SYMPOSIUM Lower Sixth/Year 12 Gender Like You’ve Never Seen it Before

Thursday the 12th of May 2022, 1pm - 5pm The Royal Society, Carlton House Terrace, London

Prologue: a Fresh Approach

By Ms Madeleine Copin,

Deputy Head (Academic) at Notting Hill & Ealing High School.

Interdisciplinary thinking

By Mr Tom Elphinstone, Master in Charge of the Scholars, Harrow School

By Mr Tom Elphinstone, Master in Charge of the Scholars, Harrow School

Literature

Nancy, Divya, Zane, Max, Joseph, Thomas

The models of “wild cruel nature” in King Lear and The Tempest, and how these correspond to the model of womanhood portrayed in these plays. The 21st-century environmental and societal consequences of these portrayals.

Classics

Amy, Alisha, Antonio, Jiho

Links between the description of Hermaphroditus in Ovid’s Metamorphoses and the visual language of the Sleeping Hermaphrodite of the Louvre.

Law & Philosophy

Angelina, Chloe, Harry, Hansen, Alonso

The social and legal frameworks around the Two-Spirit Indigenous people of North America, the Hijras of India and impact of colonialism on the perceptions of these groups.

History

Mairi, Saira, Henry, Oscar

The historical context of women’s shifting place in French society between 1852 and 1900, and its link to Manet’s 1882 painting A Bar at the Folies-Bergère.

8 12 16 22

6

4 Contents Eight ingredients for a successful symposium A recipe for a successful symposium ccccccccccccccccccccccccccccc 20

Politics and Economics

Katie, Zara, Adi, Iyanu

The role of microfinance in tackling the poverty of women, and concerns around this.

Medicine

Sia, Klea, Andre, Justin

Anaesthetic protocols for lower segment Caesarean sections.

Psychology

Hana, Aidan

Factors contributing towards differences in diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Condition in males and females.

Biochemistry

Rhea, Charlotte, Liron, Chris

In some insects, one isomer attracts the opposite sex of that species while the opposite isomer repels the opposite sex of another species. What role does optical isomerism play in this?opposite sex of another species. What role does optical isomerism play in this?

Botany

Olivia, Korina, Hadrian, Nikolai

The evolutionary rationale and biochemical mechanisms which lead to changes in sex expression of Acer pensylvanicum, and implications for forestry conservation.

Mathematics

Anna, Eliza, Sunny, Shawn

Fluidity and transitioning in physical systems: the application of phase transition concepts to the state changes in real-world applications.

Fine Art

Georgia, Omar

A third element in the sequence started by Van Eyck’s Arnolfini Portrait (1434) and Richard Hamilton’s Just what is it that makes today’s homes so different, so appealing? (1956), which explores present-day gender and domestic relationships through complex iconography.

30 34 38 42 46 50 26

Prologue: a Fresh Approach

Gender can be an uncomfortable topic. There are contentious debates around gender equality, the rights of LGBTQ+ communities, and the very existence of biological sex. In a large number of fields from Medicine to Music, Engineering to Economics, Geography to German, this can make it difficult to explore interesting and important questions.

For this innovative symposium project, which ran in the Spring and Summer of 2022, students were given academic questions at the forefront of current academic enquiry, armed with sources selected by subject experts.

Gender features in each of the topics, in some loose way. However, the purpose of the questions was to advance their academic knowledge of the topic areas, separating academic arguments from value judgements. Students were encouraged to adopt an interdisciplinary approach with their peers, drawing from the skills in all of the subjects which they studied, to collectively build an interdisciplinary bank of knowledge.

Students were therefore introduced to university-level academic material, which students at Sixth Form level are never given access to, and given prompts on how to craft an argument.

The symposium launched with a face-to-face session in March 2022, followed by some online meetings. Students then presented their papers at The Royal Society in May. This booklet contains the articles produced.

Ms Madeleine Copin Deputy Head (Academic) Notting Hill & Ealing High School

Ms Madeleine Copin Deputy Head (Academic) Notting Hill & Ealing High School

{For this innovative symposium project, which ran in the Spring and Summer of 2022, students were given academic questions at the forefront of current academic enquiry, armed with sources selected by subject experts.

5

6

Interdisciplinary thinking

You might ask what a man with an unhealthy interest in frogs’ legs, a wayward seventeen-year-old girl and a monster made up of once-interred body parts have in common, but out of this unlikely cocktail came one of the most extraordinary works of literature ever written. Mary Shelley was inspired by the strange experiments of Luigi Galvani who made frogs’ legs twitch by passing an electrical current through them. In a discussion with Lord Byron, she outlines the connections she then made on her journey to writing Frankenstein: “Perhaps a corpse would be re-animated; galvanism had given token of such things: perhaps the component parts of a creature might be manufactured, brought together, and endued with vital warmth.”

Like Mary Shelley, who looked at twitching frogs’ legs and wondered whether corpses too could be revived by electricity (she wasn’t far off inventing the defibrillator, was she?), two hundred years later boys from Harrow School and girls from Notting Hill and Ealing High School were also encouraged to think, collaborate and create in an interdisciplinary manner. The results were fascinating.

The Royal Society’s motto ‘Nullius in verba’ is taken to mean ‘take nobody’s word for it’. It is an expression of the determination of Fellows to withstand the domination of authority and to verify all statements by an appeal to facts established by experiment. The very first ‘learned society’ meeting on 28 November 1660 followed a lecture at Gresham College by Christopher Wren. Joined by other leading polymaths – passionate believers in the importance of interdisciplinary enquiry – the group soon received royal approval, and from 1663 it would be known as ‘The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge’.

On Thursday 12th May in 7 Carlton Terrace, Harrow School and Notting Hill and Ealing High School formed their own Royal Society, but with one big difference. Unlike the societies of old, there were girls in the room! (Who can tell how much more quickly the world might have developed if half the population had been given a charter to think, innovate and bring about change?). For one stimulating afternoon of presentations, Chemistry, Mathematics, English Literature, History and Art were no longer separate disciplines, but rather deeply interrelated strands of a vast body of knowledge as the mixed teams explored the theme of ‘gender’ in surprising and enlightening ways.

‘I bid my hideous progeny go forth and prosper,’ Mary Shelley urged her novel in the 1831 preface to Frankenstein. The boys and girls from Harrow School and Notting Hill & Ealing High School offer the same encouragement to their essays in this collection, hoping that you will read them in the playful spirit of interdisciplinary enquiry.

Mr Tom Elphinstone

Mr Tom Elphinstone

7

Master in Charge of the Scholars Harrow School

Literature

Although the modern-day climate crisis seems far removed from the iambic pentameter, literature does not exist in a vacuum, and Shakespeare’s works, most notably King Lear and The Tempest, demonstrate the power over and sovereignty of women, nature and the wild. Through the lens of ecocriticism, an immensely strong correlation is present between the power dynamics of said plays and the cruel dominion over our natural environment, resulting in pollution and extinction, and over women and other oppressed members of society, leading to disparity between groups.

Prospero’s persistent control over nature corresponds to his relationship with Miranda.

Throughout The Tempest, Prospero is presented as a domineering figure, having conquered the island in which the play is set. In Act 1 Scene 2 in particular, Prospero’s illicit conquest of the island is mentioned by Caliban, who says to him, ‘This island’s mine by Sycorax,

my mother, / Which thou tak’st from me’, before the audience hears Prospero’s threats in which he weaponises nature against others. When exerting his power over Caliban, a less human being (since he ‘is not honoured with / A human shape’), he threatens that a curse he could place upon Caliban for disobeying him could be ‘more stinging / Than bees’. This implies that Prospero, who is a human (just with the addition of magical powers), has power over nature. Furthermore, man’s power over nature is not the only thing explored; nature’s worth when compared to man is as well. Miranda implies that human life is more valuable than the health of nature, saying that she ‘would / Have sunk the sea within the earth’ to protect the human sailors on the ship threatened by the tempest Prospero ordered to sink their ship. These instances of domination and threat, from Prospero, and the understatement of the value of nature, from Miranda, contribute to the sense of

To what extent does Shakespeare’s model of wild cruel nature in King Lear and The Tempest correspond to the model of womanhood portrayed in these plays? What are the 21st-century environmental and societal consequences of this portrayal?

