American Journeys

SPRING/SUMMER 2022 NO. 18

Travel, tourism, migration, and forced migration have been intertwined in the United States for centuries.

Handmaidens for Travelers The Pullman Company Maids Exhibition now open at the Newberry

Peacetorn: Chicago After World War II by Laura McEnaney

After VJ Day, a new phase of World War II began: peacetime at home. In the neighborhood surrounding the Newberry, Chicagoans battled for their own slice of prosperity in an emerging postwar world.

Crossings: Mapping American Journeys by

Jim Akerman

In the Newberry’s galleries, an exhibition of maps, guidebooks, travelogues, and postcards recreates travelers’ experiences along four historic routes across the United States.

Working on the Railroad

Miriam Thaggert, the author of Riding Jane Crow and the curator of a new exhibition at the Newberry, discusses her research on the African American women who worked as maids on Pullman Company sleeping cars.

The Hunt for Restrictive Covenants in Cook County

by LaDale Winling

The legacy of racist real estate practices continues to haunt Chicago and Cook County. A collaboration between the Newberry, WBEZ, and historian LaDale Winling is uncovering the history of restrictive covenants in the county.

2 Behind the Cover 3 President’s Column 4 Take Note 30 The Recent Past FEATURES DEPARTMENTS

7 12 21 26

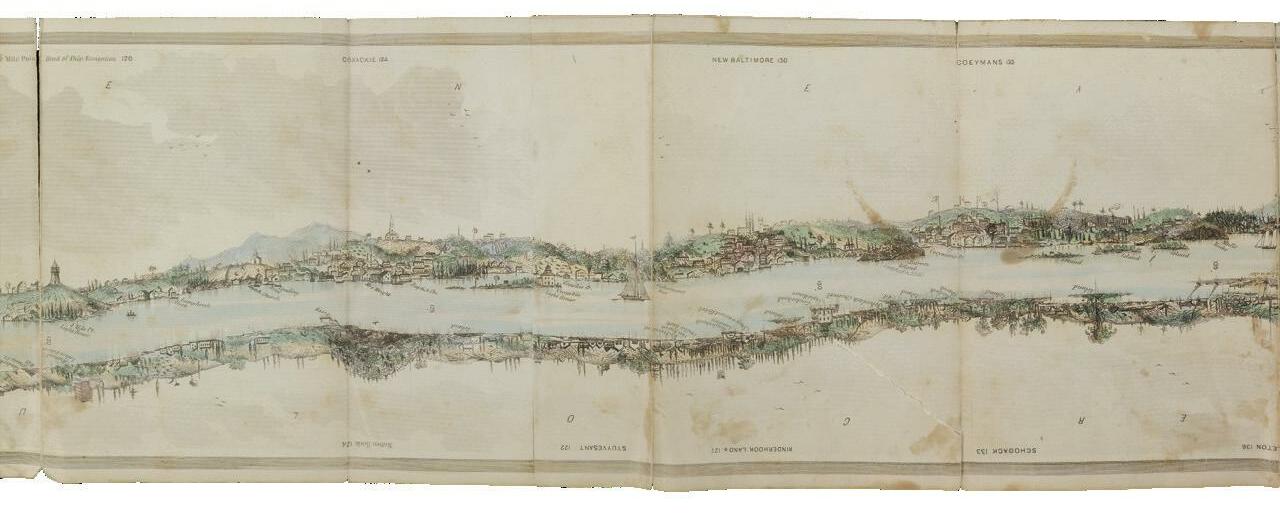

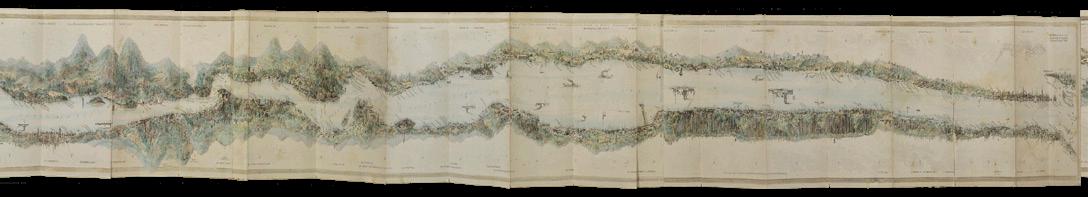

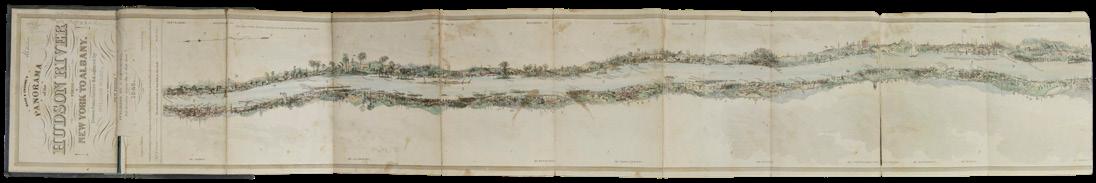

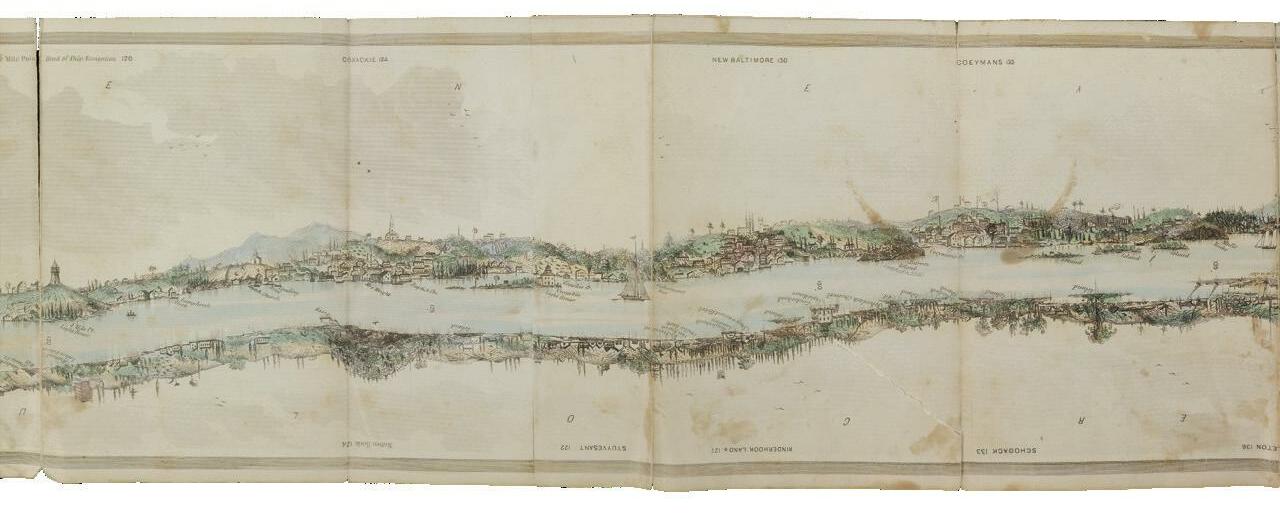

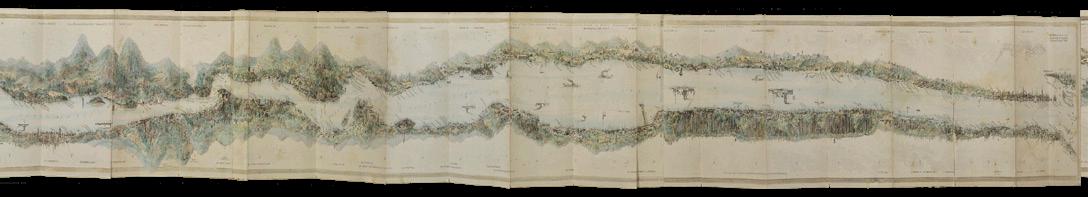

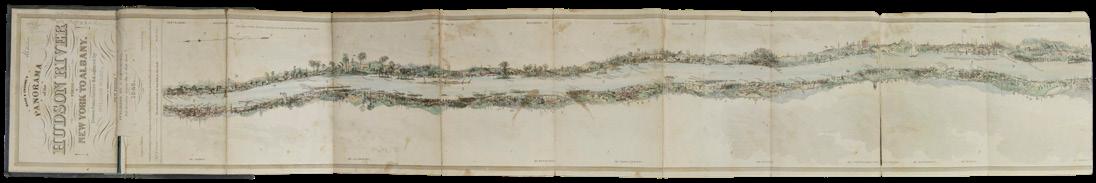

The 150-mile course of the Hudson River , from New York Harbor to north of Albany, served as an important route for travel, trade, and migration throughout the nineteenth century. More than 12 feet in length, this accordion-style map of the Hudson was published in 1846 by John Disturnell, one of the leading publishers of maps and guidebooks at the time.

In an era of steamboat travel, maps like this were popular with tourists. Floating along the Hudson, a traveler would unfurl

the map to identify sites of interest along the way, such as the mansions of New York’s elite, looming over the water from atop the riverside bluffs.

Disturnell’s map of the Hudson River is part of the Newberry exhibition Crossings: Mapping American Travel . The exhibition is on view at the library through June 25, 2022.

MAGAZINE STAFF

To make a donation to the Newberry, call (312) 255-3581 or email contributions@newberry.org.

The Newberry Magazine is published semiannually. Every other issue includes the annual report for the most recently concluded fiscal year. A subscription to The Newberry Magazine is a benefit of supporting the Annual Fund.

Unless otherwise credited, all images are from the Newberry collection or from events held at the Newberry.

Editor Alex Teller

Designer Andrea Villasenor

Photography Catherine Gass

BEHIND THE COVER

2 The Newberry Magazine | Spring / Summer 2022

Disturnell’s map of the Hudson River in its entirety.

As I write this column, we’re nearing the launch of a new strategic plan to guide the Newberry through the next five years. The plan identifies belonging as one of our five core values, along with curiosity, knowledge, service, and relevance. For us, belonging means more than being comfortable or content in a group of people. It means creating spaces for learning that actively invite multiple perspectives, asking whose stories are told, and by whom. Expanding the sense of belonging at the Newberry means attracting new participants onsite and online, intentionally connecting people, and building relationships. Bringing library users together in a place—within the library walls—makes our interactions so much richer. We feel a more profound sense of belonging when we are together.

This issue of The Newberry Magazine includes four features— two by staff members and two by former research fellows—that ask important questions about place and belonging.

Vice President for Research and Academic Programs Laura McEnaney invites us to revisit post–World War II Chicago, focusing on conflicts between tenants and property owners in the Newberry’s immediate neighborhood. Jim Akerman, Curator of Maps and Director of the Hermon Dunlap Smith Center for the History of Cartography, zooms out to take a national view,

exploring the many routes taken by Americans over time to cross the continental United States. His focus on American travel mapping—drawing from the Newberry’s remarkable collection in this subject—also helps us see the absences of certain travelers and migrants, especially Indigenous people and the enslaved, from these maps. An interview with Newberry fellow Miriam Thaggert surfaces forgotten voices from the Newberry’s Pullman Company Records: the Pullman maids, the subject of a new exhibition she curated at the Newberry. Finally, Newberry fellow LaDale Winling forged a collaboration with WBEZ, Chicago’s public radio station, that encourages homeowners to research the history of discriminatory covenants on their own properties. Professors Thaggert and Winling both teach us how space is demarcated and restricted—asking Who belongs? —while their work also demonstrates the ability of Newberry fellows to bridge scholarly and public audiences.

I hope you enjoy reading these pieces, each specifically grounded in the local, while also informed by questions about national belonging. And, as always, I hope you’ll visit the library for a class, a program, or an exhibition and find the places at the Newberry where you belong.

For us, belonging means more than being comfortable or content in a group of people. It means creating spaces for learning that actively invite multiple perspectives, asking whose stories are told, and by whom.”

“

PRESIDENT’S COLUMN

From Daniel Greene

3

Notable happenings around the Newberry. We are always growing and changing. Grounded in history, engaged with the present, looking to the future.

The Pattis Family Foundation Chicago Book Award to Be

Presented to Dawn Turner for Three Girls from Bronzeville

The Newberry Library and The Pattis Family Foundation are pleased to announce the inaugural winner of The Pattis Family Foundation Chicago Book Award at the Newberry Library. Dawn Turner, author of Three Girls from Bronzeville, will receive the award, which celebrates works that transform public understanding of Chicago, its history, and its people.

“Three Girls from Bronzeville is a bracing memoir that illustrates how race, class, and geography intersect to shape both communities and the individual lives of three women in Chicago,” said Daniel Greene, Newberry President and Librarian. “Dawn Turner’s storytelling embodies the spirit of The Pattis Family Foundation Chicago Book Award, which seeks to advance understanding of our city among readers. We are very pleased to recognize her insightful and deeply moving book.”

In addition to awarding Dawn Turner the $25,000 prize, the Newberry and The Pattis Family Foundation also recognized a group of shortlist award recipients. Each will receive an award of $2,500:

• Elly Fishman, Refugee High: Coming of Age in America (The New Press).

• Tim Samuelson, Louis Sullivan’s Idea (Alphawood Foundation; distributed by University of Minnesota Press). Edited and designed by Chris Ware, who will share the award with Samuelson.

• William Sites, Sun Ra’s Chicago: Afrofuturism and the City (University of Chicago Press).

• Carl Smith, Chicago’s Great Fire: The Destruction and Resurrection of an Iconic American City (Atlantic Monthly Press).

The presentation of The Pattis Family Foundation Chicago Book Award will take place at a free, public event at the Newberry on July 30, when Dawn Turner will receive the award and take part in a conversation about Three Girls from Bronzeville

ANNOUNCEMENT

ANNOUNCEMENT

4 The Newberry Magazine | Spring / Summer 2022

Dawn Turner. Photo courtesy of the author.

New Archival Collections Spotlight Chicago Entrepreneurs

The Newberry’s acquisition of the Prescott Family papers and the Ora Snyder papers will help preserve the stories of two women who built successful businesses from the ground up in Chicago.

Eunice L. Prescott hailed from a long line of entrepreneurs: her grandparents, born into slavery, moved to Texas after the Civil War and ran their own grocery store. In 1919, Prescott ended up in Chicago, where she opened a hat shop before eventually relocating to New York in the 1960s and starting the city’s first Black-owned paint store. In the Prescott Family papers, researchers can find photographs and rare ephemera documenting Prescott’s family history, her business ventures, and her ties to the African American community in Chicago.

While Eunice Prescott was establishing herself as a businesswoman in Chicago, Ora Snyder was expanding Mrs. Snyder’s Home Made Candies to new locations across Chicagoland. Snyder had a knack for marketing, and she built a brand rooted in the humble, friendly persona she cultivated. The candy boxes that carried her chocolates embodied the brand well. Each one was stamped with her own personal guarantee: “I can’t make all the candy in the world, so I just make the best of it!” A set of empty candy boxes, as well as photographs, recipe books, and business records are now part of the Ora Snyder papers at the Newberry.

Newberry archivists are currently processing and organizing both archival collections to make them accessible to researchers.

Eunice Prescott with her team at Ebony Paints, the first Black-owned paint store in New York. 1960s

Ora Snyder (far right) was a pioneering businesswoman who ran Mrs. Snyder’s Home Made Candies, which expanded to several locations in Chicago in the first half of the twentieth century. Above: candy boxes bearing Snyder’s seal of approval.

Eunice Prescott with her team at Ebony Paints, the first Black-owned paint store in New York. 1960s

Ora Snyder (far right) was a pioneering businesswoman who ran Mrs. Snyder’s Home Made Candies, which expanded to several locations in Chicago in the first half of the twentieth century. Above: candy boxes bearing Snyder’s seal of approval.

NEW ACQUISITIONS 5 Take Note

Digitizing 750 Historic Maps

The Newberry recently digitized 750 historic maps produced in Italy in the 15th and 16th centuries. The maps, which come from the Newberry’s Franco Novacco Collection, reflect Europeans’ evolving conceptions of the world during a time of exploration and colonization. Using special cameras and lenses designed for flat art photography, image technicians from the Newberry and the Digital Archive Group created high-definition images that will enable researchers around the world to study these maps in staggering detail. The digitized maps will soon be available as part of the Newberry’s growing, free digital collections. This digitization project was generously supported by Mr. and Mrs. Rudy L. Ruggles, Jr. and Barry Lawrence Ruderman Antique Maps.

