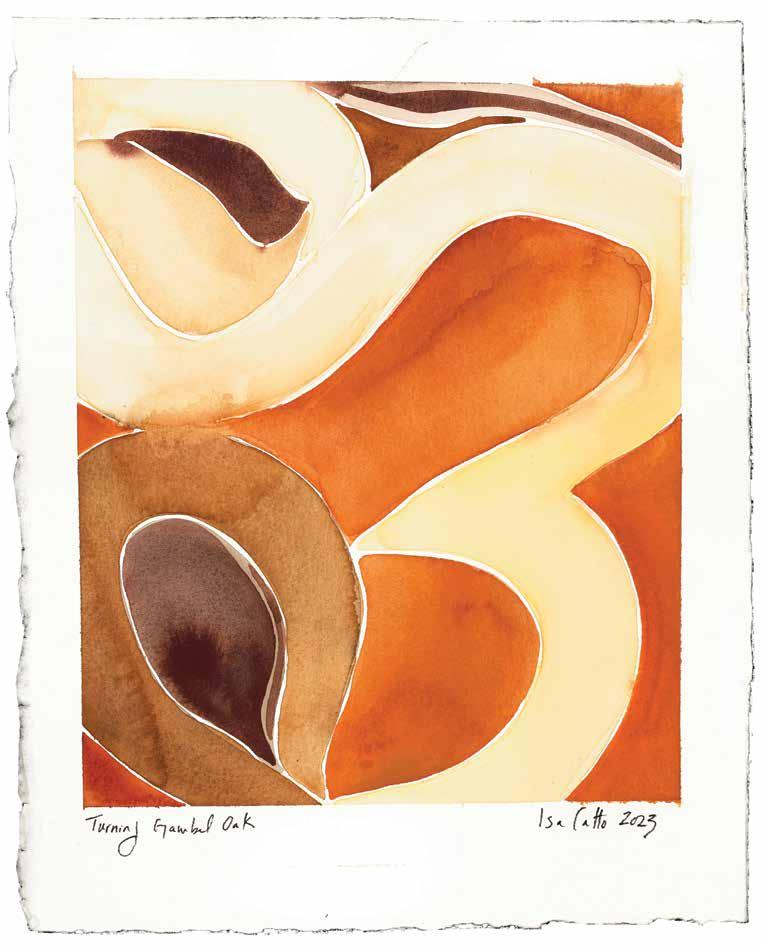

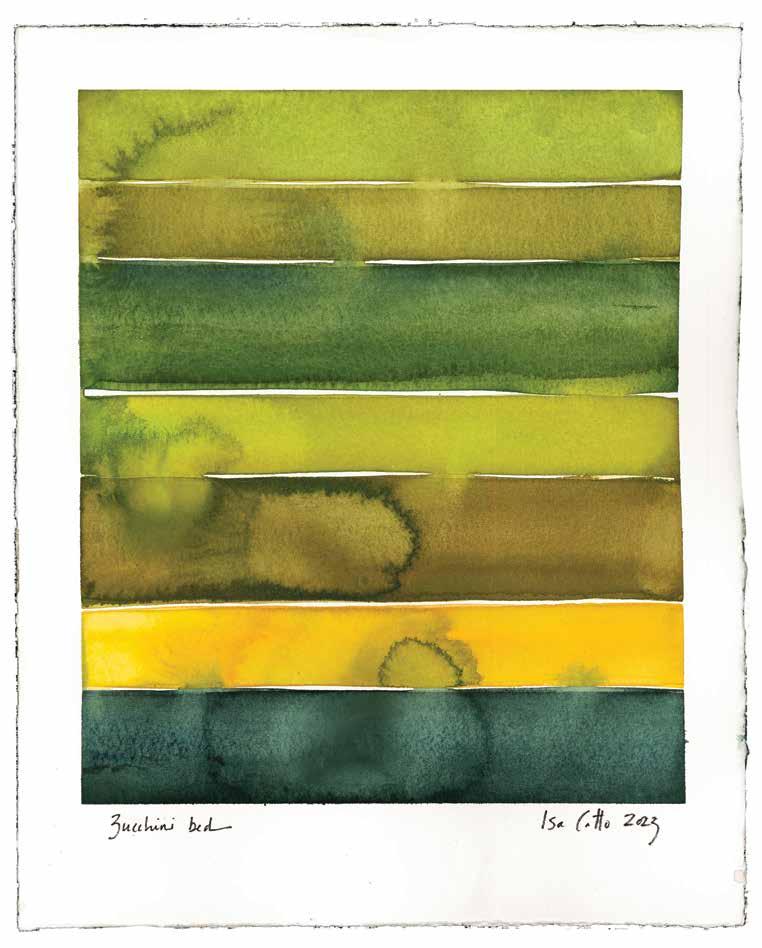

Learning to Look with Isa Catto

“Learning to look, for me, is a discipline,” Catto says.

On studying color:

“The best way to learn about color is to step outside and try to match colors or look at different combinations. Why do they work? Is it light? Do you see how they vibrate next to each other?”

On starting small:

“You don’t have to go up a fourteener to see wildflowers or sketch or take photos. Just do whatever taps you into this current of beauty.”

On the surrounding wilderness:

“There’s no other place like this in the states where there were these extraordinary women who lobbied Congress to have four wilderness areas. My hope is for people to get beyond the ski slope or the Rio Grande Trail and understand how that has shaped this place.”

On staying curious:

“I think it’s part and parcel of being an introvert, but I’m never bored. This is a fascinating world. As long as there’s the friction of ideas and imagery and the natural world, how could you possibly be bored?”

On reading in place:

A voracious reader, Catto is also inspired by poetry and literature. Some of her recent reads include What We Sow by Jennifer Jewel, The Sixth Extinction by Elizabeth Colbert, and Robert Macfarland’s The Lost Words . She also frequents the work of environmental journalist Michael Pollan and naturalists Margaret Renkl and E. O. Wilson.

34

Flavorful and nutritious, microgreens pack a big punch on local menus.

Small But Mighty Text by Amiee White Beazley

Images by Trevor Triano

Small But Mighty Text by Amiee White Beazley

Images by Trevor Triano

36

Chefs of the region turn to producers like Mesa Microgreens to infuse their dishes with big flavor.

It was a fairly easy decision for farmer Kaylin Harju to begin her business, Mesa Microgreens. In 2019, Harju and her family had moved to an acreage in Silt, Colorado, about an hour from Aspen on the Western Slope. Wanting a crop that was easy grow, required little room, and could supplement the family income, Harju saw a big opportunity in small produce: microgreens. She immediately turned her attention to the 625-foot garage on the property: “I cleaned it up, epoxied the floors, installed the lights, and got started.”

The daughter of Minnesota gardeners, Harju already understood the challenges she would face with her microgreens venture—mold and disease,

a constant grow-harvest cycle—but it was the consumer confusion surrounding her product that gave her pause. “A lot of people call me ‘the sprout lady’ because they think what I’m selling are sprouts,” Harju says of her of encounters with curious shoppers at farmers markets. “They take a look at the microgreens, get confused, and ask, ‘How do I eat these?’”

Microgreens aren’t lettuce or sprouts, Harju explains. By definition, a microgreen is the first green of a vegetable—be it cilantro, basil, pea, radish, or one of dozens of other varieties. According to Harju, the small wonders are like a cross between a sprout and a baby green, with a versatility reminiscent of spinach.

At Mesa Microgreens, they begin their journey as seeds planted in stacked trays of rich soil. Under artificial sun from grow lights, shop heaters, and LEDs, seedlings are coaxed from their shells in a carefully controlled, lowhumidity indoor environment that’s kept at a moderate temperature of 70 degrees. Growing time varies by microgreen, but the more basic varieties, like pea, radish,

sunflower, broccoli, kohlrabi, and kale, take under two weeks to grow.

Once harvested, the microgreens are immediately packaged to sell. This short cycle from seed to germination to consumption means that every microgreen is nutritionally dense and packed with intense flavor. Some research suggests that microgreens provide up to 40 times more nutrition than their larger, more mature plant counterparts, offering cancer-fighting properties and protein as well as vitamins A, B complex, D, and E, calcium, iron, magnesium, and other nutrients. “Imagine eating an entire head of broccoli and benefiting from all of those vitamins and minerals,” Harju says. “With microgreens, you can get all of those super nutrients in a handful of sprouts on your salad or your sandwich.”

It bodes well for Harju’s “budding” enterprise that they’ve become less of a novelty and more of a staple on restaurant menus and in home-cooked meals. “Growing food is what I like to do,” she says. “But my real job is getting everyone to eat microgreens and making them accessible.”

40

Learn why chefs and home cooks are looking to the petite greens to infuse their dishes with massive flavor.

Mysterious Greens

When Harju first began selling her microgreens at the New Castle Farmers Market, there wasn’t much sales traction. Harju realized she simply needed people to try them: “I’d give them the crunchy ones—sunflower or pea—and get them hooked.”

Choose Local

“Part of our mission is to highlight, promote, and advance the rock stars of farming and small-scale agriculture,” says Tiffany Pineda-Scarlett, co-owner of The Farmer and Chef, a private catering company that runs the Rooftop Café at the Aspen Art Museum. Mesa Microgreens are featured throughout the café’s menu offerings, including its signature entrée—a Peruvian-style roasted chicken that’s brined then marinated with a citrus, tamari, garlic, and pepper emulsion. The dish is topped off with a medley of microgreens—fresh cilantro, basil, mint, and whatever else is in season. “We want our guests to know how delicious locally grown food is,” Pineda-Scarlett says.

A Feast for the Senses

Part of the magic of microgreens is their wide variety of colors, tastes, and textures. Options abound: “The radishes are nice and spicy, the beets have a deep flavor, and the cilantro is super bright and fresh,” says Joey Scarlett, PinedaScarlett’s husband and co-owner of The Farmer and Chef. Emma Kottenstette of Farm Runners, a regional food distributor of family farm-grown produce, meats, dairy, and eggs, echoes the sentiment: “Micro popcorn shoots, red amaranth, and garnet mustard add a pop of color and a burst of flavor to elevated dishes.”

Where To Find

“Mesa Microgreens is a great asset for our high-end clientele looking for specialty items,” Kottenstette says. “The dozen or so varieties of microgreens grown in Harju’s garage remain in high demand.”

A small but prized ingredient, Mesa Microgreens are featured in restaurants throughout the valley, including Aurum in Snowmass and The Pullman in Glenwood Springs, along with PARC, Meat & Cheese, Bosq, and Element 47 in Aspen.

