A Rush of Memories

How Mister Kelly’s became a stepping stone for national talent and brought diverse performers and audiences together.

How Mister Kelly’s became a stepping stone for national talent and brought diverse performers and audiences together.

June 20 – September 28, 2024

by Alison Hinderliter

The Newberry’s latest exhibition, A Night of Mister Kelly’s, was born from a phone call received in 2018. That call led to the discovery of a treasure trove of materials that tell the story of the Newberry’s own neighborhood in the 1950s, 60s, and 70s. 10 14 18 23 28

by

Bob Dolgan

The Marienthal family played an important role in the story of Chicago in the mid-twentieth century, opening nightclubs that defined nightlife in the Windy City at a time when social movements shifted the trajectory of comedy, supper clubs gave way to theaters, and musicians found a launching pad to stardom in the Gold Coast.

by

Lili Pangborn

Early career scholars from around the globe visited the Newberry to explore our collections and benefit from the guidance of experts in the field during the inaugural First Book Workshop in Map History. The workshop points to exciting changes ahead for the study of cartography at the Newberry.

by Jessica Grzegorski

Catalogers at the Newberry have been working closely with Native communities to ensure that records related to Indigenous studies materials better align with the perspectives, cultural protocols, and knowledge systems of Indigenous people.

by Dimitrios Latsis

The Newberry’s building on Walton Street is now a well-known and well-loved landmark in Chicago. At the time it opened in 1893, however, it sat at the center of a heated debate about how library buildings should be designed.

Mister Kelly’s nightclub, located less than three blocks east of the Newberry, had state-of-the-art recording equipment installed that allowed acts to record their sets and commercially produce them as vinyl records. The album seen on the cover was recorded by Sarah Vaughan at Mister Kelly’s in 1957 and distributed via Mercury Records. Artists such as Ella Fitzgerald, Cass Elliott, Ruth Olay, Lainie Kazan, and Muddy Waters recorded sets at the club as well. In addition to musicians, records were also produced of live comedy sets by the likes of Mort Sahl, The Smothers Brothers, Freddie Prinze, and Flip Wilson.

Copies of these recordings are now housed at the Newberry as part of the Mister Kelly’s Collection. While some may see the

Editors Bob Dolgan and Vince Firpo

Designer Andrea Villasenor

Photographer Catherine Gass

inclusion of vinyl recordings in the collection as something novel, the Newberry has long collected music in its many forms. Musicrelated materials include thousands of manuscripts, imprints, instructional books, sheet music, and more. Included among these materials are handwritten scores by Mozart, Chopin, Mahler, and Wagner. In the realm of popular music, the Driscoll American Sheet Music Collection contains more than 80,000 pieces of sheet music published between the 1770s and 1959. Adding Sarah Vaughan and Anita O’Day to our archive only underscores how the collection evolves over time, much like the ways in which people create, consume, and enjoy music.

The Newberry Magazine is published semiannually. Every other issue includes the annual report for the most recently concluded fiscal year. A subscription to The Newberry Magazine is a benefit of membership in the Newberry Associates, President’s Fellows, or Next Chapter.

Unless otherwise credited, all images are from the Newberry collection or from events held at the Newberry.

To make a gift and become a member, visit newberry.org/support or call (312) 255-3581.

The Newberry is many different things to many different people... What unites all users of the Newberry is an appreciation for the humanities and the ways in which they enrich our lives.

Since December, I have had the honor of leading the Newberry Library as President and Librarian. I had long been aware of the Newberry’s outstanding collections, staff, and programming, but over the last several months, I have come to appreciate its excellence even more: nearly every day I see something remarkable from our collections and learn something new from our knowledgeable staff.

I have also come to understand that the Newberry is different things to different people—as it should be. It goes without saying that our core is our world-class collections. Some know of our strengths in maps or Renaissance materials; others view us as a repository of Chicago and American history; and to bibliophiles, we are a paradise in ways too numerous to list. In academic circles, we are celebrated as a place of scholarly excellence as evidenced through our fellowships, research centers, and K-12 teacher seminars. Genealogists travel far and wide to access our unparalleled resources and unlock their family histories. Our numerous visitors view us as a premier cultural institution, with carefully curated exhibits and expansive and engaging programs and classes. For many Chicagoans, we are a local resource housed in a beautiful, historically significant building. For those farther afield, our digital collections are a portal into history, available at their fingertips.

What unites all users of the Newberry is an appreciation for the humanities and the ways in which they enrich our lives. As President,

my goal is to foster this appreciation through the individual avenues that bring people to the Newberry and ensure the library is even better known and more widely celebrated as the premier center for the humanities in the Midwest and beyond.

Because we are a public cultural institution that is free and open to everyone, we democratize experiences and materials that were once only available to select groups. I aim to make our resources even more widely accessible so that they can be utilized by larger and more diverse audiences, in ways that meet their unique needs. I also look forward to greater collaborations with new and existing partners so that we can continue to evolve as stewards of our collections and learn more from our communities about how we can best serve them.

What does it mean for the humanities generally and the Newberry specifically to flourish in the twenty-first century? At the core of this flourishing must be friendship—friendship with the ideas, discourse, and artifacts of the humanities. One may be fortunate and stumble across the humanities and their rich reserves on one’s own, but it is more often the case that one needs the guidance of a friend or teacher to create the possibility of discovery. In many ways the Newberry strives to be this friend to all who walk through our doors. We, in turn, need friends to do our work. Thank you for your friendship and your support of the library.

Notable happenings around the Newberry. We are always growing and changing. Grounded in history, engaged with the present, looking to the future.

A new book by the Newberry’s Rose Miron takes readers into the heart of debates over who owns and has the right to tell Native American history and stories. For centuries, non-Native collectors and institutions have gathered Indigenous objects and archival materials, and Indigenous nations have had little to no control over how these materials are presented and accessed. Indigenous Archival Activism , published in April by University of Minnesota Press, tells the story of one tribe’s efforts to recover their scattered historical materials and rewrite their history. Focusing on the Stockbridge-Munsee Mohican Nation and their Historical Committee, a group composed of mostly women that has been leading this work since 1968, the book is the first monograph focusing exclusively on tribal archives.

Miron, the Director of the D’Arcy McNickle Center for American Indian and Indigenous Studies at the Newberry, wrote the book following a more than decade-long reciprocal relationship with the Stockbridge–Munsee Mohican Nation. Her research and writing are shaped primarily by materials found in the tribal archive and ongoing conversations and input from the tribe’s Historical Committee, whose members wrote the book’s foreword. Reflecting on this collaborative process, the book offers a model both for tribes undertaking their own reclamation projects and for scholars and non-Native institutions looking to work with tribes in ethical ways. Says Miron, “It was an honor to partner with the Stockbridge-Munsee Mohican Nation to tell this story. I hope the book emphasizes the importance of community engagement and shared authority with Indigenous nations, across both academia and the public humanities.”

Mohican Interventions in Public History & Memory

The National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) has awarded the Newberry a grant of $336,288 to digitize more than 2,000 rare books and manuscripts documenting languages spoken or formerly spoken by the Indigenous peoples of North and Central America.

The Edward E. Ayer North and Middle American Linguistics Collection features books, periodicals, Bibles, and dictionaries representing an estimated 300 languages. The digitization of these items, to be completed by July 2026, will improve access for scholars and contemporary Native communities, particularly those focused on language revitalization efforts.

“This exciting grant award has been years and even decades in the making,” said Astrida Orle Tantillo, President and Librarian of the Newberry Library. “It will improve access to important historical language documentation in collaboration with tribal communities and

our McNickle Center for American Indian and Indigenous Studies. The Newberry is grateful for this generous support.”