MILESTONES

The Society of Collectors Marks 15th Anniversary

The Newberry is home to an extraordinary collection that includes some 1.6 million books, 6 million manuscript pages, and 600,000 maps documenting more than six centuries of human experience. We continually strengthen this collection by acquiring new items that add contemporary and historic materials, enable new research and interpretation, and broaden the diversity of perspectives represented in our collection.

In 2007, several Newberry Trustees founded the Society of Collectors, a group of Newberry donors dedicated to providing funding for acquisitions. Gifts from Society of Collectors members can be used to purchase any item, in any area of current collecting, allowing Newberry curators great flexibility to keep the collection vibrant and responsive to new research and audiences.

“The library receives many wonderful gifts, and generous donors have established funds to support the growth of specific areas of our collection,” explains Alice Schreyer, Roger and Julie Baskes Vice President for Collections and Library Services. “But some subjects do not have special funding, and competition for good material continues to drive prices up. The Society of Collectors is an essential source of funding across all collecting areas.”

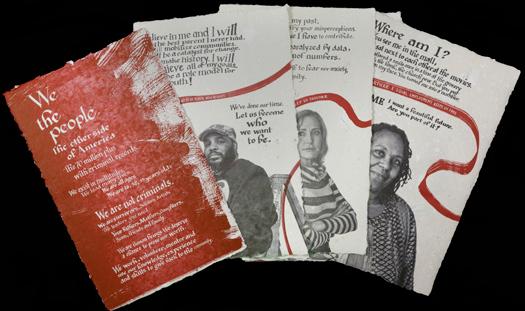

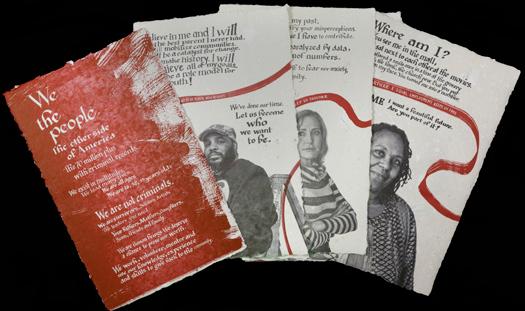

Since its founding, the Society of Collectors has helped the Newberry acquire nearly 700 items. These acquisitions range from a handwritten Nahuatl-language playscript that provides rare documentation of Indigenous theater during the Spanish colonial era to The Reentry Bill of Rights: A Blueprint for Keeping Us Free , a portfolio produced in Philadelphia in 2019 that advocates for the rights of the formerly incarcerated.

“Often these items are of interest to researchers coming from different perspectives,” says Schreyer. “For example, the Nahuatl comedic play connects to our collection’s strengths in Indigenous studies, American history, and performing arts; while The Reentry Bill of Rights, a portfolio of posters that express the ideas of formerly incarcerated people, connects with our collections of artists book collaborations and social reform projects.”

As we celebrate the Society of Collectors’ 15th anniversary, we offer grateful thanks to its members, past and present. If you are interested in making a gift to support the development of the Newberry’s collection, please contact Natalie Edwards, Director of Major and Planned Giving, at edwardsn@newberry.org.

Left to right: The Reentry Bill of Rights: A Blueprint for Keeping Us Free, a portfolio produced in Philadelphia in 2019; a handwritten Nahuatl-language playscript that provides rare documentation of Indigenous theater during the Spanish colonial era.

Image technicians from the Newberry and the Digital Archive Group are digitizing a collection of Renaissance maps published in Italy.

Image technicians from the Newberry and the Digital Archive Group are digitizing a collection of Renaissance maps published in Italy.

PROJECTS

6 The Newberry Magazine | Spring / Summer 2022

By Laura McEnaney

Peacetorn

Chicago After World War II

The stories of military veterans returning home overshadow women like Betty Ackerman, who, displaced from the jobs they held during the war, lived under difficult economic conditions once World War II ended.

FEATURE

Laura McEnaney is the Newberry’s Vice President for Research and Academic Programs. Her research and teaching focuses on the aftermath of World War II, when individuals and institutions battled for a piece of prosperity in an emerging postwar world. This article has been adapted from McEnaney’s book Postwar: Waging Peace in Chicago, published by the University of Pennsylvania Press in 2018.

The Newberry sits in a historic war zone. But the battles here were of a different sort.

In 1945, the Near North Side became ground zero for a struggle over the spoils of World War II. Much of that fight happened from inside the apartments and rooming houses where Chicago’s working class had endured the war. They had served the global conflict as soldiers and civilians, and when peace finally came, they could now more fully voice what they wanted—even expected—in return for their sacrifice. Politicians had promised abundance, but the initial results of peace were a crushing housing crisis, continued shortages of food and consumer goods, and rising prices.

This did not feel like a win. Building the postwar society was the new national project, but it was not yet clear what it would require of a war-weary public. It may have been telling, then, according to one Chicago reporter, that on VJ Day, “everybody talked of the ‘end of the war,’ not ‘victory.’”

This fine distinction between a war’s end and victory offers a chance to ponder how wars come to a close. How are the mechanisms and mindsets of a war dismantled? As a college professor who taught US history for over two decades, I had to talk a lot about war, and I noticed how often textbooks dissected a war’s beginning but spent little time probing its end. The Civil War’s postwar—Reconstruction—is the notable exception to this, and the complex and painful paradoxes of this era led me to fixate on other wars’ “posts.”

Histories of war are too often organized around military and diplomatic milestones. On the ground, however, a war’s progression never follows a neat chronology. The unmaking of an armed conflict is messy, contentious, and often violent; to pinpoint a diplomatic or military end date can miss the important aftereffects and reverberations of war. I still flirt with the idea of creating a “comparative postwars” course, in which war is merely the prelude, not the main event. If we reframe peace not as a date but as a stage of the war itself, we can uncover new and different war stories.

Which brings us to Elm Street , circa 1945. Elm sits just north of the Newberry, within the city’s Near North Side. Here, the war stories come from Chicago’s overcrowded rental housing, filled with a diverse population of old timers and war migrants.

The Near North Side had long been an immigrant neighborhood, populated by Irish, Italians, Germans, and Swedes. During the war, labor migrants came from elsewhere, including African Americans from the South, and a wholly new population of Japanese Americans newly freed from camps, where they had been forcibly relocated and

incarcerated by the US government. Elm was a street of extremes. One of the first sociologists to chronicle the Near North Side described an area of “vivid contrasts . . . between the old and the new, between the native and the foreign . . . between wealth and poverty . . . luxury and toil.”

In Chicago’s rental housing, there was mostly toil. On the 400 block of West Elm Street, Peter and Mary LaDolce were husband and wife managers of an older apartment building in the industrial quadrant of the neighborhood. Their tenants ranged from solidly working class to poor, and the LaDolces were not much better off. They did not own the property, a Mr. Louis Brugger did. But like many owners in the neighborhood, he did not make a home there: he made money there. The LaDolces did not live there either. They were only a few blocks away—a short walk, thankfully, because it was their job to deal with the almost daily needs of people living in close quarters. They paid Brugger a monthly sum, and in return, they made a steady income that allowed them to still hold other jobs and have at least a toehold on future ownership. But to profit, they had to charge rents that exceeded their monthly payment to Brugger. During and after World War II, this was not an uncommon arrangement in Chicago, and it created the perfect conditions for conflict between renters and owners, both seeking their postwar recompense.

As Brugger’s proxies, the LaDolces deceived tenants often, charging above the agreed-upon rent, claiming the extra money was necessary for structural improvements or maintenance, which rarely materialized. Their overcharging caused tenants to double or triple up to absorb the increase, which led the LaDolces to evict the “squatters” who were not in the lease. Tenants with little flexibility in family budgets could either comply or complain, but they couldn’t leave. Chicago’s housing shortage made that almost impossible.

As building managers, the LaDolces were more like the tenants they exploited than the owner they worked for. Their overcharging landed heavily on their tenants, but it did not make them rich. Owner Brugger drew more of the profit, and without the drudgery. Not so for the LaDolces. As hired hands, they had to interact with renters, listen to their complaints, and meet their eyes as they weighed their own financial interests against those they were obligated to house.

The LaDolces’ rent crimes were not unusual. In fact, they point to a complexity that our World War II nostalgia can often cloud. Making peace was hard. Tearing down a war was yet more change and readjustment; it was family reunion or crushing loss; it was negotiation of an economy once again in transition; and it was paperwork, particularly for veterans trying to claim benefits. Americans had sacrificed as a down payment on the celebrated postwar “good life,” and now they sought the reward. Yet how to

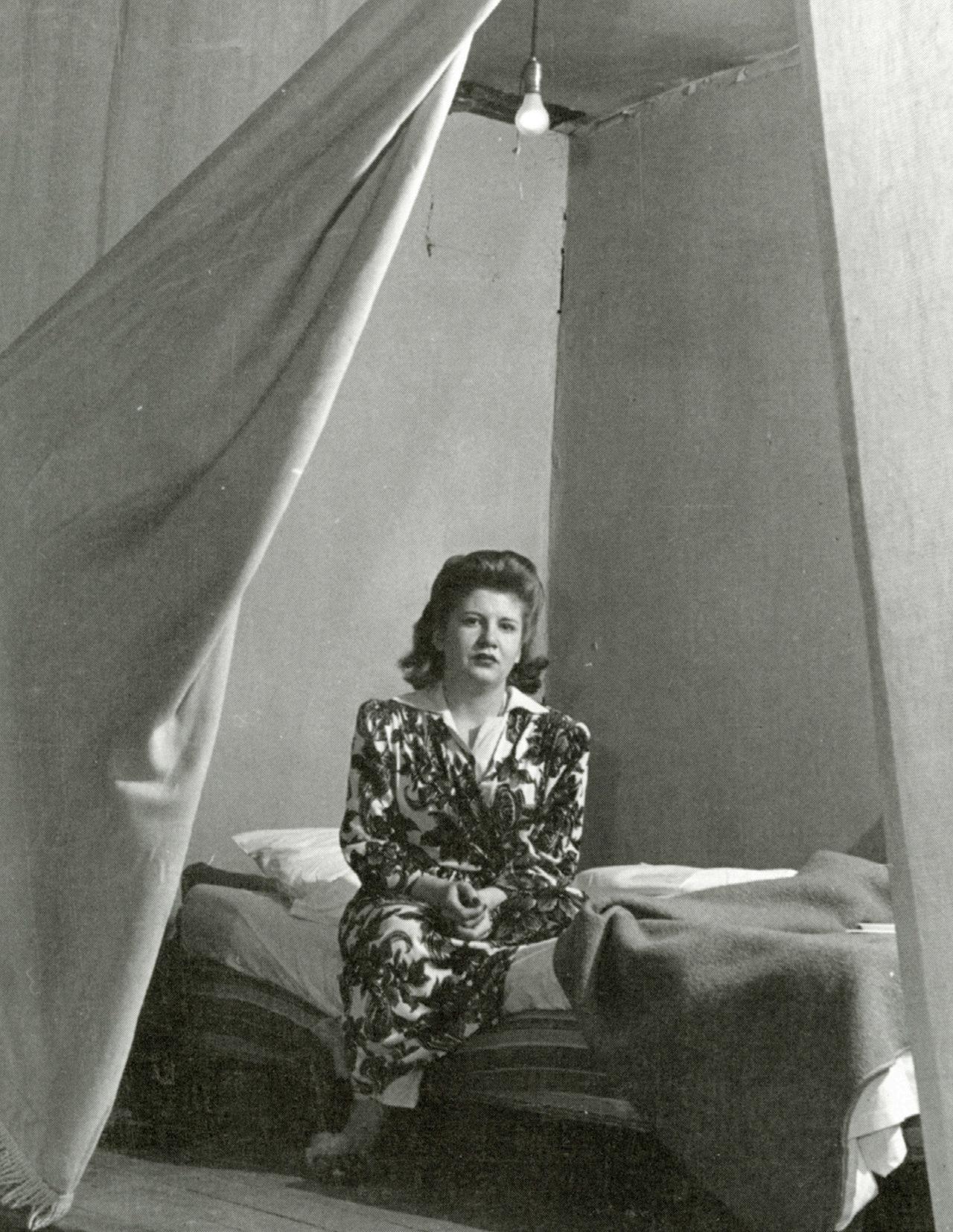

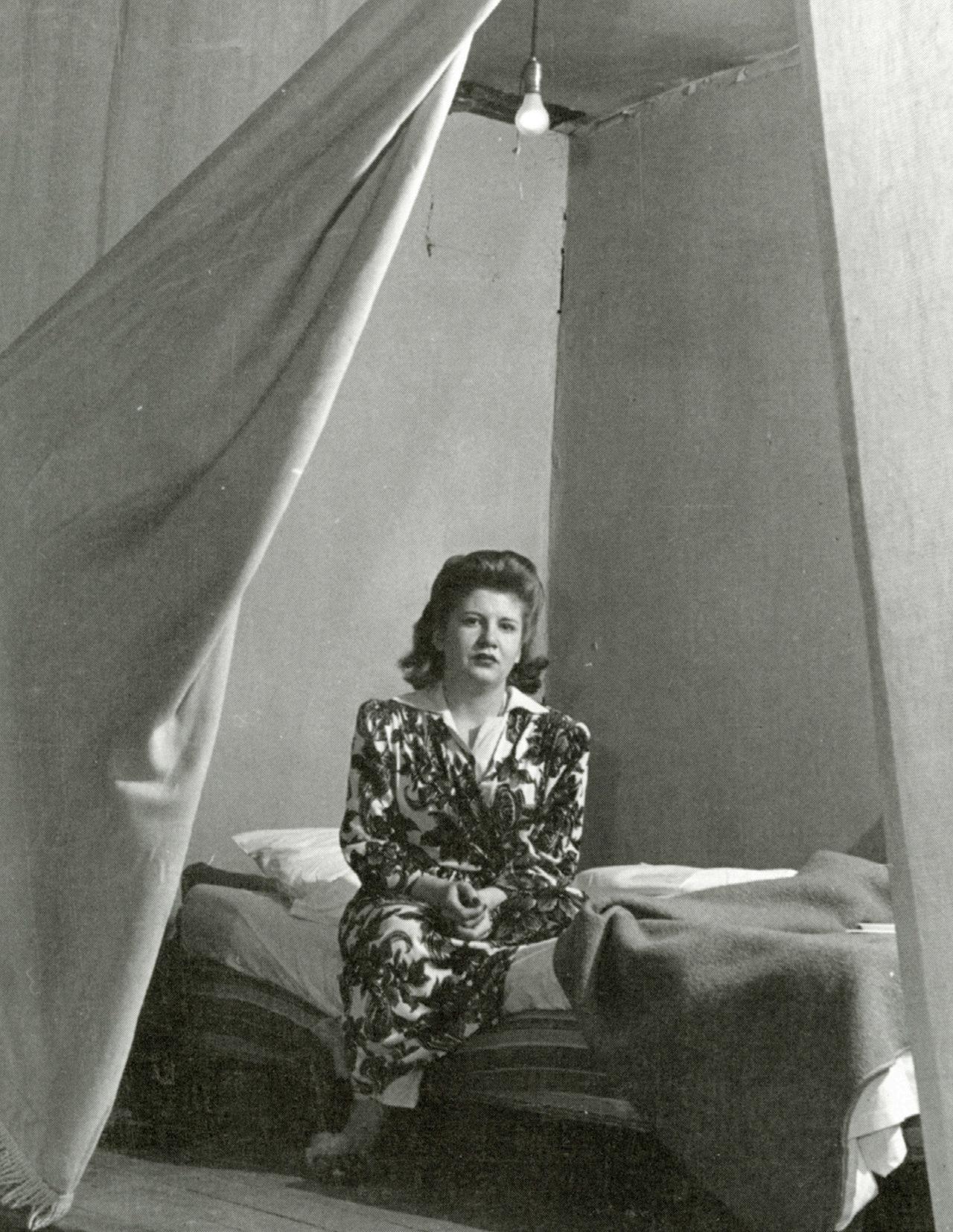

Tent Chicago pg.

8 The Newberry Magazine | Spring / Summer 2022

17

define and secure that reward raised thorny questions about how sacrifice could be measured and repaid—and by whom?