42

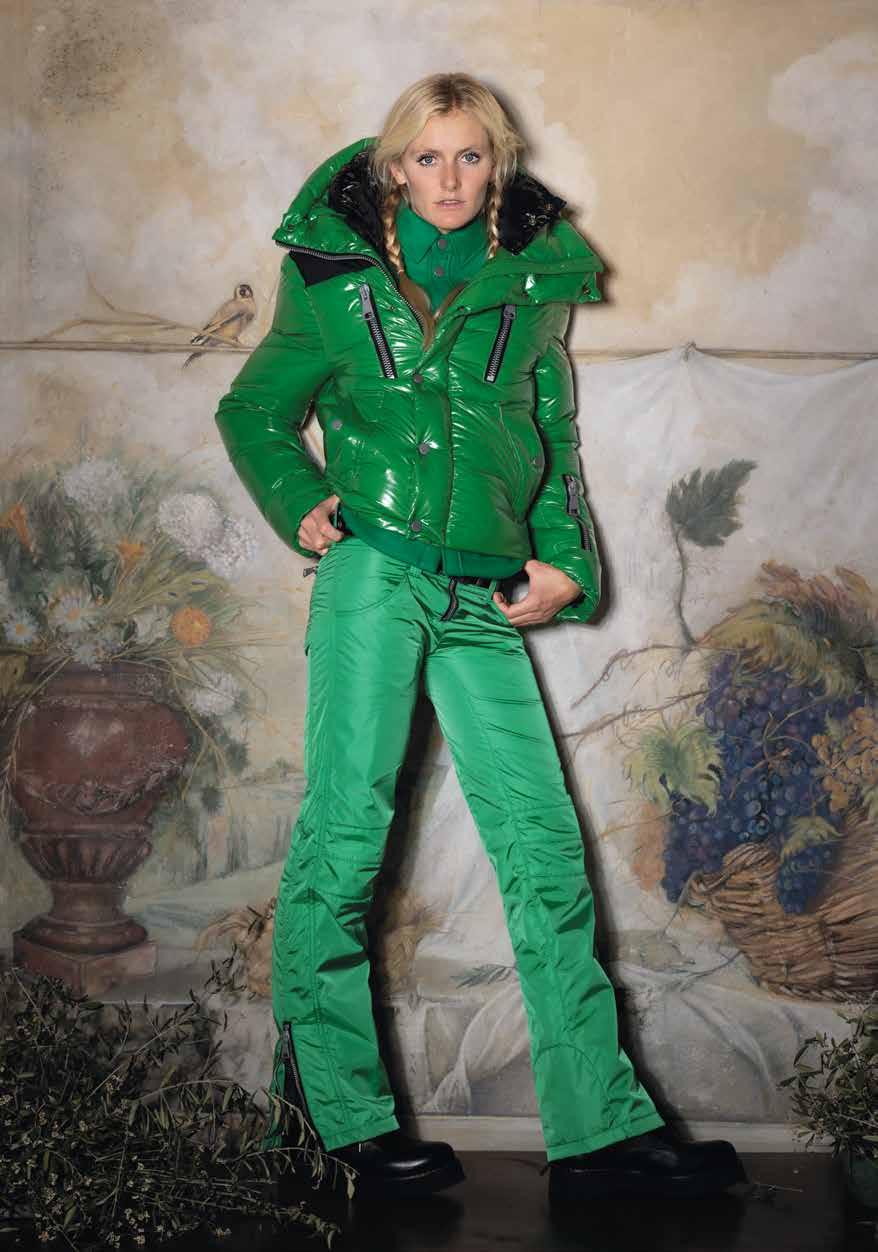

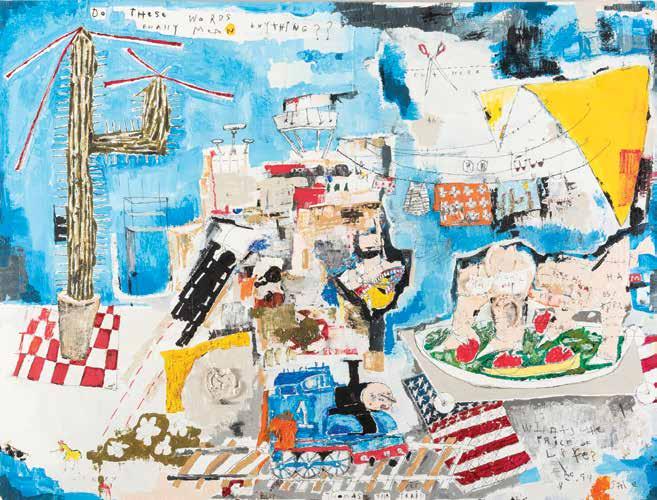

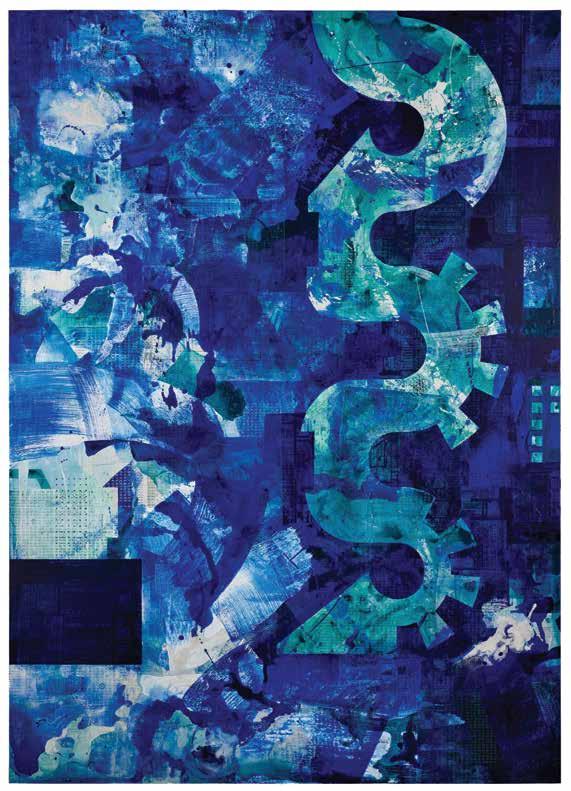

BACK COUNTRY by Simon Bull | Acrylic on Canvas | 48 x 48 Meuse Gallery showcases the artwork of Simon Bull, Bekah Bull, and KURZ Complimentary Services: Virtual Room Renderings Delivery + Installation Home Shows Worldwide Shipping Meuse Gallery 601 E Hyman Ave, 2nd Floor, Aspen, CO (831) 293-4801 meusegallery.com Also in: Carmel, CA Saint Helena, CA

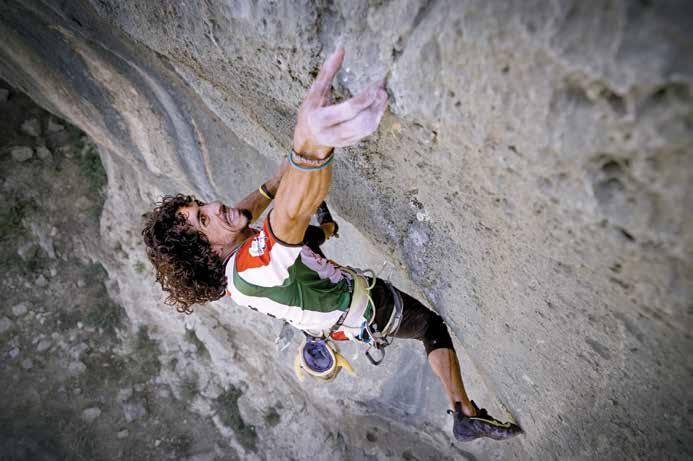

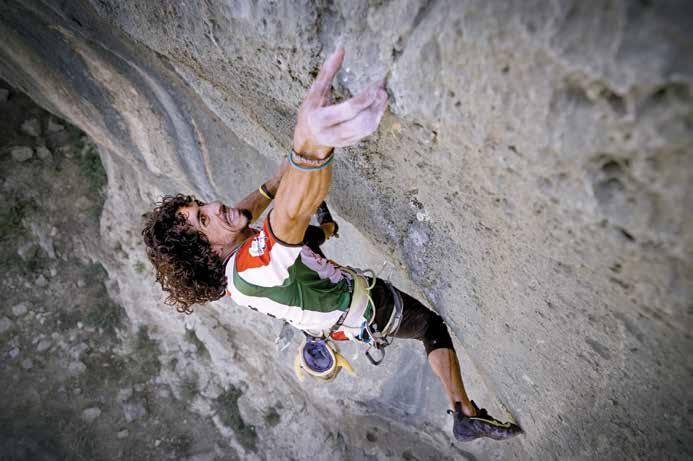

For the Love of Climbing Text and images by Kersten

A Colorado climber ventures to Palestine to explore how the sport has brought light to a community in need.

Andrew Bisharat believes his best climbing days are behind him. A former die-hard climber, the father of two admits to spending less time lately giving his favorite sport routes a burn at his local crag of choice (Rifle Mountain Park) and more time burning through repeat viewings of How to Train Your Dragon . Alluding to a rotator cuff injury that sidelined him for seven months, he jokes, “I’m kind of in that middle-aged phase of life when I wonder if I should just give up everything I love.”

Bisharat’s disillusionment from climbing comes after more than 20 years consumed by a love for the sport. His long career in climbing saw him advancing to harder and more impressive climbs while nurturing his passion for climbing as an accomplished writer and editor, working as a senior staffer

44

Vasey Bowers

Film stills courtesy of Resistance Climbing

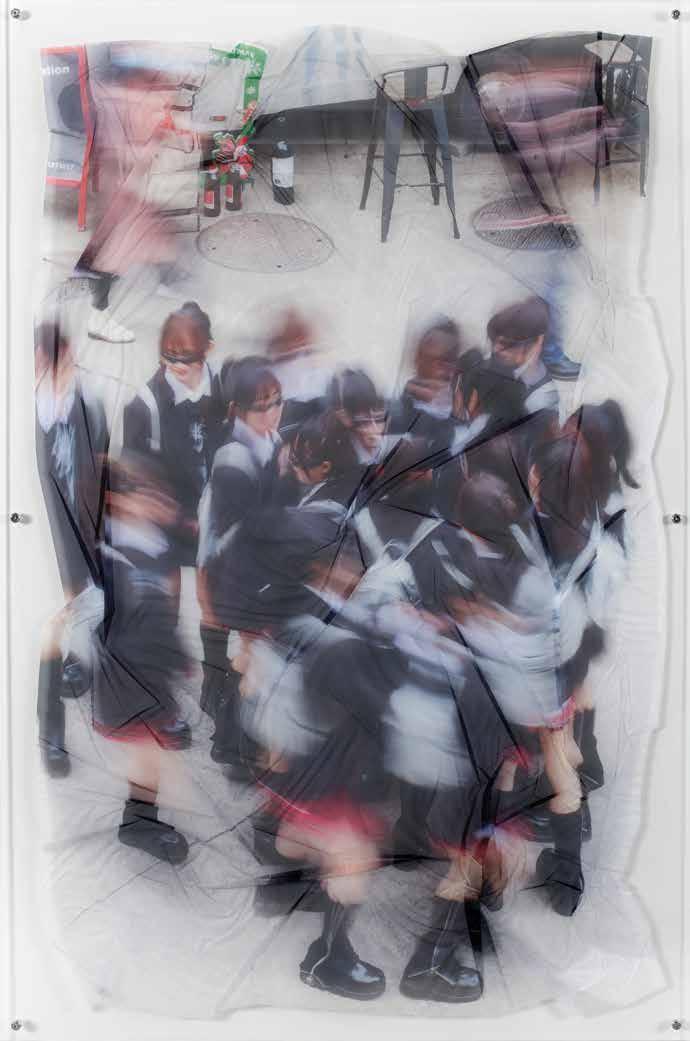

Resistance Climbing (2023) follows Andrew Bisharat to the Israeli-occupied West Bank to climb newly established limestone walls with the locals.

Resistance Climbing (2023) follows Andrew Bisharat to the Israeli-occupied West Bank to climb newly established limestone walls with the locals.

48

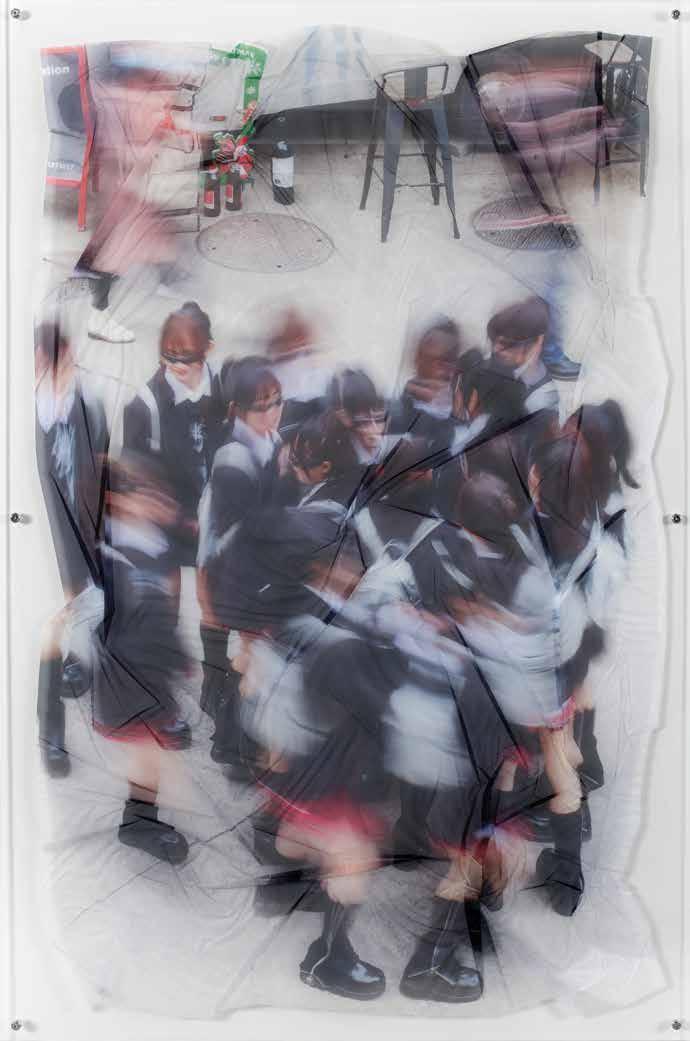

Scenes from the short film Resistance Climbing, which made an impression on writer Kersten Vasey Bowers for humanizing the people of Palestine and depicting a “softer” side of Arab men rarely seen in mainstream media.

for the climbing publication Rock & Ice and covering adventure sports for National Geographic, The New York Times, and Outside magazine. (He also runs the popular climbing website Evening Sends and co-hosts The RunOut Podcast with friend and Carbondale climber Chris Kalous.)

Over the years, Bisharat had been approached by several filmmakers interested in working together, but none of their proposals were as compelling as the one that came from outdoor adventure film company Reel Rock and climber Tim Bruns, an American who lived in the Israeli-occupied West Bank of Palestine from 2014 to 2017. Bruns had moved there partly to begin developing the limestone walls he’d scoped during travels to Palestine while studying abroad in Jordan. He introduced many locals to climbing, hosted regular climbing meetups, and established the West Bank’s first climbing gym, Wadi Climbing—later turning the gym over to the locals. “He just genuinely believed in the power of climbing,” Bisharat says.

