The Importance of Handover in Intensive Care: A Quality Improvement Project

Dr Sharon Rajesh, Dr Mariya Rajesh, Dr Elizabeth Aloof, Dr Dao Jittasaiyapan, Dr Ahmed Nazari

Dr Sharon Rajesh, Dr Mariya Rajesh, Dr Elizabeth Aloof, Dr Dao Jittasaiyapan, Dr Ahmed Nazari

Background

Effective communication between staff in the form of a handover has been a general practise throughout hospitals and often occurs during the changeover of staff at the beginning and end of shifts. The guidelines for the Provision of Intensive Care Services state that consultant lead ward rounds must occur twice a day with daily input from nursing staff, it was found that at Northampton General Hospital (NGH) Intensive Care Unit there is one handover and consultant lead ward round in the morning, an informal handover between day and evening staff and a formal handover in the evening which did not meet guidelines.

The Problem

The intensive care at Northampton General Hospital is split into 2 halves, East and West side. Doctors working on the day shift are heavily involved in patient care on one side of the unit, whereas doctors who work late shifts are expected to manage patients from both sides of the unit.

Currently, there is no formal handover between the morning and late shifts meaning that the late shift staff do not have up to date knowledge of issues occurring and decisions made on the opposite side.

A preliminary survey found that 41.7% of staff found the informal evening handover inadequate and 50% of doctors spend time at the beginning of their evening shift looking through patient notes.

What are we trying to achieve?

• Efficient communication between the day and evening staff as well as medical and nursing staff in order to maintain patient safety and ensure continuation of care.

• Any jobs missed during the day can be handed over efficiently. This will allow the late shift team to gain a clear understanding of the decisions made during the day and will aid patient safety.

Phase 1:

Changes made from phase 1

Phase 2:

Our Solution

• Phase 1: implement a 5pm ward round during the afternoon whereby the junior doctors, consultants and nursing staff would handover patients to the evening staff at each bedside.

• Phase 2 : Make changes and improve on our 5pm ward round using feedback from Round 1.

Results

• The handover time is fluid: anytime between 4pm-6pm

• Only the on-call consultant needs to join if the day shift consultant has already handed over

• Creation of a new jobs book to document the afternoon jobs created and follow up on any day jobs

Survey results found that after the round 100% were more confident in managing the patients at NGH ICU, 60% expressed that the afternoon round provided clarity regarding management plans, main problems and 100% of staff agreed that the round improved communication. During the first cycle 88% of jobs were completed, outstanding issues were identified, and jobs were created during the handover which otherwise would have been left for the next morning ward round. During the second cycle 91% of jobs were found to be completed

Conclusion

Twice daily ward rounds which include nursing and medical staff improve communication and confidence between staff and ensures the continuation of high-quality care throughout the day and night.

QI Project Improves the Communication Between Inpatient Perinatal Psychiatry and Primary Care,

Leading to Better Continuity of Care

Background

The standard operating procedure (SOP) for inpatient discharge letters states they should be sent to the patient’s GP within 48 hours of discharge. This target ensures continuity of care, safer ongoing prescribing and sharing information pertaining to risk in a timely fashion. Discharge letters also provide key details around management, risk to the community teams and also have any information ascertaining to follow-ups that have been arranged.

Problem Identified

A delay with discharge letters being created and sent was identified, caused by the below issues.

1. Discharge letters are very detailed, and so it was taking a long period of time to create each letter.

2. Discharge letters were being started when a patient had been discharged from the ward, and this was leading to a delay in the letter being sent out.

3. Letters were being written by one individual.

4. There were delays in the letters being approved by the consultant.

5. There was a delay in letters being sent out following consultant approval.

Addressing the Problems (Planning)

A Plan, Do, Study, Act (PDSA) model was implemented to help improve the creation and distribution of discharge letters.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

• Content of the discharge letters was explored. Concluded that the discharge letters still needed to be as detailed.

