Alaska Seafood Marketing Institute breaks through the barriers of distance. With marketing programs established across the U.S. and in over 40 countries worldwide, ASMI’s international and domestic marketing efforts build demand across the globe.

This is just one example of how Alaska Seafood Marketing Institute puts all hands on deck to tell the story of wild, sustainable Alaska seafood so you and your family can focus on fishing today and for generations to come.

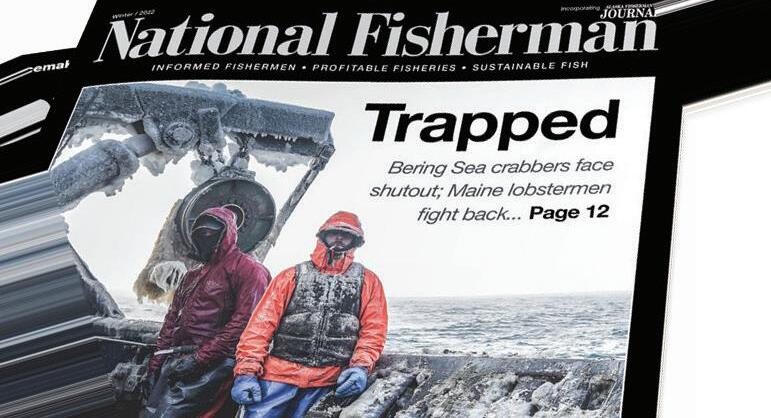

The National Fisherman Mobile App is everything you love about National Fisherman Magazine and NationalFisherman.com all in one place.

• Gain free access to the digital edition of National Fisherman Magazine, download for off-line reading, and easily share with friends.

• Browse the latest news, customize your feeds to fit your interests, and save articles you want to come back to.

• Stay up-to-date on everything Expo with the latest event news, full schedule details, exhibitor list, interactive map and more.

Download today, create your free membership, join our community, and grow along with us!

Take us with you wherever you go:

Or go the app store on your mobile phone and search National Fisherman

While the timing associated with the printed version of National Fisherman has changed, the mission has stayed the same as it has for decades. It’s also evolving, as we’ve made some of those changes based on feedback from you when it comes to creating more timely and accessible content that you can view online or in the palm of your hand.

at’s something you can see in the daily posts on national sherman.com and in the National Fisherman App, providing you with multiple ways to read and experience this content. However, that’s just one of the things that you’ll notice is new and di erent.

Another change on the horizon is related to the Highliner Awards, which is an annual tradition that stretches back to the 1970s. at legacy is set to evolve in a big way in 2023 as this year’s Highliner Awards will be an essential part of Paci c Marine Expo in Seattle. e Advisory Board for PME is currently working on what is set to be the best-ever version of the program and will also help select winners from each region.

You’ll nd new voices and perspectives in this issue and online, which starts with my own but also includes people like Carli Stewart (who comes from a fourth-generation shing family o the coast of Maine) as well as multiple new features. Additionally, you’ll notice a cleaner look with the layout and format of this month’s issue.

With all of that said, you might be asking about what isn’t set to change for NF, and there will undoubtedly be more to come. Rest assured, all of them are designed to ensure the only publication dedicated to the entire U.S. commercial shing industry becomes that much stronger for this generation and the next.

PUBLISHER: Bob Callahan EDITORIAL DIRECTOR: Jeremiah Karpowicz ASSOCIATE EDITOR: Kirk Moore BOATS & GEAR EDITOR: Paul Molyneaux

CONTENT SPECIALIST: Carli Stewart DIGITAL PROJECT MANAGER / ART DIRECTOR: Doug Stewart NORTH PACIFIC BUREAU CHIEF: Charlie Ess

FIELD EDITORS: Larry Chowning, Michael Crowley, CORRESPONDENTS: John DeSantis, Maureen Donald, Brian Hagenbuch, Dayna Harpster, John Lee, Caroline Losneck, Nick Rahaim ADVERTISING COORDINATOR: Wendy Jalbert / wjalbert@divcom.com / Tel. (207) 842-5616 GROUP SALES DIRECTOR: Christine Salmon / csalmon@divcom.com / Tel. (207) 842-5530 CLASSIFIED ADVERTISING: (800) 842-5603 classi eds@divcom.com

ME 04112-7438. Subscription prices: 1 year – U.S. $12.95; 2 years U.S. $22.95. ese rates apply for U.S. subscriptions only. Add $10 for Canada addresses. Outside U.S./Canada add $25 (airmail delivery). All orders must be in U.S. funds drawn on a U.S. bank. All other countries, including Canada and Mexico, please add $10 postage per year. For subscription information only, call: 1 (800) 959-5073. Periodicals postage paid at Portland, Maine, and at additional mailing o ces. POSTMASTER: Send address changes only to Subscription Service Department, PO Box 176 Lincolnshire, IL 60069. Canada Post International Publications Mail product (Canadian Distribution) Sales Agreement No. 40028984, National Fisherman. Return undeliverable Canadian addresses to Circulation Dept. or DPGM, 4960-2 Walker Rd., Windsor, ON N9A 6J3. READERS: All editorial correspondence should be mailed to: National Fisherman, Portland, ME 04112-7438.

As we look toward spring, we’re grateful for Alaska’s seafood, and the incredibly important role it plays in feeding Alaskans, our guests and our visitors a perfect protein. As a hotelier and restaurateur — running the Captain Cook Hotel, Snow City Café, Spenard Roadhouse, South Restaurant and Crush Bistro — we are particularly aware of just how much work, investment and logistics it takes to get wild Alaska seafood to people’s tables, across Alaska and around the world. Alaska is a state rooted in sheries.

We’re known for our world-class sheries, our high-quality seafood, and the tenacity of our shermen. It’s hard to nd an Alaskan who hasn’t been touched by the seafood industry, from commercial shing families to those frequenting restaurants around the state.

With the height of the primary shing and tourist seasons on the horizon, Alaskans should feel proud of our sh and those that harvest, process and serve it, when they see Alaska seafood in grocery stores and restaurants — and we do. It truly takes an entire state to keep the responsible harvest of Alaska seafood running. is awe-in-

spiringly complex system and supply chain, from family-owned vessels to shoreside processors to restaurant and lodging operations like ours, requires a commitment to quality and sustainability, not to mention lots of e ort from a multitude of people to successfully pull it o .

Whether on the water or in the restaurant, every season has its ups and downs, and the only thing you can count on is change. However, our industry is adaptive by nature and there’s a lot to be proud of from the past year. Not only did we see the return to full-service operations, serving more wild Alaska seafood at our restaurants to both locals and visitors alike, we also saw record-breaking harvests in Bristol Bay, with nearly 300 million pounds of sockeye — the largest harvest since commercial shing began in 1883.

is past year also saw other iconic sheries face challenges and changes, with our menus and o erings following suit. One of Alaska’s strengths is that its incredible diversity of sheries and shing communities are committed to understanding and responding to these changes. Our state is full of supporters of healthy sh, healthy sheries, and healthy economies, and this gives us con dence in the future. Especially throughout the past few years impacted by the covid-19 pandemic, the Alaska seafood industry has proven its role in sustaining economic resiliency, supporting small businesses like ours in communities throughout the state.

We’re already looking forward to the coming year and the excitement of each season’s unique catch. While many sheries across the state have wrapped up as we hunker down for winter, others are just getting started, and in truth, Alaska’s seafood industry contributes to the economic stability of Alaska year-round. We value and cherish Alaska’s commitment to highest quality, responsibly-harvested Alaska seafood, a key contributor to our success.

As 2023 dawns, join us in taking a moment to step back to appreciate the coordinated harvest and distribution of wild food that feeds Alaskans and the world with such a world class and delicious product. Whether you’re

cooking fresh-caught Alaska seafood in your own kitchen, picking some up from your local grocery store or ordering in your local restaurant, you are a part of a broader community, joined together through Alaska’s seafood

Culinary sockeye salmon; mixed Alaskan seafood; smoked sockeye platter. ASMI photos.

Raquel Edelen is vice president of operations for the Hotel Captain Cook, where she has worked for 21 years.

Laile Fairbairn is the founder of Snow City Cafe and South and the co-founder of Spenard Roadhouse. She is a 2023 James Beard Foundation semi nalist for Outstanding Restauranteur.

