Photo © Tamás Réthey-Prikkel, Attila Nagy, János Posztós, Gábor Kotschy, Zsófia Pályi

Photo © Tamás Réthey-Prikkel, Attila Nagy, János Posztós, Gábor Kotschy, Zsófia Pályi

Müpa Budapest is supported by the Ministry of Human Capacities Corporate partners: IENCE! respect. mupa.hu supported by the Ministry of Culture and Innovation EXPER In every

DEAR MUSIC LOVERS,

Fully 254 years after his birth, Ludwig van Beethoven’s piano œuvre remains a glorious and deeply complex puzzle, a wide plain onto which I escape every day to take in new perspectives. When I look at my career in Beethoven’s mirror – and this makes sense as he represents the centre of my musical thinking – I first and foremost observe the gain in liberty that I have acquired through studying his life and work.

Of course, Beethoven intended his piano concertos primarily for successful performances in the so-called 'Akademien'. Up until the fourth piano concerto, he performed there himself as soloist. A review of his performance of the Third Concerto particularly amuses me: ‘Less felicitous was the following Concerto in C minor, that Mr v. B., usually known as an exquisite piano player, couldn’t perform in a satisfactory manner for the audience.’ It is reassuring that Beethoven did not allow himself to be put off by such critical voices and continued to inspire the Viennese public.

It is striking, however, that Beethoven refrained from tackling another work in this genre in the 19 years he lived after completing his fifth piano concerto. Might it be that he simply saw this form – in competition with the symphony – as no longer a suitable vehicle for his own revolutionary ideal of sound? From then on, Beethoven preferred to apply his uncompromising radicalism to his string quartets, the later sonatas or piano works such as the Diabelli Variations. The late works for solo piano remained largely unplayable for the majority of

Viennese amateur musicians, and for a long time were avoided even on professional concert stages.

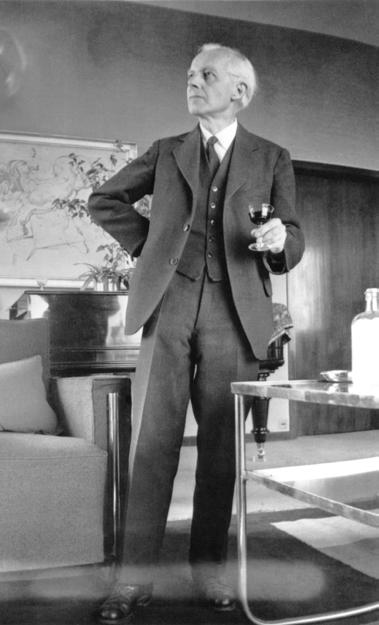

Béla Bartók likewise pushed the boundaries and further developed the piano as a solo instrument, endowing it with new timbres and percussive elements. Bartók himself was an outstanding pianist for whom I have great admiration. My private music collection contains all of his piano works – everything he wrote for our instrument. I also own an original handwritten letter by the composer, which is a great inspiration for me.

Next to it, on my grand piano at home in Vienna, is a bust of Beethoven. Whenever I sit at the piano, I look at this man who is so close to me – his fierce gaze, his wild hair and his curious eyes – and silently thank him for listening to me for so long and for understanding my trials and tribulations as I drift through his work. Beethoven's music has accompanied me throughout my life. It can hardly be a coincidence that his fifth piano concerto was on the programme at my debut in Budapest, at the Liszt Academy March 1976, with the Hungarian National Philharmonic Orchestra under the direction of Gyula Borbély.

I look forward to meeting you, dear Festival Audience, and to our journey through Beethoven's piano concertos with the Hungarian National Philharmonic Orchestra at this year's Bartók Spring International Arts Weeks.

Rudolf Buchbinder

Photo: Marco Borggreve

2

Photo: Marco Borggreve

the Music Herself Hope Will Never Disappear Interview with Pál Frenák 37 The Editor Recommends 32 34 ‘Nothing Can Give Us a Better Sense of Togetherness than Music’ Interview with Elli Jaffe 42 ‘I Really Came into My Own in Jazz’ Interview with Júlia Karosi 28 ‘Music Is a Powerful Religion’ Interview with Tan Dun The Essence of Bartók in 10 Movements 07 The Editor Recommends 18 Just Read! 25 08 Barefoot Beauty

Barbara Hannigan,

A Passionate European The world of Till Brönner 20 Ryoji Ikeda and the Art of Data 16 ‘Can We Help It if the Best Photographs Seem Consistently to Be Produced by Hungarians?’ Hungarian Photographers in America (1914–1989) 40 12

Barbara Hannigan

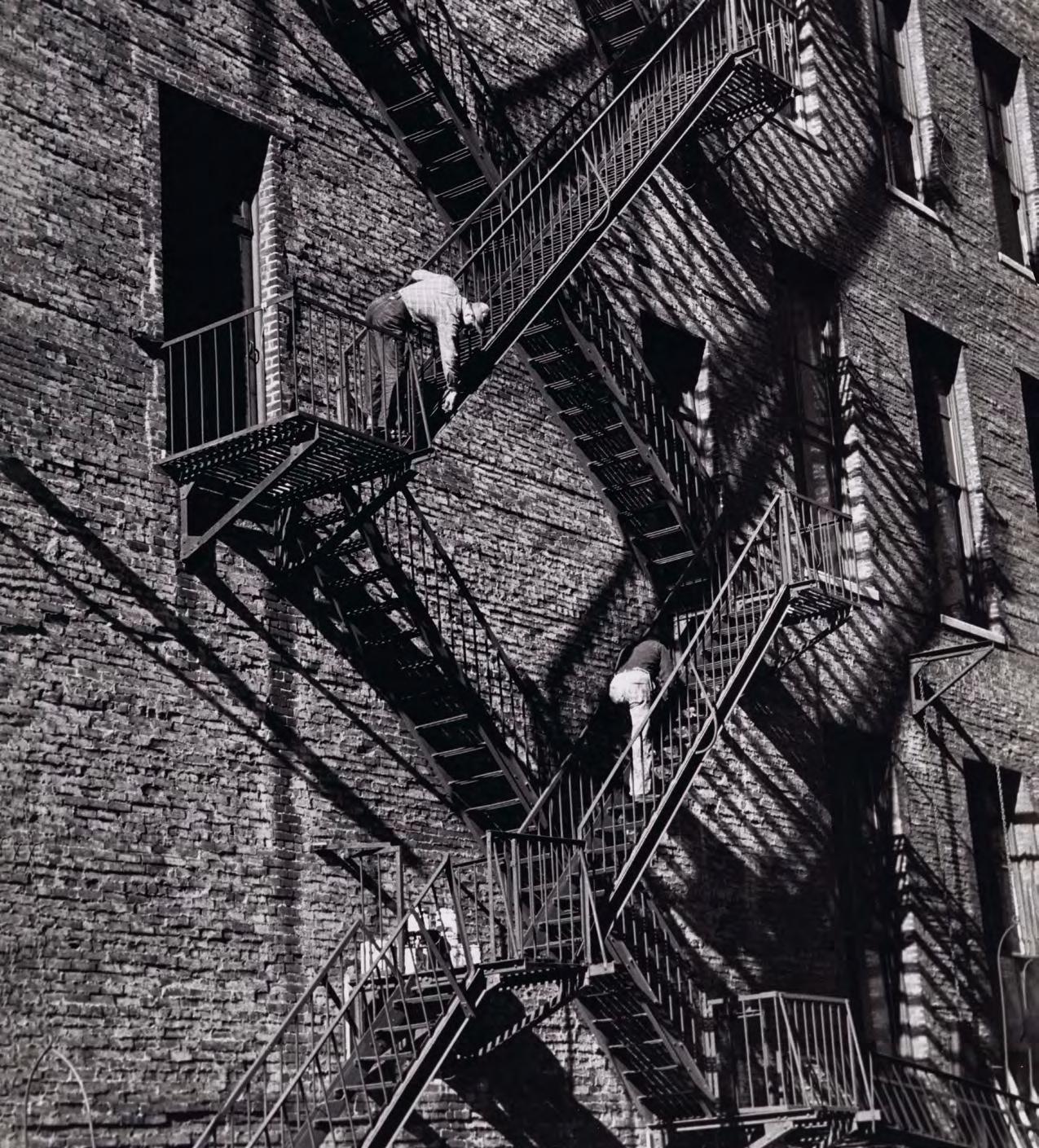

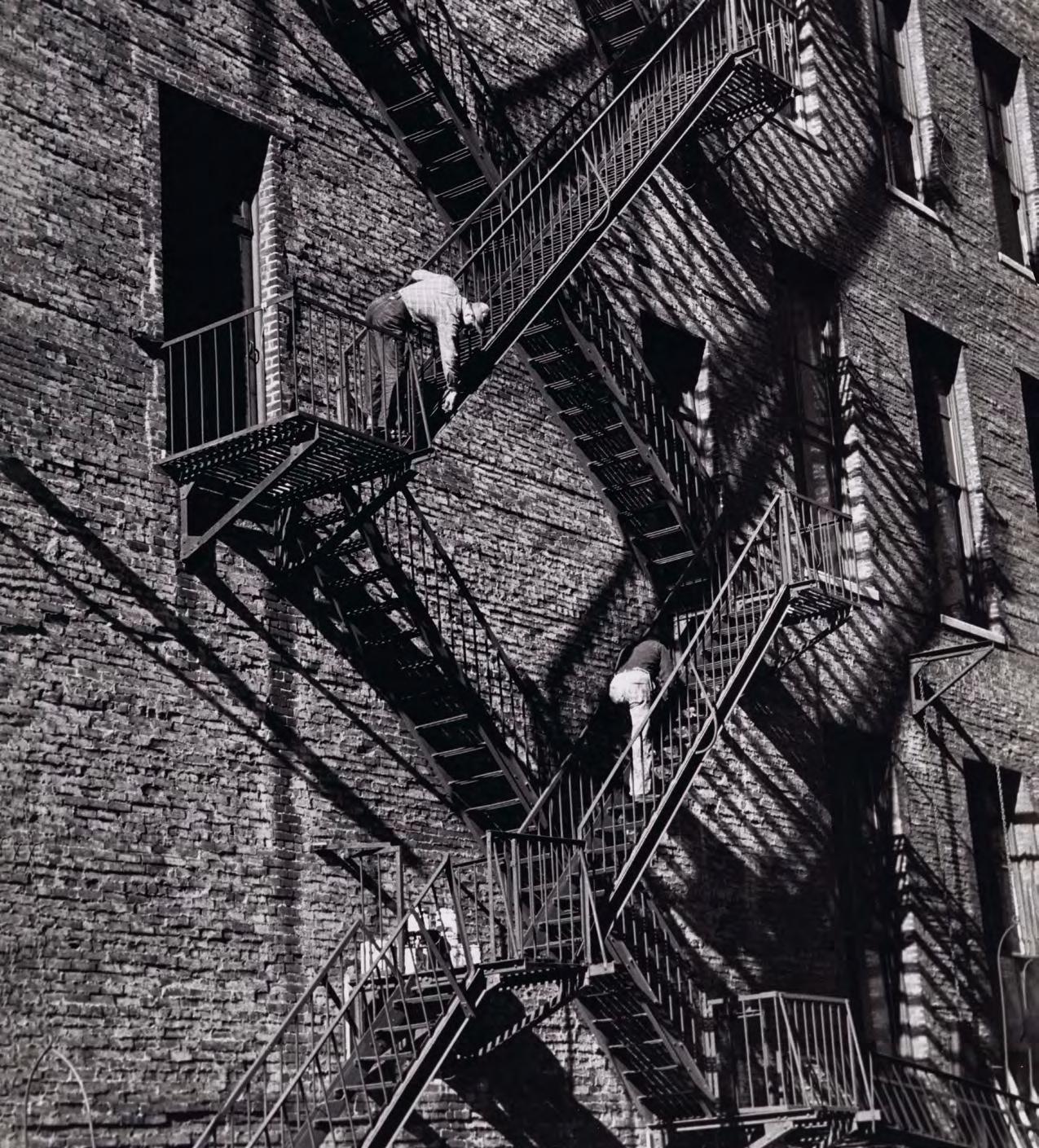

3 06 04 –25 08 2024 Kertész Moholy-Nagy Capa... HUNGARIAN PHOTOGRAPHERS IN AMERICA (1914–1989) Fire Escape, New York, 1949, André Kertész | Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, Adolph D. and Wilkins C. Williams Fund mfab.hu Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest Main Sponsor: Major Sponsor: Media Sponsors: Partner: Co-operating partners: Organized by the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in association with the MFAB

