URBAN LANDSCAPE OF GRIEF

Exploring the Transformative Dynamics of Grief, Rituals, and Interior Typologies

Ashima Yadav

Designer Statement

Experiences are all around us, rooted in the core of spaces and technology, triggering human emotions, altering perceptions, and titillating senses. As an experience designer, I orchestrate these elements into captivating narratives that breathe life into the ordinary.

As an engineer and designer captivated by the profound influence design wields over the intricate interplay between spatial design and the vast spectrum of human encounters through the layers of cultural stories and conflicts of society, I am a designer placing my work amidst these stories attuned to the emotive dimensions inherent within. I see technology not merely as a tool, but as a conduit for understanding and expressing the intricate tapestry of human emotions. Through careful integration, I leverage technology to capture the subtle nuances of the emotional landscape with the overlap of spatial dimension, translating them into tangible design elements that resonate deeply with individuals

Here at the intersection of design, science, and technology is where I locate my practice as a designer. By designing interiors informed by science and human values to complement emotional experiences , my design practice works towards using the interior as an active participant in serving as more than mere space but as a journey of woven frames embracing cultural inclusivity through the universal language of emotions.

Table of Content

Abstract

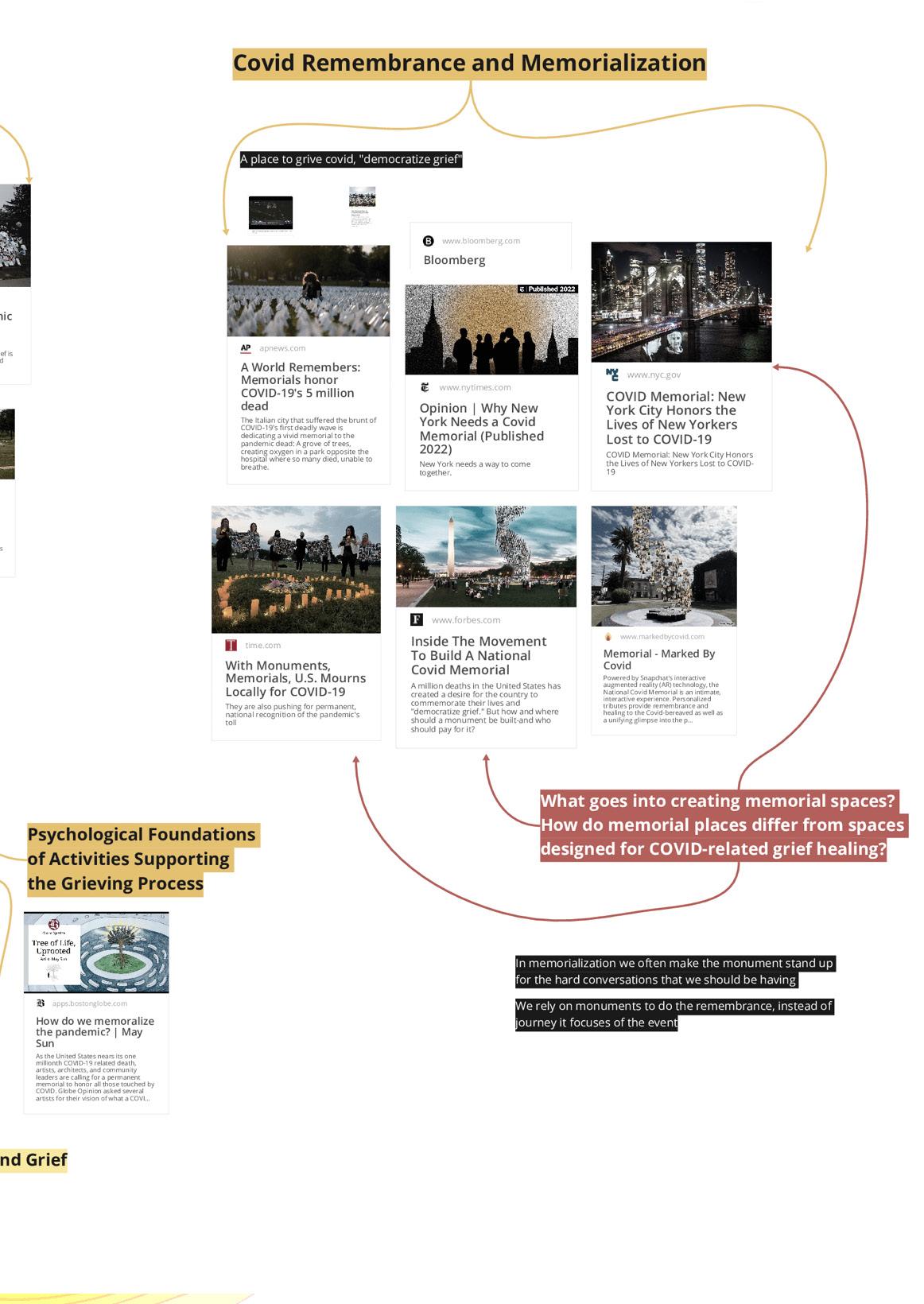

This research aims to explore how the urban environment influences the expression of grief post Covid -19. Considering the cityscape as a layered canvas, it is not only a reflection of life’s vibrancy but also a manifestation of social interactions and customs related to death and remembrance. Covid -19 has brought upon a sense of collective grief that has remained largely confined within the private sphere, never expressed once the lockdown ended, no place dedicated to grieve the loss.

Grieving, a structured process rooted in early human civilizations, revolves around specific spaces or tangible objects.1 These rituals, with multifaceted purposes, act as commemorative performances and crucially serve to manage the overwhelming sense of loss. In moments of intense emotion, individuals often turn to makeshift spaces, 2 typically not designed for such purposes in Hinduism. Existing environments inadequately address the complexities of profound and negative human emotions. Hence, it is crucial to examine intentionally tailored spaces accommodating these emotions and analyze their consequential effects.

