Call for Articles

North Carolina Pharmacist (NCP) is currently accepting articles for publication consideration. We accept a diverse scope of articles, including but not limited to: original research, quality improvement, medication safety, case reports/case series, reviews, clinical pearls, unique business models, technology, and opinions.

NCP is a peer-reviewed publication intended to inform, educate, and motivate pharmacists, from students to seasoned practitioners, and pharmacy technicians in all areas of pharmacy.

Articles written by students, residents, and new practitioners are welcome. Mentors and preceptors – please consider advising your mentees and students to submit their appropriate written work to NCP for publication.

Don’t miss this opportunity to share your knowledge and experience with the North Carolina pharmacy community by publishing an article in NCP.

Click on Guidelines for Authors for information on formatting and article types accepted for review.

For questions, please contact Tina Thornhill, PharmD, FASCP, BCGP, Editor, at tina.h.thornhill@ gmail.com

Official Journal of the North Carolina Association of Pharmacists

1101 Slater Road, Suite 110 Durham, NC 27703

Phone: (984) 439-1646

Fax: (984) 439-1649

www.ncpharmacists.org

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

Tina Thornhill

LAYOUT/DESIGN

Rhonda Horner-Davis

EDITORIAL BOARD MEMBERS

Anna Armstrong

Jamie Brown

Lisa Dinkins

Jean Douglas

Brock Harris

Amy Holmes

John Kessler

Angela Livingood

Bill Taylor

BOARD OF DIRECTORS

EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR

Penny Shelton

PRESIDENT

Ouita Gatton

PRESIDENT-ELECT

Bob Granko

PAST PRESIDENT

Matthew Kelm

TREASURER

Ryan Mills

SECRETARY

Beth Caveness

Shane Garrettson, Chair, SPF

Carrie Baker, Chair, NPF

Katie Trotta, Chair, Community

Jeff Reichard, Chair, Health-System

Dave Phillips, Chair, Chronic Care

Andy Warren, Chair, Ambulatory

Riley Bowers, At-Large

Elizabeth Locklear, At-Large

Macary Weck Marciniak, At-Large

North Carolina Pharmacist (ISSN 0528-1725) is the official journal of the North Carolina Association of Pharmacists. An electronic version is published quarterly. The journal is provided to NCAP members through allocation of annual dues. Opinions expressed in North Carolina Pharmacist are not necessarily official positions or policies of the Association. Publication of an advertisement does not represent an endorsement. Nothing in this publication may be reproduced in any manner, either whole or in part, without specific written permission of the publisher.

A Few Things Inside

CORRECTIONS AND

For

Hello!

My name is Ouita Gatton, and I am excited to be serving as your president this year for the 2023 North Carolina Association of Pharmacists (NCAP). These are exciting times for our Association, and I am so thankful to be on the front lines watching and helping great things occur.

I have had many roles during the 30-plus years I have been a pharmacist. I have been a coach, a teacher, a manager, and a leader. I have learned to say NO, to speak up during a misunderstanding, and made it a practice to learn something new every day from people that cross my path. Most of what I have learned had seeds sown early. I grew up in my family-run pharmacy and watched and learned from my dad what a pharmacist should look like. He was always my inspiration. I have worked to develop many of his characteristics to honor him and his memory. He is why I am so passionate about serving and participating in my state pharmacy association. He taught me early to learn how to be a diplomat and that “people are drawn to you if you drip honey rather than sour

2023 Is Set To Be Another Landmark Year For NCAP

candy.” These skills have served me well as I have learned to navigate life, especially in areas of pharmacy advocacy and advancement. I joined my state pharmacy association early in my career path and never looked back.

I have had the privilege to serve in many different roles with NCAP, including Chair of the Community Care Practice Academy, Member at large on the Board of Directors (BOD), and now President of the Association. I have met wonderful people who remain friends and colleagues to this day. I get to plan socials (just ask someone who came to the convention last year) and look for ways to connect with people to tell them what great things our pharmacy association has done and is doing. I look forward to meeting you this year at NCAP’s various events and hearing your life journey in pharmacy.

If you have been a member of NCAP for any length of time, you know that 2021 was a robust year for the Association. This year provided a long session of the North Carolina legislature, and bill passing is primary. After the COVID tsunami disruption, North Carolina was well-positioned to advance pharmacy practice in several different public health initiatives. For the first time, state standing orders were signed to give pharmacists the right to prescribe and

dispense hormonal contraception to appropriate patients. They even brought together experts in the state to ensure appropriate pharmacists’ training and credentialing took place. Many of you have taken that training or plan to do so soon.

The past two years also marked the passage of standing orders for HIV PrEP, glucagon, smoking cessation, and prenatal vitamins. These are just a few recent accomplishments NCAP has completed in the best interest of patient care and pharmacist advancement. While this excellent work was taking place, continuing education was offered, conventions were held, and residency conferences took place…all back in person for relationship and network building.

2023 is gearing up to be even better. Lobbyists are preparing to introduce new legislation in this legislative long session that will address maintaining PREP amendments for pharmacists giving immunizations, test and treat, and expanded collaborative practice for pharmacists with the intent to also ask for payment and sustainability of services. If the Association is victorious in its work to pass all these efforts, pharmacists will have the ability to not only be properly trained for expanded expertise but to get paid for it as well.

The NCAP Annual Convention is preparing to give attendees time at the beach. For the first time, NCAP is hosting this event at the Beaufort Hotel from June 4-6. Please get your reservations in, as space is expected to fill early. Have no fear, though. There is always a Plan B for those who may not know they can come until the last minute. NCAP really wants to see you there.

Here are a few words for students that are engaged in the Association. Many of you have served in leadership capacities preparing you well for future roles in leadership. I am so grateful that our North Carolina schools put emphasis on leadership and pharmacy advocacy. Your institutions want the best health for the citizens of North Carolina. Your state

pharmacy association wants that, too. If you remain in NC upon graduation, I encourage you to get involved or stay involved in NCAP. Every year there are more and more opportunities to serve on committees, task forces, and the BOD.

In closing, may I ask each reader to consider how you might serve as future partners and leaders in NCAP. The first step includes joining this association. NCAP is YOUR pharmacy association for North Carolina. You are needed. Every voice is needed. Pharmacy must unite and shout with loud voices. We are pharmacists, we matter, and our patients need us.

More to come next time!

Online PTCB prep courses for pharmacy technicians. We help you pass your exam and attain certification. Click the logo and use the discount code NCAP for 10% off the all course bundle.

Edupharmtech.com

If the pharmacy profession had a psyche, then one might say our profession suffers from a myriad of stressors, most of which are outside of our control; however, the profession is also a victim of self-harm. I recently had the opportunity to speak, as a panelist, at the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy Interim Conference in Orlando, Florida. The panel included executive directors from state pharmacy associations and boards of pharmacy. We were asked to speak to how schools of pharmacy could work collectively with our organizations to advance the profession. In our opening comments, we were asked to speak to a new challenge that we were facing and how it was being addressed. In my opening statement, I could have selected from a multitude of challenges but ended up settling on what I have dubbed the “Profession’s Self-Harm Cycle.” Our profession faces enough threats and challenges, and yet, our own profession’s actions and inactions serve to worsen the problems. If we had a patient that was self-harming, we would do everything possible to help that individual. We need to do the same for pharmacy, and it

Penny Shelton, PharmD, FASCP, FNCAP

Breaking The Profession’s Self-Harm Cycle

is up to us to break the self-harm cycle.

