I dedicate this work to all the women in my life who have inspired my path with their resilience and creativity. In a very special way, I thank my mother, my biggest inspiration, whose strength and vision have guided me relentlessly. To my grandmothers, whose hands have woven not only threads in embroidery but also verses in poetry and melodies in song, crafting spaces of freedom, liberation, and self-expression.Their artistic spirits have shown me the importance of having a room of one’s own to dream, to think, and to create. This thesis is not only a reflection of my efforts but a celebration of theirs.

Arianna Deane

Alan Ruiz

Maria Linares Trelles

Kim Ackert

Lucero Zuñiga

Dinorah Castañeda

Julieta Hernández

Vera Keiter

Raquel Espinoza

Emily Erikson

Dana Barnes

Tatiana Konstantinidi

Ben Goldner

Alfred Zollinger

Santiago Ruiz

Manuel Lastiri

Every aspect and detail of life holds the potential for ritual, thus even the most banal everyday moments and objects, guided by design choices, contain the chance for profound intervention. Design is a transformative tool capable of converting challenges into empowering opportunities and creating meaningful connections between people. My design vision revolves around crafting spaces that seamlessly integrate these everyday elements into coherent spatial narratives, placing the human experience at the core, emphasizing quality, accessibility, and the importance of authenticity in every aspect of life.

I came into design, because of a genuine desire to connect with people. This collided with my deep curiosity about places, objects, and design history, motivates my commitment to listen to people’s stories more closely to extend better care to others. Design is an act of care, or at least it should be; it can recognize the value in everyone and everything; it mediates our relationships,

work, communication, health, communities, and sense of self. As a designer I seek to comprehend and elevate the spaces and narratives surrounding us. To design is to care. Design is a collection of deliberate and reasoned choices that impact people’s lives; design is an ongoing process of self-discovery, learning, making mistakes, learning more, and trying again.

Recognizing that change is the only constant in both design and life itself, I find that adaptability, empathy, profound responsibility, and commitment guide my design philosophy. As a Mexican woman designer and creative, I want to cultivate a practice that celebrates the exchange of expertise and ideas and the richness of multiculturalism. I dedicate my practice as a designer to reshaping spaces, experiences, and narratives to connect with people on a profound level, with a vision that transcends boundaries and celebrates the dynamic nature of design.

Constellation Map

Feminist design: For this research I refer to feminist design as design approaches that are informed by feminist principles and aim to promote not only gender equality but also challenge traditional norms. It is a guiding framework capable of navigating and reshaping prevailing power structures, particularly those influencing design practices and determining their impact on people’s lives. It encompasses various aspects of design including inclusivity, intersectionality, representation, accessibility, sustainability, participation, care, and empowerment.

Design: In the context of this research, “Design” is regarded as a mediator of relationships with others, our bodies, and the surrounding space. A powerful tool that can challenge and reshape societal norms. Its purpose is to actively contribute to the creation of spaces that are not only inclusive but also equitable. A catalyst for social change, actively working to break down barriers and reconfigure existing structures that may perpetuate inequality.

Care: Social capacity and activities involving the nourishment of all that is necessary for the welfare and flourishing of life dependant upon our individual and common ability to provide the political, social, material and emotional conditions that allow people to thrive.

Bodily Care: Practices associated with nourishing the body. To comfort and protect the body while navigating through urban environments.

Vulnerable bodies: The bodies aliving in urban contexts in need of care, safety, healing, and nourishment. Bodies that often rely on the care of other female bodies to engage with hostile urban environments.

Vulnerability: A state characterized by the absence of essential infrastructures of care upon which our body and mind depend to thrive and heal in urban environments. It is a condition marked by the lack of necessary support systems, leaving individuals without the resources for their holistic well-being. Vulnerability in this context is a sustained state where the usual sources of support, physical, emotional, or societal, are compromised or insufficient.

