16 minute read

Care of citizens in sixteenth and seventeenth-century Bruges

Hilde De Br uyne

from the beginning: a survey The rise of the Flemish cities in the twelfth century prompted a population increase that intensified social divisions. The first care initiatives for the needy – preferably their own impoverished fellow townspeople – were taken by the burgher class and the civic authorities. Hospitals – hospitalen, gasthuizen or godshuizen – were founded, the earliest known example in Bruges being Sint-Janshospitaal. This first offered shelter to the sick – but above all to the needy, travellers and pilgrims – around 1150. Wealthy burghers could even opt for lifelong admission as pensioners in return for their possessions. For the most part, however, poverty was the driver. The Heilige Geesthuis certainly existed in 1231, but is likely to have been caring for the poor in their homes even earlier than that.

Advertisement

Leprosy was considered contagious and incurable and so sufferers had to be removed from the community. The Magdalenaleprozerie is first recorded in 1227, but had been caring for lepers (Fig. 9) for years by then. The patients admitted to the Magdalena were well-off burghers. Poor lepers, who were also citizens of Bruges, formed a guild. They lived beyond the city walls but still within its legal jurisdiction. The authorities ordered them to move in the fifteenth century to four plots of land, also outside the city, earning them the name Akkerzieken (‘field sick’). They were permitted to beg. The Hospitaal Onze Lieve Vrouw ter Potterie was in operation by 1276 and, like Sint-Janshospitaal, took in verweecten (the weak), travellers and sick people. It merged with the Heilige Geesthuis in 1300.

Additional institutions began to arise in the fourteenth century for specific target groups, including passantenhuizen for pilgrims, pedlars and travellers, though they were more likely to house the homeless. They were all provided with a night’s free accommodation, sometimes accompanied by a meal. Houses of this kind were mostly located on the outskirts of the city, on one of the main roads. The Sint-Juliaan house was founded in 1305 by order of the civic authorities and represented the merger of the Guild of St Julian and the Filles-Dieu. The latter was a house dating from 1290 founded as a refuge for former prostitutes in an effort to rein in the sex trade. Sint-Juliaan could accommodate hundred ‘travellers’ in this period. The rules governing passantenhuizen were tightened in response to the growing number of homeless people. Their raison d’être was sharply reduced therefore by the end of the sixteenth century. Several former hospitals, including the Sint-Joosgodshuis, evolved into passantenhuizen. Travellers continued to be received by major institutions until the end of the French period.

In the early fifteenth century, the Hospitaal Onze Lieve Vrouw ter Potterie developed into an old people’s home for both men and women in need of care. Eighteen elderly women lived there in 1671 and the institution continues to fulfil its ancient function today. The Sint-Hubrechts

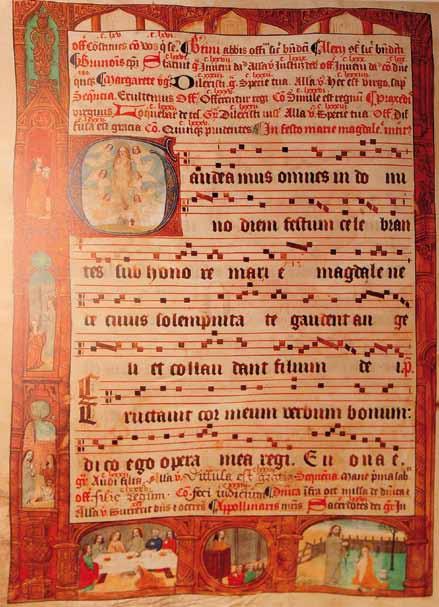

9 Gradual from the Magdalenaleprozerie. Decorated initial with the image of Mary Magdalene and scenes from her life in the margins, Ghent, 1504.

madhouse was founded by the civic authorities in 1396–97. It housed not only dangerous mental patients but also unplaced foundlings and abandoned children. At first it was laymen and women who administered the different institutions. In the fifteenth century, the brothers and sisters at Sint-Janshospitaal and the Hospitaal Onze Lieve Vrouw ter Potterie adopted the Rule of St Augustine and became a canonical community. Sint-Juliaan and the Magdalenaprozerie were run by lay brothers and sisters, although the rules in operation at Sint-Juliaan resembled those at Sint-Janshospitaal.

