NORTH BY

Donor deficit

Through advocacy and drives, Northwestern’s University Blood Initiative chapter aims to combat the national blood shortage. | pg. 29

The Pioneer

How Chris Collins transformed Northwestern basketball. | pg. 38

Donor deficit

Through advocacy and drives, Northwestern’s University Blood Initiative chapter aims to combat the national blood shortage. | pg. 29

The Pioneer

How Chris Collins transformed Northwestern basketball. | pg. 38

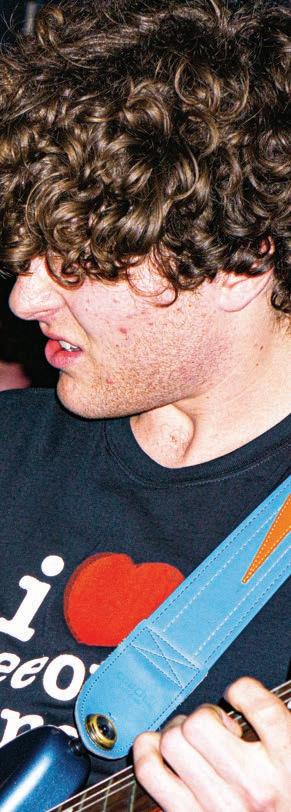

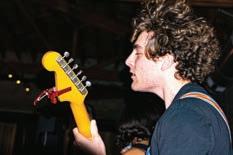

Rock out with Northwestern’s graduating bands.| pg. 50

PRINT MANAGING EDITOR Audrey Hettleman

ASSISTANT MANAGING EDITOR Katie Keil

EDITORS-AT-LARGE Jimmy He, Julianna Zitron

COPY CHIEF Jenna Anderson

SENIOR PREGAME EDITORS Indra Dalaisaikhan, Sarah Lin, David Sun

ASSISTANT PREGAME EDITORS Jessica Chen, Gabby Shell

SENIOR DANCE FLOOR EDITORS Jenna Amusin, Maya Krainc, Sarah Lonser, Mitra Nourbakhsh

ASSISTANT DANCE FLOOR EDITORS Eleanor Bergstein, Sarah Serota

SENIOR FEATURES EDITORS Sam Bull, Emma Chiu, Noah Coyle, Andrew Katz

ASSISTANT FEATURES EDITOR Shae Lake

SENIOR HANGOVER EDITORS Mya Copeland, Bennie Goldfarb, Natalia Zadeh

CREATIVE DIRECTOR Allison Kim

ASSISTANT CREATIVE DIRECTOR Jessica Chen

DESIGNERS & ILLUSTRATORS Grace Chang, Leila Dhawan, Bennie Goldfarb, Iliana Garner, Laura Horne, Abigail Lev, Sammi Li, Heidi Schmid, Xiaotian Shangguan, Jackson Spenner, Allen You

PHOTOGRAPHERS Bennie Goldfarb, Elisa Huang, Joyce Huang, Elena Lu, Angeli Mittal, Julia Lucas, Sarah Serota, Lavanya Subramanian, Allen You

FREELANCERS

Mila Brandson, Hannah Cole, Leila Dhawan, Yong-Yu Huang, Zoe Kulick, Jackie Li, Stephanie Markowitz

COVER DESIGN BY ALLISON KIM

COVER PHOTO BY ALLEN YOU

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Christine Mao

EXECUTIVE EDITORS Conner Dejecacion, Astry Rodriguez

MANAGING EDITORS Mya Copeland, Ava Hoelscher, Sammi Li

ASSISTANT MANAGING EDITOR Gideon Pardo

DIVERSITY, EQUITY AND INCLUSION EDITORS Sammi Li, Yasmin Mustefa

NEWS EDITOR Ayse Ozturk

POLITICS EDITOR Jezel Martinez

ASSISTANT POLITICS EDITOR Rafaela Jinich

ENTERTAINMENT EDITOR Ariel Gurevich

LIFE & STYLE EDITOR Chloe Que

SPORTS EDITOR AJ Anderson

ASSISTANT SPORTS EDITOR Mariana Bermudez

INTERACTIVES EDITOR Manu Deva

ASSISTANT INTERACTIVES EDITOR Annabelle Sole

FEATURES EDITORS Darya Tadlaoui, Sara Xu

ASSISTANT FEATURES EDITOR Yong-Yu Huang

OPINION EDITOR Mya Copeland

CREATIVE WRITING EDITOR Jillian Moore

AUDIO & VIDEO EDITORS Jessie Chen, Indra Dalaisaikhan

ASSISTANT AUDIO & VIDEO EDITOR Dallas Thurman

PHOTO EDITORS Elisa Huang, Yujin Tatar

GRAPHICS EDITOR Rachel Yoon

ASSISTANT GRAPHICS EDITORS June Woo, Diane Zhao

SOCIAL MEDIA EDITORS

INSTAGRAM EDITORS Ashley Kim, Sara Xu

TIKTOK EDITORS Ashley Kim, Sara Xu

TWITTER EDITOR Katie Tsang

PUBLISHER Stephania Kontopanos

AD SALES TEAM Indra Dalaisaikhan, Leila Dhawan, Jackson Spenner, David Sun, Judy Zeng

EVENTS CHAIR Grace Chang

DIRECTOR OF ALUMNI RELATIONS Jessica Chen

For many, spring signifies a period of rebirth and growth. As flowers and trees bloom, bunnies, squirrels, robins and hammocks have overtaken the Northwestern campus.

During Spring Quarter, North by Northwestern magazine blossomed from a series of pitches and sketches to a 64-page edition. Week after week, our editors resisted the temptation to enjoy the warm weather, choosing instead to devote hours to exploring niche corners of our community.

Our Pregame section takes you behind the scenes of the annual UNITY fashion show and meets the Northwestern Formula Racing team at the finish line of race car construction. In Dance Floor, we go back in time through an archival retrospective on Northwestern women’s athletics and a professor’s material history laboratory.

In Features, we talk to musicians taming performance anxiety with beta blockers and investigate a growing trend of political disillusionment among college students. We also look into men’s basketball head coach Chris Collins’s past, present and future — and basketball legend Coach K weighs in. Our cover story, “The farewell tour,” highlights student bands and their senior performers who make time for a creative outlet as graduation looms.

This quarter, I encouraged the staff to expand our reach beyond campus confines. Throughout the issue, you’ll find stories that focus on Evanston, from highlighting a secondhand craft store to examining the Mitchell Museums’s transformative past few years — plus, our Hangover editors reflect on “meaningful” spots across the city.

I have to give my fantastic staff their flowers. This magazine would not have been possible without the hard work and dedication of these editors, designers and writers. I could not have asked for a better group of people to surround myself with this spring.

As you read this magazine, treat each anecdote, source and statistic like its own flower in our community garden, and our magazine as a bountiful bouquet. I hope our coverage encourages you to expand your understanding of Northwestern and Evanston, as it did for me.

Sincerely, Audrey Hettleman

Mixology 101

Campus quitters

RaceCats

Cut and strut

No creativity wasted

NUDM’s new moves

A restorative reimagination

Funding the future

Play like a girl

Digging deeper

Donor deficit

Blocking out the noise

The Pioneer

Disillusioned generation

The farewell tour

XOXO, Chit-chat Wildcat

Unpacking my spiritual baggage

The aquatics center (of attention)

The Hangover Herald

Oh, the places we’ve gone!

Mixology 101

Campus quitters

RaceCats

Cut and strut

06 07 08 10 12

No creativity wasted

WRITTEN

BY

PREGAME EDITORS // DESIGNED BY HEIDI SCHMID // PHOTOS BY ELENA LU

Tired of chugging boring old orange juice, 2% milk and fountain sodas with your meals? Let Pregame help you spice up your feasting experience with recipes for delectable, non-alcoholic drinks you can mix in the dining halls.

• 1/2 cup apple juice

• 1/4 cup orange juice

• 1/4 cup cranberry juice

• Splash of 2% milk

• 1/2 cup Sprite

• 1/2 cup lemonade

• Splash of soy milk

• Ice

Spending too much money on Ume Tea? Learn how to make your own on a budget at Plex! Hong Kong-style milk tea is known for its smooth texture and strong flavor from carefully steeped and pulled tea leaves. You can recreate this iconic drink in less than five minutes — just don’t let your pasta-stirring stick boil!