Objects of care: Refers to concrete, tangible entities, including physical artifacts, wearable items, or spatial interventions. These objects play a crucial role in enhancing and facilitating our bodily experiences within a given space and influencing our connections with others in our immediate surroundings. These objects are purposefully designed

1 The Care Collective, The Care Manifesto: The Politics of Interdependence (London, UK: Verso, 2021).

to contribute to individuals’ well-being, comfort, and safety, acting as conduits mediating our relationship with the physical environment and the people sharing that space.

Softness: In the context of this research, “softness” is used to describe an attribute that extends beyond its association with the human body to encompass both spatial dimensions and the dynamic capacity of design practices. It represents a tactile quality and an intrinsic ability to adapt, change, transform, and redefine itself. It reflects the ability of design strategies and practices to remain flexible and responsive, adapting to evolving needs and circumstances. It implies a malleability and resilience that goes beyond the rigid constraints of conventional structures, allowing for a more nuanced and empathetic approach to both the physical environment and the experiences of individuals within it.

Performative care: Making, creating, participating in everyday activities like cooking, sewing, writing, and more, as acts of care. Inspiring through the act of making and crafting to provoke thought and action.

support systems, and chosen families, as well as the tenderness of our bodies and our modes of speaking.2

Radical softness: Boundless acts of resistance, a practice of vulnerability, the result of the tenderness of our friendships, 2 Be Oakley, Radical Softness As a Boundless Form of Resistance Sixth Edition ( Richmond, VA: GenderFail Press, 2020), 24.

Cities are complex and dynamic networks of social, cultural, economic, and physical elements that shape and perpetuate gender dynamics, norms, and spatial inequalities. Public infrastructure, exemplified by the New York City subway system, can perpetuate gender inequality, impacting access to resources and opportunities, as well as shaping women’s interactions with and perceptions of urban environments. This research explores how interior design can facilitate dialogue and empowerment for vulnerable bodies through infrastructures of care. By framing design as an everyday practice and a political act of resistance, this project aims to illuminate the potential of public interiors to promote inclusivity and empowerment within urban landscapes.

