BIRDING IN THE BUSH by Barry Hudson

Although geographically Bampton is in the Cotswolds and its stone built cottages and grand houses are reminiscent of the nearby landscape, the terrain is predominantly flat. The reason for the flatness of the land is that it sits mainly in a flood plain and drains into Old Father Thames that skirts the southern extremes of Bampton and adds to the diversity of its interesting bird life.

I am mostly concerned with the garden birds of Bampton but also with the local Berks Bucks and Oxon Wildlife reserve at Chimney Meadows and an important Tree Sparrow project near Tadpole Bridge. I will be mentioning some of the birdlife that inhabits the very pleasant countryside that surrounds us.

It is my intention to share with you my deep love of the natural world and how the comfort and wonder of the birdlife that surrounds us can be an inspiration for everyone. All it takes is the opening of one’s heart to the intricate, but at the same time simple, things that our gardens and beyond offer anyone with an enquiring mind and a realisation that we share this planet with all other living flora and fauna. Everything has its part to play in the amazing diversity that adds so much to make an ordinary human life full of the Wow Factor!

It is my intention to invite all those who wish to find out more about the wildlife that lives within their gardens to become involved by giving myself and perhaps one other access for regular surveys, perhaps three times annually. The purpose would be to record and thereafter advise how to improve the lot of the birds etc. through supplementary bird feeding and possibly a few appropriately

placed nest boxes. We might also suggest which plant species will benefit the insect life, and as a consequence the biodiversity, of your garden.

I do not intend to write this book in the usual bird book format, a format aimed at the well informed twitcher who is very concerned to add to a list of rare birds that they have painstakingly collected. NO! I am much more interested in the once-common birds, some of which have become endangered due to the actions of our own race. In particular the financially hard-pressed farming community that has unwittingly destroyed a great deal of our countryside biodiversity using a quick fix remedy of artificial fertilisers, toxic herbicides and insecticides. This process of degrading the very soil we all rely on will take it to a near non-returnable state if action isn’t soon taken.

I would appreciate very much any rarer bird sightings as this helps to build a more complete picture of the direction climate change etc. is taking through the northern movement of birds. It will probably surprise many of my readers that Ravens regularly fly over Bampton. Listen for their kronking calls, for although Ravens are wary birds they are also very verbal especially in flight. You don’t believe me? I have photographs that I have taken of Ravens in my next-door neighbour’s garden where I live in Bushey Row ( see page 19 ).

A few years ago I noticed what appeared at first sight to be a Blackbird in the field next to the hedging nursery and just before the Shillbrook Woodland, but something didn’t seem quite right and indeed it proved to be an on-passage Ring Ouzel. Thankfully I also had my camera with me and can show you a photograph later in this book ( see page 6 ).

Bampton has often been referred to as Bampton in the Bush. This was due to its remoteness with streams and rivers to cross and lack of good roadways. It is for this reason that I have entitled this book ‘Birding in the Bush’.

I very much hope you will enjoy sharing our Bampton world of bird life and that you also enjoy my style of writing that others have described as somewhat whimsical - and in truth I have been described in other less flattering ways!