NATIONAL DANCE THEATRE

1024 Budapest, Kis Rókus utca 16–20.

TOLDI CINEMA

1054 Budapest, Bajcsy-Zsilinszky út 36–38.

HUNGARIAN

NATIONAL GALLERY

1014 Budapest, Szent György tér 2.

AKVÁRIUM KLUB

1051 Budapest, Erzsébet tér 12.

LISZT ACADEMY

1061 Budapest, Liszt Ferenc tér 8.

MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS

1146 Budapest, Dózsa György út 41.

HOUSE OF MUSIC HUNGARY

1146 Budapest, Olof Palme sétány 3.

MOMKULT

1124 Budapest, Csörsz utca 18.

BUDAPEST MUSIC CENTER

1093 Budapest, Mátyás utca 8.

SZIMPLA KERT

1075 Budapest, Kazinczy utca 14. ERKEL THEATRE

1087 Budapest, II. János Pál pápa tér 30.

MÜPA BUDAPEST

1095 Budapest, Komor Marcell utca 1.

LUDWIG MUSEUM

– MUSEUM OF CONTEMPORARY ART

1095 Budapest, Komor Marcell utca 1.

4

DANCE 05 and 06. 04 Les Ballets de Monte-Carlo: Cinderella 06 and 07. 04 Danube Art Ensemble: Székely Gate 10 and 11. 04 FrenÁk Company: CrAzy_RunnErs / Parad_Is_E JAZZ 05. 04 Júlia Karosi | Ingrid Jensen | Kristjan Randalu 08. 04 Samara Joy CLASSICAL MUSIC 06 and 07. 04 Rudolf Buchbinder and the Hungarian National Philharmonic Orchestra 08. 04 József Balog’s Piano Recital 11. 04 Song of Songs 14. 04 Tan Dun: Buddha Passion POPULAR MUSIC 06. 04 Ryoji Ikeda: Ultratronics 07. 04 Spiritualized WORLD MUSIC 09. 04 Pure Source 11–13. 04 Budapest Ritmo LITERATURE 11. 04 Day of Hungarian Poetry FILM 12–13. 04 Budapest Ritmo Film Programme EXHIBITION 05. 04– Kertész, Moholy-Nagy, Capa... Hungarian Photographers in America (1914–1989) 09. 04– When Dolls Speak The Art of Margit Anna (1913–1991) 14. 04– Till Brönner: Identity – Landscape Europe CROSSOVER 08. 04 Söndörgő | Kelemen Quartet 10. 04 Electric Fields 5

PROGRAMMES BY GENRE

THE ESSENCE OF BARTÓK IN TEN MOVEMENTS

TEN THINGS YOU SHOULD KNOW ABOUT BÉLA BARTÓK

From the age of three months, after a smallpox vaccination, Bartók’s entire body was covered with a rash, which lasted for years. Because of his protracted illness, he was over two years old by the time he started to talk.

Thanks to his parents, Bartók was exposed to music early on. His father played the cello, while his mother was a piano teacher and his first tutor.

Bartók was nine when he wrote his first compositions. He made his debut as a performer and composer at the age of eleven, with The Course of the Danube

The symphonic poem Kossuth, Bartók’s first major work, premiered in Hungary and abroad in 1904. In his review in Zenevilág, Pongrác Kacsóh wrote: ‘Béla Bartók is a prodigious, first-rate talent, a brilliant musical genius, the direct heir to the symphonic talent of Ferenc Liszt – the first pure Hungarian symphonic composer.’

The year to have the greatest impact on Bartók’s career was 1905, when he became friends with Zoltán Kodály, and the two would go on to visit villages in Hungary collecting folk songs. Bartók’s great innovation was to compose new music that sounded like folk music, rather than to arrange folk songs. The pinnacle of this concept is Bluebeard’s Castle (1911), a one-act opera that his peers initially considered unplayable.

Kodály wrote of Bartók: ‘Every time a work of his is performed, they think of Hungary for a minute, if not more, and they think it can be no mean country where such things are created.’

Bartók’s second work for the stage, The Wooden Prince (1917), was an unmitigated success; its premiere brought world renown to Bartók as both performer and composer.

According to his son Péter, Bartók called the Liszt Academy – where he taught for years – an ‘unpleasant

place.’ This was because he did not really like to teach ‘beginners’, feeling that it took time away from collecting folk music. Regardless, both of his wives – Márta Ziegler (1909) and Ditta Pásztory (1923) – were his students. Each gave birth to a son: Béla Jr. and Péter, respectively.

The two events that finally made Bartók choose emigration were the outbreak of the Second World War and the death of his beloved mother. He continued his study of folk music as an honorary doctor of Columbia University, notating and studying a collection of Southern Slav folk music. He never applied for American citizenship, retaining Hungarian nationality until his death.

Several public spaces and institutions are named after Bartók, including Müpa Budapest’s National Concert Hall. He has been featured in the Google logo and on the 1,000-forint banknote that was in circulation between 1983 and 1999. The portrait used on the latter was modelled on his son, Béla, an engineer.

7

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

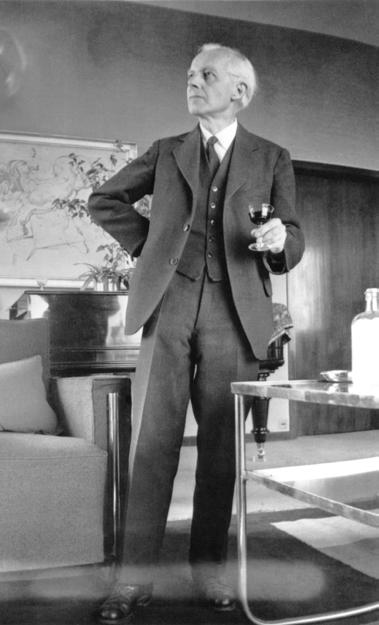

Béla Bartók with Zoltán Kodály and members of the Waldbauer–Kerpely String Quartet in March 1910

Photo: Aladár Székely

Béla Bartók after the world premiere of Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta in Basel, on 21 January 1937

