The People’s Painter

Classical paintings

by L. A. Ring

by L. A. Ring

A Swedish Lens on America

Photographs from Studio 54 and beyond

Leading the Charge: Nordic countries’ proactive response to the climate crisis

Relaxation Station: A Finnish sauna’s journey from Finn Hill to Market Street

Northern Lights Auktion

Hyatt Regency, Seattle | Saturday, May 11, 2019

Photo by Luke Stackpoole on Unsplash

A fundraiser for the Nordic Museum

Photo by Luke Stackpoole on Unsplash

A fundraiser for the Nordic Museum

CONTENTS 3 FROM THE CEO 4 LAURITS ANDERSEN RING: ON THE THRESHOLD (OF A NEW CENTURY) A special look at a renowned Danish painter 7 LET’S BE FRIENDS A friendly exchange with Denmark’s national gallery 10 EXHIBITIONS 2019 An overview of art 11 STUDIO 54 AND BEYOND The party isn’t over for cutting-edge photographer Hasse Persson 18 JACOB A. RIIS: THE IDEAL AMERICAN Social reform through a photographer’s lens 20 EYESOUND: AUGNHLJÓ Ð: Ø JENLYD A cross-country conversation without language barriers 22 BEHIND THE SCENES OF THE VIKING AGE Going beyond The Vikings Begin 27 CAPITAL CAMPAIGN DONORS Spotlight: Nordic Legacy Circle 30 BUILDING A NORDIC–LA BRIDGE An interview with an entrepreneurial rock star 32 COMBATING CLIMATE CHANGE IN THE NORDIC REGION Nordic countries clean up their act 35 BY THE FIRE Sami stories find a new audience 36 ILAPUT: INTERWOVEN: SAMMANV Ä VT: VEVD Blended cultures, interwoven heritages 37 CULTURAL RESOURCE CENTER A small space with big impact 39 STORYTIME, PAST AND PRESENT Storytelling looms large in the Nordic eye 40 IN FLUX Nordic artists respond to global immigration with personal work 43 GAINED IN TRANSLATION A Nordic author braids fairy tales, femininity, and the Finnish language 44 GLASS ART TAKES FLIGHT The Faroese artist with birds on the brain 46 LIVING LEGACY A sauna’s journey from Finn Hill to Market Street 50 A NORDIC WAY TO PLAY Your new summertime favorite 52 IN PRAISE OF THE ICELANDIC SHEEP The island’s dyed-in-the-wool heroes 56 FREYA’S ICELANDIC MULE A Nordic drink with a kick

Join us! Become a Member today.

nordicmuseum.org/membership

NORDIC KULTUR 2019

The Magazine of the Nordic Museum

EDITORIAL BOARD AND MAGAZINE STAFF

Devon Kelley Editor / Marketing Manager

Mark Murray External Relations

Eric Nelson Chief Executive Officer

Fred Poyner IV Collections Manager

Katie Prince Editor / Marketing Coordinator

Ani Rucki Design and Layout / Graphic Designer

Jonathan Sajda Program Manager

CONTRIBUTORS

Justin Allan-Spencer | Christine Clifton-Thornton | Brangien Davis

Sven Haakanson | Flemming Just | Devon Kelley | Michael King | Timothy Krumland

Peter Nørgaard Larsen | Fred Poyner IV | Neil Price | Barbara Sjoholm | Nancy Zinn

BOARD OF TRUSTEES

Trustees

Thomas W. Malone (President) | Hans Aarhus (Vice President) | Valinda Morse (Secretary)

Steven J. Barker (Treasurer) | Irma Goertzen (Immediate Past President)

Electa Johnson Anderson | Lars Anderson | Per Bakken | Brandon Benson | Anne-Lise Berger

Ray Brandstrom | Jay L. Bruns, III | Earl Ecklund | Arlene Sundquist Empie | Ann-Charlotte Gavel Adams

Mike Hlastala | Tapio Holma | Ken Jacobsen | Jane Klausen | Kurt Manchester | Kurt Ness

Aaron Overland | Rick Peterson | Maria Staaf | Birger Steen | Henrik Strabo | Heli Suokko Nina Svino Svasand | Lisa Toftemark | Tor Tollessen | Margaret Wright

Honorary Consuls

Kristiina Hiukka, Finland | Geir Jonsson, Iceland | Jon Marvin Jonsson, Iceland

Lars Jonsson, Sweden | Mark T. Schleck, Denmark | Matti Suokko, Finland

Honorary Trustees

Senator Reuven Carlyle | Leif Eie | Senator Mary Margaret Haugen

Sven Kalve | Council Member Jeanne Kohl-Welles | Senator Marko Liias

Bertil Lundh | Allan Osberg | Mayor Ray Stephanson | Representative Gael Tarleton

MUSEUM STAFF

Executive

Eric Nelson Chief Executive Officer

Sandra Nestorovic Chief of Staff

Kirstine Bendix Knudson Special Project Coordinator

Erik Pihl Community Engagement

Development

Jenny Iverson Development Manager

Anna Craddock Annual Giving Coordinator

Mollie Henry Development Coordinator

Caroline Parry Grants and Giving Coordinator

Marketing and Communications

Devon Kelley Marketing Manager

Mark Murray External Relations Team

Ani Rucki Graphic Designer

Sheila Stickel External Relations Team

Finance and Human Resources

Pamela Brooks Director of Finance & HR

Carolyn Carlstrom Bookkeeper

Drue Chatfield Human Resources Assistant

Timothy Krumland Volunteer and Staff Resource Coordinator

Curatorial

Nancy Engstrom Zinn, PhD Interim Director of Collections, Exhibitions, and Programs

Fred Poyner IV Collections Manager

Jonathan Sajda Program Manager

Alison Church Children’s Education Coordinator

Stina Cowan Public Programs Coordinator

Robin Kaufman Exhibitions Coordinator

Michael King, PhD Adult Education Coordinator

Kathi Ploeger Music Library Archivist

Kaia Wahmanholm Registrar

Operations

Adam L. Allan-Spencer Director of Operations and Facilities

Libby Anderson Museum Store Associate

Donna Antonucci Guest Services Associate

Augustino Gamboa Custodian/Facilities Assistant

Joni Hughes Visitor Services Coordinator

Kate Johnston Guest Services Associate

Jaimie McCausland Guest Services Associate

Evan Miller Facilities Coordinator

Lindsay Ravensong Guest Services Associate

NORDIC MUSEUM 2655 NW MARKET STREET, SEATTLE, WA 98107 | 2 06.789.5707 | N ORDICMUSEUM.ORG

Welcome to the seventh edition of Nordic Kultur, the magazine of the Nordic Museum. It feels wonderful to write this in our new museum—a space that has quickly gone from feeling new and unfamiliar to feeling like home

From our first-ever Nordic Innovation Conference to our first Julefest on Market Street, with every passing month we are learning more about our extraordinary new home and how it expands our capabilities. In the coming year, we will continue to stretch ourselves to deepen our connection to our community, and to develop our range of programmatic offerings.

One program I’m especially excited about is Interwoven, our oral history initiative that preserves and shares the stories of families with blended Nordic and Native American ancestry. Interwoven contributor Sven Haakanson’s article beautifully describes his mixed Alutiiq, Danish, and Norwegian heritage. You’ll also learn how our Cultural Resource Center is working to share our collections and oral histories with researchers and the public.

We highlight a few other museum gems too, like Tróndur Patursson’s extraordinary glass birds soaring in our Fjord Hall, and our Finnish sauna—more than 100 years old— that is (now) firmly grounded in the Museum’s East Garden. The journey of our sauna from Finn Hill to Market Street might not be as tough as a seabird’s Atlantic migration, but surprisingly, it still included airtime. You’ll have to read the article to find out about our

sauna’s second life and why it spent time aloft! Our 2019 visiting exhibitions underscore our commitment to present the widest possible range of ideas and artifacts, to spark dialogue, and to inspire new perspectives. You’ll find fascinating articles for each of these exhibitions in this issue. Neil Price, the lead researcher behind our current exhibit The Vikings Begin, has contributed an insider’s look at the exhibit and the new findings his team continues to unearth, both literally and figuratively. Our interim curator Nancy Zinn shines a spotlight on our summer exhibition Studio 54 and Beyond, including a description of the unique cultural perspective and photographic techniques used by Swedish photographer Hasse Persson. And SMK’s Chief Curator Peter Larson has included a celebration of Danish painter L. A. Ring, whose works will be exhibited here in September, 2019. Be sure to bookmark the exhibitions calendar so you can join us at exhibit openings throughout the year.

Finally, we have several articles discussing current Nordic events—from immigration, to environmental initiatives and climate change, and even video games. This issue is a blend of Nordic past and Nordic future, much like the museum you’ve helped us to call home this past year. As you read these articles, I invite you to reflect on the vast and varied Nordic story that has, through many winding roads, brought us here together.

Eric Nelson Executive Director/CEO

3

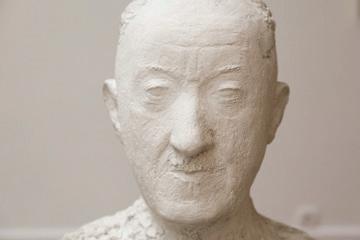

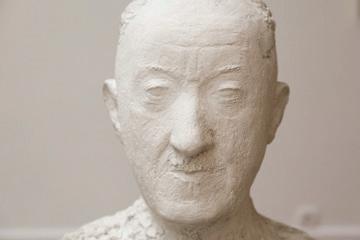

Laurits Andersen Ring

On the threshold (of a new century)

Peter Nørgaard Larsen Chief Curator and Senior Researcher, SMK, National Gallery of Denmark

The Formative Years

The Danish painter Laurits Andersen Ring (1854–1933) is among the most significant figures within Danish and Nordic art. He was born in the village of Ring in Southern Zealand. His childhood home was a modest farmhouse where his father scraped a living as a wheelwright and carpenter. As a child, Ring showed no remarkable artistic skill, so what prompted him to become an artist? His encounter with the magazines of the day—particularly the Nordisk Penning-Magazin—is mentioned as the first crucial push in an artistic direction. In it, advertisements from department stores were mixed with entertaining and educational articles about anything and everything, such as new inventions and great characters from history. The latter group included famous artists and colorful tales about how great painters worked their way up from poor backgrounds to become wealthy and celebrated artists. These tales fascinated the young man and helped present an artist’s life as a career option to a soul that had not found agriculture or carpentry very alluring.

In 1873, at nineteen years old, Ring decided to follow his artistic ambitions. He

L. A. R I N G

Fine Art

Waiting for the Train: Level Crossing by Roskilde Highway. 1914. Oil on canvas. 143 x 174 cm. The Prime Minister’s Office, long-term loan to SMK, Dep535

4

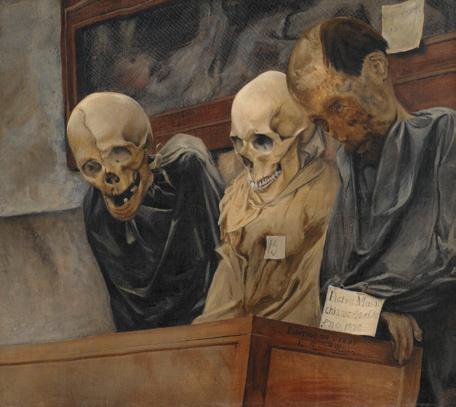

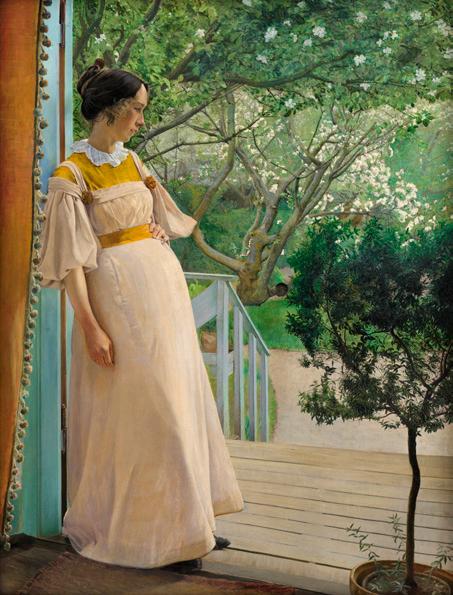

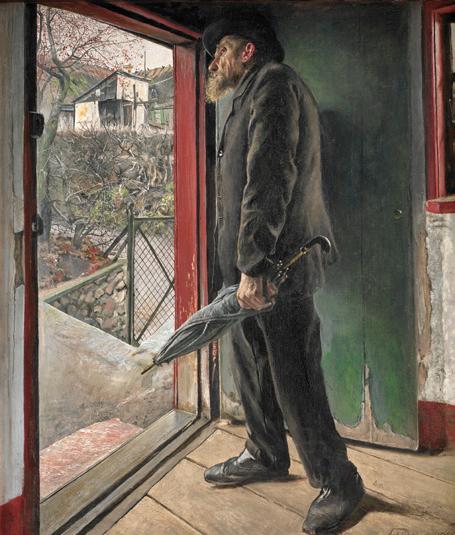

Images, clockwise from upper left

A Visit to a Cobbler’s Workshop. 1885. Oil on canvas. 94 x 120 cm. SMK, KMS7380

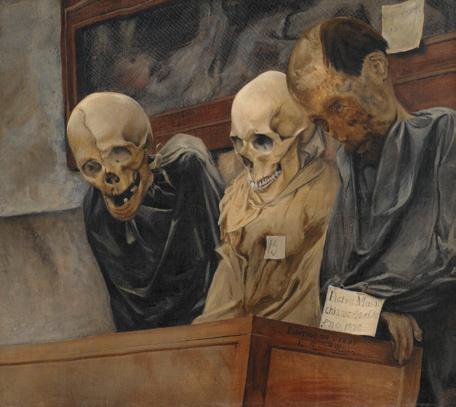

Three Skulls from the Capuchin Monastery at Palermo. 1894. Oil on panel. 55 x 62 cm. SMK, KMS3201

Landscape with Poplars: September Evening 1895. Oil on canvas. 91 x 52 cm. SMK, KMS8555

Harvest (a portrait of Ring’s brother, Ole Peter). 1885. Oil on canvas. 190 x 154 cm. The Prime Minister’s Office, long-term loan to SMK, Dep289

6 | NORDIC KULTUR

moved to Copenhagen, where he signed up for day and evening classes at the technical college to improve his basic artistic skills. His hard work paid off in January 1875 when he was finally admitted to the Royal Academy of Fine Arts as a student. But the classes disappointed him: the requirements for drawing technique caused him particular problems, and the rigid principles exacerbated his doubts about his own ability. As he continued to be dissatisfied with the fruits of his studies, he decided to leave the academy at the end of 1877.