Ifound the smaller stories of a vast postwar transition in a set of case records at the National Archives and Records Administration on the South Side of Chicago. The paper trail begins here because World War II effectively put the federal government in the business of apartment management. Many people recall the government’s rationing program, but few remember its rent control operation. Worried that spikes in housing costs would undercut production (defense workers needed stable, affordable housing to show up to work every day), Congress passed the Emergency Price Control Act in January 1942. Rent control spread rapidly during the war and outlasted it, as it became clear that a wartime housing emergency was becoming a postwar catastrophe. At the end of 1945, federal planners practically ran out of adjectives to describe Chicago’s housing scene: “critical,” “tragic,” “chaotic,” “impossible.” In 1946, fully three-quarters of Americans lived in places where rents were controlled. In 1947, two years after VJ Day, planners feared an “inflationary bonfire,” so they extended rent control into even more urban areas. The reach was unprecedented, but the rationale was simple: sensible controls meant loaded bombers flying east and west during the war and the prevention of an economic crash following the peace.

To make federal law work at the local level, the Office of Price Administration (OPA) and the Office of the Housing Expediter (OHE) set up shop in big and small cities across the country, and Chicago proved to be one of the most important locations. It was the nation’s central railroad depot. Whether civilian or soldier, millions moved through the city. Chicago’s Travelers

Aid Society estimated that between Pearl Harbor and the end of 1945, almost nine million migrating workers, military recruits, and their families passed through the city’s seven train terminals. Two of the military’s largest service centers were located just outside of the city, and Chicago became a branch office for many of the civilian managers of the war. Dubbed “Little Washington” by a Chicago newspaper, the city became home for over a dozen nonmilitary wartime agencies.

In “Little Washington,” landlords could not easily hide their exploitation. Rent control required them to fill out forms that described the amenities and pricing histories of their units. These had to be completed in triplicate, then mailed or hand-delivered to the downtown rent control office, with one copy shared with the tenant. All of this was mandatory, on top of providing tenants with a lease.

It may not surprise us, then, that landlords and building managers got crabby. But when they tried to evade the law, tenants got rebellious. The forms in the case records tell the tale. Every dispute about a rent price or a promised service had to be filed and adjudicated. There were easy questions that could be checked off in a “yes or no” box: Do you have a bathroom? A refrigerator? Hot water? But the forms made space for storytelling, too, and so many of the handwritten pleas, written in sentence fragments and crooked script, offer a poignant chronicle of the economic fragility of the postwar moment.

Back on Elm Street, one mile to the east of the LaDolces’ building, we can see that peacetime did not inspire conciliation. Here, a local dispute became a national headline about the ways in which the postwar housing crisis exploited a particular class of tenant: single working women.

In June 1945, Betty Ackerman took a train to Chicago, leaving her small town of Menominee, Michigan, for a job in a war bond office. A government contact led her to 77 East Elm, a four-story brick mansion converted to rooms and apartments. Landlady Kathrine “Kitty” Stertz had advertised the place as a “residence club” that could house veterans and postwar job seekers, but it was really a rooming house. Ackerman was 19, seeking a job and a wider world, and she fit right in. She shared a room with two other women and a bathroom with twenty others. Over the next nine months, Stertz asked her to change rooms and roommates, as other women left to marry or find better places.

reproduction prohibited without permission.

Tenant Chicago Daily Tribune (1923-1963); Apr 16, 1946; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Chicago Tribune 17

TENT GIRL'S BED IS TAKEN AWAY; OPA SEEKS WRIT: Landlady Denies Evicting Her Basement Guest Chicago Daily Tribune (1923-1963); Apr 17, 1946; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Chicago Tribune pg. 25

TENANT REGAINS HER BASEMENT TENT DOMICILE: OPA Promises Reduction in Rentals Chicago Daily Tribune (1923-1963); Apr 18, 1946; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Chicago Tribune pg. 8

9 Peacetorn

The conflict between Betty Ackerman and her landlord, Kathrine Stertz, made headlines in 1946.

Ackerman was an obliging tenant, sharing with strangers and tolerating the miserly conditions and services of the building. But in March 1946, Stertz decided to move her again, this time inventing a room out of whole cloth—literally. She carved out new territory in the basement, hung a curtain around a bed, put in a chair and table, and called it a room. By this time, the war had been over for months, and Ackerman was now a waitress, not a war bond worker, a demotion back to service work familiar to so many working-class women after 1945. This time, Stertz went too far, and Ackerman filed a grievance with the rent control office. There she learned that others had complained, too. When the federal investigator arrived, he saw a “bad case of inflammatory rents . . . being run as the Landlord pleases.” He interviewed Stertz and she claimed she was in compliance. But when he went into the basement, he found Ackerman’s “tent” and he scribbled in his notes: “have this LL [landlord] into the office Quick—This case is really bad.”

It was really bad. Stertz’s rent-a-tent gambit sits at the far end of the spectrum of landlord misconduct, and, based on the number of complaints, she was a flagrant violator. Still, we have to note that Ackerman’s suffering came at the hands of another single working woman. Stertz, too, was looking for her peace dividend, however unlawful her methods. The case records contain stories from many other female managers who flouted federal controls because their desperation matched their tenants’. Somehow, the press found out about the Elm Street case, and Ackerman’s plight was covered in the Chicago Daily Tribune, even making its way to Time magazine, featuring a picture of Ackerman in her “room” with a caption that read: “Shameful crowding.”

Working “girls” like Betty Ackerman could be found all over the Near North Side, but their economic plight is often overshadowed by the histories of returning veterans. Ackerman told the Tribune , “I’m going to stick it out here now until this OPA [Office of Price Administration] action is finished. . . . There might be other girls who would have the same difficulty I had here unless I fight the thing out.” Constructing a postwar narrative for these working-class women is tricky, for their timetables and trajectories don’t match up neatly with military campaigns. For the most part, they have no “coming home” story. The government drafted them into service indirectly, with no G.I. Bill at the end of that service, unless they married a veteran. Ackerman wasn’t Rosie the Riveter, but she wasn’t a postwar June Cleaver either. Like many working-class women, she stayed in the city after the war. Rent control was her safeguard, maybe even a springboard into abundance as a working-class waitress from a small Michigan town who was trying to build a life.

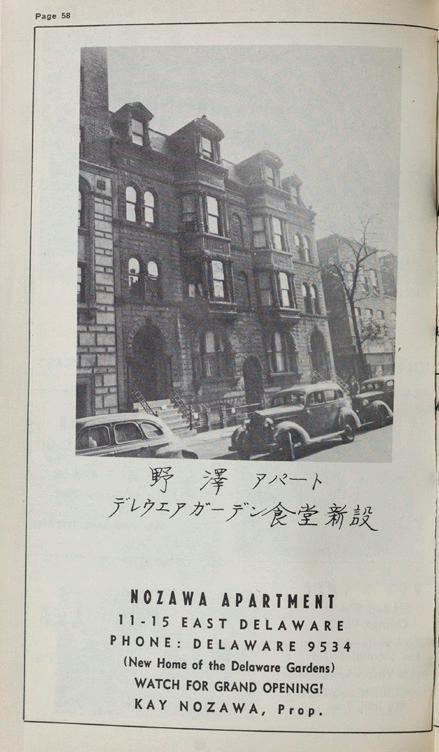

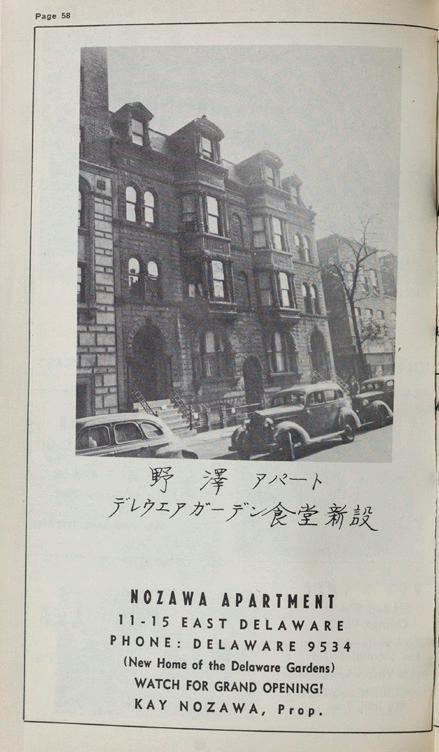

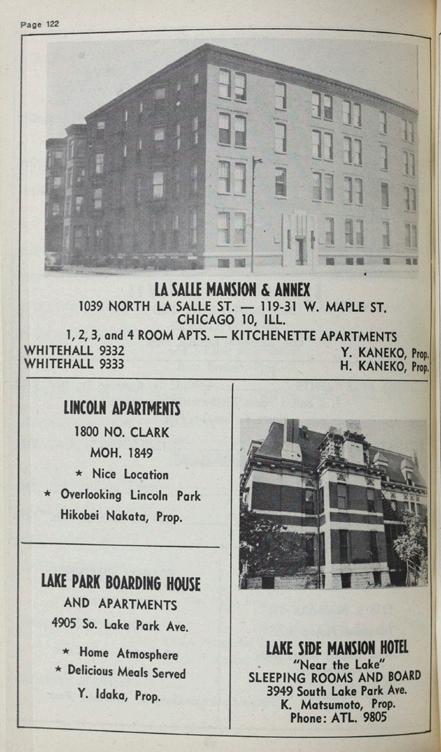

Alast story from the case records muddles even further war’s timelines. Not far from Elm Street, we find a vibrant community of Japanese American renters in the area of Clark and Division. After having been rounded up and imprisoned after Japan’s bombing of Pearl Harbor, they were eligible to apply for a “work release,” which ended their incarceration but still did not free them completely. They were not war migrants but war refugees. The first Japanese Americans on release arrived in Chicago in June 1942, with a larger wave arriving in 1943; the in-migration lasted until 1950. This makes for a weird war timeline; thousands ended their wartime detention only to live more freely in a city still deeply at war. And they kept coming in the postwar period, even after the camps closed and the government allowed them to return west.

Approximately twenty to thirty thousand “resettlers,” as the government called them, went to Chicago, making the city “the primary center of relocation in the United States,” according to the War Relocation Authority (WRA), the agency in charge of removal. By 1947, so many had arrived in Chicago that the chances of encountering another Japanese American who had not been imprisoned were almost nil; by the WRA’s count, 97 percent of the Japanese Americans walking around Chicago had come from the camps. Their resettlement “headquarters” was on the Near North Side. Indeed, the Newberry sits in the middle of what was a vibrant and wholly new Chicago Japanese American community during and after the war.

This did not mean their transition was smooth. Finding housing on the Near North Side was hard for anyone, but rent control cases reveal formidable challenges for Japanese Americans. After suffering a race-based violation of their rights, they now had to probe Chicagoans’ racial attitudes, house by house, bracing for resentment, hoping for acceptance. Stories of the moment when they followed an ad or word of mouth to knock on a door to ask about a vacancy reveal variety and texture in the racism they encountered. Some Japanese Americans found German American landlords more willing to accept them as tenants because of their own memories of World War I’s home front anti-German slander. Others encountered an early version of a model-minority stereotype, allowed to rent because they were perceived as “clean” and “quiet.” Most refugees faced everything from flat-out declarations of “No Japs!” to a series of polite dodges. What jumps out of these resettlement stories is the sense that they were engaged in a humiliating racial audition. Remarkably, after being rounded up and imprisoned, one Japanese American woman called apartment hunting in Chicago “the hardest thing I ever did in my life.”

To evade this trial, Japanese Americans pooled their finances and bought their own buildings, enabling them to rent to their own. Japanese American owned or managed housing offered a

10 The Newberry Magazine | Spring / Summer 2022

Constructing a postwar narrative for these working-class women is tricky, for their timetables and trajectories don’t match up neatly with military campaigns. For the most part, they have no “coming home” story.

lifeline to arriving refugees. But here, too, we cannot presume either a wartime or postwar solidarity. In a rooming house on West Superior, a Mr. Watana filed a complaint against his Japanese American building manager, telling regulators that John Motoda was overcharging him. “I’m not understand so mutch [ sic] charge,” he said, especially “for only Jap tenat [sic]” in the building. Like the LaDolces, the Motodas were a husband and wife management team for this hospital turned rooming house, but after only seven months, they left and the next Japanese American building manager made the same choice to overcharge the residents.

Collectively, these specific stories reveal the stakes of the grand transition from war to peace, and why Americans fought one another for war’s spoils. What did it mean to win? What would the peace deliver for the weary winners? These questions were worked out on the ground first, so the details from inside Chicago’s apartment housing matter: no hot water, missing toilet paper, an absentee landlord. In diplomacy, it is often the treaties that define the outcomes of a war. Wars still matter, but it is their precarious “posts” that redraw the world that survivors will inhabit. This was as true on the home front as it was on the battlefield. Working-class Chicagoans turned to their government to write the treaties on the crucial bread-and-butter issues like the cost of rent. The sacrifices had not been equal, and yet still all felt

entitled to prosper. As a result, the pursuit of postwar affluence became combative. These, too, are “greatest generation” stories of individual resolve, idealism, and enterprise, all for a better life after the war. But they are also tales of what Americans did for themselves and to one another as they tried to achieve that better life.

My aim here is not to deny this generation its heroics but to relieve it of a burdensome mythology that hides its complexity and humanity. We need to freeze the action in the postwar city before we so quickly look to postwar suburbia. The fact that US involvement in World War II was punctuated by Pearl Harbor and Hiroshima makes it tempting to adopt a conventional timeline, but we have to be willing to sit with chronological fuzziness. World War II had many and varied endings for people—chronological, geographical, material, even emotional. We need to think about peace as a process. If we dissect our postwars as carefully as we do our wars, we can uncover—and teach—new war stories.

Portions of this article have been excerpted with permission from the University of Pennsylvania Press. Postwar: Waging Peace in Chicago. Copyright 2018: University of Pennsylvania Press. Learn more at https://www.pennpress.org/9780812250558/postwar/

11 Peacetorn

Laura McEnaney is Vice President for Research and Academic Programs at the Newberry.

Japanese Americans faced discrimination in the rental market after World War II. In the 1947 Chicago Japanese American Yearbook, renters could find listings for properties that would welcome them.

COVER STORY

By Jim Akerman

Crossings: Mapping American Journeys

Places like Navajo Bridge inspired the Newberry’s current exhibition, Crossings: Mapping American Journeys. These sites speak to the movements of Indigenous people, emigrants and immigrants, and modern tourists—all of whom had decidedly different experiences moving throughout the United States and its territories.

ne of my favorite places on earth is Navajo Bridge, in northern Arizona. The bridge—two bridges actually, an older one reserved for pedestrians and a modern one for vehicles—crosses the Colorado River as it rushes through Marble Canyon, which becomes the Grand Canyon a few miles downstream to the south. To the north and east are the stunning orange-pink Vermillion Cliffs, the southernmost step of the Grand Staircase, which stretches nearly 100 miles into Utah as far as Bryce Canyon.

My family first visited the bridge in 2002, and on a later trip, I insisted that we make a nostalgic stop at the bridge once again on our way to Sedona, Arizona. The geology hadn’t changed much since we’d last been to the area, but there were now gift shops and hotels on the western side of the bridge, some of them operated by the Navajo (Diné) Nation, whose western limit follows the Colorado River here. I bought a T-shirt to commemorate our visit at a Native-owned gift shop and pondered how the scenic bridge straddles not only a geological boundary but also a legal boundary between two sovereign nations, the Diné and the United States.

We drove a few miles north of the bridge to Lee’s Ferry, the only place for hundreds of miles in either direction where, for many decades, one could approach both banks of the river with wheeled vehicles. The place takes its name from John Doyle Lee, a Mormon who established the ferry in 1870 to serve migrants in the Church of Latter Day Saints and others who passed this way on a largely forgotten emigrant road. Lee was later arrested and executed for his role in the 1857 Mountain Meadows Massacre of a group of non-Mormon emigrants, but the ferry remained in operation until it was superseded by the construction of the first Navajo Bridge. Today, Lee’s Ferry is the primary launching place for commercially operated rafts that take tourists on a scenic journey downriver through the Grand Canyon. From a height of 470 feet, pedestrians on the old Navajo Bridge can wave at the rafters far below as they drift south in excited anticipation.

Places like Navajo Bridge inspired the Newberry’s current exhibition, Crossings: Mapping American Journeys . These sites speak to the movements of Indigenous people, emigrants and immigrants, and modern tourists like my family—all of whom had decidedly different experiences moving throughout the United States and its territories. The geographical coincidence of these travel experiences is particularly evident at Navajo Bridge. But of course virtually every place in the United States has these multivalent connections to American journeys, past and present. Crossings tells these stories, using maps, texts, images, and testimonies from the Newberry’s collection that allow visitors to look closely at the past and present of multiple sites throughout the contiguous United States.