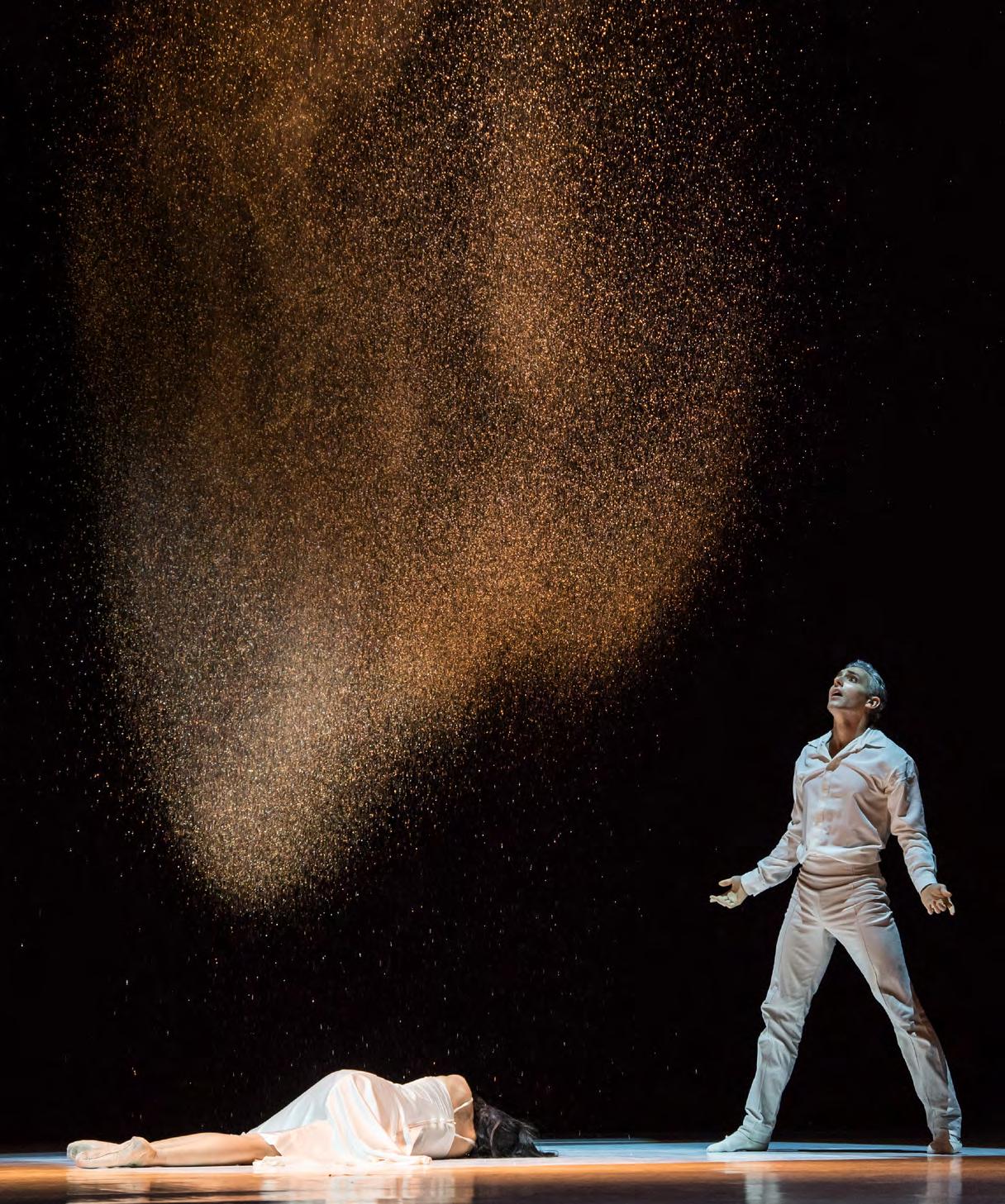

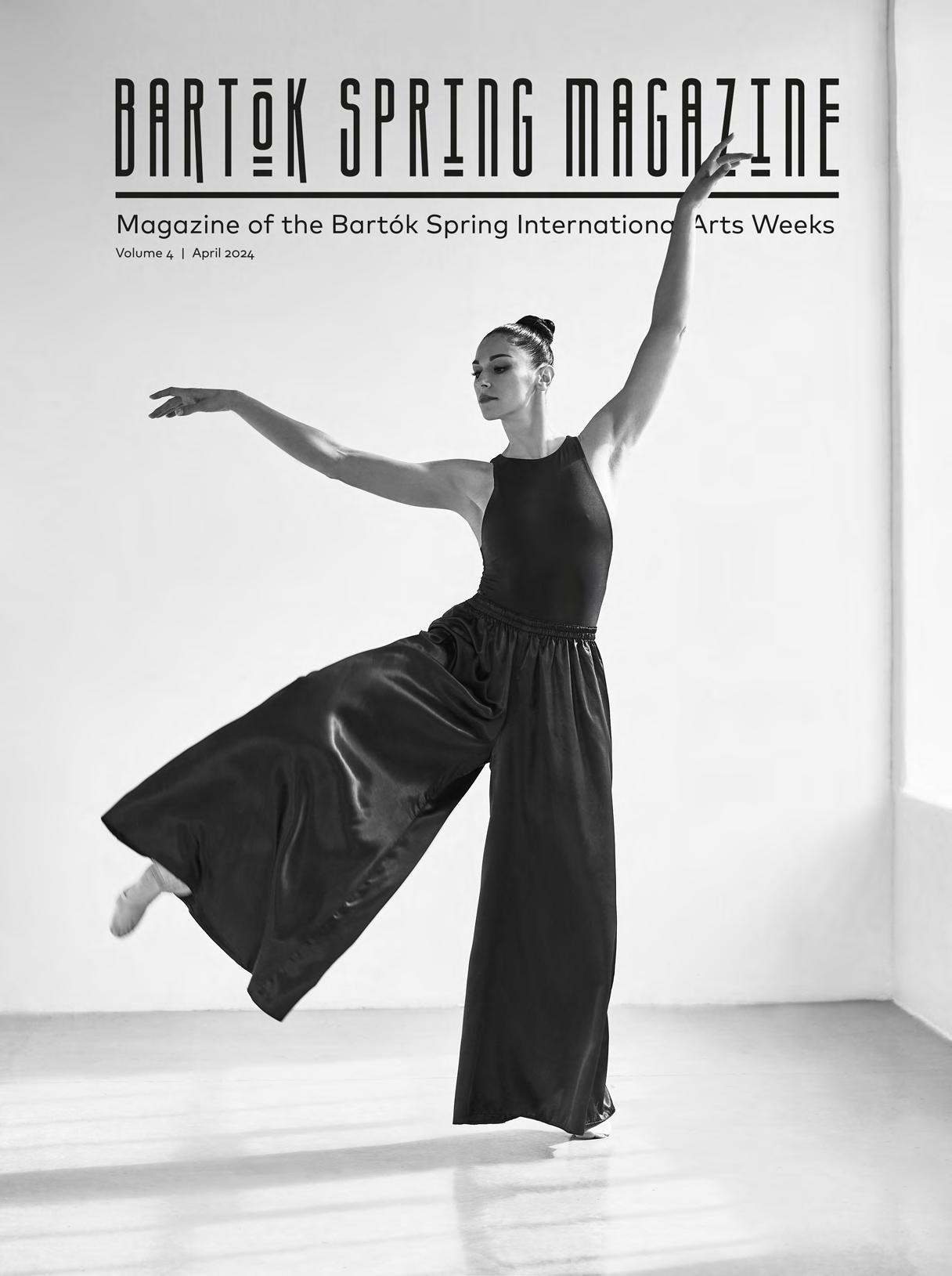

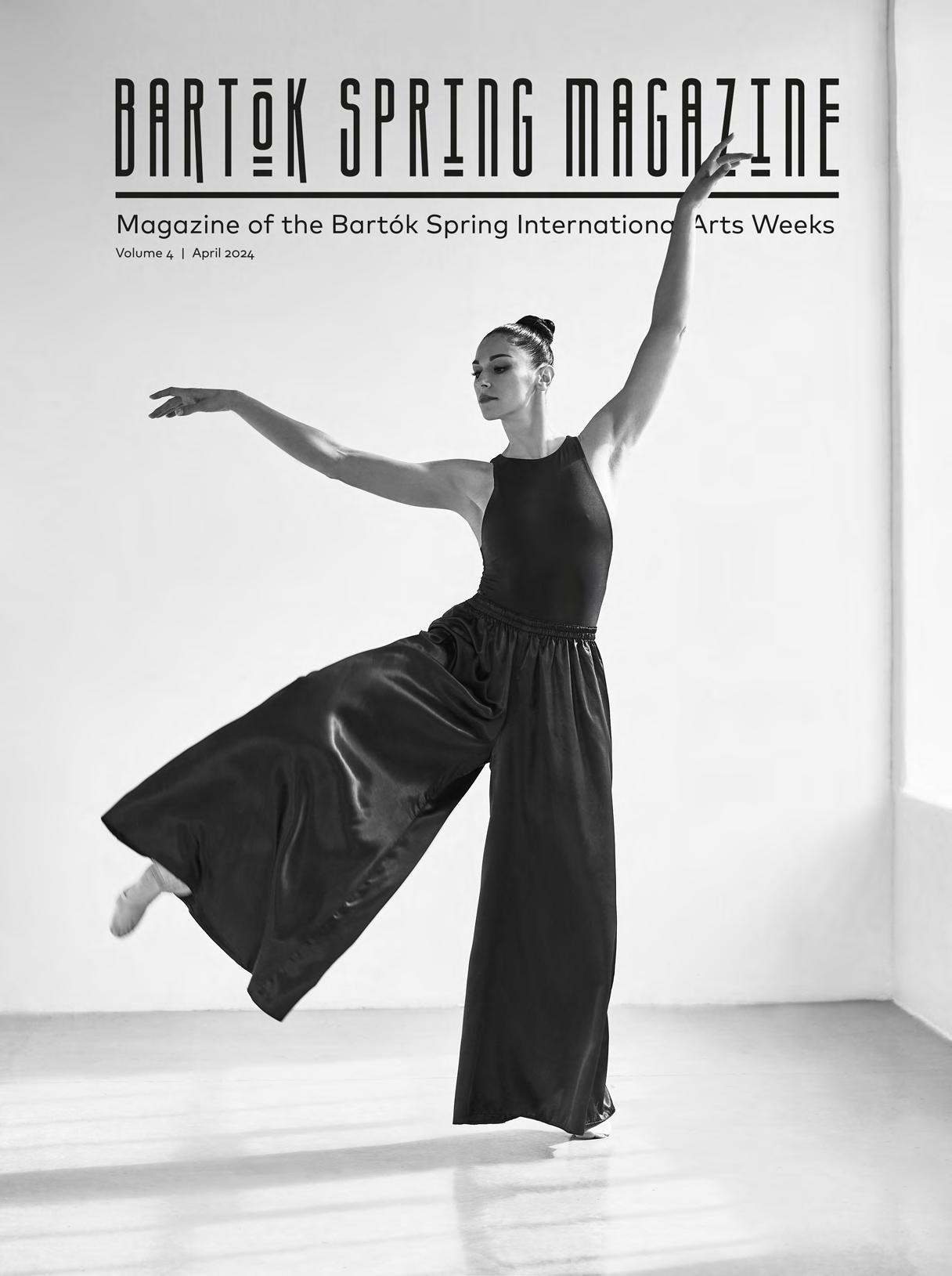

BAREFOOT BEAUTY

by Tamás Jászay

Home to the rich and beautiful, a district of one of the world’s most densely populated independent city-states, with a casino as its top tourist attraction and a Formula 1 race driven along its steeply winding streets, on what is arguably the most dangerous track of all. We’re talking about Monte Carlo, of course, whose seductions also include Les Ballets de Monte-Carlo, as the audience of the Bartók Spring will now discover.

Although the current company was founded in 1985 by Princess Caroline of Monaco, the continent’s mini-capital of luxury and glamour has enjoyed close ties to perhaps the most aristocratic of the performing arts, classical ballet, for much longer. A relatively well-known episode in this long story is the case of Sergei Diaghilev, during whose tenure of the legendary Ballets Russes – from its 1909 Paris debut until his death two decades later – Monte Carlo became the company’s intellectual and creative base.

This gallant opportunity for reinvigoration should be understood broadly: sources confirm that generations of dancers have found a relaxing retreat in Monte Carlo, the realm of sparkling sea and permanent sunshine. The location is ideal in every respect, with the proximity of the French–Italian border guaranteeing an everrenewing, pulsating international vibe that remains a feature of the art of dance to this day.

What Diaghilev and his company actually did was to rejuvenate and elevate an existing tradition, which is worth noting as today’s Les Ballets de Monte-Carlo is rooted in this same mindset. It became clear from the outset that the magnates and celebrities visiting the casino, which opened at the end of the 19th century and quickly became the city’s trademark, needed entertainment in their leisure time. Flush with capital, the enterprise started to sign major stars early on: we can only imagine the experience of seeing Tamara Karsavina and Vaslav Nijinsky on stage together in 1911.

A COMPANY IS (RE)BORN

Following Diaghilev’s death in 1929, several choreographers sought to carry the torch onward, and companies of varying size would operate under the brand in ensuing decades. One such group, while touring America, was seen in Philadelphia by a little girl who fell in love with ballet forever, though she herself was to find world renown on the silver screen.

9

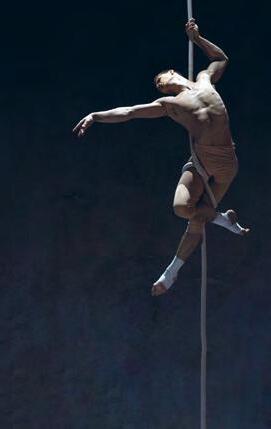

Photo: Alice Blangero

This is where the threads of the story connect: after her dream wedding in 1956, Grace Kelly became Princess Grace of Monaco and made cultural patronage a mission of her life. In 1985, three years after her death, her daughter Caroline founded Les Ballets de Monte-Carlo, whose first directors continued with the established tradition of the Ballets Russes.

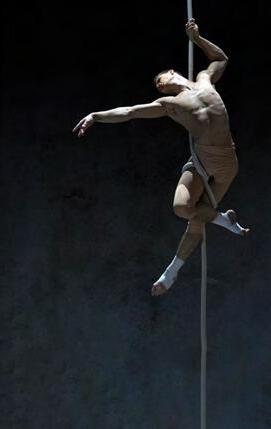

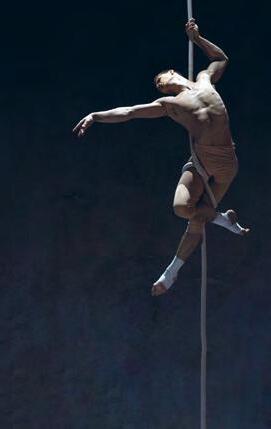

Director and choreographer Jean-Christophe Maillot, who was appointed in 1993, envisaged new directions for the growing company, with its steadily increasing international name and reputation. The promising ballet dancing career of Maillot, who was born into a family of artists in 1960, was shattered early on by a serious injury, forcing him to find a new vocation as a choreographer, educator and company manager. He made his debut as a choreographer in Monte Carlo in 1987, with a hugely successful production of The Miraculous Mandarin

The rest is history: today Les Ballets de MonteCarlo is a thriving business and successful artistic enterprise. The company, which has fifty dancers, is a regular guest of the world’s leading opera houses and prestigious festivals. Much of its substantial repertoire has been choreographed by the prolific Maillot, who as company director also makes sure his troupe has the opportunity to work with international dance luminaries such as Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui, Emio Greco, Chris Haring, Lucinda Childs, William Forsythe and Marie Chouinard.

MAILLOT, THE BRAND

On the subject of teamwork, Jean-Christophe Maillot has this to say about the importance of the company: ‘There needs to be a connection with the people I work with. That’s why I’m not a choreographer who can go to various companies and create works for them to perform. Relationships come before choreography; it’s who you work with that is important for me.’ His works delight the contemporary eye and mind, drawing on the most diverse sources: they are eclectic, in the positive sense of the word. Through classical ballet, modern and contemporary dance, theatre, circus and drama, the past and the present of dance enter into a dialogue on Maillot’s stage.

‘I try not to take myself too seriously; humility is a necessity. There are always doubts, fears and blockages. Life for me is to conceive, to give a vision of how dance should be perceived and remain constantly interested,’ he said in an interview a few years ago.

Maillot is known in dance circles for his knack of discovering new sides to old stories that have become hackneyed on the stage, and to bring them closer to the minds and hearts of today’s audiences. While convinced that classical ballet is truly magical, he readily admits that it is impossible to stage the classics today as they were fifty or one hundred years ago. As a creator, he has spent decades reimagining the core pieces of the ballet canon: rather than aiming to shock, his radical readings intend to lay bare layers of thought that have become forgotten or obscured. ‘I don’t know about the audience,’ he says with appealing candour. ‘I leave them free to experience the performance; I don’t try to keep their attention. I create ballets for people who don’t know dance.’

One of the first, French-language reviews of his Cinderella, which had its premiere on 3 April 1999, offered a succinct summary of the art of the director and choreographer: ‘There is a "Maillot style", modern, fluid and minimalist, without any aggressiveness, dream-like.’