After consulting with friends and relatives, Bisharat realized that teaming up with Bruns to document the West Bank’s budding climbing scene was a rare opportunity for the rest of the world to see Palestinians as they might

see themselves: as climbers, as friends, as real people. For Bisharat, it was also an opportunity to bear firsthand witness to Israeli occupation of his ancestral homeland, and to finally visit the place his grandfather was exiled from during the 1948 Nakba, when hundreds of thousands of Palestinian Arabs were violently displaced by Zionist militias and Israeli armed forces during the Arab-Israeli war.

But the project wasn’t without its risks. At one point in the film, an interview with Hiba Shaheen, president of the Palestine Climbing Association and a regular at the climbing area at Ein Fara, is interrupted by the sound of gunfire. The interview ends, and the crew begins the long hike back around the adjacent Israeli settlement, one of many that dominate the West Bank.

Later, viewers meet Faris Abu Gosh, a local climber named after Faris Odeh, the 14-year-old boy who became a symbol of Palestinian resistance after he was photographed throwing a rock at an Israeli tank during the Second Intifada in 2000, and who was made a martyr when he was later shot and killed by an Israeli soldier. “I don’t want to end up like that,” Abu Gosh says in the film. “I can’t always just be fighting. I want to live as well.”

50

Urwah Askar is a regular at Palestine’s Ein Fara climbing area. The Palestine Climbing Association was recognized as a member of the International Federation of Sport Climbing in 2024.

Urwah Askar is a regular at Palestine’s Ein Fara climbing area. The Palestine Climbing Association was recognized as a member of the International Federation of Sport Climbing in 2024.

Bisharat’s family is pictured outside their home in West Jerusalem. The home is now sequestered in a wealthy Israeli neighborhood formerly occupied by the late Prime Minister Golda Meier.

Bisharat’s family is pictured outside their home in West Jerusalem. The home is now sequestered in a wealthy Israeli neighborhood formerly occupied by the late Prime Minister Golda Meier.

As the crew delved deeper into how Israeli occupation affects daily life for the film’s Palestinian subjects, the project evolved from a climbing documentary to a story about the resilience of the human spirit. “There’s an act of resistance inherent in every single aspect of life in Palestine,” Bisharat says.

Violence has since increased sharply in the West Bank. Many of the walls featured in the film are no longer safe to climb. Resistance Climbing likely couldn’t have been made after the attacks of October 7, 2023. Bisharat went into the project questioning his devotion to climbing, and he admits he feels some of that same ennui as the indisciminate killings continue in Palestine. Still, he is encouraged to see how the sport has changed the lives of the Palestinian climbers he befriended. Several were able to travel to the U.S. for screenings of the film in 2023, and together they climbed all over Colorado, cooked Palestinian food, and—in true American fashion—spent hours in Target.

After all, Resistance Climbing is as much about the will to live as it is the will to climb, full of laughter and celebration, affection and camaraderie. In one scene, Abu Gosh is seen dancing the tango, a passion he indulges when he isn’t meeting the West Bank group for climbs at their home crag. They still climb together every Friday—to gather, to cope, to feel free.

56

ASPEN / RED MOUNTAIN INCREDIBLE VIEWS | 5 BED | 4.5 BATH | 3 CAR GARAGE Stephanie Lewis Luxury Aspen Broker | 970.948.7219 stephanie@stephanielewisre.com Embrace infinite panoramas of the mountains, enjoy endless sunshine, inspiring sunrises/sunsets, discover the peace and tranquility from this exceptional legacy property, all within 5 minutes to downtown Aspen. 804HunterCreekRoad.com

58

Dining al fresco on the mesa.

Image by Irene Durante

Savor

The vintners behind The Storm Cellar winery and vineyard embrace the adventure that is the Colorado wine industry.

60

Uncharted Territory Text by Carey Jones

Images by Irene Durante, Skyler Lahood, and Olive & West Photography

Within five years of venturing into the Wild West of wine, Jayme Henderson and Steve Steese of The Storm Cellar claimed the award for Colorado winery of the year.

It was a simple question, posed by a colleague in 2016, that changed the life trajectory of Denver-area wine professionals Jayme Henderson and Steve Steese, the husband-and-wife couple behind The Storm Cellar, named Colorado’s Winery of the Year in 2022 by the Colorado Association for Viticulture and Enology. “We’re at a dinner with a bunch of sommeliers, and someone in the California wine industry asked us, ‘What’s happening in Colorado wine?’” Henderson recalls. “And, embarrassingly, we didn’t have an answer.”

Research ensued, sparking a passion and a swift career shift. “Ten months later,” she says from their property in Hotchkiss, overlooking the farmlands of the North Fork Valley, “we’d closed on this place and were out here pruning vines.”

Once they’d gotten a taste of the unpredictable, pioneering, relentlessly experimental Colorado wine world, they were hooked, and The Storm Cellar was born. “There’s an energy in Colorado winemaking that’s palpable,” Henderson says. “It’s exciting to be a part of.”

Many of the world’s great wine regions are mountainous. But Colorado, as ever, is extreme. Growing vines on gentle 1,000-foot slopes in Napa’s Mayacamas mountain range, terraced vineyards at 2,000 feet in Alto Adige, or even the perilous inclines of Germany’s Mosel simply doesn’t compare to farming at more than a mile above sea level. “Our vineyard is at about 6,000 feet,” Steese says, “which, in the Northern Hemisphere, is absolutely uncharted territory. The only other place in the world growing at that elevation is Mendoza in Argentina.”

Usual methods of growing, harvesting, and even fermenting do not apply, Steese says: “Nothing is textbook.” Such singular conditions force Colorado winemakers to be adaptable. The defining philosophy is bold, experimental, and open-minded. “People are embracing a Wild West mentality,” Henderson says, whether that means different wine barrel styles, different pét-nat and sparkling wine styles, or little-known hybrid grapes.

When Henderson and Steese first visited the vineyard property that would become The Storm Cellar, it was in a state of decline, with prolific

vines but long-neglected infrastructure, no winemaking equipment, and no tasting room. “We did not buy a winery,” Steese says. “We bought a farm.”

But the captivating views immediately drew them in. Situated on the mesa perched 500 feet above the North Fork Valley floor, looking past that valley to the 12,000-foot peaks of the West Elk Mountains, “It spoke to us,” Henderson says. “We’ve both been all over the world for winery visits and internships, but the beauty and majesty of this place is just unparalleled.”

Focusing on white and rosé wines, their style is bold in acidity and lively on the palate, embracing the complexity of Colorado-grown grapes. “Our goal from day one has been to make worldclass wines in Colorado,” Steese says, “to see what Colorado really can do.”

Already tasked with building a winery and tasting room from the ground up, however, Henderson and Steese were dismayed to find that many of their vines were unviable. It was thought that the notorious pest Phylloxera, responsible for decimating the 19th-century French wine industry and a scourge on vineyards to this day, couldn’t survive in Colorado’s climate, Steese explains, “and as a result, almost all of Colorado’s vineyards are planted on ungrafted rootstock, making them susceptible to that pest.” The theory was disproved just as they closed on the property, appearing in Colorado and soon in their own vines, requiring them to replant everything but a section of Riesling.

64

The Storm Cellar partners with Forage Sisters, a field-to-table catering company, to host al fresco wine dinners on the vineyard.

The Storm Cellar partners with Forage Sisters, a field-to-table catering company, to host al fresco wine dinners on the vineyard.

Even by Colorado wine standards, The Storm Cellar’s vineyard is quite high in elevation. In an alpine desert climate Steese calls “fringe,” everything comes in extremes. Frosts arrive as late as Memorial Day and as early as mid-October, leaving a short growing season. UV light is more intense at elevation, yielding grapes with thicker, more protective skins. (It’s one reason that The Storm Cellar focuses on whites and rosés—little or no skin contact.)

Yet everything, from the high sun exposure to the steep vineyard slopes to the dry winds, contributes to the success of the resulting wines. “The desert is actually a great place to grow wine,” Steese ventures, “as long as you can get water there.” California wine friends ask what they’re doing to stress their vines; do they dry-farm?

“Everything stresses the vines here,” he laughs. “We don’t have to try.”

Grapes thriving in Colorado’s two AVAs include marsanne, roussanne, and viognier; Steese has high hopes for albariño, considering “varieties that thrive in parts of Spain or the southern Rhône Valley, specifically, really find a place in Colorado.” They also work with cold-hardy hybrids such as Itasca, “touted as the game-changing white hybrid variety,” tolerant of temperatures as low as 35 degrees below zero. “So even in the worst possible year,” he says. “we’ll get something.”

In the bottle

On The Storm Cellar estate, and within its own portfolio, riesling has emerged as the flagship variety—a perennial favorite of sommeliers for its ageability, food-friendly nature, and razor-sharp acidity. But rather than presenting a ripe stone fruit note, “ours is more like an underripe peach,” Henderson says. “And we tend to get a lot of floral notes, often a chamomile note.”

It was this wine that The Little Nell’s wine director, Chris Dunaway, first chose for the list at Element 47, a particular source of pride for Henderson and Steese. “So often with winemaking, your nose is to the grindstone,” Henderson says. “Getting on a list like Element 47—those moments affirm that you’re doing something right.”

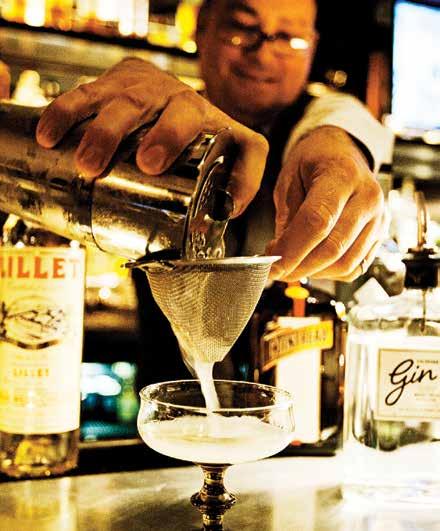

Even in their new roles as vintners, Henderson and Steese operate with a sommelier’s mindset. Wines are made with a focus on how they’ll be served at the table, specifically in the context of fine dining. “As sommeliers, we know the impact of that moment when a great wine is experienced in an amazing situation, with amazing food,” Steese says. They’re also attuned to the care with which their wine is treated and described to customers. As Henderson puts it, at top-tier accounts, “you know that your message will be translated and given a new life.”

68

The Storm Cellar’s alpine desert landscape is part of the reason it specializes in white and rosé wines.

The Storm Cellar’s alpine desert landscape is part of the reason it specializes in white and rosé wines.

On the Vineyard

There’s a lot happening at The Storm Cellar in 2024: the release of its first two sparkling wines—a dry sparkling riesling and a co-ferment of riesling and local organic apples—and the first harvest from its replanted estate vines. And Henderson and Steese continue to experiment to determine the varieties best suited to their estate’s unique terroir.

But what excites them most of all is welcoming visitors to the vineyard and tasting room—hosting summer events like Friday steak nights, wine-release parties, chef-led wine dinners, and the always-popular Asado on the Mesa, their fire-cooked communal meal series with wine pairings. Set against an unparalleled backdrop along the Western Slope, the hope is for people to discover not just The Storm Cellar vineyard, but the whole North Fork Valley.

“This valley of farms and orchards and pastures is the organic hub of the whole state,” Steese says. Henderson adds, “This amazing corner of Colorado is really gaining a sense of community. And a lot of people who come to visit Colorado want to taste what Colorado has to offer.”

The Storm Cellar will be the featured winery partner for The Little Nell’s Ride + Dine dinner on September 10. Details can be found online.

As former sommeliers, Henderson and Steese bring a uniquely experiential perspective to winemaking.

72

Creative Cosmos

Text by Andrew Travers

Images by Sarah Kuhn, Olive & West Photography, Benjamin Rasmussen, and courtesy of the artists and galleries

Creative Cosmos

Text by Andrew Travers

Images by Sarah Kuhn, Olive & West Photography, Benjamin Rasmussen, and courtesy of the artists and galleries

Luminaries of Aspen’s art scene weigh in on the most exciting artists, exhibitions, and trends of the moment.