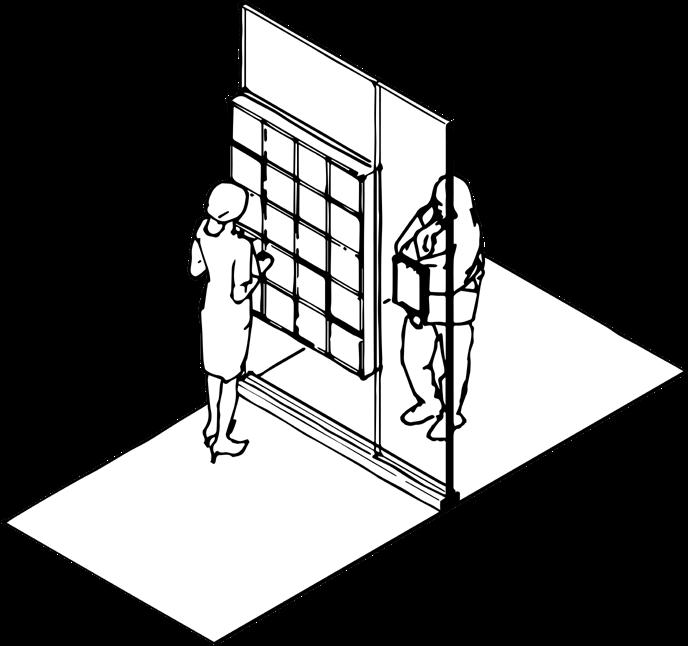

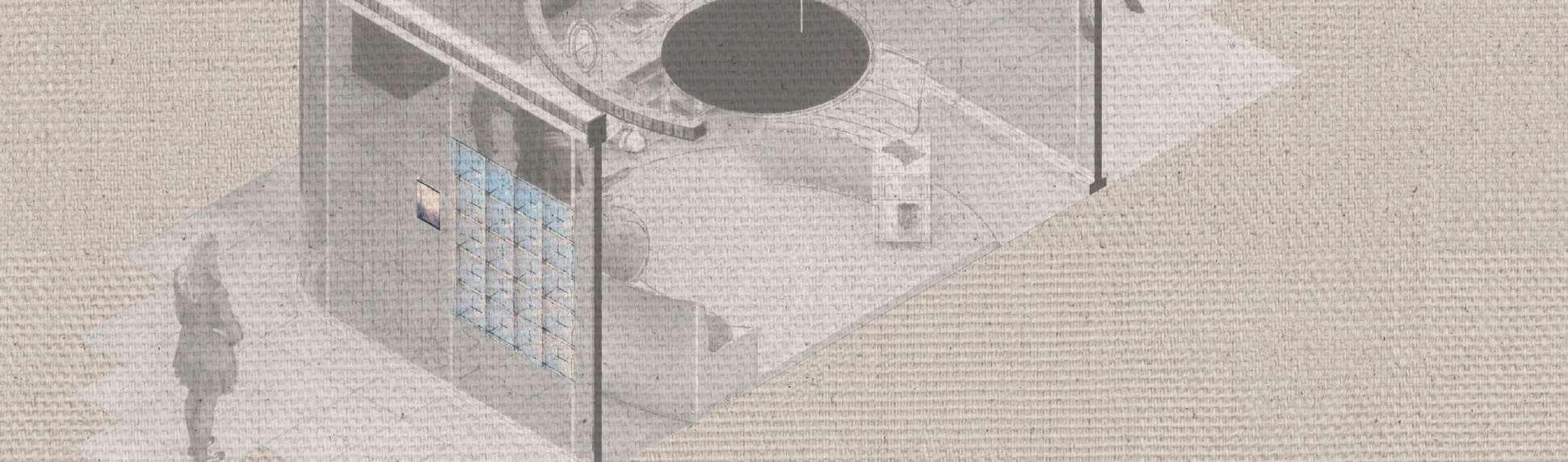

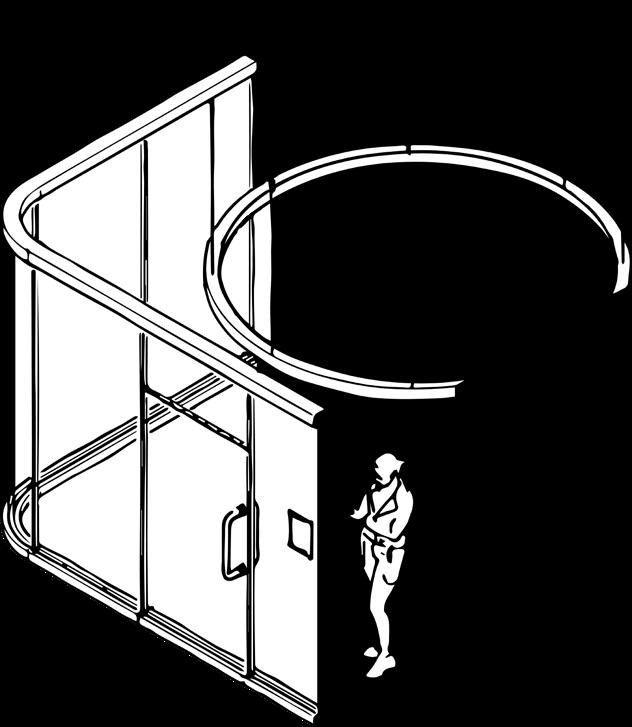

Interior Dialogues: Envisioning Spaces of Resistance raises awareness of women’s experiences in public spaces by collecting and visualizing their personal narratives within care infrastructures. Through this project, societal norms are challenged, and women are empowered

to assert their agency within both public spaces and domestic environments. Introducing a new typology within the New York subway system, a 200-squarefoot pavilion located on the mezzanine level of Union Square station, this freestanding glass kiosk offers heightened visibility to commuters from all angles. By reimagining public interiors as sites of empowerment and inclusivity, this project aims to contribute to a collective narrative of resistance, recognizing the power of sharing women’s stories as a means of challenging existing inequalities.

