Iceland Review

COMMUNITY, CULTURE, NATURE — SINCE 1963

Capelin is crucial to Iceland’s ecology and its economy.

Maria Alyokhina on Pussy Riot’s first-ever gallery exhibition.

Capelin is crucial to Iceland’s ecology and its economy.

Maria Alyokhina on Pussy Riot’s first-ever gallery exhibition.

NEWS IN BRIEF 6

ASK ICELAND REVIEW 8

IN FOCUS

FERRIES 10

CULTURAL APPROPRIATION AT THE ICELANDIC OPERA 14

FICTION

AN EXCERPT FROM THE QUIET GAME BY HALLA ÞÓRLAUG ÓSKARSDÓTTIR 120

PHOTOGRAPHY

DO YOU BELIEVE IN MAGIC? 100

LOOKING BACK

TO THE MANOR BORN 48

At the turn of the 20th century, a French aristocrat rattled Reykjavík society.

FROM THE ARCHIVES

AUTHOR AND NOBEL LAUREATE

HALLDÓR LAXNESS 36

Living from 1902 to 1998, Halldór’s books were synonymous with the history of the 20th century.

ART

VELVET TERRORISM 18

Maria Alyokhina on Pussy Riot’s first-ever museum exhibition.

SOCIETY

MAN OF THE PEOPLE

Journalist Gísli Einarsson champions Iceland’s countryside folk. 28

INNOVATION

FULL HAUS 88

A new hub in downtown Reykjavík is giving creative workers room to grow.

MUSIC

POWER PLAYER 62

Diljá is ready to take on Eurovision.

MUSIC

THE WONDERER 78

Júníus Meyvant and his many tangents.

INDUSTRY

NET PROFIT 40

Capelin is crucial to Iceland’s ecology and its economy.

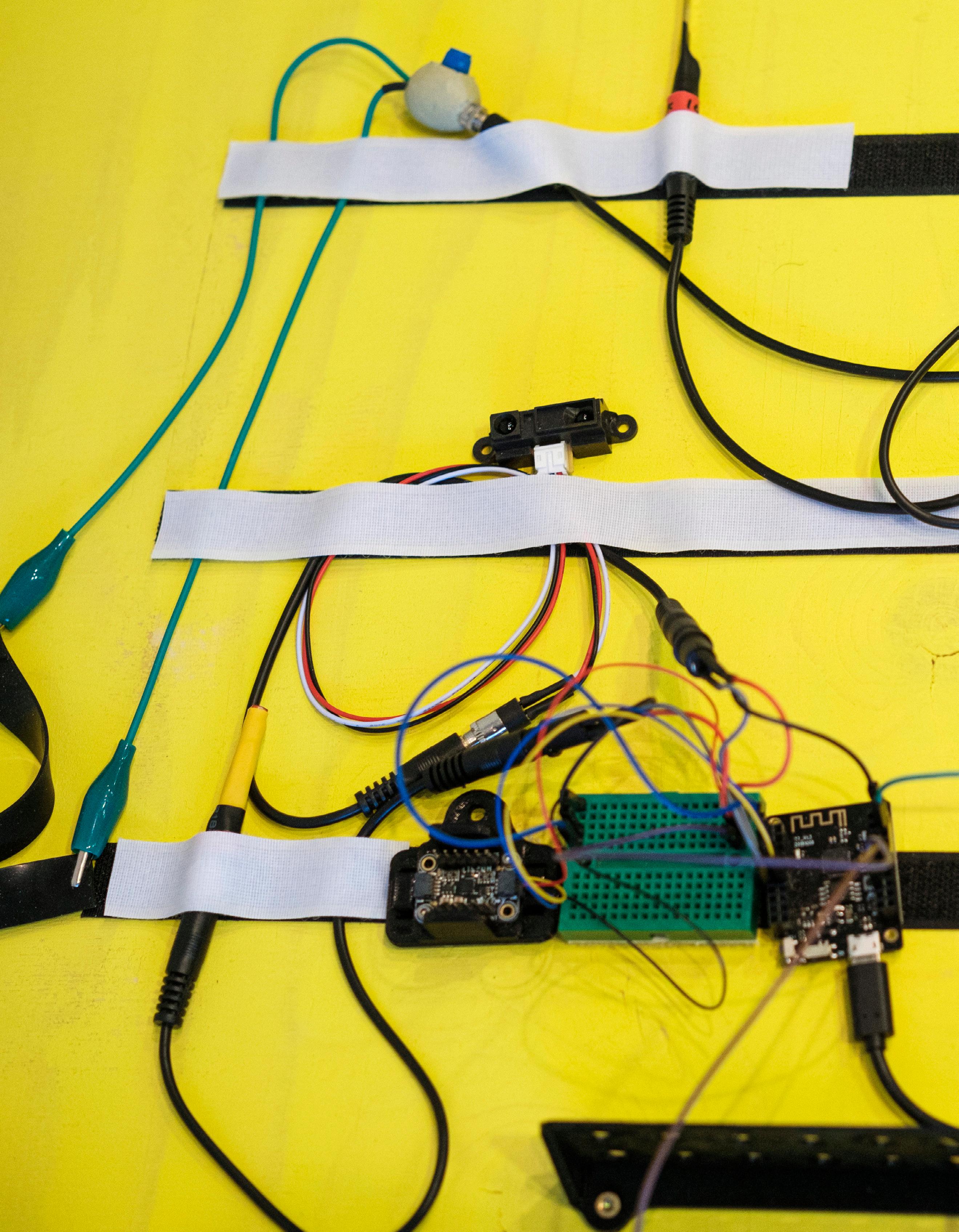

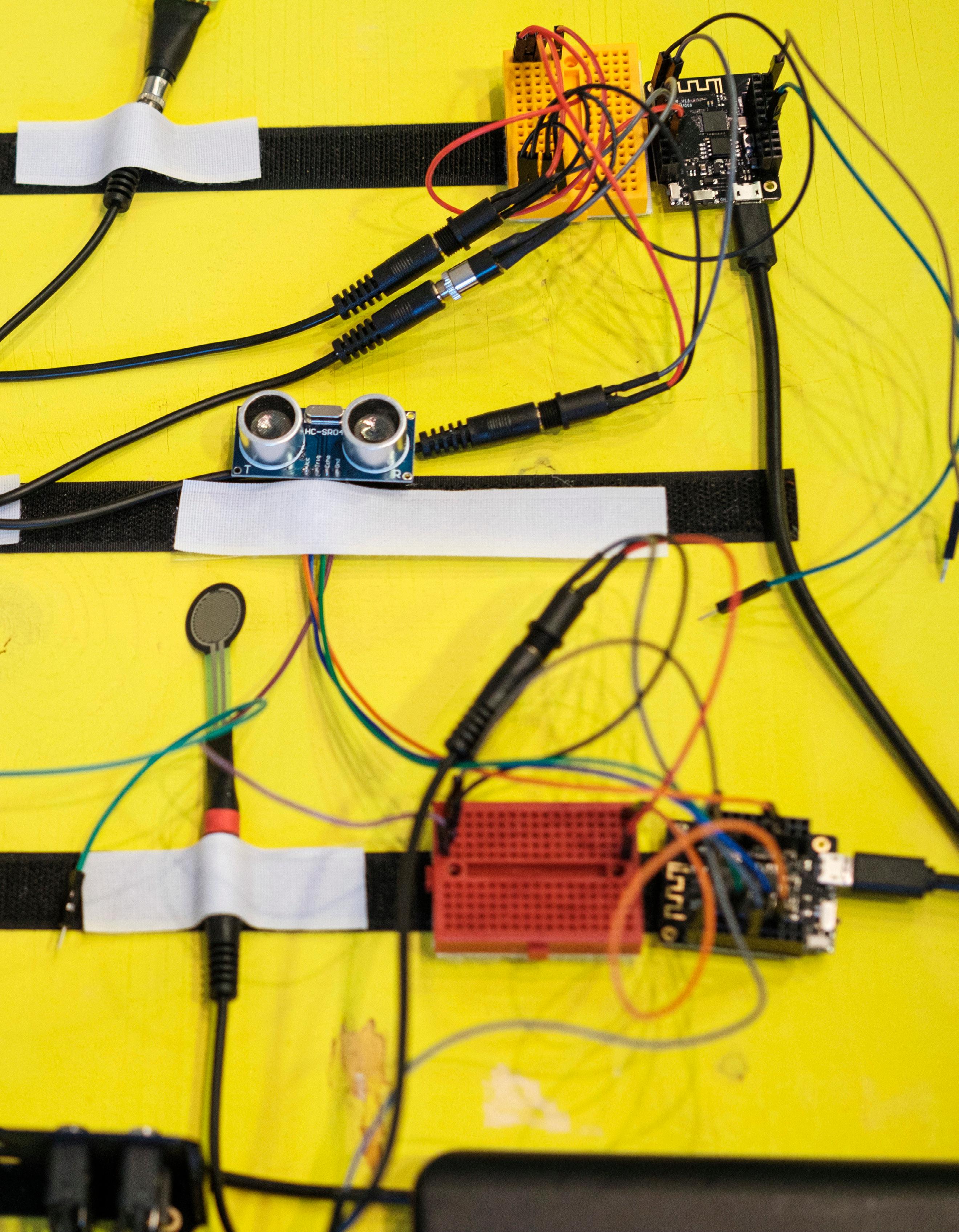

TECHNOLOGY

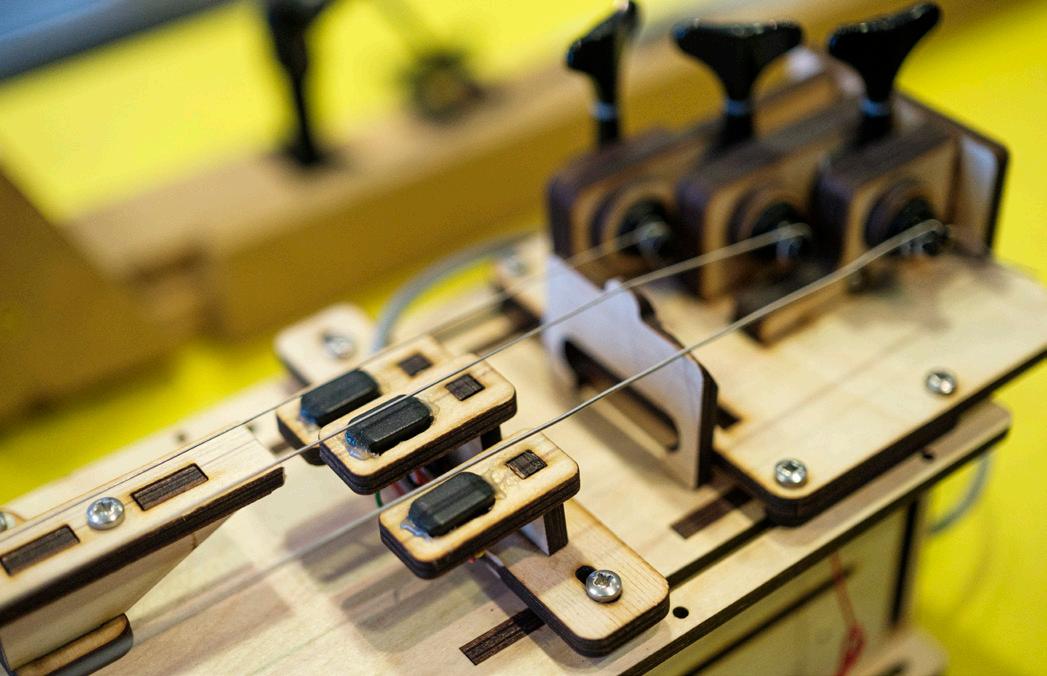

SOUNDING SMART 110

The Intelligent Instruments Lab is teaching us about music and AI.

ENVIRONMENT

FULL CIRCLE 66

The innovators who are making Iceland’s economy circular.

LITERATURE

PEDRO: IN PRIVATE 54

Author Pedro Gunnlaugur Garcia on making his innermost thoughts public.

CONTRIBUTORS

Editor

Gréta Sigríður Einarsdóttir

Cover photo

Golli

Publisher

Kjartan Þorbjörnsson

Design & production

Daníel Stefánsson

Writers

Erik Pomrenke

Frank Walter Sands

Halla Þórlaug Óskarsdóttir

Jelena Ćirić

Kjartan Þorbjörnsson

Ragnar Tómas Hallgrímsson

Zachary Jordan Melton

Photographers

Anton Brink

Golli

Eggert Jóhannesson

Mummi Lú

Rúnar Gunnarsson

Sigfús Eymundsson

Illustrator

Ásdís Hanna Guðnadóttir

Translator

Larissa Kyzer

Copy editing & proofreading

Jelena Ćirić

Erik Pomrenke

Ragnar Tómas Hallgrímsson

Zachary Jordan Melton

Subscriptions

subscriptions@icelandreview.com

Advertising sales sm@mdr.is

Print Kroonpress Ltd. 5041 0787 Kroonpress

NORDIC SWA N ECOLAB E L

Annual Subscription (worldwide) €72.

For more information, go to www.icelandreview.com/subscriptions

Head office MD Reykjavík, Laugavegur 3, 101 Reykjavík, Iceland, Tel.: (+354) 537-3900. www.icelandreview@icelandreview.com No articles in this magazine may be reproduced elsewhere, in whole or in part, without the permission of the publisher. Iceland Review (ISSN: 0019-1094) is published six times a year by MD Reykjavík in Iceland. Send address changes to Iceland Review, subscriptions@icelandreview.com .

Whether or not I like to talk about it, we’re seeing changes in the world that result from climate change. We and the generations that went before us got us into this mess, but we, and the generations that will come after us, are going to be the ones dealing with it. That doesn’t mean that the world is coming to an end. It just means that the world is going to look a lot different 50 years from now. And if you think about it, that was always going to be the case.

The good news is that this gives us what may be the best thing a person can have: a challenge. The human mind is at its best when it has a goal – a distinct problem which we can work to solve. Even if the problem seems insurmountable, there’s contentment to be found in chipping away at it, leaving it just a tiny bit smaller at the end of the day. One person working for one day is not going to secure our future in a changing world, but millions of people working for a lifetime just might.

In Iceland, we’re already seeing subtle changes to our ecosystem, and it’s starting to have a direct impact on our bottom line. Capelin roe, which can only be harvested for about three weeks each spring, is a valuable seafood product that brings Icelandic fisheries a good chunk of change. As the ocean around Iceland warms up, capelin swim further north, in search of polar-temperature seawater. As the development continues, we’re likely to see other small changes to our blue economy, and they add up quickly.

There are already people at work on finding creative and innovative ways to change the way we use natural resources. There are people working on finding the scientific data we need so we know where to direct our efforts. There are people making apps that make it easier for us to navigate a changing world, and people working on new sources of energy. There are also artists, musicians, filmmakers, and authors hard at work imagining a future we can come to terms with while opening up our eyes to what the world could be.

We’ve all got work to do. Let’s get to it.

The saga of the Efling Union negotiations finally concluded in early March. The powerful labour union had gone back and forth with SA, the Confederation of Icelandic Enterprise, for months trying to agree upon a new collective agreement. In February, SA threatened to lockout Efling union members, which in essence would have forced the 21,000 members out of work and out of a paycheck until the negotiations ended. On March 8, Efling members voted to accept a mediation proposal put forth by the state mediator, which gives members an 11% monthly wage increase.

Icelandic millionaire and the 2022 Icelandic Man of the Year Haraldur (Halli) Þorleifsson got entangled in an online exchange with his boss, controversial Twitter owner Elon Musk. Halli was one of the recent casualties of Musk’s layoffs at the popular social media app. Halli began working for Twitter in 2021 after his start-up company Uneo was purchased, but after being locked out of his accounts for over a week in March 2023 with no word from Twitter’s HR department, Halli assumed he had been fired. He tweeted his former boss, only for Musk to question Halli’s work and his disability (muscular dystrophy). After a backlash, Musk backtracked his comments and apologised to Halli. Some commenters have also pointed out that identifying Halli’s disability publicly violates American labour laws, raising suspicion that Musk’s apology was made primarily for legal reasons.

