit of metal sculptures took place in 1954 at the Galerie Raymond Cruze (Paris). He wanted to combine metal plates and lines, calling it "plaiton". This was a combination of the French word, "Laiton" (brass) and "Plate". Rosins explained the concept "involves giving special attention to the form of the empty space between the solid elements of a sculpture, as well as to the empty space surrounding the sculpture."

Darthea Speyer (an American gallerist in Paris associated also with Beauford Delaney) was supportive of Cousins and gave him exhibits at Galerie Speyer. Cousins left Paris for Belgium in 1967.

REF: Explorations in the City of Light: African-American Artists in Paris, 1945-1965, Studio Museum of Harlem (1996).

Untitled, 1969 iron with black patina 12-1/2 x 7 x 5 inches signed and dated

Provenance: private collection, Belgium

Cropper was born in New York, and both of his West Indian parents worked in Harlem. He studied at the Art Students League. Prior to that he was briefly, informally taught by Beauford Delaney (1947). In the mid-1950s, Cropper exchanged music/art lessons with Charlie Parker.

Cropper moved to Stockholm, Sweden, in the early 1960s and the next year exhibited in 10 American Negro Artists Living and Working in Europe at Den Frie Udstilling in Copenhagen. This was an important exhibition for African American artists who had left the U.S. for greater freedom and artistic equality; among the ten were Beauford Delaney, Herb Gentry, Sam Middleton, Larry Potter, Walter Williams, and Norma Morgan. Much of his work centered around his beliefs in Japanese tradition and Zen.

Emilio Antonio Cruz was an African American of Cuban descent born in the Bronx. He studied at the Art Students League and The New School in New York, and finally at the Seong Moy School of Painting and Graphic Arts in Provincetown, Massachusetts. As a young artist in the 1960s, Cruz was connected with other artists who were applying abstract expressionism concepts to figurative art such as Lester Johnson, Bob Thompson and Jan Muller. He combined human and animal figures with imagery from archaeology and natural history to create disturbing, dreamlike paintings.

Harry Rand, curator of 20th Century Painting and Sculpture at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, described Emilio Cruz as one of the important pioneers of American Modernism of the 1960s for his fusion of Abstract Expressionism with figuration. Cruz received a John Jay Whitney Fellowship as well as awards from the Joan Mitchell Foundation and from the National Endowment for the Arts.

Cruz moved to Chicago and taught at the Art Institute of Chicago during the 1970’s where he exhibited widely and was represented by the Walter Kelly Gallery. He wrote two plays, Homeostasis: Once More the Scorpion and The Absence Held Fast

to Its Presence. These were first performed at the Open Eye Theater in New York in 1981, and were later included in the World Theater Festival in Nancy and Paris, France, and in Italy. In 1982 he returned to New York where he began to exhibit again. In the late 1980s he resumed teaching at the Pratt Institute and at New York University.

Cruz’s work has been featured in exhibitions at the Zabriskie Gallery, New York; Anita Shapolsky Gallery, NY; Walter Kelly Gallery, Chicago; Studio Museum in Harlem; and the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. In 1994, Cruz’s work was shown as part of the American contingent at the IV Biennial Internacional de Pintura en Cuenca, Ecuador. His last show, I Am Food I Eat the Eater of Food, was held at the Alitash Kebede Gallery in Los Angeles in 2004.

His work is held in many collections including the Museum of Modern Art, the Brooklyn Museum, the Studio Museum in Harlem, the Smithsonian American Art Museum and National Museum of African American History and Culture, the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, D.C., the Albright–Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York, and the Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford, Connecticut.

Untitled,

Exhibited:

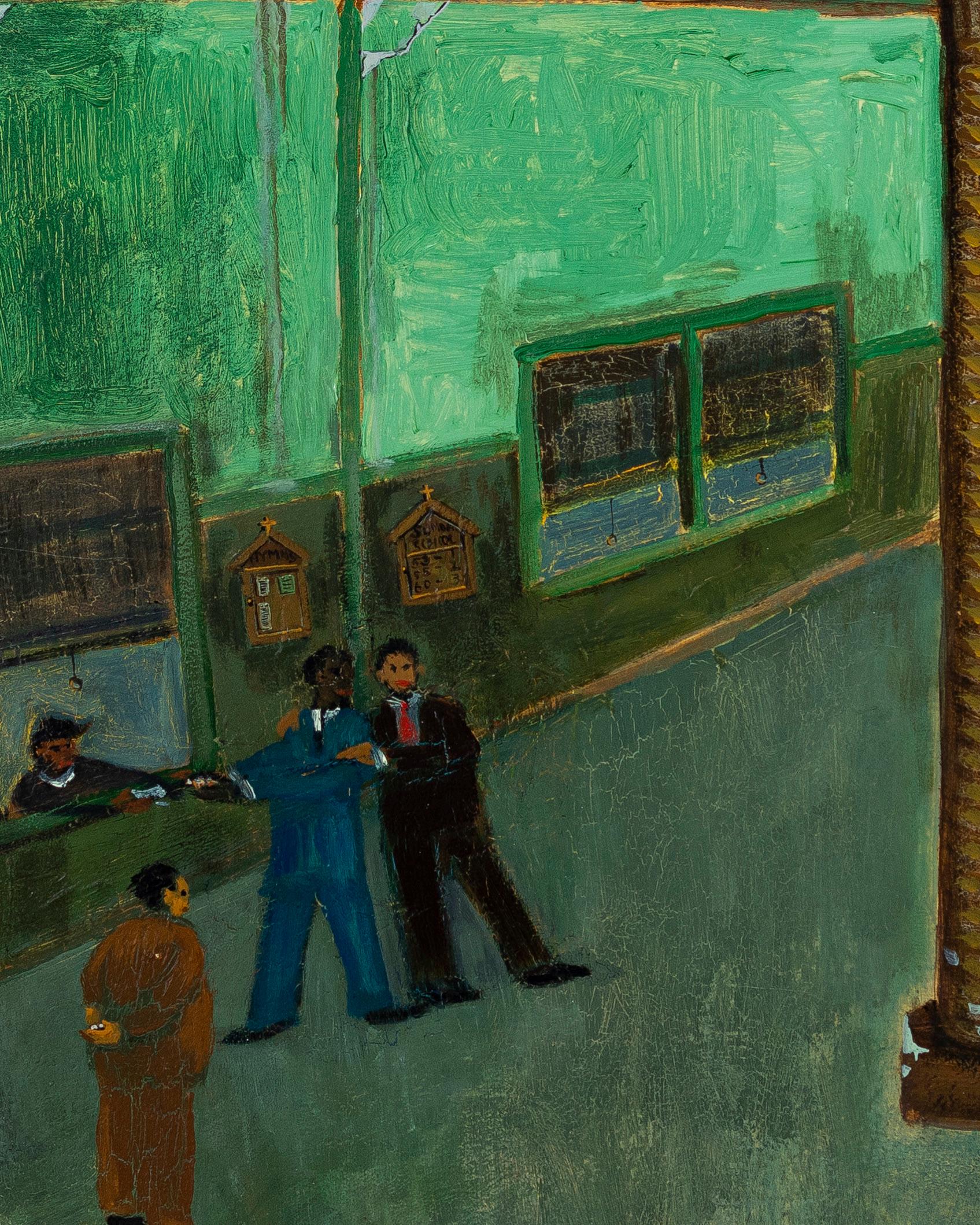

Ellison was born in Georgia in 1900. He developed his early love of art into a career as a painter, designer and craftsman. He was best known for his works depicting the shared experiences of African Americans who were a part of the Great Migration north, a movement that he had experienced for himself. After moving north to Chicago in the 1920s, he attended the Art Institute of Chicago. Ellison was employed by the Easel Painting Division of the Illinois Art Project/Works Progress Administration and was active in the South Side Community Art Center. His work was featured widely in exhibits featuring African-American artists, however by the early 1940’s, he seemed to have stopped actively exhibiting. Ellison died in Chicago in 1977. His work may be found in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago and the St Louis Art Museum.

With the Depression raging and black unemployment at nearly 50 percent, Policy was not only an obsession, it was also one of the leading engines of jobs and economic production in Chicago’s teeming black neighborhood known as Bronzeville. As described at length by Horace Cayton and St. Clair Drake in their captivating 1945 study of Chicago’s black citizens, Black Metropolis, there were some 500 policy stations in the neighborhood: one on almost every block and more numerous than churches. At its height in the late 1930s, Policy employed more than five thousand people, “with a weekly payroll of over $25,000, and an annual gross turnover of at least $18,000,000.”

Daniel Schulman, chicagomodern.orgSchulman is describing another work by Ellison, Old Policy Wheel, (1936). Ironically, he points to an excerpt claiming there were more policy stations than churches in Bronzeville. In the painting, Just Business, policy has actually been brought into the church. In what appears to be a makeshift neighborhood church, repurposed from an old vacant retail store, we see the pastor addressing an almost exclusively female audience, dressed for church, and packed into the front pews. The men, originally seated in the back of the congregation, and likely with the intention of the events unfolding, have abandoned their seats to buy policy tickets through an open window from a neighborhood “runner”. A second glance back to the front of the congregation reveals the pastor turning a blind eye to the proceedings in the back. Ellison foresaw this back and forth play and emphasized it. His portrayal of the physical setting coincides with the nature of the activity: the front of the congregation is swathed in light and nicely appointed with floral arrangements, while the rear of the building, or what is our foreground, is dark and the walls show decay. Ellison also left one pew toward the back completely empty, to act as a subtle dividing line between the two dynamics. The posture of the men in the composition reveals a measure of insecurity and guilt, but not so much that they wouldn’t stand in plain sight and do it. Ellison’s paintings consistently convey the message that the lapse of judgement and/or morality is enacted in plain sight.

Just Business, c. 1940 oil on paperboard 18 x 24 inches signed; titled and dated verso on artist label

Text reference:

Koehnline Museum of Art. Convergence: Jewish and African American Artists in Depression-era Chicago. Des Plaines, IL: Oakton Community College, 2008.

Schulman, Daniel. “Walter Ellison.” In Chicago Modern, 1893–1945: Pursuit of the New, edited by Elizabeth Kennedy, p. 109. Chicago: Terra Museum of American Art, 2004.

They Seek a City: Chicago and the Art of Migration, 1910-1950 (Art Institute of Chicago, catalog to the exhibition), Sarah Kelly Oehler