Ring continued to make art, however, drawing on his rural upbringing as well as his current political views. During his childhood, Ring saw how his own family and large parts of the rural population faced very difficult living conditions. As an adult, he further empathized with the oppressed: during the 1880s he was politically active, participating in the struggle to improve the social and economic conditions of peasants and workers. From 1885 to 1894, the Danish prime minister J. B. S. Estrup ruled the country by means of interim provisory laws—even though the majority of the Folketing (the lower house of the Danish Parliament at the time) was against him. The political climate was rife with impending strikes and came as close to a revolution as Denmark had ever been. According to his friend Peter Hertz, Ring carried a loaded gun in his pocket, ready to take to the barricades and sacrifice himself in the struggle against injustice and for the freedom of the people.

Some paintings from these early years were considered overt political statements, as is obvious in two paintings from 1885: Harvest and A Visit to a Cobbler’s Workshop. In the latter, the attention is focused on the political agitator from the Social Democrats. He explains where his party stands in relation to the heated political climate of the day.

Into the Dark

The revolution never came, and Ring’s political ideals were not realized. He was disillusioned, and his private life fared no better. His childhood home was dissolved when his father died in 1883 and his brother

Ole Peter died in 1886 (just one year after Ring finished Harvest). Love was also long absent—at least requited love—for Ring fell in love with Johanne Wilde, the wife of his friend Alexander Wilde. He was a frequent guest at the Wilde household, discussed his work with Johanne, and corresponded with her frequently. The years that followed were the darkest of Ring’s entire life. The fascination with death—as a motif and as an unavoidable condition of life—which infused his entire life’s work became more intense during this period. As demonstrated in the painting Evening: The Old Woman and Death, from 1887, Ring’s preoccupation with death went from being a melancholy tenor to being a concrete, insistent motif that found its way to his landscapes and figure paintings alike.

In the autumn of 1893, Ring succeeded in raising money for a long tour of Italy. Only a few works from his journey exist, and it does not seem to have had a very tangible impact on Ring’s paintings. Perhaps the most remarkable work from his Italian journey is Three Skulls from the Capuchin Monastery at Palermo. In his childhood, the Penning-Magazin had fed him fascinating accounts of the catacombs of the Capuchin monastery, where prominent citizens had been buried for centuries. Ring created a rendition of Death triumphing over Life: rows of desiccated corpses and leering skulls firmly deny any concept of a life after death. Although frightening in its eerie, macabre fascination with death, the painting is not without a sense of humor in the very individualized rendition of each skeleton. Ring had a keen eye for their distinct expressions. Like players in a scene from the theatre of the absurd, they each play their own individual part.

If we look at Landscape with Poplars: September Evening, created after his return to Denmark, the work appears to have an Italian influence: there is a certain Italian feel in its lightning and subject matter (a prominent row of poplars). But the scene is actually of a churchyard in the city of Næstved, close to his native town. The painting was created in the days following the death of Ring’s mother.

LET’S BE FRIENDS

Friendship program supports Denmark’s Statens Museum for Kunst

Christine Clifton-Thornton

Denmark’s national gallery, Statens Museum for Kunst (SMK), in Copenhagen, contains an important part of the nation’s visual culture heritage. The museum houses multiple forms of expression that bear witness to ideas, thoughts, and experiences of human beings from Western culture, from the 1300s to today. SMK strives to bring art and art-based reflection to everyone in Denmark and to those interested in art throughout the world, with the hope of developing a living dialogue with society that inspires more people to experience the museum’s collections.

SMK is among the largest institutions in Denmark conducting research within the field of art history as well as art techniques and conservation, collaborating on research projects with universities in Denmark and worldwide. SMK has established a formal research center with the aim of attracting external scholars and postgraduate students, who can benefit from SMK’s research environment.

The American Friends of Statens Museum of Kunst (AFSMK) was founded in 2009 exclusively to support the charitable, educational, and scientific functions of SMK. The AFSMK promotes cultural and artistic exchanges between SMK and American institutions of art within the areas of transnational exhibitions, educational programs, and professional and scholarly exchanges. The organization helps fund the SMK’s work on building ever-stronger links between the heritage it safeguards and contemporary art and culture—work that takes the form of exhibitions, acquisitions of artworks, rehangs of the collections, and art conservation. To learn more about the program, visit www.afsmk.org.

LAURITS ANDERSEN RING | 7

A Spring Come Late

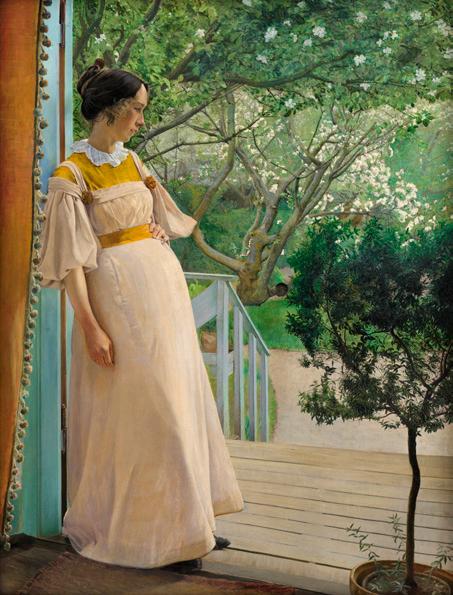

Shortly after returning to Denmark in 1895, Ring settled down in Næstved, where his friend and painter Rudolf Bertelsen offered him accommodation. Ring had several good friends in Næstved, most importantly the ceramicist Herman A. Kähler and his family, whom Ring had known for more than a decade. In April 1895, Kähler provided Ring with a studio in his factory, and Ring embarked on a large-scale painting entitled Spring, for which he used Kähler’s daughters Ebba and Sigrid as models. While the spring scene was growing on the canvas, Ring and Sigrid fell in love. They were married in 1896 and moved to nearby Karrebæksminde, where Ring set up his own home for the first time. A new, happy chapter of Ring’s life began, which is felt in his work in the form of new motifs characterized by an intimacy and a closeness not previously seen.

One of the most powerful examples of these new motifs is Ring’s portrait of Sigrid, At the French Windows: The Artist’s Wife Unquestionably a declaration of love, the painting features his wife posing at French windows and flanked by myrtle, the tree of love. The intimacy and closeness is also evident in The Artist’s Wife by Lamplight, painted the following year. Sigrid is surrounded by references to Ring’s private life. Portraits of his parents flank a study of Spring, the painting that brought Ring and Sigrid together, and on the table stands an eye-catching lamp made by his friend and father-in-law, Herman A. Kähler. For Ring, the interior scene with Sigrid in the center was a kind of refuge that offered him the calm and safety he had craved for years.

Landscapes of the Soul

Despite his newfound calm, the sense of meaning and happiness he found with Sigrid, and the three children that followed, Ring still experienced periods of melancholy. In the years to come, he would use landscape paintings as a vehicle to express his personal moods. Both A Road Near Vinderød and Thaw are typical of these landscapes of the soul. A new city provided new landscapes: the Ring family moved to

Frederiksværk in the autumn of 1898 and spent the next four years in the beautiful area, just a short distance from Lake Arresø and Roskilde Fjord. Not surprisingly, Ring preferred to paint his landscapes in autumn and winter, when he could use his favorite colors: whitish gray and yellowish-brown.

As he put it in a letter to Johanne Wilde in 1890: “Everywhere there is a wealth of subject matter wherever I look but then of course it is the most marvelous weather just right for me everything gray in gray with a few yellows and browns it is splendid.”

The landscapes may be realistic, but verisimilitude was not an objective in itself. Ring’s sense for oblique angles and peculiar cropping turns his landscapes into seismographic images of existence, painted on the threshold of the modern world.

The Later Years

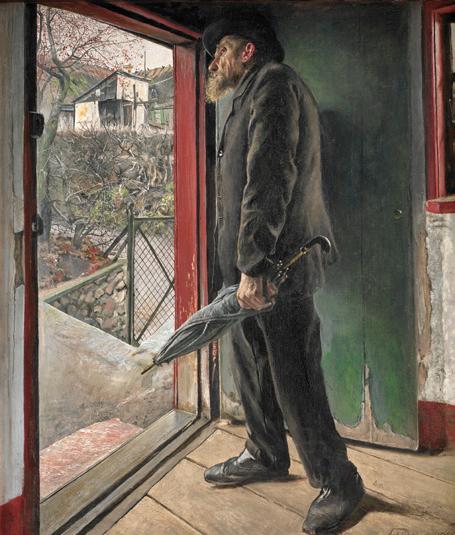

In a panoramic view of Ring’s paintings, two themes hold a central position: travel and waiting. Travel is addressed in the many landscapes where roads mark a “here” and “there.” They literally and symbolically point to the opportunity of going somewhere new, moving from one stage to another. The theme of waiting appears in a succession of works that show people pausing, often while occupying a position on the threshold between inside or outside. A typical and late example of the latter is Has it Stopped Raining?, which Ring painted in Roskilde in 1922. The painting shows an old man waiting, impatiently, for the rain to stop.

Ring was finally earning a regular and considerable income and purchased a plot of land at Sankt Jørgensbjerg in Roskilde. Just before moving to Roskilde, Ring finished one of his major works, the impressive Waiting for the Train: Level Crossing by Roskilde Highway. Here, modern life is no longer something observed at a distance as it merely passes by: it is a basic condition of life, for better or worse. But the man is not depicted as a sentimentalized relic of bygone times. With his bicycle and mode of dress, he is as much a part of modern life as Ring himself was. Ring embraced the new inventions and conveniences of the era with appreciation. In Roskilde he was much

talked about; he was one of the first to install a complicated heating system that was partly his own design. Thus, Waiting for the Train should not be regarded as a lament on how times had changed; rather, it should be viewed as a dispassionate description of the new conditions of life.

In 1923, when Ring turned 70, Sigrid died of lung cancer at the age of 49. He then stopped painting altogether for almost three years, remaining in his house with his son Ole, who had not yet left home. Several exhibitions of his work were put on in his later years, mainly in Denmark and Scandinavia. Some of his paintings were part of a Danish exhibition in Brooklyn in 1927, and the following year his work was on display in Paris.

In summer 1933, during the preparations for a solo exhibition in Copenhagen, he suffered a stroke and died in his home on Sunday, September 10, at age 79. The exhibition held that autumn became a memorial.

In spite of the distance in time, L. A. Ring’s wrestling with human existence— the nomadic restlessness, the revolutionary dreams of youth, love, deep depressions, and death, and the clear-sightedness and wisdom of old age—is still relevant to us. His life and oeuvre relate to everybody, and his paintings contain something universally human. |

8 | NORDIC KULTUR

L. A. Ring: On the Edge of the World will be at the Nordic Museum September 14, 2019–January 19, 2020.

Thaw. 1901. Oil on canvas. 40 x 61 cm. SMK, KMS7709

The Artist’s Wife by Lamplight. 1898. Oil on canvas. 68 x 87 cm. SMK, KMS3959

Has it Stopped Raining? 1922. Oil on canvas. 64.5 x 55.5 cm. SMK, KMS3636

At the French Windows: The Artist’s Wife 1897. Oil on canvas. 191 x 144 cm. SMK, KMS3716

Thaw. 1901. Oil on canvas. 40 x 61 cm. SMK, KMS7709

The Artist’s Wife by Lamplight. 1898. Oil on canvas. 68 x 87 cm. SMK, KMS3959

Has it Stopped Raining? 1922. Oil on canvas. 64.5 x 55.5 cm. SMK, KMS3636

At the French Windows: The Artist’s Wife 1897. Oil on canvas. 191 x 144 cm. SMK, KMS3716

The Vikings Begin

October 20, 2018–April 14, 2019

Based on the latest research conducted on both historic and recent Viking-era artifacts by Uppsala University in Sweden, The Vikings Begin tells the story of the Vikings of early Scandinavia (Sweden, Denmark, and Norway), an intensely maritime society with a very close and important relationship to the sea. Uppsala University’s museum, Gustavianum, has produced this exhibition of original artifacts, reconstructions, and archaeological discoveries from early Viking Age society using cutting-edge research done by Uppsala professor Neil Price and his team.

EyeSound

November 30, 2018–April 14, 2019

A visual conversation, EyeSound is a correspondence in images and words between Danish visual artists Iben West and Else Ploug Isaksen and four Icelandic authors. Playful and thought-provoking, the photographs do not illustrate the words, and the words do not explain the photographs. Instead, both art forms seek to build a conversation, working together or against one another to inspire viewer contemplation and consideration.

Bamse!

April 20–August 18, 2019

Meet the strongest bear in the world— Bamse! The creation of children’s comic artist Rune Andréasson, Sweden’s most popular bear debuted in 1966 as both a television cartoon and newspaper comic strip, and is still running today. This exhibition, produced by the Nordic Museum, introduces the world of Bamse to an American audience, highlighting the cast of colorful friends and strong moral themes that have always defined the cartoon’s story lines.