In early March, Justice Minister Jón Gunnarsson introduced a new plan to fight organised crime and sex offences in Iceland. However, the bill proposed by the minister would also give police unprecedented power to carry out surveillance. Sigurður Örn Hilmarsson, the chairman of the Icelandic Bar Association, stated that he is concerned that the proposed surveillance is quite general and can give the police authority to monitor people’s movements without themselves being under suspicion of criminal conduct. This comes on the heels of another controversial move to overhaul the police force. Earlier in 2023, Jón Gunnarsson authorised police to use electroshock weapons in Iceland without consulting Parliament.

Up until Iceland’s independence in 1944, Iceland was a colony of Denmark. In addition to being taught in primary and secondary school, Danish was also the gateway to many higher professions: studying at the university in Copenhagen was one of the most prestigious educations an upwardly-mobile Icelander in the 19th century could get. In fact, Copenhagen was in many ways the centre of Icelandic intellectual life up until the modern era. To this day, many Icelanders choose to attend university in another Nordic nation, such as Norway, Denmark, or Sweden. Because the Nordics are all

The Atlantic puffin (in Icelandic, lundi), is something of a national symbol, with many tourists and Icelanders alike flocking to bird cliffs to catch a glimpse of these brightly-coloured seabirds. If you’re planning your trip to Iceland around seeing these birds, then it helps to know when, exactly, they’re here!

Puffins spend much of their life at sea and are only in Iceland for a relatively short time to breed and nest. They tend to arrive in late April and generally begin to leave in August. The puffins are usually gone by September. The height of the breeding and nesting season is from June through early August.

Unlike many other cliff-dwelling seabirds, Atlantic puffins will actually dig little holes to build their nests in. Puffins are monogamous

good places to study and work, there remains an incentive today to develop a baseline proficiency with the language.

Written Danish and Norwegian are very similar, and a background in Danish can play a key role in communicating with other Scandinavians. Another reason Danish education has stayed in place in Iceland is that Iceland’s neighbours were historically, and continue to be, Danish colonies as well. Specifically, Danish is still taught in Greenland and the Faroe Islands, two territories that have strong historical and cultural ties to Iceland.

and mate for life, generally producing just one egg each breeding season. Male puffins tend to spend more time at home with the chicks, or pufflings, while female puffins tend to be more involved with feeding the chicks. Raising the pufflings takes around 40 days.

Until recently, it was actually unknown where, exactly, Atlantic puffins spent the rest of the year. But with modern tracking technologies, these little birds have been found to range as far south as the Mediterranean during the winter season. They don’t always head to warmer climates in the winter, however. Icelandic puffins have been found to winter in Newfoundland, Canada, and in the open sea south of Greenland.

FNJÓSKÁ NOLLUR

A loft apartment with incredible views of the fjord.

1 bedroom, 1 bathroom, sleeps 2 (4)

VALLHOLT GRENIVIK

A spacious, luxurious house at the shore.

3 bedrooms, 2 bathrooms, sleeps 6

HRAFNABJÖRG AKUREYRI

A very well situated, exclusive villa opposite Akureyri.

3 bedrooms, 3 bathrooms, sleeps 6

SÚLUR NOLLUR

A wonderful holiday house with an elegant interior.

1 bedroom, 1 bathroom, sleeps 4

LEIFSSTADIR AKUREYRI

Exclusive villa in the vicinity of Akureyri.

4 bedrooms, 2 bathrooms, sleeps 8

KRÝSUVÍK NOLLUR

A convenient loft apartment on the Nollur farm in Eyjafjörður.

2 bedrooms, 1 bathroom, sleeps 4

and booking

This spring, the ferry Sæfari will be out of commission for maintenance, in drydock from at least March 20 until May 15. Sæfari services Grímsey, an island 40 km [25 mi] north of the mainland, bisected by the Arctic Circle. The 50-some residents of Grímsey are dependent on the ferry, not just for getting to and from the mainland, but also for their essential goods and services.

Normally, Grímsey is connected to the mainland both by the ferry, which leaves from Dalvík, and a Norlandair connection to Akureyri. Now for eight weeks, the residents of Grímsey will have to rely on the fishing vessel Þorleifur for the delivery of basic supplies, and any visits to the mainland will have to be done by air. A programme known as Loftbrú, or Air Bridge, does subsidise flights for Iceland’s most remote regions, but this programme only covers flights to and from Reykjavík. During the ferry repairs, flights to and from Grímsey will be increased from three weekly flights to four. These flights will likewise be subsidised, though the final amount of support is not determined at the time of writing.

In the recent report on Sæfari’s scheduled maintenance, it was also noted that the ferry had been in service longer than initially intended. Originally planned to service Grímsey for 10 years, Sæfari has already been in service for 15 years, with no clear plans for a replacement. As Akureyri Councillor Halla Björk Reynisdóttir stated: “The thing is that ferry routes are just like Route 1 [the main highway around Iceland] and we would of course not accept any community being cut off from the main transport artery.”

In total, six ferries are operated throughout Iceland, connecting its inhabited islands and most remote regions to the rest of the nation. These six ferries are something of a relic from the golden age of boat travel. Route 1 was only completed in 1974, when the last section along the South Coast between Vík and Höfn was constructed. Prior to its completion, travellers to Southeast Iceland had to drive all the way around the island, heading north via Akureyri. Or they could take a ferry.

Ferries have played a role in Icelandic transportation from the settlement of the island. Indeed, building and maintaining ferries was one way a powerful chieftain could both flaunt his wealth and foster good will in his district, while also bolstering trade. Several Icelandic sagas contain references to this phenomenon, and in a stateless society like Commonwealth Iceland, the ferry could be seen as a kind of early public transportation.

The first ferries powered by modern engines arrived in Iceland in the 1920s. In 1924, one Guðmundur Jónsson from Narfeyri bought an old boat, the first in a long line of Baldurs (the ferry which services Breiðafjörður bay), founding one of Iceland’s first and oldest travel companies. In those days, there were no fixed departure times; everything depended on sea conditions.

Today, the operational framework remains similar to the earliest days of ferry travel in Iceland: a patchwork of public and private. Some companies, such as Sæferðir ehf., are privately owned and operated. Herjólfur ohf., the operator that services the

Listasafn

National Gallery of Iceland

Fríkirkjuvegur 7 101 Reykjavík

Safnahúsið

The House of Collections

Hverfisgata 15 101 Reykjavík

Hús Ásgríms Jónssonar Home of an Artist

Bergstaðastræti 74 101 Reykjavík

Westman Islands, is, on the other hand, publicly owned. All ferries in Iceland, however, are overseen by The Icelandic Road and Coastal Administration. And, despite Iceland’s maritime history, ferries have fallen by the wayside in recent years, with many of the nation’s ferries in need of replacement.

Recent incidents

In March 2021, the ferry Baldur was stranded in Breiðafjörður bay for more than a day. Some 20 passengers, a crew of eight, and 80 tonnes of salmon spent the night being buffeted by sharp winds before the stranded ferry could be towed back to port.

Baldur travels between Stykkishólmur, on the north coast of the Snæfellsnes peninsula, and Brjánslækur in the Westfjords, making stops at Flatey island along the way. Because Klettsháls, an important road connecting the Barðaströnd region to the outside world, is often impassable, the ferry serves as a vital link for this area. Often referred to as “the bridge to the Westfjords,” Baldur also sails year-round, meaning that for much of the year, Baldur is the safest, most practical way for residents of the Westfjords to access the rest of Iceland.

And although Baldur was serviced after the March 2021 breakdown, it was not the last one. Since then, Baldur has broken down twice. Notably, unlike all of Baldur’s predecessors stretching back to 1955, the current Baldur is a single-engine ship, meaning that if its engine fails, it is totally without power: something that has become increasingly common for the 44-year-old ship. The municipalities of Stykkishólmsbær and Helgafellssveit lodged official complaints about the safety of the ferry, but Baldur continues to be in service.

Baldur, originally named Vågan, was constructed in Norway in 1979. After 35 years of service, it was sold to Iceland to take its place in the long line of Baldur ferries that have operated in Breiðafjörður since 1924. Following the 2021 breakdown, state broadcaster RÚV featured the ferry in Kveikur, their investigative journalism programme. Kveikur reporters found that even after repairs and maintenance, Baldur was quite simply not seaworthy. Among other issues, there were serious problems accessing life vests, basic safety equipment was found to not work, the engine room was left open to the public, and several doors were found to leak water. But despite the problems with Baldur, authorities insisted that the old ship was still seaworthy. In an interview, Bergþóra Þorkelsdóttir, director of The Icelandic Road and Coastal Administration, described Baldur as “an old, but safe, ship.”

Many of the safety issues on Baldur that Kveikur shed light on have since been rectified, but even at the time of its purchase by operator Sæferðir some 10 years ago, there were concerns. The ferry was originally rejected for registration due to safety reasons, and it was only after an appeal that the ferry entered service.

In June of 2019, a new ferry – bright white, green, and blue –docked in the Westman Islands. It had crossed the Atlantic from Poland, where it was made, to be officially christened Herjólfur IV by Prime Minister Katrín Jakobsdóttir. As it came to harbour, it met its predecessor, Herjólfur III. They sounded their horns in greeting. More than just a nautical nod of the head, this encounter was much more: a meeting of past and present.

Herjólfur IV is in fact the first electric ferry in Iceland. Equipped with extra diesel generators for longer journeys, it is capable of making the crossing to Landeyjahöfn on battery power alone. For longer journeys, such as when the weather forces Herjólfur to cross at Þorlákshöfn, the backup diesel generator helps it along the way.

In 2019, the UK Department for Business, Energy, and Industrial Strategy estimated that ferry travel averages 18g of CO2 per passenger per kilometre. For comparison, domestic flights averaged 254g of CO2 per passenger per kilometre, and singlepassenger cars averaged 171g. Although ferries’ efficiency will vary widely depending on their age and design, they stand out as a clear winner for environmentally friendly travel, even beating out some train systems. And, of course, these figures are for ferries that still operate on diesel and oil power. For primarily battery-powered ferries such as Herjólfur, the environmental impact is even smaller.

Ferries are, of course, a special-use case that will never reach the capacity of, say, a high-speed rail network. But Iceland’s ageing ferries should not be allowed to become a relic of the past. Iceland owes it to all of its communities, even the smallest and farthest flung, to connect them with reliable transportation and services. Further investment in ferries could make travel safer and more environmentally friendly for the entire nation.

And in our increasingly disenchanted lives, isn’t the occasional boat trip still an adventure?

