An ode to the arts

A look at the 2024 Dittmar Community Art Show — and the people and poetry behind it. | pg. 50

NORTH BY

What is the title of your mixtape?

northwestern WINTER 2024 print

staff web staff

EDITORIAL

MANAGING

PRINT MANAGING

EDITOR Julianna Zitron

ASSISTANT MANAGING EDITOR Audrey Hettleman

COPY CHIEF Jenna Anderson

EDITORS-AT-LARGE Jimmy He, Mia Walvoord

SENIOR FEATURES EDITORS Sam Bull, Emma Chiu, Noah Coyle, Caroline Neal

ASSISTANT FEATURES EDITORS Andrew Katz, Zoe Chao

SENIOR DANCE FLOOR EDITORS Katie Keil, Maya Krainc, Sarah Lonser, Mitra Nourbakhsh, Chloe Rappaport

ASSISTANT DANCE FLOOR EDITOR Jenna Amusin

SENIOR PREGAME EDITORS

Hannah Cole, Indra Dalaisaikhan, Sarah Lin

ASSISTANT PREGAME EDITORS Jessica Chen, David Sun

SENIOR HANGOVER EDITORS Bennie Goldfarb, Julia Lucas

ASSISTANT HANGOVER EDITORS

Mya Copeland, Olivia Kharrazi

CREATIVE

CREATIVE DIRECTOR Grace Chang

ASSISTANT CREATIVE DIRECTOR Allison Kim

DESIGNERS & ILLUSTRATORS Jessica Chen, Bennie Goldfarb, Audrey Hettleman, Laura Horne, Abigail Lev, Sammi Li, Jackson Spenner, Allen You

PHOTOGRAPHERS Alessandra Esquivel, Audrey Hettleman, Elisa Huang, Elena Lu, Lavanya Subramanian

FREELANCE

Eleanor Bergstein, Sela Breen, Zoe Kulick, Esther Lim, Steph Markowitz, Victoria Ryan, Sarah Serota, Jade Thomas

COVER DESIGN BY GRACE CHANG

COVER PHOTO BY AUDREY HETTLEMAN

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Christine Mao

EXECUTIVE EDITOR Conner Dejecacion

MANAGING EDITORS Astry Rodriguez, Olivia Abeyta

ASSISTANT MANAGING EDITORS Sammi Li

Mya Copeland, Ava Hoelscher

DIVERSITY, EQUITY & INCLUSION EDITORS

Sammi Li, Yasmin Mustefa

SECTION EDITORS

NEWS EDITOR Arden Anderson

ASSISTANT NEWS EDITOR Jezel Martinez

POLITICS EDITOR Gideon Pardo

ASSISTANT POLITICS Editor Jerry Wu

ENTERTAINMENT EDITOR Ariel Gurevich

LIFE & STYLE EDITOR Chloe Que

SPORTS EDITORS AJ Anderson, Maggie Rose Baron

INTERACTIVES EDITOR Manu Deva

ASSISTANT INTERACTIVES EDITOR Ava Mandoli

FEATURES EDITORS Sara Xu, Darya Tadlaoui

ASSISTANT FEATURES EDITOR Yong-Yu Huang

OPINION EDITOR Abby Hepner

CREATIVE WRITING EDITOR Jillian Moore

AUDIO & VIDEO EDITORS Jessie Chen, Indra Dalaisaikhan

PHOTOGRAPHY EDITOR Lianna Amoruso

GRAPHICS EDITOR Rachel Yoon

SOCIAL MEDIA EDITORS

INSTAGRAM EDITORS Kim Jao, Sara Xu

TIKTOK EDITORS Jade Thomas, Sara Xu

TWITTER EDITOR Jade Thomas

CORPORATE

PUBLISHER Stephania Kontopanos

AD SALES TEAM Grace Chang, Jessica Chen, Indra Dalaisaikhan, Janice Seong, David Sun, Grace Wang

SPECIAL EVENTS CHAIR Kim Jao

WEBMASTER Ziye Wang

Jay-z’s Jams.

Hetty Wap EP. bootsandkatzandbootsandkatz.

hyperpop mix (dolby atmos stems) (8D audio) (lonely witch version).

The Billboard Thot 100.

The disparaging sounds of an Adobe error pop-up.

It’s really not that bad!

Liked songs.

Choreographed madness.

Hep Tunes by Abby.

Readers, Dear

To an unassuming campus visitor, Winter Quarter may seem like a quiet time. But while the Lakefll and beaches are empty, music still fows from a classroom in Kresge. Students gather in Norris to see the newest art gallery. Fans cheer loudly and proudly for their sports teams from the bleachers. Here’s the thing about this school: There is never a quiet moment on campus.

Even in freezing temperatures and bitter winds, the NBN staf showed up time and time again to put together this issue. They have mused on every word in this magazine and created beautiful designs, highlighting that even when the skies are gray, the Northwestern community is still buzzing.

In our Pregame section, you’ll hear from the students behind the Songwriters Association at Northwestern and how they turned an idea into a collection of entirely student-produced songs. In Dance Floor, we spoke with a religious studies major turned pilot and fight instructor, intimacy coordinators trying to make the student theater and flm safer places and the frst Argentinian Global Rhodes Scholar.

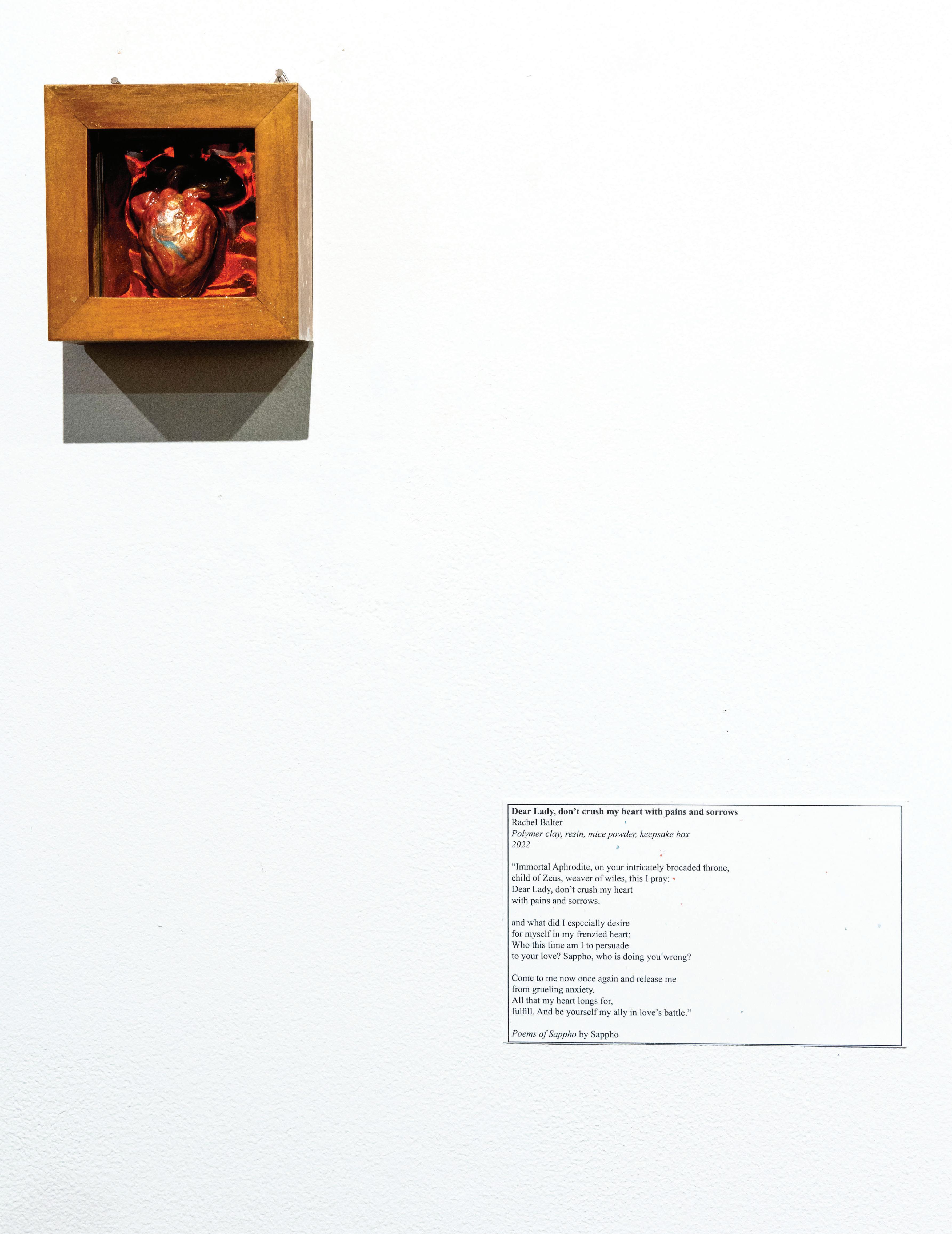

In our Features section, six D-1 student-athletes tell us about how the life of an athlete is not all glitz and glory. Their experiences show the ofen overlooked side of college athletics — the mental and physical stress overshadowed by the cheering fans and record-breaking achievements. Our cover story, “An Ode to the Arts,” goes behind the scenes at the Dittmar Gallery in Norris University Center. Their current exhibition is run entirely by student curators and emerging artists.