THE PSS PRO FEATURES...

Commercial design with unmatched durability.

Reinforced silicone bellow increases pressure and temperature limits compared to nitrile bellows.

Upgraded materials prolongs lifespan in comparison to the Type A PSS Shaft Seals.

Learn more at

Ideally, the Great Lakes Future Fishers Initiative will compensate participating commercial fishers for their time and expertise. Participating commercial fishers might help to develop recruitment and training materials. They could spend time at job fairs, local schools and technical colleges talking about their work. They will likely spend time in training workshops and mentoring new deckhands. Likewise, the funding being sought would provide financial incentives for those in training.

The Great Lakes Future Fishers Initiative aims to meet the immediate needs of existing fisheries by focusing on providing reliable deckhands who develop skills to keep them employed during the winter months when many Great Lakes fishing operations shut down. Deckhand training is critical to maintaining and growing a Great Lakes fisheries workforce, as is training new people to be fish processors.

BY SHARON MOEN, DR. LAUREN JESCOVITCH, DR. TITUS SEILHEIMER, FATIMA ABDL-HALEEMII’d say the fishing is as good as I’ve seen it,” said Craig Hoopman, president of the Wisconsin Lake Superior Commercial Fishing Board and sixth-generation commercial fisherman working out of Bayfield, Wisc. “There are certainly fish but it’s hard to say who will be bringing them in over the next few decades. I’m in my 50’s and I’m considered one of the kids.”

The lack of young people in the U.S. willing and able to fish commercially is old news, especially in coastal communities like Bayfield, which grew around the grit of commercial fishing families plying the Great Lakes in the 1800s.

But old news can still galvanize Congress. The U.S. Senate passed the Young Fishermen’s Development Act

in December 2020. This bill authorized the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Sea Grant Office to provide training and other assistance for young fishermen through an annual grant program that could be worth up to $2 million.

The National Sea Grant Office (NSGO) responded to their new directive. In 2021, they awarded roughly $900,000 to 11 projects that would identify ways to meet the training needs of the future workforce of the U.S. commercial fishing industry.

Wisconsin and Michigan Sea Grant led one of these projects, which included interviews with state and tribal commercial fishers and fish processors, a Great Lakes-wide industry survey and a review of existing training programs.

This groundwork is the first step toward implementing the Great Lakes Future Fishers Initiative. The Initiative is envisioned as a recruitment and training program in which commercial fishers would partner with Sea Grant staff to find and mentor new deckhands and processors.

As Wisconsin and Michigan Sea Grant staff work with the commercial fishers in their states toward funding and piloting the envisioned Great Lakes Future Fishers Initiative, they are keeping three guiding principles in mind:

1. KEEP IT LOCAL

2. OFFER OPTIONS

3. SUPPORT MENTORS

Place-based strategies for recruiting and training efforts conducted in partnership with commercial fishers will maximize the likelihood of recruiting and retaining a new workforce that understands why their work is important and finds deeper meaning in it. It will also keep more economic activities within the community while providing job opportunities for youth and others wanting to stay near their hometowns.

Place-based strategies incorporate the circumstances of a location and actively engage residents. The Great Lakes

Future Fishers Initiative envisions identifying commercial shers willing to work with Sea Grant to mentor new members of the workforce. Together, they will network with local high schools, middle schools and technical colleges to spark students’ interests in life-on-the-water careers, especially with respect to commercial shing.

ere are an estimated 125 licensed commercial shermen plying the U.S. waters of the Great Lakes. ey tend to have deep roots in their business and their communities. e high cost of start-up and maintenance – including expertise, boats and gear – means that today’s Great Lakes shers often grew up commercially shing in a particular place, inherited their livelihoods and would ideally pass their businesses to family members.

An argument for seeking a workforce from within a Great Lakes coastal community includes housing. ese communities are often plagued by a ordable housing shortages from April to November due to tourism.

is timeframe spans the prime months of shing on the Great Lakes. People who do not live in the shing community already might not be able to nd an a ordable place to live. To that point, the Red Cli Fish Company, run by the tribal council of the Red Cli Band of Lake Superior Chippewa, suggested possibly using rooms in the casino the tribe manages for housing their shers-in-training, should band members want to live near the boats.

e U.S. coastline of the Great Lakes spans 4,530 miles. is is signi cant in compared to the length of the U.S.’s Atlantic coast (2,165 miles). It’s three times longer than the U.S.’s western seaboard of California, Oregon and Washington (1,293 miles). Adding to that, the U.S. Great Lakes sheries are managed by eight state and multiple tribal agencies. e physical length and jurisdictional complexity of the Great Lakes suggests that a successful career-building program will bene t

from being exible and adaptive. It will accommodate the speci cs: geography, regulations, culture and individual business practices.

Tribal-licensed shermen are among the 125 commercial shers. Tribes are working to sustain a commercial shing workforce within the few remaining indigenous communities exercising their shing rights on the Great Lakes. Before issuing a license or hiring deckhands, tribal councils typically require applicants to show tribal membership. Fishing as a rights holder, or a sovereign nation, can incorporate cultural practices, values and perspectives not shared by other communities. A training program that is exible and adaptive would be able to serve both tribal-licensed and state-licensed shermen.

When surveyed, the Great Lakes commercial shing industry supported the idea of Sea Grant o ering fundamental training that could help and inspire workers. Modules could cover topics such as setting expectations, working across generations and communicating the value of the industry to regulators, consumers and legislators. In areas with increased recreational shing tra c, new and older shers might bene t from con ict resolution training.

Many Great Lakes commercial shers are involved in sh processing. Some have second jobs during the shing season, such as teaching, nursing, contracting for research or piloting boats. Creating opportunities for cross-training in ways that new shers have skills that are valuable for multiple industries is important to the envisioned Great Lakes Future Fishers Initiative. For example, CPR, rst aid and heavy machinery safety training could lead to working as a rst responder. Engine repair and welding skills could lead to jobs that require mechanical know-how such as in an automotive shop. Sanitation control procedures and knife skills training could open opportunities in catering or restaurants.

Great Lakes shers and sh processors indicate that they are ready and willing to mentor a new workforce. ey seek workers who show up and are willing to learn skills such as handling nets and how to cut a sh. e hours can be odd and long. e work can be messy and seasonal. A passion for being on the water as the sun rises seems to keep many commercial shers motivated.

It was clear that the Great Lakes shers and sh processors would prefer training their workers themselves when it comes to certain skills. ey envisioned that the Great Lakes Future Fishers Initiative would allocate time for the employers to train new workers to lift nets, cut sh and work with the automated equipment on their boats and in their processing facilities

SHARON MOEN

Is vice president of operations for the Hotel Captain Cook, where she has worked for 21 years.

LAILE FAIRBAIRN

Is Wisconsin Sea Grant’s food- sh outreach coordinator based out of Superior, Wis.

Is a sheries and aquaculture extension educator for Michigan Sea Grant and Michigan State University in the Houghton/ Hancock area of Mich.

Is Wisconsin Sea Grant’s sheries specialist based out of Manitowoc, Wis.

FATIMA ABDL-HALEEM

Is a master’s degree candidate in Environment and Resources at the University of WisconsinMadison.

BY MEGAN WALDREP

BY MEGAN WALDREP

“And the rain descended, and the floods came, and the winds blew….”

My husband Chris Dabney and I hunker down in Ojai, California, a little mountain valley 14 miles from the Ventura coast and 23 miles from Channel Islands Harbor, Chris’s home port. I’ve only seen storms like this during hurricane season in the South, our home in the off-season. “Deluge” is the word for it. We pull up the blinds and trade the TV for rain.

It got me thinking how rainstorms in the South aren’t feared like out West. The sub-tropical East Coast is “Lowcountry,” sea level flat, and easy to fill with the tides. In California, deep-sloping mountains meet the sea, and in many places, the two are separated by a thin stretch of road called the Pacific Coast Highway that merges with Highway 101.

The section from Ventura to Santa Barbara currently bottlenecks into one working lane, with exits leading to surf breaks, private communities, vista views, and nothing else. Basically, there are few back roads to get around because the Santa Ynez Mountains are in the way.

It can be hard to grasp that Southern California, an agricultural pylon for the United States, is actually dry as a bone. We’re talking desert vibes. Where velvet green moss grows in the Pacific Northwest, sagebrush, succulents, and more drought-resistant plants cover our hillsides. In other words, the ground ain’t used to rain, can’t keep up when it pours, and when it hits the mountains, the earth goes with it.