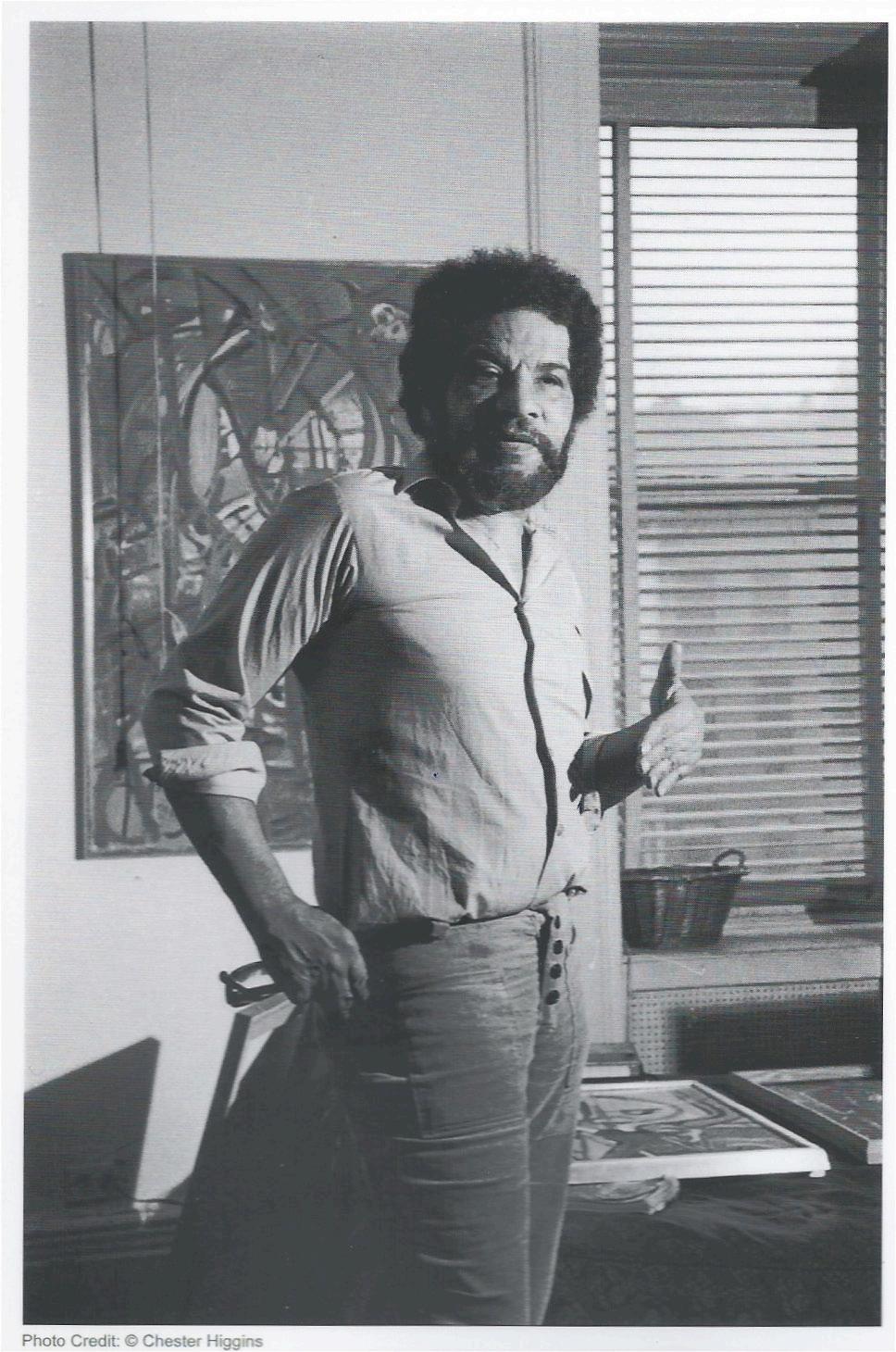

Gammon was born in Philadelphia and studied at the Philadelphia Museum School of the Industrial Arts (1941, 19461949), Tyler School of Fine Art and Temple University (1950-1951). He also served in the U.S. Navy from 1944-1946.

Gammon was a figure painter first and foremost. His early works, such as Alienation, The Scottsboro Boys, Harlem 66, Scottsboro Mothers, and Freedom Now (recently included in the exhibition Soul of a Nation, Art in the Age of Black Power) are powerful, somewhat angry images; the artist uses color sparingly to accentuate the message and lessen any decorative element. In fact, the 1965 exhibit of works by artists in the group Spiral (of which Gammon was a member), was titled, First Group Showing: Works in Black and White (1965).

Gammon exhibited at Brooklyn College (1968); Minneapolis Institute of Art (1968); Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (1970); Studio Museum in Harlem; Martha Jackson Gallery; Philadelphia Civic Center; Flint Institute of Art; Rhode Island School of Art; Everson Museum of Art; San Francisco Museum of Art; and the Atlanta University Annuals, among other venues.

Alienation, 1965 acrylic on canvas 42 x 32 inches signed, dated, titled Provenance: the estate of the artist

Gammon was a member of the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition, established by Benny Andrews and Cliff Joseph, and participated in the protest exhibition at Acts of Art Gallery, Rebuttal to the Whitney (1971). Acts of Art Gallery held a solo exhibition of his work in 1974.

Additional reading: African American Art and Artists, Samella Lewis; AfricanAmerican Art, Sharon F. Patton.

In the foreword to the Spiral exhibition catalog of 1965, it states:

It will be apparent that the works do reflect varying feelings and approaches to art: several reveal that the artist’s eyes were fed by nature; another, the painter’s basically emotional response; works of Reginald Gammon and Merton Simpson are configured with violent images of conflict; in contrast, the graphics of Bill Majors are lyrical and richly textured; Hale Woodruff’s painting, despite a surface freedom, has deliberate exactitude and design.

Come In, 1969 oil on canvas 46 x 29 inches signed, dated, titled

Let experience be a part of you as a human being…Even though we’re black and we’ve been hurt by many people, we still have to give of ourselves. We sort of have to be universal. Nor do we lose blackness by being universal.

Gentry was born in Pittsburgh, but was raised in Harlem before WWII, where he had some exposure to art under the pro grams of the WPA. He served in the war, first in North Africa and then in Germany. He returned to Europe in the latter 1940s and attended the Ecoles des Beaux Arts and the Academie de la Grande in Paris. Gentry loved Paris and believed there were many similarities between Harlem and Paris—they were both “world cities”, with many languages and cultures—and all embraced enthusiastically.

Gentry was more drawn to the European Cobra Group of painters, who practiced a bold, gestural, figurative form of expres sionism, over the abstract expressionists who were gathering great popularity in the United States in the mid-20th century. Eventually, he took up residence in Swe den, and divided his time between there and the U.S.

Untitled, c. 1975 rhoplex acrylic emulsion suspended on string gridwork 50-1/2 x 50 inches signed Provenance: the collection of the artist.

Illustrated: Feels Like Freedom, Phillip J. Hampton (1922-2016), Telfair Museums, 2022, p. 137.