“Crossings” has a dual meaning here, geographical and experiential. The main gallery of the exhibition is laid out like a map of the continental United States, with the north, south, east, and west walls of the gallery corresponding to the cardinal directions on a map. We’ve organized this map using four pathways across the continental United States that have endured through technological transformations, from foot and horse paths and natural waterways to canals, railroads, and automobile highways.

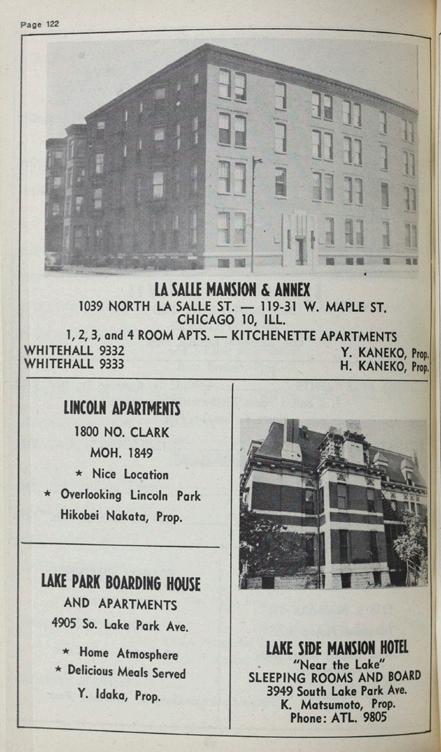

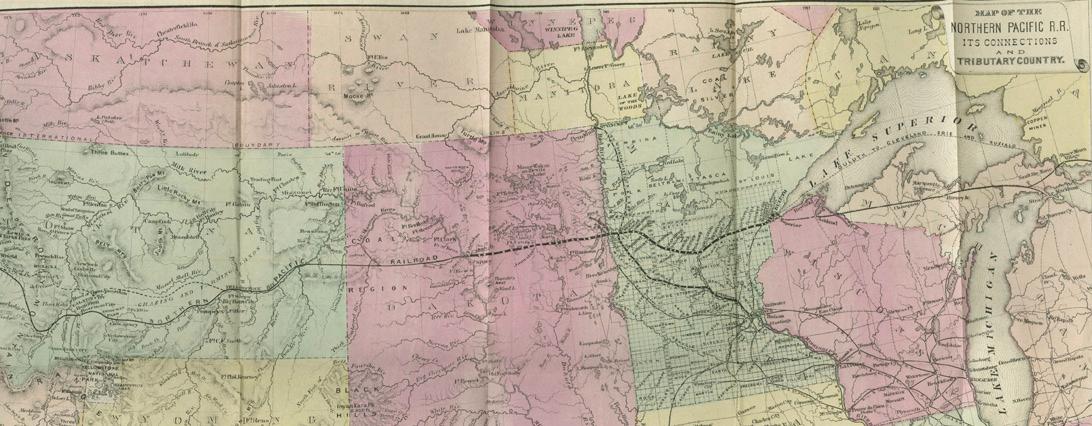

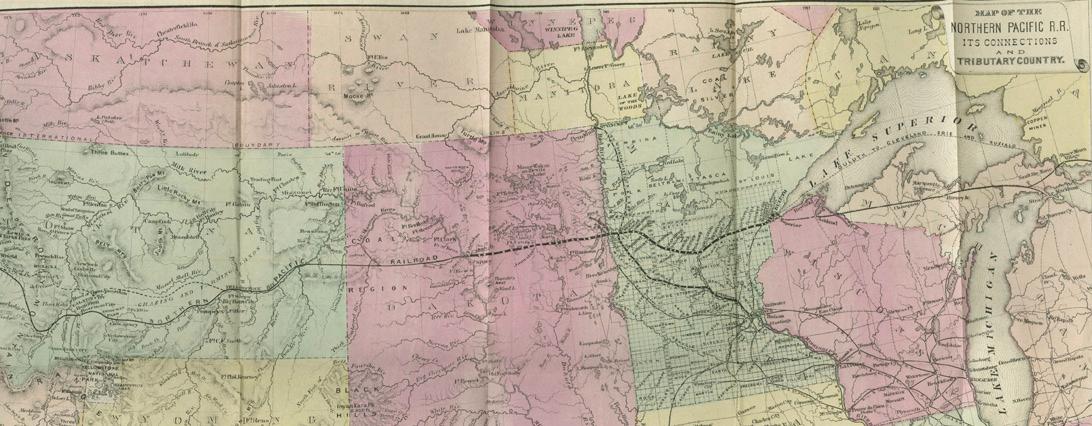

Items along the Northern Passage, for example, trace a pathway from New York City to Seattle and Puget Sound via the Hudson River, the Erie Canal, the Great Lakes, and the Northern Pacific Railroad. A route crossing the central belt of the country, or the Main Street of America, runs from San Francisco in the West to Baltimore in the East. Along the way it embraces the California Trail, the Union Pacific Railroad, US 40, Interstate 80, the Ohio River, the National Road, the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal, and the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. The Southern Crossing in the exhibition gallery traces the southern border of the United States from Miami through New Orleans, El Paso, and Los Angeles. Coastlines, rivers, roads, railroads, and boundary monuments make up this route, characterized by the historic, cultural, and economic

14 The Newberry Magazine | Spring / Summer 2022

Inside Crossings: Mapping American Journeys, open February 25 through June 25, 2022 in the Newberry galleries.

O

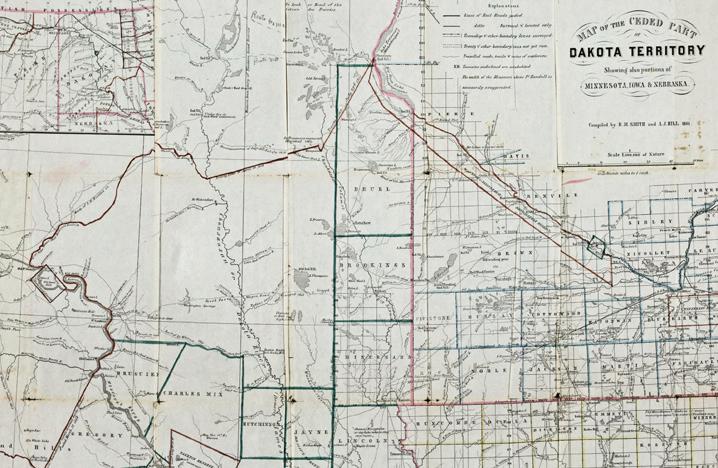

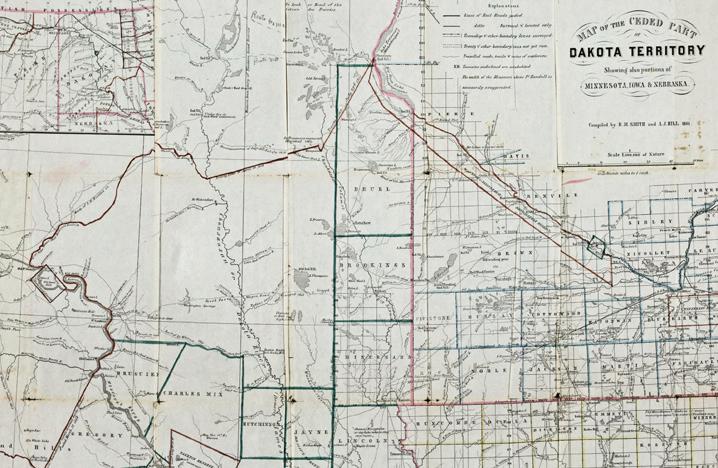

Left: An 1863 map illustrates the displacement of Indigenous peoples in the Dakota Territory.

Below: An 1872 map published by the Northern Pacific Railroad promotes German immigration to areas taken from the Dakota (Eastern Sioux) and Ho-Chunk (Winnebago) people.

ties among the southern United States and the Caribbean Sea, Gulf of Mexico, and Mexico itself. Finally, running through the center of the gallery is The Father of Waters, the Mississippi River and its manmade parallels, the Illinois Central Railroad and US 61, known to some as the “Blues Highway.”

This geographical layout of the gallery provides curious visitors with an opportunity to explore the second meaning of “crossings”: the experiences of travelers along these routes over the span of US history. These travelers include tourists, for whom journeys may be diversions from everyday life, though—as the layers of history embedded in Navajo Bridge make clear—not without significance. Crossings also centers the experiences of migrants at the heart of the exhibition; for a migrant’s passage from one place to another is also a crossing from one stage of life to another. This has been true across time and place in a variety of ways for European, Chinese, and Mexican immigrants coming to the United States; for Indigenous people who were forcibly removed from their homelands by non-Native colonization; and for refugees from enslavement on the Underground Railroad.

The geographical arrangement of the gallery allows visitors to engage with these diverse travel experiences side-by-side. Along the Northern Passage, for example, an 1872 map published by the Northern Pacific Railroad promoting German immigration to the northern Great Plains sits next to an 1863 map documenting the removal of Dakota and Ho-Chunk bands from western Minnesota and eastern Dakota in the aftermath of the US-Dakota War. Similarly, a map designed for tourists visiting Midtown Manhattan in the mid-1960s hangs next to a map of the crowded Lower East Side in 1902, representing the enormous role that New York City played in the history of immigration, especially by European Jews, to the United States.

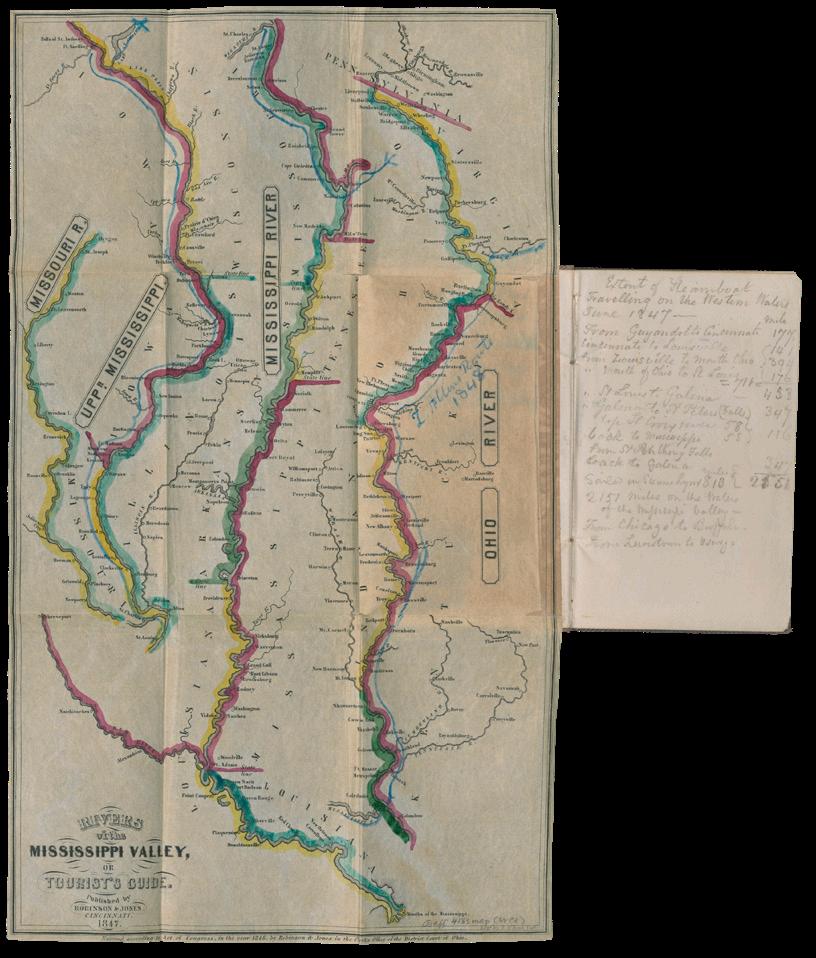

Throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, maps and guidebooks were important facilitators of and witnesses to the complex history of travel and migration in the United States. In some cases, these maps and guidebooks bear the traces of specific travelers who used and consulted them on a journey.

The introductory gallery of Crossings features three maps, all related to the Midwest in the 1830s and 1840s, that represent

15 Crossings

In the 1830s and 40s, printed guidebooks laid out the growing network of roads, turnpikes, waterways, and railways to aid travelers on their journeys. Some travelers, like Rhode Island industrialist Zachariah Allen, personalized their guidebooks by adding their own observations.

very different perspectives on travel and migration in the region. The oldest of these is a map, now in the National Archives, created in 1837 by members of the Ioway nation. An Ioway delegation presented the map in Washington to C. A. Harris, the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, during a council called to resolve land disputes between the Ioway and their neighbors, the Thakiwaki and Meskwaki (Sacs and Foxes), who themselves had been displaced from their homelands in Illinois and Wisconsin to Iowa and Minnesota. The map shows the history of migrations and settlements of the Ioway in the previous centuries throughout the upper Mississippi Valley.

As assistant curator Gabrielle Guillerm explains: “To the Ioway, their homeland was much more than the current villages they inhabited. Rather, it was the villages in which they lived, the routes they had traveled, and the lands where the bones of their ancestors lay. As Ioway leader Non-chi-ning-ga (No Heart of Fear) told [Commissioner Harris] . . . ‘This is the route of my forefathers. It is the land that we have always claimed from old

times.’” (Dr. Guillerm’s work on the exhibition has been supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from the Nicholas D. Chabraja Center for Historical Studies at Northwestern University.)

A second map in the introductory gallery presents the perspective of a German migrant, Otto Rollman, to the new state of Wisconsin, carved out of the former homelands of the Ioway, the Sac, Fox, Anishinaabe (including the Ojibwe, Odawa, and Potawatomi), the Ho-Chunk (Winnebago), and many other Indigenous nations. An inscription on the inside cover of this folded map of the United States published in Germany tells us that Mr. Rollman bought it in 1844, “before his immigration to the United States [in] 1848 when he settled in Wisconsin.” The display of the map is accompanied by a view of Mr. Rollman’s farm from a county atlas published in 1874.

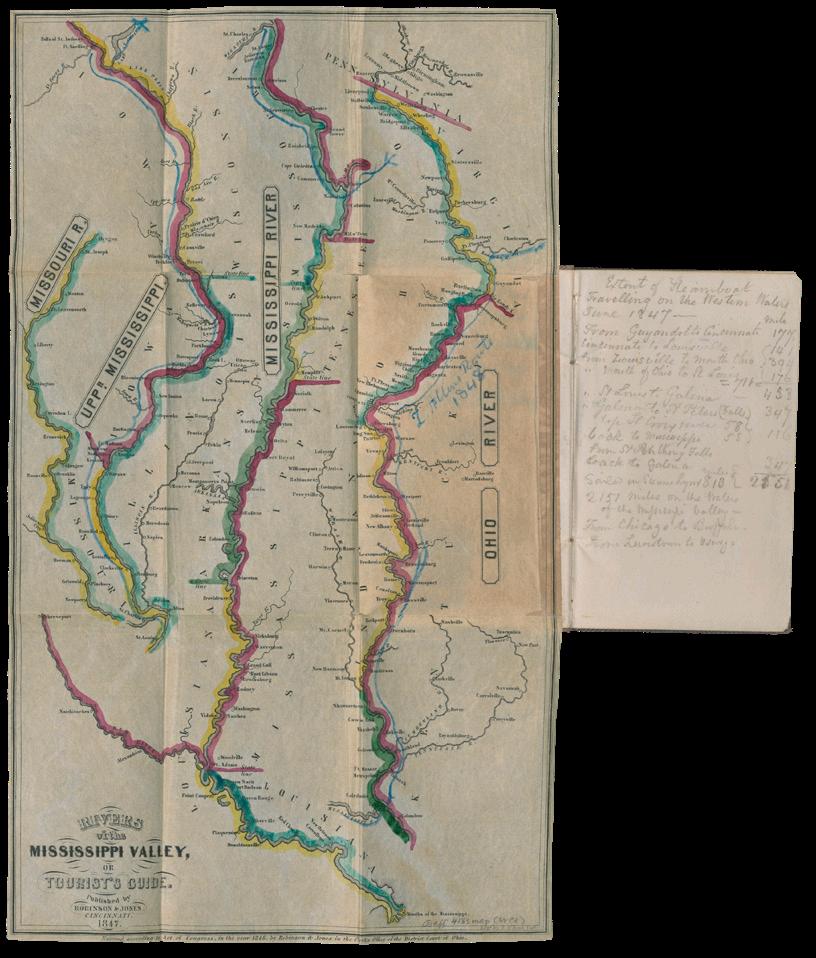

A third map, folded into The Traveller’s Register, and Road and River Guide , published in Cincinnati in 1847, shows the route of the “journey of Mr. and Mrs. Z. Allen [Eliza] & daughters & Mr. & Mrs. James Arnold of New Bedford, Mass. to the Falls of St.

