6 minute read

Medical books published in Bruges

Ludo Vandamme

Books are a mirror of society. In this essay, we offer a brief survey of the books produced by the medical world in Bruges in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Without seeking to be exhaustive, we look in turn at medical astrology, work by surgeons and physicians, and government publications. The focus is on both the work of locally based authors and the medical output of printer-publishers. The publishing business in Bruges was modest in the centuries in question and so authors in the city frequently entrusted their texts to printers in Antwerp or abroad. Sixteenth-century book production in the Low Countries was recently estimated at about 30,000 editions, of which Bruges can lay claim to barely a hundred. The situation did not differ much in the seventeenth century.

Advertisement

Almanacs and astrological forecasts were the tool par excellence of practical medicine. The astrological calendar was crucial to surgeons when it came to performing (pseudo-)medical procedures like bleeding, cupping and administering medication. It is quite possible that almanacs were published each year in Bruges in the final quarter of the fifteenth century, but no such material has survived. All we know is that Colard Mansion – a printer who was active in Bruges between 1476 and 1483 – published an almanac in French for the year 1478. Fragments of a copy turned up in the nineteenth century, but subsequently disappeared again without trace.

Bruges physicians were particularly assiduous in composing astrological forecasts in the sixteenth century. Pieter Bruhesius (died 1571), the municipal physician, was responsible for the official almanac, which other local physicians like François Rapaert (died 1587) and Cornelis Schuute (died 1580) condemned as unscientific. Rapaert responded with his own eeuwigen almanach (‘perpetual almanac’, 1551), while Schuute championed the annual forecasts that he published himself. Whatever the case, doctors in Bruges did not have their forecasts published – whether in broadsheet or book form – in their own city, but in Antwerp. It was not until well into the seventeenth century that regular almanac production got under way in Bruges. The earliest surviving example – and another one-off – is the Oprechten Vlaemschen tydtwyser (‘Honest Flemish Almanac’) for 1683. The medical instructions are still there, although the compiler is no longer a physician but a mathematician.

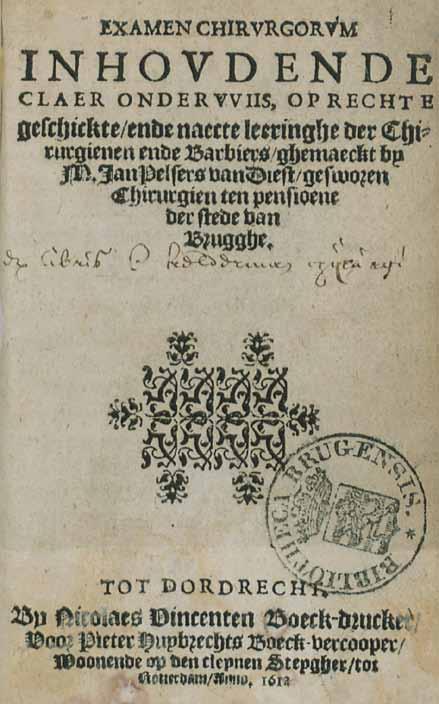

Surgeons were firmly rooted in practice, and so their publications take the form of training manuals and concrete guidelines on dealing with epidemics in the city. One excellent surgical manual is Examen chirurgorum by Jan Pelsers (died 1581). He also addressed his fellow practitioners – chirurgienen ende barbiers – in the vernacular. That book was published in 1565 by Hubertus Goltzius’s private press: part of a humanist circle in which Pelsers clearly felt at home. A new edition subsequently appeared in the Northern Netherlands in the seventeenth century (Fig. 15).

Pelsers drew on his many years of expertise as a ‘plague master’ in Bruges for his volume Van de Peste (‘On Plague’), which Pieter de Clerck published in 1569. The plague books of the

15 Jan Pelsers, Examen chirurgorum (Dordrecht, 1612), with provenance from Cornelis Kelderman. Stedelijk Openbare Bibliotheek Brugge ‘De Biekorf’ inv. 2/536c Title page surgeon Gheeraert van Kuck are older, but he gained his experience of the disease in Spain in 1518, within the entourage of Charles v. It was only later that he worked as a surgeon in Bruges, which he continued to do until 1531. His twin plague treatises were published in Antwerp later still, perhaps posthumously. Despite the changes in the city’s fortunes, Van Kuck was still described as ‘a surgeon of the celebrated trading city of Bruges’. Outbreaks of plague in Bruges continued to prompt books of this kind in the seventeenth century. It was a physician for once, Thomas Montanus (died 1685), who in 1669 turned his journal on combating the plague of 1666 into a comprehensive Latin treatise entitled Qualitas loimodea sive pestis Brugana, published in Bruges by Lucas vande Kerchove.