A TALE RETOLD

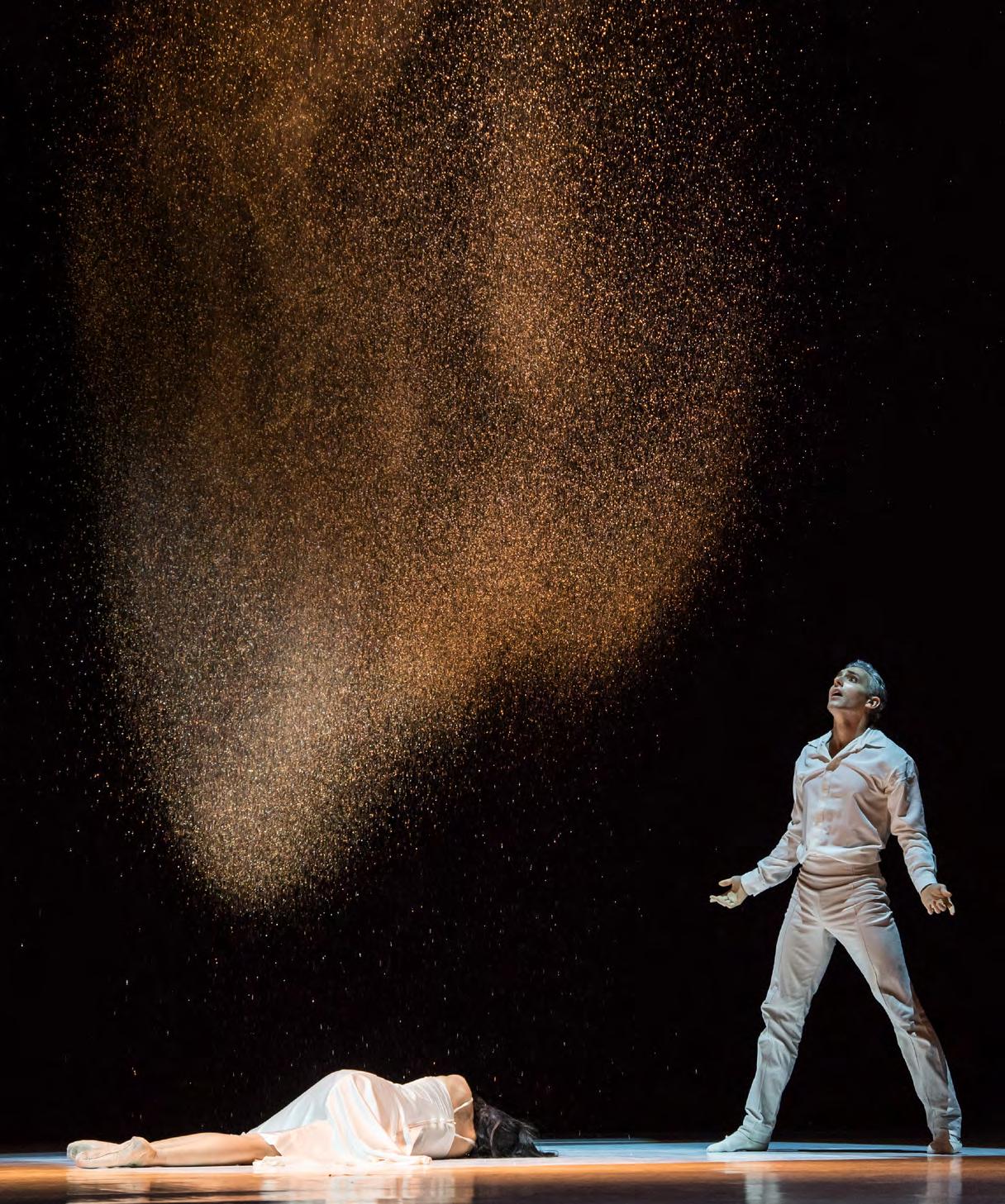

Taking Charles Perrault’s classic tale of Cinderella and Sergei Prokofiev’s music for ballet as its starting points, this production, lasting almost two hours and comprising ten scenes, strips the well-known story of all sentimentality. Maillot poses a specific question: how can the dead shape the lives of those left behind? Rather than the myth of the handsome prince who wins the hand of the poor girl, the choreographer is interested in the intricate and complex web of emotional relationships that motivates the actions of the characters.

In Maillot’s interpretation, Cinderella would like to take refuge in the memory of her dead mother, but the stepmother’s provocative behaviour binds her

Photo: Alice Blangero

to her father instead. Nor are the stepmother’s own daughters ugly or evil this time: they are fully aware of their power. Cinderella’s simplicity and innocence stand in stark contrast with the royal court, which is founded on appearance and pretence. Here is a pure, honest girl in the midst of an utterly corrupt world. For the barefoot beauty to win her freedom, some magic is needed, but what really matters is for this lonely soul to find its other half: like the girl, the Prince stands on the edge of an abyss, until one day when the two young people’s eyes meet.

Reviews that followed the premiere were enthusiastic about Maillot’s concept, appreciating how the story became self-evident and easy to accept for a modern audience once shorn of the clichés of the fairy tale. The stylized and abstract, almost minimalist visuals, composed of shapes, lights and colours, draw attention to the first-rate dancers and

their exceptional performance. Instead of hollow acrobatics and dusty platitudes, critics were pleased to find pure energy and a refreshingly contemporary interpretation, presented with irony, elegance, great dramatic imagination and creative intelligence. The blending of styles has also been praised: magical fairy tale and romantic ballet peacefully share Cinderella ’s spacious stage with burlesque parody and contemporary psychological drama.

In closing, let us return to Monte Carlo and its casino – or more precisely, fickle fortune. JeanChristophe Maillot has a rather singular way of keeping his dancers curious and hungry to perform: the actual cast is announced only a day or two before each show. ‘It will depend on their motivation, their spirit, their capacity,’ he explains. ‘I will never choose a good dancer over a good person. And I tell them every day, I am not casting; they are.’

5 and 6 April | 7pm

Erkel Theatre

LES BALLETS DE MONTE-CARLO: CINDERELLA

11

Photo: Alice Blangero

‘MUSIC IS A POWERFUL RELIGION’

by Gerda Seres

A Grammy and Oscar-winning composer of world renown, Tan Dun considers himself a shaman. His music is a bridge between Eastern and Western culture, and between reality and the spiritual dream world. The Hungarian premiere of his Buddha Passion will take place at Müpa Budapest.

Interestingly, you have many ‘Hungarian connections.’ As you have said in interviews, Béla Bartók was a great influence on you. What inspired you in his music and how has it influenced your work?

I respect Bartók as a model, because he collected the traditional, ancient music of his people and built his own chordal vocabulary from this music. He always dreamed of taking his music to the people in the country whose songs inspired him. My goal is also to engage in a dialogue with the past through my music and keep it alive. 20th century art tended to avoid traditional forms, rhythms, sounds, folk motifs and tonality, but I believe in a shared memory in which they are integral parts.

Once you also mentioned Eugene Ormandy, known in Hungary as Jenő Ormándy, who generated your interest in a conducting career.

He was conducting the Philadelphia Orchestra when it toured China in 1973. Their concert, which I heard on the radio as a teenager, was among my first symphonic experiences, and it changed my life.

For Buddha Passion, which will be performed in Budapest, you drew inspiration from the Mogao Caves near Dunhuang. Can you explain to those who’ve never been there what makes it such a magical place?

Did you know that more than four thousand of the cave paintings there are related to music? Three hundred orchestras and around three thousand instruments were painted on the walls more than 1,500 years ago. It was wonderful to capture this story through the sounds of ancient instruments, and to evoke a soundscape that is thousands of years old.

You have said your music seeks to express the spiritual aspect of life. Is this what Buddha Passion is also about?

I have always seen myself as a musical shaman, who can embrace the future and the past. When I first saw Herbert von Karajan conduct in China, I thought he was the kind of person I wanted to be: a shaman, who danced in the dimensions between the past and the future. It is very interesting to balance between passion and compassion. It was fascinating to hear the ancient Sanskrit language for the first time, the chanting of mantras and sutras. This compassionate melody immediately started to float in my soul. It is magic. The songs, the ancient language and the traditional instruments hold many stories that have given my music the opportunity to bridge the past and the future.

13

You made a serious effort to study the murals, the ancient documents found there. Why did you think this was important?

Many ancient manuscripts were discovered in the cave library, most of which are now in British and French libraries. I remember the first time I opened the Heart Sutra manuscript, I heard the sounds of 1,500 years ago from the Chinese Gobi Desert. Somehow these ancient caves, paintings and manuscripts vibrated for me. That was why I decided to dive deeper into the ancient desert in search of similar stories.

Compared to your earlier works, storytelling is very important in Buddha Passion.

It seems to me that for the last thousand years, every artist from Michelangelo to Bach drew on classical and passionate stories embedded in Western culture. Few drew on Buddhist philosophy, and the Eastern, spiritual approach was rarely employed. That’s why I think this music and these stories are particularly important, because it is time for the West and the East to become our common home. We must learn to share passion and compassion.

The work tells six short stories in quick succession. Why did you choose this almost cinematic style of composition?

I think works of this kind are operas, with many layers of meaning and dramatic situations. I hope that whoever makes the effort to listen more carefully will hear how the many images and sounds come together into a coherent whole. I think Buddha Passion could just as well be an opera. And for me, opera is drama. But what is drama? It could be a story, for example, or the unfolding of characters, but it could also be a surrealistic dialogue between real and imaginary figures, or between past, present and future lives. If I look at it from an avant-garde point of view, the drama can come from the collision of these. For me, the definition of opera is much broader than its 19th century understanding.

How do the ancient Chinese and Sanskrit texts fit into this ‘opera’?

Every part seeks to look at the past and traditions from a new perspective. When you look at it from this angle, a return to tradition always brings new discoveries. My experience is that if I compose for a classical string quartet or symphony orchestra by drawing on a different tradition and chordal vocabulary, it sounds completely different: in essence a new orchestra is created. I strive to put aside my previous knowledge and experience and explore new paths. I always use different traditions because I have to invent new forms and techniques to integrate them.

Buddha Passion has a unique sound, featuring Chinese lutes, water bowls and a Mongolian throat singer. How does the music combine Eastern and Western motifs?

It was wonderful to tell these stories using ancient instruments. Out of personal motivation, I strive to evoke the soundscape of thousands of years ago. My music is always in dialogue with the past, with our history. When I was a child I wanted to be a shaman because I believed a shaman could visualise the next or last life. A shaman used cinematic means, even though at the time no one in Hunan had ever seen a film. The shaman did not have access to modern technology and electronic devices, yet he could captivate people. He could express anything, and in doing so he could coax all kinds of emotions out of people. He was trying to put you in the service of the spiritual, to be able to take you with him into the past or the future. I was attracted by the organic sound and this amazing power. Soon after I realized that being a composer was preferable to being a shaman, because I could translate my ideas about the next or last life into sounds and colours, and share them with my listeners. Music is a powerful religion. As someone who feels at home in several cultures, I attribute

14

Image of Buddha in Cave 3 at the Yulin Cave Temples (Gansu Province, China)

The Mogao Caves which provided Tan Dun with inspiration, near Dunhuang (an oasis town in the Gansu province of today’s China), were discovered by a Hungarian-born archaeologist, Aurél Stein. During his expeditions, the explorer of Asia discovered rich finds in the shrines of the Caves of the Thousand Buddhas.

a spiritual role to music. It prompts you to be open-minded, to embrace the whole world and all people. The music that influences me is essentially of two types, coming from the Eastern and the Western traditions, both of which I am versed in. The music of my childhood was the music of the East: Buddhist chants, Peking opera, the shamanic culture in which I grew up. At that time, I was most influenced by music and spirituality, the ritual chanting that is part of shamanic culture, the Taoist fire dance, where they ‘eat fire’ and dance among the flames, chanting vigorously without words.

Buddha Passion has been performed on stage around the world, but the Budapest performance promises to be visually unique. What makes Müpa Budapest’s production special?

As I said, the inspiration for my opera came from six cave paintings, and to this day I can still see images of them as I listen to it. I walk the bridge between reality and the dream world, and in this particular experiment I try to bring the music of the paintings to life. At the Budapest performance, the audience will also be able to see these paintings brought to life on stage through an extraordinary animation.