Godshuizen or almshouses had certainly begun to appear by the early fourteenth century. Founded by private initiatives or by crafts or guilds, they were intended to care for needy, elderly citizens. They were the only foundations to spread significantly in the centuries that followed. A remarkable number of almshouses were established in the fourteenth and seventeenth centuries. Forty-two foundations, now disappeared, have so far been identified in the archives, some of which were guild almshouses. The almshouse complexes that remained at the end of the ancien régime certainly comprised 360 dwellings, of which 45 survive today, still mostly fulfilling the same purpose.

A first armendis or ‘Poor Table’ appeared in 1269. These were charitable organizations that provided poor people with material support in their homes, their territory coinciding with that of the parish. Dissen continued to operate in Bruges until as late as 1925. No facilities were provided for the large group of poor people who were not citizens. One new initiative after another was launched over the centuries to restrict begging, but without success The ideas on centralizing poor relief expressed by the Spanish-Bruges humanist Juan Luis Vives in his 1526 publication De Subventione Pauperum were made law through a decree of Emperor Charles v in 1531. The measures were also intended to reduce begging. The key institutions, including Sint-Janshospitaal, were required to pay substantial sums into the coffers of the Gemene Beurs (‘common purse’) – a central poor relief fund that continued to operate in the centuries that followed. The city used it to pay for things like the subsistence of fostered foundlings, the mentally ill and sick poor people. A number of cities succeeded in centralizing their care initiatives, but this was not the case in Bruges.

sixteenth and seventeenth centuries: poor relief, care for the sick? Sint-Janshospitaal, Sint-Juliaan, the Magalenaleprozerie and Onze Lieve Vrouw ter Potterie remained important care institutions in these two centuries (Fig 10.). Sint-Jan, Sint-Juliaan and the Magdalenaleprozerie admitted sick people. They performed other functions too.

The city’s burgomasters and aldermen declared in 1569 that Sint-Janshospitaal had been founded to accommodate the sick, the injured, beggars and travellers, from wherever they happened to come. They were to be given a bed, food, care and ‘succoured with medicine and surgery’. Sick people could remain until they had were healed. The ordinance basically reiterated the institution’s mission, with the difference that victims of infectious diseases (most notably plague) were now accepted too. The stipulation that it made no difference where

10 people came from did, however, conflict with the general trend and with later regulations that sought to reserve assistance for Bruges residents, this primarily for financial reasons. The hospital by-laws drawn up in 1598 and approved by the city also specify that the sisters and brothers were to serve the sick and the poor.

Internal regulations on matters like the quality and quantity of food or hygiene (Fig. 11) have not survived, and so our knowledge of the functioning of the hospital is fragmentary. Most of what we know is based on the hospital accounts. Both men and women were admitted, apart from pregnant women about to deliver. Children were there too, as were soldiers during wartime and foreigners suffering from acute illness. The number of travellers fell off sharply from the sixteenth century. From around 1600, mental patients had to seek refuge in institutions including Sint-Juliaan and were no longer admitted to Sint-Jan. Admission was normally only possible with a certificate from the armendis or the parish priest. Day-to-day figures for the number of sick people are hard to come by. The occupancy rate in 1547–48 was seventy and the hospital employed twenty staff members for hundred beds until the end of the eighteenth century. After the brothers had left, the mevrouwe took over from the master of the institution. She submitted the accounts prepared by the receiver to the civic authorities and reported to the bishop. There were between twelve and fourteen nuns in 1573. The major building work carried out during the two centuries in which we are interested comprised the construction of the convent (1539–1685).

The rekezusters were present on the wards both night and day, admitting patients, helping them undress, caring for the sick and injured, providing a bed to travellers and the needy, distributing food, washing the linen and keeping watch. They also offered their support during a patient’s final hours, when they assisted the priest. They helped bury the dead in the hospital cemetery. There was a spindezuster, the 10 Loving cup with the emblems of Sint-Janshospitaal, Onze Lieve Vrouw ter Potterie, Sint-Juliaan and the Magdalenaleprozerie, the Bruges municipal arms and the city’s crowned capital B symbol. Around the edge the motto Eendracht mackt Maecht (‘unity is strength’), Bruges,1664. Memling in Sint-Jan – Hospitaalmuseum Bruges