I haven’t had a Pink Drink since middle school, so if you’re a devotee to the original Starbucks version, don’t come for me. That being said, I think this is a pretty good knockoff of the real thing.

Adding ice and Special K strawberries (without the cereal) is optional.

Rise and shine with a Sunrise Sparkle as you trudge into Allison for your mid-afternoon breakfast! As you sip and savor the refreshing taste, allow yourself to be transported to a place as distant as your memories from last night. Remember: When life hands you a tequila sunrise, turn it into a Sunrise Sparkle and face the day with a smile — or at least a slightly less painful grimace. Cheers!

Adding lemon wedges and mandarin oranges is optional.

Smooth and creamy, this Milkis knockoff tastes exactly like childhood with a fizzy kick of motherly disapproval. Although I’m now a fullfledged adult who can eat as many sweets as I want, I’m forced to treat myself to the dining hall alternative. A single can of Milkis retails for far too much for far too little liquid (screw you, inflation).

Some people like to start their day with a blend of spinach, cucumbers and avocados. Frankly, that’s nasty. This drink gives off the same impression: You’re a young adult who’s on top of their game — healthy, thriving and glowing. Despite the unruly sugar content, this green juice alternative doesn’t taste too sweet and has a refreshing, citrusy aroma.

• 3/4 cup

Bigelow’s English Breakfast Tea (tea bags)

• 1 sugar packet

• 1/4 cup half-and-half

• Plex East ice cream

• 1/3 cup cranberry juice

• 1/3 cup Sprite

• 1/3 cup orange juice

• Ice

• 1/3 cup

Coca-Cola

• 1/3 cup Sprite

• 1/3 cup Powerade

• Ice

WRITTEN BY

HANNAH COLE // DESIGNED

BY

SAMMI LI

Have you ever showered in Mudd Library on hour 17 of midterm studying and thought, “This is rock bottom, should I drop out of Northwestern?” If this has crossed your mind, you are in good company.

According to Forbes, over 1 million people drop out of college each year. However, leaving college does not prevent former students from reaching success. Take a look at these famous Northwestern dropouts who broke the mold, avoided a career in consulting and made the most of their talents (and for some, their nepo baby status).

Model Cindy Crawford attended Northwestern in 1984. After graduating as valedictorian of DeKalb High School in Illinois, Crawford planned to study chemical engineering.

However, she had already found her start in modeling. In fact, according to The Daily Northwestern, she spent her first midterm exam period modeling in Jamaica. The engineer-in-training

dropped out after three months, struggling to juggle her burgeoning career and college life.

“After you have been out on your own and attended black-tie affairs, it’s difficult to go back to kegs in bathtubs,” Crawford said in an interview with The Daily in 1988.

Despite dropping out, Crawford kept her school spirit alive, dancing among students at Dance Marathon in 1990. The purple pride clearly never fades.

Best known for Bugsy, Bonnie and Clyde and the La La Land versus Moonlight Oscars fiasco in 2017, actor and producer Warren Beatty enrolled at Northwestern in 1955. Beatty was a student in the School of Communication and an active participant in school productions, including the 1956 Waa-Mu Show, Silver

Jubilee, and the musical Fashion ’56. Though Beatty left in 1957 to pursue acting professionally in New York City, the School of Communication still lists him as a notable alumnus. Even if you drop out, kids, Northwestern might still use your name to boost its fame.

ZOOEY DESCHANEL

Like Crawford, Zooey Deschanel began her rise to stardom before setting foot in Evanston. In her senior year of high school, she debuted in the movie Mumford alongside Martin Short. She joined Northwestern as a theatre major in 1998 and lived in 1835 Hinman, the eventual COVID-19 quarantine dorm.

While other students enjoyed downtime between quarters, Deschanel devoted herself to auditions. Her hard

work — and perhaps her Oscar-nominated dad and actress mom — paid off when Deschanel was cast in the 2000 comedy-drama Almost Famous

After starring in New Girl and dating a Property Brother, it’s safe to say Deschanel found success, even without a Northwestern degree.

Actress Maude Apatow briefly attended the School of Communication from 2016-2018. Apatow’s mom, actress Leslie Mann, discussed her daughter’s decision on The Late Show with Northwestern alum Stephen Colbert.

“It was really hard being in the cold. You know, she’s a California girl,” Mann said.

I guess no one ever told Apatow the

Chicago summers are worth it.

Apatow officially dropped out in 2018 after landing a role as Lexi in Euphoria. She abandoned fraternity parties and her theatre degree for the greater good: entertaining Northwestern students every Euphoria Sunday in 2022.

If that research paper or final exam is your last straw, do not fret! You can always say sayonara to Northwestern and join this list of famous alumni dropouts. Just make sure you have a groundbreaking movie, TV show, modeling gig or healthy trust fund lined up.

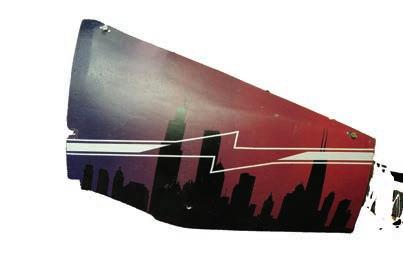

Take a pit stop with Northwestern Formula Racing.

WRITTEN BY JACKIE LI // DESIGNED BY XIAOTIAN SHANGGUAN // PHOTOS BY JOYCE HUANG

Lively chatter fades into silence as the design studio’s monitor flickers on, drawing the attention of the room’s 50-some occupants. Seated at round tables with notebooks, laptops and safety goggles on standby, the members of Northwestern Formula Racing set their eyes on the weekly meeting’s slide deck. Their collective goal is a hefty one: building a winning car for one of the largest intercollegiate engineering competitions in the nation.

One of three automotive engineering clubs on campus, Northwestern Formula Racing takes part in Formula SAE, an annual design competition hosted by the Society of Automotive Engineers featuring college teams’ efforts to make the best high-performance, low-cost,

Formula-style race car. After a year of preparation, the competition is held in May for teams competing in the internal combustion (IC) category and June for teams competing in the electric vehicle (EV) category.

Led by Chief Engineer and McCormick fourth-year Isabella Menendez, the Northwestern team is in its second year of participating in the EV category, requiring a car powered by a rechargeable battery rather than fuel.

“It came alive … [and] everything that I had done that year came into fruition. It didn’t matter if the car drove or not. I could hear that thing moving.”

Their transition from IC to EV was made after a series of engine failures and other setbacks during COVID-19, Aerodynamics Lead and McCormick fourth-year Marina Hutzler says.

“At that point, some of the knowledge of the internal combustion car was leaving with the people who are graduating,” Hutzler says. “That’s when we decided: If that knowledge is already leaving and we’ve had all these issues in the past, let’s switch to EV. Let’s follow the trend of the industry as a whole.”

Team members spend many late nights worrying over faulty engines, unresponsive sponsors and cramming to pull everything together for a test drive in the first week of May, which Menendez says creates community. According to Project Manager and Medill third-year Skye Garcia, the relationships forged from these difficult times hold the club accountable and push for greater progress.

“We all have the same common goal that links us together, which is moving the car, having people drive the car at the end of the year [and] building something that we’re proud of,” Garcia says.

Success in their competitions is just one concern. The other challenge for the club members is balancing the organization and their academics.

Northwestern Formula Racing can be a massive time commitment for some, but others use it as a learning opportunity. McCormick second-year Danish Galebotswe says his experiences in the club have greatly assisted his understanding of concepts taught in class. Upperclassmen from Formula have also made themselves available to help underclassmen like Galebotswe with their introductory engineering and math courses.

Northwestern Formula Racing’s impact also extends beyond workshops and classrooms. The club has been crucial in the job search, especially for Hutzler,

an avid fan of Formula 1. With the help of her Northwestern Formula Racing credentials, she received the opportunity to work with the Alpine Formula 1 Team during her gap year, where she got hands-on experience learning with professional formula cars, analyzing their aerodynamics and company operations.

One major transition the team has made in recent years is a push for inclusive leadership. In its 18 years of existence, Northwestern Formula Racing’s 2024 executive board is the first to see a female-identifying chief engineer. For Menendez, this accomplishment, though slightly overdue, has been deeply fulfilling and insightful.

Menendez remarks that being a woman in a historically male-dominated space has taught her to “be loud and clear” in advocating for herself — a skill she also hopes to pass down to future female leaders of the club.