Mudslides in the Golden State mean boulders, Jurassic Park-looking rocks

that bring down towering eucalyptus trees and pave paths like snow plows. Detritus glides across the hard dirt so violently that residents nearby can hear the tumble and feel the quake beneath their feet. The difference between rain in the South and our stretch of California is like a bathtub filling with water and a fire hose at full throttle.

We just learned that road closures and forced evacuations are in effect for surrounding areas, which contradicts itself. So, we sit, trapped on the

mountain, checking that the oak trees surrounding our home aren’t uprooting as our neighbor’s across the street. We watch the destruction unfold through local Instagram accounts, feeling a million miles away, and like everyone else, we wait.

Chris and I drive to a bridge over the Ventura River. A place that, heretofore, was a dry, hikable trail but is now roaring underfoot like the Mississippi. Police barricade the opposite end of the bridge, turning people away from a mudslide up the road.

Chris points to waterfalls on the highest peaks, reminiscent of Hawaii if you squint hard enough. It’s a mixed bag; the soothing sight of water in the desert and a heavy heart for those on the coast. We watch for a few minutes, then head home before the next storm hits.

Back home, I read messages from two other partners of commercial fishermen who live in Ventura, and the severity of the storm finally sinks in. While roadblocks in Ojai expect to clear by tomorrow, Shelby Stahl, mom of three, the wife of prawn, crab, and black cod fisherman Tyler Stahl, and entrepreneur Lindsey Mickelson Hoadley, mom of two and the wife of urchin and spiny lobster fisherman John Hoadley report other challenges.

“Right now, we are dealing with (Highway 101) closed, so we can’t get to the boat,” Hoadely said. “The Santa Barbara Harbor bottom is filling in, so boats can’t come in and out freely. The harbor is full of debris, and the coastline is demolished. Everyone is just dealing with the natural catastrophe! But we are holding tight and getting a little extra family time in and taking it day by day.”

Stahl, whose husband also fishes out of Santa Barbara, reports a different issue. “Tyler was supposed to leave tonight but can’t, and our guy who delivers fish has been stuck on the 101 since last night!”

If Santa Barbara is this bad, what does that mean for harbors along the coast?

I ask Chris if he’s heard from shermen at the Channel Islands Harbor. No word, he says, but the swell is dying, so he’ll have a weather window to check traps before the next storm cell. My heart drops, but I say nothing. It’s his job, after all.

“I hope the worst is over,” Hoadley messages. “We have some big issues to deal with moving forward. It will be interesting to see how the rest of our lobster plays out.”

Later that evening, our neighbor delivers a secondhand report – beachcombers are taking lobsters from traps crashed ashore. Fishermen are out thousands of dollars in gear and commodities, trash and debris cover the beach, and no one is happy. At least the spiny lobsters may be enjoyed. Or even released.

I check in with Critters Fresh Seafood, a family operation in Malibu, forty miles south of Ventura. Co-owner Denise Honaker gives me the lowdown and adds that she has “seen a lot” in her forty-plus years with a commercial sherman. Her husband, Captain Scott Honaker, owner/operator of F/V Critters, and his deck crew, Ryan Koverman and Jimmy Olivarri, are still surveying the damage, carefully unlodging traps from the rocks and surf.

“As you know, each trap can cost at least three hundred dollars, and we lost over one hundred. We are still guring it out,” Honaker said. “ e cleanup continues, and we will continue to nd the traps to make sure the shore is clear of them. We have had so many people in our shing community, and customers ask how they can help, which is so heart-warming.”

Back in Ventura, Stahl jots down the following during a spotty connection on her husband’s rst trip out. “Hard to tell how the storm a ected the shing,” he said. “Big swell and strong currents

made it a little harder. I don’t know how many sh were lost by long-lining. Lots of debris in the water, trees, bamboo, milk crates, etc. Makes it hard to sh at night with all the debris.”

Days later, Hoadley checks in. “We faired well overall, thank goodness. John was able to recover a good amount of traps. Now he is displaced out of the S.B. harbor due to the harbor mouth situation and the city not dredging it,” Hoadley said. “He’s at the Channel Islands Harbor now, but it takes twice as long to get to where he shes from there. I think the city is supposed to get the dredge here next week.”

As for me, a week later, I’m still working through the anxiety I felt on Chris’s rst day back at sea. Preparing for this piece, I drove down the mountain to take a few pictures that you see here. With my journalist hat on, I navigated past detours and ashing signs that screamed “High Surf Warning.” Roadblocks brought me to a beach near Ventura Harbor, lled with logs, reeds, and rubbish.

While photographing the mess, a loud boom from the shorepound snapped my attention and took my breath away. Walls of mud curled at the peaks from angry tides, swell, and wind – the aftermath, and a precursor to the next storm simultaneously.

To start, you’ll need some fresh crab meat, rice paper wrappers and your choice of llings. I like to use avocado, shredded carrots, red cabbage and cilantro, but you can use whatever you have on hand. Simply lay out a wrapper, add your llings and roll it up tightly.

One tip for making spring rolls in a tight space is to have all of your ingredients prepped and ready to go before you start rolling. is will make the process much smoother and less cluttered.

Once your spring rolls are rolled, they’re ready to be devoured. Dip them in the rich and savory peanut sauce, infused with ginger and hoisin, which adds a harmonious blend of avors in every bite, elevating your taste experience. Serve them with a cold beverage and enjoy a satisfying meal perfect for a sherman after a long day on the water.

Soft Spring Rolls with Crab - Makes 10-12

3 ounces thin rice noodles, cooked

12 round rice paper sheets

1 1/2 cups crabmeat

1 large avocado, sliced into strips

2 cups red cabbage, shredded 2 cups carrot, shredded 1/2 cup cilantro leaves 1/2 cup mint leaves 1/2 cup basil leaves 6 green onions, cut into thin strips

In a bowl, mix together the sauce ingredients until smooth. Arrange all the ingredients separately around a large cutting board or tray set before you. Set out a platter to hold the nished rolls, as well as a large shallow bowl lled with very warm water.

Is a writer based in Ojai, California, and Wilmington, N.C. Her husband, Chris Dabney, is a second-generation California spiny lobsterman and Bristol Bay sherman, which gives Megan plenty to dish about on her lifestyle blog for partners of commercial shermen at meganwaldrep.com.

Fallow her @megan.waldrep

To make each roll, slide one sheet of rice paper into the pan of warm water and press gently to submerge it for about 15 seconds. Remove it carefully, draining the water and place it before you on the cutting board.

Line up a horizontal row of each of the following ingredients on the rice paper sheet, starting on the lowest third of the sheet and working away from you: a small amount of crab meat, a tangle of noodles, a few avocado slices, a row of cabbage and carrots, a row of cilantro, mint and basil and a row of green onion slivers on top.

Fold the bottom half of the wrapper over the lling, hold the lling in place, tuck in the sides and roll tightly. Repeat with the remaining lling and serve with the dipping sauce.

BY CARLI STEWART

BY CARLI STEWART

Even with the weekend’s past snowstorm blowing through Rockport, Maine, New England’s fishing community came together to discuss policy, new regulations, and their fishing heritage. When the hotel rooms were open for reservations, the forum sold out in about a week and a half. People of the local fishing communities were just itching to get back to the annual festivities of the Maine Fishermen’s Forum (MFF).

We were able to celebrate Chilloa Young’s 25 years of hard work organizing the MFF. Young served on the board for years before taking on the role as coordinator. Though this was her last year before retirement, all guests were able to give Young well wishes and welcome the new executive director, Kathleen Gilbert.

This weekend was full steam ahead for some arriving Wednesday evening to attend the early Thursday morning seminars. This included an all-day seminar focused on fisheries engagement in offshore wind development. I arrived Thursday evening just in time for the seafood reception. All food served at dinner was donated by local farms, fishermen, aquaculturists, and other businesses that buy directly from the boat. MFF board president Steve Train facilitated the silent auction that was open throughout the buffet-style dinner. The money raised

during the auction was donated to this year’s eight scholarship winners

Friday morning consisted of more seminars, including the Maine Lobstermen’s Association 69th annual meeting. People from the MLA board, lobster dealers, fishing families, and scientists all congregated to hear this past year’s updates. These updates were on offshore wind development concerns and on the legal process of regulations that Maine lobstermen must follow regarding North Atlantic right whales.

said that the MLA will be working on innovative gear solutions, saying, “we must add something to the toolbox that we don’t already have now.” The MLA has raised $2.5 million towards their $10 million goal and will continue to keep fighting. MLA president Kristan Porter introduced the new COO, Amber Jean-Nickel, who is eager to stand with the MLA and save Maine lobstermen.