Nancy Saville Smith (NHEHS)

Divya Kaliappan (NHEHS) Zane Marsland (NHEHS)

8

Max Morgan (Harrow) Joseph Mclean (Harrow) Thomas Hobbs (Harrow)

human conquest and control over nature which the audience feels when watching this play.

Prospero’s persistent control over nature corresponds to his relationship with Miranda. Her language, when allowed to speak by Prospero, is submissive and driven by instinctual emotion. In Act 1.2, she has ‘suffered with those that [she] saw suffer’ and exclaims ‘O, the heavens!’, expressing a visceral and wild empathy. Cruelly, Prospero silences (‘no harm!’) and diminishes her empathetic response. Miranda, in her submission to Prospero, and inevitably Ferdinand, is emblematic of the ideal Renaissance woman: to be seen and not heard, and to be controlled by men. She is reduced to her physical attributes; as the critic Metzger states, ‘her [Miranda’s] primary value is her virginity’. Miranda demonstrates the silencing of any good-hearted instinct to a life of compliance, which undoubtedly has its 21st-century consequences. Through New Historicism and a feminist reading, the relationship between Miranda and Prospero leaves a bitter aftertaste.

Animals were, and are, naturally wild. However, through the industrialisation and domestication of animals, this is no longer the case. John Berger argues that in paintings, animals are not displayed for their wild majestic beauty and power. Rather, they are seen as of value and social status (likening a cow to a piece of furniture with four legs). This idea parallels themes of colonialism and oppression in The Tempest, as Caliban is humanised under Prospero’s incessant rule (‘you taught me language’). However, The Tempest offers a more complex view of the tension between wild and domestic, as Caliban, who ‘is not honoured with the human shape’, keeps hold of, or cannot rid, his wild, primitive instinct,

9

In this subliminal moment, Lear directly draws a connection between his unloyal daughter’s cruelty as analogous to the unrelenting “night [that] pities neither wise men nor fools”.

demonstrated by his attempted rape of Miranda. What The Tempest uncovers, and perhaps warns, is that we as humanity will stop at nothing to conquer all that is wild. But, like some lurking form, the wild inside the animal, and us, is omnipresent.

Shakespeare’s depiction of the wild is one synonymous with man’s want for dominion over that which he deems uncontrollable. It is described as an area inhabited by wild untameable creatures, slaves and of course, women. Women, especially those who were deemed to be outside of male confinement such as widows or adulterers, were not deemed members of society until they were judged to no longer be ‘threats’ i.e. remarried. This lack of control is apparent within King Lear as he is unable to control the actions of his two eldest daughters in turn leading to Goneril and Regan eventually seeking to usurp his position upon the throne. Lear outwardly displays his abhorrence for the actions of his daughters going as far as to describe them as ‘unnatural hags’ and is deeply distraught over their decision proclaiming ‘ere I’ll weep. / O fool, I shall go mad!’ Lear wishes to reap all the benefits of the monarchy without having to fulfil the many duties it requires, which becomes the foundations for his eventual upheaval. This intrinsic desire for social status once again furthers this theme of male dominion and may in

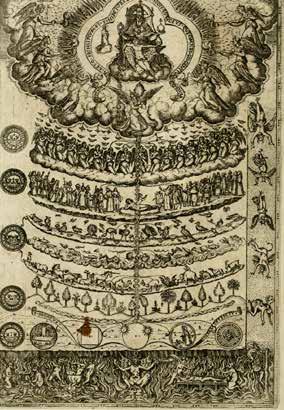

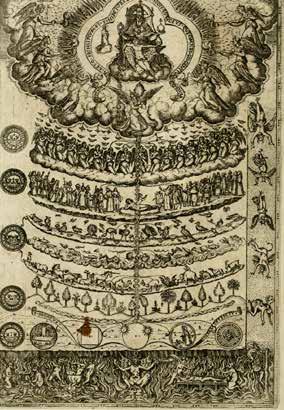

fact have its roots in the way in which we view society. This thought process stems from the quintessentially male construct, rooted in Aristotle’s ‘Great Chain of Being’; this linear image of existence is in great contrast to the non-linear view of women who, rather than seeking to usurp, instead wish for cohabitation, as each member of society is deemed valuable to its inner workings. However, with women being perceived, in the Elizabethan Era, as closer to nature, they would as a result be lower down in the hierarchy and so, closer to the animals and nature. In this way, the women would be more familiar and less disturbed by the powerful effects of nature as they, unlike men, do not wish to climb and reach the top of the hierarchical ladder. This may be why women were viewed as being far closer to nature than men as in much Renaissance art, such as Cesare Ripas’ depiction of nature, the concept is portrayed as one of wild female eroticism ripe for a man’s taking.

Furthermore, the inherent contrast between genders is

brought to light through Shakespeare’s depiction of Nature as a superior force in King Lear. The women (Goneril and Raegan) are portrayed to be far more comfortable with nature as opposed to the men, who are at odds and, as seen with Lear, at times in awe. Roberts titles this difference as ‘The Shakespearean Wild’, in which men are part of the ‘Culture’ whereas the women are part of the ‘Wild’ as they are labelled as ‘slaves, wives, and beasts of burden’, closer to a wild creature and contrary to the Renaissance Man, who so easily controls his feelings and does not persist with erratic moods. As is seen in King Lear, with Lear stating that he would not let ‘a woman’s weapon, water drops stain [his] cheeks’, further highlighting the inherent difference in gender. It is arguable that this is the very essence of the difference in gender that Shakespeare depicts in King Lear, as the perception of women ‘as closer to nature than men’ is what leads the women to ruthlessly and successfully lead a corrupt government while the men fumble, ignorant, in the face of Nature. The male reaction can be seen with Lear in the midst of the storm as he

10

Ultimately, the ‘Shakespearean wild’ represents a prelapsarian fantasy, a wishful reality wherein the earth is uncorrupted by the dominion of machines.

beseeches to Nature, ‘I tax not you, you elements, with unkindness’, directly recognising the ever present cruelty of nature in contrast to his recently turned ‘pernicious daughters’. In this subliminal moment, Lear directly draws a connection between his disloyal daughter’s cruelty as analogous to the unrelenting ‘night [that] pities neither wise men nor fools’. In this way, women are reflected similarly to the wild and uncouth winds that attack Lear, directly corresponding to Shakespeare’s depiction of wild,cruel nature. In this subliminal moment, something which Greg Garrard notes as ‘peculiarly male’, the audience is aware of the extent that Lear is discomforted by the cruel portrayal of nature as he cannot but cry in awe and realise his insignificance in the face of nature. This diminishing of a man in the thick of Nature is seen with Lear as he cowers in the face of Nature as a form of reflection to realise that ‘man is no more but such a poor, bare, forked animal as thou art’; a realisation that the females in Shakespeare have long known and accepted. The women are in acceptance of their likening to nature as Goneril and Reagan become “tigers not daughters”, intrinsically corresponding to the harsh depiction of nature.

Moreover, upon incorporating an ecocritical lens, the connections between Shakespeare’s depiction of ‘wild and cruel nature’ in the aforementioned dramatic works and 21st-century environmental phenomena present themselves in an even more distinct manner. The term ecophobia, as coined by author Simon C. Estok, refers to the human fear of losing control of earth to the forces of nature, forces which as previously mentioned are associated predominantly with women as they have a closer proximity to the ‘wild.’ In particular, this phobia is the main driving factor behind the insecurity of humans concerning their natural environment. Linking to this directly is Prospero and his need to have dominion over the entire island he resides on, mistreating his slave Caliban, as well as imprisoning Ariel on it indefinitely. In this case, a male figure feels emasculated because they have failed to exert their power over the ‘wild’ and the

natural world, a category which extends to female characters such as The Tempest’s Miranda in the same way. Notably, the damaging consequences of the insecurities of Man and Man’s incessant need to ensnare nature are evidenced by real world examples, namely plastic pollution, biodiversity loss, and the increased rate of global warming derived from fossil fuel combustion. Ultimately, the ‘Shakespearean wild’ represents a prelapsarian fantasy, a wishful reality wherein the earth is uncorrupted by the dominion of machines. Fundamentally, Shakespeare’s controlling portrayal of Man’s attitude to ‘wild and cruel nature’ alongside womanhood in both The Tempest and King Lear aids in promoting the existence of the contrary.

