To provide news and opinion to support professional growth and personal connections within the Berks County Medical Society community.

D. Michael Baxter, MD, Editor

Editorial Board

D. Michael Baxter, MD

Lucy J. Cairns, MD

Daniel Forman, DO

Shannon Foster, MD

Steph Lee, MD, MPH

William Santoro, MD, FASAM, DABAM

Raymond Truex, MD, FACS, FAANS

T.j. Huckleberry, MPA

William Santoro, MD, FASAM, DABAM President

Ankit Shah, MD

President Elect

Daniel Forman, DO Treasurer

Jillian Ventuzelo, DO Immediate Past President

T. J. Huckleberry, MPA Executive Director

Berks County Medical Society

2669 Shillington Rd,, Suite 501 Sinking Spring, PA 19608 (610) 375-6555 (610) 375-6535 (FAX) Email: info@berkscms.org www.berkscms.org

The opinions expressed in these pages are those of the individual authors and not necessarily those of the Berks County Medical Society. The ad material is for the information and consideration of the reader. It does not necessarily represent an endorsement or recommendation by the Berks County Medical Society.

Manuscripts offered for publication and other correspondence should be sent to 2669 Shillington Rd, Sinking Spring, PA 19608, Ste 501. The editorial board reserves the right to reject and/or alter submitted material before publication.

The Berks County Medical Record (ISSN #0736-7333) is published four times a year by the Berks County Medical Society, 2669 Shillington Rd, Sinking Spring, PA 19608, Ste 501. Subscription $50.00 per year. Periodicals postage paid at Reading, PA, and at additional mailing offices.

POSTMASTER: Please send address changes to the Berks County Medical Record, 2669 Shillington Rd, Sinking Spring, PA 19608, Ste 501.

CLUB Part III

Leader for Second Consecutive Year

website at www.berkscms.org and click on “Join Now”

THE COVER: Portrait of Dr. Samuel D. Gross (The Gross Clinic), 1875, Thomas Eakins (American, 1844–1916) - Gift of the Alumni Association to Jefferson Medical College in 1878 and purchased by the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts and the Philadelphia Museum of Art in 2007 with the generous support of more than 3,600 donors, 2007-1-1

Content Submission: Medical Record magazine welcomes recommendations for editorial content focusing on medical practice and management issues, and health and wellness topics that impact our community. However, we only accept articles from members of the Berks County Medical Society. Submissions can be photo(s), opinion piece or article. Typed manuscripts should be submitted as Word documents (8.5 x 11) and photos should be high resolution (300dpi at 100% size used in publication). Email your submission to info@berkscms.org for review by the Editorial Board. Thank YOU!

FASAM, DABAM Chief, Section of Addiction Medicine, Reading Hospital/ Tower Health President

Medical education has undergone significant transformation since I graduated in 1981.

Advancements in technology, shifts in healthcare priorities, and evolving society needs are the driving forces. From integrating artificial intelligence and virtual reality to emphasizing patient-centered care, these changes are reshaping how physicians are trained. The goal is to equip medical students with not only the knowledge and skills to diagnose and treat diseases, but to also give them the ability to navigate complex healthcare systems while providing patient-centered care.

I believe the most significant advance in medical education is the change from traditional time-based curricula to competencybased education (CBE). When I went to medical school, I learned basic sciences the first two years and then worked with attending physicians doing rotations through specific specialties during years 3 and 4. Learning focused on acquiring specific knowledge over a specific time. But CBE emphasizes the acquisition of competencies, rather than specific knowledge, allowing students to progress at their own pace. This more closely follows the demands of modern healthcare, where practical skills, critical thinking, and clinical reasoning are essential.

In a competency-based model, students are evaluated based on their ability to perform specific tasks, such as taking a history, performing a physical exam, or interpreting diagnostic tests. This model gives a student a more personalized learning experience. Students who excel in one area can advance more quickly, while those who need more time can receive

additional support. Ultimately, CBE ensures that graduates are better prepared to meet the demands of clinical practice.

Technology has also revolutionized the way students learn, with access to tools that improve the learning experience. One remarkable advance that wasn’t available to me is the use of simulation-based learning. This allows students to practice clinical skills in a controlled, risk-free environment. Mannequins, virtual patients, and virtual reality simulate real-life scenarios, allowing students to hone their skills before entering the real-life clinical setting.

For example, virtual reality allows students to immerse themselves in realistic surgical environments, where they can practice procedures, make decisions, and see the outcomes in real-time. These technologies not only improve technical skills but also help students develop critical thinking and decisionmaking. Furthermore, artificial intelligence can tailor content to individual learning styles, providing personalized feedback, and guidance.

Telemedicine has become an important aspect of medical training. As telehealth expands, medical students must learn to provide care remotely, using digital tools to assess, diagnose, and treat patients. Schools now incorporate telemedicine into their curricula, giving students experience in virtual patient interactions. Several colleagues and I were published in a medical journal as we demonstrated that telehealth patients in Addiction Medicine had retention rates as good as those seen in person. I humbly admit that our original hypothesis was that telehealth was not as successful as in-person treatment. Based

continued on next page >

continued from page 3

Active since 1824, the Berks County Medical Society has continually set the standard for medical excellence in our community. We are excited to have you as our guest at our 200th Anniversary celebration, marking two centuries of commitment to healthcare.

Join us for an evening of drinks, hors d’oeuvres, and discussions with elected officials and dignitaries as we celebrate a milestone in medicine! Look out for additional updates on our Facebook page and via email.

When: Friday, November 8 | 6:30 - 8:30 PM

Where: Drexel University College of Medicine 50 Innovation Way, Wyomissing, PA 19610

To RSVP, please contact TJ Huckleberry at tjhuckleberry@berkscms.org.

Thank you to our donors and supporters for making this event possible; we look forward to celebrating with you!

on the facts, we proved our hypothesis wrong and changed our opinion.

When I was on a rotation in my 3rd and 4th year of medical school, I was assigned to one attending. But healthcare is collaborative, and medical schools now recognize the importance of training students to work effectively with other healthcare professionals. Interprofessional education (IPE) brings together students from various healthcare disciplines—such as medicine, nursing, pharmacy, dietary, and physical therapy—to learn and practice communication, leadership and teamwork skills. Today we see teams walking through the hospital rather than a single attending with a single learner. This approach fosters a greater understanding and appreciation of each profession’s role and contribution in patient care and encourages collaborative problemsolving. This leads to a more complete patient-centered care.

Another major shift in medical education is the increased focus on student wellness and mental health. It has been known for a long time that the pressures of medical school are associated with stress, burnout, and mental health challenges. Medical schools are implementing wellness and stress management programs to support students throughout their training. These include mindfulness programs, peer support groups, and access to counseling. Schools are also revising their curricula to reduce the pressure on students, with a greater emphasis on work-life balance and self-care. By fostering a culture of wellness, medical schools will produce physicians who are not only competent in medical knowledge but also equipped to manage the emotional demands of the profession.

Medical students are being trained to understand the broader context of their patients’ lives, including the social determinants of health, which influence outcomes. This encourages physicians to involve patients in shared decision-making and to respect their individual preferences and values. The integration of humanities into medical education, such as literature, ethics, and the arts, also fosters greater empathy and understanding of a patient’s illness.

The advances in medical school education reflect the changing landscape of healthcare and the evolving needs of patients. Competency-based education, the integration of technology, interdisciplinary collaboration, and a focus on wellness are innovations shaping the future of medicine and improving patientcentered care. By embracing these changes, medical schools are preparing students to become well-rounded, compassionate, and competent physicians who can meet the complex challenges of modern medicine. These advances not only benefit medical students but will also improve patient outcomes and the quality of healthcare.

T.J. Huckleberry, MPA Executive Director

Astorm is brewing. The first to sense it are the deer and the rabbits who run to seek cover. The next are the birds who fly as far as the strengthening winds will take them.

And the buffalo stands still.

At the first crack of thunder, the mighty bear runs for its cave, and the wolfpack scatters in every direction.

And the buffalo stands still.

As the first drop of rain hits the ground, the squirrel scampers for the safety of the trees, snakes hide under rocks, and gophers burrow as deep as they can.

And the buffalo stands still.

Finally, when the wind is blowing its hardest, and the lightning crashes around it, and the rain is driving into its face, the buffalo snorts and slowly walks into the storm.

In the entire animal kingdom, only the buffalo knows that the fastest way of getting out of the storm… is walking right through it.