11 Detail of dresser with view of the ward at Sint-Janshospitaal, Bruges, 1678, Memling in Sint-Jan – Hospitaalmuseum Bruges

deputy head of the community, and a female sacristan. The hospital priest provided pastoral care, which was still more important than health care. Four male servants or rekeknapen and a maid were also employed on the ward. The tasks performed by the medical staff are not specified, although payments and the names of surgeons and doctors appear in the accounts. Surgeons and barbers were attached to the hospital in the thirteenth century. The surgeon set broken bones, treated wounds, performed amputations and lithotomies, and otherwise eased patients’ maladies. Bleeding, meanwhile, was the task of the barber. A surgeon was paid in the sixteenth century for performing the same task. Physicians diagnosed – by examining the patient’s urine, for instance – and prescribed medication. The growing importance of a doctor’s presence in the hospital was a new feature. A salaried physician was attached to Sint-Janshospitaal from around 1600, and the number rose to two in the mid-seventeenth century. The sick now had to be visited and examined by a physician on a daily basis. At least two surge-

11

ons were attached to the hospital by the midseventeenth century. The names of well-known, innovative medical men appear in the archives. The role they played in caring for the sick at Sint-Jan can only be inferred, however, from the opening in 1644 of the hospital pharmacy and an operating theatre.

The organization of the main ward by gender remained the same throughout the centuries. There were no individual rooms, but the space was split into rows or reken, hence the references in the accounts to a mannereke, vrouwereke, noortreke, zuidreke and soldaetereke (men’s, women’s, north, south and soldiers’ row respectively). There was also an infirmerie for men and one for women, and a doothouc (literally ‘death corner’). Each row comprised an ambacht with its own linen and equipment. The ‘mistress’ was responsible for the linen stock.

Like so many other churches and chapels, the hospital chapel was refurbished in the Baroque style in the seventeenth century, although it remained, according to the medieval principle, an open space visible to the sick. The chapel was not closed off until the nineteenth century. View of the Old Wards, which the Bruges artist Johannes Beerblock, painted around 1778, depicts the unchanged life at the hospital at the time. It was poverty rather than ill health that drove people to the hospital, with exceptions including the wounded who came to Sint-Jan for the medical care it offered.

Leprosy was present for centuries in Flanders too, although there are few local sources describing the disease and its treatment. It was considered to be highly contagious and so people designated as lepers were no longer permitted to take part in the life of society. They were placed in a leper colony or shared the lives of the Akkerzieken. The incidence of leprosy began to decline steeply in the sixteenth century, and by the beginning of the seventeenth it had all but disappeared. The Magdalenaleprozerie was located beyond the city walls. This first leper hospital in Bruges is shown in several sixteenth

century maps. It was situated at a distance from the city, between Boeveriepoort and Smedenpoort, and separated from it by a watercourse. There was accommodation for the brothers and sisters, the church, the priest’s house, utility buildings and, as at other leper hospitals, small, individual leper houses. The latter were built in a row, separated by a small garden wall, and had front and back rooms. The total number is not known. The lepers had their own chapel and well, and their dead were buried in a separate cemetery.

The governors – representatives of the civic authorities – took most of the decisions and managed the hospital’s affairs. The lay community comprised the master, the receiver and lay brothers and sisters, who were well-to-do burghers. The master was appointed by the city council. He was responsible for the orderly running of the institution and for day-to-day purchases. To qualify for admission to the Magdalenaleprozerie, the patient had to be a welloff citizen and to have officially been declared a leper. Patients could also pay for admission, in return for which they received board and accommodation. When they died, their immediate possessions and a substantial part of their estate was inherited by the institution.

The old leper colony was demolished in 1578 for military reasons, at which point it relocated to the city centre, in part of the Onze Lieve Vrouw van Nazareth complex – a fourteenthcentury passantenhuis on Garenmarket. The foundations were merged by deed in 1590, with the master of the Magdalena taking charge of the ‘comfort of the poor’. The names of the two institutions were preserved and both appear separately in the general annual accounts. The hospital continued to receive lepers, travellers and other gasterie ‘in separate places as far apart as possible’. The deed indicates that there were no longer many travellers or paupers. The leper hospital restored the existing chapel and houses of the passantenhuis staff. The 1617 accounts record payments for the construction of a new hospital wing. The same date can be seen in the anchor plates in the wall of the surviving building, alongside the fifteenth-century chapel on Nieuwe Gentweg. The Akkerzieken also settled inside the city in 1578 for the same reason, taking up residence in a house on Oude Gentweg. Only six of them were left in 1572 and the last one died in 1618.