The communities whose languages are represented in the collection live across what is now the United States, Canada, Mexico, Greenland, and more than ten Central American and Caribbean countries, making a high-quality digital collection a major improvement for sustained accessibility for a geographically diverse user base. Many languages represented in the collection are endangered, with a limited number of speakers, making digitization all the more urgent. The NEH grant and digitization will make these materials broadly available online for the first time, with the Newberry’s digital portal providing easy access and facilitating collaborative research that would otherwise require significant coordination and travel costs.

A crowdsourced digital transcription project is uncovering insights about Depression-era author Jack Conroy, whose papers reside at the Newberry. Digital transcription encourages volunteers to assist the library by sifting through archives and entering information that makes materials more accessible to users. Rebecca Rector, a transcription volunteer and retired librarian based near Albany, New York, has been transcribing diaries and letters—including Conroy’s—for the Newberry for the past three years. Conroy hailed from Missouri, born in a coal mining camp to Irish immigrant parents. He became a leading figure in proletarian literature and moved to Chicago in 1937. Included in the letters is a 1983 message from the trailblazing poet Gwendolyn Brooks upon the loss of Conroy’s wife, Gladys. “I was intrigued by the variety of writers and their love and admiration for Jack,” Rebecca says. “He helped bring out their voices, and this [project] brings out the voices of some of those who wrote to him.”

Communications Coordinator Haku Blaisdell recently was promoted to Associate Director of Outreach and Strategy in the Newberry’s D’Arcy McNickle Center for American Indian and Indigenous Studies. As part of this role, Haku (Kanaka Maoli) serves as the primary point of contact between tribal nations and the library and leads outreach activities with Native communities. Haku’s responsibilities include a focus on implementation of the three-year strategic plan for Indigenous initiatives at the library, developed with community partners. Prior to joining the Newberry, Haku assisted with community engagement and research at the Field Museum and processed archival material for Northwestern’s Transportation Library.

Nora Epstein joined the Newberry as Instruction and Outreach Librarian following the completion of her PhD in History from the University of St. Andrews in 2021. As part of her role, she coordinates groups visiting the library, including hosting collection presentations for undergraduates, graduate students, and many others. In 2022, Nora was awarded fellowships from the Folger Shakespeare Library, the Bibliographical Society of America, and Yale University’s Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art. Nora served as an intern in the Newberry’s Conservation Lab in 2014.

“I am so grateful to John’s vision in charting a course for the Center for Renaissance Studies that we still use to guide our work today.”

On October 5, 2023, the Newberry lost a valued member of its community when John A. Tedeschi, former staff member and eminent scholar in the field of Renaissance and Reformation Studies and Italian History, passed away at the age of 92.

Born Guido Alfredo Tedeschi in Modena, Italy, in 1931, Tedeschi emigrated as an eight-year-old to the United States with his Jewish parents and younger brother in 1939. Landing in New York, they eventually settled in the greater Boston area, where he attended Harvard College (AB ’54, History). He also completed his graduate studies at Harvard University (PhD 1966, History and Philosophy of Religion). A hiatus in his studies came when he served in the U.S. Army as an interpreter stationed in Italy.

For most of his career, Tedeschi’s scholarship focused on Italian religious history of the sixteenth century, offering revisionist perspectives on the Italian Inquisition and heretical movements of the period. Following his retirement, his longstanding interest in histories of religious persecution became a compelling focus of his research. In 2015, he published Italian Jews Under Fascism, 1938-1945: A Personal and Historical Narrative , his sweeping personal and political account of the Jewish experience under Mussolini’s regime.

Tedeschi had a long and influential career at the Newberry. He became Bibliographer and Research Fellow in European History and Literature at the library in 1965. New opportunities at the Newberry soon followed; he became Curator of Rare Books and Manuscripts and Head of the Department of Special Collections in 1970 and the inaugural Director of the Newberry’s Center for Renaissance Studies in 1979, a position he held until he was appointed Curator of Rare Books and Special Collections at the University of Wisconsin, Madison in 1984.

Tedeschi officially retired in 1996 and in 2017 was presented with a Festschrift, or collection of writings published in honor of a scholar, by colleagues from three continents. The Festschrift serves both as a useful bibliography of his books, articles, and translations and evidence of the respect he earned among historians in his field.

Today, forty-five years after Tedeschi was its first Director, the Newberry’s Center for Renaissance Studies serves an international consortium of approximately fifty schools, connecting students and scholars with unique opportunities to learn, research, and contribute to the vibrant fields of medieval and early modern studies.

“I am so grateful to John’s vision in charting a course for the Center for Renaissance Studies that we still use to guide our work,” says Lia Markey, Director of the Center. “His rich contributions to the field will not soon be forgotten and inspire staff and students alike to this day.”

Ananda Adibhatla’s curiosity about the Newberry started with the library’s pink Connecticut granite façade and eye-catching Romanesque architecture. A recent transplant from Michigan, she moved into the Gold Coast neighborhood nearly two years ago and often passed by the nineteenth-century structure on West Walton Street.

“I live really close and walked by it,” she says, “and every single time I’d see it and say, ‘that’s a really pretty building.’”

With a life-long interest in history, she soon signed up to be a volunteer. “I just took the plunge,” she says. Ananda is now a regular volunteer for two hours at the Newberry’s greeter desk on Saturdays. Her time at the Newberry provides a social outlet away from her career in renewable energy.

“I was going to major in History back in college and vetoed it,” Ananda says. “I majored in Finance and got a corporate job, but wanted to go back to something I liked. [Volunteering at the Newberry] was a way to get back to my love of history.”

Ananda says she most enjoys the Newberry’s exhibitions and the library’s collection strength in American Indian and Indigenous Studies. As she notes, history has too often been viewed from the “eyes of the victors”—past and present.

“My favorite exhibit so far was Seeing Race Before Race,” she says of the fall 2023 exhibition. “I always warned visitors that it was a really hard-hitting one. But I’m a firm believer that we can’t ignore things just because they make us uncomfortable.”

“A lot of libraries gatekeep their resources, but the Newberry makes theirs really accessible.”

The Newberry relies on volunteers for everything from greeting guests, guiding tours, and helping at public programs. In return, volunteers enjoy discounts in the Bookshop, a subscription to The Newberry Magazine , and access to annual events.

“Volunteers are valued partners that expand the ways in which we engage the public,” says Rebecca Haynes, Manager of Volunteers at the Newberry. “The passion of people like Ananda shines through when they talk about their love of the humanities and the Newberry. We are so grateful to each and every person who donates their time to the library.”

As a greeter, Ananda is often the first person visitors encounter in the Newberry’s lobby. She says there are many interests among library visitors, everything from Lake Michigan naval maps to postcards and Moby Dick, as well as the frequently asked question: “What is this place?”

“I tell people about our really strong genealogy collection, one of the best in United States,” she says. “People get very overwhelmed on how they can trace [ancestors] back, but we have librarians who can point you in the right direction and I try to market that.”

When not at the Newberry, Ananda is working long hours managing supply chains, including the procurement of wind energy. Her time at the library provides a separate social circle of readers, staff, scholars, and other volunteers who keep her coming back.

“A lot of research libraries are promoted to a certain group of individuals, people with doctorates,” she says. “It makes it daunting for people who are not writing a thesis. A lot of libraries gatekeep their resources, but the Newberry makes theirs really accessible.”

The Newberry has acquired more than 250 maps to add to its world-renowned collection thanks to a gift from Arthur and Janet Holzheimer. The acquisition includes several extremely rare maps with an emphasis on early world cartography, the pre-1800 Americas, the American West, the Gold Rush period, and the Louisiana Gulf Coast.

The Holzheimers have been cherished members of the Newberry community for decades, assisting in the curation of exhibitions, providing funding that underwrote the production of a set of globe gores, and co-authoring articles for the Newberry’s Hermon Dunlap Smith Center for the History of Cartography. Arthur and Janet have been generous supporters of a series of fellowships in the history of cartography since 2012 and have long been members of the Newberry’s Society of Collectors.