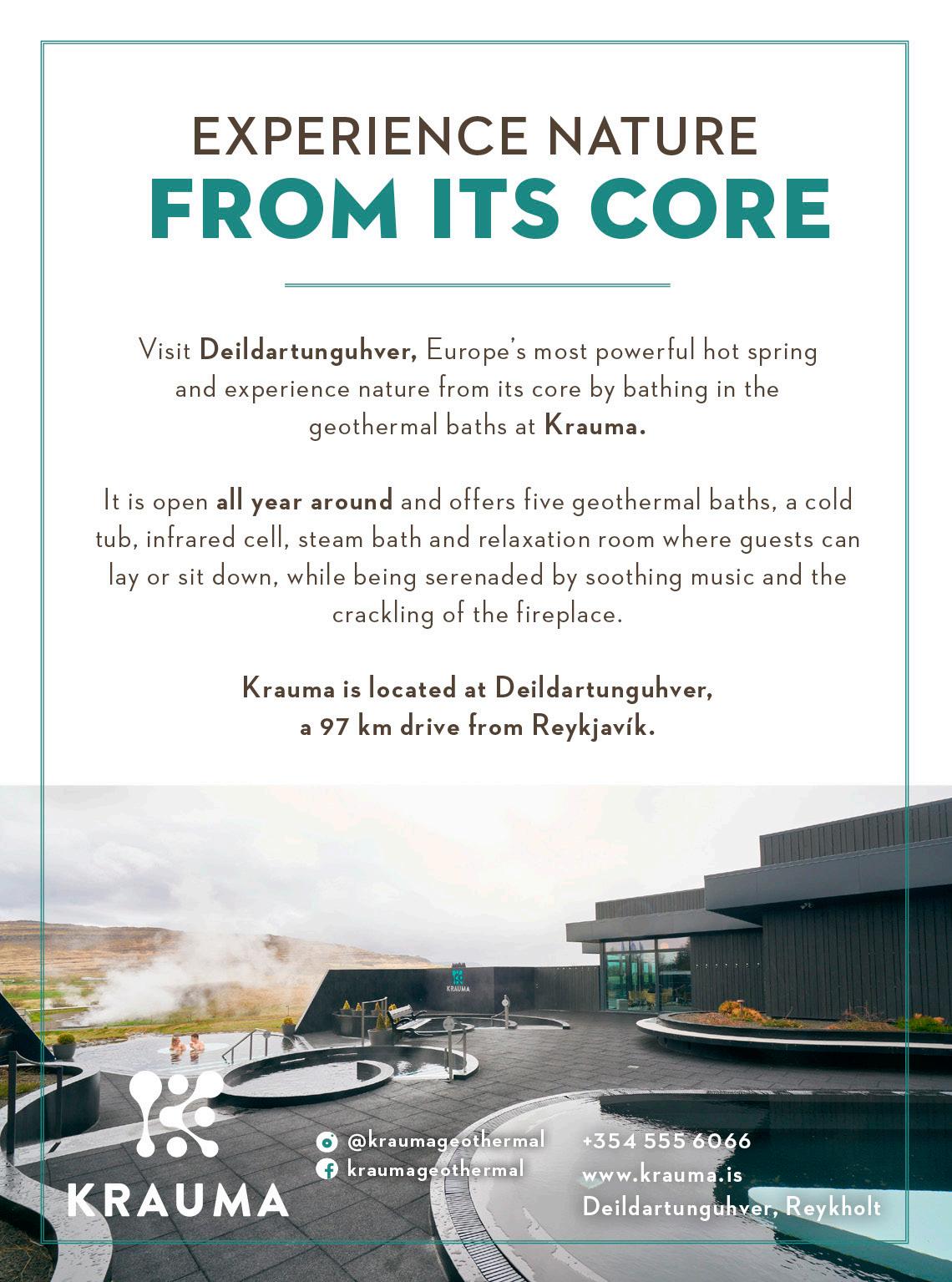

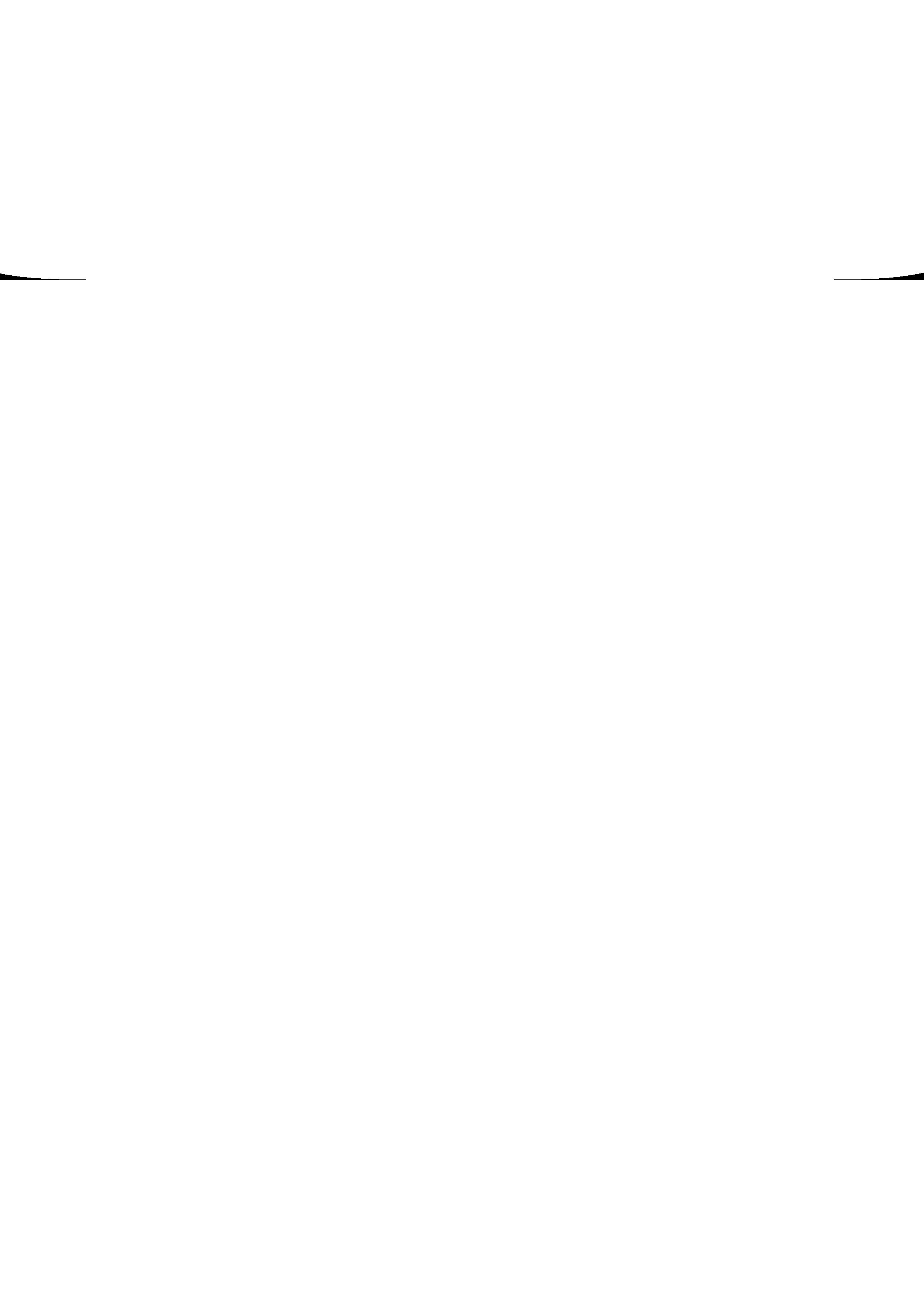

On March 3, the Icelandic Opera premiered its production of Madama Butterfly, authored by Italian composer Giacomo Puccini and first performed publicly in 1904.

The opera is set in Japan in the early 20th century and centres on the relationship between the US naval officer Pinkerton, portrayed by the Icelandic tenor Egill Árni Pálsson; and Cio-Cio-San, a 15-year-old Japanese girl, played by the Korean soprano Hye-Youn Lee.

Shortly after premiering, the Icelandic Opera’s production drew criticism for creative decisions in set design, costumes, and make-up.

Three days after the premiere, Laura Liu, a Chinese-American violinist for the Iceland Symphony Orchestra, published a post on Facebook accusing the production of yellowface (i.e. where a nonAsian performer uses makeup to imitate the appearance of an Asian character).

Liu shared pictures of the performers, who were shown wearing tinted makeup, painted-on eyebrows, and black wigs:

“Are we bringing yellowface back, Iceland?” Liu asked. “Furthermore, Madame Butterfly is Japanese. Those are Chinese characters. ‘All look same,’ right? It’s disturbing to have to repeat this: yellowing up is the same as blacking up. When you wear another race as your costume that’s called dehumanisation. Do better.”

Additionally, Liu also posted photos of the set design and

costumes, claiming that they weren’t representative of Japanese culture but rather a mish-mash of vaguely Asian aesthetics, including Chinese symbols.

Responding to Liu’s criticism online, Michiel Dijkema – the production’s Dutch stage director and set designer – argued that no attempts had been made to alter the skin colour or eye shape of the performers. Instead, elements from classical Japanese theatre traditions, including Noh and Kabuki, had been employed. These elements actually made the singers look “much whiter,” he wrote.

Dijkema asserted that he had consulted with friends and colleagues of Asian heritage regarding the use of these elements – and that none of them had deemed the choices racist As for the characters used on the set, Dijkema insisted that they were Japanese Kanji characters that were almost identical to Chinese characters. (Other commenters, including a few Japanese individuals, refuted these claims.)

On March 9, Steinunn Birna Ragnarsdóttir, Director of the Icelandic Opera, addressed accusations of racism and cultural appropriation in an interview with the radio programme Reykjavík Síðdegis.

Prior to the interview, Daniel Roh – a Korean-American stand-up comedian and teacher living in Iceland – had written an open letter

to the Icelandic Opera published on Vísir. In his letter, Roh stated that “performing yellowface” in such a large, state-funded production could lead to “real harm and alienation” given that racism was “real and present” in everyday Iceland. Daniel also announced that he would be staging a protest of Madama Butterfly on the following Saturday.

When asked what she made of such criticism, Steinunn reiterated some of the points made by her colleague Michiel Dijkema: “I was very clear about not using yellowface in this production,” she told her two interlocutors, adding that the producers had decided to take a “different route” to make the production believable (e.g. Kabuki makeup). Like Dijkema, Steinunn maintained that various experts, many of whom were of Asian heritage, had been consulted for the staging of Madama Butterfly, and had agreed that there was nothing racist about the production.

Lastly, Steinunn concluded by saying that she welcomed the discussion and that her team would keep an open mind to different perspectives – but that she did not foresee making any changes to the production: “Because these productions are copyrighted. It would be a very long process. We’d be in a pretty strange place if works of art were changed under these circumstances for these reasons.”

“It’s the nature of theatre; you can’t make everyone happy all the time,” Steinnun remarked.

The day after Steinunn spoke to Vísir, actor Arnar Dan Kristjánsson, a performer in Madama Butterfly, announced that he would not be wearing a wig or eye paint at the next performance of the opera:

“I was hired as an actor at the Icelandic Opera to work on the production of Madame Butterfly, which premiered last Saturday. I participated in cultural appropriation. I apologise,” Arnar wrote on Facebook.

Journalist Jakob Bjarnar lampooned the actor’s apology, stating that if he refused to wear his costume he should be booted, literally, from the production.

Guðmundur Arnlaugsson – a choir-member in the production of Madama Butterfly, and one of the individuals featured in the photo shared by Laura Liu – expressed profound regret for having inspired negative feelings among people. He noted, however, that some of the conclusions that people had drawn about the photo and the opera, and consequently about him and his friends, seemed “quite unfair.”

“All I can say is that my moustache is authentic, and I’m grateful that I wasn't asked to shave it off; the make-up applied, to me and others, was no different from makeup in other opera performances in which I’ve participated; and my eyes are simply not bigger than that – so what others think is intentional squinting is simply my natural look. The wig, however, is a disaster and the beard is dyed. But nothing else is out of the ordinary.”

On Saturday, March 11, demonstrators arrived at the Harpa Music and Conference Hall to protest the ongoing production . They were barred from protesting inside the building.

Speaking to the nightly news, Steinunn Birna told reporters that her team had decided to make “a few minor changes” to the production. “We had a good meeting yesterday with the performers, and the director, where we listened to their experiences,” she stated. “We decided that we would tone down the makeup slightly. Despite our conviction that we had not been guilty of yellowface, we decided to remove painted-on, slanted eyebrows and wigs, given that it will

not detract from the overall performance. In these decisions, I’ve stuck to two principles: one, that my people feel comfortable; and two, that we’re trying to make a good show even better.”

Steinunn added that she would be welcoming the protesters and inviting them to have a conversation: “I hope to have a constructive conversation. These are big questions. Where do the lines lie? Which races are you allowed to imitate – and are some races off limits? And these are questions that we can’t answer (we can’t step into their shoes).”

“We belong to this privileged race, and so I would like to have a constructive conversation.”

Photography by Golli & Eggert Jóhannesson

Words by Erik Pomrenke

Photography by Golli & Eggert Jóhannesson

Words by Erik Pomrenke

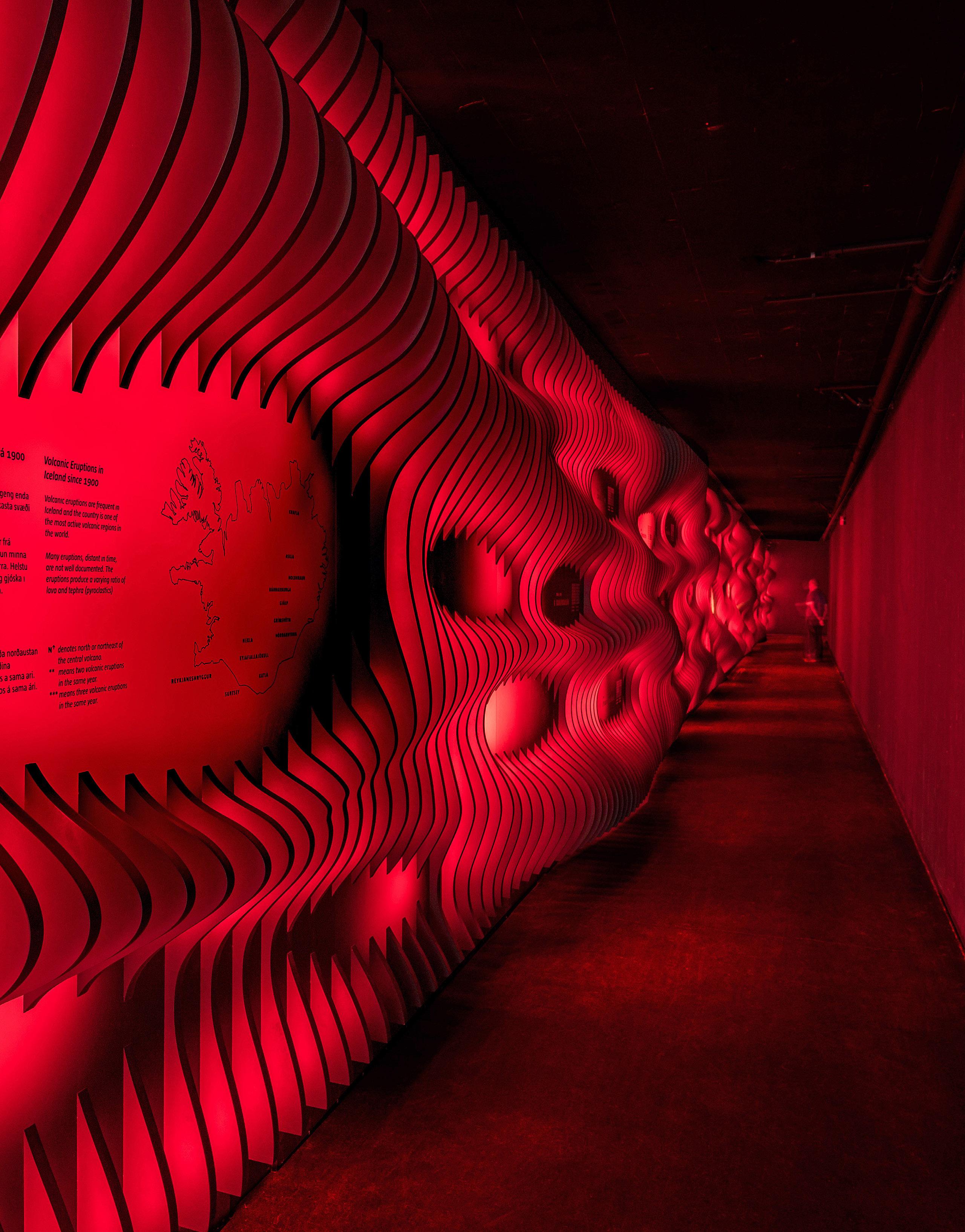

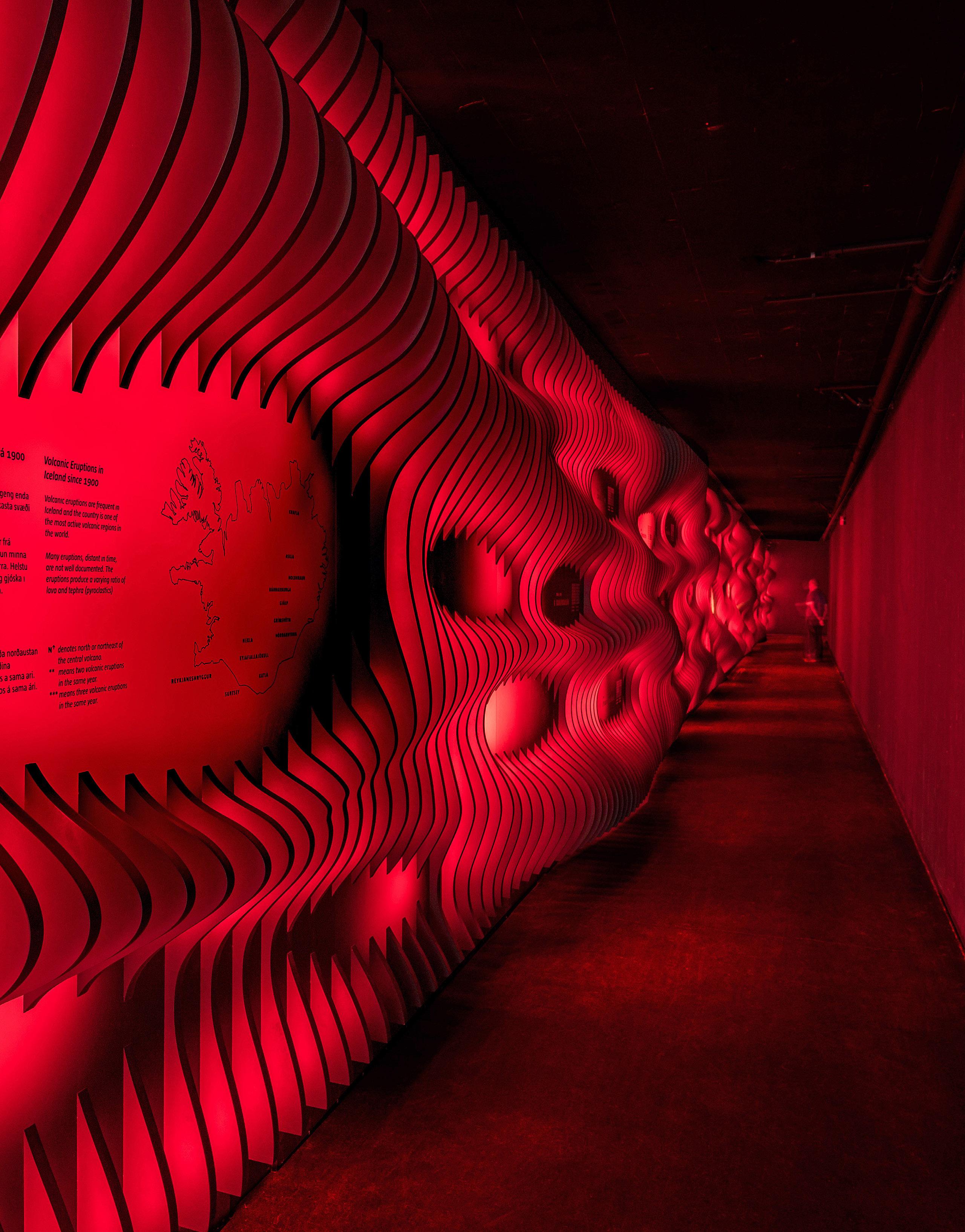

Visiting the exhibition Velvet Terrorism: Pussy Riot’s Russia, you enter a dark room. You are pleasantly greeted by a man sitting at a fold-up table spread with pamphlets and copies of Maria Alyokhina’s 2017 prison memoir, Riot Days. To your right: a video of a woman in a baggy, black dress fills one wall, blonde hair curling messily out from beneath a red balaclava. Standing above a portrait of President Vladimir Putin, she carefully lifts her dress and pisses all over him.

