76 minute read

textos em Inglês

Texts in English

Art and devotion : Beauty and the Paulista Faith The Casagrande Collection holds a great quantity of Paulista (from São Paulo) sacred art pieces that generate and impart precious beauty and information, not only about the history of São Paulo, but also in regards to the cultural context in which they were created.

Advertisement

The collector’s aim is to make the works he preserves accessible to many different publics in an effort to arouse interest, especially in São Paulo’s cultural roots. It is here that the importance of this remarkable collection lies, in its collecting of oratories and paulistinha saints (little clay saints made in São Paulo), the first artistic manifestations of São Paulo´s Sacred Art.

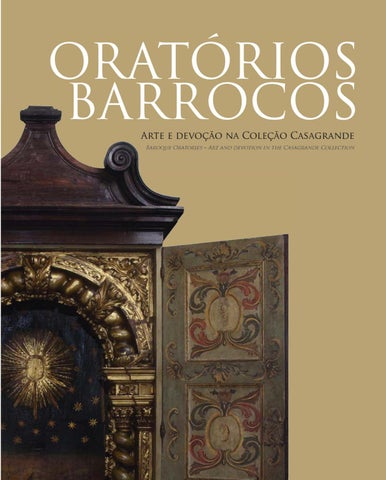

The Collection Baroque Oratories – Art and devotion in the Casagrande Collection, the Museum of Sacred Art of São Paulo´s third temporary exhibit in 2011, demonstrates with this collection the importance of sacred art of great artistic, historic and cultural content.

Andrea Matarazzo State Secretary of Culture

The Nobleness of Faith It is with great satisfaction that the Museum of Sacred Art of São Paulo realizes the exhibit Baroque Oratories – Art and devotion in the Casagrande Collection, with the intent of encouraging dialogue with the publics that visit it, awakening in them the splendor of art and, through it, the faith of the people.

The collection’s great merit in this third Temporary Exhibit of 2011 is in its interlacing of History, Culture and Faith, presenting a collection of great national relevance, with thirty rare oratories and images from the 16th century, Paulista objects from the 17th century and others from the 18th, from various regions, all of excellent esthetic quality and inner beauty. Especially notable are the Paulista and travel oratories, the latter dating back from the late 16th century, when the Bandeirantes began opening the wilderness in the Land of Santa Cruz (first name of Brazil).

Furthermore, each piece brings in its paunch the historical memory of its moment and the highest expression of the Brazilian people’s spiritual roots. By means of these oratories the nobleness of faith was nourished in the most distant places of Brazil, constituting not only an artistic and cultural heritage, but also a vehicle for communication and preaching the Gospel. These oratories gave origin to the appearance of the faith-healers in the wilderness, from which many cultural and religious traditions flowed and remain to this day at the heart of our culture.

The Casagrande Collection therefore constitutes a great secular wealth for us, through which we may go back to our ancestors to recover the historical, cultural and, above all, religious memory in our present time, so stigmatized by the indifference in relation to the transcendent. José Roberto Marcellino dos Santos, President of the Board - MAS-SP

Baroque Oratories – Art and devotion in the Casagrande Collection The exhibit Baroque Oratories – Art and devotion in the Casagrande Collection assembles nearly fifty oratories and an equal number of images. The Baroque oratories from the colonial period, coming from many different collections in the states of Pernambuco, Bahia, Minas Gerais, Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo, were gathered from manor houses and farms, and so always privately owned.

The exhibition in the Museum of Sacred Art of São Paulo follows, as much as possible, the chronology and typology begun by a small church oratory in Pernambuco – of the national Portuguese style – reaching the exhibit’s high point with a similar one from Minas Gerais – in the rococo style. The Paulista drawing room oratories, with Iberian woodcarvings, are the oldest and the most austere. The ones from Rio de Janeiro, delicate and fanciful, are from the D. José I and Dona Maria I periods. As to the alcove and nativity oratories, many of them hold their original saints. All the oratories, including the travel and convent ones, retain the devotional feeling of their use over centuries, expressed in the wear and tear of time and in material transformations, elevating them to the status of art.

The images in this exhibit were chose among many, favoring rare, mannerist, Paulista terracotta art works by the first Brazilian artist, Agostinho de Jesus. This line is completed with fragments and images from the school of followers of this 17th century Carioca (of Rio de Janeiro), Benedictine friar. Mary’s invocations in figures of the Immaculate Heart or Sorrows were privileged. Eighteenth century Paulista masters and the paulistinhas, from our imperial century, are displayed in the iconography of popular devotion.

Our eyes are privileged upon going through the history of Brazilian religious worship expressed in the art of the oratories in the Cristiane and Ary Casagrande Filho Collection. It is a relief to the soul that so rich a collection, built and preserved with the acute intuition of these young collectors, rigorous in their choices, can surprise us with the thematic of these devotional objects.

It is commendable that they have assembled these oratories of all typologies and now bring them to the public, along with the quality of the most well-known museum collections, such as the Angela Gutierrez collection, from the Oratory Museum of Ouro Preto (MG), an expert and pioneer on the subject, or the rich collection from the Museum of Sacred Art of Bahia, in Salvador (BA), with the best examples of small church oratories, abundant in paintings. And added to all this, the collection belonging to

the Collection of the Governmental Palaces of São Paulo and the Museum of Sacred Art of São Paulo, the latter with whom this unique private collection converses so well in this exhibit.

Percival Tirapeli, Curator

Dr. Ary Casagrande: a Collection Built with Passion and Charm Collecting in Brazil, especially since the last quarter of the 20th century on to our days, has, I’ve noticed, taken on a unique aspect in regards to the number of collectors. For diverse and different reasons we observe an enormous interest in the arts, especially contemporary, but the collector, in the vernacular term, has changed greatly, for today I see a great part of art acquired for mere speculation, awaiting for an immediate increase in value to be quickly placed on the market as a mere consumer object. But among so many buyers of art today we luckily still encounter sensibilities that fit into the term ‘art collector’, those who research, study, pursue the work of art they desire, to only then acquire it. And so they build, planning their cathedral we know will never be concluded, for the pleasure, the craving to collect, is always in the piece they have not yet acquired.

It is in this select group that we find the collection belonging to my dear friend Dr. Ary Casagrande. When I first came into contact with his passion I was surprised and enchanted, as much for the quality as for the quantity of the works under his care. The acuity and love with which my friend describes each piece in his collection make clear his love for the arts.

We now have the privilege of admiring oratories from the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries from his collection, treasures of sacred art. I therefore invite all admirers and lovers of good art to delight in the richness of this exhibit, which the Museum of Sacred Art of São Paulo so opportunely offers us.

Orandi Momesso, Collector

Paths Leading to the Building of the Collection We have already seen over 20 years of collecting. I still remember the day I acquired my first piece of sacred art. It was an Our Lady of Conception, about a palm high, a piece from Minas Gerais from the late 19th century, unpretentious when looked at from a more technical view, but a decisive influence in what was to happen. I bought it from a “catador”, a term used for those who recover sacred pieces in transepts, characters that over time have been gradually disappearing. Today, this catador, my dear friend nicknamed Zito, is no longer among us. However, he must be somewhat surprised with the evolution observed over these last two decades.

To dedicate oneself to the building of a collection, in any field we enter, is complex, something we only become fully conscious of after the ties become so steadfast that we find ourselves at a point of no return.

Especially when focus is concentrated in the terrain of sacred art, the magic of this universe – responsible for almost the whole monopoly of the Brazilian artistic movement during the first years of its colonization – is an invigorating factor, one that confirms the path to be followed, whose course is filled with acridity and challenges that will most surely be rewarded.

Of course, as the collection takes on a more expressive body, there arises the parallel need to share these works with a more ample public. In this context the idea of an exhibit of private collections seems to me to be the most adequate instrument. We cannot forget that the public has always been, and always will be, the final destiny of any artistic production.

I believe all collectors should follow this path, for they in fact carry out an important role in the preservation of the religious artistic heritage, as well as, through their intimate contact with the works, make systematic contributions to its widespreading and understanding relevant.