For years now, we have talked about burnout among our members. We tried to run from it, we tried to hide from it, but the storm kept coming. To further prove this point, and with her permission, I am reprinting a synopsis of The Physicians Foundation recently released 2024 Survey of America’s Current and Future Physicians, written by my colleague, Sara Hussey, MBA, CAE.

Sara is the Executive Director of the Allegheny County Medical Society, and this report was originally provided to her membership. As you will see the data provided continues to be sobering. It also illustrates that it is not just a health system issue, or a local issue, but a crisis that demands action in every capitol in the United States.

As we continue to honor our 200 years of organized medicine in Berks County, we need to look ahead and take stock in where this profession is heading. We need to walk through the storm and address mental health and the elements creating burnout.

And we need to do it now, because the next decade of medicine cannot survive inaction.

September 18, 2024

by Sara Hussey, MBA, CAE – ACMS Executive Director

The Physicians Foundation recently released its 2024 Survey of America’s Current and Future Physicians, highlighting key issues related to physician wellbeing and the impact of healthcare consolidation. Although there are some signs of improvement compared to past years, the overall state of wellbeing remains concerningly low. I encourage our members to review this survey in detail. However, I’m aware that your limited time (a direct contributor to burnout) may make this difficult. So, if you can’t read the full report, here’s a summary of some of the key findings: Burnout and Mental Health Crisis:

• Burnout remains critically high across all levels: 58% of physicians, 61% of residents, and 71% of medical students report frequent feelings of burnout. This is a sharp increase from pre-pandemic levels in 2018.

• Mental health concerns are widespread, with more than half of physicians knowing a colleague who has considered or

died by suicide. For medical students, that number is an alarming 45%, while 38% of residents also report knowing someone impacted.

• Stigma around seeking mental health support remains a significant barrier, with over 75% of physicians, residents, and medical students acknowledging that it exists within the profession.

• Consolidation in healthcare is perceived as negatively affecting job satisfaction and patient care. Seven out of ten physicians, residents, and medical students agree that mergers and acquisitions hinder access to high-quality, costefficient care.

• Negative impacts of consolidation include reduced physician autonomy, compromised patient care quality, and increased healthcare costs.

• Reducing administrative burdens is identified as one of the top solutions to improve physician wellbeing, with 80% of physicians and 85% of residents supporting this measure.

• Physicians also call for reforms to licensure questions, better access to mental health care, and safeguards to preserve autonomy in a consolidated healthcare landscape.

• Younger generations, especially medical students and residents, are advocating for mental health to become an integral part of healthcare discussions, fostering a more supportive environment for future physicians.

This report underscores the need for systemic changes to address the mental health crisis, reduce administrative burdens, and maintain physician autonomy as consolidation continues to reshape healthcare delivery. For the full report and more details on these issues, you can access the Physicians Foundation report.

by D. Michael Baxter, MD, FAAFP

Throughout this year we have celebrated many aspects of the proud history of our Berks County Medical Society (BCMS) and the practice of medicine by thousands of Berks County Physicians. In this issue of the Medical Record, we turn our attention to the history of Medical Education that has developed and sustained those physicians. In addition, we include reports from the work produced by our BCMS and Reading Hospital/Tower Health student summer interns. Their excellent reports remind us that our future remains promising as the next generation of clinicians and researchers join our profession.

In previous articles we have discussed how the earliest Berks physicians were trained, some through international or in the few early American medical institutions but most through an apprenticeship method. In this issue Dr. Dan Kimball reviews the breakthrough “Flexner Report” from the early 20th century which transformed medical education, establishing the format of sciencebased didactic and clinical experiences, including post graduate education, which remain the hallmark of physician training. Dr. Kimball provides an excellent overview of this report.

Within Berks County, medical education followed the Flexner recommendations with the development of formal pre-medical requirements for entry into higher quality medical schools linked to respected hospitals for their clinical training. Although Berks County physicians have studied at a wide number of medical schools both in the United States and abroad, there has been a particular connection to the “local” Philadelphia medical schools, represented on the cover of this issue with the iconic painting “The Gross Clinic” by Thomas Eakins picturing a scene at Thomas Jefferson College of Medicine (founded 1824). One of the very first American medical schools is the University of Pennsylvania founded in 1765. Others include Hahnemann School of Medicine founded in 1848 as the Homeopathic Medical College of Pennsylvania, the Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine (1899) and the Temple University School of Medicine (1901).

Particular note should be made of the Women’s Medical College of Philadelphia (1858) that was the first US medical school dedicated to the medical education of women. The Women’s Medical College later became the Medical College of Pennsylvania and in 1996 was combined with Hahnemann by the Allegheny Health Education

and Research Foundation of Pittsburgh into a new entity as Allegheny University of the Health Sciences. In 2002 Drexel University assumed control of this institution as the Drexel University College of Medicine which has a major campus now in West Reading.

With an initial grant of $50 million from the M.S. Hershey foundation in 1963, The Pennsylvania State University established the Penn State College of Medicine, broke ground on its medical center in Hershey in 1966 and accepted its first student class in 1967. Many students from this institution have trained at our local hospitals and in 2015 the St. Joseph Regional Health Network became a part of the Penn State Health System.

Graduate Medical Education has had an especially distinguished history in Berks County. Reading Hospital has long had an Internal Medicine Residency which also oversaw the one-year Rotating Internship completed by many of the former General Practitioners (GPs) of our area. In addition, the Obstetrics and Gynecology program at Reading Hospital has trained many if not most of these specialists for this area for generations. In 1972, Reading Hospital initiated its Family Medicine Residency Program, one of the first in Pennsylvania and the source of training for many of our local Family Physicians. Reading Hospital/ Tower Health now has a total of 35 residency programs and fellowships throughout its system. RH/TH has partnered with Drexel University to establish the West Reading Campus of the Drexel University College of Medicine, currently with a four-year total of 160 students, an exciting addition to our community.

St. Joseph’s Hospital began its Family Medicine Residency Program in 1978. When that institution acquired the former Community General Hospital in 1997 it absorbed the CGH Osteopathic Residency program into its Family Medicine Residency. In 2001, the St. Joseph’s Residency became an Osteopathic Family Medicine Residency

Adam J. Altman, MD

Angela Au Barbera, MD

Helga S. Barrett, OD

Jennifer H. Cho, OD, FAAO

Christine Gieringer, OD

David S. Goldberg, MD, FAAP

Marion J. Haligowski III, OD

Dawn Hornberger, OD, MS

Y. Katherine Hu, MD, MS

Lucinda A. Kauffman, OD, FAAO

Christina M. Lippe, MD

Barry C. Malloy, MD

Michael A. Malstrom, MD

Mehul H. Nagarsheth, MD

Abhishek K. Nemani, MD

Amy M. Olex, OD

Tapan P. Patel, MD, PhD

Jonathan D. Primack, MD

Kevin J. Shah, MD

Michael Smith, MD

Anastasia Traband, MD

Monica Wang, OD

Denis Wenders, OD

Linda A. Whitaker, OD, MS

For over 50 years, Eye Consultants of Pennsylvania has been the leading eye care practice in the region. Our team of ophthalmologists and optometrists is always available for consults and referrals on eye issues – a big reason why patients and referring doctors trust us like they do. And with offices in Wyomissing, Pottsville, Pottstown, Lebanon and Blandon, we’re right here, close to home for your patients. That means better care for your patients. For consultations and referrals, call 610-378-1344.

in affiliation with the Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine.

These GME programs have had a rich and storied history. In addition to training scores of physicians who have remained and practiced in Berks County, they have also contributed to the public health and social welfare fabric of life in Berks County. Many of the graduates and faculty (too

many to name here) have made substantial contributions to the field of medicine as leaders in our state and across the nation. We indeed have a proud tradition of medical education in Berks County which serves the health needs of our local patients and contributes to the advancement of our profession now and for generations to come.

by Dan Kimball, MD, MACP

The 360 plus-page Flexner Report was commissioned under the auspices of the Carnegie Foundation, founded in 1905. Their initial mission was to provide pensions for college professors, a task that would eventually become TIAA (Teachers Insurance and Annuity Association). Under the leadership of its first president, Henry Pritchett, the foundation trustees originally envisioned this proposed medical school study, as the first of many studies about the quality of professional schools, in North American and Europe.

It is notable that the American Medical Association’s Council on Medical Education, which was established in 1904, had as its primary focus when founded, “…the need for a comprehensive study of our medical schools including their curricula, facilities, and faculty” and were enthusiastic supporters and enablers of this study. Since the founding of the AMA in 1846, it was committed to two propositions, first, that “…it is desirable that young men received as students of medicine should have acquired a suitable preliminary education …” and secondly, “…that a uniform elevated standard of requirements for the degree of MD should be adopted by all the medical schools in the United States.” It would be more than fifty years after the AMA adopted those aspirational goals before work on those goals would begin. Many would suggest it began following the release of the Flexner Report in 1910.