This is the first-ever museum exhibition of Pussy Riot’s work, and it’s being held at Reykjavík’s Marshall House. Maria Alyokhina has been through much to be here. When, on February 24, 2022 President Vladimir Putin announced the beginning of a “special military operation” in Ukraine, Maria, a founding member of Pussy Riot, watched the announcement from a detention centre on the outskirts of Moscow. Less than a year later, she and fellow members of the feminist punk band and activist group have created a visual omnibus of their political actions, a comprehensive critique of Putin’s Russia, in Reykjavík.

Pussy Riot is in theory a punk band, but their best-known works are acts of political protest and performance art. They first came to prominence in 2012, when they performed Punk Prayer, a frantic 60-second sonic protest at the altar of the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour in Moscow, in which Maria and her companions exhorted the Virgin Mary to become a feminist. Indeed, the exhibition’s title, Velvet Terrorism, comes from Patriarch Kirill of Moscow’s description of the protest. Several of the band’s members, including Maria (also known as Masha), served time in Siberian penal colonies for the performance. The charges: hooliganism and “religious hatred.”

“I was concerned that all of this visual material might die in the exhibit,” Masha tells me. “We didn’t want any frames on anything.” It’s never easy to incorporate the provocative, rebellious spirit of performance art into the sometimes-musty confines of art museums. In lieu of frames, glitter and brightly-coloured tape decorate the walls, evoking a teenage girl’s poster collage. Nothing here is permanent, the entire exhibition ready to be torn down about as quickly as it was put up.

Among the many images and videos of their diverse political actions, one stands out. Two women, Nadya Tolokonnikova and Maria Alyokhina, are dressed in blue and white sarafans, a traditional Russian women’s costume, accessorised with fishnet stockings and black boots. The scene resembles idyllic depictions of maypole dances, except the streamers are replaced with yellow plastic police tape and the two women are tying up a faceless, masked policeman. Nadya stares at the camera.

After politely pacing among many such images, visitors are finally challenged by a prison guard. To get through to the end of the exhibit, you must surrender your shoelaces, belts, phones, and keys and place them all in a grey, plastic tray. Your personal belongings disappear through a slot in the wall. It’s unclear where they’ve gone.

You are ushered into a small room, shuffling to not trip over your now-loose shoes. In front of you: a closed door. Above: an intercom, broadcasting in Russian. On either side: institutionally grey-green walls. It doesn’t help that the door is rather heavy and stiff. It takes some time to realise that freedom is only a quick, violent push away.

Hanging on the opposite side of the door is a

“RESISTANCE IS ALWAYS A CHOICE. AND THERE ARE ALWAYS NEW MOMENTS FOR RESISTANCE. IT’S NOT JUST IN THE PRISONS, IT’S IN EVERYDAY LIFE.”

bright-green uniform complete with an insulated backpack, the kind used by online food ordering and delivery services. This is the uniform that Masha used to escape from Russia in April 2022.

“We transported the uniform all the way from Moscow,” Masha says. “It took two months and got here just two weeks before the start of the exhibition. We never really know what’s going to happen to us, so it’s better for it to be here.” Police surveillance is a daily reality for her and her friends (you can always tell Kremlin agents from their bad taste in footwear, she says). And since 2021, Masha has been picked up by authorities for various trumped-up charges, including violating COVID-19 quarantine. For the past two years, she has been under intermittent house arrest, but the decision to flee only came when the authorities announced that she was to serve the rest of her sentence in a penal colony. Having once served out a sentence in Siberia, she had no desire to return.

“Sometimes we need to go out on an errand or whatever, so I came up with this idea to buy the uniform,” Masha explains. “The political police, you know, are quite stupid. The lower-level guys will be tasked with just monitoring you entering and exiting your home, and they often don’t notice much else.” With the help of the delivery uniform and Icelandic artist Ragnar Kjartansson, Masha was able to make it to the Belorussian border, and ultimately to Iceland via Lithuania. Ragnar’s exact involvement is left unstated, one of many cul-de-sacs in our conversation for the protection and anonymity of her friends.

Despite its dramatic nature, Masha is quite nonchalant about her disguised escape. “The most difficult thing,” she tells me, “is making the decision. Once you’ve made your decision, the rest is just practical.”

This decisiveness has defined Masha’s life from an early age. “I was quite a problematic child,” Masha says. This isn’t a surprise. “I changed schools a lot, I couldn’t get along with my teachers.

The way they teach in Russia, it’s still Soviet-era patriotism.” It was shortly after completing secondary school that Masha truly became politically conscious. And it wasn’t contact with dissident students in Moscow or radical reading groups – but the destruction of a beloved forest – that led to the leap of faith.

“I read that the state was going to clear Utrish Nature Reserve for an oligarch’s mansion,” she explains. Located on the Abrau peninsula along the Black Sea, only a narrow strait separates Utrish from Crimea. Which at that time was still Ukrainian. Utrish Nature Reserve is also the only part of Russia to have a Mediterranean climate: a little slice of paradise. “It’s a very unique place that should be protected,” Masha says. “I hitchhiked there after finishing school. At the time, I didn’t know anything about activism. I wrote to some organisations like Greenpeace and WWF and asked what I could do. And then I just picked up my backpack and went.”

She started to collect signatures to save the nature reserve from development, and when she returned to Moscow, she wrote again to Greenpeace and WWF asking what more she could do. From there, things started to snowball: she organised small demonstrations, filmed political actions, and collaborated with others. It was also during this time, as a student at Moscow State University, that Masha met Nadya. Together, they would become two of Pussy Riot’s founding members.

Masha’s problems with authority continued at university. “I was studying literature, and all of my professors were writers and poets. They knew what was going on, why were they not in the streets?” While some in the ivory tower agonise over the relationship between art and political commitment, for Pussy Riot’s project, the interconnectedness of the two is quite simply axiomatic. Art and activism at the same time.

For Masha, “punk isn’t a genre of music. It’s a way of life.” And this “way of life” isn’t merely an aesthetic identity. It has to do with

“I THINK THAT ART IS BASICALLY ASKING THE QUESTION: DO WE WANT TO LIVE LIKE THIS, OR NOT?”

asking the authorities difficult questions, being willing to come into real confrontation with the state. This is something that Masha is deeply familiar with, having spent a total of two years of her life in prison, and about the same amount of time under house arrest. “I think art has a responsibility to change the norm,” she explains. “So many things that are normal now, that we take for granted, are still very new. It was totally impossible to imagine gay pride within some people’s lifetimes. You could end up in a mental hospital. Some people had to sacrifice themselves to change the norm. I think that art is basically asking the question: Do we want to live like this, or not?”

Since those early days of activism, Masha and her companions have toured and lectured throughout the world, led major demonstrations, and, of course, made themselves enemy number one in Putin’s Russia.

A common motif in Pussy Riot’s visual vocabulary is the moment of arrest. This moment, the frequent conclusion to many of their actions, could be seen as an integral part of the performance, the standing ovation to a virtuoso protest.

In one such image, from a demonstration of the 2014 Sochi Olympics, Cossacks in fur-lined ushankas lash Masha and her companions with heavy horse whips. There is a curious detachment, as if neither party particularly wants to be here. The action takes place in the passive voice; there is whipping being done. Masha and her

friends stand there stoically disassociated from the blows, while the Cossacks, halfbored, wait for 5:00 PM to roll around, like the rest of us. In other images, Masha’s face is illuminated by a saintly calm. Looking at the camera as hulking, armed guards take her away, she resembles nothing so much as the Pietà.

“Of course, it’s stupid to resist these large men with guns,” Masha says. The saintly appearance is, in a very practical sense, a signal to these violent men that she’s no longer resisting. But her calm passivity in these images also casts absurdity on the proceedings, men in special forces gear surrounding the diminutive Masha. “Even these men are just working a job,” Masha says. “There are definitely some true sadists who enjoy the full extent of their power, but they’re not the majority. The majority are tired. They want to go home to their wife and kids. And just like everyone else, they’re not being paid enough for what they do.” In some of these images, however, the attentive viewer might catch something else: the shadow of a smile. “Arrests,” after all, “can be fun.”

And Masha’s defiance extends well beyond the moment of her arrest. “The penal colonies [often referred to as ‘the zone’], are still the same as in the Soviet Union,” Masha says. Prisoners live on strictly regimented schedules, sewing military uniforms for slave wages. During her time in the penal colony, where she was subjected to a total of five months of solitary confinement, Masha maintained contact with human rights observers. Through learning her rights

and hunger striking, she even successfully mounted a campaign to reform conditions from the inside. “I started to defend myself,” Masha remembers. “I asked for a copy of the prison regulations. Many don’t know this, but they have to give you the regulations if you ask for them. I started to read the regulations and I found out it was them breaking the law, not me.”

But it wasn’t easy. During all of this, guards would sometimes break script, asking her why she didn’t make life easy for herself. Why she always had to take the hard way. But, as Masha tells me: “Resistance is always a choice. And there are always new moments for resistance. It’s not just in the prisons, it’s in everyday life. I knew that if I submitted in prison, even when I regained my freedom, I wouldn’t be free.”

Over the last year, pedestrians in downtown Reykjavík may have noticed some new graffiti in several locations. Over a field of blue, an arrow points east. War: 3,963 km. Beside the arrow, a black bomb crashes through a house.

An island on the edge of the Arctic Circle, Iceland has always been on the periphery of world history. But it is Iceland’s marginality that has often thrust it into the centre of things as well. Its MidAtlantic disposition made it an important shipping lane during the Second World War. It was likewise considered a sufficiently central, yet neutral, location for the famous nuclear disarmament talks between Reagan and Gorbachev in 1986. Iceland’s peculiar position has also made it home to high-profile asylum seekers and political refugees over the years, most famously the controversial chess grandmaster Bobby Fischer, who called Iceland his home from 2005 until his death in 2008.

It makes sense, then, that Pussy Riot’s first-ever exhibition took place at the Marshall House. The house, built in the post-war years of development under the Marshall Plan, was originally a fishmeal factory. The Marshall Plan’s goal was to develop post-war Europe, especially Germany, to keep it within the American sphere of influence. Today, the Marshall House is home to Kling og Bang, i8 Gallery, and several other spaces for contemporary art. Iceland, so far away from it all at first glance, is not so insular after all. “War,” Masha says, “is always closer than it looks.”

“WAR IS ALWAYS CLOSER THAN IT LOOKS.”

Words by Ragnar Tómas Hallgrímsson

Photography by Golli

Words by Ragnar Tómas Hallgrímsson

Photography by Golli

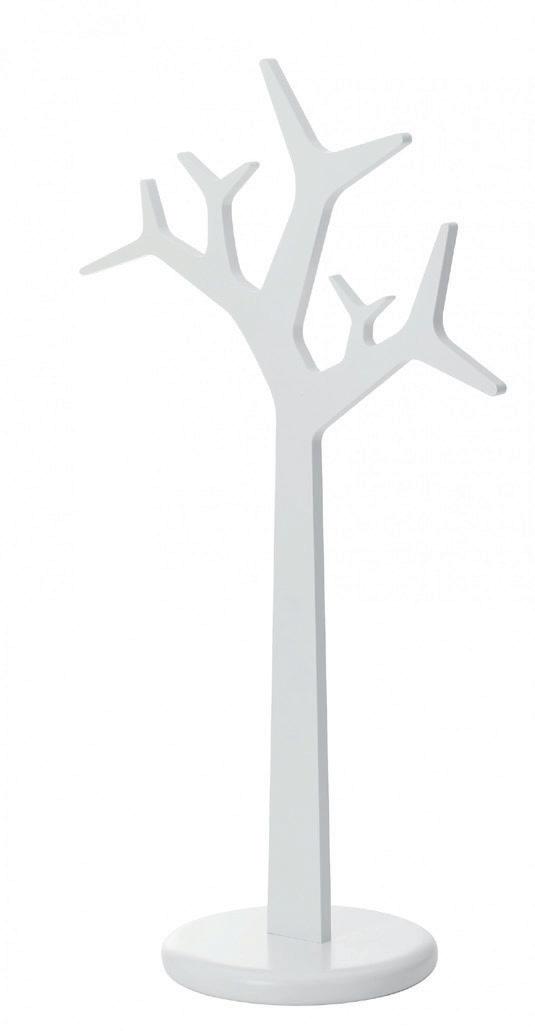

Gísli Einarsson must rank as one of Iceland’s most prolific television producers. When afforded the opportunity of stepping behind the camera and training his lens upon the world, Gísli’s audience saw the world not as it was – but as Gísli was: it took a true rustic, proud of his provincial manners and heritage, to make it to the national broadcaster in Reykjavík and focus our collective attention on the people of rural Iceland. This most domestically-travelled man in Iceland (such is his reputation) has now produced over 500 episodes for his TV series Landinn (e. The Local), and he’s recently staged a show on the subject of his own travels. This makes him, in the eyes of Iceland Review, the ideal interlocutor.

“WE DO NOT SEE THE WORLD AS IT IS, BUT AS WE ARE.” – ANAÏS NIN

“A little weird”

When we find Gísli Einarsson, he’s stepping out of his office in the corner of the high school building in Borgarnes, West Iceland. He works for the National Broadcaster, which is another way of saying that he must secure his livelihood by other means.

Among his current sidelines is a two-hour stand-up-cumstage-show, billed as an update to the famous Eggert and Bjarni’s Travels in Iceland, a book that was funded by the Danish crown and published in the late 18th century. (The title of the show is Gísli Einarsson’s Travels in Iceland – and Not Eggert and Bjarni’s.)

We’re in town to see it.

Gísli is red-bearded and bald, a slight hunch in his back, and wearing a nice, new-looking, white turtleneck sweater; he’s long since reconciled himself with his ungainly appearance and embraces his reputation for being “a little weird.”

When asked what exactly he means by this phrase, he retorts: “I look weird,” intoning his answer with the kind of good-natured self-deprecation that is, in his estimation, the key to good humour; if you’re going to take potshots with a funny gun – you best be prepared to spare a few rounds on yourself.

Gísli comes across as personable but slightly less jovial, at first, than I’d expected. (He’s always so upbeat on television and I worry he doesn’t like me.) As we stand there and shoot the shit, he regularly crosses his legs, as if he’s a schoolboy on the verge of self-urination. It’s an awkward stance, assumed to keep his blood pressure from plummeting, for he’s recently been diagnosed with PAF (Pure Autonomic Failure). “It’s a one-in-a-million diagnosis,” he observes, “and I’m often the one-in-a-million person to get that kind of thing.”

He’s got a point.

Gísli was born with a rather potent pollen allergy, the most impractical kind of pathology to have when growing up in the countryside. (He was useless during hay season.) City boys, he notes, were often sent to farms in the summer to toughen them up whereas he – runny nose and red eyes – was commonly evacuated from Borgarnes into the city. The loneliest four months of his life were suffered in Reykjavík.

Gísli doesn’t like talking about his illness, although openness has served to preempt any suspicious looks directed towards his pretzeled posture. It also, I imagine, helps to keep people on their toes in case he faints.

We ask him to pose in front of a big, picturesque window, right next to his office, which is like some sort of animated painting: framing the winding Borgarnes bridge, the stately Hafnarfjall mountain, and all the slow-moving rural phenomena dawdling through the snow-sprinkled landscape.

When asked if it’d be possible to turn off the lights, Gísli goes jogging down the hall. Why he’s jogging, I’m not sure, but I’ve heard stories of him passing out prior to gigs – he often MCs Þorrablót, traditional Icelandic winter celebrations featuring þorramatur (traditional Icelandic food) – and I worry that he’ll faint again.

Unfortunately for the content of this article, he doesn’t.

To capture Gísli in his native environment, we suggest that he strike additional poses in front of a few Icelandic turf houses located above the school building and visible through the grand window. The houses, we learn, are adjacent to a private property, and as Gísli models on a rock in the yard, the woman residing on said property, wearing a black tank top, voyeuristically snaps pictures of our subject through her window.