Although women and nature are both portrayed as dominating forces out of the circle of a patriarchal society, in King Lear, Man’s insignificance in the face of wild cruel nature is brought to light. Conversely, The Tempest showcases male power and supremacy as the central male figure, Prospero, dominates both the wild nature and untamed island he inhabits, and rules over his daughter Miranda.

11

Classics

Although gender fluidity appears to be a newly formed concept within the 21st century, intersex people have been depicted in art since classical antiquity. Intersex people have been depicted in the form of pottery and statues for thousands of years. We will be analysing an Italo-Greek Oil Flask (c. 340 BCE) and the Sleeping Hermaphrodite (2 AD) in order to find a direct link between the visual language in these works and the myth of Hermaphroditus and Salmacis in Ovid’s Metamorphoses (8 AD). We will explore how the visual elements of the artworks are used to incite ideas and emotions within the viewer and to what extent these ideas are expressed within Ovid’s Metamorphoses. This epic poem contains a plethora of stories exploring themes of transformation as well as sexual violence. Although the quintessential attributes of the hermaphrodite can still be seen through Ovid’s Hermaphroditus, he creates a myth to give this figure a narrative, enabling him to ‘fill the void with a memorable aetiological story’. Ovid’s far more aggressive overtones provide a contrast to previous depictions of Hermaphroditus, for instance that of the Oil Flask and Sleeping Hermaphrodite statue.

In Ovid’s Metamorphoses’ retelling of Hermaphroditus and Salmacis, he describes how Hermaphroditus, son of Hermes and Aphrodite, was seen bathing in a pool of water as a boy by the naiad Salmacis. The naiad ‘was inflamed with desire for his naked form’ and jumped into the pool in an attempt to force herself onto him. Ovid describes how ‘she held him to her, struggling, snatching kisses from the fight’, creating an aggressive, unconsensually sexual atmosphere. Whilst she attempted to hold him to her, Salmacis prayed to the gods to never be separated from Hermaphroditus and so the gods intertwined their two bodies into one, creating ‘a two-fold form, so that they could not be called male or female, and seemed neither or either’. Hermaphroditus then emerges from the pool as an intersex person and prays that any man who enters the pool thereafter should have a similar fate. This subversion of sexual violence involving a female aggressor is uncommon both to the contemporary Roman readers and to a modern reader as well. However, the stereotypical act of male domination is still conveyed as Salmacis completely loses her name and her identity in joining together with Hermaphroditus. She is half of a body whilst Hermaphroditus retains the entirety of his persona.

As previously mentioned, the visual representation of Hermaphroditus significantly precedes that of Ovid’s literary depiction. The presentation of Hermaphroditus differs in many ways: he may be shown clothed, nude, standing up, lying down, peaceful or in a struggle. These different versions of Hermaphroditus have been grouped into three main categories. The figure is often shown through what is known as an anasyromenos depiction. This involves Hermaphroditus physically pulling his clothes down in order to reveal his dual sexuality, and in doing so, allowing the viewer to identify him. Examples of anasyromenos depictions can be seen as early as the 4th century BCE and they lend themselves to a common perception of Hermaphroditus as sexually provocative for the onlooker. However, this version of Hermaphroditus provides no indication as to his journey, both before and after this revelation. Therefore, many artists have chosen to show Hermaphroditus in what has been named a struggle-group depiction. This style, as the name suggests, shows Hermaphroditus involved in a physical fight with another being, one that is often shown as a satyr. In this way, the

viewer

To what extent is there a direct link between the descriptions of Hermaphroditus in Ovid’s Metamorphoses and the visual language of the Sleeping Hermaphrodite of the Louvre?

Amy Taylor (NHEHS)

Alisha Ossman (NHEHS)

12

Antonio da Silveira Pinheiro (Harrow) Jiho Ro (Harrow)

becomes more involved in the actual story of Hermaphroditus and they are, as Robert Groves suggested, ‘immediately plunged into a narrative’. The last version of Hermaphroditus in art, and the one shown in the Louvre’s Sleeping Hermaphrodite, is the Borghese type. This was hugely well known and popular in antiquity, perhaps because of the manner in which it invites the viewer to experience some sort of revelation alongside that of Hermaphroditus. In Borghese depictions, the statue initially appears female until the spectator walks around and finds the male genitalia, which in turn allows them to identify the sleeping figure. Furthermore, these depictions of Hermaphroditus can be seen in ancient literary versions such as an inscription found on the remains of a wall in Halicarnassus. In this, it is stated that Aphrodite named Salmacis as the nymph who nursed and took care of an infant Hermaphroditus, making no mention to the predatory or sexual elements in Ovid’s work. The two were

said to join together but much more out of choice than force on Salmacis’ part, and emphasis is placed on Hermaphroditus embodying the idea of marriage in that he unites man and woman. For this reason, works showing Hermaphroditus are often found in domestic settings, whether that be in a garden or on oil flasks.

Many links can be drawn between the Sleeping Hermaphrodite and Hermaphroditus as he appears at the start of Ovid’s myth. Ovid notes that Hermaphroditus, before being attacked by Salmacis, ‘did not know what love was’, showing his naive innocence. Additionally Hermaphroditus is referred to as a ‘puer’ (boy) as opposed to a young man, further highlighting his innocence and vulnerability. The Sleeping Hermaphrodite similarly evokes a sense of vulnerability by showing Hermaphroditus asleep. The depiction of a Borghese statue as opposed to more active, violent hermaphrodite statues emphasises the artist’s choice to show a peaceful

Ovid’s far more aggressive overtones provide contrast to previous depictions of Hermaphroditus, for instance that of the Oil Flask and Sleeping Hermaphrodite statue.

13

The Italo-Greek Oil Flask seems to draw more links between the sexual aspects of Ovid’s myth as opposed to more sympathetic elements.

image. The nude depiction of Hermaphroditus also creates a vulnerable portrayal of him as he lies exposed and unaware of his surroundings. The Borghese Gallery notes how the statue is ‘seeming to be both innocent and troubled’. Despite the troubled look of the statue, the Sleeping Hermaphrodite does not overtly allude to a violent struggle which Ovid chooses to focus on within his story as Salmacis grasps Hermaphroditus, ‘struggling, snatching kisses from the fight’. Hermaphrodite statues were generally placed in domestic Roman spaces, specifically gardens. Through putting them in a domestic setting, it appears as though Romans were attempting to normalise intersex people or to display the importance of equal male and female dynamics within the home. This can be reflected within Ovid’s portrayal as he describes how the two became a ‘two-fold form’, highlighting the complete merge of masculine and feminine. Additionally, Ovid appears to create an

unnatural, man-made pool as the setting for his story, since he notes that the pool contained ‘no marsh reeds round it, no sterile sedge, no spikes of rushes’, alluding to the gardens within which Hermaphrodite statues were commonly found. Due to the fact that Hermaphrodite statues were found in gardens, the viewer was expected to move around and encircle the statue when looking at it. The front of the statue shows the back of the depicted figure so the viewer approaches the statue from ‘behind’, forming the impression of a purely female body. The overwhelmingly feminine depiction of the Sleeping Hermaphrodite contrasts with Ovid’s Hermaphroditus who begins the story as a boy and is then forcibly feminised with a description of how ‘his limbs had been softened’. Additionally, Hermaphroditus retains his identity and consciousness after his transformation, showing an overall masculine figure who has obtained an intersex body. Since the viewer would have to move around to see the phallus of the statue, a simultaneous sense of shock and erotica is explored within them upon realising

the figure is a hermaphrodite statue. This is an idea emulated within Ovid’s myth as the reader could be positioned in the role of voyeur, experiencing both dismay and pleasure from Hermaphroditus’ sexual assault. It is clear that many aspects of the Sleeping Hermaphrodite can be seen within Ovid’s depiction.

The Italo-Greek Oil Flask seems to draw more links between the sexual aspects of Ovid’s myth as opposed to more sympathetic elements. The Oil Flask is the oldest of the three artefacts, having been created circa 340 BCE, so it is significantly separated from Ovid’s notion of intersexuality. It depicts Hermaphrodites as an Erotes, an Ancient Greek god of love and desire. Hermaphroditus is also shown chasing a hare, a symbol of fertility and sexual desire. This forthright sexual characterisation contrasts with Ovid’s innocent descriptions of Hermaphroditus who ‘did not know what love was’.