Abraham Flexner, who conducted the study and wrote the report for the foundation, was born in Louisville, KY in 1866 and was the sixth of nine children born to Ester and Moritz Flexner. He was the first in his family to attend college. He attended Johns Hopkins University where he earned a BA in classics after two years

of study. He also pursued graduate studies in Psychology at Harvard University and the University of Berlin, but never completed work on an advanced degree.

In 1890, after teaching for four years at Louisville High School, he founded and directed an experimental college-preparatory school. Two years earlier, he had published a critical assessment of the state of the American secondary educational system, titled “The American College: A Criticism.” That paper would catch the attention of the Carnegie Foundation, which led them to invite Flexner to engage in his study.

Flexner opposed the then-standard model of education that focused on mental discipline and a rigid structure. His school did not give out traditional grades, it used no standard curriculum, refused to impose examinations on students, and kept no academic records of students. Instead, he promoted small learning groups, individual development, and a more hands-on approach to education. Flexner was not a physician and had never been inside a medical school before undertaking this study.

He joined the Foundation staff in 1908 and wrote this report in 1910, which is officially titled “Medical Education in the United States and Canada,” which is traditionally referred to as “the Flexner Report.” Although he is best remembered for this report, his greatest educational gift may have been his founding and leadership of the Institute for Advanced Study, a private, independent academic institution located in Princeton, New Jersey which quite notably included Albert Einstein as a resident scholar.

The Flexner Report contains two large major sections. Part I contains multiple chapters that include a review of the history of medical education in the United States, and an assessment of the current medical education process in the late 1800s. Four chapters outline what the four years of medical school should look like, including a chapter on the finances of running a medical school, a short section on “medical sects” to include homeopathy, osteopathy, and eclectic medicine, a short chapter on suggestions about the role of state medical boards in assuring the training of physicians, a short chapter about “the Postgraduate School,” which may be labeled the first internship, and two short chapters on the medical education of women and the medical education of the Negro, which in hindsight have been labeled as sexist and racially biased.

Part II of the report is a detailed listing of the 155 medical schools visited in the United States and Canada. Sixty-nine of these schools were proprietary. There is an appendix which includes a table showing the number of faculty, enrollment numbers, tuition income and the budget of the schools.

In a previous Medical Record article, discussing the career of the 18th Century Berks County physician and Senior Physician to General George Washington at Valley Forge Dr. Bodo Otto, I noted that apprenticeship was the primary method of medical education in our country from the colonial period through the early 19th century. During that time aspiring physicians would typically learn the trade by working directly under the supervision of an established doctor, gaining hands-on experience and practical knowledge. You might call this the “see one, do one” method of learning. This apprenticeship might last anywhere between 4 to 7 years and included assisting with surgeries, maintaining medical records, ordering supplies and other duties as assigned. The apprentice could begin his own practice when they were approved to do so by their supervising physician teacher. There was no board exam or licensure process.

The earliest medical schools in the United States included the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine (now the Perelman School of Medicine), founded in 1765; the King’s College Medical School (now Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons), founded in 1767; the Harvard Medical School, founded in 1782; and the Dartmouth Medical School (now the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth), founded in 1797. During the American Revolution, King’s College was temporarily closed, when the British occupied New York, and later reopened as Columbia College, which would eventually become Columbia University.

Proprietary medical schools in the United States began to emerge in the early 19th century. These schools were for-profit institutions that were often established by individual physicians or small groups of physicians. These schools would play a significant role in medical education during the 19th century, offering more formalized training compared to that of the apprenticeship model. The first

proprietary medical school in the US was the College of Physicians and Surgeons, founded in 1807, and would ultimately become part of Columbia University. By 1900 there were approximately 160 proprietary medical schools operating in the United States. These schools varied widely in their ability to screen applicants for admission, to have a standardized curriculum, to provide clinical experience, and to have appropriate equipment for teaching including laboratory facilities and libraries. Funding to pay the faculty and run the school was totally supported by tuition fees and donations. For the most part these schools were operated to make a profit for the founding faculty members.

Flexner felt strongly that two years of college with emphasis on study of the sciences should be required to enter a medical school but at the time of his report only 16 of the 155 schools had such a requirement, with six additional schools requiring one year of college. Fifty other schools required a high-school education or its equivalent, and about 80 other schools had little to no entrance requirements, other than the ability of students to pay the tuition fees.

Flexner notes in his report an exceedingly high failure rate, exceeding 50% in many of the medical schools surveyed, which he attributed to the lack of preparation by many of the accepted students. He captures some of the views of current professors at these schools with quotes from some of them, such as, “…the facilities are better than the students; …the boys are imbued with the idea of being doctors; they want to cut and prescribe; all else is theoretical; …it is difficult to get a student to want to repeat an experiment in physiology; …they have neither curiosity nor capacity; the machinery doesn’t stop the unfit; …men get in, not because the country needs doctors, but because the school needs the money.”

Flexner highlights a professor’s response to his question, “What is your honest opinion of your own enrollment process?” and the professor says, “Well, the most I would claim, is that nobody who is absolutely worthless, gets in.”

There were approximately 163 allopathic medical schools in the United States and Canada at the time of this report and Flexner visited 155 of them. He notes in his report that during the 100-year time before his report, there were over 450 different medical schools established, most of which had come and gone by the time of this study. For instance, the city of Chicago had 14 medical schools, the state of Missouri 47 schools and the state of Indiana 27 schools.

There were 8 Osteopathic medical schools in the United States in 1910 but to the best I can understand, Flexner did not visit many of them. He did include the then-newly established Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine as one of the 7 Pennsylvania schools visited. There were no osteopathic medical schools in Canada in 1910. In addition to osteopathy, there were 10 eclectic medical schools that focused on herbal remedies and 22 homeopathic medical schools at the time of the report.

continued on next page >

Outpatient counseling for drug and alcohol addiction, mental health wellness and youth behavioral issues

• Has been serving the Berks County community for more than 45 years.

• Provides high quality, comprehensive and coordinated care utilizing evidence-based practices with same day access to services.

• Has a Child and Family Center designed specifically for families and children experiencing behavioral issues.

• Is a Certified Community Behavioral Health Clinic and an Integrated Community Wellness Center (IWIC).

continued from page 11

Today there are 156 allopathic medical schools, and 40 osteopathic medical schools in the United States. There are 5 homeopathic organizations, not medical schools, with 4 in the United States and 1 in Canada, that offer training and certification in homeopathy. To the best of my knowledge, only the State of Arizona licenses homeopathic practitioners.

The following are the (paraphrased) six major findings of the Report:

1. For 25 years there has been an enormous over-production of uneducated and ill-trained practitioners (that is a quite damning statement to start the report).

2. Over-production of ill-trained men is due in large part to the existence of a very large number of commercial (proprietary) schools.

3. Until recently the conduct of a medical school was a profitable business, because the methods of instruction were mainly through didactic lectures.

4. The existence of many of these unnecessary and inadequate schools has been defended by the argument that a poor medical school is justified in the interest of the poor boy.

5. A hospital under complete educational control of the medical school is as necessary as a laboratory of chemistry or pathology.

6. Throughout the eastern and central states, the movement under which the medical school articulates with the second year of college has already gained such impetus that it can be regarded as practically accepted.

In summation, “Our hope is that this report will make plain once and for all, that the day of the commercial medical school has passed.”

There were 7 major recommendations of the Report:

1. There should be greater Standardization of Medical Education. The Report recommended that medical schools should adhere to high standards of admission and education, requiring at least a high school diploma and two years of college studies including premedical courses in biology, chemistry, and physics.

2. There should be Integration of Medical Schools with Universities. The Report advocated for medical schools to be part of a larger university system to ensure oversight, resources, and academic integration.

3. There should be greater emphasis on Scientific Method and Research in the teaching. The Report emphasized the importance of scientific research and the scientific method

in medical education, which includes a strong foundation in laboratory sciences.

4. There should be more Clinical Experience. The Report emphasized that medical education should include practical clinical experience in hospitals and dispensaries that would be affiliated with medical schools, allowing students to apply their knowledge in real-world settings.

5. Specifically, there should be a Reduction in the number of medical schools. The Report called for the closure of the proprietary and substandard medical schools that did not meet the proposed standards.

6. About Licensing and accreditation. The report urged stricter licensing of graduates and an accreditation process to assure that medical schools met the new standards.