Arthur credits Kenneth Nebenzahl Jr., a former Newberry Trustee and noted antiquarian and map dealer, with helping guide his interest in maps decades ago.

“Ken was instrumental in the early days,” Arthur said. “He told me, ‘Don’t just buy maps, look at a lot of references and see which are appealing to you.’”

The Holzheimer Collection includes some of the earliest and most important sixteenth-century printed maps depicting the Americas, such as Francesco Roselli’s Oval Planisphere (c. 1508) and two sheets from the giant eighteen-sheet 1569 map of the world by Gerard Mercator that illustrated his now famous system for a map projection that we still see today everywhere from our phones to classroom walls.

“The primary reason I am contributing the collection is so that current and future generations will be able to further their research and add to it,” Arthur said. “It’s just as meaningful giving this to the Newberry as it was to build the collection.”

“We are grateful for Art and Jan’s contribution of this incredible, globally important collection,” said David Weimer, Director of the Smith Center and Robert A. Holland Curator of Maps at the Newberry. “This collection offers incredible opportunities for people interested in anything from the environmental history of the western U.S. to early modern art. Art and Jan’s collection beautifully highlights how maps embody the intersection of so many diverse interests.”

“One of the greatest pleasures was the travel [maps] resulted in,” Arthur said, “and the friends we made because of our common interest.”

“ The primary reason I am contributing the collection is so that current and future generations will be able to further their research and add to it. It’s just as meaningful giving this to the Newberry as it was to build the collection.”

By Alison Hinderliter

In 2018, I was just stepping into my role as the newly appointed Manuscripts and Archives Curator at the Newberry Library, where I had been working as an archivist since 2001. I was contacted by a man named David Marienthal, who told me about a collection he was amassing in preparation for making a documentary film about his father and uncle’s business. He described how (uncle) Oscar and (father) George Marienthal opened nightspots in Chicago in the 1940s, 50s, and 60s, offering great food alongside top jazz and comedy entertainment. The Marienthal brothers had successfully founded and managed three major Chicago venues: London House, Mister Kelly’s, and the Happy Medium. All three venues had an astonishing roster of stars that had graced their stages, including Barbra Streisand, Ella Fitzgerald, Herbie Hancock, Ramsey Lewis, George Carlin, Dick Gregory, Lily Tomlin, the comedy duo Jerry Stiller and Anne Meara, and Bob Newhart. The most well-known of the venues, Mister Kelly’s, had been located a mere three blocks from the Newberry Library, on Rush Street, where Gibsons Bar & Steakhouse currently resides. David told me he had many photos and pieces of memorabilia at his house and invited me to come over and look.

“ The neighborhood that houses the Newberry and was home to Mister Kelly’s owns a unique place in Chicago geography and history. Whether you call it the Gold Coast, Rush Street neighborhood, or the Near North Side, it is a neighborhood of stark contrasts.”

David had been in touch with Loyola University History

Professor Emeritus Elliott Gorn and had also hired one of his students, Adam Carston, to help with researching the documentary that would become Live at Mister Kelly’s. Elliott is a longtime friend and researcher at the Newberry and recommended the library as a good repository for the archive that David was compiling. Thanks to Elliott’s connection, I visited David’s home in Chicago’s Roscoe Village neighborhood in November of 2018, where I was joined by Adam and Elliott.

One of the first pieces that caught my eye was a poster advertising Della Reese, with opening act Tim & Tom. I immediately recognized Tim Reid, having been a big fan of his character Venus Flytrap on the hit TV sitcom WKRP in Cincinnati. I exclaimed that I had no idea he’d gotten his start as a comic, and David proceeded to tell me about the groundbreaking Black and white comedy duo. Reid and Dreesen met at a Junior Chamber of Commerce Club meeting in 1968 and traveled to schools, talking to kids about the dangers of drugs. They had such a great chemistry and were so funny that one of the kids suggested that they become a comedy team. That small suggestion prompted a big change in both men’s lives, and eventually brought Reid to television stardom and Dreesen to a standup comedy career that included opening for Frank Sinatra for over thirteen years.

The story of Tim & Tom was my entry to the fascinating history of Mister Kelly’s and to Rush Street nightlife in general. It was almost inconceivable for me to think of Rush Street, now filled with luxury condominiums and designer boutiques, as a hotbed of international star talent in the mid-twentieth century.

The neighborhood that houses the Newberry and was home to Mister Kelly’s owns a unique place in Chicago geography and history. Whether you call it the Gold Coast, Rush Street neighborhood, or the Near North Side, it is a neighborhood of stark contrasts. To quote from a 1952 book entitled Vittles and Vice by Patricia Bronté, “It includes superb restaurants and cheap honky-tonks, cathedrals and book joints, The Drake hotel and disorderly flats, Northwestern University’s downtown campus and Bughouse Square, some of the world’s finest hospitals and some of the worst flop-houses, ritzy Michigan Avenue stores and drab West-Side factories. Industry, commerce, art, religion, culture, and racketeering mix here with politics. Millionaires and panhandlers are listed among its voters.”

During the Mister Kelly’s era (1953-1975), it was also an area where racial segregation was not as extreme as it was in other neighborhoods of the city. The Marienthal establishments were at the forefront of being equally welcoming spaces to communities of color and white communities. Looking through the rosters of performers in the ads, it appeared that the Marienthals and their staff often booked Black and white acts together on the same bill. David told me that there were many instances and testimonials that spoke to their history of inclusion in the club. Adam Carston relayed the story of a Black vice cop he interviewed who was in an interracial relationship in the 1960s. This gentleman felt like Mister Kelly’s and London

“ The Marienthal establishments were at the forefront of being equally welcoming spaces to communities of color and white communities...the Marienthals and their staff often booked Black and white acts together on the same bill.”

House were two of the only clubs in the city where he and his companion could go out and feel relaxed and welcome. Tim & Tom could perform there in the early 1970s and get a warm response from the audience, which was not always the case as they toured the country doing their act in other clubs.

David showed me more items—a CD recording of Ella Fitzgerald performing live at Mister Kelly’s in 1958; a poster of Bette Midler, where she autographed her outstretched leg; and a table arrayed with plates, matchbooks, brochures, and photographs. I was amazed.

David and his team interviewed close to 100 people as they prepared the award-winning 2021 documentary film Live at Mister Kelly’s. These ranged from those who attended the venues frequently, to those who worked at the three clubs, to some of the biggest stars who performed.

I assured David that the Newberry was interested in being the home for this remarkable archive, one that speaks not only to the

Newberry’s own backyard but also helps many living Chicagoans relive fond memories. The complete archive (including all ninety-six interviews) is now at the Newberry, available for viewing in our Special Collections Reading Room and serves as the basis for the exhibition A Night at Mister Kelly’s . In a poetic way, these artifacts and stories have all come back to the neighborhood in which they were created.

Alison Hinderliter is Lloyd Lewis Curator of Modern Manuscripts and Archives at the Newberry.

A Night at Mister Kelly’s is supported by the Rosaline G. Cohn Endowment for Exhibitions and the Foundation for Advancement in Conservation. The Newberry also thanks David Marienthal for his gift of the Mister Kelly’s Collection. Related programming is generously supported by the D&R Legacy Fund.

By Bob Dolgan

David Marienthal absorbed many lessons as the son of nightclub owner George Marienthal. The Marienthal family—owners of Mister Kelly’s, London House, and the Happy Medium—played an important role in shaping the nightlife that captivated Chicago residents and visitors to the Windy City. Their legacy is a uniquely Chicago story that sits at the core of the Newberry exhibition A Night at Mister Kelly’s . “I used to go down to the restaurants with him on Saturdays, and he’d put me to work cleaning up,” David says. “I got to know

the people in the kitchen and who they were. It was really like a family.”