Eyesound

(Augnhljóð / Øjenlyd)

Photos Iben West

Else Ploug Isaksen

Words

Kristín Ómarsdóttir

Hallgrímur Helgason

Einar Már Guðmundsson

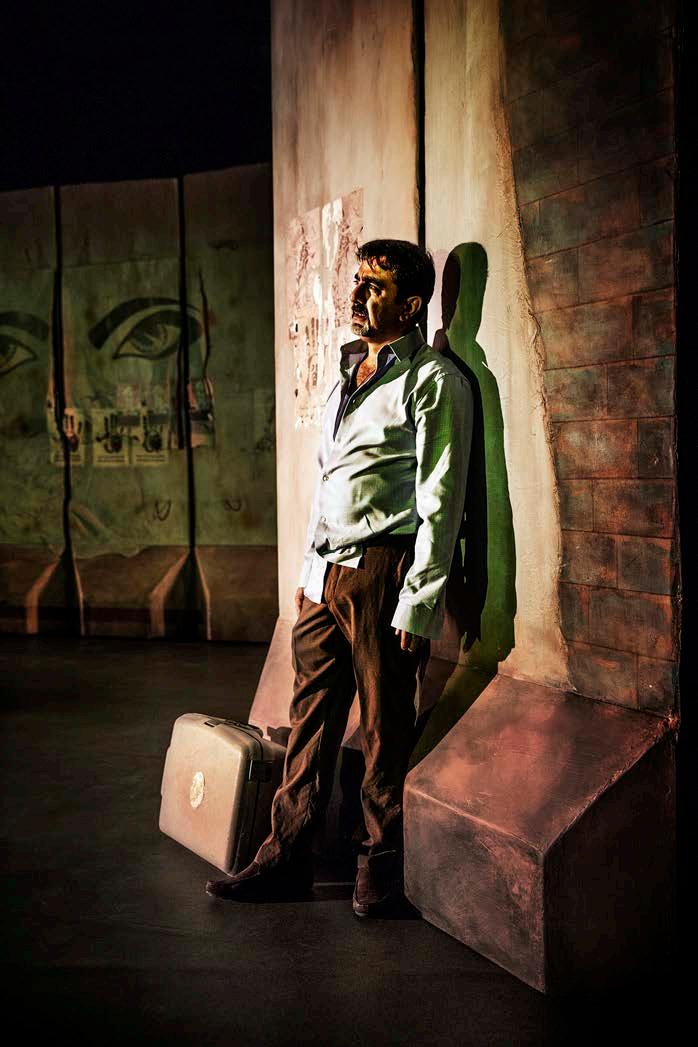

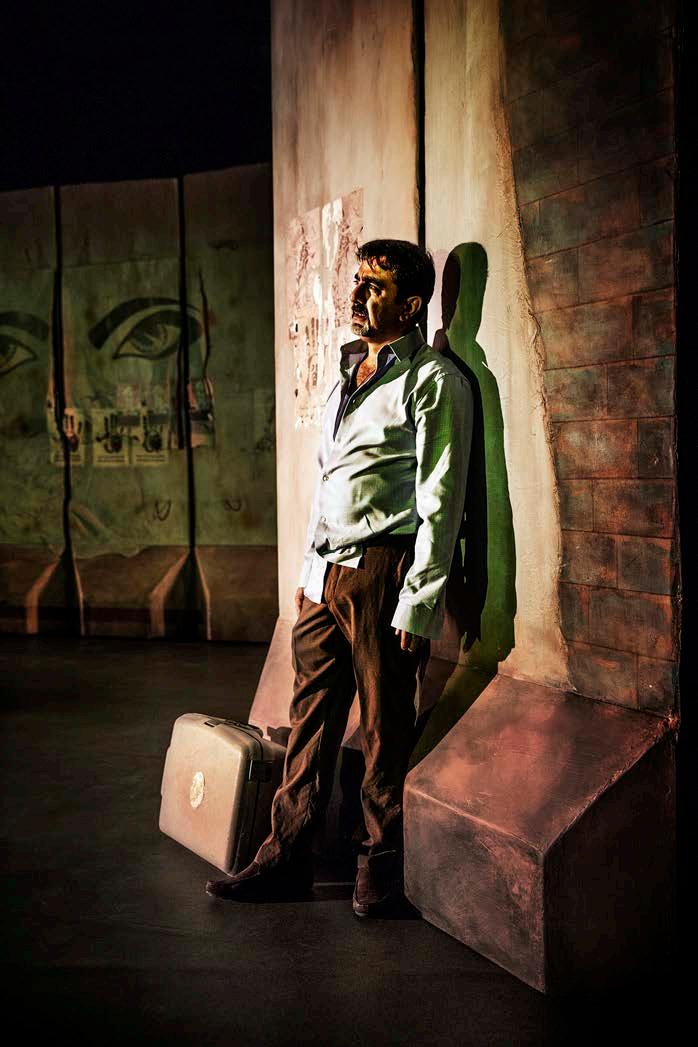

Studio 54 and Beyond

The Photography of Hasse Persson

May 11–August 25, 2019

False Friends

Two words from different languages, which resemble each other, but nonetheless mean something different, are known as false friends. There are many of them, and the closer they are to us, the harder hitting they become. That’s how it is, I guess, with both words and people. Those we are most familiar with are suddenly not quite, how we thought at all. Everyone knows that the Swedish are odd. Odd when they say lunch but mean breakfast. So how can one rely on anything anymore? Narrow-minded footsteps set in motion the journey to Auschwitz. Stop behaving so strangely. Be like us. Learn to speak politely. But, when the ground shifts under you, stout boots are a necessity. If you wear large shoes, then it’s here the joke unfolds, a space where meaning cheerfully collapses, shifts, changes direction like a billiard ball ricocheting off the cushion, and we laugh.

Pictures can also be false friends. Their resemblance to something else is not the same as identity. We recognise this when looking in the mirror and it shows someone else. She makes faces, sticks out her tongue and puts the toothbrush in her ear so one cannot see the sounds for the fits of giggles. Who is making these sounds? Remember to brush your books before you go to bed. Put your teeth in the right place when you’ve read them. Better one foot in the hand than a weathercock in the fog. Don’t sweep anything under the carpet, but let it flow like milk and honey, it’ll all come out one way or another, sooner or later. Don’t become accustomed to fringe benefits; they’re simply blowing in the wind. The soapbox roars when you roll down the blinds. Something bulges out and resembles something else. With your hand on your table: is this what you really mean?

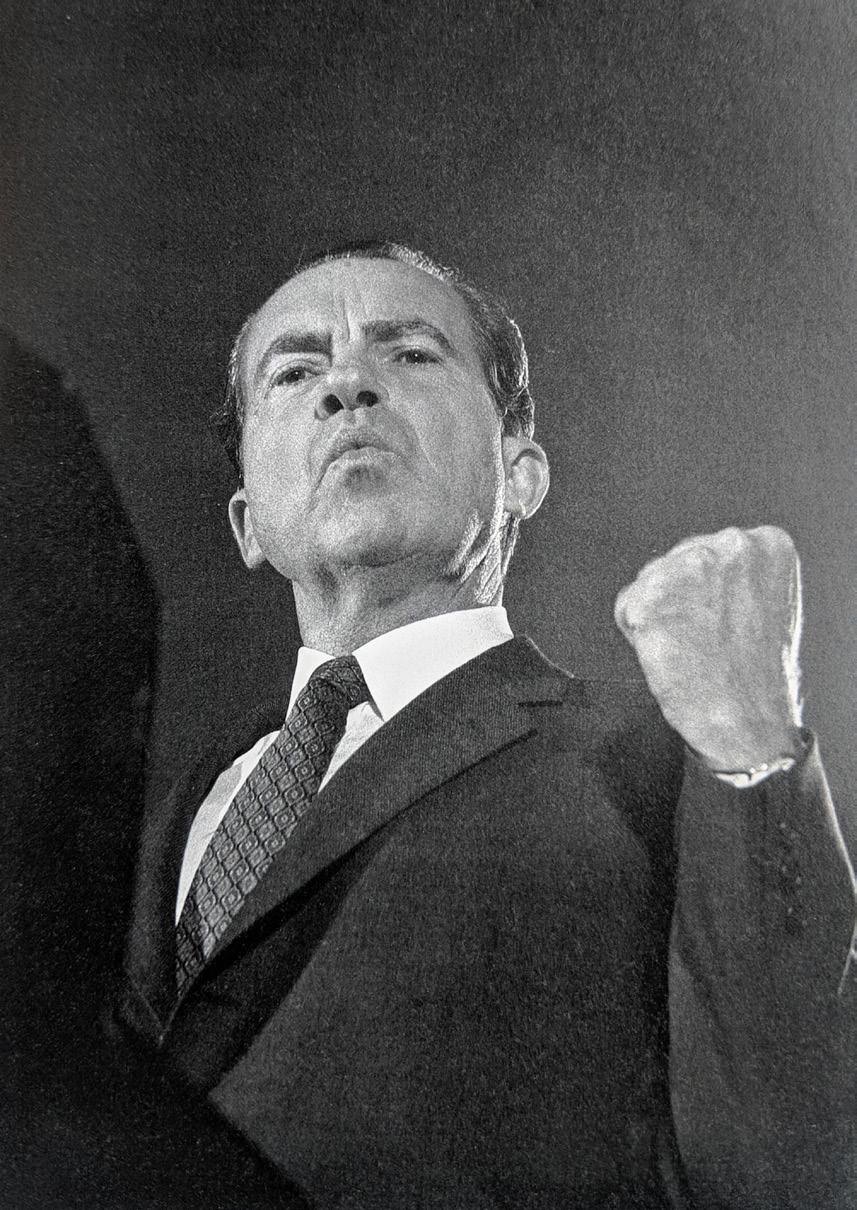

Experience one of the twentieth century’s most iconic nightclubs—Studio 54— through the eyes of acclaimed Swedish photographer Hasse Persson. Studio 54 and Beyond showcases Persson’s cutting-edge photographic techniques and unfettered access, providing an intimate and provocative first-hand look at the vibrant parties and eccentric personalities that made the New York disco an international legend. A decorated photojournalist, Persson’s photos of politics and popular culture in the US between 1967–1990 will also be on display.

L. A. Ring: On the Edge of the World

September 14, 2019–January 19, 2020

Laurits Andersen Ring, considered a principal artist of the late nineteenth–early twentieth century era, helped establish both the Symbolism and Social Realism artistic movements in Denmark. Ring always stayed true to his humble beginnings, depicting agrarian landscapes and the simple moments of rural village life as dominant themes of his work. L. A. Ring: On the Edge of the World was produced by Statens Museum for Kunst, The National Gallery of Denmark, and brings together over forty works by the master painter.

Oleana

October 5, 2019–January 5, 2020

Founded in 1992 by Signe Aarhus, Norwegian textile company Oleana has built a dedicated international fan base inspired by their award-winning designs. This exhibition will open in support of the museum’s 2019 Nordic Knitting Conference in October, where Aarhus delivers the keynote address.

