Enlightened. Glimpses of a Norwegian Cultural History

ENGLISH

The present is built on what has gone before. This exhibition brings a selection of unique, spectacular and significant pieces of Norwegian cultural history out from the shadows of the archives and into the spotlight. These items represent particular moments in our shared history, telling of great breakthroughs, creative masterpieces and crucial events that have shaped our capacity for expression and our nation.

The National Library of Norway collection includes a large proportion of the material published from the 12th century up until the present day. The collection is our common collective memory, where we find stories of who we are and where we come from. Enlightened is one such story.

17 12 24 3 27 6 4 23 2 15 9 25 7 28 16 1 11 5 29 22 13 26 30 14 18 8 19 21 20 10

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 15 14 13 12 Exhibition map The Kvikne Psalter 7 King Magnus VI’s Law of the Land in the Codex Hardenbergianus 8 Biblia (the ‘Reformation Bible’) 9 ‘Letter from heaven’ 10 Norske Intelligenz-Seddeler 12 Dorothe Engelbretsdatter: Siælens Sang-Offer 14 Constitution of the Kingdom of Norway 16 Draumkvedet 18 Georg Ossian Sars: Scientific drawings 20 Henrik Ibsen: Peer Gynt 24 A Doll´s House 26 Hedda Gabler 28 Due to conservational considerations the Ibsen material on display will alternate. Peter Christen Asbjørnsen and Jørgen Moe: Storybook for Children 30 Ivar Aasen: Norwegian Dictionary with Danish Definitions 32 Edvard Grieg: Piano concerto in A minor, op. 16 34 Gina Krog (ed.): Nylænde 36 Edvard Munch: Self-Portrait with Skeleton Arm 38

18 19 17 16 24 20 28 25 21 29 27 26 22 30 23 Snorre Sturlason: Sagas of the Kings 39 Hulda Garborg: Housekeeping 40 Yes and No ballots from the referendum on the monarchy 42 Dæmonen, censored film clips 44 ‘The South Pole Letter’ 46 The Workers’ Encyclopedia 48 Radio news, 9 April 1940, and news broadcast from London, 7 May 1945, NRK 49 Georg W. Fossum: Deportation of Norwegian Jews, 35 mm 50 Official opening of the Ekofisk field, NRK Dagsrevyen 51 Arvid Sveen: ‘Long-term conservation of the Alta-Kautokeino river!’ 52 Darkthrone: A Blaze in the Northern Sky 54 www.oslonett.no 56 SKAM, script 58 Karpe Diem: Heisann Montebello 60 Mass political and religious movements, pamphlets 62

A psalter is a book or manuscript mainly containing The Book of Psalms from the Bible. These 150 so-called Psalms of David constituted the basis for eight significant daily readings organised by days of the week and according to a set pattern. This made the week into a Christian cycle, a unit of time defined by faith and prayer. Psalters were one of the commonest types of book in medieval times.

This psalter, dating from the second half of the 12th century, is believed to be the oldest book produced in Norway that has survived intact. Originally, it probably contained all the psalms. Some pages were lost during the Middle Ages, but were replaced in the 15th century with new pages bearing the same content.

The Kvikne Psalter is typical of its time and place. It is inscribed by hand on parchment, in Latin. The script is similar to that found in English psalters produced by professional scribes, but the adornments are few and simple. The Norwegian scribes were not such accomplished calligraphers as their English counterparts, and this was probably the first time they had produced a book.

The fragmented contents are still held in place by solid wooden binders thought to date from the first half of the 13th century. The text carved on the back, combining runes and Latin letters, declare: “Kvikne church owns me.”

7 1

The Kvikne Psalter c. 1150–1200

King Magnus VI’s Law of the Land in the Codex Hardenbergianus

Mid 14th century

The landslov, or Law of the Land, promulgated in 1274 by King Magnus VI, is a milestone in European legal history. As only the third nationwide legal code to be introduced in Europe, it remained effective until superseded in 1687 by Christian V’s Laws of Norway. The landslov transformed Norwegian society, established legislation as an instrument of government, granted rights to the weakest in society, and laid the foundations of the Norwegian state.

Of the 39 intact manuscripts and over 50 manuscript fragments that have survived, the Codex Hardenbergianus is the most beautiful. The manuscript, written in Old West Norse in Bergen in the mid 14th century, contains 10 decorated and illustrated letters of the alphabet (known as illuminations) that convey the essence of the text.

The Codex Hardenbergianus is a bound volume containing several legal texts, the biggest and most important of which is the landslov. The volume also contains legal amendments and new laws that were later introduced to supplement or supersede parts of the landslov, and Archbishop Jon Raude’s ecclesiastical laws.

The most significant legacy of the landslov from 1274 is the idea that we should follow a set of accepted laws, rather than allowing power to be the determining factor. Thanks to our legal tradition stretching back to the landslov, Norwegians today associate the word ‘law’ not with repression and abuse of power, but with rights and freedom.

Owner: The Royal Library, Denmark.

8 2

The complete Holy Scriptures, translated into Danish 1550

The religious upheavals started by Martin Luther in 1517 had significant knock-on effects for culture. The Reformation brought a strengthening of individual faith and a weakening of the church’s role as a mediator and interpreter. Instead, the word of God – the Bible – became the focus of religious life. This meant that the Bible had to be translated from Latin to the vernacular, the language spoken by the people. Following the invention of the printing press in Europe in the mid 15th century, it was now possible to produce books faster, at lower cost and in larger numbers.

The Bible on display here, known as the ‘Reformation Bible’, is the first complete Bible in Danish. It is printed in 1550 and largely based on Luther’s German translation of the Bible from 1545. The typefaces and illustrations, however, were the very same that were used for printing a Low German Bible edition in 1534. The ‘Reformation Bible’ contains 85 woodcut illustrations in total.

The Reformation spelt the end of Norway’s political independence. The country was placed under the Danish crown, and the king was made head of the church. A portrait of Christian III is one of the first things encountered by readers of this Danish bible. The king’s gaze is directed heavenwards, and in his ungloved hand he is holding a scroll containing the word of God. The coat of arms on the second page symbolises his earthly power.

Printer: Ludowich Dietz, Copenhagen.

9 3 Biblia.

A ‘letter from heaven’ was a chain letter, asking the recipient to copy it out and send it on. The letter displayed here is a handwritten copy. According to the letter, the original was written by “the Lord God Himself” and sent via an angel to Constantinople (presentday Istanbul), where it was said to have hung in the air in golden letters. Anyone who copied out the letter and sent it to others would be forgiven all their sins. Those who didn’t believe it and didn’t copy it would die, and their children would “suffer a wicked death”. When Judgement Day came, anyone who had the letter in their home would be spared all torments. The letter earnestly implores the reader to live according to God’s commandments and the words of Jesus, and to attend church on Sundays. It is signed “I, the true Jesus Christ”.

Although few letters of this kind have survived, we know that the ‘letter from heaven’ was a popular genre in post-Reformation Europe, where the church no longer offered confession and forgiveness.

The text of such letters remained remarkably constant throughout the 18th and 19th centuries. The letters were copied by hand, but printed versions were also in circulation, often beautifully decorated and coloured. These one-page letters were easily carried around and sold. Printers made good money printing them in large runs, as many people were willing to buy salvation and happiness for a shilling or two.

10 4

‘Letter from heaven’, front Dated 1604

‘Letter from heaven’, back

Dated 1604

This ‘letter from heaven’ is dated 1604. But the paper it is written on bears a watermark showing the coat of arms of the city of Amsterdam, which proves it could not have been written before 1675. We do not know why the letter was backdated.

The fold lines show that the letter was folded in five, probably so the owner could carry it around as a lucky charm. This may have been a frequent occurrence, as the folds are worn, and holes have formed where they intersect. The parts that faced outwards when the letter was folded up are darker. This suggests that the letter was in use, carried in a pocket or next to the skin, and was read or shown off repeatedly.

11

4

Norske IntelligenzSeddeler was Norway’s earliest newspaper. This first issue was published in Christiania in May 1763. The publisher and editor was Samuel Conrad Schwach, a Prussian-born printer educated in Copenhagen.

In Christiania, Schwach had published periodicals of various kinds before launching the newspaper. It was not an easy process. There was heavy censorship, and the authorities only issued licences to publish newspapers in Copenhagen, where they could keep a close eye on them. Schwach got round this in part by limiting the content to advertisements, business news and religious reflections. As was typical in those days, he also benefited from knowing the right people: in this case Nicolai Feddersen, a state councillor and former chief magistrate of Christiania. It was in Feddersen’s interest to have a hold over Schwach, since he owned shares in the paper mill that made good money from supplying the newspaper.

Over time, Norske IntelligenzSeddeler was able to broaden its content, but it was not able to include real political stories until 1814, when press freedom was enshrined in the new Norwegian constitution. The newspaper remained in circulation until 1920, when it was incorporated into Verdens Gang.

12 5 Norske Intelligenz-Seddeler, No. 1, pages 1 and 4, newspaper 1763

Published by Samuel Conrad Schwach. The pocket to the left of the display contains a transcription.

This first issue of Norske IntelligenzSeddeler contains little in the way of what we would now call journalism. An introductory verse greets the reader, emphasising that this is a Norwegian publication: “This paper carries Norwegian reporting of one thing and another that might be of value.” In this way, it hints at a distinctly Norwegian perspective, while remaining ultracautious in expressing its patriotism. The rest of the content consists of simple announcements of ship arrivals and departures, items for sale, births, marriages and deaths, and seizures of stolen goods – plus an article on how to store lemons to keep them fresh over the winter in Norway.

Perhaps of most interest to the modern reader is a short, moralistic reflection on how intelligent people may be more inclined to criticise the mistakes and shortcomings of others than to correct their own. We no longer know who this barb was aimed at in 1763, but the sentiments are no less relevant today.

The original newspaper was printed in Fraktur, or Gothic type, which to modern eyes can be hard to decipher. The pocket to the left of the display contains a transcription.

