Around 1815-16 life had become troublesome for Beethoven, then 45 years old His increasing deafness and failing health, compounded by his difficulty at keeping in touch with friends and the public, lead to a certain isolation The works he produced then until he passed from the earthly scene, were the creations of an introvert who was compelled to limit his contact with the outside world, no matter how much he wanted to speak to it This he did in his own language, in the last piano sonatas, string quartets, the Ninth Symphony and Missa solemnis. The sonatas were not his last works for the piano. The huge cycle of the socalled Diabelli Variations were still to come, but the sonatas were his last "words" in so far as piano sonatas were concerned.

Besides their emotional content, the last five sonatas demonstrate an enormous expansion of pianistic possibilities and, also characteristic of the last works of Beethoven's peers Haydn and Mozart, the amalgamation of the classical style with polyphonic elements and contrapuntal techniques

Sonata in B-flat major, Op. 106

Composed in 1818/19 and published in 1819 in Vienna, this sonata is usually referred to as the "Hammerklavier

Sonata" ignoring the fact that the first edition of the A major Sonata bears on its title page the same designation, as do the autographs and revised copies

by Beethoven of Opp 109 and 110 Beethoven always wrote for the Hammerklauier and the use of this term stems from his attempt to employ German words instead of conventional Italian expressions

Beethoven once remarked that he wrote this Sonata under trying circumstances The work combines symphonic spaciousness with concertante virtuosity, polyphonic magnitude and profundity of expression

Only a few particularly significant features can be briefly pointed out here

The symphonic spaciousness resulted in a total of 1167 measures, which not only exceeds those of the Piano Concertos in G major (1044). and E-flat (1074), but also those of the Fourth and Eighth Symphonies (1132 and 1034 respectively). The opening movement expresses strength and joy. There are contrapuntal involvements in the development section, but taken as a whole the movement does not mirror the "trying circumstances"

of which Beethoven spoke. Traces of these circumstances are, however, present in the canonic Trio in B-flat minor of the rapidly moving Scherzo. The Adagio in F-sharp minor

is unquestionably one of the most profound compositions

Beethoven ever wrote

Beethoven was determined to give the sonata an adequate conclusion in the form of a fugal finale with a

three-voice texture This fugue has hardly any counterpart in the musical literature It is by no means a "textbook

fugue The prefatory Largo is motivically connected with the preceding Adagio and also generates a passage from which the fugal subject later evolves The harmonic

richness is extraordinary No less than 11 tonalities are

touched upon Here speaks Beethoven the symphonist who applied the symphonic process and the harmonic

freedom of the development section to fugal procedures

The vigorous conclusion reflects the conquest of adverse circumstances and the rising above the difficulties of life

Sonata in E major, Op. 109

The three piano sonatas bearing the opus numbers 109. 110 and 111 form a triptych which stands out distinctly from the preceding sister works in A major and B-flat, particularly from the later. In the triptych Beethoven turns away from the greatly expanded four-movement design and applying smaller dimensions to the single movements he even reduces their individual segments (exposition, development, recapitulation) in some instances to a bare minimum Contrapuntal technique is applied to all three sonatas and their key relationship is of particular interest Beethoven's fondness of the mediant keys is evident in the triptych Considering the A-flat Sonata as the center-piece then, reading A-flat as ,Psharp, E major appears as the lower and C minor as the upper mediant

Beethoven concerned himself with the last three sonatas between 1819 and 1822 The autograph of the E major sonata bears the heading: "Sonate fur das Hammerklavier, " but it appeared in 1821 as Sonata fiir das Pianoforte und dem Fraulein Maximi/iane Brentano gewidmet. .. The young lady was the daughter of Franz von Brentano, who proved a true friend of Beethoven in financial affairs. Her mother Antonia, her uncle Clemens, the romantic poet and editor of the famous anthology Des Knaben Wunderhorn, and her aunt, the famous Bettina von Arnim, who charmed Goethe, were all great friends and admirers of the composer who knew Maximiliane as a little girl

Recalling the opening Allegro of the preceding Sonata in B-flat the first movement of the E major sonata appears as a study of incredible contrast. The former is 405 measures long, the latter only 99 measures The exposition is, in its number of measures, not only the most concise one in Beethoven's output but also unique in piano literature It consists of only 15 measures, yet within this small framework we encounter sweeping melodic, rhythmic, dynamic and even emotional differences In the development section scales are driven up to the highest regions of the piano Heinrich Schenker, the eminent Viennese theorist, sees in this passage "The manifestation of a soul passionately striving upward and expressing itself ecstatically "

The second movement, Prestissimo, which follows the first without a break, shows the sonata pattern and also displays the features of the Scherzo in a highly original and imaginative manner In the development section the

rapid pace is slowed down and a clearly perceptible motoric contrast to both the exposition and recapitulation is manifest. Thus the development section assumes the character and function of a Trio and this novel combination gives the movement the appearance of a Scherzo.