In addition to Menendez’s efforts as an executive board leader, many general members have made their own efforts to promote gender diversity within Northwestern Formula Racing while pushing for change in the broader field.

As program director of Northwestern’s Society of Women Engineers (SWE), McCormick second-year Liza Kalika facilitated a cross-club collaboration, giving around 10 women the opportunity to get hands-on experience with important machinery in the Ford Motor Company Engineering Design Center’s workshop.

“The Formula girls taught the SWE members how to use the mill and the laser cutter. We made these wooden coasters, and we laser cut ‘gaslight, gatekeep, girlboss’ on them with little flowers. It was super cute,” Kalika says.

Despite the change, Northwestern Formula Racing remains the same club at its core. In particular, there is a shared passion that keeps members glued together, which Garcia sees as a result of experiencing the final product. The feeling of turning the engine on and seeing the success of her creation fall into place in front of her eyes was the most memorable experience for Garcia in her freshman days.

“The whole year, the engine is silent. You don’t hear anything. But they turn it on, and there’s this roar in the autobay. It was huge, it was loud, it was crazy — and I had worked on that,” Garcia says of the IC car. “It came alive … [and] everything that I had done that year came into fruition. It didn’t matter if the car drove or not. I could hear that thing moving.”

Your backstage pass to UNITY’s annual fashion show. WRITTEN, DESIGNED AND PHOTOGRAPHED BY LEILA DHAWAN

spotlight hits the empty runway, illuminating the dark room. Friends, professors and designers go silent as they turn their heads in unison, awaiting the first model.

Communication fourthyear Allison Brook struts into the light with perfect posture and strikes a pose. Every eye in the room is glued to Brook and her outfit: a hot pink two-piece set constructed entirely out of bow ties. Applause and gasps echo through the space. Cameras flash. Designer Aria Carter sits in the front row, beaming as her design comes to life on the runway.

Carter is a client of Arts of Life, an organization that provides a creative outlet for individuals with intellectual and physical disabilities in the Chicago area. Last year, she watched her dreams become a reality through Northwestern University’s premier charity fashion organization, UNITY. All proceeds of the show support Arts of Life, UNITY's charity partner. UNITY puts creativity and inclusivity at center stage in various workshops and speaker events. Most notably, it holds an annual, student-run charity fashion show featuring Chicago designers. Designers and models in the club collaborate to bring unique pieces to life, working from mood boards and sketches to the final garments.

“What UNITY does is very special because it creates a fashion-specific space where students can learn about fashion, about fashion careers and how to take something from a side hobby to something they do seriously,” Creative Director and Weinberg fourth-year Yolanda Chen says.

Chen and other members host sewing, design and modeling workshops to teach incoming members how to make clothes and show them off. Chen says sharing her love for fashion design is her favorite part of UNITY.

“It really makes everything I do for UNITY worth it when I see that they managed to go from a student at a school with no fashion program to full-fledged designers,” she says.

After learning the basics of garment

“It really makes everything I do for UNITY worth it when I see that they managed to go from a student at a school with no fashion program to full-fledged designers.”

Yolanda Chen Weinberg fourth-year

making, designers coordinate with the models to generate ideas and patterns for the show. The models submit mood boards of what they like to wear to guarantee they feel comfortable on the runway. Based on those boards, the designers create a series of outfit sketches, which they later discuss with the models.

Active communication, organization and empathy are key aspects of UNITY’s design process, Chen says. These elements ensure the clothing team stays motivated throughout production and creates designs in a timely and efficient manner. UNITY has grown significantly in recent years. Executive Director and SESP fourth-year Anthony Engle has watched the club return to life after the 2020 show, hosted on Zoom. Since the pandemic, UNITY has grown from a team of 10 to 50.

“UNITY is special as it serves as an informal fashion department for a school that lacks one,” Engle says. “If you want to learn anything about fashion, you’re

not doing it at a Northwestern class, you’re doing it in UNITY or STITCH.”

UNITY provides the opportunity for students to try something new as well as resources for less-established designers to showcase their visions on a professional runway. This year, the club is introducing a line of clothing designed entirely by UNITY members. Chen says the UNITY line prioritizes inclusivity through the collaboration of both models and designers.

“By creating a UNITY line where every single model gets a custom piece designed for them, we are ensuring size diversity,” Chen says. “We are ensuring that models get a say in the creative process and they are wearing something that represents them rather than being a glorified hanger.”

The money raised through charity events and the annual fashion show allows Arts of Life to provide materials and a space for those in institutionalized care homes to express themselves through art. Over 40% of Arts of Life’s funding comes from fundraising sources, such as the UNITY Fashion Show.

Also, it’s often expensive to enter a fashion show as a designer. The registration fee for Chicago FashionBar Week, an annual fashion event in Chicago, is $300 — not including the cost of materials, models

and time. UNITY provides a unique opportunity for aspiring Northwestern and Chicago-area designers to showcase their work professionally for free.

“Having the opportunity to be in a UNITY show means having the opportunity to have professional photography,” Chen says. “You don’t have to hire models, you get to see your clothes on a runway setting as opposed to just on a mannequin, so I think it’s a great deal.”

Engle and Chen hope UNITY will continue growing and empowering creative minds at Northwestern and around Chicago as they prepare to graduate.

“These students inspire me so much,” Chen says. “They are all so busy, but they still take the time out of their day to do something creative that they are passionate about. Just watching them go from not knowing how to turn on a sewing machine to creating these beautiful and intricate final designs has been so inspiring.”

fternoon sun slants into The WasteShed Evanston, basking an ornate vanity mirror in gold light. The glass reflects the jewelry displayed in front of it –– neatly arranged rows of bracelets, rings and other trinkets. People mill about, rifling through bins of notebooks and soft-cornered postcards. A child picks up an old board game box, shaking it to hear the pieces rattle inside.

From a USSR-made microscope to Japanese ink prints, The WasteShed offers a trove of unexpected inspiration for the Evanston art community. Located at 1245 Hartrey Ave., with a second store in northwest Chicago, the nonprofit focuses on creatively reusing materials.

Emily Prescott, general manager of the Evanston location, first heard of the store when she was a graduate student at The School of the Art Institute of Chicago and joined the organization this year. The full-time team of sales associates — known as “Creative Reuse Specialists” — is relatively small, but there is a steady stream of volunteers, many from Evanston Township High School.

“I like to think that in addition to serving the purpose of getting the community

She describes The WasteShed as “a queer-led safe space” that people with different identities find welcoming. The store’s open concept allows customers to think outside the box. Its walls are decorated with everything from a vintage Madonna poster to framed stock photos from a diner.

“We’re trying to get people to think expansively about what art materials can be,” she says.

Materials from The WasteShed have found their way into the Northwestern arts scene. Communication fourth-year Maelea Tan first visited The WasteShed for a class called “Thrift Aesthetics: The Queer Art of Salvage” in their junior year. Tan, a theatre major, returned to find materials for masquerade masks based on the stages of grief for their senior honors thesis.

WRITTEN

BY

YONG-YU HUANG

DESIGNED BY SAMMI LI

PHOTOS BY ELISA HUANG

for personal creative projects. She often drops off old supplies at the nonprofit in the spirit of reuse.

The WasteShed also provides accessible school supplies for educators with a free section of donated items and a shopwide discount.

“I’ve sourced a bunch of different things: wooden boxes, mesh embroidery fabric, golden statues,” they say. “You name a section of The WasteShed, I’ve probably bought something from it.”

The variety of objects at affordable prices also inspired Evanston resident Wendi Kromash.

Chicago Public Schools teacher Donald Schiek says The WasteShed’s dedication to educators allows his students to access learning materials.

“Our school is a hub for many refugees and other newcomers to Chicago,” he says. “The WasteShed helps fill the backpacks many of our students receive on their first day of school here.”

The WasteShed’s creates value on both the community and the individual level. For Tan, the range of items — from glass stuffed animal eyes to old film photos — makes The WasteShed truly special.

“Each item they have tells a story, and I like that you can use those items in your own stories as well,” Tan says.

NUDM’s new moves

A restorative reimagination Funding the future

Play like a girl

Digging deeper

14 17 19 22 26 29

Donor deficit

Why Northwestern’s largest philanthropy event lost the spotlight — and

what comes next.