Additionally, Hermaphroditus is given more agency on the oil flask whereas Ovid depicts him as a victim of sexual violence: ‘struggling, snatching kisses from the fight’. This hypersexualised portrayal of Hermaphroditus aligns more with Ovid’s characterization of Salmacis, showing her intense sexual desire and pursuit of an innocent boy.

Hermaphroditus’ wings portray him as a more mythological, dehumanised character which differs from Ovid’s more human, empathetic portrayal. Through depicting Hermaphroditus on an oil flask, which would have been used to store perfumes, a product of desire and seduction, he is further associated with sexual desire.

14

The Sleeping Hermaphrodite similarly evokes a sense of vulnerability by showing Hermaphroditus asleep.

In conclusion, it is evident that there are many links between the descriptions in Ovid’s work and the visual language of the oil flask and statue. All these works present the character of Hermaphroditus; however, in Ovid’s descriptions he is able to create more of a story to explain his origins. The oil flask presents Hermaphroditus as a much more sexual figure by depicting him as an Erotes, whereas the sculpture, though seemingly provocative once the viewer has circled round, allows the audience to sympathise more with Hermaphroditus sas a resigned victim. The character of Hermaphroditus has been present in all sorts of work for thousands of years, meaning there are multiple similarities but also differences present in these different artworks.

15

Law & Philosophy

Despite the substantial geographical distance between the locations of the Two-Spirit Indigenous People of North America and the Hijras in India, they nevertheless share many significant and powerful correlations. Indeed, the terms ‘Two-Spirit’ and ‘Hijra’ are both used to broadly describe natives who performed a ‘thirdgender’ role in social and ceremonial aspects in their respective communities. During the age of colonialism, both imperialist expansion and European settlers have confronted the Two-Spirits and Hijras, whose behaviour, customs and values were placed under great scrutiny and analysis. Their traditional roles were in direct contrast with Judeo-Christian values and as a result, these natives were associated with transgressive gender behaviour and non-reproductive sexual activity.

However, since the 20th century, gender theorists and LGBT scholars now place greater emphasis on the spiritual importance of these people in indigenous cultures and have produced studies in order to separate them from the racialized and heteronormative modes of philosophy of colonialism. It is with this in mind that we researched and compared the original social environment of the Two-Spirit people and the Hijras, their legal framework and standing, and finally their perception by settler colonialism. ‘Two-Spirit’ is a modern term coined in the 1990s to describe natives in North American tribes who fulfilled a traditional third-gender role in their cultures. An anonymous traveller report in 1825 described ‘men who assumed the dress and performed all the duties of women and who lived their whole life in this manner’.

The social and legal frameworks around the Two-Spirit Indigenous people of North America and the Hijras of India, and the impact of colonialism on the perceptions of these groups.

Angelina Koval (NHEHS)

Chloe Papageorgiou (NHEHS)

Harry O’Shea (Harrow)

16

Hansen Han (Harrow) Alonso Fontana (Harrow)

Originally, these people were referred to as ‘berdache’, a word of Arabic etymology, at the time, with negative connotations associated with sodomy and pederasty. By the end of the 18th century in North America, this word became a way to both denigrate and besmirch general homosexual behaviour. As a result, the word ‘Two-Spirit’ has gradually replaced ‘berdache’, now deemed to be offensive and a by-product of colonial heteropatriarchy.

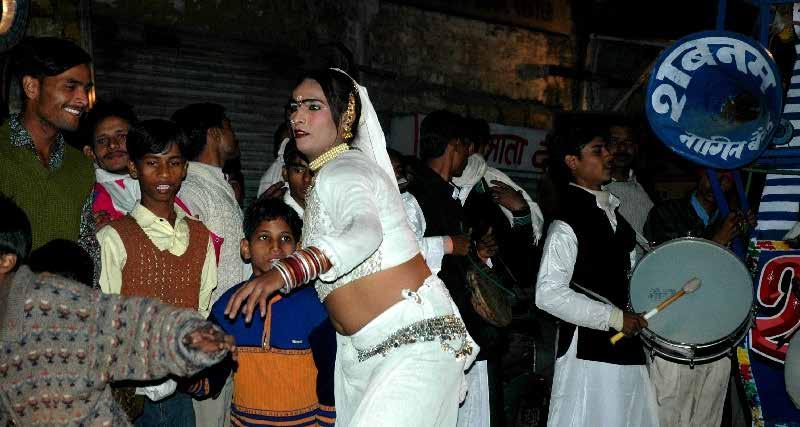

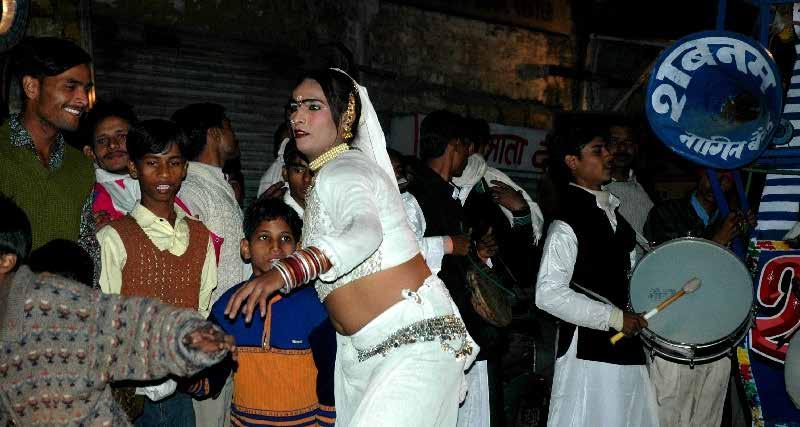

The term ‘Hijra’ is derived from the Semitic Arabic word ‘hjr’ meaning ‘leaving one’s tribe’ and is used to describe eunuchs, homosexuals, bisexuals and transgenders. Although people define the Hijras as a ‘third sex’ as they are neither man or woman, the Hijras themselves believe this is not a satisfactory designation, claiming that a third sex is seen as compromising both female and male sexualities. Therefore, every fundamental description of Hijras is inadequate, gaining the title of ‘Not This, Not That’. All hijras dress in ‘saris’ or the ‘salwar kameez’ as they call them, garments common to women in North India. Very few have been observed wearing men’s clothes, and men try to imitate females through wearing bras (padded or stuffed), imitating women’s walking, and taking female names upon initiation.

emblematise ‘universal fertility’, in a similar fashion to how the impotent Hijras can confer such aforementioned blessings. Simultaneously, the Hijras’ ‘inexorable power of the reproductive process is displayed within their ability to inflict curses as another ‘auspicious moment’: marriage ceremonies.

Indeed, the terms ‘Twospirit’ and ‘Hijra’ are both used to broadly describe natives who performed a ‘third-gender’ role in social and ceremonial aspects in their respective communities.

To commence our investigation, we first sought to compare the similarities and dissimilarities in the social roles of Two-Spirit Indigineous People and the Hijras. The unique role of Hijra people within religious ceremonies derives from their supposed ability to bless or curse. As described in Vinay Lal’s essay Not This, Not That, they wield the ability of ‘conferring blessings and, complementarily, inflicting curses.’ At the birth of a male child, it is believed that the Hijras are able to bless the child with fertility, leading to a healthy progeny. This ability supposedly originates within their identification with Shiva, the third God of the Hindu triumvirate, who ‘breaks off his phallus and tosses it aside’ to

Lal states that ‘the bride’s face must not be open to the gaze of Hijras, since the curse of infertility .. may fall on her.’ To contrast these two populations, it is important to realise the contradistinction between the social functions of female-bodied and male-bodied members of the TwoSpirit Indigenous People. Historically, female-bodied members typically took on roles as chiefs, councillors, traders, hunters and prophets, whereas male-bodied members would be involved in conducting morning rites, acting as healers, conveying oral traditions and as mentioned in Gregory D. Smithers’ article Cherokee “Two Spirits”, carry provisions for and retrieve fallen warriors from battle and ‘attach the deceased body to “stout poles”’. This role carries large importance, as in other south-eastern native societies the task of tending to the recently-deceased was reserved for those who were considered to be ritually significant. Perhaps the most contrastable social role between these two populations can be derived from the male-bodied Two-Spirit indigenous people’s role of arranging marriages and conferring lucky names on children. From this insight, a conclusion can potentially be drawn that the Hijras possess a more significant social role, as they are believed to actually confer blessings of fertility or inflict curses themselves at ceremonies, rather than merely attribute a lucky name and arrange marriage ceremonies.