David went on to a career that included a successful stint as a restaurateur in Chicago and the producer of an award-winning documentary about his father’s club, Live at Mister Kelly’s . The affinity that George Marienthal and brother Oscar had for staff rubbed off on David.

“I couldn’t make this stuff up when I talked to people [for the documentary],” David says. “The staff was so dedicated. And my dad and uncle treated them well.”

“The acts all liked playing there, the room was the right size,” recalled booking agent Arlyne Rothberg...“It was intimate, the food was great…worth taking the gig.”

A Night at Mister Kelly’s , the exhibition at the Newberry celebrating the famed Mister Kelly’s nightclub, tells the story of the celebrities and the venue’s place in Chicago’s nightlife history. But what of the two brothers who were the visionaries behind the scenes? That story begins with the opening of their first venue, London House, soon after World War II.

Oscar was the main booking agent for the talent in the clubs, and George managed the dining service and general operations. George learned the restaurant business while in the Air Force, when he was stationed in California and running the officers’ clubs.

“He had gotten training and background in hospitality as a coffee salesman for Continental Coffee before the war,” David says. “He called on the different restaurants in the Chicago area and had a pulse on the restaurant business.”

The Marienthals’ 1946 purchase of the Fort Dearborn Grill, at the southwest corner of Michigan Avenue and Wacker Drive, was their first foray into the restaurant and entertainment business. The grill soon became London House, a purveyor of fine steaks and later a venue for top-flight jazz in the historic London Guarantee building. Its proximity to the city’s three most prominent newspapers—the Tribune , Sun-Times , and Daily News —made it a hub for the journalists who were the influencers and tastemakers of the era.

“There was a big kitchen on the main level, and they did all their own baking on the lower level,” David recalls. “It was all fresh food. My father really had an expertise in the culinary.”

“The acts all liked playing there, the room was the right size,” recalled booking agent Arlyne Rothberg in the 2021 documentary, Live at Mister Kelly’s . “It was intimate, the food was great…worth taking the gig.”

The success of London House led to the opening of another eatery and entertainment venue, Mister Kelly’s—named after the maître d’ at the time—on Rush Street in 1953.

Mister Kelly’s combined the fine dining of London House with a state-ofthe-art sound system and acoustics that made it ideal for live recording. Sarah Vaughan, Muddy Waters, Della Reese, Anita O’Day, and Buddy Greco are among those who recorded live albums there in the years that followed. The rise of stand-up comedy became a hallmark of Mister Kelly’s with performers

like the Smothers Brothers, Lenny Bruce, Dick Gregory, Joan Rivers, Lily Tomlin, and Flip Wilson gracing the stage.

The Marienthals introduced an innovative business model that benefited up-and-coming performers and ensured that top-notch talent would be drawn to the Mister Kelly’s stage, paying $750 per week with a contract for a return engagement, a rare guarantee at the time.

“They would find lesser-known talent in New York or LA and would offer them a three-week contract with an option six months later. So Mister Kelly’s would have the option to bring them back,” David says. “Many of them had gotten so big [in the interim] that it became financially advantageous for [the Marienthals]. Ed Sullivan saw Phyllis Diller at Mister Kelly’s and put her on his show. By the time she came back to Chicago, she was much bigger.”

“ The Happy Medium was their crowning achievement... producing original comic and music revues. It was a whole new concept and such a departure from the supper club idea. It was a pretty risky decision to go into the theater business, it just shows the creativity and entrepreneurial spirit.”

Oscar Marienthal booked performers at Mister Kelly’s until his untimely death in 1963, after which his hand-picked successor, Arlyne Rothberg, continued finding the best jazz singers and musicians for the club. Singers included established stars as well as new talent. Most of the time the musicians performed two shows per night and were scheduled for two to three weeks. Live shows were often recorded and commercially produced as vinyl records.

Middlebrow humor was Pryor’s calling card when he first took the stage at Mister Kelly’s in Chicago in 1965.

“He went from being collegiate with cute sweaters and The Merv Griffin Show ,” said comedian and actor Robert Klein in the Live at Mister Kelly’s documentary. “He became not political but a more authentic Richard Pryor.”

The social movements of the 1960s—the Civil Rights Movement, the Women’s Liberation Movement, the Gay Rights Movement, the Anti-War Movement, and others—ushered in a new type of comedy in the 1970s. Underrepresented voices began to be heard. Anti-authoritarian undercurrents, subversive content, and absurdist delivery all came into the forefront as the field of standup comedy diversified and transformed. Richard Pryor, who played Mister Kelly’s many times, was emblematic of comedy’s evolution. He was not always the controversial, frequently profane comic that many remember from the late twentieth century.

Just prior to Oscar’s passing, the Marienthals partnered with renowned architect Bertrand Goldberg to open the Happy Medium comedy venue at 901 North Rush Street. The entertainment there was in the same vein as its neighbor to the north, Second City, which had opened the year prior. Sketch comedy regulars included actress Diane Ladd, married duo Jerry Stiller and Anne Meara, and Jo Anne Worley, who went on to appear on Rowan & Martin’s Laugh-In television show.

“The Happy Medium was their crowning achievement,” says David, “producing original comic and music revues. It was a whole new concept and such a departure from the supper club idea. It was a pretty risky decision to go into the theater business, it just shows the creativity and entrepreneurial spirit.”

New tastes had emerged by February 1971 when the Tribune wrote a piece, “Changes ahead for Chicago night spots.” In a memorable passage from the story, it was noted that the new maître d’ at Mister Kelly’s donned a sport coat rather than the

Newspaper column, Feb. 12, 1971, detailing changes to all three clubs based on evolving tastes in entertainment.

tuxedo worn by his predecessor. Competition from larger venues made it increasingly challenging for the smaller night spots to remain in business.

“It mirrors the changes that were happening in the nation and in Chicago,” David says. “It was a relatively short time from the midto late 1960s to the 1970s, and it seemed like everything started to change with the Vietnam War and the Civil Rights Movement.”

Mister Kelly’s soon was sold, and around the same time, in 1972, George Marienthal passed away after several bouts with cancer. The famed night spot would close its doors in 1975.

David lived his early years in the Gold Coast and attended Francis Parker High School. He went on to get a degree in Architecture and later moved to New Mexico. He then went into the restaurant business himself, as he and his brother, Phil, opened Blue Mesa at 1729 North Halsted in the Lincoln Park neighborhood in 1983. The restaurant brought the novelty of Southwestern cuisine to Chicago and enjoyed a booming business and lines out the door during a long run that concluded in 2000.

“There are several reasons to love Blue Mesa,” the Chicago Tribune ’s Phil Vettel wrote in 1993. “Intimate atmosphere is not

one of them; the nine-year-old restaurant draws big, boisterous crowds on weekends and is set up to promote conviviality in any case. But certainly the food is good, the service on the ball, and the creature comforts more than adequate, once you actually get a seat.”

David Marienthal says Blue Mesa embodied the ethos of his father—treating employees well and focusing on customer satisfaction. “My father would say, ‘You’re only as good as your last cup of coffee,’” says David. “You’re not a success unless the hot food comes out hot and the cold food comes out cold.”

A Night at Mister Kelly’s is supported by the Rosaline G. Cohn Endowment for Exhibitions and the Foundation for Advancement in Conservation. The Newberry also thanks David Marienthal for his gift of the Mister Kelly’s Collection. Related programming is generously supported by the D&R Legacy Fund.

Bob Dolgan is Director of Communications at the Newberry.

By Lili Pangborn

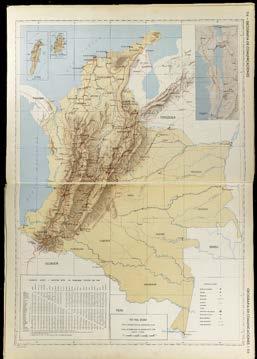

On Tuesday, February 20, three scholars new to the realm of post-doctoral map studies boarded international flights, dissertation manuscripts in tow, to meet one another for the first time at the Newberry Library: Elizabeth (Liz) Chant from Warwick, United Kingdom; Sebastian Diaz Angel from Bogotá, Colombia; and Roberto Chauca Tapia, a Peruvian living in Sydney, Australia.