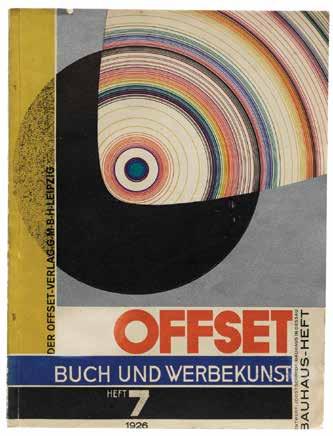

75

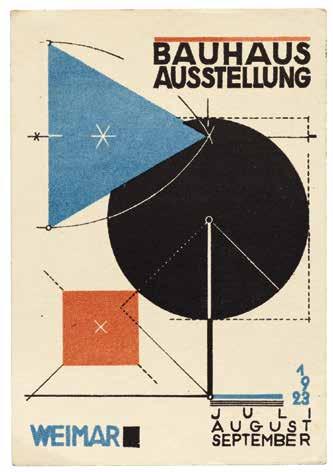

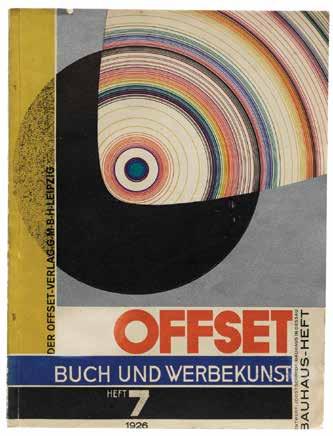

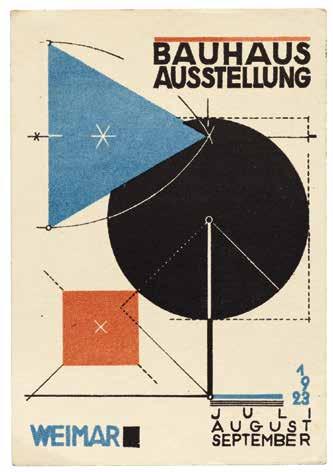

Lissa Ballinger

Executive Director of the Bayer Center at the Aspen Institute

A longtime Aspen-based curator and champion of the Bauhaus and modernism’s local footprint, Ballinger has been a caretaker of the Aspen Institute’s artworks long before it established a world-class museum in honor of legendary artist and designer Herbert Bayer. Ballinger, now overseeing a year-long exhibition on Bauhaus typography as director of the Institute’s Bayer Center, says artists and art organizations are collaborating in unprecedented ways and are shaping the future together.

“All of us are recognizing how dependent we are on each other’s success, and that our collective strength is much more formidable than our independent initiatives and successes,” she says, noting that entities large and small are teaming up. She points to innovative examples like The Art Base’s process-forward exhibition with artist Reina Katzenberger and the Aspen Chapel Gallery’s group shows benefiting local-serving nonprofits.

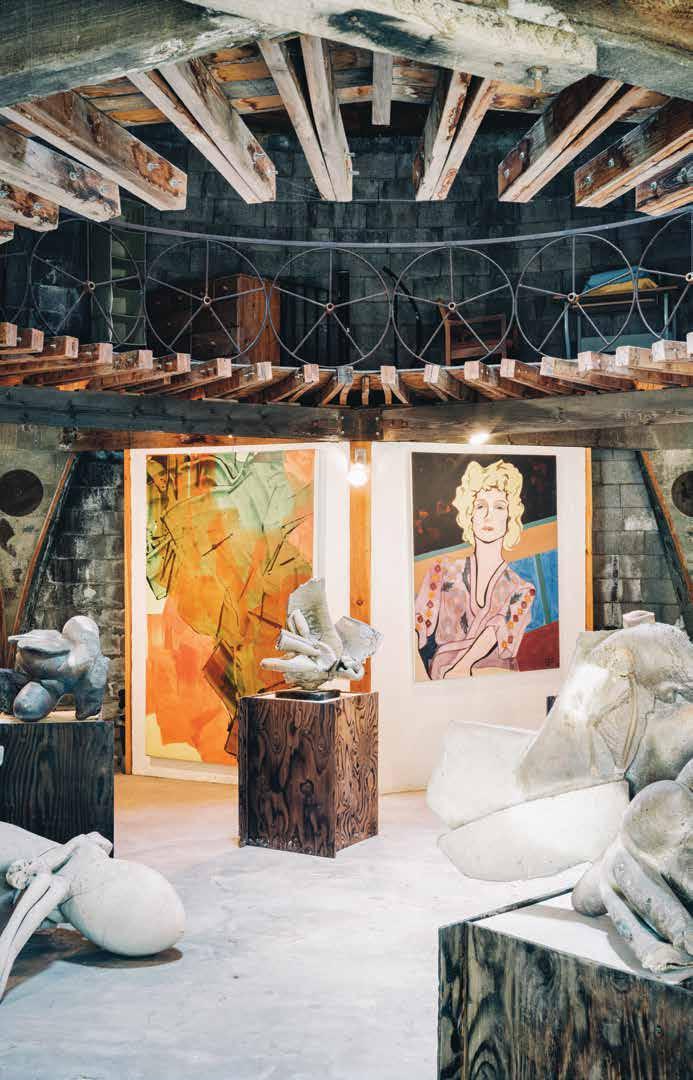

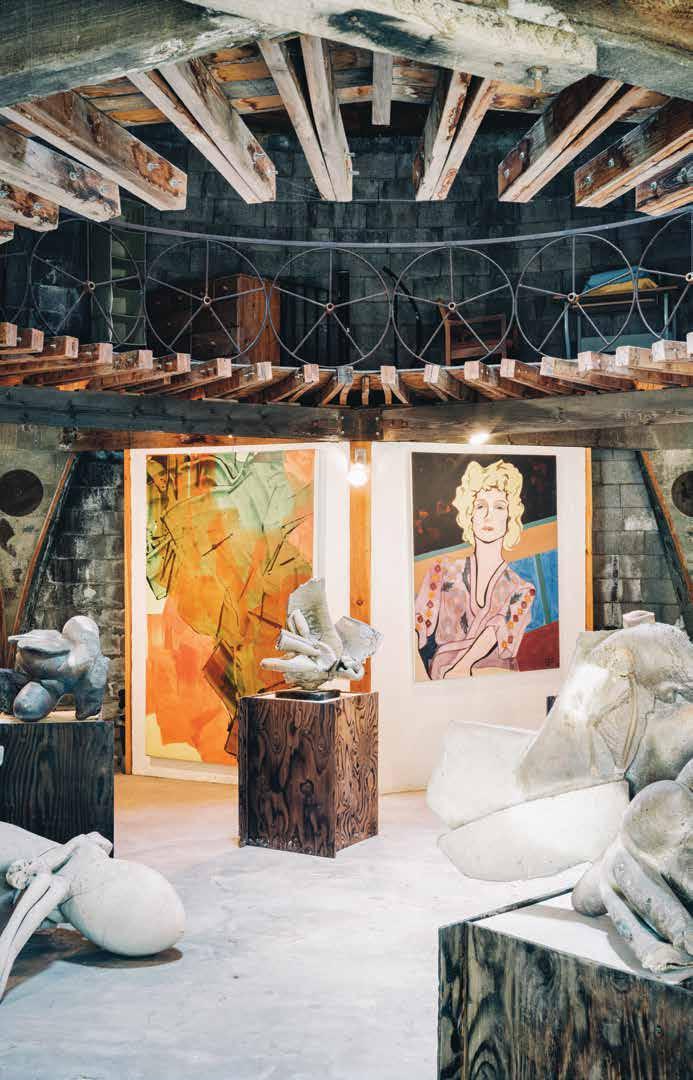

Ballinger says she is also anticipating a collaboration-driven public art movement in Aspen, galvanized by the nonprofit Buckhorn Public Arts and the city of Aspen’s burgeoning public art program. She predicts the Soldner Center will emerge as a space to watch for innovation in the years to come. It is now in its third summer of welcoming the public into the astoundingly preserved Aspen home and studio of the late ceramicist Paul Soldner, with Soldner’s daughter, Stephanie, at its helm.

76

DJ Watkins

Founder of Fat City Gallery, Aspen Collective, and Aspen Mountain Artist Residency

As a curator, author, and advocate, DJ Watkins has looked to Aspen’s artistic and countercultural past to inspire those of us living in its present. For more than a dozen years in books and itinerant galleries, he’s illuminated the present by shining a light on the likes of printmaker Tom Benton and gonzo journalist Hunter S. Thompson, alongside emerging envelope-pushing artists like Axel Livingston.

Two summer 2024 initiatives, both years in the making, gave Watkins the chance to boost local artists’ careers and inspire new work. “I think there are still great artists here, and when artists come here from elsewhere, they make incredible work because Aspen is such an inspiring place,” Watkins says.

His latest gallery, the Aspen Collective, housed in the Wheeler Opera House,

78

Clockwise from top left, an installation view of Leah Aegerter’s “Once a River” solo exhibition at The Art Base in 2023; Aspen-born artist Samuel Prudden at his studio in Valencia, Spain; Prudden’s recent works.

opened in May 2024 with a commitment to primarily show and sell work by local artists. His nonprofit Aspen Mountain Artist Residency launched in June 2024, hosting working artists for residencies in rustic cabins on its sprawling 200plus acres of Eden-like wilderness on the backside of Aspen Mountain.

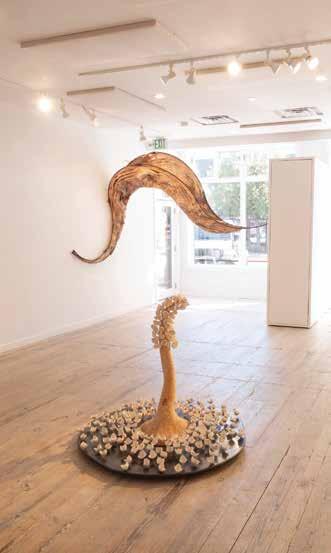

So, which Aspen artists did Watkins first tap for shows at the Aspen Collective? His picks include sculptor Leah Aegerter, painter and sculptor Chris Erickson, painter Samuel Prudden, multidisciplinary artist Whit Boucher, and ceramicist and gallerist Sam Harvey, who is curating a series of fall exhibitions for the gallery.

The residency and the gallery are designed to feed off of one another in the years to come. “The idea is that the artists can get into nature, disconnect from technology, have studio space and materials to create work,” Watkins explains. “Then I’ll be showing that work in the Wheeler Opera House.”