7. And a recommendation to focus on the quality of medical graduates as opposed to the number of medical graduates.

The Flexner Report received a mixed reception in the medical community. Those schools already affiliated with colleges and universities were largely positive, while the proprietary schools were clearly threatened. The demands of this Report would put a strain on already inadequate funding streams for medical education. It was clear that tuition fees alone would be inadequate to support the future medical school.

Some have held that the Report reflected racist and sexist views that were inappropriate, while others would say that the report reflected the segregated and gender-biased norms of the time in 1910. It did result in the closure of five of seven historically Black medical schools, many in rural areas, with only the Howard University and Meharry Medical College being left to train African/ American physicians. Today, there are four historically Black medical schools in the US.

While Elizabeth Blackwell was the first female graduate from one of our medical schools (the Geneva Medical College, in Geneva, NY) in 1849, the number of female medical students in 1910 at the time of the Flexner report was very low. Dr. Blackwell had applied to many schools and was refused admission.

Today, just under 55% of our entering medical students are female. Enrolling qualified historically underrepresented students into our medical schools continues to be a challenge. Data reflects that in recent classes of students entering our medical schools, 25% are Asian/Pacific, 11% are Latino, 8.5% are African/American, and 0.2% are native American/Alaskan native.

Our long-term perspective and counseled insight provide the confidence investors need in today’s challenging environment. As a registered investment advisor, our fiduciary responsibility is only to you and the best interests of your investments.

In summation, clearly the Flexner Report has played a defining role in the establishment of medical education as we know it today. It has had a lasting impact leading to more qualified candidates for training, the establishment of standardized curricula, improved training of students, and a focus on scientific research, and led to the earliest forms of post-graduate medical education, giving rise to the many residency and fellowship programs which are essential to professional development and quality patient care. Integrity, Service, Performance. 610-376-7418 • connorsinvestor.com

The summer gathering of the 1824 Journal Club was held on August 15th at the B2 Bistro and attended by an inquisitive and congenial group of our local physicians. Continuing our historical travels through the past 200 years of medical challenges and transformational progress, we explored the years 1900-1960. Topics included:

The Flexner Report: A Defining Prescription for Science and Accountability in Medical Education (1910). Daniel Kimball, MD.

Alexander Fleming: The Discovery of Penicillin and the Dawn of the Age of Antibiotics (1928). Debra Powell, MD.

The Origins of the Framingham Heart Study: Advancements in the Diagnosis and Treatment of Cardiovascular Disease (1948). Nicola Bitetto, MD.

The Development of Chlorpromazine (Thorazine), the first “Antipsychotic” and the Philadelphia Connection (1951). Wei Du, MD.

Deciphering the Code of Life: Watson, Crick and Others

Describe the Double Helix Structure of DNA (1953). Ankit Shah, MD.

Jonas Salk, MD, and the Development and Rapid Implementation of the Polio Vaccine (1954-55). Michael Baxter, MD.

It was a fascinating and delightful discussion and most enjoyable evening. Our next 1824 Journal Club is scheduled for Thursday, November 21st from 6:00 p.m. to 8:00 p.m. at the Peanut Bar, 332 Penn Street, Reading. We will explore medical milestones from 1961-2000 including “The Tragedies and Triumphs of the AIDS Epidemic” and “Advances in Gastroenterology” including the “shocking” discovery that peptic ulcers are caused by infectious bacteria!

For the second consecutive year, Berks Community Health Center has been recognized by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) as a Gold Health Center Quality Leader. This recognition goes to community health centers in the top 10% for best overall clinical quality performance.

With over 1,400 Federally Qualified Health Centers nationwide, achieving Gold is a tremendous achievement. Achieving it in consecutive years demonstrates that BCHC, founded in 2012, is doing an exceptional job of meeting the healthcare needs of the community.

BCHC earned additional badges in recognition of specific quality measures met during the 2023 reporting period:

The Advancing Health Information Technology (HIT) for Quality Badge

Recognizes FQHCs that meet all criteria to optimize HIT services that advance telehealth, patient engagement, interoperability, and the collection of social determinants of health to increase the access to care and advance the quality of care.

Recognizes FQHCs that earn a Health Center Quality badge and increase by at least 5% in back-to-back reporting years either total patients served or patients receiving mental health, substance use disorder, vision, dental, or enabling services.

Recognizes health centers that collect data on patient social risk factors and increase the percentage of patients who received enabling services between the last two UDS reporting years.

The Patient Centered Medical Home (PCMH) Badge

Recognizes all three BCHC locations as meeting standards to be designated a PCMH. The patient-centered medical home (PCMH) model is an approach to delivering high-quality, costeffective primary care. Using a patient-centered, culturally appropriate, and team-based approach, the PCMH model coordinates patient care across the health system.

by Hannah Thompson Herring, DO

Being a mother in medicine, especially as an OB/ GYN resident, is a balancing act that is both incredibly challenging and deeply rewarding. The long hours in the hospital, sleepless nights on call, and the emotional weight of caring for patients make it hard enough. But add the demands of motherhood to the mix, and it feels, at times, like I’m being stretched in every direction possible.

Time away from my family is one of the hardest parts of this journey. Missing milestones, bedtime stories, and simply being present can lead to intense feelings of guilt. “Mom guilt” is real, and it doesn’t take much to start questioning if I’m doing enough for my child or if I’m missing out on moments I can never get back. But as difficult as these feelings are, coming home at the end of a long shift makes every hug, smile, and “I missed you” all the sweeter. Motherhood gives my work more meaning—it reminds me why I became a doctor in the first place.

In many ways, being a mother has made me a better physician. As an OB/GYN, I’m often walking with women through one of the most significant moments of their lives—becoming a mother. Having gone through it myself allows me to connect with my patients in ways I

couldn’t have before. I understand the fear, the joy, and the uncertainty that come with pregnancy, childbirth, and beyond. This shared experience fosters a sense of empathy that makes me better equipped to care for them.

Despite the challenges, I’ve come to realize that you don’t have to choose between being a great doctor and a great mother. It’s possible to do both—and to do them well. Society often makes women feel as though we must pick one path, but I’ve found that each role enhances the other. Motherhood fuels my passion for medicine, and my work reminds me of the strength and resilience I bring to both roles. Yes, it’s hard. But it’s also possible— and it’s worth it.

(This Resident Rounds is the final one for our current resident authors, Ashni Nadgauda, MD, and Hannah Thompson Herring, DO, both PGY IV OB/GYN residents at Reading Hospital/Tower Health. They were the original authors for this column and their contributions have added this valuable perspective to the Medical Record. The editorial staff deeply appreciates their contribution and wishes them much success and happiness as they graduate from residency in 2025).

MMy

From Florida to Philadelphia— My Journey to Medical School

by Amogh Nagol

y name is Amogh Nagol, and I am a second-year medical student at Drexel University College of Medicine’s West Reading campus. Born and raised in sunny Florida, I completed my undergraduate studies at the University of Central Florida (UCF), where my passion for science and medicine took root.

From a young age, I was fascinated by the human body and how healthcare can transform lives. This curiosity, coupled with the desire to make a difference, led me to pursue a career in medicine. After years of hard work, preparation, and persistence, I was thrilled to be accepted into Drexel’s medical program.

My first year of medical school was an eye-opening experience. It was a year filled with intensive studying, late nights, and a constant balancing act between academic responsibilities and personal well-being. However, beyond the challenges, it was also a year of growth—both academically and personally. I learned that medicine is not just about mastering scientific knowledge but also about resilience, collaboration, and empathy. Whether it was dissecting cadavers in anatomy lab or tackling difficult cases in problembased learning sessions, every experience brought me closer to understanding what it means to be a physician.

Being part of a small class in West Reading has fostered an environment of camaraderie and support that I’m incredibly grateful for. The friendships and connections I have made with my classmates have become a vital part of my journey. As I move into my second year, I am excited to continue building on this foundation and look forward to the clinical experiences that lie ahead.

by Peter Aziz

t was my interaction with a neurorehabilitation patient as an EMT that ignited my decision to pursue medicine. As I cared for her during our ambulance ride to the emergency department, I began to realize that she, due to factors beyond her control, was experiencing one of the most vulnerable moments of her life. Her neurological condition left her unable to communicate, both verbally and non-verbally. Nevertheless, we improvised a method of communication using nods and smiles to ensure her ambulance ride was as smooth as possible. Upon arriving at the hospital to transfer her care, I witnessed how both passionate and professional the receiving physician was, making sure to get the full story and carefully execute the next steps of her treatment. In that moment, I realized that physicians have the unique ability to ease patients’ burdens in an unparalleled way, ultimately turning that profession into my life-long pursuit.

