HERITAGE

All around the world, by continent and country, by region and city, by town, village or rural area, designed structures and modified landscapes testify to past and present patterns of human settlement and ways of living. Buildings built and used by previous generations tell us how those people lived and worked and what they valued.

These historic structures are often protected from change either because their communities revere them as they are, or-as in the UKmany layers of statutory protection have been established over the last century to safeguard their value, as listed buildings, conservation areas, scheduled ancient monuments or world heritage sites.

The built environment is not unchanging. It is dynamic and constantly subject to many imperatives for change, reflecting economic growth and decline, patterns of ownership, new ways of living and working, of population growth and rising standards of living which bring new technologies of construction and movement.

Introduction

The purposes that created the structures of the past also change, raising questions about whether buildings are to be re-purposed or demolished and replaced. There is something about seeing significant historic buildings re-energised that is infectious, and key to the regeneration of communities.

Where historic buildings are valued and protected by statutory planning processes, how they are re-used, and the ways they are altered matters, and needs to be done so they can tell their story of origin as well as they serve their new one.

Historic buildings need to be kept in good repair. This means understanding how they were built, their processes, their materials, the craft skills used to create them, so their narrative and their significance is not diminished by ill-considered work. Funding repair needs them to be in active use as much as possible.

As the built environment changes, the setting or context of historic buildings is also subject to change. Will this change enhance the community’s understanding of this particular building’s significance and value, or diminish it?

The legal framework that now applies to historic building change and environments was put in place to respond to successive waves of economic development. Often this has put new types of structures only decades old buildings under risk of loss leading to focussed consideration of their value. In the statutory planning process, listed buildings and conservation areas are treated as assets the community has a legitimate ownership stake in.

Currently, new change imperatives are directing emerging planning policy all around the world. For instance, countering climate change means supporting compact cities and favouring public over private transport. As urban centre sites get redeveloped at higher densities, new questions have to be asked and weighed about the value of their historic buildings in this new future.

Nash Partnership has over 30 years’ experience of working with the historic built environment, from works of repair, alteration, conversion, new buildings in historic settings, as conservation and design architects, planners, regeneration consultants to urban designers and geographers. In the following sections of this brochure, we explain how this experience was built.

The handling of historic buildings has its own ethos; a fully researched base understanding of their history, value and the significance of a place is built up before any proposals for change can be judged and allowed to proceed. This ethos of research / understanding / valuing / assessing, learnt through our early years as conservation architects, now underwrites all the work of our untypically wide range of professional disciplines.

Humankind has, over thousands of years, imposed buildings and other design structures on a natural environment that had been evolving for millions of years. The study of the ecology of the natural environment has developed an academic framework with disciplines and tools for managing this understanding and their analysis. It is surprising in many ways that we have not yet brought the same kind of structural thinking to the ‘what, how and why’ of the built environment. Here, no one current built environment professional discipline holds the key. Our team includes a wide diversity of built environment disciplines to apply the same research, rigour and creative understanding to the quality and value, and needs of all the already built environment as it responds to the present drivers of change.

Claverton Manor, Bath

We have advised the Trustees of the American Museum in Britain over 23 years, helping the estate build the social, cultural and economic capital of this intercontinental institution

Range of Past and Current Work

Nash Partnership was established in 1988 in the World Heritage City of Bath.

Our founder architect Edward Nash was, from an early age, curious about the variety of the built environment. Before setting up practice in 1988 he worked in rural practice, landscape design, in local planning, as a conservation officer and in city centre regeneration. Partner Robert Locke worked for English Heritage (now Historic England) on projects to repair and adapt their heritage estate.

Our early work as architects involved projects of historic building repair, restoration and re-use, conversion or new build design affecting the settings of listed buildings. Based in Bath, Britain’s only World Heritage City with 5,000 listed buildings, has meant almost all of our projects involved heritage value judgements, in acting for private householders, community institutions, local authorities and commercial developers.

The deep economic recession of the early 1990’s led to the closure of large swathes of British industry and we were appointed to handle many projects of re-use when the future of historic buildings appeared a critical

factor in their planning applications. In the following years, change in the public sector property brief brought forward many historic former hospitals, education and MOD sites needing similar skills across the UK. During these years we came to understand the complexity of the task the statutory planning process was being charged with. So we built up our fully integrated team with planners to ensure that this aspect of built environment intelligence was part of our professional offer. Integrating these skills allowed us to contribute to clients’ needs by leading large urban projects, building up experience in handling planning appeals and providing expert witness evidence in heritage planning matters.

As the scale of such projects grew we had a lot to learn about the role of urban and public realm design. The best urban environments of the past have succeeded because they have served their users well. Understanding how they work is critical to effective new design. Our experience in designing wholly bespoke housing schemes, often in heritage or highquality landscape contexts, meant work of this kind came to us.

1. Lamb Yard, Bradford-on-Avon

Town Centre Regeneration

2. Cheltenham College

Estate masterplan

3. Bradford-on-Avon

Mixed use regeneration of town centre

4. Newlands Farm, Bristol

Restoration of fire damaged properties

5. Holystreet Manor, Dartmoor

Remodeling of estate and country house for 21st century living

6. Historic Woolwich

Historic value expert witness for DLR extension

7. St. Michaels, Tidcombe

Roof repairs and replacement

8. Cheltenham College

Heritage stock utilisation review

9. Hartlebury Castle, Worcestershire

Business plan advice during purchase from Church Commissioners

10. Victoria Pier, Colwyn Bay

Structural crisis analysis

1 5 8

2 3 4 6 7 9 10

Although we always felt that the historic environment had taught our team a lot and continues to do so, we could see this was not evidenced in the way UK housing on a large scale was being delivered in layout, street design, urban grain and landscape strategy. So much ill-considered housing was rapidly appearing on the outskirts of historic English towns. We began working much more extensively with the national and larger regional house builders, understanding what forces determine these projects. In the post-2000 years, the then Labour government framed policies to grow expectations of the quality and egalitarianism of the public realm and housing and its sustainability profile, under the Sustainable Communities Programme. We handled many such commissions, some of which were funded or managed through the Home and Communities Agency or the then Regional Development Associations. Many of their project sites also involved significant heritage assets in defining their design parameters.