To understand why the social and legal frameworks surrounding the Two-Spirit Indigenous people and the Hijras exist as they are, it is integral to navigate back to how the two groups were marginalised and completely

17

mistreated due to colonialism, centering around the idea that as stated in Sujata Moorti’s essay A Queer Romance With The Hijra, ‘Gender is uniquely a Western Concept produced by society.’ Subsequently, both groups underwent demeaning abuse, through violence and social isolation, imposed by colonisers who struggled to fit the notion of reaching beyond the gender binary into a Western, Christian and maledominated societal model. This Christian belief which repressed both groups is a similar aspect which diminished the beliefs of both groups; in the Two-Spirit community, settlers used words such as ‘hermaphrodite’ and ‘sodomite’ with completely negative medical and moral connotations which are seen to be consistent with contemporary European Judeo-Christian beliefs and implementing Natural Law. Similarly, the British empire which colonised India had a ‘moral and religious mission’ present to protect Christians from the corruption that they believed came from the Hijras. By utilizing biopower, the British regulated the Hijras by criminalising carnal intercourse ‘against the order of nature’ (which was not illegal before the British arrived); the Hijras were considered ungovernable and marginalised, often were associated with being prostitutes, addicted to sex with men and a general multifaceted threat to colonial authority. Moreover, colonial Britain classified Hijras as a criminal tribe under the

Criminal Tribes Act in 1871, perceiving the Hijras through the eyes of filth, disease and general contamination. Furthermore, both groups similarly were often vulnerable to violence and police intimidation, the concept being mirrored in the treatment of the Hijras, who attempted to survive the attempts made by the British to eliminate them by evading the police; according to Dr Hichy in the BBC article How Britain tried to ‘erase’ India’s third gender by Soutik Biswas, the Hijra became skilful at law breaking and keeping on the move. Additionally, Dr Hichy mentions that the police increased surveillance of the community, compiling registers of personal details in order to ‘ensure that castration was stamped out and the Hijra population was not reproduced,’ taking away children from households and completely obliterating families. Not only did the British fear the act of castration itself, but opposed the idea of a Hijra cohabiting with another man due to ‘accepted’, contemporary family structures. This concept can also be seen in how the Two-Spirit people were subjugated and judged by Eurocentric standards. As mentioned in the essay, Self-determination of identity: two-spirit natives and federal Indian law by Tara Wilson, ‘Female power in native society as interpreted by Europeans was a reflection of the inadequacy of Native American men’, particularly in the case of a man adopting a woman’s role; the colonists were

outraged as they ‘could not envision a masculine pursuit more splendid or noble than war.’

Fundamentally, both US and Indian legislation covertly, and explicitly, suppress the flourishing of Two-Spirit and Hijra peoples, stifling the expression of the critical values of each respective community. While the Right for Transgender Persons Bill of 2016 does, indeed, declare many forms of discrimination against Hijras to be illegal it, disconcertingly enough, traps them within further purview of the state’s disciplinary and punitive force. The denigrating, ill-founded disregard for core Hijra practices - such as challa mangnademonstrated within the bill conveys the general absence of ardent comprehension of Hijra conceptions of personhood and kinship. Further complications arise in the Rights of Transgender Persons Bill of 2015, which subtly includes the necessity of a ‘transgender certificate’ - a tacit introduction of formal identity policing which defies the constantly shifting criteria for a Hijra. Similarly, this rejection of the free-flowing, fluid identity of Two-Spirit peoples is evident in US legislation. At the crux of these legal frameworks is a perturbing reminiscence of colonial ideals, as evidenced by U.S v Kagama and Lone Wolf v Hitchcock, which established a guardian-feudal relationship; tribes ‘are the wards of the nation,’ and ‘dependent on the United States.’ This legal subjugation of tribes evokes countless complications regarding a lack of funding to enforce the rule of law and exploitation of the law itself. These flaws facilitate the

18

The unique role of Hijra people within religious ceremonies derives from their supposed ability to bless or curse.

overlooking of critical obstacles in expressing Two-Spirit identity, namely gender equality and child sovereignty, as explored by Tarah Lynn Wilson. Alarmingly, 84.3% of American Indian/Alaskan Native women have experienced violence in their lifetimes, with ‘Two-Spirit women [being] more likely to be sexually and physically assaulted than heterosexual aboriginal women and white lesbian women’; hence, the shortcomings of legal frameworks undermine gender fluidity as it is inescapable that Two-Spirit peoples risk their liberties in occupying an inclusive identity. Regarding the lack of child sovereignty, in 2011 it was estimated that approximately 95% of the tribal population experienced sexual abuse as children. As such, child abuse is detrimental to the expression of two-spirit identity as the violent dynamic between parent and child denies the latter to independently develop their identity beyond the expectations of their abusers. It could be argued that while both US and Indian legislation reinforce troubling

colonial systemic issues of racism and sexism through their shortcomings, the latter, albeit more optimistic on first glance, subtly but actively creates new precedent for further repression of the Hijras. Ultimately, it is evident that both Hijra and Two-Spirit notions of ambiguity and inclusivity are outright repressed, or, at the minimum, struggle to coexist with current legal frameworks.

The Hijra and Two-Spirit people are two distinctive communities that find themselves obscured and isolated by colonial principles that persist in being manifested in contemporary legislation. The pursuit of their respective communal roles has historically branded them with a denigrating societal status notwithstanding of their spiritual significance. Their nonconformity to colonial, heteronormative principles has discarded them to the fringes of society, although one can only hope that a more attentive contemporary approach, briefly displayed in legislation, will encourage these remarkable communities to flourish.

Fundamentally, both US and Indian legislation covertly, and explicitly, suppress the flourishing of Two-Spirit and Hijra peoples, stifling the expression of the critical values of each respective community.

19

Eight ingredients for a successful symposium

Make it meaningful

The best academic projects are interesting in and of themselves. It can be tempting to try to simplify topics, or search through conference materials from other schools, but redoing things which have been done before is never as energising and exciting as trying to chart new ground. Things which are genuinely interesting to the adults in the room will be interesting to the students as well.

Make it personal

The best encouragement that any student can have to really delve into topics beyond the syllabus is by being inspired by someone whose passion for the subjectmatter is self-evident, and whose enthusiasm is contagious. It is hard to enthuse about something which one knows little about, and therefore the best projects will be shaped around personal areas of specialist interest from the educators involved.

Blur boundaries

The excitement and relevance of a project can really be heightened by encounters with professionals and academics beyond the school boundaries. For instance, real anaesthetists speaking from their experience, or real scholars at universities helping students understand why their contribution is genuinely meaningful.

Over specify for creativity

It can seem like a kindness to give students “freedom”: to generate their own questions, find their own sources, have flexibility with word counts, make decisions about their own slides. However, giving strict guidelines about how to write things, giving out the sources, and giving clear instructions about timings and slide decks, can instead channel student creativity into solving the problems at hand, leading to much more inspiring outcomes.

3

20

1 2

4

Smooth IT

Friction in information technology is a frustrating waste of time. By putting all electronic resources into a central folder, linked to with QR codes, including shared documents which students can populate with articles, it is easy for teams to collaborate. Creating a single shared slide deck avoids awkward transitions between groups during the presentations. However, making things feel and look easy requires considerable investment of time and energy at the back end: thankless work, but it does pay off!

Find uplifting settings

There can be huge value for students in having access to wonderful settings. Booking The Royal Society was a large, but not extravagant, expenditure shared between the schools; it added immeasurable value in terms of student experience, and provided wonderful photographs to inspire people from both schools.

Appeal on all levels

When motivating students to take part, emphasise all the angles: the project needs to have intrinsic value as an academic pursuit, but also it can be appealing to students to know that the project will – for instance – give them access to expert advice on sophisticated projects which they can then put to use for their university applications. And also, students will be motivated by point 8 below…

Remember to have fun

Developing scholarship is a serious business, and rightly so, but there is – within this – space for laughter (icebreakers about rabbits), mischief (other icebreakers… ), and dinner parties (two, in this case) along the way. “All things please the soul, but these please the soul well”

8 7 6

21

5

History

The historical context of women’s shifting place in French society between 1852 and 1900, and its link to Manet’s 1882 painting A Bar at the Folies-Bergère.