• Different approach to writing was required

Data Collection

• Letters needed to be started at the beginning of admission

• Letters needed to be updated on an ongoing basis

• Sharing of responsibility required to avoid delays

• Shared drive ensures no duplication of work, increasing efficiency

• Updating letters with new review information at the time

• Letter ready for approval on the day of discharge

• Letter can be read and approved by Consultant following discharge meeting

• Shared drive allows easy access for Consultant

Data and Results (Do and Study)

• 10 letters prior to, and 10 letters following PDSA implementation were assessed via Rio.

• Date of discharge and date of discharge letter being sent were recorded.

Analysis

Pre-implementation:

• Average time to send a discharge letter to the GP was 12 days

• Time range for letters to be sent was 1-28 days

• 30% compliance with the SOP timeframe

• 2 letters took 28 days to be sent

Figure 1: A comparison of the number of days it took to send discharge letters pre- and postimplementation of the PDSA model

Outcomes:

• Discharges letters sent out on time

• Previously unknown if letter had Consultant sign off

• Area in shared drive created for approved letters

• Ward clerk able to access this area and send letters sooner

Post-implementation:

• Average time to send a discharge letter to the GP was 1 days

• Time range for letters to be sent was 1-4 days

• 80% compliance with the SOP timeframe

Figure 2: A comparison of the average time it took to send discharge letters preand post-implementation of the PDSA model

Pre-Implementation Post-Implementation

Figure 3: A comparison of the time range it took to send discharge letters pre- and post-implementation of the PDSA model

Outcomes and Learning Points (Act)

Learning Points:

• Importance of shared responsibility

• Improvement from 30% compliance with SOP to 80%

• Reduction in maximum time between discharge and letter being sent (28 days to 4 days)

• Streamlining a process to ensure greater efficiency

• These concepts directly lead to better continuity of care and patient centred care

• QIP leading to better patient safety

BACKGROUND:

In-hospital cardiac arrests[1]

• 1 – 1.5 per 1000 admissions

• Average age = 70 years

In treated patients[2]

• 44% ROSC

• 17% survive to discharge

Frailty[3]

• Rockall Clinical Frailty Score

• Associated with increased mortality after cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR)

Do Not Attempt Resuscitation (DNAR)

• Introduced in 1970s

• Clinical decision

• In line with Equality Act 2010 and Human Rights Act 1998

• Avoids CPR in those:

• With low chance of successful outcome

• Who do not want CPR

✓ Patient has capacity

✓ Discussion with patient/relatives

✓ Senior doctor endorsement

Treatment Escalation Plans (TEP)

• Ceiling of care

Plan:

- All patients should have TEP +/- DNAR documentation in place on the ward

Standards

Royal College of Physicians guidelines

DISCUSSION AND KEY CONCEPTS:

• Efficient and timely TEP and DNAR assessment is important to provide best care for patients, particularly those that are frail.

• Trust wide initiatives can help to improve rate of assessments, and reminders have less of an effect.

• Includes medical emergency treatment (MET) calls and Last Days of Life Care Agreement (LDLCA)

In a Care Quality Commission review[4], it was noted that documentation was not in line with best practices at our trust.

AIM:

To audit Do Not Attempt Resuscitation (DNAR) and Treatment Escalation Plan (TEP) documentation using 3 Plan, Do, Study, Act (PDSA) cycles[5]

1. Ward Rounds in Medicine (2012)[6]

“making decisions about future investigations and options for treatment, including DNAR (do not attempt resuscitation) and any ceilings of care”

2. Modern Ward Rounds (2021)[7]

“recognising patients who may be in their last year of life, and commence conversations around advance care planning…Escalation plans and ‘Do not attempt resuscitation’ (DNAR) orders should be reviewed and documented and shared with patients as appropriate”

Do:

- Evaluate rate of DNAR and TEP documents for all patients

- Consecutive data from endocrinology patients from two separate wards

- Paper and online notes

1. Cycle 1: February – March 2022

2. Cycle 2: May – June 2022

3. Cycle 3: June – July 2022

Study: Cycle 1

Act: Cycle 1 intervention

• Sticky label reminder

• Local departmental meeting Cycle 2:

• Trust wide meeting with acute medical consultants

BeforePTWRPTWR1dayafter2daysafterNotdone

• Regular reminders are essential to ensure consistent assessment with changeover of staff. 1 2 3 4

Cycles 1, 2 & 3 comparison

Planning for transition for Children with Complex Needs –a work in progress using QI for better outcomes for patients and

families.