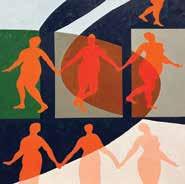

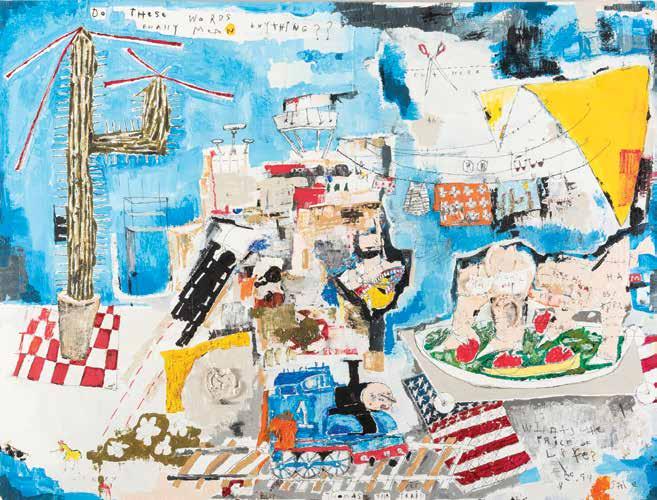

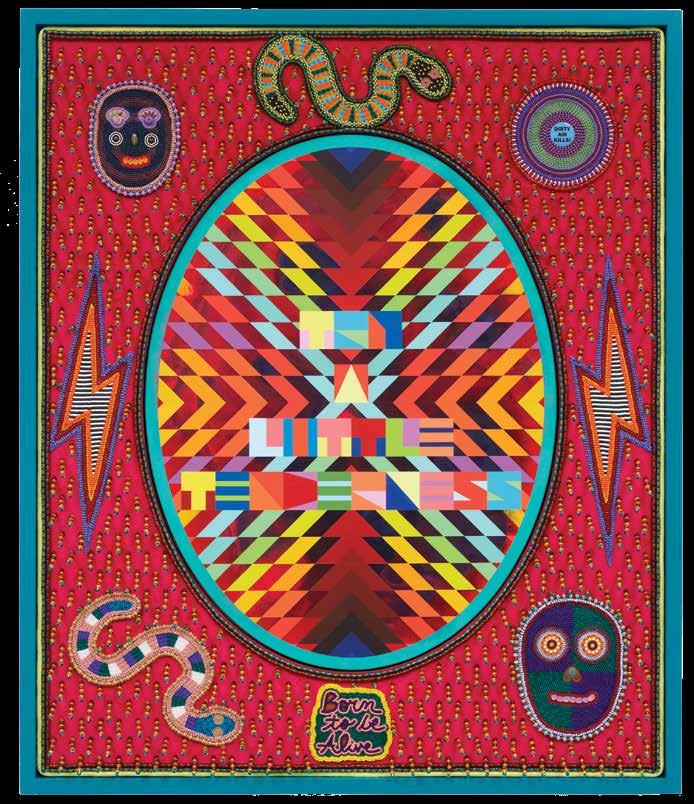

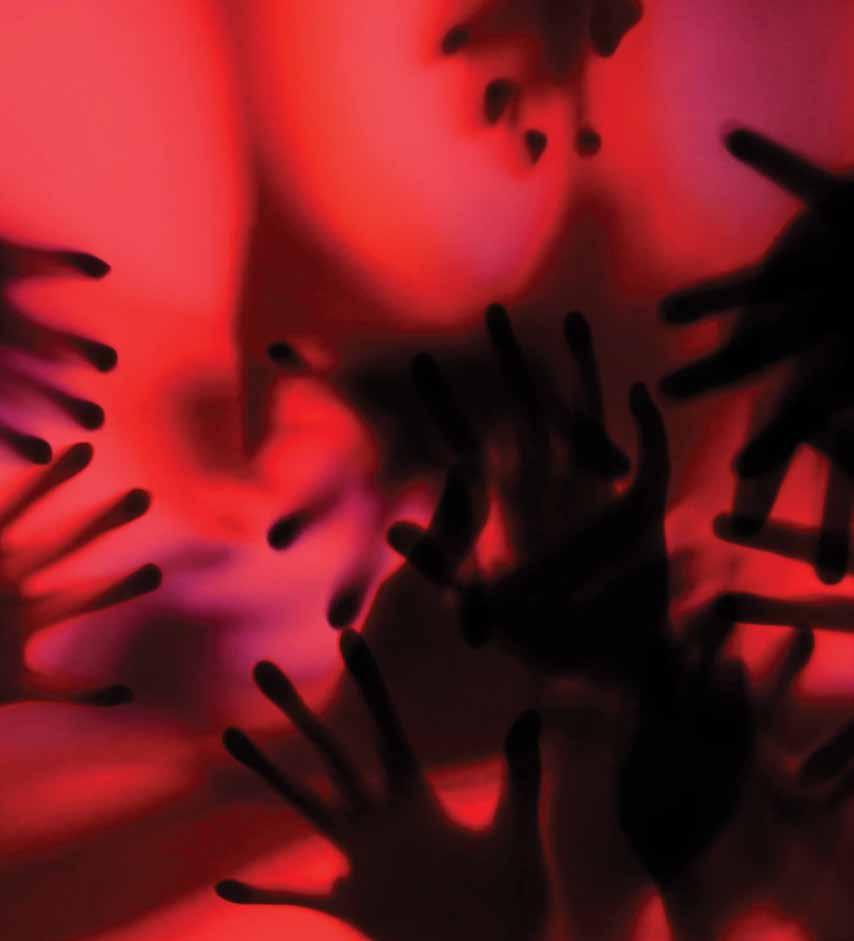

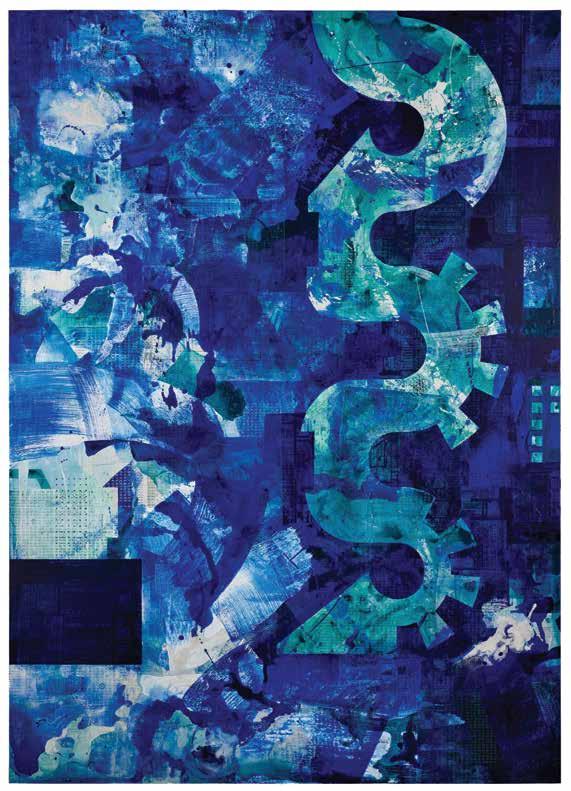

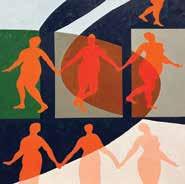

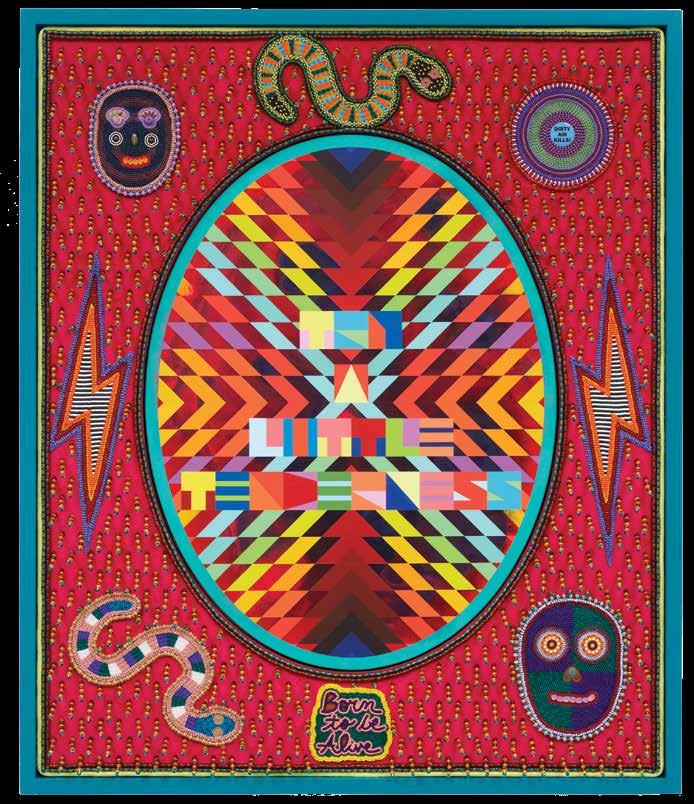

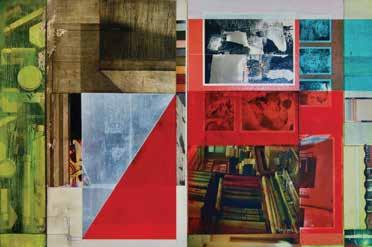

Below, Axel Livingston’s Valley Dump (2021). On opposite page, Jeffrey Gibson’s Try A Little Tenderness (2023), courtesy of Sikkema Jenkins & Co.

Below, Axel Livingston’s Valley Dump (2021). On opposite page, Jeffrey Gibson’s Try A Little Tenderness (2023), courtesy of Sikkema Jenkins & Co.

Robert Casterline & Jordan Goodman

Co-owners of Casterline|Goodman Gallery

Contemporary Native American art has commanded the interest of the commercial art market, along with the acclaim of critics and curators, in 2024. But the partners behind Casterline|Goodman Gallery note that Indigenous artists were being celebrated in Aspen even before events like the Phillips auction house’s blockbuster 60-artist contemporary Native American art sale made art-world headlines in January 2024.

Jeffrey Gibson made history this year as the first Indigenous artist to represent the U.S. at the Venice Biennale, soon after making his mark locally with the

2022 installation, performance, and Aspen-based film The Spirits Are Laughing at the Aspen Art Museum. Casterline|Goodman is showcasing artists like John De Puy and John Nieto, and the owners have enjoyed connecting collectors with Native American artists whose work has traditionally been undervalued and marginalized.

Casterline compares it to the days when the gallery was selling underappreciated Yayoi Kusama paintings for $200,000, with moneyback guarantees if collectors weren’t happy with the pieces within a year. (You couldn’t buy them back for ten times that amount today, he laughs.)

The pair name-checked other Aspen galleries, including Galerie Maximillian, Baldwin Gallery, and Hexton Gallery, along with new entrants like the New Aspen Art Fair by 74tharts, noting each has a unique curatorial perspective but all have a competitive spirit that keeps them sharp and ahead of the trends. “The local scene always runs parallel with the national scene,” Goodman says. “Culture is the core of the town, so it permeates everything.”

82

Above, Jeffrey Gibson’s People Like Us (2019), courtesy of Sikkema Jenkins & Co. On opposite page, a photo courtesy of Casterline|Goodman of Daniel Yocum, a Tennesseebased artist recently signed by the gallery.

Sterling McDavid

CEO and Founder of Sterling

Sterling McDavid

CEO and Founder of Sterling

McDavid Design

Sought-after designer and art collector

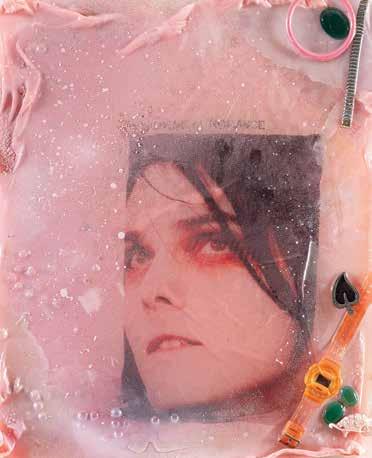

Sterling McDavid has honed her aesthetic chops curating her family’s contemporary and modern art collection, which includes Andy Warhol Campbell’s Soup Cans , a Richard Prince, and a large-scale KAWS sculpture. The next big thing on her radar is the Aspen Art Museum’s Shuang Li exhibition, “I’m Not,” opening in November 2024.

Following the museum’s ambitious museum-wide Allison Katz show, McDavid predicts “I’m Not” will be a landmark show for Aspen and for Li.

“Her video work Æther (Poor Objects), which was included in the 2022 Venice Biennale, very much felt like an arrival for the artist,” McDavid says. For the Aspen show, co-commissioned with Swiss Institute, Li is creating

84

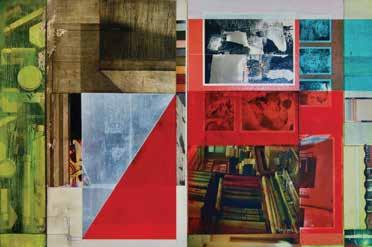

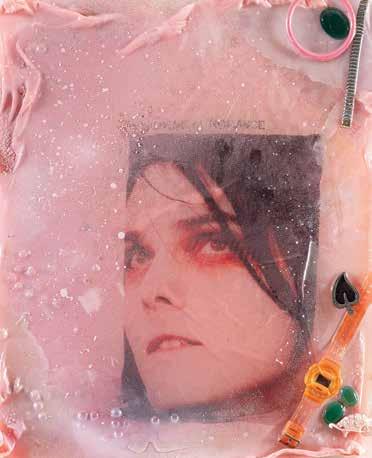

Above, Shuang Li’s Stand up fucking tall, don’t let them see your back (2022). On opposite page, The portrait of the Artist as a young man (2023) and Heartbeats Pound Softer (2022), courtesy of Peres Projects.

Above, Shuang Li’s Stand up fucking tall, don’t let them see your back (2022). On opposite page, The portrait of the Artist as a young man (2023) and Heartbeats Pound Softer (2022), courtesy of Peres Projects.

86

A still from Shuang

Heart is a Broken Record (2023), courtesy of Peres Projects.

abstracted architecture in panels of pastel-tinted resin, affixed with video monitors that display Shuang’s music videos. They’re set to cover versions of the American rock songs she used to learn English in her youth, translated into Li’s native Chinese.

McDavid pointed to the show as exemplary of the museum, the wider Aspen art scene, and its patrons, who she believes embrace creative risk and diversity like few other places in the world. “I think a lot of that has to do with the sophistication of the collectors in Aspen,” she says. “People take risks, and I see a much more interesting mix here.”

Li’s

Richard Carter

Carter has seen Aspen bloom, boom, bust, and transform many times over in the five decades he’s been making art here. The painter, instigator, former Herbert Bayer studio assistant, and Aspen Art Museum co-founder urges people to look downvalley to find locally based artists striking sparks and making creative fires the way they once did in Aspen. “The bright spot for me is downvalley,” explains Carter, whose home and studio are both now in Basalt.

He touts the work of artists from his midvalley cohort, including the painter and sculptor Tania Dibbs, collage and mixed-media artist Teresa Booth Brown, and multidisciplinary artist Kris Cox, noting that artists from Aspen’s outer boroughs of Basalt and Carbondale are more likely to be represented by galleries in Denver, Dallas, and New York than they are by Aspen galleries, where international blue-chip art and higher commercial rents have squeezed out regional artists. (Collectors can still discover them at nonprofit galleries such as the R2 Gallery in Carbondale and The Art Base in Basalt, where Carter is a board member.)

“There used to be a time when, if you were a decent artist, you could be represented in a gallery in Aspen, because there was that kind of rent structure,” says Carter, who published a book in summer 2024 that features his recent series of “Bunker” paintings. “But that has all completely disappeared.”