Their destination was the inaugural Smith Center First Book Workshop in Map History at the Newberry. Organized by Dave Weimer, Director of the Hermon Dunlap Smith Center for the History of Cartography and Robert A. Holland Curator of Maps, in collaboration with the Center for Renaissance Studies at the Newberry, the workshop served as the pilot for a new initiative that encourages cartographic scholarship amongst a diverse field of international scholars.

Also in transit were three experts in the field whom Dave recruited to offer guidance and insight throughout the workshop: Matthew Edney, Professor in the History of Cartography at the University of Southern Maine and Director of the History of Cartography Project at the University of Wisconsin-Madison; Jordana Dym, Professor of History at Skidmore College; and Ernesto Capello, Professor of History and Latin American Studies at Macalester College.

Awaiting them all was the Newberry’s renowned collection— thousands of primary and secondary source materials spanning more than 600 years of history—along with curators, librarians, and long-time scholars with expert knowledge, who were ready to guide the three rising authors through the Newberry collection and the workshop process.

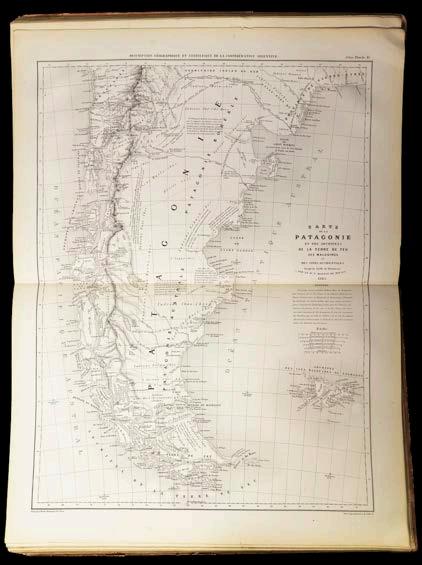

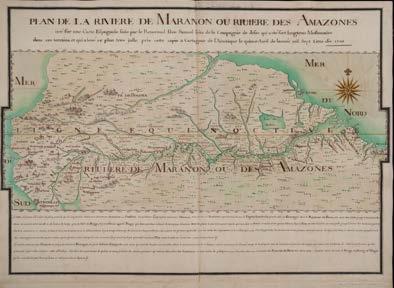

Despite their varying approaches, all three scholars’ working manuscripts look at the impact of external or colonial influence on geography and mapping in South America. Liz examines cultural representations of Patagonia (present-day Argentina and Chile) in maps and travel ephemera to explore how the trope of Patagonian desolation was both perpetuated and dismissed through acts of colonization; Sebastian studies incomplete Cold War-era development projects in the so-called “South American Great Lakes System,” an attempt to recreate the Great Lakes of North America in the southern continent; and Roberto is interested in how the changing cartographic and geographic definitions of the Amazon River functioned as tools for Europeans to explain and assert dominion over the surrounding area during the Early Modern period.

The workshop began with a presentation of items from the Newberry’s map collection. The visiting scholars viewed rare and historic maps—including a 1508 Roselli world map and a staggeringly large 1775 map of South America from the archive of Venetian map collector Franco Novacco—as well as certain travel ephemera relevant to the Amazon and Patagonia regions.

An 1865 Martin de Moussy map, “Carte de la Patagonie et des archipels de la Terre de Feu,” from the first atlas depicting Argentina titled Description géographique et statistique de la confédération Argentine , was of particular importance to Liz, upon which her manuscript ‘Land of the Future’: Patagonia between Desolation and Grandeur relies heavily. At the Newberry, Liz could see in-person for the first time the map she had spent hours studying digitally.

“ In my head the atlas was actually smaller. It really makes a big difference to be able to interact with the objects, because the sense of scale is really difficult to grasp when working with digital reproductions...Seeing things as they would have been seen at the time of their production really changes your perception.”

“In my head the atlas was actually smaller,” she remarked. “It really makes a big difference to be able to interact with the objects, because the sense of scale is really difficult to grasp when working with digital reproductions. It helps with the interpretation of some of these pieces. Seeing things as they would have been seen at the time of their production really changes your perception.”

Sebastian had a similar experience viewing the Atlas de Colombia, a 1969 atlas produced by the Instituto Geográfico Agustín Codazzi. Although a common road atlas, in the context of Sebastian’s manuscript, Weaponizing Geography: An Environmental and Technological History of Cold War Mega-Projects in Latin America , this map serves as a valuable tool for interpreting the Cold War-era confidence in the capacity of human beings to control and manipulate geography for national development and security. In his manuscript, Sebastian positions this map alongside others from the late-twentieth century to illuminate intersecting histories of technology, environment, and geopolitics.

After spending time with the Newberry’s map collection, Roberto, Liz, and Sebastian participated in a series of workshops focused on specific portions of their books-in-progress. Jordana, Matthew, Ernesto—long-time members of the Newberry scholarly community—joined Dave to provide guidance on the writing process, tailored to the needs of each writer. They asked probing, multifaceted questions. How do you define periodization and chronology in the scope of these projects? How do you decide which source materials are most pertinent to the story you are trying to tell? How do you maintain a cohesive project while navigating different audiences who are seeking different meanings out of your work?

Though these questions were not easily answered, they generated thoughtful and important discussion about how to improve each manuscript. Matthew succinctly described the writing process for a project of this scale. “It becomes a

“ Having the possibility of sharing my work with a group of experts on the field of map history was probably the most important aspect when I decided to submit my application...The writing advice that I received has been very useful. But I think that getting to know the other participants, readers, and the library director was also a very important aspect of the workshop.”

negotiation” among author, source material, and audience. The role of a writing mentor, then, becomes that of a mediator: to help already talented researchers and writers navigate these sometimes-conflicting forces.

On the final day of the workshop, during a session Dave coordinated with Susannah Engstrom, Assistant Editor for geography and cartography at the University of Chicago Press, the visiting scholars reflected on the linguistic hurdles they have encountered throughout the research, writing, and publishing process. For instance, as native Spanish speakers, Sebastian and Roberto have had to confront their subject matter in both Spanish and English, decide in which language they hope to publish, and consider what may be lost through the translation process. “[I] have the feeling when translating from Spanish to English [that] there is always something missing,” Roberto said, “something that can’t quite be communicated the same.” Jordana concurred. “It’s not just about language. Spanish provides a whole different way of communicating an argument than English.”

After two full days of examining collection items, reading, editing, writing, and rewriting, the workshop ended on a note of optimistic anticipation. “I hope this will be a stepping stone in your relationship with the Newberry,” said Dave.

The idea for the workshop came to Dave as he considered the future of the Smith Center and the Newberry’s map collection. Dave was appointed Curator of Maps and Director of the research center in 2022 and seeks to blend his roles so that the Smith Center’s activities—research seminars, lectures, and public programming—are supported by and help inform the ongoing expansion of the library’s map collections.

When considering his dual roles at the Newberry, Dave takes an interdisciplinary approach. “I am not a geographer and instead got interested in maps from the perspective of material and visual culture,” he says. “I first focus on the visual choices and physical life of maps before I end up paying attention to the map’s actual geography. If you put a map in front of me, I might end up wondering about its color palette or the design of its lines before I even realize what city it represents.”