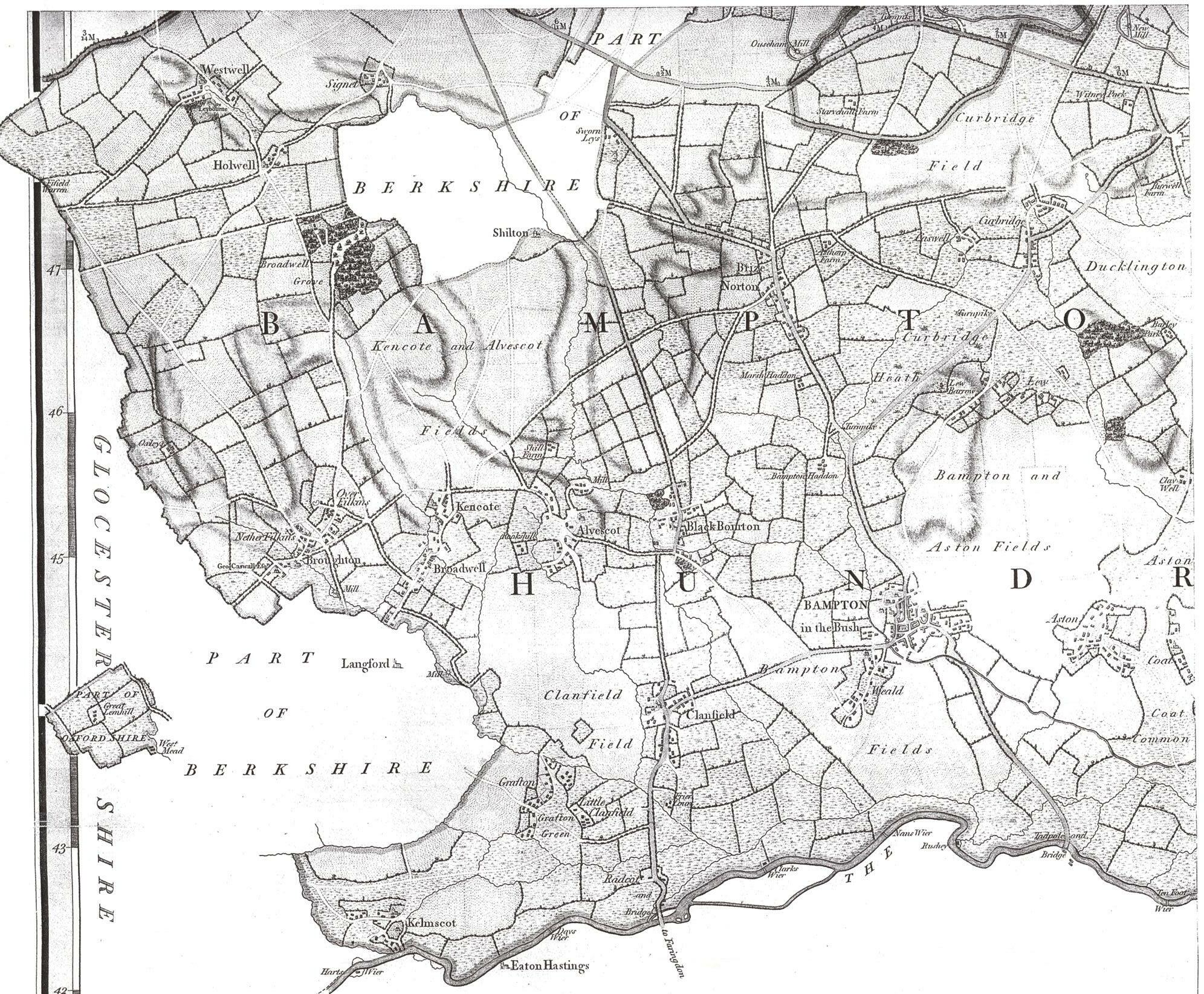

Map of Bampton dating from 1797

Teacher! Teacher! Teacher! Although sounding educational this is not about taking you back to school but the sheer delight of one of the harbingers of Spring, the Great Tit. With its broad black striped chest and belly set against the subtle yellows and blues this bird, with its rather strident oft-repeated call of ‘teacher’, is so welcome to our hanging offerings of peanuts etc.

Its cousin the Blue Tit, that acrobat of the Bird World, will be remembered by many with a few years under the bonnet (when we all had our milk delivered in foil topped glass bottles). This charming little imp would prize open the top and help itself to the rich cream off the top of our milk. This little angel earned its nickname of ‘Billy Biter’ through the spirited attempts of using its beak to punish fingers of egg robbers that sought out the tiny eggs being brooded.

The Coal Tit, being similar in size, is easily told apart from the former by the white blaze running down the centre of the bird’s nape. The most noticeable habit of the Coal Tit is its habit of not wanting to be noticed as it briefly settles on the peanut feeder, quickly picks a nut and is away again barely before one has time to take the sequence in. A real gem of the Tit family is the oh! so! charming Long-tailed Tit. This very cute family member is a little less colourful in plumage being predominantly black and white with some pink thrown into the mix.

While you may be lucky to have Long-tailed Tits visit your garden they can also be seen in the surrounding Bampton countryside as they search for titbits along the hedgerows in family groups. Never keeping still for long this all-action bird is perpetual motion with one bird overtaking the rest, but only briefly as the front-runner is quickly displaced by its brethren. The Long-Tailed Tit builds another incredible nest made of moss, lichen,

cobweb and feathers wherein up to some ten chicks are reared in a most crowded state. The nest has the elasticity to expand to accommodate the increasing size of the fledglings and, unusually among birds, the nest is domed with an entrance hole. If you ever have the pleasure of these characters visiting your garden look on it as a blessing for their never ending movement will fascinate you.

That bold bird defiantly singing through the wind and the rain on a prominent and lofty perch is likely to be the Mistle Thrush. His rather greyer appearance and rounded spots on his puffed out chest help us to tell him from his near relation the Song Thrush. Their songs will attract your attention most likely because they begin singing in late Winter when most other birds are still quiet.

As the name suggests Mistletoe is part of its diet if available. It is believed the plant benefits from the bird’s habit of placing the seed in a crevice to extract the soft juicier part, leaving the seed to later germinate. The Mistle Thrush can be quite a stroppy character and will aggressively fight off other bird life that tries to share the bounty of a particular shrub loaded with berries that it has commandeered. Beware of getting too close to its nest as it has been known to attack humans, for it is very protective in the vicinity of its breeding territory.

Mavis is a nickname for both of the Thrushes but originally applied to the Mistle Thrush. The Song Thrush’s song is unmistakeable as it repeats each phrase several times over. This is the garden friend that we watch as snails are dispatched with gusto. It greatly compliments our gardening attempts to keep some control over the pests that, when out of balance, make our efforts fruitless. The use of slug pellets have been instrumental in considerably reducing the numbers of this marvellous songster. While slugs are a constant challenge the use of strips of copper to protect our plants is an effective way to keep them at bay.

The Blackbird, another member of the Thrush family, is familiar to all and this yellow or orange-beaked beauty is one of our greatest songsters. It gives joy to all who listen to the song that is the backdrop of a British Spring and Summer. In my area of Bampton Blackbirds with partially white faces have been in evident for some years now and I wonder if it is local to my end of the village and if it is, that tells us they are site-loyal.

We benefit from the visiting Fieldfares and Redwings, often referred to as ‘The Winter Thrushes’. These birds you will see, often in flocks numbering hundreds, as they feast on the haws of our hedgerow Hawthorn bushes and other berry laden plants. They also relish the fallen fruit that they seek out in the Bampton gardens that grow fruit trees. When they have exhausted these means of nutrition they turn to pasture land of wintering farm stock, finding a further food source mainly in the invertebrates found in this habitat.

The ruddy, rosy, red-breasted Robin adds a splash of colour to our gardens and its name Robin is a derivative of Robert. This friend of all, especially gardeners, is a bit further removed from the thrushes than cousin but is nevertheless loosely related and is one of Britain’s best loved birds. In fact it has been voted in several publications by their readers as ‘Britain’s Favourite Bird’. The red is a somewhat orangey-red and brightens up a bird that would otherwise be just another ‘little brown job’. It is in fact in the family of chats - small birds that noticeably flick their tails.

There are two relations that we may encounter in our parish, the Stonechat and the Whinchat, but almost certainly not in our gardens. The Robin sings what sounds like a mournful, almost unhappy song and this is thought to be the ‘Nightingale that Sang in Berkeley Square’, as they will sing in the darker hours particularly if they are near street lighting. I expect almost everyone has a story to tell of strange nesting site places, from inside an outhouse to an old kettle. A good deal of ivy grows in my garden and I have a pair nest in it most years.