In the last movement Beethoven reverts to the variation

technique The theme is 16 measures long and there are six variations The basic harmonic character is constantly maintained and there are no variations in a minor tonality The fifth variation is contrapuntal in nature, and the sixth is full of inexhaustible rhythmic diversity and combinations, the culmination of which is overwhelming This variation leads to a restatement of the original theme "Shadowlike and its soul chastened peacefully, the theme

takes leave of us and flies away to that the dream-land

from which it has descended for a while to let us

participate in its transformations and visitations" (Heinrich

Schenker)

Sonata in A-flat major, Op. 110

According to the autograph the sonata was completed at

Christmas 1821 and published in Paris and Berlin in August 1821. The autograph shows many corrections and sketches and studies reflect Beethoven's intense struggle for the realization of his artistic aims It was particularly the last movement which did not satisfy him and to remedy the situation he decided to rewrite it

The Sonata does not open with the usual Allegro but with a rather lyrical movement the delivery of which should be effected con amabilita (gently). Consequently dramatic accents are lacking and expressive cantilena dominates. The piece adheres strictly to the sonata design but the second theme appears in the recapitulation in E major (lower mediant) before the tonality shifts ultimately to Aflat The fast Scherzo in F minor is attached to the opening movement This procedure was tested in the E major Sonata

The last movement is constructively one of Beethoven’ s greatest achievements Seemingly consisting of four sections, it is in fact a fusion or amalgamation of an Adagio and a fugal finale The core of the Adagio is the Aria dolente in A-flat minor the German translation of which-Kragender Gesang was written into the score by the composer This "Mourning Song" is preceded by a short introduction and a recitative Using elements of dramatic (operatic) music to prepare the entry of the "Mourning Song" Beethoven anticipates a procedure he applied later to the finale of the Ninth Symphony and the string quartets in A minor (Op 132) and C sharp minor (Op 131)

The first movement abounds in thematic and harmonic events stemming from the diminished seventh chord. Witness the opening measures of the Maestoso and the vehement unison chief theme of the Allegro. The first movement, too, shows contrapuntal involvements The conclusion of the passionate Allegro is reminiscent of another C minor piece--the overture to Coriolan But in contrast to the latter's crumbling away in C minor the sonata-movement closes in the major key in a spirit of hope and reconciliation which finds its fulfillment in the ensuing Arietta and variations We know from the sketches that Beethoven worked laboriously on this movement and he found the final shape of the theme with the up-beat in 9/16 meter while working on the variations Why he called the 16 measure theme "Arietta" is hard t

fathom There are five variations, t

being in 12/32 meter The fifth brings about the reappearance of the Arietta The extension of this variation leads to the coda, the left hand steadily moving in thirty-second notes almost to the end which is gently attained with the rhythmic motif of the up-beat. Beethoven's last creation in the realm of the piano sonata ends in utmost simplicity and in the spirit of consolation peace and hope

HAYDN: Piano Sonatas 31 & 32

SAINT-SAENS: Étude en forme de valse, Op.52; Rhapsodie d'Auvergne, Op. 73

MOZART: Piano Concerto No. 8

CLEMENTI: Three Sonatas from Six Sonatas, Op. 4

Mine was the privilege to create the first-

ever Festival of Neglected Romantic Music

(at Butler University, Indianapolis) What an

exciting project it was! During my decade as

its director, the Festival explored and re-

pre'miered dozens and dozens of big works

by such then-unplayed composers as Alkan,

Bourgault-Ducoudray, David, Dreyschock,

Ernst, Guiraud, Henselt, Herz, Joachim,

Moszkowski, Napravnik, Paderewski, Pierne,

Raff, Rheinberger, Rombert, Rubinstein,

Servais, Sgambati, Spohr, Thalberg,

Wieniawski, and many others. The one that almost got away was Hummel

Pupil of Haydn, Mozart, Clementi, and Beethoven and teacher of Mendelssohn, Hiller, Henselt, and Thalberg, Hummel was a

key figure in the development of romanticism He created the most profuse and elaborate keyboard idiom before Liszt, set the stage for Chopin's jewel-like ornamentation and be! canto melodic lines, wrote the era's "bible" on piano technique, and composed reams of elegant, sometimes astonishingly brilliant music

"Elaboration, " Bryce Morrison tells us, "rather than classical economy was Hummel's aim, and his execution of a novel profusion of ornaments was viewed with envy and disbelief " --Frank Cooper, MHS Review, 1987

To disappear - such a fate for anyone. Consider this fate for a composer, whose job

seems to be to alter our universes for a moment, and create an atmosphere that we can remember in our own way - respectfully,

rapturously, however. They toil, they produce and then we forget.

While researching other works for an earlier

issue of The Review this year, I stumbled upon the concept that one of the reasons that the works of composers of the Baroque

era didn’t make much effort to retain scores was that the music wasn’t meant to be

performed much after the initial performance. I don’t know how the composers felt about

that but it actually sounded logical

I write now more about this recording as well

as the music of Hummel. This 5 LP set, 3

hours and 36 minutes long has been out of

print, as best I can tell, for over 50 years

Many reasons I suppose I can explain why

the recording was unreleased. But I found

Hummel to be an interesting case. In a world

where there’s multiple recordings of everyone’s everything in classical music, there’s few recordings of many of these works

Play “drop the needle” (oh, how old I feel when I say that) and you can find moments of tremendous beauty that makes you feel as if you’ve discovered Beethoven and Mozart’s musical sibling Hummel then drifts into habits a music student of any caliber would

have avoided...so this will be a treasure hunt, but one a music lover should definitely take!

JOHANN NEPOMUK HUMMEL

CHAMBER MUSIC

Hans Kann, piano

Albert Kocsis, violin

Franz Bartholomey, cello

Karl Stierhof, violin

Georg Weinhengst, flute

Edith Bauer-Slais, mandolin

Zlatko Topolski, violin

AN AN EXCLUSIVE

5 LP SET - OUT OF PRINT 5 LP SET - OUT OF PRINT FOR 60 YEARS FOR 60 YEARS

INCLUDES THE FOLLOWING WORKS:

Trio In E-Flat Major, Op. 12

Trio In F Major, Op. 22

Trio In G Major, Op. 65

Trio In G Major, Op. 35

Trio In E Major, Op. 83

Trio In E-Flat Major, Op. 96

Hans Kann, piano

Albert Kocsis, violin

Franz Bartholomey, cello

Sonata In A Major, Op. 104 For Cello & Piano

Hans Kann, piano

Franz Bartholmey, cello

Sonata In E-Flat Major, Op. 5 No. 3 For Viola & Piano

Hans Kann, piano

Karl Stierhof, violin

Sonata In D Major, Op. 50 For Flute & Piano

Sonata In G Major, Op. 2, No. 2 For Flute & Piano

Hans Kann, piano

Georg Weinhengst, flute

Sonata In C Major, Op. 37 For Mandolin & Piano

Hans Kann, piano

Edith Bauer-Slais, mandolin

Sonata In B-Flat Major, Op. 5 No. 1 For Violin & Piano

Hans Kann, piano

Zlatko Topolski violin

$4.99 EACH

STRAUSS & RESPIGHI: VIOLIN SONATAS

David KIM, violin; Gail NIWA, piano

STRAUSS & GRIEG: CELLO SONATAS

Marcy ROSEN, cello; Susan WALTERS, piano

$4.99 EACH

Robert MURRAY, violin

Daniel GRAHAM, piano

The Americans, who had in the 1870s not yet acquired a proper awe of genius or a proper knowledge of outlandish tongues, called him, affectionately and accurately, "Ruby "

Anton Rubinstein--no relation to Artur--was the first simonpure, uncontested, unabashed, top-grade virtuoso superstar most of them had ever encountered, though there had been such people as Henri Herz, the self-styled "Lion Pianist" Leopold de Meyer, who threw himself all over the keyboard, and, of course, the home-grown Gottschalk In point of fame, Ruby was second only to Liszt himself--who, early in his career, apparently rejected Rubinstein as a pupil. During 1871-2 Rubinstein played 215 concerts across the face of America, together with Henryk Wieniawski, a violin virtuoso who found himself playing second fiddle Rumpled, stocky, pugnacious looking (said to resemble Beethoven), Ruby made the piano bellow, scream, moan, and say "uncle" in a way that drove his audiences into a frenzy; few noticed or cared that he, as the old saw has it, left out enough notes to play another concert He went home with more than $40,000 in gold coin (he did not trust paper money), which was a fortune by today's standards--and worth heaven knows how much on today's gold market! --David M Greene

(we’re impressed if you have)

JOHN SEBASTIAN SR. PLAYS JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH

Works arranged for harmonica and piano

Andre HADGES, violin Vladimir WEISMAN, piano

There were only four mourners at his funeral, yet this was the man who established the piano as a concert instrument in Britain, who introduced sonata form to his adopted nation, and who taught the child Mozart

how to write symphonies and concerti His is a curious story

As the youngest son of Johann Sebastian and Anna Magdalena Bach, Christian was one of his father's last pupils. Three harpsichords were his legacy. At

15, the boy was absorbed into the household of his brother, Carl Philipp Emanuel, who was in the service of Frederick the Great. The tutelage Christian received in Prussia was carried even further in Italy, where he studied in Bologna under the famed Padre Martini

Christian's considerable skill at the keyboard was

soon eclipsed by his success as a composer His operas at Naples and Milan, even more than his church music, took the Italians by storm and led to

lucrative employment far away in London Thus, Christian became the most traveled member of his distinguished family

When the English enthusiasm for Italian opera waned, Christian promoted the then-novel institution of public concerts, in a hall with special murals by his artist friends Thomas Gainsborough, Benjamin West, and Giovanni Cipriani. On his musical taste, London's concert life developed greatly, and stabilized at a high level Bach's social contacts helped, of course He was music master to Queen Charlotte (who also was German-born), so he had access to the whole court He knew such theatrical figures as David

Garrick and Richard Brinsley Sheridan, and frequented their circles The patrons of his concerts thus included many prominent figures They loved his music

Using strings, oboes, horns, and, of course, harpsichord continuo (flutes appear just once), these masterpieces have three movements apiece The first movements always bustle with energy and high spirits in their abundant dynamics and free use of the new sonata form The second movements--Andantes and Andantinos--offer ineffably sweet, little melodies as felicitous as anything written on the Continent at that time The finales arc dancelike in form and mood--Menucts, Gigues, Cotillions--and instantly set our toes to tapping.

Being, in the words of his era's most indefatigable commentator Dr. Charles Burney, "the first composer who observed the law of contrast, as a principle, " Bach never fails to hold our 20th-century attention through the contrast of themes, keys, textures, tempos, and forms No wonder his music was in great vogue two centuries ago A dozen years after his death, Bach and his adorable little symphonies were eclipsed by the huge symphonies of a newcomer to London, Joseph Haydn Even in the last year of his life, Bach found himself taken for granted and his light waning His warm friendship, ebullient works, and historical significance soon were forgotten, but are known again through the miracle of recording and such splendid performances as these

Johann Christian BACH

Symphony in G Minor, Op. 6, No. 6 WC 12

Harpsichord Concerto in E-Flat Major, Op. 7, No. 5, WC 59

Henriette BARBÉ, harpsichord Camerata Zurich Räto TSCHUPP, conductor

$4.99 $4.99

Johann Christian Bach was

Johann Sebastian’s more

successful son - the most

successful member of the Bach

family, perhaps commercially and in reputation.

The Symphony in G Minor strongly influenced Mozart’s more famous G Minor Symphony No. 40.

The harpsichord concerto recalls Haydn, with gallons of charm and virtuosity.