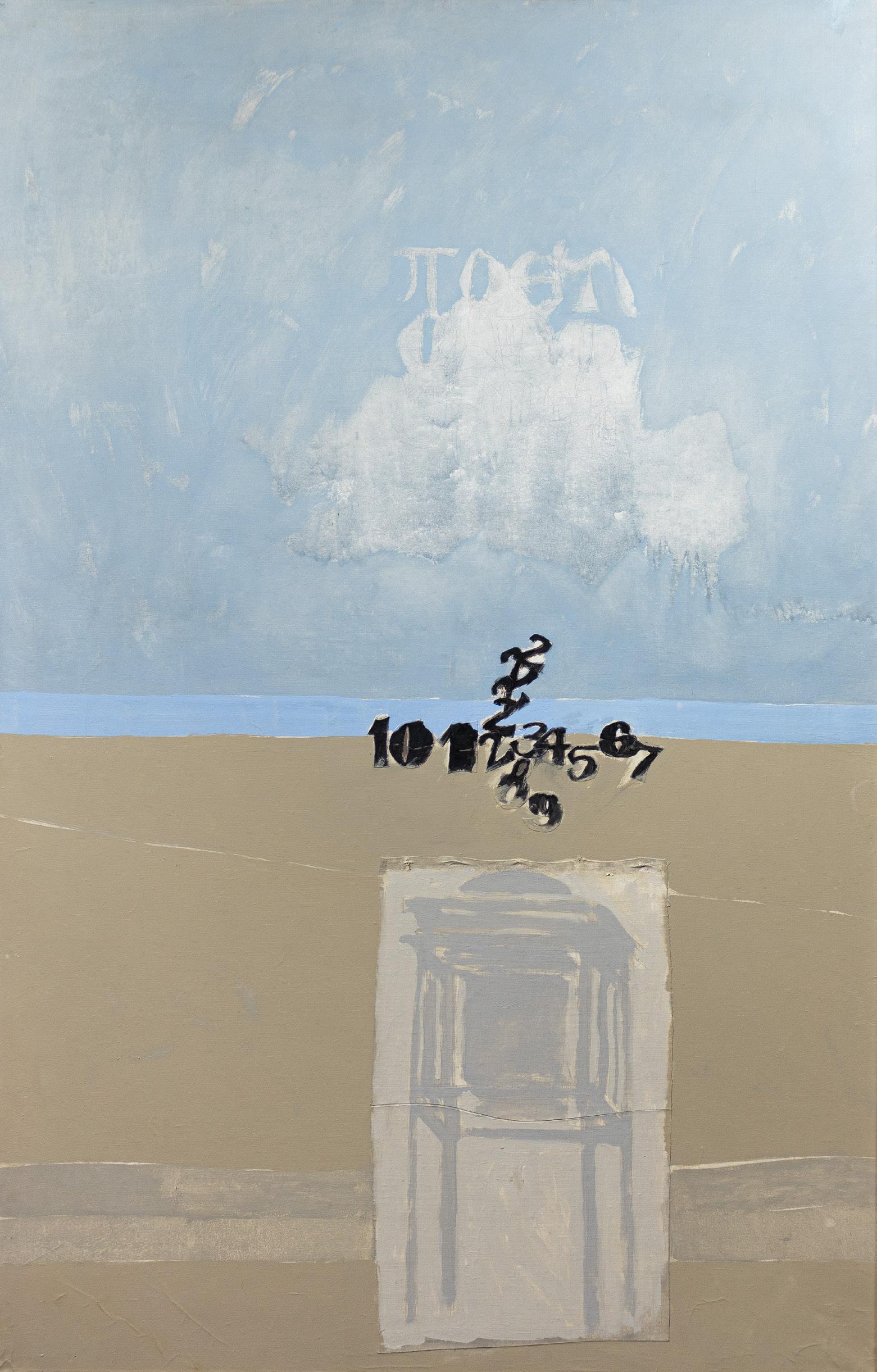

Born in 1922 in Kansas City, Missouri, Phillip Hampton studied art at the Kansas City Art Institute. Throughout his career, he inspired, not only with his art, but with his teaching. He was an associate professor of art and design at Savannah State College between 1952 and 1969, and associate professor of painting and design at Southern Illinois University, Edwardsville.

His work has been exhibited at Atlanta University, 1958; Telfair Museum of Art, Savannah, GA, 1959; National Watercolor and Print Competition, Knoxville, TN, 1964; Lincoln University, 1966; Beaux Arts Guild, Tuskegee Institute, AL, 1967(purchase award), A&M University, 1968; Savannah Art Association, 1969; Smith-Mason Gallery, Washington D.C., 1971. Most recently, he was featured in the exhibition African American Abstractions: St. Louis Connections at the St. Louis Art Museum, 2008; as well as an exhibition at the Regional Arts Commission Gallery in St. Louis, 2009.

Hampton continues to approach art from an analytical and scientific point of view, his work inspired by the self-imposed question, “What is reality and what makes reality real?”

Phillip Hampton has been devoted throughout his long artistic career to investigations of abstract form and its relationship with objects from the visible world. He sees reality as that which is perceived via our sense, and that which is cerebral—derived from dreams, experiences or ideas. The aggregate forms that emerge from both levels of reality unite in the artist’s…paintings. Hampton studies the techniques of the old masters, the art of life and the unique spatial qualities of Asian art, employing the spatial and formal systems in his work.

-New Acquisitions, Saint Louis Art Museum Magazine (Spring, 2000): 13: Print.

Autobiography Series, c.1970 Acrylic, string and collage on canvas 60 x 36 inches signed

Illustrated: Feels Like Freedom, Phillip J. Hampton (1922-2016), Telfair Museums, 2022, p. 137.

Benjamin W. Hazard is a painter, sculptor and graphic artist. He studied at the California College of Arts & Crafts and at University of California at Berkeley (MFA, 1969).

Hazard’s early works, such as Bird with Dead Mate, 1967, (seen in Black Artists on Art Vol. 1 Revised) address social issues, especially those relating to civil rights and the U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War. In the early 1970s, he turned to more abstract subjects and used acrylic forms, such as his Modular Series II . These works addressed the harmony between what is created and the natural environment. The high-gloss surface and burnished metallic colors serve as a kaleidoscope of reflected light and adjacent forms. (REF: Diedre Cross, St James Guide to Black Artists, p. 240-241).

[Hazard] works in sheet acrylic, but he handles his forms [by] assembling his vacuum-formed plastic components in low relief. Hazard’s Modular Series II, simple in form, is composed of several interlocking shapes. The highly reflective surface is made rich and interesting through the refraction of light and the election of surrounding forms.

Samella Lewis, Art African American, 1978, pp.185-186

Hazard executed the Tuskegee Airmen Monument in Albuquerque, NM, in 2013. He was also a curator at the Oakland Art Museum. He taught African American Art at the University of New Mexico. In St James Guide to Black Artists, Deirdre Cross writes, “Throughout his career Hazard’s paintings, drawings, and installations have exhibited a characteristic emotional intensity and colorful vibrancy.”

Illustrated: Black Artists on Art, Volume 1 (revised), Samella Lewis and Ruth Waddy, 1969, p. 56.

Untitled, 1985 oil stick on gessoed paper 47-1/2 x 53 inches signed and dated

Provenance: acquired directly from the artist by Julia E. Harris, Chicago

Jackson was born in St Louis and studied at Illinois Wesleyan University (Bloomington, IL, BFA) and University of Iowa (MFA, 1963). His solo exhibitions include the National Gallery of Art (2019), Contemporary Art Museum, St Louis (2012), Harvard Universi ty, Crocker Art Museum (Sacramento), UC Berkeley, Seattle Art Museum, St Louis Art Museum, UC Santa Barbara.