Along with the Finches I will be including their close relations the Buntings. All of these species have noticeably short but stout bills and I will start off with that gold standard beauty of our gardens, the Goldfinch. This stunning bird would not be out of place among the exotic birdlife found in the South American tropical rain forest. Pillar-box red facially and with an eye-catching flash of gold across its wing, this marvellous bird is thankfully doing well numerically. As a consequence this beauty will be found in every Bampton garden. A quick tipif you place teasels either stuck in the ground or tied to your feeders and sprinkle their favourite seed thistle on the teasel heads this gorgeous treasure will love and visit you for evermore.

The once common Greenfinch has been ravaged by the infectious parasite trichomonosis (canker), leaving us all the poorer for the loss of many of their number. Most gardeners will probably see them but only now and again and in reduced numbers. Their nest is out of kilter with most other family members, being a rather flat twiggy effort more in keeping with a Pigeon’s scrappy affair. The Bullfinch is another gem of this colourful family with jet black head and rosy-red breast. I think the host of the television programme Bullseye Jim Bowen summed it up best with his catchphrase “You can’t beat a bit of Bully”. This very attractive individual also builds a rather twiggy affair to raise its brood in.

The Linnet is not as obvious in our gardens as some other brightly-marked finches. They are most easily seen in our surrounding farmland in Winter flocks sometimes numbering in the hundreds. The male has, in common with the Bullfinch, a rosy-pink breast but to a lesser extent.

The Chaffinch is another common and muchloved finch with its “Spinck! Spinck!” call and it has obvious comfort in being close to human habitation. It’s at ease feeding on the seeds you supply either on the ground or from your hanging feeders – I believe that ground feeding is their chosen way of taking sustenance. If they breed in your garden you will be delivered of another treat when they build their incredible nest made from Mother Nature’s finest lichens and mosses. They nest mostly in bushes whereas the Goldfinch prefers to place its once again super nest in your fruit trees.

Some of the finches we can expect to see on our feeders are winter visitors including the Chaffinch-like Brambling, also the Redpoll is a possibility, whilst the Siskin is a likely visitor. Look out for it feeding on Alder and Birch.

Reed Buntings sport an attractive mainly black head and bib broken up with contrasting white, and they readily come to our feeders. The formerly common Corn Bunting is a rather struggling species and if seen at all it will most likely be on Bampton farmland. It gets its pet name of Barley Bird for its preference of feeding on this cereal and it has a song that has been likened to the jangling of a bunch of keys.

The bright star among the Buntings for me is the Yellowhammer. Its amazingly bright yellow livery is similar to the in-flower Oilseed Rape that is so colourful (but stinks and which most people find unpleasantly overpowering). To see a flock of Yellowhammers is a very colourful and pleasant experience. Some of us will get them in our gardens as winter visitors and the lucky ones will enjoy them as breeding birds.

We are so fortunate in Bampton to welcome into our parish during the summer months a bird that I can only describe as the Unbelievable Bird. Before science proved otherwise, had I tried to tell you about a bird that, apart from a few weeks when it nests, spends all of its time on the wing, you would have been entitled to accuse me of being a fantasist. But indeed it feeds, takes its moisture on the wing and – yes – sleeps and mates on the wing! This truly amazing bird is the Swift, often seen in the summer scraping the heavens so high as to be almost out of sight. You will know they are up there by the loud strident screams they emit as they soar and flutter, feeding on many insects including small spiders that have become airborne hanging onto the gossamer threads that the breeze and thermals have lofted high up into the clear blue sky.

The Swallow and the Cuckoo are the birds we most regard as the sign that Spring has arrived. Thoughtful folk leave a barn or garage window open to facilitate entry and the construction of its mud-based nest. They do indeed make the heart miss a beat on their arrival and fill us all with a little gloom as they line the telephone wires when they assemble before the approaching autumn, for the warmth of the African continent and an insect supply that will carry them through the winter months.

We are also fortunate in having House Martins nest in our midst – they too rely on a plentiful supply of insects. Under their nests it can get a bit messy but this really is a small price to pay for the delightful entertainment they unwittingly engage us with. Remember our forefathers strongly believed that any house harbouring the nest of a House Martin enjoyed divine protection and would never be struck by lightning.

We only need to concern ourselves with five Warblers, firstly the Blackcap (at least it’s black on the male). It’s a somewhat sexist title as the female wears a rather nice brown topper. Notwithstanding the naming imbalance, you will quite possibly find them on your winter feeders as they are one of many indicators of climate change.

Nowadays many of them are finding our winters less harsh than they used to be, and they have become a welcome addition to our bird tables. They may nest in some of our Bampton gardens but please do not look for their nests as, like all our delightful avian guests, they have a much better chance of breeding success if we just let them get on with it.

Bampton enjoys the company of three Wagtails, the most common being the Pied Wagtail. As its name proclaims it is a black and white bird and has in common with all its clan a daintiness almost beyond description. They nest under tiles in outhouses or on ledges. I remember before I retired from farming I had one nest on top of the engine of a tractor, and, after removing the nest and placing it on a ledge close by, these resourceful birds continued to lay eggs and consequently reared and fledged four chicks.

The Grey Wagtail is seen along the many Bampton waterways. I have seen a nesting pair at Rushy Lock where the backdrop of falling and loudly swirling water did not concern them as they went about their parental duties of collecting the countless insects that their insatiable open-gaped brood demanded.

The third Wagtail is the Yellow Wagtail, a bird not to be met with by most folk, but I have seen a nesting pair in a wheat field alongside the footpath running from Bampton to Black Bourton.

Two other Warblers, the Chiffchaff and the Willow Warbler are very similar in appearance, but if you are fortunate enough to be host to one of them it is more likely to be the Chiffchaff. It repeats its giveaway name over and over again, “Chiff-Chaff”. Pray do not think I find the call tedious –I do not as it renders its song in a gentle manner.

The Whitethroat and Lesser Whitethroat will possibly be found on your walks along our farmland hedgerows. Often heard and not seen as they can be of a skulking nature. My late parents always referred to them as Nettle Creepers.

I will now focus on six birds that do not have a close family relationship with other local birds. The Goldcrest is our smallest British bird and weighs in at about the weight of a ten pence piece. They are an attractive small bundle of feathers and are often seen in conifers and hedgerows making their high-pitched calls that are these days unheard by me, as my hearing is not what it used to be. They construct an amazing nest that is slung underneath a bough. Another childhood memory takes me back to a pair of Goldcrests that had built a nest that unusually underhung a Willow tree. This was my late wife’s favourite bird and I gave the marvellous illustration by Ian Lewington on the cover to my sweet Linda Mary (Linner) on her sixtieth birthday.