Elly Kerr – Specialist Nurse for Children with Complex Needs, Transitions Nurse , Children with Complex Needs Team, Milton Keynes Community Health Services, with thanks to the whole Children with Complex Needs team.

Introduction Aims

The Children with Complex Needs Team look after paediatric patients with complex health needs and life limiting conditions in the community. Our caseload ranges from birth to the age of 19 and children have a wide range of life-limiting and life-threatening conditions. We did not have a standardised procedure for supporting these young people in their transitioning journey to adult services, often only starting to plan for transitions around their 18th Birthday.

This is not in line with NICE guidance which states that planning to support paediatric service users for adult services should start from the age of 13. Transition planning should be an ongoing process, rather than an event.

The delay in commencing transition planning early on has a negative impact in preparing the young person and the family for the move to adult services. The transition between paediatric services can be an overwhelming for our young people and their families and cause feelings such as loss, confusion, lack of continuity which can therefore lead to an impact on health. 1 As a team we are passionate in advocating for those in our care and their families, to ensure a clearer pathway to adult care is set up in order to aid the process and reduce fears/anxieties of parents and carers.

This project began by looking at ensuring that all young people on our caseload were contacted about transition planning from the age of 13. As the project developed, we have started working on a range of new processes which we are putting in place with partners and will refine as part of the next stages of the improvement work that we will continue during 2023.

To increase our rates of transition planning from 2% to 95% for the Paediatric Complex Needs caseload, by March 2023;

To ensure that those young people with the most complex needs are identified and receive the support they need during transition to adult care;

To improve and increase awareness of transitional care processes for young people with complex needs and their families in Milton Keynes;

To ensure better hand over of care from paediatric services, to adult services, with clear processes in place to support critical areas of care and support.

Reviewed what support was in place to support transition in other areas.

• QI methodology to structure our work and track the impact of changes on Transition process development.

• We are testing ideas with 4 PDSA ramps in progress and a fifth planned

• Developed networks with partners across our ICB area.

• Engaged with parents, carers and families through a number of focus groups. We started work in 2022, with the majority of the work being led by one of the Specialist nurses. As we go into 2023, the work is evolving. Sustaining our gains is critical as we move into the next phase of this work. This includes refining new processes which were set up to address gaps in provision (using PDSAs) as well as ensuring full implementation of the approach across the Complex Care Nursing team.

Results

We’ve learned from others to develop our pathway based on good practice.

Lessons learned & next steps

• Keep an open mind – our work has taken a number of new turns since we started!

• We will now test some new processes with colleagues in other teams and disciplines. Our young people receive services from a lot of different agencies – therefore our improvement work needs to cross those boundaries.

• We’ve updated our driver diagram as we learned more new change ideas emerged.

QI allowed us to focus on those smaller patient groups that we were most concerned about. We were able to direct work where it was needed rather than a whole case load approach.

QI helps you to track progress. It is helpful to take stock every now and then and review progress overall, and not just in individual PDSA cycles.

Our patient groups are small, so it can take time to see the full impact of our changes. We’re happy to be patient and see things through.