16 The Newberry Magazine | Spring / Summer 2022

Anthony in 1848.” This party of tourists was led by Zachariah Allen, a prominent New England industrialist, inventor, and owner of several woolen mills. By Allen’s calculation, the party traveled nearly 5,000 miles: by stage and rail overland from Providence to Baltimore; then westward on the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad as far as Winchester, Virginia; by stage to the Ohio River at Guyandotte (modern Huntington, West Virginia); and finally by riverboat down the Ohio and up the Mississippi as far as Minneapolis.

Taken together, these three maps underscore a central theme of the exhibition: the histories of tourism, migration, and forced migration in the United States cannot be disentangled from each other. They often occurred simultaneously, as well as over time, on the same geographical stage. The Newberry collection items on display also demonstrate the importance of maps and guidebooks to historical travelers, who used them to form opinions and shape memories of the regions through which they traveled and lived. These objects are preserved in the Newberry’s collection only because their original owners decided to save them as markers of their journeys.

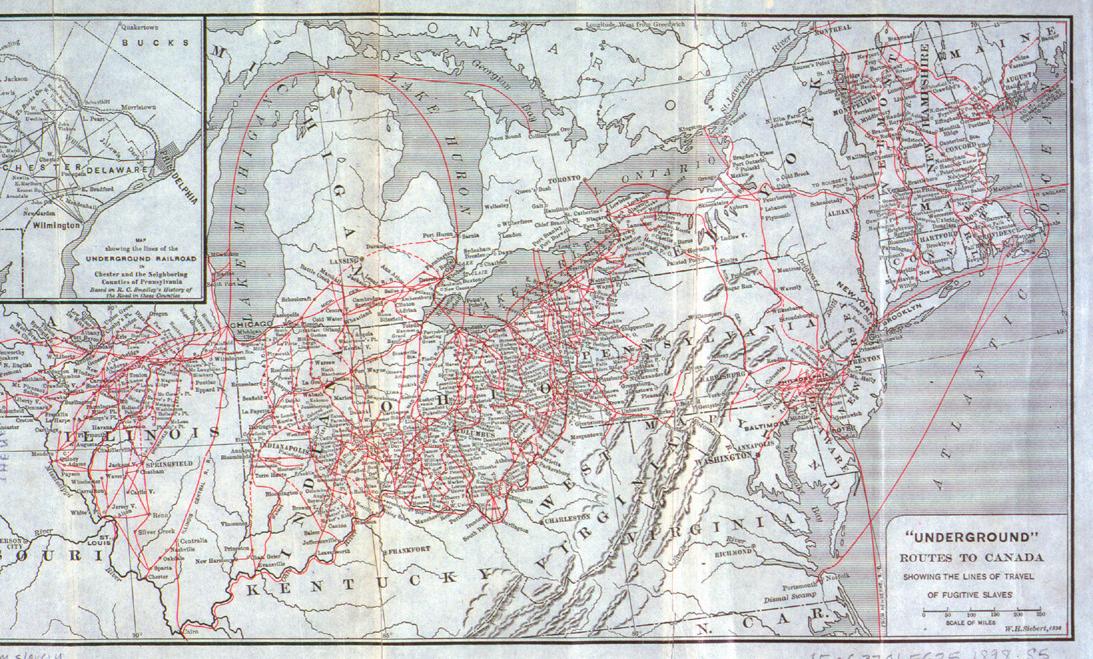

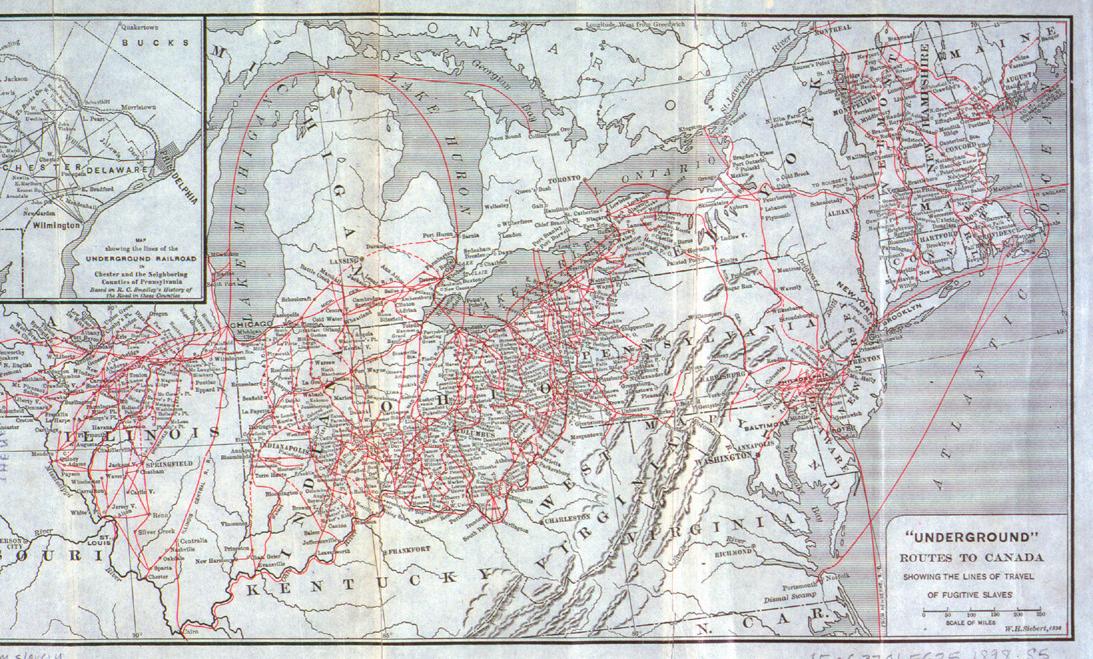

Not all travelers, however, had physical maps to guide them. In some cases, journeys remained unmapped by necessity. Such was the case of the many thousands of enslaved people on the Underground Railroad who sought their freedom in the North and in Canada. Their routes followed similar patterns but were unique to each party and were secret and ephemeral by design.

The first comprehensive attempt to map these routes was undertaken by Wilbur Siebert of Ohio State University. Drawing on hundreds of interviews with formerly enslaved people, Siebert published a map summarizing his findings in 1898. Visitors to the exhibit will find his map next to a video prepared especially for Crossings by Karen Lewis, Associate Professor of Architecture at Ohio State University and a former Newberry fellow. Drawing on the archives of Siebert’s project and on published accounts, Dr. Lewis created three animated maps showing key moments in the northward journeys of three refugees from enslavement, accompanied by narrations in the travelers’ own words or as told to others.

In cases such as these, it is necessary to read between the lines of historical maps to tease out the experiences of individual travelers or communities. As exhibition visitors travel along the Southern Crossing, they will see two maps that illustrate the tragic history of the Trail of Tears, the forced migration of 16,000 Cherokee people in 1838 from their homeland in parts of Georgia, Alabama, North Carolina, and Tennessee. One display features a map by the ethnologist Charles C. Royce chronicling the successive land cessions made by the Cherokee to colonizing powers between 1721 and 1835. The mapped record bears witness to the geographical contraction of a people who once shared with neighboring tribes a vast territory stretching from the Ohio River to the southwestern Appalachians and all the way to northwestern Alabama.

17 Crossings

Drawing on hundreds of interviews with formerly enslaved people, Wilbur Siebert created a map showing the routes of the Underground Railroad in 1898.

This

Next to Royce’s map is an 1836 map of the Indian Territory reserved for the many tribes that had been removed from east of the Mississippi River. The Cherokee were assigned a strip of land across the northern part of what became Oklahoma, alongside the Creeks, Choctaws, and Chickasaws, and other eastern nations. Several bands of Cherokee, however, refused to migrate, in defiance even of their own tribal leaders. These people mostly settled on the southern slopes of the Great Smoky Mountains, within what is now known as the Qualla Boundary. In Crossings, their story is represented by a brochure for tourists publicizing “Unto These Hills,” an outdoor drama (staged for the first time in 1950) that presents a sympathetic but partially fictionalized account of the Eastern Band’s refusal to leave their homeland. Although the play was originally performed by white actors, in recent decades the Eastern Band has gained greater control of this dramatic production and its message.

While viewing these maps, visitors can hear the words of William Shorey Coodey, an eyewitness to the Cherokee Trail of Tears, part of an audio tour of Crossings that highlights eight narratives from the exhibition.

Crossings also includes an interactive Google StoryMap as part of the Father of Waters story. In words, pictures, songs, and maps, the digital interactive relates the stories of Muddy Waters, B. B. King, Koko Taylor, Howlin’ Wolf, Robert Johnson, and the Staples Singers. Their music, along with many of the musicians themselves, migrated from the Delta region of Mississippi to Chicago. The route they took is shown on a 1940 timetable for the Illinois

Central Railroad, which passed through the Delta on the journey from New Orleans to Chicago, and carried thousands of African Americans migrating northward during the Great Migration.

One challenge in curating Crossings was summarizing the complex history of southern California as a destination for tourists and migrants alike. Newberry Program Coordinator Madeline Crispell and I worked with the video production company Truth & Documentary to create a video exploring the many ways in which California has positioned itself for tourists and migrants. Through images of maps, postcards, travel brochures, and film footage, the video offers impressions of the history of travel and migration to metropolitan Los Angeles, focusing on tourism, industry, agriculture, migrant laborers, and the fantasylands created by Hollywood and Disneyland.

The three columns in the gallery display an 1846 panorama of the Hudson River; postcards from the Newberry’s vast Curt Teich Postcard Archives Collection featuring the cities, economy, and natural attractions of the Great Lakes; and images of scenery and Indigenous people from an 1854–55 survey of the proposed Pacific Railroad route.

The geographical organization of Crossings encourages exploration in multiple directions. At the heart of the exhibition are displays that place two or three objects in conversation with each other, offering contrasting perspectives on the experience of travel in the same location.

In the introductory gallery, for example, an 1893 map of the grounds of the World’s Columbian Exposition, which attracted

18 The Newberry Magazine | Spring / Summer 2022

1884 map shows Cherokee lands ceded—first to the British and then to the Americans—culminating in the Trail of Tears, when thousands of Cherokee people were forced to travel from their lands in the Southeast to the newly created Indian Territory west of Arkansas and Missouri.

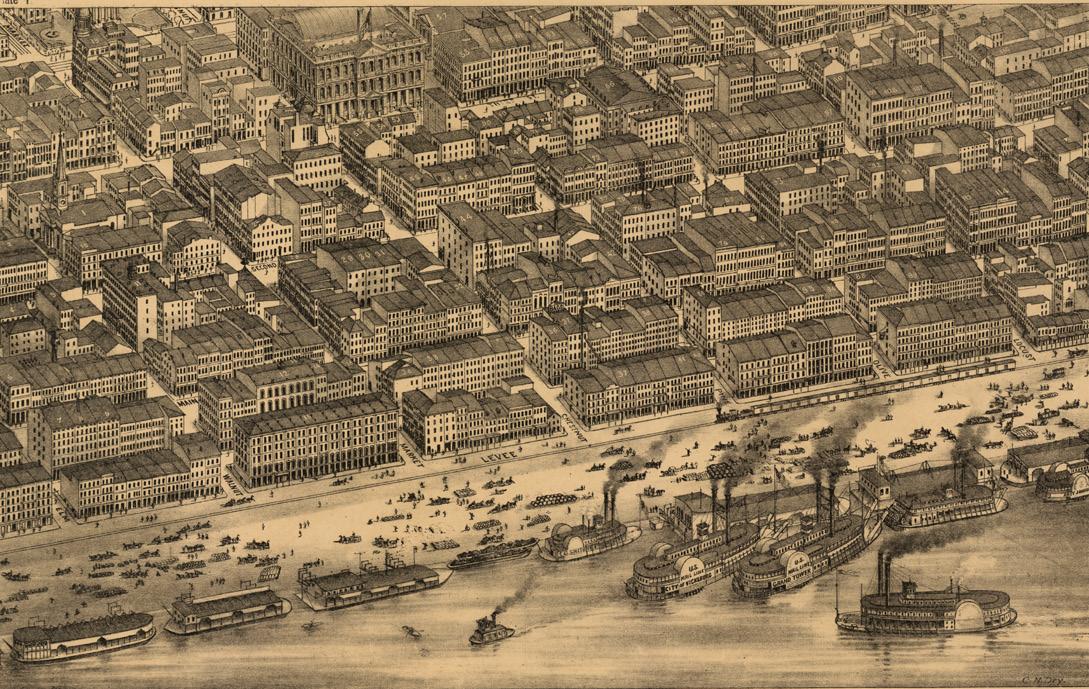

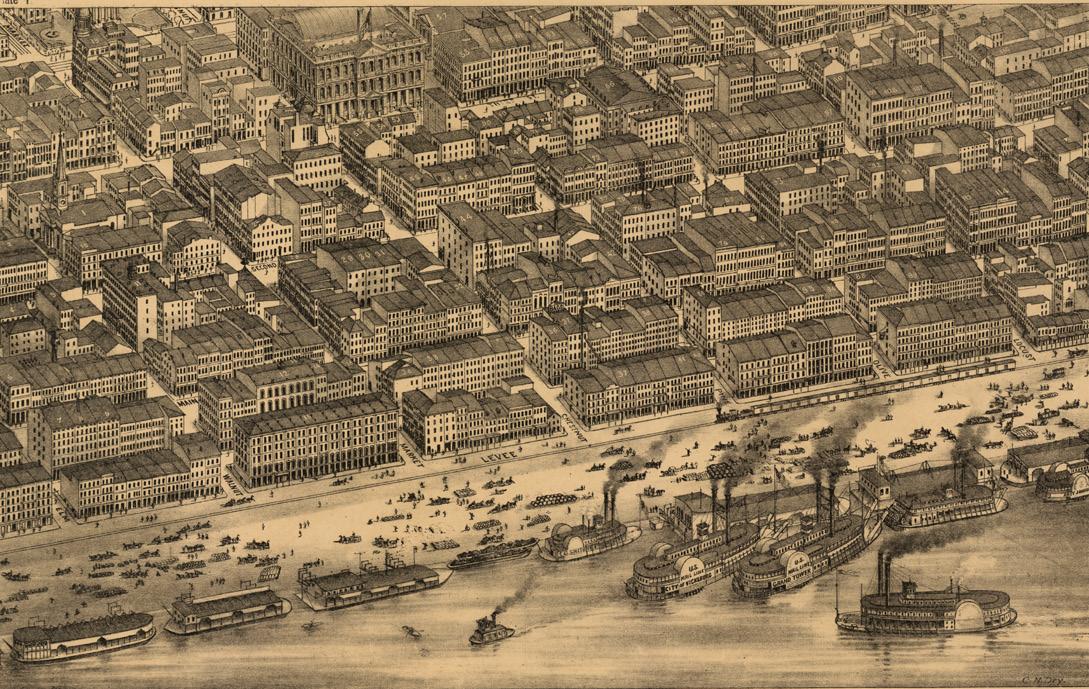

millions of tourists to Chicago, sits alongside the landmark 1895 map compiled by the residents of Hull House showing the ethnic diversity of the crowded immigrant neighborhood abutting the famous settlement house. “Mississippi Crossroads” juxtaposes a view of the busy waterfront of St. Louis with an early view of the remains of Cahokia, the Native metropolis of the midcontinent that existed several centuries before the arrival of Europeans. Several hundred years apart, both cities occupied a strategic crossroads

near the confluence of the Missouri, Illinois, and Ohio rivers with the Mississippi. “Crossing to California” places side-by-side an 1849 map made for participants in the California Gold Rush with a 1955 map intended for automobile tourists crossing the Sierra Nevada through Donner Pass on US Route 40. This “Fun Map” makes for an odd mix of modern recreational opportunities among sites associated with the Donner Party’s tragic crossing of the same route in the winter of 1846–47.

On the surface, maps may seem objective and scientific. When you spend a little time with them, however, they always tell a deeper story—about the experiences of a traveler, the cultural values of a community, or the relationships between people and institutions. The maps on view in Crossings reveal a diversity of experiences and a range of decisions travelers made (or were forced to make) as they moved across the United States. Beyond the Newberry’s exhibition galleries, there are 600,000 additional historic maps awaiting to be discovered in the library reading rooms. Each has a story to tell.