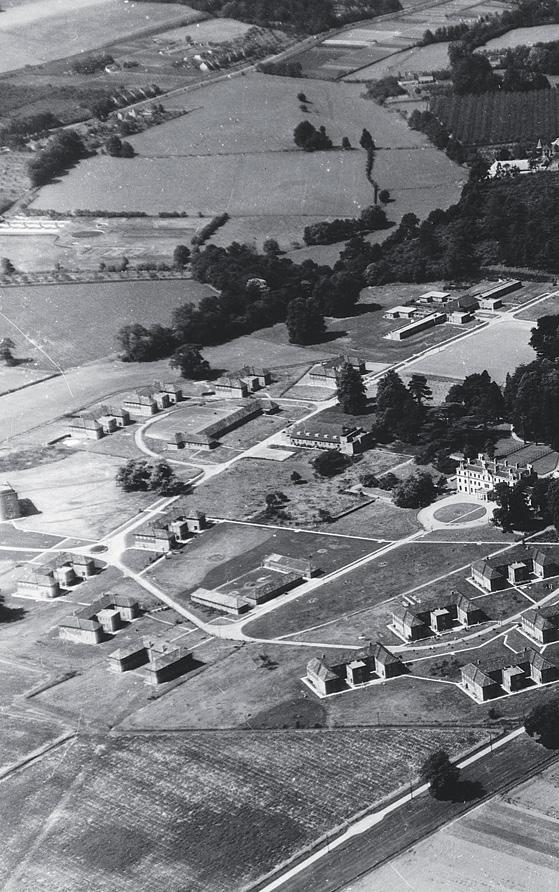

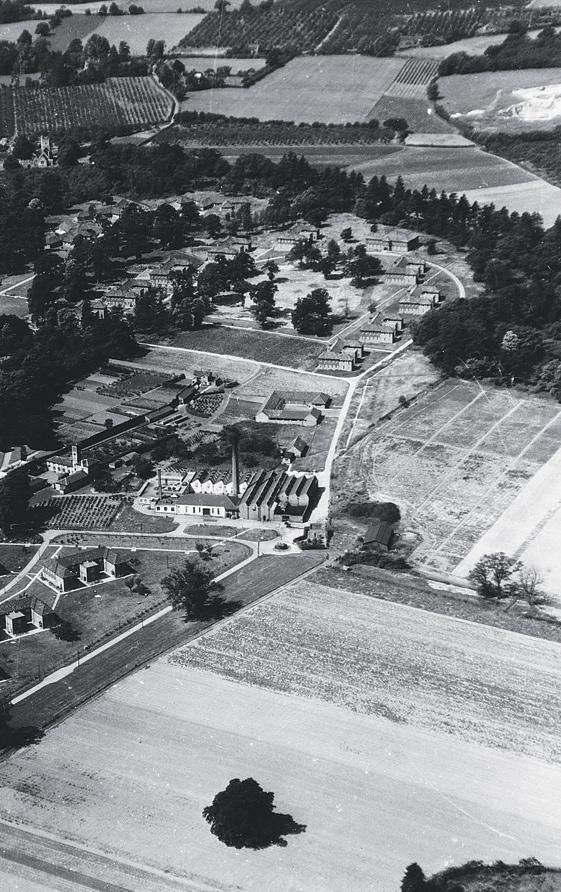

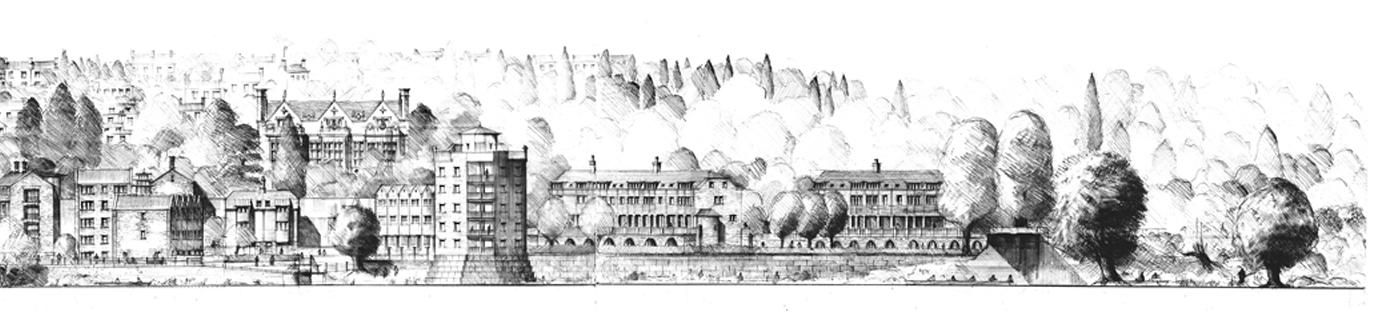

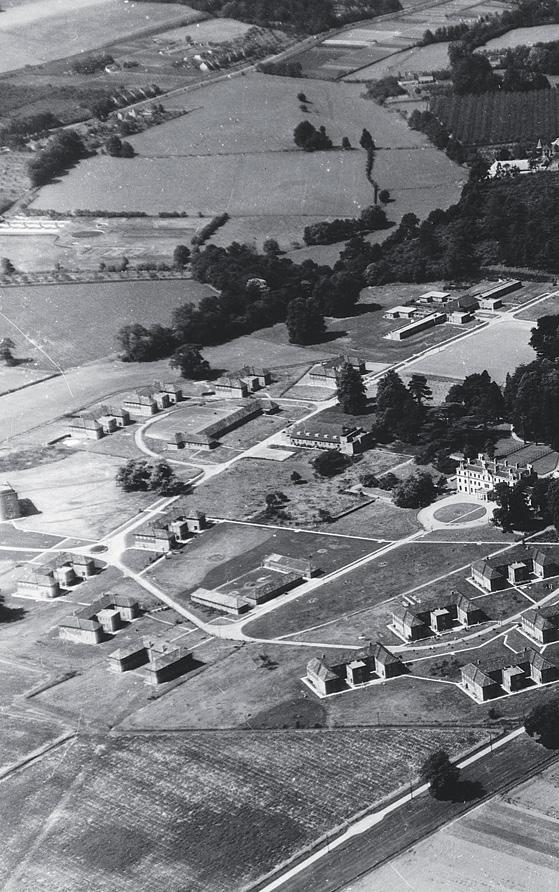

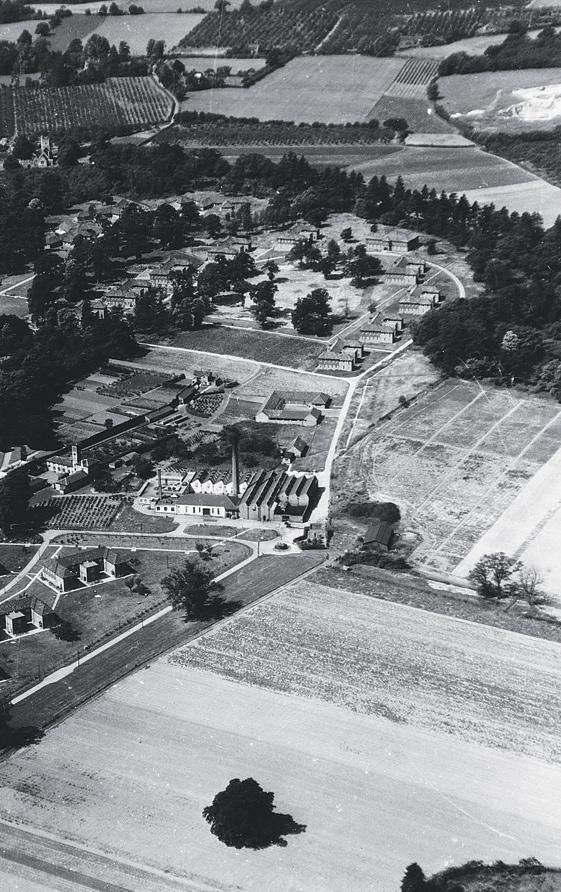

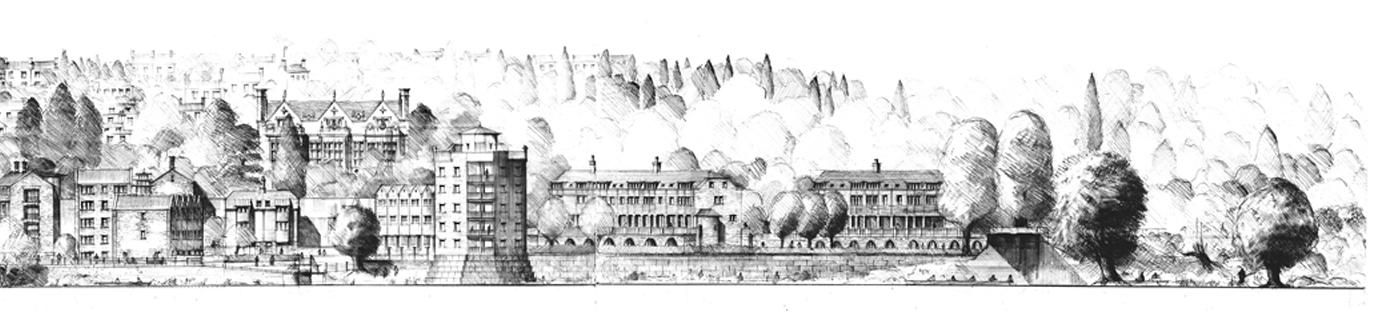

Leybourne Grange, Kent Masterplan for wholesale redevelopment of a large country estate around historic assets after end of hospital use

Leybourne Grange, Kent Masterplan for wholesale redevelopment of a large country estate around historic assets after end of hospital use

The draining away of investment confidence in the years following the 2008 recession created new imperatives and a need for property investors, developers and public sector to build their development strategies on stronger intelligence foundations before investing in regenerative change.

We grew our higher regeneration skills and supported our team’s work in this sphere with dedicated research and land data geographers. This in turn led to commissions for land-based socioeconomic and developmental history and futurology studies acting for both private and public sector clients.

Through this broadening out of our skill base, we have continued to practice as project architects handling a great variety of historic assets or design change affecting the setting of such assets. Our team of conservation architects and planners, trained and experienced in this field are held in high regard for the depth and sensitivity of their work, achieved on projects both small and large in scale.

The variety of use, scale and eras of buildings we have worked on over 30 years have been one of the things making handling heritage projects so interesting. As well as work on several hundred heritage dwellings we have handled transport structures, churches and cathedrals, public institutional buildings, the structures of industry and seaside piers; from the Roman era to late 20 th century.

We understand our clients need carefully focused, flexible consultants, able to support them whether they are historic and listed building owners, institutional and local authority asset holders, rural/urban property estates holders investment portfolio holders, local authorities or central government.

We are used to tailoring our services for any particular client’s needs and can draw in specialist expertise from among our planning and design research and urban design colleagues where any project requires.

Our work takes us anywhere in the UK and occasionally overseas, where we have handled projects in Europe, America and the Mid and Far East.

1 2

1. The Orchardleigh Estate Lodge, Frome

Bringing a derelict parkland lodge back into use

2. Burwalls, Bristol

A sensitive restoration of a Grade II listed mansion

3. Henley Hill, Bath

Repair and conversion of isolated Cotswold barn

4. Great Pulteney Street, Bath

Conversion of hotel in Grade I listed building

5. Ironbridge, Ironbridge Gorge

Major project of asset protection for the Ironbridge

Gorge World Heritage Site

6. Coalport, Ironbridge Gorge

A new public realm setting

3 4 6 5

Range of Skills & Professionalism

Architects and planners proposing change affecting the fabric or setting of historic assets have to engage with conservation officers from local planning authorities and Historic England. Often, as well, engagement is needed with a range of specialist consultees from local or national historic amenity societies, some of which have the status of statutory consultees in the planning process. All of these are highly experienced people who by working in a region, city or a town have gained particular and rare experience of the kinds of regional buildings they are uniquely exposed to on a daily basis. They are also very busy and so tend to have to make judgements about what they can or cannot support based on what they have been presented with or can learn in the limited time available to them, for any one proposition.

For a planning or listed building applicant to feel in control of a pre-application engagement process it is important their architects and planners are well informed through local experience, the ability to source historic research, and rapidly understand the significance of a building or a site when they are commissioned.

a characterful

Eardington Mill, near Bridgenorth Conversion of a semi-derelict historic mill into

home

We have built up a widely experienced conservation architect and planning team, all of whom have experience or specialist training qualifications such as RIBA (Specialist Conservation Architect) status or are on the AABC (Architects Accredited in Building Conservation) Register. They boost their knowledge through their membership of specialist conservation bodies such as SPAB (Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings) or the IHBC (Institute of Historic Building Conservation) and attend specialist courses in legislation and best technical practice. As historic buildings are a passion, they visit historic buildings frequently for their own interest. Across our team we have individuals with career experience of structures of particular types, churches, industrial era buildings, 20th century heritage, particular historic eras or geographies.

All good conservation architects are trained to be able to access research sources, to ‘read and understand’ the developmental evolution of a building, often through many complex stages of build. They understand the legislation and policy tests local planning authority officers will apply when judging a proposal and the kind and extent of information

3 1 2

they will reasonably ask for when applications are made. They will present the relevant evidence, the need for change, discuss options, and weigh the project’s case in relation to ‘harm’ and mitigation with clarity and efficiency. They are also used to presenting evidence at planning appeals, should this be necessary.