We’ll close out our magazine with a guide on how to avoid adopting a foster cat (unsuccessfully) and a raving review of Evanston’s newest, hottest indoor trampoline park in the Hangover section.

This issue would not have been possible without the fantastic staf behind it. The hard work and dedication of these editors, designers and writers is the only reason this magazine you hold in your hands exists. As much as I fnd myself complaining about the cold, creating this magazine helped to remind me of the reasons I chose Northwestern in the frst place — and I hope it does the same for you.

Sincerely,

Julianna Zitron

Beyond the syllabus

Beats by SWAN

From pool to pavement

Level up!

The secret life of campus dogs

A new playbook

Scripting safety

Campus Kitchen

A major switch

A match made in Heavenston?

On the Rhode

Running on empty

Breaking barriers, building futures

Getting down in E-Town

An ode to the arts

Why, Northwestern?

How to break into Spring Break

Hangover goes to Sky Zone

Fostering mental health a cat

Ring by spring

Beyond the syllabus

Need reading recommendations? Take a page out of these professors’ favorites.

WRITTEN BY MITRA NOURBAKHSH

DESIGNED

PHOTOS

BY

BY

JACKSON SPENNER

ALESSANDRA ESQUIVEL

In a quest to fnd Spring Break reading material, NBN asked four professors from across the University for their endorsements. Hopefully, these book recommendations are more entertaining than the hundred-page textbook readings they usually assign.

Daniel Immerwahr

Pale Fire by Vladimir Nabokov

Immerwahr’s all-time favorite book comes with high praise.

“Pale Fire is not only [Nabokov’s] best novel, but the best novel ever written,” he says.

It’s funny. It’s delightful. It’s confusing. And it’s meant to be reread over and over — in Immerwahr’s case, no less than seven times. Pale Fire is a story within a story; it takes the form of a 999-line poem with an introduction,

index and annotations written by a fctional editor whom Immerwahr calls “a little unhinged.”

“You get to the poem, and, interestingly, you can’t tell if it’s good or bad,” he says. “The annotations get increasingly insane, and then this story starts to unfurl.”

Give it a read … or seven. Hopefully, it lives up to Immerwahr’s high praise.

Sara Broaders

Fourth Wing by Rebecca Yarros

For Broaders, it’s hard to choose her all-time favorite book because there’s so many that have shaped her identity.

“It’s like choosing your favorite child,” she says.

But when pressed, Broaders named a recent read she thinks students would enjoy.

Fourth Wing is a fantasy and romance novel about a college quite diferent from Northwestern. Instead of training

future consultants, Basgiath War College trains dragon riders.

Full of action and with Broadersendorsed character development, Fourth Wing tells the tale of a bookish 20-yearold forced to compete for a chance at a life of dragon riding.

“Some books do too much trying to give you too much context. I just think she tells a good story,” Broaders says.

Jules Law

Salvage the Bones by Jesmyn Ward

While it’s not his all-time favorite book ( Tess of the d’Urbervilles takes that spot), nor his favorite contemporary novel ( 2666 gets the honor), Law says Salvage the Bones is easily “one of the greatest novels of the last 20 years” and probably the most compelling to students.

Salvage the Bones tells the gutwrenching story of a coastal Mississippi family during the 12 days leading up to

J.A. Adande

Hurricane Katrina’s landfall. The story is compelling, poetic and visceral.

Law is drawn to novels that illuminate the human condition and grapple with whether behaviors are instinctive or socially conditioned. While his favorite books tend toward the somber, Salvage the Bones defes that pattern.

“It’s depressing and uplifing,” Law says. “Students fnd it really, really powerful.”

The Right Stuff by Tom Wolfe

If you’ve ever wondered whether you have what it takes to be an astronaut, this is the book for you. Spoiler alert: You probably don’t.

The Right Stuf dives into the stories of astronauts and test pilots of the 1940s and ’50s to understand who was brave (or stupid) enough to risk going to outer space.

It is the vividness of Wolfe’s writing that makes this Adande’s favorite book; he remembers being completely engrossed by it during his

“I didn’t know you could write like that, bring it to life and just spend paragraph afer paragraph talking about someone’s hair or the sound of his voice,” he says. “It helped make me want to become a writer. Like, wow, he can make the words jump of the page like that.”

Beats by SWAN

With their second mixtape on the way, the Songwriters Association at Northwestern has songs for everyone.

WRITTEN BY HANNAH COLE // DESIGNED BY ALLISON KIM // PHOTOS BY ELENA LU

Sof sounds of pop, folk and rock foat around a small room in Kresge. Students line up to add songs to the eclectic Spotify queue. From over-the-top, campy music by Chappell Roan to slow, soulful tunes by Hozier, the selection mimics the diverse musical interests of the Songwriters Association at Northwestern (SWAN). While the music plays in the background, the students discuss their upcoming mixtape.

In 2022, SWAN entered the school’s music scene, hoping to provide a comfortable space for songwriters to share their work and collaborate with other musicians and producers. Last summer, the still-emerging group released Swan Song, their frst mixtape composed entirely of student-written and produced music.

The first project included a diverse mix of genres and songs, reflecting

the club participants’ unique interests, styles and experiences with music.

McCormick fourth-year Donovan Batts, a founding member and executive board member of SWAN, considers Swan Song a success because of the broad music styles featured.

“We had some instrumental tracks. We had some heavy metal stuf,” Batts says. “We had some really experimental songs as well — folk, pop, singer-songwriter.”

“We want to lay the groundwork for what this club will look like in future years and leave our legacy.”

Lylajean Bariso Weinberg fourth-year

Afer Swan Song, the club is beginning its second mixtape with a more refned approach, which they hope to release in April. In May, SWAN will give out CDs and host live performances from mixtape contributors at Kresgepalooza, an event that turns Kresge classrooms into “tiny desk” concerts, à la NPR, for musicians to showcase their songs.

Last year, SWAN paired one artist with one producer. Now, they want to make the process more collaborative, Batts says. Rather than working in pairs, students will engage in groups of four to fve people.

The collaborations allow students to improve their work and learn from people with diferent musical backgrounds. Students ofer a range of expertise, from poetry to production to the mastery of numerous instruments. These instruments include, but are not limited to, piano, voice, clarinet, keys, ukulele and guitar. Each person in a collaboration group will use their talents to create an original song.

Members of the club appreciate the collaborative approach because it teaches

them new techniques and aspects of the music-making process. McCormick fourth-year Chealen Berry learned about music production when she contributed to the frst mixtape and worked with student producer and Weinberg fourth-year Joy Fu.

“It was cool to see what she’s been taught,” Berry says. “It was really fun working with her because I got to see the more technical aspect of recording.”

Berry and other artists write and perform their songs, but the producer makes the music come to life.

While Berry previously released music, for some students like Weinberg fourthyear Leslye Molina, the mixtape was their frst opportunity to share their work with the public.

“I’ve always written songs or played stuf on my guitar just for myself. It was my frst time doing something published for other people to hear,” Molina says. “The genre I did was more experimental, electronic techno. I’ve never done that before, and that was really fun to do.”

With the upcoming mixtape, Molina hopes to switch up her sound.

“This time, I’m thinking something different. I’m thinking a little bit more mellow,” Molina says. “Maybe something more pleasing to hear, but still keeping that edge in the lyrics. I’m excited to play around with that.”

Creating music and forming new ideas can prove challenging for club members. Batts says the process starts with a dream or spark of an idea. Students need to discover why they are writing a song or what goal they hope the song accomplishes.

Each student has diferent writing processes, and for people like Batts and Berry, thinking of the initial idea can be the most difcult part.

“I write a song when I have heavy emotions, and I need to express them in some way. That’s where the good ones come from,” Berry says. “I’m not really the type of person who’s always able to just sit down and be like, ‘OK, today I’m writing a song; let’s choose a random topic.’”