The Dunnock, often referred to as the Hedge Sparrow, is a furtive bird as it creeps about in our garden borders or under our bird feeders. Although apparently another “little brown job”, on closer inspection will be revealed the most subtle shades of grey/blue on the neck area. Sexually this promiscuous bird makes Casanova look almost platonic.

The Treecreeper can be seen as it makes it way, often spirally, up a tree searching for the insects that hide beneath the loose bark. This loose bark found on older trees is its choice of nest site, it utilises the space behind the bark to conceal a nest in which to bring forth the next generation.

From a favourite perch the Spotted Flycatcher will repeatedly make winged forays to collect and devour insects, including flies, that this site-loyal little brown job feeds both itself and its youngsters on.

A late May arrival from its wintering grounds in Africa, it has a relatively short breeding season due to its reliance on flying insects and, occasionaly, aphids and is unable to arrive earlier in case the insect season is not yet in full swing.

My late father ‘took’ South Farm in 1949 situated between Uffington and Wantage and in one of the open fronted implement sheds regularly nested some half a dozen pairs of Spotted Flycatchers.They were a great delight to us. Unfortunately we took in a stray

cat that we named Arum-Sacrum due to his somewhat wild nature. This cat destroyed our Spotted Flycatcher colony and we lost these delightful birds for evermore.

The Skylark, which inspires poet and musical composer alike, will not be found in your gardens but will most certainly be met with on walks across our surrounding Bampton farmland. It will often oblige with a rendition of its uplifting song as it seeks out the heavens on fluttering wings before suddenly dropping to earth.

The Nuthatch is an exciting and unusuallyshaped bird, looking more like a wedge than any other bird. With its blue top and rusty brown underside, all set off with a jet black eye stripe, this little stunner chooses a hole in a tree and usually adjusts the entrance by plastering it with mud until the optimum size is attained. This most welcome “friend” to my garden has another trick up its sleeve. It is the only British bird able to walk down as well as up a tree.

The Starling is familiar to all and very common, but like many of our other bird species is suffering a decline. Most of us have gone from thinking of them as greedy pests at our bird tables to being rather pleased when they turn up. The word ‘Starling’ is a reference to the many-spotted plumage that resembles stars.

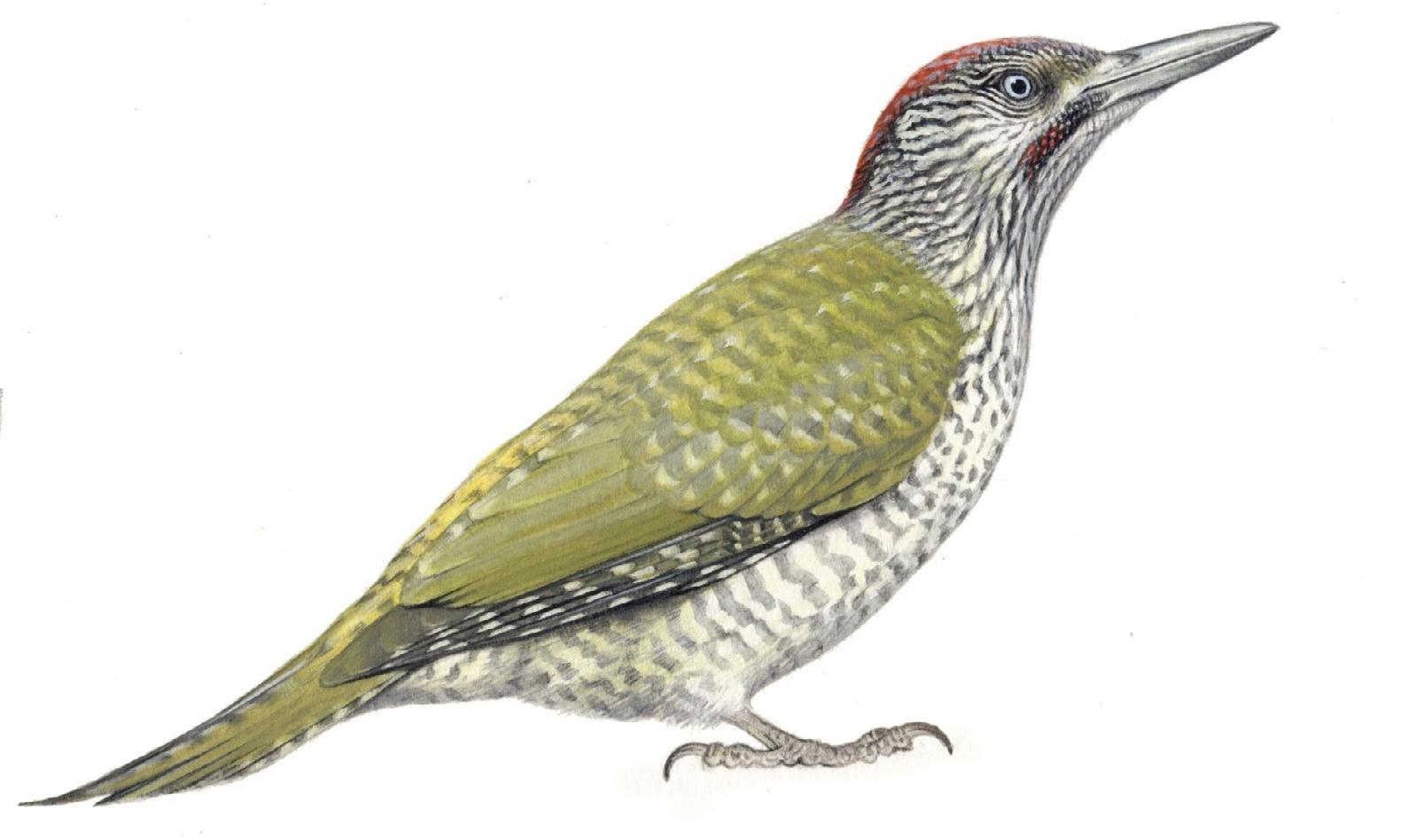

The striking green, red and black plumage of the Green Woodpecker will alert you to the presence of this eye-catching beauty. Ants are sought out on your lawn and consumed via a long tongue. The call has been likened to human laughter and is also responsible for the nickname of ‘Yaffle’. Another clue to identification is the dipping flight that gives the bird its mobility.