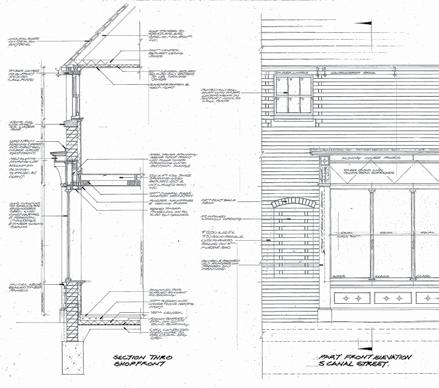

Because of the pleasure historic buildings give to our heritage team, our trained and experienced architects are also sensitive designers, aware of the visual and character qualities of historic buildings and how new design can sit alongside them, with sensitivity, to the benefit of both. They have to understand how a wide range of traditional construction materials have performed and have excellent technical knowledge especially in design for long term sustainability.

Like all professional people they enjoy applying and deepening the specialist knowledge they have and sharing it with others.

4

1. Belcombe Court, Wiltshire Expanding the gardens of a Grade I listed country house estate

2. Saxonvale, Frome Town centre expansion

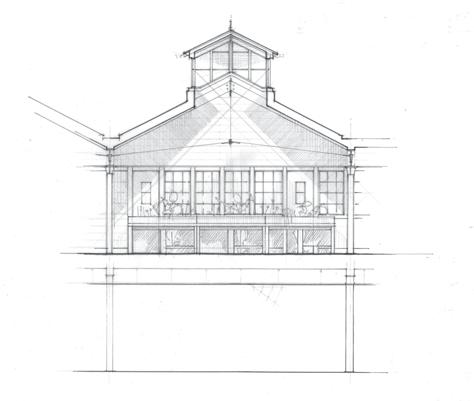

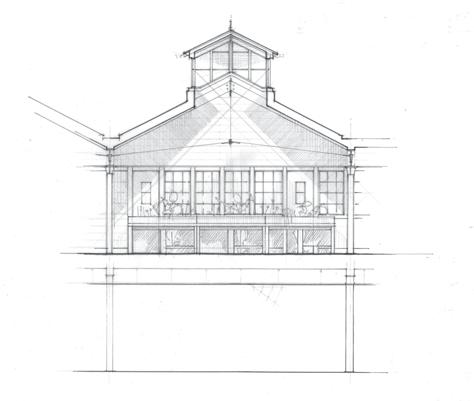

3. American Gardens, Claverton Manor New pavilion entrance

4. U.S. Embassy compound, London Re-modelling and extension of listed building

Working with Heritage Assets

EXPERT EVIDENCE

HISTORIC RESEARCH

Physical change to historic assets or affecting their setting risks causing harm to perceptions of their significance. So showing in-depth knowledge and understanding of their history and value is essential to any successful planning submission. When the Docklands Light Railway was extended into Woolwich, the project had great political momentum. But the preferred option for locating the Woolwich station had failed to recognise the town’s historic street plan and wealth of locally listed buildings. Our evidence to the public enquiry led to a relocation, so relieving the risk to our client, British Telecom, for whom a new regional broadband exchange was at risk from structural vibration.