88

Artist

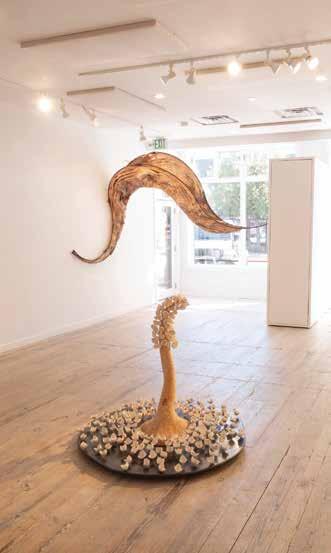

Above, Carbondale artist Andrew Roberts-Gray’s Tide Machine. On opposite page, Basalt artist Teresa Booth Brown’s Frequency (2020) and an installation view of Reina Katzenberger’s interactive exhibition, “Art in Process,” at The Art Base.

Above, Carbondale artist Andrew Roberts-Gray’s Tide Machine. On opposite page, Basalt artist Teresa Booth Brown’s Frequency (2020) and an installation view of Reina Katzenberger’s interactive exhibition, “Art in Process,” at The Art Base.

Taiwan-born chef David Wang respects—and reinvents—the Japanese art of ramen.

When the massive stoneware bowl hits the table, I catch a whiff of the faraway sea. One perfectly plump scallop, seared and glistening, bobs atop a tangle of fresh ramen noodles in a pool of pale golden broth. Nestled on the surface is a slim wedge of chrysanthemum tea-braised endive with charred edges; a few leaves of razor-edged mizuna and fluffy, diamond-cut green onion; and a soft-cooked egg, halved to reveal a dandelion-yellow yolk. Most curious of all, though, is the dollop of straw-colored froth that covers slices of sous-vide chicken breast in a tidy blanket.

“It’s miso-corn espuma,” says chef David Wang, using the Spanish term for “foam.” “You’ll notice the ajitama (ramen egg) this time is a lot whiter because I used a white shoyu marinade to balance the aesthetics of the bowl. On top, a floater of scallop oil mixed with yuzu.”

Soul

in the

Bowl Text by Amanda Rae

Images by Tanya Martineau and Trevor Triano

90

Chef David Wang’s invite-only ramen dinners are designed to change public perception of the dish.

We’re dining at Aspen’s most intimate venue, home to the latest iteration of Wang’s clandestine “ramen club”: his studio apartment. The neat space is decorated accordingly—a neon sign depicts chopsticks hovering over a bowl of noodles; a framed certificate from Tokyo’s renowned Rajuku ramen school recalls the two-week master class Wang completed in 2023. A wooden table is set for four and Japanese hip-hop fills the room.

The masterpiece before me, which follows a formula of layering broth, aroma oil, seasoning, noodles, and toppings that dates to ramen’s origins in 1910 Japan, represents nearly three days’ worth of work. The broth is a “quadruple threat,” Wang shares. “A 12-hour, minimalistic chicken broth, mizudorikei—which translates to ‘water chicken style’—is mixed with clam broth cooked 25 minutes, scallop broth cooked for 30, and dashi cooked for 15, all separately because they have different glutamate indexes that peak at different times. If you throw everything in a pot and cook it, you lose all the nuances.”

Thomas Shires, a six-year Aspen transplant by way of Dallas, Texas, lifts his face from the bowl. “The corn thing is brilliant,” he quips between slurps.

“You see butter, corn, scallops all the time,” says Wang, who emigrated from Taiwan with his parents before age 2 and grew up in Orange

County, California. “Culinary Institute [of America] was largely French training. I’ve been studying Latin cuisine, Japanese, Korean, Chinese, Hong Kong, Taiwanese, practicing and experimenting. Now I’m at a point in my career that I can intentionally start blending them together with respect. I’m not mashing stuff together for the sake of it.”

When Wang began hosting communal dinners on his building’s rooftop in 2017, calling the word-of-mouth series Umami Underground, the meals focused on tonkotsu , or pork bone broth—popular with Americans, he notes, because the liquid is rich and creamy with emulsified fat, thanks to aggressive boiling. Wang’s mission from the beginning: to change perceptions around the dish in a “fun, exciting, almost secretive” setting.

“Ramen is not just this quick, easy, cheap throwaway item,” he explains. “There’s a spectrum of styles, flavors, schools of thought. I want people to be able to tell the difference between from-scratch ramen and the sandbagging, cheap stuff that a lot of places sling for a quick buck.”

Once demand for the rooftop parties exceeded physical limitations, Wang launched several ramen pop-ups and kitchen takeovers at local restaurants. Meat & Cheese owner Wendy Mitchell invited Wang back to his old stomping grounds in 2018. (He was executive chef

92

at Meat & Cheese from its opening in 2014 until 2017.) The 200-seat event sold out almost immediately. However, Wang was “head down in the kitchen the whole time,” evaporating any chance at meaningful, educational dialogue. “People showed up, but they weren’t necessarily into it enough to finish their food,” he says. “That’s the culture of this town: Sometimes it’s not about the food or quality. It’s going out to be seen.”

In 2021, once group gatherings resumed post-pandemic, Wang held small tastings in his apartment, typically drawing about 40 people over two nights. He began experimenting with taste memories and new techniques, then he traveled to Tokyo for the intensive ramen course at the Rajuku school, his fourth trip to Japan. Founded by 40-year veteran chef Takeshi Koitani, the institution has turned out apprentices that have gone on to earn high accolades worldwide. Wang’s longtime inspiration, Orange County-based Ramen Shack founder and Ramen Burger creator Keizo Shimamoto, developed his own cooking style under Koitani’s mentorship.

“One of the first operation days, I got assigned to the soup station—literally, to heat up soup and pour it into a bowl,” Wang says. “Within five minutes, I got corrected on the way you hold the ladle, the way you pour it into the bowl. [Koitani] would splash in a few drops of tare (seasoning) to adjust for balance because I was a

couple cc’s over in soup. That level of accuracy was very humbling.”

Wang also learned to make noodles. Recently he purchased a countertop rolling machine from China and has been testing flours with different protein content and grind size from artisan mill Dry Storage in Boulder. “His passion grew and translated to the bowl [after Japan],” says Shires, a diehard fan who got a taste of Wang’s evolving sensibilities at Hao House, the chef’s winter 2018 pop-up at Jimmy’s Bodega. “Did you have the last bowl, the tagine? It was so brazen and against the grain, but so flavorful and overwhelmingly him.”

Wang’s Moroccan-inspired chicken tagine ramen was built off a bag of spices a friend brought back from the African continent. Seeing similarities with Japanese curry (originally adapted from India for Japanese palates), he dove into flavor profiles, swapping preserved lemon for yuzu; apricots for ume plum. His Latin riff on mapo tofu incorporated recado negro paste from Bosq, chorizo instead of ground pork, and hominy.

“My ramen will never be recognized as ‘real’ ramen and that’s OK. It’s American ramen, like American Chinese—our version of it,” Wang says, noting that Japanese ramen itself began as a fusion food, using imported Chinese noodles. “Much like how I feel about my own culture. When it comes to identity, here in America, I’m not

96

American enough. I’m not Taiwanese enough because I wasn’t raised there. I feel no obligation to follow rules.”

In March 2024, Wang appeared as a contestant on Food Network’s Chopped , and his maverick approach is quickly conveyed to viewers. “Some people call my cooking rebellious,” Wang remarks in his introduction, endearing himself to judges who praise his unconventional use of ingredients, “amazing” flavors, and “clever” cooking technique. “We’re all really thrilled watching you cook in the wok,” declares award-winning chef-restaurateur Danny Bowien.

Now Wang, who owns and operates King & Cook catering, is hungry for the next step: a restaurant in Aspen. “After seven years, I have a very clear concept of what I want to do with my own space,” he says. Currently, his ramen tastings are invite-only and donation-based, though he does reserve a few seats for hopeful guests who inquire on social media.

Bellies full, we clink cups of coldsteeped wheat tea—another product of Wang’s Japan odyssey—and promise to stay in touch. “Oftentimes you’re sitting with someone you wouldn’t cross paths with otherwise, but for a love of ramen,” Wang muses. “It’s not a fancy setting. Anyone can share food and find some commonality. The dining table is the most important table in the house.”

100

“I

want it to be rebellious, geeky, genuine, and intentional. There are so many ramen spots in this country that serve a soup stock concentrate, just add water.”

—Chef David Wang, on the art of ramen

—Chef David Wang, on the art of ramen

Seed to Skin Tuscany founder Jeanette Thottrup is on a mission to redefine luxury skincare.

Seed to Skin Tuscany founder Jeanette Thottrup is on a mission to redefine luxury skincare.

Esteemed by luxury spas around the world, a holistic skincare brand cultivates slow, conscious beauty at its stateof-the-art lab on a Tuscan farm.

On their honeymoon in 2001, former fashion designer Jeanette Thottrup and her husband, Claus, purchased 13 acres of the Borgo Santo Pietro estate near Siena, Italy. Originally from Denmark, the couple saw their slice of the Tuscan countryside—a former pilgrim healing village beset by rolling hills and meandering rivers—as the place where they would build a life and start a family. In the midst of an extensive restoration to transform the property’s 13th-century villa into a boutique luxury guesthouse, the couple was blindsided when doctors told Jeanette she likely would not be able to have children.

Immediately, Jeanette improved her diet. She consulted an herbalist and an acupuncturist, planted an herb garden, and researched Chinese medicine. After two years of embracing holistic paths to wellness, Jeanette became pregnant with her son, Vincent. “It was such a testimony to the power of nature and herbs, and what can happen if you actually live by them,” Jeanette says. “From then on, that became my journey and what Borgo is about today—eating natural food and living a natural life.”

As her fascination for botanical healing grew, Jeanette dreamed of ways she could harness the curative properties of plants for health and beauty. She studied with Neal’s Yard Remedies in London, a pioneer in the world of organic skincare, and was inspired by the brand’s integrity— something she felt was lacking in the beauty industry. “The concept of ‘natural’ was exploding, but there was a lot of mystery surrounding the big names in beauty and where their ingredients came from,” she says. “I wanted to create better products that would make a difference and be totally transparent about how we were doing it.”

Images

of

to

A Nourishing Nature In Collaboration with The Little Nell

Text by Lindsey Kesel

courtesy

Seed

Skin Tuscany

With its many microclimates and mineral-rich soil, Borgo Santo Pietro offered an energetic ecosystem where a skincare line could spring to life. As the Thottrups invested in more land and expanded the six-guestroom hotel they opened in 2008, they established a regenerative farm, laboratory, and processing plant, allowing ingredients to be grown, tested, and formulated on site. Anna Buonocore, a cosmetologist and cosmetic science professor at the University of Siena in Tuscany, became a founding partner and recruited a team of scientists. In their quest to create science-driven skin solutions powered by nature, Jeanette and company hoped to set a new standard for skincare. “We wanted to prove that this was the only way to do it, ” she says.

Following five years of preparation, Seed to Skin Tuscany launched in 2018 with an ethos of “slow, conscious beauty.” To that end, the evolution of a new product, or integration of a new ingredient, can take years to perfect. In the estate’s experimental herb garden, Jeanette nurtures 50 or more varieties at a time. While Mediterranean herbs such as rosemary and lavender

grow naturally, introducing foreign plants into the clay-like soil—such as ashwagandha and St. John’s Wort, currently under observation—involves a great deal of trial and error. “If we’re going to dedicate 20 acres to a brandnew herb, we have to put in the time to make sure it grows well,” she notes.

In the lab, the Seed to Skin scientists engage in biotech practices such as fermenting and infusing to pack upwards of 60 components into a skincare formulation, with the goal of high potency. The researchers apply green molecular science—which the company describes as a method of layering molecules for optimal absorption into the skin—to ensure every ingredient makes an impact.

Skin to Seed caters almost exclusively to luxury spa clients that are willing to work closely with the brand and undergo thorough training on its products. “We’ve spent so much time and energy on our line, in the end we want to deliver it to people who understand the science,” Jeanette explains. “We’re only as good as the therapists using our products, so education is really important.”

104

Guests of Borgo Santo Pietro are invited to tour the grounds and observe raw ingredients at their source—in the wild and in the garden. Visitors can also watch products being made through a massive glass wall in the lab. “It’s like when you see people cook food—you want to eat it,” Jeanette says. “When you see skincare being made by real people with a real passion for what they do, you want to try it.”

With 350 acres of health-centric enterprises, including Claus’s recent biodynamic winemaking operation, Jeanette hopes their sprawling Tuscan paradise is a testament to the virtues of sustainability and living off the land. “Borgo Santo Pietro is a place where you live a natural life when you’re here. You can speak to the farmers, eat what’s grown here, feed your mind and body,” she says. “This is the real luxury—everything you can grow out of well-nourished soil is a luxury, because it will live in the world going forward.”

The Little Nell is the sole North American hotel to carry Seed to Skin Tuscany’s bath products in-room.

106

and other herbs are grown on site and transformed into state-of-the-art

products featured in The Spa at The

and other luxury spas worldwide.