The Magdalena was one of the three principal leper hospitals in Flanders, together with those in Ghent and Ypres. They each had the task of monitoring the presence of leprosy within a clearly defined area. Inspections to certify who was and was not suffering from the disease were performed in Bruges by the master, the brothers and the sisters, who were paid for these visitaties. It is not clear whether a doctor or surgeon was also present in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. The record of these examinations for the period 1520–55, kept by the master, states the potential leper’s name and address and then the bald conclusion ‘healthy’ or besiect (‘infected)’. The basis of the diagnosis has not been found in either the institution’s rules or the municipal by-laws, unlike in Ghent. The aforementioned sixteenth-century register – seemingly the only one to have survived – records a total of 2,464 examinations over a 35-year period, 23.5 percent of which resulted in diagnosis as lepers. Of these, 139 of the patients were Bruges people. Admittance to the leper hospital was made official by a certificate issued by the civic authorities and was conditional on the patient being free of debt. The Akkerzieken were also subject to examination and municipal certification.

There were an average of 21 patients at the Magdalenahospitaal in the period 1530–39. Leprosy cases began to decline in the midsixteenth century, so by the time the institution relocated in 1578 there were only ten remaining lepers. It was not until the accounts for 1741, however, that it was recorded that no lepers were residing any longer at the Magdalena. The hospital’s importance thus having diminished, it was given a new municipal function in the eighteenth century, becoming a house of correction in 1752, although its tasks still included accommodating travellers and the occasional leper. The Magdalena was closed down during the French period.

Toward the end of the fourteenth century, the city purchased a house on Boeveriestraat to care for a small number of mentally ill people who posed a danger to society, and for unplaced foundlings and abandoned children. A set of rules for Sint-Hubrechts, as the institution was known, was drawn up by the civic authorities in 1596 and states that the madhouse was run by a warden or concierge under the supervision of the city and at its expense. His task was merely to oversee the patients who were poor citizens of Bruges, designated as such by the city. The warden was responsible for locks and shackles ‘that the aforementioned might not break out’, for cleaning the cells and replenishing the straw. He was to feed them three times a day with bread and butter and thick soup (potage). The city paid for the patients’ clothes and for wood to heat the house. The warden was also required to accompany the patients and the children in the Holy Blood Procession. The institution was financed through foundations and collection boxes set up at important locations like the entrance to the Basilica. It was supervised by the master of Sint-Juliaan. The same rules defined the status of foundlings and abandoned children. They were children whose parents were unidentified; otherwise every effort had to be made to reunite the child with them. The warden’s wife was responsible for their care.

The residents of Sint-Hubrechts ten Dullen – five paying guests, mental patients, were transferred in 1600 to Sint-Juliaansgasthuis, which was located on the opposite side of Boeveriestraat. The Sint-Hubrecht buildings came into the possession of Gerard and Herman van Volden, who established an almshouse in them in 1614. Sint-Juliaan adapted its buildings,

erecting two dulhuusekens (‘madhouses’). The aldermen stated in their ordinance of 1600 that they retained ultimate authority over Sint-Julian and that the hospital was to ‘receive and lodge all needy travellers and pilgrims, men, women and children.’ Sint-Juliaan was also charged with the care of the mentally ill poor citizens – both men and women – , foundlings and abandoned children. The lay community was not to exceed seven brothers and sisters and responsibility lay with the master (Fig. 12), who was to supervise and administer the institution. The admissions procedure specifies that the master was to examine the mentally ill people: the document makes no reference to a doctor or surgeon being present. The patients’ financial situation was also examined. The master wrote a report and submitted it to the city council, which then took the final decision. Patients with less acute conditions, which was the majority, could be tended at home, for which they received an allowance. They could also be admitted to a non-municipal institution or placed in Sint-Juliaan. The master was to receive the sick ‘with all compassion and sympathy’ and was to take care of chains and locks. Their food was to be the same as that given to other residents. In the event of a cure, following examination by the governors and the clerk of the municipal court, all the patient’s possessions passed to Sint-Juliaan. The same ordinance specifies that all foundlings and abandoned children were to be fostered. It was the master’s duty to arrange this and to inspect the new home, with the council giving permission for the placement. Funding was provided by the Gemene Beurs. It was chiefly widows who took in one or more children. Some of them attended the school for the poor, while others were set to learning a trade.

There were seventy-six fostered foundlings and abandoned children in 1654. A total of fiftheen sick people were admitted in 1610, which is a high number given the target of eight. An average of nineteen mental patients were resident at Sint-Juliaan between 1654 and 1674. The number rose in the course of the eighteenth century.

It was only toward the end of that century that salutary care for mind and body gradually developed into health care as such, as clearly reflected in hospital life. The development of medicine only began in earnest in the mid-nineteenth century.

Anonymous, Portrait of Jan De Herdt, Master of Sint-Juliaan. Detail with view of the former SintJuliaanshospitaal, Bruges, 1650.