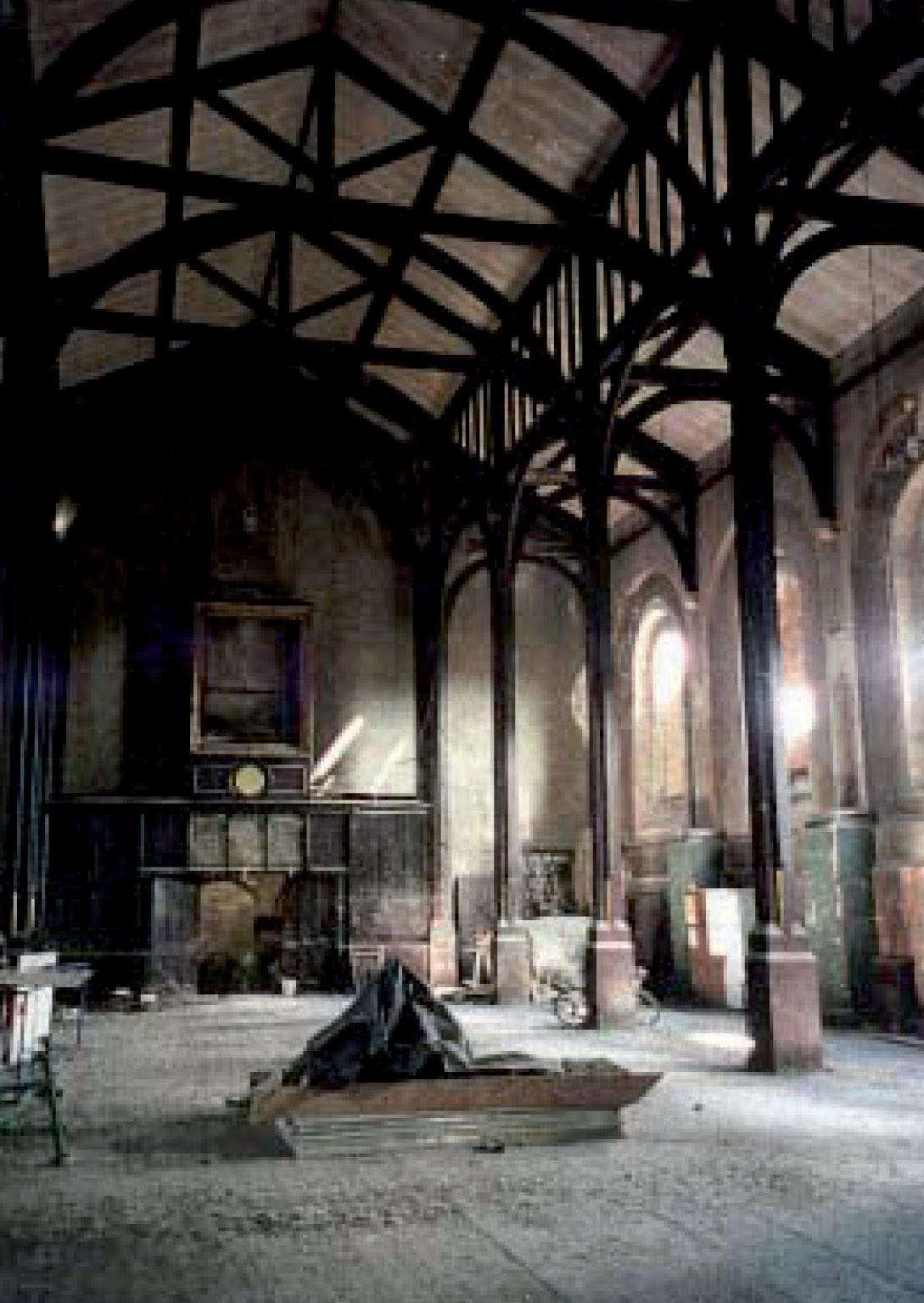

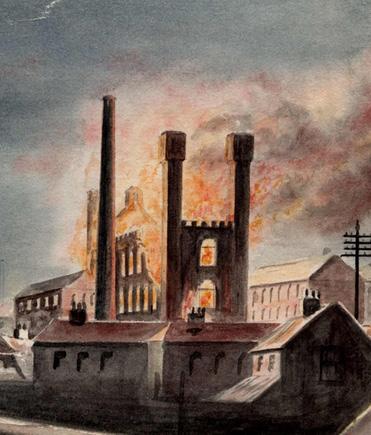

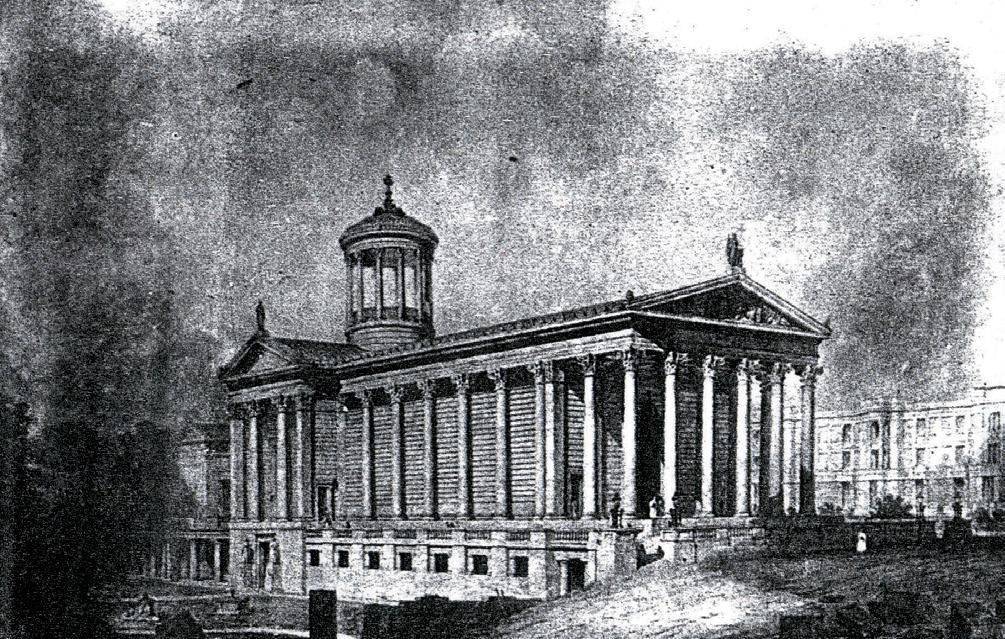

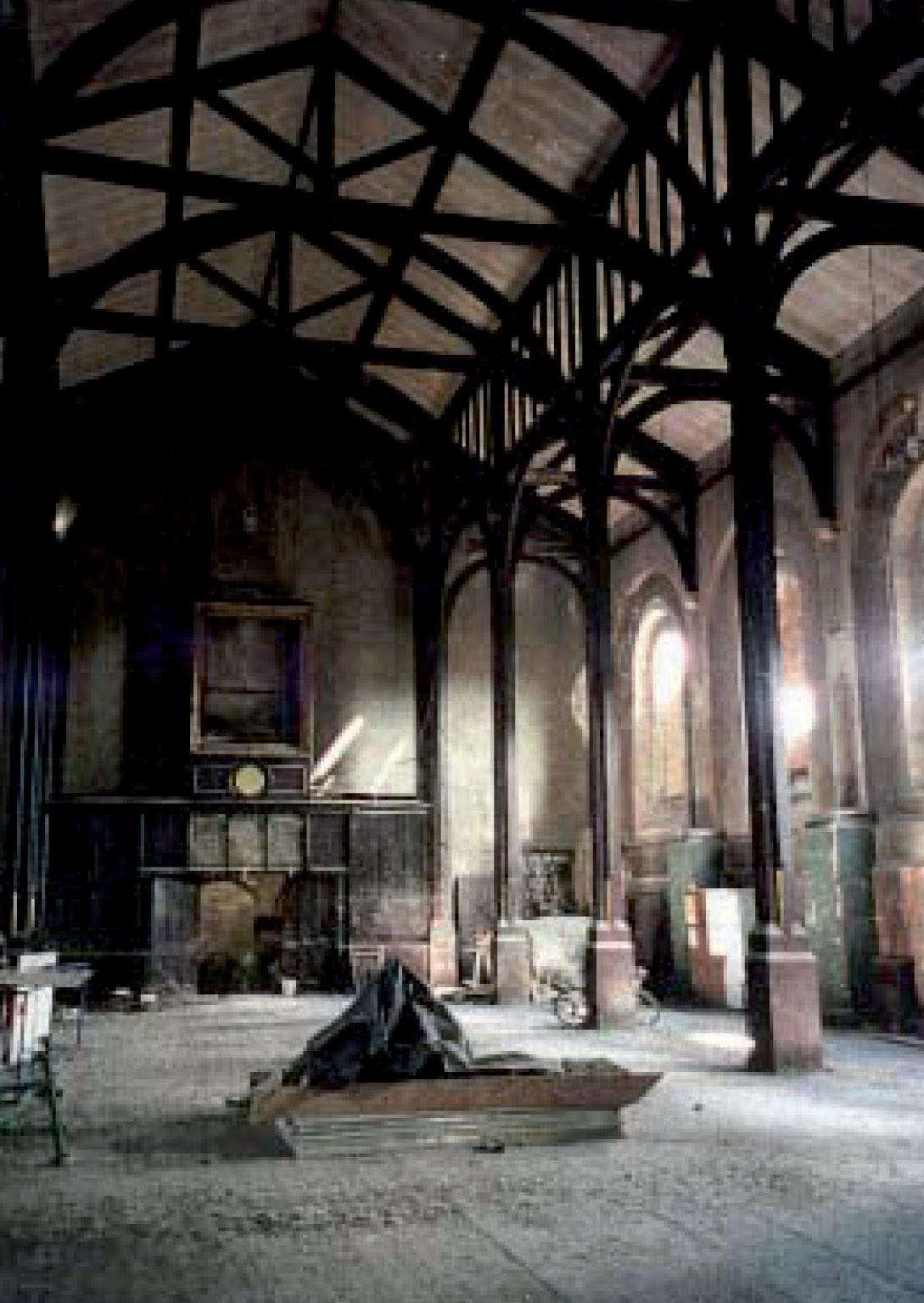

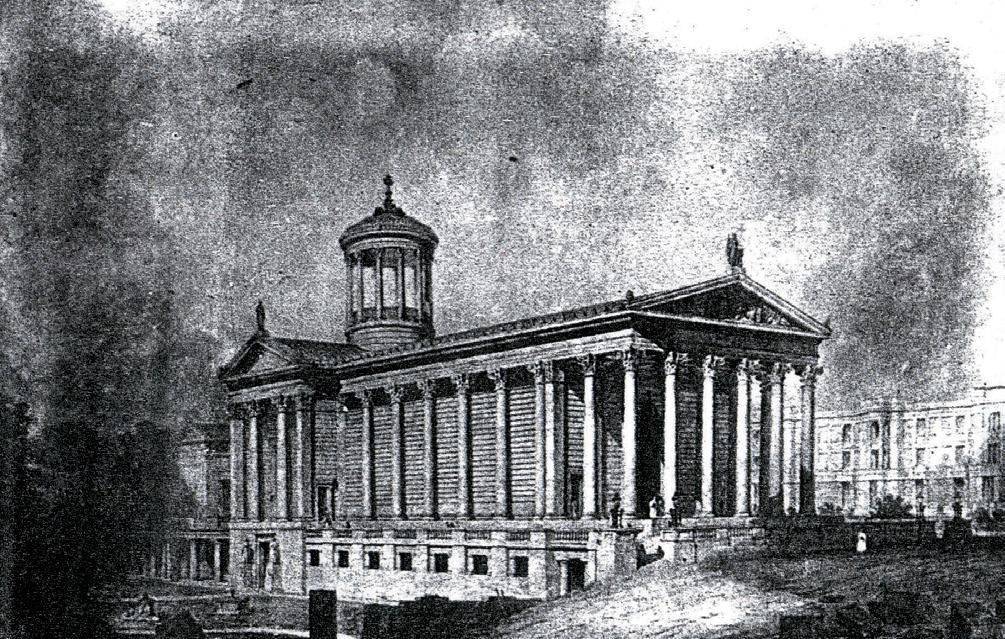

Some of the evidence of past use, materials or construction can be found in a building or on its site. But invariably the story of why, by whom and for what needs to be documented evidence now often scattered in a diversity of archives. When we worked to show how selective re-use of the former ProCathedral in Bristol’s Clifton was a credible proposition over demolition, such documented sources were rare. We were seeking to clarify which parts of the structure were attributable to each of its two 19th century architects, HE Goodridge and Charles Hanson. Study in Bristol city’s extensive archives and those of the Catholic Church created a firm basis for discussion of the re-use alternatives proposed, resulting in a planning permission which allowed most of this complex site’s structures to come back into productive use again after 30 years of dereliction.