Where to start? First, many, if not most, pharmacists, student pharmacists, and technicians have minimal understanding of the interconnectedness between the state’s Pharmacy Practice Act, and what you are allowed to do in practice, and the role of your state pharmacy association. Scope of practice is determined by the Pharmacy Practice Act, and changing it requires legislation. The state pharmacy association is generally tasked with running legislation that helps to protect and advance the profession. Most pharmacists are unaware and choose not to join their state pharmacy association, which weakens the Association. When a profession silos itself and only cares about what directly impacts them or its sector of practice, this further weakens the profession. When the Association is weakened by non-joiners, apathy, or what’s in it for me mindsets, then the Association will not have the resources needed to protect and advance the profession. When threats like poor reimbursement lead to salary cuts, decreased hours, inadequate staffing, and a poor work environment due to individuals having to do more with

less, then people in our profession become unhappy, unfulfilled, and disillusioned with the profession. Some discourage young bright minds from choosing pharmacy as a career. Enrollment in schools of pharmacy drops, faculty attrition occurs, and the existing faculty are asked to teach and do more with less. When stretched to the max, teaching and reinforcing things like the value of the state pharmacy association easily drop off the radar, and we then have uninformed graduates entering the workforce as non-joiners of their state pharmacy association. We go round and round, hurting our own profession. Everyone in our profession has a duty to help ensure their state’s pharmacy association is a strong association. We also have a duty to protect this profession by flipping the self-harm cycle to actions that enrich and nurture the profession. In 2023, NCAP will explore new ways that we can help break the self-harm cycle. We look forward to engaging with our members on this essential issue, for we are definitely stronger together.

Making Self-Care a Habit

By: Tina H. Thornhill PharmD, FASCP, BCGPWe often hear, “you cannot take care of others until you take care of yourself,” but what is “selfcare?” Self-care is “engaging in different activities to gain or maintain an optimal level of overall health that can add to your well-being.” Self-care should never be considered optional or indulgent. Instead, self-care should be done with intent (like the other items on your “to-do” list.)

Why is self-care essential?

According to the National Institute of Mental Health, self-care helps us live well and improves our physical and mental health. Do you frequently feel physically, emotionally, and mentally drained? If so, you probably need to pay more attention to an area of self-care that is trying to grab

your attention.

Without self-care, prolonged and chronic stress and physical, mental, and emotional fatigue are imminent. This puts your health at risk, you can become more easily frustrated and overwhelmed, and the simplest of tasks seem difficult to achieve, leading to poor productivity.

Focus areas for self-care

Depending on the reference, there are different areas of selfcare. The primary areas include: physical, psychological, emotional, financial, social, recreational, and spiritual.

The most important area is physical self-care. A deficiency in this area can negatively impact the other areas. What you have

learned as the “basics,” including exercising regularly, eating a well-balanced diet, and getting adequate sleep, are vital for your physical well-being. In addition to these, try implementing one or more of the following:

• Drink at least 8 oz of water as soon as you wake up.

• Get out in the sun and soak up some vitamin D.

• Spend time in nature.

• Take a hot shower or bath.

Mental self-care involves your mind’s ability to understand and process information and experiences. Psychological self-care improves your brain’s functionality, stimulates thoughtfulness, and helps develop a growth mindset. It helps us to process information more easily. Consider these psychological self-care activities

to boost your mental health.

• Journaling. (https:// www.betterup.com/blog/ how-to-start-journaling)

• Practicing gratitude. (https:// www.mindful.org/an-introduction-to-mindful-gratitude/)

• Set goals and priorities; decide what must be done now and what can wait.

• Take a social media holiday.

• Play a game or listen to music.

One of the more difficult areas for some of us is targeting our emotional self-care. It requires us to take an honest look at ourselves and our feelings. Our three basic emotional needs are autonomy (the need to feel that we have control over what we do), competence (the need to feel like we have done a good job), and relatedness (the need to have meaningful relationships and interactions with other people). Our emotions manage the expression of our feelings and, ultimately, our behavior. Try some of these emotional self-care activities to improve your emotional intelligence.

• Spending time by yourself with no distractions.

• Writing positive affirmations.

• Meditation. (https://www. nytimes.com/guides/well/ how-to-meditate)

• Connect with friends and family responsibly.

• Have a good cry.

Your environment should motivate, not distract, you; therefore, consider giving time to bolster your environmental self-care. Maintaining a space, at home or work, that is decluttered and

organized can go a long way to improving your self-care. Other ways to practice environmental self-care are:

• Exploring someplace new.

• Moving to a coffee shop, bookstore, or library to work.

• Set a calm mood in the hours before bedtime.

• Taking care of your surroundings.

Financial self-care may not be an area you have considered; however, having a healthy relationship with money is important for mental health as it can help reduce anxiety and stress. In addition to saving money, try these tips to help improve your financial self-care.

• Set financial goals.

• Sell items you no longer want or use (helps with environmental self-care, too).

• Deal with debt head-on. (https://consumer.gov/)

• Take note of your spending habits; stop emotional spending.

Self-care does not mean you have to spend time alone. Social selfcare results in your building and maintaining healthy interpersonal relationships. Social connectedness not only helps prevent loneliness but also strengthens our communication skills. Try some of these ideas to improve your social self-care.

• Limiting time with negative people.

• Asking for help when needed.

• Form new personal and professional relationships.

• Stay connected to important people in your life.

• Message someone telling them why they are important to you.

Recreational self-care means taking time out to have fun! Often this is where we play more and think less. What hobbies do you (or did you) enjoy? This type of self-care can be done alone or with others; it strictly depends on what you need. This website provides many suggestions for recreational self-care - https:// notesbythalia.com/recreationalself-care-ideas-to-cultivate-dailyfun/

Finally, there is spiritual selfcare. This self-care aims at finding hope and peace in challenging situations. What could be more personally and professionally desirable nowadays in our noisy lives? Practices in spiritual selfcare help define a deeper meaning or a sense of purpose for us. Suggestions for spiritual self-care are:

• Meditation.

• Yoga.

• Self-reflection.

• Attend a place of worship.

• Volunteer in the community.

We spend most of our day (and sometimes our evenings) caring for others. No one knows what you need more than you, so take a few minutes out of every day for your self-care. If that seems too ambitious, take 2-3 days out of your week (as a starting point) for self-care. Don’t let the start of something new stop you. If you are using some self-care activities, but do not feel that you are progressing, consider trying a different activity. After all, variety is the spice of life!

Implementation of a Sustainable Naloxone Service in Community Pharmacy Coordinated Through the Medium of Pharmacy Students Trained in Advanced Opioid Stewardship

By: Bethany Volkmar, PharmD CandidateIntroduction

According to the North Carolina Office of The Chief Medical Examiner, suspected overdose deaths in North Carolina reached 4,243 in 2022, up from 3,961 deaths in 2021.1 Between October 2021 and September 2022, fentanyl-positive overdose deaths reached 2,539, emphasizing the need for opioid harm reduction strategies to be implemented into the healthcare system2 With pharmacists being one of the most accessible healthcare providers, especially in rural North Carolina communities, counseling and dispensing of naloxone in community pharmacies has the potential to make a significant impact on reversing the increasing number of opioid overdose death trends we have seen over the last few years.

In North Carolina, any pharmacist practicing in the state and licensed with the NC Board of Pharmacy can dispense naloxone to persons under the State’s Standing Order 3 This includes persons who may need it for themselves, those who need it

for family members or friends, or those who may need it to assist another person at risk of experiencing an opioid overdose. A list of approved products for dispensing under the standing order includes naloxone nasal spray, intranasal syringes, injectable vials/syringes, and prefilled injectors.4

While several barriers exist to increasing naloxone distribution in the pharmacy setting, identifying patients at the highest risk and in need of naloxone is often considered by pharmacists as one of the biggest obstacles. The validated screening tools considered most favorable among pharmacists in streamlining the assessment of high-risk patients include the North Carolina Controlled Substances Reporting System’s Overdose Risk Score (ORS) and the Risk Index for Overdose or Serious Opioid-Induced Respiratory Depression (RIOSORD) screening tool.

The Overdose Risk Score (ORS) available in the North Carolina Controlled Substances Reporting System (NC CSRS) stratifies a

patient’s risk of overdose based on the number of prescribers, number of pharmacies, morphine equivalent dose, and overlapping prescriptions in a patient’s controlled substance fill history.5 Scores range from 0-999, with higher numbers indicating an increased risk of unintentional overdose. Most importantly, pharmacists can access the CSRS to view an ORS score within seconds. Any score above 450 indicates an elevated risk of unintentional overdose and a need for naloxone.5

The Risk Index for Overdose or Serious Opioid-induced Respiratory Depression (RIOSORD) is a 17-item validated screen pharmacists can use independently or as a complement to the CSRS when the ORS score falls below 450.6 Unlike the ORS, the RIOSORD accounts for other relevant factors contributing to overdoses, such as conditions known to compromise pulmonary function, other mental health conditions, and concomitant use of medications known to cause drug accumulation and toxicity resulting from impaired opioid

metabolism or clearance.6 Beyond the efficiency, the appeal of this tool is that pharmacy staff can glean most of the information required in this screen simply by reviewing the patient’s medication history. Scores totaling 25 or more points represent the greatest opportunity for pharmacists to counsel and convey the benefits of carrying naloxone to their patients should they experience an opioid emergency.

