7 minute read

HEART IN THE DARKNESS Bill Henson, who released new works of a pre-pandemic Rome during lockdown, talks isolation and artistic process

HEART IN THE DARKNESS

Bill Henson released new works of a pre-pandemic Rome during lockdown. He talks isolation and artistic process with Sophie Tedmanson.

Advertisement

You recently unveiled a series of new works on Instagram, including one that was a decade in the making. Was it a coincidence these were finished during the COVID-19 crisis, or was their completion inspired in isolation?

It was a partial coincidence although my project manager Lily, who manages the Instagram account, made the suggestion that we put up a new work every day for a week. Normally she selects a particular work and puts something up every few weeks. I never know what it will be as I don’t have a personal Instagram account. At this time, however, as access to physical galleries has been curtailed, I thought it was an interesting idea. I spend a lot of time just staring at my work and it can take years for me to understand how or why an image matters, remains interesting or perhaps even becomes compelling. It’s only through the process of working that the things that really matter are revealed to you and so those extended dates attached to particular pictures are not unusual for me.

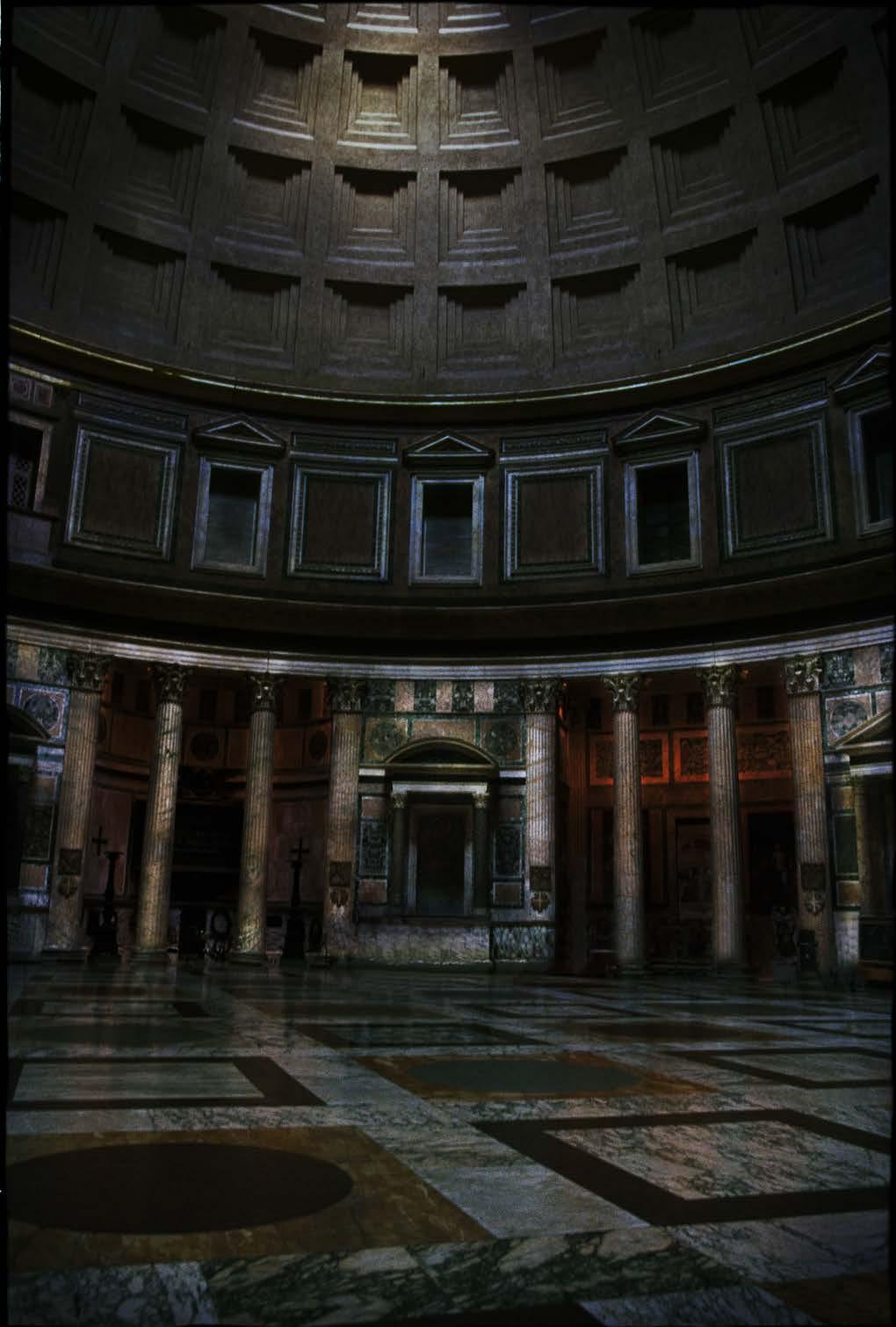

You captioned the Pantheon image (Untitled 2017-2020), with the quote: “Balance is more important than symmetry”. Tell us more about this composition and approach.