Along with visual artists Manuel Hughes and Emilio Cruz, Jackson was associated with BAG (Black Artists’ Group) in St Louis in the late 1960s-early 1970s. This collective held inter-disciplinary exhibitions/performances which included elements of theater, poetry, dance, music and visual arts.

Lizetta LeFalle-Collins makes the crucial point to Jackson’s work in St James Guide to Black Artists, (p.268) :

“Form an essential element of life and of all art, is at the heart of Oliver Jackson’s work, but the most riveting thing about his artwork is the nervous energy created by his brushwork. Figuration is critical to his work…His work is clearly influenced by his presence in the San Francisco Bay Area, where figuration refused to take a back seat to the pure painting of abstract expressionism.”

Protect Home Africa, c. 1970 pastel on cardboard 35 x 24 inches signed Provenance: the collection of the artist, her estate Recognized for her political, pro-Black images combining figuration with energetic, graphic lettering, Barbara Jones-Hogu is closely identified with a 1969/71 print titled, Unite. In recent years, the work has been featured in major group exhibitions documenting the contributions and expressions of African American artists during the Civil Rights Movement and Black Power eras, including Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power, the seminal show organized by the Tate Modern in London. In January 2018, Barbara JonesHogu: Resist, Relate, Unite 1968-1975, her first-ever solo museum exhibition opened at the DePaul Art Museum in Chicago.

Jones-Hogu was at the center of the black arts scene in 1960s Chicago. As a member of the Visual Artists Workshop of the Organization of Black American Culture (OBAC), she helped paint the Wall of Respect on Chicago’s South Side in 1967. Paying tribute to more than 50 African American figures, the project is regarded as the first collective street mural in the United States. It revived the mural movement in neighborhoods across the nation, black ones in particular. Jones-Hogu later wrote that the Wall of Respect “became a visual symbol of Black nationalism and liberation.”

In 1968, the year after contributing to the legendary mural, Jones-Hogu helped cofound AfriCOBRA, an artist collective with Jeff Donaldson (1932-2004), Wadsworth Jarrell, Jae Jarrell, and Gerald Williams.

(Donaldson and Wadsworth Jarrell were active in OBAC, too.) Initially called COBRA, then African COBRA, the group settled on the name AfriCOBRA, which stands for African Commune of Bad Relevant Artists. The collective focused on positive, powerful, and uplifting images of black people.

The group held regular meetings in Jarrell’s studio and established a set of principles and a collective aesthetic. Their visual themes included syncopated, rhythmic repetition; balance between abstraction and absolute likeness; bright harmonious colors; and active lettering, which was JonesHogu’s contribution. In the wake of racism and injustice, AfriCOBRA produced work that put forth a visual counter-narrative that was about affirmation of African American heritage. The goal was to change the community’s mindset and positively influence its outlook.

Barbara Jones-Hogu’s prints were visually complex and in terms of subject matter focused on black women in the liberation movement, solidarity in the black community, and preserving the black family. Titles of her works include, Rise and Take Control (1970), Relate to Your Heritage (1970), and Black Men We Need You (circa 1971). The latter print is in the collection of the Studio Museum in Harlem. Other works have been placed with the Smithsonian American Art Museum, Brooklyn Museum, and the Art Institute of Chicago.

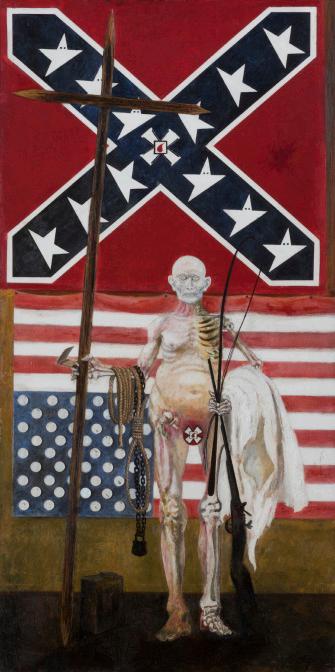

Superman, 1966 oil and mixed media (pennies) on board 48 x 24 inches signed, dated, and titled Provenance: the collection of the artist

Exhibited: Afro American Artists New York and Boston, The Museum of the National Center of Afro-American Artists, The Museum of Fine Arts, The School of the Museum of Fine Arts Boston, May 19-June 23, 1970.

Counter Currents: The New Humanism, The Humanist Center at Aida Hernandez Gallery, NY, 1974

Rebuttal to the Whitney Museum Exhibition, Acts of Art Gallery, NY 1971 (Illustrated)

Acts of Art and Rebuttal in 1971, Hunter College Art Galleries, 2018 (Illustrated, p. 75 and also p. 47)

Illustrated: Cliff Joseph, Artist and Activist, Thom Pegg, (2017) p. 23.

Mounting Frustration: The Art Museum in the Age of Black Power, Susan E. Cahan, p. 167.

In the years leading to the US Bicentennial (1976), Chandler, Joseph, Charles White (1918-1979), Ringgold, Hammons, and many other black artists pursued similarly politicized representations of the American flag. As Ringgold remarked, ‘The flag is

the only truly subversive and revolutionary abstraction one can paint.’

Doss, Erika. “Feminist and Black Art: Black Protest.” Oxford History of Art, Twenti eth-Century American Art, Oxford Universi ty Press, 2017, p. 196.

Superman is an important image for Joseph. It was the work he chose to include in the Rebuttal to Whitney Exhibition in 1971. It is a difficult image for most people: the spec tral figure of a Klansman and his props: a cross, matches and gasoline; a whip, shack les, his sheet and a gun. He stands before the Confederate flag on top, with the stars constructed of abstracted hooded figures, and the American flag on the bottom, upside down. The stars of this flag made of Lincoln pennies glued on to the surface and painted white, each (also) upside down.

The composition is remarkably similar to Gordon Parks’ photograph from 1942, American Gothic, Washington, D.C. Parks was given a fellowship by the FSA to doc ument black lives in the region, and photo graphed government cleaning woman, Ella Watson. Parks took the image to his super visor, Roy Stryker, who “told me I’d gotten the right idea but was going to get all the FSA photogs fired, that my image of Ella was ‘an indictment of America.’ Parks’ image was done as a parody of Grant Wood’s fa mous painting from 1930, American Gothic, and Joseph’s Superman acknowledges both earlier works, and was without a doubt, “an indictment of America.”

The Lynching, n.d. mixed media on board 24 x 16 inches

I’m African American and these are my experiences. I paint about my people.