The graying of the fleet is quite literally the number of gray hairs we have out on the water now. The average age of New England groundfish and lobster captains is over 55 years old. Passing on the traditions in fishing families has dramatically decreased due to the number of changes in the fishing industries. Though there is an opportunity for the older generation to show people the ropes, the number of student licenses has declined.

During this seminar, Training the Next Generation of Fishermen, many local New England organizations such as, New England Young Fishermen’s Alliance, NOAA and Maine Sea Grant, Eastern Maine Skippers, and Marine Resource Education Program (MREP) spoke on how they are trying to integrate the younger generation into the shing industry.

e reality of getting youngsters involved is complicated. It is much more extensive than just jumping on a ski and shing. e future for some sheries is unknown and access to permits and licenses is expensive. e Young Fishermen’s Development Act of 2020 was put in place to address the Graying of the Fleet and provide training, education, outreach, and technical assistance. is act provides a federal grant to winning applicants to put towards all shing and boat needs, excluding harvesting rights, quota, and licenses.

e past few years have shown how tough it can be to sell your own catch directly o the boat. It is crucial to be able to market your own product and make the connections to help you sell.

e New England Young Fishermen’s Alliance will take you step by step to form a business plan from deckhand to captain of your own boat – and help connect you with scientists and shery managers to engage in the policies for di erent sheries.

CARLI STEWART

Is a Content Specialist for National Fishermen. She comes from a fourth-generation shing family o the coast of Maine. Her background consists of growing her own business within the marine community. She resides on one of the islands o the coast of Maine while also supporting the lobster community she grew up in.

cstewart@divcom.com

Living and working as a commercial sherman breeds a countless number of stories, many of which could ll an entire book. Terry Evers did just that with his new memoir, Fifteen Seasons, which is all about the people and personalities that de ned a commercial troll salmon shery along the Central Oregon Coast from 1977-1991. It’s an especially personal account of the people, problems and adventures that comprised region and industry at the time, which begins in an unexpected way:

A school textbook salesman buys a commercial salmon dory boat and takes his thirteen-year-old son out on the cold Paci c Ocean waters o the Oregon Coast for an entire summer. What could possibly go wrong?

To get a sense of how the book answers that question, we talked with Evers about what drove the creation of the book, who this memoir is ultimately for, and much more.

National Fisherman: Your memoir is dedicated to your father, but was honoring his legacy the ultimate driver behind putting this book together?

FIFTEEN SEASONS A MEMOIR

BY TERRY EVERSTerry Evers: e tipping point for engaging in the project was to honor my father for the risk he took to enter the industry and open the door for countless experiences thereafter. However, the book project was something I considered for a number of years. I enjoyed keeping sh catch records, statistics, and journal entries when we shed. Dad and I talked about how I should do something with them a number of times. In the late 90s I was learning how to create webpages, and needing a topic, I chose dory shing. us began the Dory Page, and the website gained a decent following. Later I migrated it to Facebook where it continues to run strong. at made me aware there was certainly an audience. I just needed the stars to align regarding time, publishing options, and improving my writing, in addition to my father’s passing. While the shing and father-son relationship are integral parts, over time it was important to share Newport Bayfront culture of the 70s and how it gradually changed over time.

Will shermen from places other than the Central Oregon Coast get something out of this book or are the stories and insights speci cally relevant to people familiar with that area?

Yes! It has already happened. Via Facebook I’ve heard back from several people beyond the Oregon Coast. Some shing and boating Facebook groups and discussion forums have been gracious enough to allow me to post about the book. ere has been interest on the East Coast and all along the West Coast, especially among commercial shermen in Alaska. One man from Minnesota has a dory, which is rare in that part of the country. It opened up some great dialogue as he enjoyed the book very much. I even had a person in Australia purchase the book!

Would you say this book is more about individual people, the commercial shing industry as a whole or something else?

It’s certainly about the people and the industry. e dory eet was composed of so many unique individuals who came together for a common bond in the summers. ere were people such as teachers, construction workers, truck drivers, chemists, biologists, year-round shermen, pharmacists who all found ways to dory sh. e industry changed so much from when we started until we ended. e book chronicles the changes that took place and how that related to our participation. Fifteen Seasons is also about a father-son relationship and how that grew, changed, and strengthened over time. A unique addition is the integration of music and how certain songs became benchmarks for each year we shed. An example would be how the songs “Silly Love Songs” by Paul McCartney and “Dreams” by Fleetwood Mac were so much a part of the fabric either of the overall culture or as a personal experience. Each chapter contains a meaningful setlist of songs or albums.

Lawsuit alleges economic fallout, damage to Maine lobster brand

The Maine Lobstermen’s Association and industry allies led a defamation lawsuit March 13 against the Monterey Bay Aquarium Foundation, alleging the aquarium’s statements that Maine lobster gear threatens endangered right whales “have caused substantial economic harm to plainti s, as well as to the Maine lobster brand.”

Joining the MLA in the lawsuit, led in the U.S. District Court for Maine, are Bean Maine Lobster Inc., the Maine Coast Fishermen’s Association, Atwood Lobster LLC, and Bug Catcher Inc., owned by Gerry Cushman, a sixth-generation sherman from Port Clyde.

According to a statement from the plainti s, the lawsuit “alleges that Monterey Bay Aquarium knowingly ignored and mischaracterized scienti c data to convince the public that, despite their sustainable practices, Maine lobstermen are causing harm to endangered North Atlantic right whales.”

e ght erupted in September 2022 when the California aquarium announced that its widely publicized “Seafood Watch” program would downgrading its rating of Mainecaught lobster from a cautionary “yellow” to “red” rating –recommending that seafood consumers and businesses avoid buying Maine lobsters.

e decision was announced by the aquarium “because ‘scienti c data’ supposedly linked Maine lobster shing practices to right whale deaths and injuries,” according to the lobstermen. “While promoting the Aquarium’s new ‘red’ rating for Maine lobster, Aquarium o cials stated that consumers’ ‘appetite for seafood is driving a species to extinction.’”

Maine lobster had been rated “yellow” on the Seafood Watch years earlier. Despite the aquarium’s new position, “federal data show that there are no documented right whale deaths attributed to Maine lobster gear, and there has not been a recorded right whale entanglement in Maine lobster gear in nearly twenty years,” according to the lobstermen.

In a statement the Monterey Bay Aquarium said the Maine lawsuit – and a similar action led by Massachusetts lobstermen – seek to shut down the organization’s free speech rights:

“

ese meritless lawsuits ignore the extensive evidence that these sheries pose a serious risk to the survival of the endangered North Atlantic right whale, and they seek to curtail the First Amendment rights of a beloved institution that educates the public about the importance of a healthy ocean.”

e aquarium came under heavy criticism for its listing decision, and it maintains a lengthy online explanation of its reasoning.

“ e North Atlantic right whale is an endangered species at high risk of extinction and entanglement in gear using vertical lines is the leading cause of injury and death to these whales,” the aquarium states. “Current management measures do not go far enough to mitigate entanglement risks and allow the North Atlantic right whale to recover.”

e National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration lists ship strikes as the other leading cause of whale fatalities. During January and February a seriously entangled right whale was tracked o North Carolina, and a 20-year-old male right whale washed up at Virginia Beach, Va., the apparent victim of a ship strike.

e Maine lawsuit lays out much of the

same positions industry advocates have taken in challenging expanded National Marine Fisheries Service restrictions on the lobster shery.

e potential for entanglement and whale mortality has been reduced “due in large part to a shift of right whales further away from the Maine lobster shery, and to the extensive conservation measures Maine lobstermen have adopted— some of which were put in place years after the Aquarium had issued its ‘yellow’ rating,” according to the lobstermen.