I think that mere symmetry is not enough. We need balance and if you study the Pantheon, as I have for the last 40 years, you start to see an almost organic wholeness that is more a kind of balance, one that comes from centuries of cultural evolution. Airing this picture now was also my vote of confidence in a beleaguered liberal humanism, the age of enlightenment, 800 years of English common law, the individual being more important than the state, the innocence of the citizen until the state proves guilt and Greece (without a slave economy) and Rome (with a slave economy) and for both forming the cradle of the western mind. As for now, despite the common currency of virtue signaling and rampant tokenism, which I consider a form of public lying, the sheer weight of history embodied in something like the Pantheon also continues to out-stare history. It’s a mirror into which a hundred generations have looked, seen themselves and

known who they were. Euro-centricity is one of my many sins but, let’s face it, technologically, we live in a ‘western world’.

The Autumnal-looking morning light in Untitled 2015-2020 is stunning, can you tell us more about this work?

This garden is on the Pincian hill and although within the boundaries of the ancient Sallustian garden, dates mainly from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. There is a melancholy in these places especially with their tatty disintegrating follies most of which date from the nineteenth century Fin de Siecle. In this image there is a glimpse of the hydrochronometer installed in 1873. These gardens are a last gasp of the old European pleasure garden and an echo of a pre-industrial landscape.

These images of Rome capture a mood that is so pertinent, especially given the devastating impact of the pandemic on Italy, yet they originated several years ago. Do you see them differently in light of the current situation?

As the politicians say, ‘never let a good disaster go to waste’. Strangely enough, although the current disaster hasn’t changed the way I see these pictures, it has no doubt heightened the sense of mortality we all share. This is always a good thing – so long as we take the time to listen to our feelings, ‘that great intelligence of the body’ as Nietzsche called it. I’m not sure if these pictures are part of my ‘long goodbye’ to Europe but I’ve always felt acutely the sweetness in a backward glance. Everyone carries their childhood around inside them for the rest of their lives. When you speak of ‘mood’ I think what we’re really talking about is feeling. We need to feel more because meaning comes from feeling, not the other way round. To my mind what informs these pictures, however unsuccessfully, is longing: and longing, as the poets say, is much deeper than love.

You were once quoted saying: “There is a sense of isolation or insulation from the world that occurs when you work alone”. Has the current climate of social distancing had any impact on you or your process?

Not really. Louise (Hearman, Henson’s partner and fellow artist) thinks I’ve been social distancing since birth. To my mind rather, these times can be an unexpected gift, an opportunity to be alone with one’s thoughts and a chance to focus more intently on the beauty and complexity of the world around us. I think the vulnerability one feels at such times might just bring us closer, make us more sensitive, to all sentient beings, to the mystery and beauty of animals and the appalling treatment they receive at our hands, to the devastation wrought on the natural world and what kind of future

this holds. Only a fool could believe that culture is ever outside nature.

COVID-19 has left an enormous impact on many industries. What long term impact do you think this will have on how artists adapt to change?

The nature of that impact would depend upon whether the artists were ‘issues-driven’ in which case everything gets to be new again – that old treadmill – or whether they were more focused on the eternal and determining factors of life on earth. What we feel about love, ageing, beauty, longing, fear, death and so on teaches us individually and collectively much more about our place in the world.

Where and with whom have you been isolating? And what have you been watching / reading / listening to pass the time during this period?

Louise and I both live and work in the same building so in many ways life here goes on relatively unchanged. To commute, I walk downstairs into my studio and just start working, or at least preparing to work. This might mean listening to Celibidache conducting Bruckner’s Symphony No. 8 a couple of hundred times before I do anything to a picture. I never listen to music recreationally. It’s always a very deliberate thing and finding just what I need to hear can take weeks or months so there are long periods of silence too. I was feeling kinda 70s the other day and spent some time listening to how great a time capsule Karen Carpenter’s beautiful voice remains. I’ve been dipping into three great writers recently: the sublime Violet Paget, long-dead and mostly out of print and two superb contemporary writers, Katie Roiphe, with whom I briefly corresponded, and the indomitable Camille Paglia. As I get older I find less interest in moving images but objects become evermore important. In fact, the fate of the (art) object in the twentieth century seems increasingly frought as the white noise of constant activity makes contemplation, which relies on stillness and silence, as do objects for their power, less and less possible. I did recently revisit the spellbinding Syberberg masterpiece Ludwig: Requiem For a Virgin King. Strange and ambitious in the same way as is Fassbinder’s Berlin Alexanderplatz.

Your work captures the light and dark of beauty in the world. Do you think our relationship to landscape and the environment will change when we emerge from this period of slowing down in isolation?

I would like to think we have had this unexpected opportunity to pause and reflect on the delicacy and beauty of nature, the weather – that most universal conditioner of life on earth as poet Peter Schjeldhal described it – the fading Autumn light at present and the teeming yet fragile life-forms other than ourselves.

How would you like to see the world change when we emerge from this?

We need to become more sensitive to those things I’ve described above. Empathy, which the best art animates in us all, is the key. When we put ourselves in the place of another sentient being we soon start to see the true consequences of our actions for what they are. Indeed, for me art is the highest form of education because it is profoundly empathetic and at it’s best it always recommends the truth. As Plato said, ‘beauty is the splendor of truth’.

What are your plans for when we can get out of isolation? What are you working on next?

Simply to be true to myself and to keep working. As Oscar Wilde said ‘you should always try to be yourself because everyone else is taken’. ■

Above: Bill Henson, Untitled 2015–20 CL SH849 N18 2015–20. Archival inkjet pigment print. © Bill Henson. Courtesy of Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney and Tolarno Galleries, Melbourne Page 20: Bill Henson, Untitled 2017–2020. © Bill Henson. Courtesy of Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney and Tolarno Galleries, Melbourne