Quid-pro-quo.

We ask Gísli to show us around his hometown, someplace special , and he proposes Einkunnir: a hiking area just outside of town that is also popular among riders. As he drives, Gísli reveals that he was raised in one of the few horse-free farmsteads in Borgarnes.

“My grandfather’s brother was an avid rider and a heavy drinker, a dubious combination that led to his untimely death some decades back,” he says.

Gísli, too, has had his share of bad luck with the animals. When

he was 11, he leapt atop a wild horse during a roundup, fell off – and broke his collarbone. He’s a notorious klutz.

“Last fall,” Gísli begins, “I decided to paint the eaves and windows of a roundup hut.” Gísli clambered atop the hut, but the ladder was perfunctorily whisked away by the wind. Deprived of cell phone service, he realised that he’d have to jump down. He landed awkwardly and broke three bones in his instep. The hut, operated by the Travel Association of Borgarfjörður [which he helped to found two years ago], is only about the size of a Montenegrin basketball player.

At Einkunnir, Gísli leads us towards a scenic grove via a snowstrewn trail. We come across three riders, and one of them, a man by the name of Björgólfur Björnsson – who boasts an impressive beard and a fair face, like an ageing Viking – says hello.

“I wanted to thank you,” he says to Gísli. “I thought that your show was excellent. I don’t often laugh out loud, but I managed it once or twice this time.”

Gísli thanks the man sincerely, obviously flattered by his success in inspiring audible mirth from the stolid old timer, before striking up a conversation with the rest of the party. Taking note of one of the men’s bare heads, Gísli offers him his Tottenham Hotspurs cap.

“I’d rather die,” the man replies.

On our drive back to town, Gísli expands upon his enthusiasm for English football. He points to a roadside sign with which he and a friend took some liberties: “Tottenham Hotspur, League Champions 2022-2023.” It’s an optimistic divination, to say the least, for Spurs, who often display streaks of brilliance, have bungled every attempt at the league championship in their less-than-glorious career. (They currently sit fourth.)

“And you received permission for this, I suppose?”

“Nope, we just did it,” Gísli replies matter-of-factly. “Granted, the person who owns the sign wasn’t all that enthused – and the Liverpool fans, especially, have been rather upset about it. Which I’ve enjoyed.”

Back in Borgarnes, Gísli escorts us into Kaffi Kyrrð, a café whose interior is bloated with furniture: antique sofas, strange paintings, random knick-knacks – and New-Agey music flowing gently from the speakers. It feels like an apt metaphor for modern life: There’s way too much stuff going on – and everyone’s pretending to practise mindfulness.

Gísli asks the proprietors, an elderly couple who give us a warm welcome, whether they’re planning on attending tonight’s show. They say that they’ve yet to secure tickets but that they’re “definitely interested.” To my ears, this seems like the kind of thing that you say when you’re trying to be nice, but country folk, I later deduce, must be less duplicitous than their metropolitan counterparts. But that kind of deduction is mere urban bias.

We order coffee, and I inquire about Gísli’s favourite places in Iceland. He fires off a list of personal preferences (only a few of which I’m familiar with): the Hraunfossar waterfalls, Húsafell, the Kaldidalur valley, and on and on and on.

“My experience with foreign travellers,” Gísli remarks, “is that they’re often taken by things that we Icelanders don’t find all that special. They’ve opened our eyes to the black sand beach at Reynisfjara. I wouldn’t take tourists to the Gullfoss waterfall or Geysir; I’d show them the Snæfellsnes peninsula or other lessvisited gems.”

Gísli’s quite enamoured with old moss-covered lava fields (like Mother Nature laying down a saxony carpet on particularly rough flooring), and as a student of history, he often takes special note of human artefacts. Cairns. Old roundup pens. Etc. But anyone who’s spent any time with Gísli will soon begin to suspect that it’s the people that compelled him to circumnavigate our humble island so many times over, is the people He lights up around them like some kind of motion-detecting security light, but as opposed to hostile wariness – Gísli exudes a welcoming and engaging beam of rapt attention.

His greatest pride over the course of his career is having shone a light on Iceland’s country folk. His production of Landinn has yielded over 500 episodes.

That’s Simpsons territory.

“I’m proud of having raised interest in rural Iceland,” Gísli observes. “I love reporting on passionate people doing interesting things – and, in turn, inspiring others to pursue their passions. I also love meeting kids and foreign residents who watch our programme to learn about Iceland. TV shows don’t make miracles, but they can have these small effects.”

“How would you describe Icelanders?” I inquire, curious if there are any far-fetched generalisations to be made about my kind.

“I don’t know,” he responds. “It’s these clichés; maybe it’s a bit difficult getting to know us. And we have this slight inferiority complex, too. I sometimes say that our problem, our defining quality, is that we’re rural folk trying to be cosmopolitan. We’re trying to shake off this stigma of being a small nation instead of embracing it. We’re competing with bigger countries on the wrong basis.”

I entertain a favourite theory of mine, most strongly evidenced by our fumbling overreach during the years leading to the financial crisis, namely that we’re “a nation of amateurs.”

“There certainly isn’t the same room for specialisation,” Gísli replies, “especially in rural areas, so we’ve needed to become quite versatile. People do their jobs while also volunteering for the search and rescue units or the fire brigade. But our smallness is our strength. Take me, for example: I manage to climb the media ladder, despite coming from a small town and boasting only a high school diploma.”

The subtext being: “If I can make it, anyone can,” although Gísli is probably selling himself a little short.

“The best thing about this job,” he continues, “is that you’re

afforded different perspectives. Travelling the country as a tourist, you often have rather superficial encounters. But as a journalist, you can dig a bit deeper.”

“What have you learned?”

“Just how great people are,” Gísli declares. “I love meeting people who can speak passionately about their pursuits, which I often have very little interest in to begin with – but which end up completely fascinating me. I also love discovering things that I didn’t know existed. There are still things that surprise me, even after so many trips around the country.”

“And I imagine that you’ve become less prejudicial?”

“Yes, me, of all people, with all my strangeness, should not be judging anyone. I celebrate diversity. And that’s changing in Iceland. We’re becoming a more diverse society. And we’re a tolerant people. I’m tolerant, too – maybe not regarding certain football clubs, but that’s neither here nor there.”

As previously noted, the premise for Gísli’s show is Eggert and Bjarni’s Travels in Iceland, an 18th-century text which was intended as a kind of scientific investigation of Iceland and its inhabitants. Although the book is ambitious and well-researched, Gísli maintains that some of the authors’ descriptions of Icelanders in different parts of the country are both brutally blunt and slightly dicey.

“Just like the book, we wanted to play on this idea that Icelanders differ from region to region,” Gísli explains. “By modern standards, however, Eggert and Bjarni took quite the liberty in their characterisations, so much so that, at times – it borders on hate

speech! The South Icelanders are described as ‘dirty losers and obnoxious degenerates.’ It’s quite hilarious, to tell you the truth, and it often smacks of academic snobbery.”

In his show, which is performed at the Settlement Centre in Borgarnes, Gísli cherry-picks excerpts from the book and pretends that he’s performing an update.

“But first and foremost, it’s a conceit to open the door to cheap humour,” Gísli admits. “Eggert and Bjarni’s work is slightly more elegant than my ‘update,’ and to this day the book still stands as an important scientific document – as a useful source when it comes to Icelandic cooking and farming, for example. I’m not sure how to categorise my show; it straddles the bounds of stand-up and theatre.”

“And do the authors’ observations rhyme with your own experience of Icelanders?”

“I wouldn’t say so – but there are things that seem apt. People from Þingeyjarsveit, for example, are proud of how proud they are. The people of Skagafjörður are party animals. But a lot has changed since Eggert and Bjarni travelled the country. People have become more intermixed.”

That same evening at the Settlement Centre, at about 7:30 PM, Gísli slips into a cramped side room near the entrance and insinuates

himself into his costume. He puts on a white, puffy shirt (the kind made famous in the fifth season of Seinfeld ); a grey vest; grey trousers; and knee-high socks, which he pulls all the way up to his blue boxers, directly below his paunch. He then proceeds to tie a buckle over his dress shoes.

Once Gísli is dressed, his daughter applies makeup, daubing some matte substance on his head to keep his cranium from blinding the guests.

“Are you the miracle worker who makes him look presentable?” my colleague inquires of Gísli’s daughter.

“I wouldn’t say good – but definitely better,” she responds. Moved by this exchange, Gísli recalls being absolutely roasted for wearing capri pants and high socks on television. His daughter butts in.

“I think it was mostly the socks,” she says, in that charmingly embarrassed tone that children so often adopt around their parents. “We have ankle socks now, you know?”

“Yeah – but they do nothing for me,” Gísli replies, unfazed. Just before 8:00 PM, a crowd of almost 100 people are gathered in the loft of the Settlement Centre, seated in two rows on either side of the roof. It’s mostly senior citizens, but there are also a handful of people situated, probabilistically speaking, further from the grave.

There’s a glass box in the middle of the stage, containing

I’m tolerant, too – maybe not regarding certain football clubs, but that’s neither here nor there.”

“We’re losers, narcissistic louts, but it’s important to note that we’re not all the same. We’re a diverse group of losers.”

the original manuscript for Eggert and Bjarni’s Travels in Iceland, or so the audience is led to presume When the lights go off, the refined voice of an elderly woman addresses the audience over the speaker:

“In 1752, the scientists Eggert Ólafsson, a naturalist, and Bjarni Pálsson, a doctor, received a subsidy from the Danish crown to document the living situation of the Icelanders for the purposes of proposing improvements. The conclusion of their research was introduced in the book Eggert and Bjarni’s Travels in Iceland, which was published first in Danish in 1772. It wasn’t translated into Icelandic until 1943, and there’s no denying that the book is one of the most distinguished publications about Iceland that has ever been written.

Once the woman stops talking, the door to the loft flies open –and Gísli Einarsson walks in, to rapturous applause.

“The thing is,” he begins, “Eggert and Bjarni were only here for about five years. And not even five years – five summers! They were no different than your average high-season tourists! I, however, have conducted my investigation for 25 years straight. I’ve crisscrossed the country, back and forth – and back again. I’ve mixed with the people, I’ve mixed drinks – but I haven’t received a penny from the Danish crown. Not a single penny!”

He pauses.

“But the biggest difference between Eggert and Bjarni and me, aside from the fact that there were two of them and only one of me – which is two times the difference – is that they published their findings in Danish. And here we are complaining about immigrants not speaking Icelandic! Come on.”

“It’s right to point out that by publishing in Danish,” the old woman interjects over the loudspeaker, “Eggert and Bjarni reached a much larger audience. At the time, Icelandic was only spoken by a negligible number of souls – and read by even fewer.”

The crowd laughs, and Gísli, to spite the old woman, switches to Danish. He clears his throat – and launches into a passionate and guttural spiel. And then he stops short.

“You just can’t do this to other people,” he says. “It’s physically impossible to speak Danish for two hours straight. If I were to try –I’d have to have my tonsils removed during the intermission.”

When the laughter dies down, Gísli continues his commentary on Eggert and Bjarni’s work.

“A lot has changed since they were here. To understand who we are, we need to understand where we came from. It’s been claimed that Iceland’s first settlers were Vikings – but that’s not true. They were just some random people. In 874, Haraldur Fairhair sent his subjects a letter notifying them of tax hikes and interest rate hikes and so all the literate people fled the country. They were forced to return 300 years later – for someone had to write the history of the Scandinavian kings.”

Gísli says many humorous things over the course of the evening, and as he riffs on the Icelanders’ quirks, one is tempted to generalise, halfway through the show, that one of the lessons from all of Gísli’s travels is that whatever regional eccentricities the Icelanders had evolved by the middle of the 18th century have mostly been phased out in modern times; extrapolating on that trend, one might be tempted to surmise that whatever idiosyncrasies differentiate the Icelanders from the rest of mankind today, will likewise be phased out over the coming decades; our differences belie our similarities – and history always rhymes. “We are, in reality, refugees,” Gísli declares. “We’re genetic refugees – who flee so often that unpacking our bags is barely worth the effort. We’re losers, narcissistic louts, but it’s important to note that we’re not all the same. We’re a diverse group of losers. We’re all kinds of wimps.”