According to the MLA, the Maine lobster eet has reduced its lines in the water by about 30,000 miles of rope, and employed weak links in the gear so marine mammals that encounter a trap line can break free. e lawsuit contends those e orts created “a model for what a sustainable and environmentally responsible shery can do.”

“ is is a signi cant lawsuit that will

help eradicate the damage done by folks who have no clue about the care taken by lobstermen to protect the ecosystem and the ocean,” stated John Petersdorf, CEO of Bean Maine Lobster Inc. “Lobstermen are very responsible stewards of the ocean. We cannot sit back and let lies to the contrary prevail.”

“Our stewardship practice is a tradition that de nes what Maine is all about,” lobsterman Cushman said in the plainti ’s statement. “ e barrage of lies about Maine shing practices must be confronted and defeated by truth.”

e lawsuit seeks monetary relief “and an injunction ordering the aquarium to remove and retract all its defamatory statements.”

e lobstermen’s complaint, led in federal court in Portland by their legal team, says Monterey Aquarium disregarded evidence that the Maine lobster shery is a much lesser risk to whales.

Drought years, declining river habitats taking their toll on salmon populations.

March is usually a time of bustle and activity on the port docks of the Oregon Coast. Salmon shermen return to the docks to ready their trollers. Crabbers with salmon permits begin the process of transforming their boats for the upcoming season. Hay racks arrive, gurdies are put on, hydraulic lines are reconnected, and crab tanks removed.

Fishermen exchange news of season openers, which hoochies and spoons they think will be hottest, what the price might be, and where they believe the salmon will show up rst. Spring comes with renewed promise as crab harvest has slowed down and the excitement of chasing Chinook salmon takes hold.

at most likely won’t be happening for most of Oregon, and all of California this year, after the the Paci c Fishery Management Council released its season alternatives for the Chinook salmon season in California, Oregon, and Washington. ese three alternatives are released each year for consideration, with each one presenting a di erent season structure, before the season is set, giving shermen a chance to voice their preferences in regards to opener lengths, which months typically o er better shing, and con icts

with other sheries.

As shermen had feared, following the presentations at the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife Salmon Commission meeting on Feb. 27, and the CDFW meeting on March 1, which showed catastrophically poor returns in the Klamath and Sacramento Rivers, and low projections for 2023, each of the alternatives that have been o ered for consideration con rm the worst; commercial salmon season may be closed on all but the most northern tip of the Oregon coast until Sept. 1, and it may not open at all in California.

After Sept. 1, salmon caught in Oregon are known as “credit card sh” and do not count towards the impacts of the current calendar year but are taken from the following year’s allowable impact. e Washington season, which has little to no impact on the decimated sh populations of the struggling California rivers, stands set to open as usual. Salmon shermen in Oregon are now seeking out Washington permits for sale or lease in the hopes that they might still have a season, even if they have to go north.

Salmon seasons are considered and formulated each year based on the lowest stock, meaning that they are set with the intention of avoiding impacts to the river with the most struggling salmon population. In recent years, Oregon shermen have struggled for years through cuts to their seasons as e orts have been made to maximize escapement to the Klamath and Sacramento Rivers. As Eric Schindler, leader of the ODFW Ocean Salmon Management Project, stated in the ODFW meeting, “risk aversion is the goal.”

Despite these e orts to avoid further harm to the a ected river populations, extreme drought years have taken their toll, along with anthropogenic processes. ey have caused higher river temperatures, decreased ow, and smaller habitat sizes in crucial areas of the river that must remain viable to support the salmon.

e worsening situation re ected in the decreasing salmon returns and escapements caused shermen’s associations in California to issue a joint statement calling for the immediate closure of the California salmon season, and the issuance of disaster relief, in an e ort to ensure that the salmon populations do not completely collapse.

Oregon shermen will likely be seeking the same disaster relief as they struggle to nd an alternative stream of income for the spring and summer if the salmon season is closed.

What is usually an exciting and hopeful time of year on the docks of Oregon quickly turned into one of disbelief and dismay over the future of the salmon shery and the future of the shermen’s livelihoods. Salmon shermen who rely heavily on a scally rewarding season will have to look elsewhere, if they can, for the income they need to survive, pinning their hopes on spring crab, black cod, halibut, and albacore.

Pace of o shore wind energy development overwhelming sheries science, advocates say.

impacts on sheries survey work.

Calling that funding “a good start,” the letter still warns that it is still far too low given the rapid pace of o shore wind leasing by the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management.

“ ere are 31 surveys that will be impacted across the country and NMFS representatives have identi ed a $2 million cost per survey per year to address OSW impacts,” the letter states. “Without this funding, Congress will hamstring the agency’s ability to develop and test new survey methodologies, calibrate previous decades’ survey data with new survey methods, implement new survey methodologies, and communicate these changes with (regional shery) councils and shery stakeholders.”

Experts from all levels of the commercial shing industry will help guide PME’s educational progrrams on topics including including boat building, how climate change is a ecting shing seasons and new technology.

DATA SHOWING REBOUND IN LOUISIANA AND DECLINE IN

Mitigating the e ect of o shore wind development on federal scienti c sheries surveys requires a major increase in funding, potentially more than $120 million a year, according to a new request to Congress from industry advocates.

e Seafood Harvesters of America and Responsible

O shore Development Alliance say that money is needed to help o set the impacts of o shore on federal sheries surveys – a cornerstone of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s sheries management and conserva-

tion mission.

In a March 17 letter to a Congressional appropriations subcomittee, the groups recommend a price tag at $2 million a year for each of 31 shery surveys managed by the National Marine Fisheries Service that will be a ected by o shore wind projects, plus $10 million more for each of six NMFS regional science centers to address issues with wind energy developments.

e letter thanks Congress for its scal year 2023 funding that added $16.5 million across NMFS to address o shore wind issues – including $7 million for

NMFS cooperative research projects give shermen and processors a role in science “while building trust in management outcomes and decisions,” the letter notes.

More cooperative research will help understanding sheries behavior and operational needs in relation to o shore wind – and can provide new work for shermen who are displaced from shing grounds by o shore wind projects. With their smaller vessels commercial shermen can help NMFS collect data around wind turbine arrays that the agency’s larger research vessels cannot access, the groups say.

Louisiana boats landed 43.7 percent of U.S. warm water shrimp in 2022, while Texas landings declined significantly.

e sanctuary would encompass 770,000 square miles in mid-ocean around islands, atolls and reefs already part of the Paci c Remote Islands Marine National Monument.

BY CAROLINE LOSNECK

BY CAROLINE LOSNECK

When the new fishing year begins on May 1, Northeast ground fishermen will be facing some new regulations and management.

In Massachusetts, some people are hopeful that a new cadre of aspiring fishermen in Cape Cod will be paying close attention. That’s because a training program, offered by the non-profit Cape Cod Commercial Fishermen’s Alliance, is focused on bringing younger people into local

is 55 according to the New England Young Fishermen’s Alliance (NEYFA).

The Fishermen Training program offered by Cape Cod Fishermen’s Alliance links new or beginner fishermen to local fishing fleets, and offers potential opportunities in a very handson way. There was a time when everyone participating in the training might have been focused almost exclusively on learning about fishing on well-established species like cod and haddock. But, the dynamics of being a successful groundfisherman have shifted.

“I love hearing stories from the old timers about cod and haddock,” says Stephanie Sykes, the program and outreach coordinator of the Cape Cod Commercial Fishermen’s Alliance, “whereas now, our gillnet fleets tend to target skates and dogfish.”

The training program has adapted to the realities of Cape Cod’s fisheries, including less of a focus on cod. “There are a few boats that still groundfish,” adds Sykes, “but their business is usually diversified.” In other words, groundfishing remains part of the training, but it is one small part of the larger equation for Cape Cod fishermen.

fisheries — including learning about what it takes to enter into what has been described as “a graying fishery.” In New England, the average age of groundfish and lobster captains

In places like Cape Cod, where the name reveals the one-time dominance of cod, shifting to and then educating consumers about other local (but less known) sustainable fish, such as hake, is one part of the solution. According to NOAA data, Atlantic cod was plentiful in the past, but by 2021, the catch dropped to about 1.3 million pounds harvested (valued at $2.9

million) — the lowest haul in recorded history. A 2019 stock assessment revealed that the Gulf of Maine cod was making “inadequate progress” toward rebuilding.