The study seeks to comprehend how a place becomes an integral part of the grieving journey and explores the unique experiences tied to the spatial aspects of mourning and loss.3 The research methodology investigates into the nuanced spatial dynamics of Hindu mourning sites such as Varanasi, probing their intricate connection with the psychological effects of the grief cycle on individuals. This exploration illuminates the interconnection among these spaces, rituals, phenomenological experiences, and their psychological ramifications on the process of grief, thereby informing and shaping these emotional landscapes.

1. Ijraset. “Architecture of Death: Multifaith Burial and Cemetery Centre.” IJRASET, n.d. https://www. ijraset.com/research-paper/architecture-of-death-multifaith-burial-and-cemetery-centre

2. Publishers, Frame. “Can Architecture Console Mourners as They Experience the Pain That Accompanies Grief?,” December 12, 2022. https://frameweb.com/article/living/can-architecture-console-mourners-as-they-experience-the-pain-that-accompanies-grief.

3. Publishers, Frame. “Can Architecture Console Mourners as They Experience the Pain That Accompanies Grief?,” December 12, 2022. https://frameweb.com/article/living/can-architecture-console-mourners-as-they-experience-the-pain-that-accompanies-grief.

Introduction

In the daily tapestry of existence, the significance of coexisting with mortality, particularly in the context of structures associated with death and the dying process, has diminished. Within this intricate web, there exists a micro-network dedicated to various facets of death. Some architectural expressions engage with the living and the progression of death, while others address the aftermath of life. Additionally, there exists a distinct category of architecture designed solely to ensure that the survivors continuously remember—the architecture of memory.1

Between the aftermath and the realm of memory, the intricate emotion of grief unfolds. The grieving process typically finds its structure and expression in spaces or tangible objects. Such rituals and rites can be traced back to the very first human civilizations. The purpose of these rites is the following:

“The performance of the commemorative ritual was also intended to tame the feeling of loss and render it a natural transition to the other world. In this way, the public ritual of taming death created a sense of control, allowing its participants to overcome loss.”2 Rituals not only shape everyday activities but also invoke psychological understanding. We observe how rituals play a psychological role in guiding individuals through the cycle of grief. Yet, we do not discern the integration of both ritualistic aspects and psychological elements into the fabric of architecture. While death itself is often articulated in spatial metaphors like ‘passing to the other side’ or ‘moving to a better place,’ grief and mourning are more commonly articulated in temporal language, such as ‘it takes time’ and ‘time heals.’3 Yet, within this linguistic framework, there exists a gap—a lack of landscapes that seamlessly accommodate both the spatial and temporal dimensions of this profound human experience.

Scholars have argued ‘embodied emotions are intricately connected to specific sites and contexts’: bereavement, grief, and mourning are experienced within space.4 Ceremonies for the loss of a loved one are highly sensitive and personal, yet the settings in which they occur are borrowed environments that often fail to offer comfort to mourners.5

In Hindu culture, makeshift spaces, which are made out of spaces like living rooms, courtyards, and back gardens, are used to perform rituals and deal with grief. In these spaces, you are subjected to many shifting emotions because of their inadequacies according to the need. Consequently, it becomes pertinent to examine the characteristics of spaces intentionally tailored to accommodate these emotions, analyze their consequential effects, and reveal the interrelationships between the material and emotional-affective, cognitive and sensory, the individual or group, and their wider social-cultural contexts.

In order to understand the interiors and spaces of grief, I started to examine spaces from both an individual usage lens and from a social landscape perspective, and how rituals can be juxtaposed with psychology to create these spatial moments . Starting at the city and community scale. I am examining Varanasi’s research through the prism of its unique cultural identity, characterized by its portrayal as a city without a discernible commencement or conclusion, serving as a liminal space for existence. This locale boasts a distinctive outlook on life and introduces a novel approach to the concept of death. The city’s tourism is intricately linked to these phenomena and rituals, significantly influencing the social, political, and communal framework of Varanasi.

Varanasi serves as an exemplary paradigm where individuals confront mortality and perceive life from an alternative standpoint. The city itself functions as a mechanism for

grieving, normalizing, and coexisting with the deceased. Consequently, I aim to explore how the dynamics of this urban ecosystem can contribute insights to the evolution of interior typologies.

Alternatively, I am examining it on an individual scale. When we talk about spatial relation, the primary space of mourning as embodied by the mourner, they (we) carry grief within and can potentially be interpellated by it at any juncture of timespace. In the words of an evocative pop song, ‘Everywhere you go, you always take the weather with you’

The shaping of spatial experiences takes into consideration sound muffling, surroundings blurring, body contraction, and the interaction between oneself and the surrounding space or energy. To alleviate the constant pain, individuals adhere to rituals

and spirituality, redirecting their focus on life. These practices are designed for personal experiences and to alter the current realm of the mind. The question arises: How do these practices, in turn, reshape or construct spatial experiences for individuals? Recognizing the mobility of embodied and relational grief opens the door to a deeper understanding of the intricate and dynamic spatial patterns inherent in grief, mourning, and remembrance.

How does a place become an integral part of the grieving journey, and what are the unique experiences tied to the spatial aspects of mourning

Glossary

Rituals

Rituals serve as a fundamental and structured framework that imbues life with meaning and purpose. They go beyond mere routine or habit, acting as foundational elements that shape and define various aspects of our existence. These rituals play a crucial role in bringing communities together, fostering a sense of unity and shared experience. Whether deeply rooted in cultural traditions or personalized to individual beliefs, rituals serve as significant markers in the journey of life, providing a sense of order, continuity, and connection to something greater than oneself. They contribute to the collective identity of communities and offer a framework for individuals to navigate the complexities of life with a sense of coherence and significance.

Micro Network of death

It represents a spatial web that encompasses the recognition of the presence of procedures and rituals related to death, including their physical layout and diverse locations where they are observed. This concept can be further categorized into three distinct types of architectural structures, each serving a specific purpose in relation to death. The first category involves spaces that address the living and the process of dying, such as hospitals and hospices. The second category pertains to spaces that deal with the aftermath of life, like morgues and crematoriums. Finally, there exists another class of architecture that is designed to ensure that those who continue to live never forget the departed—this is the architecture of memory, encompassing memorials and mausoleums.