References

1. ‘Transitions from child to adult health care for young people with intellectual disabilities: A systematic review’, Brown, M. et al. Jan 2019

2.‘Stepping up - A guide to enabling a good transition to adulthood for young people with life-limiting and life-threatening conditions’ , Together for Short Lives. April 2015

Feedback from our stakeholders

V. Kopanitsa1, S. Flavell , S. Candfield2, U. Srirangalingm2, L. Waters2

1. University College London (UCL) Medical School;

2. Central and North West London NHS Foundation Trust

V. Kopanitsa1, S. Flavell , S. Candfield2, U. Srirangalingm2, L. Waters2

1. University College London (UCL) Medical School;

2. Central and North West London NHS Foundation Trust

Deprescribing Polypharmacy: Precision over Pills

Introduction

Polypharmacy is the use of multiple medications by an individual to manage various medical conditions Although sometimes necessary, this practice can lead to serious health complications This state is prevalent among older adults as the incidence and cooccurrence of chronic diseases tend to rise, resulting in increased medication usage1 Polypharmacy carries several potential risks such as adverse drug reactions, drug interactions, and significantly increases incidence of fall1

Anticholinergic Burden

Anticholinergic drugs block action of neurotransmitter acetylcholine in central and peripheral nervous systems2 The long-term use of these medications can have a cumulative effect, leading to cognitive and physical impairment that contributes to a person's overall ‘burden’ Several types of medications, including antihistamines, antidepressants, and antipsychotics, can have varying levels of anticholinergic activity2 Each medication that displays such activity is assigned an Anticholinergic Burden Score (ACB), with a higher score indicating greater burden Clinicians should regularly review these medicines to optimise therapies and promote healthy ageing2.

Ø Failure to address this issue can result in frequent hospitalisations and higher mortality approach to medication

Ø This achieve better health polypharmacy

Summary

Ø Prolonged use of anticholinergics can impair cognitive and physical function Using drugs with ACB scores of 3 or more for over 6 years increases dementia risk by 46%3

Ø Targeted medication reviews have demonstrated the ability of clinical pharmacists in general practice settings to effectively reduce the potential for iatrogenic harm

Ø A significant decrease in the total ACB score by 57 points within cohort, results in a substantial reduction of the risk of falls and dementia in these patients

0 3 6 9 12 15 18 21 24 27 Reduced Medication Dose Stopped Medication No Change in Medication Reduced Medication Dose Stopped Medication No Change in Medication Number of patients ACB score in patients on initial intervention relative to final outcome ACB Score 0 ACB Score 1 ACB Score 2 ACB Score 3 ACB Score 4 ACB Score 5 Final Outcome Initial Intervention ACB Score 6 ACB Score 7 ACB Score 8 ACB Score 9 3 5 4 4 4 7 5 4 1 1 1 1 1 1 6 5 3 4 2 1 1 1 1 2 5 8 4 4 1 1 1 16 22 8 20 20 6

Figure 3: A targeted medication review was conducted for suitable patients with high ACB scores, followed by one-month assessment of tolerance The review resulted in a significant proportion of patients reducing or stopping targeted medication, while some interventions were not well-tolerated, resulting in higher overall ACB scores The final result was positive, with an increase in total number of patients with ACB scores of 0 Some patients who reduced their dosage were able to stop taking medication altogether, resulting in lower ACB scores However, patients who were unable to tolerate the reduction continued with their regular treatment, leading to higher ACB scores within cohort

Figure 1:

Methodology

Ø A

patients' medication lists with highest ACB therapy Ø A deprescribing Findings

Influential Factors for Non-Intervention within Cohort

5%

10%

25% 20%

Justifications for non-intervention within cohort n = 20

-5 -4 -3 -2 -1 0 +1 +2 +3 0 3 6 9 12 15 18 21 24 27 30 0 1 16 2 1 26 0 0 0 Change in ACB Score Number of patients Change in ACB Score from before and after medication review

Figure 4: The impact of targeted medication reviews on preventing polypharmacy and reducing associated risks was evident Out of 46 reviews, 16 patients reduced their ACB score by 3 points, resulting in a 48-point reduction within cohort Two patients reduced their score by 2 points, leading to a 4-point reduction within cohort One patient reduced their score by 4 points, and another by 1 point, leading to a total point reduction of 57 points Although most patients had no change in ACB score, reducing dosage by 50-75% significantly minimises patients' exposure to treatment and thereby, reducing associated risks Above all, the final outcome showed either a reduction or no change in ACB scores indicating a positive result in maintaining or significantly reducing patients’ overall risk