Crossings: Mapping American Journeys is generously supported by Rand McNally, the National Endowment for the Humanities, Jossy and Ken Nebenzahl, and Andrew and Jeanine McNally.

Jim Akerman is the Director of the Hermon Dunlap Smith Center for the History of Cartography and the Curator of Maps at the Newberry.

19 Crossings

Above: A view of the remains of Cahokia appears in The Valley of the Mississippi: Illustrated in a Series of Views (1842). Below: The busy waterfront of St. Louis, in Pictorial St. Louis: A Topographical Survey Drawn in Perspective (1876).

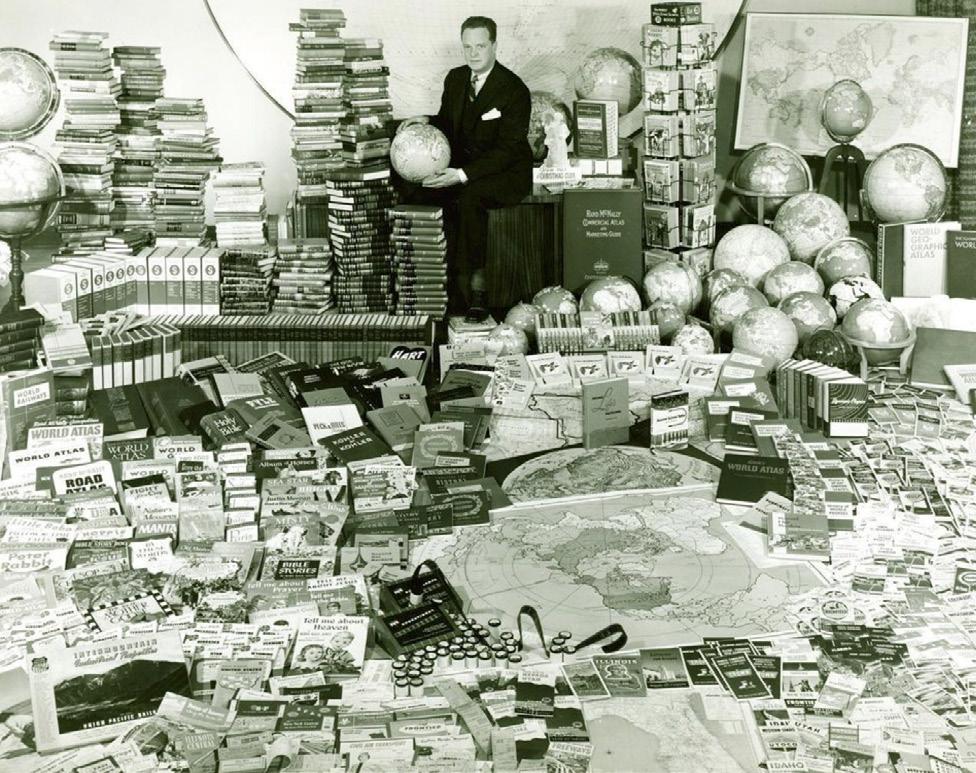

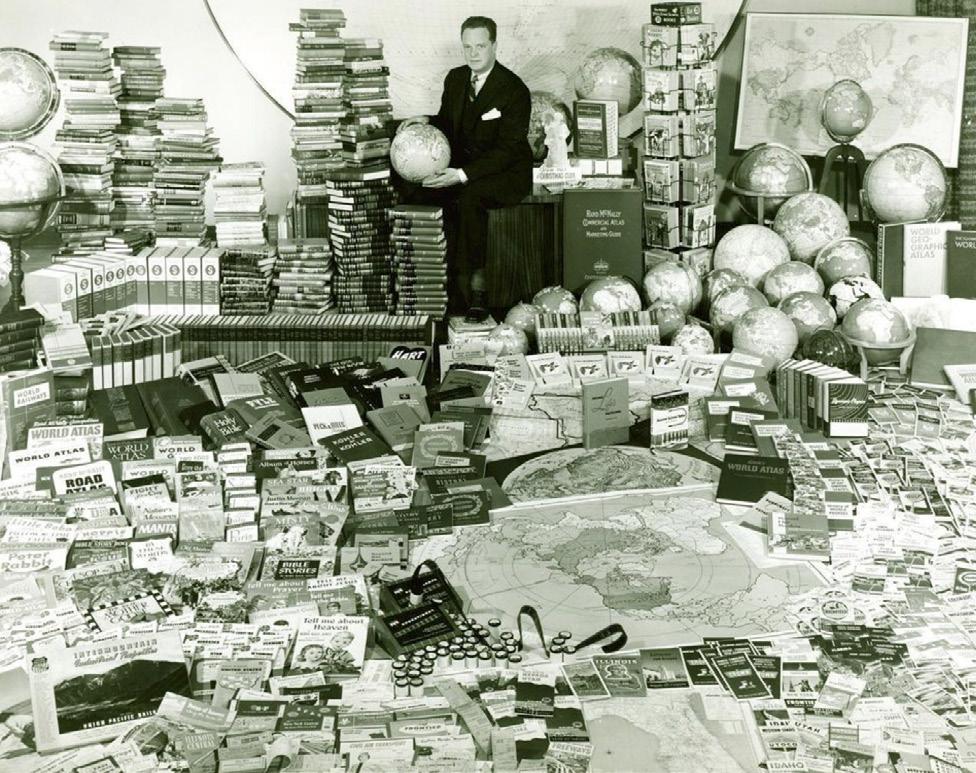

Rand McNally and the Newberry

Crossings is presented with the support of Rand McNally, a longtime corporate partner of the library.

Founded in Chicago in 1856 by William Rand and Andrew McNally, the company became a pioneer in American travel mapping. In fact, it was the first major map publisher to embrace a system of numbered highways, now a ubiquitous feature of American roads.

In 1989, the company donated its massive historical archive of maps, globes, travel guides, and more to the Newberry. “It wasn’t just ‘take these papers off our hands,’” recalls Andrew “Sandy” McNally IV. Sandy served as Rand McNally’s chairman from 1974 to 1997. He has also been a trustee of the Newberry since 1975. “We made the 1989 donation in cooperation with the library because we wanted people to be able to actually access the materials. After all, what’s the point of an archive if no one can use it?”

The donation was transformative for the Newberry. “It made us a go-to destination for researching travel cartography and inspired donations from other major map publishers,” says Jim Akerman, the Newberry’s Curator of Maps. “Without that gift, current projects like Crossings probably wouldn’t be possible.”

Over the last three decades, Rand McNally has continued to support the Newberry’s work to make its cartography collections freely accessible and relevant. We are deeply grateful for the company’s continued philanthropy and are pleased to be able to present Crossings: Mapping American Journeys with its support.

20 The Newberry Magazine | Spring / Summer 2022

Andrew McNally III with Rand McNally products

Working on the Railroad

An Interview with Miriam Thaggert

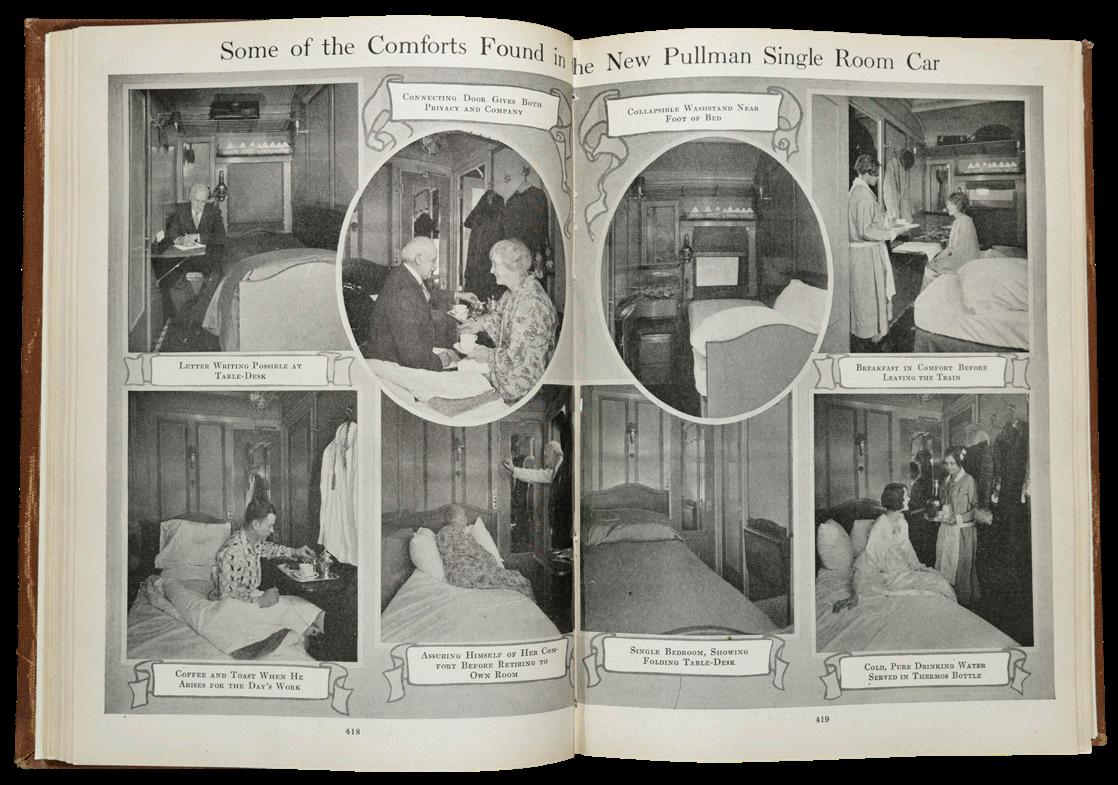

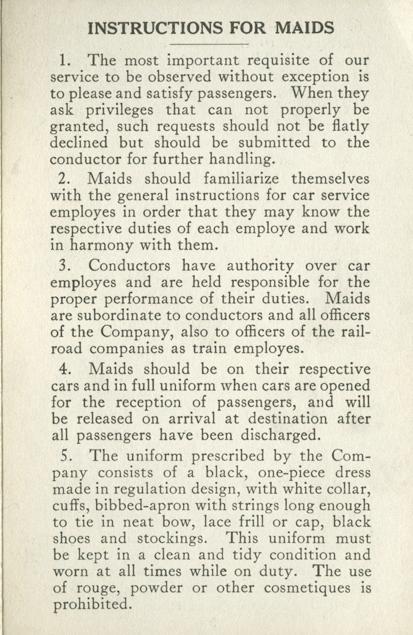

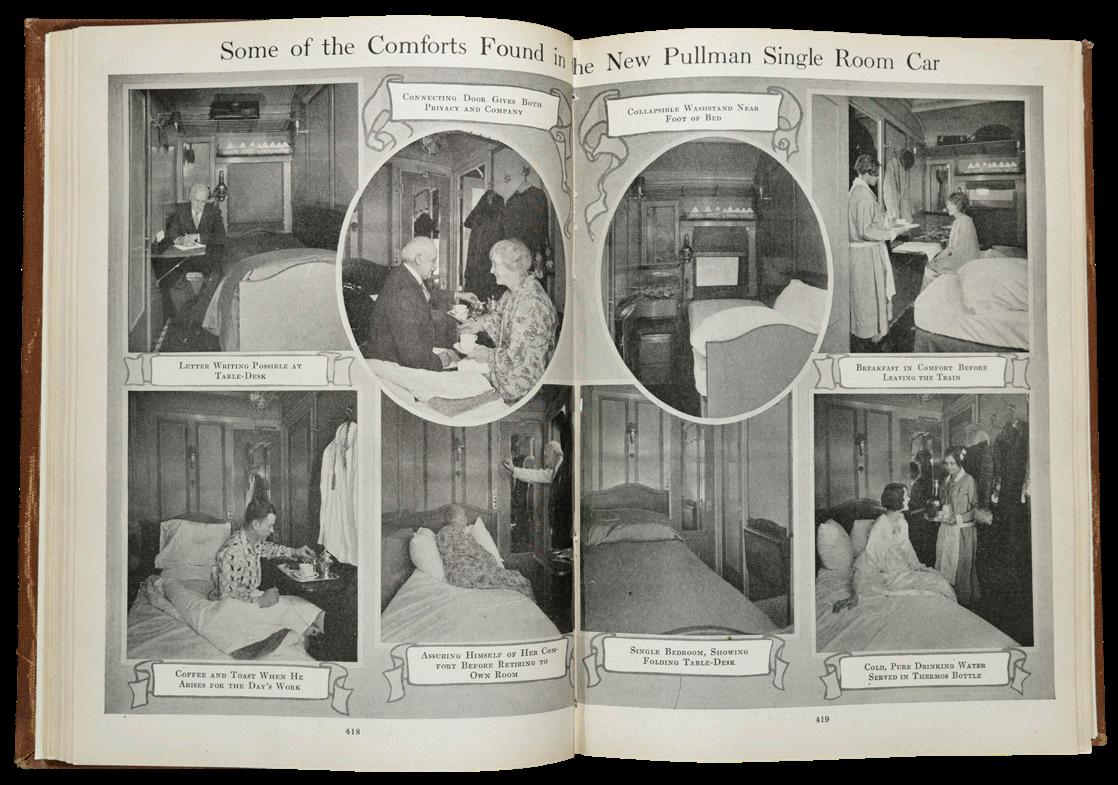

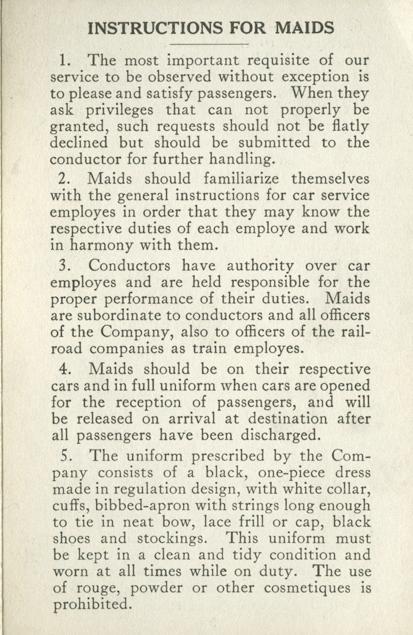

As a National Endowment for the Humanities / Lloyd Lewis Fellow in American History at the Newberry Library in 2015, Miriam Thaggert became interested in how African American women have experienced travel on trains. Combing through the library’s Pullman Company archives, she discovered that it wasn’t just Pullman porters who negotiated complex power dynamics on the rails; Pullman maids also reckoned with the social mores of class, race, and gender aboard the company’s famous sleeping cars.

Thaggert, an Associate Professor of English at the University of Buffalo, drew on her research at the Newberry to write her forthcoming book, Riding Jane Crow (University of Illinois Press, 2022). The book explores how the experiences of African American women travelers challenge the narratives of freedom and progress traditionally associated with trains. Thaggert also has curated a new exhibition, Handmaidens for Travelers, on view June 3 through September 16 in the Newberry’s Helen M. Hanson Gallery.

The Newberry Magazine recently interviewed Thaggert about her research and the significance of telling the stories of the Pullman Company maids.

FEATURE

21 Working on the Railroad

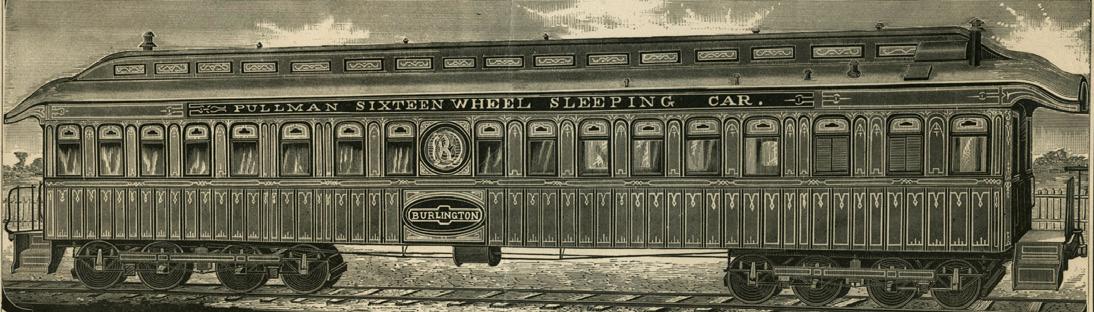

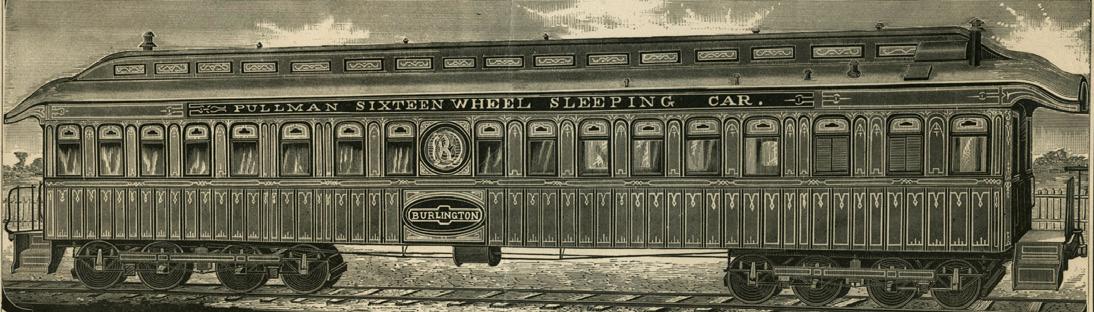

The Chicago, Burlington & Quincy railroad used Pulllman Sleeping Cars on their routes. This image detail was part of a promotional poster issued by the CB&Q railroad in the 1870s.