Physical or material culture

tangible items, relics, and architectural elements connected to death, the process of dying, and the experience of mourning within a specific culture or society. These artifacts can illuminate the intricate connections between the material and the emotional, cognitive, and sensory dimensions, as well as how they intersect within the individual or collective and extend into broader social and cultural contexts. Material possessions linked to the departed may take on renewed significance for those in mourning, such as seemingly ordinary items like shoes or shopping lists, which gain a profound importance (Hallam & Hockey, Citation)2001) which become emblematic of the deceased or of their absence. These spaces create their own emotional geography, which reflects the spatial connection of bereavement.

Embodied-Psychological

Embodied-psychological” is a term that describes the complex interplay between an individual’s physical or bodily experiences and their psychological or mental processes. It highlights the idea that our physical sensations, movements, and bodily states can significantly influence our thoughts, emotions, and cognitive functions. This concept recognizes the bidirectional relationship between the body and the mind, emphasizing how our physical experiences and sensations can impact our psychological well-being and vice versa.

Topography of grief

The “topography of grief” refers to the complex and multidimensional landscape of emotions, experiences, and expressions associated with the process of grieving and mourning after the loss of a loved one or a significant life event. This term encompasses the various psychological, emotional, social, and cultural aspects that contribute to an individual’s unique journey through grief, including the terrain of emotions, coping mechanisms, cultural rituals, and interpersonal support networks that shape how one navigates and processes their grief.

Bodily ‘disposal’

Bodily ‘disposal’ refers to the set of processes and practices involved in the respectful and culturally appropriate management of a deceased person’s remains after death. This includes methods such as burial, cremation, embalming, or other rituals and procedures used to handle the deceased body, ensuring its proper care and, in many cases, its return to the natural environment or transformation into ashes or other forms as dictated by cultural, religious, or personal beliefs and customs

The relationship between this ‘bodily disposal’ process and its spatial context involves understanding how it interacts with and contributes to the connection between the physical space and the emotions and traditions associated with it

Deathscapes

“Deathscape” is a term used to describe the physical and emotional landscape or environment associated with death,

dying, and mourning. It encompasses the places, spaces, and objects that are closely linked to the experience of death and the rituals, practices, and emotions surrounding it. This term can be used to refer to cemeteries, funeral homes, crematoriums, gravesites, memorials, and other places that play a significant role in the cultural, religious, and social aspects of how individuals and societies engage with death and the deceased. Additionally, “deathscape” can also extend to the emotional and psychological terrain of grief and mourning

Implicist Memory

Implicit memory, alternatively termed unconscious or automatic memory, operates by leveraging past experiences to recall information without conscious effort. This type of memory taps into our prior experiences, regardless of how much time has elapsed since those experiences occurred. Implicit memory also shapes our subconscious connection to objects by linking events associated with the objects to our own experiences.

Bereavement geographies

It involves the spatial manifestation and assimilation of grief, enabling us to chart and understand the personal and shared responses to the loss of a significant individual. This raises the question of how to access the dimensions of experience that go beyond or transcend traditional representation. While death is frequently framed in spatial metaphors like ‘passing to the other side’ or ‘going to a better place,’ expressions of grief and mourning are often couched in temporal terms, such as ‘it takes time’ and ‘time heals’

The Topography of Grief

The topography of grief is karst, riddled with sinkholes that suddenly open under your feet, swallow you whole.

I don’t know what I expected to feel. Not this emptiness. Not nothing. I don’t cry at the sight of my dad’s signature.

The letter from probate court I’ve been expecting. I know what it contains: a form letter and a copy of dad’s will.

I cry when I pack his chessboard, lay the wooden pieces to rest in their velvet-lined compartments, close the box, latch the lid.

by Agnes Vojta

by Chase Dimock “Utah Karst” (2021)

Theoretical Approach

Ritual Theory

“Symbolism is the most ancient and universal form of sociological thinking.”- Victor Turner

Rooted in anthropology and concentrated on the cultural and dimensional aspects of rituals and grief, ritual theory constitutes a theoretical framework that delves into the transformative essence of rituals within society. The fundamental idea driving Ritual Theory is its emphasis on the profound impact of rituals in shaping societal norms and behaviors. In the context of design, the passage underscores the critical relevance of ritual theory, particularly in shaping everyday activities and fostering a deeper psychological understanding. It suggests that rituals, as highlighted by the theory, are not only inherent in cultural practices but also play a pivotal role in addressing profound human experiences, such as grief. The theory posits that rituals provide a structured and meaningful framework for individuals navigating through the complexities of grief. Understanding the intricate relationship between ritual theory and the psychology of grief becomes paramount for designers, as it enables the creation of spaces that acknowledge and support individuals in their emotional processes.

Main Authors: Arnold Van Gennep, Victor Turner

Psychological Perspectives on Grief

“The reality is that you will grieve forever. You will not ‘get over’ the loss of a loved one; you will learn to live with it. You will heal, and you will rebuild yourself around the loss you have

suffered.”-Elisabeth Kübler-Ross

Rooted in the realms of anthropology and psychology, the Psychology of Grief operates as an explorative field, delving into the intricate psychological dimensions surrounding the experience of loss. The fundamental tenet of this domain is the examination of the emotional stages that individuals undergo when confronted with bereavement. The significance of the Psychology of Grief to the field of design becomes evident as it incorporates insights from psychology, particularly emphasizing the psychological role of rituals in shepherding individuals through the cyclical journey of grief. This research underscores the imperative for architectural considerations to integrate psychological elements when conceptualizing spaces associated with death, recognizing that the design of such spaces profoundly influences the emotional well-being and experiences of those grappling with loss.