Bruges-based printers continued to publish work by local surgeons – compact, practical books in Dutch. A typical example is Het Kortverhael van den loop soo vanden chyl als ’t bloet (‘Concise Account of the Flow of Both Chyle and Blood’) by the surgeon Pieter Lanbiot (died 1728), published by Pieter van Pee in 1688. In it, Lanbiot offered ‘the fruits of seventeen years obtained with the dissecting knife and gathered together’.

In its rise to the status of a critical, ‘modern’ science during the sixteenth-century Renaissance and the seventeenth-century scientific revolution, medicine made very little use of the publishing industry in Bruges. All the same, the city was not entirely unemployed. Cornelis van Baersdorp (died 1565) from Bruges and Willem Pantin (died 1583) from Tielt practised medicine out of a broad, humanist interest, with considerable respect for Galen and other ancient auctoritates. Van Baersdorp’s Methodus universiae artis medicae offered a general introduction to Galenic medicine. The Bruges printer Hubrecht de Croock published it in 1538 – the first medical book to be printed in Bruges. Van Baersdorp was active in the years in question as a personal physician in the entourage of Emperor Charles v and his family, before settling permanently in

16

16 Cornelius Kelderman, Midwives’ training manual. Stedelijke Openbare Bibliotheek Brugge ‘De Biekorf’, inv. B 57 Title page

Bruges. In 1551 Pantin was appointed physician to the city. He produced a meticulous and thoroughly annotated edition of De medicina – Aulus Cornelius Celsus’s first-century medical treatise, for which he turned to Johannes Oporinus in Basel (1552), one of Europe’s leading printing works.

The ‘new’ medicine went further, however, than the critical study of examples from antiquity. Vesalius and his anatomical study (De humani corporis fabrica libri septem, 1543) set out the possibilities of empirical research. The Fabrica’s influence was immense, not least through Vesalius’s own manual (Epitome). The Bruges physician Maarten Everaert and Jan Wouters (died c. 1597) – a young doctor working in the Zeeland town of Veere – independently produced Dutch translations of the Epitome. Everaert worked on behalf of Christophe Plantin in Antwerp, who published the book in 1568. Wouters had to make do a year later with Pieter de Clerck’s more modest press in Bruges. Jan Pelsers, to whom Wouters dedicated his translation, is likely to have been behind this Bruges connection.

The scientific revolution gathered momentum in the seventeenth century. Bruges physicians translated the new insights into a mechanistic, Cartesian image of the human body for a wide audience. Robert Maes (died 1700) did so in his Tractaet van de voortkomste ende generatie des mensch (‘Treatise on the Origin and Generation of Man’, published by Jan de Grieck in Brussels, 1689). Robert Maes and several others of his Bruges colleagues engaged uninhibitedly in the battle against bleeding and other traditional medical practices, which doctors were now keen to consign once and for all to the past. The vernacular work did, however, find its way to a printing press in Bruges.

Throughout the period, Bruges’s civic authorities kept a close eye on public health and the medical sector in the city. The ordinances and by-laws laying out this policy in concrete terms – especially during plague outbreaks – were increasingly disseminated in printed form in the seventeenth century, to which end local printers were naturally used. The same goes too for the more comprehensive works in which the magistrates were involved. Examples dating from 1697 include the midwifery textbook (Onderwys voor alle vroedvrouwen) by the Bruges municipal surgeon Cornelis Kelderman, printed by Ignatius van Pee (Fig. 16), and the Bruges pharmacopoeia (Pharmacopoeia Brugensis) by Johannes Vanden Zande, printed by Christoffel Cardinael.