Mairi Gillespie (NHEHS)

Saira Backhouse (NHEHS) Henry Rowntree (Harrow) Oscar Gleason (Harrow)

Mairi Gillespie (NHEHS)

Saira Backhouse (NHEHS) Henry Rowntree (Harrow) Oscar Gleason (Harrow)

At first glance, Manet’s 1882 painting A Bar at the Folies-Bergère (Figure 1) appears as a symbol of decadence and luxury, the centrally placed barmaid surrounded by commercial goods such as champagne and fresh fruit, and backed by a landscape mirror which reflects the dazzling lights and packed crowds watching the trapeze. However, when one delves a little deeper it is clear that the painting is not as simple as it first appears: the barmaid standing at the bar wears a weary expression to face her customer, a somewhat intimidating moustachioed man. Everything in this painting directs you to the subject’s face; the triangles formed from her arms and the beer bottles all lead the viewer back to the same tired face. But why does she look so downcast? In order to ascertain the painting’s true meaning one must explore the ideals of the time, the politics within society and above all the attitude to women that has resulted in

such a jaded visage.

The brasseries à femmes were extremely successful and became a significant mainstay in Parisian society by the 1880s

The increasing commodification of women during the latter half of the nineteenth century greatly impacts how one views A Bar at the Folies-Bergère due to its stance on the objectification of women and the growing consumerism in Paris. The brasseries à femmes were extremely successful and became a significant mainstay in Parisian society by the 1880s - with 200 bars employing 1,000 women by 1888, compared to the significantly fewer 130 bars in 1879 (Clayson, p141). The rapid growth of these brasseries à femmes caused them to be a popular focus for artists after the Universal Exposition of 1878 (Clayson, p141). The Universal Exposition was a celebration of consumerism and French culture after the Franco-Prussian war, where one could see new technology being exhibited, so this increase of consumerism coincided with the growing perception of women as a commodity to be bought. In

22

the brasseries à femmes, women worked as barmaids and encouraged men to become drunk before usually inviting them to a nearby hotel, making the brasseries a symbol of the prevalent commodification of women during this time. The barmaid’s profession is made explicit in the painting through Manet’s use of the oranges, a symbol he habitually used in his paintings to depict prostitution.

Within Manet’s painting, the woman’s firmly placed arms on the table highlight her position among the other items to be bought, which emphasises her place in society as an object to be displayed. The barmaid is, as T.J. Clark asserts, ‘both a salesperson and a commodity- something to be purchased along with a drink’ which becomes extremely evident when analysing the triangular shaped flowers adorning her dress (1999). These mirror the red triangles on the Bass Pale Ale bottles by her arms, which was a corporate symbol of the manufacture of goods that were becoming increasingly prominent in a commercialised Paris. With his placement of the red triangle on the barmaid’s dress, Manet is signalling that she is a cheap commodity to be bought and sold by the men who visited the Folies-Bergere (Grovier, 2019). In the mirror, the barmaid’s leaning forward and the ‘intense gaze of the man, cast a suggestive closeness toward the barmaid’ which allows him to exercise ‘power over its female object’ (Iskin, 1995). This objectification of women, closely linked with the prostitution sometimes occurring in these places of business, could be linked with the rise of the department store in Paris. They started displaying products to catch the attention of the shoppers, rather than storing them in back rooms as had been done previously, and the obvious commodification of the barmaid reflects this (Iskin, 1995). Therefore, Manet could be using this painting to draw attention to the commodification of women that was occurring during this time.

One’s understanding of Manet’s painting could also be informed by the recognition of female suffering during the latter part of the nineteenth century, as women’s rights became a topic that was less overlooked. An example of this can be found when looking at French society’s attitudes towards women. Throughout the nineteenth century, the rights of women scarcely improved. For two millennia, Roman legal tradition prohibited women from having any control over their bodies, offspring and lives, rendering them effectively powerless (Waelti-Walters and Hause, 1994). The authoritarian regime of Napoleon III, which ended only a decade before the creation of A Bar, did little to change this (Waelti-Walters and Hause, 1994). Even progressive thinkers such as Pierre-Joseph Proudhon could state that women were only befitting of the roles of ‘housewife or harlot’ (1846), clearly showcasing the restrictive society women were trapped in and unable to escape. Throughout his works, Manet manages to encapsulate the female reaction to the patriarchal oppression they faced regularly. In A Bar at the Folies-Bergère, we can look at the ambiguous

expression of the barmaid to decipher her inner thoughts, interpreting it as tired and melancholic. Considering the environment the woman lived in, we could read her sombre look as a visual representation of the weariness late nineteenth century French women would experience. Her stare is unsettling, and though she seems to be interacting with a customer seen in the mirror reflection, she seems almost completely absorbed by her own thoughts. As the viewer, we are the only ones able to see her inner turmoil in the way she is unable to hold the customer’s gaze. This could link to the fact that even as women became employed during this time, they were still in the business of servicing men just as the barmaid is. Her entire figure seems to signal a shift in reality as her form is clearer and holds a controlled energy that contrasts to the frantic, excitable tone of the bar’s audience seen in the mirror reflection. The buzz and movement of the background appears almost muffled as the viewer’s gaze shifts to the barmaid, and we find that her presence dominates the scene.

Compared to the looser, textural brush strokes of the background, the barmaid is a more tangible presence in the painting, standing out from the busyness of the scene. One could infer a sense of defiance from the barmaid; the viewer is forced to pay attention to her and not her gentleman customer. Manet could be giving voice to the overlooked part of Parisian society, allowing us to see into the mind of this silenced

facial

Image Caption

One’s understanding of Manet’s painting could also be informed by the recognition of female suffering during the latter part of the nineteenth century

23

character. While women in French society were traditionally relegated to domestic duties, Paris’ significant architectural overhaul by way of Haussmannisation in 1853 greatly remodelled the position of women in both the public and private eye. The rapid emergence of the middle class created a kind of ‘new women’, exposing domestic femininity as a choice rather than a destiny. In this regard, Paris particularly saw a drastic decrease in marriages and children per household as women sought autonomy, claiming their own stake in a city that presented so much new-found opportunity. By 1860, about sixty percent of women were active in the labour force (Zijdeman, 2014), assuming jobs primarily in factory work or prostitution. Similarly, the inception of the café-concert, and its speedy development as one of the favourite pastimes of the middle class, also provided women with roles not only in entertainment, but also required a significant number of women to assume positions as hostesses or barmaids - as seen in Manet’s painting. Furthermore, the outfit of the barmaid is particularly descriptive of

her relation to the proletariat. Her ungloved hands, when contrasted with her voguish dress and tight corset, appear very unfashionable - seeing as gloves were a staple of the contemporary bourgeois style. Thus, Manet depicts a working woman’s hands, a stark contrast to the figures in the painting’s reflection, which not only serves to alienate her from her surroundings but also introduces a kind of sexual ambiguity. In this way, by introducing

a divide between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat, Manet introduces a kind of scorn for the lower class, which is particularly evident in his skewed use of perspective to accentuate the partition. Thus, by fragmenting reality through his reflection, he manages to create far more distance between the two classes of women. Furthermore, the depiction of the barmaid herself disconnects her even further from her surroundings. Her expression is strange and desolated yet far from emotionless, a complete juxtaposition with the sparkling “world of commodities” that surrounds her. In this manner, Manet not only presents an autonomous idol of the working

24

The rapid emergence of the middle class created a kind of ‘new women’, exposing domestic femininity as a choice rather than a destiny.

class, but also scorns her by accentuating her lack of belonging in the scene.

Ultimately, it is clear that whilst the painting at first appears so bright and decadent, after reading into the situation surrounding the era it is clear why our unnamed subject looks so dejected. Years upon years of suffering, being treated as a mere object and thought to have no more purpose than, say, a domestic servant, has worn down upon her. Her position as (likely) a prostitute only makes the portrayal more sorrowful as one realises the trials and tribulations of such a profession and the dangers it brings to the vulnerable women who have no choice but to take up such a profession. Therefore, having studied the attitudes of the time we have attained a greater understanding of the painting, not as a panegyric work designed to sing the praises of Paris’s golden age of the ‘Belle Epoque’ but rather as a sardonic take on said era, injecting an element of realism into a highly romanticised and glamorised time in French history. By portraying such a woman Manet fulfils his role as a disruptive impressionist, shining a light on the faults of the era’s legacy by portraying an ordinary, workingclass woman who is simply doing her job whilst being elevated as a medium to stand for so much more.