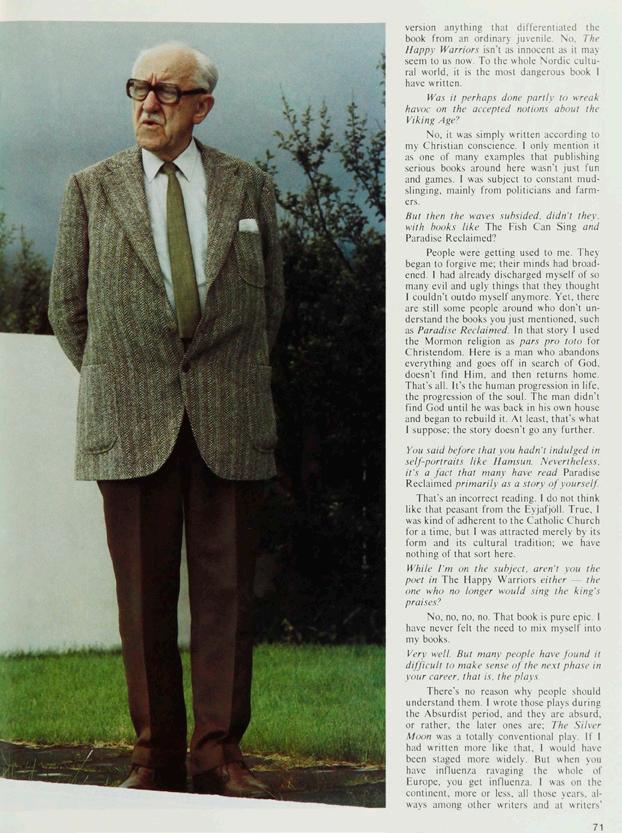

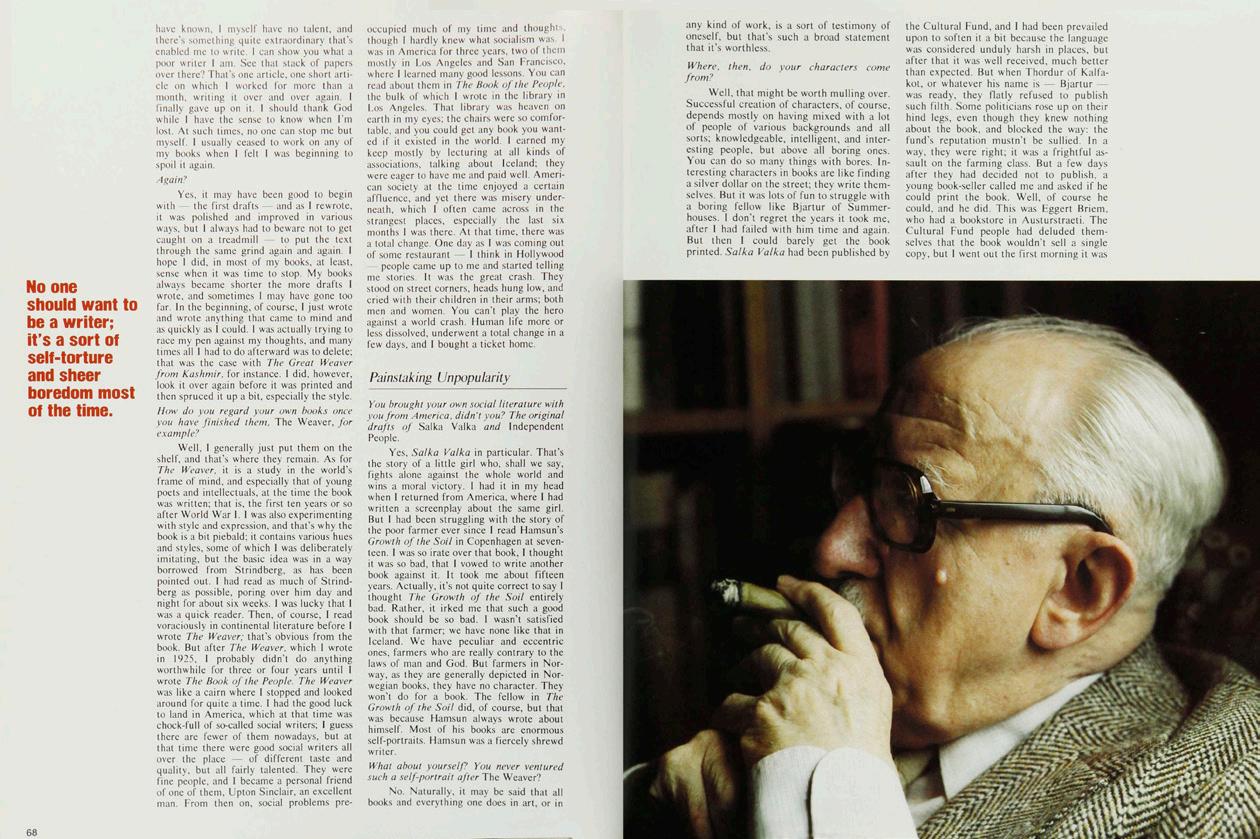

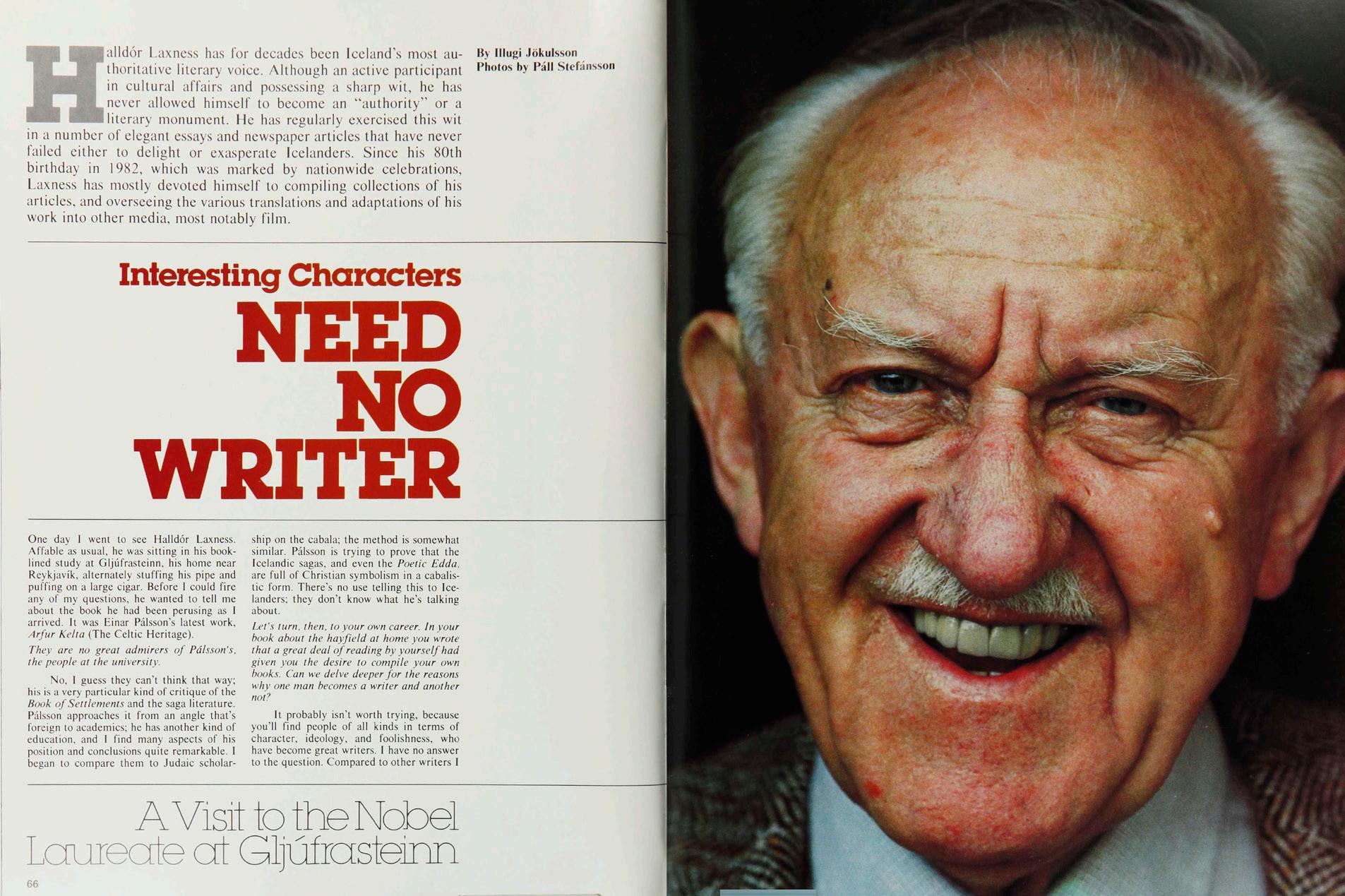

This year, Iceland Review celebrates its 60th anniversary. To commemorate the occasion, we’ve dug deep in our archives to bring you some highlights of Iceland’s history, through the eyes of contemporary journalists and photographers.