The Smith Center has long sponsored a range of programs, seminars, and lectures to inspire learning in the history of mapping. Notably, the Nebenzahl Lectures in the History of Cartography— founded in 1966 by Kenneth Nebenzahl Jr., author of numerous publications on maps and cartography and former member of the Newberry Board of Trustees—take place every three years and are dedicated to research in the study of the science, art, and culture of map making. The Newberry also has received generous funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) to host scholars for NEH Summer Seminars and Summer Institutes for over forty years. Although such programs align with Dave’s long-term goals for the Smith Center to encourage community building and scholarly research, funding from federal agencies like the NEH is limited to United States citizens and residents. Dave hopes to expand the Smith Center’s reach to scholars from around the globe, as evidenced by the Smith Center First Book Workshop in Map History.

Dave decided to focus on helping emerging scholars break into the field because of the relative lack of support from academia for people in the field. “Map history,” Dave explained, “is an area of study that does not have the same institutional support as many other fields since it often sits between traditional departments.” The Smith Center can therefore play a vital role in fostering map scholarship around the world. And so, the idea for the workshop was born.

Given the needs of emerging scholars, Dave felt it imperative that community building be central to the event. Accordingly, he sought out scholars focused on interdisciplinary projects with overlapping themes. Collaborating with Lia Markey and Chris Fletcher, Director and Assistant Director, respectively, of the Newberry’s Center for Renaissance Studies, provided a unique opportunity to recruit scholars focused on Early Modern mapping, as well as more contemporary foci.

The response to Dave’s workshop request was overwhelming— and telling of a larger trend. As applications arrived from all corners of the world, from Great Britain to Japan, Canada to Australia, Colombia to India, Dave saw the full potential of reaching out to international scholars.

Applicants found a crucial opportunity to further their projects with renowned scholars. “Having the possibility of sharing my work with a group of experts in the field of map history was probably the most important aspect when I decided to submit my application,” Roberto reflected after completing the workshop. “The writing advice that I received has been very useful. But I think that getting to know the other participants, readers, and library staff was also a very important aspect of the workshop.”

Dave is pleased with the inaugural workshop and sees great potential for the future. “Just being in the room with likeminded

scholars can be a very generative experience,” he said. “I hope we can continue to foster scholarship and community around the study of maps.”

Laura McEnaney, Vice President for Research and Education at the Newberry echoed this sentiment. “There’s a way in which we have come to think about the Newberry as a space for finished work. But we want to begin to think about the Newberry as a rehearsal space, a space for pitches, for trying things out. A space for unabashed commitment to unfinished work. This workshop, to me, is a beautiful expression of that belief.”

Lili Pangborn is Communications Coordinator at the Newberry.

“There’s a way in which we have come to think about the Newberry as a space for finished work. But we want to begin to think about the Newberry as a rehearsal space, a space for pitches, for trying things out. A space for unabashed commitment to unfinished work. This workshop, to me, is a beautiful expression of that belief.”

By Jessica Grzegorski

The Newberry has existed for nearly as long as the practice of modern library cataloging in the United States. Melvil Dewey published the Dewey Decimal Classification in 1876, just eleven years before the Newberry opened in 1887. Since then, catalogers and archivists at the library have witnessed the evolution of standards for description and implemented these new best practices to make the library’s collections ever more accessible to readers. The tools of the trade have also advanced and diversified: from printed cards in wooden drawers (which can still be seen on the third floor of the Newberry) to online catalogs and digital asset management systems, which make digital images of collection items available worldwide.

The Newberry’s collection has also evolved and grown in the past 137 years. In 1911, collector and Newberry Trustee Edward E. Ayer donated more than 17,000 items related to Indigenous peoples. The Ayer Collection is one of the largest collections of books and manuscripts about Indigenous peoples of the Americas in the world, one that continues to grow to this day. Most of the materials in the collection are written from the viewpoint of white settlers rather than that of the Indigenous peoples they document. More recently, however, the Newberry has been expanding the collection with materials created by Native writers, artists, and activists in order to better represent a diversity of Indigenous perspectives across the Western Hemisphere and around the world.

In 2020, the Newberry received a planning grant from the Mellon Foundation to improve access to the library’s Indigenous studies collection. As part of the project, staff are working in collaboration with several tribal and community partners to learn more about their needs and priorities. This project is designed to help us move further in aligning our policies and practices with Native perspectives, cultural protocols, and knowledge systems. It also allows us to be a more welcoming and accessible destination for Native users of the collection.

“The Newberry prides itself on being free and open to the public,” explains Rose Miron, Director of the Newberry’s D’Arcy McNickle Center for American Indian and Indigenous Studies.

“ We aim to provide access to our collection to all who wish to use the library, but because of the ways in which items related to Native communities have been collected, organized, and described in library catalogs over time, it can be difficult for Indigenous users to access these materials.”

“We aim to provide access to our collection to all who wish to use the library, but because of the ways in which items related to Native communities have been collected, organized, and described in library catalogs over time, it can be difficult for Indigenous users to access these materials.”

The most widely used standards for describing and classifying library materials in North American academic and research libraries, such as the Library of Congress Subject Headings (LCSH) and Library of Congress Classification (LCC) system, were created over a century ago and are informed by a worldview that is predominantly white and Christian. LCSH is a wide-ranging and comprehensive thesaurus of subject headings maintained by the Library of Congress. The depth, breadth, and massive scale of LCSH means that revisions to the vocabulary move slowly. Many of the terms in LCSH for Indigenous peoples were established decades ago and are now outdated; others are inaccurate or offensive. The terms have been formulated mostly by non-Native information professionals and subject specialists, who very often base their decisions on scholarship that is generated outside of Native communities.

Traditional Indigenous knowledge does not always fit neatly within the hierarchical structure of LCSH and LCC, and the language used in library catalogs and databases to describe this knowledge makes it challenging for Native people to find materials that are relevant to them. Moreover, non-Native scholars have often recorded sacred or religious content without the permission of tribal communities. Many of these materials are held in libraries and archives without an awareness of tribal protocols for handling such culturally sensitive materials.

The wider community of academic and research libraries has acted in recent years to address the harm caused by past cataloging practices. Inclusive cataloging (also known as reparative description) is a framework for addressing bias and harmful language in the descriptions of library materials. The Newberry has joined many other libraries in implementing inclusive cataloging practices. The Library of Congress, for example, is undertaking a major initiative to evaluate and change incorrect or offensive LCSH terms for Indigenous peoples. Other libraries, such as the Xwi7xwa Library at the University of British Columbia, have developed their own systems for organizing materials containing Indigenous knowledge to better serve Native users.

Modern cataloging practices grew from the days of the library card catalog, when there was limited space on physical cards to record information. These limitations influenced how many subject headings a cataloger could include in a description. As cataloging tools and standards evolved and moved online, storage capacity for descriptions of library and archival collections expanded exponentially. Providing more detailed information in catalog records and finding aids for Indigenous materials is now both an achievable goal and a vital component of the inclusive description strategy at the Newberry.

At the same time, national and international guidelines for cataloging collections and making them accessible have helped standardize the ways in which catalogers and archivists describe them. For example, LCSH is the most widely used subject vocabulary in the world. Researchers can search for the same LCSH terms in the databases of multiple libraries and expect to retrieve similar types of materials. Clearly, LCSH enhances access to library materials, but its outdated and inaccurate terms for Indigenous peoples can also hinder access. At the Newberry, staff are taking a combined approach of adding more LCSH terms to catalog records to cover a wider range of Indigenous

topics while also adding keywords and descriptive notes when the LCSH terms are inadequate.

The catalog record for a seventeenth-century manuscript account written by Antoine Laumet de Lamothe Cadillac (Ayer MS 130) provides a good example of this work. The manuscript describes the French settlement at Michilimackinac in present-day northern Michigan and the cultures and traditional lifeways of neighboring Native tribes. Previously, the subject headings included only broad terms for Indigenous peoples of the Great Lakes region, such that, for example, a Potawatomi person searching for materials related to their

“ It is important to note that efforts to revise offensive language are not akin to erasing the past. Facilitating access to as much of the historical record as possible, including dark and painful episodes of history, is core to the mission of the Newberry and critical to understanding our present.”