Main Authors: Elisabeth Kübler-Ross

Spatial Theory and Phenomenology

“My body is the fabric into which all objects are woven, and it is in this sense that the world is given to me.”-Maurice Merleau-Ponty

Rooted in spatial theory and phenomenology, the exploration of the relationship between individuals and their spatial experiences during grief constitutes a significant context for this inquiry. Spatial Theory, at its core, delves into how physical spaces wield influence over human behavior, shaping and molding

individual and collective experiences. Simultaneously, phenomenology illuminates the subjective dimensions of these spatial encounters, focusing on the nuanced and personal aspects of how individuals experience and interpret space. The fundamental ideas within this context emphasize not only the tangible impact of physical environments but also the intricate interplay between these external surroundings and the subjective, internal perceptions of those who navigate them. In terms of design, this framework stresses the importance of comprehending how grief is intricately woven into spatial experiences, underscoring the need to craft environments that not only accommodate but also empathetically respond to the varied and nuanced ways individuals engage with space during times of bereavement.

Main Authors: Gaston Bachelard, Maurice Merleau-Ponty.

Liminality and Existential Philosophy

“Liminal entities are neither here nor there; they are betwixt and between the positions assigned and arrayed by law, custom, convention, and ceremonial.” - Victor Turner

Situated within the realm of existential philosophy and the concept of liminality, the exploration of Varanasi as a liminal space introduces a captivating context to this inquiry. Existential philosophy, at its essence, grapples with profound questions regarding existence, meaning, and the nature of being. In parallel, the concept of liminality directs attention to transitional spaces and experiences, where

individuals often find themselves at the threshold of change, transformation, and contemplation. The fundamental ideas inherent in this context underscore the complex and existential nature of Varanasi, a city portrayed as lacking a definitive beginning or end. The characterization of Varanasi as a liminal space aligns with the city’s function as a locus for transitions, be they physical, spiritual, or existential. In terms of design, this philosophical and liminal context urges an exploration of how spaces can be conceived and crafted to embody and facilitate these transitions, offering environments that resonate with the profound existential questions that Varanasi encapsulates.

Main Authors: Martin Heidegger, Victor Turner.

Mobility Studies and Embodied Grief

Rooted in the realms of mobility studies and the embodied nature of grief, this exploration delves into the intricate relationship between the movement of people and ideas, as scrutinized by Mobility Studies, and the physical and emotional aspects of grieving, as examined by the concept of Embodied Grief. The fundamental ideas inherent in this context underscore the dynamic interplay between the mobility of individuals and the deeply embodied and relational nature of grief. In terms of design, this prompts a consideration of how spaces can be conceived to accommodate the fluid and evolving experiences of grief. The recognition of dynamic spatial patterns becomes crucial in creating environments that resonate with the multifaceted and transformative nature of grief within different spatial contexts

Main Authors: John Urry.

and its relation with time and life

Filha-de-santo being incensed at a ritual in the Centro do Caboclo Tupiniquim, Salvador, Brazil.

Photo: Tao DuFour.

Greif

Case Studies

1.

An Occupation of Loss

Can a structure give shape to something as enigmatic as grief?

Contrary to serving as a source of solace, this installation embodies the essence of grief. The performative dimension of the installation centers on “professional mourners” who, in the representation of diverse global traditions, engage in collective expressions of sorrow. Simultaneously, they partake in activities such as weeping, chanting, singing, playing music, and executing various grief-related rituals, each adorned in attire reflective of their respective cultural backgrounds.

This performance is done in these columns, inspired by inverted wells, negative space turned positive. “I thought about making this humongous structure, which is usually invisible,” Simons says, “then flipping it above ground and making it visible and audible.

Kubota, Naho, ed. Taryn Simon: An Occupation of Loss. n.d. Armoryonpark

Kubota, Naho, ed. Taryn Simon: An Occupation of Loss. n.d. Armoryonpark

The wells take on both profoundly monumental and personal dimensions, echoing the awe-inspiring scale of grief-related structures like monuments and tombs.Inhabited by these individuals, whose occupations are to guide and shape our grieving, the space is occupied by an abstracted loss. Simultaneously, it draws you nearer to the mourners, who sit on small ledges inside each structure. It often feels like you’re too close. You’re invading their space and sharing an intensely person-

al moment, like you’re inside a movie scene or part of their family. This immersive experience guides individuals through a profound psychological realm, enabling them to project diverse cultural and emotional interpretations of loss onto both the performers and the spatial context. These wells serve as a framework for delving into the spatial and phenomenological facets of grief, underscoring the significance of both individual experiences and the collective perspective of the audience.

Kubota, Naho, ed. Taryn Simon: An Occupation of Loss. n.d. Armoryonpark

“With the times we’re living in and this continuous broadcasting of tragedy, we have this impulse to go in and out of those losses,” says Simon. “The architecture reflects that kind of behavior.”

- Shohei Shigematsu

In daylight hours, when the structures are devoid of performers, children, and sporadically adults, engage in vocalizations, whistling, and applause within, displaying an unawareness of the profound sense of loss encapsulated by the columns. Strikingly, this audial activity is tolerated, resonating with innocence reminiscent of a lively playground adjacent to a burial ground.

The structure possesses a unique capacity to articulate the emotional state of the mourner within, compelling individuals to be drawn towards it and encouraging their participation in the mourning process. “It’s quite difficult to pin down,” said Shigematsu. “In the end, it’s all about intuition. You’re ultimately trying to feel the feeling of people feeling grief.”

Kubota, Naho, ed. Taryn Simon: An Occupation of Loss. n.d. Armoryonpark

2.

Matri Mandir

In the course of my investigation into environments tailored to accommodate profound human emotions, notably grief, I encountered Matri Mandir, delineated as “a locus for the exploration of one’s consciousness.” Operating as a spiritual sanctuary conducive to introspection, the site emanates a tranquil and energized ambiance, notwithstanding ongoing horticultural activities. The Mother, construed as the “symbol of the Divine’s response to humanity’s yearning for perfection” and the central cohesive force in Auroville, underscores the profound significance of this locale. The nomenclature ‘Matrimandir,’ signifying ‘Temple of the Mother,’ aligns with Sri Aurobindo’s teachings, ascribing it to the grand evolutionary, conscious, and intelligent principle of life—the Universal Mother.