Calendula

skincare

Little Nell

Calendula

skincare

Little Nell

An iconic fashion house transforms the spa and outdoor spaces at The Nell in time for the hotel’s 35th anniversary.

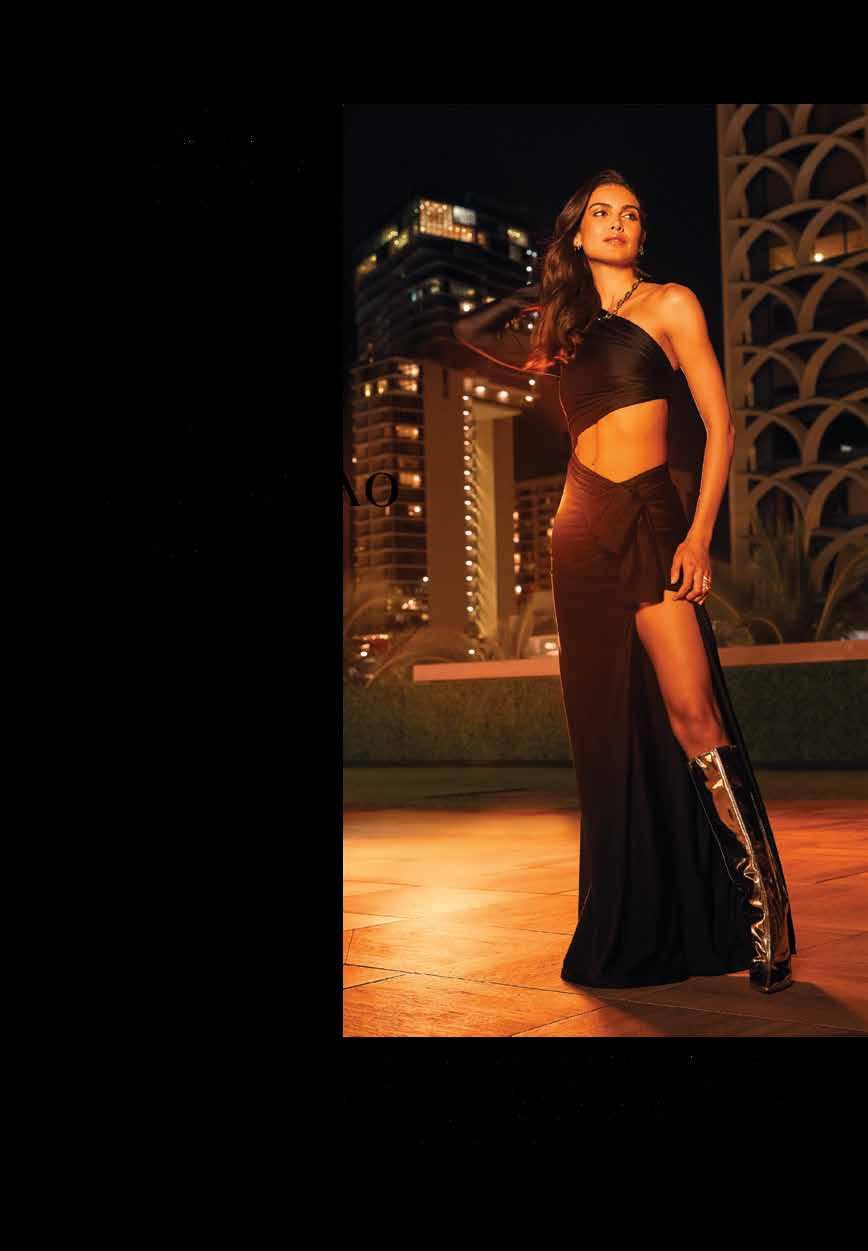

Aspen’s only five-star, five-diamond hotel welcomes a summer of Dioriviera, a pop-up and capsule collection conjuring the glamour of the French Riviera. Since the concept’s launch in 2018 in Mykonos, Greece, it has traveled in the form of ephemeral activations and popup stores in idyllic destinations around the world, from Cyprus to Bali to Beverly Hills, evolving in tandem with the house’s ever-expanding Dioriviera collection, a range of ready-to-wear clothing, swimwear, accessories, and beachwear reinvented each season by Maria Grazia Chiuri, Dior’s creative director of women’s haute couture, ready-to-wear, and accessories collections.

Dioriviera lands in Aspen in 2024 with a takeover of three treatment rooms at The Spa at The Little Nell, along with a re-envisioning of the hotel’s pool deck and hot tub cabana, inspired by the summer 2024 Dioriviera capsule collection, some of which is available throughout the season at the Dior Aspen boutique. A defining characteristic of the collection is Dior’s staple Toile de Jouy motif, which has been part of the house’s visual identity since its inception in Paris in 1946.

At the advice of his friend, the artist and fashion illustrator Christian Bérard, Christian Dior blanketed the brand’s headquarters at 30 Avenue Montaigne in the distinctive textile, and it went on to become a signature element in the Dior universe, evoking visions of travel and fantasy in keeping with the house’s opulent aesthetic. The monochrome print now adorns a variety of summery items in the Dioriviera collection and is brought to life at The Little Nell with Toile de Jouy Soleil, a celestial iteration of the Toile de Jouy pattern.

Dior’s early years of living alongside his mother’s windswept garden in the seaside town of Granville in Normandy sparked a lifelong passion for which he has famously been quoted: “Thankfully, there are flowers.” Inspired by the designer’s affinity for flowers and gardens, Dioriviera at The Little Nell includes an installation in the hotel’s floral wall and weekly garden tours in collaboration with its resident gardener.

Various food and beverage experiences are offered at a poolside cart, and an experiential activation awaits at Gondola Plaza all summer long. Meanwhile, the Dior Spa at The Little Nell features a curation of Dior retail products and a vibrant menu of Dior wellness services, including facial and body treatments highlighting its exclusive Les Solutions Professionnelles line and Dior Powered by Hydrafacial treatment, currently only available outside of the United States.

Discover Dioriviera

Image courtesy of Christian Dior Parfums

In Collaboration with The Little Nell 108

La Collection Privée Dioriviera Eau de Parfum.

La Collection Privée Dioriviera Eau de Parfum.

110

The ballooning days of summer.

Image by Tamara Susa

Connect

Up in the Air with Patrick Carter

A

hot air balloon pilot keeps his family legacy alive at the Snowmass Balloon Festival.

The Snowmass Balloon Festival has a special place in our hearts. This will be its 49th year. While I’ve not been to the festival every year, our balloon has, and our family has. There’s no way I can break that ritual.

One of my favorite flights was about two years ago. Six or seven of us pilots flew over Pikes Peak in Colorado Springs. We drove up to the other side by Woodland Park and passed by the divide, inflated, and then took off. Obviously, you don’t want to go right over the peak, at 14,000 feet. You want to get some air, so we flew right around 17,000 feet. It’s definitely the highest I had ever been. As a balloon, we’re not allowed to go over 18,000 feet without permits, mainly because we’re getting into a controlled airspace. We don’t show up on radar very well, being fabric.

As told to Hilary Stunda Images by Tamara Susa

112

112

After a chance encounter with the singer-songwriter, the Carter family named their hot air balloon after the John Denver song “Rocky Mountain High.”

Maneuvering has stayed pretty much the same since 1783, when the first Montgolfièr balloon launched in Paris. We can go up and we can go down. That’s about it. We have no control of the direction. When we take off, we follow the winds. There’s a lot of intuition involved.

During summer in the mountains, the cold air wants to drain down the mountainside and follow the river.

At 6 or 7 in the morning, all of this cold air is going downvalley toward Glenwood Springs. Then you’ll reach a spot where it heats up a little and neutralizes, and you will just get dead, calm air and stop. Then it starts heating up again and going upvalley. You have these little windows.

Snowmass is in that bowl. We call it the toilet bowl. There’s not a lot of cold air draining out of it. It stays there and swirls around. That’s why you’ll see all the balloons meander. You may be flying at 50 feet and

look over at somebody else at 50 feet going in the opposite direction. Then you’ll stop and go in a different direction. It’s very unpredictable.

At Snowmass there are launch directors. You want to make sure that if you’re upwind, you don’t take off first and drag your basket across another balloon because it could do serious damage. Our basket is very hard. It’s wicker, it’s steel. It’s got sharp edges. If you take that basket and slide it against the big envelope, which is like a big tent, you can tear it. That’s the danger. But when you’re flying, even in Snowmass, we’ll do a little bump and do clusters. You’ll see pictures of three or four balloons kissing each other. You can do that without any worry because you’re just giant pillows.

Back in February 1974, my father said, “That’s it, we’re buying a balloon and we’re going to make it a Colorado flag.” My father had the design with him on a flight traveling back from Los Angeles,

116

and John Denver was on the plane. My father taps him on the shoulder and says, “Excuse me, Mr. Denver, we’re getting this hot air balloon manufactured right now.” John Denver smiles and says “Far out, far out.” He had released his song “Rocky Mountain High” the year before. So the name of the balloon is actually Colorado Rocky Mountain High. We’ve shortened it a bit—on the radio talking to each other, it’s Colorado High.

Betty Pfister was a big force behind the Snowmass Balloon Festival. Randy Woods, from Unicorn Books in Aspen, was the other organizer. I remember his Unicorn Balloons. He really made the Snowmass Balloon Festival, especially in the early years, very similar to what you found in Europe. Which reminds me, my second favorite flight was at a balloon race in Switzerland, at Ch âteau-d’Oex. Randy made Snowmass into a world-class event, and it was always for a reason. The earlier festivals were fundraisers.

In the earlier years, ballooning was such a novelty. In the 1970s, wherever you landed the balloon, there would be hundreds of people coming out to gather around because they had never seen a hot air balloon before. It was like, Holy cow! I didn’t know how many people were in this little neighborhood There are a few places you can fly in small, little towns out in eastern Colorado and still get that reaction.

The 49th annual Snowmass Balloon Festival is scheduled for September 13 to September 15, 2024.

122

Layne Shea is excited to welcome her husband Mike, along with Montana Crady, in the formation of The Shea Team at Douglas Elliman. With a lifetime deeply rooted in the Aspen community and more than five decades of combined real estate and luxury sales & marketing experience, we are uniquely connected to all that Aspen has to offer.

Expertise in all aspects of the sales process and a thoughtful approach operating at the pinnacle of the market make The Shea Team your ideal guides to experience why life is simply better on mountain time.

© 2024 DOUGLAS ELLIMAN REAL ESTATE. EQUAL HOUSING OPPORTUNITY. 630 EAST HYMAN AVENUE, STE 101, ASPEN, CO 81611. 970.925.8810

The Shea Team Layne Shea Michael Shea Montana Crady 970.379.4781 sheateam@elliman.com

Andy

Legendary skier and angler Andy Mill and his son, Nicky, a Snowmass-based fly-fishing guide, discuss podcasting and enduring friendship.

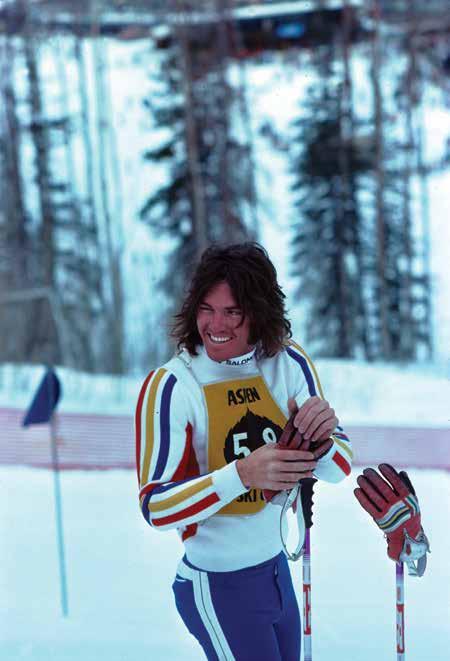

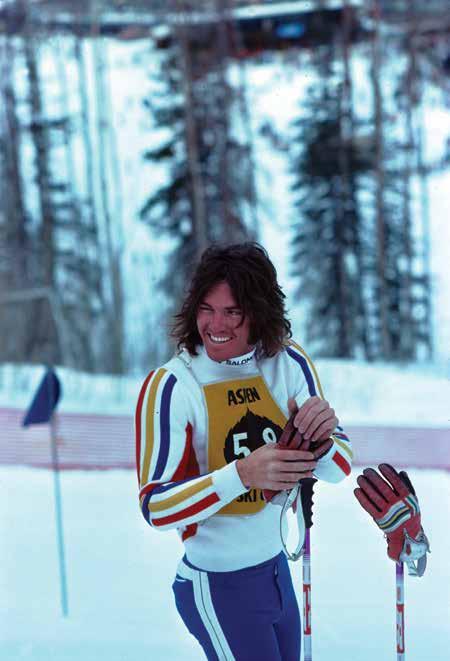

anglers, podcast hosts, and best friends, Nicky and Andy Mill enjoy a close father-son relationship.