14 April | 7.30pm

Müpa Budapest – Béla Bartók National Concert Hall

TAN DUN: BUDDHA PASSION – HUNGARIAN PREMIERE

15

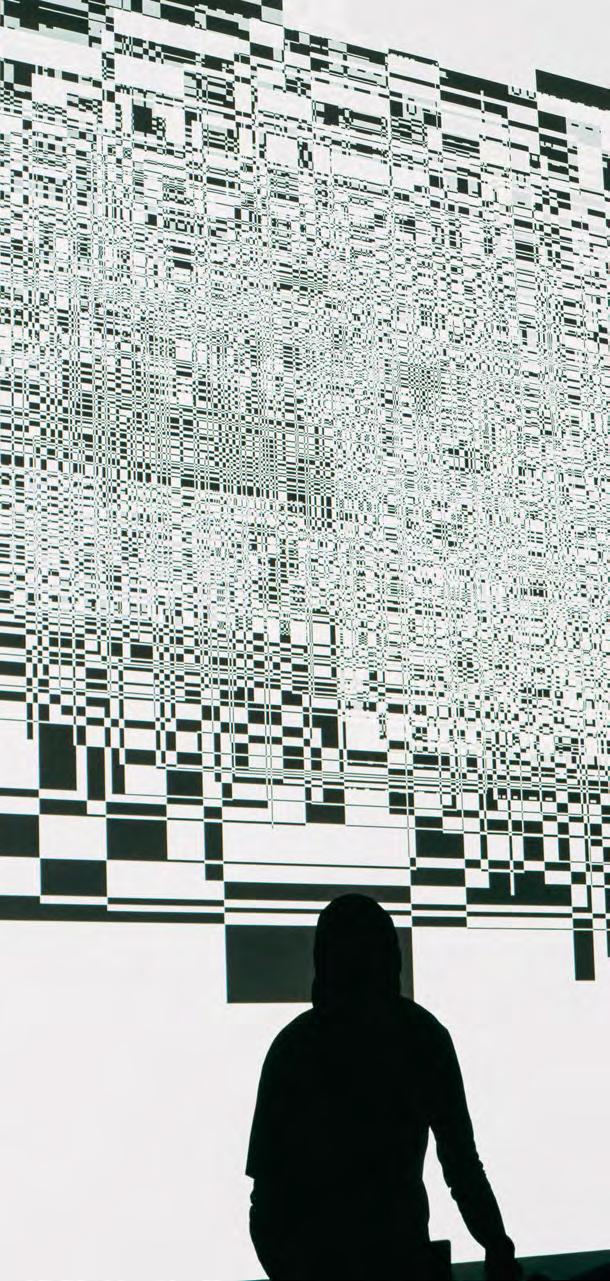

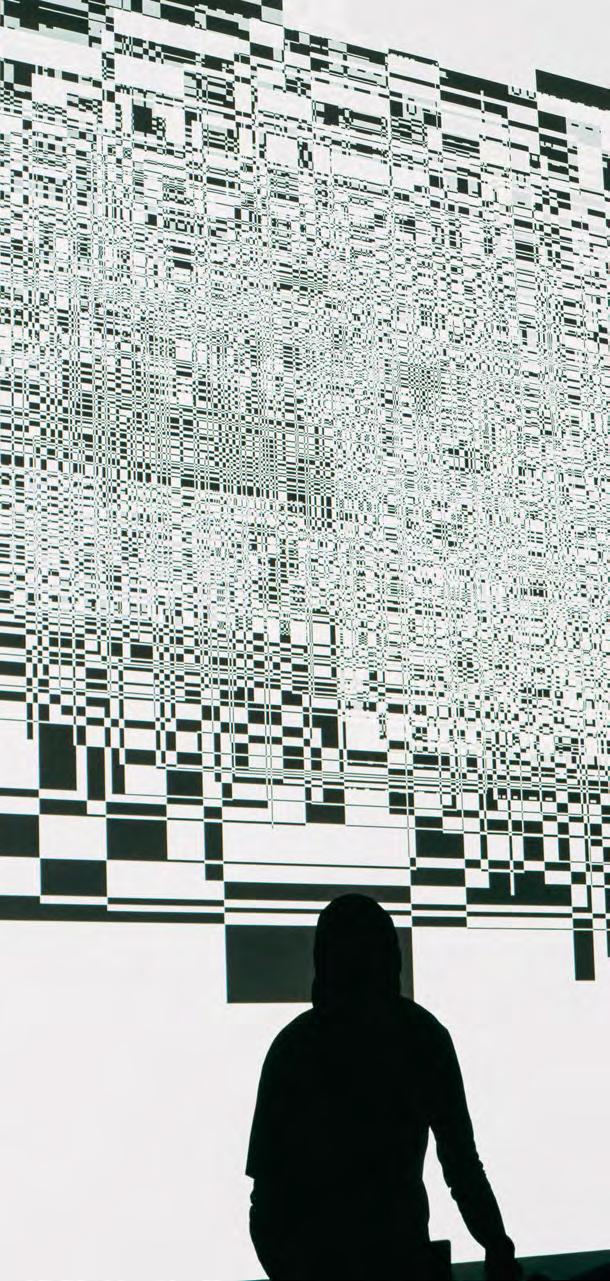

RYOJI IKEDA AND THE ART OF DATA

by Erik Kolbenheyer

‘An attempt to explore the gap between science and the esoteric codes that will stay secrets and external to human comprehension, maybe forever.' (Ryoji Ikeda) Ryoji Ikeda is a leading creator of contemporary electronic music and visual art, with an interdisciplinary approach to art and a minimalist aesthetic that have spawned a style of his own. His long-awaited performance in Budapest is guaranteed to be a complex and lasting audiovisual experience.

A prominent figure in audiovisual electronic music, Ryoji Ikeda was born in 1966 in Gifu, Japan, and currently lives and works in Paris. His artistic arsenal is characterised by mathematical precision, a minimalist aesthetic, and exploration of the relationship between sound and light. His work fuses overwhelming visual stimuli, complex structures and simple line drawings, noise and silence, pulsating light and suddenly fading screens to create inimitable, immersive spatial experiences. Nature and science are inexhaustible sources of inspiration for him, as he immerses his audience in an endless, ever-changing stream of code generated from the vast data sets of CERN, NASA and the Human Genome Project.

ARTIST, MUSICIAN AND SCIENTIST

Ikeda’s artistic journey began in the 1980s, when he worked as a DJ, sound engineer and composer on the Japanese avant-garde scene. By the early 2000s he had extended his activity to visual art, achieving a major breakthrough and international recognition. Since then, he has continued to contribute to the development of electronic music, including intelligent dance music (IDM) and glitch. He is one of the few artists who have managed to create something lasting that traverses the boundaries of genre and media alike.

IN THE LANGUAGE OF DATA

Ikeda’s multidisciplinary approach is about combining sound and vision via the visualisation of mathematical equations, providing the audience with a captivating and thought-provoking experience every time. The key to this unique approach is his ability to synthesise complex concepts into accessible and spectacular audiovisual compositions.

16

Photo: Ryo Mitamura

Most of Ikeda’s works reveal his fascination with mathematical concepts such as prime numbers, arithmetic equations, algorithms and data visualisation. His data.scan series, which transforms raw data into mesmerizing compounds of minimalist visuals and complex soundscapes, offers an original sensory experience that all but calls into question the possibility of comprehending his art and music. Ikeda’s sonic research is underpinned by his meticulous attention to sound design. He often works with pure sine waves, white noise and other fundamental elements of sound, pushing the boundaries of human perception. By deconstructing and reconstructing sound elements, Ikeda creates compositions that not only target the listener’s organ of hearing, but also elicit strong emotional and intellectual responses. The tactical use of silence, extreme frequencies and pinpoint timing are all his artistic trademarks.

AWARDS AND RECOGNITION

In 2004, Ikeda exhibited at JFK Airport in New York City as part of the group exhibition Terminal 5, while in 2014 he won the Prix Ars Electronica Collide@CERN award for digital artists. In 2018, he took part in projects such as Artistes & Robots in Paris, and Experience Traps at the Middelheim Museum in Antwerp. He has had solo shows at prestigious institutions including the Centre Pompidou in Paris, the Whitechapel Gallery and Barbican Centre in London, and the Hamburger Bahnhof in Berlin, and has exhibited installations in Sydney, Moscow, Amsterdam and Tokyo. In 2019, he presented his work Dataverse at the Venice Biennale. Ikeda is currently represented by the Almine Rech Gallery.

WORKS AND PUBLICATIONS

Ikeda has an extensive discography that spans several decades and includes audiovisual projects, solo albums, collaborations and sound installations. He made his debut with the 1996 album +/and then went on to collaborate with Mika Vainio, a former member of the legendary Pan Sonic. With Alva Noto, who recently performed at the House of Music Hungary, he formed a group called Cyclo. Carsten Nicolai and the music community formerly known as the Raster-Noton label played a pivotal role in Ikeda’s career, releasing Dataplex (2005), Test Pattern (2008) and Supercodex (2013), records that laid the foundations for his razor-sharp, minimalist sound. Two of his albums (The Solar System, Music for Percussion) were released by The Vinyl Factory in the UK, before he created the Codex Edition label to distribute his own releases. Besides records, he also publishes art books and research.

ULTRATRONICS

‘I learned everything in the clubs. Nothing intellectual, just, boom boom boom,’ Ikeda has said of Ultratronics, which was released on the Noton label in 2022. As a new set of compositions based on material recorded in the 1990s, Ultratronics is the most accessible album of Ikeda’s career, focusing on sound art as opposed to his trademark minimalism.

A young Ikeda generated these sounds in an attempt to imitate his heroes, but now adopts them to create a mature soundscape. In contrast to his earlier academic pieces, he now guides us through his artistic (and technological) development with a refreshingly playful, self-reflective sense of humour, while paying tribute to the pioneers of the genre.

When the robot narrator of the fourth track tries to count to thirty, Kraftwerk comes to mind. Invoking the NATO phonetic alphabet in sludgy echoes, Ultratronics 07 evokes Throbbing Gristle and other industrial bands, as well as the abstract worlds of Autechre and Pan Sonic. Ultratronics retains Ikeda’s meticulous attitude, but with an added lightness of touch and badly needed sense of fun. The mathematical abstractions are transformed into an overwhelming digital hubbub, as if revealing a computer language that we can hear but not yet fully understand.

Ryoji Ikeda continues to balance on the outer limits of technology, innovation and art, while instinctively creating a surprisingly danceable set. Fresh from an international tour, he appears at the invitation of Bartók Spring at the House of Music.

THE HUNGARIAN SCENE

Hungary has a vibrant electronic music scene, with internationally recognized artists such as Alley Catss, Gábor Lázár and Fausto Mercier, who are graduates of the electronic music media programmes of the Liszt Academy and the University of Pécs. This evening the latest generation of Hungarian artists will be represented by yibai, aka Dávid Gerlei, who is in the second year of the programme at the University of Pécs. He presented his first album, Rianás (Exiles, 2023) in the library of Budapest Music Center. That EP, which featured elements of ambient chill, IDM and contemporary classical music, was followed by several singles, and then a new album at Temporary Nites, another Hungarian label.

6 April | 8pm

House of Music Hungary – Concert Hall

RYOJI IKEDA: ULTRATRONICS

Live set

17

6 and 7 APRIL | 7.30pm

Müpa Budapest – Béla Bartók National Concert Hall

RUDOLF BUCHBINDER AND THE HUNGARIAN NATIONAL PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA

One of the foremost pianists of our time, Rudolf Buchbinder is widely considered to have set an exceptionally high standard with his interpretations of the works of Ludwig van Beethoven. With a performing career stretching over more than sixty years, the artist now comes to Budapest to perform all of Beethoven’s piano concertos over two evenings at the invitation of the Bartók Spring.

Rudolf Buchbinder is one of the most outstanding contemporary performers of Beethoven’s works, having played all of his piano sonatas more than sixty times. Along with the piano works of Haydn, Mozart and Brahms, the Austrian pianist – who was born in what is now the Czech Republic – has recorded all of Beethoven’s piano concertos several times, most recently on the occasion of his 75th birthday in 2021, as part of Deutsche Grammophon’s Buchbinder: Beethoven collection. In 2014, Buchbinder dedicated an entire book to his relationship with Beethoven, and in his autobiography he writes: ‘You may overindulge and get bored of some foods. But you can never overindulge when it comes to playing the masterpieces of piano literature, even if you have performed them hundreds of times.’ Of course, for someone like Buchbinder, who plays these pieces with an unceasing curiosity, respect for tradition and simultaneous thirst for freedom and innovation, every concert is exciting – just as it is for the audience on such occasions.

7 APRIL | 8pm

Akvárium Klub – Main Hall

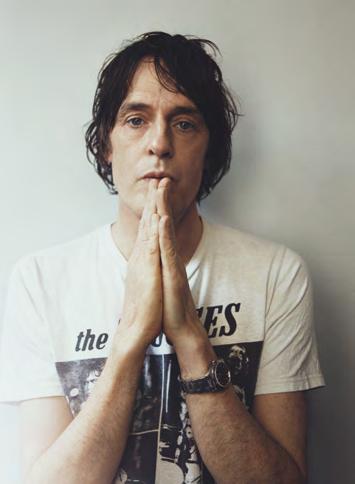

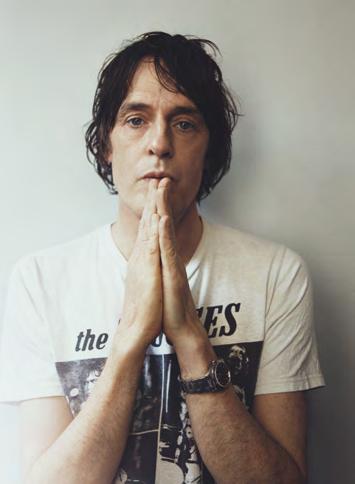

SPIRITUALIZED

If there’s one concert to fulfil a long-felt need in Hungary, then it’s surely the first performance here of Spiritualized, the British neo-psychedelic band that has been an essential act for more than thirty years. The cult British outfit was responsible for one of the best albums of the 1990s, though their latest record, released in 2022, continues to uphold the same high standard as their nine previous LPs.