13 5 Norske Intelligenz-Seddeler, No. 1, pages 2 and 3, newspaper 1763

Dorothe Engelbretsdatter: Siælens Sang-Offer, hymn book 1685

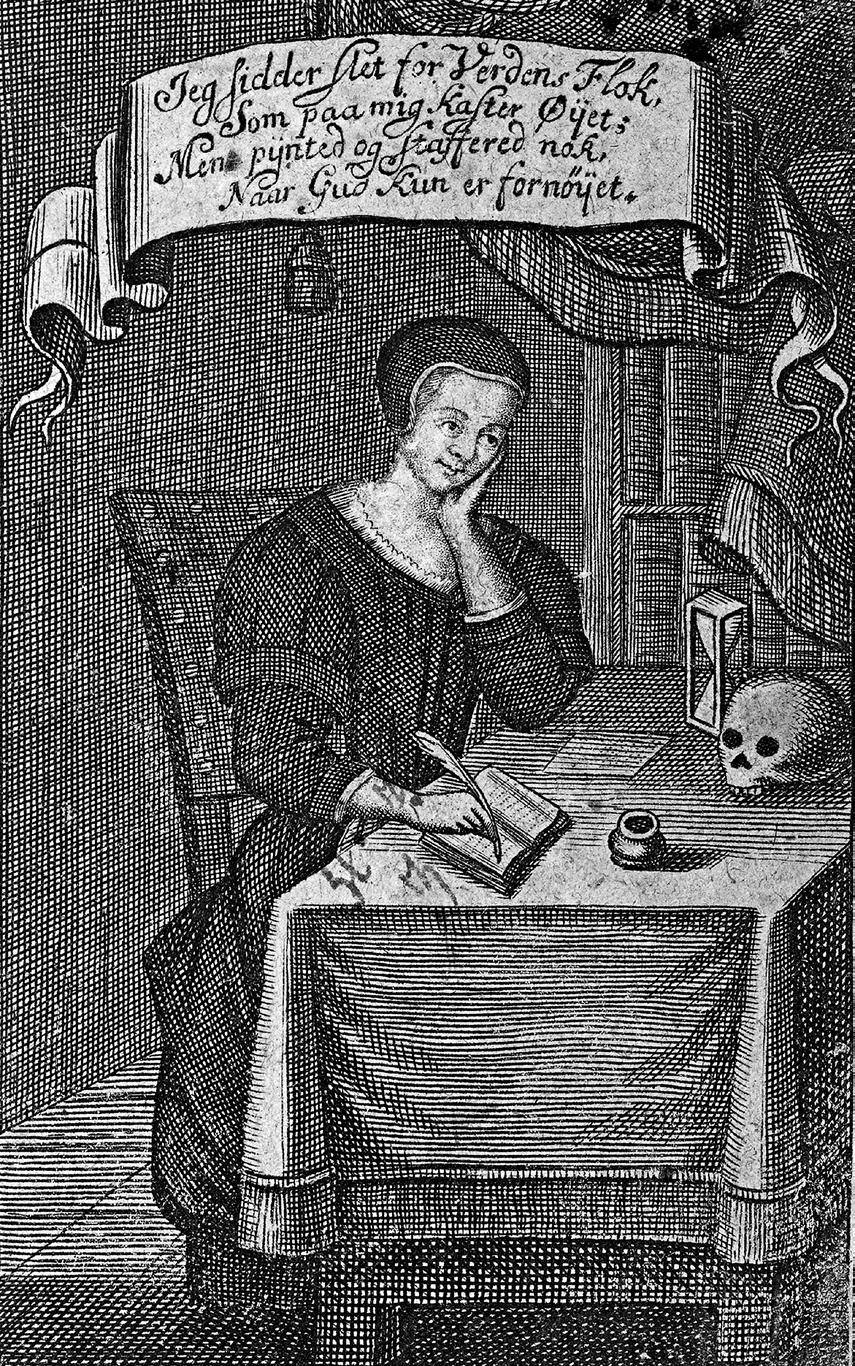

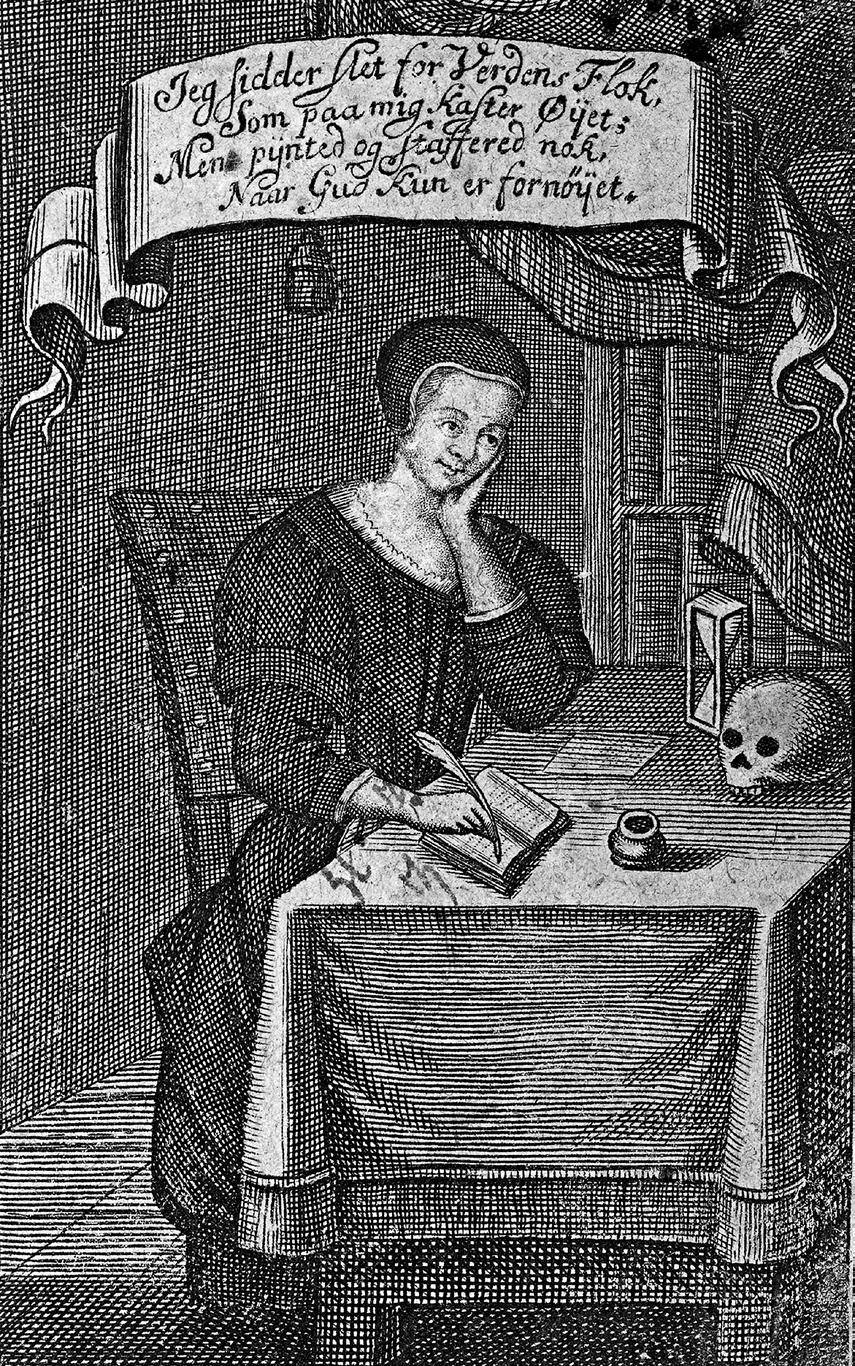

Dorothe Engelbretsdatter, who wrote the words to hymns, was the first professional author in Norway under Danish rule. Her first book, Siælens SangOffer (‘Song Offerings of the Soul’), was published in Christiania in 1678. No first editions have survived, but no fewer than seven editions were published during Engelbretsdatter’s lifetime alone. Thanks to her direct, easily sung language, she became one of the 17th century’s most popular authors.

Several of Engelbretsdatter’s books featured a detailed illustration of the author as a frontispiece on the page facing the title page. The portrait in this edition of Siælens Sang Offer , dating from 1685, shows a middle-aged woman writing. On the desk in front of her are a skull and an hourglass: common baroqueera motifs symbolising the transient nature of life. In this portrait, the motifs also allude to the profound personal experiences of Engelbretsdatter. Seven of her nine children had died in infancy. If life had taught her anything, it was that death awaits us all. This is a recurring theme in several of the book’s hymns.

‘Evening Hymn’, which is still included in the current (2013) hymnal used by the Church of Norway, refers to the hourglass running out.

Published by Christian Geersøn, Copenhagen.

6

14

The Norwegian constitution of 1814 placed legislative power in the hands of parliament, the Storting, and limited the powers of the monarchy. Representatives were to be chosen by an electorate consisting of male citizens over the age of 25 who owned a certain amount of property. Although this covered only 40–45% of Norwegian men – women’s suffrage was not yet on the agenda – this was a radical measure by the European standards of the time. The constitution was not only liberal in nature, but also guaranteed Norway a high degree of independence in its union with Sweden. It therefore became an important symbol of Norwegian national solidarity.

In the 1820s, printers began producing the constitution in poster form, and these political icons became popular wall art, usually mounted and framed. This 1836 version is especially lavishly decorated. The illustrations depict Eidsvoll manor, where the constitution was drawn up over six weeks in the spring of 1814, and some of the representatives who attended that assembly or the first extraordinary session of the Storting in the autumn of that year, when the union with Sweden was agreed. Although dated 4 November, the constitution contains only minor changes from the version adopted on 17 May. At the bottom are the signatures of the 79 members of the Storting.

Lithograph: J.C. Walter. Publisher: Prahl.

16 7

Constitution of the Kingdom of Norway, poster 1836

Not everyone felt included in the Norwegian political community. Established by labour activist Marcus Thrane in 1849, ArbeiderForeningernes Blad was the first newspaper in Norway to campaign for workers’ rights. Thrane, a bold and tenacious advocate of social reforms and extending the franchise, led what became known as the ‘Thrane Movement’ – Norway’s first mass political movement. In 1850 he petitioned the king with a series of demands, including universal suffrage. Although the Norwegian constitution was liberal by the standards of the time, there were limits on the freedom of expression, especially when it was used to mobilise the working class – and so Thrane was sentenced to seven years in prison.

On 4 June 1853, Arbeider-Foreningernes Blad devoted its front page to proposed constitutional amendments that had been drawn up by Ludvig Kristensen Daa, a historian and politician. The proposed changes all related to extending the franchise.

17 7 Arbeider-Foreningernes Blad, newspaper 1853

8 Draumkvedet as sung by Maren Ramskeid, manuscript

c. 1840–1850

The 19th-century collectors of folk tales, songs, tunes, dialects and artefacts were driven by the idea that these were all expressions of a deep-rooted popular culture – the ancient, fundamentally stable culture of a nation. The collectors’ work was therefore also a search for a shared national myth.

In Norway, this attitude to culture was widely embraced. Famous collectors included Asbjørnsen and Moe, Ivar Aasen, Ludvig Mathias Lindeman – and Magnus Brostrup Landstad, a priest and hymn writer. At some point in the 1840s, he wrote down the words of Draumkvedet (‘The Dream Ballad’) while Maren Ramskeid, a servant girl from Telemark, sang the ballad to him. The version by Ramskeid and Landstad is the most complete one known to us, and at the time it was used as a basis for attempts to reconstruct the original.