Another point to consider refers to the choice of the pieces that will be exhibited. In complete accordance and in full sync with curator Percival Tirapeli, we decided to focus mainly on oratories linked to the Paulista and Mineiro (from Minas Gerais) imaginary of the 17th and 18th centuries, allowing for the adaptation of an historical, evolutionary language of the concepts manipulated.

The different conceptual semantics of these small temples, in their different renditions, are classified as travel oratories, alms boxes, alcove oratories or drawing room oratories, until we reach the height of their representation in the small chapels, taking us back to the devotional domestic cult that went beyond the limits of convent and church frontiers. In a country of unequaled dimensions and never before covered distances, these objects became the accomplices to hope, devotion and the belief of a whole people over hundreds of years.

As to the imaginary, two relevant aspects deserve to be emphasized. The first is in regard to the plasticity imprinted on the pieces by the able saint makers that sculpted the works. But this is not all. In perfect symbiosis, the second aspect results in the observation that these same pieces would become an instrument of veneration for the faithful searching for comfort and an answer to their afflictions.

The sharing of these works’ unique beauty with the public is therefore a way to transcend the whole historical, artistic, religious and devotional significance that each piece brings in its genesis.

Finally, I thank all those who in some manner contribute to the preservation, study and valuation of Brazilian art, and am convinced that by doing this the dignity and respect for our history is being recovered.

Ary Casagrande Filho

The rectilinear external outline of this oratory, with flat door panels fastened with bolts, contrasts to the sinuous lines of its interior. The division of the doors in three segments is conservative on both sides. Inside they frame blue, mono-chromatic paintings symbolizing the Passion, trimmed in rococo. To the right, the stairs, column and dados; to the left the nails, lances, and Mount Calvary.

The oratory is amazing. Beginning at the base, it reproduces the upper part of a retable, with a mock tabernacle, two niches in the body, camera and entablature decorated with urns. The coping is a complete arch with a fully decorated border on the upper part. The retable´s miniature floor plan is concave and the mock tabernacle is convex. The ornamental trimming around the blue, mono-chromatic painting is crowned by an angel head with a shell and roses and a coat of arms of the Sacred Heart, all in golden and red shades.

The painting in the camera (of a popular character), with Christ on the Cross, is a wreath of angel heads in the clouds. It is framed by a bracket crowned by a composite capital. The two figures of Mary and John the Evangelist are disposed on polychrome, concave boards with paintings imitating a niche, with scrolls and lambrequins. The gilding is delicate, with perforations on the gilded doors.

“At nightfall the whole dinner party will gather to intone the litanies, as is the custom of the land, and in these solitary dwellings, or “farms”, there is usually a room with a big box, or cabinet containing some images of saints; the dwellers kneel before these images to pray” (Tamboril, BA, 1817 Prince Maximiliano de WiedNeuwied, Voyage to Brazil, p. 385).

Baroque Oratories Art and devotion in the Casagrande Collection Oratory – From the Word (Orar) to the Devotional Act The word oratory has various meanings. They are ample meanings, such as the domestic devotional, evocative of prayer, or a musical genus, and even an architectural style that designates a place of reclusion. The Latin verb to pray (orar), gives origin to oratory, which means “to speak, to say, to pronounce a ritual formula, a prayer, a speech” and includes terms such as prayer and oracle. All interlink in the act of the search for inner truth. To pray means to humbly and insistently implore in a special and devout manner. It can also be formal speech that, when pronounced publicly, seeks to persuade.

The concept of prayer is impregnated in our daily lives, including the verbal communication by which we have presented ourselves to the world ever since the beginning. Communication between men may be eloquent and solemn by means of the rules of oratory. Used by the clergy, oratory reaches the elevated level of rhetoric in sermons by Father Antonio Vieira. Oratories are also considered literary art, such as the masterpiece by Celicia Meireles, the Oratório de Santa Maria Madalena Egipcíaca (the Oratory of Saint Mary Magdalene Egipcíaca). Musically, the genus was created by Saint Philip Neri and spread by German composer George Frideric Handel, with Oratorio Messiah, in the baroque style, the most well-known part of which is Alleluia.

Oratories as architectural elements – lay and religious – are fixed or movable devotional spaces, as much in the home as in convents. Legally they are cubicles where convicts are confined to pray before their execution. Almost all religions determine a space in homes for the faithful to venerate divinities or ancestors. Food, flowers and incense are offered to them, and objects that go back to the ancestral ritual of burning offerings. The oratory is fixed in the home, but can be transported to other places, for it is inseparable from the protection it confers. Spiritual protection for old Roman homes, and for cities, houses and streets. Oratories also invoke the domo, the dwelling of the gods. The devotional sense indicates the pious, regular and private practice.

A Brief History of the Oratory

Each religion has its own history for oratories. Paleo-Christian art developed in the Roman catacombs, on top of tombs where the mortal remains of the first martyrs rested and where an oil lamp was placed and marked with a painted Christian symbol. In the Byzantine era (5th to 15th centuries) the faithful wore it on their chests for protection. Religious objects were already part of the commerce of small paintings, or portable iconic imitations.

In the Middle Ages, the triptych retables commissioned for the cathedrals had their donators portrayed on the inner part in the kneeling position of those in prayer, alongside the scene in the central part. If closed, grayish, mono-chromatic paintings invoked angles guarding the doors which, when opened, revealed the vision invoked. The upper parts of the triptychs were richly decorated with small sculptures interlaced in the entangled, gilded ogive arches. Portable devotional objects were carried by the Crusaders to Jerusalem to deliver them from death.

During the Renaissance, and especially in northern Europe, triptychs that were merely painted gained notoriety with Peter Paul Rubens and Rembrandt Harmensz van Rijn. After the Counsel of Trent (1563), with the Counter Reformation, altars made of gilded wood with columns and images on the throne and side niches substituted those in which the paintings had predominated. This type of retable, which reminds us of the triumphal arch from which it originates, spread through the Iberian Peninsula and its colonies.

Gestures and Images: Forms of Communication Communication among divinities in ancestral times took place by means of gestures and speech, expressed in art works from all the peoples. Hieroglyphs in Egypt written on papyrus allowed for a new coded language that, evolved by the Middle Eastern peoples, later allowed for the Hebrew’s sacred writings on parchment. The Greek sculptures of the kourai, young supplicants with arms outstretched in prayer or in gratitude to the gods persisted for centuries. The Romans worshiped their ancestors at small altars in the intimacy of their homes. In secrecy, the first Christians marked their meeting places with symbols like the fish; they later adapted pagan figures to Christian imagery, such as the sheppard. Christian images were made official for worship during the Byzantine Empire and the first councils.

The Middle Ages adopted the figures´ symbolic size and space in gilded backgrounds. The optical perspective that condensed the real space was re-established by Giotto, bringing the saintly figures to the earthly terrain. The predominance of the image was confirmed by the Church throughout the Renaissance when it was weakened by the translation of the Bible by German Martin Luther in 1523. While the biblical word was discussed among the Anglo-Saxons, in the catholic world it was explained in the homilies, the explanation of the Bible during mass. With the invention of the printing press, the printed Bible was spread in the vernacular language by the Protestant reformers, who sold it from door to door. The counter-reformers, on their side, intensified the use of printed and multiplied images that soon took over the recently discovered America.

The Scriptures and Sacred Images The material need for spiritual contact came about differently in the Anglo-Saxon world with the translation of the Bible, as did the need for images, relics of the martyrs for the Roman Catholics. The need to communicate with the sacred, be it through gestures or symbols – an ancestral form – brought with it the devotional saints, interpreters between the anguishes of the world and the search for eternal life. The painted scenes of the lives of the saints were understood only in a visual sense and were educational in the search for spirituality. And so in the home, sculpture, as much as painting (the visual sense), substituted the lack of those able to read to them (the sacred literature in Latin), reserved to the few scholars - especially in the Portuguese colony. The images were used to neutralize reformist ideas set forth by Lutherans and Anglicans, more engaged in the biblical word and translated into various vernacular languages. Iberian art embraced the baroque forms in the 17th century and the artisans soon made use of the language of the Catholic sacred art for the making of their oratories, supplying the domestic devotional practice. Oratories took on the shape of small baroque altars, also invoking the mediaeval triptychs with paintings, but elevated to the status of intermediary objects in the communication with the Divine – just like the biblical word.