25

Politics & Economics

Low (NHEHS)

Zara Talbot (NHEHS)

Adi Inpan (Harrow) Iyanu Ojomo (Harrow)

Low (NHEHS)

Zara Talbot (NHEHS)

Adi Inpan (Harrow) Iyanu Ojomo (Harrow)

In this article, we will be talking about the role claimed for microfinance in tackling the poverty of women, utilising multiple sources which we have used to examine the concerns raised about it. Firstly, microfinance is a path towards financial inclusion through the lending of small loans without collateral to the poor, which can also be known as microcredit. In more rural areas, developing countries may use these microfinance schemes. There can be positive and negative effects of microfinance loans tackling the absolute poverty problem of women. In short, lending small amounts of money hinders progress made and undermines people by saddling them with unsustainable cycles of debt. However, small loans are one of the best ways to empower women where the aim is making sure the necessities are provided. Economic empowerment is the transformative process that aids women and girls in transitioning from having limited power, choices and a voice in the economy to obtaining the skills, resources and opportunities

needed to compete in markets and benefit from economic gains. The general aim of microfinance is to increase female economic empowerment which reduces poverty although sometimes causing more of a hindrance than a benefit, especially directed towards women.

A view that can be stressed is that there is a possibility of sustainable microfinance programmes that will empower women worldwide. Of the 139 million MFI (Microfinance institutions) borrowers worldwide, 80% are women and studies show that they are the ideal buyers.

The role of microfinance in tackling the poverty of women, and concerns around this.

Katie

26

An ideal buyer would be someone who is a perfect consumer towards your business having faultless characteristics for the product. A large majority of women are subject to subordination by patriarchal societies and are reliant on their male counterparts and thus the introduction of microfinance and micro-credit institutions in the last few decades has lifted many women out of poverty. This could be seen as problematic and slightly backhanded. Why should women need more empowerment rather than men? Microfinance institutions are also exploiting women for their own economic gain which is immoral. They say that they are helping women in poverty, whereas in reality it is all for selfish reasons to grow their companies. In some cases, firms are hoping that women overspend in order to take out more loans leading

Female economic empowerment provides diversification and economic resilience to the global market which is significant as it allows inequality to be reduced...

towards a larger profit. Saying this, MFIs are increasingly helping those impoverished to start small businesses, break cycles of poverty and boost the economy of local communities, reaching out mainly to rural communities where borrowers know each other. This means that a failure to repay loans will hurt their community. The overwhelming repayment amount of these loans, demonstrated through the 97% repayment rate for the Grameen Bank, shows how MFIs are aiding women in becoming more financially cautious and independent. The extent to which this empowers women is wide-reaching, since women were able to lead groups rather than men. An additional long-term benefit of how microfinance affects female empowerment stems from the fact that 90% of their income is spent on family needs, compared

27

to only 35% of men’s incomes. This will lead to higher educational attainment for their children which can double or triple their income in the future, having a later effect on the country’s economy. Female economic empowerment provides diversification and economic resilience to the global market, which is significant as it allows inequality to be reduced and increases aggregate demand in the economy as women are more inclined to have increased spending power. Furthermore, micro-credit allows for the kinds of investments and benefits for gender equality to occur through avenues of financial independence, thus having a long term benefit on the economy, shown through the fact the global GDP has doubled to around $160 trillion partly due to micro-credit.

Usually, a standard loan seeker would have to seek permission from the bank, who would review their eligibility. However, MFIs are different from other loan programs because clients are not required to receive collateral to receive loans. They work by allowing people who would not usually qualify for loans to receive credit,

and they are very client-friendly, as they reach out to their clients and provide them with loans and receive payments, and so a missing market for entrepreneurs is filled. After this, they can invest in any goods and services to satisfy their daily needs as well as being able to set up small businesses. Many poor people have skills that can quickly become an income-producing activity. With small sums of money, they are able to purchase the inventory, supplies and tools needed to start or expand microbusinesses that range from weaving, sewing, reselling produce to catching and selling fish, and breeding livestock. Such small ventures can grow into vibrant community businesses and after this, MFIs usually follow up with them and monitor their successes with investments at weekly ‘centre meetings’, and mutual support systems strengthen their solutions. Grameem Bank, started by Nobel Prize-Winning Professor Muhammad Yunus, has been recognised as an ideal framework for other MFIs to learn from, and they are a successful example that led to a 50% increase in average household income with 9.6mn borrowers and a 97% repayment rate. However, there is still a risk that men in households may take

some of the loans, or even withdraw some of their income contribution due to overreliance on the microfinance loans.

Despite all the positive possibilities surrounding microfinance, there are some drawbacks when it comes to microcredit’s effect on lifting people out of poverty. Firstly, microfinance companies do not often reach the poorest of the poor. Most microfinance institutions are more successful at reaching those living just above and below the poverty line, or to put it another way, the wealthier poor. Those with a higher income are more willing to take the risks of investing in new technologies, which may in turn increase income. Poorer borrowers, on the other hand, often misuse the borrowed money, and often take out microloans to cover basic consumption needs rather than fuelling enterprises. This leads into a second problem which is based on the people and businesses microfinance companies intend to fund.

According to Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter, entrepreneurs are people of vision and creativity, who convert new ideas into successful business models or innovations through engagement in ‘creative destruction’ – which Schumpeter describes as the process of industrial mutation that incessantly revolutionises the economic structure from within, incessantly destroying the old one, incessantly creating a new one. The problem is most micro-

28

The problem is most microcredit clients are not entrepreneurs by choice and would gladly take a job at a reasonable wage if it were available.

credit clients are not entrepreneurs by choice and would gladly take a job at a reasonable wage if it were available. People often use funds for consumption rather than entrepreneurial investments, suggesting that there are other, non-entrepreneurial returns to these products. A study in the Philippines took place to analyse the way microloans were spent two weeks and two months after loans were disbursed; when asked directly, people often reported that they used loans for household consumption and to pay off their debt. One other problem that was found was that for-profit providers of microfinance have been accused of overcharging their poor customers. An example of this is a Mexican bank called Compartamos Banco, which is also the largest microfinance bank in Latin America.

Many randomised studies across a variety of countries found that there is no evidence that the loans have been lifting families out of poverty.

At the time of its IPO, Compartamos’s customers were paying interest rates of 94% a year according to The Economist. They also gave out tens of millions of dollars to key managers. The bank argues that these high profits have enabled them to serve all the customers they do, which is currently over 2.5 million clients, who would have had even worse financial options. They argue that banks like them are needed to occupy

the missing market of loans for ‘poor entrepreneurs’. Nonetheless, microfinance institutions should be ‘social businesses’ driven by social missions, focusing on maximising consumer welfare rather than profit. Evidence from India in 2013 suggests that relatively simple tweaks to micro-credit products can lead to short-run business investment and long-run profits. Many randomised studies across a variety of countries found that there is no evidence that the loans have been lifting families out of poverty. This has caused many to believe that microfinance is based on concept rather than facts, and so it has no real positive effect on women in poverty. This is therefore taking the attention away from more useful, more effective alternatives.

To conclude, we recognise that microfinance has achievements and benefits with short-term solutions immediately tackling poverty with lending necessities. However, the costs sometimes outweigh these benefits in the long run as microcredit loans create a larger problem where there are economic gains at a social cost. As MFIs are profit-seeking companies, they often overcharge poor customers while also not always reaching those suffering extreme poverty, showing the drawbacks of a profit-making business trying to aid the less fortunate as they will aim to seek an economic benefit which often leads to exploitation. The simple way to solve this problem could be to give goods and services rather than money so that people cannot invest into the economy and thus lose more money in cycles of endless debt. Other viable solutions are increasing the number of non profit organisations entering these areas to reduce poverty such as the Malala Fund and Equality Now, easing the levels of corruption that can often enter impoverished areas through MFIs. Although we can admit that traditional micro-credit hasn’t lived up to expectations, many companies and institutions are learning how to improve the system. However, it did lead to increased business investments and an increase in women’s economic empowerment through greater decision making power.

29

Medicine

Anaesthetic protocols for lower segment Caesarean sections.