Draumkvedet describes a vision so comprehensive that it invites comparisons with Dante’s Divine Comedy. Contemporary experts are unsure as to the ballad’s age and whether the many different transcriptions can all be considered parts of the same ballad.

Landstad’s hastily written manuscript is full of corrections and additions – a striking contrast to the illustrated book edition by Gerhard Munthe in the drawer below.

1 Agnes Buen Garnås: Draumkvedet, 1984

Recording published by Kirkelig Kulturverksted | 2:24 (excerpt)

2 Arne Nordheim: Draumkvedet, with the Norwegian Radio Orchestra, Ingar Bergby (conductor), Grex Vocalis, 2006

Recording published by Simax Classics | 4:27 (excerpt)

18

8 Moltke Moe (ed.) and Gerhard Munthe (ill.): Draumkvæde. A Medieval Poem

1904

This beautifully produced edition of Draumkvæde (‘Dream Ballad’) features illustrations and artwork by Gerhard Munthe. Even the lettering is hand-drawn. As well as the ballad, this edition includes a few additional details. It mentions briefly that the text was edited by Moltke Moe, “a professor of the Norwegian vernacular committed to promoting the Norwegian folk tradition” – or what we would nowadays call a folklorist. He held Scandinavia’s first professorship in folklore studies, which was indicative of a transition from a romantic to an academic approach to the subject.

Moe was commissioned not only to edit the text, but also to produce a scholarly commentary. This was a complex task, and one that Moe never completed – much to the frustration of Munthe and the publishers, whose first release this was. For a long time they hoped to publish a supplement containing Moe’s commentary, but this never happened. Munthe’s book thus became a one-of-a-kind literary treasure, modern in style but lacking the intended academic dimension.

Published by Forening for Norsk Bogkunst (Norwegian Book Art Association), Kristiania.

19

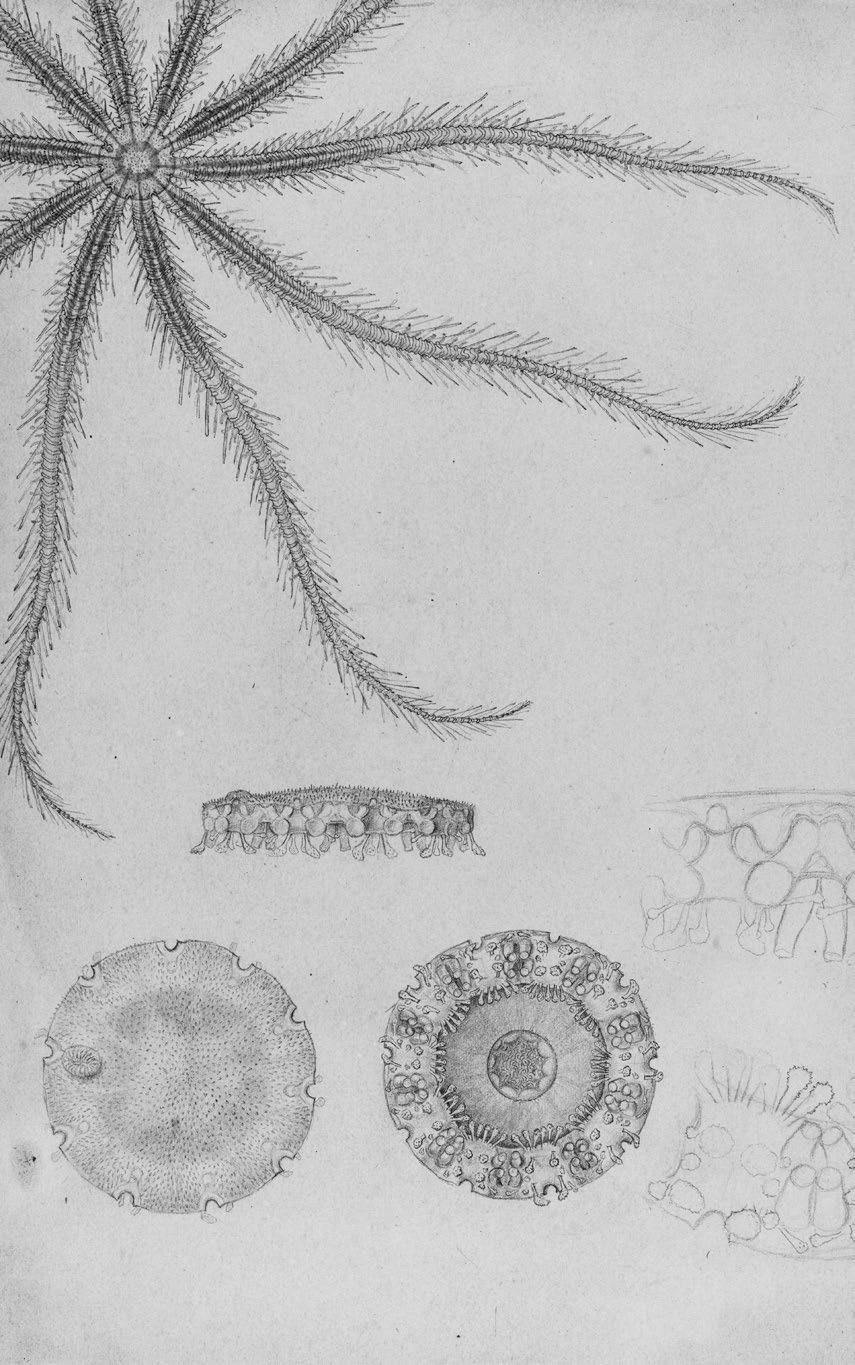

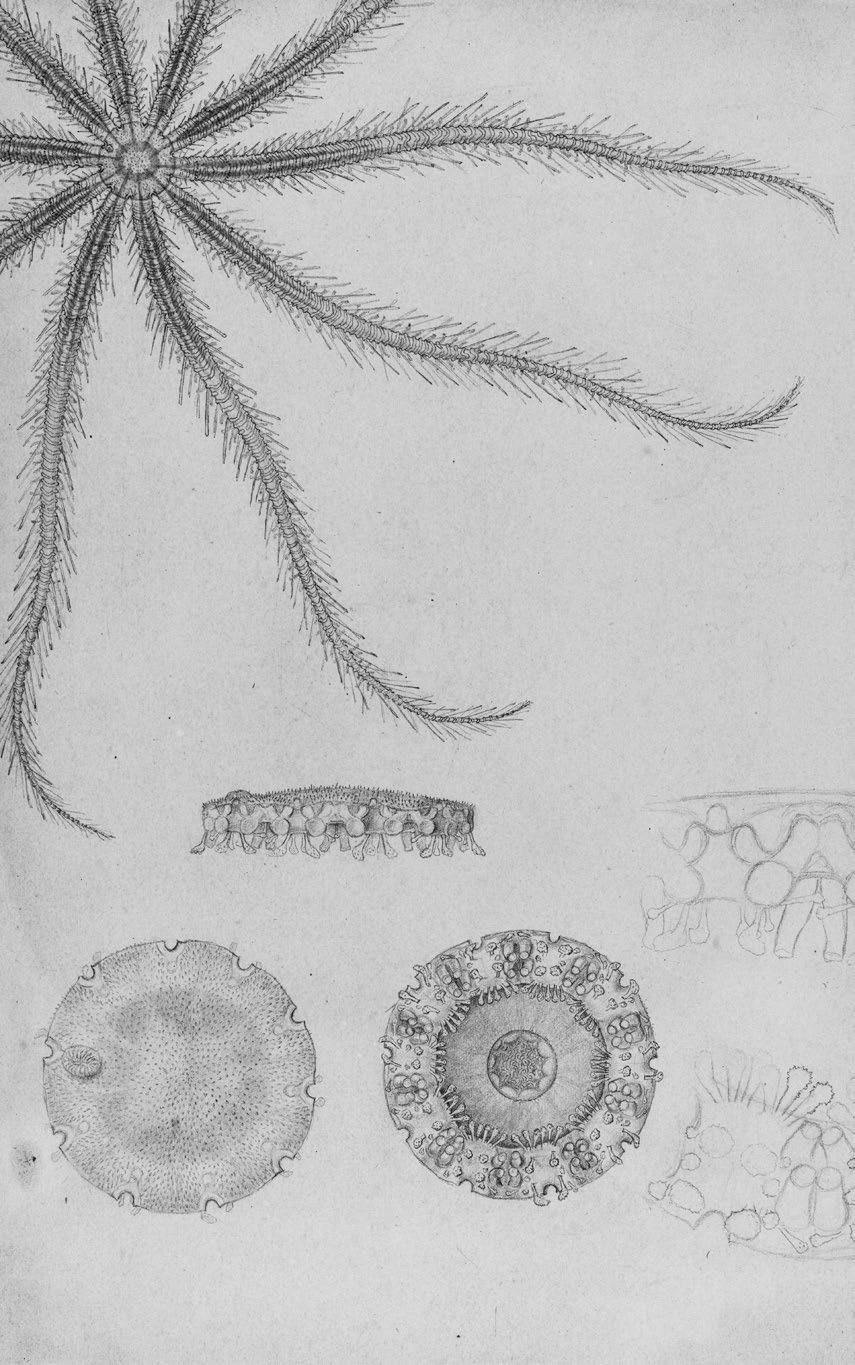

Georg Ossian Sars: Scientific drawings of starfish, cod, crustaceans and blue whale

c. 1860–1890

Georg Ossian Sars was Norway’s leading zoologist in the latter half of the 19th century and is still one of the most frequently cited Norwegian scholars of natural history. As a young man, he spent much of his time at sea, being paid by the government to help develop a scientific basis for Norwegian fisheries and later the whaling industry. Among his discoveries was the fact that cod roe floats on the surface rather than sinking, and in 1865 he succeeded in artificially fertilising the roe. After becoming a professor of zoology in 1874, Sars published many scientific papers, especially on crustaceans. The material on display here shows his exceptional talent as a scientific illustrator.

Sars was one of a small group of people who dominated Norwegian public life on both the scientific and the artistic front. His brother Ernst was the great Norwegian historian of the day. One of his sisters, Mally, was married to the composer and conductor Thorvald Lammers. Another sister, Eva, studied with Lammers and was a celebrated romance singer when she met and married Fridtjof Nansen, who had also started out as a zoologist – and illustrator. Georg Ossian Sars himself, besides being a prominent scientist and illustrator, was also a decent violinist. His works exemplify the cross-pollination that occurred between art and science.

9

20

21

Although he could not rival the scientific achievements of Georg Ossian Sars, the folklore collector Peter Christen Asbjørnsen was also a zoologist and was among the first to present Darwin’s theory of evolution to Norwegian audiences. In 1853 he discovered a hitherto unknown species of starfish in the Hardangerfjord at the remarkably great depth of 380 metres. It was not previously known that life existed at such depths. He named it Brisinga endecacnemos, after Brisingamen, the necklace of the Norse goddess Freya.