Here the attribution to Portuguese woodcarver Francisco Vieira Servas is founded primarily in the exact dimension observed in all parts of the piece, which is in perfect balance all the way from its folded and worn out feet to the double curve’s interlaced, rocaille finial, in constant movement up to the flower that rises, opening in space. A characteristic of Servas´ work is present in this flower, or plant-shaped decoration, in the use of curves and contra curves that upon coming together create new, small undulations. In this case, petals bloom protecting the peristyle of a flower (Ramos, 2002, p.138) in the coping of the side retable in the Church of Carmo de Sabará. Due to the size of the piece a crossbow, a complex, curved element on the coping that appears in the big retables, would not fit. The complexity is in the external and internal decorative elements, such as the trilobate arch with a floral intrados, harmonizing with the external curves.

The Portuguese Brazilian Practice D.João III of Portugal had delegated the Jesuits – members of the Society of Jesus, created in 1540 to combat the Lutheran reformists – with the catechizing of the indigenous peoples and the ministering of the religious practice among the colonizers ever since the foundation of the colonial capital, Salvador, in 1549. Benedictines, Franciscans and Carmelites were allowed to settle here during the period the Spanish and Portuguese crowns were united (1580 - 1640). Villages were founded on the coast, beginning with São Vicente (1532) and the monks soon founded São Paulo (1554), the first village in the wilderness. The wilderness was practically everything that wasn’t the coast; it was practically ignored by the monks and remained so until the discovery of gold mines in the immense Paulista territory that bordered Minas Gerais, Goiás, Mato Grosso and part of the country’s southern region.

The practice of carrying images in oratories was spread by the Paulista Bandeirantes (members of the expeditions into the wilderness), by the Baianos (from Bahia) and by the few monks that sometimes went with them on their expeditions to tend to their spiritual needs. The images transported in the oratories stayed in the villages founded along the way and were sometimes even used to celebrate religious worship. Once the farms were established they were quickly incorporated into the architecture, in the wide, wattle and daub walls. In lands where gold and precious stones flourished, the use of the domestic oratory intensified. The monks of the First Order, who lived in the convents, were forbidden to settle in the mines and the religious practice fell partly into the hands of the laymen of the Third Orders, who

would hire the secular clergy for worship. The nuns, on the other hand, created convent oratories in their cloisters, almost always made in small boxes decorated with impressions of the saints. The secularization of religious practices, far away from the rigor of the teaching houses – the main convents in Portugal – was encouraged by the demands of the thriving faithful, avid for the materialization of their spiritualities. São Paulo, Minas Gerais, Mato Grosso and Goiás benefited from this gap in the strict ministering of the religious rites and domestic oratories therefore went on to fill in the void left in the souls of those geographically isolated. Pernambuco, Bahia and the whole northeast took this practice to the plantation houses, while Salvador and Rio de Janeiro looked after an urban clientele and the coffee barons dominated the Paraíba Valley.

From Functionless to Esthetics The placement of an oratory in a house determines as much its shape, which reminds us of a cabinet, decorated or plain, as its function, whether it will be used as an altar or only for prayers. In both cases, the concept of being closed by doors is the most common, no matter the size and where it is placed. Privacy, as much the saints´ as the supplicant’s, is guaranteed. Placement, plus the addition of images in the oratories, highlighted piety with the purpose of substituting the public sacred place for the privacy of the home, due to the impossibility of the social religious practice. There were other obstacles, such as the distances from the farms to the cities, the non-existence of churches, illness issues and social conditions.

The privatization of a religious concept leads to the unfolding of other functions, such as the substitution of the clergy figure for a common man, who becomes the oratory’s owner and, therefore, the person to tell one’s beads and give the blessing. In these cases the oratory’s status and that of its protector extends to other functions, such as begging for the means to build a chapel, as occurred with the image of Our Lady of Aparecida –which went from oratory to chapel, and then on to national basilica.

The esthetic shapes of the oratories are determined by their functions, and it is the artistic period that determines an artist or artisan’s style. This is true as much for the cabinetmakers as for the painters, as well as for the saint sculptors. The wealth of the Maecenas, or that of who commissioned the work, contributes to the material used and to the contract with the artist, who will determine the plasticity. The priors of these Third Orders were responsible for hiring the master-builders and architects for their churches and for contracting artisans for the sculptures and altars. These professional cabinetmakers, sculptors, saint makers and painters imagined and realized the oratories in accordance to church altar styles.

The recovery of work contracts today lead to the discovery of the authors of some oratories, and the comparison between styles, composition and pictorial characteristics of these craftsmen makes up a short list of possibilities as to who made them. Materials, such as types of wood used and polychrome pigments, aid in the difficult task of identifying the authors of the oratories and saints, for, as was the custom at the time, they were never signed. Which saints were in each oratory may be revealed by the paintings, hinting at scenes, by the floral decoration, or by the placement of small pedestals, and even by the passage of time on the paintings.

“I asked the woman at my hostelry if it did not bother her to live in such profound solitude. ´Do I not have´, she answered me, `my family, the care of my work and this company?´ , she added, showing me a small oratory holding an image of the Virgin.. (Arredores de Goiás, GO, 1818 Auguste de Saint-Hilaire, Voyage to Espírito Santo and Rio Doce, p. 88)

Oratory Typology Denominations The intimate devotional act conquered artistic prerogatives of the official forms of faith with the oratory. The shining baroque retables in churches merged into many different forms, adapted to residences. The largest, such as the small church oratories, comparable to small chapels, were incrusted in the wide walls in the farm houses or placed on top of heavy furniture. Their collective celebration functions were similar to those in a chapel. Esthetically, they rivaled the church altars. If smaller, they are called drawing room oratories and placed in the social part of the house, or in an intermediary hall leading to the intimate part of the house – and, if placed here, are called alcove oratories. The ones that can be transported are travel oratories and the smaller, pocket ones, pouch oratories.

Esthetically they may present religious forms, following the stylistic direction of the schools of the time. In Brazil, the baroque lines follow the norms of the retable in regard to the internal columns, imitating altars. The national Portuguese baroque styles, the Joanino (of D. João V of Portugal) and the gentle rococo lines were used for over two hundred years. Baroque’s darker colors paled with the coming of rococo. Saints, angels and flowers complete the symbolism linked to the images displayed in the niches.

Those of a more popular character follow the same esthetic tendencies, although more far removed. The cabinet that holds the saints may have unusual solutions due to the difficulties encountered by the artisan. Modular doors, drawers for alms and

fanciful finial’s are part of the same religious forms, indicating similar functions. The delicate paintings, flowers as much as figures, guarantee a sui generis spatiality, confirmed by the search of perspective and symbolic sizes. These elements are joined with those of various African ethnic groups accustomed to syncretism’s, to the use of ancestral symbols of their religions and objects of their religions of origin.

Configurations The exterior configuration of an oratory is that of a cabinet, a reminder of a sacred place, the church, containing an altar inside. The most delicate shapes also remind us of towers with a Cross on top. Flat door panels with lozenges and rectangles aid in the regional identification. Feet in the shape of small pedestals make them lighter and more elegant on top of the commodes. The finial, which would correspond to the coping on the retable, indicates the stylistic period and even the author. Articulated doors remind us of the mediaeval triptychs or polyptychs. The larger oratories follow the retable expression, with an altar base and a mock tabernacle as a foundation. The altar is used as a sacristy to keep liturgical garments, which can also be put away in lateral spaces, substituting the great chest; the mock tabernacle is only esthetic, for consecrated Eucharist bread can be kept nowhere except in churches.