“The Mother is the consciousness and force of the Supreme and far above all she creates. But something

of her ways

can be

seen and felt through her embodiments and the more seizable because more defined and limited temperament and action of the goddess forms in whom she consents to be manifest to her creatures.”

-Sri Aurobindo

The space is characterized by ritualistic practices divorced from religious affiliations, constituting a secular environment designed to assist individuals in aligning with their individual journeys. It serves as a suggestive space that accommodates both individual and collective needs while avoiding imposition.

“Let it not become a religion,” the mother said. “The failure of religions is... because they were divided. They wanted people to be religious to the exclusion of other religions, and every branch of knowledge has been a failure because it has been exclusive. What the new consciousness wants (it is on this that it insists) is: no more divisions.”

Louw,Adriaan,ed.Puducherry’sBestKeptSecrets.March1,2016.

“To be able to understand the spiritual extreme, the material extreme, and to find the meeting point, the point where that becomes a real force.”

-Mother

Bereft of religious affiliations, it encourages individuals to align with their distinctive journeys and functions as a suggestive milieu, addressing both individual and collective requisites.

Quiet Contemplation:

Matrimandir designates specific areas for silent meditation and contemplation, fostering a serene setting conducive to reflecting on the intricate emotions linked with grief.

Collective Meditation:

Intermittent collective meditation sessions at Matrimandir instill a sense of shared energy and support, fostering a connection among individuals navigating their respective healing journeys.

Personal Reflection:

The Inner Chamber, configured for

silent concentration, provides a space for personal reflection, aiding individuals in processing emotions and deriving meaning in their journey through grief.

Spiritual Exploration:

Matrimandir serves as a consecrated space for spiritual exploration, transcending religious confines. Engagement in spiritual practices or mere presence in a contemplative environment cultivates a sense of connection and purpose amid challenging circumstances.

Symbolism of Unity:

The central golden sphere of Matrimandir, symbolizing universal consciousness, imparts a message of unity and interconnectedness, offering solace that extends beyond individual loss.

This place is a noteworthy exemplification of spiritual and phenomenological theories elucidating the intertwining of spaces and experiences. Emphasizing the spatial circulation marked by nodes of both collectivity and individuality, it provides valuable insights into the theoretical discourse on the interaction between spiritual and phenomenological aspects within a given environment.

Louw,Adriaan,ed.Puducherry’sBestKeptSecrets.March1,2016.

Creative Practice

Theories

Theory of Repetition

Theory: Engaging in positive, repetitive activities can serve as coping mechanisms for managing stress and promoting mental well-being. Rituals, routines, and habits can provide a sense of stability and control.

Mental Health Impact: Positive repetition can contribute to emotional regulation, stress reduction, and a sense of predictability, which are essential components of good mental health.

Flow Theory (Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi):

Fundamental Ideas: Csikszentmihalyi’s Flow Theory focuses on the state of optimal experience where individuals are fully absorbed and engaged in an activity. He emphasizes the psychological benefits of achieving a flow state, including a sense of fulfillment, heightened creativity, and the perception of time passing quickly.

Relevance to the Research: The concept of “flow” is directly relevant to the research, as it suggests that engaging in creative activities, such as crafting, can lead to a state of flow, contributing to happiness and well-being.

Spatial Theory and Phenomenology:

Context: draws from spatial theory and phenomenology, exploring the relationship between individuals and their spatial experiences during grief.

The examination of spaces from both individual and social perspectives suggests an engagement with spatial theory and phenomenology. Understanding how individuals experience and shape spaces during grief involves considering the interplay between physical environments and subjective perceptions.

“Nestled within the intricate knots, I found an embrace that resonated with the sanctuary I had either constructed or, perhaps, that had been constructed around me. Observing the threads weave and shape a cocoon, my sense of security expanded with the growing interior. Knotting, as a ritual, offered a soothing distraction, a shield from the clamor of the external world, rendering me untouchable and protected. This practice, both a calming ritual and a modular interior tailored to my form, became a haven of solace.”

-Self

Community Research

1. Varanasi: A Liminal Nexus of Existence

I am examining Varanasi’s research through the prism of its unique cultural identity, characterized by its portrayal as a city without a discernible commencement or conclusion, serving as a liminal space for existence. This locale boasts a distinctive outlook on life and introduces a novel approach to the concept of death. The city’s tourism is intricately linked to these phenomena and rituals, significantly influencing the social, political, and communal framework of Varanasi.

Known as one of India’s holiest cities and a popular tourist destination, Varanasi is a unique creation of Indian culture and ritual. the beginning and end of all life, the epicenter of creation, the spot of ultimate transformation, the passageway through which souls achieve moksha.

“In Varanasi there are no beginnings and endings, only passages and transformations.” by one of the dom raja

Varanasi stands as an ancient marvel, revered as the world’s oldest inhabited city. In the words of the renowned writer Mark Twain, “Benares [Varanasi] is older than history, older than tradition, older even than legend, and appears doubly aged when considering all of them collectively.”

Varanasi emanates a spiritual essence, drawing thousands of pilgrims globally to partake in the city’s profound energy. Annually, more than 2.5 million individuals immerse themselves in the Ganges, marking a central aspect of life. Amidst prayers, the Ghats, concrete riverfront steps, witness funeral pyres ablaze. Varied in purpose, these Ghats span several miles, serving as sites for diverse rituals, ceremonial baths, and celebratory gatherings.

ThepictureshowsoneofthemanyGhatsofVaranasi. Photoby Prof.SumantRao,RuchiShahandPiyushverma

As the preeminent city, Varanasi serves as a confluence of diverse religions and cultures. Embracing death positively, the city pulsates with rituals that not only acknowledge death but exalt life. These local ceremonies in Varanasi transcend mere observance; they assume a vibrant life of their own. Revered as the place where Hindus seek the culmination of life, dying and being cremated in Varanasi is considered the highest honor. Some devotees allocate their life savings for this sacred act. The Doms, designated keepers of the flame due to a legend involving Lord Shiva, diligently conduct pyre burnings throughout the week, guiding the departed toward enlightenment.