Because the songwriting process can be challenging, SWAN is a commitment. The executive board expects students to make headway on their songs throughout the quarter. People must check in with their song groups every week, but most mixtape work occurs outside club times, meaning students must hold themselves accountable.

However, Batts strives to keep the environment comfortable, stress-free and safe for sharing music. SWAN only requires mixtape artists and producers to attend three club meetings, and the club promotes group outings to places like museums and record stores to foster a sense of community.

“We want to make sure the people involved don’t feel stressed at all. It’s not a sixth class. It’s an extracurricular, creative outlet,” Batts says.

SWAN executive member and Weinberg fourth-year Lylajean Bariso says she hopes the mixtape becomes a yearly tradition, ensuring the club provides a platform for self-expression for future students.

“We were such a new club. We want to lay the groundwork for what this club will look like in future years and leave our legacy,” Bariso says.

Berry encourages all artists or producers interested in the process of putting out original music to join SWAN.

“Why not? If you come up with an idea, share it,” Berry says. “Try to fnd a good community where you feel comfortable sharing those ideas because that’ll allow you to develop your songwriting skills and get more feedback.”

Leslye Molina, SWAN member and guitarist in the bank Dark Refections.

Back row (lef to right): Elsa Steen Koppell, Lianna Amoruso, Daniel Martin, Elisa Johnson, Rogelio Munoz-Franco.

Front row (lef to right): Lylajean Bariso, Anna Selina, Ellie Caro, Leslye Molina.

How Northwestern Triathlon Club trains students for success.

WRITTEN BY ANDREW KATZ // DESIGNED BY ABIGAIL LEV

Despite running track in high school and training for months before the event, Weinberg fourthyear Jules Wathieu says his frst triathlon was “traumatic.”

“It was way harder than I expected it to be, especially the transition from biking to running,” Wathieu says. “That was kind of a wake-up call for me … but it feels really good to fnish it even though you don’t get a medal.”

With the sound of a starter pistol, the race is on. Competitors in a standard Olympic-distance race swim the length of over 17 football felds before hopping on their bikes and riding 25 miles. But it does not stop there; the triathlon ends with a 6-mile run.

In February, Northwestern Triathlon Club hosted its own event: the Wildcat Indoor Sprint Triathlon. The race is a fundraiser that helps sponsor the team’s spring trip to the USA Triathlon Collegiate Club National Championships. In the recent indoor triathlon, triathletes competed in a 10-minute swim, 20-minute bike and 15-minute run, vying for the furthest distance.

The club raises money from visiting schools, but the event is entirely free for members. This year’s visitors include the University of Illinois, the University of Chicago, Purdue University, the University of Michigan and Michigan State University.

Gearing up for three diferent sports can be pricey. Weinberg fourth-year and Northwestern Triathlon Club President Aaron Lu’s goal is to make Triathlon as afordable as possible. In addition to free Wildcat Sprint Triathlon entry, the club lends bikes to members and highly subsidizes their costs to attend nationals, including their airfare, hotels and entry fees.

“Our mentality is to promote accessibility, in terms of having as many resources as we can to teach people how to get used to triathlons, but also provide resources for them to compete in the races as well,” Lu says.

Wathieu also emphasizes the club’s commitment to accessibility for less experienced members. Many students join the club not having experience in all three aspects of a triathlon. Team members are divided by skill level during practices so everyone can participate and learn.

Lu was attracted to the club because of the consistent training schedule and the social atmosphere.

“I just think Triathlon attracts a certain type of person,” Lu says. “It’s quite an indescribable quality. … There’s just a collective friendliness on the team.”

SESP second-year Paloma Jourdes serves as the fundraising and alumni relations chair on Triathlon’s executive board. Like Lu, she joined Triathlon Club because she enjoys the social aspect of working out in a group setting and appreciates the club’s consistent training schedule.

To balance classes and schoolwork with rigorous training, she says triathletes must be dedicated, disciplined and careful with their health. This means going to sleep early, eating nutritious foods and not drinking alcohol.

“I am a frm believer that if you do not prepare for the two weeks before, cleanse and hydrate your body, it’s not going to go well,” Jourdes says. “You can’t do that kind of thing hungover.”

For Wathieu, Triathlon Club has meant much more than staying ft and competing.

“Sophomore year was a time when I was feeling a little isolated, and Triathlon made me feel more comfortable and gave me a community.”

Level

UP!

Step into Norris’s new Nexus Gaming Lounge with Northwestern Esports.

WRITTEN BY SARAH LIN // DESIGNED BY JESSICA CHEN

PHOTOS BY LAVANYA SUBRAMANIAN

With two quick taps of the keyboard, the monitor stirs to life. The blue light illuminates Weinberg frst-year Hannah Kwak’s face and refects of her gold-framed glasses. As the game loads, she fts a red headset over her ears, centers the microphone to her mouth and stretches her wrists.

Afer this routine, perfected over dozens of hours spent in the Nexus Gaming Lounge, Kwak is ready to play.

In October 2023, the Nexus Gaming Lounge opened in the Game Room of Norris University Center’s basement. Northwestern Esports and Norris collaborated to build the Lounge, equipped with state-of-the-art gaming monitors, headsets, chairs, keyboards, microphones and its own live-streaming room.

Although any Northwestern student, faculty or staf member is free to use the Lounge, Northwestern Esports occasionally books the space for its fve competitive gaming teams to practice and play matches against other schools. Before the Lounge opened, Northwestern Esports competed virtually but ofen faced connectivity issues.

“People would play from their dorms, sometimes at the mercy of Northwestern Wi-Fi, so it really was like a mixed bag with which people could actually participate in the club’s activities, just because barriers to entry for Esports itself are pretty high,” says Shannon Tan, Esports external vice president and McCormick second-year.

Maintaining functional Wi-Fi and installing high-speed data lines, along with furnishing other amenities, is expensive. According to Norris’s Executive Director Corbin Smyth, the Lounge renovation cost around $150,000.

McCormick second-year Carlos Nueva is on the varsity Valorant team, representing Northwestern in ofcial gaming matches against other Big Ten and regional schools. He says the opportunity to play with all of his teammates in the same space makes for a better gaming environment.

“Whenever we win, we can actually get up, high-fve each other, get hyped and really feel more energy than when we’re of playing separately,” Nueva says.

Kwak also prefers to practice and play with her junior varsity Valorant teammates in the Lounge, but she says the virtual aspect of video games is what originally drew her to Esports.

“I like the fact that you can play with people around the country,” she says. “I can’t see my friends [from Philadelphia] anymore, but I can still play games with them and spend time with them online.”

Even though the Lounge technically opened this past fall, the space is still a work in progress. The club plans to add decor, including banners and TVs to broadcast gameplay live, and their ultimate goal is to make the Nexus Gaming Lounge a hotspot for all local gamers.

“Eventually, we would love to expand the room, increase the number of PCs, maybe bring it into a space that’s more open and accessible to all members of the Evanston community,” Tan says.

Norris’s Assistant Director for Co-Curricular Learning and Recreation Linda Luk shares Tan’s vision of fostering community through accessibility.

“The Nexus was this place to come together, and that’s the intention of the design,” Luk says. “I think students really stood behind that vision and that idea.”

Northwestern students enjoy the Nexus Gaming Lounge in Norris University Center.

The secret life of campus dogs

An inside look into the lives of our campus furry friends.

WRITTEN BY VICTORIA RYAN // DESIGNED BY GRACE CHANG // PHOTOS BY ALESSANDRA ESQUIVEL

It’s a sunny day on the Lakefll at the beginning of spring. The birds are chirping and the breeze blows through my fur. I look around and see people talking, going on walks and … squirrel!

Dogs owned by professors, Northwestern sta are a common sight around campus. But what is life like for these furry friends? investigates the daily lives of the dogs we know and love.

Editor’s Note: Due to the language barrier between dogs and humans, these interviews are based on conversations with their owners.

These interviews have been edited and condensed for clarity.

North Area Resident Director Sarah Loefer moved to Schapiro Hall in September 2021 with her husband and rescue dog Bella. Bella is a mix of breeds, mostly Australian Cattle Dog and black lab. Loefer adopted her right af pandemic began in 2020.

This unique living situation allows Loefer to bring Bella to work.

“I bring her to my weekly o hours and people who miss their dogs from home get to see her,” she says. “That really brings a lot of joy to my heart.”

Let’s see how Bella is enjoying

NBN: What is your favorite spot on

The beach, because I like to drag my parents there even if it’s too cold. Sorry, Mom and Dad!

NBN: What is your favorite food and

I looooove playing fetch with my tennis ball. I’m very good at it. I also love playing with my toys and dragging them all over the apartment. I take them out one by one and lay them across the rug. I have so many favorite foods, but Easy Cheese spray is my top choice. It’s so yummy and delicious! I also love turkey, especially on Thanksgiving.