The theoretical framework of this thesis is anchored in the transformative potential of design, regarded not only as an everyday practice but also as a political act of resistance and a strategic tool for social change. Central to this perspective is Allison Place’s assertion that “Design provides the medium for putting feminist theory into action, and feminism provides a framework for making that action more equitable and beneficial to the lived experiences of real people.” This approach positions design as a powerful catalyst in the advocacy for gender equity, particularly within the public urban landscapes. By leveraging feminist principles, the project aims to redefine public spaces—specifically the New York City subway system—to promote inclusivity, facilitate empowerment, and foster dialogue among vulnerable populations. This framework integrates diverse theoretical insights that collectively emphasize the significance of care, vulnerability, and social interdependence, proposing a radical reimagining of urban environments as sites of collective resistance and empowerment.

Vulnerability and Dependency on Infrastructure:

Judith Butler’s perspective on vulnerability emphasizes the inherent dependency of bodies on societal infrastructures for a livable life. In the context of urban design, particularly within the New York

City subway system, this dependency highlights how infrastructural failures disproportionately affect vulnerable populations, such as women. Butler’s analysis suggests that when infrastructures fail to support these populations, it leads to a life devoid of essential supports, thereby exacerbating existing inequalities.

Social Dependency and Bodily Vulnerability:

Kathleen Lennon’s work further explores the embodiment of social dependency, emphasizing how individuals become vulnerable not only through their physical bodies but also via their social and material environments. This vulnerability is particularly pronounced in gendered experiences within public spaces, where design can either mitigate or exacerbate exposure to social inequities and environmental harms.

Feminism and Design as Tools for Equity:

Allison Place introduces a pivotal intersection of feminist theory and design practice, positing that design is both a method and a medium through which feminist principles can be actualized to create more equitable spaces. In the thesis, design is leveraged as a political act and a practical tool to reconfigure public interiors, such as the subway system, to foster inclusivity and

empowerment for women, transforming everyday interactions into opportunities for resistance and dialogue.

Topophilia and Environmental Bonding:

Yi-Fu Tuan’s concept of topophilia, or the emotional connections that people form with places, underscores the importance of designing spaces that resonate positively with their users. In the urban context, enhancing the subway environment to foster a sense of belonging and positive engagement can transform these public spaces into havens of safety and personal connection, particularly for those who feel marginalized or at risk.

Ethics of Care:

Joan Tronto’s ethics of care introduces three critical aspects of care—caring for, about, and with—which can be foundational for designing public spaces. These aspects demand a rethinking of care from a multidimensional perspective that includes recognizing needs, empathizing with users, and engaging with them in a participative and reciprocal design process. This framework

emphasizes the relational and reciprocal nature of care, crucial for creating spaces that are truly inclusive and supportive.

Politics of Interdependence and Universal Care:

The Care Collective’s manifesto on interdependence and universal care challenges the neoliberal constructs that often underpin public infrastructure projects, advocating instead for a caring economy and social structure. By integrating these principles into urban design, the thesis aligns with broader calls for a societal revaluation of care, asserting that care-driven design is essential not just for individual well-being but also for societal progress.

Site social dynamics, urban life, and collective identity but also offers a meaningful site through which to address deeply rooted social issues via design interventions. The subway serves as a complex nexus where diverse individuals converge, offering a rich tapestry of experiences and interactions. However, it is also a space where vulnerability can be heightened, exposing underlying tensions and inequalities. Embracing bell hooks’ ideas on marginality as a site of resistance and creativity, we can understand the subway interior as a microcosm of society’s margins, where individuals often find themselves positioned due to factors such as race, gender, and class. Rather

In New York City, the subway system holds unique significance, making it an even more compelling case study for understanding and illuminating the importance of public interiors in the urban experience of women. Often referred to as “cities inside a city” the subway encapsulates the diversity, vibrancy, and complexity of New York City itself. Its relevance transcends mere transportation, as it serves as a vital artery connecting the city’s five boroughs and diverse communities. Within the confines of a subway car, individuals

from all walks of life coexist, transcending social boundaries and fostering a sense of shared experience. The subway embodies the essence of New York’s cosmopolitan identity, where everyday commuters converge in a microcosm of the city’s dynamic culture. This amalgamation of people reflects the true essence of New York City—a melting pot of cultures, ideas, and aspirations.