Yvonne Meo was born in Seattle, Washington, and studied at UCLA and California State College. Meo was primarily a sculptor and printmaker. She exhibited at the Oakland Museum (a work by her is included in their permanent collection), and had a solo exhibition at Fisk University. She taught in the Los Angeles Public School System and at Fisk. Meo was encouraged by Charles White to show her work in galleries in Los Angeles during the 1960s. An example of her work may be seen in Black Artists on Art, vol 1 by Samella Lewis and Ruth Waddy.

Mixed media artist, Sam Middleton was one of a group of expatriate African Americans who enjoyed success in Europe in the 1960’s. Middleton was born in New York City and grew up in Harlem near the Savoy Ballroom. This notable venue provided much inspiration for his future collages. His love of music - classical and jazz - was integral to his very life - he was known to carry an unwieldy turntable and collection of records with him wherever he traveled.

He joined the Merchant Marines in 1944. Upon his return to New York City in the 1950s, he relocated to Greenwich Village, meeting and befriending a small group of African American artists including Walter Williams, Clifford Jackson, Harvey Cropper, and Herb Gentry - all of whom would expatriate to Europe in the next decade In the early 1950s, Middleton was part of New York’s Cedar Tavern scene, which included his friends Robert Motherwell and Franz Kline. Kline encouraged Middleton to apply to the John Hay Whitney Foundation and advised him to seek artistic success outside New York.

Middleton received a scholarship for one year of study at the Instituto Allende in San Miguel, otherwise he was largely selftaught. It was there in 1957, that he began experimenting with collage. His work was

shown at Contemporary Arts Gallery in 1958 and again in 1960. The Whitney Museum of American Art showed four of his works in Young America 1960: Thirty American Painters Under 36

Between 1959 and 1961, Middleton lived in Europe, exhibiting in Spain, Sweden, and Denmark. Much of his artistic material was gleaned from ephemera he collected as he moved from city to city. In 1962 he decided to make a home in the Netherlands. His later work brought the Dutch landscape into his collages.

Middleton remained in the Netherlands for the rest of his life. He showed extensively there and other locales throughout Europe, but was not forgotten in the States. In 1970, his work was shown in the exhibition, Afro-American Artists Abroad at the Blanton Museum of Art, University of Texas, Austin and in 1983, the Studio Museum in Harlem held the exhibition An Ocean Apart: American Artists Abroad which also included Herb Gentry, Cliff Jackson, and Walter Williams.

His work is found in the collection of the Whitney Museum of American Art, NY; Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, NL; Fisk University, Nashville, TN; Brooklyn Museum, NY, as well as many others.

Beach Scene (Door of No Return), c. 1970 oil and collage on canvas 65 x 42 inches signed and titled

Painter and fine arts professor Robert Dennis Reid was born in Atlanta, GA. He studied at Clark College, GA; Art Institute of Chicago; and Parsons New School of Design, NY. Reid worked as a fashion illustrator and taught fashion illustration, drawing and design at the Rhode Island School of Design. His first one man show was held at Grand Central Moderns, NY in 1965, and featured paintings that tended “toward poetic imagery, projecting forms and symbols that have little to do with nature.” (The Afro-American Artist, Fine, p. 215). Reid’s exploration in oils, watercolor, and later, collage tended towards the abstract. His background in illustration, led him to be incredibly adept at his approach to watercolor.

“Despite disparate elements, “ Harry Henderson writes in St. James Guide to Black Artists, p.450, “Reid achieves an acute sense of balance that is both vertical and horizontal. Color is the critical element he uses to achieve this balance, and he is very sensitive to the order in which each color is laid down. Reid credits Byzantine art and the Book of Hours with influencing his concept of balance.”

In addition to solo exhibitions at Grand Central Moderns, he was also represented by Alonzo Gallery in the 1970s and exhibited at June Kelly Gallery in the 1990’s. His work was featured in the group exhibitions Ten Negro Artists from the United States / Dix Artistes Negres des Etats-Unis, Washington DC, 1966; Four Artists, Indiana University Art Museum, Bloomington, 1969; Black American Artists/71, Chicago, IL, 1971; Black Artists/South, Huntsville Museum of Art, AL, 1979; 30 Contemporary Black Artists, Minneapolis Institute of Arts, 1968; Black Artists: Two Generations, Newark Museum, NJ, 1971; and The Search for Freedom: African American Abstract Painting 1945-1975, Kenkeleba House, NY.

Figure on a Beach, 1960 oil or acrylic and collage on stretched canvas 20 x 24 inches signed and dated

Untitled (Middle Passage Series), c. 1990 acrylic and found object collage on board 24 x 24 inches signed

Provenance: the collection of the artist

A native of St. Louis, Missouri, John Rozelle is a prolific painter and collagist. Rozelle attended Washington University, St. Louis, where he received a BFA and Fontbonne College, where he received a MFA. He served as an associate professor in the Drawing and Painting Department at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago from 1990-2009. Prior to joining the Art Institute faculty he taught drawing, design, painting, and sculpture at Fontbonne College. In 1989, Rozelle was artist-in-residence at the Studio Museum in Harlem.

His work has been featured in exhibitions including I Remember...Thirty Years After the March on Washington: Images of the Civil Rights Movement 1963-1993, Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington D.C., 1993; The Chemistry of Color: African American Artists in Philadelphia, 19701990, Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, PA, 2005; Layers of Meaning: Collage and Abstraction in the Late 20th Century, Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, PA, 2003; The Studio Museum in Harlem: 25 Years of African-American Art, NY, 1994; African American Abstraction: St. Louis Connections, MO, 2008.

In 1998, Rozelle was commissioned to install the Middle Passage Project at the Dred Scott Courthouse in St. Louis, MO. Museum collections include the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, PA; Margaret Harwell Museum, Spertus Museum of Jewish Studies, Chicago, IL; The Studio Museum in Harlem, NY; California Afro-American Museum, Los Angeles; and The Museum of African American Art, Los Angeles.

... As an artist, Rozelle seems to have zeroed in on this uncompromising balance, one which allows him to cite influences of all kinds without having to suppress personal and cultural history. His intricate collages, products of a fertile imagination and a skilled hand appeal to us not because they are from the mind of a black artist; they appeal to us solely on the grounds that they come from a gifted artist.