Sixteen years after Asbjørnsen, Sars discovered another starfish species, Brisinga coronata, at depths of up to 600 metres off the Lofoten islands. Sars described his discovery in an article written in English and published in 1875. He sent a copy to Charles Darwin, who replied with a friendly and appreciative letter in April 1877:

Dear Sir,

Allow me to thank you much for your kindness in having sent me your beautiful memoir on Brisinga. It contains discussions on several subjects about which I feel much interest. I congratulate you on your discovery of the new proofs of Autography which promises to be of much service to those who like yourself are good draughtsmen.

With the most sincere admiration for your varied works in Science, I remain, dear Sir

Yours very faithfully

Charles Darwin

23

9 Letter from Charles Darwin to Georg Ossian Sars 1877

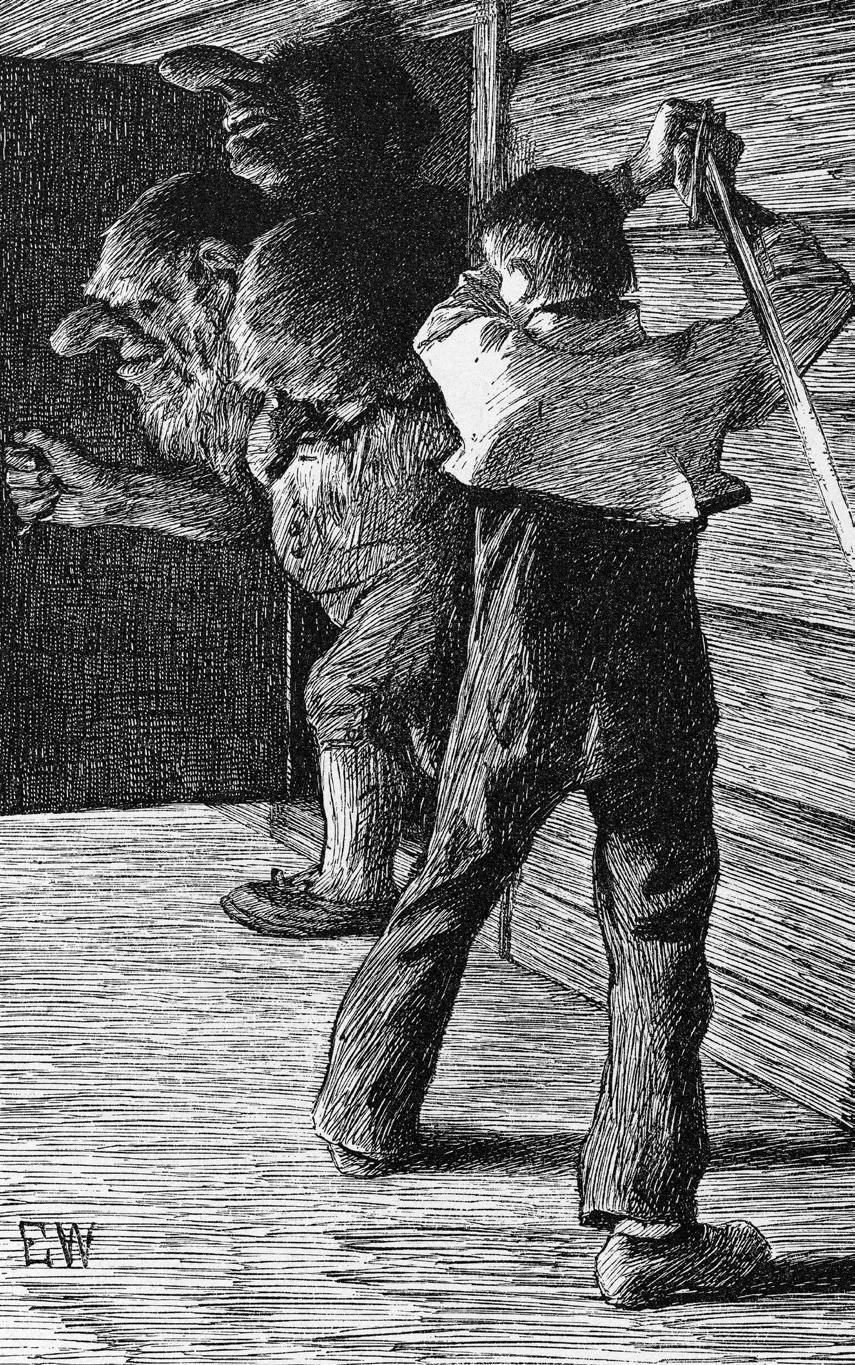

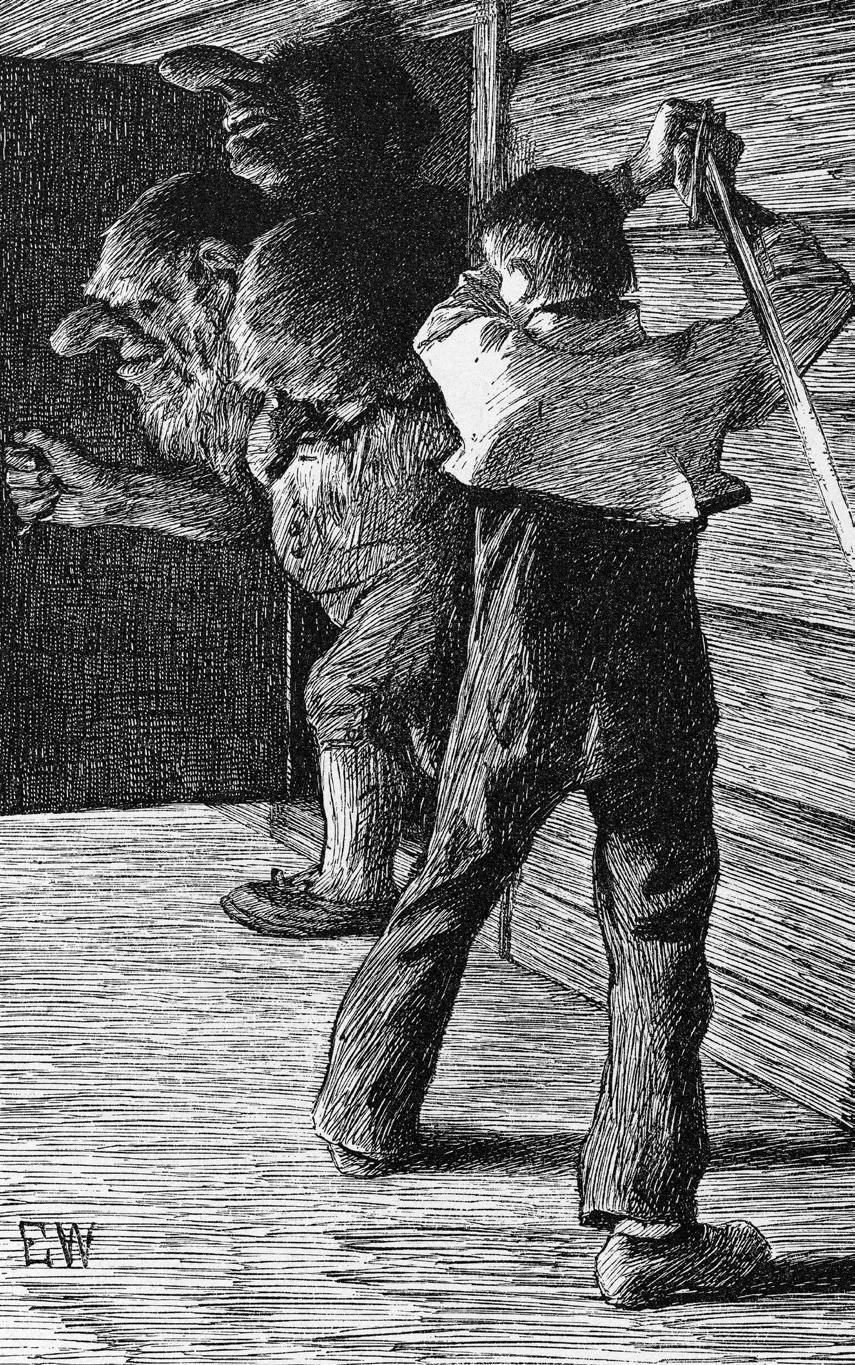

Henrik Ibsen: Peer Gynt. A dramatic poem, first edition, and second edition with handwritten amendments

1867

Henrik Ibsen’s Peer Gynt is considered one of the great works of Norwegian literature, on account of both the quality of its language and the complex character study of Peer Gynt – which many people have also described as a study of the quintessential Norwegian character. Ibsen started work on the play in Rome in 1867 and wrote most of it on the island of Ischia in the Bay of Naples. The first performance took place almost a decade later, in 1876, at the Christiania Theater, with a musical score by Edvard Grieg.

Ibsen drew inspiration for the character of Peer Gynt from P.C. Asbjørnsen’s Norske HuldreEventyr og Folkesagn, a collection of legends and folk tales published in 1845, in which Per Gynt is described as “a huntsman in Kvam in the olden days”. He is said to have outwitted mountain trolls and “the Great Boyg of Etnedal” – and he had a reputation for telling tall tales.

Ibsen’s Peer Gynt is likewise someone adept at inventing stories and escaping reality. In the play’s opening line Aase, Peer’s mother, exclaims: “You’re telling lies, Peer!” He is “himself enough”, but like an onion has no innermost core. Wherever he travels, the Boyg is lurking, enticing him to “go round about”.

First edition published by Den Gyldendalske Boghandel (F. Hegel), Copenhagen.

Second edition (1867) with amendments, mainly linguistic modernisation, by Henrik Ibsen and others for the third edition (1874).

10

24

Peer Gynt, TV adaptation, NRK 1993

When NRK began regular nationwide television broadcasts in 1960, the newly established Fjernsynsteatret (TV drama) unit played an important role in connecting Norwegians to their culture. Now, classic and modern dramas could reach audiences on a hitherto unimaginable scale. The plays of Henrik Ibsen, especially his contemporary social dramas, came as a revelation to many Norwegians who had previously known Ibsen only from reading or by reputation. In 1990, Fjernsynsteatret ceased operations as a theatre company with a permanent ensemble and was replaced by a new programme unit, NRK Drama, which since then has only rarely produced TV adaptations of stage plays.

The 1993 production of Peer Gynt, with Paul-Ottar Haga in the title role, was an exception – a production that embodied the values of the former Fjernsynsteatret but also took advantage of the new, multifaceted possibilities for visual expression made possible by advances in broadcasting technology. This was particularly apparent in the Hall of the Mountain King scene.