WRITTEN BY STEPHANIE MARKOWITZ // DESIGNED BY XIAOTIAN SHANGGUAN

Northwestern Dance Marathon (NUDM) has experienced an identity crisis over the past several years. In 2020, the iconic campus-wide event was canceled, and in 2021, it went virtual due to the COVID-19 pandemic. But instead of simply resuming business as usual, the new NUDM bears little resemblance to its pre-COVID iteration.

Before COVID-19, NUDM was a major part of campus culture, with about 1,650 undergraduates registered annually.

NUDM was also intrinsically tied to Greek Life, as the most zealous and successful teams were usually fraternity-sorority pairs.

“It felt very much about the competition, and less so about the charity,” says Eden Hirschfield (Medill ’22), an alumna sister of Kappa Alpha Theta.

“It was something that was sold to them as a means to bond their pledge class together,” says Max Friedman (Weinberg ’16), an alumnus brother of the Sigma Chi fraternity and former member of the NUDM corporate committee. “It was also promoted as an opportunity to grow the fraternity’s positive impact on the University.”

Sororities incentivized their members to register for NUDM to engage with fraternities, with some even giving housing points for involvement. For many members of Greek Life, participating in NUDM was standard practice. With 40% of freshmen joining Greek Life organizations during the 201920 academic year, NUDM’s overlap with

the Greek Life community ensured that a huge crowd of dancers would be in the tent every year.

The competition between fraternities and sororities, coupled with the $400 fundraising minimum all dancers had to meet to participate, drove up fundraising totals alongside attendance rates. For many participants, this funding came from friends and family.

“I knew people who got their parents to just donate the full $400 upfront to get it out of the way,” Hirschfield says.

To minimize entry barriers, NUDM established collaborations with various organizations that allowed dancers to get donations toward their fundraising goal or points for their teams by attending athletic games and other events.

Furthermore, pre-COVID NUDM was a very intense environment, Max Friedman says.

Once a participant left the tent during the 30 hours, they were not allowed to come back. To register meant committing to staying and participating all the way through. An anonymous ’22 alumnus says they witnessed students being berated by NUDM members or event organizers for taking breaks or asking to leave early.

Hirschfield says she considered backing out of the event when she realized she was going to actually be locked in the tent for 30 hours, but her sorority told her she had to take part. While Max Friedman explains this as a liability issue, Hirschfield says it was an “intrinsic” part of the experience.

“It was a source of pride that it was so strict,” she says. “The attitude was like, if you don’t want to do that, then don’t sign up.”

After years of establishing NUDM’s status as a mainstay of Northwestern culture, the need for major changes caught up with the NUDM team.

This transition was not made any easier by the COVID-19 pandemic, as Northwestern instituted virtual learning just days before NUDM 2020.

“That’s a whole class of students who were about to do [NU]DM but didn’t. Now those students don’t have stories to recount to underclassmen,” Max Friedman says.

His observation denotes a subtler consequence of COVID-19: The virtual years interrupted the organic word-ofmouth from older to younger students.

“If you don’t find out that NUDM is fun until your senior year, it doesn’t matter, because you can’t carry that forward,” Max Friedman says. “You can’t tell stupid stories to the people that haven’t done it yet.”

In 2021, for the first time, Greek Life teams were asked to register under a different name, partially due to pressure from the Abolish NU Greek Life movement. Unaffiliated students were automatically assigned to a general “Northwestern University Team.” For the 2022 edition of NUDM, students were randomly assigned to one of four color teams. In 2023, NUDM’s Dancer Relations team sorted self-selected teams again into one of four color teams to ensure equal sizing while allowing students to register with friends.

When the University re-launched in-person classes after COVID-19, there were only two grades on campus that had ever been to an in-person NUDM. With fewer upperclassmen remaining in Greek Life, younger students were less able to learn about older students’ experiences.

During this period, tensions within NUDM between exec members over Greek Life involvement were relatively low.

“There were no awkward conversations. We all wanted to make [NU]DM a more inclusive and accessible space,” says Medill fourth-year and former Communications Director of NUDM Jenna Friedman.

NUDM did away with the $400 minimum rule in favor of a flexible fundraising system in 2021, even knowing that they would raise less money, Jenna Friedman says. Under this new structure, any student could participate in the event regardless of how much they raised.

“It took COVID to make us rethink how we do things. We wanted to be truly inclusive and campus-wide,” says Weinberg fourth-

year and former Dancer Relations Chair Reese RosenthalSaporito. “There were a lot of misconceptions about what [NU]DM is. It was hard to change the narrative of how people viewed it.”

In addition to the earlier fundraising minimum abolishment, NUDM 2024 transitioned from a 30-hour event to just 15 hours, shifted its venue from the iconic Lakefill tent to Welsh-Ryan Arena and changed its timing from the weekend before Week 10 of Winter Quarter to the first weekend of Spring Quarter in response to a survey they conducted.

“I think the move to Welsh-Ryan was a good choice for the time being,” Medill firstyear and Student Committee member Toby Goldfarb says. “The tent would get sweaty and smelly, it’s easier to take a break, it’s more accessible for those with accommodations and it fits more people.”

The downside of this, Goldfarb says, is that the arena felt empty at times. In addition, being surrounded by empty stadium seats made it hard to motivate people to keep dancing instead of sitting down.

Goldfarb says many first-years were confused about the structure of the event, and Weinberg first-year Kyla Brown noticed the same patterns.

“A lot of my friends were like, ‘I don’t want to be locked in Welsh Ryan all night,’” Brown says. “It helps to know you can leave and come back.” 0 300,000 600,000 900,000 1,200,000 1,500,000 Lorem ipsum Fundraising Total (in dollars)

“It took COVID to make us rethink how we do things. We wanted to be truly inclusive and campus-wide.”

While it may be one thing to set lofty goals of reform and inclusion, it’s another to make them happen and engage students with an unfamiliar event.

“It’s hard to get people on board when things have always been done one way, but it was still important to us to make these changes,” Rosenthal-Saporito says.

In particular, the executive team placed more of an emphasis on student outreach for NUDM 2024.

“The whole exec board format was changed so that multiple positions were dedicated to campus engagement and student life,” says Medill fourth-year and

former Public Relations Chair Callie Morgan.

NUDM 2024 saw the most evolved version of the team structure. Student organizations could register their members as a team, or students could choose to register independently with their undergraduate school.

However, NUDM no longer sees the successful participation and fundraising numbers it had for so many years. To the outside observer, it might seem like NUDM is in decline.

“Past years were discouraging in terms of numbers,” Jenna Friedman says. “It was hard caring so much about something and not really knowing if other people cared.”

While it might not be reflected in the numbers, NUDM has been succeeding in at least one crucial way.

“There were an overwhelming number of freshmen this year,” Jenna Friedman says. “They’re the future of Dance Marathon.”

Because of the increasing popularity among underclassmen, the natural diffusion of NUDM stories previously interrupted by COVID is starting to reanimate.

“It’s all about word of mouth,” Brown says. “Now I’m going to promote it to all my friends next year, because I had a great time.”

In essence, the future of NUDM lies with those who won’t be graduating this June. Goldfarb, for example, will be one of several team members to join a new committee dedicated to reengaging Greek Life.

Yet those preparing to leave Northwestern can still look back at the impact they had on keeping NUDM alive. With one year of a relaunched NUDM already under the belt, the steps are in place to ensure future NUDM successes.

“This year was more than I could have hoped for, in terms of registration and turnout,” Rosenthal-Saporito says. “I’m seeing the shifting momentum, the impact of the changes we’ve made, and I’m really hopeful about future years.”

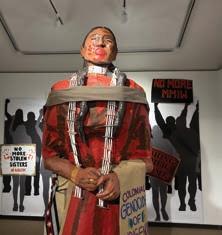

WRITTEN BY SARAH SEROTA // DESIGNED BY HEIDI SCHMID // PHOTOS BY SARAH SEROTA

Athe American Indian, detailed works of Indigenous art and culture fill the regional exhibits, from pottery used in daily life to pieces of turquoise jewelry.

Located about 3 miles west of Northwestern’s campus, the museum has showcased Indigenous history, art and culture to the Evanston community since its founding in 1977 by John and Betty Seabury Mitchell. Yet it was missing a crucial piece: Native American voices. While the museum employed several Indigenous staff, Native American board members were few and far between.

leadership found that some artifacts in its possession were looted from burial sites. Now, the museum is working to return items to Native communities.