During my undergraduate years at Seton Hall University, I was fortunate enough to double major in Biology and Philosophy, which, for some, were two opposite extremes of the academic spectrum. But I enjoyed my time. Frankly, I liked the intellectual freedom that the humanities offered compared to the sciences. After all, one cannot argue against the fact that the mitochondrion is the powerhouse of the cell or that vaccines save lives, but one can undoubtedly form arguments about the boundaries of morality, the foundations of freedom, and whether our legal system is truly just, and, in many cases, justified. These latter grey areas sparked my interest in the discipline of ethics, particularly the intersection of ethics and healthcare, as well as a slight interest in writing (as you can probably tell by now).

Training as a medical student has been a privilege. As my future colleagues and I navigate our second year at Drexel University College of Medicine’s West Reading campus, I am reminded almost every day that this path is both rewarding and challenging. The camaraderie we have developed among each other makes adapting to these challenges much easier. Reflecting on my journey, it was once unimaginable that the kid who moved to the U.S. from Egypt at 15 and could barely formulate a sentence in English, would one day be white-coated and entrusted with the responsibility of playing even a small part in alleviating human suffering.

(Our original Student Vital Signs author, John LeMoine MS IV, has passed the torch to our new authors, Amogh Nagol and Peter Aziz MS II, students at the West Reading campus of Drexel University College of Medicine. We thank John for his great columns and wish him the very best as he completes medical school and begins his residency in 2025. We look forward to learning more from Amogh and Peter in the months ahead.)

by Lucy J. Cairns, MD (retired)

“If I were applying to medical school now, I would never get in!” Such has been the reaction of more than one BCMS member over the years while reviewing the resumes of pre-med students applying for the Pat Sharma President’s Scholarship program. In addition to earning phenomenal academic credentials, many applicants have taken on leadership roles in multiple student-run organizations, volunteered many hours at nonprofits, undertaken original research projects, worked or volunteered for healthcare facilities, and the list goes on. We marvel at how these students find the time to eat and sleep. Very likely, there are times when they do not.

What does our summer program offer such high-achieving students? They hardly need yet another entry on their impressive resumes, although I’m sure it does not hurt. What I have come to appreciate, over eleven summers of helping guide our scholars through the program, is that its primary value has little to do with what the students learn in the course of researching their topics or adding another line to their resumes. Rather, the greatest benefit comes from being invited into the world of practicing physicians by a group of mentors who allow these students to witness first-hand the unique rewards of our profession and who model the ways in which doctors sustain themselves and each other when challenges arise. For pre-med students who may feel that they are working towards a goal seen only dimly in the far distance, the time with our program can bring a vision of what their lives could be like into sharp focus and leave them reinvigorated and more committed than ever to their chosen path.

This year we were thrilled to be able to support four outstanding Pat Sharma Scholars, thanks to donations to our Educational Trust from BCMS members Dr. Pat Sharma and Dr. Ray Truex. A debt of gratitude is also owed to those BCMS members who served on

the selection committee and to the many physicians who made space in their over-booked schedules to act as preceptors to Luke Forman, Emma Blackman, J’Kaia Reynolds, and Vinh Lu. As you read their research papers, be sure to note the names of those who guided these students in their research and writing. Space does not allow a complete list of all those physicians—and other healthcare professionals—whose contributions were vital to the success of this year’s program, but know that your generosity is greatly appreciated.

On behalf of the BCMS, I wish to thank Tower Health Chief of Academic Affairs Dr. Wei Du for his continued support, which takes the form of folding our scholars into the Reading Hospital Student Summer Internship Program. This relationship greatly facilitates clinical shadowing opportunities at Reading Hospital –Tower Health sites, allows our students access to didactic sessions offered to the hospital’s student interns, and enables them to present their research at an end-of-program event. GME & UME Coordinator Ashley Morris once again did a superlative job overseeing the day-to-day operation of this cooperative relationship.

The announcement for the 2025 Pat Sharma President’s Scholarship program will appear in the winter edition of the Medical Record and will be distributed to all BCMS members via Compass Points blast emails in January and/or February. To be eligible, a student should have completed at least two years of college by the summer of 2025 and have a demonstrated interest in medicine or other healthcare profession. BCMS members moved to support this program are encouraged to contact our Executive Director, Mr. T.J. Huckleberry, to make a donation to the Educational Trust and/or express an interest in acting as a preceptor. Please help us continue building on our success.

by Emma Blackman

BCMS Pat Sharma President’s Scholarship Recipient

Preceptors: Ray Truex, MD, Medical Director of the Pennsylvania Physicians’ Health Program, William Santoro, MD, Chief, Division of Addiction Medicine, Reading Hospital-Tower Health

Jon Lepley, DO, Medical Director, Addiction Medicine, Lancaster General Health Physicians

Cannabis, commonly known as marijuana, is an herbaceous plant belonging to the Cannabaceae family that has been cultivated for centuries for its medicinal and psychoactive properties (17). Recently it has become a significant topic of discussion in both medical and recreational contexts. This paper explores the clinical manifestations and dynamics of cannabis, examines its effects on the human body and mind and discusses the perspectives of medical professionals on its use and its potential as a gateway drug.

With the increasing potency and prevalence of cannabis use, it is essential to understand its implications for health and society. Cannabis has been documented to relieve pain, nausea, epilepsy, and other disease processes, and has been found in Central and South Asia, Europe, and Africa (5,8,10,14,17,26,28). The cannabis plant has two generally recognized species, sativa and indica, along with its wellknown neuroactive component, Δ9tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ9-THC), and nonpsychoactive cannabidiol (CBD) (11). Cannabis has become increasingly relevant due to an upward trend in the mean Δ9tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ9-THC) content, increasing from 3.4% in 1993 to 8.8% in 2008 (20). There have been 10- and 30-fold increases in cannabis potency since the 1970s (10).

In 2021, 35.4% of young adults aged 18 to 25 (11.8 million people) reported using marijuana in that year. In the following year 20.6% of 12th graders reported that they vaped marijuana at that time and 2.1% reported that they did so daily (1). In that same year, 2022, a survey for the first time recorded more daily and near-daily users of cannabis than alcohol (6). Elevated levels of use are prevalent among youth and now half of U.S. adults (50.3%) report they have used marijuana (27). To understand how potency and increased usage of this drug are clinically relevant, it is important to understand the mechanisms as well as the clinical effects cannabis has on the human body.

The endocannabinoid system in the body plays a role in managing pain, appetite, memory, and the immune system (18). Δ9-

THC binding is mainly responsible for the plant’s behavioral and psychotropic effects (10,29). At the same time, cannabidiol acts as an antioxidant, reduces THC psychoactivity and drug-seeking behavior, and normalizes neural abnormalities (5, 11). Both Δ9-THC and CBD bind with cannabinoid receptors CB1 and CB2 in the body (2,8,17). CB1 receptors are found mainly on neurons in the brain, and spinal cord (8,18,22). They are also present in certain peripheral organs and tissues, including endocrine glands, heart, and parts of the reproductive, urinary, and gastrointestinal tracts (8,22). CB2 receptors occur principally in the peripheral nervous system and immune cells, including leukocytes, spleen, and tonsils (8,22).

Due to the global distribution of the receptors in the body, countless consequences of cannabis use have been observed, ranging from short- to long-term physical and mental effects. It was observed that directly after consuming cannabis subjects have altered senses, including for color and time, as well as experiencing mood changes and difficulty with thinking, problem-solving, and memory. In cases of higher dosage, people may experience hallucinations, delusions, paranoia, and even psychosis. (1,21). In acute THC intoxication settings, impairment in learning, memory, and cognitive

continued on next page >

performance have been noted (22,25). The less-understood long-term effects include alterations in important neural pathways and possible loss of IQ points (1). There are also physical effects, including breathing problems, tachycardia, problems with child development, and cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome (1, 7, 8).

These health consequences of cannabis can then further cause lower life satisfaction, poorer mental health, poorer physical health, relationship problems, less academic and career success, and accidents and injuries (1). The summation of these negative health consequences is paired with frequently asked questions regarding the potential for addiction. One of cannabis’s largest hurdles in practice is understanding its “addictive nature,” which results in withdrawal and dependency. Subjects experiencing withdrawal from chronic cannabis use complained of inner unrest, irritability, insomnia, presenting ‘hot flashes,’ sweating, rhinorrhea, loose stools, hiccups, and anorexia (13,22). Negative health effects as a result of cannabis use are significant to understand because educating potential and current users can reinforce informed use to avoid severe consequences like addiction.