“Banaras apne mai dooba nazar aata hai”

Varanasi, with its rich tapestry of traditions and rituals, creates a city-scale interior of grief, where death is interwoven with life in a harmonious and celebratory dance.

During my visit to Banaras, I encountered a spectrum of emotional responses, including sensations of tranquility, contentment, solace, and security derived from the perpetual embrace of nature. These multifaceted experiences prompted a delineation between tangible and intangible factors, culminating in a comprehensive understanding of holistic experience. Utilizing these tangible elements as guiding criteria informed my site selection process.

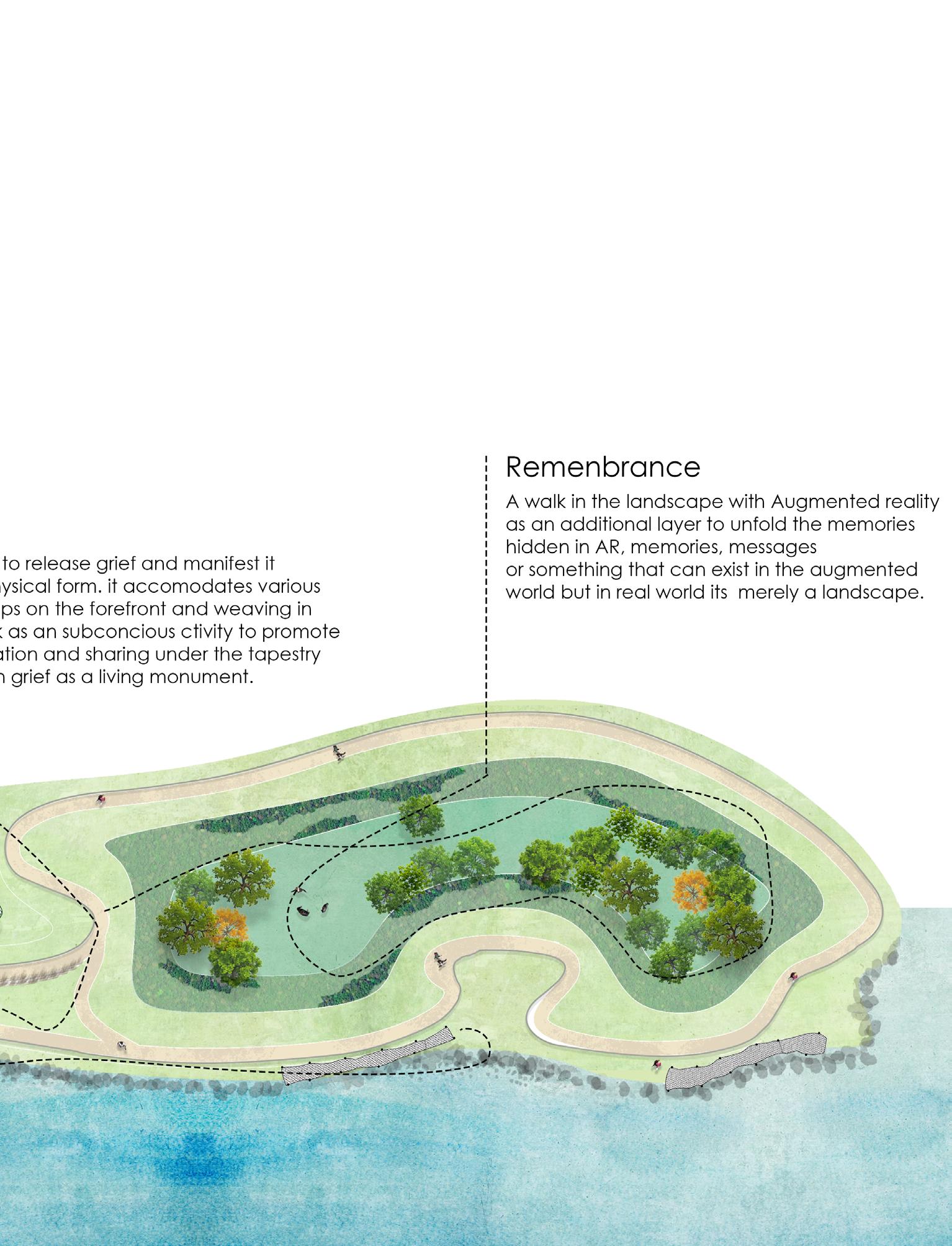

Governors Island, nestled amidst the glistening waters of New York Harbor, has a rich history of military significance, serving as a strategic stronghold and bastion of defense for centuries. Access to the island was historically restricted to military personnel and affiliated individuals, imbuing the area with a distinctly militaristic ambiance and a strong sense of protective vigilance. Until very recently, when it was opened for public use, making it accessible to all as an economical getaway,. This shift in accessibility ushered in a complete transformation of the social landscape, transitioning from a rigid paradigm to one characterized by retreat and relaxation. Its purpose evolved into providing a tranquil escape from urban chaos, fostering opportunities for rejuvenation and selfcare, and diverging significantly from its former militaristic role.

The geographic criteria dictated the selection of a site along the riverbanks, providing optimal visibility of sunsets and sunrises. The primary objective was to leverage the diverse natural elements of water, land, wind, and light inherent to the location, enriching the foundational framework of the site design.

Subsequently, attention turned to materiality and environmental considerations as a secondary layer shaping the site’s ambiance. This facet serves to enrich the visitor’s experience and evoke the intended emotions. Remaining closely connected to natural elements, observing life in its various forms, and appreciating the rhythmic movements and patterns of nature contribute additional layers to the site’s complexity and allure.