Bach: Trio Sonatas

Members of the Vienna Chamber Orchestra

Bach: Sonatas & Partitas for Violin Solo Christian Tetzlaff

Excerpts from The Fairy Queen New York Early Music Ensemble

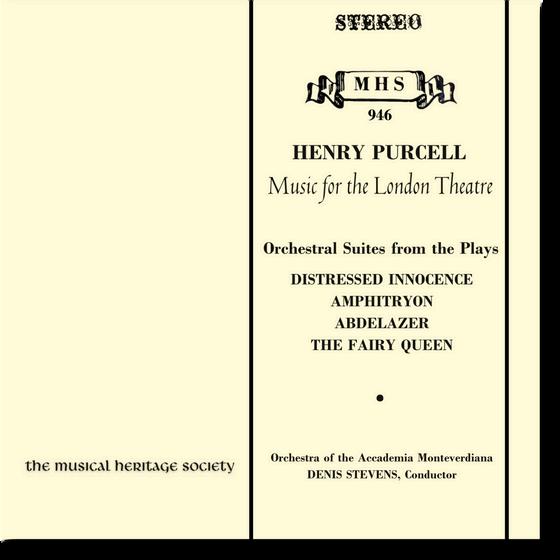

Vivaldi: Concertos & Sonatas

Max Goberman, New York Sinfonietta (Volume 12)

Vivaldi: Concertos

Max Goberman, New York Sinfonietta (Volume 16)

LULLY: MUSIC TO MOLIERE PLAYS Austrian Tonkunstler Orchestra

ALBICASTRO & BOYCE: CONCERTI Accademia Monteverdiana

Features music for solo guitar

Transcriptions for Guitar of music by Scarlatti, Bach, Mozart, Soler, Mendelssohn

Lute Music by John Dowland

Beautiful music for early evening listening

Handel: Harp Concerto

Debussy: Dances Sacre et Profane

Mozart: Divertimenti

Mendelssohn: A Midsummer

Night’s Dream (excerpts)

Vivaldi: “Summer” from The Four Seasons, Concertos from L’estro Armonico

Bach: Brandenburg Concerto No. 5

Debussy: Prelude de l’apres midi

Respighi: Pines of Rome

Faure: Papillion

Franck: Violin Sonata (arr. for cello and piano)

Orchestra of St. Luke’s

The Aulos Ensemble

Shlomo Mintz, Israel Chamber Orchestra

Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center, Osian Ellis

Houston Symphony Orchestra

Baltimore Symphony Orchestra

PAGANINI: 24 CAPRICES

ARR. FOR GUITAR

BY ELIOT FISK

SCARLATTI: 30 KEYBOARD SONATAS

JOHN BROWNING, piano

ONE OF MHS’S FINEST AND BEST-SELLING RECORDINGS!

Astounding! Even Paganini wouldn't have believed that it could be played on the guitar. An enormous accomplishment that will raise the level of guitar playing. Has to be heard to be believed. -Ruggiero Ricci

CELEBRATE WITH THE HARVARD GLEE CLUB

A pianist known for modern and romantic repertoire tries his hand at 30 sonatas from the Baroque era.

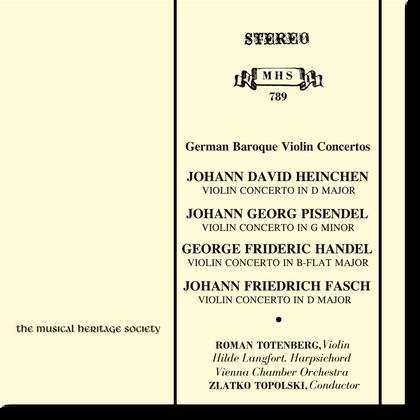

This great American violinist/teacher had a famous violin and a famous “bowing” technique. Lushly recorded, and Romantic at heart.

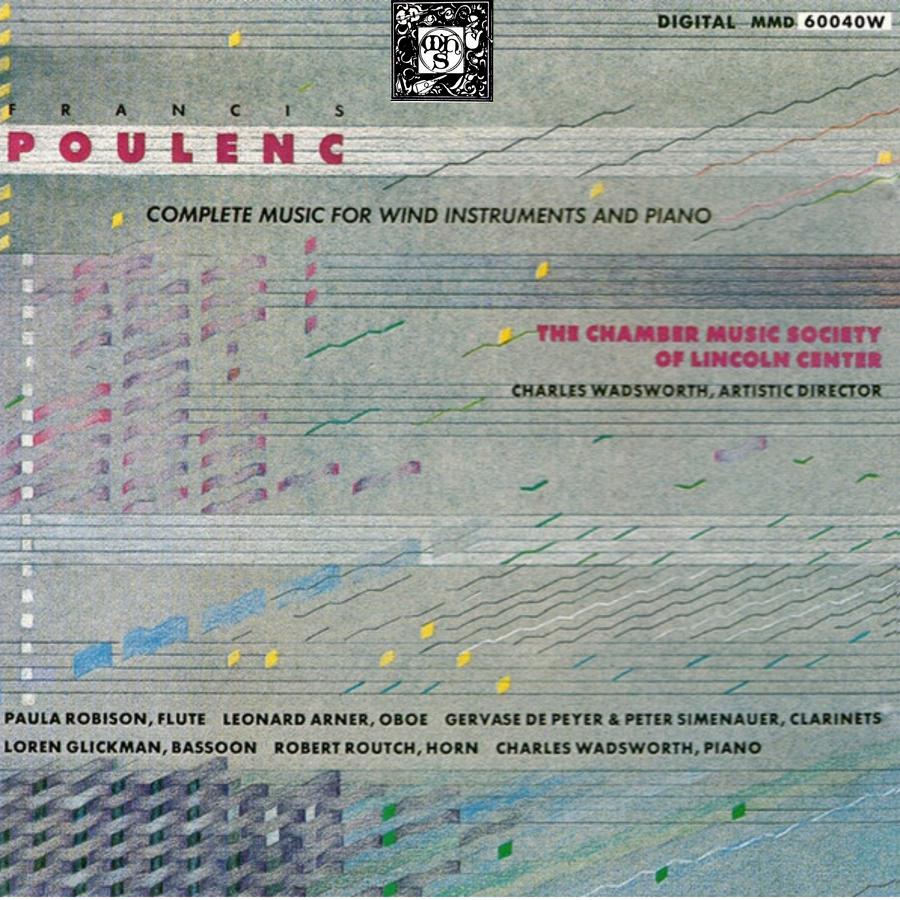

The Chamber Music Society

Of Lincoln Center

Charles Wadsworth, piano

Paula Robison, flute

Leonard Armer, Oboe

Loren Glickman, Bassoon

Gervase de Peyer, Clarinet

Robert Routch, French horn

Nicely Recorded Performances:

Poulenc's Complete Music for Wind

Instruments

by David M Greene

eness of myth--in this instance, the one that all artists are either born poor or have poverty thrust upon them by their impractical approach to life

Poulenc was the next-to-youngest of that constellation of post-WWI French-born composers incorrectly dubbed Les Six by a reviewer named

Collet The eldest, Louis Durey, never really identified himself with the others and quickly dissociated himself from them Germaine Tailleferre (1892-1983) attracted little attention Georges Auric, Poulenc's junior by five weeks, was best known as a film composer

The Big Boys of the six were, in their heyday, thought to be Honegger and

Milhaud No one took Poulenc seriously, except a few rather specialized and sophisticated singers who doted on his songs, the texts of which were often far-out and the musical language of which was closest to that of the music hall

In his superbly evocative notes to this album, Ned Rorem (himself no mean writer of songs and in some ways the inheritor of Poulenc's mantle) points out that, contrary to all reasonable expectations for a man regarded in his day as a clown, Poulenc's current reputation has outdistanced those of all the rest Not a single one of the others, for example, ever had an opera produced at the Met, which in recent years has not only staged two of Poulenc's but also revived them Rorem explains this phenomenon, somewhat bitterly, by saying that the reason for the volta face is that

"over the past 20 years the public has been permitted to claim, with a straight face, that superficiality is a profound attribute "

In quantity and quality, his wind chamber music is the most notable since Mozart. The evidence is eloquently pre

ed his

iousness And he could be quite serious, as he was in his only full-length opera, Dialogues des Carmelites, and in

religious faith Poulenc's output was not large There were the three operas, as well as four ballets, and a good deal of music for plays and films, much of which is unpublished and most of which is neglected Apart from four concerti for keyboard instruments, the orchestral work is mostly bits and pieces There is about a score of choral works (some of them collective) and about 35 piano compositions ( Poulenc was himself a good pianist, if not a virtuoso)

Then there are the songs --perhaps the most notable body of such works from any 20th century composer (do I hear cries of "Ives!" or "Warlock!" or even "Rorem!"?), though in all they fill only five LPs Finally there is the chamber music: 14 compositions, which, except for a guitar piece and a sonata each for violin and cello, all involve wind instruments

Poulenc, it appears, preferred winds to strings (Rorem says he looked like a trumpet and sounded like an English horn), and is said to have sent some of his orchestrally intended pieces out to others for instrumentation Again,

Rorem notes that Poulenc's style was born full-blown and never changed so that though 44 years separate the two-clarinet Sonata from that for clarinet and piano, it could have been a month I don't know that I agree: the late works seem to me less irreverent and more introspective, but what do I know?

And if the style does not change, there is infinite variety And what is the style? Thomson's characterization of how the "rich" composer usually writes is not far off target: "He goes in for imagistic evocation, witty juxtapositions, imprecise melodic contours, delicacy of harmonic texture and of instrumentation, meditative sensuality tenderness about children, evanescence, the light touch, discontinuity, elegance " N O W S T R E A M I N G

McLellan, Washington Post, 1984

Le Monde: "I

La Vie Medicale: "Wi

L'humanite Dimanche: "An interpretation beyond comparison from an American ensemble that joins the greatest Interpreters of their generation. "

Diapason: "Excellent interpreters of one of the most French musicians there is."

Echo du Centre: "A magnificent double album ...

All those who especially love Francis Poulenc will be overwhelmed by the interpretation given by the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center”

Some well-known composers, when they die, become immediately less well-

known...Yet some, seemingly overnight grow much more famous than during

their lives They are the rarest Indeed, besides Bartok, is there anyone besides Poulenc? --Ned Rorem (from the liner

notes for this recording)

A chap whom I met a couple of years ago called the other night to say that he had moved recently to

my area and was seeking suitable employ In the course of our talk, he inquired if I still wrote for

MHS Hearing that I (after a fashion) did, he apologized for having let his membership lapse It was the third such apology I had had in a week Well, I regret, of course, that we can't stimulate

everyone to stay on board, but frankly I like to be reminded that there's an active turnover It tells me

that I can, after a suitable interval, risk repeating myself. Since we put out a Gregorian record only every so often, I judge that the required interval has passed.

For those who don't know, Gregorian chant is the official music of worship in the Roman Catholic Church. It is said to be very old, and takes its name from the sainted Pope Gregory (or Gregorius) the First, who died in 604 A D after a 14-year tenure of office Gregorius was apparently gregarious: at least he was a great philanthropist and social reformer, promoted monasticism (which helped keep people off the streets and curbed their natural tendency to overpopulation), and did much to Christianize the barbarians in western Europe, on the grounds that a universal faith would help keep them from massacring everyone in sight

Pope Gregory made important reforms in the Mass, and in that connection he allegedly composed the music that bears his name, according to hoary tradition. But when more rational minds found this unlikely, it was said that he codified the music current in the Roman Church of his day, or at least ordered that done Whatever may be his contribution, the fact is that no music has come down to us from any period earlier than 200 years after Gregory's death, and a good deal of the body of chant was composed even later than that

.