The catalog record for a 1656 manuscript originally contained a derogatory term for a Native woman, which was quoted directly from the manuscript. Cataloging staff replaced it with the more appropriate and respectful term seen here.

Special notes in the online catalog alert users to the presence of offensive language transcribed from collection materials and provide context for why the language remains in catalog records.

Example of a Traditional Knowledge (TK) Label in the online catalog alerting users that the content of a collection item is culturally sensitive.

ancestors using the keyword “Potawatomi” would not have surfaced this item. The only mention of Potawatomi people in the catalog record was a transcription of a rare French spelling for this community, “Pouteouatami.” The record now includes additional LCSH terms for eight individual tribal groups. Although the manuscript may not contain a large amount of information about each individual tribe, surfacing the names of each group makes it possible for Indigenous researchers to find documents that pertain to their own histories and communities using keyword searches.

In other cases, the Newberry is enhancing the searchability of materials by adding descriptive notes. For example, LCSH terms for Indigenous languages may not cover every language or its dialects. Often the LCSH term does not reflect how Native speakers refer to their own language. Newberry catalog records can now provide detailed information about the dialect in which an Indigenous-language publication is written, or include the name for a language as it is known within its community of speakers along with the LCSH term.

“This project is not merely about enhancing searchability,” says Miron. “We are also aware of the harm that outdated or offensive records can cause for Native users of the collection

and how this can impede their access to the library. Indigenous studies materials at the Newberry span many centuries, documenting the first contact between Indigenous peoples and Europeans up to the cultural and artistic contributions of Native people living today. Many of the historical documents created by white settlers use offensive language in reference to the Indigenous peoples. It’s our duty to work to correct this when possible.”

Through the lens of inclusive description, catalogers and archivists at the Newberry are acting to mitigate the harm that such language causes to Indigenous users. It is not always possible to remove racial slurs or other offensive language from catalog records and finding aids. For example, this language may be part of the title of a published work; removing or replacing a portion of the title would make it impossible for users to locate that work through a title search. But terms in “free text” portions of a description, such as a summary compiled by a cataloger, can be modified without affecting searchability. For example, a derogatory term for an Indigenous woman appears in a 1656 deposition regarding property in Massachusetts promised to a white settler from a Native female leader (Ayer MS 194). Originally, the cataloger had transcribed the term

“The work done by our catalogers is already making a tremendous impact on how Native users of the Newberry interact with our collection. Indigenous people are an integral part of the Newberry community, and we are committed to removing barriers to accessing collection materials that tell their stories.”

as it appeared. However, staff recently revised the phrase to a more appropriate and respectful term without affecting researchers’ ability to find and consult the item.

“It is important to note that efforts to revise offensive language are not akin to erasing the past,” explains Will Hansen, Roger and Julie Baskes Vice President for Collection and Library Services. “Facilitating access to as much of the historical record as possible, including dark and painful episodes of history, is core to the mission of the Newberry and critical to understanding our present. In cases when we must record offensive language in catalog records and finding aids, our catalogers and archivists include a note acknowledging the presence of the language and the historical and cultural contexts in which the collection materials were created.”

The Indigenous studies collection at the Newberry includes culturally sensitive materials, which merit special consideration and handling. The Protocols for Native American Archival Materials defines these as “tangible or intangible property and knowledge that pertains to the distinct values, beliefs, and ways of living for a culture.” What is culturally sensitive to one community may not be sensitive to another, but common examples include depictions of tribal spiritual or religious places (a Midéwiwin lodge) or beliefs (Cherokee sacred formulae). Some materials are culturally sensitive at certain times of the year; others have gendered protocols. Some are never meant to be shared outside of the community of origin.

During the Mellon-funded project, the Newberry revised its policies on access to culturally sensitive Indigenous materials. As part of this, the Newberry began using Traditional Knowledge (TK) Labels in the online catalog and other collection databases. TK Labels are sets of graphics and text assigned by communities and identify community-specific guidelines regarding access and use of traditional knowledge.

The Newberry consults with Tribal Historic Preservation Officers (THPOs) and other community leaders, who determine if labels should be assigned. Just because a TK Label is applied to a collection item does not mean that access is restricted. The labels serve an educational and informational function that centers respect for Indigenous protocols. In some cases, access is restricted if tribal officers determine that collection materials should never have been shared outside of the community in which they were created. Although restricting access to knowledge may seem counter to the mission of libraries, we must acknowledge how these materials came into the library’s collection in the first place—

non-Native researchers removed Indigenous knowledge from the contexts in which it belongs and published information without the permission of Native communities. Following protocols on the handling and use of culturally sensitive Indigenous materials is an important step toward balancing equal access to collection materials with respect for the rights of sovereign tribal nations and Indigenous communities.

Inclusive description practices are one way in which we can surface and center the rich array of Native experiences documented in our collection. Standards for cataloging and archival description continue to evolve, and library databases are dynamic. Like any living and growing collection, library catalogs require care, maintenance, and continual reassessment. The primary purpose of library databases is to provide the means for users to connect with resources that are meaningful to them.

“The work done by our catalogers is already making a tremendous impact on how Native users of the Newberry interact with our collection,” says Miron. “Indigenous people are an integral part of the Newberry community, and we are committed to removing barriers to accessing collection materials that tell their stories.”

Jessica Grzegorski is Head of Cataloging for Collections Services at the Newberry.

By Dimitrios Latsis

The period between the two World’s Fairs hosted in Chicago (the World’s Columbian Exposition in 1893 and A Century of Progress International Exposition, held from 1933 to 1934) represents the heart of the Progressive Era. These early interwar years saw the rapid professionalization of librarianship, the founding of important and lasting cultural institutions, and the erection of purpose-built library facilities at a rate without precedent in any other era. Since Chicago was at the core of a booming United States economy and had already developed

into an industrial and transportation powerhouse, it might have been expected that its civic leaders would seek to translate this monetary might into a modicum of cultural sophistication. Indeed, the 1890s saw the foundation of several universities (e.g., The University of Chicago, Armour Institute of Technology), museums (e.g., The Field Museum of Natural History), and the completion of a massive building for the city’s public library. This emerging knowledge infrastructure attracted attention and set precedents in many areas, including library and information science as well as humanistic and social science research.

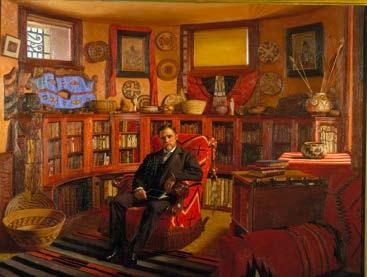

My own research into the evolution of research library architecture and the systems used for physically and conceptually classifying human knowledge within them has led me to see them as living organisms, highly responsive to their cultural milieu with a not-infrequent appetite for risk-taking and innovation. During my time as a Society of Mayflower Descendants in the State of Illinois short-term research fellow at the Newberry in 2023, I had the opportunity to thoroughly review the library’s institutional archive as well as related collections of manuscripts and rare books donated by early members of the staff and the Board of Trustees.

While the Newberry has in the past produced publications, exhibitions, and lectures to highlight its own history (especially during anniversary years), it is still easy to overlook just how unique the library was during the time of its foundation and what a broad and enduring impact it has had on its peers and the fields of study in which its librarians, curators, and administrators have been active.

The Newberry was the first purpose-built research library where a librarian had significant input. It is also true that the architecture and interior arrangement incorporated research into most European and American precedents. Erecting a landmark building as the new library’s home was a goal for the founding Trustees since their first meeting at Eliphalet Blatchford’s residence in early 1887. Blatchford, the executor of Walter Loomis Newberry’s estate and one of the library’s first Trustees, had one of the largest private book collections in Chicago and over the years compiled a substantial archive of

photographs and press clippings related to library architecture in the U.S. and Europe, which survive in the form of multiple albums. He would be at one end of a struggle of wills and tastes that ultimately determined the Newberry’s architecture. At the other end was Chicago’s first city librarian, William Frederick Poole, who throughout the 1870s and 80s had lectured and published widely on his novel and controversial ideas about the same topic dear to Blatchford.