The body of the small church oratory generally opens in a great tribune and, if the height permits, there is a throne or small pedestals to display sculptures. Columns generally side the limits of the wooden coffer, or sometimes only lacework engravings delimit the entrance to the camera. The coping and columns define the typology, the most frequent for the oldest ones being in the national Portuguese style. For those from the first half of the 18th century the most commonly seen is the Joanino style, and after that, the rococo, which went into the 19th century – when it was substituted by the neoclassic. Paintings and wall sconces with flowers complete the decoration. The chest oratory is used for the celebration of mass. There are painted scenes on the doors´ internal panels, circled by borders formed by the setting of the wood. The wood indicates the region; when in jacaranda it is usually from the northeast ; in cedar, from Minas Gerais or other regions in the southeast, such as Rio de Janeiro.

The drawing room oratories are notable for a more elaborate configuration. Seen also in profile, they gain new forms with articulated doors that open like pages of the sacred scriptures, revealing their iconographic treasures. The finials may be heavy, such as windows or doors with curved lintels when they go back to the architectural forms of churches. If the referential is an altar they are more unconstrained and fanciful, as allowed by the retable copings and feet that look a little like elaborate pedestals. They gain spatial growth on the sides, as well as opening arches. If glassed-in, they remind us of the altars reserved for relics, a practice spread especially by the Jesuits.

The alcove oratories are smaller and, placed on top of commodes gain a variety of forms that remind us of the drawing room oratories. They usually have small doors with paintings on the inside and the distribution of the images makes it possible for saints to be added. If small, the sculptures are small, like the tiny paulistinha saints, made in clay on a hollow, conical base, rivaling a piece of heaven in the intimacy of the home.

The nativity oratories can hold a larger number of small figures . The iconography of biblical passages, such as the birth and Passion of Christ, demand a great number of figures for this kind of oratory. The chronological sequence of facts unfolds stories developed in vertical levels or spaces, such as the nativity scene and the Calvary. If they belong to the hagiological, the miracles are portrayed according to their importance, such as the Franciscan or Carmelite passages. The saints, protected here by glass, are easily identified as coming from Minas Gerais due to the use of the Piranga River region’s and ferriferous quadrilateral’s French chalk or limestone.

The convent oratories have the shape of small boxes. They are generally glassed-in and richly decorated assemblagens, and their materials are usually determined by who made them or who commissioned them. Reproductions of saints or small images are used, with laminated, golden and perforated papers, making up the ornamental architecture that substitutes the wood and gold. The visual aspect gathered together in these oratories shows the devotional vanity lost in preciosities and simplicity. Instruments to make flowers, beaded strings and embroideries may seen even today in the cultural venues many convents in Iberian lands were transformed into.

The shell oratories are a treasure in themselves, in which the Child Jesus reigns, richly clothed in vestments and seamless tunics generated by the labor of the artisan’s minute details and patience. In colonial Rio de Janeiro, Francisco Xavier dos Santos, later nicknamed das Conchas (of the shells), created oratories with shells that spread throughout Santa Catarina. There is a precious collection in the Convent of Santo Amaro da Purificação, in the Recôncavo Baiano (a region surrounding Salvador, Bahia).

Typology – the Poetry of the Oratory

Without the paternity of the hands that created them and without the retable majesty of churches, the classification for devotional oratories is in a limbo, between the erudite and the popular.

Of different uses, from being carried in a bullet-shaped pouch, as company and consolation for the sertanejo (man of the wilderness); to the alcove, for the maiden trapped in her hopes of the freedom of marriage; the drawing room, to be seen, and its

gilt polished to impress visitors; the small chapels, a substitute for the temple far away from the manor houses, the coffee barons´ farms; if for travel, on the backs of mules, they open in the darkness of night for sad prayers, rhythmical and hopeful chaplets for the new destination; of Mediaeval tradition, such as alms boxes, worn on the chest of penitents or escravos de ganho (slaves who had learned a trade and went out in the morning to outsource their services. Upon returning in the evening they would give their masters half their pay) to raise money for festivities; if confined to houses, with drawers or false bottoms hiding riches that would be turned into gifts and used towards improvements for churches; in the silence of the virgins, with their cold hands and wax-colored necks, secluded in the convents, the oratories take on cloistered forms. The Children are asphyxiated in vitro, warmed by clothes and fabrics woven by a few praying widows with thin and celestial voices.

The oratory’s shape reveals the devotional intimacy, with little doors that reveal the secrets of the soul. If placed in drawing rooms, they await a visit from far away; if open, they reveal the material wealth accumulated. If in small churches, the oratories are solemn, with the certainty of baptismal ceremonies and ecclesiastical presences. Suns illuminating the farm houses in the distant wilderness, complex and robust, in resemblance to their landowners, the coronéis, and men of the court bearing coats-of-arms.

They rarely fully reveal themselves to the first curious look: they are humble-looking on the outside. Look at the somber oratories from the outside, open them with your heart in prayer and the perfume of wild roses will fill the air with the certainty that the flame will guide the soul. And so, memories of a time lost between images and archetypes of religiousness lead us to commune with our past.

Stylistic changes Oratories are mute, gentle witnesses, transportable over our Brazilian regions throughout all our historical periods. When the Tordesilhas Line (1494) was crowding us against Spanish lands, they were simple and light, the true symbol of spirituality embodied in this small, portable object.

Heavy, as in the baroque lines of Pernambuco, disturbed by the Dutch presence in the plantations and chapels destroyed by the reformers. Sophisticated, with a Joanino sobriety, and accustomed to solemn prayers from the masters of the colonial capital. Enigmatic, when the darkness of night intermixed with the sobs of the slaves, expatriated to the lands of Bahia. Light, covered in gold and resplendence, straight out of the gold mines. Faded, worn out forms, ready to rise to the spiritual plane, artistic eternity materialized in the hands that formerly sifted the wooden bowls, looking for gold.

Elegant and complex like the rituals of the court. Ennobled by formal, esthetic codes coming from Rome, Paris and Lisbon, the oratories from the then imperial capital challenged Freemason rumors and went on to the coffee barons’ farms. In the faraway Anhanguera wilderness they grew accustomed to the fierce destiny of death. In the shape of small coffins, only crosses showed the way to the hope of new lives.

Esthetics The configuration of the drawing room oratory, with a drawer at the base, is solid and traditional. Straight lines and austere, prominent outlines frame the whole form, shaped like a cabinet. The finial is simple, with an almost flat, sculpted flower, and another two that soften the stiff, upper corners. The prominent panels, as much the doors´ as the drawer’s, soften the excessive pediment. The signs of the pegs that support the frames indicate old techniques. Upon opening them, two paintings in the form of curtains create a strange deepness because of the outsized, small niches attached to the doors. Still on the doors leaves. A dressing room curtain opens. A lace-like and continuous trimming on the edge of the flat arch and sides, up to the height of the small doorleaves, allows for a view of the generous form that qualifies the body of a retable. The throne is a three-step pentagon, sided by two scrolls that uphold the marbled torso columns, in shades of Verona’s rosso marble and lapis lazuli. The shades rise in alternative twists, blending with the polychrome flowers in the back of the camera. A strange capital upholds the entablature with small pilasters, crowned with leaves. The canopy, with complete lambrequin and tassels, completes the retable´s decoration. The ceiling imitates the barrel vaults of a main altar.

The Finials Oratory finials immediately make their configuration and planning concept clear, beginning with their cupboard shape, imitating the façade of a church, usually used for the drawing room and small chapel oratories analyzed here. The old Paulista ones from the Mannerism period, from the 17th and 18th centuries, display stiff forms, almost cabinets, with paneled doors that open. The finials are simple, reminding us of the pediments on the Jesuit churches, with triangular, lightly curved gables, with two flat, scroll engravings. The finials are overlaid.

Baroque finials from the late 17th and early 18th centuries, in the national Portuguese style, are independent from the structure and are curved and symmetric, with two scrolls, and the triangle in curves and contra curves. An example is the small church oratory from Pernambuco, in jacaranda.