The chosen site serves as a tangible exploration of these inquiries, offering insights into the emotional experiences associated with grieving. By examining the site’s materiality and natural/geographical aspects, I aim to discern the typology of grief and the potential for intervention or enhancement in these spaces. The existing issues on the site may include a lack of attention to the emotional needs of individuals experiencing grief, as well as a potential disconnect between the site’s design and its intended purpose as a space for solace and reflection. Opportunities for intervention lie in reimagining the site’s design to better accommodate the varied emotional experiences of visitors, perhaps through programming that fosters healing and support.

Overall, the site serves as a canvas for exploring the intersection of space, emotion, and ritual in the context of grief, offering opportunities for intervention to enhance the healing process for those in mourning.

Program on Landscape

Layers of Journey

1st Stage

A grieving body goes through spatial stages of individual or bodily understanding, wherein the body undergoes a process of absorption and contemplation to find the expression of emotion. These spatial settings, juxtaposed with water and natural elements, provide individual solace devoid of confinement within the expansive openness of the landscape, focusing on bodily needs revolving around texture and materiality

Body Frameworks

Bodily needs of curling up, wrapped around by softness

Growing Tapestry

Writing , engraving , spilling , bodily radiating

Ashima Yadav

Begin your adventure with Augmented Reality as your navigator and tutor, guiding you through this immersive experience.

2nd Stage

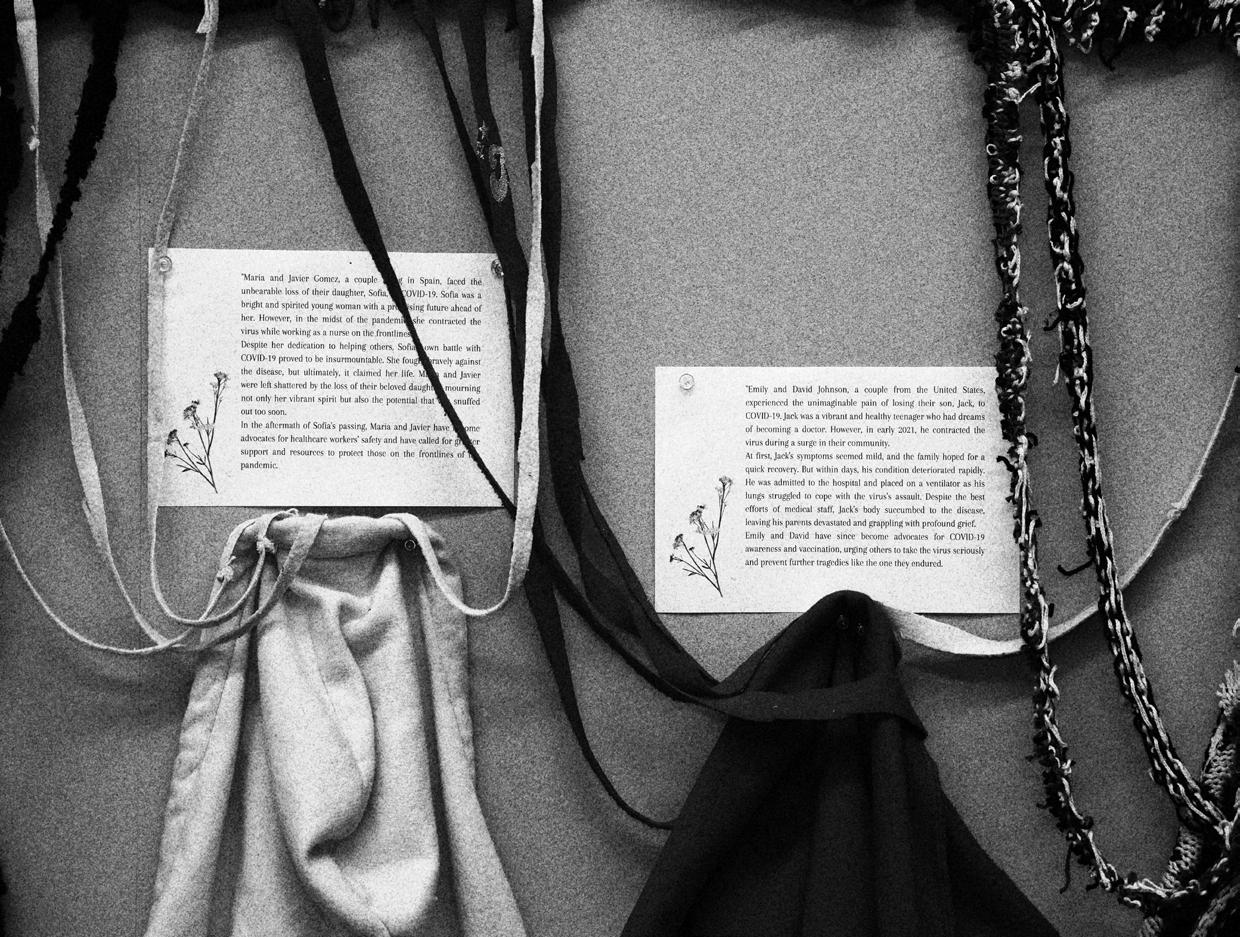

The second stage of grief revolves around how grief wants to be expressed, heard and shared, it seeks acknowledgment and communal dissemination. When these emotions are experienced in space, they form communal weaving spots for collective grieving and to host psychologists directed grief processing workshops. Weaving is a subsequent activity that happens while verbal expressions of stories are out in the open with people.

Those woven pieces then become a tangible testimony to their stories. And get installed as the shed above, giving the progran a architectural structure. Functioning as a living memorial, the program invites users to contribute clothes once owned by the loved ones lost in the shadow of COVID to give shape to the program.

The shed acts as a skeleton for these woven stories to get installed and support, anchored onto the trees and utilizing reverse canopy structure support it stands making a canopy from the weave.

The project comes into being when people are there to experience it—a program that gives grief a physical manifestation, reshaping the landscape with layers of woven tapestry. Weaving and repetitive actions tap into implicit memory processes, serving as fundamental cognitive mechanisms while addressing diverse psychological and spatial needs.

Communal weaving spots

designed for workshops and therapy sessions that allow for the social expression and processing of grief.