During the six years between 1887 and 1893, when the Newberry’s burgeoning collection was housed in two temporary structures, the Trustees engaged a young but rising architect, Henry Ives Cobb, reasoning that they would easily be able to impose their ideas on him. Cobb and Blatchford went on a tour of libraries on the East Coast and then proceeded to Europe, visiting major buildings including the new National Library in

Dublin and a slew of older institutions in Spain, France, and Germany. Meanwhile in Chicago, Poole had been appointed as Director of the Newberry and published anonymous accounts in the press bemoaning the tentative plans for the building, going so far as to engage a rival architect to draft floor plans reflecting his own vision for a modular, expandable four-story building structured around thematic reading rooms where readers could readily access the entire collection.

This acrimony came to a head in the summer and fall of 1889, but it was Poole who ultimately got his way. When the palatial edifice on Walton Street opened after the close of the 1893 World’s Fair, he had not only grown the collection to over one hundred thousand volumes, but he had also given Chicago a forward-looking research incubator housed in one of the city’s great Romanesque Revival buildings. The Newberry building incorporated individual subject reading rooms where researchers would have all the materials needed to complete their work close at hand and which were overseen by reference librarians that were scholars of the corresponding topics.

At the same time the Newberry opened its doors, several great libraries in the United States were approaching or had surpassed the million-volume mark and were thus refining

their buildings to accommodate their holdings. The Library of Congress was constructed with a cruciform system of closed stacks at its heart. In 1876, the Harvard library added a specially designed stack building that could only be accessed by the librarians. Poole’s insistence on the absence of closed stacks and the ready accessibility of the collection by readers may have thus appeared outdated and impractical to some.

It is worth noting that the stack model that Poole fought against ultimately did predominate in the long-term. Indeed, one can see the addition of a ten-story stack building in 1982 on the back of the Newberry’s historic building as the final defeat of Poole’s vision of a fully accessible collection. But the recent emergence of public library buildings in Toronto (1977), Chicago (1991), San Francisco (1996), and Seattle (2004), among many others, which returned to the subject-room plan, might indicate that Poole and his partisans might yet get the last laugh.

Poole’s design for the reading rooms was not the only notable feature of the Newberry’s new home. Only a few months after opening to the public, the library inaugurated its first major public outreach activity. Libraries were increasingly being viewed as the universities of the people, and educational

programming has been a part of the Newberry’s remit from the beginning. Poole saw an opportunity in partnering with the newly established University of Chicago to inaugurate a series of public lectures accessible to the public by subscription in the library’s auditorium, which had been expressly planned on the ground floor of the building with such a use in mind. Such a space exists today and is often filled with attendees at free Newberry programs. Similarly, the Newberry’s long history of exhibiting collection items is reflected in its design. The Cobb building served as a sort of library-museum combination with an exhibition space on the ground floor and reading rooms for researchers on the upper floors, which remain essentially unchanged today. Already in 1896, the Chicago Daily Tribune celebrated the opening of the Newberry’s “Book Museum,” which showcased fine bindings, samples of Gutenberg’s work, and the smallest book in the collection measuring three by five inches.

In Poole, the Trustees of the Newberry selected one of the leading lights of the developing field of librarianship as their first Director. As William Stetson Merrill observed in his memoirs, with Poole’s death, the American tradition of running the library on “practical and inexpensive lines” came to an end and the establishment of a more technical, managerial profession began. What remains undeniable is that the building, collections, and philosophy of the Newberry, an institution he helped found 137 years ago, are indelibly marked by his vision and idiosyncrasies today.

Dimitrios Latsis is Assistant Professor of Digital and Audiovisual Preservation, School of Library and Information Studies at the University of Alabama.

The Newberry honored Drew Gilpin Faust for her contributions to the humanities during the library’s annual Award Celebration on April 19. Faust is the Arthur Kingsley Porter University Research Professor at Harvard University, where she also served as president from 2007 to 2018. She previously served as founding dean of the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study and is the author of seven books, including most recently, Necessary Trouble: Growing Up at Midcentury, published in August 2023.

Several hundred guests gathered to hear Faust and Newberry President Astrida Orle Tantillo in a far-ranging conversation covering topics as diverse as Faust’s personal involvement in the mid-century Civil Rights Movement and the critical role archives like the Newberry’s have played in her research and her academic career. “It was an enormous pleasure to honor Drew Gilpin Faust with the Newberry Library Award,” said Tantillo. “Our conversation was a reminder of the important role the humanities play in telling stories, whether a personal coming of age tale or the larger stories of a society and a nation. Drew’s writing does both, in a powerful way, and we were delighted to have the chance to welcome her to the Newberry.”

The Newberry Library Award is presented annually to recognize achievement in the humanities in the tradition of the Newberry, which has fostered a deeper understanding of our world by inspiring research and learning in the humanities since its founding in 1887. Past recipients include Ken Burns; Ira Glass and This American Life; and Lonnie G. Bunch III, Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. All proceeds from the event support the Newberry’s collection and programs.

The Newberry hosted a string of popular public programs throughout the winter and spring that drew nearly 3,000 people to the library and attracted thousands more via livestream.

We kicked off our 2024 programming in February with an interactive Valentinethemed maker event where attendees tried their hand at calligraphy with partners from the Chicago Calligraphy Collective. A program presented in collaboration with the Clarence Darrow Commemorative Committee reflected on the centenary of the murder of 14-year-old Bobby Franks by Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb by recreating the prosecution, defense, and sentencing through the lens of twenty-first-century ideas about juvenile criminal justice. We hosted two installments of the popular “Writers on Writing” series with our partners at StoryStudio Chicago. In March, award-winning authors Hanif Abdurraqib and Eve L. Ewing filled Ruggles Hall; in May, we welcomed Pulitzer Prize-winning poet Jericho Brown and Robyn Schiff, whose Information Desk: An Epic was named a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in poetry this year. Renowned designer, educator, and author David Shields presented his research on the Rob Roy Kelly Wood Type Collection as part of the Wing Foundation Lecture Series on the History of the Book.

“Writers on Writing” is generously supported by Shanti Nagarkatti. Programming for A Night at Mister Kelly’s is generously supported by the D&R Legacy Fund. “Conversations at the Newberry” is supported by Sue and Melvin Gray.

We participated in the American Writers Festival, presented by the American Writers Museum and Chicago Public Library, with a talk by Rose Miron, Director of the Newberry’s D’Arcy McNickle Center for American Indian and Indigenous Studies, on her new book Indigenous Archival Activism

Attendees also enjoyed a host of programs related to our popular exhibition A Night at Mister Kelly’s that celebrated the famed nightclub and its performers. We were thrilled to welcome comedians Tim Reid and Tom Dreesen back to Chicago to discuss their long and storied careers as part of our “Conversations at the Newberry” series. We hosted revelers at a special reception at Gibsons Bar & Steakhouse, the former home of Mister Kelly’s. And we screened the documentary Live from Mister Kelly’s throughout the run of the exhibition, allowing people to relive (or experience for the first time) the magic of Mister Kelly’s.

“It’s wonderful to see new and familiar faces fill our event spaces each week to explore a variety of interesting topics, meet their favorite author, and delight in all the Newberry has to offer,” notes Vince Firpo, Vice President for Public Engagement.

Public programs at the Newberry are always free and open to all. Most programs are livestreamed, making it easier than ever to attend a Newberry program from around the country or across the globe. Recordings of our livestreamed programs are available on YouTube at youtube.com/user/thenewberrylibrary.

View a list of all upcoming programs, classes, tours, and much more at newberry.org/calendar.