Clip courtesy of NRK archives.

25 10

Henrik Ibsen: A Doll’s House. Drama in three acts, manuscript and first edition

1879

“I must find out who is right, society or me,” announces Nora towards the end of A Doll’s House, the second of Henrik Ibsen’s 12 contemporary social dramas. On the night after Boxing Day, she leaves her husband and their three children. Thanks to Ibsen’s signature retrospective technique, by the time the play reaches its controversial ending, the audience has been shown enough glimpses of the past to know that the marriage of Nora and Torvald Helmer was built on lies and pretence.

A Doll’s House (1879) was Ibsen’s international breakthrough. It is his most frequently performed work around the world and has been translated into more than 70 languages.

Women’s position in society was the subject of heated public debate in the second half of the 19th century. Camilla Collett’s novel Amtmandens Døttre (‘The District Governor’s Daughters’, 1854–55) was one of the first works to cause controversy. In his earliest notes on A Doll’s House, Ibsen wrote: “There are two kinds of spiritual law, two kinds of conscience, one in man and another, altogether different, in woman.” In the play, he explores the real-life consequences of this for women.

First edition published by Gyldendalske Boghandels Forlag (F. Hegel & Søn), Copenhagen.

10

26

When NRK began regular nationwide television broadcasts in 1960, the newly established Fjernsynsteatret (TV drama) unit played an important role in connecting Norwegians to their culture. Now, classic and modern dramas could reach audiences on a hitherto unimaginable scale. The plays of Henrik Ibsen, especially his contemporary social dramas, came as a revelation to many Norwegians who had previously known Ibsen only from reading or by reputation.

The 1973 production of Et dukkehjem ( A Doll’s House), with Lise Fjeldstad as Nora, was the first Norwegian TV drama broadcast in colour. This original production for television, many aspects of which were still familiar from the Norwegian stage tradition, was given a modern feel by means of close-ups, changing camera angles, more relaxed delivery of lines and faster dramatic pace. For instance, the famous scene in which Nora dances a tarantella acquired an intimate fervour that is hard to achieve on stage.

Clip courtesy of NRK archives.

27 10

A Doll’s House, TV adaptation, NRK 1973

Henrik Ibsen: Hedda Gabler. Drama in four acts, manuscript and first edition

1890

While working on Hedda Gabler, published in 1890, Henrik Ibsen noted down one of his ideas for the play: “The traditional delusion that one man suits one woman.” In another note, he described a particular type of woman he had observed:

Main points:

1) They are not all cut out to be mothers.

2) They have a sensual side, but are terrified of scandal.

3) They are aware that there are missions in life but cannot acquire them.

The story of Hedda Gabler, a general’s daughter who ends up shooting herself, generated huge debate at the time. The critics were merciless. Many of them believed the play should have had a clearer moral and lacked a central idea.

As is clear from the use of her maiden name, Hedda Gabler is more her father’s daughter than her husband’s wife. She is bored with Jørgen Tesman, whom she married in order to be provided for. From her father she has inherited nothing but a portrait and two pistols. When she cannot find a path to freedom, she chooses instead to “die beautifully”.

Actresses who have played Hedda Gabler include Ingrid Bergman, Isabelle Huppert and Cate Blanchett.

First edition published by Gyldendalske Boghandels Forlag (F. Hegel & Søn), Copenhagen.

10

28

When NRK began regular nationwide television broadcasts in 1960, the newly established Fjernsynsteatret (TV drama) unit played an important role in connecting Norwegians to their culture. Now, classic and modern dramas could reach audiences on a hitherto unimaginable scale. The plays of Henrik Ibsen, especially his contemporary social dramas, came as a revelation to many Norwegians who had previously known Ibsen only from reading or by reputation.

First broadcast in 1975, the TV production of Hedda Gabler, with Monna Tandberg in the title role, was based on a 1971 production by Nationaltheatret, Norway’s national theatre. It was not a direct reproduction of the stage show, but a studio-produced version adapted to the medium of television. The language of the play was modified, and the camerawork offered viewers a close-up view of the actors, which gave the final scene a particularly intimate character. Otherwise, though, the production remained true to the original play and was recognisably part of the 20th-century Ibsen performing tradition.

Clip courtesy of NRK archives.

29 10

Hedda Gabler, TV adaptation, NRK 1975

Peter Christen Asbjørnsen and Jørgen Moe: Storybook for Children. Norwegian Folk Tales, Vol. I–III

1883–1887

In the late 1830s, Peter Christen Asbjørnsen and Jørgen Moe embarked on a collaboration that was to result in a series of collections of Norwegian folk tales. The first edition appeared in 1841. The two collectors travelled the length and breadth of the country, collecting and writing down stories that had previously been transmitted orally. Henrik Ibsen and Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson were among the authors who drew inspiration from the folk tales.

In 1883 came the first of three volumes of folk tales for children – illustrated by Theodor Kittelsen, Erik Werenskiold and Otto Sinding. It is debatable how suitable some of these unsettling stories were for young children, but the collections were nevertheless a sign of contemporary society’s growing awareness of children and childhood.

The third volume contains a glossary at the back. Readers were familiar with Espen Askeladd as a character, but what does Askeladd (‘Ash Lad’) actually mean?

Well: “The youngest of several brothers who is left at home to putter about in the ashes while the others are out at work.” The folk tales thus became a source of linguistic knowledge for children and adults alike.

Published by Gyldendal, Copenhagen.

11

30

Ivar

Aasen:

Norwegian Dictionary with Danish Definitions 1873

Back in the days when Norwegians still wrote in Danish, the linguist and poet Ivar Aasen paved the way for nynorsk to be adopted as a written language in Norway. In 1850 he published his Ordbog over det norske Folkesprog (‘Dictionary of the Norwegian Vernacular’). Containing over 25,000 headwords, the dictionary was the product of years of systematic collection of dialect words and expressions. Norsk Ordbog med dansk Forklaring (‘Norwegian Dictionary with Danish Definitions’, 1873) is a revised and expanded edition that is testament to Aasen’s accomplishments as a linguist.

Aasen’s pioneering linguistic work occurred at the same time as the Norwegian nation state was taking shape in other areas. Today there are two official written languages in Norway: Norwegian, whose two variants (bokmål and nynorsk) have equal status, and Sami, used by indigenous communities in northern Norway. Sami is a collective term covering several languages, which are the oldest minority languages in Norway.

Ivar Aasen was 58 years old when the photographer Carl Christian Wischmann took the first of three portraits of him. He seems to have had mixed feelings about the experience. On 11 September 1871, Aasen wrote in his diary: “At a photographer’s.” On 13 September he elaborated slightly: “At the photographer’s […] Bad mood.”

Published by Mallings Boghandel, Christiania.

32

12

1870–1874

Photography was introduced in 1839 by Louis Daguerre, a Frenchman, who produced the first images that became known as daguerreotypes. In the early days, very few people had the means or opportunity to have portrait photographs taken, but the practice became increasingly common as the 19th century wore on.

Carl Christian Wischmann was a Danish-Norwegian portrait photographer who ran a studio in Christiania for the last 40 years of his life. This ledger contains a photographic record of all Wischmann’s work from 1870 to 1874, providing a unique snapshot of Christiania’s population at that time. The photographs have been pasted into an old accounting ledger previously used by a shoemaker. Behind and between the pictures, we can make out details of old transactions such as an order for 20 pairs of riding boots. Wischmann’s photographs are all dated and arranged in chronological order. He averaged three customers a day. The subjects represent a cross-section of age groups and social classes. Some are looking straight at the camera, some are looking down, and others to the side. Most of the faces are unknown, but a few are recognisable. On 11 September 1871, Wischmann took the first of three photographs of the linguist Ivar Aasen, which is exhibited here, and which subsequently became the most familiar portrait of Aasen.

33 12

Carl Christian Wischmann’s ledger

Over the summer of 1868 and the following winter, Edvard Grieg wrote his only piano concerto, in the key of A minor. The first performance took place on 3 April 1869 at the Tivoli Gardens in Copenhagen. Grieg was an excellent pianist but had other commitments, so was not present when his friend Edmund Neupert became the concerto’s first soloist. The Morgenbladet newspaper described “an especially interesting work” and was particularly enthused by the last two movements.

Our music critics have reported on this composition with great acclaim, emphasising its originality and its peculiarly Nordic expression.

Several critics highlighted the concerto’s distinctly Nordic character – at a time when the wild, unspoilt landscape was becoming one of Norway’s most powerful symbols.

At the same time, the work followed in the European concerto tradition and fairly quickly became established as part of the international repertoire. Grieg constantly revised the concerto for the rest of his life, especially the orchestration of the great opening chord. This chord alone is all it takes for many people to recognise the concerto, and to this day the piece remains one of the iconic works of Norwegian musical history.

34 13

Edvard Grieg: Piano concerto in A minor, op. 16, manuscript 1868

Concerto for piano and orchestra in A minor, op. 16, 1988

1 Allegro molto moderato | 13:22

2 Adagio | 6:45

3 Allegro moderato molte e marcato | 10:06

From Edvard Grieg (1843–1907), Norsk Kulturråds klassikerserie. Jens Harald Bratlie, piano. Oslo Philharmonic Orchestra, conducted by Mariss Jansons. Polygram Records A/S, Oslo, 1988.

35

Norsk Kvinnesaksforening (the Norwegian Association for Women’s Rights) was founded in 1884 by Gina Krog, a radical feminist, and Hagbard Berner, a more moderate liberal politician. It was the country’s first lobby group for women’s issues. The organisation’s stated objective was to “work to secure women’s rights and rightful place in society”. The first issue of the association’s journal Nylænde (‘New Frontiers’) was published in 1887, edited by Krog, who took over as publisher in 1894.

Norsk Kvinnesaksforening fought long and hard to achieve equal voting rights for women and men. Gina Krog was dedicated to the cause. In a lead article headed “Voting Rights” in the May 1888 issue of Nylænde, the editor dismisses arguments involving justice and human dignity as mere “hollow phrases” if the concept of universal suffrage refers only to “voting rights excluding all women”. Nylænde played an important role not only as the voice of the women’s suffrage campaign in Norway, but also as a platform for women to have their say in public.

In 1913, Norway became the fourth country in the world to introduce universal suffrage for men and women.

Published by Norsk Kvinnesaksforening, Kristiania.

36

14

Gina Krog (ed.): Nylænde, No. 9, periodical

1888

14

Camilla Collett and Emilie Diriks: Forloren

Skildpadde, Nos. 1–5 and 7, handwritten periodical 1837

The author Camilla Collett, née Wergeland, is best known for her novel Amtmandens Døttre (‘The District Governor’s Daughters’, 1854–55). She was a feminist and the first honorary member of Norsk Kvinnesaksforening (the Norwegian Association for Women’s Rights). She also became one of the most prominent contributors to the association’s journal Nylænde.