Finally, the emergency action plan is an excellent tool for pharmacists to convey necessary counseling in a strategic and time-efficient manner.7 Similar to an Asthma Action Plan, the Opioid Action Plan, as seen in Figure 1, provides a place for pharmacists to list a patient’s risk factors that could predispose them to an opioid emergency. It covers essential counseling tips, such as signs of an opioid emergency, and instructions regarding the actions and administration steps for giving naloxone. In addition, since pharmacists can provide it to patients to take home, it is an excellent resource to reinforce the counseling a patient receives at the pharmacy and helps patients train others should they become unconscious and need assistance. For access to the abovementioned tools and more information on the use of naloxone, visit the North Carolina Association of Pharmacists Naloxone to the Rescue Toolkit 7

a naloxone service model incorporating the use of these tools to identify patients at high risk that could benefit from receiving naloxone.

Methods

The service model development employing the CSRS Overdose Risk Score (ORS), the RIOSORD, and the Opioid Emergency Action Plan occurred at the Pharmacy between October 17th-26th, 2022, after an initial two weeks of shadowing, training, and workflow development. To collect additional data and test the service model’s functionality across multiple sites, a day to monitor the service at a secondary pharmacy location was also scheduled due to their high volume of opioid dispensing.

In October of 2022, a fourth-year PharmD candidate from UNC Eshelman School of Pharmacy completed an NCAP Opioid Stewardship APPE Elective partnering with a pharmacy site to develop

During the first week of the rotation, the student pharmacist worked to understand better the patient population, staff, and their roles to gauge how a new naloxone service might fit into the pharmacy’s existing workflow. The patient population for this outpatient pharmacy was primarily those with post-operative needs and, upon further inspection, in most cases, were opioid naïve. Early shadowing identified pharmacists as the point persons for the initial receipt and order entry of opioid prescriptions, with a process already in place for checking the CSRS. Providing education on the CSRS (ORS) tool and assimilating its use into the established process proved easy, ultimately saving pharmacists time in their CSRS review. During the filling process, the student pharmacist

observed that technicians have quick access to the patient’s medication list, which proved a suitable place for using the RIOSORD if warranted. Based on observational findings, the remainder of the week was dedicated to creating a workflow the staff could try to test the efficiency of the naloxone service model, from performing the risk assessment to counseling and processing of naloxone for eligible candidates. In week two, the primary focus centered around training staff on the appropriate use and interpretation of the ORS and RIOSORD screening tools and capturing metrics to evaluate the number of patients screened, those deemed high-risk, and whether those at risk received naloxone. The pharmacists also reviewed the Opioid Emergency Action Plan and discussed best practices for counseling at patient pick-up.

In week three, the student pharmacist worked with the staff in implementing a soft launch of the service to test the workflow, guiding the pharmacy team throughout the process. See workflow algorithm Figure 2.

In the initial verification process, the pharmacist receives the opioid prescription and verifies the patient’s risk of overdose based on the CSRS’s Opioid Risk Score (ORS). Patients with scores at or below 200 are considered low risk for unintentional overdose death and, thus, require no further assessment. For scores at or above 450, the pharmacist enters the score into the clinical note and automatically processes a prescription for naloxone per the NC Standing Order if the patient

has no record of receiving naloxone in the last year. The pharmacist also fills out the patient’s Opioid Emergency Action Plan and counsels the patient at pickup, hoping the patient will be amenable to accepting the naloxone post-counseling. ORS Scores between 200 and 449 represent a gray area where the risk of overdose and need for naloxone may be less noticeable. For patients with scores in this range, the pharmacists will enter the ORS into the clinical note prompting the technician to employ the RIOSORD tool further to confirm risks and the need for naloxone. Any RIOSORD scores reportedly at or above 25, correlating with a 14% higher risk of opioid-induced respiratory depression, the technician will enter the score to the clinical note, again prompting the pharmacist to enter a naloxone prescription in the system, complete the patient’s emergency action plan and provide counseling at patient pick-up. Any naloxone prescription refused by the patient after counseling is returned to stock.

In week four, the student pharmacist discussed workflow efficiency and the results of data collected during the test implementation period with the pharmacy staff. Metrics used to analyze the value of the service included a review of the pharmacy’s dispensing report for a comparison of both opioid and naloxone dispensing. The results of the ORS and RIOSORD screens were manually tallied during the rotation. In addition, the pharmacy staff manually recorded the outcomes of each counseling attempt to capture a patient’s

acceptance or refusal of naloxone. By week’s end, a sustainable service model, complete with workflow and a standardized operating procedure, was made available to the pharmacy staff.

The one day spent at the secondary pharmacy location went similarly, except the student pharmacist worked independently with the order entry pharmacists in carrying out the service at this location to test the efficiency of the workflow at this site.

Results

At the primary pharmacy location, 114 opioid prescriptions and three naloxone prescriptions were recorded and dispensed during implementation. See Table 1. One patient accepted the naloxone prescription and was counseled using the Opioid Emergency Action Plan.

During the one day spent at the secondary site, 30 opioids and four naloxone prescriptions were dispensed. Two naloxone prescriptions were co-prescribed alongside buprenorphine and naloxone (Suboxone) in patients treated for Opioid Use Disorder. Therefore, they were omitted in the analysis and Table 2 since they were not assessed for risk using the pharmacy’s service model. One patient declined naloxone at pick up during the collection period, with no data regarding the acceptance or decline of the other three naloxone prescriptions dispensed as patient pickup had not occurred before the conclusion of the student’s time at this site.

Discussion

Although results showed few patients were “high risk” at the primary pharmacy location, the service model and its screening tools still fashioned an efficient means for pharmacists to quickly assess and identify those needing naloxone, circumventing a known barrier to enhancing naloxone access in the pharmacy community. These validated screening tools were also skillfully embedded within pharmacy workflow. More patients were identified as highrisk at the secondary site, where prescription volume was much higher, allowing for appropriate intervention at prescription pickup.

Comments from host sites were positive, with pharmacy technicians expressing pride in helping identify patients at risk for harm. Administration, staff pharmacist, and technicians confirmed their desire to continue the service model and supported the expansion of the model system-wide. The next step would be to evaluate whether the screening tools can be embedded within the electronic health record to assess overdose risk electronically rather than initiating screenings manually to improve efficiency and expand interventions.

Barriers to patients accepting naloxone included cost, especially in those uninsured or with a high copay, the stigma around naloxone, and the information asymmetry on the dangers of opioids even when taken as prescribed. While the ORS and RIOSORD aided in identifying high-risk patients, the Opioid

Emergency Action Plan proved valuable in improving patient knowledge about the signs of an overdose and the use of a naloxone product. It is crucial for pharmacists to counsel patients in a non-judgmental way and to articulate that everyone is at risk of having a breathing emergency to reduce stigma. This tool helped pharmacists carry out patient-centered counseling in a time-efficient manner and through conversation that fostered a non-stigmatizing, judgment-free environment.

There were limitations to data collection. The collection period

was short. With 30 days in the rotation period and the time to fully operationalize the service, data was only collected for ten days. It was concluded that medications excluded from the ORS and RIOSORD, such as muscle relaxers, gabapentin, and other sedatives, could potentially omit a population of high-risk patients. The addition of other screening assessments could help identify outliers. Still, implementation in the community pharmacy must be quick to ensure the service’s sustainability.

The study did lay the groundwork for implementing harm-re-

duction screening tools in community pharmacies to reduce the increasing number of unintentional opioid overdoses in the state. A longer data collection period would allow for more robust data and potentially identify naloxone distribution effects on clinical outcomes in this setting.