“We passed on an eagle staff that we

The structure of the Mitchell Museum underwent a pivotal shift when Kim Vigue, a member of the Oneida Nation of Wisconsin and a descendant of the Menominee Indian Tribe of Wisconsin, joined as executive director in 2021. The composition of the staff and board gradually changed as well, reshaping the organization into a majority-Indigenousrun museum. This marked the start of a broader rebranding process, which officially began two years later.

“It’s like we’re reinventing the museum,” says George Stevenson, vice president of the museum’s board and a member of the Cherokee Nation. “I see this as much more of a change of focus and emphasis in what

museum’s upcoming projects is building an Indigenous medicine garden in partnership with the Chicago Botanic Gardens to make key species of plants accessible for sharing among local Native communities.

“It has to come from the Native perspective,” Vigue says. “If it’s something we purchase or that we sell or any sort of programming, anything that we put out … it has to come from the Native people.”

To gather feedback, the museum sent out surveys and held focus groups for the public to voice their ideas, concerns and thoughts. The responses have “exceeded” the museum’s expectations, Vigue adds, helping determine where and how the museum can grow.

Following abundant community responses, a key tenet of the rebrand is changing the focus of exhibits. Vigue says one of the museum’s goals is to shift the spotlight onto contemporary Native issues, such as missing and murdered Indigenous women. The museum now features a traveling exhibit, No Rest: The Epidemic of Stolen Indigenous Women, Girls, and 2Spirits. Featuring 12 Indigenous artists, the exhibit showcases 35 original works that raise

awareness of “the lack of response when a Native woman, girl or two-spirit individual goes missing or is murdered,” according to the exhibit’s pamphlet.

By highlighting contemporary issues, Vigue hopes to counter a misconception she commonly hears: Native people no longer exist. Vigue says the average person knows little about the tribes indigenous to the Great Lakes areas. To address this, the museum plans to add a Great Lakes contemporary art exhibit focused on topics such as cultural preservation, environmental issues and colonization.

The Mitchell Museum name will also change. Like the rest of the rebrand, the museum’s team is gathering input to determine what this future name will be.

“It circles back to the same issue, and it’s more than Native representation,” Stevenson says. “It’s not just a white man’s museum telling the white man’s story of the Indians, but it’s an Indian-oriented museum telling the Indian story.”

No Rest: The Epidemic of Stolen Indigenous Women, Girls, and 2Spirits.

The museum’s scope is not limited to Indigenous people. The Mitchell Museum also seeks to make Native history increasingly accessible to the wider Evanston and Chicago community.

“It’s an Indian-oriented museum telling the Indian story.”

George Stevenson Vice President of the Mitchell Museum’s board

A new law in Illinois requires public schools to teach students about Native American history starting in the 202425 school year. According to Vigue, the museum hopes to serve as an educational center for the general public and educators where they can ask questions and learn more about Indigenous peoples’ history.

The Associate Director of the Center for Native American and Indigenous Research Pamela Silas, who is of the Menominee Indian Tribe of Wisconsin and a descendant of the Oneida people, shares the hope that the museum will be able to fill an educational gap in the community.

“This is a time to take a look at what [the Mitchell Museum] is capable of,” Silas says.

Silas adds that this growth is neither unnatural nor abrasive. She says the museum is taking its time to sustainably evolve to modern needs and challenges.

“It is a beautiful thing to see this organization responding and adapting to a changing environment,” Silas says. “That’s sustainability.”

The Emerging Scholars Program grants student researchers money and mentorship.

WRITTEN BY MITRA NOURBAKHSH // DESIGNED BY JESSICA CHEN

Weinberg third-year Maddie Kerr was about to do something that would have been unthinkable for them three years ago: present their original research in front of an audience of professionals. They had just flown to Philadelphia for the American Educational Research Association’s annual conference.

Kerr’s journey to Philadelphia was made possible by the Emerging Scholars Program, a funding program from the Office of Undergraduate Research (OUR) meant to make research more accessible to firstgeneration, low-income (FGLI) students or students of color wanting to pursue nonlab-based research projects in fields like journalism, art and social sciences.

Created in 2021, the program provides eight first-year students with 15 months’ worth of research funding: $750 per quarter during the academic year and $4,000 each summer for two summers. It matches students with a faculty mentor and leads them through professional development workshops, building toward an independent research project.

The program’s system of walking participants through the stages from research assistant to independent researcher is a unique model of mentorship that professors and students alike say is undervalued. For Kerr, that process was invaluable.

“I am a very anxious person,” Kerr says. “I don’t think I would have had

without taking over. After some time, Kerr moved on to conducting independent interviews for the project.

Building those skills prepared Kerr to tackle the independent research project they pursued the next summer.

“By the time I was designing my own project and submitting to the [Institutional Review Board] and talking to these people in more of a high-stakes scenario, I felt like I had the experience to not mess up and do damage,” Kerr says.

Shirin Vossoughi, learning sciences professor and an Emerging Scholars Program faculty mentor, says she likes that the program encourages students to form a sustained relationship with a professor who can model best practices for research and engage in “mutual learning and teaching.”

“Sometimes there’s a heavy emphasis on independent research as the only kind of valuable research,” she says. “And there’s some wisdom to that. But I also think there’s value in undergraduate students becoming a part of projects and staying connected with those projects over longer periods of time.”

Vossoughi says she thinks students learning from faculty members before they pursue independent research should be the norm, as it helps them develop a sensibility about what it means to be a thoughtful and ethical researcher.

That model, however, is not generally emphasized. Most students looking to engage in research through OUR apply for a SURG, which allows them to pursue any project of their choice with a faculty sponsor but lacks the prolonged mentorship and research assistantship that Emerging Scholars say they benefit from.

In the 2022-23 school year, 304 students were awarded a SURG while 72 were awarded a research assistantship through the academic year version of the Undergraduate Research Assistant Program (URAP).

The summer version of URAP was canceled last year, as OUR chose to prioritize funding independent research through SURG. Director of the Office of Undergraduate Research Peter Civetta says the decision was made based on a student

focus group in which 62% of the students preferred URGs, 14% preferred URAP and 24% felt they were equal.

Moreover, he says some students might already have the skills to do independent research and therefore wouldn’t benefit from a research assistantship, so OUR would rather fund independent research that surely benefits everyone.

While Kerr had a wonderful experience with their mentor, they may represent a best-case scenario. Bienen fourth-year and Emerging Scholar Olivia Pierce points out that not all faculty have the time to focus on undergraduates.

“You don’t always have someone who can pour into you as a mentor, even if you’re a research assistant,” she says. “There are other ways to get that mentorship.”

After one summer serving as research assistants, it’s time for Emerging Scholars to

work with their mentor and OUR advisors to create a proposal for independent research. The summer after their sophomore year, they begin that research.

Kerr, inspired in part by Bartolome’s work studying music education for children with disabilities, decided to study the experiences of Ph.D. students with chronic illnesses or health conditions.

They conducted hour-long interviews with 16 Ph.D. students and found that these students described feeling a “simultaneous sense of invisibility and hyper-visibility.” With their data, Kerr put together recommendations for how administrators, faculty and institutional leaders could create more inclusive and accessible Ph.D. environments.

This kind of interview- or project-based research is precisely what the Emerging Scholars Program hopes to encourage,

“You’re all there already, and then you just get to learn from each other.”

Civetta says, especially for students who may not know how university research works. Making a documentary, for example, could even be considered research.

An added barrier, he says, is that nonlab research lacks the incentive and infrastructure for faculty members to collaborate with students.

“When I was in graduate school and I was working on my dissertation, it occurred to me exactly zero times to get an undergrad involved in what I did,” says Civetta, who is a theatre professor. “The fact was, it never occurred to me because it’s just not how it works in my field.”

The environment in some non-STEM, non-lab fields can be much more, “I do my work, you do your work,” he says.

The Emerging Scholars Program creates both the infrastructure and the incentive. For Kerr, it also created a community.

“One thing that was really cool about it being directed towards FGLI and underrepresented students is it wasn’t so stigmatized to talk about things like

money and affording apartments and summer housing,” Kerr says. “We could talk to each other about that and it wasn’t weird.”

Kerr has fond memories of going to the Adler Planetarium with other Emerging Scholars that first summer and says it was nice to feel a noncompetitive camaraderie with other students in the program.

“It’s not like you’re vying for one spot,” Kerr says. “You’re all there already, and then you just get to learn from each other.”