Ashima Yadav

‘Can I borrow their clothes’

The program encourages participants to donate clothing previously owned by loved ones lost to Covid to give shape to the program.

Ashima Yadav

AR Navigation

Through this landscape, AR navigates you to different destination and processes in the experiences.

3rd Stage

Memory Symphony

Audio generative installation walk through

In the final stage of the grieving process, individuals reach a point of acceptance where they are comfortable dwelling in memories and revisiting them as acts of remembrance. This pivotal stage culminates in the archival process within the program, enhanced by augmented reality (AR) technology. AR introduces a subtle yet profound layer to the landscape, allowing participants to overlay memories in an audio generative installation, where an audio pattern adapts, transforms, and grows from heartfelt audio messages left in memory of loved ones lost to COVID. This immersive encounter empowers users to imbue the landscape with their memories and messages, fostering a sense of collective mourning and reassurance in the journey of loss. Though concealed, this additional layer remains palpably present within the landscape, offering solace and solidarity amidst the grieving process.

Overlaying Memories

Hidden layers as part of the natural topography giving shape to topography of grief

Ashima Yadav

Living Memorial

Layer to the landscape, allowing participants to overlay memories, Auditory experience.

Bibliography

• Marriage, Guy. “The Architecture of Death.” ResearchGate, October 1, 2018. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/328474434_The_architecture_of_ death.

• Publishers, Frame. “Can Architecture Console Mourners as They Experience the Pain That Accompanies Grief?,” December 12, 2022. https://frameweb. com/article/living/can-architecture-console-mourners-as-they-experience-the-pain-that-accompanies-grief.

• Maddrell, Avril. “Mapping Grief. A Conceptual Framework for Understanding the Spatial Dimensions of Bereavement, Mourning and Remembrance.” Social & Cultural Geography 17, no. 2 (October 16, 2015): 166–88. https://doi.org/10.1 080/14649365.2015.1075579.

• Ijraset. “Architecture of Death: Multifaith Burial and Cemetery Centre.” IJRASET, n.d. https://www.ijraset.com/research-paper/architecture-of-death-multifaith-burial-and-cemetery-centre.

• Hays, Jeffrey. “HINDU CREMATIONS | Facts and Details,” n.d. https:// factsanddetails.com/world/cat55/sub388/entry-5652.html.

• Farley, David. “Embracing the Cycle of Life in India’s Holiest City - AFAR.” AFAR Media, May 10, 2014. https://www.afar.com/magazine/varanasi-indias-soul-city.

• House, Crowded. “Crowded House - Weather With You.” Youtube. Accessed December 9, 2023. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ag8XcMG1EX4&ab_ channel=CrowdedHouseVEVO.

• Medina, Adrian Lopez. “An Occupation of Loss: The Performance of Architecture and Grief.” Journal, May 31, 2022. https://architizer.com/blog/inspiration/ stories/an-occupation-of-loss-architecture-and-grief/.

• Architizer. “Idea 1761243: An Occupation of Loss by OMA in New York, United States,” n.d. https://architizer.com/idea/1761243/.

• Park Avenue Armory. “Taryn Simon at Park Avenue Armory,” n.d. https://www. armoryonpark.org/photo_gallery/slideshow/taryn_simon.

• Asitoughttobemagazine. “Agnes Vojta: ‘The Topography of Grief.’” As It Ought To Be, January 30, 2023. https://asitoughttobemagazine.com/2023/01/30/agnes-vojta-the-topography-of-grief/.

• Gallery, Viper. “Tao DuFour: Husserl and Spatiality: A Phenomenological Ethnography of Space,” n.d. https://www.vipergallery.org/en/events/tao-dufour-husserl-and-spatiality-phenomenological-ethnography-space.

• “Matrimandir - Soul of the City | Auroville,” n.d. https://auroville.org/page/ matrimandir.

• “The Mother on Matrimandir and Religions | Auroville,” n.d. https://auroville. org/page/the-mother-on-matrimandir-and-religions.

• Admin, and Admin. “Spaces of Grief by Max Olof Carlsson Wisotsky | Site-Writing.” Site-Writing | Site-Writing, December 8, 2019. https://site-writing. co.uk/spaces-of-grief-2018/#:~:text=Spaces%20of%20Grief%20is%20an,to%20 grieve%20in%20different%20ways.

• Zimmermann, Kim Ann. “Implicit Memory: Definition and Examples.” livescience.com, February 13, 2014. https://www.livescience.com/43353-implicit-memory.html.

• Columbia GSAPP. “Landscape of Grief and Care - Columbia GSAPP,” n.d. https://www.arch.columbia.edu/student-work/9385-landscape-of-grief-andcare.

• Wilson, Jacque. “This Is Your Brain on Crafting.” https://www.cnn.com/, January 5, 2015. https://www.cnn.com/2014/03/25/health/brain-crafting-benefits/index. html.

• Gutman, Sharon A, and Victoria P Schindler. “The Neurological Basis of Occupation.” Occupational Therapy International 14, no. 2 (February 7, 2007): 71–85. https://doi.org/10.1002/oti.225.

• Abrusci, Leah. “Repetitive Motion Meditation — Steeped In Hope.” Steeped In Hope, July 24, 2023. https://steepedinhope.com/blog/repetitive-motion-meditation.

• Moffett, James. “Writing, Inner Speech, and Meditation.” College English 44, no. 3 (March 1982): 231. https://doi.org/10.2307/377011.

• O’Reilly, Lucy. “Repetition as Inspiration, Meditation and Practice — Liz Inspires.” Liz Inspires, September 8, 2020. https://www.lizinspires.com/blog/repetition-as-inspiration-meditation-and-practice.

• Urban-Brown, Jennifer. “Zen Mind, Knitting Mind – Lions Roar.” Lions Roar, January 21, 2022. https://www.lionsroar.com/zen-mind-knitting-mind/.

• Npr. “Neurotheology: This Is Your Brain On Religion.” NPR, December 15, 2010. https://www.npr.org/2010/12/15/132078267/neurotheology-where-religion-and-science-collide.