Dr. Ray Truex, a retired Reading Hospital Neurosurgeon and current Medical Director of the Pennsylvania Physician’s Health Program, explained that there is a significant effect of mood-altering drugs on the dopaminergic reward pathways, impacting the brain’s frontal lobes and limbic system, which control emotion, judgement, memory, and behavior. With repeated use of habituating drugs, these altered neuronal pathways can undergo neuroplastic changes, resulting in addiction. Dr. Truex endorses abstinence from marijuana and other potentially addictive substances for any person in a safetysensitive healthcare field because of its effect on memory, judgement, behavior, and motor skills, and its potential for addiction with chronic use.

Having explored comprehensive information regarding the clinical and mechanistic results following the use of

cannabis, it is important to contextualize cannabis’s potential to act as a gateway drug and explore its clinical prevalence within a real-world setting. To further understand the clinical relevance of marijuana addiction, William Santoro, MD, Chief of Addiction Medicine at Reading Hospital, was asked about his clinical experience with addiction to and abuse of cannabis. Dr. Santoro emphasized how previously he had strongly supported medical marijuana legislation and participated in its legalization for medicinal use. He currently disagrees with its broad acceptance for use as a medicine, citing the ease of obtaining a medical cannabis card for diagnoses without peer-reviewed, randomly controlled studies documenting evidence of efficacy for each diagnosis, as well as the potential for non-medical use. His support for the legalization of recreational marijuana is based on the benefits of ensuring the quality of legally sold marijuana compared to the risks of contamination in products obtained illegally. Furthermore, when compared to tobacco, cannabis is not a gateway drug. He mentioned that in the general population less than 20% smoke cigarettes, while within addiction facilities close to 90% of the population have used tobacco before their drugs of choice. Although addiction to marijuana is less prevalent than nicotine addiction, any form of overuse and abuse of a drug creates a risk of neurologic changes that may result in addiction. Marijuana can cause structural, functional, and physiological changes in some people. With the rising use of marijuana, it is important to understand how cannabis can be addictive, which is not yet completely understood. Dr. Santoro points out that legalization of recreational marijuana within the United States would allow for regulation of the purity, potency, and quality of cannabis. Those that become addicted should have treatment available, in the same way that alcohol is legal and those who abuse alcohol have treatment available.

Dr. Jon Lepley, Medical Director of Addiction Medicine for Lancaster General Health Physicians, has opinions similar to those of Dr. Santoro about the legalization of marijuana and its uses in medicine. Legalizing marijuana would result in a safer supply for people who are set on using it. Promoting its use for unproven medical

treatment, however, is a harmful practice that promotes poor standards of medical care and risks diverting people from seeking out proven interventions for their health problems. He also views marijuana as less immediately harmful than alcohol or other drugs like opiates. In a study conducted in Germany by addiction specialists, alcohol was estimated to be among the most harmful of addictive substances, along with heroin, cocaine, and methamphetamine (4).

To continue, both Dr. Santoro and Dr. Lepley have mentioned how marijuana has the potential to be regulated through decriminalization and legalization, similar to tobacco products and alcohol. Dr. Lepley notes that changes in the law would enable pharmaceutical companies to perform studies to identify evidence-based therapeutic uses for cannabis-based drugs that would undergo the FDA approval process. For the time being, cannabis remains illegal under federal law, so users can be incarcerated or punished.

Regarding the issue of driving under the influence of marijuana, some states have established limits on the allowed level of nanograms of THC per ml in a blood sample. Despite these limits, no reference range that reliably identifies significant impairment from marijuana use has been established, as exists for alcohol. Though some states limit blood levels to 5 nanograms per ml to be considered cannabis intoxication, due to the metabolism and storing of cannabis within fat cells and the bloodstream, it is difficult to test for real-time and true intoxication (9,23). In states where marijuana has been legalized for recreational use, there are conflicting reports on whether marijuana increases or decreases traffic fatalities. Some reports found no discernible increase in fatalities and a lack of statistical significance compared to states without recreational use, while other reports showed substantial increases. Those increases, in Colorado, Oregon, Alaska, and California, were16%, 22%, 20%, and 14% respectively. An association between recreational cannabis use and higher motor vehicle deaths was identified (3,12,15,19).

In summation, the perspectives of medical professionals highlight the complexity of the issues associated with cannabis use and its regulation. While there are potential benefits, particularly in managing severe pain and certain other medical conditions, the risk of addiction and other negative health effects cannot be ignored. Cannabis has the potential to shape our minds and our lives drastically, creating various symptoms affecting multiple realms of our health. It is a substance whose use spans centuries and is now being scrutinized in law and medicine.

Reflecting on research and conversations with Dr. Truex, Dr. Santoro, and Dr. Lepley, it is clear that cannabis use has many ramifications socially, physically, and mentally. Marijuana addiction is a considerable concern for the generations experiencing higher levels of use of more potent strains. To combat the harmful effects, steps should be taken to regulate marijuana to protect the minds of our youth and all citizens of the US. Although marijuana may not be considered an official gateway drug, its use does expose those who are more vulnerable to the risk of mental illness and further addiction. Marijuana has benefits for some, and it is the user’s responsibility to educate themselves on the various facets of consuming marijuana. As research continues, it is crucial to educate the public on the latest findings to ensure informed and safe use of cannabis.

Emma Blackman is in her final year as a pre-med student at Gettysburg College, with a Health Sciences major and a minor in Spanish. As the daughter of an ER nurse, she developed an early interest in healthcare and has accumulated several hundred hours of shadowing experience, confirming in her a passion for medicine and specifically for being part of an emergency department team, engaging in what she describes as “controlled chaos which saves lives.”

Abuse, National Institute on Drug. 2019. “Cannabis (Marijuana) DrugFacts | National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA).” December 24, 2019. https://nida.nih.gov/ publications/drugfacts/cannabis-marijuana.

Albano, Vincent. 2019. “CBD and the Endocannabinoid System.” Physicians Lab. January 30, 2019. https:// physicianslab.com/cbd-and-the-endocannabinoid-system/.

Aydelotte, Jayson D., Lawrence H. Brown, Kevin M. Luftman, Alexandra L. Mardock, Pedro G. R. Teixeira, Ben Coopwood, and Carlos V. R. Brown. 2017. “Crash Fatality Rates After Recreational Marijuana Legalization in Washington and Colorado.” American Journal of Public Health 107 (8): 1329–31. https://doi.org/10.2105/ AJPH.2017.303848.

Bonnet, Udo, Michael Specka, Michael Soyka, Thomas Alberti, Stefan Bender, Torsten Grigoleit, Leopold Hermle, et al. 2020. “Drugs Including Prescription Analgesics to Users and Others–A Perspective of German Addiction Medicine Experts.” Frontiers in Psychiatry 11 (October). https://doi. org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.592199.

“Cannabidiol: Pharmacology and Potential Therapeutic Role in Epilepsy and Other Neuropsychiatric Disorders - Devinsky - 2014 - Epilepsia - Wiley Online Library.” n.d. Accessed June 21, 2024. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/ epi.12631.

Caulkins, Jonathan P. n.d. “Changes in Self-Reported Cannabis Use in the United States from 1979 to 2022.” Addiction n/a (n/a). Accessed May 23, 2024. https://doi. org/10.1111/add.16519.

CDC. 2024. “Cannabis Facts and Stats.” Cannabis and Public Health. April 30, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/ cannabis/data-research/facts-stats/index.html.

Chayasirisobhon, Sirichai. 2020. “Mechanisms of Action and Pharmacokinetics of Cannabis.” The Permanente Journal 25 (November):19.200. https://doi.org/10.7812/TPP/19.200.

“DUI TALK: MARIJUANA BLOOD & BREATH TESTS | Rehmeyer & Allatt.” 2017. October 23, 2017. https:// arjalaw.com/blog/2017/10/23/dui-talk-marijuana-bloodbreath-tests/.

ElSohly, Mahmoud A., and Waseem Gul. 2014. Sativa.” In Handbook of Cannabis, edited by Roger Pertwee, 0. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:o so/9780199662685.003.0001.

Grotenhermen, Franjo. 2003. “Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Cannabinoids.” Clinical Pharmacokinetics 42 (4): 327–60. https://doi. org/10.2165/00003088-200342040-00003.

Hansen, Benjamin, Keaton Miller, and Caroline Weber. 2020. “Early Evidence on Recreational Marijuana Legalization and Traffic Fatalities.” Economic Inquiry 58 (2): 547–68. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecin.12751.