The regulatory New England Fishery Management Council (NEFMC), alongside various policy, management and commercial fishing partners, have been working for some time to rebuild Gulf of Maine cod. However, council spokeswoman Janice Plante says “the stock is classified ‘overfished,’ meaning the biomass is below where it should be, with ‘overfishing occurring,’ meaning fishing mortality is too high, since 2011, as well as in some of the years before that.”

A new plan from NEFMC (which is part of Framework 65) will implement a decade of low catch limits, with the goal of rebuilding the Gulf of Maine cod stock. It will also guide the 2023 fishing year.

The 10-year rebuilding period is strategic, adds Plante. “The Council could have selected a shorter rebuilding time, but that would have led to deeper cuts to commercial catches and recreational fisheries and would not have considered the uncertainties of natural mortality, climate change, and recruitment. The longer rebuilding period considers biology and the needs of fishing communities.”

With the stock and landings both struggling, and the amount of fishing pressure allowed being very low, the fishery industry has been staying within its allowable catch limits. “Yet still,” adds Plante, “overall biomass remains very low and we’ve had poor recruitment.” Unfavorable environmental conditions may likely prove to be a critical factor inhibiting the stock’s ability to rebuild.

Big increases for cod over the next decade remain unlikely,

as the Nobska, was built at Fairhaven Shipyard and designed by Farrell & Farrell Naval Architects. Steve Kennedy photo.

adds Plante. And in the short term will also remain low. In addition to Framework 65, there is also an expansion of atsea monitoring and other new monitoring rules that Northeast groundfish fishermen will continue to adapt to.

Jerry Leeman is a commercial fisherman from Maine, who fishes mostly haddock these days, often for Blue Harvest Fisheries in New Bedford, Mass. As he sees it, overfishing of cod is not the main issue.

“Who’s overfishing? We’re down to about 17 active boats in the New England groundfishing fleet. Landings are low because no one is bothering. I’m seeing them up and down the seaboard! We run away from the damn things, because it costs us financially to catch them. You have to be on top of your game and stay away.”

For a list of distributors or to become a distributor please visit our website at:

Similar to cod, haddock stocks are facing pressures. In 2021, total commercial landings of haddock totaled around 16 million pounds and were valued at approximately $20 million, according to the NOAA Fisheries. But the Gulf of Maine haddock catch limit will also be significantly lower in fishing year 2023 than in 2022, because the most recent updated stock assessment indicated that biomass is much lower than expected. The catch limit for Gulf of Maine haddock is down 84 percent in the 2023 fishing year compared to 2022, while

t he Georges Bank stock is also down signi cantly.

Leeman says he is concerned about the haddock resource, and how it impacts his bottom line. “It’s going but it’s a matter of these restrictions that are about to come into play. ey’re asking for a 83 percent reduction.”

Leeman, who was featured as part of a 2022 report by e New Bedford Light/ProPublica (“How Foreign Private Equity Hooked New England’s Fishing Industry” July 2022) that revealed the impacts of consolidation and private equity investment in the New Bedford ground sh eet, feels the upcoming haddock cuts are not called for, in part, because they are based on assessments that do not reveal a full picture of stock abundance or health, and only cover a small area. “I don’t think there should be a cut at all, there should be status quo, until we do an accurate biomass assessment.”

Leeman says the May1 shing year start is coming up soon, but his sh of choice feels out of reach.

“If you go in the Gulf of Maine and catch haddock, it will cost you money. ere are so few of us left in New England anymore. It’s hard to say about prices, to see what baselines are for allowable catch per year. When everyone who’s sitting on permits sees they need sh, it starts to be a price war.” He says he tries to stay optimistic, but that it can be a lot to manage.

“We’ll all be at the bread line if they keep it up. I don’t want to be a pessimist, but boats will just shut down.” In an ideal world, Leeman says, things would be a bit di erent for ground shermen. For one thing, he wishes he owned his own vessel, among other things.

“I’d prefer to be working back at home. Especially for guys like me doing long trips.”

Time will tell how ground shing eets and markets respond once the shing year kicks o in May 2023. In mid-January, cod was getting average prices of $4.35-$4.42 and haddock $2.03 at the Portland Fish Exchange fresh seafood auction in Maine. In early February, average prices in New Bedford Massachusetts were $2.68 for market cod and $2.26 for haddock.

Looking ahead, another factor that could potentially impact the management of cod in the future is a deeper understanding of stock structures. e Atlantic Cod Research Track Stock Assessment enabled NEFMC’s Atlantic Cod Stock Structure Working Group

to look closely at cod stock structure. And the initial results, according to NEFMC’s Janice Plante, “concluded that we may have more than two cod stocks.”

e Gulf of Maine cod and Georges Bank cod stocks are already clearly recognized as distinct, but the working group concluded that there might be four or ve stocks. Plante says the results of this analysis are expected to come out this summer.

“If the results reveal more than two stocks, a recommendation will be made to see how the stocks will be assessed separately on a management side and how the council will potentially transition to a possible new stock structure.”

For now, regulators, policy makers, shermen and communities will continue to work to preserve the groundsh industry as best they can.

Who’s over shing? We’re down to about 17 active boats in the New England ground shing eet”

There is something almost Dalai Lama-esque about Chris Brown.

The Dali Lama tends to talk about the future a lot:

“As people alive today, we must consider future generations: a clean environment is a human right like any other. It is therefore part of our responsibility toward others to ensure that the world we pass on is as healthy, if not healthier, than we found it.”

In Chris Brown’s case, the Dalai Lama quote is something he lives day in and day out, as a commercial fisherman in Rhode Island. He has been fishing for decades, and has a deep interest in preserving the ocean and fisheries for future generations. A longtime dedication to the industry has allowed Brown to cultivate what might best be described

as enlightenment.

“Chris has been a north star for the commercial fishing industry,” says Leigh Habegger, executive director of the Seafood Harvesters of America. “I like to say he’s often 5-10 years ahead of his time, a true visionary for the industry and he pushes us to continue striving for excellence in all that we do on and off the water.”

Brown, 64, grew up in Point Judith, Rhode Island, a place he calls “a quintessential commercial port” with the vast majority of docks still being used for fishing boats. Point Judith is almost two hours south of Boston, on the western side of Narragansett Bay, where it opens to Rhode Island Sound. “It’s small here,” adds Brown. “Everyone knows everyone, which is

Contuinted on page 22

Mimi Stafford is a rarity among U.S. commercial fishers. A 72-year-old grandmother of three, she has been working the Gulf and Atlantic waters of the lower Florida Keys since the 1970s, running 200 lobster traps out of a 24-foot, flat-bottomed skiff she bought in 1983 — fishing mostly alone.

She is fiercely devoted to protecting and preserving her industry, but for decades has managed to deftly and successfully bridge the prickly divide between fishers and the scientific and conservation communities.

“I think it is important to look at fisheries and our environment with an eye for sustainability and diversity,” Stafford said.

“I’m a believer in citizen science. I’d like to leave this place thinking somehow

things will be a little better. We’ve got to all be part of the solution.”

Stafford arrived in the Keys in 1974 with husband Simon shortly after both graduated from Swansea University in Wales with degrees in marine biology and microbiology. As a child, Mimi had fished and boated on frequent vacations in the Keys, but Simon, born in England, had never visited the U.S. until after their marriage. Both gravitated toward making a living on the island chain’s bountiful waters — collecting sand dollars, diving for lobster, and raking sponges.

From the 1980s, the couple each ran their own boat — “We couldn’t both be the captain!” Mimi says — she in her shallow-draft T-Craft and, later, Simon and their son Dylan trapping both lobster and stone crab out of a 43foot Torres called Key Limey.

To this day, Mimi Sta ord still loves shing alone. But unlike 40 years ago when she hauled traps by hand, she now uses an electric puller.

“Lobster is doing pretty well. I’m doing as well as ever,” she said. “I’m just happy to still be doing it. I love it. I love going out by myself. I love the quiet.”

e Sta ords are active members of the Florida Keys Commercial Fishermen’s Association — a prominent industry advocacy group — and Mimi also works together with several local marine conservation and research groups to improve sheries habitats. Both husband and wife apply their scienti c education to confront environmental and economic issues a ecting the commercial shing industry.

e couple were early supporters of the state-mandated lobster trap reduction program in the Keys, which has helped stabilize the shery over the past two decades. ey also backed FKCFA’s initiative to stabilize the stone crab shery through increased minimum sizes and a shorter harvest season.