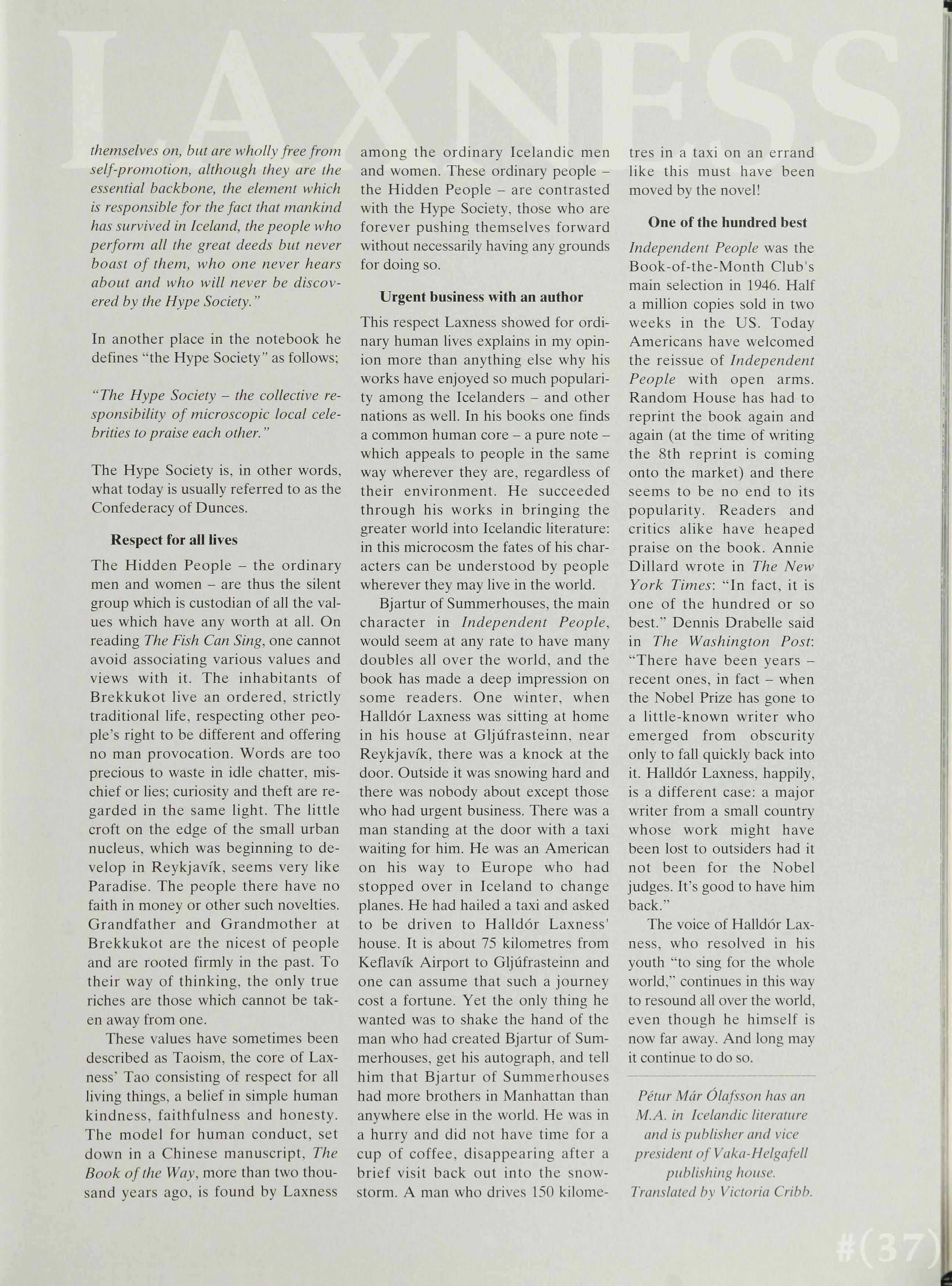

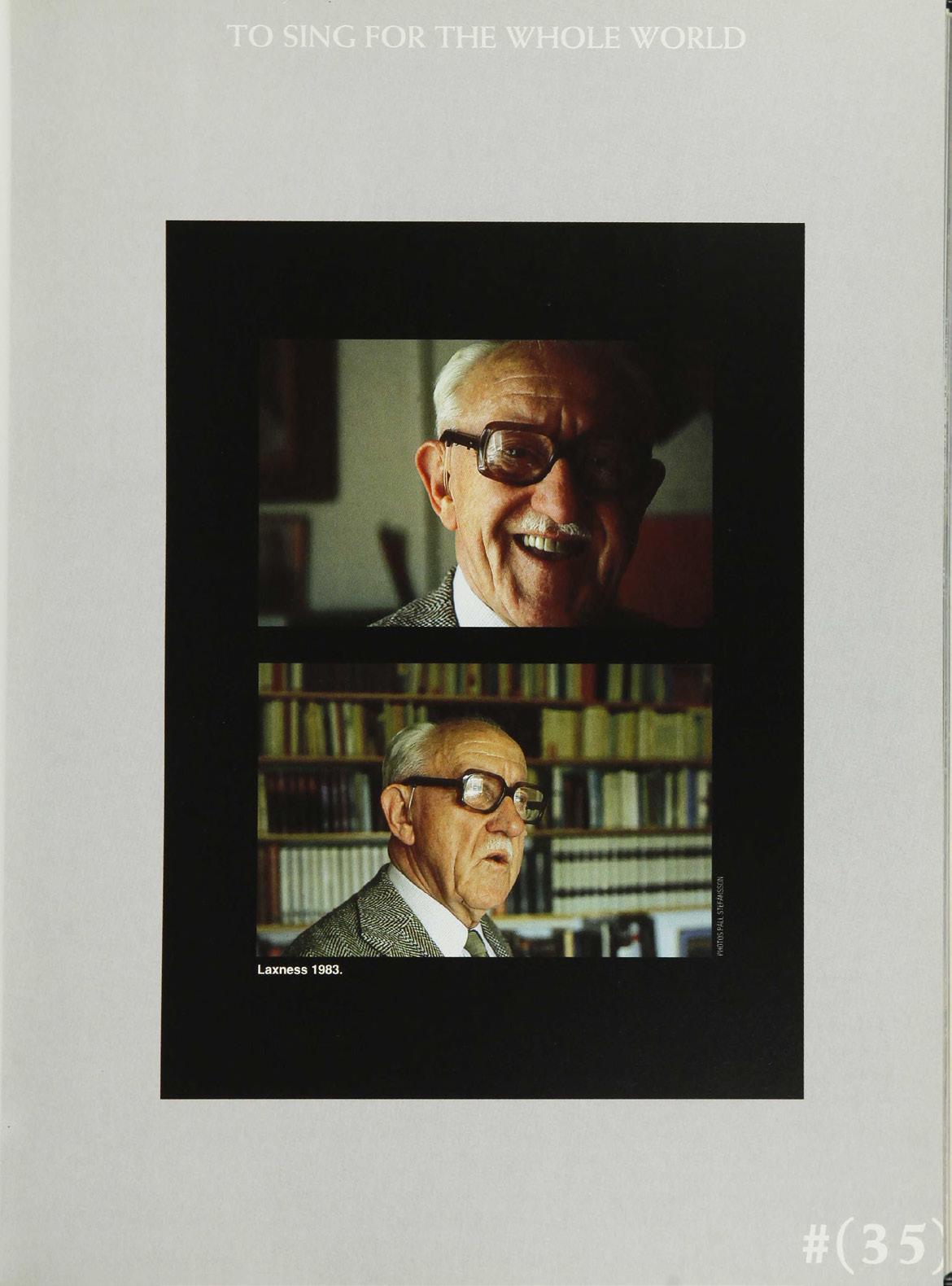

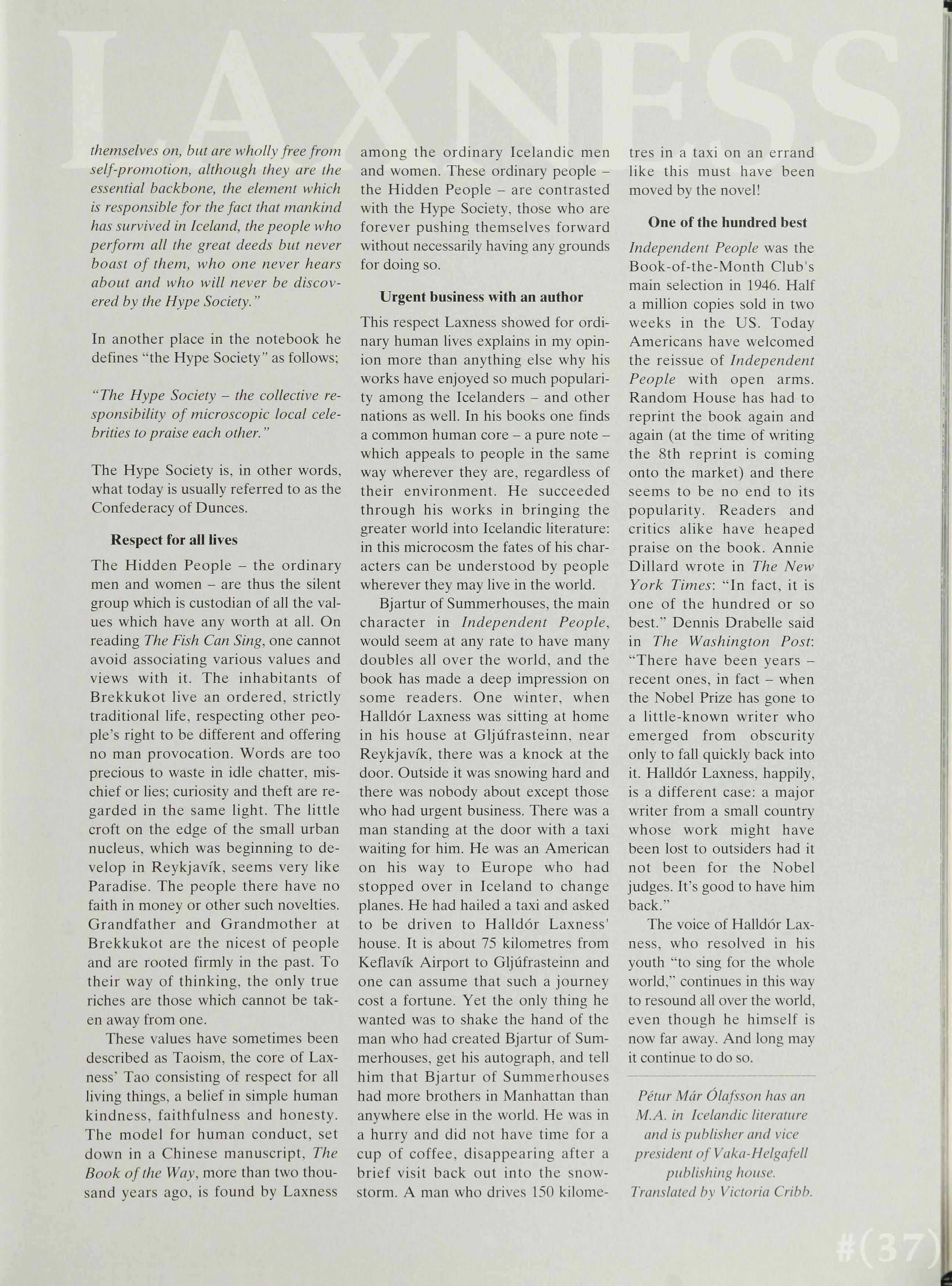

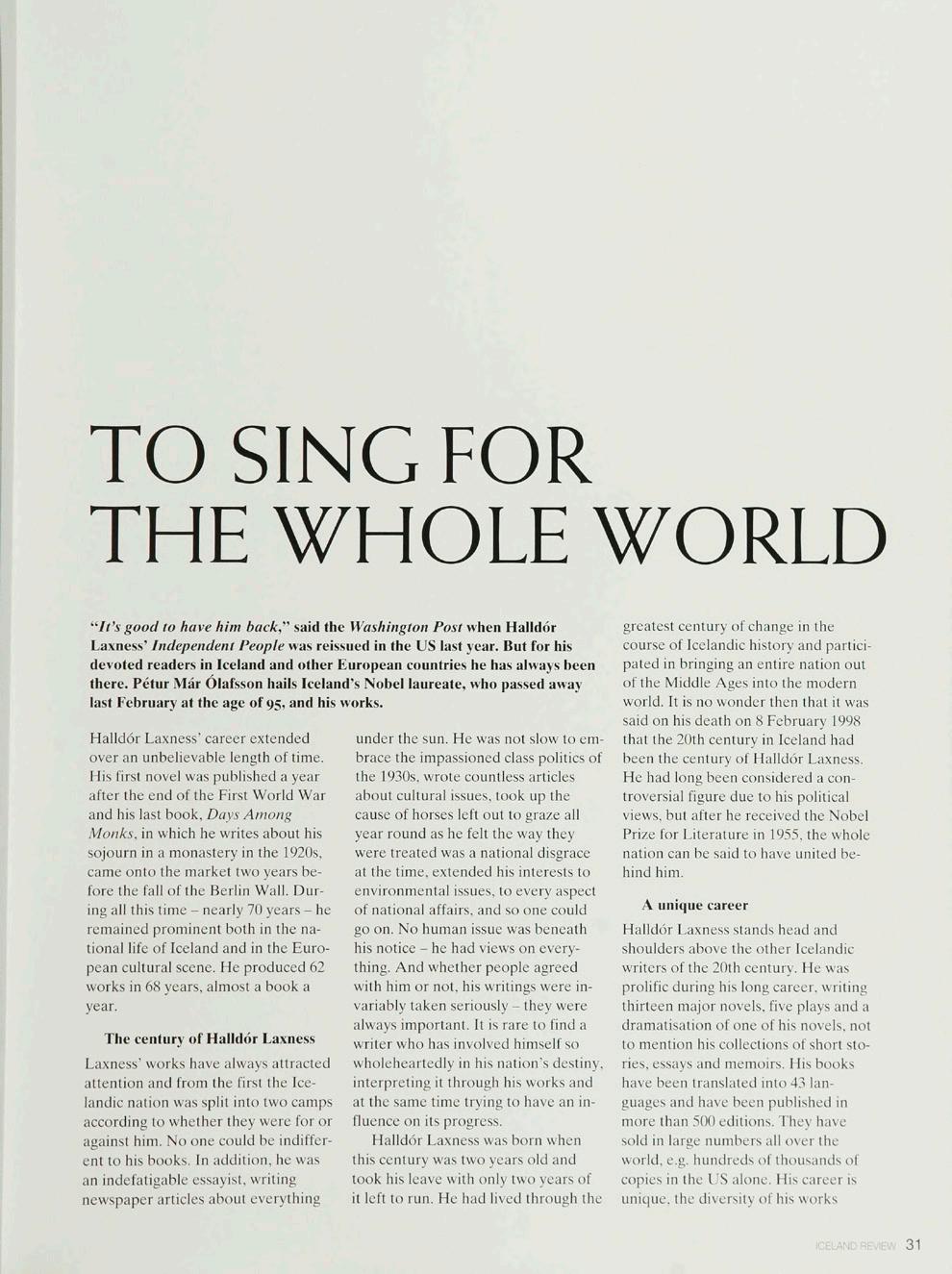

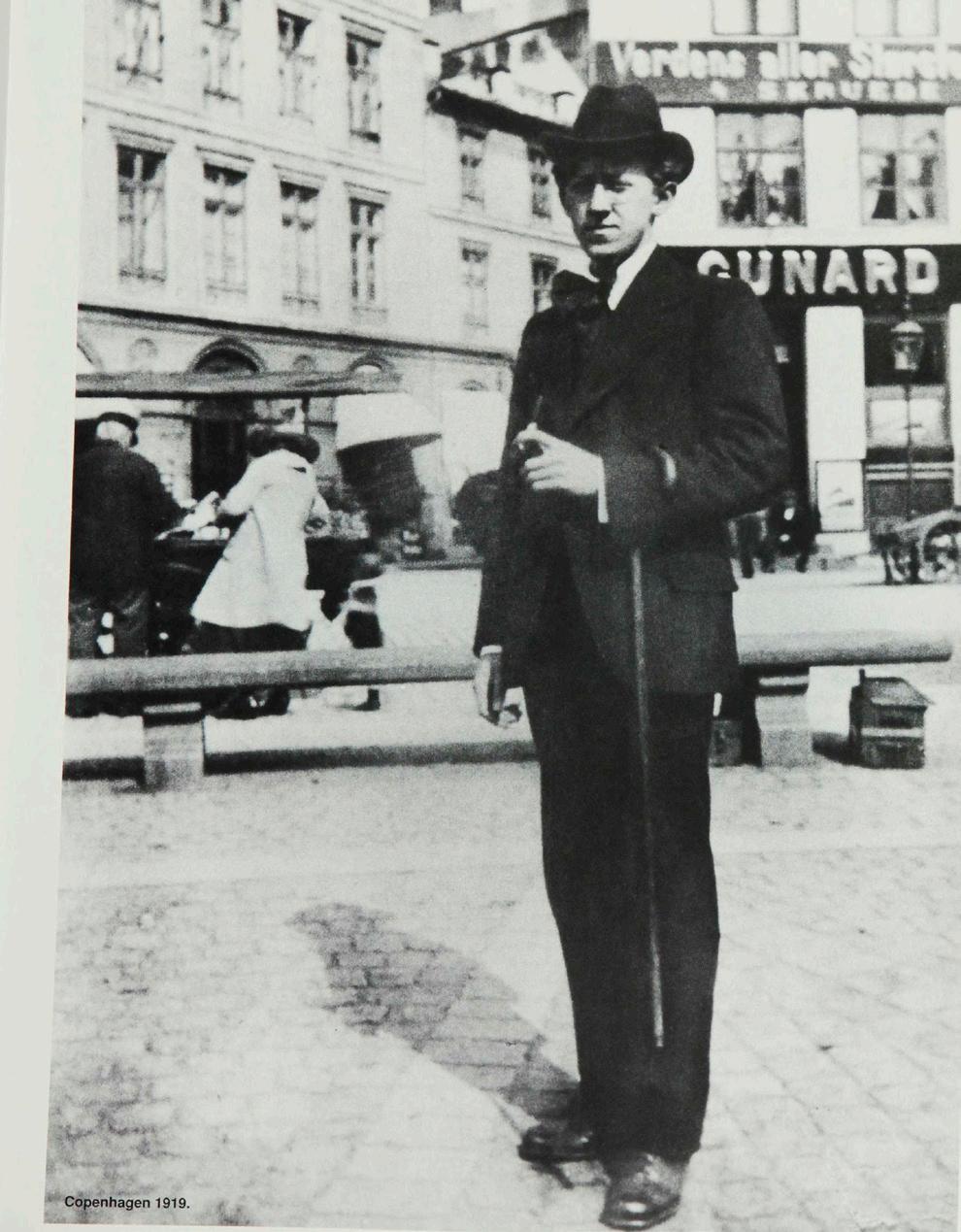

Words by Zachary Jordan MeltonHalldór Laxness was not just one of Iceland’s most celebrated authors –today, he is still the only Icelandic writer to ever win the Nobel Prize in Literature. He received this honour in 1955, but his storied career began long before and

extended long after. In total, he published approximately 62 works in 68 years.

Laxness published his first novel, Barn náttrúnnar (Child of Nature) the year after the First World War ended. He briefly joined a monastery in Luxembourg

before moving to the United States in 1927, where he attempted to write scripts for Hollywood films. During the 1930s, Laxness established himself as a literary powerhouse, publishing Salka Valka in 1931 and Sjálfstætt fólk (Independent

People) in 1934.

The author was no stranger to controversy. He was detained in the U.S. after criticising the country in a Canadian newspaper. He praised the Soviet Union after visiting during the 1930s.

His translation in Icelandic of Ernest Hemmingway’s A Farewell to Arms bothered his fellow Icelanders because of his idiosyncratic use of the Icelandic language. He ruffled even more feathers when he published medieval Icelandic

sagas, not in the traditional Old Norse language but using modern Icelandic spelling, a move considered sacrilegious by contemporary scholars.

Laxness turned his attention to drama during the 1960s, though he still

continued to publish novels. One of his most beloved books, Kristnihald undir Jökli (Under the Glacier) was published in 1968. He only published two more novels in the 1970s but continued to write essays and memoirs before the effects of Alzheimer’s disease slowed him down. Laxness passed away in 1998 at the age of 95. His home in Mosfellsbær, Gljúfrasteinn, has been converted into a museum where visitors can learn more about Laxness as a writer and a person.

Although he later became disenchanted with the Soviet Union, Laxness appreciated the socialist ideal of taking care of the small, everyday people. His books, especially Independent People and The Fish Can Sing reflect these concerns: respect for living things and a belief in simple human kindness and honesty.

Photography by Golli

Photography by Golli

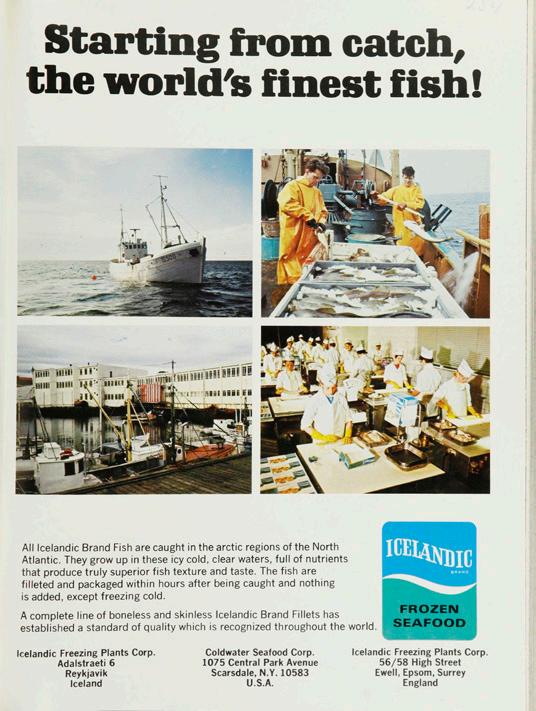

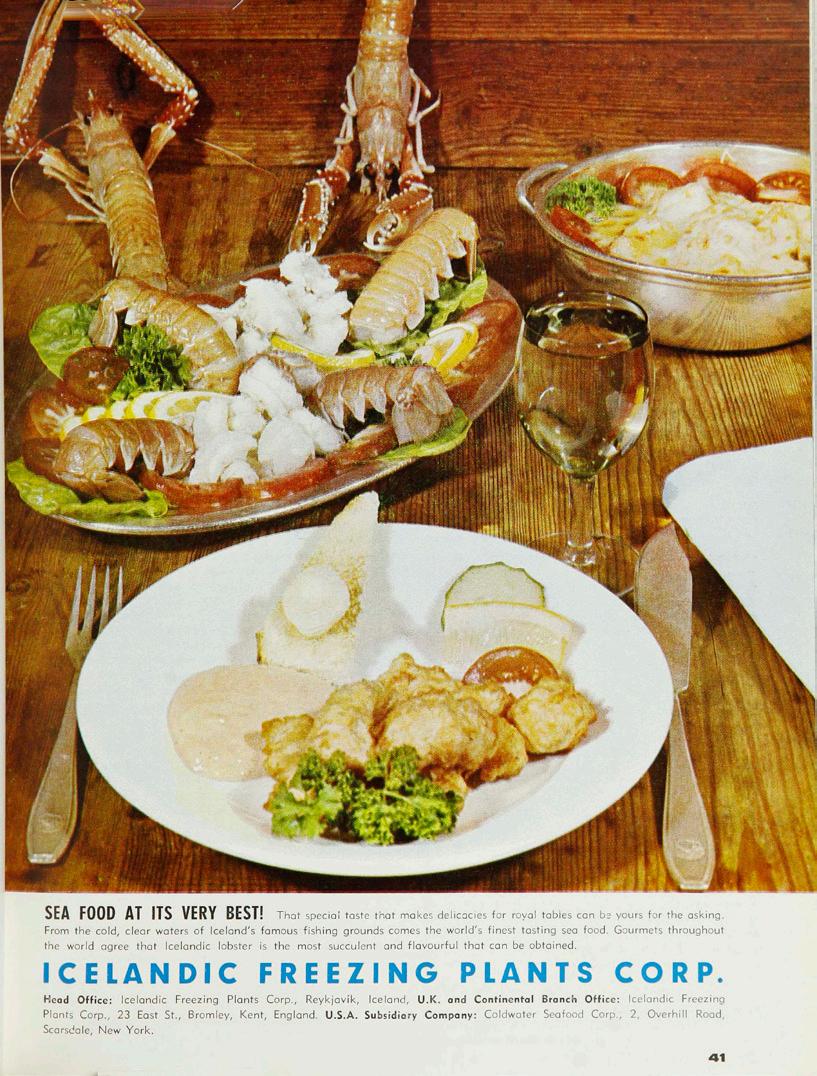

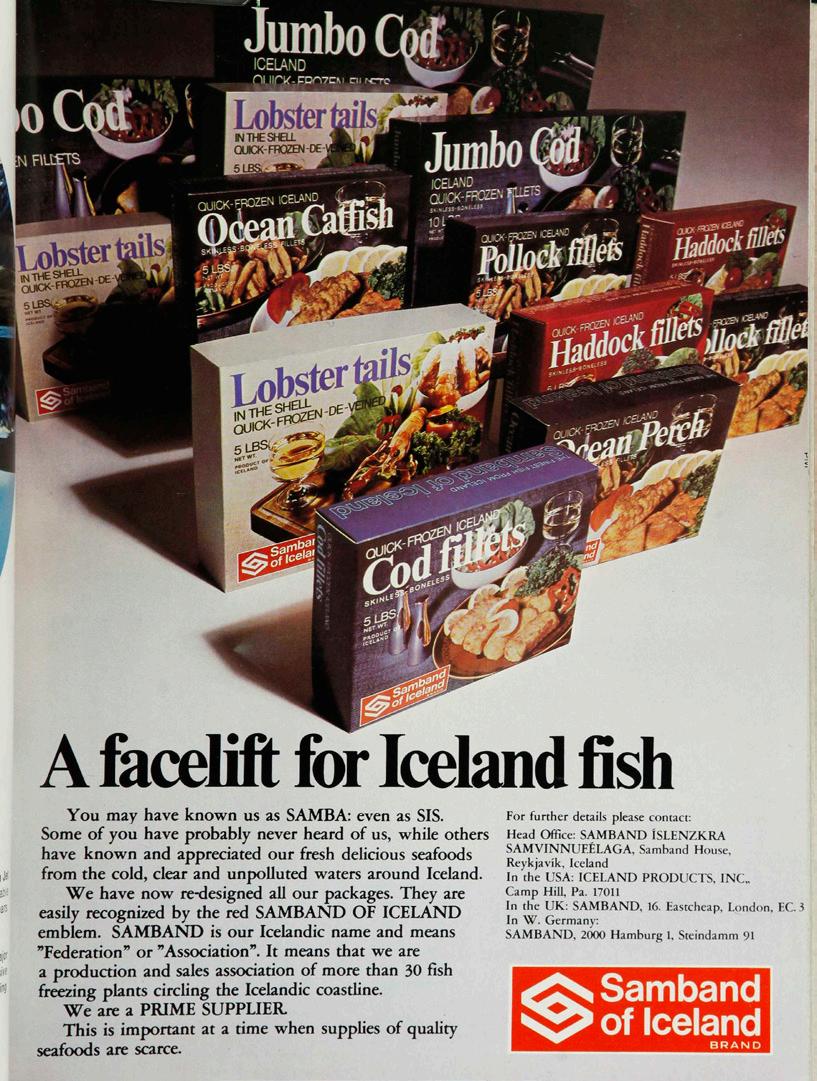

In 2021, when a lower capelin quota was issued in Iceland than had been anticipated, Landsbankinn bank lowered its GDP growth forecast for the year from 3.4 to 3.3%. Capelin may be a little fish, but as a key food source for many other marine species, it makes a big impact on Iceland’s economy and ecology. Commercially, capelin is one of the most important fish stocks in Iceland, accounting for around 13% of export earnings. Only cod brings in more, and it bears pointing out that cod is also dependent on capelin, which may account for up to 40% of its total food.