NBN: Describe your social life on

I’m a bit of an introvert, so I socialize mostly with my parents. I have a small chihuahua mix cousin that I see occasionally. He’s OK. My parents will babysit other dogs sometimes, and I tolerate them, but I like being in a one-dog house. The students, on the other hand, I love. They give me so many treats, and they’re always so happy to see me.

Silvia Toledo is the Program Assistant for the Latina and Latino Studies Program, and her border collie Banksy frequently visits campus. Banksy is a rescue and is currently taking on therapy dog training.

“She’s very smart,” Toledo says. “We are waiting for her to ofer to do our taxes.”

Now, let’s hear from Banksy herself.

NBN: What is your favorite spot on campus?

Banksy: The Lakefll, for sure. Oh, wait,

Banksy & Silvia Toledo

Bella & Sarah Loefer

I also love the area by the Rock with all of the trees. I go bananas for the squirrels.

NBN: What are your favorite foods?

Banksy: Chicken! I also really like treats. My favorites are dog ice cream and peanut butter, for sure.

NBN: Describe your social life on campus.

Banksy: Lots of playdates with my dog and human friends. I have two dog siblings, and I love going running with them. I meet a lot of people and dogs when I run, and it’s the best!

NBN: What is your favorite thing about being on campus?

Banksy: Meeting new people and making them happy!

NBN: What does your ideal day look like?

Rosie: I like to run around before I go inside and sit in my mom’s ofce. I love it when people come to the ofce and pet me and play with me. Then, I like to go to classes. Afer the day is done, I get more time of-leash before I get into the car and go home. Mom will always give me food, no matter what time it is.

NBN: What is your favorite food and favorite toy?

Rosie: My favorite food is Bully Sticks. My favorite toy is my hedgehog named Hedgy. My mom calls me a hedge fund manager because I get a new one every six months, but I won’t get rid of my old ones.

Another familiar face on campus is Rosie, a labrador and hound mix belonging to Gender and Sexuality Studies professor Jillana Enteen. Enteen rescued Rosie seven years ago from a local shelter and says she knew right away that she was a perfect match. Having completed emotional support animal training, Rosie attends classes and comforts students dealing with college stress.

NBN: What is your favorite thing about being on campus?

Rosie: My favorite part is getting to meet students. I love when they come to the ofce, when I’m invited to their classroom, when I see them when I’m walking around on campus or when I can comfort them. The best thing about Northwestern is all of the dog-loving students!

NBN: What is your favorite spot on campus?

Max: There’s a rock on the walk between Lincoln and Deering. I go there all the time and snif it. It’s a very nice rock.

NBN: What does your ideal day look like?

Max: Seeing lots of students and having

Here is what Rosie has to say about her time on campus.

NBN: What is your favorite spot on

Last, but certainly not least, is President Michael Schill’s dog Max. The two enjoy going on walks and seeing students along the way. Max is a mix of breeds, including Pomeranian and Cavalier King Charles Spaniel. Schill adopted him from a shelter during COVID-19.

Let’s see how Max enjoys campus life.

Rosie & Jillana Enteen

Max & Michael Schill

PHOTO COURTESY OF ELISA HUANG

A new

playbook

The new basketball ticketing system is reshaping the student section — for better or for worse.

WRITTEN BY ELEANOR BERGSTEIN // DESIGNED BY JACKSON SPENNER

At Northwestern feld hockey’s national championship game this fall, forward Sophie Dix found herself marveling at the size of the crowd. The Weinberg third-year couldn’t help but notice that the University of North Carolina had to add seating for the game’s 3,200 fans. Supporters crammed into the stadium, which usually only seats 900, and even watched from surrounding streets and hills.

Field hockey is one of Northwestern’s winningest teams — this was their third consecutive championship appearance — yet not a single home game this past season drew over 633 fans.

Last year, students clamored for men’s basketball tickets and flled Welsh-Ryan Arena with never-before-seen crowds. Dix wonders why her team, ranked second in the nation, does not attract the level of support other Northwestern sports have proven is possible.

This fall, Northwestern athletics introduced a new points system to organize men’s basketball ticket claims and incentivize attendance at other sporting events. In the new system, students accumulate points by attending diferent games, which determine their priority in claiming men’s basketball tickets.

The system has helped encourage higher attendance across the board. However, its shortcomings also raise questions about the hierarchy of Northwestern sports and fan engagement. Highly successful teams, like feld hockey, have not reached attendance levels concordant with their accomplishments. Many teams are still struggling to fnd

student fanbases, and there is a large discrepancy between crowd sizes at men’s and women’s basketball games.

The system’s success: rising attendance

Weinberg fourth-year and Wildside Programming Chair Vir Patel remembers attending games his sophomore year and seeing people doing homework in the stands. He says the points system has encouraged students to show up for previously lower-attended events and bring more energy.

“It seems like the culture around what going to games is like has completely shifed,” Patel says.

Attendance statistics provide insight into this culture shif. Field hockey, volleyball and men’s soccer all saw rising attendance this fall. The average home volleyball game, for example, brought almost 700 more fans in 2023 than in 2022. Men’s soccer’s average home attendance went from 467 last year to 567 this season.

SESP second-year Nigel Prince, a defender on the men’s soccer team, says he noticed the increase in support. In 2022, the team won one game at home. This year, they went 8-2-1 in Evanston. Prince says the energy brought by a bigger crowd played a role in this improvement.

“Just the home feld advantage, having the crowd saying your name, rooting for you, chanting, in your corner, for us made a huge diference,” Prince says.

Welsh-Ryan Arena

According to Wildside Social Media Chair and Medill second-year Dylan Friedland, Wildside collaborates with the athletic department to designate some events as being worth double points. Along with giveaways, this encourages more students to attend games.

In September, Welsh-Ryan Arena saw its largest-ever student crowd show out for volleyball’s match-up against University of Wisconsin-Madison. The 1,746 students were incentivized, at least in part, by the game’s double-point status, according to Patel.

“People are physically the sport.” there, [but] that doesn’t mean they’re invested in

Raghav Khosla Medill second-year

To prevent students from scanning their Wildcards to get points and immediately leaving, several safeguards were implemented. For example, at soccer games students had to stay until at least halfime to get points. For volleyball, they had to stay for two sets.

Dix and Prince say the added student support is worth it, even if people only come for the beginning of a game.

“We do what we do for the school,” Prince says. “We hold the ‘N’ and we hold the purple very highly, so it’s always great to have our fellow students come out and support.”

The fipside: critiques of the system

While the points system has helped spark rising attendance, there is room for improvement.

The system assigns a certain number of points to diferent games. For example, women’s basketball games are worth

fve points, and other Olympic sports are worth four. To claim men’s basketball tickets, students are sorted into four windows based on how many points they accumulated from attending various events this fall and winter. The system is designed to reward students who support Northwestern athletics across the board. The reality is not so simple.

Medill second-year Raghav Khosla thinks the athletic department should encourage the student body to appreciate the athletic successes of all teams. He questions if the points system may inadvertently reinforce the hierarchy that prioritizes men’s basketball by making those games the reward obtained from attending other events.

“It’s not just football and basketball. Northwestern athletics is so much more, and that should be the main goal,” Khosla says. “That should be a vision statement, and that’s what they build a system around.”

Khosla says he is frustrated that some students only go to games to get points.

“People are physically there, [but] that doesn’t mean they’re invested in the sport,” Khosla says. “It’s unfair to the studentathletes who know people are coming to their games not to watch them but just to get points to watch the men’s basketball team. Those student-athletes deserve to have fans that are rooting for them.”

Many students, including McCormick third-year Brett Lickerman, went to feld hockey and soccer games for the frst time this fall to improve their chances of getting men’s basketball tickets. This winter, Lickerman attended several women’s basketball games, especially trying to go when a double-points incentive was ofered.

“Unfortunately [these women’s basketball games] were on Sundays, when football is, so I would bring my computer and watch football while I was at the game,” Lickerman says.

Lickerman says if it weren’t for the points system, he wouldn’t have attended these games.

“Women’s basketball was defnitely more exciting than I expected,” he says. “Women’s feld hockey, I got a little into it, too.”

Women’s basketball’s average home attendance is higher

5

3 POiNTS

1

this year, from 1,320 fans a game in the 2022-23 season to over 2,000 in 202324. In comparison, attendance at men’s basketball is averaging at over 5,000 fans per game.

McCormick second-year cheerleader Anna Lee is at every home basketball game. She says the diference between support for the men’s and women’s teams is staggering.

“For women’s basketball, no one feels the social pressure to go,” Lee says.