In the summer of 1837, Camilla Wergeland had yet to make her debut as a writer. She and her friend Emilie Diriks had the idea of producing a magazine, to be published once a week “on fine letter-writing paper” and passed around by hand among “a small select circle of ladies”. They named the magazine Forloren Skildpadde (‘Mock Turtle’) after a dish that every woman of the time was expected to master. Emilie Diriks and Camilla Wergeland had lofty ambitions to produce a literary feast incorporating “the quintessential wit and refinement of ladies”.

Six issues of the magazine were produced. The two editors pretended to be men, ‘Hr. CW’ (Camilla Wergeland) and ‘Hr. ED’ (Emilie Diriks), and wrote all the articles themselves. The content ranged from essays and short stories to travelogues and fictitious death announcements. The magazine can be seen as an attempt by the authors to create a space for their own voices – at a time when women had few public platforms.

37

Edvard Munch: Self-Portrait with Skeleton Arm 1895

Edvard Munch is famous around the world as a painter and printmaker, and is considered one of the most significant artists of the modernist period. Over a career spanning more than 60 years, he experimented with a variety of styles and techniques, including printmaking, drawing, painting and sculpture. SelfPortrait with Skeleton Arm, a well-known work dating from 1895, was one of Munch’s earliest lithographs. The image is built around stark contrasts: the face is white, almost deathly pale, and the background pitch black. The white skeleton arm at the bottom serves as a reminder of human mortality.

The image was printed in Berlin, where Munch had lived since the early 1890s alongside other artists such as Sigbjørn Obstfelder, Gustav Vigeland and August Strindberg. Berlin was the venue for Munch’s most controversial exhibition, which opened on 5 November 1892 and closed after only five days because the critics and the majority of members of the artist association’s board considered the works crude and sketchy. Far from damaging his reputation with the public, however, the affair heralded Munch’s international breakthrough. The following year, 1893, Munch painted his most famous image, The Scream, which along with several later iconic works secured Munch’s unique position in the history of art.

38 15

The Icelandic bard and chief Snorre Sturlason is thought to have written his great work about the Norwegian kings, Heimskringla, in the early 1230s. The text covers the period from Norway’s mythical origins to the battle of Re in Vestfold in the year 1177. Snorre’s histories first reached a mass audience when J.M. Stenersens Forlag published this edition, Kongesagaer (‘Sagas of the Kings’), in 1899. Not only were the sagas widely read; they also gave new impetus to the development of Norwegian literature and the historical fiction genre.

The publishing house took the initiative in publishing the book, and first engaged the illustrators: Halfdan Egedius, Christian Krohg, Gerhard Munthe, Erik Werenskiold, Eilif Peterssen and Wilhelm Wetlesen. Gustav Storm was then commissioned to translate the text from Old Norse. Werenskiold was in overall charge of the illustrations, and Munthe the adornments. Together, they gave Norway’s medieval history a new and distinct aesthetic, with clear ties to the present day. Werenskiold used Fridtjof Nansen as a model for the heroic king Olav Tryggvasson, while Munthe’s characteristic art nouveau designs became hugely popular in the fields of applied art and interior design – despite the book’s very first sentence stating: “Any use of the adornments from this work is prohibited.”

Published by J.M. Stenersens Forlag, Kristiania.

39 16

Snorre Sturlason: Sagas of the Kings 1899

Hulda Garborg: Housekeeping. Recipes and advice for small households, chiefly those in the country, cookbook

1899

The kitchen became a place for books in 1845, when Hanna Winsnes published her cookery book Lærebog i de forskjellige Grene af Husholdningen (‘Textbook on the Various Aspects of Housekeeping’). In a famous essay, the writer Arne Garborg railed against Winsnes’ lack of awareness of her own privilege: It’s all take … take … take … with no thought given to the question of where we are supposed to take it from. Because all is good with the world.

Hulda Garborg was more readily disposed than her husband to appreciate Winsnes’ practical approach to housekeeping. In her own cookery book, Heimestell (‘Housekeeping’, 1899), she borrowed heavily from Winsnes. Garborg’s book was the first cookbook to be written in landsmål, the forerunner of nynorsk, and included a whole chapter on “foolish menfolk”. International influences, however, were of more interest to Garborg – especially German vegetarianism. Her advice to gather and cook mushrooms – tasty, healthy and free – was considered novel and daring.

Hulda Garborg was involved in grassroots cultural activities and efforts to create common national manifestations of Norwegian culture. She founded what was to become Det Norske Teatret, a theatre company performing in nynorsk, as well as establishing and promoting knowledge of folk costumes and folk dancing. The postcard, on display in the showcase drawer, depicts her as a national icon, standing among birch trees and wearing a bunad

17

40

Published

Mai, Kristiania. Postcard photo: Eivind Enger.

by the newspaper Den 17de

1905

In Norway’s referendum on dissolving the union with Sweden, held on 13 August 1905, a rock-solid majority of voters – 99.95 % – voted in favour of dissolution, with only 184 voting against. This showed Sweden that the Norwegian people backed the vote by their elected representatives in the Storting on 7 June 1905 to dissolve the union, which was viewed on the Swedish side as a revolt. Norwegian women, who were not yet allowed to vote, launched a nationwide petition. For the first time since 1380, Norway became a fully independent nation state.

Just three months later, Norwegians were asked to vote on whether the country should be a monarchy or a republic. The outcome was less of a foregone conclusion than that of the August vote, and the Storting was reluctant to hold another referendum with the potential to unleash political chaos. But the republicans demanded to have their say, and Prince Carl of Denmark, who had been offered the throne of Norway, desired a vote of confidence. The new referendum on 12–13 November 1905 was made as simple as possible: vote Yes or No to Prince Carl.

The difference in the design of the two ballots is striking: “ja” (‘yes’) is printed in a large, rounded, open typeface, while “nei” (‘no’) is in smaller, more angular type. The outcome of the referendum was 79 % in favour of offering Prince Carl the throne, with 21 % voting against.

42 18

Yes and No ballots from the referendum on the monarchy

18 King Haakon, Queen Maud and Crown Prince Olav

arriving in Norway, cine footage

1905

On 25 November 1905, just two weeks after the vote to retain the monarchy, Prince Carl – now King Haakon VII – landed in Norway, accompanied by Queen Maud and Crown Prince Olav. This was a major event not only for the newly independent country, but also for the incipient Norwegian film and cinema industry.

Several Scandinavian cinematographers accompanied the royal family, who began their voyage from Copenhagen aboard the Danish royal yacht Dannebrog and transferred to the Norwegian vessel Heimdal for the final approach to Kristiania (Oslo). This resulted in several short newsreels that were screened a few days later at cinemas in the capital and elsewhere. The short clip shown here is one of several surviving pieces of footage. The large crowds and blowing snow clearly made it difficult for the cameraman to do his job, so at times it is hard to make out the new king – despite his upright bearing.

Motion pictures in those days were short, usually no more than a few minutes, and newsreels were an important part of the cinema repertoire. The king’s arrival was the first state occasion in Norway to be documented on film, and the images filmed that day are some of the earliest Norwegian cine footage.

43

Filmed by Peter Elfelt. Some of the footage may be the work of unidentified others.

A law governing Norwegian cinemas was enacted in 1913 and took effect the following year. The law stated that films were to be censored by a central body prior to screening, and provided for municipal ownership and licensing of cinemas. Before 1913, the police had the power to censor theatre, cinema and music hall. An officer would attend on the first day of a show and decide what, if anything, needed to be censored.

The four surviving fragments of the silent film

Dæmonen (‘The Demon’) are the clips that were cut by the censor. The film was produced by Jens Christian Gundersen, who owned several cinemas in Oslo. It was filmed in Denmark, where better studio facilities and more lavish costumes were available, but in the eyes of some people this tainted the film with the kind of immorality for which Danish cinema was notorious. The censored scenes show merry partygoers, erotically charged moments and a stylised French dance – likewise verging on the erotic. The role of the male dancer is played by Per Krohg, better known as a painter.

Dæmonen, one of the earliest Norwegian motion pictures, was released in 1911, two years before the legislation on cinemas was passed.

44 19

Dæmonen, censored film clips 1911

Produced by A/S Norsk Films Kompani. Director: Alfred Lind.

45

‘The South Pole Letter’, letter from Roald Amundsen to King Haakon VII

1911

On 14 December 1911, Roald Amundsen reached the South Pole, accompanied by four chosen members of his expedition: Olav Bjaaland, Helmer Hanssen, Sverre Hassel and Oscar Wisting. They erected a small tent as a visible marker of the pole’s location, and Bjaaland took a picture of the other members of the party standing outside the tent. After four days, they hastened back to their ship, the Fram, so they could be sure of being the first to deliver the news. The expedition was planned in minute detail and was also a carefully stage-managed global media event.

The rival British expedition led by Robert Falcon Scott reached the pole more than a month later, when Amundsen and his men were only a week’s march away from the Fram. Scott’s expedition found the tent and a letter Amundsen had written to the king of Norway – in case they did not make it back. Amundsen also left a note asking Scott to post the letter, which was placed in a cloth pouch sewn from the same fabric as the tent.

All the members of Scott’s expedition perished on their return journey. The letter, still in its cloth pouch, was found with Scott’s body and thus served as proof that Scott too had made it to the pole.

46 20

20 Photographs of the British Antarctic Expedition 1912

These two photographs show Robert Falcon Scott’s men at the South Pole on 18 January 1912. The first picture is of four of the men standing next to the tent that showed the Norwegians had already reached the pole. In the second picture, all the expedition members are seen posing with British and English flags. Their exhaustion and disappointment are evident. Looking at these pictures now, it is impossible to forget that none of these men made it back.

The exposed films were found beside Scott’s body and developed back at base. The photographs are of exceptionally high quality: we can make out the seam in the tent fabric and the shutter release cord in the hand of Edgar Evans. The notes on the back of the photographs were written by Herbert Ponting, an outstanding photographer, who had waited for Scott and the others back at base. Ponting later described Scott’s pictures as “probably the most tragically interesting photographs in the world”.

Top: Discovery of Amundsen’s tent at the South Pole by Captain Scott’s party. January 18th. 1912. This print was made from a negative in the roll ffilm which lay for 8 months beside Scott’s body before it was found by the Search Party, & later developed.

Bottom: Captain Scott, Dr Wilson, Captain Oates, Lieut Bowers and Petty Officer Evans at the South Pole. January 18th 1912. – This print was made from a negative in the roll ffilm which lay for 8 months beside Scott’s body before it was found by the Search Party, and later developed.