SURVEY AND INVESTIGATION

UNDERSTANDING AND EVALUATION

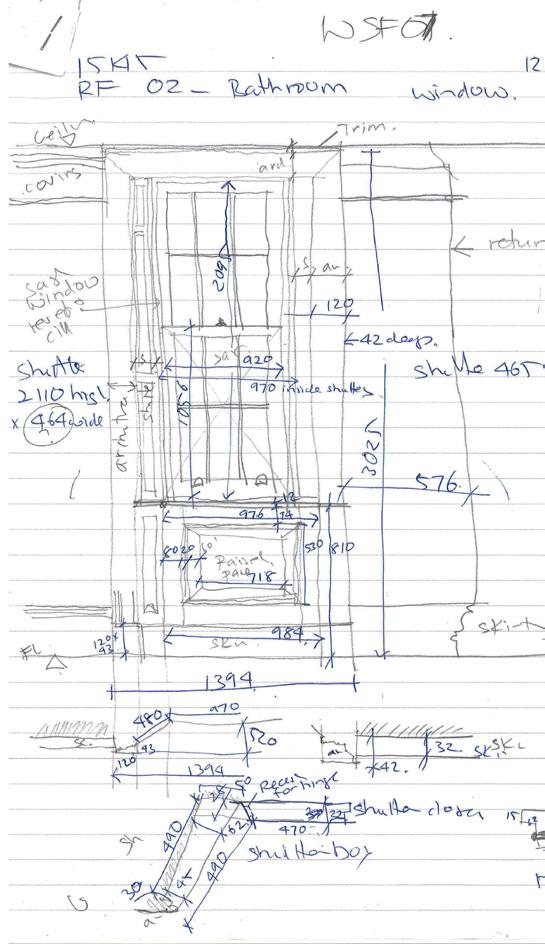

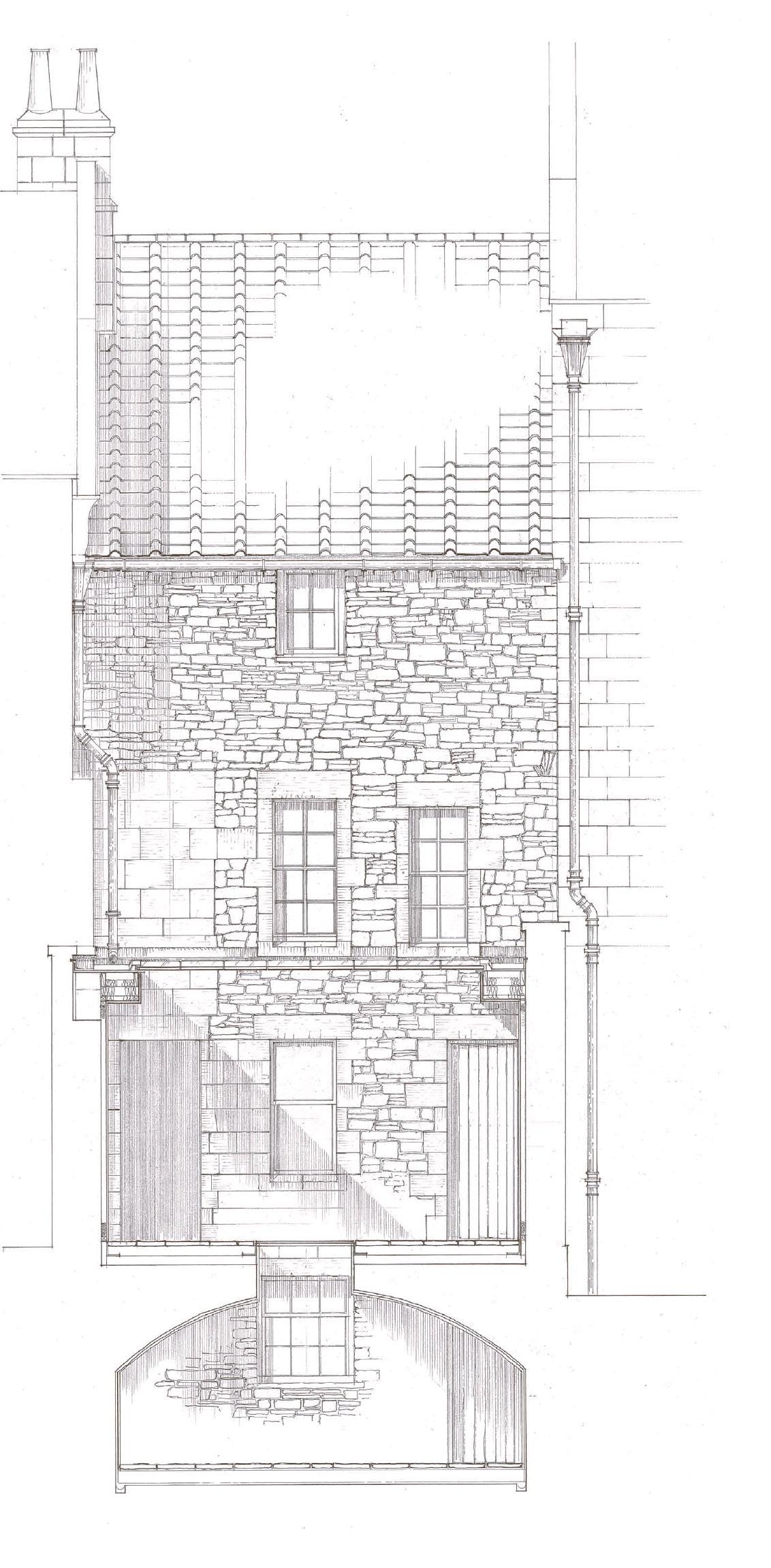

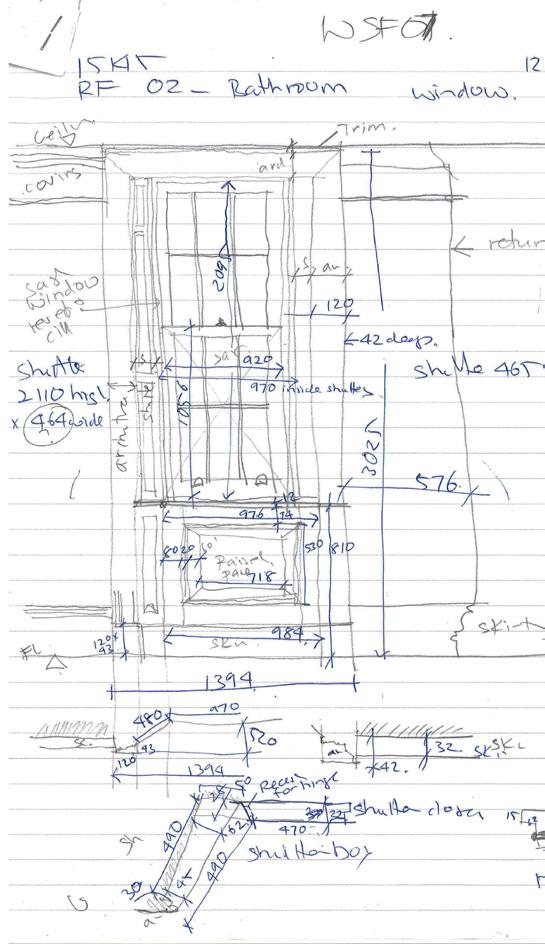

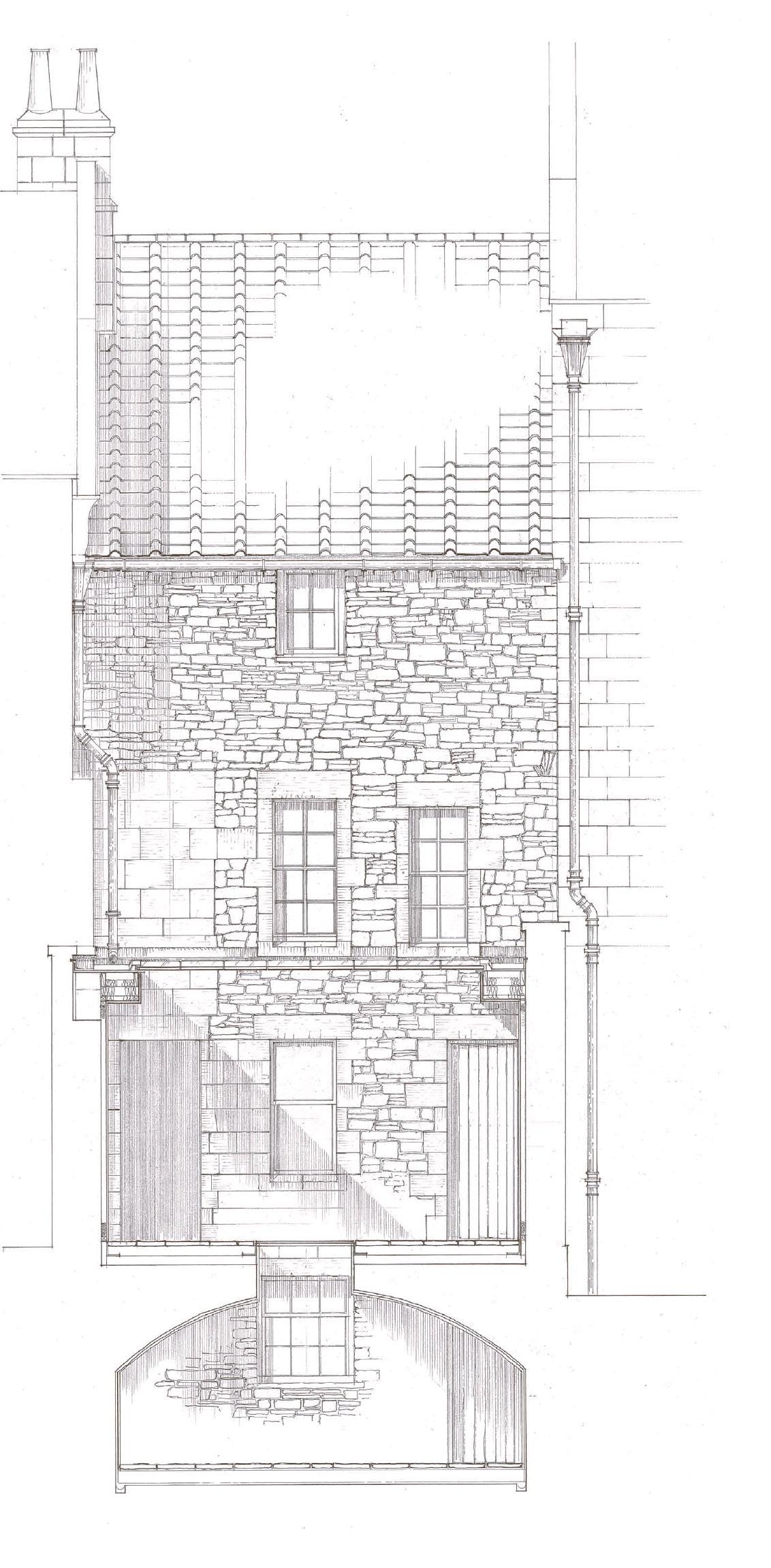

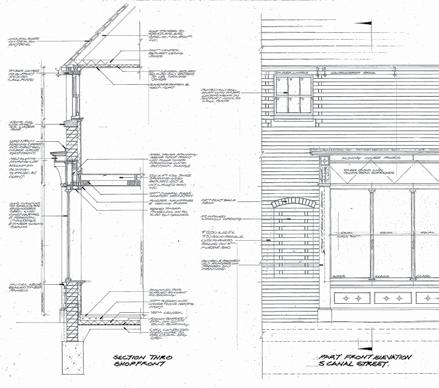

As Conservation Architects with decades of experience we are used to surveying buildings. Although increasingly, measured surveys are carried out by specialists there is still a place for measured surveys of critical areas that add a level of information over and above a basic survey. This information is frequently required to understand the detailed construction of a building and by Local Authority and Statutory Consultees. We increasingly use scanning or photometric technology but find that close inspection, and sometimes limited opening still play an important role in understanding a building.

In this large country house listed building, consent had been granted to raise the ceilings of a Victorian servant’s wing. Historic timbers, whilst structurally sound, were bowed following decades of historic movement.

A post strip out survey had not been undertaken when we were tasked with bringing forward this phase unexpectedly. A day with our high resolution digital camera and use of photogrammetry software enabled our architects to test with precision where the new plaster line should go, despite so much irregularity.

When buildings are proposed for statutory listing their owners have the opportunity to challenge the proposal with expert evidence. When this happened to the buyer of a 1960’s era furniture factory in Bath, they had no idea their ability to demolish it for a new supermarket was at risk of being frustrated by the prospect of listing. In fact, they had bought only half of the building in question. The case for listing rested on it being one of the earliest examples of the ‘space frame’ roof deck, a structural system enabling unusually wide roof spans.

Appointed to advise, our research in the RIBA and Institute of Civil Engineers archives in London showed that the building case for listing was sound. But this was a difficult structure to re-use, with a low floor to ceiling height. We used the evidence to show the planning case for the conversion to retail use was a near optimum use for such a challenging structure, leading to a successful re-use outcome despite retail planning policy concerns. In other listing reviews, clarification of the appropriate extent of a listing and the building’s legitimate curtilage have been important to their owner’s ability to dispose of them successfully.