There are certain basic characteristics of chant It is entirely melodic: all members of the choir sing the same unharmonized tune Such tunes are not diatonic but modal, i e they do not subscribe to the rules of major and minor, but are based on a series of scales that may be duplicated by playing the "white" keys on the piano from any note up to its octave and back. (In this way the Dorian mode runs from D up to the next D and back. Gregorian melodies generally cover no more than an octave, may be quite florid, and tend [ on the printed page] to "arch.")

I cannot comment on the effectiveness of Gregorian chant as an implement of worship Considered as music, it has its passionate admirers And, indeed, it has a sort of unearthly purity about it, and gives a peaceful sense

GREGORIAN CHANT IN THE ABBEY OF SAINT-ANN OF KERGONAN

BENEDICTINE MONKS OF THE ABBEY OF SAINT-ANN OF KERGONAN

DOM LOUIS LE FEUVRE, director

Serenity, and humble prayer expressed in simple musical forms.

This peaceful and beautiful recording, made in France, is a Musical Heritage Society best-seller that has been out of print for decades.

One of the many roles required of this writer

for the Musical Heritage Society is that of archivist (frankly, there isn’t a role that this

writer doesn’t fill, yes I also answer your

emails and chat messages as well). By our

count there are over 1000 Musical Heritage

Society recordings (possibly 2000) that are

unreleased. And we’re not talking about the

thousands of recordings that were issued from great labels like Erato, Chandos, Hyperion, Amon Ra, and the like. No, these

were recorded by, or recorded by someone else and purchased by MHS.

Which leads me to my question - what do we have here with this recording, MHS 1057,

Alessandro Scarlatti: Serenade a due: Clori e Zeffiro? This recording came across my desk and I said, great, there is an enthusiastic segment of our members who might like an obscure work by Alessandro Scarlatti

Sure - if this work actually IS a work

by A. Scarlatti. What makes me wonder? Well a basic internet search turns up NO mention of this

work Other work titles of Scarlatti vocal works are similar, but even a

more exhaustive search finds NO

listing of a work by this name.

More things that make you go hmmm:

1. This is the only recording by the English Chamber Orchestra in the entire MHS catalog.

2. The conductor, while known to MHS members of the 1960 and 70s, seemingly never performed or recorded outside the US.

3 The note writer and resident composer, MHS’s Douglas Townsend, admits that the score was not in the composers’ hand AND that Townsend wrote out the figured bass.

4. The work was composed in 1706 for an “unknown” event, where an obscure Marquis had purchsed his title from a Duke

5. Conspiracy theorists, here’s one for you: almost all of the participants are dead, including two who died this year. Soprano Wendy Eathorne, who didn’t answer an email request

A clever fake or an utterly forgotten work? Or, an utterly forgotten fake? YOU DECIDE. (PS: note that it’s NOT April Fools Day.)

Artwork: Zeffiro E Clori by Jacopo Amigoni

Artwork: Zeffiro E Clori by Jacopo Amigoni

SerenataaDue:

ClorieZeffiro

Wendy EATHORNE, soprano

Maureen MORELLE, mezzo-soprano

THE ENGLISH CHAMBER ORCHESTRA

Geoffrey PRATTLEY, harpsichord

Frederick STORFER, conductor

for events, normally outdoo

, utilizing a small orchestra and usually one or two singers. Works of this type were the “chamber-ist” of chamber operas.

This work - and we really are not sure if this is actually

between Clori, goddess of the flowers and Zeffiro, god of the west wind. Typical for its time

frame, this pleasant work flows by, entertainingly!

Will the real pianoforte please identify itself?

The terminology for this instrument (not pictured in the middle of p. 29 in Release 365) is something I have just spent some time trying to sort out. The instrument in the picture was, during Clementi's lifetime, the only piano there was. He and his colleagues called it "piano," "pianoforte," or "forte-piano" more or less interchangeably. In our day we call its descendent the "piano." But the instrument we play now is really no longer in the same genus as that one Clementi (and Mozart too) was writing for; they are two separate instruments. Thus they should have two separate names. We are pretty well stuck on using the term "piano" for the one manufactured today, and for perhaps the past 100 years. And we have been coming around lately to settling upon "fortepiano" as a name for the 18thcentury version of this family (not "pianoforte"; sorry Signor Clementi). That seems to be a moderately adequate (if not very classy) way to distinguish between these two relatives. However, we may have a real problem on our hands if those advocates of the 19th-century (post-Beethoven) piano decide that their "missing-link" instruments deserve to be classified as a separate genus also, and thus require a name of their own. What's left? Maybe the solution suggested in the latest issue of Experimental Musical Instruments by Ivor Darreg would be best. He says his typewriter is very good at inventing names. How about pinao? or paino? Pinaofrote? the possibilities are legion.

Anita T. Sullivan, Corvallis, OR

Having sat on the sidelines for a while now I feel compelled to chip in with some editorial comments about MHS and some members letters.

First of all, people who fancy themselves to have elite taste in "good" music really tip their hand when they complain about all the magazines going "off the deep end" in their coverage of non-"classical" material (Ann M. White, Walter D. Foster). What is "going off the deep end,'' allowing half as much exposture to non-European music as to Europeon music? Is "classical" music, by some miracle of cultural superiority, the best in the world? If the music is original and good, who cares what label is tied around its neck? Virtually all the music offered in the Review employs the diatonic scale and is built on "Western" principles. When one considers the variety and complexity of all the musics around the world--for example, the degree of precise pitch in Oriental music and the rhythmic complexity of African music--the common ground that both Bach and Herb Ellis stand on seems huge.