-Jeff Daniel, critic for the St Louis Post-Dispatch

Apathetic Angel, 1987 assemblage of tin (recycled being panels), paint and clay 81 x 51 inches

Signed and dated

As the daughter of artist Betye Saar, Alison Saar had an intimate preview of the challenges facing the African American female artist. She received a dual degree in art history and studio art from Scripps College in Claremont, California, and also studied at the Otis Art Institute in Los Angeles. She is primarily a sculptor and printmaker and began having solo shows at the age of just 26. From her mother, Alison inherited a fascination with mysticism, found objects, and the spiritual potential of art.

Much of her work explores African culture and the human body, gender and race through both her personal experience and historical context. Her sculptures and assemblages are often life-sized and contain a highly personal narrative.

Her work is included in the collections of the Museum of Modern Art, Indianapolis Museum of Art, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, and the Brooklyn Museum. She was included in the Whitney Biennial and had solo shows at the Hirschhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden and the Studio Museum in Harlem. Saar lives and works in Los Angeles, California.

Before the Mayflower, 1972 oil and collage on canvas 48 x 44 inches signed, dated, and titled Brooklyn native Vincent Smith documented some of the most compelling events in 20th century America, from the jazz clubs of the New York avant garde music scene, to the burgeoning civil rights movement, and the Black Arts Movement. After a tumultuous youth, Smith found new direction in art, a vocation he completely immersed himself in, both as a student and as a working artist. He took classes at the Brooklyn Museum of Art School and the Art Students League, NY. He traveled to Maine to study on scholarship at the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture. Smith drew inspiration from African-American artist Jacob Lawrence and was mentored by Lawrence and Romare Bearden.

His first solo show was held at the Brooklyn Museum Art School Gallery in 1955. He participated in numerous prestigious exhibits throughout his career, including at Roko

Gallery (NYC), 1955; Market Place Gallery, Harlem, 1956-58; CORE (NYC), 1966; National Academy of Design, 1967; Studio Museum in Harlem, 1969 (one-man); Fisk University, 1970; Pratt Graphics Center, 1972-73; Brooklyn College, 1969; Boston Museum of Fine Arts, 1970; Illinois State University, 1971; Whitney Museum, 1971.

Smith curated the show, Unbroken Circle: Exhibition of African-American Artists of the 1930’s and 1940’s, held at Kenkeleba House, NY in 1986.

His work can be found in many private and public collections such as The Art Institute of Chicago, MoMA New York, The National Museum of American Art in Washington D.C., The Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, the Detroit Institute of Arts, and Yale University, New Haven.

Thelma Johnson Streat was a multi-talented painter and dancer who focused her career on promoting ideas of multi-culturalism and raising the social awareness of inequalities among the lines of gender and race.

Thelma Johnson Streat was born in Yakima, Washington in 1912, and spent he childhood in Portland, Oregon. She graduated from high school in 1932, and that same year sold four of her artworks to the famous African American singer, Roland Hayes, who was living in Los Angeles. She also exhibited two works at the New York Public Library in a show sponsored by the Harmon Foundation that year. She exhibited at the American Negro Exposition (1940) in Chicago, and along with Sargent Johnson, was listed as one of two African American artists working in California.

Streat worked as an assistant to Diego Rivera in the early 1940s, and Rivera wrote a letter to Los Angeles-based dealer and collector, Galka Shayer, saying, “The work of Thelma Johnson Streat is, in my opinion, one of the most interesting manifestations

in this country at the present. It is extremely evolved and sophisticated enough to re conquer the grace and purity of African and American art.”

She continued to use the genre of murals to address social inequality toward African Americans in the early 1940s, after she arrived in Chicago. By the mid-1940s, her style became increasingly abstract, taking on a neo-primitivist feel, appropriating symbolism from many diverse cultures in an effort to communicate more universally. This turn in style has caused her work to be associated (in retrospect) with the Abstract Expressionists of the late 1940s and early 1950s.

In 1946, Streat added dance to her work. Her multi-dimensional performances and exhibits were the first of their kind, with Streat performing modern dance movements in front of paintings she had done that were thematically associated.

Untitled, c. 1976 acrylic on canvas 28-3/4 x 16-3/4 inches signed

Provenance: The Collection of Dr Diane Whitfield-Locke and Dr. Carnell Locke, Maryland

Exhibited: Building on Tradition, The Collection of Dr. Dianne Whitfield-Locke and Dr. Carnell Locke, Hampton University Museum, October 12, 2013-Decmber 7, 2013.

Literature: International Review of African American Art, vol. 24, 3B, Hampton University Museum, VA (illustrated)

Expressionist painter and art educator Alma Thomas was born in Georgia in 1891. Her family moved to Washington D.C. while she was in her mid-teens, where she lived and worked for the rest of her life. Thomas enrolled in Howard University, studying under James V. Herring and became the first graduate of the newly organized art department in 1924. She began teaching after graduation, but continued studying art and painting part-time. In 1946, she joined Lois Mailou Jones’ Little Paris group, members of which sketched, painted and exhibited together in the Washington D.C. area. She studied painting at American University under Joe Summerford, Robert Gates, and Jacob Kainen; all of whom inspired her to look at the structure of a painting differently and use color as a single, qualitative element.

When she retired, she began painting in earnest. Her work evolved from more traditional styles and themes to fully realized abstract works that explored color and composition which reflected her own unique vision of nature as well as

incorporating influence from the Washington Color School. She was also known as a brilliant watercolorist. Her first retrospective exhibition, curated by James A. Porter, was held at Howard University in 1966. For this show, she created the Earth paintings, a series of works inspired by nature that resembled Byzantine mosaics. In 1972, she became the first African American woman to be given a solo exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art, NYC. Soon after she exhibited at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington D.C.

After seeing an exhibit of Matisse’s late gouache collages at the Museum of Modern Art, 1961, she began experimenting with rearranging geometric shapes. Thomas carefully calibrated the colors in the positive and the negative.

Thomas’s work is found in many museum collections including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Corcoran Gallery of Art, Whitney Museum of American Art, Phillips Collection, Hirshorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, and the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

In 2009, two of her paintings, Watusi (Hard Edge) and Sky Light were chosen by First Lady Michelle Obama to be exhibited during the Obama presidency. Several retrospective exhibitions have been dedicated to her work, including A Life in Art: Alma Thomas, 1891-1978, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C., 1981; Alma W. Thomas: Retrospective Exhibition, Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., 1972.