10

Sigurbjörg Þrastardóttir

11

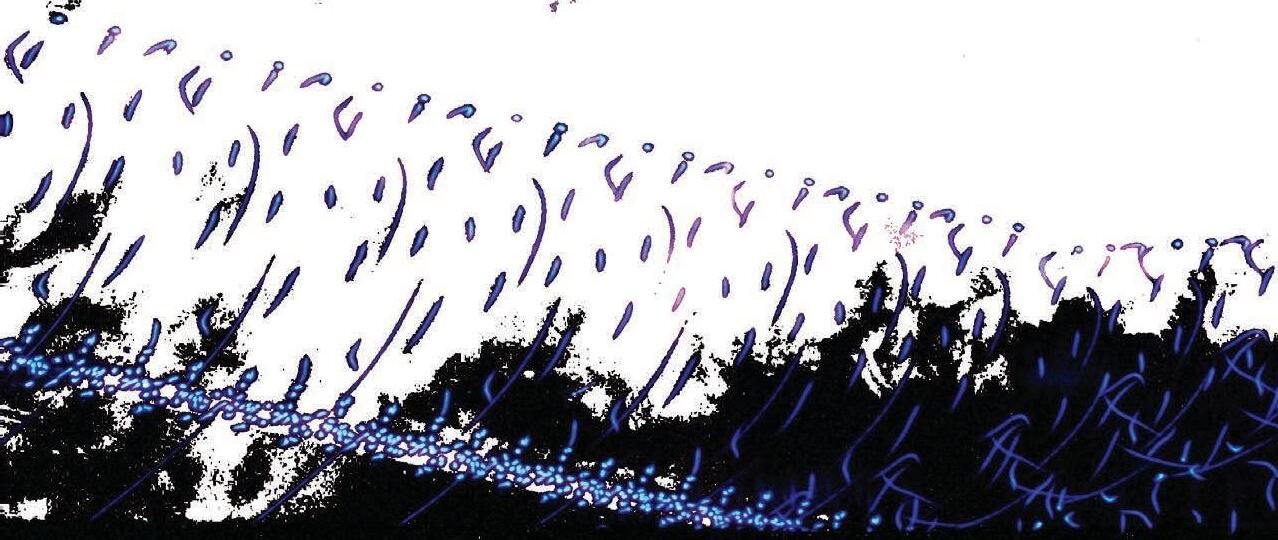

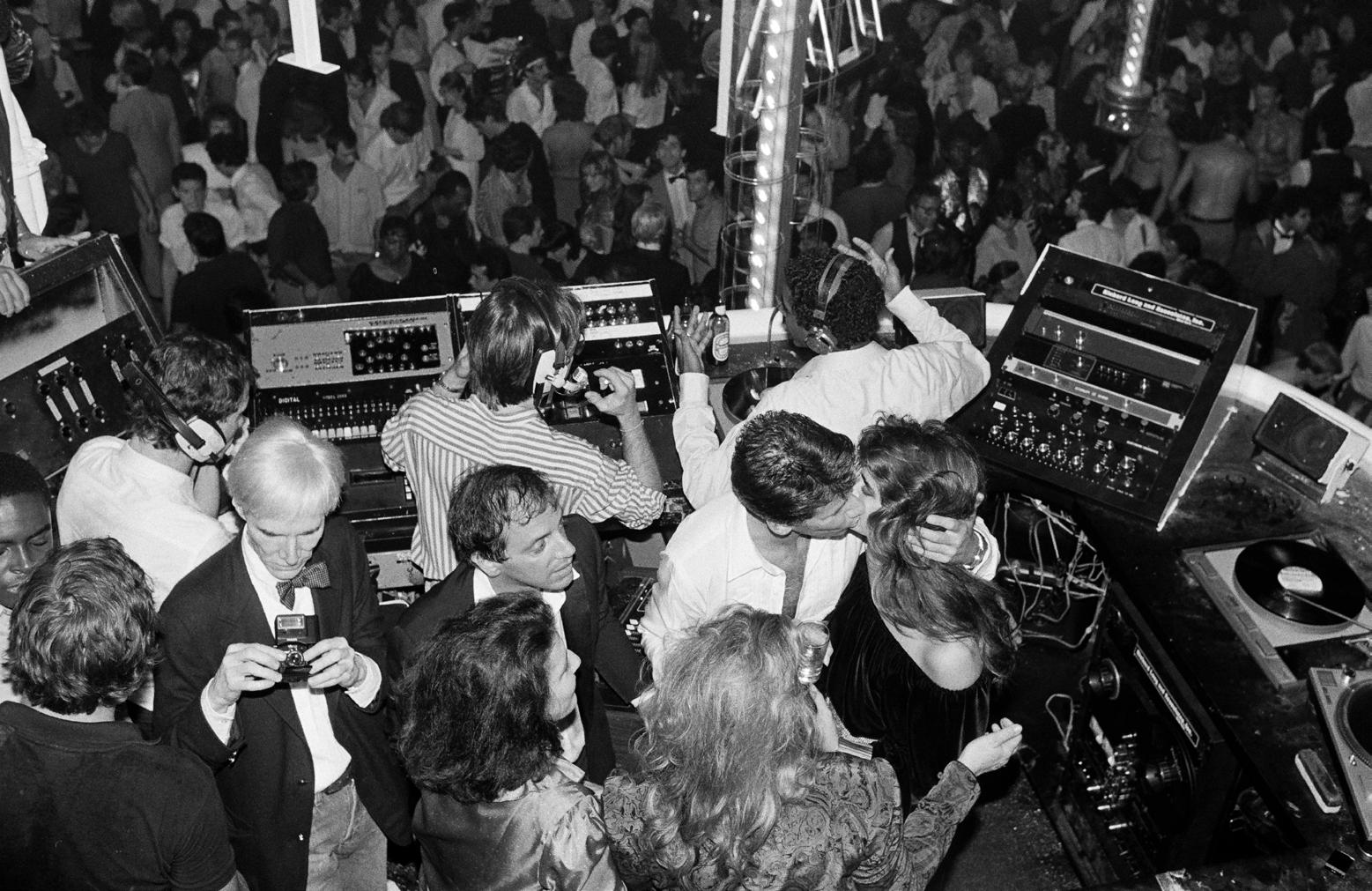

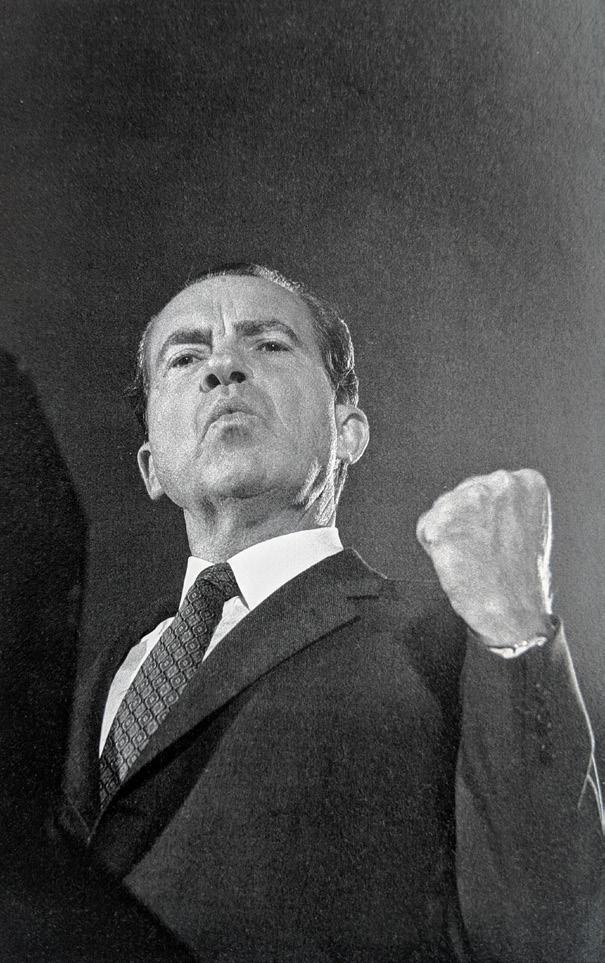

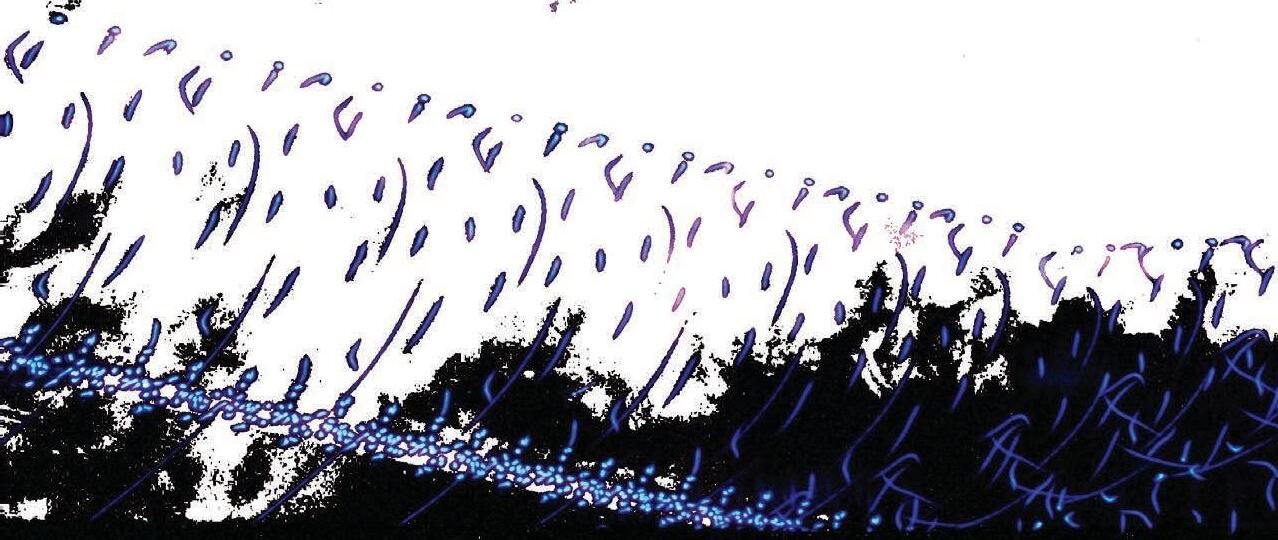

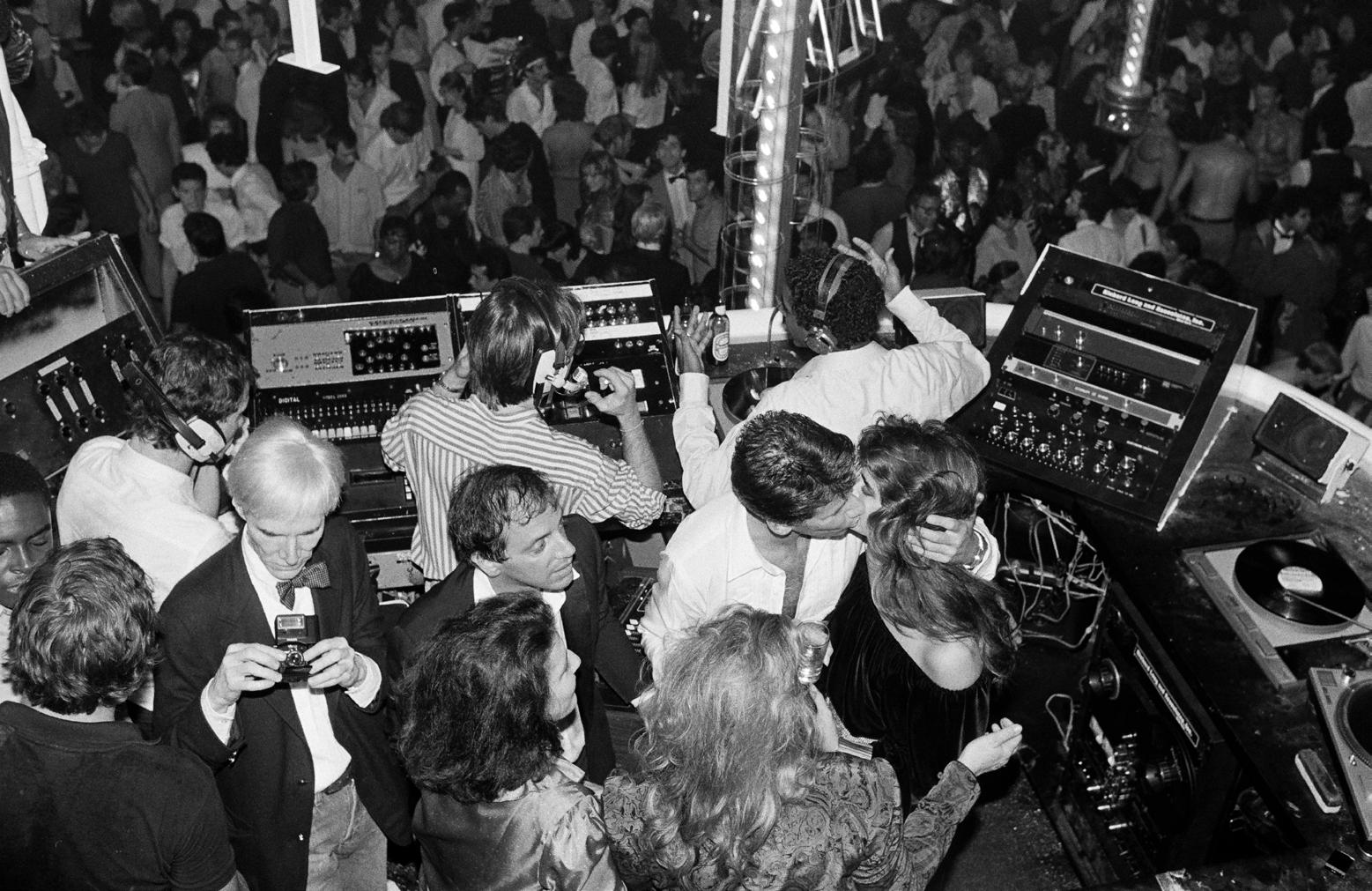

The Photography of Hasse Persson

Nancy Zinn, PhD

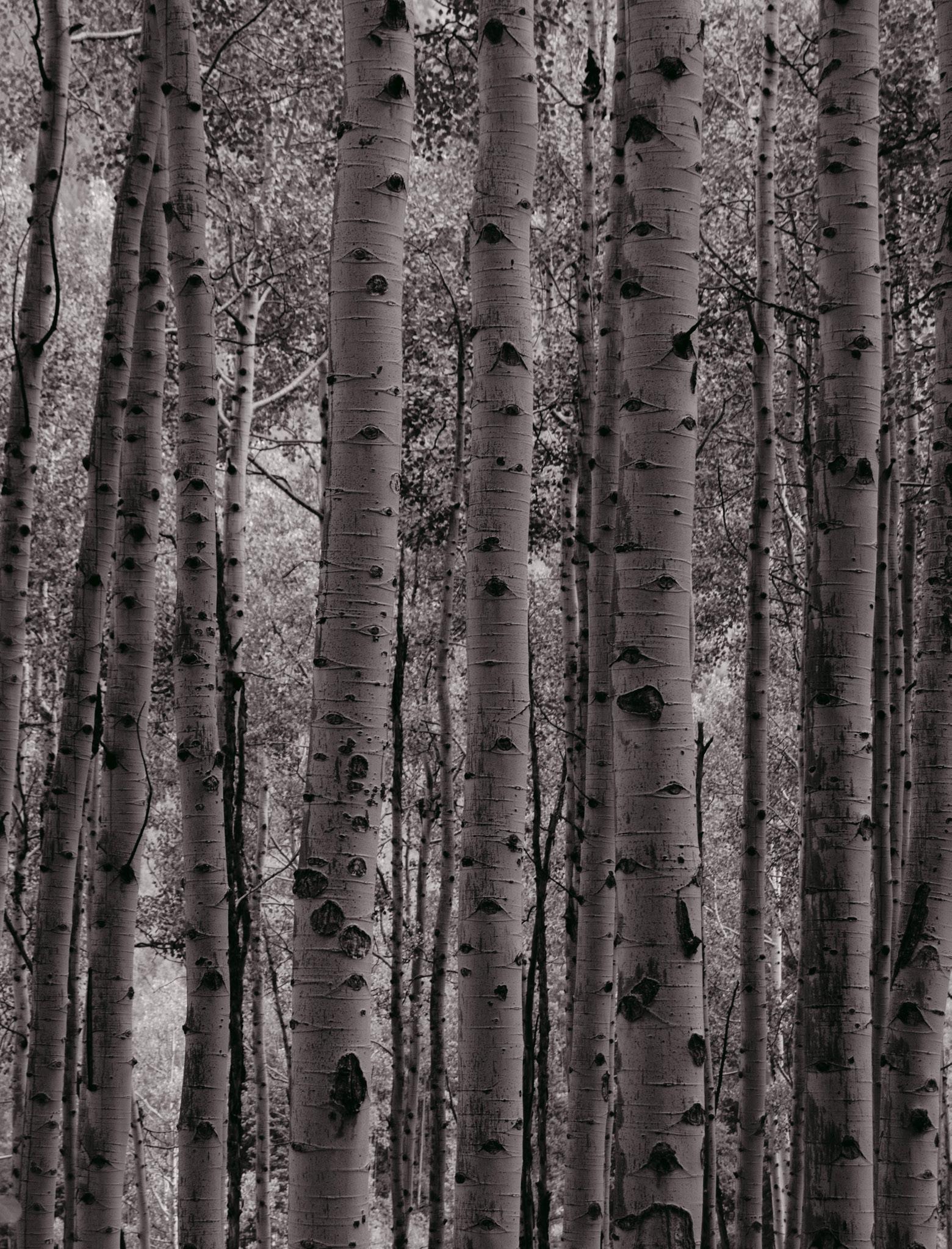

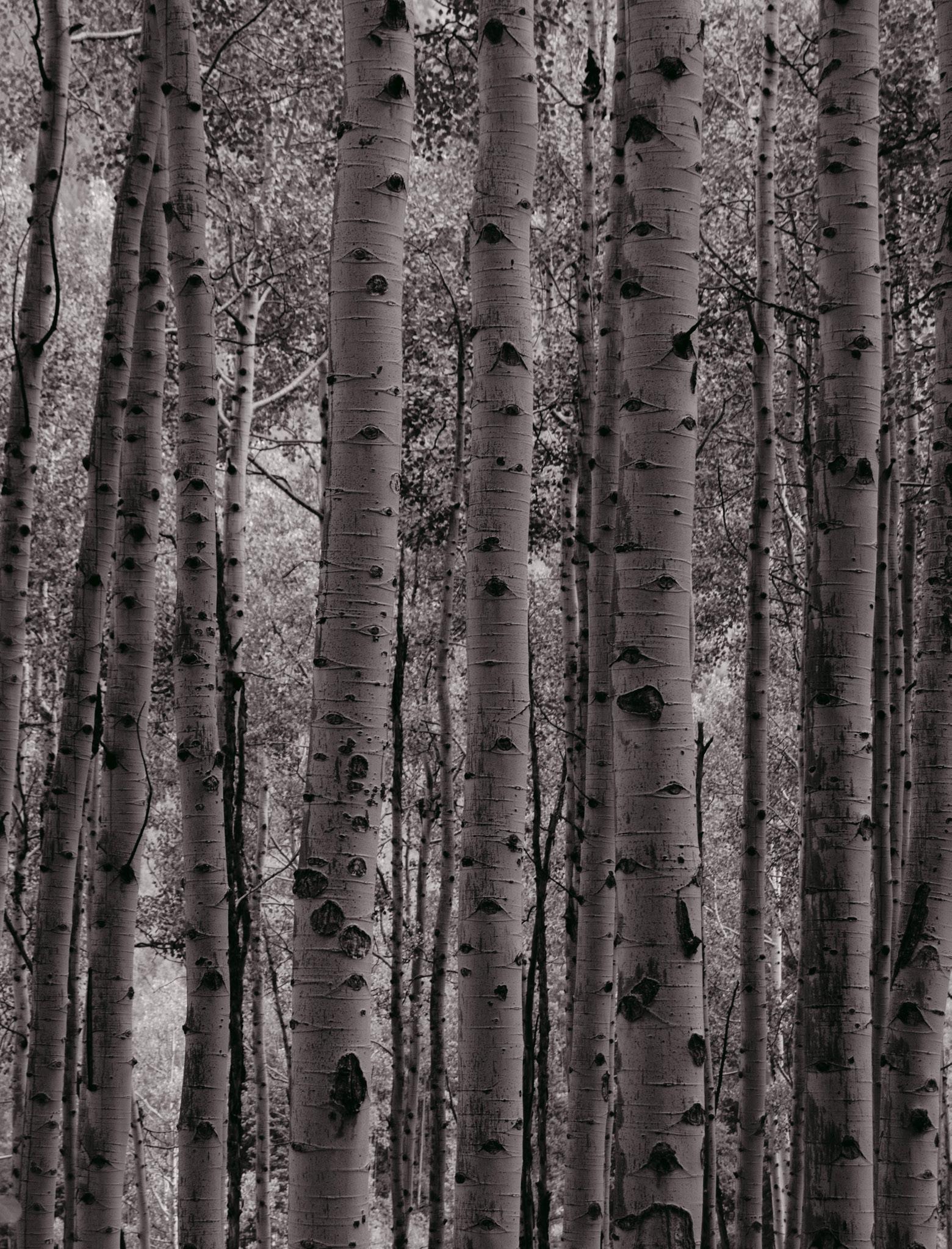

A moment in time captured by Persson’s signature technique: using the flash as a strobe to freeze a frame while keeping the shutter open.

Contemporary Art

The Photography of Hasse Persson

A man

Hasse

Studio 54. The name itself evokes images of artists, actors, politicians, supermodels, celebrities, and the cultural elite at play inside the world’s most famous nightclub. At the peak of the Disco era in the late 1970s, Studio 54 became the party destination in New York. On any given night, one could find regular patrons like Andy Warhol, Woody Allen, Sylvester Stallone, Elizabeth Taylor, Salvador Dalí, Grace Jones, Freddie Mercury, Truman Capote, Cher, Calvin Klein, Michael Jackson, and Brooke Shields enjoying the club scene.

The Studio 54 years capture a unique moment in time—situated between widespread use of the pill and the dawn of the AIDS epidemic—when sexual freedom, recreational drug use, and feminism were on the rise. Decadence and debauchery were the menu of the day, where the dance floor became a free zone for hedonistic personal expression of every kind. Gaining entry past the most famous velvet ropes in America was often a challenge for non-celebrities. Club owners Steve Rubell and Ian Schrager insisted that patrons be handpicked and that the crowd be intentionally diverse, giving it the feeling of a private party every night. Unlike society at large, Studio 54 was a place where members of the gay community were openly accepted. A live horse even joined revelers on the dance floor one evening, ridden to the club by supermodel Bianca Jagger.

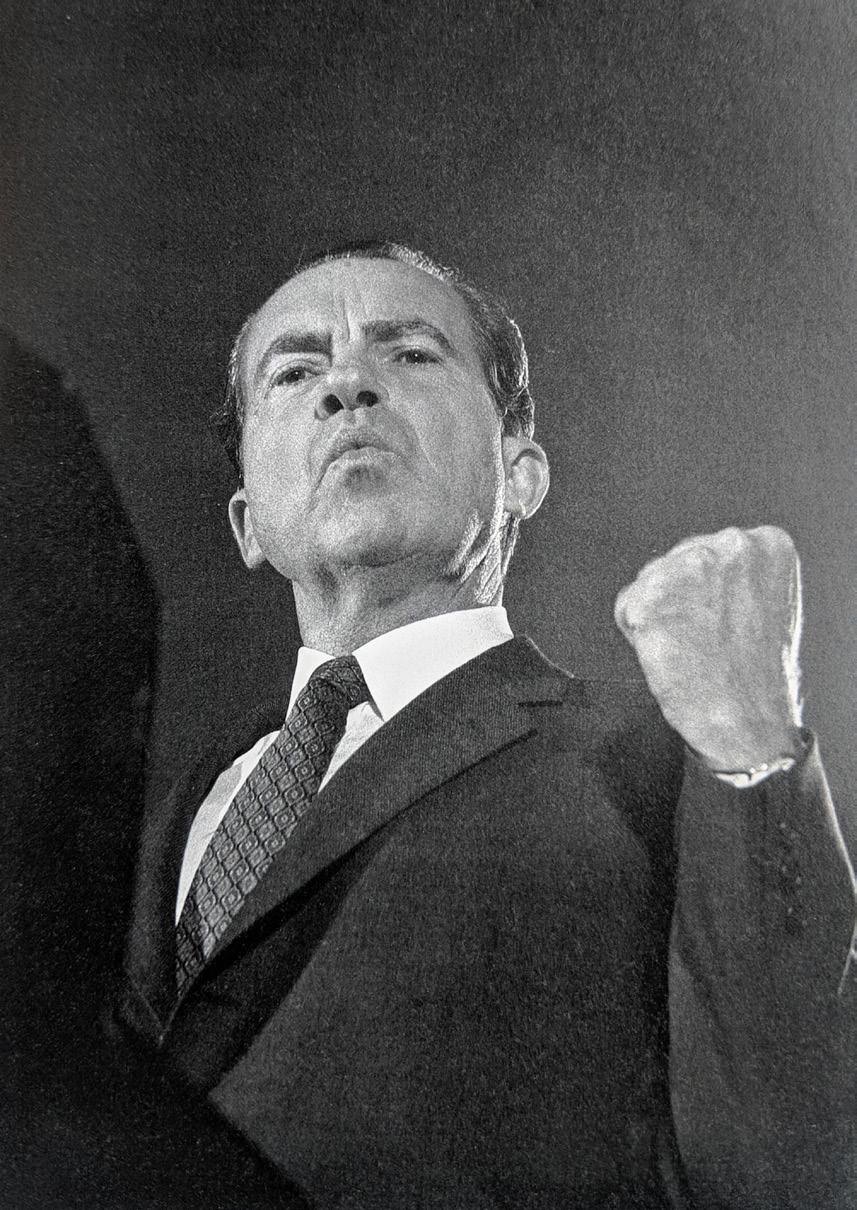

The exhibition Studio 54 and Beyond captures this brief moment in time through the candid, experimental, and highly personal lens of acclaimed Swedish photographer Hasse Persson, one of the world’s most notable photojouralists who documented contemporary life, race relations, politics,

STUDIO 54 AND BEYOND | 1 3

Images, clockwise from upper left

aims his gun while Persson aims his camera. This shot offers a rare glimpse of the photographer himself.

Persson at the exhibition, Studio 54 Forever, at House of Sweden.