Nicky Mill knows the precise moment when his relationship with his father, Aspen legend Andy Mill, changed. One constant throughout their relationship, however, was that it revolved around the outdoors: Splitting time as a kid between south Florida, where his parents lived, and Aspen, where his dad was raised, Nicky enjoyed access to world-class fisheries and one of the country’s premier mountain towns. You might think he was destined to follow his father’s ski tracks (Andy placed sixth in downhill at the 1976 Olympics), but it was on the water where he’d most take after Andy. After his ski racing career ended, Andy became a champion saltwater fisherman—a passion that hooked his son, too.

Andy recalls one day fishing the Florida Keys with Nicky when he was still young. Nicky threw a mediocre cast that left his line in a pile, but as he stripped it in, a massive tarpon sprang from the water and took his fly. “It was the moment that I think started it all,” Andy says.

Images

of Nicky

Mill

Inside the Mill House with Nicky and

Mill As told to Jay Bouchard

courtesy

and Andy

and Aspen Historical Society

124

Avid

It was also the moment that altered the course of their relationship. At some point soon after, the Mills agree, they became best friends. Today they’re also the co-creators of a hit fishing podcast, Mill House, and constant adventure partners— traveling the globe fishing, hunting, and interviewing legends of the outdoors.

Ahead, the father-son duo offer a glimpse into their adventures, how their podcast came to be, and the close friendship that’s brought them solace along the way.

Fishing is a huge part of your lives. Where did you discover that passion?

Nicky Mill: I have photos of myself with a little spin rod at Taylor Lake behind Aspen Mountain in the ’90s when I was, like, 2 years old. I didn’t totally gravitate to it until I was 13 and caught my first tarpon. It changed my whole perspective.

Andy: When you see a 100-pound fish come flying out of the water, it has the ability to change your life.

And you, Andy?

Andy: I started fishing in Aspen when I was 8 years old, in the ’60s. I saw this fly line go out across the grass at Wagner Park. The great Ernie Schwiebert was doing a clinic, and that’s the first time I had a fly rod in my hand. After that, I learned to tie flies, and once I saw a trout eat one of my flies, I was toast.

Andy, you were a world-class ski racer. When did your life shift back to fishing?

Andy: After my ski career, I was a broadcaster. I was doing Olympic ski coverage, but I was bored. The Outdoor Life Network offered me a fishing show, and we ended up producing episodes all over the world. I caught a blue marlin in St. Thomas on a fly rod. I fished the Arctic Circle with President George H. W. Bush. I got into tarpon tournaments and ended up winning more of those than anyone. My fishing career was more successful than my skiing career.

Let’s talk about your podcast, Mill House. How’d it begin?

Nicky: About five years ago, when outdoor podcasts were beginning to come about, I told my dad: “We should do a podcast.” He knew so many influential guides and anglers, and the stories they tell are unbelievable. At first, he said no.

Andy: Hell, I didn’t even know what a podcast was.

Nicky: After a year, he agreed to it.

Andy: I remembered what someone in the broadcasting world said to me a long time ago: “Who cares if Aunt Mary’s farm burns down if you don’t know who Aunt Mary is?” I started thinking: We need to find out who Aunt Mary is with all our guests. It couldn’t just be about how they caught a big fish—I wanted to know what hooked them and inspired them.

128

130

Nicky: Now, we release an episode every two weeks, 26 a year. I do a couple podcast trips to Florida each year, and we record in the summertime in Colorado. Once we decide on a guest, my dad does a lot of research. He calls the person’s friends and gets the background. We strive to find the underground people who have stories that have not been told. We try to find the people who don’t have social media, who don’t promote. He’s really the host; I’m the co-host. I do all the editing and promoting.

Who have been your favorite guests?

Nicky: We talked to a guide in the Keys named John O’Hearn. He has such a different approach to fishing compared to some of the guests we have on. He’s a salt-of-the-earth kind of guy who doesn’t care about material things. You’d be amazed by what he finds. There might be a worm hatch or bridge that everyone is fishing near, but you won’t see him there. I love that mentality.

Andy: We did an interview with Rick Ruoff. I asked him: “You were one of the first guides in the Florida Keys, and now there are hundreds. Your spots are all stolen. How do you deal with it?” He said initially he was going to quit, but then he realized the issue wasn’t other people, it was his perspective. It helped me think differently, too. I saw Aspen when there was not one rod on the river. Now, I won’t even fish Aspen because I feel bad for the fish. But I won’t get on other people because they’re having a great time. For them, these are the good old days.

Do you two still ski Aspen together?

Andy: Every year, I like to come in when the sun is high on the mountain and ski a few hours. I’ve been going left and going right down Ajax Mountain since the ’60s.

Are you still fast?

Nicky: He’s the fastest one on the mountain.

Does he beat you, Nicky?

Nicky: Oh, definitely.

All right, last question. What does your relationship with your dad look like these days?

Nicky: I still look up to him as my father and my greatest mentor, but he’s more of a best friend than a father. In the Keys, we launch our boat together and fish 17-hour days, from sunup to sundown. We hunt together. We’ve been through so much. I know more about my dad than anyone.

How would you describe it, Andy?

Andy: I can’t imagine anyone having a better relationship than what Nicky and I have. We live fully and we live hard. You can only survive certain things with your best friend. We’re trying to pull things off at a high level. You have to be backed up by someone who can really fulfill their end of the bargain. I’m fortunate that that guy is my son.

134

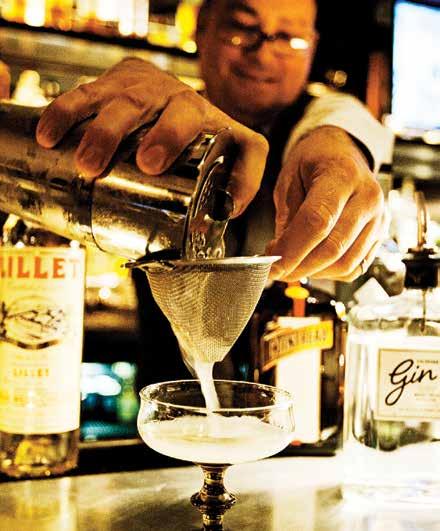

The executives behind three cornerstones of

Henning Rahm General Manager

The Little Nell

Henning Rahm General Manager

The Little Nell

Small But Mighty Text by Amiee White Beazley

Images by Trevor Triano

Small But Mighty Text by Amiee White Beazley

Images by Trevor Triano

Resistance Climbing (2023) follows Andrew Bisharat to the Israeli-occupied West Bank to climb newly established limestone walls with the locals.

Resistance Climbing (2023) follows Andrew Bisharat to the Israeli-occupied West Bank to climb newly established limestone walls with the locals.

Urwah Askar is a regular at Palestine’s Ein Fara climbing area. The Palestine Climbing Association was recognized as a member of the International Federation of Sport Climbing in 2024.

Urwah Askar is a regular at Palestine’s Ein Fara climbing area. The Palestine Climbing Association was recognized as a member of the International Federation of Sport Climbing in 2024.

Bisharat’s family is pictured outside their home in West Jerusalem. The home is now sequestered in a wealthy Israeli neighborhood formerly occupied by the late Prime Minister Golda Meier.

Bisharat’s family is pictured outside their home in West Jerusalem. The home is now sequestered in a wealthy Israeli neighborhood formerly occupied by the late Prime Minister Golda Meier.

The Storm Cellar partners with Forage Sisters, a field-to-table catering company, to host al fresco wine dinners on the vineyard.

The Storm Cellar partners with Forage Sisters, a field-to-table catering company, to host al fresco wine dinners on the vineyard.

The Storm Cellar’s alpine desert landscape is part of the reason it specializes in white and rosé wines.

The Storm Cellar’s alpine desert landscape is part of the reason it specializes in white and rosé wines.

Creative Cosmos

Text by Andrew Travers

Images by Sarah Kuhn, Olive & West Photography, Benjamin Rasmussen, and courtesy of the artists and galleries

Creative Cosmos

Text by Andrew Travers

Images by Sarah Kuhn, Olive & West Photography, Benjamin Rasmussen, and courtesy of the artists and galleries

Below, Axel Livingston’s Valley Dump (2021). On opposite page, Jeffrey Gibson’s Try A Little Tenderness (2023), courtesy of Sikkema Jenkins & Co.

Below, Axel Livingston’s Valley Dump (2021). On opposite page, Jeffrey Gibson’s Try A Little Tenderness (2023), courtesy of Sikkema Jenkins & Co.

Sterling McDavid

CEO and Founder of Sterling

Sterling McDavid

CEO and Founder of Sterling

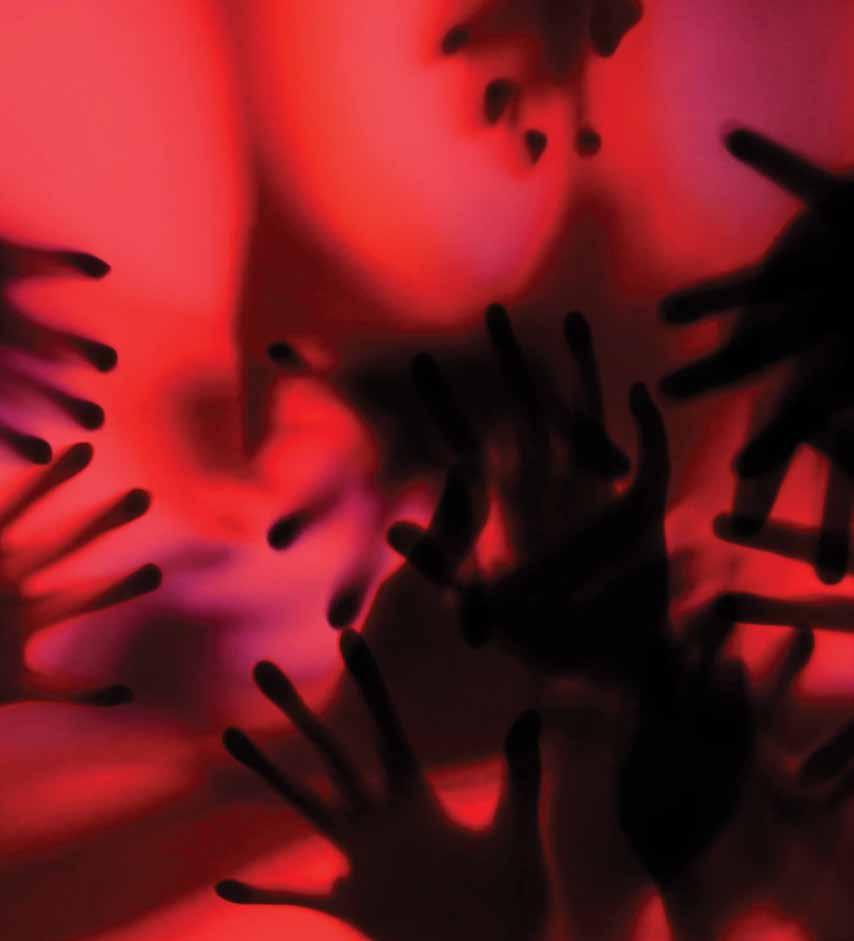

Above, Shuang Li’s Stand up fucking tall, don’t let them see your back (2022). On opposite page, The portrait of the Artist as a young man (2023) and Heartbeats Pound Softer (2022), courtesy of Peres Projects.

Above, Shuang Li’s Stand up fucking tall, don’t let them see your back (2022). On opposite page, The portrait of the Artist as a young man (2023) and Heartbeats Pound Softer (2022), courtesy of Peres Projects.

Above, Carbondale artist Andrew Roberts-Gray’s Tide Machine. On opposite page, Basalt artist Teresa Booth Brown’s Frequency (2020) and an installation view of Reina Katzenberger’s interactive exhibition, “Art in Process,” at The Art Base.

Above, Carbondale artist Andrew Roberts-Gray’s Tide Machine. On opposite page, Basalt artist Teresa Booth Brown’s Frequency (2020) and an installation view of Reina Katzenberger’s interactive exhibition, “Art in Process,” at The Art Base.

—Chef David Wang, on the art of ramen

—Chef David Wang, on the art of ramen

Seed to Skin Tuscany founder Jeanette Thottrup is on a mission to redefine luxury skincare.

Seed to Skin Tuscany founder Jeanette Thottrup is on a mission to redefine luxury skincare.

Calendula

skincare

Little Nell

Calendula

skincare

Little Nell

La Collection Privée Dioriviera Eau de Parfum.

La Collection Privée Dioriviera Eau de Parfum.

Patrick Davila, general manager of Hotel Jerome, pops a bottle in celebration of the inaugural Aspen Croquet Cup.

Patrick Davila, general manager of Hotel Jerome, pops a bottle in celebration of the inaugural Aspen Croquet Cup.