The other woodpecker you will surely see in your garden is the Great Spotted Woodpecker. Like the former it has experienced an upsurge numerically and in the Greater’s case this is as a direct result of the peanuts and sunflower seeds many of us now supply in our feeders. They feature an attractive livery of black, white and red. Beneath this loveliness is a cold heart that will seek out vulnerable nestlings of wooden nestbox breeders, gaining access by enlarging the nestbox openings to devour the fledglings therein. Protection can be given by the fitting of metal surrounds supplied by most pet shops. This will mostly suffice except in rare cases when it’s spear-like beak is employed through the side of the nest box.

“Oh No!”, I hear you say as the dozen or so Wood Pigeons greedily scoffing the food you have put out for all your garden birds to share are joined by more of their own kind. Let us remember Wood Pigeons get hungry too and if they were an uncommon bird we would make them very welcome. Before you dismiss them take a closer look at the remarkable colour of the feathering and the subtleness as one grey blends into another and also the hint of soft pink that adorns their breast. Note too the white quarter necklace and the white wing bars as they depart with a loud clap of their wings.

The Stock Dove is a common bird of our Bampton gardens, probably often overlooked because it needs closer examination to distinguish it from the ‘Woodie’. There are two main differences, the first being the necklace they wear, an adornment when caught in the rays of the sun is an iridescence of shining blues and greens.

It also sports a black wing bar. Whilst the former nests on an untidy patch of twigs in trees and hedges, the Stock Dove finds holes in trees and disused Owl boxes in barns and trees in which to bring forth its brood.

The Collared Dove is a relatively recent addition to our fair isle and before the 1950s it was virtually unknown to us. Yet with a huge expansion it is now found almost everywhere and Bampton is no exception, with every garden aware of this most dainty of its tribe.

Pigeons feed their young on a substance known as Pigeon Milk, a regurgitated food that they prepare and supply to their chicks (or more properly their Squabs as the young are known). Pigeons have one more interesting ability not found in any of our other British birds and that is the ability to drink by sucking liquids and using their bills somewhat like a straw rather than the norm which is to take a beak of water and throwing the head back in order to swallow.

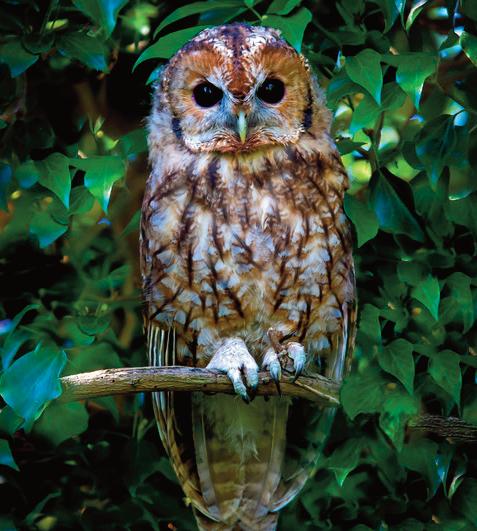

Who, Who, Who, Who, Who, Who? Well, it’s not me it’s them – them being the Tawny Owls. They are masters of concealment during the hours of daylight when they retire from hours of hunting in the night-time darkness. They search for rodents that are their main food source and thereafter take refuge either in holes in trees or remain stock-still in an upright position, blending in cryptically within the confines of trees, es pecially old bent over and gnarled willows. Our larger gardens will quite possibly be host to this bird and able to enjoy its song, commonly described as “Tuwhit-to-woo”, which is in fact two birds calling and answering each other, the female “Tuwhit” and the male answering “to-woo”.

The fierce looking Little Owl is correctly named as it is our smallest owl and breeds in tree holes or rabbit’s burrows. This relatively recent introduction to our shores has only been with us since the 1850s and although it has established itself as a breeding bird it is what I would describe as fairly local. It is probable that there are Little Owls in Bampton gardens – not that I know of any personally.

The much loved white ghost that sails through the evening gloom is of course the Barn Owl, hunting its prey using sound rather than sight. I know of two local farms that thoughtfully supply a helpful breeding environment and have expert bird teams monitoring their wellbeing. As with all our owls they rely on a good supply of rodents, particularly voles. Please! Please! Take every precaution when dealing with a rat or mice infestation as these poisons pass down the line and are responsible for the premature deaths of many of the owl clan.

The Red Kite has colonised much of the UK since being reintroduced and spreading from Buckinghamshire. The name Kite is most apt as this long-winged bird plays the wind and thermals with consummate ease, displaying great natural skill and calling in a voice sounding like a high piping mewing. Most farmers and gamekeepers blame the Red Kite for being responsible for killing our local hares, rabbits and small birds but although they will occasionally take small birds they prefer carrion and will also spend hours searching for worms. I watched a pair of Kites that had chanced upon a less than half grown rabbit and both birds made repeated attempts to fly off with their bounty. After grasping the rabbit in their talons neither bird could fly higher than a few yards before the weight was too much of a burden and it was dropped. For all their large size they lack strength and are physically unable to take anything but small prey.

The Common Buzzard takes me back to my childhood when I would look at pictures in my bird books and wish this large and impressive predator was a local bird. Many years later my prayers have been answered as they have re sponded to an easing of pressure as gamekeepers and farmers have come to realise that the Buzzard’s contribution to rabbit control is significant. The Buzzard has become common locally, and a whiter-coloured version is the result of a light-coloured male moving into the locality and having a greater influence than one might have expected on our Bampton population.