References

1. OCME Suspected Overdose Deaths Report. NCDHHS. 2023. https:// injuryfreenc.dph.ncdhhs.gov/DataSurveillance/StatewideOverdoseSurveillanceReports/OpioidOverdoseEDVisitsMonthlyReports/ OCMEMonthlySuspectedOD_Report-Dec22.pdf

2. OCME Fentanyl-Positive Deaths. NCDHHS. 2023. https://injuryfreenc. dph.ncdhhs.gov/DataSurveillance/ StatewideOverdoseSurveillanceReports/OpioidOverdoseEDVisitsMonthlyReports/OCMEFentanylReport_dec22.pdf

3. North Carolina State Health Director’s Naloxone Standing Order for Pharmacists. NCDHHS. 2022. https://www.dph.ncdhhs.gov/ docs/NCNaloxoneStandingOrderforPharmacistsMarch2022.pdf

4. List of Approved Naloxone Products for Pharmacist Dispensing. NCDHHS. 2022. https://www.dph.ncdhhs. gov/docs/NaloxoneProductsforPharmacistDispensing.pdf

5. NC Controlled Substances Reporting System. NC DHHS. https:// www.ncdhhs.gov/divisions/ mental-health-developmental-disabilities-and-substance-abuse/ north-carolina-drug-control-unit/ nc-controlled-substances-reporting-system

6. Zedler B, Xie L, Wang L, et al. Development of a Risk Index for Serious Prescription Opioid-Induced Respiratory Depression or Overdose in Veterans’ Health Administration Patients. Pain Med. 2015;16(8):15661579. doi:10.1111/pme.12777

7. Naloxone To the Rescue Toolkit. NCAP. 2022. https://ncap. memberclicks.net/naloxone-service-rp

* Patients received a Narcan prescription in the last 12 months.

International Pharmacy Rotation: Experiencing Healthcare & Culture in Honduras

By: Nancy Tran, PharmD Candidate Kristian Catahan, PharmD Candidate Dr. Carrie L. GriffithsGuachipilincito is a remote rural village in Southwestern Honduras in the state of Intibucá. This community is very poor, with most earning around $10 per day. The climate is tropical, with a rainy season in the fall. We had the privilege of doing an international Advanced Pharmacy Practice Experience (APPE) rotation in Guachi, Honduras. This opportunity is offered three times a year (February, June, and October) to Wingate University School of Pharmacy. These are the times of year the medical brigade travels to Guachi. Senior pharmacy students (max of 2 per brigade) and a faculty preceptor accompany a one-week medical brigade organized by Shoulder to Shoulder. Shoulder to Shoulder is a non-profit organization that collaborates with healthcare workers and community leaders to improve the quality of life of rural Hondurans. Their goal is to provide accessible healthcare to the people of Guachi by providing care for chronic disease states such as hypertension and diabetes. The medical brigades consist of at least one physician,

one pharmacist, and other medical professionals such as dentists, nurses, physical therapists, and learners at all levels. Anyone can volunteer to serve on a brigade, including pharmacy technicians and non-medical volunteers. Some in-country physicians and nurses will volunteer their time if able.

The clinic can see patients Monday through Thursday during the week-long medical brigade. This includes providing care to patients that come to the clinic, currently by appointment, and providing home visits to special needs children or elderly patients who cannot travel to the clinic.

In preparation for our trip, we met online with our brigade team. When we saw the recommended packing list (e.g., toilet paper, a mosquito net, a flashlight, a reusable water bottle, a clothesline, bed sheets, etc.), we knew our living conditions for the week would be sparse. However, only when we arrived in Honduras could we appreciate the drastic differences in our

surroundings compared to the United States (U.S.). For example, roads were not paved and were filled with ruts. Additionally, adults and children frequently approached us to sell us various products to make money.

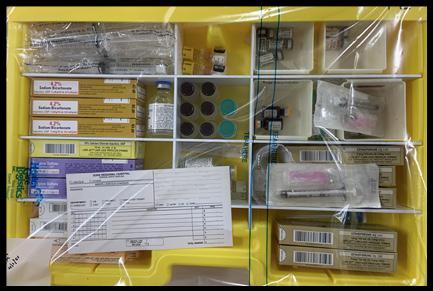

In America, access to healthcare is a right, but in Guachi, healthcare access is more of a privilege. Some patients must travel far to the clinic, some pay for taxis, and some walk for over an hour. Patients came to the clinic in their best clothing and were excited to see us even when they were acutely ill. The people of Guachi emphasized how grateful they were for each member working in the clinic. Everyone seemed incredibly grateful to be at the clinic, from Iris, Health Promoter, in the registration area, to William or Alan, interpreters provided by Shoulder to Shoulder, interpreting for the doctors, to the pharmacy team counseling every patient. It almost seemed like everyone came to celebrate. The patients celebrated having access to a physician and receiving free medications. Medications were provided to minimize symptoms, control chronic conditions, and help stock their home medicine cabinets. (Figure 1) The pharmacy’s formulary was limited to essential medications, many of which are included in the World Health Organization Model List of Essential Medications. (https:// list.essentialmeds.org/) All dispensed medications were free of charge to the patient. Each prescription was filled for a 120-day supply to last them until the next brigade. Figure 2 shows our team preparing and pre-packaging medications.

Neither the clinic nor the pharmacy operated using computers. Instead, patient charts and documentation were all hand-written on paper. Our preceptor walked us through how to read the charts and the doctor’s handwriting. We used extra care when reading the prescriptions to avoid misreading a medication or instructions. Prescription labels were handwritten in Spanish. Filling and verifying prescriptions took longer than anticipated without the usual resources available in the U.S. We found ourselves referencing the Spanish dictionary and physical LexicompⓇ book when needed due to the lack of internet access.

There was no electricity for two days during the week in our living area or clinic. We had to fill prescriptions using the tiny sliver of light provided by the 2 x 4-foot window or a small flashlight. Working in hot temperatures with little light made working more difficult and stressful. In the U.S., we take the reliability of electricity for granted, giving us lights and air conditioning. Figures 3 and 4 show the small space available for the pharmacy.

We had plenty of opportunities to interact directly with patients. Before the trip, we took a medical Spanish class where we learned essential vocabulary to communicate with patients in a pharmacy setting. We counseled over 100 patients within the week, but it was challenging even with the help of interpreters. They sometimes repeat incorrect instructions when asking patients to “teach back” how to use their new medications. At the same time, some patients got confused about their medicines due to only recognizing them by their color and shape. As the week progressed, our Spanish improved, and we spoke more confidently. Eventually, we had moments where the entire conversation was spoken in Spanish without the interpreter.

One day, we visited an elementary school to educate children about dental hygiene (Figure 5), including how to brush their teeth properly. Since dental care is scarce, many have cavities, crowns, or missing teeth. We administered fluoride treatments and gave them toothbrushes.

Every time we went on a home visit, we had to walk through the different landscapes carefully. Each patient we saw lived in a

house at the bottom of a steep hill causing us to wonder how the residents of Guachi walk long and strenuous distances without having proper footwear. Many women wore plastic shoes that were Croc-like or flip-flops, while men typically wore boots or flip-flops. Everyone who walked by the clinic or our Shoulder to Shoulder trucks seemed unphased by having to walk such long distances. They did not appear uncomfortable or unhappy. To them, it was normal. It was a similar situation with the patients who traveled to the clinic— they even came in the pouring rain!

As we reflect on our APPE experience in Honduras, we have a stronger appreciation for what we used to take for granted, such as technology and electricity, but also healthcare and medication access and availability. Even the most basic of items, such as a toothbrush, is a commodity for many. This experience taught us how to adapt quickly to a new environment and the importance of interprofessional collaboration. It reemphasized the importance of good communication and showed us that stepping out of your comfort zone is okay while attempting to counsel patients who speak a different language. We saw that a fast-paced pharmacy work environment occurs in rural, remote areas of Honduras. Communicating with the healthcare team and taking breaks to relieve anxiety or stress is always important for minimizing errors no matter where you work! We also realized that even through times that seemed super busy at the clinic, every healthcare provider and volunteer made the time to

ensure each patient was cared for and made to feel important. This seemingly small gesture greatly impacted our patients and the overall work environment.