TESTING OPTIONS FOR CHANGE

THE ROLE AND VALUE OF CONSULTATION

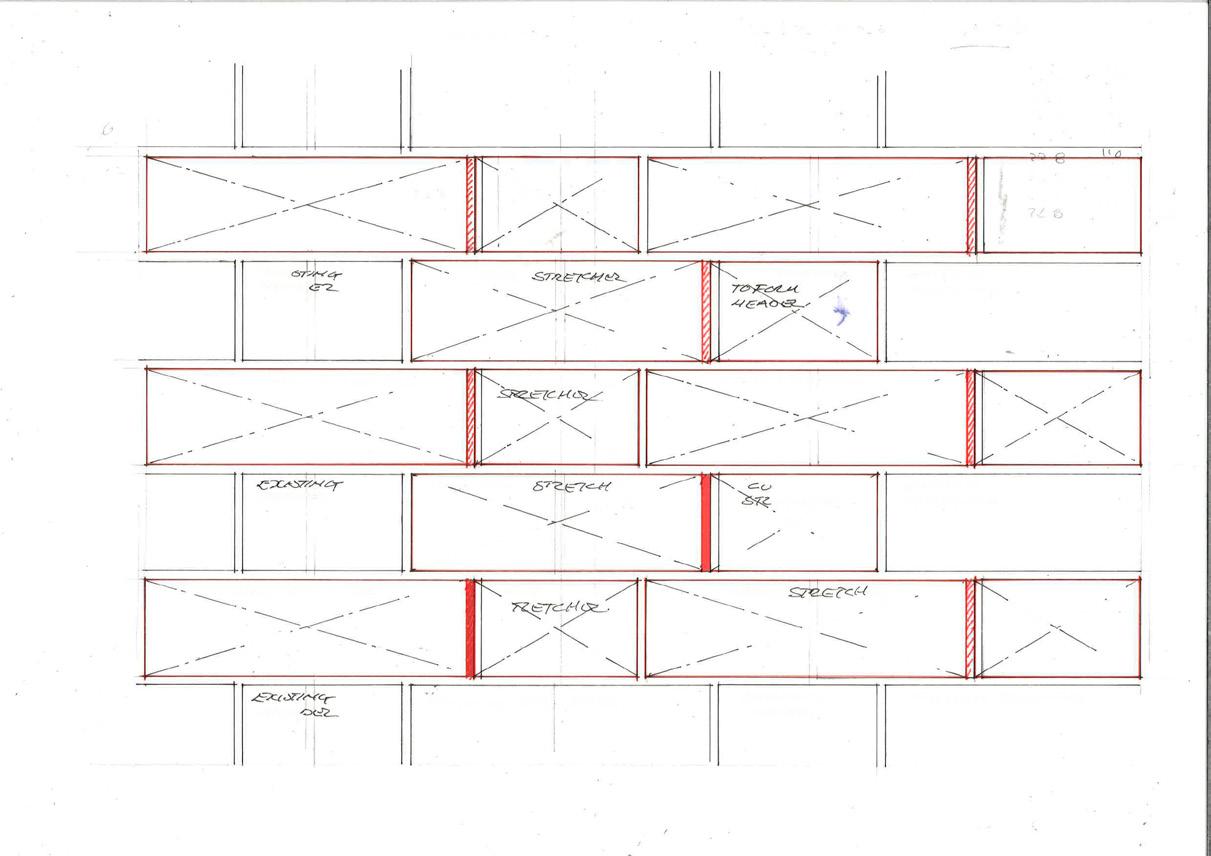

Local conservation and Historic England officers understandably seek confidence that the degree of change to a historic asset’s fabric or setting will be no more than essential if, in principle, they are minded to support it. So, alongside researched evidence of development history and value, they invariably want to weigh the options. Sometimes a change solution that is less ideal than an applicant wants is preferred because its degree of change or fabric loss will be less. Sometimes a proposal for change involving significant fabric loss is preferred because it will bring viable re-use to a long challenged asset.

This was so for this semi-circular structure built in 1820 as stabling for miniature ponies. Its low headroom and curved plan seriously limited other re-use options. The American Museum had secured new build planning permission for new facilities on their estate. But we realised by lowering the ground floor substantially, sufficient headroom could be created here for their new performance auditorium and avoid the need for building anything new. The LPA and HE much preferred this and endorsed major changes to the listed buildings’ external fabric to make this possible.

Listed buildings are seen by the planning system as community assets. Even though each has an owner, they are judged part of the common stock of humankind’s cultural history. So, prospects of their change or fabric loss can evoke strong feelings.