Background

Midwives’ experiences of participation in a national quality

improvement intervention:

Lessons from scaling PReCePT (Prevention of cerebral palsy in pre-term labour)

• Antenatal magnesium sulfate (MgSO4) therapy given to women at risk of preterm birth reduces the combined risk of infant death or cerebral palsy. It is a recommended intervention by the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE)

• The PReCePT Quality Improvement (QI) intervention was implemented by champion midwives in all maternity units in England and was found to be effective and cost effective in improving adherence to MgSO4 guidance [1]

The problem

Social impacts of QI interventions, e.g. staff wellbeing, are not routinely captured, but can impact on sustainability

Outcome

Being a midwife champion had an impact on work related wellbeing

If you’ve got fire in your belly then you bring that back to the workplace (P16 )

What we learned

I really enjoyed doing it and I'm really glad that I went for it […] It's really got my confidence up (P17)

Elements of the intervention, characteristics of the organisation, and the perinatal team, impacted on champions’ work-related wellbeing

1. Champions believed in PReCePT’s role in improving care. There was a lot of commitment and enthusiasm to make it a success. Mentoring, co-creating learning, and being part of a community of practice enhanced self-efficacy, confidence, and led to more career opportunities

2. Support from the organisation through backfill funding, access to resources, and clinical managers and matrons allowing champions time off clinical duties, helped champions feel recognised, supported and committed

3. Champions in settings where PReCePT was a perinatal team intention, described improved team competencies , felt pride in collective achievement, and improved morale and job satisfaction

Midwives [ ] should be given more opportunity to be involved in this because it does give you a really good background and it gives you the confidence to deliver care (P15)

What did we do?

Qualitative process evaluations of the National PReCePT Programme, and the PReCePT Randomised Control Trial (PReCePT Study)

What were champion midwives’ views and experiences of implementing PReCePT?

How did we do it?

Semi-structured telephone interviews with 22 midwife champions from enhanced & standard support units Interviews were audio-recorded & transcribed with consent

• Analysis using the framework approach [3] and informed by the Normalisation Process Theory [4]

Conclusions

• Allowing opportunities for midwives on the ground to take more active roles in QI, and making QI a collective cross-disciplinary endeavor, can have an impact on staff wellbeing, and built improvement capability within the organization

• Job satisfaction and improvement capability are crucial for improving quality of care and retaining staff. Adequate backfill funding for champions and organisational support for QI activities are essential for achieving maximum impact

I had really good support from my matron and the lead for the labour ward, everyone was very supportive […] I'm quite lucky at the unit, everyone is very keen to learn new things […] So for me, it was a really good experience (P17)

A Quality Improvement project on the Importance of adherence to ESC guidelines for LV function assessment after STEMI

QIP

Scale of the problem:

• Severe Left Ventricular (LV) dysfunction is the strongest prognostic indicator and carries a high mortality risk.(1) (2)

• ESC Guidelines state "after acute myocardial infarction, both in stable patients and those on optimized heart failure medications, left ventricular ejection fraction should be measured again at 6 -12 weeks to evaluate need for implantation of primary preventive defibrillator ". (3)

• Patients with severe LV dysfunction following myocardial infarctions were being lost to followup.

Figures

Learning Points

Ideas tested/ discussed:

1. Incorporating LV reassessment in discharge summary – cumbersome and complicated.

2. Highlighting need on inpatient echo report – increased workload on echo department.

3. Junior doctor training and ward nurse input-junior doctor rotations pose a challenge.

4. Involvement of Heart Failure team.

Changes implemented:

• The first cycle of the QIP showed that there were no plans in place to reassess LV function in 57% of these vulnerable patients.

What did we aim to accomplish?

• Rectify deficiency and implement a robust, self-sustaining mechanism to identify these vulnerable patients.