Civetta says OUR is not currently looking to expand the Emerging Scholars Program, as one of its assets is the community built through its small cohort of students.

The program was originally funded by a $300,000 grant from the Arthur Davis Vining Foundation, but since then, Northwestern has added it to its undergraduate research grant repertoire and is fully funding the program itself.

For its small size, the Emerging Scholars Program has seen disproportionately large success. SESP third-year and Emerging Scholar Kaylyn Ahn won the top overall poster presentation at the 2023 Undergraduate Research and Arts Exposition, where three of the other seven top poster awards were also given to Emerging Scholars.

As Kerr was on the plane to Philadelphia, Bartolome expressed how proud she was of them.

“They’re going to present their project at the American Educational Research Association Conference,” Bartolome says. “A full-on presentation at a conference, as a junior in college.”

In the last three years, Kerr has gone from someone who didn’t really know what research was to wanting to pursue a Ph.D. in sociology — thanks, they say, to the program.

“If the Emerging Scholars Program didn’t exist,” Kerr says, “I don’t think I would have been able to do the things I’ve been able to do with my research.”

WRITTEN

DESIGNED

BY

BY

ELEANOR BERGSTEIN

ILIANA GARNER

PHOTOS FROM UNIVERSITY ARCHIVES

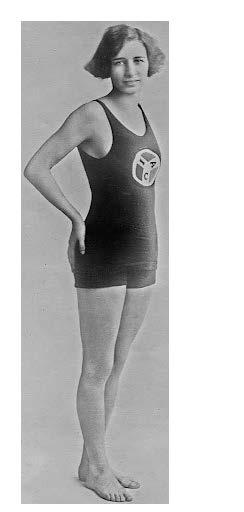

Northwestern’s first-ever basketball game was played by an allfemale team in front of an allfemale crowd.

The year was 1898, and the women who introduced the sport to the University were attempting to make up for their lack of physical education.

In their inaugural season, the group organized several games against local schools and tried to convince more women to join their initiative.

“Everyone who saw the game was delighted beyond measure, and made a resolution to attend every game of basket-ball which is scheduled,” reported an article in The Northwestern after a victory that year.

Over a century later, Northwestern is home to some of the nation’s best women’s sports teams. In the past four years alone, female athletes have brought home two national championships (lacrosse and field hockey) and several Big Ten titles.

As another successful spring season draws to a close, North by Northwestern chronicles the history of women’s sports at Northwestern, highlighting how female athletes have played hard, faced criticism and fought for more than just athletic results.

When Northwestern first admitted female students in 1869, the University’s recommended physical activity for women was a daily 30-minute walk. Most Northwestern women in the mid19th century did not follow this advice, though some participated in recreational sports clubs.

At the turn of the century, Jennie W. Craven wrote in The Daily Northwestern that more people were becoming aware of the importance of women exercising. But she lamented Northwestern women’s lack of interest in physical activity, writing that “a great many are constitutionally lazy, and they are usually hopeless cases.”

While Craven accurately identified a deficit of female participation in physical education, this was not due to a lack of interest. Just two years later, a group of women started the University’s first basketball team.

A student with the initials B.C.S. explained in The Northwestern how the team was formed.

“There are three sides of life, the spiritual and moral, the mental, and the physical,” B.C.S. wrote in 1898. “We girls seemed to be getting a liberal education in the first two, while the third was entirely neglected.”

B.C.S and her friends asked the University for permission to use the gym,

will return every week to play again. The experience has been that any girl who has once been present and has played basket-ball

“

- The Northwestern, 1898

which school officials were “anxious to do so,” she wrote.

The newly formed team played their first game in April 1898 against Austin High School, which was considered the best high school in the nation, and lost 10-2.

When Alice Reiterman scored Northwestern’s only points in the second half, The Northwestern reported “the scene was much like that … when the football team scores.”

Because the team had to keep crowd sizes small due to lack of space,

female crowds. The hope was that female spectators would be inspired to join the sport or invest more in their physical education. B.C.S. thought the plan was working.

“The experience has been that any girl who has once been present and has played basket-ball will return every week to play again,” she wrote.

One female student, Jennie B. Sturgeon, pointed out that the team was “continually handicapped by the lack of the most ordinary facilities” to train and play in. She hoped for more investment from the University.

A 1907 advertisement for women’s athletics.

“Instead of allowing a basketball team to strive without encouragement,” Sturgeon continued, “they will tender it the same hearty support which they give to base-ball or foot-ball.”

On the same page of the newspaper, a concerned letter signed simply “M.” echoed Sturgeon’s desire to promote women’s athletics. In comparing Northwestern to other institutions, M. noted universities with compulsory “gymnasium work” tended to have more women interested in exercise. Northwestern, they wrote, wasn’t doing enough to help female students see the value of physical education.

“A great deal is expected of [women] in the classroom, and in their ‘zeal’ for knowledge, they ‘plug’ away on something that gives them ‘credit’ and forget that one side of their nature is left entirely undeveloped,” M. wrote. “This evil … is best remedied from headquarters.”

Around the turn of the century, The Daily reported that more women were beginning to use Northwestern’s gym facilities. A March 1900 article described Warming up

how a dumbbell class started for female students had generated so much interest that more weights had to be ordered.

The completion of Patten Gymnasium in 1910 created more opportunities for female physical activity. In the 1910-11 school year, Northwestern required physical education for female students for the first time. That year, over 300 women learned to swim.

Around the same time, students formed a Women’s Athletic Association (WAA). The association, which charged 50 cents for membership, created the University’s first women’s field hockey, fencing and indoor baseball teams. Membership included the right to play for any teams in the association, plus half off every football ticket. Every Wednesday was also “Sandwich Day,” when students made and sold sandwiches to raise money for the WAA treasury.

Despite the popularity of the WAA, these student-led organizations were prohibited from intercollegiate competitions. The official stance of organizations like the National Amateur Athletic Federation — and a widely held view at the time — was that women were unfit for athletic competition. The Olympics had only started allowing

women to compete a decade earlier, in 1900.

On the Olympic stage, Northwestern women were some of the early victors for Team USA.

Sybil Bauer was a Northwestern second-year in 1924 when she swam in the Paris Olympics. When she won the gold medal in the 100-meter backstroke, she became the first Wildcat to win an Olympic event. Back at school, Bauer also played field hockey and basketball. She was the first woman inducted into Northwestern’s Athletic Hall of Fame.

At the time, she held every backstroke world record, from 50 yards to 440 yards, beating the men’s record in the latter. Bauer passed away from cancer before her graduation in 1927.

In 1928, Betty Robinson became the first female winner of the Olympic 100-meter dash at just 16 years old. She went on to attend Northwestern and, while there, suffered injuries in a 1931 plane crash that almost prevented her from walking again. Five years later, she returned to the Olympic stage and won gold again.

Meanwhile, on campus, intramural competition between sororities was taking over the female sports scene. By the 1950s, sorority sisters faced off in field hockey, golf, badminton, bowling, archery, riflery and more, according to Walter Paulison’s 1951 book The Tale of the Wildcats. Yet these teams were still unable to compete against other colleges.

sports included field hockey, tennis, track, volleyball and softball, but did not receive significant media coverage or funding. These teams operated under the Physical Education Department, rather than the Athletic Department that coordinated the men’s teams.

An article in The Daily titled “NU women’s sports deserve aid” highlighted post-Title IX conversations at the University about incorporating women’s sports into the Athletic Department. Some thought legitimizing women’s sports would generate positive publicity. Others pointed out women may be better off not doing things the man’s way.

“The women can do without the illegal recruiting, the tampering with grades, the money handed out under the table,” the article said.

Other arguments against the incorporation suggested women’s sports would not generate

Many successful female athletes, including gold medalists, had attended Northwestern for years. By the 1970s, the school was starting to catch up by providing new opportunities for their female athletes to compete at high levels.

These changes were solidified in 1972 when then-President Richard Nixon signed Title IX into law, requiring educational institutions to provide equal treatment based on sex. In collegiate athletics, this meant equal opportunity to play, along with equal treatment and training conditions.

The passage of Title IX led to the creation of Northwestern’s first official varsity women’s teams. By 1974, women’s varsity

Boys

will be boys,

“ “ and girls will be girls...

- The Daily Northwestern, 1974

In the 1950s, the “bloomers” gave way to new outfits. Female intramural players could be seen in blue jeans and white or gray sweatshirts, or khaki shorts and button-ups, like in this photo of a 1950 tennis class.

enough attendance or that women lacked interest in athletic competition, echoing sentiments from almost a century prior.