At the same time, Sta ord has worked with the non-pro t conservation organization Reef Relief since its inception and still serves on its board — establishing mooring sites to protect coral reefs before the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary took over that program; monitoring post-larval lobster collectors for recruitment studies and conducting plankton tows to gauge conch recruitment.

Sta ord has assisted scienti c researchers with water quality studies to determine the impacts of harmful algal blooms such as red tide and is currently working on a sponge restoration project with Florida Sea Grant near her waterfront home. She serves on the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary Advisory Council and on the South Atlantic Fishery Management Council’s lobster advisory board.

Reef Relief executive director Mill Mc-

Cleary says Sta ord’s deep knowledge is a huge resource: “She understands the history of the Keys and water policy and how it a ects the ecosystem and the commercial shing industry. She has a strong connection to a lot of scientists doing research on sponge and lobster habitat and has scientists give presentations at our meetings on sponges, stone crab, and lobsters.”

While Sta ord is very concerned about water quality issues that trickle from mainland Florida to foul Keys waters, she’s equally focused on the disappearance of working waterfronts locally and throughout the U.S. In many coastal communities, developers gobble up prime commercial waterfront land, get rid of shing docks and equipment storage, and replace that infrastructure with condos and recreational boat barns.

Indeed, the Sta ords may fall victim to this trend: they could lose their dockage and trap storage space on Stock Island now that a developer has bought the marina where they work.

“We are losing the waterfront,” Mimi said. “I don’t think we’re being pushed out by regulations. It’s by gentri cation.”

Another issue of great concern is the longtime push by commercial divers (and some state regulators) to create a

casita program for harvesting lobsters in the Keys. Casitas (a Spanish word meaning ‘little houses’) are submerged structures that aggregate lobsters so divers can harvest them. Unlike traps, casitas have no oating identi cation buoys; divers would apply for permits to place them underwater and then locate them later with GPS.

e Sta ords and most other Keys commercial lobster trappers vehemently oppose the legalization of casitas and have urged the state sheries commission not to approve it.

“Casitas are underwater, out of sight,” Mimi said. “It would punish the rest of us trying to play by the rules. It creates a ‘wild west’ situation-- a nightmare for law enforcement.”

Nevertheless, Mimi believes that land development, the tourism industry, and commercial shing can achieve a successful balance.

“If we rely too much upon one industry, be it shing or tourism, in the long run it is to our peril,” she said. “A healthy environment and community need diversity and wise planning to survive and thrive.”

“We day shed [and] I enjoyed the lifestyle so much that I’m a day sherman to this day. I still enjoy it. You go out and come in, and have a life.” ese days, Brown shes on his 45-foot Proud Mary, which he’s owned for a decade. “I have a small boat and my grandfather had a small boat.” He says there used to be a lot of day shermen in Point Judith, but that they’ve become less common. He credits his hardworking, skilled and dedicated crew for making it all work. “I’ve had the same crew for two decades. Dean West, the best crew man in Point Judith!”

Brown has been active in sheries management, science, and education and outreach e orts for decades.

“When I was a young kid, the Point Judith Fishermen’s Cooperative was one of the most successful ones in the country. ere was a board and shermen took turns serving on the board. ey were the leaders in the community. It was a respected position.”

CONTINUED FROM PAGE 22

both a plus and a negative.”

Brown started hanging around the Point Judith docks as a youngster. His uncle owned a store called Galilee Grocery that provisioned shing boats. “I’d help put the food on the boats after the store had closed.” Brown jokes that, in a way, the arrangement was “kind of a daycare thing” since he’d often work alongside his mom, who had a job in the store. Whenever he had downtime after supplying the boats, Brown would sh o the docks.

e conversations he had with “the old timer shermen” left a big impression on Brown: “You’re gonna improve your vocabulary, at 6 or 7 years old!” Soon enough, his duties increased. “I started to shovel sh and unload the boats. I

had begun my ascent into commercial shing in the most logical way–with a shovel in hand.” By the time he was 17 years old, he would go shing during school vacations.

As he neared the end of high school, he had just one thing on his mind. “I remember being sent to the guidance counselor and he said ‘How are you gonna get to college if you can’t get through high school?’ I said ‘I’m not going to college, I’m going shing!’”

Over time, his thinking has evolved slightly, but he does not regret a thing about the path he chose, “because shing has given me the opportunity to learn many things. It’s an education everyday.”

Brown follows in his grandfather William Roberston’s footsteps, particularly when it comes to work-life balance.

In Nov 1983, Inc. magazine called the Point Judith Fishermen’s Cooperative “one of the oldest, largest, and most successful shing co-ops in the nation, with 82 member boats, 110 employees, and 1982 revenues of $24 million.”

But for Brown, the bigger purpose of Point Judith’s Co-op transcended shing and earning money. “Out of that came an accepted reality that you will serve. You will serve the community in some capacity.” By the time the co-op shuttered, in large part due to stocks collapsing, “we went without a uni ed voice in the state.” So, he helped found the Rhode Island Commercial Fishermen’s Association (which is now part of Commercial Fisheries Center of Rhode Island) and became its president.

But Brown felt there was still more to do.

“Nationally, it appreared that we needed an organization that gave people a place to hang their hat. We aligned around the belief that shing is a way of life, and that anything you love and respect you’re going to be less inclined to harm.”

In 2012, he was a founding member of the Seafood Harvesters of America, which represents commercial shermen from the Bering Sea in Alaska to the Gulf of Mexico and north to New England, with a focus on accountability, stewardship and sustainability in shing practices, science and management. Brown is currently in his ninth year as president (he took one year o ).

In 2016, Brown was recognized at the White House, with a “Champions of Change” sustainable seafood award. “I was one of 10 or so people to be honored by President Obama. It was incredibly humbling. When your beliefs translate into recognition and appreciation, there is no better feeling. We had a lot of activity going on then: ending over shing, management and conservation, we’d blurred the line between conservation and commercial shing – that they’re one. at’s the hard stu . Walking away from your people at times, to take them someplace better.”

Brown’s approach has earned the esteem of peers, near and far. “If you know Chris, you know he’s the order of our group. He’s not just for Chris. He cares about all of it,” says Bob Dooley, a founding member, past president of Seafood Harvesters of America and retired commercial sherman. He considers Chris a leader and friend, despite living on di erent coasts. “He’s got a big voice because of how he brings us all together. When we have issues that are not in focus, he’s the guy who brings it together.”

Of course, issues do become heated, and contentious.

“I know I’ve uni ed the opposition,” says Brown. “You can’t be smootchin’ ass all the time. You try and e ect change. And often, the choices you

make in the industry aren’t popular choices — and people aren’t afraid to tell you about it! And you gotta hear it ¬— and they’re not all wrong.”

ere have been times when Brown felt pressure and even scorn from peers over di ering views on ocean health and conservation. But through it all, he relied on his own experience as a guide. “I participated in the greatest stock decline in American history. I helped kill cod, like everyone else. ere were no conservation e orts, we just ruined it. at was a terrible moment for me. I didn’t want to have that be a legacy.”

It was then when he started attending council meetings to understand how national sheries management systems worked.

“It occurred to me that good policy gives rise to good outcomes. It occurred to me [that] we’d better start looking out. You can’t trick the ocean. You can over sh and you create a thief, and often you’re stealing.”

When re ecting on recent attempts to rebuild once abundant New England stocks, like cod, Brown says: “You have to try. Whether or not we’ll be e ective is to be determined. We can certainly do better than we have. We are legally mandated to bring stocks back to the position of health. We have to increase levels of funding for science, because the oceans are the leading edge of climate change. If we can’t do it with the oceans, it doesn’t fare well for us.”

Ultimately, Brown says it’s simple. “I deeply care about the condition of the ocean. at’s my goal. e ocean that’s before us in Block Island Sound doesn’t remotely resemble the ocean that was here 40 years ago. Seasons have changes, species do, too. ings that used to be gone in September now hang around till January. ere is no denying that. e guys see it. ey get it.”

He gets philosophical when considering how di erent people respond to climate change. “I think at the heart of all

climate deniers beliefs [is] they struggle with their own mentality. For me, to be able to openly acknowledge climate change goes hand in hand with the fact that no one lives forever.”