• Appropriately screen patients for defibrillator implantation and thus improve patient safety.

How we planned to do this:

• Education and awareness: Junior doctor teaching sessions, CME discussions and posters to emphasize importance of LV function surveillance.

• Team-work: Seek the involvement of other teams such as specialist heart failure nurses and CCU.

What did we achieve?

• The second cycle found that 100% patients were appropriately referred to the HF teams and had OP echo requests for surveillance.

• Enhanced patient safety outcomes.

1. Posters: improved awareness among doctors and nurses.

2. HFN referral: Appropriate initiation of HF foundational therapy and an automatic referral for device therapy, if appropriate.

Reflections and ongoing vigilance:

1. This QIP showed us the importance of being aware of national and international standards of care.

2. The changes implemented were successful primarily due to excellent communication and teamwork.

3. We have planned ongoing surveillance with further cycles.

Take home messages:

1. LV function remains the strongest prognostic indicator after myocardial infarctions.

2. LVSD tends to improve with time and HF medications, but ongoing surveillance is mandatory.

3. Education, awareness, good communication and teamwork can improve patient safety outcomes.

Authors : Dr. Ashish Amladi, Dr. Kyar Chi Kyaw Win, Dr. Vikram Ajit Rajan Thirupathirajan, Dr. Amit Taneja, Dr. Girish Viswanathan

Authors : Dr. Ashish Amladi, Dr. Kyar Chi Kyaw Win, Dr. Vikram Ajit Rajan Thirupathirajan, Dr. Amit Taneja, Dr. Girish Viswanathan

Weekend Handover

Understanding the Problem

1 1 Junior Doctors in Bronglais General Hospital identified that the weekend medical handover had difficulties: no protected time, no designated place for handover, no senior involvement, multiple paper lists, two separate handovers This was impacting negatively on the Juniors’ wellbeing and patient safety

1 2 The project aimed to focus on making weekend handover safer and more efficient

1.3 A fishbone and process map were used to help understand the problem and identify positionality of work.

SMART Aim

4 1 75% of weekend medical handovers to happen in a designated place and time with the entire on-call team present within three months, measured by using time keeping and survey, to improve patient safety and junior doctors’ well-being

PDSA Ramp

5.1 Continuation of discussions among the Junior Doctors, members of QIP team surveyed and shadowing the F1 on call for data gathering Involving rest of stakeholders in gathering informal feedback

5 2

Stakeholders

2 1 We identified our stakeholders by exploring Junior Doctors’ opinions and concerns We involved Medical Education and liaised with the QI team at BGH After discussion with juniors, we involved the medical consultants and the management team

2.2 All foundation doctors at Bronglais General Hospital are involved in the development of the project

2.3 The project falls within the engagement and involving people stage of the Ladder of Co-production

Measures

3 1 Outcome - Number of handovers in designated place and time at handover taken

3 2 Process measure(s) – Attendees, issues identified, and time taken

3.3 Balance measure – Staff well-being (post-handover and postweekend surveys)

PDSA 1: Specific time and place

PDSA 2: Handover training

PDSA 3: Use of Teams channel for handover

PDSA 4: MAU team engagement

PDSA 5: Dedicated safe space and time

5.3 Adapt:

• Access to quiet/protected space is essential, as well as more time allocated to the handover Junior doctors felt a significant improvement in their sense of wellbeing with a Senior Doctor present to help clarify and prioritise jobs

• There will be a need to digitalise the system

• Standardisation of handover:

o Unified weekend jobs list with prioritisation of jobs

o Standardisation of priorities for an easy navigation of said list e g a colour coding system

o A standardised Friday ward round template sheet for each medical ward/team to add to the patient's notes, which will allow the on-call doctors seeing a patient for the first time to have a quick overview of the case

Reflection and next steps

6.1

Evaluation of Improvement Collaborative

Geetika Singh, Alison Butler and Simon Edwards

Background

Leading health systems have invested in substantial quality improvement (QI) capacity building, but little is known about the aggregate effect of these investments at the health system level

Collaborative learning is one of the educational approaches of using groups to enhance learning through working together Research shows that collaborative experiences that are active, social, contextual, engaging and student-owned leads to deeper learning

Aims

❑ To design, develop, implement and evaluate a collaborative learning system that brings together different teams/services together to seek improvement.