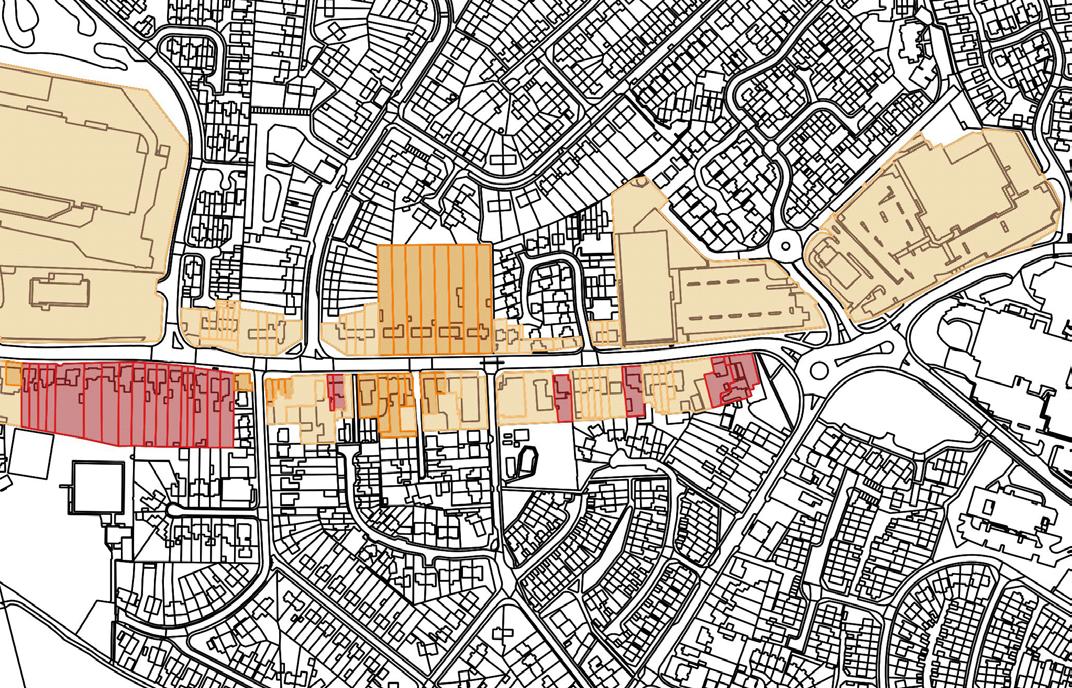

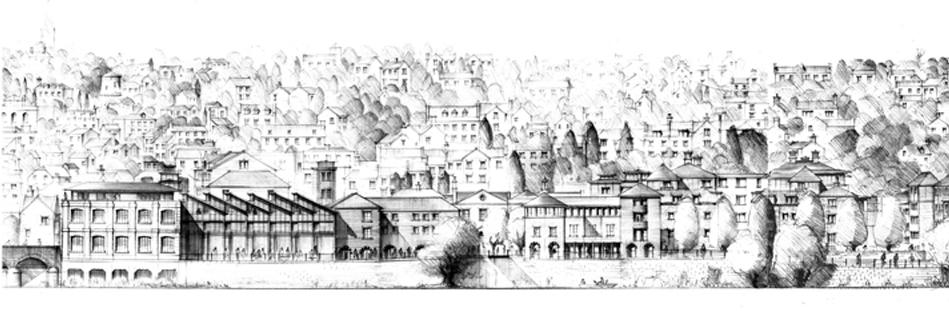

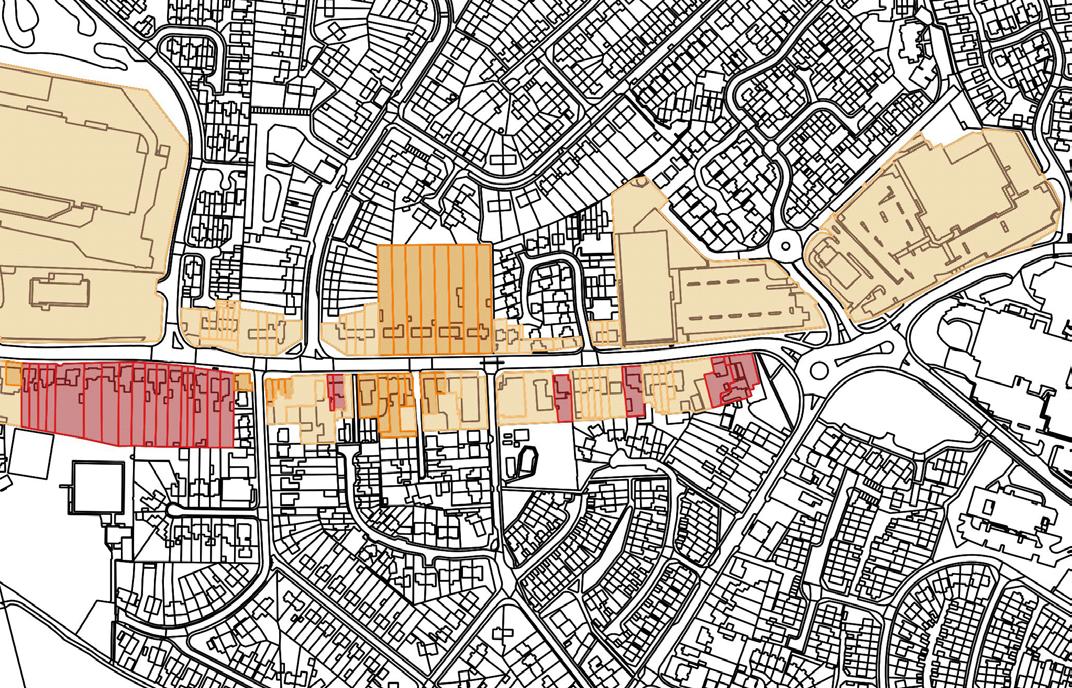

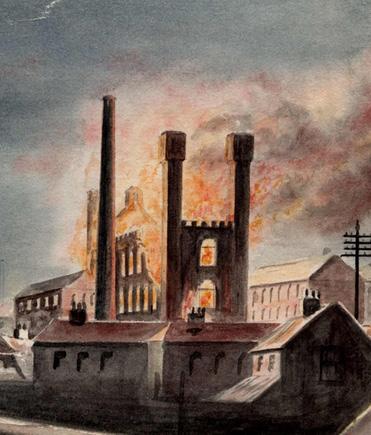

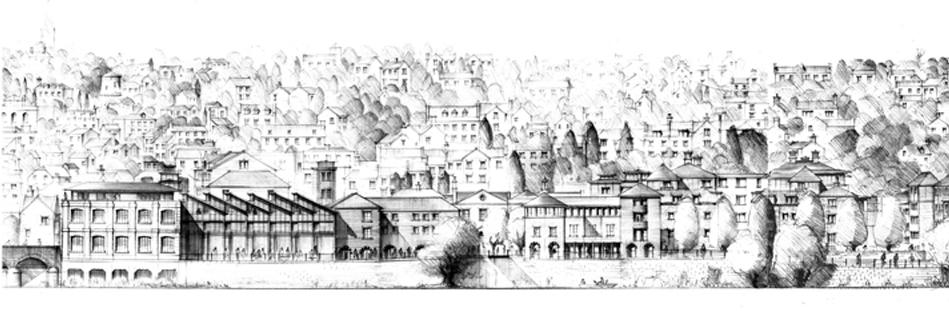

In Bradford on Avon, the large town centre riverside site of Kingston Mill had been derelict for 20 years. Amongst many late 20th century factory buildings lay many older ones of 18th to early 20th century date. There was a strong value and character case for building a scheme for the site that could keep and restore several of these, but not all. Through lengthy community consultation on the pros and cons of each candidate against its re-use challenges a consensus, on the best regeneration objective was forged.

BUILDING THE PLANNING CASE

DEGREES OF RISK

Planning and conservation officers evaluate a case for heritage asset change by testing it against adopted policies. So it is important any application is written to evidence the case clearly and systematically against these.

We were appointed to act for Bristol City Council in an appeal against refusal to allow conversion of the former Whiteladies Cinema to a gym. Case officers had recommended approval, but a wave of local objections had swayed the local planning committee to refuse the proposal.

Our case had several strands. We evidenced the rarity of the surviving structure. We provided evidence of the relative soundness of its condition, which was likely to remain stable for a long time until a more optimum solution emerged. We demonstrated lack of future reversibility if the appeal was allowed. We showed how detrimental changes proposed would be to public understanding of the building’s historic use. Crucially, we showed prospects were high that new patterns of cinema going evident elsewhere in the UK could rescue the building imminently. Our case won the day and within a short space of time a new cinema use has seen the building fully restored.

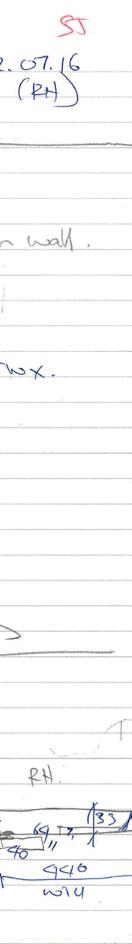

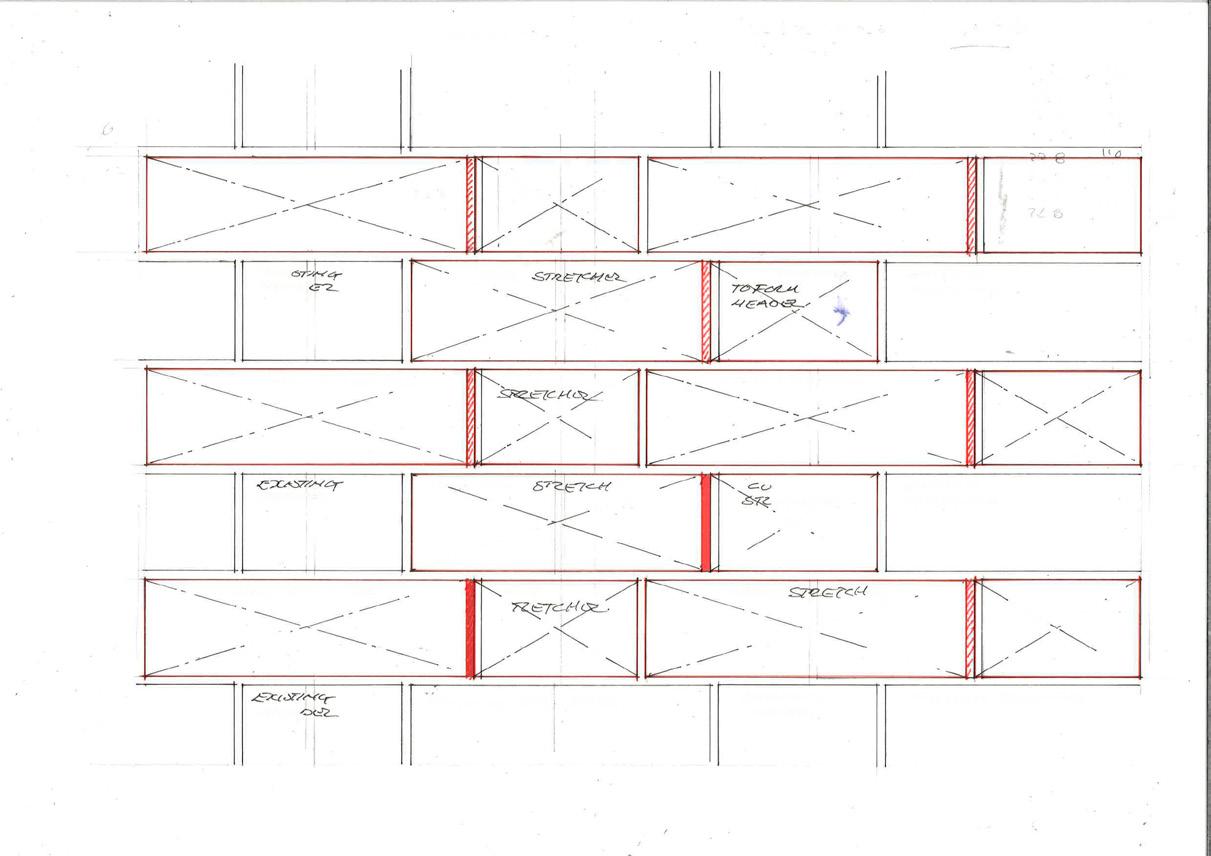

One thing conservation officers and Historic England are considering when applications are in front of them is whether (in carrying out the works proposed), there are risks of collateral damage beyond the works defined. If so, how the work is carried out matters as much as what is proposed and a Method of Works Statement is needed.

This was important to our achieving listed building consent for a proposal to acquire and re-use a popular village pub near Bath as a Crowdfunded Community project. The project would rely on volunteer labour and to win officers’ support needed particular guidelines and controls put in place because of this.

In our work advising Conwy County Borough Council on the demolition of Colwyn Bay’s late Victorian pier, the high risk of major asbestos pollution of the bay’s restored beach and evidence imminent progressive collapse led rapidly to an agreement to demolish, setting aside the oldest elements for possible future re-use.

Photogrammetry, photomontaging, 3D models and computer visualisation all bring added confidence to the assessments of change we make. Architects and urban designers do greatly value hand drawing. Time spent drawing on site builds depth of knowledge and understanding. Hand drawing of project proposals brings a necessary sensitivity to contextual design judgments and a romantic spirit that recognises how historic places speak to us

Investigative Tools, Recording and Presentational Methods

Heritage assets contain a wealth of information about their history of purpose and use, which is important to understand before works are done that could put this at risk. Sometimes this information is visible and needs interpreting. It may be hidden behind paint or plaster finishes. It may be comprehensible only through study of a building or town’s street plan, or in fragmentary evidence or remains deep in the ground. Often, large parts of an asset’s story, its value and significance may exist away from its site in archives.

To handle historic assets, buildings and sites well we need to know enough to advise building owners on the techniques and tools available to find and interpret this diversity of information. We deal with a wide range of specialists. Some are archival researchers, others wield specialist equipment able to uncover evidence not visible on the surface and often necessarily non-invasive.

To record the detail and condition of historic buildings and reveal archaeological evidence without

destroying it, drones and sonar imaging cameras are now familiar tools.

Historic assets are limited and a precious resource not replaceable if damaged or destroyed. So, before specifying change we have to be able to record what exists in considerable depth. The patina of age, of lichens grown over centuries or the surface evidence of structural decay deep inside timber or stone are important evidence. Whilst getting up to the more difficult to access parts of a building via physical survey remains important, being able to carry away from site the fruits of inspection matter even more. Now, using drones assembling multiple photographs and plotting them into a 3D Cloud Point Software tool, we can produce a virtual model of every surface of a historic building both inside and out. Each hinge, door knob or pane of glass can be available for inspection during specification from the office desk.

When we have such tools to record what exists we have a robust baseline from which to present, describe and

score proposals for change. We can use this to schedule repairs into the 3D model, to record the progress of a project programme, and the results. We can use such tools to educate others, inform our clients, or brief the workforce.

Such tools have added greatly to the confidence with which we undertake our work and how we communicate knowledge and requirements to others.

We often work closely with specialists and are used to engaging with these on a day-to-day basis.

Early in a project we carry out visual surveys to assess the condition of a property, the causes of decay and the repair requirements. We produce tabulated Schedules of Condition and Repair with an assessment of priorities that help clients and contractors in the early stages of planning and pricing maintenance. We often develop these in concert with feasibility study options for alterations to arrive at a planning strategy that has the best chance of securing the necessary permissions.

Technical Depth

Evaluating archaeological reports and scoping briefs.

Accessing research sources.

Scoping and evaluating building investigations and using noninvasive techniques.

Obtaining specialist analysis for damp, dendrology, surface finishes, historic mortar and plaster composition etc.

Sourcing replacement materials and craft skills.