Club owner Steve Rubell once said, “The key to a good party is filling a room with guests more interesting than you.”

Writer Truman Capote visited Studio 54 often. Here he’s seen with D. D. Ryan, the era’s most feared fashion editor, and editor Bob Colacello.

The costumed dancers here are caught by Persson’s flash.

Photo by Patrick G. Ryan

14 | NORDIC KULTUR

the war in Vietnam, and popular culture in the United States from 1968–1990. Persson spent more than 100 nights at Studio 54 as the only photographer allowed access after press hours by club co-owner Steve Rubell. By keeping his camera shutter open for as long as thirty seconds and using the flash like a strobe light, Persson was able to capture the energy, spontaneity, and fleeting imagery of the Studio 54 experience in a way that few others could. “I worked with luck,” Persson noted in a recent interview. “It was a human

STUDIO 54 AND BEYOND | 1 5

Images, clockwise from upper left

The club crowd was hand-picked each night to ensure a diverse mix of celebrities and regulars.

President Richard Nixon, photographed in his first year in office.

A group of Apache Crown Dancers pose in Gallup, New Mexico, in 1974.

A woman accessorizes at the 1972 Democratic National Convention in Miami, Florida.

This photo of the DJ’s “pulpit” from 1979 shows Andy Warhol, Calvin Klein, and Brooke Shields with Studio 54 owner Steve Rubell.

happening a fantastic mix and, in a way, elegant.”

But for all its fame, few people realize that the original Studio 54 was open for only some 1,000 days, from 1977 to 1980, before co-owners Rubell and Schrager, arrested for skimming $2.5 million in receipts and tax evasion, were forced to close the doors.

Persson made his museum debut in 1974 at the Moderna Museet in Stockholm. Since then, exhibitions of his work have brought him international attention. Persson has served as artistic director of the Hasselblad Center in Gothenburg, director of the Borås Konstmuseum, and artistic director of the Strandverket Konstall in Marstrand. Hasse Persson will be our guest for the opening of Studio 54 and Beyond in May.

The exhibition Studio 54 Forever was presented at the House of Sweden in Washington, DC. Additional photographs have been generously provided for the Nordic Museum exhibition by the artist himself. |

Studio 54 and Beyond will be at the Nordic Museum May 11, 2019–August 25, 2019.

16 | NORDIC KULTUR

Images, clockwise from upper left

A bronco bucks his rider during a 1974 rodeo in Gallup, New Mexico.