Studying subway interiors in the context of New York City not only provides valuable insights into the city’s

1 Hooks, Bell. “CHOOSING THE MARGIN AS A SPACE OF RADICAL OPENNESS.”

Framework: The Journal of Cinema and Media, no. 36 (1989): 206. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44111660.

than viewing marginality solely through a lens of weakness or victimhood, hooks encourages us to recognize its potential as a space of radical openness, where alternative ways of thinking and being can flourish. In this context, subway interiors become not only spaces of transit but also arenas for challenging and reimagining social norms and power structures, offering opportunities for design interventions that promote inclusivity, equity, and social justice.

For the initial phase of my thesis project, I focused on studying the interior of a subway car, recognizing its unique mix of elements and the significant influence of time within its confined space. This exploration provided insights into the dynamics of such spaces, which is just one of the many public interiors that exist within the broader public transport system. Understanding the scale and direct relationship of these moving containers to the human body, as well as their role in our daily lives, guided my decision to further refine my project’s site to the mezzanine level of Union Square subway station.

The Union Square - 14 Street Subway Station, situated at the crossroads of Broadway, 4 Avenue, and East 14th Street, facilitates a complex exchange below ground among three subway lines. Its circulation plan includes multiple entrances, mezzanines, and connecting passageways. My design intervention is located precisely within this station, at a passageway linking a 480-foot long mezzanine, which ramps down from a control area on the north

(16th Street) to another control area on the south. This site lies at the heart of a significant transportation hub with historical, cultural, commercial, and communal importance in the city fabric of New York.

Public interiors refer to the larger public indoor-outdoor spaces that are accessible to the public, such as lobbies, atriums, parks and fountains, transportation facilities, and gardens. These spaces are defined and redefined again by bodies, objects, furniture, and other factors as individuals interact within them. One basic hope for these places is that they have been designed to create a welcoming and comfortable environment for visitors. This may include features like seating areas, art, proper lighting, and the intention behind the public access of these spaces is revealed precisely as they are utilized by the public. According to Martin Harteveld, public interiors are considered public spaces only when they are accessible to and acknowledge the knowledge and needs of a community. Unlike private homes, these spaces are open and inclusive, extending an invitation to the general public to use and benefit from them. Public interiors play a crucial role in shaping the urban experience, as they provide opportunities for social interaction and community engagement.

The site for this research project is characterized by specific conditions that delineate its boundaries. In the context of this research, public interiors are characterized by a set of spatial and emotional conditions. These interiors are profoundly embedded in the collective memory, they are integrated into the fabric

of everyday city life. Being accessible spaces that are open to everyone, they function as crucial nodes within the urban landscape. Nevertheless, the considerable number of people who frequent these areas daily induces a tangible feeling of discomfort among the users. This discomfort often manifests due to the inevitable proximity to others, resulting in intensified sensory perceptions and a heightened awareness of one’s environment. Most importantly, these spaces are marked by time and periods of waiting. This temporal aspect is intrinsic to their functionality, shaping the experiences of those who traverse their thresholds.

In essence, public interiors are dynamic spaces where memory, public

access, discomfort, sensory engagement, proximity, and temporality converge to shape the lived experiences of their occupants. These manifest in diverse forms within urban contexts, coexisting simultaneously. Examples include crosswalks, public elevators, public seating, restrooms, subway platforms and subway interiors just to mention a few. For this project I focus particularly on the New York City subway system.