Those from the mid 18th century bring the finials incorporated to the structures, reminding us of doors or windows with curved lintels, which in oratories acquire more friezes than

in architecture. Others suggest portals with sculptured finials coming from the structures that support the door panels, and yet others are glass. Symmetric, and still presenting airs of strict religiousness, they appear with no polychrome, emphasizing the decorations and material used in the making the piece, especially in the sculptured relief work. Those in perspective, or even the polygonal ones, present curved finials that follow the sides. When open, the doors´ curved arches are multiplied, making them more graceful.

Oratories in the rococo style, such as the ones seen here from Rio de Janeiro, have finials in curves and contra curves deriving from the furniture’s structure. The decorative asymmetry may begin at the base, passing by the structures that delimit the opening arches and widen into the most delicate finial. The glass doors aid in the concept of a window piece, free from the concept of a cabinet imitating the facade of a church or a window and turning into an object to be appreciated as a work of art. The finials are fanciful, with carefully engraved lacework in hardwood.

The nativity oratories, however, follow another structure. They are smaller, usually made from a sole piece of wood from which appear the feet, and the same curved lines follow the stylistic parameters, as much for the opening of the camera as for the fanciful finial at the coping. A sequence of curves form arches, generally three-lobed at the opening of the camera and at the base, where a small pedestal is placed. The partition here is straighter and decorated with curves that blend more with the adjacent feet.

Interiors Depending on the typology – whether small church or drawing room – they are deeper or shallower. The small chapel oratory is in fact a real altar, with the table built-in or not into the cabinet. Inside it imitates a retable, with a triumphal arch, as if to separate the nave from the main altar – and for domestic use may separate the room or hall from the devotional part of the house. If smaller, it imitates an altar all over, with a tabernacle, columns and camera with niches and small pedestals, even on the doors.

Drawing room oratories are not as deep and, depending on the devotional objects, have only a base for the crucifix and small pedestals for the figures that make up the scene of the Passion. There are figures on the doors, as well as in the back, increasing the depth with scenes of Jerusalem. Painted curtains aid this intention and flowers complete the iconography, usually roses for the saints or the Virgin Mary.

Nativity oratories have different levels that follow the chronology of the scenes, such as the nativity scene in the lower part and other scenes, usually of the Passion, on the upper level. The convent oratories imitate altars, it would be better to view them as boxes in which there are a succession of levels, with the repeated woodcarvings forming the altars. The shell oratories are to be viewed from the front like all the others, however their placement on top of furniture sometimes allows them to be admired laterally. Their glass domes, which are similar to bulletshaped oratories, make them easily viewed from all sides.

Paintings The pictorial decoration may be figurative or floral, or merely present the polychrome resulting from the various combinations, such as marbled. Pieces blessed with the patina of time, the marks of wear and tear, present a taste of antiquity expected from works that have not been restored. Bright colors, such as reds and blues, fade, as is the case with the Paulista oratories of the 17th century.

The polychrome resulting from the application on backgrounds is characteristic of the pieces in this collection, such as marbled and trompe l´oil effects on borders and vases, and flowers with shadows. The figures of the saints, apostles and the Virgin, with or without the little angel-head wreaths, are surprising for their quality, which goes from the erudite to the popular taste. The high quality of the painting on top of the woodcarving, or even the construction of the oratory, reveals the sophistication in the choice of the pieces and in the quest for the collection’s excellence. The oratory with the two enlarged figures of Mary and St. John the Evangelist, plus the painting of Jerusalem at the time of Christ’s death, is a highlight of the pieces exhibited. The little angels look like bouquets, more to the popular taste, and sometimes present a rather dark complexion.

The symbolism of flowers is present in most of the decorated backgrounds that make up the iconography of the saints presented in the scenes. One cannot always tell who these saints may be, however roses indicate the presence of Mary; nails, the suffering of Christ; poppies, the dormancy of death; lilies, the symbolism of purity; and sunflowers, the devotional attitude. Flowers are presented lightly throughout the spaces, in wreaths or in baroque-shaped vases, twisted or frayed in the rococo manner.

Saints Due to their being domestic oratories, for private devotion, saints chosen to be sheltered here merely follow the wish of the devotee. Traces that saints were housed here are clearer when the subject regards scenes from the Passion of Christ, with marks of the crucifix born with the passage of time. The two little side pedestals indicate the presence of Mary and John the Evangelist. The same occurs with the paintings that bring the same scene, with paintings of Jerusalem for the nativity scene, with starry skies and the Eastern Star. The symbols of the Passion of Christ – lash, nails and ladder – also clearly show the presence of Christ

or Our Lady of Sorrows. Passion fruit flowers symbolize the Passion of Christ, and the roses, Mary and the other saints. Therefore the vestiges, the stains on the old paintings, are the paths to follow on this trail, where the devotee’s wish does not always follow rational religious iconography. Closed oratories are safer for preserving original images, but it is more difficult to know who the saints were in the travel oratories, unless they hold the name of the devotee and its patron. Collectors generally adapt saints from the same period in the oratories they acquire, be it for size or from mere intuition. They are the new admirers, following the example of so many devotees who placed their saints here.

The oratory is delightful for its polychrome, which slowly reveals the complete forms of a retable, plastically determined in a popular manner. On the outside its highlight is the curvilinear coping, accentuated by its reddish color. Inside, the two leaves on the little doors present two big vases with flowers, symbolically of the Marian Congregations, which spread between the columns and background of the camera. The imitation retable, beginning at the base with a mock tabernacle, upright columns, with paintings of twisted columns, flat woodcarvings and curved canopy at the coping shows the artisan’s effort to create a piece for worship. This feeling is explained by the blueprint that oscillates between the straightness of the socles on the columns and the convexity of the mock tabernacle’s shape, made into a niche.

From the Domestic Devotional Object to the Collector’s Object of Art Destined to all destinies, accustomed to all anguishes, oratories dispense authorship. Who says the hands that inlay the wood cannot gild? Who can prove they can’t touch smooth surfaces with paintbrushes? At least the little roses. If the rules of the brotherhood were followed, the work is collective. Cabinetmaking, gilding, painting, aside from the imaginary. When finished, its destiny is certain and soon uncertain. It moves, its saints go out of fashion when they don’t listen to the supplicant’s requests. They get lost in the genealogy.

They await a new believer. They are carried like merchandise. Sold. Full of supplications, they are unmoved when faced with new esthetic norms. The image’s parched, darkened and rotten wood indicates the patina of time. When looked at they seem withdrawn, placed on top of tables and altar fragments. They rival importance with paintings and tapestries on the walls. The oratories, in the eyes of art specialists, decorators and collectors, were seen as objects of desire of a time of lost mysteries, when religion governed society and private life originated in Portuguese religiousness. As to origin, if it be an Indo-Portuguese oratory decorated with inlaid ivories and mother-of-pearls, it was worth more because of the risks in its travels in the abysm of the emptiness between the Indian and Atlantic oceans, over routes never before navigated. European wood guarantees an aristocratic luster expressed in the woodcarvings, in the puncture marks that border peonies, cloves and poppies, symbols used in those times, so different from our pineapples, passion fruits and wild daisies. Beveled glass and crystal guarantee the impenetrability of simple prayers in hopes of their being granted, in French suitable to the lettered matrons. The guarantee of having witnessed prayers from baronesses and emperor’s lovers increases its pecuniary value, and its rarity is proclaimed.

Antiquity guarantees admiration. The lightly brutalized forms take them to obscure regions; their survival in the jungles, fires and fights between masters, slaves and indigenous peoples dignified their history and their reappearance in civilization. The marks of misadventures are glorified when they are exchanged. The paintings, singed by the flames of devotional candles, are a background to the wrinkled cracks on the faces of the saints that metamorphose into punishments for lost souls and convictions for avaricious former owners.