Attendance counts

“When people go to the men’s games, the atmosphere is so good. It’s exciting, and it feels fun to be at. I think both are equally as fun to watch, but it’s a very different atmosphere when there’s other students there.”

Patel says a combination of factors contributes to lower attendance at women’s basketball. For example, he says when the games are on Sundays there is no shuttle service to Welsh-Ryan Arena.

Students may also be demotivated since the women’s season happens at the same time that men’s basketball claim windows are released, so they no longer have the same incentive to collect points.

Even though many students attend games with the primary goal of earning points, Patel says it is worth it for the teams to receive more support.

Prince says exposure to diferent sports may help students discover new interests, even if they originally came for points.

“I think the more people that come will realize it’s a great experience and any sport can be enjoyable and can be fun to watch,” Prince says.

Some students have also expressed frustration with the fact that the points system puts constraints on their schedules.

There is a 20-point penalty if a student claims a ticket and does not use it on game day. Since claim windows are ofen weeks before the actual games, gamedays ofen see a scramble of students trying to transfer their tickets to others.

Many students in the last claim window have been able to get tickets to all the games they want, raising the

question of whether the points system is even necessary. But Patel says some students purposefully don’t claim right when their window opens because they aren’t able to commit so far in advance.

“People are worried about not being able to make games or not being able to get rid of their ticket,” Patel says. “I also think the infux of people who are willing to give away their tickets makes people feel they will have the opportunity to get a ticket later on.”

Patel adds that the demand for men’s basketball tickets has not decreased from last year; the claim windows have simply helped organize who gets tickets.

“The points system gives people who want to make sure that they’ll be at these games the opportunity to do that,” he says.

“Lacrosse, they’re national championship contenders year in, year out, and sofball made it to the tournament last year,” Patel says. “Leaning on that is defnitely going to be key, maybe re-incentivizing the point system.”

“You’re no longer your team.” just playing for

Sophie Dix Weinberg third-year

Patel expects the ticketing system will be reassessed and improved, hopefully with the consideration of student feedback.

“I think we learned a lot from these two quarters,” Patel says. “This is the frst time we’ve done it, so there are a lot of things we can improve on, of course.”

Patel says despite some “growing pains,” the points system has helped make important improvements to athletics and built better atmospheres in the stands.

Khosla and Patel agree that the biggest beneft of the points system is highlighting the variety of incredible teams and athletes.

Looking to the spring, Patel expects a rebound in attendance, especially at lacrosse and sofball, which he says are easy to market because of their successes.

Dix hopes lower-attended sports, especially women’s sports, can be promoted to students in other ways beyond the points system. She says she would like to see students supporting athletes as fellow classmates. Seeing students in the stands makes her feel like she’s part of something greater.

“You’re no longer just playing for your team,” Dix says. “You’re playing for Northwestern.”

SAFETY

Intimacy coordinators are creating safe spaces for performers at Northwestern and changing the entertainment industry.

WRITTEN

BY ESTHER LIM // DESIGNED BY ALLEN YOU

* Content warning: This article contains mentions of rape and sexual assault.

In their sophomore year of high school, Communication third-year

Julie Monteleone joined their local theater company’s cast. There, they witnessed a moment that would come to shape their presence in Northwestern’s student theater scene: an unscripted, nonconsensual kiss.

“Someone on stage added in a kiss that had never been talked about before, and the other actor experiencing it was really thrown of,” Monteleone says. “Having seen that, being part of that production, with moments that felt unsafe physically for myself when I was working as an actor — that was, unfortunately, the impetus.”

Monteleone says the swirling feelings of discomfort and tension among the cast inspired them to work as an intimacy director on student sets at Northwestern.

As the entertainment industry grows more vocal about consent and sexual exploitation, Northwestern’s student performing arts scene is also engaging in this dialogue by incorporating intimacy coordination and direction into their work.

In flm or theater productions, intimacy directors (for the stage) and intimacy coordinators (for the screen) act as liaisons between the performer and the director to create intimate scenes that require special attention to various emotional, mental and physical sensitivities. This could be a simulated sex scene or a scene depicting domestic assault.

During their frst year at college, Monteleone worked as a fght director on the set of Spring Awakening, a musical put on by the Jewish Theater Ensemble. Here, they got to see intimacy work in practice for the frst time. Kira Nutter (Comm

’21) helped bring challenging, heavy scenes depicting rape and sexual assault to the stage without turning to literal reenactments of this violence.

“A big part of consent practices and boundary practices is this idea that there’s always a diferent way to tell the story,” Nutter says. “What is written on the page doesn’t tell us what we can and can’t do as artists when telling that story. We have ownership of that story and we can tell it in a way that supports our artists in that room.”

Being in a safe environment allows performers to fully apply their creative agency to express the emotions of the scene, Monteleone says. This means intimacy work also includes providing methods for the actors to distance themselves from those ofen intense emotions.

Communication third-year Angelena Browne’s frst-ever flm role included

a scene depicting fashbacks of sexual assault. Working with a professional intimacy coordinator allowed Browne to lean into the emotional vulnerability of her performance without the pressure of confronting the emotional intensity of the scene all on her own.

“Acting is a very vulnerable thing, so I think it’s hard sometimes for both actors to feel open enough to actually talk about what’s going on and fgure it out for themselves,” she says. “That’s where the coordinator comes in.”

To build this safe space, Monteleone frst meets with the production team to discuss the nature of the intimate scene — is it violent? Romantic? Abusive? From there, they sometimes meet with the whole cast and crew to conduct a workshop about consent and safety. Then comes the choreography, where they use tools such as body mapping, where the performer indicates where and how they would or would not like to be touched that day.

Beyond choreographing and leading workshops, Monteleone advocates for people of color, queer individuals and women, who have historically experienced unbalanced power dynamics in the industry.

Last year, Monteleone worked as the intimacy director on the set of Pillowtalk, a play featuring vignettes of stories taking place in a bedroom. The cast and crew of the play had a complex question on their hands: With an allwoman cast and a storyline involving domestic and sexual violence, could they be perpetuating harmful narratives about queer relationships?

Monteleone engaged in active discussions with the cast and crew about how their work might reverse these narratives and make the act of telling these characters’ stories gratifying for the performers. This meant they had to closely consider the gender dynamics at hand.

“Abuse exists everywhere and domestic violence can happen between anyone, but also, we have to hold space for the statistical reality of how many cis[gender] straight men are the ones perpetuating assault,” Monteleone says. Ultimately, the production decided to have one of the actors portray the abusive character as a man.

Producing a

SAFE SPACE

Discussscenes withproduction

“It was a lot of checking in — are we still feeling safe with this? Is this feeling sustainable, as opposed to just perpetuating trauma over and over again?” Monteleone says.

These questions are especially important to reckon with given recent movements for equity in the industry, such as the #MeToo movement and the Screen Actors Guild-American Federation of Television and Radio Artists union strikes.

Sarah Scanlon, a Chicago-based actress and intimacy coordinator/director, was one of the frst to be certifed in the city. She has also been a member of an organization called Not In Our House, which drafed a document outlining the protocols and procedures for maintaining safety in the theater world known as the Chicago Theatre Standards. It was created in light of cases of sexual exploitation in the Chicago theater scene.

Workshop with cast&crew

Scanlon notes that awareness of intimacy directing grew alongside the #MeToo movement. Now, when she enters a project, she feels she can hit the ground running. In conjunction with the recent writers’ strike, Scanlon recognizes a movement of creatives in the entertainment industry refusing to let their work, well-being and craf be devalued.

“I think the intimacy direction movement has really helped with that: in creating spaces that are advocacyfocused and making sure that the art we’re creating is being done in a safe and respectful way,” Scanlon says.

Bodymapping & choreography

The feld is still fnding its place in the entertainment industry, which Nutter fnds exciting and full of potential, especially in the education and certifcation of new intimacy professionals. Organizations like Intimacy Directors and Coordinators push for a certifcation-centered approach, while organizations like Theatrical Intimacy Education push for a model where individuals build their expertise over time through several classes. Nutter is interested in the bridge between these two approaches where actors know they are working with a certifed professional who is also continuously learning.

“There’s a lot of diferent things blending together into what the intimacy industry looks like right now in a way that I don’t think anyone has a set answer for, and that’s exciting,” Nutter says.

As an undergraduate student at Northwestern, Nutter had the opportunity to gain experience by shadowing professionals who had been hired to do intimacy work for productions at the Wirtz Center for the Performing Arts. Over time, Nutter was able to build their practice working with student projects on campus. Looking back, they recognize the campus’s rich and diverse theater and flm scene as an unique opportunity for encouraging the growth of the feld of intimacy work.