The Common Buzzard is another avid worm hunter and seeker-out of carrion but this strong flyer is capable of taking and killing rabbits. In conjunction with Mr Fox, it is the reason rabbit numbers have been kept agriculturally bearable. The Buzzard also uses the thermals to climb high into the sky, soaring in a circular motion apparently effortlessly, and is so skilled that it can be lost to view as it surveys our Bampton parish looking for its prey.

The Kestrel is a delightful bird as it sits on telephone wires waiting for the mainly small rodents it feeds on to make a move. However we see it at its most incredible when it hunts its prey by using the amazing tactic of hovering – this is one of the natural world’s wonders. One can spend a great deal of time being entertained by this bird’s remarkable ability of coordinating wind and wing movement to stay almost stationary and gain buoyancy in order to locate sustenance.

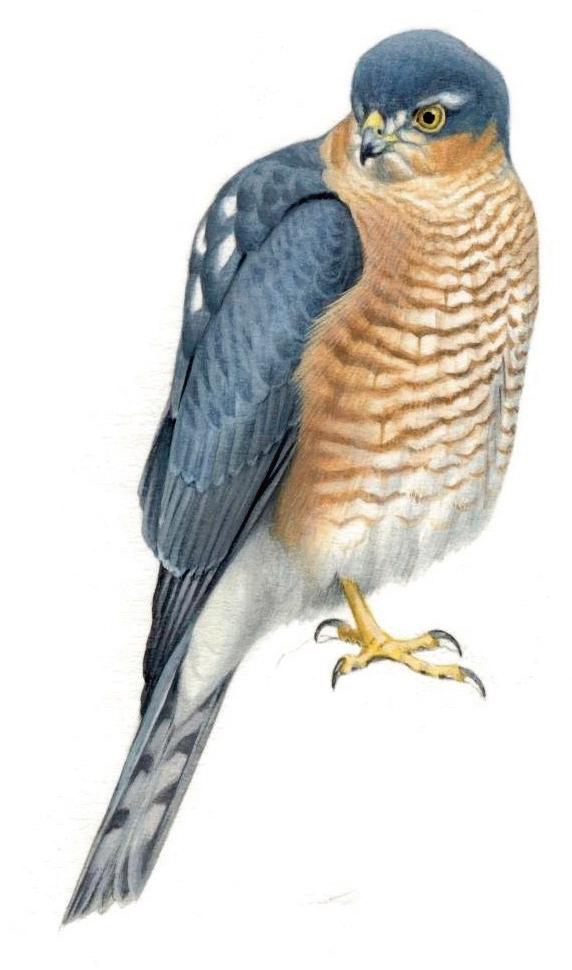

The Sparrowhawk is the villain of the piece as far as our gardens are concerned, for it often preys on our much loved garden song birds, and is mostly the reason that we notice a sudden drop in birds using our feeders. The Sparrowhawk will return again and again until it has either eaten a significant number of our garden birds or they have left for less dangerous gardens in the vicinity. The male is smaller than the female and she is capable of taking a Wood Pigeon – something they regularly do.

All these Birds of prey may nest in our gardens but they can be very secretive at the nest site and we are more likely to notice them on the open fields around Bampton.

Sparrowhawk

With its bright eyes, grey and black feathering and long association with humans, the Jackdaw is a daring and mostly well-loved visitor to both gardens and rooftops, where it exploits the chimneys of Bampton to bring forth its next generation. It fills some of the deeper chimneys and hollow trees with phenomenal amounts of twigs that must run into countless thousands and must also represent many hours of very hard work. Jackdaws are adept at overcoming difficulties at our feeders and often fathom out a way to take that which was not intended for them. They belong to the Crow family – a species of bird long admired for its high intelligence. They are the least wary of the Crow family, choosing to live close to humans. I remember a friend at school had a tame Jackdaw and this rather stroppy bird would turn up at any time of the school day and perch on a random shoulder. Depending on its mood it would either quietly sit thereon in apparent abandon or attack its host’s ears and face with some ferocity – to the delight of other classmates!

The Rook is black but sports a grey base to its beak, making identification an easier achievement than it would otherwise be. Nesting in the parish rookeries, this omnivorous feeder of harmful wireworms and other grubs blots its copy book somewhat with its fondness for grain. They are noisy birds especially at their nests and I have watched them congregate on the ground, holding what some believe to be an avian parliament, wherein some apparent leaders seem to be instructing the rest – but of course such things may only be in the eye of the beholder.

The Carrion Crow is generally seen as a more solitary or paired bird. Although they do sometimes flock, the usual rule is that if you see a single or a pair of this sized bird it is probably the Carrion Crow, whereas a flock are probably Rooks. Carrion Crow pairs nest alone, placing their large nest amidst the branches of trees that, because of the wariness and secrecy of the parents, often go unnoticed during the breeding season.