Methodology

I believe that design is not a linear process; rather, it morphs and transforms in diverse directions and shapes. This diagram reflects my own design methodology—a journey marked by messiness, confusion, and time. It is a collection of deliberate and reasoned choices, an ongoing process of self-discovery, making, undoing, and learning. My design process began with identifying the issue I aimed to address and engaging in conversations with various stakeholders, including teachers, colleagues, peers from diverse disciplines, and family members, each bringing their unique social, cultural, and generational perspectives to the table.

Through a series of experiences and making processes, I’ve developed a set of design strategies that have shaped Interior Dialogue’s methodologies. Craft is my medium of expression allowing me to explore various tactile and soft techniques such as sewing, embroidering, and quilting. I view craft as a tool for activism, enabling me to advocate for social awareness and change through creative means. Embroidery holds a significant role, serving as a powerful means of record-keeping and journaling, transforming everyday experiences

into meaningful rituals. By delving into methods like embroidery and considering their historical, social, gendered, and economic implications, I have been able to navigate the direction of this multilayered project.

Collective Participation has been a cornerstone of my research. I facilitated a series of collective workshops and activities involving 25-30 womenidentified graduate students. Together, we reflected on our urban experiences and perceptions, aiming to translate these stories into a coherent visual language. As part of this methodology, I invited participants to engage in a brief worksheet activity, asking them to recall and sketch their most recurrent routes while focusing on the emotions and feelings associated with their journeys. These workshops naturally created spaces for reflection and spontaneous dialogue amidst the hustle of school days, unveiling potential elements for the design program within these infrastructures of care.

Embroidery, a historically feminist practice tied to the domestic sphere, provided women like my grandmothers with moments of freedom, liberation, and

Instructions

1. Close your eyes and take a moment to clear you mind.

2. Try to recall one of your most ecurrent routes. It could be your commute home from school a regular visit to a friend your oute o the grocery store, or any other familiar journey.

3. Using the symbols provided sketch a representation of this route inside the box. You don't need to worry about creating a perfect map; the focus is on conveying your emotions and eelings associated with this oute

4. If there are emotions not listed above, please write them down

5. If you eel comfortable sign you name at the bottom o your sketch and notes

6. Include the usual time of your journey. (ie. 9:00am)

7. Once you have completed the diagram, turn the page and continue with the remaining steps.

example:

self-expression. Such activities carved out spaces in their busy lives, allowing them time to dedicate to themselves. This echoes Virginia Woolf’s thesis in *A Room of One’s Own*, emphasizing the necessity for women to have personal spaces to develop creatively, mentally, and professionally. It is for this reason that I sought to reintegrate this process of making into the narrative of the project, stitching together tradition and the needs of contemporary women.

Each entry was translated into embroidered pieces, infusing a tangible and intimate essence into the narratives shared by participants. A Journey of Discovery and Connection emerged as I shared the progress of my thesis with my grandmother during a trip home to Mexico. Seeking her advice on how to enhance my embroidery efficiency, she not only offered help but also joined me in the process. As we embroidered together, she shared her own life stories, sparking conversations on topics I never anticipated we’d discuss. This experience transformed embroidery for me; it became more than just a method for documenting and expressing personal narratives. It evolved into a powerful medium for fostering meaningful dialogues and building empathy among women, connecting us through shared experiences and reflections. This process provided insight into

the direct relationships between public spaces, infrastructures, the human body, and our perceptions of these spaces. By the end of this process, I had a tangible collection of these embroidered pieces, each a testament to the interconnectedness of our personal and shared journeys.

Collaboration: These images showcase workshops with women-identified students at Parsons, where participants were invited to engage in a worksheet activity. They recalled and sketched their most frequent routes, focusing on the emotions and feelings associated with their journeys. These workshops fostered spaces for reflection and spontaneous dialogue, providing a respite from the busy school days.