At the time, Northwestern’s women’s basketball, volleyball and softball teams shared one set of 15 uniforms. The female athletic budget in 1974 was $17,000, more than double what it had been the year before, but still a fraction of the men’s budget. Some students were indifferent to this disparity.

“Boys will be boys, and girls will be girls, and women’s varsity sports will probably retain a distinct character,” a 1974 Daily article said.

Following rising pressure, the Athletic Department added women’s varsity teams later that year. Northwestern’s official women’s varsity basketball team kicked off its inaugural season in 1975, 77 years after the first basketball game was played at the University.

Six years later, the Big Ten officially adopted women’s sports. Northwestern saw early success, winning the first Big Ten softball title the next year.

Over the following years, Northwestern added golf, soccer and cross country to its

growing roster of women’s varsity teams. These teams often struggled for adequate practice spaces, equipment and funding.

Despite relative growth at the end of the 20th century, female athletes faced harsh criticism and disparities in coverage and professional opportunities.

In 1992, the Big Ten mandated that at least 40% of collegiate athletes must be women by 1997, per Title IX. Critics argued against the mandate, saying more men were interested in playing college sports than women.

But standout female athletes continued to defy expectations. Carri Leto became the first Northwestern female athlete to be drafted by a professional sports team in 2004 when she joined the New York/New Jersey Juggernaut in an early women’s professional softball league.

Leto’s experience was rare. Then-Director of Athletics and Recreation Mark Murphy told Northwestern magazine that “from the female athlete’s perspective, the carrot of becoming a professional isn’t there.”

“They tend to be more concerned about the quality of their education and are participating primarily for personal enhancement,” Murphy said.

Northwestern’s 11 varsity women’s teams have seen far more success in the past 20 years than their male counterparts.

Under the leadership of coach Kelly Amonte Hiller, the winningest coach in NCAA lacrosse history, Northwestern lacrosse has won eight national championships in under two decades, including the 202223 season, and has made the Final Four 14 times. When the team won its first national championship in 2005, it was Northwestern’s first NCAA title in any sport since 1941.

Softball won the Big Ten regular-season championship the past three seasons — 202122, 2022-23 and 2023-24 — their first three-peat since four consecutive titles from 1984-87. Field hockey won the NCAA national championship in 2021 and has been runner-up during

the last two seasons. Women’s tennis has won 15 Big Ten regular season titles and 16 Big Ten tournament championships.

Northwestern women have also taken advantage of growing professional opportunities post-graduation. Women’s soccer has sent several players to the National Women’s Soccer League, including Kayla Sharples (Comm ’19) and Marisa DiGrande (Comm ’19) who now play for Bay FC and Racing Louisville, respectively. More recently, Veronica Burton (Weinberg ’22) was drafted by the Dallas Wings as the seventh overall pick in the 2022 WNBA draft.

The list goes on, as Wildcat women continue to prove their dedication and talent. Female athletics have certainly come a long way since the 1800s, but they continue to face challenges to the legitimacy of their accomplishments.

The women of the 1898 basketball team lacked community investment, adequate facilities and equipment and were prohibited from intercollegiate competitions. Today, female collegiate athletes still face attendance disparities

appreciate our newfound rights, is that we have not been satisfied with gymnasium privileges for two days in a week,” she wrote, “but are already, like

WRITTEN BY DAVID SUN

DESIGNED BY LAURA HORNE

PHOTOS BY LAVANYA SUBRAMANIAN

Around the sterile room, dark mahogany cabinets open a gateway into the past, containing 15,000 artifacts from southwest Nigeria. Yet this is just a small sample — less than 2% — of the objects collected and excavated by professor Akin Ogundiran over his 34 years as an archeologist and African history expert. Relics litter the room’s center table, ranging from small seashells and broken shards of a tobacco pipe to rusted plates and fully preserved religious statues.

The room is part of the Material History Lab, a new space constructed in the basement of Harris Hall late last year as part of Ogundiran’s recruitment to Northwestern. Originally a seminar lounge, this room now allows Ogundiran to investigate material history: the study of objects and the stories imbued in them.

History professor and former department chair Deborah Cohen says the department was delighted to hire Ogundiran, one of the world’s foremost experts in early African history.

“This space was crucial for Ogundiran’s research, and many other faculty were interested in material history,” Cohen says. “It was the perfect opportunity.”

Even before the construction of the lab, Northwestern’s history department has long been distinguished in African history. Established in 1954, the Melville J. Herskovits Library of African Studies at Main Library is the largest separate Africana collection in the world. Now, Ogundiran continues this legacy through his study of material history.

The ultimate goal of history is to understand human experience in time and space. Through the subfield of material history, Ogundiran approaches this by studying how individuals and communities interact with one another through objects, which he says are “intrinsic to our humanity.”

“Material history gives you a new way of seeing the past. It’s a methodological

tool,” Cohen says. “Professor Ogundiran is working with some of the best-preserved evidence that helps answer questions about daily life in Africa.”

Material culture goes beyond studying physical objects. Materiality is also encountered through performance, dance, music, rituals and oral traditions, which all leave unique symbolic imprints.

One topic that Ogundiran has devoted his academic career to studying is the cultural intricacies of the Yoruba people, a West African ethnic group, in the early modern period. The main focus of his

scholarship is how modernity began in Africa.

“Very early on, I realized many parts of Africa did not leave written documents,” Ogundiran says. “Material culture offers an important way to study and understand African past.”

One of Ogundiran’s current focuses is researching the role of women in forming the Oyo Empire, an early modern empire in West Africa.

“I’m doing all this research to make a case on why global history must take Africa seriously,” Ogundiran says.

lab in Harris Hall. Items include an ivory finger ring (left), a bone bracelet (middle) and a wood bottle stopper (right). The artifacts in the lab served a variety of functions for African societies Ogundiran believes the bottle stopper may have been used for an animal skin bottle, for example.

every artifact in the collection. As he holds up broken shards of a pipe, he notes it once held Brazilian tobacco.

“Tobacco was truly the first global commodity,” Ogundiran says. “The entire globe participated in the consumption of this addictive product.”

Ogundiran gently picks up a cowry shell, about the size of his fingernail. He explains that such shells originated from the Maldives and were used as currency across West Africa. They were also exchanged for human cargo. Eventually, cowry shells defined a person’s value, shaping human aspirations regarding wealth and power.

“Studying these cowry shells alone opens doors to explore deep metaphysical, cultural and historical aspects of early African history,” Ogundiran says.

Ogundiran envisions this lab as not only a place where he can conduct his research but also as a space of interdisciplinary collaboration between faculty, researchers and students. One goal of the lab is to retrieve the chemical archives of various artifacts by working with researchers from the Chicago Field Museum. By determining the mineral and elemental compositions of his collection, Ogundiran can pinpoint the movement of people, ideas and objects to specific regions in Africa.

“Without understanding the chemical composition of this glass,” Ogundiran says, pointing to a set of glass beads on the table, “we would not have known that these glass objects were locally produced in West Africa and not imported from the Mediterranean.”

While walking through the lab’s collection, Ogundiran points to a statue of Esu he acquired from a temple in Nigeria. The greenish-gray object towers over the other artifacts, showing a humanoid figure with bulging eyes smoking from a long pipe. “This piece was composed to tell a story about how this local community interacted with the external world,” Ogundiran says.

Ogundiran can offer context on nearly

centuries, such as the fragment of a terracotta face (left), while others come from hundreds of years later, such as the lamp (left) and pot lid (top right) from the 17th and 18th centuries.

By the 11th century, the societies of West Africa were technologically advanced in glass-making, an important component of jewelry-making. In Ogundiran’s example, the higher levels of lime present in the glass result from snail shells containing calcium that were added during the manufacturing process to lower the material’s melting point.

This upcoming school year, Ogundiran is launching his first Leopold Fellowship, which recruits undergraduates to work with him in exploring this intersection between chemistry and history. In the Leopold Fellowship program, students are funded for up to a year to engage in historical research by working on current faculty projects.

“Objects evoke conversation. Students begin to pay attention because they’re touching and feeling history,” Ogundiran says.

Ogundiran’s Fall 2023 first-year seminar class, “Climate Change and Civilizations,” visited the Material History Lab multiple times throughout the quarter.