If there’s one band you have to see – and not just at this year’s Bartók Spring, but in general – then Spiritualized is definitely it. A lucky few in Budapest may actually have heard the band’s frontman, Jason Pierce, when he performed in a small club in 1989 with his previous, no less legendary band Spacemen 3. Along with Sonic Youth, The Jesus and Mary Chain and My Bloody Valentine, Spacemen 3 were pioneers of noise rock in the 1980s, but disbanded after four studio albums. The core members, led by Pierce, formed a new group, which called itself Spiritualized. Over the years, the line-up has changed many times, with the bandleader remaining the only constant member, but the quality of the music has remained consistently and reliably high. The band is essentially impossible to pigeonhole, accommodating many styles from noisy garage and space rock, through ethereal, floating psychedelia, to many other influences (soul, blues, ambient, gospel, free jazz, shoegaze). If the style of the songs is difficult to pinpoint, their mood is easier to grasp: Spiritualized is capable of a wide range of sounds, from impressively constructed symphonic escapades to layered themes culminating in explosive climaxes. And for this experience, you can listen to virtually any of their albums: the angelic ambient-shoegaze symphonies of their beginnings (Lazer Guided Melodies, 1992), the diverse, epoch-making magnum opus (Ladies and Gentlemen We Are Floating in Space, 1997), or their latest release (Everything Was Beautiful, 2022), which explores very human themes. And not as an extra, but as the main feature, they can do all this live with perfect intensity. It’s a concert not to be missed.

18

RUDOLF BUCHBINDER Photo: Marco Borggreve

JASON PIERCE

Photo: Sarah Piantadosi

8 APRIL | 7.30pm Budapest Music Center – Concert Hall

JÓZSEF BALOG’S PIANO RECITAL

Szabó: Complete Solo Piano Works –album release concert

Transylvanian-born Csaba Szabó (1936–2003) was a versatile composer who wrote his solo piano pieces, recently recorded by József Balog, in the period between 1955 and 1981.

Liszt and Lajtha Prize-winning pianist József Balog is an heir to the internationally renowned Hungarian piano tradition, the foundations of which were laid by Ferenc Liszt, Ernő Dohnányi and Béla Bartók. His brilliant technique and deep, sensitive musicianship have earned him the appreciation of critics and the enthusiasm of audiences at over a thousand solo and chamber concerts in more than twenty-five countries on three continents. His latest album presents all of Csaba Szabó’s piano works, making it now possible to appreciate directly the richness of this part of the composer’s œuvre, in form, technique and content alike. The first piano pieces are youthful works that reveal both Szabó’s joy of composing for the instrument and his chief sources of inspiration. His study of folk music led to changes in his musical idiom, while his 1970s output strikes the listener as a veritable avant-garde turn.

6 and 7 APRIL | 7pm Müpa Budapest – Festival Theatre

DUNA ART ENSEMBLE: SZÉKELY GATE – premiere

JÓZSEF BALOG

The new production of the Duna Art Ensemble is focused around the traditional Székely gate as a symbol, a spiritual message, and a richly meaningful structure. The director of the production is Zsolt Juhász, while its music editors are István ‘Szalonna’ Pál and Sándor Csoóri Jr. The lead performers are singer Andrea Navratil and the Göncöl band.

The Székely gate has a message for those who pass through it: ‘Blessings to you who enter, peace to you who leave.’ Yet its symbolism is even more complex. Its three posts represent the unity of body, soul and spirit, and its carvings are symbols that render protection, grace and blessings. In general, it is a symbol of ancient power, faith, hope and belonging to God, a channel of communication between heaven and earth. It is from this that the Duna Art Ensemble drew inspiration for its production, whose creators want the show to ‘open a passage between two spheres, the sacred and the secular.’ This evening, the past and history of the Székely people will be brought to life, and long-forgotten dances performed. The soloist is folk singer Andrea Navratil, who, in addition to being the solo singer of the Duna Art Ensemble, sings with the Kobzos and Fonó ensembles, while also appearing as a guest singer in András Berecz’s shows. Accompaniment will be provided by Göncöl, the in-house band of the Duna Art Ensemble.

19

Photo: Tamás Végh

Photo: László Emmer

20

Self-portrait Courtesy of the artist

A PASSIONATE EUROPEAN

THE WORLD OF TILL BRÖNNER

by Lili Farkas-Zentai

You let yourself drift, become engrossed in one moment or another, live in the fleeting present, and then open up or close in on yourself: this is the effect Till Brönner exerts on either side of the borderline of ‘artistic beauty.’ Often dubbed the ‘German Chet Baker’ for the melodiousness of his playing, the virtuoso of the jazz trumpet now claims the limelight as a photographer. While usually telling personal stories and conveying important emotions, his images also delve into questions of European identity. Composed to the rhythm of diversity, they capture the distinctive structure of depths and peaks, dreams and realities.

Till Brönner is best known to the general public as a renowned trumpeter; indeed, he is considered one of the most successful German jazz musicians of all time. The ‘German Chet Baker’ was raised in Italy and the Rhineland in a family of musicians. Following classical music training, he studied jazz trumpet with the late Jon Eardley at Cologne College of Music. He has worked with greats of jazz and pop alike, including Herbie Hancock, Annie Lennox, George Benson, Carla Bruni, Al Di Meola, Chaka Khan, Natalie Cole and Al Jarreau, to name a few. Brönner took up photography over a decade ago. His main source of inspiration was the work of music and fashion photographer William Claxton, which he encountered through German filmmaker

21

Cellists of the Berlin Philharmonic, Berlin, 2014 Courtesy of the artist

Julian Benedikt’s 2001 documentary, Jazz Seen, for which he wrote the score. This made Brönner aware of how jazz and photography have much in common. As German curator Walter Smerling later pointed out, both Brönner’s music and photography convey emotions, create atmosphere and share the uniqueness of the moment.

Brönner bought his first Leica M8 camera in 2009 and has remained loyal to the brand ever since. Having started by taking portraits of fellow musicians during his concert tours, he then ventured into other fields, asking actors, sportspeople, writers and activists to pose. From the outset, he involved the viewer in an idea, a moment or an emotion with tautly constructed close-ups. His photographs tell stories, with appropriate dignity. His portraits soon became popular, and in 2014 the prestigious teNeues publisher issued his photo album, Faces of Talent.

While portraiture is undoubtedly Brönner’s ‘speciality,’ he widened his angle of view with the 2019 exhibition Melting Pott, a project for the MKM Museum Küppersmühle, a museum of contemporary

art in Duisburg, which documented the ‘remnants’ of his family’s roots in the Rhine-Ruhr metropolitan region, mostly through landscape photos. Always a sensitive observer, he was again telling stories, but this series complemented his personal viewpoint with a contemporary attitude to life and social trends, creating new meaning. Comprising 185 pieces, the Melting Pott series portrays an entire region, a former centre of coal mining where more than ten million people now live, which is also an important scene of German industrial architecture and the cohabitation of multiple ethnicities.

‘This project is an important milestone, not only because of its socio-economic aspect, but also for Brönner’s career as a photographer,’ says Julia Fabényi, director of the Ludwig Museum – Museum of Contemporary Art about the exhibition, Identity – Landscape Europe, which opens in April. ‘In 2018, the last underground coal mine was closed down in the Ruhr area, effectively ending the region’s 250year history of heavy industry. All this is happening at the dawn of an energy crisis, putting hundreds

22

Cattle, Galicia, Spain, 2024 Courtesy of the artist

of thousands in the region on the dole. At the same time, the remains of closed industrial complexes do not undergo a simple change of function: they are demolished, buried, liquidated or transformed. As a documentary photographer, in this series Brönner captures this landscape, this habitat – his homeland. Or whatever remains of it. Sometimes he remembers in the language of cold and abstract forms, while sometimes he gives in to emotions and focuses really close – searching, in the process, for his own identity.’

Since 2021, Brönner has shifted his focus to Europe. Through the unique viewfinder of his own identity, his most recent works seek to interpret the vision of being European and the complexity of the world. Tapping into his mastery of multiple arts, he sensitively documents and emphasizes the social endeavours underway in Europe, while not ignoring the problems of a world in crisis. Although mostly interested in the big picture, notes Fabényi, Brönner focuses on diversity in his works. This reflects his mission: to present the depths, the highs, the illusions and realities, since it is these aspects together that give the whole picture, the extra-wide shot.

Exhibitions at the Ludwig Museum in Budapest are usually very topical. After exploring the themes of the pandemic, sustainability and artificial intelligence in earlier shows in the museum setting, Brönner’s exhibition looks at what it means to be European, Hungary’s 20 years in the EU, and its EU presidency this year. Debuting in Budapest, Identity – Landscape Europe presents the work of two years. While the museum made suggestions, Brönner himself chose and visited the Hungarian subjects of his photographs. Among others, he took the last photograph of one of the most influential pioneers of computer art, Vera Molnár, who passed away in December 2023 and whose work is on view at the Ludwig Museum’s show À la recherche de Vera Molnar, which is open until April 2024.

The unique outlook which increasingly informs Brönner’s new projects is reflected in motifs that reveal something special in everyday life, finding the distinctive character of unity in diversity wherever he goes. Balancing on the line between documentary and staged photography, this amounts to a kind of ‘rediscovery’ of Europe.

‘Brönner’s black and white world has a special message,’ says Fabényi. ‘Instead of specific colours, he uses mostly grey tones to nuance his message. His photographs are moments observed with deep emotion. His creative openness allows him to do without deliberate composition – he simply leaves the effect to be felt. Just like in music.’

14 April | 10am

Ludwig Museum – Museum of Contemporary Art

TILL BRÖNNER: IDENTITY –LANDSCAPE EUROPE

The exhibition is on view between 14 April and 25 August.

23

Priest, Rome, Italy, 2017 Courtesy of the artist

13 / 04 / 2024

— 08 / 25

The Ludwig Museum can be visited free of charge at one occasion of choice with valid tickets of the Müpa until the day of the concert!

Ludwig Museum –Museum of Contemporary Art Müpa Budapest, H1095 Budapest, Komor Marcell u. 1.

ludwigmuseum.hu

IDENTITY — LANDSCAPE EUROPE

JUST READ!

by Anna Ott

When I was in primary school, I admired my Hungarian teacher. I hated all the other subjects, and was only interested in literature – and grammar, because it somehow went with it, so wasn’t a big problem – but the icing on the cake was when the teacher came in and started to tell stories. She simply knew everything about the most extraordinary people, about authors. It’s one thing that she knew when and where they were born, when, where and why they died, and what daily things happened to them along the way. She also knew what poetic images, metaphors and similes were employed in the poem we read out together (which I would then try to learn at home, repeating it while pacing up and down, fighting back tears, raving and flapping my hands, until I knew it by heart); what style it

25

Photo: Zoltán Tombor

adopted; and whether the rhyming pairs used were monorhymes or enclosed rhymes (though I could only ever remember the name of couplets). So the teacher would come in and tell us, or rather, dictate, what the poet had been thinking, feeling or wishing for when he wrote ‘Lay your hand / on my forehead, / as if your hand / were my hand.’ But the real magic actually happened when she was telling us about these things, because though it says ‘lay your hand on my forehead,’ that’s not what it means! Because in the case of a poem, it’s as if the words were sprinkled with magic powder: I can see them, I can read them, I understand them, but never, not once, do they mean what I’d think they mean. And this is the key role of the teacher, who knows everything! She knows when the poet wrote the poem; where he was when he wrote it; on what scrap of paper and with what kind of pen; where it was found, by whom and when; what kind of health and personal issues the poet had (because they always had them); to whom he owed money and how much; whom he had lost or would lose in the war, whom he was or would be mourning; with whom he was in love, and who, by contrast, was his wife; and of course, the causes and circumstances of his imminent or quite distant death, which the teacher could also accurately decipher from those lines. If all went well, she would also cite cities and years, my only task being to copy them exactly into my notebook, because if I didn’t, I’d lose points in the next week’s test, get a lower grade, and I’d be in trouble if I couldn’t even get an A in my favourite subject.