The sophistication of esthetic forms must be always reviewed by the collector, in this manner widening the qualities that may raise the work to the level of exclusivity, a unique object, far removed from the popular workshops. Formal rareness acquires value with the introduction of an eventual authorship. If the formal, stylistic characteristics of each author are confirmed, comparisons begin. Each form must then be compared to more important works, recognized altars, the best burnished gilding, the most precise shadings in vestments and the most sophisticated forms affected by the baroque or rococo styles.

The popular oratory, on the other hand, acquires esthetical/ cultural value for its origin, in the development of religious art up to its appropriation by the popular tiers. This distancing from European paradigms creates echoes in the search for Brazilianism. Straighter shapes, earth colors, images made of clay characterize a favorable scene for the rusticity necessary for popular art. The artisan is the focus of study for few scholars, soon proclaimed for having filled an expressive need in time and space, the birth of a regionalism.

Today, shifted from the penumbra environments, lost in the elongated and drifting shadows of the whitewashed walls’ gray and white solitudes, oratories display themselves under an artistic aura. Made from hard woods, crafted by able hands of the brotherhood of the cabinetmakers, a procession of Josephs sent the oratories from their colonial workshops to the houses in the mews, mansions in the cities and manors on the farms. With a change in address, the oratories left the houses in the wilderness for the sophisticated urban salons, in close relationship with the modern

feeling of the figurative paintings echoing baroque, or with those abstract and concrete.

This increase in value of the baroque devotional originates in the Modernist Movement, upon the journey made by Mário de Andrade, Oswald de Andrade and Tarsila do Amaral in 1924 through Minas Gerais – which led the artist to declare herself in love with the caipira (country people) paintings which she had formerly been forbidden to use in her work. The search for a nationality and for artistic figures that would confirm a Brazilian art led the modernists to consider the baroque art of the colonial period as the genesis of Brazilianism. In the 60’s, with the confirmation of modernity and the threat of international distraction, baroque objects entered into the decor, mixing the modern/old during the development period of the Juscelino Kubistchek, a former president of Brazil, constructor of Brasilia, 1961) years. The collecting of sacred objects gained momentum with the destruction of church ornamental elements that, years later, became modern for a second time, following the norms of the Second Vatican Council. Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo were the main receptors of these private pieces, dislocated from the northeast to the southeast, thus guaranteeing their survival in this intense movement of baroque devotional objects.

Oratories – 17th century – from the Manor Houses to those of the Bandeirantes

“There is also an oratory reserved for domestic prayer, usually placed on the porch, on the other side of the house” (João Maurício Rugendas, 1825/30, Picturesque Journey through Brazil, p. 113)

The 17th century oratories from Pernambuco and São Paulo in this collection are austere in their external configuration, with finials imitating church pediments. The full arch is the most visible on the inside, following norms of the national Portuguese baroque style. The example from Pernambuco is of elegant woodcarving, with excellent paintings. The ones from São Paulo follow an Hispanic tradition of flat woodcarving, with delicate roses and with the polychrome more accentuated in the reds. The painting is of a more popular taste, with the freshness of rustic strokes for flowers and votive motifs, and the polychrome, when present, is faded, attesting to the antiquity of the pieces. In three of them there are small banisters imitating the delimited parts in churches, and a communion table. The oratory with an alms box is notable for the sophistication of the woodcarving work.

Most notable in the Casagrande Collection is the majestic, small church oratory from Pernambuco, made in jacaranda. On the outside it presents the stiff form of a cabinet, with heavy feet softened by friezes on the door-sill, and on top, a coping with two austere scrolls and a triangular pediment with gentle curves and contra curves. The interior is amazing: a real retable opens up with a triumphal arch, with twisted columns, a double entablature and the coping with a flat arch and intrados and acanthus leave reliefs. The sophistication in the wooden sculpture shows the elegant work of the masters from the northeast.

The impeccable piece is completed with important paintings. Scrolls framing egg-shaped medallions with the sun and moon are present on the door panels. Inside the camera there is a halo, surrounded by a starry sky. Below, one of the most amazing and well-preserved oratory paintings: celestial Jerusalem, garrisoned by big walls, full of towers and sparkling palaces, protected by a bluish vault and shimmering stars.

The austere drawing room oratory in the rigid form of a cabinet, made of dark, ornately carved wood goes back to austere conditions in material life, geographic isolation and the need to adapt to the inhospitable environment faced by the Bandeirantes, who lacked spiritual protection in the wilderness. On the open doors of the shallow oratory, a quiet decoration appears on the twisted columns at the height of the tiny capital and looses itself in the flat arch with an almost flat, twisted frieze. A banister delimits the sacred places, where the saints of the world inhabit the sufferings of the devout.

The finial imprints a bit of lightness to the austerity of the piece. The curves and contra curves, although appearing in flat woodcarving, make the work pleasing to the eye and the careful cutting of the spires alleviates the flat parts that dominate the whole oratory.

The drawing room oratory from São Paulo, opening into a big arch, is straightforward and simple in its two parts. The stiffness of the frontal rectangular shape is softened not only by the flat arch, but also by the detailed, floral polychrome decoration of the whole trimming – from the flat columns to the arch, aside from the bigger roses on the upper angles.

These roses are repeated on the delicate finial, almost innocent, attempting imitations of scrolls on top of the cross on a globe. The collector’s feeling for electing the Christ of Ecce Homo with tied hands reflects a fortunate encounter between the oratory’s simplicity, from Iguape, on the Paulista coast, with the image made of baked clay from Santana de Parnaíba. The niche has a parapet to unite the scene, in which Christ is presented in the mantle, however, already convicted. The use of the reddish color remits to the proximity of the Paulista lands with those of the kingdom of Spain.

The delicacy of the oratory from São Paulo is evident on the outside for its popular forms, which make an effort to imitate

the more sophisticated ones, especially in the framings presented throughout the whole structure. The finial, which may be of a later date, confirms the artisan’s difficulty in expressing serrulate sculptured forms.

Upon opening the little doors, a breath of faith is felt coming from the flames of outsized candles and candelabra. The lines, imitating lacework frames in the Hispanic taste of the missionary lands bordering São Paulo, take on a bigger body, enlarging the ornamental, pictorial theme in the boards in the back. These strong lines imprison symbolic forms with a Greek cross because of the oratory’s square shape. Golden sparks come out of small lozenges and squares with superposed golden leaves.

Oratories in the Colonial Capitals – 18th Century

“....we should have a pretty, high oratory, in jacaranda, with an image of Our Lady of Conception”. (Machado de Assis, Dom Casmurro, p. 69)

Oratories in the coastal cities, especially Salvador and Rio de Janeiro, capitals of the Colony and Empire, present sophistications and solutions due to their constant contact with the metropolis. The two from Bahia are in jacaranda and the travel one presents work in marqueterie. The paintings have an impacting presence, especially those of Our Lady of Sorrows and Saint John the Evangelist in the oratory with the painting of Jerusalem. The oratories from Rio de Janeiro in the Casagrande Collection are made of jacaranda and offer fanciful cuttings in the finials, which distinguish them from those from Minas Gerais. The D. José I of Portugal rococo style is repeated, with soft lines and precious engravings, with no polychrome. Three of them have three doors, making it possible to make various visits, seeking distinction and the status of being special pieces.

The paintings stand out in the decoration of this oratory of sophisticated, curved forms, expressed in the three-lobed arch with a lacework frame sheltering the scene of the Crucifixion. The representation, of a symbolic size, shows the sufferings of Mary and the beloved disciple, who in an obvious distortion antecede the painting of the city and the Crucifix. The artist follows the exact iconography of placing the Lady of Sorrows on the left side, John the Evangelist on the right and in the background the Jerusalem of the moment of the storm when Christ exclaims Eli! Eli! lama sabctani? (My God! My God! Why hast though forsaken me?). The city appears diffuse among clouds, and lightening strikes the temple’s veil. Dark-faced angels with full lips are perplexed witnesses at the moment of salvation.