“We mainly went for fun, and he showed us some of the artifacts he was working with,” Weinberg first-year Maria

Horst says. “My favorite part was when he was showing us these bowls. Each bowl, on the bottom, had a unique potter’s mark.”

Ogundiran explained how historians could use these bowls to learn more about a person’s diet. Using lipid analysis, the pores of the bowl can indicate what people ate out of them.

“It was so impressive and incredibly cool to see the artifacts he brought,” Weinberg first-year Alexandra Haney says. “It was like we were seeing the behind-the-scenes of a museum right here in Harris Hall.”

Ogundiran is currently collaborating with the Office of Media Technology in Main Library to digitize the artifacts using photogrammetry, a technique that extracts 3D information from photographs. Ogundiran hopes these 3D replicas can allow K-12 students to interact with these priceless and fragile objects without damaging them.

“I’m working with Ogundiran to allow his lab to be a [3D] digital archive,” says Craig Stevens, the Northwestern Media and Technology Innovation (MTI) Department’s Innovator in Residence. “Using a traditional camera and taking

hundreds and thousands of photos and then putting them through a software allows for a 3D model to be created.”

Currently, Ogundiran is teaching a history course on drugs and alcohol in Africa, focusing on the transatlantic slave trade.

“West African societies had a surplus of human beings captured via war, and their willingness and motivation for the slave trade was fueled by their addiction to tobacco and alcohol,” Stevens says. “There’s a lot more empathy that can be [gained] by understanding these people.”

Stevens is a Ph.D. student in the anthropology department who works with 3D digitization and augmented and virtual reality visualization.

He and other members of the MTI department have digitized several tobacco pipes in the collection, making them accessible to use in the classroom. Unlike traditional photographs, these objects can be zoomed in on and rotated, and annotations can be added to specific parts of the artifact to streamline the learning process.

“It’s just extremely validating to see [Ogundiran] so established in this field ... and see that what I’m doing could be a contribution to his own goals. It’s the coolest experience as a student,” Stevens says.

For the last two years, MTI has been advocating for faculty to incorporate 3D models and digitization into their courses.

“ There is a lot more empathy that can be [gained]

Craig Stevens Media and Technology Innovation Department’s Innovator in Residence by understanding these people.”

“Our mission is to help Northwestern integrate emerging technologies more into the way that we teach and [conduct] research,” Stevens says. “This project is going to be a great example and motivation for more students, staff and faculty members to think about some of the technologies that we’re passionate about.”

Ogundiran hopes the Material History Lab will serve four dimensions — research, learning, collaboration and outreach — to further the interest and importance of African history.

“The study of African history cannot start with documentary sources,” Ogundiran says. “It must start with material culture.”

Through advocacy and drives, Northwestern’s University Blood Initiative chapter aims to combat the national blood shortage.

WRITTEN BY MILA BRANDSON // DESIGNED BY LEILA DHAWAN

Wblood didn’t go as planned. She finished her session with a bruised arm as volunteers hastily offered her water and snacks.

“I couldn’t go to cheer practice afterward because I was just so dizzy and out of it,” Ong says.

A high school sophomore at the time, Ong barely met the required minimum weight to donate, raising concerns among drive employees about her eligibility. But coming from a family of regular donors, she was eager to participate. She also carries O-negative blood, which people of all blood types can receive.

Although the technicians drawing her blood struggled to find a vein in Ong’s arm and she left feeling lightheaded, Ong returned to her high school’s drive the next year to donate again — and has encouraged others to do so ever since.

Now, Ong is the director of marketing for Northwestern’s University Blood Initiative chapter, where she promotes

encourage college students to donate so they can address the larger-scale challenges of a national blood shortage.

Blood donations are in high demand, as surgeries, cancer treatment, chronic illnesses and traumatic injuries can all require donated blood, according to the American Red Cross. However, the total number of people donating blood through the Red Cross has decreased by 40% over the last 20 years, hitting a record low in January 2024 that led the Red Cross to declare an emergency blood shortage.

The percentage of young adults and teens donating blood has also fallen steadily since 2013, according to the 2021 National Blood Collection and Utilization Survey. From 2019 to 2021, donors aged 16 to 18 decreased by 60.7% and donations from minority races and ethnicities declined by 35.4%.

To address the decrease in donations, outreach by organizations like Northwestern’s University Blood Initiative and private blood collection centers aim to re-energize younger populations. The groups emphasize the importance of diversity in donations to meet the needs of a wider range of patients

requiring transfusions. Greater ethnic diversity in blood collection typically results in a wider array of proteins and structures in the blood supply, and younger people help fill the gap left by older populations as they age out.

Since its founding in 2022, Northwestern’s University Blood Initiative chapter has organized 11 blood drives and collected around 300 units of blood. A single blood donation amounts to one to two units of blood, and one unit can save up to three lives. This means the club has collected enough to help 900 people.

“By having a student-run club that does this, we’re bringing in a new demographic and getting younger people to donate,” says Julien Rentsch, Weinberg fourth-year and founder of Northwestern’s University Blood Initiative chapter.

Rentsch started the chapter after participating in a remote summer internship with the national organization. He says targeting a younger demographic helps introduce individuals to blood donation, creating more lifelong participants.

In its most recent Winter Quarter drive, the student group partnered with Versiti, a private blood donation center. They collected a total of 26 units of blood, enough to assist 78 patients.

“It’s a very direct, health-focused way of contributing to the community,” says Sam Trammell, Weinberg secondyear and president of Northwestern’s University Blood Initiative chapter.

In addition to student groups, private blood collection centers like Vitalant and Versiti partner with community organizations, high schools and universities to run drives.

Phillip Sanfratello, Vitalant’s manager of donor recruitment, says the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 had a “deleterious” impact on donations.

“From March 13 on, our calendar went from having sometimes 10 blood drives a day to having maybe one a week,” Sanfratello says.

Vitalant, which supplies the NorthShore University Health System, John H. Stroger, Jr. Hospital and University of Illinois Hospital & Health Sciences System, aims to collect over 4,500 units of blood per day.

This goal became more difficult to achieve during the COVID-19 lockdowns, as the company was forced to stop collecting blood in high schools and universities.

“There’s just such a high need for blood and a comparatively little amount available for donation.”

Sanfratello says the shutdowns prevented students from seeing their peers donate blood, which often sparks interest among young people who may not have otherwise participated. Maintaining contact with donors as they enter college poses an additional challenge, as many Illinois students attend out-of-state universities.

High school and college students typically make up 20% of Vitalant’s total donations. However, people over the age of 55, primarily Baby Boomers, represent the largest population of loyal donors.

As Boomers become too frail to donate or start to require blood transfusions themselves, blood collected from their generation will likely decrease, creating a need for younger generations to step up.

Since the pandemic, Vitalant has upped its social media presence and educational outreach to recruit younger populations. Ads on Facebook and Instagram have helped promote upcoming collections.

Although the company is hosting inperson blood drives again, Sanfratello says donations are still nowhere near pre-pandemic levels. People can give blood every 56 days, or up to six times a year, but Sanfratello says the average donor in the Chicago market only donates about once a year.

It can be challenging to engage eligible donors at Northwestern and the surrounding Chicago area, Trammell says.

“There’s just such a high need for blood and a comparatively little amount available for donation,” Trammell says.

Many factors determine whether someone is eligible to give blood. Basic donation requirements state donors must be at least 16 years old and over 110 pounds, but travel history, medical records, medications, tattoos and skin piercings, among other factors, can render potential donors ineligible.

Other reasons, like fear of needles or blood, may explain why eligible people choose not to donate.

“Whenever I get blood drawn, I freak out,” Weinberg fourth-year Jack Shurtleff says. “It is always an enormous mental burden.”

Although new donors may be hesitant or nervous, Northwestern’s University Blood Initiative and blood collection centers aim to incentivize donations from

a diverse donor set, since the majority of first-time and regular donors are white, according to a 2021 study published in Blood Transfusion

“The more diversity we have in the blood supply, the better,” Sanfratello says. “Certain proteins in the blood are only found in certain races and ethnicities.”

These proteins and structures in blood can determine whether a person will be able to receive it. For example, Black Americans tend to have higher levels of sickle-cell disease, and patients who carry it need donations of blood similar

Sanfratello says Vitalant has increased outreach to Latine populations, as they often carry higher levels of O and O-negative blood. He adds that Asian American populations typically carry higher levels of B blood types.