Stocks of capelin in Icelandic waters have been volatile, making it difficult to predict or plan fishing seasons. The fish have a short life cycle, procreating only once before their ultimate demise, which makes the stock vulnerable to overfishing and changes in the marine environment. In 2019 and 2020, in accordance with the recommendations of Iceland’s Marine Research Institute, no capelin quota was issued at all, while last year’s catch amounted to nearly 600,000 tonnes. In recent years, however, capelin catch has averaged around 350,000 tonnes annually. The bulk of the quota is caught during four weeks in spring.

Capelin is often described as the most ecologically important fish species in Icelandic waters. It is the main source of food for Atlantic cod (another commercially important species in Iceland), and is also a food source for whales, seals, squid, mackerel, and seabirds.

Icelandic boats began fishing capelin in the late 1960s when herring stocks in Icelandic waters collapsed.

Capelin is a small forage fish belonging to the smelt family and is found in the North Atlantic, North Pacific, and Arctic oceans. It is silver in colour and usually measures between 15-18 cm long [6-7 in].

About 80% of capelin caught in Iceland is used to produce fishmeal and oil, while a small amount (less than 20%) is used to produce roe for human consumption. The roe, called masago, is yellow in colour and is popularly used in sushi.

Icelandic fishing boats caught some 477,000 tonnes of capelin last season, the full quota issued. This included around 20,000 tonnes of roe. The total value of the catch is estimated at around ISK 4245 billion [$305 million, €280 million].

Up until the early 80s, Icelanders sometimes caught over a million tonnes of capelin in a single season.

Despite being common in Icelandic fishing nets, capelin is not normally sold in local stores. Hólmgeir Einarsson, a seafood store owner in Reykjavík, decided to stock some this year and has so far sold over 200 kilos [440 lbs]. He says the primary purchasers have been immigrants, who are familiar with the fish from abroad. Some Reykjavík restaurants are also discovering this important fish.

Icelandic capelin migrate seasonally.

In spring and summer, they go north of the Icelandic mainland to feed in the plankton-rich waters between Greenland, Iceland, and Jan Mayen.

Due to rising sea temperatures, capelin has moved further north in search of colder waters. Young capelin now tend to dwell near and under the sea ice around Greenland, making stock sizes difficult to assess.

Climate change and changes in the ocean’s temperature have a direct effect on capelin behaviour. It’s one of the most direct effects of climate change Icelanders can expect in the coming years.

The capelin season takes place in February and March. The window to catch roe-filled capelin before it spawns is even shorter, only around 20-25 days. In that time, a sailor on a capelin fishing boat can expect to earn an Icelandic worker’s annual salary. That is, if capelin catch quotas, and the weather, are favourable that year.

The Icelandic 10-króna coin features four capelin.

Most capelin die after spawning at the age of 3 or 4. The oldest capelin ever found was a 10-year-old female off the coast of Newfoundland, Canada.

A bright, mild, late-summer Sunday greeted the festive locals in the Borgarfjörður region of western Iceland who flocked from far and wide to take part in the Þjóðminningardagur, National Heritage Day, in early August 1898. The popular festival featured a variety of events, including traditional sporting competitions, poetry readings, speeches by noted Icelanders and, perhaps most remarkably, waltzes danced to mechanical music. To the loud, clanging machine-driven tune of a curious large wind-up music box called a calliope, couples young and old swayed and danced joyfully to Johann Strauss’ Radetzky’s March, a catchy waltz tune popular to this day. Other favourites included Hip Hip Hurrah March and Die süßen kleinen Mägdelein.

Before the global dominance of Edison’s audio recordings that came to be known as records, this fascinating machine allowed popular music to be played to crowds in the same way we think of 19th-century street organ grinders. The mechanical wonder was generously loaned to the festival by a somewhat mysterious and clearly wealthy foreigner who had recently moved to Hvítárvellir, a nearby farm

located on the banks of the mighty Hvítá river: the Baron Charles Francois Xavier de Gauldrée-Boilleau.

A fresh new breeze

Hvítárvellir was one of the finest and most productive Icelandic farms at the turn of the century, with many fertile acres of pastureland, dozens of dairy cows, hundreds of sheep, and access to the plentiful salmon in the Hvítá river. The estate was sold to the baron for the modern equivalent of nearly one million US dollars, an unheard-of price even for such a renowned estate. Apparently, he made no attempt to negotiate the price. At the baron’s behest, the farm immediately underwent extensive and costly modifications. In a matter of months, a new wooden building was constructed as living quarters for the farmhands, which was a huge improvement over the turf and stone huts in which most of them had grown up.

Among the modifications the baron introduced were a wide range of new machines that were imported and employed, including a mechanical mower, a hay baler, and an odd device that was meant to flatten the bumpy land by tearing up frost tussocks – a

familiar geographic feature of Icelandic pastureland. Farmhands’ wages were paid in cash, which was a rarity in those days. The baron demanded to be acknowledged with proper respect at all times; in his presence male farmhands were expected to doff their caps while women were meant to curtsy. The baron insisted on personally approving every hire because he believed he could determine the applicant’s trustworthiness simply by looking deeply in their eyes.

The locals were surprised and delighted when the esteemed Baron Bolló, as the locals dubbed him, showed up unannounced at the festival’s reception tent, dressed in exquisite riding gear and casually smoking a Russian cigarette. He was accompanied by a good-looking young man in a suit and tie who he introduced as his cousin, Richard Lechner, whom the locals soon began referring to as the count for no other reason than he was associated with the baron. The foreign pair spoke together in German but made praiseworthy efforts to speak to the festival officials in Icelandic. The dashing foreigner with the lofty noble title asked if he might be permitted to partake in their festivities, which would

be completely unprecedented and was immediately approved. Curiosity piqued as the baron registered for the annual horse race.

Foreigners, often wealthy Englishmen, were not unknown in West Iceland at the time but were generally considered eccentric if not arrogant, mostly keeping to themselves and ignoring the locals. That such a notable figure as a baron would deign to join the Icelanders in their local gala and even compete in a horse race was welcomed with giddy anticipation.

His background and reasons for moving to Iceland were largely unknown, but the charming baron, who had become their neighbour just weeks before, had already garnered a reputation for being a progressive and cultured man of vision and conviction. He expertly mounted his beautiful stallion and trotted in perfect tact to the starting line, deftly demonstrating his riding prowess. Hundreds of dismayed onlookers watched as the baron was first to cross the finish line and became the horse race’s undisputed winner. While most cheered the victorious foreigner, some chagrined locals were understandably humiliated, grumbling that the wealthy foreigner must have fed his horse some special foreign fodder to defeat them so handily.

As Baron Gaudrée-Boilleau accepted his award for placing first in the horse race, speculation about just who this man was and where he came from was on everyone’s lips. He was thought to be French based on his name and general appearance, but he had come to Iceland from the Bavarian city of Munich and spoke flawless German with his so-called cousin, Richard. Letters addressed to him, however, came regularly from the United States, which led some to assume he must be American. According to the farmers who sold him Hvítárvellir farm, he spoke English with a distinctive upper-class accent, sounding like the British lords who sometimes fished the Hvítá river. It was rumoured that one time a young woman who had been working as a

farm hand at Hvítárvellir walked up to him and impudently asked; “Who are you actually? And why did you come here?”

The baron stared at her momentarily, then replied in clear and correct Icelandic: “Don’t you know it is rude to ask personal questions?”

Only a few months earlier, to wide acclaim, the baron had made his first public appearance. It was a sunny evening in late May 1898, and a concert was held to inaugurate Reykjavík’s recently completed Iðnaðarhús, Craftsmen’s Hall, a relatively large wooden building that serves as a theatre, meeting place and concert hall. Iðnó, built on the banks of the city’s lake, Tjörnin, still stands to this day. The youthful baron proved to be an exceptionally talented cellist. He was also a proficient pianist and an accomplished composer. After promising his local acquaintance, the writer Benedikt Gröndal, to perform at the auspicious Reykjavík Music Association event to a packed audience of some 200 Icelanders, the baron had turned up with a 250-year-old Cappa di Saluzzo cello, an instrument which was completely unfamiliar to the average Icelander at the time. His masterful playing of the “knee-fiddle” or hnéfiðla, as it was reported in the following day’s newspapers, reportedly left musicdeprived Icelanders astounded, calling for encore after encore. To the delight of the audience, the baron then improvised expertly with an a cappella singing group, which he clearly enjoyed. When asked by a fan whether he would be willing to perform regularly, he answered that he was actually giving up his music career, but he would be willing to play occasionally for charity. His new passion, he said, with a grin but without any touch of irony, was to become an Icelandic farmer.

Það er strok í honum – He’s a flighty one

Just why the baron chose to become a farmer in Iceland of all places was not clear to anyone. With all his impressive heritage and fine skills, he was used to a wealthy cosmopolitan lifestyle in America and Europe. Apart from

studying music for years in Munich, the baron had been cruising frequently to London or New York or spending time in places such as Algiers when not at his family homes in Paris or on the Italian Riviera. Already fluent in seven languages, the baron managed to learn Icelandic with remarkable speed. He came from a privileged background: he was the son of a wealthy French diplomat and had been educated at expensive English boarding schools. His more practically-minded brothers in America were as worried about him as they were mystified, writing: “He was flying high after arriving in Iceland, which made us happy, as we had been following him between hope and fear. On the other hand, we knew very well how quickly things could change for our brother. We knew of his plan [to move to Iceland], but we didn’t take it too seriously. We had hoped that our patience would be rewarded, and that Charles would realise what a pipedream this was but hope that he would somehow find happiness and peace in this absurd place.”

Farming in Iceland was not an especially profitable endeavour even at the best of times. It requires extensive knowledge and hard-won skills, as well as a certain disposition. It was not long before his farmhands and neighbours began to notice the baron’s odd behaviour, demonstrating inexplicable apathy and irrational carelessness on many occasions. When purchasing a horse, he would avoid wasting time with troublesome negotiating and simply ask the seller to name his price. In the middle of important farm projects, which would consume his attention for weeks on end, he would suddenly lose all interest, mount his horse, and ride away without a word of explanation. At other times, the baron would capriciously summon his expensive imported private steamship, which was docked nearby, and order it to sail him to Reykjavík where he owned a comfortable home on Laugavegur. Local farmers commented that the baron was like an untamed horse that would bolt, running off at the slightest distraction. And that the baron

was “likely not wholly sane.”

When he decided it would be pleasant to stay in a luxurious tent with all the amenities on a nearby lake, the baron called together the various local Icelandic farmers who owned it and offered them triple the estimated value. After three days of hunkering in his tent while it rained continuously, he abruptly rode back to Hvítárvellir, abandoning his latest acquisition, never to return. In the summer months, the baron would practise his marksmanship with a pistol by shooting at golden plovers. He insisted on eating grilled salmon and mashed potatoes nearly every day. When one of his servants was heavily pregnant, the baron was so repulsed that he fired her immediately. Whether

out of shyness or arrogance – and despite his language abilities – when the baron was approached in public he would invariably pretend not to understand and simply walk away.

After a few months of drab living at Hvítárvellir through the autumn and winter of 1898, the baron was bored. He saw business opportunities everywhere, claiming Reykjavík could double or triple in size with the right investment. It was then that he decided to take ever-bigger risks with his remaining money, taking short-term high interest loans when necessary.

Looking to drive progress and change, he financed the construction of a hugely expensive modern concrete barn which was to house 50 milk

cows and provide higher-quality dairy products to the citizens of Reykjavík. The unfortunate project was destined for failure. Locals did not know what to make of the baron’s bold innovation and baulked at buying milk from what they considered a foreign company. The barn’s construction alone cost three times its budget and the cows produced much less than anticipated. By the summer’s end the baron became depressed and fell seriously ill. Unable to even hold a pen, he was bedridden for months. Before the end of 1899, he was forced to sell the barn, his precious steamship, and various other properties at a tremendous loss in order to pay off his rising debts.

Upon his recovery, he dismissed

Barónstígur street in downtown Reykjavík is named after the baron. The building on the right was built by the baron for a dairy production business venture.

the bankruptcy of his dairy project as regrettable but insignificant; there were far greater rewards to be had which would dwarf the year’s losses. The baron’s new plan was to create a huge fishing company with nearly a dozen ships and a modern harbour. The required financing would flow in, he was sure, because it was obvious that Iceland needed to compete with the European fleets that had been exploiting Icelandic fishing grounds since the Middle Ages. All it would take was for the Icelandic Parliament to approve the new fishing company’s charter; nothing but a trifle, surely. Flush with fresh loans from local Icelanders, the optimistic baron set off by ship to London to raise the rest of the capital. Interest in the innovative plan was high and the baron saw no chance of failure.

When the Parliament broached the issue in the summer of 1900, however, opponents pointed out that the baron was no Icelander. Discussion went on for months, but the charter’s approval never gained a parliamentary majority. The baron’s fishing company, like so many of his business ventures, was stillborn.

It was a cold winter evening in 1901, between Christmas and New Year’s, in London. On a regional passenger train from southeast London to Victoria Station, the normally uneventful journey was interrupted by the crack of a lone gunshot. The piercing report resonated in the confines of the narrow train carriage and briefly, a nervous silence ensued. The train’s two conductors,

who had been checking tickets, quickly made their way toward the apparent origin of the shooting: the only firstclass cabin with closed curtains.

As the conductors cautiously opened the cabin door, their eyes were drawn to an irregular dark stain on the wall, just above an empty seat. Then, they caught sight of a well-dressed young man sprawled unnaturally on the floor, a dark, sleek pool of blood surrounding his head. He wore a gentleman’s high-collared white shirt with an ornate cravat and an elegant waistcoat. They stared wide-eyed at the gaping wound in the man’s head and the blood soaking his wavy brown hair. An antique revolver lay on the floor next to his lifeless hand, the last traces of gun smoke still drifting lazily from the single barrel.