“How Does Marijuana Affect the Brain? Psychological Researchers Examine Impact on Different Age Groups over Time.” n.d. Https://Www.Apa.Org. Accessed July 3, 2024. https://www.apa.org/monitor/2023/06/marijuana-effectsbrain.

Kuddus, Mohammed, Ibrahim A. M. Ginawi, and Awdah Al-Hazimi. 2013. “CANNABIS SATIVA: AN ANCIENT WILD EDIBLE PLANT OF INDIA.” Emirates Journal of Food and Agriculture, June, 736–45. https://doi. org/10.9755/ejfa.v25i10.16400.

Lane, Tyler J., and Wayne Hall. 2019. “Traffic Fatalities within US States That Have Legalized Recreational Cannabis Sales and Their Neighbours.” Addiction 114 (5): 847–56. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.14536.

Levine, Amir, YanYou Huang, Bettina Drisaldi, Edmund A. Griffin, Daniela D. Pollak, Shiqin Xu, Deqi Yin, Christine Schaffran, Denise B. Kandel, and Eric R. Kandel. 2011. “Molecular Mechanism for a Gateway Drug: Epigenetic Changes Initiated by Nicotine Prime Gene Expression by Cocaine.” Science Translational Medicine 3 (107): 107ra109. https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.3003062. Long, Tengwen, Mayke Wagner, Dieter Demske, Christian Leipe, and Pavel E. Tarasov. 2017. “Cannabis in Eurasia: Origin of Human Use and Bronze Age Trans-Continental Connections.” Vegetation History and Archaeobotany 26 (2): 245–58. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00334-016-0579-6. Mackie, Ken. 2006. “CANNABINOID RECEPTORS AS THERAPEUTIC TARGETS.” Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology 46 (Volume 46, 2006): 101–22. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev. pharmtox.46.120604.141254.

Marinello, Samantha, and Lisa M. Powell. 2023. “The Impact of Recreational Cannabis Markets on Motor Vehicle Accident, Suicide, and Opioid Overdose Fatalities.” Social Science & Medicine 320 (March):115680. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2023.115680.

Mehmedic, Zlatko, Suman Chandra, Desmond Slade, Heather Denham, Susan Foster, Amit S. Patel, Samir A. Ross, Ikhlas A. Khan, and Mahmoud A. ElSohly. 2010. “Potency Trends of Δ9-THC and Other Cannabinoids in Confiscated Cannabis Preparations from 1993 to 2008.” Journal of Forensic Sciences 55 (5): 1209–17. https://doi. org/10.1111/j.1556-4029.2010.01441.x.

Pearson, Nathan T., and James H. Berry. 2019. “Cannabis and Psychosis Through the Lens of DSM-5.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16 (21): 4149. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16214149.

Pertwee, Roger G. 1997. “Pharmacology of Cannabinoid CB1 and CB2 Receptors.” Pharmacology & Therapeutics 74 (2): 129–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/S01637258(97)82001-3.

Project, Marijuana Policy. n.d. “Marijuana and DUI Laws.” MPP. Accessed July 12, 2024. https://www.mpp.org/issues/ criminal-justice/marijuana-and-dui-laws/.

“Reading Hospital - Reading, PA | Healthgrades.” n.d. Accessed July 3, 2024. https://www.healthgrades.com/ hospital-directory/pennsylvania-pa/reading-hospitalhgst1e59e6a6390044#overview.

Rogers, Kristen. 2024. “Cannabis Poisonings among Older Adults Have Tripled, Study Finds.” CNN. May 20, 2024. https://www.cnn.com/2024/05/20/health/cannabis-ediblespoisoning-older-adults-wellness/index.html.

Russo, Ethan B. 2016. “Clinical Endocannabinoid Deficiency Reconsidered: Current Research Supports the Theory in Migraine, Fibromyalgia, Irritable Bowel, and Other Treatment-Resistant Syndromes.” Cannabis and Cannabinoid Research 1 (1): 154–65. https://doi. org/10.1089/can.2016.0009.

Schaeffer, Katherine. 2024. “9 Facts about Americans and Marijuana.” Pew Research Center (blog). April 10, 2024. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2024/04/10/factsabout-marijuana/.

“The Health Effects of Cannabis and Cannabinoids - NCBI Bookshelf.” n.d. Accessed June 7, 2024. https://www.ncbi. nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK423845/.

Zou, Shenglong, and Ujendra Kumar. 2018. “Cannabinoid Receptors and the Endocannabinoid System: Signaling and Function in the Central Nervous System.” International Journal of Molecular Sciences 19 (3): 833. https://doi. org/10.3390/ijms19030833.

by Luke Forman BCMS Pat Sharma President’s Scholarship Recipient

Preceptors: Karen Wang, MD, Pediatrician and Chief Medical Officer of Berks Community Health Center

Lucy J. Cairns, MD, Berks County Medical Society

Food insecurity is a complex issue that impacts individuals and communities in a variety of ways. For the purposes of this paper, food insecurity is defined as the occasional lack of access to adequate nutritious food for a healthy, active life. The primary factors driving food insecurity include unemployment, poverty, and sudden income changes, which can impede access to food (Tester, et al. 2020). However, issues like availability of nutritious foods and stress in other areas of life affect the ability to obtain a balanced diet. Food insecurity is often understood through four pillars: food availability, economic and physical access, utilization, and stability (Sumsion, et al. 2023). These pillars offer a comprehensive framework to view and understand food insecurity. Food insecurity is a risk factor to obesity. This paper will analyze the prevalence of food insecurity in Berks County, the factors that contribute to this insecurity, and how this translates to childhood obesity.

Around 80% of all obese adolescents continue to be obese into adulthood (Simmonds, et al. 2015).

A large barrier to living a food secure life is the ability to afford nutritious food. It is estimated that $40,000,000 is needed annually to address the nutritious food shortfall. Despite federal assistance, 39% of households with food insecurity in Berks County do not qualify for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) due to having a higher household income than the necessary threshold to receive assistance (Map The Meal Gap, 2024). For a family of four to receive SNAP benefits, they must make below $4,144 per month, which is 26 dollars an hour for one full time worker, with approximately $850 added per additional household member (USDA, 2024).

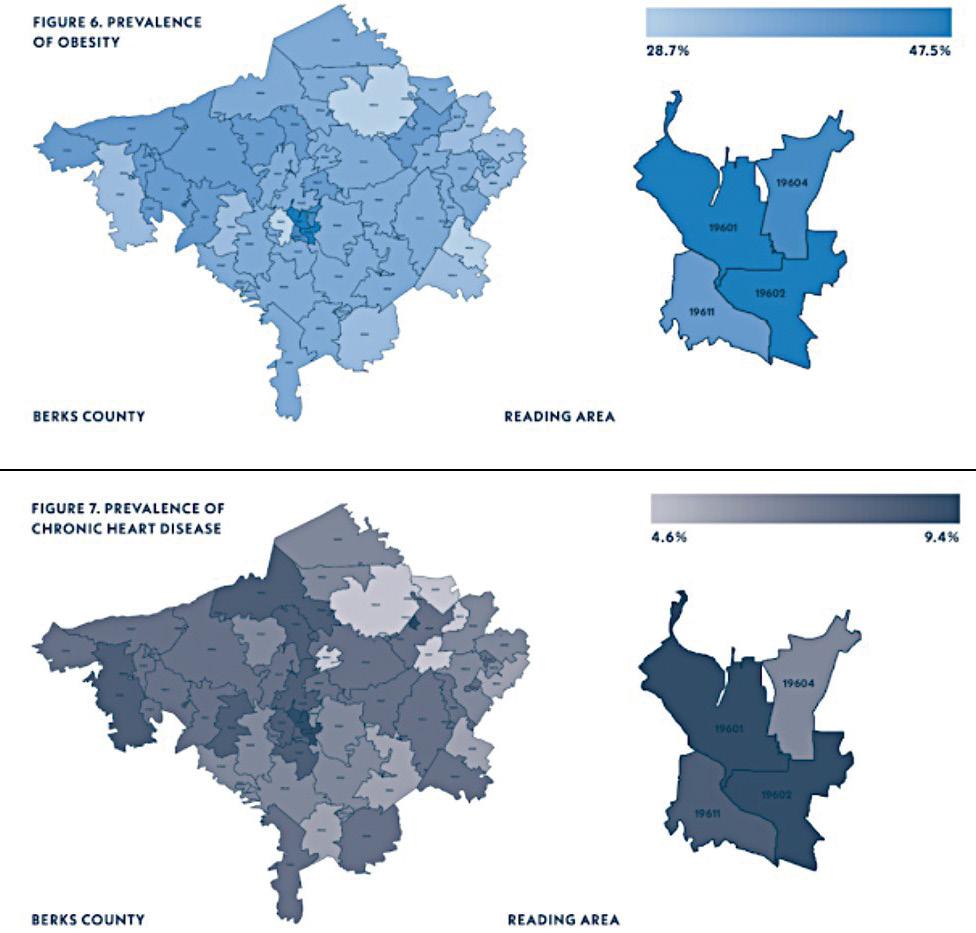

Approximately 12% of Berks County’s residents experience food insecurity, compared to the national average of 13.5%. This translates to 51,000 individuals being food insecure in Berks County. As it pertains to children, 18.5% of the US population under the age of 18 are food insecure, whereas in Berks County that number is 16%, equating to 15,000 children (Map The Meal Gap, 2024). There is a strong correlation between food insecurity and childhood obesity. Most published values indicate that food insecure children are 25% more likely to be obese. In Berks County, 18.1% of all children are obese (Blair, et al. 2020).