“Are we still feeling safe with this? Is this feeling

sustainable, perpetuating trauma

as opposed to just over and over again?”

Julie Monteleone Communication third-year

“A unique facet of Northwestern is that we have such a strong student theater and flm community,” Nutter says. “It’s having so many opportunities to work in so many diferent rooms, on so many diferent stories and with artists who have very diferent ways of approaching storytelling as well.”

And yet at one point, Nutter found themself spread thin, working on 13 projects in one quarter. Nutter hopes for better resources for student intimacy workers. These resources might look like department-sponsored guidance or more mentorship opportunities for students to connect with professional intimacy coordinators and directors.

“That’s the solution a lot of us are fghting for, to normalize [intimacy work] as a standard, especially in a hub like Northwestern and other creative arts communities, where we’re telling so many stories constantly,” Nutter says. “Being able to have that resource is going to create that full level of support that we’re striving for across the industry as a whole.”

As student performers look to their future careers, some such as Browne acknowledge that intimacy work is just the beginning of changes that need to be made in the industry. Still, her experience with intimacy coordinators and directors during her time at Northwestern has been a valuable tool to advocate for herself as an artist.

“Northwestern is a very progressive space for an actor. They are focusing on the good of theater and creating a safe space for performers,” Browne says. “The outside world hasn’t necessarily caught up to that or even put down the groundwork to try and fgure that out. I think having this experience will help [me] advocate for myself more out there. I know what acting in a safe space feels like.”

KITCHEN

One student group is repurposing leftovers to fght food waste and tackle food insecurity.

WRITTEN BY NOAH COYLE // DESIGNED BY ALLISON KIM

In the kitchen of 1835 Hinman’s bygone dining hall, SESP fourth-year Emily Lester dons a pair of latex gloves and a hair net. She portions a scoop of rice into a plastic container before passing it to the student next to her. For the next hour, Lester and the other volunteers will pack lunches for those in need.

Lester is one of the co-presidents of Campus Kitchen, a student organization that repackages lefover food from campus dining halls and events and distributes it to Evanstonians in need. The pandemic halted operations for the club, but Lester and her co-president, Weinberg fourth-year Sean Pascoe, rebuilt the organization in 2021. Now, Campus Kitchen recovers thousands of pounds of food a year and hopes to expand their impact in the future.

Campus Kitchen’s goals are twofold. First, they aim to reduce food waste by recovering lefover food from campus. They also help fght food insecurity by repacking that food into individual meals for members of the Evanston community.

Campus Kitchen recovered nearly 700 pounds of food and donated more than 1,100 meals this past fall. One of Campus Kitchen’s community partners is the residency at the McGaw YMCA on Grove Street. Campus Kitchen provides around 40 to 60 meals each Wednesday

to help serve approximately 150 lowincome residents living in the YMCA’s men’s residence.

“Evanston is super de facto segregated, which is not super evident necessarily, especially if you’re a Northwestern student existing in the Northwestern space,” Pascoe says.

Pascoe says poverty is an overlooked issue in Evanston. While he acknowledges the importance of engaging with underserved communities in Chicago, Pascoe emphasizes a need to refect on local issues as well.

“Having these local networks is really important — for one, being more sustainable about how we use food, but also getting involved with the issues of equity around us,” he says.

Recover, prep, deliver

Campus Kitchen applies a handson approach to volunteer work, which is what initially attracted Lester and Pascoe.

“The nice thing about this is it’s a break from your normal life. It’s very tactile. You’re actually touching the food, and you know you’re making a diference,” Lester says.

To collect the thousands of pounds of food they recover over the school year, Lester and Pascoe must remain

dedicated to contacting the University’s chefs for donations and coordinating with volunteers to ensure the food is safely stored, packed and delivered.

“Me and Sean always like to joke that it’s like our full-time job,” Lester says.

The process of gathering and distributing food from dining halls and campus events is divided into four shifs: recovery, resourcing, meal prep

and delivery. It begins on Tuesday and Friday mornings, when Campus Kitchen contacts food providers around campus to see if they have untouched lefovers available. If so, volunteers for the recovery shif gather food from providers and bring it to Hinman.

The resourcing team then ensures that the recovered food is at a safe temperature before freezing it. Next, during meal prep shifs, which take place on Tuesdays, Fridays and Sundays, volunteers thaw inventoried food and arrange it into individual, well-balanced meals. Finally, volunteers drive to deliver the meals to community partners, such as the YMCA and the Rotary Club of Evanston, or directly to individuals.

A course of change

Even with a sufcient number of volunteers, Campus Kitchen’s community impact hinges on the quantity of food they can collect from campus partners. This year, the lefovers aren’t amounting to much.

“We’ll have all these volunteers who are ready to make meals and then we have one pan of tofu and one pan of rice,” says Lauren Kelley, Weinberg third-year and Campus Kitchen internal vice president. “There’s not much we can do with this.”

The lack of available lefovers makes delivering the promised number of meals to community partners each week a challenge, but Lester does see the positive side: Campus dining is not producing as much waste as in previous years.

Campus Kitchen can only accept entirely untouched food. As soon as a tray is put out for students, that food cannot be recovered. According to the Dine On Campus website, all food scraps, lefovers from the service line or food that was taken but uneaten by students is composted.

Because Campus Kitchen is entirely student-run, the organization relies on the resources available to students to conduct its operations. This presents an additional challenge: limited access to cars. Northwestern took away the club’s access to campus vehicles; now, delivery shif volunteers use their personal vehicles or Zipcars to distribute food to community partners and individuals.

Many of the issues Campus Kitchen has faced in recent years are consistent with the organization’s history of continuous transition.

The creation of organizations like Campus Kitchen was facilitated by the Bill Emerson Good Samaritan Act of 1996. By minimizing liabilities related to making food donations, the act empowered altruists nationwide to combat both food waste and food insecurity by giving food that would have otherwise been disposed of to those in need.

Five years later, associates of the food-recycling D.C. Central Kitchen founded the Campus Kitchen Project, and Northwestern’s chapter was established in 2002 as one of the frst. This arrangement lasted 16 years. In 2019, the Campus Kitchens Project suspended its national operation to focus on the Washington area.

Newly solo, Northwestern’s Campus Kitchen entered a transitory period in which it became a student-run organization and moved its headquarters from one campus locale to another. Before the national nonproft folded, Northwestern’s Campus Kitchen was equipped with a full-time staf member. Now, Lester says she and Pascoe have assumed the responsibilities of this fulltime employee.

“Despite being an established org on campus, when Sean and I came in as freshmen and started running the org, we were essentially rebuilding the org from not scratch, but essentially from scratch,” Lester says.

To help remedy the pressures that the disbanding of the national nonproft brought, Northwestern’s Campus Kitchen partnered with the Food Recovery Network (FRN), a nonproft that has similar goals to Campus Kitchen. Since Northwestern’s Campus Kitchen was already established before becoming a chapter of the FRN, it has more freedom to continue operations as usual. Lester and Pascoe say this partnership adds legitimacy to their organization and ofers support when necessary.

Kelley will take over for Lester and Pascoe as the next president of Campus Kitchen. According to her, specifc expansion plans include procuring a vehicle and sourcing food from local restaurants, nursing homes and Evanston Township High School. They are also hoping to further streamline operations through their partnership with Northwestern Develop + Innovate for Social Change (DISC) to create an app to better organize shif scheduling and food-collection data.

Though there have been several changes to the organization since they frst assumed their presidential posts, Lester and Pascoe believe Campus Kitchen’s future is bright.

“Sean and I have been here for so long,” Lester says. “I feel like we’ve had a very unique opportunity to set up a future, leave a legacy in a way, setting up a very sustainable thing.”

A major

S MAJOR CAREER

witch

How some students apply their degrees in unexpected ways.

WRITTEN BY SARAH SEROTA // DESIGNED BY LAURA HORNE

Northwestern ofers over 85 undergraduate majors. But for some students, the range of disciplines fails to capture their future ambitions. Rather than remaining within the confnes of their concentration, some Northwestern students and alumni pursue entirely diferent professions, defying the norms for their area of study.

John McDermott

A priestly pilot

John McDermott’s (Weinberg ’23) studies at Northwestern seemed grounded. As a Religious Studies major, he focused his learning on religious texts and movements.

Yet McDermott’s career goes far above literary analysis. Rather than sifing through religious documents, McDermott can be found fying thousands of feet in the air as a pilot. Currently, McDermott is a certifed fight instructor and is interviewing for fight teaching jobs to gain experience until he meets the minimum requirements to fy for commercial airlines. Ever since he discovered his passion for aviation in early high school, McDermott never considered an alternative to piloting. His love for fying did not start in the air; it began with a book.