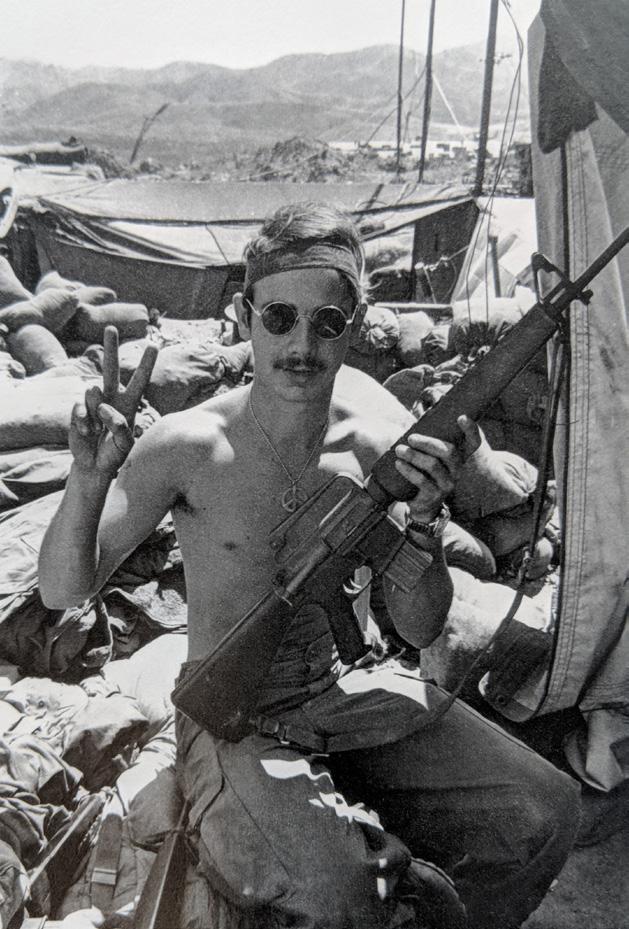

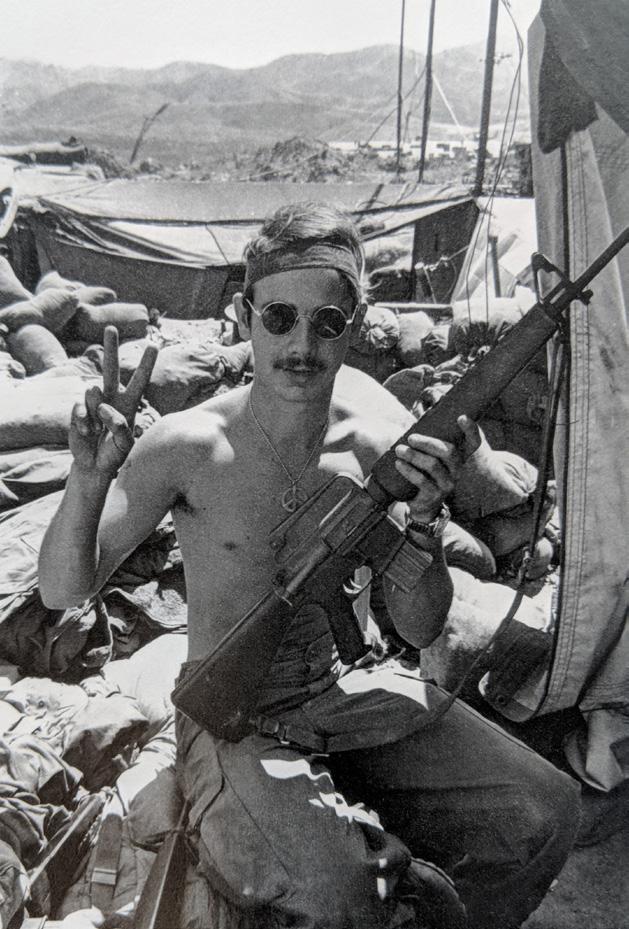

A soldier flashes a peace sign and a rifle in Khe Sahn, Vietnam, in 1971.

A couple shares a fountain-soaked kiss in Central Park, 1969.

PROUD SUPPORTER OF THE NORDIC MUSEUM

Nordic leaders in Bluetech, Cleantech, Edutech, Mobility, Urban Sustainability, and more

May 16, 2019

Nordic Museum

nordicmuseum.org/innovation

Jacob A. Riis

The ideal American

Flemming Just, PhD

Director of Museum of Southwest Jutland

Considered one of the fathers of photography, Danish-American Jacob A. Riis (1849–1914) was a journalist and social reformer made famous by his determination to secure rights and safeguards for New York’s most impoverished workers. He steadily publicized the city’s crises in poverty, housing, and education at the height of European immigration during the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries, when the Lower East Side became the most densely populated place on Earth.

From his job as a police reporter working for the New York Herald and later Evening Sun, Riis developed a deep, intimate knowledge of Manhattan’s slums where Italians, Czechoslovakians, Germans, Irish, Chinese, and other ethnic groups were crammed together in deplorable living conditions. His fresh use of flashlight photography to document the squalid living conditions, homeless children, and filthy alleyways of New York’s tenements was revolutionary, and revealed the nightmarish conditions to a previously blind public. His innovative use of “magic lantern” picture lectures coupled with gifted storytelling and an energetic work ethic captured the imagination of his middle-class audience and set in motion long-lasting social reform. His first book, How the Other Half Lives (1890), preluded the Progressive Era, where social reformers of all kinds—journalists, social workers, church people, philanthropists—partly succeeded in persuading politicians to take action with stricter regulations.

Ahead of his time, Riis used his skills as an investigative photojournalist to give the overcrowded and unhealthy tenements his special attention. Through compelling photographs and commanding speeches, he played a leading role in tearing down some of the city’s worst, most crime-ridden tenement blocks. Similarly, he railed against the dangerous and cramped sweatshops in tenement flats and campaigned against police corruption. With an eye toward the slum’s youngest inhabitants, Riis successfully fought to have

18

Poverty Gap, 1888–1889. Reproduction on modern gelatin printing out paper, original 4 x 5 in. From the Collection of the Museum of the City of New York

Activism

I Scrubs, 1891–1892. Reproduction on modern gelatin printing out paper, original 4 x 5 in. From the Collection of the Museum of the City of New York, 90.13.4.132

playgrounds built throughout the city. In the newly appointed policy commissioner, Theodore Roosevelt, Riis found a kindred spirit in the ardent, efficient reformer. Riis and Roosevelt developed a strong friendship that would last for the rest of Riis’ life.

How the Other Half Lives is one of the most influential books in American literature, translated in numerous languages and still in print almost 130 years later. Equally compelling, Riis’ second best-selling book was The Making of an American (1901). In this open-hearted autobiography, Riis detailed his own incredible life story: from leaving Denmark and arriving homeless and poor in America, to building a career, marrying the love of his life, and finally achieving success in fame and status.

Though first known for his skill as a reporter and author, Riis became a famous lecturer, traveling throughout the United States. He showed his photos as slides in magic lantern shows, sometimes attracting several thousand people to a single lecture. His lecturing tours brought him to Washington several times, and local newspapers treated him as a star and expert on social problems, as noted in a November 21, 1904 Evening Statesman article about an upcoming appearance in Walla Walla::

Jacob Riis coming

Pronounced by Roosevelt “most Useful Citizen of New York”

It is not often that the people of Walla Walla have the opportunity to hear a man with as great a reputation as Jacob A. Riis, the author and reformer.

In the last twenty years, interest in Jacob A. Riis’ achievements and legacy has resulted in countless books and exhibitions about his life and work, both in the United States and in Europe. In June 2019, the Jacob A. Riis Museum will open in his childhood home of Ribe, Denmark. The museum will focus on Riis’ role as both a pioneering photo-documentarist and an influential social reformer. The themes evident in Riis’ work—poverty, immigration, housing problems, and national identity—are all issues that are as relevant today as they were more than a century ago. |

Produced by the National Endowment for Humanities On The Road exhibitions program, Jacob Riis: How the Other Half Lives will open at the Nordic Museum on January 28, 2020.

Reproduction on modern gelatin printing out paper, original 5 x 4 in. From the Collection of the Museum of the City of New York, 90.13.4.104

Reproduction on modern gelatin printing out paper, original 4 x 5 in. From the Collection of the Museum of the City of New York, 90.13.4.191

JACOB A. RIIS | 19

Minding Baby–Cherry Hill, 1892.

Bandits’ Roost, 1887–1888.

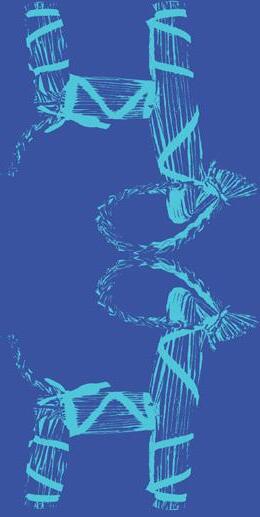

EyeSound: Augnhljóð: Øjenlyd

A conversation in words and images

Devon Kelley

What do you do when the right word won’t come to you? You’re in the middle of a story, you’re on the telephone, you’re giving directions. You’re in Paris and you stumble up to a counter to trip over your high school French vocabulary words: I’d like this thing, if only I could tell you what that thing is. Spoken language isn’t foolproof, and the human tongue isn’t surefire. In that case, you must do more than talk if you want to speak.

Perhaps you pantomime; acting out a silent charade of what is that word!? You use visuals to transmit the essence of the thing. The conversation becomes more than just words: it becomes richer with imagery. We can unspool words—those tricky little alphabet strings—in ways that are distinctly non-verbal. We can replace words with images (which is just trading a symbol for a symbol, after all), and use pictograms to both tell a story and illustrate it, too. Using images, we can cross language barriers and vault linguistic stumbling blocks. We can enrich a dialogue. We can make meaning.

The exhibition EyeSound is such a dialogue: a conversation in text and images.

Danish photographers Iben West and Else Plough created photographic pairings they

then sent to one of four Icelandic writers: Sigurbjörg Þrastardóttir, Kristín Ómarsdóttir, Hallgrimur Helgason Einar, and Már Guðmundsson. The authors would send back their response in written words: the photographers would reply with an entirely new set of photos. This call-and-response exchange in words and images passed between the photographers and each author with up to ten “dialogue shifts” from each writer. In this way, each artist talked to the other.

The photographs should not be viewed, however, as direct representations of the words themselves: they’re a response, not a replacement. Together, they help interpret and catalogue the conversation between the artists. Says photographer Plough: “The photographs should not be seen as illustrations to the words, and the texts are not explanations of the photographs. It is a conversation. The texts and the pictures support each other or work against each other.” In EyeSound, the viewer confronts the result of a conversation that spanned months and countries and transcended language barriers.

The conversation between the photographers and writers may have ended,

but the works still encourage exchange. At the exhibit’s American premiere at the Nordic Museum, West and Plough asked audience members to recite some of the show’s poetic works. During the show’s run, visitors are encouraged to respond to the exhibit with their own words or images on social media.

Plough and West compiled the images and words into a book that’s more than an exhibition catalog—it’s a work of art on its own. In it, the gorgeously reproduced images together with prose allow for an intimate examination by the viewer, while an evocative introduction by another artist (see facing page) expands the discourse.

20

Contemporary Art

Poetry is to life what lamps are to darkness

If an evening is an age and an age is an evening then I will seize time like a ball and fling it to you.

In this way, I jump between ages as if from one planet to another and of course you are with me, because this poem is in the plural.

We remain in different times and swim among the stars, but I always take the ball and fling it over to you over the walls and the barriers.

Sometimes time is on my side as in that song some years back. We heard it as we ran circles around the garage.

PHOTOS

Iben

West and Else Ploug Isaksen

WORDS

Sigurbjörg Þrastardóttir

Kristín Ómarsdóttir

Hallgrimur Helgason Einar

Már Guðmundsson

Introduction

Lars Kiel Bertelsen

False Friends

When two words in different languages resemble each other but nonetheless mean something different, they are called false friends. There are many of them, and the closer they are to us, the harder hitting they become. That’s how it is, I guess, with both words and people. Those we are most familiar with are suddenly not quite how we thought they were, at all. Everyone knows that the Swedish are odd. Odd when they say lunch but mean breakfast. So how can one rely on anything anymore? Narrow-minded footsteps set in motion the journey to Auschwitz. Stop behaving so strangely. Be like us. Learn to speak politely. But, when the ground shifts under you, stout boots are a necessity. If you wear large shoes, then it’s here the joke unfolds, a space where meaning cheerfully collapses, shifts, changes direction like a billiard ball ricocheting off the cushion, and we laugh.

Pictures can also be false friends. Their resemblance to something else is not the same as identity. We recognise this when looking in the mirror and it shows someone else. She makes faces, sticks out her tongue and puts the toothbrush in her ear so one cannot see the sounds for the fits of giggles. Who is making these sounds? Remember to brush your books before you go to bed. Put your teeth in the right place when you’ve read them. Better one foot in the hand than a weathercock in the fog. Don’t sweep anything under the carpet, but let it flow like milk and honey, it’ll all come out one way or another, sooner or later. Don’t become accustomed to fringe benefits; they’re simply blowing in the wind. The soapbox roars when you roll down the blinds. Something bulges out and resembles something else. With your hand on your table: is this what you really mean? |

EyeSound will be at the Nordic Museum through April 14, 2019.

Images, clockwise from upper left

A pair of photos sent to one of the authors. Note the quizzical tilt of each subject.

Another pair of photos sent to one of the authors. Note the strong vertical lines and slight asymmetry in both photos.

EYESOUND: AUGNHLJÓÐ: ØJENLYD | 21

Iben West (left) and Else Ploug Isaksen (right) at the US premiere of EyeSound.

Behind the Scenes of the Viking Age

The Vikings Begin exhibition presents new insights on the critical centuries leading into the Viking Age of the Scandinavian countries. These studies form part of a major research program currently underway at the University of Uppsala in Sweden. Here, project director Dr. Neil Price takes us behind the scenes to share his team’s work in progress.

The Viking Age (c. 750–1050 CE) has long been a touchstone of identity in the Nordic countries, not least in Sweden. Today, the Vikings enjoy a popular recognition common to few other ancient cultures. Their name appears on brands of all kinds, exhibitions of their archaeological remains regularly tour the great cities of the world, and, thanks to the Vikings TV show, they now fill our screens on a regular basis. However, their history has also been reinvented—used and abused to suit the needs of successive generations—in a process that continues today.

This focus on the Vikings and their time has its counterpart in academia, and the last few decades have seen an exciting expansion in research. Viking scholars have examined issues of state formation, the rise of royal power and a unified Church, and their manifestation in the development of towns and other central places. Warfare and

fortification form integral components of these investigations, along with emerging networks of trade and exchange and the handicrafts that fueled them. Rural settlements, courtyard sites, and assembly places have also been intensively studied. As a unifying matrix behind all these processes, the Viking mind has been subjected to scrutiny through studies of religion, ritual, and magic, and by extension burial and the realm of mortuary behavior. The most recent trend has been for the study of the Viking diaspora, a term that marks a new perspective on the uncoordinated processes of migration and colonization.