To a student interested in an international rotation or a pharmacist who wants to work abroad, we feel confident in proclaiming, “the experience is unlike any other!” This trip reminded us to take a step back, breathe, and remember “why” we wanted to pursue pharmacy as a career. We will use this experience to recognize health disparities and minimize the differences through our care.

Authors: Nancy Tran, PharmD Candidate, Class of 2023, Wingate University School of Pharmacy; Kristian Catahan, PharmD Candidate, Class of 2023, Wingate University School of Pharmacy, and Carrie L. Griffiths, PharmD, BCCCP, FCCM (corresponding author), Associate Professor, Wingate University School of Pharmacy, Levine College of Health Sciences, Wingate, NC 28174; clgriffiths@wingate.edu.

Sponsors and Exhibitors

Don’t miss out on a chance to promote your products, meet potential customers, and generate new leads. We have packages to best fit your needs so you can gain visibility and recognition in the pharmacy industry. Click here for the Exhibitor Prospectus and additional information that you may need. We have limited spaces available. Send in the Exhibitor and Sponsorship Agreement Form to save your spot. If you have any questions or additional needs contact Rhonda Horner-Davis at rhonda@ncpharmacists.org. Thank you for your support!

160 Business Park Circle, Stoughton, WI 53589 Phone: 888.870.7227 or 608.873.1342

count card transactions are for branded products. For Medicare patients, nearly 1 in 5 (19%) used a discount card. Commercial patients were 12%, but that doubled to 24% for those with an observed deductible. Cash paying patients represented 56% of all patients, and 52% of transactions.

Discount/Cash Cards Are Disruptors in the Industry

On February 25, 2023, PAAS National, had the privilege of participating in a Panel Discussion entitled Marketplace Prescription Dynamics Sure to Shape Your Business Strategies at NCPA Multiple Locations Conference. While traversing several different topic areas, one of the core issues important to community pharmacies is discount/cash cards.

IQVIA published a white paper entitled Pharmacy Discount Card Utilization and Impact1 in August of 2022 with several interesting findings. Among them, discount card utilization has grown to 5.4% of all pharmacy adjudications in 2021, a 63% increase over 2017 - of which “Not So GoodRx” now represents 46%. Only 9% of dis-

While the discount card growth has been remarkable, what makes them disruptors in the industry has been their impact on the traditional PBM model. Discount cards have been effective at undermining the perceived benefit that PBMs are supposed to provide (i.e., why is GoodRx able to offer a better price on my prescriptions than my insurance). Additionally, patients’ out of pocket costs are typically not captured when they use discount cards unless a patient is going to submit claims on their own (in addition to gaps in adherence metrics and other quality measures). In response, Express Scripts announced2 a partnership with GoodRx to include a “lesser of” logic when processing prescription claims through their Price Assure program. Not to be outdone, OptumRx launched Price Edge3 which will review direct-to-consumer prescription drug prices and offer members the lowest available price. Comically, OptumRx said they currently offer the best price to their members about 90% of the time, meaning 10% of the time patients are getting a raw deal. Both of these programs are automatically including these drug purchases into member’s deductibles going forward.

Pharmacies know4 that discount cards are really just another

form of spread pricing, benefiting the discount card provider and PBM. GoodRx reports that it earns 15% of the patient’s total retail prescription cost, and that doesn’t include a fee for the PBM processor. Interestingly, GoodRx had disclosed that Kroger had accounted for only 5% of participating pharmacies, but nearly 25% of prescription transaction revenue. How could it have been that high? As a chain, Kroger was more likely dutiful in their utilization and/or promotion of GoodRx for patients. Most independents despise GoodRx and will create work arounds to avoid utilizing the card (e.g., with aggressive cash pricing or price-matching). Pharmacies should always be careful not to jeopardize their usual and customary. With the integration from these new programs by the PBMs, bypassing discount cards will likely no longer be an option for insured patients. The impact on BER, GER and even DIR fees for 2023, and beyond, are not clear.

Speaking of jeopardizing your Usual & Customary pricing, Amazon’s RxPass5 should be a flop. If you haven’t heard or read about it, Amazon is offering their Prime members “eligible medications for one flat, low monthly fee of $5, and have them delivered free of charge”. Patients with Medicare, Medicaid, or located in one of the seven states they exclude are not eligible to participate. The broader question is how long it will take the DOJ and HHS-OIG to enforce the U&C issue that has already played out with Walgreens (and many others). PAAS previously illuminated the $60 million settlement with the Prescription Savings Club in the March 2019

PAAS Newsline: AVOID “Discount Clubs” for Cash Patients6. That same DOJ announcement7 also discussed the infamous Insulin Pen Box Settlement for $200 million. Amazon clearly missed this settlement, as the PillPack subsidiary paid a $5.79 million settlement8 in May 2022 for the same insulin pen dispensing practices.

PAAS National® is committed to serving community pharmacies and helping keep hard-earned money where it belongs. Contact PAAS today at (608) 873-1342 or info@paasnational.com to see why PAAS Audit Assistance membership might be right for you.

By Trenton Thiede, PharmD,

By Trenton Thiede, PharmD,

MBA, President at PAAS National®, expert third party audit assistance and FWA/HIPAA compliance.

Copyright © 2023 PAAS National,

LLC. Unauthorized use or distribution prohibited. All use subject to terms at https://paasnational. com/terms-of-use/

References:

1. https://www.iqvia.com/locations/united-states/library/ white-papers/pharmacy-discount-card-utilization-and-impact

2. https://www.evernorth.com/ articles/increased-pharmacy-savings-and-affordable-prescription-medication

3. https://www.optum.com/ about-us/news/page.hub.optumrx-price-edge-for-best-prescription-price.html

4. https://www.drugchannels. net/2022/05/the-goodrx-kroger-blowup-spread-pricing. html

5. https://pharmacy.amazon. com/rxpass

6. https://portal.paasnational. com/Paas/Newsletter/Go/553

7. https://www.justice.gov/ usao-sdny/pr/manhattan-us-attorney-announces-2692-million-recovery-walgreens-two-civil-healthcare

8. https://www.justice.gov/ usao-sdny/pr/us-attorney-announces-settlement-fraud-lawsuit-against-online-pharmacy-overdispensing

Discounts on Home, Travel, and Entertainment

All members have access to exclusive savings on home-based services and shopping, movie tickets, theme parks, hotels, tours, Broadway and Vegas shows, and much more.

www.workingadvantage.com

Cracking the Code: Emergency Drug Cart Stocking Practices in North Carolina Hospitals

By:

Dr. Meghan E. Peterson

Dr. Greene Shepherd

By:

Dr. Meghan E. Peterson

Dr. Greene Shepherd

Abstract

Background Emergency drug carts (EDC) have become a cornerstone in hospitals throughout the world. An EDC is a self-contained mobile unit that houses essential medications and equipment most frequently used in various emergency situations. Although the role of EDCs is well established, medication stocking trends and practices are less defined.

Objective To increase knowledge surrounding EDC medication stocking trends and practices in hospitals throughout North Carolina.

Methods This observational cohort study was conducted utilizing telephone and electronic surveys with key pharmacy team members at 97 health systems throughout North Carolina from August 2020 to February 2021. All hospitals in North Carolina were eligible for participation, and there were no exclusion

criteria. Descriptive statistics were utilized for the analysis of demographics and stocked medication. Data from each hospital were compared to determine similarities and differences in medication contents and stocking practices.

Results A 77% (97/126) response rate was achieved, and 84 of 97 hospitals surveyed provided adult EDC content lists. On average EDCs contained 17 medications. A total of 33 different medications were stocked across hospitals with varying concentrations. Results also indicate that medication stocking aligned with evidence-based practice guidelines for Advanced Cardiovascular Life Support (ACLS), as 100% of hospitals stocked amiodarone and epinephrine in their adult EDCs. Restocking practices were wide-ranging, with numerous methods deployed for cart security, monitoring, expiration dates, and replenishing times.