The Columbus Museum, GA and the Chrysler Museum of Art, VA presented a comprehensive retrospective of her work entitled, Alma W. Thomas: Everything is Beautiful in the summer of 2022. In addition to showing at these locations, the exhibition was presented at The Phillips Collection, Washington D.C. and the Frist Art Museum, Nashville, TN.

Bill Walker was born in 1927 in Birmingham, Alabama. An only child, he was initially raised by his grandmother in a desperately poor ghetto of “bleak little shacks” with outhouses known as Alley B. In 1938, he was sent north to Chicago to join his mother who worked as a seamstress and hairdresser. They lived in a variety of places in the Washington Park area and he eventually attended Englewood High School.

Walker was drafted in WWII and re-enlisted to receive college tuition under the GI Bill. He was a mail clerk, then an MP with the 99th Pursuit Squadron, the all black command under which the Tuskegee Airmen fought. In 1947, he painted his first murals while in the military. While stationed in Columbus, Ohio he became friends with Samella Lewis. He often stayed with her family and assisted her on a few commissions.

In 1949 he enrolled in the Columbus Gallery School of Arts. He began studying commercial art and later switched to a concentration in fine art. Walker won the school’s 47th Annual Group Exhibition “Best of Show” award in 1952. He was the first African-American to do so.

By the mid 1960s, Walker was formulating an idea for a mural in the area near 43rd and Langley which never came to fruition. However in May of 1967, the Organization of Black American Culture was formed and the opportunity again arose. OBAC was cofounded by artist Jeff Donaldson, sociologist Gerald McWorter, and Hoyt Fuller, editor of Negro Digest, and was dedicated to visual art, music, writing, dance, and theater. Walker floated the idea of a mural at the location. The group couldn’t just simply paint a mural and leave it at that.

Struggle, 1967 acrylic on canvas 53 x 38-1/2 inches signed, dated, and titled Provenance: private collection, Chicago, Illinois

Walker knew the neighborhood well and secured permission from business owners, community leaders, and street gangs. The residents were a big part of the process as well. Jeff Donaldson and Eliot Hunter, Wadsworth Jarrell, Barbara Hogu-Jones, Caroline Lawrence, Norman Parish, Edward Christmas, Myrna Weaver and many others contributed sections to the wall. As a result of the impact the Wall of Respect had in Chicago, similar walls were created in cities across the country. Walker worked on the Wall of Dignity in Detroit and the Wall of Truth, which was located across the street from the Wall of Respect. He co-founded the Chicago Mural Group (now known as the Chicago Public Art Group) with John Pitman Weber and Eugene Eda and completed more than 30 murals over the next four decades in working-class Chicago neighborhoods. In 1975, he formed his own mural group known as International Walls, Inc.

Walker turned increasingly to studio art in the late 70’s. Chicago State University held the exhibition, Images of Conscience: The Art of Bill Walker in 1984. The exhibition consisted of 44 paintings and drawings in three series: For Blacks Only; Red, White, and Blue, I Love You; and Reaganomics The show was not without controversy as the images presented were not pretty, but dark representations of urban black neighborhoods. The exhibition traveled to the Vaughn Cultural Center, St. Louis and the Paul Robeson Cultural Center, Pennsylvania State University.

Most recently, Walker’s work was presented in the exhibition Bill Walker: Urban Griot, held at the Hyde Park Art Center, 2017-18.

Untitled, Two Boys and a Butterfly, 1965 oil and gold leaf on paper 20 x 25 inches signed and dated Painter, printmaker, and sculptor, Walter Williams studied art at the Brooklyn Museum Art School under Ben Shahn, Reuben Tam, and Gregoria Prestopino. He also spent a summer studying art at the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture in Maine. In 1955, Williams won a Whitney Fellowship that permitted him to work and travel in Mexico. He also won a National Arts and Letters Grant in 1960 and the Silvermine Award in 1963.

Williams moved to Copenhagen, Denmark in the 1960’s to escape the discrimination of the United States, While he was in Copenhagen, he created a series of colorful woodcuts of black children playing in fields of flowers. He returned to the United States to serve as artist-in-residence at Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee. Here, he

completed a body of work informed by the experiences of being an African American living in the South. Walter H. Williams died in Copenhagen in June1988.

Williams’ work has been featured in major exhibitions including, An Ocean Apart: American Artists Abroad, Studio Museum in Harlem, NY, 1983; Unbroken Circle: Exhibition of African American Artists of the 1930s and 1940s, Kenkeleba House, NY, 1986; Black Motion, SCLC Black Expo 72, Los Angeles, CA; Two Centuries of Black American Art, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1972; and 10 American Negro Artists Living and Working in Europe: paintings, prints, drawings, and collages, Den Frie, Copenhagen, Denmark, 1964.

Untitled, c. 1975 acrylic on canvas 58-1/4 x 93-3/4 inches

Founded in 1969 in historic Bahamian West Coconut Grove, the Miami Black Arts Workshop (MBAW) provided a community space for Black artists. Some artists represented include Roland Woods, Jr., Robert McKnight, Donald McKnight, Dinizulu Gene Tinnie, and Pamela Kabuya BowensSaffo. Community activists, as well as artists, these leaders created a powerful space in Coconut Grove through the MBAW, a venue that welcomed young people to learn about art and activism.

The MBAW also provided cultural and educational programs, including mural workshops, after-school tutoring, free breakfast programs, children and adult art classes, and community art exhibitions.

Roland Woods Jr., a founder of the arts workshop, worked with other members to paint local businesses’ facades to improve individual business successes. The neighborhood of West Coconut Grove was also a creative inspiration for Woods as he produced watercolors that celebrated daily life experiences in the community.

Woods’s political work is evident in Pitts and Lee (1977). This print memorializes the injustices experienced by Freddie Pitts and Wilbert Lee, two Black men who were wrongfully convicted and imprisoned for the 1963 killings of two White men. There was no evidence to support their conviction, and a White man confessed to the crime in 1966 — but it took until 1975 for Florida Gov. Reubin Askew to issue a pardon.

While the artists at the workshop engaged in many different media, printmaking was vital for raising awareness for broader audiences. Rather than limiting and tracking the edition numbers for each print to boost their economic value, Woods printed many images of a singular image and even varied titles. Woods’s art spread knowledge and shared imagery that frequently addressed societal discord or the unity and strength of Black families. As a result, art forged community rather than yielding profits.

REF: The Museum of Contemporary Art North Miami (2019), Africobra: Messages to the People.