It would be easy to believe that there’s not much left to know about the Vikings, but it seems that in fact the opposite is the case— we’ve only just begun to scratch the surface of their lives. Despite all this work, one arena of Viking activity remains substantially unex-

plored, and it concerns the very beginnings of this historical trajectory. Who were the first Viking raiders, in a specific sense? Why did they do what they did? What kind of societies produced them, and why did they start to expand so violently into the world at precisely this time? Somewhere in the answers to those questions lie the very origins of the Viking phenomenon: to understand what made the Nordic countries what they are today, we need to know how and why the Viking Age began—not as an artificial construction of historians, but as a real, tangible process of social and cultural change. And thanks to an unprecedented new investment in archaeological research, we may now be on the road to some answers.

The Viking Phenomenon

Three years ago, the Swedish Research Council announced an extraordinary grant of

22

Research

Neil Price, PhD Researcher and Professor at Uppsala University

50 million kronor (about $6 million USD) for the establishment of a new center of excellence for the study of the Viking Age, set up under my direction at the University of Uppsala. The core research group also includes Dr. John Ljungkvist, who for many years has conducted excavations at Gamla Uppsala for the university, and Dr. Charlotte Hedenstierna-Jonson, a specialist in Viking warfare and eastern encounters based at the Swedish History Museum. The project will run until 2025, and during that time the team will be joined by several additional researchers and international scholars, each making targeted contributions to their areas of expertise. The project is designed as an umbrella program sheltering several substrands of research, but the key focus of attention will be on the critical century from 750 to 850 CE and the decades on either side, embracing the early Viking Age and its foundations.

Valsgärde: Boat Grave Culture

At the heart of the project is one of Sweden’s greatest archaeological treasures: the largest cemetery of ship burials ever found: the classic site of Valsgärde in Uppland. The finds from this site lie at the heart of The Vikings Begin exhibition, and this is the first time most of these artifacts

Boat grave 13 from Valsgärde, shown in a beautiful example of the hand-painted documentation that was made from the detailed field records. The grave is contemporary with the Salme discoveries, and dates to c. 750 CE.

Painting by Bengt Schönbäck, 1953

Salme I, the first boat grave to be found on the island of Saaremaa, as it is thought to have looked at the time of burial, with seven dead men sitting up at the oars.

Drawing by Þórhallur Þráinsson © Neil Price

The Valsgärde grave field in Uppland, Sweden, under a stormy sky.

have been displayed outside of Sweden. For more than 400 years at Valsgärde, each generation interred its prominent people of both sexes in magnificent boat graves and cremations filled with objects and animals. Together with the nearby sites of Gamla Uppsala, Vendel, and Ultuna, they tell the story of Sweden and its growth from the heart of the Mälar Valley. Though excavated by Uppsala University between the 1920s and 1950s, the very richness and complexity of the Valsgärde graves has meant that

BEHIND THE SCENES OF THE VIKING AGE | 2 3

Images, clockwise from top

Photo by Johan Anund, Creative Commons

The Vendel Period boat grave 6 from Valsgärde was published in 1942 and contained one of the famous helmets that have become iconic for the Nordic Iron Age. However, the helmet is rarely shown together with its chainmail neckguard, as here.

The late Iron Age power center at Gamla Uppsala, Sweden, as it may have looked near the start of the Viking Age.

CG reconstruction: Disir Productions, used by kind permission

The author together with actor Clive Standen, who plays Rollo in the TV drama series Vikings. Taken in Falaise, Normandy, during filming of the documentary series Real Vikings, a serious component in the outreach activities connected with the project.

they have never been fully researched and published. Now, the definitive analysis of the cemetery and the society behind the burials is one of this research project’s main priorities.

Because the Valsgärde cemetery was in use throughout the later Iron Age, it provides us with a superb lens through which to view the gradual social changes that led up to the Viking Age. We see an emerging kingdom creating itself and signaling its identity through the relationship of the living to the dead. The graves—more than eighty of them in all—were deliberate material statements, preserving the ideas and aspirations of the time in physical form. Although the ship burials have attracted the most attention, interspersed among them are the cremations and chamber graves of women. It is only modern bias that sees one set of gendered burials as being more important than another. We are studying them all.

Alongside raiding and military ideology, among the key questions we want to consider through deeper studies of Valsgärde is the nature of long-distance, international contacts and trade. These have long been recognized as a defining characteristic of the Viking Age, but to what extent were they built on earlier interactions? Clear evidence for links with the East, including as far away as the Asian steppe and the Tang dynasty region of China, can be found in the Vendel period graves, but the nature of those connections has never been adequately explored.

Dr. Ljungkvist and a team of researchers are analyzing the Viking-Age boat graves and all the other burials—along with specialist work on the boats themselves—as well as textiles, animal offerings, and also individual artifact types. The first of the new report volumes has already appeared, and several more are nearing completion.

Salme: The First Vikings?

As a crucial counterpart to this work on an old find is the exploration of a new one: the extraordinary remains of a Scandinavian raiding party, buried in two ships across the Baltic from Sweden, on the Estonian seashore where they came to grief at the very start of the Viking Age. These excavations, undertaken at Salme on the island of Saaremaa in 2008 and 2010–12, arguably

represent the most significant Viking discovery of the last hundred years. Crucially, it has been possible to identify the origin of the Salme raiders: strontium isotope analyses of their teeth show that they most likely came from Swedish Uppland, with a considerable probability that they actually were the people either from Valsgärde itself or from nearby power centers.

The Salme burials are still under post-excavation analysis, but current thinking dates them to around 750—in other words exactly at the critical time when the Vendel Period shades into the Viking Age. It may be that the supposed social shift that comes with the Viking expansion is in fact simply the external projection of processes that had long been underway inside Scandinavia, and one of our tasks in the project is to critically probe and perhaps dismantle this Vendel–Viking border.

The discoveries at Salme present us with an unprecedented opportunity to examine the specific culture behind the very first raids, and to do so from a Swedish perspective. Crucially, the Salme expedition, whatever it really was, occurred nearly half a century before the classic beginning of the Viking Age: the famous raid on the Northumbrian monastery at Lindisfarne in 793. This implies that the origins of raiding might well lie within the Baltic sphere, with a focus on the east, not looking westward as the traditional models would have it. This is actually what we should expect and is also supported by later written sources, hard though they are to interpret with confidence. Metaphorically speaking, the Salme men were some of the “first Vikings” and provide a great opportunity to more deeply explore these issues.

As part of the Viking Phenomenon project we are happy to be able to provide substantial funding support to the Estonian team working on the Salme finds, led by Dr. Jüri Peets at Tallinn University. His team of three researchers, together with Dr. Marge Konsa from Tartu University, have now been working on the finds for two years and the two-volume Salme report is scheduled to appear in 2021.

One of the primary project outputs will thus be the final publication not only of the Valsgärde cemetery excavations but

24 | NORDIC KULTUR

Images, clockwise from above

Drawing: Harald Faith-Ell, 1941

Photo by Peter Findlay

also of the Salme boat burials. Combining Valsgärde and Salme, we have the unique opportunity to reveal the world of the first Vikings, at “home” and “away,” in a kind of project never before attempted.

Viking Economics

Underpinning these early Scandinavian enterprises was what we have chosen to call “Viking economics.” We mean this literally, as the economics of Vikings in the exact sense of that word, rather than referring to the general economic systems of Viking-Age Scandinavia. In contrast to the widespread exploration of the silver trade, a genuine study of raiding economics has never been undertaken—and yet they must, almost inevitably, have provided a prime motor for the developing social processes that embody our definition of the entire time period (and which are so clearly reflected in places like Valsgärde).

Here we see the Vikings as players in wider arenas, ones that involved all members of society. Our interpretations strive to include all the Viking-Age people of Scandinavia equally, regardless of their gendered identities (which we have long known went far beyond the binaries of biological sex). New research suggests that women played far more active roles in the Viking campaigns than has previously been supposed. Another neglected issue is the fundamental importance of slavery and slaving, not only to Viking economics but to the very fabric of society; the unfree have been left out of our models for too long. A vital thing to understand is that activities that were once discussed separately were in fact part of the same process: raiding was slaving, and this in turn was trading, in a loop of social feedback powered by maritime violence and movement. Piracy is another key element in this complex picture, and a field of specialist study that has much to offer Viking scholars.

International, cross-cultural comparative studies will add a further dimension to these investigations, drawing on the historical archaeology of early modern colonial contexts in the Atlantic, the Caribbean, the Pacific, and the Far East. Of course, we do not simply take interpretations from these distant time periods and drop them onto the Viking Age, but they provide useful

platforms from which to think, new ways of seeing the eighth to eleventh centuries in the North.

Under the direction of Charlotte Hedenstierna-Jonson, the Viking Economics strand has also brought in a range of other scholars, including Dr. Gareth Williams of the British Museum and Dr. Ben Raffield, formerly of Simon Fraser University in Canada and now at Uppsala. Both are specialists in Viking warfare and army structures, while Dr. Raffield also works on slavery. An economic historian from Lund University in Sweden, Dr. Anders Ögren is also contributing his expertise. The team will grow as the project progresses. Over the past three years, this strand of the project has published numerous papers (all available online on Open Access) and held several international workshops, resulting in edited volumes that are currently in preparation.

New Perspectives on the Viking Age

Numerous publications are planned over the coming years, including cemetery reports from Valsgärde and Salme, general syntheses, and more peer-reviewed journal papers.

The project’s public outreach also includes interactive events organized at sites such as Gamla Uppsala, with reenactors and craftworkers, and we hope to make reconstructions of some of the burial finds from the boat graves. The Uppsala University spin-off company Disir Productions is creating geolocated apps for tablets and mobile devices, enabling visitors to sites such as Gamla Uppsala to literally walk through computer-generated reconstructions of the Iron Age past. The technique is known as “augmented history,” and similar apps are being developed for Valsgärde and related monuments.

Lastly, all the core members of the project team are involved in television consultancy on Viking documentaries for several international broadcasters, reaching very large audiences indeed. In particular, our team has filmed Real Vikings for History Channel in Canada and the US, which links directly to their Vikings drama series. Through the medium of one of the most popular current gateways to Viking culture, we’ve worked with cast members at actual archaeological sites and in museums, dis-

cussing the reality behind the fiction.

It is important to understand that the project will not provide “the Answer” to “the Question” of the Viking Age, but rather a particular set of responses to the questions that we think to ask. Other scholars might choose quite different lines of approach, and this is to be welcomed. Our project is a living one, situated in our own times, as it must be.

With a new understanding of the Viking phenomenon as its objective, we hope that this project will create Sweden’s leading center for the study of this critical time period in the nation’s history. The Vikings are still today the most visible signal of Scandinavian heritage, and this research program is deeply embedded with contemporary concerns, presenting the exploration of this long-lasting legacy for the widest possible public—an endeavor in which The Vikings Begin exhibit plays a major part. |

BEHIND THE SCENES OF THE VIKING AGE | 2 5

The Vikings Begin will be at the Nordic Museum through April 14, 2019.

Nordic-inspired fare for the Pacific Northwest palate.

Open during museum hours

nordicmuseum.org/cafe

Museum Store

The best in imported and local Nordic art, housewares, textiles, gifts, books, accessories, delicacies, and more.