Second, the small amount of jazz and other non-"classical" music MHS has offered is an extremely conservative sampling of the other music "out there," and while I understand the Society is dedicated primarily to European music, little Charles Mingus, George Russell, and Gil Evans wouldn't hurt. Again, if people who profess to love Stravinsky and Beethoven find this other music incomprehensible, I wonder if they merely like the "tunes" and "sound" of Stravinsky and Beethoven.

Third, for as long as I live, I hope I never hear another Tchaikovsky Piano Concerto, or Beethoven Fifth, or Vivaldi Four Seasons, or an 1812 ... Adults refer condescendingly to young people who listen to the same pop over and over again, but what are they doing? Keep the obscure wind pieces, the underrated composers (hey, how about some more d'Indy?), and the never-previously released-in-this-country recordings coming! But we don't need another Eine kleine Nachtmusik, even if it is played on the very instruments Mozart's housekeeper is believed to have dusted every week.

Aside from all that, I will only add what virtually every reader says, namely. "Bravo·· to David Greene!

John Grabowski

Philadelphia, PA

I would like to thank John Grabowski for his astute comments on the subject of "Western" music compared to "Oriental" music (release 387). It is true that, for example, the music of India, China, and Japan employs intricate systems of music theory vastly more complicated and expressive than that of Western music. Not only are atonality and complex rhythmic devices used, but many ornamental quarter-tone variables and subtones of the quartertone technique are utilized. Easily, the ragas of India could be described as answering "a plea from the soul," creating "a lovely sound rainbow," playing "on heartstrings," and, especially to the people of India, "respond[ing] to a person's subconscious need for something not truly earthbound." As far as Western music is concerned, the same could be said of Utrenia by the contemporary Polish composer, Krzysztof Penderecki.

When I studied music appreciation in the Oklahoma City University School of Music, my textbook, The Musical Experience by John Gillespie, included chapters on "Non-Western Music" and "Folk Music, Pop Music" as part of "classical" music education. The music of ancient Africa and ancient Greece was highly improvisatorial, and had its underpinnings in common. Throughout the centuries, African music preserved this common knowledge of improvisation; in Europe, this kindred knowledge was preserved in church and folk music. The same ancient historical basis that helps to give modern black African-derived jazz its improvisatorial structures is, also, the same basis on which baroque ornamentation and improvisation were constructed. The same basic principles of improvisation used by Buddy Bolden and Miles Davis in jazz enabled Mozart and Beethoven to ad lib ornamentation, as well as concerti cadenzas, during public performances!

Many composers, from the time of Martin Luther (and before) to Aaron Copland, have venerated traditional, popular, and folk music, deriving thematic material from them for songs, sets of variations, movements of symphonies, etc. Martin Luther wrote church hymns on the tunes of tavern (beer-drinking) songs--these were later coined into baroque church cantatas and organ works by J.S. Bach. What makes rock music is the "rock beat"-and the rock beat was used in certain Gospel and religious music long before the advent of the modern rock music era.

A person who has not stagnated, and is interested in continuing his music education, will not allow bias, or limited cultural perspectives, to restrict his personal knowledge and growth! The challenge for us today is to develop an equal appreciation for the "old and new, odd and familiar, baroque," etc. Even though an individual may prefer music of one culture, or genre, or time period, over that of another, he should not unduly criticize what he does not understand or appreciate.

For those of us who want to evolve and advance ourselves, unfamiliar Western compositions and non-Western music provide an excellent opportunity for us to do so, in addition to acquaintance with the usual "war horse" works offered on the concert stage and redundant available recordings.

David C. Whitaker Enid, OK

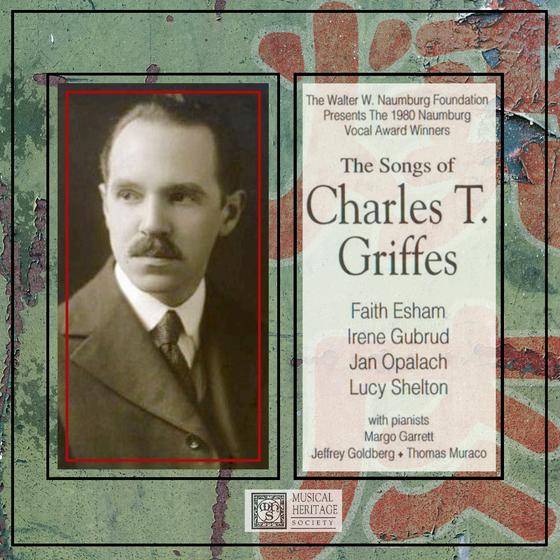

Winthrop Sargeant, the music critic for the New Yorker magazine for most of the 20th century said he wrote

“some of the most beautiful music ever composed by an American ”

The even more eminent Gilbert Chase, who wrote the first book that told the history of American music as

grounded in folk traditions and NOT in the music hall, said “his major works

are American classics. His songs are among the best we have. ”

So...why is the composer Charles

Tomlinson Griffes consigned to heroic efforts such as this entire MHS recording?

This recording is a selection of his

finest songs, so it attempts to refocus

attention away from the small

reputation he had in his lifetime, coming from his orchestral music.

A true Horatio Alger story, Griffes

grew up in Elmira, New York, showed significant musical talent and, in part

due to support from wealthy music

lovers AND the “pass the hat”

donations from his fellow

townspeople, Griffes went off to study

in Europe.

This story doesn’t end well and is a fine cautionary tale for anyone considering a life of writing music

Despite early success, he struggled to get a foothold at any level. There’s a fine anecdote here that illuminates -

when Griffes’ publisher rejects all of his newest works, we’re reminded that

Charles Ives simply published all his works himself and allowed anyone who wished to perform them for free.

(PS sure! try that now...)

Griffes heard and loved much of the newest music, becoming one of the

American champions of Stravinsky, and Milhaud.