Conclusion These results indicate that EDC medication stocking varies greatly between hospitals in North Carolina; however, evidenced-based guidelines are upheld at all surveyed hospitals.

Introduction

In 2018 there were an estimated 200,000 cases of in-hospital cardiac arrest, with successful resuscitation dependent on high-quality cardiopulmonary resuscitation, team speed, and medication administration.1,2 Survival to discharge following in-hospital cardiac arrest ranges between 15-20%.3,4 When a patient is in cardiac arrest, each minute resuscitation is delayed can lead to a 7%-10% reduction in survival.5 In an effort to increase rapid access to medications and equipment needed in cardiac arrest, Emergency Drug Carts (EDCs) have become a cornerstone in hospitals throughout the world. An EDC is a self-contained, mobile, multi-draw-

ered unit that houses essential medications and equipment most frequently used in a wide array of emergency situations.2 Such contents are easily deployed to the location of the emergency to allow for rapid response and treatment. As emergency situations can occur throughout the hospital at any time, responders’ ability to rapidly access vital equipment and medications is important. Because medications can be stored in EDCs, automated dispensing cabinets, or within the pharmacy, responders need to know where the needed medications are located. As variability increases, medication retrieval time and incidence of errors rise, which may ultimately result in decreased patient survival.6

The Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) states that the pharmacy should control all emergency medication supplies.7 Additionally, JCAHO states that “hospital leaders, in conjunction with members of the medical staff and licensed independent practitioners, decide which emergency medications and their associated supplies will be readily accessible in patient care areas based on the population served.” 7 From this, it is evident that medication stocking responsibility lies in the department of pharmacy in conjunction with hospital administrators and practitioners, but little is known about how this is achieved.

Limited reports are published on EDC stocking practices, with only four articles published since 1972. The first report describing an EDC was published by Inquiry in 1972 and narrated how the trolley has been in use since 1963 “to over-

come the difficulties and delays which often arise when a seriously ill or injured patient is admitted to the hospital, and the appropriate resuscitation equipment is not ready to hand.” 8 The second was published in 1995 and described a “pediatric care and resuscitation cart” used in a community hospital in Massachusetts.9 The article briefly discussed medication contents; however, no additional comments were made regarding medication use, stocking practices, or cart layout.

Nearly 20 years later, the W21C Research and Innovation Centre at the University of Calgary, Canada, published a two-phase study of EDC medication use in the Emergency Department (ED) with goals to develop a comprehensive list of EDC medications and observe stocking processes. Three hospital EDs were enrolled in the study, and multiple live visits were conducted in order to obtain drug inventories, workflow practices, and photographs. While contents varied between hospitals, 16 medications were present at all three sites2. Although commonalities were seen, the article noted that variability was still evident and that fundamental differences in the hospital patient population may have contributed to the large variability.

Finally, Jaquet et al published a systematic review where four articles were detailed, including two described above.5 Additionally, emphasis was placed on the disparity of research surrounding EDCs, even though they play a vital role in our hospitals. In addition to the review, suggested EDC contents were recommended by Jaquet; however, a rationale was

not provided. It was suggested that medications to treat emergency situations such as cardiac arrest, tachyarrhythmia with a pulse, hypertensive emergencies, allergic reactions, acute exacerbations of respiratory diseases, overdoses, and seizures be included within the first two drawers of the EDC. Overall, 36 medications were suggested, with detailed locations present for each medication within the mock EDC.

Lack of standardization and literature to support EDC stocking practices may lead to variability in stocked medications. JCAHO provides little guidance on EDC stocking, with only reference regarding developing a standard stock of medications and supplies for EDCs which should be re-evaluated periodically. As a result, hospitals must use a variety of practice guidelines in combination with clinical judgment in order to determine their facility’s EDC stocking practices.

The 2020 American Heart Association Update for Advanced Cardiac Life Support, Pediatric Advanced Life Support, and Neonatal Life Support (ACLS/PALS/NLS) Guidelines highlight a wide range of medications that can be administered during cardiac arrest. While use varies based on patient presentation, all medications should be easily accessible when needed.10 Recommended medications include: epinephrine, amiodarone, lidocaine, atropine, adenosine, dextrose, calcium, and magnesium.11-13 Post-arrest medications include epinephrine, norepinephrine, phenylephrine, dopamine, dobutamine, or milrinone.11-13 Medications for rapid sequence intubation, such as sedatives and

neuromuscular blocking agents, should also be included.12

EDC variability amongst hospitals is likely as emergency scenarios to vary based on hospital type; however, overall trends in ACLS medications should be present. In order to describe what variability is present, it was necessary to gather data on current hospital practices. An inclusive survey of hospitals in North Carolina was undertaken to identify current medication contents and stocking practices. Through this quality improvement project, we aimed to greatly increase the knowledge surrounding EDC stocking practices to describe common medication trends and establish replenishing practices.

Methods

This study underwent application, review, and approval by the pharmacy school educational research committee and also received an IRB exemption.

Survey Development

Survey creation began by performing a systematic literature search via Pubmed (https://www. ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/) and Embase (http://www.embase. com) in order to obtain literature surrounding current trends in hospital EDC stocking practices. Search terms utilized for Pubmed and Embase can be found in Table S1. Our search revealed that no new literature has been published about hospital EDCs since Jacquet et al. published a systematic review in 2018.

edge and survey development. Survey questions were developed based on previous literature and adapted for use in this study. The survey was reviewed by four hospital pharmacists for completion, answerability, and question clarity prior to dissemination. The survey consisted of 24 questions and was estimated to take 15 minutes to complete.

Survey Dissemination and Descriptive Statistics

In order to obtain a large representative sample size, a list of hospitals compiled by the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services was utilized.14 This list included hospitals in North Carolina and key descriptors such as the county and the total bed count. Veterans Affairs hospitals operating in North Carolina were not included in this initial list but were added to the dataset for completeness. The United States Office of Management and Budget delineation of metropolitan and micropolitan designations guided the classification of rural and urban counties, which was compiled in a reference document by the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services.15 All hospitals in North Carolina were eligible for participation, and there were no exclusion criteria.

complete the survey. The remaining hospitals were not contacted if EDC stocking practices were standardized throughout the system. However, if EDC stocking was not standardized throughout the hospital system, each hospital was contacted individually.

Hospitals were contacted by phone and connected to an inpatient pharmacy via a hospital operator. The surveyor was then connected to a pharmacy technician, pharmacy administrator, or pharmacist who was most knowledgeable of EDC stocking practices. The preferred survey completion method was telephone; however, due to employee schedule and availability, surveys were also sent via email and completed via QualtricsÒ. While this increased the risk of partial responses, it was decided that all completed questions would be taken into consideration for final data analysis. Hospitals were also asked to submit a photo of their EDC layout to allow for a more complete picture of practices; however, this was not required for survey completion.

The literature review provided a foundation for baseline knowl-

For this project, 126 hospitals were invited to participate. The flagship hospital was contacted first to obtain survey information for hospitals that were part of a hospital system. However, if the flagship hospital was unable to be contacted or denied participation, an alternative hospital within the hospital system was contacted to

In order to achieve a 5% margin of error with a 95% confidence interval, 94 hospitals were needed to participate in this study. Data analysis included descriptive statistics for demographic and medication content analysis, while nominal data were reviewed for trends.

Results Survey Response

Data collection was performed between August 2020 and February 2021, and all hospitals in North Carolina were attempted to

be contacted. After survey completion, the number of hospitals participating was N = 97, yielding a 77% response rate. Medication lists for adult/universal EDCs were unable to be obtained from 13 hospitals. Nineteen hospitals did not provide pediatric medication lists, and 35 hospitals did not provide neonatal EDC medication contents even though they reported utilizing two or more EDC layouts. All other survey questions were answered in full. No respondents were excluded from this study.

Demographics of participating hospitals can be found in Table 1. Most respondents were located in urban areas and were members of a hospital system. Hospital bed count varied greatly (6 to 979 beds, with a median of 114 beds). The majority of hospitals (87.6%) were not a designated trauma center (Level 1, Level 2, or Level 3). There are no freestanding children’s hospitals in North Carolina.