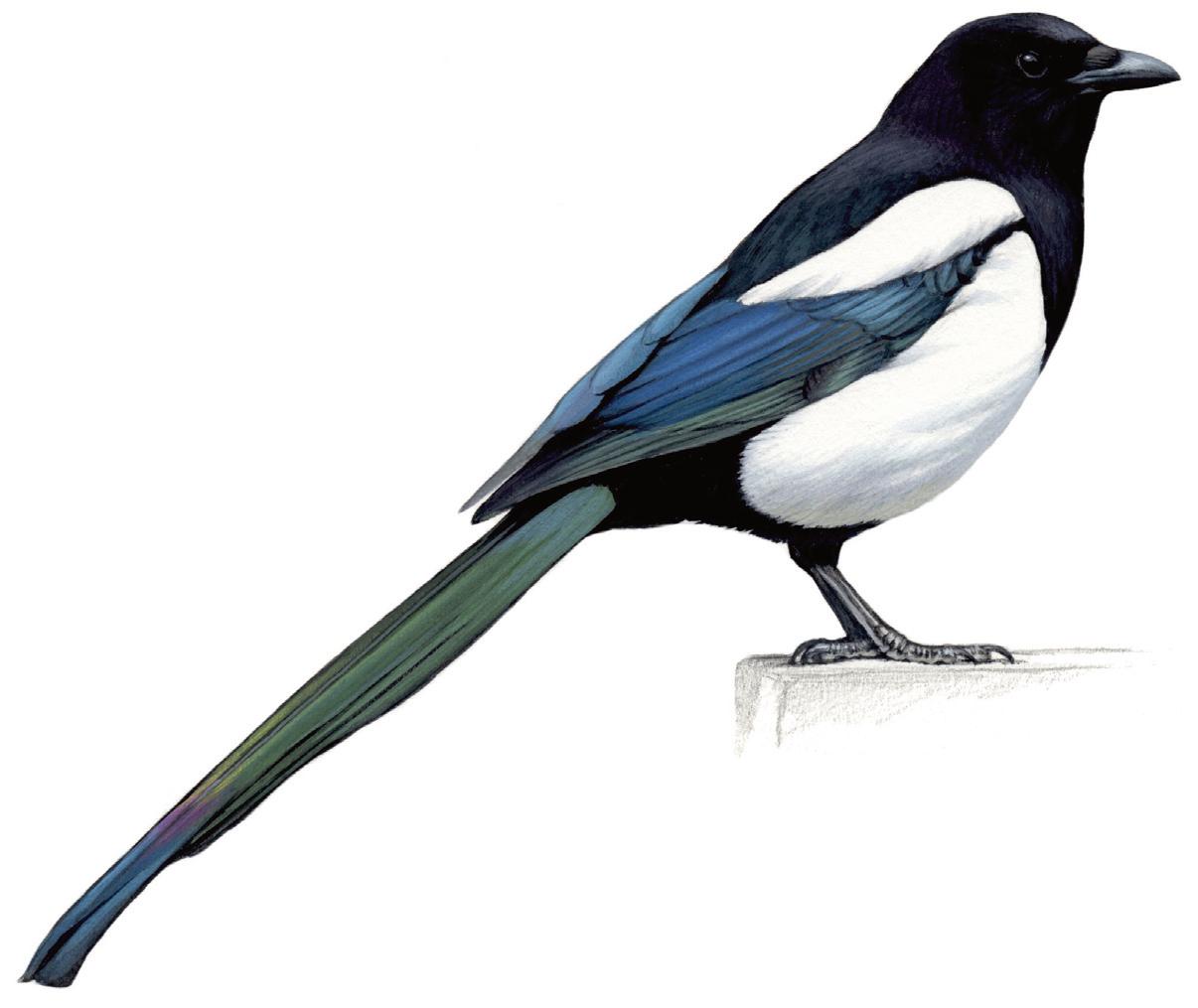

The Magpie, that strikingly-plumaged black and white long-tailed bird, is in fact multi-coloured and when caught in the rays of sunlight displays a myriad of greens and blues that set the tail aflame with colour. Magpies are domineering birds that bully and cajole our other garden birds and take the sweetest tit-bits on offer. To add to their list of crimes they are rather partial to the young of other birds, but nevertheless are a beautiful addition to our gardens and an addition that is relatively a modern phenomena. My earlier experiences of the Magpie was as a bird of the countryside that nested in blackthorn thickets and placed its roofed nest in thorn-protected positions, giving any schoolchild egg robber painful and bloody scratches for their endeavours.

The Jay, that raucously screeching white-rumped Crow, is the most beautifully coloured of this family of birds and is another Crow that has a destructive nature, taking many fledglings in the breeding season. However, the Jay has a saving grace for, as it collects countless acorns in the Autumn and buries them to protect itself from future hard times, many acorns are forgotten about. Thus the Jay is responsible for planting more oak trees than are planted by any other means.

A dream bird of my childhood, the Raven was another bird I never expected to be found regularly flying over my garden and across the centre of Bampton. Not only flying over but I have photographed a pair of Ravens in my nextdoor neighbour’s garden. Jet black and chunky in appearance, Ravens are now not uncommon in Oxfordshire. They mostly breed on some of our larger farming estates and are easily identified by their unmistakeable ‘cronking’, a sound which once heard will never be forgotten.

With the exception of the Raven all the Crows are possible breeders in our Bampton gardens.

This mixed bag of local birdlife is in no scientific order but some can be seen on the marvellous clear running streams that our chosen place of residence is blessed with. Some can also be found on the farmland that surrounds us, as well as along the riverine habitats that include our local wildlife reserve owned and administered by the Berks Bucks and Oxon Wildlife Trust (BBOWT Chimney Meadows).

We will all see the Mallard on the streams that run through the village, and my near neighbours have been host to a pair nesting on their garden wall. This nest site is at some height and my neighbours become more agitated than the ducklings themselves as these small bundles of down launch themselves to terra firma, invariably arriving safe and sound.

One of nature’s greatest sights is the mesmeric flash of outrageous blue that takes one’s breath away as the Kingfisher flies rapidly along our waterways, before settling on an oft-used perch to plunder Mother Nature’s harvest of Minnow and Stickleback. This bird would hold its own alongside almost anything the rainforest has to offer with the spectacular plumage it wears, and looks every bit the local dandy.

It may well be when you are walking the farmlands that you notice a small brownish bird, and no doubt your first thought will be Skylark but it may well be in fact a Meadow Pipit. They are very similar in plumage, and in winter especially both species form flocks as they search the stubble and grassland for those morsels of food that are the difference between starvation and salvation.

That cheeky, chirpy chappie, the House Sparrow, sporting a bold bib and noisily commandeering your garden is probably, due to familiarity, often overlooked. He, along with his somewhat plain wife, tuck into the food you have spread in and around your garden bird feeders. I suspect most of us think he is just a rather nondescript brown job but in truth he is a rather dashing fellow. If you look carefully it will become apparent that he does indeed wear an attractive grey mantle and plays the part of the local dandy with relish. Surprisingly both the Tree Spar row and the House Sparrow do not fit closely with the other species I have written about as the Sparrows are closely related to the Weavers. Yes – those incredible intricate nest builders of foreign lands! Now our own Weaver family members – and this is in the case of the Tree Sparrow – choose to nest mostly in holes in trees. They will take readily to nest boxes while the house sparrow will nest anywhere it can furnish its abode, with a

most untidy and straggly nest. They utilise holes and crevices under roof tiles and make use of any space left in buildings that they will adapt for purpose. Unfortunately, modern buildings are better designed from a human viewpoint and it is thought that this is a major factor in the decreasing numbers of House Sparrows. The nest site opportunities there once were are no longer available. The provision of joined-up nest boxes will possibly attract these noisy neighbours to your garden but be warned, this I did and they used them for several seasons, and then for no apparent reason abandoned them – and I still have no idea why.