Surveying, photographic and sonar surveys.

Building condition surveys and reports.

Surface removal and cleaning techniques for historic materials.

Installing services discretely into historic buildings.

Passive sustainability in historic buildings.

Heritage Planning Advocacy and Expert Witness

In the built environment, the value to the community of heritage asset classes such as listed buildings, scheduled ancient monuments or conservation areas and world heritage sites is protected by legislation. This provides for local planning authorities to develop specific planning policies for their districts and obliges historic asset owners to seek planning permission or listed building consent for works of alteration, some types of repair, conversion or new development likely to affect their significance or settings.

Local planning authorities employ specialist officers to give advice and administer applications. They do so also in consultation with the national advisory body, Historic England, operating through its regions. Specialist historic amenity advisory bodies exist who are often consulted for their particular knowledge and expertise in particular building eras and typologies.

Historic asset owners may want to embark on work which might be long lasting. So, building confidence that what they want to do will be positively received when applications are made is important. Our team is well experienced in this area and will advise on how best to approach officers for advice and to submit applications with good prospects of success, and how to take a project forward if challenges arise on the way.

We can explain what to do if your building is proposed for listing via a third party or if you are interested in having it listed yourself. There is a procedure to assess the prospects of an non-listed building becoming listed during your project period.

Historic asset owners may own property for which the necessary planning or listed building consents were not obtained and find themselves threatened with enforcement action to remediate the changes. We can advise in this area of concern too.

Local authority conservation officers have a lot of individual authority to determine what they consider harmful to heritage assets. Where applications are refused planning or listed building consent, a planning appeal allows the merits of a proposal to be examined independently, often with the benefit of more time for consideration and discussion. Our planning and architect teams are well used to preparing appeal evidence.

With larger planning applications, heritage is often only one of a number of issues under consideration. Putting the best presentation for a planning case sometimes needs input by a heritage expert. Our team have provided such specialist evidence acting for the building owner or the local planning authority.

1. Whiteladies Cinema, Bristol Bristol City Council

2. Clifton College, Bristol Bristol City Council

3. Hope House, Bath Acorn Property Group

4. Leybourne Grange, Maidstone NHS

5. Longfords Mill, Stroud Hartley Property Trust

6. Woolwich British Telecom

7. Victoria Pier, Colwyn Bay Conwy County Borough Council

1. Whiteladies Cinema, Bristol Bristol City Council

2. Clifton College, Bristol Bristol City Council

3. Hope House, Bath Acorn Property Group

4. Leybourne Grange, Maidstone NHS

5. Longfords Mill, Stroud Hartley Property Trust

6. Woolwich British Telecom

7. Victoria Pier, Colwyn Bay Conwy County Borough Council

4 5 6 1 2 3 7 8

8. Grand Parade, Bath Bath and North East Somerset Council

Regeneration, Spatio-Temporal Economic and Public Sector Challenges

Even where it is protected from detrimental physical change, the built environment is not static. The world continues to change around the buildings that survive from the past. Economies that produced the buildings from the past move on and new patterns of use are needed so they are maintained and continue to be valued for the contributions they bring.

So often the re-purposing of valued historical buildings and other assets becomes the vehicle through which economic, social and cultural reinvestment occurs. The memory of the past is carried forward to connect to the emerging future. But before this happens, the statutory planning process has to decide (often with the agency of Historic England) what of the recent past and today’s yesterday it is important to save and what to grant listed building, conservation area, or world heritage site status to. What to value as ‘significant’ is a particular consideration for conservation architects.

Our built environments are immensely varied; through the natural geography that has defined local construction materials and topography that defines built form and layout.

Listed buildings or valued areas came into existence in response to economic need and opportunity at the time. Such assets often pass into the ‘heritage estate’ when their founding pattern of use has passed away and new economic activity is needed to help keep them in good repair if they are to survive into the future.

For our team, developing an understanding of why, how, where, and when both negative and positive investment and economic, social and cultural change will happen is an area of study in itself. This is what we have come to describe as ‘spatio-temporal economic analysis’.

Using our unusually broad skillset of research geographers, planners, regeneration experts and urban designers we have devised analytical tools and presentation techniques to explore how physical, social, environmental and cultural change happens. We use tools of demographic travel to work and other socio-economic datasets along with many other factors.

We apply these tools to prospects of urban change on a city, town or urban scale. Once we know how and why previous investment change has happened, we often understand how to bring out or ‘rediscover’ valued heritage assets as the basis of longterm regeneration strategies. Such work is used to regenerate the narrative for local authority Core Strategies and new Local Plans. Forming a socio-economic understanding and using it with an historian’s eye has proved important to building sound urban masterplan briefs.

Building the regeneration economy of Bath’s river corridor

BANES River Corridor Economy Study

Bristol’s 20th century suburbia - a case for regeneration

South Gloucestershire Council Study

Building urban living in Frome. The Saxonvale neighbourhood masterplan for the climate change adjustment era

Acorn Property Group & Mendip District Council

Testing options for the future of Victoria Pier

Conwy County Borough Council

Discovering, Unlocking and Building Value in Heritage Assets

Throughout the built environment of our cities and towns, the physical condition and perceptions of value and pride in our heritage assets varies greatly. Often where buildings of character do survive after their founding economy has passed away, it has been their visual robustness, and their quality of craftsmanship, their uniqueness of purpose and place that has been the stimulus for new economic investment.

Sometimes, such change needs to be stimulated by a funding programme or development that creates an investment subsidy. Regeneration is a cyclical process and at various times, most parts of the urban estate needs this sort of reinvestment. Through our work over 30 years, we have discovered that heritage assets have the power to be the catalyst for positive change and reinvestment, even in the most unlikely of situations.

First, the asset’s latent value has to be found, understood and articulated. Then, a means has to be advised to unlock it, to allow this latent value to work alongside new change models. Then by creating a synergy of interests between the physical asset, new initiatives, impending demographic change, new economic needs and opportunities a mechanism of positive change can be devised, directed and monitored. So often this positive cycle of regenerative reinvestment then becomes self-fuelling.

1. Westley Richards, Birmingham Remodelling for new factory and workshops

2. Blists Hill, Ironbridge Gorge World Heritage Site Museums orientation centre

3. Victoria Pier, Colwyn Bay Advised Conwy County Borough Council on the future options of the Grade II listed Victoria Pier

4. Bradford on Avon, Wiltshire Redevelopment of historic town centre

5. American Museum, Claverton Manor 23 years of building social and cultural value

6. Combe Down Mines, Bath Design and planning advice

4 1

7. Pro Cathedral, Bristol Advice on conversion to residential uses

5 6 2 3 7

5 3 6 2 4 1

Our heritage clients

Acorn Property Group

American Museum in Britain

Bath and North East Somerset Council

Bath Society of Friends

Bloor Homes Ltd

BNP Paribas Real Estate UK

Bradford on Avon Town Council

Bristol Cathedral Choir School

Bristol City Council

British Telecom

Cheltenham Borough Homes

Cheltenham College

Conwy County Borough Council

Crest Nicholson South East Ltd

CS2 Limited

English Heritage

Gloucester County Council

Goodmans Restaurants Group

Hartlebury Castle Preservation Trust

Hartley Property Trust

James Purdey and Sons

Jane Austin Trust

Linden Homes

Museum of Bath at Work

National Trust

NHS

Ove Arup & Partners Ltd

Packhorse Community Pub Ltd

PCC St Michael’s Tidcombe

Pearson May & Co

Queens College, Taunton

S.P. Green & Co Ltd

South Gloucestershire Council

The Ironbridge Gorge Museum Trust

The Royal Photographic Society

Trowbridge Town Hall Trust

Turner & Townsend

Westley Richards & Co Ltd

Woodhouse and Law

YTL Filton

1. The Old Soapworks, Bristol Urban masterplanning study

2. Monkey Island Hotel, Bray Comprehensive refurbishment of a Grade I listed hotel

3. Lansdown Crescent, Bath Developed a tailored planning approach, allowing development of new dwellings

4. Herschel Place, Bath Extension of Georgian terrace

5. Saxonvale, Frome Regenerative masterplan for a large riverside site at the heart of Frome

6. Pantglas Hall, Carmarthenshire Informing the repairs and restoration of a listed ruin

Nash Partnership is a built environment, regeneration, planning and design consultancy, first established in 1988 in the West of England. Our professional services and advice skillset now embrace the discipline of research geography, regeneration strategy, heritage asset consultancy, planning, urban design and architecture. Through learning to combine these perspectives in our own team we are well equipped to work well with multi-headed corporate and public sector clients and project teams. Working together, our team aims to bring a comprehensive understanding to how our built environments have become the way they are and how effective strategy can be built to improve them in the future.

Bath Office: 23a Sydney Buildings, Bath BA2 6BZ

Phone: 01225 442424

Bristol Office: Generator Building, Counterslip, Bristol, BS1 6BX

Phone: 0117 332 7560

Website: www.nashpartnership.com

Email: mail@nashpartnership.com

Twitter: @nashPLLP

Leybourne Grange, Kent Masterplan for wholesale redevelopment of a large country estate around historic assets after end of hospital use

Leybourne Grange, Kent Masterplan for wholesale redevelopment of a large country estate around historic assets after end of hospital use

1. Whiteladies Cinema, Bristol Bristol City Council

2. Clifton College, Bristol Bristol City Council

3. Hope House, Bath Acorn Property Group

4. Leybourne Grange, Maidstone NHS

5. Longfords Mill, Stroud Hartley Property Trust

6. Woolwich British Telecom

7. Victoria Pier, Colwyn Bay Conwy County Borough Council

1. Whiteladies Cinema, Bristol Bristol City Council

2. Clifton College, Bristol Bristol City Council

3. Hope House, Bath Acorn Property Group

4. Leybourne Grange, Maidstone NHS

5. Longfords Mill, Stroud Hartley Property Trust

6. Woolwich British Telecom

7. Victoria Pier, Colwyn Bay Conwy County Borough Council