Newberry Magazine: How did you first become interested in the Pullman Company and the women who worked as maids for the railroad?

Miriam Thaggert: Riding Jane Crow began at the Newberry. I was looking for first-person stories about Pullman porters and came across a file that had the application of a woman applying to be a Pullman Company maid. I remember the moment so clearly because I literally stopped and asked myself: “The Pullman Company had maids?” I was surprised that I’d never heard of Pullman maids. I didn’t even know the position existed. I became really curious about what the maids’ experiences were like and that led me to raise other questions about Black women on the railroad and their perspectives of the American train: Did their experiences match the familiar narratives we tell about the train in American culture? How did their race and gender impact the way they were treated? One question led to another, and Riding Jane Crow is my way to answer some of these questions.

NM: What are the common narratives about the train in American culture? How do the experiences of Pullman maids either support or contradict those narratives?

MT: In the United States, the train is a symbol of American ingenuity and progress, a sign of technological dominance. The Pullman compartment can be seen as a form of American progress —it improved the long-distance traveler’s train ride experience. Similarly, the presence of Pullman porters and maids offered a feeling of enhanced leisure for the white Pullman passenger. Questions I ask in my book include: How does our understanding of the Pullman compartment space change when the experience of the maid is the center of the discussion? How does the Pullman car appear when the site of travel

leisure is based upon the Black woman’s labor? My research suggests that there were advantages and disadvantages to working as a maid on the Pullman car. On the one hand, it was a comparatively privileged occupation, much as it was for the porters. But there were challenges to being the only Black female Pullman employee within that space. Maids were accused of theft when passenger items went missing, for example; and, in the book, I briefly discuss an episode of harassment a maid experienced from a white conductor.

NM: Why is it important to tell the stories of Pullman maids?

MT: The stories about the Pullman porters have in some ways overshadowed the stories about the maids. This happened for a number of reasons, as I point out in Riding Jane Crow. There have always been more porters than maids in the Pullman Company, and the porters’ fight for better working conditions were usually framed in terms of “manhood rights.” But it’s important to know the maids’ experiences because the maids offer a unique perspective on that history and on African American labor.

NM: What role has the Newberry played in your research and what you’ve been able to discover about Pullman maids?

MT: The Newberry Library has been so important for my work. The space and the people I’ve met here have been very significant to my research and the book. First, the Pullman Archives is a great resource, for many purposes. Going through the very large Pullman Archives was somewhat daunting, so the fellowship I had at the Newberry enabled me to take my time in going through much of the archives. The book started in the fourth-floor reading room.

22 The Newberry Magazine | Spring / Summer 2022

A Pullman Company maid with Pullman porters. Hooks Brothers Photographers, Memphis, Tennessee. Photo courtesy of Dr. Earnestine Jenkins, Department of Art, University of Memphis.

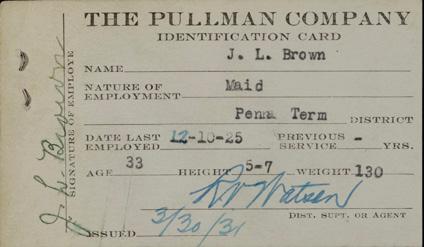

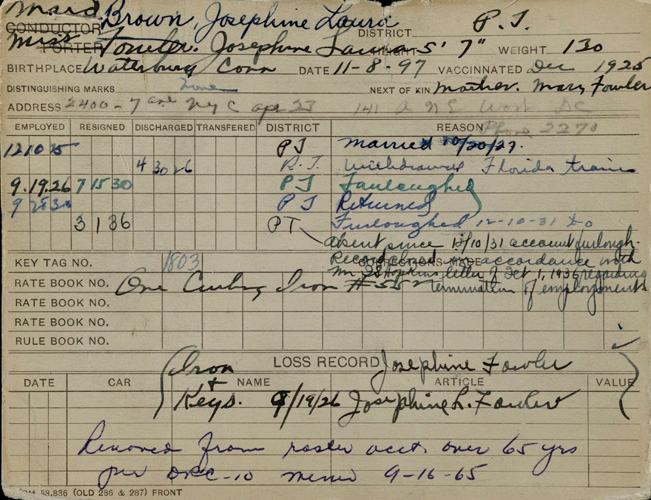

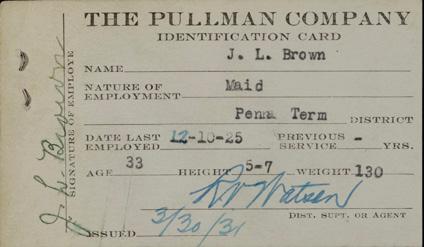

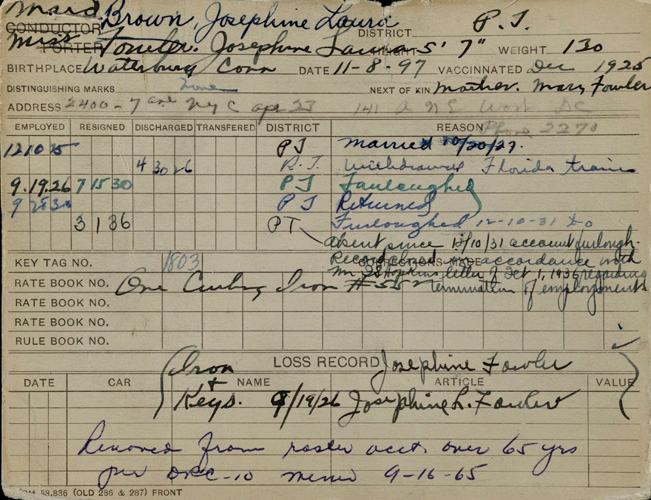

NM: You’re encountering personal information about these women in their employee records. How do you think about the balance between respecting their privacy and telling their stories?

MT: That is a very important question for me, and one that I was undecided about for a very long time. I wanted to let more people know about these women but how do I do that without exploiting their stories, their history? In order to get the full impact of the maids’ experiences, it would be necessary to tell certain stories about who they were and what their interactions with Pullman supervisors and Pullman passengers were like. But how do I do that respectfully, ethically? In the end, with the help of Newberry staff, I worked hard to ensure that very deeply private information was not disclosed in the exhibition.

NM: As you were doing research for the exhibition, did you find or learn anything that surprised you or challenged your expectations?

MT: I assumed that most of the maids would have been unmarried young adult women. In fact, the employee cards for the maids

indicate that many of the maids were or had been married, and some maids worked well until they were middle aged. While conducting my research, I was also surprised to learn that the Pullman Company had Asian American maids, primarily on the western train lines. Unfortunately, I did not locate a lot of info about these maids in my Newberry research.

NM: What has been your approach to curating the exhibition? Were there any special storytelling tactics you had to adopt while shaping the content into an exhibition, as opposed to the book?

MT: One important consideration was conservation—how fragile or how sturdy were the documents I wanted to use? The question about privacy was also raised. As a literature scholar, I’ve long been interested in narrative and how different narratives work. An exhibition requires strong visual skills, it requires telling a compelling historical narrative with primary documents and images. It was an exciting opportunity, and I loved it. I have to give my deep thanks to the Newberry’s archival, conservation, and exhibition teams.

23 Working on the Railroad

In the May 1924 issue of The Pullman News, an article about the humble origins of American railroad executives appears opposite photos promoting the service of Pullman Company maids and porters.

24 The Newberry Magazine | Spring / Summer 2022

The Newberry’s Pullman Company Archives contain employee applications and records for the women who worked as maids. From left to right: Behetherlon L. Glass, Nannie B. Crevin, Rosa L. Davis, Mae L. Miller, and Josephine L. Brown

NM: What do you hope visitors learn from the exhibition?

MT: I hope that both the people who already know about the maids and those who are learning about the maids for the first time will be able to find something surprising and engaging. I hope the exhibit encourages visitors to rethink their assumptions about train workers, their assumptions about the Pullman porter experience. As I mention in my book, the well-known Pullman porter narrative has its own sort of mobility in American and African American labor history. The story of the Pullman maid offers a different perspective on that familiar story.

Other exhibits dealing with the railroad may focus on the technology of the locomotive—the technological achievements that enabled the train to become such a dominant mode of transportation in the United States. I’m more interested in the social and the personal, the human aspect of working within or near the American train compartment. How did African American women workers navigate an enclosed space such as the Pullman car, a space that is simultaneously public and private? I hope the exhibition demonstrates that more human, personal element of train travel, as well as the Pullman compartment as a workspace for African American women.

25 Working on the Railroad

Above: Pullman maids figured prominently in advertisements touting the “comforts” found in Pullman cars. Left: Instructions for Pullman maids, 1925.