47

During the politically turbulent interwar years, a uniquely Norwegian encyclopedia took shape. Compilation of Arbeidernes leksikon (‘The Workers’ Encyclopedia’) began in 1931, and the work was published in instalments between 1932 and 1936. The publisher was Arbeidermagasinet, a socialist literary magazine, and the editors were Jacob Friis and Trond Hegna. The articles were written by members of Mot Dag (‘Towards Day’), a group that was affiliated in the 1920s first to the Norwegian Labour Party, and later to the Communist Party, before becoming an independent revolutionary organisation in 1929.

Arbeidernes leksikon was intended to be an alternative encyclopedia – a counterweight to conventional bourgeois encyclopedias. The underlying editorial principle was that not even scientific knowledge is politically neutral. Modelled on the great Soviet encyclopedia, the project was instigated by the labour movement and the circle surrounding Arbeidermagasinet. The objective was to enlighten the working class on the basis of the movement’s “own views on social development and social conditions”.

The logo on the spine conveys a particular view of knowledge: reading is the path to insight and enlightenment.

Published by Arbeidermagasinets forlag, Oslo.

48 21

Vol.

The Workers’ Encyclopedia,

I–VI 1932–1936

22 Radio news, 9 April 1940, and news broadcast from London, 7 May 1945, NRK

1940 and 1945

When the Second World War broke out in Norway in April 1940, broadcasting assumed a crucial role. The Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation, NRK, had been established in 1933, five years after the country’s first radio broadcasts began. Within a few years, the new medium had been widely adopted by the public and become a tool for connecting people and communities.

During the war, NRK continued to broadcast from London, where the Norwegian government and royal family were in exile. In the autumn of 1941, the German occupation forces began confiscating any radios belonging to Norwegians.

On 9 April 1940, NRK in the person of Toralv Øksnevad – soon to become known as ‘the voice from London’ – announced that German forces had landed in various towns and cities around the Norwegian coast. The German ambassador was reported to have urged Norway not to resist the invasion – a suggestion unanimously rejected by the government.

Five years later, on 7 May 1945, NRK in the person of Hartvig Kiran announced the German surrender. The broadcast ended with 16 special announcements, including “two-legged fox”, “kalvedans for breakfast” and “love without stockings”. These were coded messages to resistance fighters and British agents operating in Norway. The broadcast also included the Morse code for ‘victory’.

1 Dagsnytt (‘Daily News’), 9 April 1940 | 41:30

2 News from London, 7 May 1945 | 3:11

49

Georg W.

Fossum:

Deportation of Norwegian Jews, 35 mm negative 1942

On 26 November 1942, 529 Norwegian Jews were deported from Oslo harbour. A German cargo vessel, the Donau, left Oslo that afternoon and docked in Stettin a few days later. The deportees’ final destination was Auschwitz, where most of them perished immediately in the gas chambers. Only nine of the 529 people survived. The deportation was organised by the Norwegian police in collaboration with the occupying forces.

Georg W. Fossum, who was in his late twenties in 1942, took photographs of wartime Oslo for the civilian resistance movement. He was at the harbour that day in November, having been tipped off by a contact in the police that something was going on. The photograph shows a group of people with their backs to the camera watching the Donau as it rounds Vippetangen point, with the island of Hovedøya in the background.

The image was not made public until it appeared in Aftenposten on 26 January 1994, following an appeal by the journalist Liv Hegna for photographs of the deportation. During the war, the resistance sent exposed films by courier to Stockholm for developing, but in this case the courier was unmasked, so the film remained in Norway and was probably not developed until sometime after the war.

Today, the image serves as a stark reminder of Norway’s complicity in the Holocaust.

23

50

After three years of exploration on the Norwegian continental shelf, Phillips Petroleum Company discovered the world’s biggest oilfield in the autumn of 1969. The field was named Ekofisk. Geologists were initially uncertain as to whether Ekofisk was operationally viable, but trial production showed that oil extraction could prove highly profitable. On 9 June 1971, prime minister Trygve Bratteli, accompanied by parliamentary and government representatives and other guests from Norway and abroad, visited the mobile drilling platform Gulftide to officially open the field.

“Today may be a notable day in our country’s economic history,” declares Bratteli in this excerpt from NRK’s news coverage of the opening ceremony. “I hope the high expectations we have for oil production will be fulfilled.” After a short speech, he pulls back a small, simple curtain to unveil a plaque on the wall of the oil rig – a modest ceremony that heralded an era of dramatic economic and social change for Norway.

The oil industry transformed not only the country’s economy, but Norway’s role and significance on the world stage.

51

24 Official opening of the Ekofisk field, NRK Dagsrevyen 1971

NB! The first 20 seconds of the clip have audio only and no images.