In secondary school, I was becoming more and more affected by books, and feeling more and more certain that these stories would be an important source of sustenance in my life. But my Hungarian lessons and my Hungarian teacher I now found less wonderful. She was a person of great knowledge who expected us to know a lot, and we had to memorise at least three times as much information about a poem as we’d been given in primary school. We were given key formulae for all the poems, the only problem being that although I memorised them, I always forgot which key opened which poem, and when it came to grades it mattered little how much I liked spending time with the poems, what effect they had on me, or such like. The magic was gone

and my suspicion grew. Can you be sure that a Hungarian teacher in Budapest in the 2010s would know exactly what was going on in the mind and soul of a young Frenchman writing poetry in mid-1800s France? Is this really the best way to get young people to love poetry and read it outside school? To the last question, I have the correct answer, which I offer now from the present: it is not. I know this because I’ve been a reader for at least twenty years, I loved books from a young age, and I have read a lot, but I always avoided poetry because I was so afraid of it. I knew I couldn’t understand it anyway.

I was at university, and an intern at the culture column of a daily newspaper. There was a poem pinned on the notice board. Once I asked who had written it, and was told it was one of the editors, who would soon thereafter come in to work. (It was already a challenge to understand he was a poet with a job.) He was young, he wore a baseball cap and trainers, he talked, was at home in the world as we know it, and yet he was a poet. I was twenty and still found it difficult to come to terms with the fact that poets walk among us, that they can be young, that they can look like completely normal people, while their volumes of poetry can be bought in any bookshop.

He and all the other poets I’ve had a chance to talk to in my life knocked down the wall I had erected between poetry and myself, because thanks to them I learned they were not out to test me, and what they were trying to impact with their poems was not my consciousness, but my feelings. In a word: it doesn’t matter at all what the poet had in mind. Only pay attention to what you’re feeling when you read their lines. Just read!

I have been working closely with literature for ten years. For ten years, all my work has been predicated on the simple fact that you have to read, because reading is good. It’s a wonderful experience, I have found over the years, to catch sight of the person behind the text. Meeting the author may provide the key to a poem, though here and now I would like to dispel the idea that poems have keys. For this year’s Day of Hungarian Poetry, therefore, we are preparing literary events

26

especially for secondary school students in the hope of awakening or restoring their passion for poetry. We celebrate Poetry Day on 11 April, Attila József’s birthday. Through the poems most of us know, and the poet’s life and loves, which we all know about, Miklós H. Vecsei shows us who Attila József really was, what he means to us today, and what kind of devastating passion and desire to live burned within him.

Spurred by a shared obsession with Sándor Petőfi, the musician Krisztián Szűcs and the poet Balázs Szálinger formed Szücsinger, a duo that has proved for years that Petőfi can be psychedelic, that the Beatles have a place at a literary event, and that their own teenage poems are nothing to be bashful about.

Zsolt Prieger, of Anima Sound System fame, has been living proof for years that music and words go hand in hand, tailoring his music to the texts of the giants of Hungarian literature. He has now set the works of Mihály Csokonai Vitéz to music, in arrangements that will be performed by a rapper, MC Tink. As János Térey, another great Debrecen poet wrote: ‘Csokonai’s œuvre is a forest of whispering foliage, as dense and as full of surprises as perhaps those of two other Hungarian poets, Weöres and Arany. The world of his teasing lovers and sunlit gardens is akin to that of Mozart, who likewise died at the height of his powers.’ An hour’s worth of humour, philosophy and contemplation: it’s guaranteed to be a great experience; you have to see how talk, wit, toughness, tradition, and especially danceable music, come together.

Ever partied to Csokonai, Petőfi or Attila József? Now’s as good a time as any to start!

11 April | 9am

Müpa Budapest – Festival Theatre / Glass Hall / Blue Hall

DAY OF HUNGARIAN POETRY

Literature for high schoolers

27

Photo: Zoltán Tombor

‘I REALLY CAME INTO MY OWN

IN JAZZ’

INTERVIEW WITH JÚLIA KAROSI

by Anna Takács-Koltay

Júlia Karosi was in her mid-twenties, following a detour into academia, when she found the path she now follows. She believes it takes patience and time to achieve results, to reap the rewards of the work she has put in to a life now lived fully for music. Following her concerts of Gershwin, Sondheim and Bartók arrangements, Karosi introduces her new record, Inner Voice, at the House of Music on 5 April, inviting the audience on a deep spiritual journey. She will be joined by the boldly experimental Estonian pianist Kristjan Randalu and Canadian trumpeter Ingrid Jensen.

Your mother, Júlia Pászthy, is an opera singer, so you were taught the foundations of classical music as a child. Was it evident from the start that you loved music?

I had musical experiences even before I was born, because my mother kept singing during her pregnancy. It was during this time that she recorded Bachianas Brasileiras, the song cycle by Brazilian composer Heitor Villa-Lobos. Listening to it again as an adult, it had such an effect on me that I’ve covered one of the songs on my new album. My brother, Bálint Karosi (an organist and composer who lives in New York – ed.), also played several instruments from a very young age. I started by learning the piano and the violin, but even then I also sang every day. I toured the world with Zsuzsanna Gráf’s Angelica Girls’ Choir until I graduated from secondary school.

You took a detour before starting a musical career, gaining a degree in aesthetics and philosophy at Eötvös Loránd University. It was only afterwards that you actively pursued and studied jazz. Did you not believe in a career in music?

I was interested in aesthetics and philosophy, and to this day I’m glad I attended because the artistic affiliations were very inspiring for me. But while at university, I found myself missing music so much, I realized I couldn’t live like that! (Laughs) It was a tradition in our house for my mother to organize several home concerts every year, where some of the performers were famous artists. On one such occasion I sang jazz for the first time, some Gershwin songs accompanying myself on the piano. It was a great success, which surprised me. But with all the encouragement I received, I started to study jazz, and Gábor Winand was my first vocal teacher.

In 2008, you were admitted to the jazz singing programme of the Liszt Academy, where your teachers were Ágnes Lakatos and Tamás Berki. Your example proves it’s never too late to start something new if you feel you’re not following your own path. I’m a late bloomer. As a young adult I didn’t have a sense of purpose or confidence in what I wanted to do, and I was even drifting a bit. I also think that the genre of jazz requires a great deal of maturity, not only musically but also emotionally and sonically, and maybe that’s why it came into my life later.

Your first album already contained your own compositions, and later the doors opened to the international music world. You had an album released in Japan and New York, while your latest record came out under a German label, receiving a lot of favourable reviews. How do you write songs?

29

Photo: Dániel Gaál

I was ten when I wrote my first songs, which make me smile now because they were surprisingly sombre chansons. I also liked to write poems, trying out how they would sound when sung. I really came into my own in jazz, because improvisation itself is actually real-time composition, and that somehow made me start working on my own sound and songs. As a singer and composer of vocal pieces, I’m very interested in how lyrics and the absence of lyrics alternate in vocal expression. I’m experimenting with that on the new album too, alternating between the two directions.

After winning the Lakatos Ablakos Dezső Jazz Performance Scholarship, you worked on your arrangements of Bartók’s Mikrokosmos for three years with a scholarship from the Hungarian Academy of Arts. How did you approach these works?

That scholarship was a very important milestone for me. It allowed me to really immerse myself in work. The arrangements were to answer a practical need, namely to provide theoretical training to singers at the Bartók Conservatory, where I teach. I always wondered how these modal and distance scales could be put into a more musical context so that they’re not just dry theoretical material. I remembered Bartók’s Mikrokosmos, which serves this purpose perfectly because the pieces can be easily placed alongside theoretical examples. I took sections, we learned them, and we first sang the scales along with them, and then we improvised with a simple exercise, and it worked very well. So that’s how I started working on these pieces, and later made transcriptions that we recorded on my previous album with Ben Monder.

You’re about to give an album release concert with two amazing musicians. Kristjan Randalu’s music and playing have been an important source of inspiration for you for years. What was it like to work with him?

I first got to know Kristjan Randalu through the records he released with ECM, and then heard him at a live concert at the Budapest Music Center, where he improvised on Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition. I was really impressed by that concert. Kristjan has a completely unique way of approaching and improvising on classical pieces. I managed to pluck up the courage to approach him with the idea of ‘what if...’ This led to a joint concert at the Liszt Academy, where Gábor Juhász was the featured guest. That was where we played together for the first time, and the experience inspired us to start working on the album. The way I worked with Kristjan was really unusual, as initially we swapped musical ideas by e-mail and online. The sound of the album is really stripped down, with only voice and piano most of the time. We’re joined by Canadian trumpeter Ingrid Jensen on three of the songs, including one written by Kenny Wheeler.

The record is called Inner Voice. Do you listen to that voice?

It’s an associative title with many layers of meaning, and it’s also my title composition. For me, the inner voice is a compass that guides us in music, in singing and in life. It’s important to be able to listen to that voice, and when we find it, it gives us enormous freedom. The counterpart of this composition is Soul Place, which has a similar theme. It’s about the place where your soul finds peace and finds itself. There’s also a very playful, wordless composition of mine on the album, called Tig-Tag, as well as a piano piece by Mussorgsky for which I wrote English lyrics. I gave it the new title Mother and Daughter, and it explores this mystical relationship. Along with three compositions by Kristjan Randalu, there’s also a folk song arrangement and transcriptions of pieces by classical composers. There is technical and stylistic variety to the material, coupled with an intimate sound. In addition to the material on the album, we have some surprises for the concert, where you can buy the record in physical format before it’s released online. The House of Music is a wonderful complex, where the glass back wall of the concert hall makes you feel like you’re performing in nature. It’s incredibly inspiring and very much in line with what the new album has to say.

Besides music, you teach and raise a child with your husband, the drummer of your quartet, Bendegúz Varga. How do you recharge during the week?

To wind down, I look for activities associated with silence, rather than sounds, and which also remove me from the noise of the online space. These include hiking with my family, reading and writing. These are the things I most like to recharge with. While teaching, it’s always important to remind yourself how much feedback you receive from your students. It’s beneficial to be surrounded by younger people, and it also shapes my musical tastes as I’m often introduced to new music by my students. In this way, what I do in music is not concentrated on a single thing: performing, creating and teaching are all part of it, and these three activities are constantly interacting, building on and enriching each other.

5 April | 8pm

House of Music – Concert Hall

JÚLIA KAROSI

INGRID JENSEN

KRISTJAN RANDALU

Inner Voice – album release concert

30

EXHIBITIONS | CONCERTS | MUSIC EDUCATION

9 APRIL | 7.30pm

Müpa Budapest – Béla Bartók

National Concert Hall

PURE SOURCE

An evening of arts based on Bartók’s Turkish and Hungarian collections

Directed by Csaba Káel, Pure Source is a multidisciplinary art production which, highlighting the affinities between Turkish and Hungarian music and building on the close bonds between music and dance, presents some characteristic pieces of Bartók’s œuvre.

Béla Bartók is a key figure in Hungarian music history, both as a composer and a collector of folk music, whose work is an essential component of Hungarian culture as we know it today. The œuvre of the composer and musicologist is also of consequence beyond Hungarian folk and classical music, continuing to inspire artists active in world music, jazz and overlapping forms. In addition to Hungarian folk music, Bartók was also interested in the music of neighbouring peoples, and even of those in more distant lands such as Turkey. Pure Source approaches some characteristic pieces of Bartók’s multifaceted œuvre by focusing on the connections between Hungarian and Turkish music, as a host of leading performers join forces to interweave music and dance. Along with singer 'Meshi' Mária Majda Guessous and players of world and folk music, the show features the Ballet Company of Győr, the dancers and orchestra of the Hungarian State Folk Ensemble, and – from a recording – the Danubia Orchestra (conducted by Kornél Fekete-Kovács). The visuals will also be unique, thanks to a site-specific animation by LaLuz, which fills the entire space of the Béla Bartók National Concert Hall.

11–13 APRIL

Clubs in Budapest

BUDAPEST RITMO

Launched in 2016, Budapest Ritmo has become one of the most important world music festivals in Central Europe in the course of a very short time. It is always an inspired few days in terms of both structure and content, with legendary stars, performers worth discovering, showcases, a unique film programme and conference. In 2024, it will be held once again at numerous venues in the heart of Budapest.

