13 minute read

Two centuries of innovative ideas and barely changing medical practice

Ludo Vandamme and Johan R. Boelaer t

The ‘new’ world of the sixteenth century spanned the globe for the first time. World trade shifted with it from the Mediterranean to the Atlantic space, while large, centrally governed global empires became laboratories of modern state thinking. The most powerful of these was the Spanish Habsburg empire on which ‘the sun never set’ and to which the Low Countries also belonged.

Advertisement

Not only had the world changed, above all people viewed it differently: it became a world of and for the people. This immense interest in human beings and in humanity found its purest expression in humanism – a broad intellectual movement that spread from Italy throughout Europe, achieving a widespread social and religious impact. Critical thought now began to reject slavish adherence to established commentaries on the supposed sources of knowledge, the auctoritates. Humanists wanted to examine these authorities at first hand. They feverishly sought out authentic sources from antiquity and early Christianity ad fontes: the Bible, of course, but also Justinian, Galen, Plato and Aristotle, among many others. Language and art were also tested against the idealized image of antiquity. Some wanted to go even further, to build a new, ideal society, although they did not get much further at this point than the blueprint Thomas More set out in his Utopia. Humanism owed much of its dynamism to the art of printing, which for the first time allowed texts to be produced and distributed quickly and affordably, enabling new ideas, insights and convictions to be picked up immediately among scholars or shared by large swathes of the population. Without the book printers, Protestantism would never have developed into a mass movement that brought about a permanent schism in the Western Church. Bruges, with its 30–40,000 inhabitants, was the metropolis of the ‘old world’, no longer a hub of the new, global economy. That role passed to Antwerp, whose population grew rapidly in the sixteenth century to around 100,000. Nevertheless, Bruges remained a compelling, international city, with lively trade, diverse and high-quality manufacturing, and a sophisticated intellectual life. Erasmus of Rotterdam (1466?–1536) described Bruges as the ‘Athens of the North’, and while the celebrated Dutch humanist could always be relied on for a bold statement, there was something in his claim. Erasmus had many friends and kindred spirits in Bruges, and even considered setting permanently in the city.

Bruges’s fine manners, sociability and concern about the urban community made life there very pleasant: there was more to humanism, after all, than just the exploration of ancient wisdom in

scholars’ studies and libraries. Education and upbringing were, moreover, the key to preparing young people for this new world – a responsibility of which the Bruges-based Spanish humanist Juan Luis Vives (1493–1540) indefatigably reminded the civic authorities and parents. The driving force behind humanist intellectual life remained, however, the pensionaries and administrative circles centred on Bruges’s town hall and the canons and other clerics in the chapters: that of Sint-Donaas chief among them. Within these circles, the latest books passed readily from hand to hand. The city’s commercial star had waned too much for it to develop a vigorous book trade. Likewise, attempts to add an academic superstructure to the network of Latin schools got little further than the foundation of a ‘Collegium Bilingue’ (1540) for the study of Latin, Greek and theology. From the second half of the sixteenth century, moreover, humanist intellectual life was increasingly harnessed as an instrument for monitoring religious orthodoxy. This trend continued in the seventeenth century, when the triumphalist Catholic Counter-Reformation came to dominate artistic and intellectual life in the cities.

A ‘new’ world had opened up in the sixteenth century, in which human beings seemed capable of achieving anything. This optimism soon found itself constrained, however, by physical and intellectual restraints. Marguerite Yourcenar powerfully captured this struggle against the prevailing restrictions in the person of Zeno, the main character of her novel The Abyss. Is it a coincidence that Zeno the physician transports us back into the medical world of sixteenthcentury Bruges? What drove medical thinking before it took a new turn under humanism? Medieval ideas about health and illness rested on three pillars: Hippocratic Galenism from antiquity, astrology and Christian scripture. Hippocrates, medicine’s founding father in the fifth century bce, and his successor, Galen, in the second century ce, established a doctrine based on harmonious relationships within the universe, and especially between man and the four primary elements of the universe: earth, water, air and fire. The human body was composed of four corresponding principles: the four bodily fluids or ‘humours’: black bile, phlegm, blood and yellow bile. Health was defined in terms of a harmonious balance between these four humours, while illness was attributed to the disruption of the same balance, which treatment therefore sought to restore. The second pillar consisted of astrology, which had its roots in the same ancient philosophy of harmony between man and the universe – the macrocosm and the microcosm. This theory highlighted the favourable or unfavourable influence of heavenly bodies on the human body. Treatments such as bleeding therefore had to take account of the position of those heavenly bodies, particularly the planets and the constellations of the zodiac. The third pillar was Christian doctrine, which interpreted disease as God’s scourge to punish humanity or individuals for their wickedness. This was counter-balanced by Christ’s healing of the sick, and the care shown towards invalids by numerous saints and their miraculous cures.