The art of anaesthetics has been one of the greatest milestones and achievements in medicine that has affected many people around the world, largely owing to the founder of modern anaesthesia, William T.G. Morton. However, not all anaesthesia is widely accepted in all surgeries, especially when concerning a child, such as caesarean sections. More and more protocols have been put into place to ensure autonomy in surgeries, with informed consent being an indispensable part of it. In this essay, we will discuss anaesthesia, caesarean section, and informed consent to find the possible questions one may want the anaesthetist to answer.

Anaesthesia can be traced back to ancient times, being used by the Babylonians, Greeks, and Chinese, to name just a few. It has certainly evolved since then, leading to the use of cocaine, nitrous oxide, and chloroform. In modern anaesthesia, there are four main types offered, general, local, regional, and spinal and epidural. General anaesthesia is a state of controlled unconsciousness in which the patient feels nothing and has no memory of what happened when anaesthetised. A combination of intravenous drugs and inhaled gases is usually used. These drugs prevent the brain from responding to any sensory messages travelling from the nerve to the body. Local anaesthesia numbs a small part of the body, where the patient stays conscious but free

from pain. Regional anaesthetic is when a local anaesthetic drug is injected near to the nerves that supply a larger or deeper area of the body, and the area of the affected body becomes numb. Lastly, spinal and epidural anaesthesia is where anaesthesia is injected into the spine, numbing the lower body.

In the context of C-sections, spinal and epidural anaesthesia is generally used. The anaesthetist usually finds the gap between vertebrae at the bottom of the spine and injects the anaesthesia between the cavities. It anaesthetises the nerves in that region to supply the area of the abdomen that is cut by the surgeon. The upper body, however, is not affected, so the mother is awake and aware. There are complications associated with this, such as the physical injury when a needle is injected into the body, anaphylaxis, or simply by injecting too much anaesthesia, which may cause complications interfering with the mother’s ability to breathe. General anaesthesia is generally only used in an emergency C-section when the procedure becomes an emergency.

Informed consent is a medical process where the

Sia Patel (NHEHS)

Sia Patel (NHEHS)

30

Klea Alushani (NHEHS) Andre Ma (Harrow) Justin Lam (Harrow)

patient is informed by the medical staff in charge about the potential risks, benefits, long-term effects and process of the treatment. The medical staff are only allowed to proceed with the treatment under the acknowledgement and understanding of the patients themselves. There are a few elements to informed consent which must be followed to ensure safety and legality for both parties.

The first is the idea of disclosure. The patient must be informed about all the relevant information related to the procedure. If a patient is to undergo surgery involving anaesthesia, the medical staff are legally obliged to educate and inform them about the nature of it. The doctor must thoroughly run through the details of each type of anaesthesia, informing the patient about the risks and benefits of each. The patient must also be informed about the success rates and long-term effects on physical and mental health. The doctor must ensure the

patient feels safe and certain with the treatment plan. Lastly, the doctor must go through the cost of the treatments, ensuring the patient can afford the treatments without putting a financial burden on them in the future. Consent has not been fully given until all of the steps listed above have been ticked off.

The second element of informed consent is comprehension and understanding. The information addressed above must all be delivered to the patient in a way they understand fully. In some cases, doctors and patients will even bring along translators to make sure the patient understands the information thoroughly.

The third element of informed consent is the idea of competence and voluntary consent. It must be reminded that it is the patient’s legal right to choose the type of treatment according to their best interests; the doctor can recommend the treatment but is not legally allowed to coerce their preference. Before giving consent, the patient must also be sober and conscious, and not under the influence of substances or trauma from accidents involving neurological damage. Most importantly, the patient must be mature and above the age of 18 to ensure they are aware of what they are agreeing to. In the cases of teenagers and children, parents or legal guardians will proceed with the treatment that they believe is the best for their children.

Consent can be given in different ways after all these stages have been passed. It can be given in 2 major ways: verbal and in writing. A patient can verbally acknowledge the information given by the doctor in charge, for example, agreeing to an X-Ray or a

31

C-section. Consent can also be given in the form of written words. A common example would be a consent form which is signed before surgery.

There are differences shown between informed consent for male and female patients. Informed consent is a universal idea that doctors across the globe are obliged to follow. However, the idea of informed consent is neglected in many countries where the male gender is considered dominant, for example in Oman. Some existing laws and regulations ensure women’s rights are available and given. Such laws are also applied in healthcare and medicine. However, Oman is a very collectivistic and communal-focused country. It is a positive idea as it emphasises the idea of mutual support among family members; Oman has a strong sense of community spirit. However, the

culture may go against the idea of patient autonomy, particularly among female patients. Studies have shown that male patients of Oman follow a more independent route where they voluntarily choose and give consent to the treatment without the influence of others. On the other hand, female patients tend to have discussions with their family numbers before signing a consent form. There are also cases where the female patient’s father signs the consent form for her.

The NICE guideline for Caesarean birth outlines the provision of information for pregnant women being offered Caesarean sections. This includes offering evidence-based and accessible information that takes into account any personal, cultural or religious factors that could form part of the woman’s choices. This information includes the benefits and risks of

both caesarean and vaginal birth, factors that may mean that caesarean birth is required (for example the maternal age and BMI), and what a birth by C-section involves. This information allows the woman to make informed decisions and be prepared for any situation that arises during the pregnancy and birth.

Naturally, pregnant women may have many concerns regarding C-sections, which differ from concerns that may be had for other abdominal surgeries. This is because, during pregnancy, two people need to be taken into consideration - the newborn baby and their mother.

The first question that may be asked is why regional anaesthesia is preferred over general anaesthesia. Regional anaesthesia has been the option of choice for pre-planned, uncomplicated C-sections, as it does not require the use of a ventilator because the patient is still conscious. Under the use of general anaesthesia, the patient’s breathing is monitored by the anaesthesiologist as they are unable to breathe on their own. Regional anaesthesia also presents the benefit of allowing both parents to be present during the birth, allowing the parents to meet their newborn instantly.

Another question that may be asked is when regional anaesthesia is unsuitable. Despite regional

32

anaesthesia being safer, there are some instances where general anaesthesia should be used. For example, there may not be enough time during an emergency to administer regional anaesthesia and allow it to start working; regional anaesthesia may not numb the patient enough.

There may be queries over the side effects and risks of either type of anaesthesia. Headaches, backache, infection, and low blood pressure are reported side effects of regional anaesthesia; however, it has been shown that most anaesthesia-related deaths have been due to general anaesthesia. General anaesthesia is of higher risk than regional. Its side effects include sore throats, dry mouth, and nausea. The risks, in general, include aspiration of stomach contents (where vomit enters the lungs - which could be lethal), increased blood loss, and inability to insert an endotracheal tube for ventilation. General anaesthesia for C-sections has also been linked with poorer mental health; a study showed that ‘general anaesthesia in caesarean delivery was associated with a 54% increased odds of [postpartum depression]’. Suicidal thoughts are also exhibited to have been increased as well. This has been attributed to the fact that general anaesthesia ‘delays the initiation of mother to infant skin-to-skin interaction and breastfeeding, … [and] results in… postpartum pain,’ says Jean Guglielminotti, MD, PhD. Regional anaesthesia is therefore considered a safer option, presenting fewer risks and milder side effects.

The anaesthetist may also want to guide the pregnant woman through the preparation and preoperative testing that is required before using either general or regional anaesthetic for the C-section.

The anaesthetist may also want to guide the pregnant woman through the preparation and preoperative testing that is required before using either general or regional anaesthetic for the C-section. Before the procedure, general guidance to prepare for regional anaesthetic is to give an indwelling urinary catheter to prevent over-distension of the bladder. The woman should be informed of this beforehand. It is generally required that the woman does not eat or drink prior to the procedure, and so the anaesthetist should clearly inform her of this. The Association of Anaesthetists in Great Britain and Ireland recommends the minimum fasting periods (based on the American Society of Anaesthesiologists Guidelines) of 6 hours for solid food and 2 hours for clear non-particulate and noncarbonated fluids. However, it is important that the pregnant patients are not left for long periods without hydration and they may require IV fluids.

Another question the woman may ask would be about post-operative care. The woman would also want to be informed of the necessary medications and precautions she should take. Before the procedure, information on the different types of post-caesarean birth analgesia (pain-relief medications) should be given so that an informed choice can be made. This plays an important role in ensuring that the woman remains comfortable after the anaesthetic has worn off. The average stay in a hospital after a C-section is 3-4 days, and the woman should know what she can expect during this time.