As before, variety is the event’s watchword, from Bantu punk to Welsh harp, and from Balkan brass to ethno-jazz fusion. It’s a chance to escape the familiar rut and discover something new. As is now customary, the festival starts with a Showcase Day, which concentrates on fresh talent from the region, presenting performers who may well end up being key presences on the scene in future. In addition to the conference for professionals, Friday and Saturday are the days for concerts and film screenings. Of the latter, the premiere of a film about a cappella trio Dalinda stands out, while there is insufficient space to list all the exciting productions included among the former. Headlining on 12 April will be Gaye Su Akyol, whose record was named Best World Music Album of 2023 on the World Music Charts Europe, blending Turkish traditional music with neo-psychedelia and surf rock. On 13 April, Salif Keita, one of the kings of African music and a key player since the 1970s, will perform in a very special trio line-up. And there’s plenty more for music fans to immerse themselves in. The Bantu punk of BCUC from South Africa promises a pan-African style explosion, while the new prince of Balkan brass, Džambo Aguševi, will get the city itself hooked on his pulsating music. Gérald Toto charms the audience with fusion chansons, while a modern Welsh bard, Cerys Hafana, introduces a special instrument, the Welsh triple harp. Estonian harp duo Puuluup play their own brand of nu-folk, evoking the Baltic Sea; Italian minstrel Luca Bassanese and La Piccola Orchestra Popolare promise a rousing concert; and the international collaboration of Béla Ágoston and Theodosii Spassov is set to delight fans of ethno-jazz. The joint show of the Czech Terne Čhave and the Hungarian Romano Drom promises a feast of Roma music, while Hungary’s own Decolonize Your Mind Society defy categorisation, but are sure to blow our minds. An unforget table musical journey from Africa to the Baltic Sea awaits.

32

Photo: Szilvia Csibi / Müpa Budapest

SALIF KEITA

Photo: Thomas Dorn

9 APRIL | 2pm

Hungarian National Gallery

WHEN DOLLS SPEAK

A retrospective of the life’s work of Margit Anna (1913–1991)

The visual arts focus of Bartók Spring 2024 culminates in a retrospective of the life’s work of Margit Anna (1913–1991), entitled When Dolls Speak. Assembled by curator Marianna Kolozsváry, the show can be seen at the Hungarian National Gallery between 10 April and 1 September.

Margit Anna created a unique formal idiom that made her one of the most outstanding figures of Hungarian painting. This first retrospective of the artist – almost fifty years after her last exhibition – presents nearly 200 paintings and graphic works, offering a view in unprecedented detail of an artist who lived through the most arduous periods of the 20th century. It is difficult to classify Margit Anna’s works as belonging to any one artistic movement; a significant part of her œuvre can be best described along the lines of surrealism and expressionism. Sensuality and unflinching clear-sightedness are both salient characteristics of her art, which combined elegant decorativeness with soul-searching. Her lyrical mode, which followed the school of Chagall, underwent radical change after the tragic death in 1944 of her husband, painter Imre Ámos. In the works she painted during her time with the European School, almost inexpressible suffering was represented by dummies with giant heads, before absurd humour and sarcasm became an increasingly important aspect of her art in the 1950s and 1960s.

Margit Anna: Angel, 1968 © Kolozsváry Collection

8 APRIL | 7.30pm

Liszt Academy – Grand Hall

SÖNDÖRGŐ

KELEMEN QUARTET

Bartók–Balkans Revisited

The one-off joint concert of Söndörgő and the Kelemen Quartet promises to be a unique treat, where the performers evoke the musical heritage of Béla Bartók in an original manner. Söndörgő, a tambura orchestra that has enjoyed international success on the world music circuit performing Southern Slav music with the energy of a rock band, follows in Bartók’s wake alongside the Kelemen Quartet, a critically acclaimed string ensemble no less famous on the classical scene, playing both separately and together.

The programme of Bartók–Balkans Revisited pays tribute to the work of Bartók in several ways. The backbone of the show is provided by the collection in which Bartók excelled. The material which inspired Söndörgő’s songs was collected by the composer in 1912, in Temesmonostor and Sárafalva near the Serbian–Romanian border. Also featured will be arrangements for tambura orchestra of pieces by Bartók (e.g. Allegro Barbaro), and excerpts from Söndörgő’s upcoming album, Gyezz, set to be released in the summer of 2024. Katalin Kokas and Barnabás Kelemen will interpret Bartók’s violin duets, while the classical ensemble’s performance of String Quartet No. 5 promises to be one of the highlights of the evening. Inspired interpretations of the material Bartók collected in the Banat region are guaranteed at the concert of Bartók–Balkans Revisited

SÖNDÖRGŐ

Photo: The Orbital Strangers

33

‘CAN WE HELP IT IF THE BEST PHOTOGRAPHS SEEM CONSISTENTLY TO BE PRODUCED BY HUNGARIANS?’

by Lili Farkas-Zentai

This question was asked by the American Coronet magazine, which published some of André Kertész’s works in 1927. Although it was suggested in jest, the notion was not unfounded, since at that time Hungarian photographers were at the vanguard in Berlin, Paris, and later New York. László Moholy-Nagy, Brassaï, Martin Munkácsi, Robert Capa and André Kertész all found success abroad; their talents matured as they made their way to the New World from Budapest, and they became major figures in international photography.

Many of the world’s great photographers are considered Hungarian, and the most famous of them – André Kertész, László Moholy-Nagy, Brassaï, Martin Munkácsi and Robert Capa – belonged to the same generation. With the exception of Capa (born in 1913), all the above were born in the last decade of the nineteenth century and reached adulthood before or during the outbreak of the First World War. They all excelled in a new craft where talent was more important than institutional background. They believed that they could change the world, at least as much as the world around them had changed.

Many were forced to leave their homes during the wars of the 20th century. They first moved to the metropolises of Western Europe – Vienna, Berlin, Paris – before moving on to New York.

During the Second World War and the subsequent Cold War, most took refuge in the United States for political or economic reasons. They came to know new cultures during their wanderings, leading them to redefine themselves, while remaining marked for life by their Hungarian identity.

As Arthur Koestler wrote, ‘Hungarians are the only people in Europe without racial or linguistic relatives… therefore they are the loneliest on this continent. This perhaps explains the peculiar intensity of their existence... Hopeless solitude feeds their creativity, their desire for achieving and their hysteria. To be Hungarian is a collective neurosis.’

Each one of these artists had a different strategy for survival, for attaining success. André Kertész, for example, never mastered a foreign language, and somehow became stuck in this loneliness, a kind of Hungarian defiance, whereas Robert Capa (born Endre Friedmann) took on a euphonious name to sell his photos more easily, and had a reputation as a socialite. Capa professed what was then the so-called ‘Hungarian credo’: deal with whatever life throws at you by putting on a brave face, and things will sort themselves out. This attitude might also explain why he bought a stylish Burberry raincoat specifically for his shoot of the D-Day landings in Normandy.

Their unique and captivating personalities were of course not the only thing through which these émigré Hungarian photographers left their mark. Their peerless vision had a profound impact on the development of American photography. Kertész found fame with his abstract and surrealist style, Capa with his war photography, Munkácsi by creating the genres of open-air portrait and fashion photo, and Moholy-Nagy with his photograms and constructivist approach.

While enriching American photography with their artistic values, they also contributed to the diversity of American society through their cultural experiences, with some specifically addressing issues of emigration and cultural adaptation in their work. They thus became important figures in the 20th-century culture shift in the United States.

Numerous exhibitions have been dedicated to Hungarian photographers’ influence on photography as an art form around the world. These included The Hungarian Connection at the National Museum of Photography, Film and Television in the UK in 1987, and The Hungarian Circle at New York’s Howard Greenberg Gallery in 1995, which featured forty-nine Hungarian and Hungarian–American photographers. The most recent such show, Eyewitness at the Royal Academy in London in 2011, presented the work of Rudolf Balogh, Károly Escher, Kata Kálmán, József Pécsi, Dénes Rónai, Ernő Vadas, György Kepes and Éva Besnyő, alongside photographers already known the world over.

The presentation of American–Hungarian photographic connections now reaches a significant new milestone with the exhibition Hungarian Photographers in America (1914–1989), which opens in April 2024. Featuring nearly thirty artists – from the greatest to those lesser known in Hungary – the show aims to highlight the extraordinarily rich American–Hungarian photographic heritage. It will also be the occasion for Alex Nyerges, director of the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts and co-curator of the exhibition, to present the new findings of his research into the subject.

The eight sections of the spring exhibition are devoted to different regions, as well as to the genres of photojournalism and fashion photography, to showcase the impact of Hungarian artists on American photography. Adding to the splendour of what is a very rich selection from the US – the joint work of American and Hungarian curators – the exhibits will include images held in Hungarian public and private collections, including works by Anna Barna, László Kondor, György Lőrinczy, László Moholy-Nagy and Nickolas Muray.

5 April | 2pm

Museum of Fine Arts

KERTÉSZ,

The exhibition is on view between

5 April and 25 August.

35

MOHOLY-NAGY, CAPA... Hungarian Photographers in America (1914–1989)

André Kertész: Lexington Avenue at 44th Street, New York

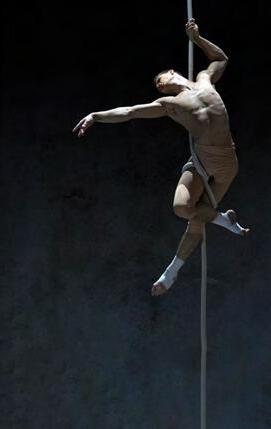

HOPE WILL NEVER DISAPPEAR

by Tamás Jászay

36

In many ways, the new production of the FrenÁk Company is about the encounter of the old with the new. Sitting down with the originator of the concept, Kossuth Prize-winning dancer and choreographer Pál Frenák, an artist equally at home in Budapest and Paris, we discussed Bosch’s paintings, artificial intelligence, cultural differences and identity change.

Let’s start with the beginnings and the background to the new show. What inspirations, models, texts and images led you and your team to its creation? The production is marked by new energies and a new creative approach since I’m working with a young multinational team that represents a new generation. We draw on, and are inspired by, each other’s energies and creativity. There is ceaseless cooperation between all of us, which is very productive. I’m always wondering what’s next.

Parad_Is_E is not a search for the original, biblical state. The millennia-old cultural-historical tale of Adam and Eve is replete with sentiments related to work, birth, sexuality, deception, weakness and credulity. Millions of Adams and Eves roam the world alone – and all this is a strong source of inspiration. We need each other, but it matters how we connect. What happens when artificial intelligence takes the place of common sense and spontaneous emotion? We’re responsible for this, because AI is programmed by humans, learns from us, and builds on our patterns. It begs the question of whether emotional development can keep pace with the technological innovation that holds the promise of boundless knowledge. Can we make good use of our access to knowledge while societies are in an agitated and turbulent state all over the world? Daily contemplation, films, music, paintings, the works of Deleuze, the philosophy of fragmentalism: these are my eternal sources of inspiration. It’s all research. The inspirations gain a new language and new forms, be they paintings by Bosch or images from the world of cinema. This is where dramaturg Nóra Horváth has a huge role in realising my concept, selecting precisely and articulating the parts and details that can give birth to something new, some sort of alchemy. We collect tons of material, ninety percent of which we do not use.

37

Photo: Róbert Hegedűs

It’s always very exciting to see how you translate ideas into bodies and movement in your works. You have a lot of new dancers in the company. Do you work differently with them than with your older colleagues?

I work with dancers of such strong character as David Leonidas Thiel, soloist with the Dresden Frankfurt Dance Company, and Italian dancer Zoe Lenzi, who also dances in Germany. Léna ÁrvayVass and Gergely Cserháti are also making their debuts with my company. Gergely, for example, brings classical ballet school skills, while Balázs Buda contributes his acrobatic experience and aerial work to the choreography. The energies of cultural and language differences are very important. Eoin Mac Donncha, a splendid Irish dancer, is a long-time member of my company. His 'crazy runner,' a figure with a god delusion, dominates the entire show. The overall concept emerges from the individual creative efforts of five or six people. They create individually, but not independently of each other; they work within the unit, within a given framework. There is a crazy, theatrical part of the performance, almost like physical theatre, while the technique of movement we use is very powerful and organic.