So what will you get listening to the music of C.T. Griffes? A buried

American Schubert? Well no You have a melting pot of composers, ranging from Wolf, Schubert and Debussy, combined in an original

sound. For those who left modernity behind years ago, you’ll find a late

Romantic here, not a “new man” of the 20th century.

Faith ESHAM, soprano

Irene GUBRUD, soprano

Jan OPALACH, baritone

Lucy SHELTON, soprano pianists

Margo GARRETT, Jeffrey GOLDBERG & Thomas MURACO

featuring the 1980 Naumberg Foundation Award Winners

The pride of Elmira, New York, Charles Tomlinson Griffes’s work has been praised as “part of the small and select company of songs written in English” in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

Griffes established a reputation via programmatic symphonic works, but his songs never reached an audience, as his studying in Europe led him to write music for poetry in multiple languages.

But his early death at age 35 left a legacy more about promise than realized greatness.

He struggled in obscurity in life, but his reputation began to coalesce after his death Virgil Thomson wrote “Griffes’s music is first class and can be played all through. His death seems somehow unfair.”

SCHUMANN: WORKS FOR CELLO & PIANO

Jascha BERNSTEIN, cello

Jörg DEMUS, piano

There is a handsome bronze bust of Robert Schumann in the lovely park that surrounds the opera house in Dusseldorf That opera house was not there in his day In fact most of present-day Dusseldorf wasn't there, the Allies having gloriously laid it flat during the last Major Unpleasantness One wonders what it was like then Today it hums with industry and traffic and bristles with money A grand esplanade, featuring some fancy waterworks, cuts through the center of town, leading, as I recall, to a lake or lagoon or something of the sort overflowing with waterfowl The downtown streets are lined with banks of incredible magnificence; we ventured into one to cash a traveler's check, got lost in the pile of the carpeting, and had 'to be rescued by a safari of clerks wearing cutaways and diamond stickpins.

When Schumann went there in 1850, it must still have been a relatively small and sleepy riverport, though it was already noted for its music festival. (The industrialization did not really get under way for another couple of decades ) Despite the fact that he was being hired as virtual overlord of Dusseldorf musical life, Schumann had misgivings--largely about the presence there of a public looney-bin, whose inmates he preferred not to have to observe Four years later, after being visited by angels and hyaenas

and taking a desperate plunge into the Rhine, he had himself committed to a private asylum where he died at forty-six Nor had the Dusseldorf experience been any bed of roses After they had hailed the conquering hero, his choir and orchestra became increasingly dissatisfied with him, and finally refused to play and sing for him at all. Not that you could blame them--the poor man often stood there, baton poised, staring into space, and on one occasion went on obliviously conducting after everyone else had dropped out.

Schumann's troubles, both inward and outward, seem not to have seriously impaired his productivity, for he went on turning out music and babies at his usual rate In fact the creative upswing that we suspect contributed to the emotional collapse began in 1849, the year that Ferdinand Hiller gave up the Dusseldorf conductorship and nominated Schumann his successor It was in this year that the three works on the present record were composed

The ''5 Pieces in Folk-Style'' constitute, so far as we know, the only work that Schumann specifically designated for 'cello and piano, though later he was to turn out a 'cello concerto Charming and unassuming pieces, they do not show the decrease of spontaneity found in some of the later works Casals recorded them, as did Rostropovitch (with Benjamin Britten accompanying!), and I figure that's what good enough for those gentlemen must have something going for it. The '' Fantasy Pieces" were written for clarinet, the composer suggested violin or 'cello as possible alternatives. He made the same provision for the

Adagio and Allegro for horn and piano, which turns up as

a space-filler in every recorded horn recital you can name

It's nice to have these second-choice versions available,

though if the perpetrators of this record had really wanted

to strike a blow they would've unearthed the

accompaniments Schumann wrote for the Bach 'cello

suites

Schumann: Violin Sonatas

Roman TOTENBERG, violin

Artur BALSAM, piano

Brahms: Variations

Misha DICHTER, piano

Brahms: Cello Sonatas

Aldo PARISOT, cello

Elisabeth SAWYER, piano

Schumann: Symphony No. 4

Beethoven: Symphony No. 8

Royal Philharmonic

Brahms: 4 Symphonies

Utah Symphony Orch.

Brahms: Violin Sonatas

Robert MANN, violin

Stephen HOUGH, piano

Romantic Music for Viola & Piano Isomura, Kahane

Brahms: Chamber Music Browning, St. Luke’s

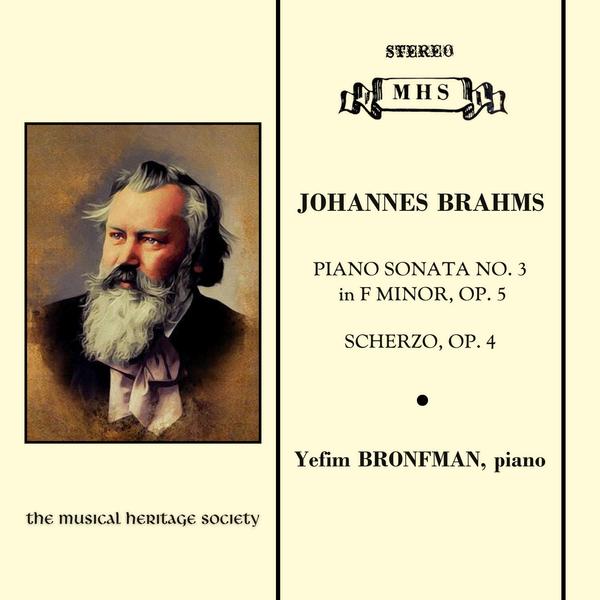

Brahms: Piano Sonata #3

Yefim BRONFMAN, piano