By LaDale Winling

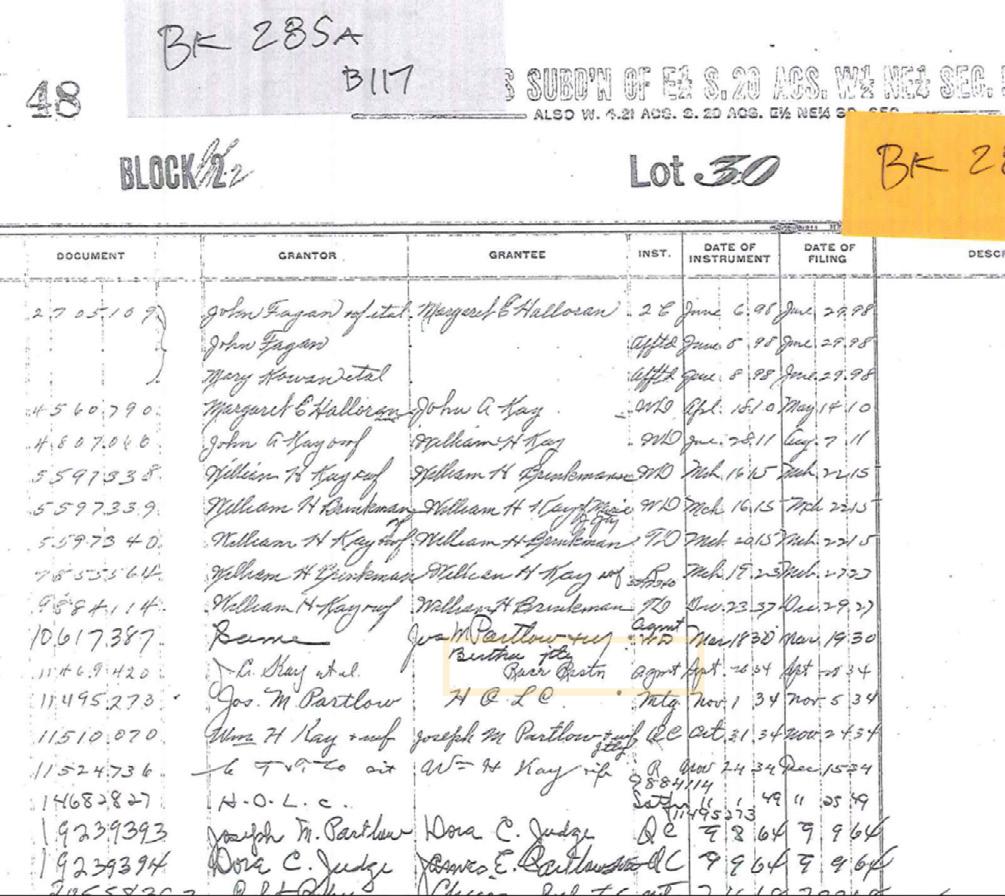

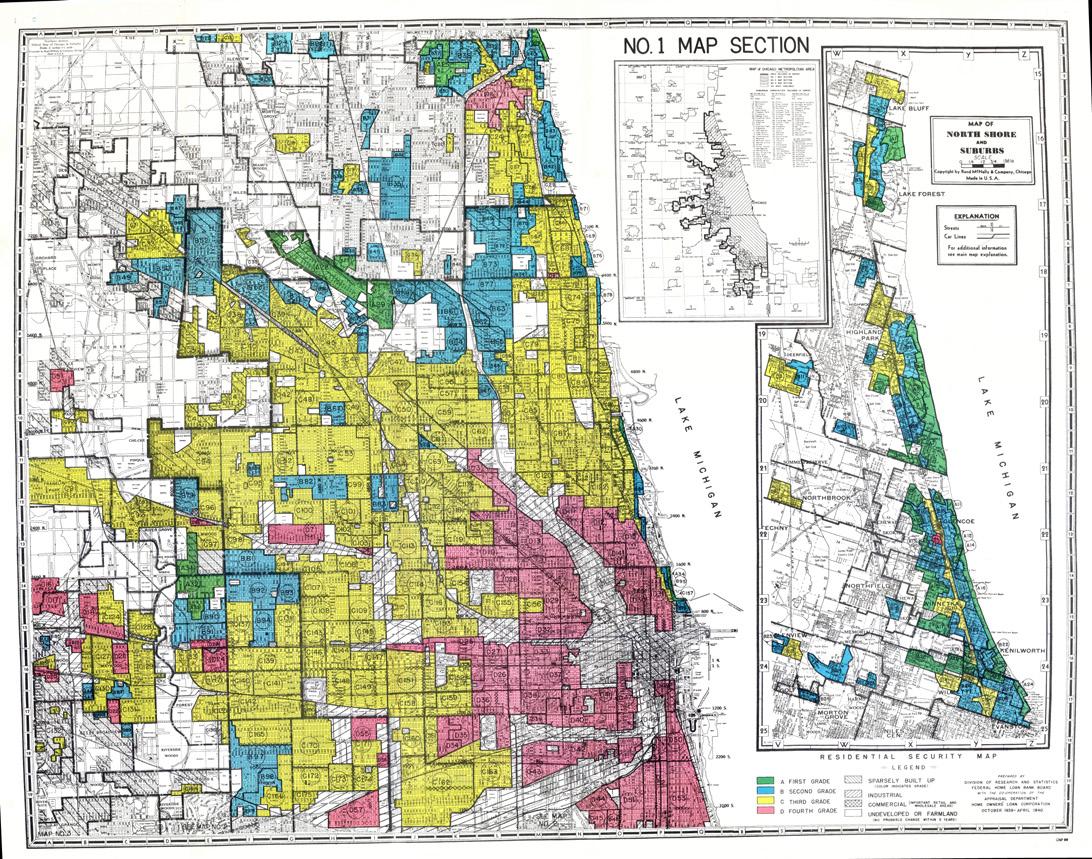

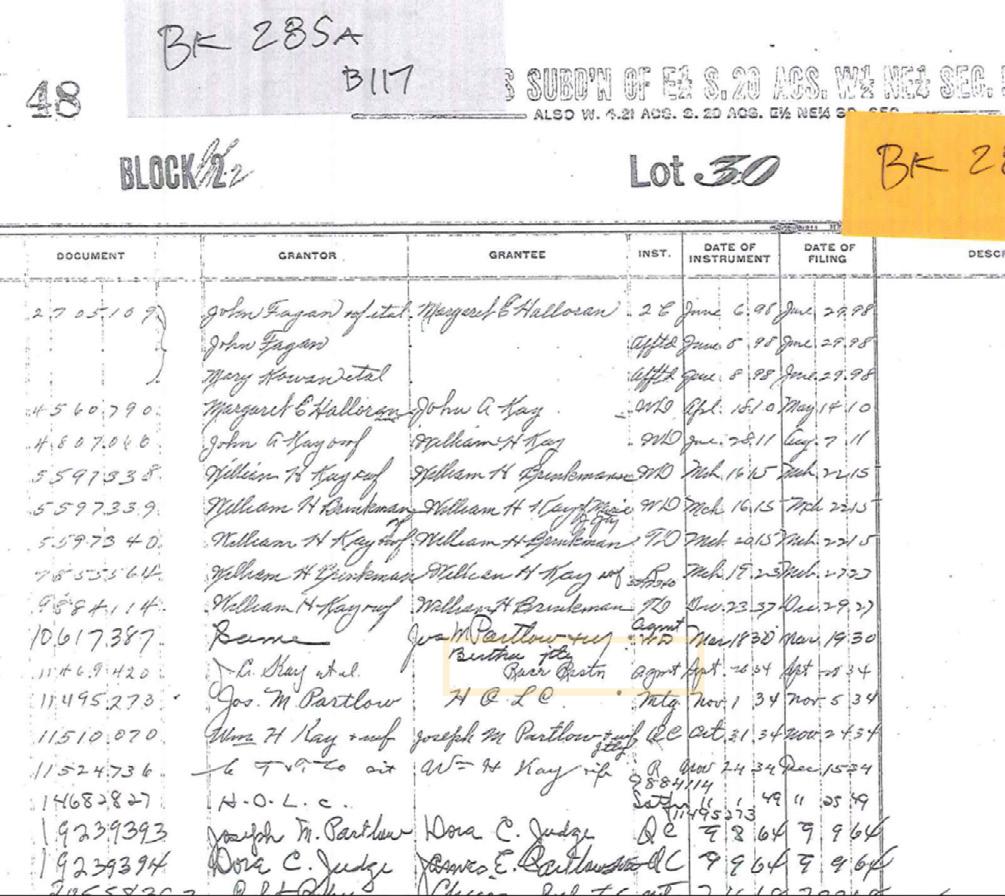

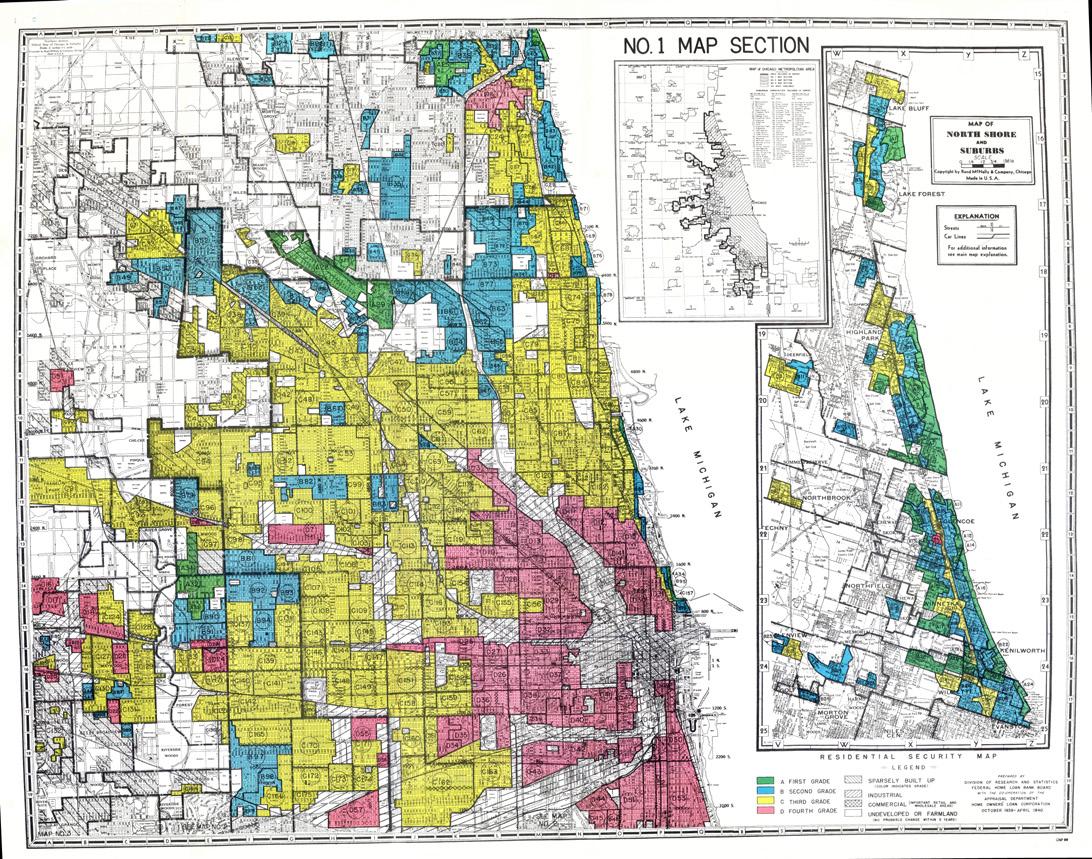

The Hunt for Restrictive Covenants in Cook County

No part of said premises shall be sold, given, conveyed, or leased to any negro or negroes . . .” These words were found in hundreds of racially restrictive covenants in Chicago, the legal agreements that barred white homeowners from selling their homes to African Americans and other people of color. First implemented during the Great Migration, when large numbers of African Americans moved from southern states to northern industrial cities like Chicago, restrictive covenants became a commonly used tool within the real estate industry to ensure segregated housing practices during the first half of the twentieth century.

As a Newberry fellow last year, I spent time researching restrictive covenants in Cook County. While I was at the Newberry, journalist Natalie Moore and WBEZ, Chicago’s National Public Radio affiliate, were embarking on an investigation of the lasting impact of housing segregation and the denial of homeownership opportunities to African Americans.

WBEZ issued a call to listeners asking if they could find racial restrictions in the documentation on their homes. Covenants were intended to “run with the land,” and could remain in effect for long periods of time. In some cases, deed documents included language prohibiting owners from selling to African American buyers. To this day, homeowners can sometimes find restrictive clauses, even on recent transactions.

In response to WBEZ’s investigation, people came forward after discovering that racially restrictive clauses were still technically attached to their homes—a troubling reminder of how the legacy of racist real estate practices continues to haunt Chicago and other American cities. I soon realized it was possible—through crowdsourcing and research—to locate every restrictive covenant in Cook County.

Pursuing such a major effort to study and collect racial covenants, it seemed imperative to preserve some of these

“ Professor LaDale Winling’s fellowship at the Newberry led to a citywide effort, in collaboration with local public radio affiliate WBEZ, encouraging Chicagoans to learn more about segregated housing practices and the histories of their own homes.

26 The Newberry Magazine | Spring / Summer 2022

FEATURE

Records of restrictive covenants can be found in the County Clerk’s Tract Department in Chicago City Hall.

documents and stories. Moore and I set up meetings between WBEZ archivists and Newberry archivists to make sure the documents could be shared and would be submitted in the appropriate digital format. The Newberry will now become the home for this digital civic archive.

The County Clerk’s Tract Department (formerly the Recorder of Deeds) has the feel of a bunker, with low ceilings and rows of racks for real estate transaction books. The books are hardbound, large, and hefty, at about ten pounds each. Lying open, they are about three feet wide by three feet tall. It is tedious work, paging through huge, heavy books to look on each sheet for the notation “race restrictions.”

For weeks, Natalie Moore, editor Alden Loury, and I worked at the City-County Building in Chicago to engage in this research. Moore and Loury learned the system for finding covenants and proved to be better researchers than I was. They knew the geography of Chicago like the back of their hands and recognized clues and documents that turned out to be covenants.

Meanwhile, I was doing archival research at the Newberry, looking into the historical roots of restrictive covenants.

After the 1919 race riot in Chicago, in which 38 Chicagoans (23 African Americans and 15 whites) died and more than 500 (some two-thirds African American) were injured, city business and political leaders worked to institutionalize racial segregation. The idea was to make separation of the races more efficient and less bloody—to prevent a violent, week-long conflict like the one in the “red summer.” Segregation by real estate practice, especially using racial covenants, was key to that plan.

Within the Newberry’s special collections, I found the papers of members of the Chicago Commission on Race Relations, which was formed to study the causes of the 1919 racial conflict. I also scoured microfilm of the NAACP papers, borrowed from another institution, which gave me a perspective on the national effort to battle racial segregation, and read many background sources about Chicago.

Chicago was central to the creation and widespread use of covenants because of organizations like the National Association of Real Estate Boards (NAREB), the American Institute of Real

27 Restrictive Covenants

A restrictive covenant (“race restn”) on a property is noted in a page from the Cook County land records index.

Estate Appraisers, the Society of Residential Appraisers, and the Institute for Research on Land Economics and Public Utilities at Northwestern University. All these organizations were established in the early part of the twentieth century and based in Chicago. The city, however, was also ground zero for the battle against racial covenants because of attorneys like Earl Dickerson and Truman Gibson, Jr., and figures like Harry Pace and Carl Hansberry.

In the 1930s, covenants seemed to have a strong legal foundation and support from the newly created Home Owners’ Loan Corporation and Federal Housing Administration. Building on racial covenants, these two agencies engaged in redlining, the practice of limiting majority-Black neighborhoods’ access to federally insured mortgages. Lenders, appraisers, and federal officials expected neighborhood stability where there were covenants, and they directed federal subsidies like mortgage guarantees to those neighborhoods.

Harry Pace, an insurance executive, and Carl Hansberry, a real estate investor, teamed up to challenge one particular covenant on the city’s South Side. They were both integrationists who believed they and other African Americans should be able to live in the neighborhoods of their choosing if they could afford the houses. The covenant Pace and Hansberry decided to challenge covered the Woodlawn neighborhood and had been filed in the late 1920s. Though its covenant was in effect, in fact it had not had enough signatures to make it valid.

Truman Gibson, Jr., a young Black lawyer, spent weeks researching property documents in the City-County Building in 1937, just as the WBEZ team and I were doing in 2021. Gibson would later become manager for heavyweight boxing champion Joe Louis. Early in his career, however, he had the least seniority at his firm and had to do the tedious work of paging through index books to find the property owners in the

28 The Newberry Magazine | Spring / Summer 2022

On maps created between 1935 and 1940, the federal government’s Home Owners’ Loan Corporation assessed the risk of lending mortgages to people living in different neighborhoods of a city. In the HOLC’s color-coded system, areas in green were deemed the least risky for banks and mortage lenders, while areas in red were judged to present the highest risk.

boundaries of the covenant, then had to call up the individual documents. The memory stayed with him. Seventy years later, Gibson wrote in his memoir, Breaking Down Barriers , “At the recorder’s office, I hunted up the deeds to the properties and compared the signatures on them to those on the covenant. It was a laborious, tiresome, boring task. Squinting to make out the signatures was hard on my eyes; reams of legal papers cramped my hand.”

Gibson found what he was looking for, however. “The payoff was big. [O]nly 54 percent of the property owners actually had signed the covenant.” It was still no easy case. Hansberry’s legal team lost in the Cook County Superior Court and the Illinois Supreme Court, but appealed to the US Supreme Court. In Washington, DC, in the fall of 1940, Earl Dickerson and Truman Gibson, Jr. presented their data and made the case that covenants were fundamentally unconstitutional at the same time they argued that the one covenant in question was not valid.

The Supreme Court ruled in their favor in Hansberry v. Lee. The court agreed with Dickerson’s team on the second point, about the specific covenant in Woodlawn, but ignored them on the first point, about covenants generally. Carl Hansberry’s daughter, Lorraine Hansberry, had been berated and harassed on her way to school while they lived in their house at 6140 S. Rhodes. She would draw on these experiences nearly twenty years later in her 1959 play A Raisin in the Sun.

The victory before the Supreme Court illustrated that covenants were not invincible. They could be beaten in court if you knew their weakness. The effort by the Chicago attorneys invigorated the NAACP’s efforts in the campaign against racial segregation and housing discrimination, led by Thurgood Marshall and Charles Hamilton Houston. They would build from the Chicagoans’ victory in 1940 to argue another case in 1948, Shelley v. Kraemer, in which the Supreme Court ruled that racial covenants were unenforceable.

After a summer of research and an autumn of tweaking and fact-checking, Natalie Moore’s reporting for WBEZ and NPR began to air in November 2021, bringing our collaboration to a close. But the research continues. Since autumn, a team of volunteers has been meeting at the Clerk’s office to locate covenants; to date, we have found more than one hundred.

In the 1930s and the 1940s, few historians were interested in studying racial covenants—it was a contemporary civil rights issue the NAACP was trying to remedy, not one that many historians considered in their work. Now, scholars and journalists, with the support of the Newberry, are working to recapture and document this important aspect of Chicago history and civil rights history. My research fellowship gave me a deeper appreciation of what it means to grapple with documents of exclusion. And it provided the opportunity to complete that research on covenants started by Truman Gibson in Cook County, nearly ninety years ago.

29 Restrictive Covenants

Attorneys Earl Dickerson (above) and Truman Gibson (right). Photo of Gibson courtesy of the Library of Congress.

The Recent Past

Ira Glass and This American Life Honored with Newberry Library Award

On May 15, several hundred friends of the Newberry gathered at the Newberry Library Award Celebration to honor Ira Glass. Glass is the creator, producer, and host of the public radio program This American Life . Since debuting on Chicago Public Radio in 1995, This American Life has won seven Peabody Awards and the first Pulitzer Prize for audio journalism.

“Throughout his career, Ira Glass has helped millions of listeners better understand the human condition through riveting storytelling based on extensive research,” said Newberry President Daniel Greene. “He carries on the tradition of American journalism while pushing it in new and exciting directions. We’re thrilled to honor him with the Newberry Library Award this year.”

In addition to hearing a conversation between Glass and Greene, guests enjoyed the opportunity to learn more about the Newberry’s collections and educational programs. “The evening is also a celebration of the Newberry itself,” said event chair and Newberry Trustee Celine Fitzgerald. “We encouraged guests to meet Newberry staff, learn how we use our collections in high school classrooms, and engage with the many digital resources the Newberry offers.”

The Award Celebration raises important funds for the Newberry’s collections and programs.

30 The Newberry Magazine | Spring / Summer 2022

Celine Fitzgerald, Newberry Trustee and Chair of the 2022 Newberry Library Award Celebration

Celine Fitzgerald, Ira Glass, and Newberry President and Librarian Daniel Greene

31 Recent Past

Guests enjoy the conversation between Ira Glass and Daniel Greene.

After receiving the 2022 Newberry Library Award, Ira Glass reflected on his career in radio and podcasting with Daniel Greene.

The Recent Past

A Reading by Louise Erdrich

On December 2, 2021, Pulitzer Prize-winning author Louise Erdrich joined Newberry fellow Kelly Wisecup for a virtual conversation about Erdrich’s latest novel, The Sentence. An enrolled member of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa, Erdrich is the author of several award-winning novels, including The Round House, Love Medicine, and LaRose. She is also the owner of Birchbark Books, a small independent bookstore in Minneapolis.

Following a beautiful introduction by poet Mark Turcotte, who is also a member of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa, Erdrich read an excerpt from The Sentence, a novel about a ghost who haunts a bookstore. Wisecup and Erdrich explored the powerful themes of the text, including what it means to grieve in the context of tremendous loss brought on by COVID-19. Erdrich and Wisecup also focused on the significance of place, the flourishing landscape of Indigenous authors, and the novel’s overarching question of How much do we owe the dead? After answering questions from viewers, Erdrich ended with a few lines of her favorite poems by Sylvia Plath and Langston Hughes.

A Conversation with Tiya Miles and Megan Sweeney

Author Tiya Miles virtually joined the Newberry on February 3 for a conversation about her new National Book Award-winning book, All That She Carried: The Journey of Ashley’s Sack, a Black Family Keepsake. Miles, Professor of History at Harvard University, discussed the power of seemingly simple historical artifacts with Megan Sweeney, Arthur F. Thurneau Associate Professor of English at University of Michigan.

Miles and Sweeney started the program with readings from their new books, both of which focus on the crucial roles that material objects play in helping us understand the past and reckon with our history. They also described how the tangibility of objects—in this case, articles of clothing—can intimately connect us to all the people who imbued them with meaning.

Miles noted that her research started with a simple cotton sack that was held and passed down for generations by the women of a single African American family. In a powerful conversation, Miles and Sweeney went on to discuss how this single cotton sack opened a broader story—as Miles put it, a story “of Black women’s lives, about African American enslavement, African American resistance and resilience, and women’s lives in relation to fabrics.”

This program was held as part of the Conversations at the Newberry series, sponsored by Sue and Melvin Gray.

Shakespeare in Type with Claire Bourne