The fresh wind of humanism began to shake the dogmas of Hippocratic Galenism, revealing certain gaps and errors and, as the early modern period dawned in the sixteenth century, causing the first cracks to appear in the two-millenniaold system. Few went as far as the German scientist Paracelsus, however, who publicly burned the writings of Galen as a token of his contempt for the established scholarly tomes. Such iconoclastic behaviour was the expression of a quest for a new vision toward medicine. While Paracelsus himself was unable to achieve that visi

1 Andreas Vesalius, Compendiosa totius Anatomie delineatio, …. 1545. Bibliothecae Dunensis 1758 Stedelijke Openbare Bibliotheek Brugge ‘De Biekorf’, inv. 2322 Pagina met ‘quarta musculorum tabula’

2 Aurelius Cornelius Celsus, De Arte Medica libri octo, multis in locis iam emendationes longè, quam unquam antea, editi, 1552. Bibliothecae Dunensis 1629 Latin translation of Celsus’s book, done from the Greek by Willem Pantin of Tielt, who practised medicine in Bruges. Stedelijke Openbare Bibliotheek Brugge ‘De Biekorf’, inv. 2299 Titelpagina

on, he nonetheless introduced chemicals, including minerals, into therapy. Johan Baptist van Helmont, who came from the Duchy of Brabant, emphasized the importance of chemical processes in the body. Andreas Vesalius, also from Brabant, was a pioneer in the field of structural anatomy, publishing his findings in an excellent work entitled De humani corporis fabrica (‘On the fabric of the human body’, 1543) (Fig. 1). An abridged version was published in Bruges with the name Dat epitome (1569). Vesalius had been able to perform accurate dissections of corpses, primarily in Padua, which enabled him to discover errors in Galen’s system, the anatomical knowledge of which derived from animal dissections. Anatomical research continued to develop in the seventeenth century, not only in terms of structure but above all in pursuit of functional relationships. Anatomical and especially physiological knowledge of the circulatory system was established in England by William Harvey (1628), refuting once and for all Galen’s assertion that the veins contained blood but that air flowed through the arteries. Humanism also brought new knowledge of infectious diseases. In 1546, the Italian Girolamo Fracastoro made a tentative yet visionary step toward the notion that ‘germs’ are the cause of infectious diseases rather than a disruption in the balance of the humours. The time was not yet ripe for this idea, however, and it would not be until the second half of the nineteenth century that this ‘germ theory’ was proved correct. Anthonie van Leeuwenhoek, using a selfmade microscope, nevertheless managed to observe ‘animalcules’ corresponding with what we now refer to as ‘bacteria’ in 1676. Did the humanist movement achieve any medical advances in Bruges too?

innovation The answer is that it did indeed. The innovation in question included the much-needed critique of the abuse of certain medical practices, broadening the study of nature, a more organized approach to infectious diseases and improved training and structuring of the medical professions. Several Bruges-based thinkers in the sixteenth century recognized the malpractices arising from the old belief in astrology’s role in health and disease. The aforementioned Juan Luis Vives challenged astrology’s status as a science, while various doctors, including Cornelius Duplicius Scepperus and above all François Rapaert, vigorously resisted the application of astrology for medical ends and the astrological predictions published in almanacs: ‘that one ought not to follow planets alone when curing diseases’ (1551). The number of health forecasts proclaimed by the almanacs gradually declined in response. In a similar display of rationalism, both Vives and Rapaert mounted equally firm resistance against the ubiquitous malpractices of the traditional healers, ‘the tyrannical murderousness of the charlatans’. Unsurprisingly, Rapaert also railed against the practice of uroscopy – the visual examination of a patient’s urine, which doctors applied for diagnostic purposes and which was frequently misused by quacks.

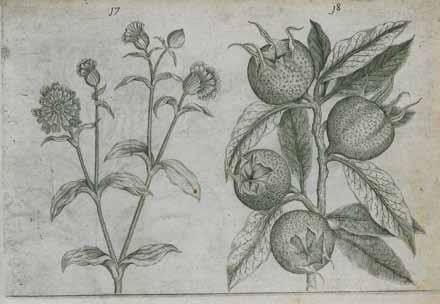

Innovation was not limited to the critique of abuses: in the mid-sixteenth century, several Bruges physicians published translations of works by the Romans Galen (1538) and Celsus (1552) and the Byzantine Actuarius (1554), facilitating a more thorough study of these ancient texts (Fig. 2). Another Bruges man, Anselmus Boëtius de Boodt is still celebrated for his thorough and wide-ranging study of nature. He spent time at the imperial court in Prague, where he focused on the study of rocks and precious stones. As a physician, he also described the medical uses of these stones (1604). He was not only interested in the world of minerals but also that of plants, publishing a herbal (Fig. 3) and producing excellent hand-coloured drawings of plants. Karel van Sint-Omaars, who commissioned artful, coloured drawings of the plants in the garden of his chateau in Moerkerke, is also worth mentioning in this regard. Less innovative but still worth noting is the 1697 Bruges pharmacopoeia by Johannes Vanden Zande, which followed the examples published by cities like Brussels, Antwerp and Ghent. The quality of medical training in Bruges made substantial advances in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries (see also M. Deruyttere’s article in this publication). In his 1531 book on the subject, Vives advised would-be physicians to study not only the ancient writers, but also botany and anatomy, the latter by attending dissections of the human body. This theoretical knowledge was to be supplemented by an