The adult/universal EDC medications stocked regardless of concentration can be found in Figure 1. Independent of concentration, 100% of surveyed hospitals stocked amiodarone, epinephrine, and sodium bicarbonate in their adult/ universal EDCs. More than 75% of hospitals stocked adenosine (97.6%), atropine (98.8%), dextrose (85.7%), dopamine (88.1%), lidocaine (88.1%), magnesium sulfate (85.7%), and norepinephrine (83.3%). The remaining 23 stocked medications were found in less than 75% of the hospital’s EDCs. The average number of stocked medications was 17± 6.

utilizing a pediatric-specific EDC and/or neonatal EDC or code bag. The pediatric and neonatal EDC medications stocked regardless of concentration can be found in the supplemental appendix as Figure S1 (pediatric) and Figure S2 (neonatal). Independent of concentration, 100% of hospitals stocked epinephrine and lidocaine in their pediatric EDC. More than 75% of hospitals stocked adenosine (98%), amiodarone (96%), atropine (98%), calcium chloride (93%), dextrose (98%), naloxone (81%), and sodium bicarbonate (98%). No medications were consistent in all surveyed neonatal EDCs. Ninety-seven percent of hospitals stocked epinephrine, while the remaining 13 medications were stocked in fewer than 75% of neonatal EDCs. The average number of stocked medications in the pediatric EDC was 20 ± 9, while neonatal EDCs stocked on average 5 ± 3 medications. A full list of stocked medications in surveyed pediatric and neonatal hospitals can be found in the supplemental appendix as Table S2.

Hospitals kept, on average, seven emergency drug carts or trays in reserve for backup use when a cart is used. Nearly all hospitals reported utilizing some form of EDC content security, such as breakaway locks, RFID technology, or plastic-wrapped trays. At the same time, half of the hospitals reported using a combination of locking strategies.

Once carts have left the pharmacy, there is evidence of interdisciplinary monitoring by materials management, pharmacy, and nursing staff with a variety of daily, weekly, and monthly inspection strategies deployed. Following a code, an EDC was able to be replenished within 15-120 minutes, with the majority of hospitals replacing an EDC within 60 minutes of cart return to pharmacy or materials management.

Pediatric and neonatal EDC data was collected with 73 hospitals

Of note, concentrations of stocked medications varied greatly in adult/universal, pediatric, and neonatal EDCs, with some hospitals stocking multiple concentrations of a medication within the EDC. Medication breakdown by concentration can be found in the supplemental appendix as Table S2. EDC stocking practices by facility are described in Table 2. Threefourths of hospitals report utilizing two or more EDC layouts, most commonly being adult and pediatric. Selected images of EDCs can be found in the supplemental information. The median EDC count was 30 carts per hospital, with a range of 3-297 carts per hospital.

Every hospital reported that the pharmacy managed EDC medication restocking. The majority of hospitals have built EDC management into normal workflow and utilize pharmacy technicians to perform EDC tray restocking, which is then checked by a pharmacist. The average expiration date utilized is three months in the future; however, all hospitals reported a desire to have longer expiration dates to reduce work demand. Additionally, medication shortage management was reported by most hospitals as a barrier to maintaining a three-month advanced expiration date.

Furthermore, 51.5% of hospitals reported pharmacist involvement during code blue resuscitation efforts. All hospitals utilize stakeholder input and guideline changes

to update and revise EDC contents, with reviews occurring as often as quarterly or on an as needed basis.

Discussion

EDCs are used in emergent situations in order to allow rapid access to life-saving equipment and therapies. The results of this survey indicate significant variability in EDC medication contents and stocking procedures in hospitals throughout North Carolina. Furthermore, the extremely outdated and limited literature describing medication contents and stocking practices of EDCs indicates a need for further studies.

The 2020 American Heart Association Update for ACLS/PALS Guidelines highlights a wide range of medications that can be administered during cardiac arrest. Of the recommended ACLS medications stocked in adult/universal EDCs, our study found that 100% of hospitals stocked epinephrine and amiodarone, 98.8% stocked atropine, 88.1% of hospitals stocked lidocaine and dopamine, and 97.6% of hospitals stocked adenosine. PALS guidelines recommend the use of epinephrine, amiodarone, or lidocaine for use in pediatric cardiac arrest. Our study found that in pediatric EDCs, 100% of surveyed hospitals stocked epinephrine and lidocaine, and 96% of hospitals stocked amiodarone. Additional medications recommended for PALS include atropine and adenosine, with 98% of hospitals surveyed stocking adenosine and atropine, respectively, within their pediatric EDC. It is noteworthy that about 10% of surveyed hospitals stocked vasopressin which is no longer included in the ACLS algorithm.

Based on these medication stocking practices, it is evident that essential medications that are rapidly accessible in an emergent situation are most often stocked in EDCs. Current ACLS/PALS guidelines have multiple agents recommended for the treatment of certain conditions. For example, the algorithm for ventricular fibrillation or pulseless ventricular tachycardia recommends the administration of either lidocaine or amiodarone following three rounds of CPR.10-12

While there are guidelines indicating essential medications for use during a code, other medical emergencies have less straightforward guidelines. For example, the World Allergy Association highlights the importance of epinephrine for the treatment of anaphylaxis as it is the only medication that reduces hospitalization and death.16 When used for anaphylaxis, it is typically administered via the intramuscular route, which may lead to carts including multiple concentrations or dosage forms of epinephrine. The Neurocritical Care Society Guidelines for the Evaluation and Management of Status Epilepticus recommends the use of valproate, phenytoin/fosphenytoin, levetiracetam, or phenobarbital for the urgent treatment of status epilepticus.17 Hydrocortisone is often included for use in refractory hypotension and suspected adrenal crisis.18 These treatment guidelines do not specifically recommend whether or not such medications should be included in EDCs or made available through other mechanisms such as automated dispensing cabinets or STAT pharmacy orders. As such, clinical judgment and individual hospital policy

are often utilized, thus leading to variability between hospitals.

Numerous concentrations of medications were notably present in EDCs. Guidelines, however, only recommend a specific dose; therefore, any vial size may be used as long as the appropriate dose can be administered. The Institute of Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) reports that about one-forth of medication errors that occur during a code situation originate from the dispensing and preparation process; therefore, great care and attention to detail need to be taken to ensure proper dose administration.19 Recommended mitigation strategies include using barcode scanning when possible, utilizing prospective verification of a compounded product, and including one medication strength per cart to reduce the risk of dose miscalculation.19

Literature published in 2012 surveyed three hospitals regarding their EDC medication stocking practices and found that 19 medications and concentrations were consistent amongst all three hospitals.2 While this study’s result differed from ours, they utilized a much smaller sample size. Their study, however, does indicate that relative standardization among three separate hospitals outside of a hospital system is obtainable. One review recommends a list of suggested medications for an EDC based on the review of resuscitation guidelines, with 36 medications identified to be included.5 While 23 recommended medications were stocked in at least one hospital in our study, 13 medications were not stocked in any surveyed adult/universal

EDC. Medications suggested that were not stocked include albuterol, dexamethasone, hydralazine, ipratropium, isoproterenol, labetalol, levetiracetam, oxytocin, pyridoxine, racemic epinephrine, thiamine, valproate, and vecuronium. Furthermore, of the medications suggested by Jaquet, many were only stocked by one hospital. Thus, it is evident that this broad list has not been widely implemented by North Carolina hospitals. It should be noted that none of the omitted medications are recommended for use in ACLS/BLS, and therefore not stocking them in EDCs may be reasonable if they can be quickly accessed by other methods.

EDC restocking practices were also variable throughout North Carolina hospitals; however, it was evident that pharmacy involvement was extensive at all hospitals. Furthermore, we found evidence of interdisciplinary stakeholder involvement in determining medication stocking practices. Finally, only 1% of hospitals surveyed used no locking mechanism for their EDCs. Most of these findings align with JCAHO policies for EDC medication restocking, management, and locking procedures.7

The sparsity of literature and regulations surrounding EDC stocking practices presents a true need for further research in this area. Opportunities may focus on the frequency of EDC medication use, retrieval times, and sources of errors. There is also a need for studies comparing the accessibility of other stocking and delivery methods. In particular, the role of automated dispensing cabinets in medical emergencies needs to be better explored since they were

not available when EDCs deployed during the 1960s. Once additional data is obtained, trends and best practice guidelines may be developed to better inform EDC stocking practices.