A Higher Call by Adam Makos explores the story of a German fghter pilot during World War II who lost the opportunity to win the German equivalent of a Medal of

Honor because he escorted an American bomber back to the U.K. The book sent McDermott down a “rabbit hole of aviation” that he has yet to escape. He became infatuated with everything about pilots: how they trained, the culture among them and the diferences between pilots from varying countries.

The Northwestern major catalog contains no feld of study focused on aviation, so McDermott’s choice of major instead stemmed from his love of learning about history and culture. McDermott, who went to a Catholic high school but is not Catholic himself, dedicated his studies to exploring the multitude of religions the world has to ofer.

Taking the traditional college path is not a requirement to become a commercial pilot, but uncertainties about job stability in aviation, as well as family encouragement, motivated McDermott to go to college anyway. McDermott says temporary leaves can be fairly common among pilots, so having a background in another feld is reassuring.

Unlike some aspiring pilots, McDermott had no relationships with anyone in the feld, as neither his friends nor family members few.

“Connections are ofen highly important, at least in aviation,” McDermott says. “[They] can ofen be critical to making bigger steps in careers sooner.”

The key to making his dream a reality

To: A new career path

was perseverance. Northwestern does not ofer fight training, so McDermott trained on his own time. He also founded Northwestern’s Aviation Club, which brings together students interested in aviation and creates a space to learn professional skills required within the feld.

Refecting back on his undergraduate career, McDermott says it was important to study a subject he was passionate about so he could leave time and energy to pursue other goals.

“It is a matter of choosing what you study wisely,” McDermott says. “Figure out the best way to make both happen and go get it.”

Bradley Altman

Stocks and stoichiometry

Tucked away in a high school chemistry classroom, experiments exploded colorfully before Bradley Altman’s eyes. The vibrancy of his chemistry class hooked Altman, now a Weinberg fourth-year, on the study of molecules and matter. During the summer afer his junior year of high school, he opted to enroll in an organic chemistry class at his local community college. He majored in Chemistry for the year he attended Brandeis University, and

chose it once again afer transferring to Northwestern for his sophomore year.

But as Altman’s graduation approaches, he is not searching for a job in a laboratory or planning to pursue higher education in science. Instead, Altman plans to take a starkly diferent path — one of Patagonia vests and Excel spreadsheets — in fnance.

Altman loves chemistry’s interdisciplinary qualities; it ofers a mix of theory and hands-on aspects, allowing Altman to create something of his own using mathematical and analytical skills.

“To me, chemistry is a culmination of being able to attack something on the cutting edge that is very theoretical and translating it into groundbreaking physical applications that can be used in a smattering of felds,” Altman says.

Initially, Altman anticipated staying in the feld. He strongly considered pursuing an M.D.-Ph.D. post-graduation, which would involve going to medical school while also seeking a Ph.D. in chemistry.

During his junior year, however, Altman reached the apex of the Northwestern chemistry sequences: the physical chemistry classes. The course load demanded extensive time and labor, meeting fve times a week. On top of the daily lectures, Altman had to enroll in an advanced lab sequence, which took up 13 hours weekly. With chemistry work piling on, Altman began to consider what his work-life balance might be like as a post-grad, where he would live and

“It is a matter of choosing what you study wisely. Figure out the best way to make both happen and

John McDermott Weinberg ’23

whether he wanted to pursue additional years of education.

A growing passion for fnance blossomed during Altman’s pause from chemistry. Afer transferring to Northwestern, Altman joined Delta Sigma Pi (DSP), a business fraternity on campus. DSP gave him the opportunity to explore a future in business — whether that be fnance, consulting or entrepreneurship.

Altman soon realized he could apply his theoretical and problem-solving skills from chemistry to a job in fnance. And while Altman’s future in private equity does not involve thermodynamics or quantum mechanics, he doesn’t regret the time he spent studying chemistry.

“[College] ofers opportunity,” Altman says. “There should be no fear associated with [it]. Just because I’ve spent so much time and this is what I’m primarily focusing on right now … [it] doesn’t mean that you can’t branch out and explore diferent areas.”

Instead of a standard neuroscience path, Lee opted to travel. She spent most of her junior year abroad in Paris, which she says greatly altered her career path. While there, she enrolled in Northwestern’s Institute for Field Education (IFE) program, where she spent most of her time abroad interning for a company instead of taking classes. While studying abroad, Lee interned at a medical equipment manufacturing company as part of her IFE requirements. Her experience abroad cemented a passion for working on a global scale, and when the company asked if she wanted to continue interning there as their medical marketing intern, Lee jumped at the opportunity. When she returned to Northwestern for Spring Quarter, Lee knew that she wanted her career to go global.

Lee’s career journey would take her far

outside of the realm of a doctor’s ofce or lab. Currently, she works as a change management consultant for a global digital consultancy. While she is typically based in Chicago, she is currently on a temporary secondment in Auckland, New Zealand. She still fnds herself applying the scientifc method to solve other companies’ issues.

“We have to be able to present the content we create for our clients in the way that suits their communication, behavior, training [and] learning mindsets as a company,” Lee says. “A lot of the types of classes that I did around cognitions or learning-based psychology were really helpful in what I do today.”

Lee found value in staying true to her passions, regardless of what other peers or advisors may say or think.

“My biggest advice to all the students out there would be just to try and tune out some of the noise from the pressure,” Lee says. “Just be yourself and be confdent in [your] decisions and try not to be too bogged down by the anxiety of existing in society today.”

Scrolling through Northwestern’s website as a frst-year, Annie Lee (Weinberg ’19) scoured the diferent majors Northwestern had to ofer. Lee felt subject-agnostic, though generally aware of what she was interested in. When she entered college in the fall, she had planned to double major in Psychology and Economics. But neither fulflled her educational passions.

Lee found her love for learning in an interdisciplinary mix of French and Business Institutions, alongside Cognitive and Behavioral Neuroscience. But as she got further into her studies, Lee realized her future aspirations difered greatly from those of her peers. She never pictured a future in a lab or as a doctor.

“I distinctly remember a conversation with my neuroscience department advisor,” Lee says. “She asked me what are the odds I go to medical school and choose that path for myself. And I said, ‘1%.’ It would need to be a life-changing experience to sway me.”

And swayed she was not.

1. Go to Northwestern

A match made in

Fewer and fewer Northwestern couples are saying “I do.”

WRITTEN

BY SARAH LONSER // DESIGNED BY LAURA HORNE

The best majors, extracurriculars and student-to-teacher ratios are all things a counselor might bring up when you’re considering colleges. One thing they don’t mention? The dating scene.

The prospect of fnding a “college sweetheart” has grown increasingly unlikely over the years. The Northwestern Alumni Association (NAA) says the marriage rate among Northwestern University graduates peaked in 1979 at 2.5%. Though the NAA is not able to give an exact current percentage, they can confrm it has declined. There are certainly stories of more recent successful Northwestern meet-cutes, but according to current students and national marriage rates, marriage appears to be less of a priority for college students.

Love by the

lakefront Heavenst n?

Don’t fret if you’re a Wildcat looking for “the one.” Sidney Stewart (SESP ’10) did not spend his time at Northwestern actively looking for a relationship. To him, college seemed more like a place to meet people casually and see what happens.

Though Stewart says he didn’t feel any pressure to begin a relationship in

college, he did think to himself, “If I do date somebody, then this could be the one.” When he met his now-wife Celeste Stewart (Comm ’12), his gut instinct was correct. Both grew up in Michigan but did not meet until a mutual friend introduced them, though Celeste Stewart knew of him

because she was friends with his sister.

The two fnally connected at a party hosted at Sidney Stewart’s fraternity house. Afer meeting, they eventually began dating and married in 2014.

Laura and Abraham Schulte (both

Weinberg ’15) have been together since 2018. The pair frst met at a Willard resident meet-up during the freshman orientation Six Flags trip. They stayed close friends while both being in and out of relationships with other people. They didn’t begin their romantic relationship until 2018 when Laura Schulte was working at Northwestern over the summer and Abraham Schulte came from California to visit her. On Clark Street Beach, Laura Schulte asked him if he would consider a relationship. The rest is history.

“Back when we were there, 2011 to 2015, I think overall the dating culture was sort of a hookup culture,” Abraham Schulte says.

The Schultes agree that college seems to be the place where the possibility of meeting someone similar to you is highest, especially compared to life afer college. Laura Schulte explains that it’s almost like people have been “pre-screened.”

Abraham Schulte says being around so many people within your age range and with similar experiences makes it easier to fnd things in common with people and form

relationships. He says while he was at Northwestern, he thought college was probably where he was going to meet his life partner, if he was going to have one.