Our parish is a stronghold for the now rare Tree Sparrow, a bird that is mostly extinct south of Oxfordshire but due to much work, by a team of volunteers, and expense, it flourishes at a few locations in our county. It is doing particularly well near Tadpole Bridge and other local sites that must remain secret for the wellbeing of the species.

Little Egrets have the whitest of white feathering and a long black beak. Surprisingly they have bright yellow feet often not seen as they prod and probe the farmland and wet places common around our Bampton lowlands. Along with the common Grey Heron, that huge looking bird with the dagger-like bill (unmistakeable when you see it flying across the skyline), they both sport a prominent head plume.

The Red-legged Partridge is common on our farmlands for they are released as sporting quarry for local shooting folk. The Bushy Row end of Bampton enjoyed close up views of a pair of these attractive gamebirds that visited our gardens in the winter of 2020/21. They became quite tame, utilising the grains that we had spread for other birds visiting our gardens. They have mainly replaced the English or Grey Partridge that was once common but was nearly wiped out in the very harsh winter of 1962/63.

Thankfully most shooters refrain from shooting them as they wish to see our native Greys proliferate. The Greys are more of a sporting challenge because as they come into range they explode in different directions, rather than flying over the guns in a straight line like the Red-legs tend to.

The Grey Partridge is staging a comeback and, along with that other gamebird the handsome Pheasant, can often be seen on local walks. There are many different strains of Pheasant to be seen locally as game farms have striven to produce the ultimate in high, fast-flying birds that will test the ability of the game shooter.

Two more birds you are likely to come across especially if you live close to the meandering streams that are a feature of beautiful Bampton are the red-capped Moorhen and the white-capped Coot. Moorhens used to be more common than they are now.

As a child, along with my sisters and brother, a special treat was an early morning search of the many ponds on my father’s farm and proudly presenting mother with enough Moorhen eggs for a rather tasty fry up. The eggs have a patterned shell of attractive squiggles and blotches. The Coot has greatly increased its population but mainly as a result of the many gravel workings in the County. After extraction has taken place the huge holes left behind gradually fill with water and it is in these lakes of assorted sizes that the Coot feels most at home, although you will see a few on the ponds and waterways of Bampton.

I very much hope I have managed to engage your imagination and soul to the wonder that is the natural world. I now dare you to be brave enough to embrace nature more on nature’s terms and less on our obsession with straight lines and tidiness. If we take time to reflect on the forces that drive our natural world, probably top of the list will be the overpowering need for a share of daylight and the eternal solar energy supply that, along with water, is essential for all life on our planet.

Because plants have to fight for their share of the life-giving daylight, left to their own devices they, by necessity, grow quite straggly. Then for some peculiar reason mankind in general feels a need to react against this and chop, shape and interfere, bringing nature under our power. This ‘power’ is usually misplaced especially if diversity is the key, not only to our gardens but the wellbeing of all living things on our planet. May I make a suggestion about the green space in your garden we call lawn? Instead of relentlessly trimming it and upsetting ourselves if that other gorgeous green plant – moss – takes over part of it, why not embrace it for where it appears? This marvellous plant is hard wearing, needs virtually no mowing, and will be-come home to life forms not at present enjoying an easy time at your hands, as you try ever more sophisticated means to eradicate it.

Another suggestion! Why not leave a third or half of your lawn un-mown for the next couple of years? What do I expect to happen? Never mind what I expect – it’s your lawn: just give nature a chance to pleasantly surprise you how other life forms, given the habitat, will respond in a way that will so enrich your life.

Of course there will be instances when some pest control is necessary. Rather than kill with harmful poisons using the synthetic formulas that will carry on killing lifeforms further down the line, try keeping those squelchy slugs and things away from the plants you wish to protect by using copper rings or Crop Protection Jelly that can be applied to the bottom of trees and plant containers. Many organic gardeners practice Companion Planting. Plants such as Marigold and Nasturtium planted between rows of vegetables will give a degree of protection. Yucca Extract in a spray form is also claimed to be effective against slugs etc without putting your wildlife at risk. Of course bird nest boxes will encourage the aphideating Tit family among others to eat enormous amounts of these insects.

Not least among the ways of encouraging your garden wildlife is the provision of untidy patches giving a home to Hedgehogs (they relish anything sluggish) and Slow-worms among other possible garden gems. To attract Slow-worms if you have the space, try laying sheets of corrugated tin or even old carpet on those garden edges.

Many gardeners who have done so have reaped the reward of attracting Slow-worms (a type of legless Lizard, although I must admit I know a few of my gardening friends who are quite capable of getting legless without any help from Lizards!)

The songs and calls of birds are quite a specialist area and it is for this you will find a link to other online organisations that give you the opportunity to listen and become familiar with the bird sounds of our Bampton environs.

I wish to take this opportunity to thank both Jo Lewington and Jenny Chaundy for the hard work they have put in to bring this book to fruition. Also to Andrew Mann for checking grammar and pre-editing. Andrew lives in Bampton from where he runs his informative bird walks given in a most agreeable and laid back manner (magicmomentswithbirds@gmail.com).

Thanks go to international bird illustrator Ian Lewington (no relation to Jo) for the wonderful bird illustrations he has generously allowed me to include and to Roger Wyatt for his super photographs that have been used when my own have not been up to the standard of his.

My reward will be if I receive feed-back that suggests my readers really do “get it” – the “it” being an appreciation of the natural world that is of the spirit, and not always capable of being put into words.

If you would like advice on protecting your bird feeding from Pigeons and assorted crows do please contact me.

Barry Hudson. 01993 200790 barhud@aves123.co.uk