While our study represents the largest sample of EDC stocking practices published to date, the sample size is still relatively small. Not all hospitals in our sample reported their adult/universal, pediatric, and/or neonatal EDC medication contents information, further decreasing this sample size. Furthermore, our findings represent less than 10% of the 6147 hospitals in the USA, and EDC practices in other regions are likely also to increase considerably so it limits the generalizability of our findings. 20 It is important to note that the 2020 update for Basic and ACLS was published in November 2020, midway through data collection. As a result of the update and the Coronavirus 2019 pandemic, it is probable that hospitals had not yet met to update their stocking practices in accordance with this guideline update. Additionally, the department of pharmacy was always contacted, which may limit knowledge surrounding other departments’ impact on EDC stocking and monitoring procedures which were assessed in this study.

Our results identify an opportunity to further explore this topic and provide a rationale for greater EDC standardization and the need for universal policies to be developed. While full standardization among all hospitals will streamline staff use, especially if more practitioners float between hospitals, this may not be feasible. With medication shortages already a challenge for

many hospitals, requiring all facilities to use the same medications and concentrations may further burden the drug manufacturing system and lead to additional or longer shortages. Furthermore, it may not be practical for critical access hospitals to stock the same medications as a Level 1 Trauma Center as the patient population seen will vary significantly, and the likelihood of EDC use is dramatically different.

While the use of medications during medical emergencies is recommended, the lack of literature surrounding how best to stock and deliver these medications is significant.10,16,17 We know that code situations are time sensitive, but how can medication stocking affect this? We suggest future studies investigate human factors surrounding EDC stocking and use. The next steps may include examining the time for getting EDCs to the patient’s bedside and the time from medication requests to administration during a mock code situation. It would also be desirable to develop best practices around medication drawer layouts, locations for EDC placements, patient-toEDC ratios, and the utility of EDC standardization among hospital systems. Our results demonstrate the high variability of EDC contents and stocking practices across hospitals within North Carolina.

Authors: Meghan E. Peterson, PharmD, PGY-1 Pharmacy Resident Vanderbilt University Medical Center; Nashville, Tennessee. Meghan.Peterson@vumc.org. Greene Shepherd, PharmD, Professor, Division of Practice Advancement and Clinical Education, University of North Carolina Eshelman School of Pharmacy; Ashville, North Carolina.

References

1. Andersen LW, Holmberg MJ, Berg KM, et al. In-Hospital Cardiac Arrest: A Review. JAMA. 2019;321(12):1200-10.

2. Pearson AM, Caird JK, Mayer A. Crash cart drug drawer layout and design. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting. 2012;56(1):792-6.

3. Sandroni C, Nolan J, Cavallaro F, et al. In-hospital cardiac arrest: incidence, prognosis, and possible means to improve survival. Intensive Care Med. 2017;33(2):237-45.

4. Spitzer CR, Evans K, Beuhler J, et al. Code blue pit crew model: A novel approach to in-hospital cardiac arrest resuscitation. Resuscitation. 2019;143:158-64.

5. Jacquet GA, Hamade B, Diab KA, et al. The Emergency Department Crash Cart: A systematic review and suggested contents. World J Emerg Med. 2018;9(2):93-8.

6. Rousek JB, Hallenbeck MS. Improving medication management through the redesign of the hospital code cart medication drawer. Hum Facotrs. 2011;53(6):626-36.

7. Kienle PC. Meeting the standards for emergency medications and labeling. Hosp Pharm. 2006;41(9):888-94.

8. Hall MH. A resuscitation trolley for the

emergency and accident department. Injury. 1972;3(3):203-4.

9. Begg JE. A pediatric care and resuscitation cart: one community hospital’s ED experience. J Emerg Nurs. 1995;21(6):555-9.

10. Berg KM, Soar J, Andersen LW, et al. Adult advanced life support: international consensus on cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care science with treatment recommendations. 2020

11. Panchal AR, Bartos JA, Cabanas JG et al. Part 3: Adult basic and advanced life support: 2020 American Heart Association Guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation. 2020; 142(16):S366-468.

12. Topjjan AA, Raymond TT, Atkins D, et al. Part 4: Pediatric basic and advanced life support: 2020 American Heart Association Guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation. 2020; 142(16):S4469-523

13. Aziz K, Lee HC, Escobedo MB, et al. Part 5: Neonatal resuscitation: 2020 American Heart Association Guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation. 2020; 142(16):S52450.

14. Box, F. Hospitals by County: Hospitals Licensed by the State of North Carolina. Department of Health and Human Services – Division of Health Service Regulation. 2022. https://info.ncdhhs. gov/dhsr/data/hllistco.pdf

15. North Carolina Rural and Urban Counties. North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services – Office of Rural Health. 2019. https://files. nc.gov/ncdhhs/RuralUrban_2019.pdf

16. Simons FE, Ebisawa M, Sanchez-Borges M, et al. 2015 update of the evidence based: World Allergy Organization anaphylaxis guidelines. World Allergy Organiz J. 2015;8(1):32.

17. Brophy GM, Bell R, Claasen J, et al. Guidelines for the evaluation and management of status epilepticus. Neurocrit Care. 2012;17(1):3-23.

18. Salvatori R. Adrenal insufficiency. JAMA 2005;294(19):2481-8.

19. Preventing Medication Errors During Codes. Instiute for Safe Medication Practices. 2011. https://www.ismp. org/resources/preventing-medication-errors-during-codes

20. Fast Facts on U.S. Hospitals, 2021. American Hospital Association. 2021. https://www.aha.org/system/files/ media/file/2021/01/Fast-Facts-2021table-FY19-data-14jan21.pdf

Survey Questions

1. Does your hospital use a standardized emergency drug cart throughout the entire hospital?

a. If no, what types of carts do you use?

b. How many different types of layouts do you use?

2. What medications are stocked within your emergency drug cart?

3. Is the department of pharmacy responsible for emergency drug cart management at your hospital?

a. Yes

b. No

4. How many total emergency drug carts does your hospital have on the floors/units or in total?

5. How many emergency drug carts do you keep in reserve?

6. How many emergency drug carts are found within each floor/unit?

7. On average, what is the ratio between beds and emergency drug carts on each floor/unit?

8. Estimate, what is the farthest distance from a bed to an emergency drug cart.

9. When an emergency drug cart is used, how quickly is a new cart brought to the floor/unit?

10. Who performs, and what is your hospital’s process for restocking emergency drug carts?

a. If pharmacy technicians are performing the restocking, is this a dedicated job, or is this built into their normal workflow?

b. Estimate how many pharmacy FTE is dedicated to maintaining emergency drug carts.

c. Are emergency drug carts restocked on site?

11. Describe your hospital’s system for maintaining emergency drug cart content security.

12. How often are emergency drug carts checked when they are on the floor/unit?

a. Before each shift

b. Daily

c. Weekly

d. Monthly

e. Other: _______

13. Who does this?

a. Pharmacy Technician

b. Pharmacist

c. Nurse

d. Medical/Nursing Assistant

e. Other: __________

14. When medications expire within emergency drug carts, who ensures the medications are updated appropriately?

a. Pharmacy Technician

b. Pharmacist

c. Nurse d. Medical/Nursing Assistant

e. Other: _________

15. Does your hospital have a minimum expiration date for medications when restocking?

a. 3 months

b. 6 months

c. 1 year

d. Other: _________

16. How often are the types of medications that are stocked within the emergency drug cart reviewed and updated?

a. Who does this?

17. Does your hospital perform mock codes utilizing the emergency drug cart unique to your hospital?

a. Yes

b. No

18. Are carts used in training stocked the same as actual carts that are used in the hospital?

a. Yes

b. No

19. Do pharmacists routinely participate in codes at your hospital?

a. Yes

b. No

c. Unsure