The artist’s enthusiasm on painting the two figures on the doors puts them at a disproportion as much in regards to the Crucified as to the painting of Jerusalem. Although the lines are baroque, they go back to the mediaeval symbolic perspective, the suffering of mortals amplified here with the divine sacrifice. The richness of the crucifix, with silver resplendency, reappears within the rolling clouds. The distance between the two pictorial side figures and the scene in the background may justify the smaller size of the Christ.

The marqueterie work on the small doors, with symbols of the Passion of Christ, distinguishes this piece from other pictorial motifs in the collection. The composition of the lances and the ladder –bigger and more central – solves the smaller objects from the torment: three nails, a hammer and pincers. In the background, the cross and the shroud confirm the presence of the Crucified. Viewed from behind, the small piece is surprising for the almost secret opening, and the scene is viewed inversely, with the cross and the shroud on the first plane, while the other symbols of the Passion may be seen through the border.

The wooden piece confirms the artisan’s ability, expressed in the straight and curved friezes and in the encasements, giving the oratory a robust and solid look, consonant with the iconography. The care taken in its making continues in the pen-shaped hinges and key and hooks to hitch chains to for transportation, all made of silver.

This piece is divided in two distinct parts: the glassed-in body and the richly decorated coping. It opens in perspective, showing the opening arches on the side, the central one being distinguished among smooth frames. Upon approaching, the devotee notices little flowers issuing forth from the artisan’s carefully handled gouge that slowly stretch up the frame, and in a prominent crescendo above, prepare a visual surprise. The coping looks like a flame that grows in blazing forms. It slowly reveals itself: the sinuosity of the central piece, crackled in curves and contra curves, is enlarged under the echo of the undulant friezes. The side finials confirm the fanciful configuration on taking over the whole top part of the piece. There are intervals and hollow spaces to harbor the sighs of admiration.

Seen at a glance it has an oriental air, as much in the configuration of a shadow play, in the Chinese style, as in the shininess and coloration of the flowers that remind us of things Chinese. In the penumbra, the dark wood’s material makes the piece shiver in unison, from the feet that elevate it and rosy coloring, highlighted by golden lines marked with perforations, up to the last curve, seeking more space in the heavens.

The sobriety of the oratory in dark wood and straight lines has two visual compensations that lend it lightness. The first is at the base, in lines that open allowing for a view of the opening arches

on the side. The second is in the big arch in complex curves and contra curves, toped by forms that throb between the enlargement and retraction of the piece’s verticalness. The oratory is encased in glass on tree sides, the one in front being toped by a big curve issuing curved friezes, echoed throughout the finial. Sophisticated woodcarving rises from the base through the structures that support the upper part, where they end in the shape of four scrolls. On top of the prominent entablature, four flaming spires make the piece appear higher. From the undulant curves of the door jam, and echoing the door’s curvilinear structure, sprout fanciful, rocaille (stone) decorations. The pictorial rocaille blends with the worn-out forms of the finial and the flowers open in fresh, pinkish shades, at the height of their lushness.

Golden Devotion – Private Baroque Objects

“Back from a short outing (…) I found the whole family praying (…) the doors to the oratory were opened in pairs and the Crucifix exposed just up to the moment dinner was served in the same room: the owner of the house, with great seriousness, then approached, and after deeply reverencing the image, closed the doors.” (Surroundings of São João del Rei, MG. John Luccock, Notes on Rio de Janeiro and southern parts of Brazil, p. 295)

A series of factors incremented the intense production in the lands of Minas Gerais: the riches of gold that led a group of artists to the cities, artists who produced the most expressive baroque and rococo works throughout the 18th century; the demand for supplying the manors on farms far away from urban centers; the oratory trend in the mansions of the wealthy; the lack of priests and the consequent greater freedom of the secular clergy; and finally the encouragement given on part of the third orders for artistic commissions. All this contributed to the development of a school of artisans for the manufacture of small church and drawing room oratories.

This shallow oratory has paintings imitating wood on the two leaves that form the arched door, finished with a prominent, blue polychrome rim with faded flowers. When opened, this bluish, monochromic color gains softness, cut by the griseous shades of the rococo. The lightness obtained in the strokes is the search for spatial adaptation, determined by the door partitions. In pairs, palms and vases imitating rocailles offer a pictorial grace, enhanced by the roses, carnations and bluish bellflowers. The lack of lightness on the outside of the work contrasts with the painting inside, imitating marble-like wood, with a vaulted coping and finial with pawn-shaped spires.

The camera is entered through smooth columns added to the lateral parts supporting the flat arch, with intrados above the entablature, which curtails the hollowed-out trimming. The layout is rectangular and determines the lack of depth in the piece. There are paintings of lozenges on the whole background, veiled by undulant, bluish lines with delicate bunches of flowers where they cross.

This piece is without a doubt the highlight of the collection due to its sophisticated forms and differentiated polychrome in silvergray, which makes it come close to a being a chiseled shrine. The rococo style allowed the three-sided oratory to spread its wings, with work beginning right at the feet which, seen from the side, present the same work as the frontal side, with forms in rocailles and lines marked by curves and protrusions. The lower friezes are prominent and follow the polygonal plan of the piece’s interior. The decorations begin as of the braces that elevate the base, and there is an interlude of smooth forms on the friezes, which gain momentum in the borders circling the opening arches.

The whole piece has an erudite tenor, built to be admired on all three, equally elaborated sides. The polygonal base emphasizes the representation on which it was conceived. The structures for the opening arches are less elaborate, acquiring a decorative momentum over the curves of the finial, with rocailles that prepare the ceiling’s dome. The coping’s solution is unusual, with conjugated forms coupled to the curves in relief from the smooth, upper parts of the finial, divided by friezes in three parts. The polychrome is discreet, exalting the sculptural forms and reaching its peak in the beauty of an image to be venerated.

The cabinetwork of this piece is highlighted by the perspective form beginning at the base, offering a view of both articulated doors, paneled when closed, and the arches, when the doors are open. The finial on the arch is triple, if viewed open, and double if viewed closed. The curvilinear lines soften the weight of the coping, which presents similar plastic aspects on the three sides. The value of the piece lies in its structural planning, for the polychrome and symbolic floral paintings are not up to par with the construction of the oratory. The simplicity in coloring of the bluish, rococo shades emphasizes the heavy baroque lines.

The internal space of this oratory with illusionist paintings is obtained more by the coloration of the polychrome than by a planned cabinetmaking structure. The curved doors, following the friezes on the double finials, have mock panels obtained by the pink, ochre, Naples yellow and blue colorations, cut by the greenish grays and whites of the rococo trimming.

The level placement of the opening arch to the camera, with prominent borders on the straight columns, and simulated on the

flat arch on top of the entablature, creates a zone of light and shadows between the internal and external finial. The contrast of the external finial’s continuous and prominent friezes, creating a real deepness, blends with the virtual deepness of the door panels, portrayed here through the use of illusionist painting.

When closed this slightly shallow oratory looks flat, with a pictorial appeal in the ample, arched door leaves. On top, a small, curved salience acting as a finial presents faded, bluish polychrome with small scrolls and flowers. The door leaves are made of flat, superimposed planks, and mock wood and marblelike paintings imitate panels.

The charm in this oratory is in the painting that involves the whole piece, which is spontaneous and reinforces the piece’s little depth in a polygonal floor plan. The doors look more like simple windows, with three planks nailed on two planks. When open they reveal a simplified camera with a simple frame of curves and contra curves. The greatest beauty is in the paintings of vases in the shape of a chalice, with feet, stalk and cup in twisted shapes. The roses overflow the chalices and two crossed carnations arise, until they are stopped by the beams that secure the planks. Above, in the curved part, painting imitates a sculptured trimming. Flowers of the Passion blend with the carnations, also a symbol of Christ’s suffering. For being of a shallow depth, this oratory indicates the placement of the Crucified.