❑ To evaluate the aggregate effect of collaborative learning across the health system level.

Approach Outcomes

A short-term (12-month) virtual programme, called Improvement Practicum, was designed to support 24 teams in planning, delivering and sustaining improvements on Central and North West London NHS Foundation Trust's four strategic priority areas (violence reduction, reducing pressure ulcers, improving flow and improving safety) 90 staff, service users and carers were enrolled

The collaborative provided knowledge of the QI Model for Improvement and various co-production methodologies, with an ambition to enable frontline ownership of safety solutions while building organisational QI capacity and capability

All improvement teams were assigned a QI Sponsor and Improvement Coach

Figure1 outlines the practicum programme approach The 12-month programme was divided into two phases: Planning and Delivery The planning phase covered the theme/topic selection, recruitment of training faculty, establishing governance structure and enrolling project teams The delivery phase had four learnings sessions, six workshops and a celebration event There were action periods (periods between learning sessions and workshops) where teams applied learning into their projects

Hard Benefits

Conclusion and Lessons Learnt

CNWL Trust covers a large geographical area (London, Milton Keynes, Surrey and beyond). Thus, the Practicum brought cognitive diversity to the learning by bringing different services/teams, staff and SU&C together to drive improvement.

The benefits of improvement work lie beyond the project data. Positive unintended consequences, such as a shift in team culture and adoption of an improvement mindset, gained on their journey should also be evaluated and celebrated.

Furthermore, collaboration helped to create a culture/platform for sharing and spreading learning beyond the team/service.

Soft Benefits – Value Added

The soft, unintended benefits are equally vital to capture Designed a framework for evaluating staff perceived added value from QI These were:

• Improved staff experience/well -being, team cohesiveness and cross-boundary working

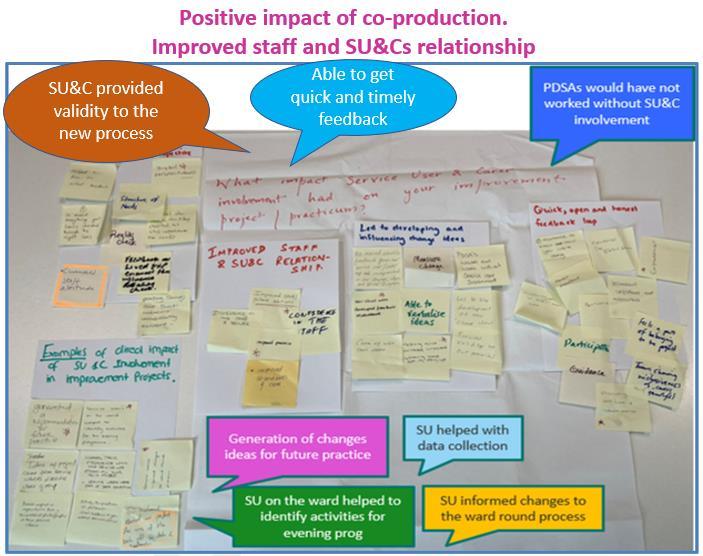

• Positive impact of co -production. Improved staff and SU&Cs relationship

• Streamlined processes & improved efficiencies

• 59% teams shared their work internally or externally

Acknowledgement to all Contributors

CNWL Improvement Academy (IA) is deeply grateful to all those who played a role in the success of the Improvement Practicum Project Thank you to - Dr Con Kelly, Peter Toohey, Bridget Browne, Peter Smith, Vernanda Julien, Sarah McAllister, members of IA faculty, ServiceUsers, Carers and staff from all 24participating teams - for their invaluableinput and support throughout theprocess Theirinsights andexpertise were instrumental inshaping the direction of thisproject