3

apprenticeship with an experienced physician. Vives also stressed the good conduct and ethics required of the physician. In 1540, Emperor Charles issued an edict imposing a legal requirement on physicians to undergo training at an accredited university. The training of surgeons was also evolving. During the same period, the Bruges surgeon Jan Pelsers compiled a textbook to prepare candidates for the surgeon’s and barber’s examination (1565). At the request of the Bruges civic authorities, he and the physician François Rapaert instituted anatomy lessons in the local prison, where the instructors were allowed to use the corpses of executed or otherwise deceased prisoners, ‘provided they do so discreetly’ (1561). Similar but less furtive dissections were held a century later in the caemer der chirurgie – an anatomical theatre, the instructors at which included the surgeon Cornelis Kelderman (1675). The 1517 charter of the barbers’ guild specified in great detail the rights and duties of its members. The midwives too were required to pass an exam (1551), reflecting the onerous responsibility associated with the task performed by these wise women, as physicians and even surgeons were rarely if ever called on to intervene in deliveries

and their possible complications. The surgeon Cornelis Kelderman later published a little book with practical guidelines for midwifery (1697). It goes without saying that the pharmacists too were unable to escape the regulation of the medical professions. Having clearly delineated their business from that of the grocers, they were required to take an examination to demonstrate their knowledge and ability (1582).

Not only were there greater guarantees in terms of training, the battle against infectious diseases and above all epidemics also became better organized in the sixteenth century. Like Erasmus, Vives argued that doctors ought to be involved more intensively in social medicine, a theme that would gain in importance in the centuries that followed. The duties of the municipal physician gradually expanded. He had an advisory role, was responsible for health care and oversaw the various groups of health workers. Surgeons were appointed as rode meesters (‘red masters’) during plague outbreaks (1530). In addition to preventing and diagnosing cases of plague and treating its victims, they were responsible for diagnosing suspected cases of leprosy. Greater cohesion was sought in the seventeenth century between the different groups of health workers: between individual physicians; between physicians and other health professionals; and between the medical profession in general and the authorities. Just as the surgeons had united in the Middle Ages in the guild of Saints Cosmas and Damian, the physicians – under the impulse of Thomas Montanus – now came together to form a disciplined group in the shape of a Confraternity of St Luke (1665). The foundation (1603) of the Camer vande gesondheyt (‘Health Chamber’), comprising the burgomaster and alderman, together with two physicians and a surgeon (1625), extended the scope of the functions hitherto performed by the municipal physician. Montanus attempted to group all of Bruges’s medical professions but without success: it was not until the mid-eighteenth century

3 Anselmus de Boodt, Florum, Herbarum, ac fructuum Selectiorum icones, & vires pleraeq[ue], hactenus ignotae, Bruges, 1640 Stedelijke Openbare Bibliotheek Brugge ‘De Biekorf’, inv. 2/611 Page 17-18

4 Petrus Smidts, Waerachtigh verhael Raekende eenen steen, die een man ghelost heeft, weghende vier onsen ruijm Medicinael ghewight, …, Bruges, 1698 Stedelijke Openbare Bibliotheek Brugge ‘De Biekorf’, inv. 7/295 VARIA Titlepage

5 Junius De Pre, Oprechten Vlaemschen Tydt-wyser ofte almanach, Bruges, 1683 Stedelijke Openbare Bibliotheek Brugge ‘De Biekorf’, inv. B 226 Titlepage

toad for their supposedly protective or curative value in the face of the epidemic. Surgical treatment did advance somewhat, but it remained limited in the seventeenth century to external interventions. Exceptions included the removal of bladder stones or ‘cutting for the stone’ (Fig. 4) (see J. J. Mattelaer’s article in this book), and a total of six leg amputations in seventeenthcentury Bruges. Despite the rational approach adopted by Rapaert and Vives, belief in astrology remained deeply rooted (Fig. 5). Worse still, superstition and witch trials were rampant. In one instance, Bishop Triest forbade Bruges’s physicians to visit a seriously ill man whom he suspected of ‘the contagious disease of heresy’, unless the patient first went to confession and took communion. It is plain from these examples how dark and difficult social attitudes still were in the two centuries in question. All the more reason, therefore, to admire those voices in the Bruges of that time who called for renewal.

that a Collegium medicum of this kind actually arose.

stagnation in medical practice While there was a great deal of innovation in the field of medicine in Bruges in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, little progress was made compared to practice in previous centuries as far as actual diagnosis and treatment were concerned. Hippocratic Galenism, with its doctrine of the humours, continued to set the standard for physicians’ practice. The population at large – certainly in the countryside – had more to do with barbers and all manner of quacks and charlatans than with learned physicians or practically trained surgeons. The diagnostic tools available to the physician remained largely limited to the superficial and highly subjective determination of body temperature; evaluating the pulse; and visually examining the patient’s urine. Any advance in medical treatment was rendered difficult by the fact that the distinction between symptoms and disease had yet to be effectively defined, while it was not until the end of the nineteenth century that the cause of infectious diseases was linked to microorganisms. In his 1669 treatise on the plague, for instance, Montanus continued to praise amulets made of precious stones and extract of

5