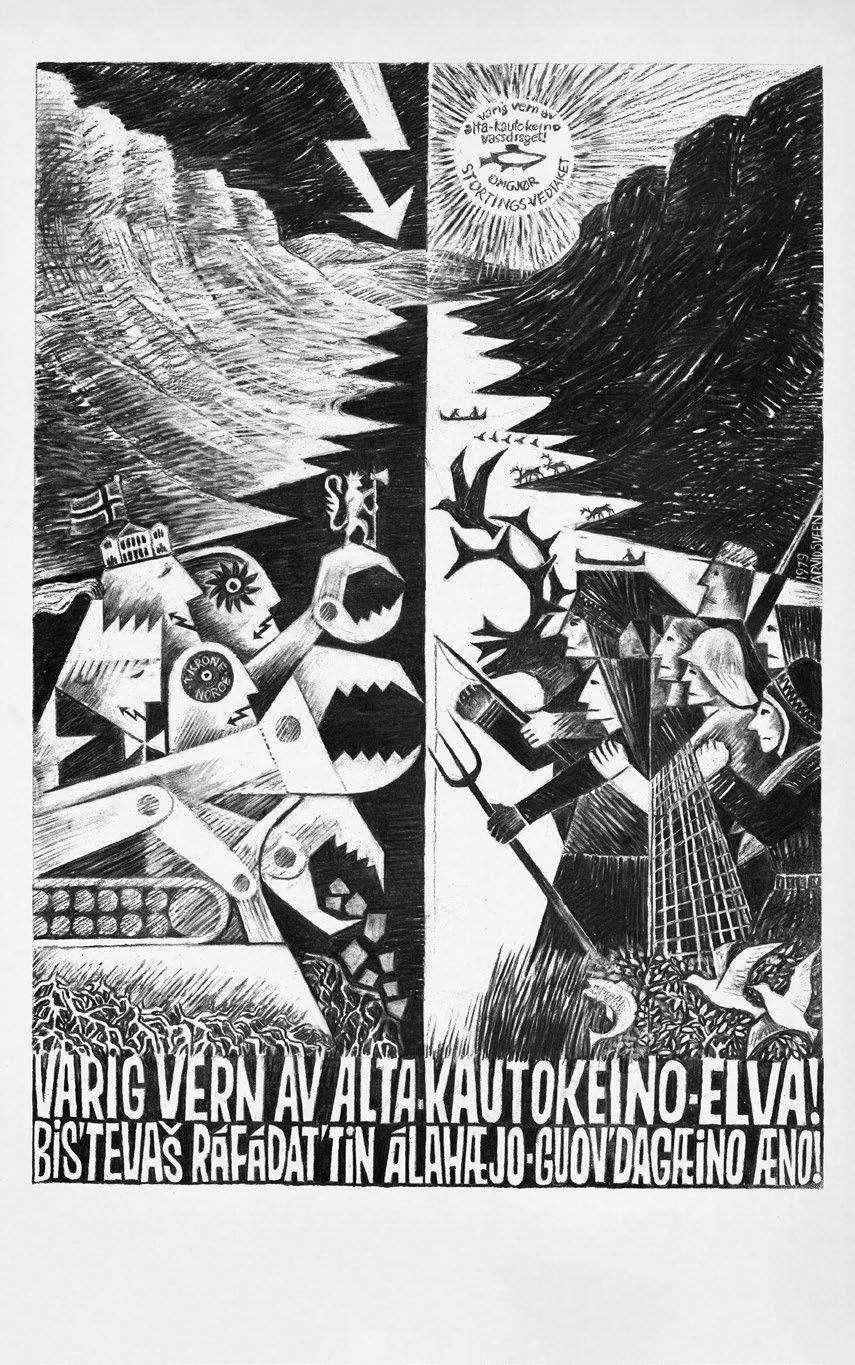

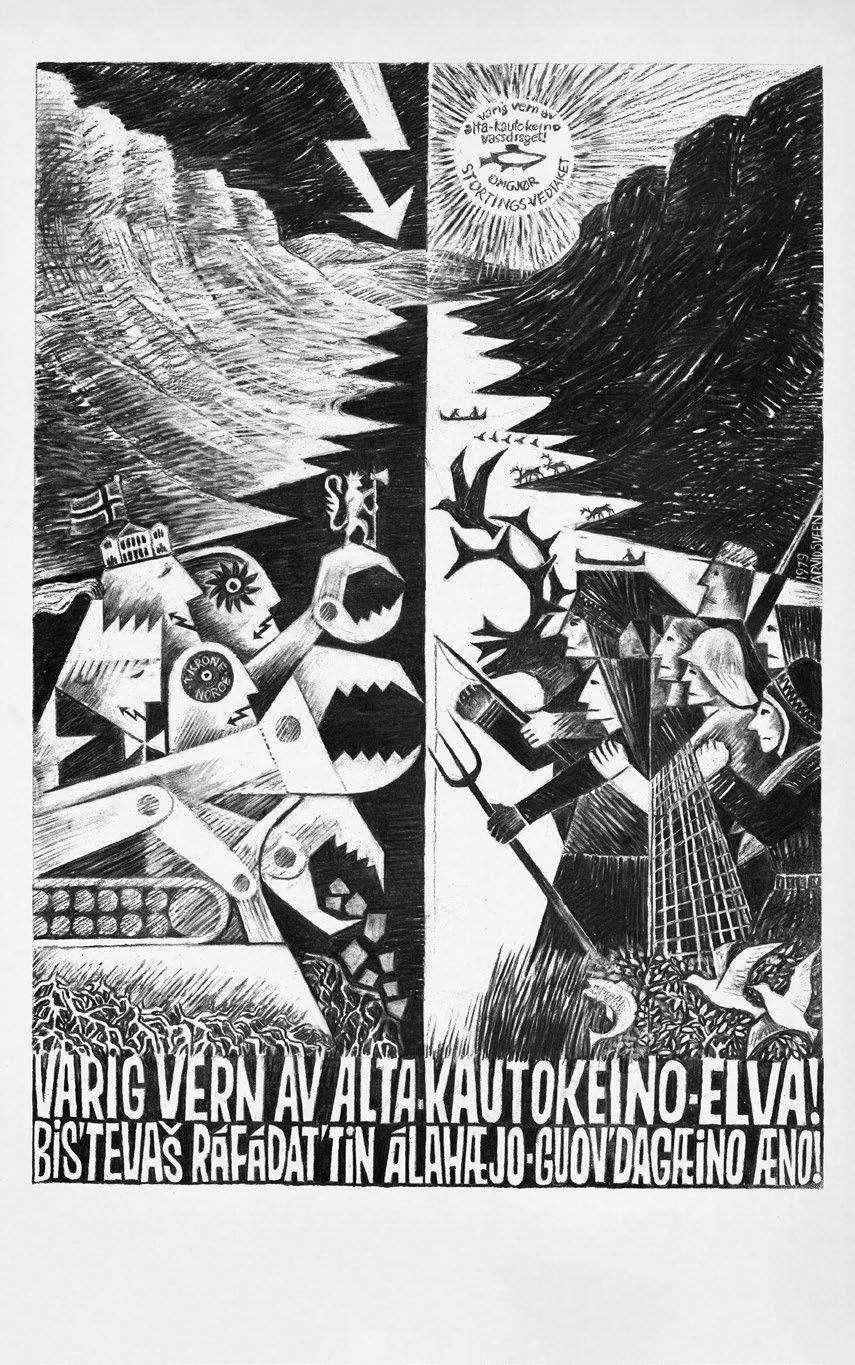

Arvid Sveen: ‘Long-term conservation of the Alta-Kautokeino river!’, poster 1979

In 1968 the Norwegian Water Resources and Energy Directorate (NVE) unveiled plans to develop a hydroelectric scheme on the Alta-Kautokeino river system in northern Norway. The plans soon met with strong, well-organised opposition because of the major impact they would have on the environment, the local population and local economic interests, not least reindeer herding. A grassroots opposition campaign launched in 1978 collected 15,000 signatures on a petition, but the Storting approved the project, which included a 110-metre-high dam in the Sautso gorge, famed for its biodiversity.

The dispute escalated dramatically. In 1979, Sami protestors staged a hunger strike outside the Storting, and activists brought construction work to a halt. Having started out as an issue of local and national interest, the dispute now came to the attention of the growing international movement to protect the rights of indigenous peoples. Arvid Sveen’s poster depicts the Alta-Kautokeino river as the boundary between environmental destruction and conservation, between modern and traditional economic activity, and between the governing elite and the ordinary population.

Norwegianisation had long been the objective of central government policy towards the Sami people, but the Alta-Kautokeino controversy proved a historic turning point. As a direct result, a new law on Sami rights was passed, an article was added to the constitution, and the Sámediggi (Sami Parliament) was set up in 1989 – by which time the hydroelectric scheme had been in operation for two years.

© Arvid Sveen / BONO 2020.

52 25

Darkthrone: A Blaze in the Northern Sky, LP 1992

A Blaze in the Northern Sky, released in the winter of 1992, was Darkthrone’s second album. Along with other Norwegian bands such as Mayhem, Darkthrone defined what subsequently became known as early Norwegian black metal.

The album walks the line between the deadly serious and the theatrically staged. The cover features a grainy photo of one of the band members made up as a corpse in a graveyard. The soundscape is rough, riff-based and lo-fi, the vocals guttural and ugly. The lyrics are about death, warriors, tombs, paganism. The song ‘The Pagan Winter’ opens with an invocation of the Devil:

Horned master of endless time

Summon thy unholy disciples.

For the longest time, Norwegian black metal was a closed musical subculture. During the 1990s, awareness of versions of the genre grew as a result of media coverage of murders and church fires, and later also through black metal bands seeking more commercially and culturally acceptable forms of expression. But Darkthrone stands apart from this narrative.

A Blaze in the Northern Sky appeared just before the scandals and tragedies hit the headlines. The band has been critical of commercialisation and isolated from the general cultural public, and has not played any concerts since the 1990s.

Published by Peaceville Records.

54

26

55

1. Kathaarian Life Code | 10:35

2. In The Shadow Of The Horns | 6:58

3. Paragon Belial | 5:22

4. Where Cold Winds Blow | 7:21

5. A Blaze in the Northern Sky | 4:53

6. The Pagan Winter | 6:34

Founded in 1991, Oslonett was a spin-off from the computer science department at the University of Oslo, where the internet was used as a research platform. The company provided internet services to individuals and small businesses, and offered training for businesses in how to use new information technology. In 1993 it set up Norway’s first commercial website, www.oslonett.no.

During the 1994 Winter Olympics in Lillehammer, Oslonett published a continuous results feed. There was huge interest: in a period of just over 24 hours in mid February, Oslonett had 130,000 hits – a number that made international news at the time. In the autumn of that year, the website likewise covered Norway’s referendum on EU membership. These live feeds have subsequently been cited as one of the reasons why so many Norwegian households were early adopters of the internet.

In 1995, Oslonett launched the Kvasir search engine, modelled on its American counterpart, Yahoo!. Like other portals at that time, Kvasir allowed users both to enter search text and to click on a contents menu to find information. That same year, Oslonett was acquired by the Schibsted media group, as the first step in its expansion into multimedia.

56 27 www.oslonett.no 1994

57

2016

Autumn 2015 saw the premiere of a new web drama series written and directed by Julie Andem and produced by NRK P3. Titled SKAM (‘SHAME’), the series quickly gained a cult following among young adults in particular, subsequently attracting viewers of all ages and becoming an international media sensation.

SKAM introduces us to a group of friends at Hartvig Nissen upper secondary school in the Frogner district of Oslo. The series ran for four seasons and was acclaimed for taking youth culture seriously, and for tackling complex subjects such as homosexuality, rape, mental health and religion. The show was streamed via the SKAM website, where clips, messages and social media posts were posted continuously. The clips were combined each week into a single episode, which also aired on TV. The fictional characters had real profiles on Facebook, Instagram and other social media – which brought the series into public consciousness in an unprecedented way. During the love affair between Noora and William in season 2, hundreds of thousands of viewers engaged with the hashtag #WILLIAMMÅSVARE (‘William must answer’).

Season 3 is all about Isak, who, after a brief period of doubt and denial, recognises that he is in love with Even. Andem’s annotations to the script show that much of the action was improvised.

In 2018 The National Library received the manuscripts for the drama series SKAM, episodes 5 and 8, season 3. Due to light sensitivity the exhibited pages will alternate.

58 28 SKAM

, script for season 3, episode 8, pages 1–6

Adolescence is a time of intense negotiations as to who we are, where we belong, who we wish to be, not to mention who we can be. And who we fall in love with can be critical.

Isak, played by Tarjei Sandvik Moe, is the main character in season 3 of SKAM, which portrays the love affair between two young men. The relationship between Isak and Even, played by Henrik Holm, is complicated, although not necessarily because they are gay. The complicating factors are that Even is already in a relationship and has manic episodes, and that Isak has a difficult relationship with his parents; his mother keeps sending him evangelical Christian messages. This third season seriously addresses the fact that rejecting the heteronormative way of life often brings extra challenges when it comes to defining our identity – even in 2016.

59 28 SKAM, clip from season 3, episode 8, NRK

2016

Clip courtesy of NRK archives.

29 Karpe Diem: Heisann Montebello 2015–2017

The hip-hop duo Karpe Diem (known simply as Karpe since 2017) consists of Chirag Rashmikant Patel, who was raised in Oslo by Indian parents, and Magdi Omar Ytreeide Abdelmaguid, who was raised in Oslo by a Norwegian mother and an Egyptian father. On their debut EP Glasskår (‘Shards’, 2004) they sing about being young people from multicultural backgrounds.

Heisann Montebello (‘Hiya Montebello’) is considered the duo’s most overtly political project to date. In November 2015 the first three tracks were released as singles; the lyrics to one of these songs describe the then minister of justice, Anders Anundsen, as a coward. Three further singles appeared between February and June 2016, followed in August by ‘Gunerius’, which completed the album for the time being. Each of the singles was launched with an accompanying video, and all were later released as a box set. In December 2017, following three exclusive cinema screenings of the experimental music video Adjø Montebello (‘Goodbye Montebello’), the duo released another two songs: ‘Dup-i-dup’ and ‘Rett i foret’.

In the ‘Gunerius’ video, home movie clips from the two artists’ childhood and adolescence are interspersed with Norwegian news footage of the time: political debates between Gro Harlem Brundtland and Kåre Willoch, demonstrations for and against the EU, oil rigs, the consecration of Rosemarie Køhn as Norway’s first female bishop, the killing of Arve Beheim Karlsen. Magdi says: “I’m dancing on the fence, between greed and ambition.”

Published

by

Karpe Diem DA.

60

1. Au Pair. Director: Kristian Berg | 5:45

2. Hvite menn som pusher 50 (‘White men pushing 50’). Director: Marie Kristiansen | 4:01

3. Lett å være rebell i kjellerleiligheten din (‘Easy to be a rebel in your basement flat’). Director: Kavar Singh | 5:12

4. Hus/hotell/slott brenner (‘House/hotel/castle on fire’). Director: Stian Andersen | 4:39

5. Attitudeproblem. Directors: Torgeir Busch, Thea Hvistendahl and Kristoffer Klunk | 5:01

6. Den islamske elefanten (‘The Islamic elephant’). Director: Thea Hvistendahl | 7:32

7. Gunerius. Director: Erik Treimann | 6:18

8. Dupidup. Audio only | 2:36

9. Rett i foret. Audio only | 4:18

61

At every single point in the history of Norwegian publications, the present has comprised not only the sum of past events, but also a range of future possibilities. The National Library of Norway is therefore more than a historical collection; it is also a repository for past visions of the future – at least if they were committed to print. These pamphlets show some of the causes that popular movements in Norway have fought for over the years.

Many of these objectives have been achieved, such as the election of women to parliament and Norway remaining outside the EU. Some causes remain oddities, such as the campaign for the king to hand over the royal palace to the community. Other causes had greater relevance to civil society in the past than they have now. The popular evangelical movements are a case in point, with their missionary work and their efforts to turn Norway into a Christian faith community.

From the 19th century onwards, mass political, religious and ideological movements became important channels for political influence. They changed Norway and brought people together around a common cause. The causes pursued and arguments put forward by voluntary associations have intersected in thought-provoking ways over the years. For instance, the demand by Riksmålsforbundet in 1960 that users of the conservative form of Norwegian should be granted “status and rights as a language community” foreshadowed the rights-based arguments later deployed on behalf of other minorities.

62 30

pamphlets 1771–1994

Mass political and religious movements,

EXHIBITION

Design: Nissen Richards Studio Light: Studio ZNA

The exhibition is produced with financial support from Eckbos Legat and Sparebankstiftelsen DNB.

TEXT CATALOGUE

Translation: Språkverkstaden

Design: Superultraplus Designstudio AS

Print: Erik Tanche Nilssen AS