Nativity Oratories The configuration of this series of nativity oratories is very similar, as much in the opening arches in three-lobed arches as in the plant-shaped, lacelike finials. Said arches become more segmental above the feet, forming a polygonal space that lends lightness to the small pieces. The opening arches above echo in the curves opposite the finial friezes. There is an ornamental, plant-like element in all of them, symmetrical, searching for a greater height.

In the lands of the gold mines nativity oratories encountered the encouragement for using limestone to populate the diverse kinds of oratories with sculptured groups of the nativity scene and the Calvary. Rococo encountered as much the worn out forms, sculpted in bland wood, as cedar, used for the floral arrangements and trompe l’oeil frames, imitating door panels, vases and small pedestals.

This nativity oratory is rare for the coloration of the doors, with paintings of the evangelists. Usually open and glassed-in –to protect the sculptures – they are populated with small sculptures and in Minas Gerais are made from the ferriferous region’s limestone. The configuration of the piece is of great delicacy, with lacework on the coping and on the border of the arch, aside from rococo curves and contra curves coming from the elegant base of the feet up to the shell-like form that appears on the border of the finial.

The divisions inside the niches are also in curvilinear moldings, with the lower niche reserved for the nativity scene and the upper one for the Calvary, aside from niches with additional figures, some at the foot of the Cross. The paintings on the door leaves are of a more popular character than the sculptures, which are technically more sophisticated.

A lacework wreath of roses frames the scene in an attempt to appease the tragic moment of the salvation. Flowers abound, as much in the back of the oratory as on the outside, which is highlighted by sinuous lines that twist into the shell-like form of the finial’s border. The pictorial presence of the four evangelists –Luke, Mathew, John and Mark – enhances the veracity of the sculptured witnesses to the Golgotha.

The rococo piece, chiseled from one sole block of wood, looks like an ornamented border with a graceful frame. Full of curves and contra curves the frame, or trimming, moves as much in the external as internal configurations, with recesses, creating echoes with worn out forms on the salient parts. On the upper part, two lacework aspects direct the eye outside the scene, and grow into other flaming forms that blend with the angel’s wings in the scene of the Annunciation. The saffron flower (crocus), which alludes to the Resurrection, symbolically crowns the rich, symbolic oratory.

In the center, in the opening that allows for a view of the ceiling paintings, the Angel Gabriel and the Virgin, in small polychrome sculptures, lend veracity to the scene described in the four Gospels. The painting of a crimson curtain highlights the symbol of the Holy Ghost, the dove with rays of light, which appears above the small altar. Two vases of flowers on the side walls tie up the scene, being that the one on the Virgin’s side is in the shape of a cross.

Travel and Alcove Oratories Travel oratories transported Mannerist clay saints made in São Paulo; ivory ones, from Goa, making port in Rio de Janeiro; baroques, richly decorated with the gold returning from Lisbon, rococos, idealized by the saint makers, proud of their work; and then those that were more quiet during the whole 19th century, somewhat unhappy by the sieges, betrayals and greed. Those in the shape of a bullet (being similar in form to cartridge-belt bullets), in a pouch, kept close to the bodies of the cattle dealers, as one body and soul, on the backs of the mules, tired of so many baroque and rococo curves. In the Casagrande Collection the monumental, one-of-a-kind oratory from Bahia is noteworthy.

These oratories may even present some neoclassical lines,

far removed from those creative and exuberant paths of the art of the devotional oratories from Minas Gerais, full of saints, gold, flowers and pleas before the alcove oratories.

The Imaginary

“ Slouched deep in the couch, in the shadow projected by a porcelain vase placed in front of a candle to cut the light, she was staring at the image of Our Lady of Sorrows on top of a commode in a jacaranda niche.” (Outskirts of São Paulo, SP, 1846/72 José de Alencar, Til, p. 112)

The Cristiane and Ary Casagrande Collection, aside from its dedication to oratories, also presents a careful selection of 19th century paulistinha saints, images in clay made by Paulistas from the 17th century, wooden images from all over the country, from the Joanino baroque period and precious Portuguese mannerist images. Beginning with the latter, two Virgins with the Child, of a cylindrical shape in which the mannerist planning is revealed, are especially notable. The beauty of the Children and the gracefulness of their gestures points to Italian Renaissance influences – contradicting the French and German masters’ Gothicism, in place at the time.

The clay images from São Paulo are those attributed to Friar Agostinho de Jesus and his school, beginning with their production in Santana de Parnaíba: a fragment of the Rosary, without the characteristic Benedictine base, an image of the Conception and one of the Rosary. There are other images in clay from the same region, similar to the Benedictine school, such as a Child lying down, a Saint Joseph and a Pieta. From the regions of Mogi das Cruzes and the Paraíba Valley there are saints of other invocations and various from Itú, of a popular character. A series of Pietas and figures of the Passion – Christ of the Patience, in polychrome clay, complete this 18th century Paulista series.

Two busts, one of Saint Francis and one of Saint Peter, are of great realism, presenting the generous volumes of religious art in clay. Ivory crucifixions and a precious image of Our Lady of the Immaculate Conception of Goa represent oriental art.

Images from the 18th century are middle to small-sized in oratories from Minas Gerais and are made in wood and limestone. The retable-like image of the Rosary from Pernambuco is elegant, with sweeping lines and reddish polychrome.

An Analysis of the Works 17th Century Sculptures in Clay The Virgin with the Child is a sculpture from Bahia with a cylindrical base, merely hinting at upholding the crumpled fabric that hides the feet. Its outline is heavy, beginning with a big S displaced to the left of the mantle. Depth is achieved through the volume present in the fabric on the right arm, which holds the Child. Strong hands uphold the Child with the terrestrial globe and a face full of happiness, framed by the long, wavy hair that falls symmetrically down the shoulders. The frontal pose, the weight of the vestments and Mary’s delicate features, with leftover polychrome, lend a Renaissance solemnity to the ancient image.

Fragment of the rosary The fragment is divested of the sacred halo. It is pure art, this technique that molds the golden age in the Paulista imaginary, poetry in clay. With only half a body, this fragment’s figure, with no polychrome, emanates the freshness of clay, which, as fate would have it, was broken. It was turned down for worship. It fled the flames and emerged victorious like a thought to be concluded. The beauty in the piece lies in the idea of what the artisan may pursue: it lacks the hand that holds the Rosary, the smiling Child – with the Renaissance gesture of the step reserved for royalty. And the Virgin’s face appears from tresses like the halo of a honey-colored moon, full of grace, very, very Brazilian: the hand of the saintly artist be with you. It lacks nothing, for it would be imperfect.

The Virgin of the Immaculate Conception is suspended above a flock of little angel heads with asymmetric wings disquieted by rolling clouds. Two scrolls try in vain to organize the angles on the other side on the polymorphous base, the moon tries to accommodate the fall of the fabric on the sides, and straight lines organize the small pedestal in the back. It is characteristic of the master from Rio de Janeiro to uphold the image on a robust, polymorphous pedestal. Right above, the wrinkled tunic falls over the little winged angel heads’ curly hair. The dark shoe is merely alluded to, shadowing the plump, childish cheeks.

The blue tunic’s cloth, richly decorated with golden roses, is imposing. In the front it is tied at the wrists, level with the hands grasped in prayer. It falls making an S on the left side, allowing for a view of the flat lining, red – for virginity – and at the belly, a big curved line points at whom she has just conceived. A reverberation goes through the Virgin’s whole fabric in waves, indicating the movement of the sacred fruit in her womb. The whole left side of the image is more evident. The eye is directed to the scroll, follows the fringe of the moon, continues on the curve of the mantle and winds around the small ribbons of the belt around her waist. It rises through the lines of the positioned hands and opens among the locks of hair to settle on the shining face of happiness.

The small Lady of the Rosary is in the style of Friar Agostinho de Jesus. The polymorphous base is wider than the figure that arises from scrolls, with whimsical little angel heads that try to watch the scene of the Virgin and the Child glued to the body on its left

side, next to the heart. The rumpled tunic at her feet makes deep pleats drawn back to the Rosary highlighted on the S of the mantle.