However, not all current Northwestern students think the same way. Weinberg second-year Stephen Levitt had diferent ideas about dating and relationships when he entered Northwestern.

“I got the idea of college as everyone is wild and young,” Levitt says. “I defnitely felt the pressure to be a part of hookup culture.”

That was before he met SESP secondyear Anya Mateu-Asbury at a party in Chicago. On a whim, he decided to ask her to a formal his fraternity was hosting. Neither was actively looking for a relationship when they met, but that changed once they got to know each other.

Afer spending more time together, the two decided to pursue their relationship more seriously. Both Levitt and MateuAsbury agree that the possibility of meeting a life partner in college does exist, but that doesn’t mean it is the only or most common option.

First comes love, then comes — marriage?

Northwestern’s Relationships and Motivation Lab (RAMLAB), led by professor Eli Finkel, dives deep into the science of relationships. Ph.D. candidates Emma McGorray and Erin Hughes are researchers in the RAMLAB; McGorray’s research focuses on LGBTQ+ relationships, while Hughes studies identity within relationships and the efects of incarceration on relationships.

“The average age that people are getting married has continuously gotten older and older … which is probably showing that it’s become less common over time to meet someone in college and get married to them, and I don’t think that’s necessarily a bad thing,” Hughes says.

Alexandra Solomon, clinical psychologist and “Marriage 101” professor, thinks the rising marriage entry age refects a change in how college students think of relationships, as marriage is becoming the last step in adulthood rather than the frst.

“We as a culture have decoupled relationships and sex and are making space for other types of commitment,” Solomon says.

“Hooking up” was a term coined by Generation X, as they were the frst generation to openly experiment with the idea of casual sexual encounters, Solomon says. However, the concept of a “situationship” may be more recent.

“The idea of a stable but uncommitted relationship is a bit of a newer development — a reflection of our growing collective imagination of what relationships can look like,” Solomon says.

Even though, according to Sidney Stewart, people were dating casually when they were in college, Celeste Stewart thinks these relationships are not the same as the situationships we see today.

“People either were dating or they weren’t dating,” Celeste Stewart says. “I know nowadays a lot of people are ‘not really seeing each other.’”

“The idea of a stable but uncommitted relationship is a bit of a newer development — a refection of our growing collective imagination of what relationships can look like.”

Alexandra Solomon

Clinical psychologist/ Northwestern professor

Dating in the digital age Embracing the single era

For students interested in dating, fnding opportunities has its own set of difculties. Communication second-year Autumn Grieb says one issue that plagues current students is how fast information spreads around campus, whether on social media or by word-of-mouth. Though Northwestern is a medium-sized school, the student body can feel small when it seems like everyone knows everyone — and their personal business.

“We’re a little too interconnected. It shouldn’t be that when I start talking to someone new, everyone knows it,” Grieb says.

Grieb says dating is made difcult since noncommittal, indecisive situationships are common among college-age students. But there may be a more Northwesternspecifc reason why Wildcats are drawn to situationships.

“It’s a campus full of ambitious, hardworking, ofentimes burned-out young people, and romantic relationships require emotional bandwidth,” Solomon says. “They require you to center somebody other than yourself and that’s a really hard ask for students who are pretty stretched.”

At an academically rigorous institution like Northwestern, relationships may sometimes take a backseat to the various classwork, never-ending midterms, internship applications and extracurriculars. But that doesn’t mean people lose their innate, biological need for closeness, bonding and — let’s be honest — sex. A situationship can allow people to fulfll these needs, but with fewer expectations about emotional commitment and capacity, Solomon says.

Another change in the collective view of relationships is a shif in the way we view singlehood. According to McGorray, there has been an increase in research literature about singlehood and the reasons why people may be single. McGorray says one reason may be related to issues with attachment. Someone who fears they are unworthy of love may have an anxious attachment style, while someone who lacks trust in their relationship may be avoidantly attached. But there may be an even simpler reason. Being single may just be “a fulflling personal choice,” McGorray says.

If you are feeling satisfed with your other close relationships with friends, family, coworkers or whoever else may be in your life, you may not feel compelled to pursue a relationship. Everyone fundamentally needs close bonds, but they may not come in the form of a romantic relationship, depending on the person. And if you’re worried you’re not fnding “the one” — or anyone for that matter — in college, don’t despair.

“There’s so much waiting for you afer college,” Hughes says.

On the

Rhode

WRITTEN BY CAROLINE NEAL

DESIGNED BY SAMMI LI

PHOTOS

BY

ELISA HUANG

Meet Nia Robles, Northwestern’s newest Rhodes Scholar.

Weinberg fourth-year Nia Robles spent much of her childhood painting, writing and excelling in humanities classes. But when she learned why ice foats in water during her frst high school physics class, Robles was fascinated. She found herself drawn to gaining a deeper understanding of how the world works. That day, Robles found a passion for physics that has endured through her undergraduate career. In November, Robles was named a 2024 Global Rhodes Scholar, making her the frst Argentinian to receive the scholarship and the 20th scholar from Northwestern since the Rhodes Scholarship was introduced in 1902.

“I didn’t know that [the] Rhodes Scholarship was a thing until last summer, which is crazy because I know many people know [about] this their entire undergraduate career,” Robles says.

Given to 100 scholars annually, the Rhodes Scholarship is the oldest international postgraduate award, allowing selected candidates from around the world to conduct their graduate studies at the University of Oxford. The scholarship is awarded by constituencies, or “a country, a group of countries, and/or territories, regions or states, grouped together for the purposes of administering scholarships,” according to Oxford’s website. Out of 100 scholars, 32 are from the United States, 11 are from Canada and 10 are from countries in Southern Africa. The remaining scholars hail from smaller constituencies around the globe.

Only two Global Rhodes Scholarships are awarded to candidates living outside these constituencies — and Robles, being from Argentina, is one of them.

Her experience at Northwestern — from taking quantum mechanics and particle physics classes to working as an undergraduate research assistant — allowed her to discover her main area of interest: researching the unknowns of the world through theoretical physics.

“I was fascinated by how you can use math to understand the world and explain the phenomena that happen around the world,” she says.

Robles got her start in an experimental physics lab at Northwestern but knew that path wasn’t for her. Robles struggled with the subject, so one of her professors suggested she talk to a Ph.D. student in her current research group who encouraged her to take graduate level classes and work for a theory group. Though theoretical physics groups are harder to fnd at universities than experimental groups, Robles says this is more of what she imagines herself doing as a physicist.

Now, Robles is part of professor John Joseph Carrasco’s Amplitudes and Insights Group, which works in scattering amplitudes, essentially investigating how tiny particles interact with each other. Robles says Carrasco’s group is interested in using supersymmetric theories to understand the general behavior of quantum feld theory and ultimately the nature of the universe.

Carrasco, who wrote one of the letters of recommendation for Robles’s Rhodes application, says Robles frst approached him about joining his research last academic year. Afer seeing her dedication, Carrasco allowed Robles to become the frst undergraduate student in his research group.

“There’s a combination of technical facility and genuine interest that drives her to keep learning,” Carrasco says.

Robles’s journey to becoming a Global Rhodes Scholar started last April when she first visited Elizabeth Lewis Pardoe, the director of Northwestern’s Ofce of Fellowships.

Following a rigorous application process, Robles went through two rounds of interviews. For the last interview, the Global Rhodes Scholar fnalists few to Oxford, stayed in the Rhodes House and took part in dinners with the other candidates, judges and committee members.

“It was kind of fascinating,” Robles says. “Part of me was like, ‘Even if I don’t get this scholarship, I still got a full expense paid trip to Oxford.’”

Each candidate’s fnal interview was 20 minutes. The scholarship winners were announced at dinner that evening.

“It was so shocking,” Robles says. “That weekend felt so surreal for me. I was like, ‘What’s going on?’”

Lewis Pardoe says it’s important for candidates to be “genuinely engaged, interested and committed” to their future graduate study at Oxford — a trait Lewis Pardoe says she saw in Robles.

“Nia [Robles] was clear from the outset that she had identifed precisely why she was interested in Oxford, precisely

the facets of the academic structure and the academic subjects that she wished to pursue there,” Lewis Pardoe says.

Robles’s other interests — social justice and expanding the presence of women in STEM — were “lovely supplements to that core, academic application,” Lewis Pardoe says.

Indeed, Robles wants to use her work as a physicist to make the feld more inclusive, especially for women of color.

Robles says when she started at Northwestern, she didn’t see anyone who looked like her or had the same experiences. Now, she’s organizing a group for Latinx students in physics afer noticing that many “don’t have families in academia” and are international students.