Brown says the importance of the ocean extends beyond what is visible. “What bothers me greatly is the collective disconnect that people have from ocean health to their own. e ocean doesn’t only have value as a subject of something to extract something from. It’s the greatest economic engine on the face of the earth, but only if we don’t take everything out of it.”

Anytime Brown needs more inspiration, he recalls the eary years he spent with his grandfather, William Roberston. “He used to take me shing on the little Lucy M and explain things to me, in what I didn’t necessarily understand at the time. He was self-educated as well, but he educated himself. He was a chemist, then sherman and he taught me things about the ocean, and on our camping experiences on the land. We didn’t waste anything! It was crazy, we’d catch tires and bring them back on the dock. Catch Navy wire, bring it in and recycle it. He’d say “Don’t eat your seed corn, boy.”

Brown recalled a moment with his grandfather that he’s never forgotten. “He was on his deathbed. I’d been going in to see him. One day he asked ‘How’s the shing?’ I said ‘not very good.’ He said ‘Yellowtail? Cod?’ He went down the line to every species, from his days of great shing and he said, ‘What happened?’” “I said ‘I think we over shed and broke it.’ He reached out, gave me a bang in the chest and said, ‘We broke it, you x it.’ at was his sense of accountability.”

And this appears to be Brown’s guiding principle, also.

“You don’t always end up where you started. I got in this to catch sh and make money– and here I am trying to save the ocean! You end up forming a relationship with that which you’re depending on.”

e

BY CHARLIE ESS

BY CHARLIE ESS

On a chilly Oregon morning in January, Rob Seitz tosses off the lines to the South Bay, his 59-foot steel boat that he runs for pink shrimp and Dungeness crab. As he heads out to sea his Dungie pots have been stacked in tiers and lashed firmly on deck. There’s plenty of bait in the lockers, but four large wooden barrels mounted in a custom cradle on the flying bridge set him apart from others in the fleet.

In a world of ever-changing environmental and political climates, the lore, the romance and the salty aesthetics of commercial fishing might be lost if not for enclaves the likes of Astoria, Ore. And even that’s changing in recent years, if you talk to local folks who are fighting to preserve the town’s fishing heritage.

“It’s changed a lot since I moved here,” says Seitz, who’s called Astoria home since 1992. “I used to see lots of local fishermen and loggers when I went downtown, but now I don’t see very many.”

Seitz, 55, was raised on a homestead and fished the years of his young life in Cook Inlet, in Alaska. With declining fishing opportunities in the inlet and in the aftermath of the 1989 Valdez oil spill he went south in hopes of jumping on an albacore troller headed to the South Pacific. Those plans to fish albacore didn’t work out. However, he ended up fishing on local boats out of Astoria, bought his own boat, met his wife, Tiffani and put down permanent roots.

Though the genesis of commercial fishing in Astoria and the fabled Columbia River lies within interpretation of what constitutes legal trade, explorers in the 1700’s

bartered with local tribes to acquire salmon for food. In the early 1800’s Hudson’s Bay Company began purchasing salmon from local tribes and shipping it in salt barrels to other ports including Hawaii.

The process of salting salmon evolved to canning in the mid-1800’s, and with it exponential growth of a commercial gill net fleet. In 1866, there were two gill netters calling Astoria home, and by 1881 the fleet numbered 1,200 boats.

Today, 144 commercial vessels have registered with Astoria as their homeport. Though most of them keep permanent slips in the harbor at nearby Warrenton, the local shipyard in Astoria has won renown for its flexibility and services for repairs and retrofitting

vessels along the West Coast.

“It’s good,” says Seitz. “It’s on port property, and it’s right next to the Englund Marine Supply building. They have welding supplies, hydraulics, stuff like that. It works good because you can just walk over there instead of having to drive.” In addition to the wealth of marine hardware at England’s Seitz notes that a local cooperative of independent welders support projects in the yard.

“You can hire one or hire them all, depending on job size,” he says. He capitalized on the yard’s attributes when it came time to refurbish the South Bay. Work included gutting old insulation out of the fish hold and replacing bulkheads.

Then, there are the fisheries. The Oregon coast near Astoria and the Columbia River has seen dungeness shrimp harvests of more than 33 million pounds in the 2004-2005 season, but in recent years ex-vessel values have driven revenues to all-time highs. In the 2021-2022 season local dungeness fisheries generated more than $91 million.

Likewise, shrimp fishing has been booming in the past two years. The 2021 harvest (according to the most recent state Department of Fish and Wildlife) for Oregon came in at 46.7 million pounds for revenues of $23.6 million.

Among regional issues affecting Astoria’s fisheries, Seitz is part of a national working group concerned about the outmigration of catch shares from fishermen to non-fishing private organizations. He recently traveled to DC with five other groups representing catch share fisheries from around the country.

“We went to Washington DC to advocate for catch-share reform,” he says. “We can see that in a lot of these fisheries non-fishermen are becoming the owners to the fishing rights, and it makes it very hard for the next generation to get into the fisheries.”

Mixed stock salmon harvests on the Columbia River continue to challenge the industry. Fish destined for some tributaries have been listed as endangered while others return in numbers that warrant commercial harvest. For more than a decade the Oregon Dept. of Fish and Wildlife and stakeholders in tribal and commercial fisheries have pined for fishing methods that would be more selective than gill nets.

Among commercial shing attractions Astoria is also home to the FisherPoets gathering. It draws upon the talents of writers, poets, musicians and lmmakers primarily from Alaska, British Columbia and the West Coast, but this year’s gathering in February drew attendees from Idaho, Hawaii and Connecticut.

e gathering features prose and poetic readings, jam sessions, lm screenings and other entertainment from more than 100 commercial shing artists who present in more than a dozen popular venues around town.

Seitz recites his rhymes at FisherPoets each year. As for his muse, most of that comes from long stints in the wheelhouse at sea.

“It seems like it starts coming better when you’ve been up for 24 hours,” he says.

Like others who attend or support the weekend poetry slam, Seitz hopes that the gathering will reinvigorate commercial shing’s presence in the ever-changing demographics of Astoria. In a generation that no longer hangs out in waterfront co ee shops but chugs Red Bull and where waterfront property values have soared from competing interests among residential

developers rather than the shing industry Seitz and a few friends have tried to maintain a piscine presence about the town.

Among e orts they’ve written letters urging community leaders for the preservation of waterfront land for commercial shing ventures.

Other campaigns have been more subversive. While the barrels of

Astoria’s yore contained salted salmon the four that have been lashed down on the ying bridge of the South Bay have been lled with whiskey.

Two hundred gallons of it.

Seitz hopes that the single malt brew sloshing around in the oaken barrels will do its share to link local sheries to Astoria’s contemporary culture.

“ ere are microbreweries here now,” says Seitz. ere’s also Pilot House Distilling, which produces gin, vodka and “Hell or High Water,” a premium grade whiskey with a label denoting that Seitz’s boat, the South Bay, has aged that whiskey for a year at sea.

“We take it out shing. A year at sea will make it taste like a 30-year-old whiskey,” he says. “ e motion keeps the sediment stirred up, keeps the barrel moist, and they say that it will absorb the salt air through the oak barrel.”

Seitz’s says that his wife Ti ani attests that the whiskey is “exceptionally smooth.”

“I think stu like that ultimately helps us in the shing business,” says Seitz. “We have to present a more visible presence if we’re going to survive.”

But that’s only part of the Seitz strategy in promoting Astoria as a shing town. e couple opened a family-owned restaurant, the South Bay Wild Fishhouse, in 2017. Rob, Ti ani, their sons and daughters, Gentry Milhiser, Isabelle and James Seitz, (32, 26 and 22 years old), not only haul sh aboard the South Bay but tend to the kitchen and tables.

ough you won’t see as many shermen and loggers along Astoria’s weathered sidewalks and in local shops as when Seitz rst moved there, he and his friends will continue to maintain the port’s shing as a traditional way of life.

“It’s changed a lot,” he says. “But I remain optimistic.”

BY PAUL MOLYNEAUX

BY PAUL MOLYNEAUX

When cotton was king in the South, wooden boats built in Maine carried the crop to the mills of England. Now that scallops and lobsters are the kings of New England and Mid-Atlantic sheries, many of the boats for these sheries are being built of steel in the South.