“Threaded Journeys” unites the voices women identified graduate students at Parsons in a tapestry of urban narratives. This collaborative exhibition explores our diverse experiences navigating city life, captured through the lens of craft. The quilt project, employs acetone transfer techniques to blend public interiors with personal insights, encouraging community interaction and annotation. This endeavor is not just about creating beautiful pieces—it’s a movement towards social awareness, using the threads of activism to weave stories of authenticity, healing, and empowerment.

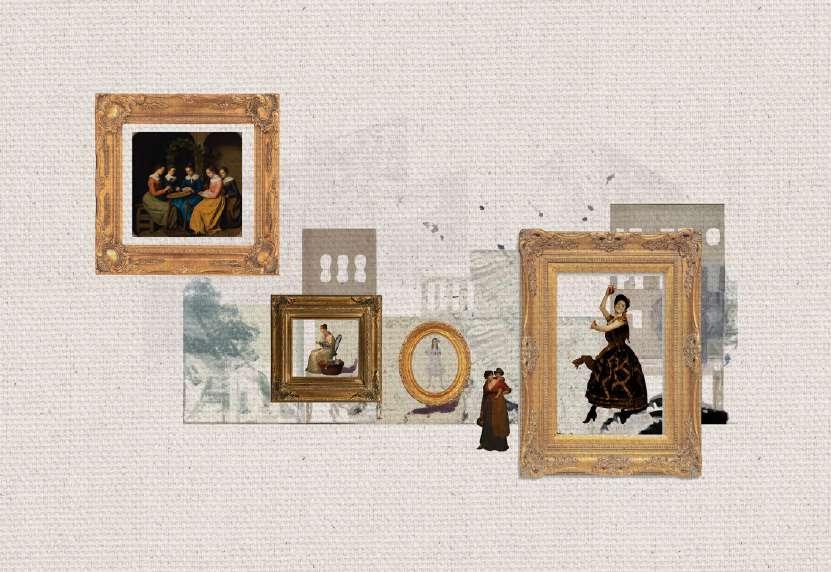

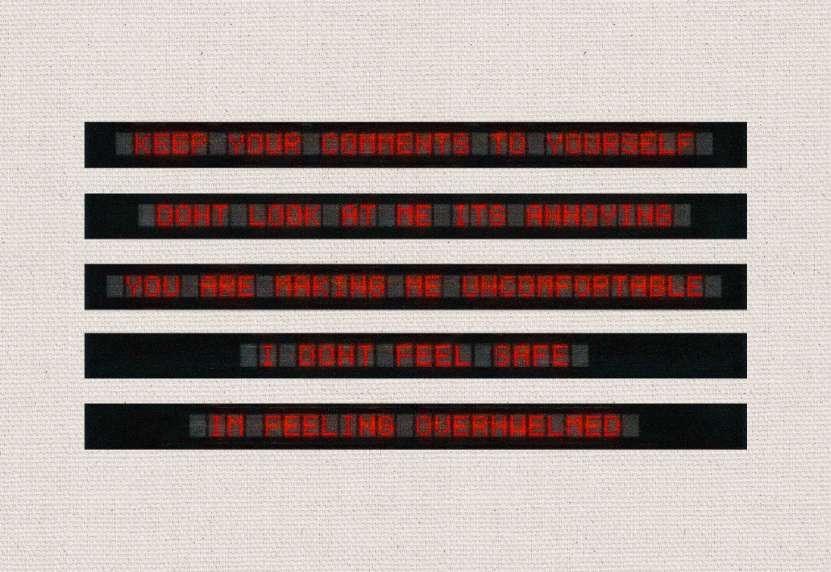

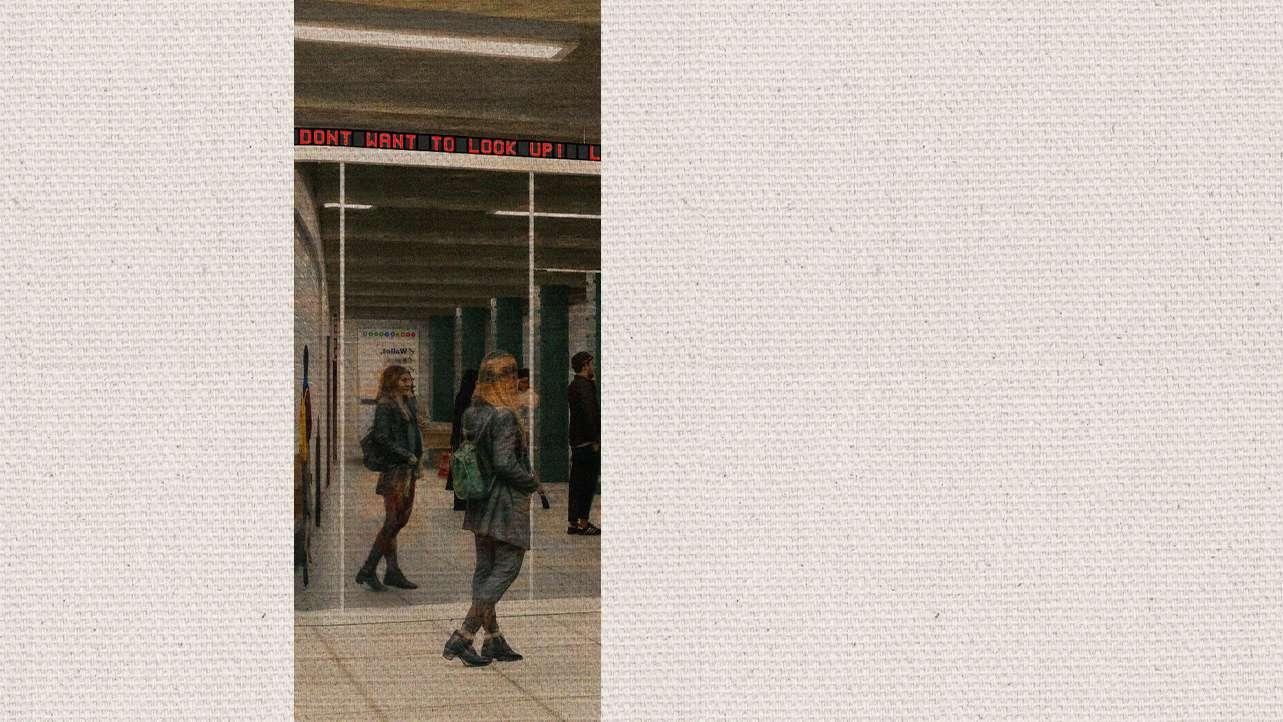

“Subversive Interiors” explores the nuances of public spaces like the NYC subway through the lens of discomfort, fear, and invisibility. This collection harnesses image generation, collages, and model-making to construct a subversive visual narrative that challenges these pervasive issues. By embracing maximalism and employing exaggeration as forms of resistance, each piece distorts reality to an absurd degree, intensifying sensations to provoke a visceral response.

In this study, aesthetic appeal gives way to a multilayered critique of historically female-associated spaces—domesticity, comfort, and familiarity. Elements like floral wallpapers, plush seating, and intricate lighting fixtures transcend their visual appeal, encouraging viewers to reconsider traditional perceptions of public interiors.

This project not only reflects a cycle of personal reflection and expression but also acts as a catalyst for dialogue about the dynamics of comfort, safety, and identity within communal environments. A notable iteration within this series introduces an interior reimagined with mirrors, enhancing visibility in a space typically marked by obscurity and fear, suggesting a mirrored sanctuary that paradoxically heightens individual presence, particularly for women.

Drawing inspiration from defiant historical figures like Rosa Bonheur and Romaine Brooks, “Subversive Interiors” advocates for a reimagined public realm where women can assert themselves freely and safely. As I look forward, my plans involve the creation of to-scale models to further refine these concepts, enhancing the tangible impact of the designs and deepening our understanding of space and materiality. This exploration is not merely an artistic venture; it is a call to action for greater inclusivity and thoughtful consideration in the design and planning of public spaces.