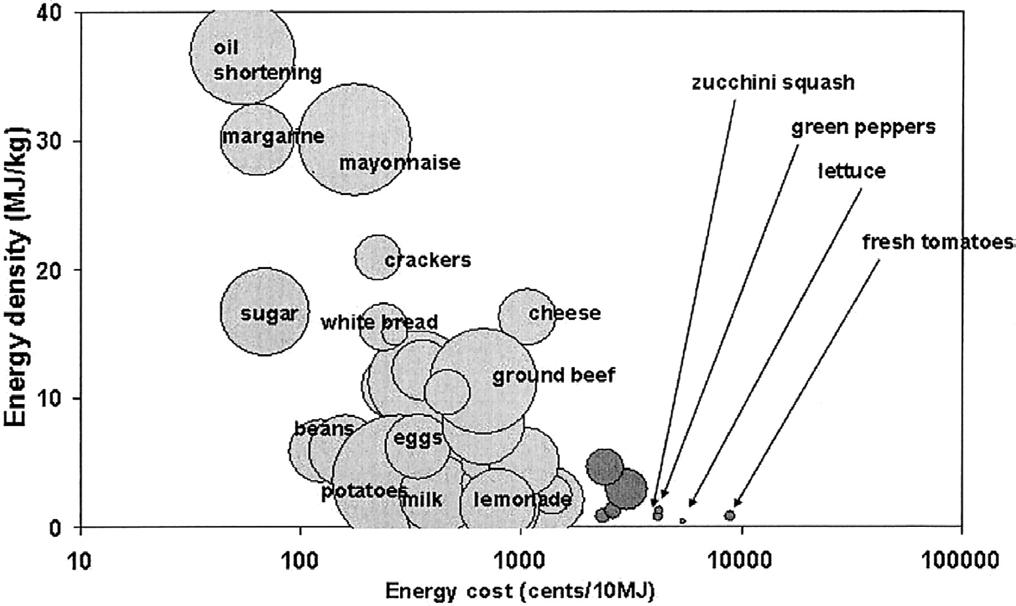

Food prices are the main driver of consumers’ purchase decisions. A report found that lowering the price of healthy foods was associated with an increase in the middle class purchasing these foods. However, even with the price drop, the nutritious food was still too expensive for individuals in the lowest economic group (Kern, et al. 2017). A study analyzing the price per calorie found that foods high in fats and sugars often provide the most calories per dollar (Drewnoski, et al. 2005). Inexpensive food options contain more calories, higher fat and sugar content, and are less nutrient dense.

Figure 1: A plot of foods with energy density on the y axis and cost on the x axis. The size of the circle indicates the amount of calories supplied to a family of four per week (Drewnoski, et al. 2005).

Even when fruits and vegetables are purchased, they are often in forms that contain additives. In 2000, more than 25% of total fruit servings sold in the U.S. were juices, which contain added sugars, and 48% of all vegetable servings purchased were made up of potatoes, including french fries and potato chips, canned tomatoes, and iceberg lettuce (Krebs-Smith and Kantor, 2000).

Biological factors are also contributing to food insecure individuals’ food choices. The chronic stress associated with living in poverty can lead to poorer quality diets among affected children. This stress activates the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, resulting in a hormonal cascade that eventually releases cortisol (Rutters, et al. 2012). Cortisol increases the craving for highly palatable foods, such as those high in fat and sugar, potentially leading to excessive caloric intake over prolonged periods of time (Chiu, et al. 2024).

The gut microbiome also contributes to the link between food insecurity and obesity. It is well known that the gut microbiome is altered based on the composition of our diets (Cella, et al. 2021). Obese individuals have a reduced diversity of gut microbiota compared to lean individuals. The gut microbiome of obese individuals shows a higher proportion of Firmicutes and a lower proportion of Bacteroidetes (Ley, et al. 2005). These changes in microbial composition result in an increased activation of genes related to energy harvest and storage, which may promote weight gain and fat accumulation (Clarke, et al. 2012). Additionally, the microbiome of obese individuals has a higher functional potential for processing dietary components into absorbable nutrients, contributing to greater caloric uptake into the body (Turnbaugh, 2006). In 2012, a study was performed on preschool aged children to compare overweight and normal weight individuals’ gut microbiome, and the overweight group contained a similar bacterial composition to that found in obese adults. The influence that the gut microbiome has on fat storage and caloric intake helps contribute

to the difficulty in losing weight that causes many overweight adolescents to remain obese through adulthood (Karlsson, 2012).

Access to nutritious foods is related to obesity. Without a nearby supermarket, people are forced to shop at convenience stores, which contain a disproportionate amount of highly processed foods. The presence of a supermarket was associated with a lower prevalence of obesity, whereas the closer a convenience store was, the greater the prevalence of obesity (Morland, et al. 2005). Figure 2 is a map of Berks County with such areas outlined. (see page 24)

Figure 2: This image shows food access throughout Berks County. Blue areas represent locations where the poverty rate is at least 20%, purple areas represent places where at least 100 homes have no access to a vehicle and live at least ½ mile away from a supermarket in an urban area, and at least 20 miles away from a supermarket in rural areas. The yellow areas represent an overlap of both (USDA, 2023).

For individuals, especially children, food insecurity can lead to numerous health and developmental issues. Children experiencing food insecurity have higher rates of cognitive, behavioral, and social problems and are more likely to suffer from stunted growth, poor oral health, anemia, asthma, and suicidal thoughts and tendencies (Sumsion, et al. 2023). The chronic stress of food insecurity contributes to disordered eating patterns and excessive caloric intake, exacerbating the risk of obesity and related health problems (Rutters, et al. 2012). Addressing food insecurity is thus crucial for improving overall health outcomes, enhancing quality of life, and reducing long-term health care costs associated with treating food insecurity-related health conditions.

Food insecurity is a risk factor for obesity. There are a multitude of personal and societal variables that contribute to this correlation, many beyond the scope of this paper, such as mental health (Carvajal-Aldaz, et al. 2022). The price of a nutritious diet forces food insecure individuals, particularly those ineligible for SNAP, to purchase inexpensive high-calorie meals with low nutritional value. The stress of living in food insecurity creates craving for highly palatable, sugary meals. In turn, this diet creates an unhealthy gut microbiome that exacerbates these cravings, which affects satiety hormones, like ghrelin and leptin, and insulin sensitivity (Evans, et al. 2012). Finally, the lack of access to supermarkets forces many individuals to shop for foods at convenience stores, which often lack fresh produce. All of these factors found in food insecure populations greatly contribute to their likelihood of becoming obese. Children are at greater risk

because of their lack of control over their diet, diversity of their gut microbiomes, and education (Sahoo, et al. 2015).

Figure 3: This image shows the overlap of obesity and heart disease in Berks County (Berks County Health Report, 2023).

Being obese throughout childhood and adolescence significantly increases the risk of premature morbidity and mortality (Simmonds, et al. 2015). The main cause of this increased risk is cardiovascular disease. In addition to increased risk for multiple diseases, quality of life, healthcare costs, and mental health are all impacted. There is evidence for a correlation between

obesity and mood, motivational, and eating disorders. These issues often lead to a cycle of overeating. The stigmatization of obesity can impair relationships with teachers, employers, family, and friends which can stunt education and career development, both of which are particularly essential for children (Berks County Health Report, 2023).

The high prevalence of food insecurity in Berks County reveals a critical need for comprehensive community-based interventions and support systems to ensure that all residents have uninterrupted access to sufficient affordable nutritious food.