Open during museum hours

nordicmuseum.org/museumstore

26

Photo by Barbie Hull Photography

Capital Campaign Donors

$5,000,000 + Allan and Inger Osberg; Osberg Family Trust; Osberg

Construction

A.P. Møller and Chastine Mc-Kinney Møller Foundation

$3,000,000–

$4,999,999

Floyd and Delores Jones Foundation

Jane Isakson Lea and James Lea

Scan|Design Foundation by Inger and Jens Bruun

State of Washington

$1,000,000–$2,999,999

Barbro Osher

Pro Suecia Foundation

Breivik Family Trust

Jeff and Linda

Hendricks Family Foundation

Lars and Laurie Jonsson Family

Karen L. Koon and PD and Evelyn

Koon

Jane Isakson Lea and James Lea

King County— 4Culture

Synnøve Fielding and Robert

LeRoy

Kaare and Sigrunn

Ness Family

Einar and Emma

Pedersen

The Family of Einar and Herbjørg Pedersen

The Røkke Family

John and Berit Sjong

$500,000–$999,999

City of Seattle

Earl and Denise Ecklund

Jon and Susan Hanson

M. J. Murdock Charitable Trust

Nesholm Family Foundation

The Norcliffe Foundation

Robert L. and Mary

Ann T. Wiley Foundation

$100,000–$499,999

Pirkko and Brad Borland

Raymond R. Brandstrom

Alan and Sally Black

Jan and Priscilla Brekke

Svanhild and Russell Castner

Patricia and Robert Charlson

Raymond and JoAnne Eriksen

Kari Gilje and Michael Chiu

John and Shawn Goodman

Joshua Green Foundation

Jon Halgren

Peter Henning

Stan and Doris Hovik

Icelandic Club of Greater Seattle

Erik and Diane Jackson

Leif and Sarah

Jackson

Bill and Michelle Krippaehne

Bertil O. Lundh

Family

Cindy and Leif

Mannes

Egon and Laina

Molbak

David Nelson

Arne Ness

Donald and Melissa Nielsen

Nordic Council of Ministers

Everett and Andrea

Paup

Will and Chris Siddons

Sons of Norway, Wergeland

Lodge #21

Maria Staaf and William Jones

Marvin and Barbara Stone

Nina Svino Svasand and Ernest Svasand

Norman Kolbeinn Thordarson and Judy Thordarson

Leo Utter

$50,000–$99,999

Anonymous

Per and Inga

Bolang

Arlene Sundquist Empie

Irma and Don Goertzen

Dr. C Ben Graham and Pearl Relling

Graham

Charitable Trust

Gunnar and Heidi

Ildhuso

Kristen Lindskog

Jarvis

Douglas and Ingrid

Marken Lieberg

Marilyn and Rodney Madden

D.V. and Ida

McEachern Charitable Trust

Albert Victor Ravenholt Fund

Reimert and Betty Ravenholt

Skandia Music Foundation

Patsy Berquist

Richard Franko and Family

Jim and Anna Freyberg Family

Gertrude Glad

Raymond Gooch and Robyn J. Middleton

John Gundersen

Jay Haavik

Fred and Karin

Harder

Helen K. Hagg

Elling and Barbara

Halvorson

Electa Skeie and Ola Hendricks

Small and Lawrence R. Small

Judith Tjosevig

$25,000–$49,999

Hans and Kristine Aarhus

Lotta Gavel-Adams and Birney Adams

Brandon Benson

Leif Eie

Steven J. Jones

Sven and Marta Kalve

Georgene and Richard Lee

Leif Erikson

International Foundation

Tom and Drexie

Malone

Karl Momen

Valinda and Lyle Morse

Eric and Yvonne Nelson

Peach Foundation

Perkins Coie LLP

Pigott Family

Lisa and Charles Simonyi

Karsten and Louise Solheim

Alf and Sonja Sørvik

Svend and Lois Toftemark

Tor and Ingrid Tollessen

Turnstyle

$10,000–$24,999

Chris and Terrie Rae Anderson

Janice Anderson

Ballard Alliance

Ballard Transfer

Steven and Kathleen Barker

Karin Ahlstrom Bean

Kenneth M. Beck

Evelyn Birkeland Richter and Kimberly Richter

Shirley

Paul Birkeland

B&N Fisheries Company

Cascade Business Group

Jan and Mike Colbrese

Sonya Campion

Vanguard Charitable

Danish Brotherhood Lodge #29

Daughters of Norway, Valkyrien Lodge #1

Lynn and Ross Davidson

Etienne and Nancy

Debaste

Mark and Susan Dibble

Francisca Erickson

Sigmund and Torborg Eriksen

Ellen Ferguson

Gunilla and Jerry Finrow

Lorraine Toly

Dan Durham and Susan Laurie

Tusa

Betty Nes Wabey

Johanna Oma Warness and Vidar Warness

Louise B. Wenberg

Luce

Asmus Freytag and Laura Wideburg

$1,000–$9,999

Steve Aanenson

Page Abrahamson

Casper Sorensen and Soomie Ahn

Family

Petra Hilleberg

Mari-Ann Kind

Jackson

Brent and Catherine Johnson

Kevin and Penny Kaldestad

King Gustav VI Adolf’s Foundation for Swedish Culture

Kirtley-Cole Associates LLC

Lowell and Shirley Knutson

Knifton’s Neighbors LLC

Kone, Inc.

Krueger Sheet Metal Company

Olaf Kvamme

Anne-Lise Berger and Ozzie

Kvithammer

Patricia J. Lundgren

John and Hanna Liv Mahlum

Norman and Constance McDonell

Mithun

Mountain Pacific Bank

Alice Ness

Bruce and Jeannie Nordstrom

Eldon and Shirley Nysether Family

Sigurd and Else Odegaard

Paccar Foundation

Pacific Fisherman Shipyard

Jane and Darryl K. Pedersen

Rick Peterson

The Pinkerton Foundation

Louis Poulsen

Lena Powers

Mr. and Mrs. Andrew Price

Megan and Greg Pursell

Kari Record

The Robinson Company

Jan and Martin Rood

Greta HaagensenRoseberg and Lee Roseberg

Börje and Aase

Saxberg

Peter Davis and Kristiann Schoening

Karin Gorud Scovill

Skandia Folkdance Society

Jay Smith

Snow & Company Inc.

Harriet Spanel

Inger Svino

SWEA Seattle

Swedish Finn Historical Society

Donald and Kay Thoreson

Bill Briest

Perry Brochner

Diana Brooking

Lisa Brooks

Douglas and Betty Brownlee

Beverly A. Browne

Jackie Brudvik

Scott and Cathleen Brueske

Jette J. Bunch

Ward and Boni Buringrud

Bunnee Butterfield

Sarah Callow

Carrs Family

Gloria Mae Campbell

Rick and Marlene Akesson

Kay Lynn Alberg

Richard and Constance Albrecht

Myrna Amberson

Edward Almquist

Bruce and JoAnn Amundson

Ebba and Ingvar Andermo

Pamela Andrews

Rosemary Antel

Paul B. Anderson

Kitty Andert

Ruth Andersen

Anne-Line Anderson

Orville Anderson

John Mitchell and Marie Anderson

Theresa Appelo Bakken

Joan Armitage

Tim Ashmore

Susan and Gary Atwood

Tina Aure

Celeste Axelson

Leanne Olson and Jim Bailey

Bainbridge Community Foundation

Jens Bakke

Kristen Bakken

Rotary Club of Ballard

Kay Barmore

Laila Barr

Ken and Sheila Bartanen

Ingrid Bauer

Ellen Margrethe Beck

Patti Benson

Nadine Benson

Nan Bentley

Dwayne M. Berg

Margaret Berg

Melanie Berg

David Fluharty and Lisa Bergman

Keith and Kathy Biever

Frances Bigelow

Erik Birkeland

Sally L. Bjornson

Luther Black

Robert and Connie Blair

Elizabeth and Steven Blake

Eileen M. Blume

Sandra Boeskov

Janice Bogren

Bernard Bolton

Andrea Bonnicksen

John and Tonjia Borland

Robert Born

Lillian Bornemeier

Steve Bottheim

Katherine Boury

Diane Bowe

Ellen D. Bowman

Cathy Brandt

Anna Brannen

Eugene Brekke

Lita Breiwick

Embassy of Sweden, Washington

Otto Enger

Harbor Enterprises, Inc.

Olav Esaiassen

Candace Espeseth

Ruth Estabaya

Thomas and Willy Evans

William and Sandra

Evenson

Ingrid Fabianson

Jim and Birte

Falconer

Barbara and Frank Fanger

Lance Farr

Eric Carlson

Jean K. Carlson

Paul and Beverly Carlson

Elaine and Richard Carpenter

Carsoe US Inc–Seattle

Steve and Liz Cedergreen

Robert and Katherine Cederstrom

Diane Chapman

Joanne Chase

Jean Chen

Jordan Chester

Amber Christensen

Louis and Anna Christensen

Carol L. Christiansen

Per Christensen

Alison Church

American Seafoods Company LLC

JoEllen Connell

Nelson R. Cooke

Peggy Jorgenson

Cooper

Stuart Mork and Laura Cooper

Trident Seafoods Corporation

Timothy P. Cosgrove

Pacific Nordic Council

Debra and Chris Covert-Bowlds

Stina Cowan

Jennifer and Jerry Croft

Reidun Crowley

Ragnar Dahl

Susanne Daley

Danes Soccer Club

Karrin A. Daniels

Danish Sisterhood Lodge 19

Daughters of Norway, Nellie Gerdrum Lodge #41

Marguerite David

Signe Davis

Nancy Debaste

Carol Delahoyde

Embassy of Denmark, USA

Doug and MaryAnne Dixon

Joanne Donnellan

Joy and Bob

Drovdahl

Ia Dubois

Robert and Beth Dunn

Bill Weed and Pam Dymond-Weed

Larry and Sidra

Egge

Erik Egtvet

Sandra Egtvet

Donna Eines

Ned and Nanette Eisenhuth

John and Linda Ellingboe

Embassy of Finland, Washington DC

Marja Hall

The Steven L Hallgrimson Foundation Inc.

Robert Hamilton and Catherine Fox-Hamilton

The Hansen

Foundation

Geraldine Hansen

John Martin Hansen

Les Hanson

Richard and Marilyn Hanson

Peter Hanson

Carolyn Haralson

Bill Harbert

Christopher Hardy

Susan Haris

Odd and Nora Fausko

James Feeley

Joan Valaas

Ferguson

Joyce Ferm

Michael Fiegenschuh

Virginia and Les

Filion

Finland Room

Committee

Richard and Pamela Firth

First Interstate Bank

Gary and Maureen Fisker

Shirley Fjoslien

Martha Fleming

Robert Flemming

Christie Most and Rich Folsom

Viggo Forde

Allison Foreman

Helen Fosberg

H. Weston Foss

Sonja Foss

Craig Foss

Joanne Foster

Gwyn and Rick Fowler

Karen Fowler

Linda P. Fowler

Franklin Templeton

Investor Services

Eric Fredricksen

Sharon Friel

Alan and Lisbeth Fritzberg

Ann Fuller

Marilyn E. Fuller

Annelise Gaaserud

Lisa Garbrick

Marc Garcia

Lael Gedney

James and Marilyn Giarde

Maren Gibson

Robert and Margaret Giuntoli

Marianne and William Gjertson

Glacier Fish Co., LLC

Jeff and Miyako

Gledhill

Linda Glenicki

Britt Glomset

Nancy Goodno

Laurie LundGonzalez

Inger and Ulf

Goranson

Robyn Grad

Gary and Bonnie Graves

Sharon Greenwood

Kay Gullberg

Kirsten and Erik Gulmann

Karin Gustafson

Paul Friis-Mikkelsen and Rita Hackett

Richard and Eivor

Von Hagel

Jack and Elaine

Hakala

Lisa and Daniel Hall

Gary Haarsager and Carol Knoph

Michael & Margaret Hlastala

Sandy Haug

Peter and Pat Haug

Irving and Vernamell Haug

Wally and Kristin Haugan

Norman Haugen

Dee Dee Hawley

Hawley Realty

Kristin Heeter

Paul and Kathleen Hendricks

Ann Hengel

Paul Heneghan

Lauri Hennessey

Woody and Ilene

Hertzog

Lena LönnbergHickling and Mark Hickling

Lawrence E. Hicks

Gunvor Hildal

Herb Bridge and Edie Hilliard

Diane Hilmo

Kristiina Hiukka

Sharon Hitsman

Shirley Hobson

Ruth HoeghChristensen

Nancy and Charlie Hogan

Anna Holliday

Susan Johnston and Jerry Hollingsworth

Roy Holmlund

Karen Holt

Tore Hoven

Michael Hovey

C. David Hughbanks

Susi Hulbert

Janet and Steve Hunter

Robert E. Ingman

Ivar’s Corporation

Iverson Family

Marilyn Iverson

Jan Carline and Carol Sue

Ivory-Carline

Curtis Jacobs

Ken and Rachel Jacobsen

Jon Jacobson

Paul and Carole Jacobson

Seppo T. Jalonen

Don and Lynne

Jangard

Vicky Jaquish

Deborah and Steven Jensen

Ernst and Linda Jensen

Sara Jensen

Eva Long and Bill Jepson

Eva and Lars

Johansson

Isabella Backman Johnson

Carol Oversvee

Johnson continued

List compiled January 2019 27

SPOTLIGHT: The Nordic Legacy Circle

We are humbled by the generosity of our Nordic Legacy Circle members and the support they have given us by allowing their legacy to become a part of ours.

“Our fabulous new museum gives me more reason than ever to help the Museum succeed in its mission of sharing Nordic culture and values with all people, not just for my lifetime, but for many, many generations to come. I am so proud of the new facility and so excited about the reception it has received. I want our children’s and grandchildren’s generations to continue to feel the connection to the Nordic countries, and want to share the Nordic piece of the American mosaic with other people. The Nordic Legacy Circle helps us all to continue our support even after we are gone.”

—Pirkko Borland

“I chose to join the Nordic Legacy Circle because I trust the Nordic Museum’s vision and mission to accurately share the Nordic story—its spirit, culture, and history—with the larger community. Legacy giving for those of us who are not in a position to give much now is a way of paying it forward, strengthening our beloved Nordic Museum, and ensuring its future. It is also a statement of my values, and may inspire others to give, to embody the values of and the passion we share for the Nordic Museum and its commitment.”

—Mari-Ann Kind Jackson

“Although I am proud of my German and Irish ancestry, I have learned over the years about my having relatives living in both Denmark and Sweden. The Nordic Museum provides a sustainable means by which to enjoy my combined European and Nordic heritages through programs and activities here today, as well as to ensure them for others tomorrow.”

—Kevin G. Beder

“I have had a great time as a volunteer and doing what I can as a member. I have always enjoyed learning about the many different cultures that represent the Museum. I chose to join the Legacy Circle as a way of giving back, to let others continue to learn in the future.”

—Todd Clayton

For more information about the Nordic Legacy Circle and its benefits, or to donate to the Capital Campaign, please contact Development Manager Jenny Iverson at jennyi@nordicmuseum.org or 206.789.5707 x7038.

Jerome and Susannah Johnson

Noreen Johnson

Richard and Ingri Johnson

Erik Johnson

K. Robert Johnson

Bonnie Johnson

Larry Johnson

Sirkku and James Johnson

James and Dianne Johnston

Suzy Johnston

Bob and Oddny Johnston

Linda Jangaard and Stan Jonasson

Grace CarlsenJones and Roger Jones

Ellen Jordal

Martin Josund

JP Morgan Chase

Mary Junttila

Pat and Paul Kaald

Michael Kahrs

Pirkko Karhunen

Camille Kariya

Christina B. Katsaros

David and Sherry Kaufman

Michael and Michaela Kay

Helen Kearny

Arnold and Martha Kegel

Jim and Cris Kelley

Leigh Kvamme Kennedy

Darlene Kenney

Linda A. Kent

Keybank Foundation

Harry Khamis

Jan and Alita Kiaer

Aaron Kitson

Henning Knudson

Peter and Janice Kolloen

Richard A. Korpela

Jackie Kozdras

Paul Kromann

Jack and Eleanor Krystad

Steven Kvamme

Judy Ladd

Oscar and Joyce Lagerlund

Kristen Laine

LairdNorton Wealth Management

Sigrun Susan Lane

Monica Langfeldt

John and Betty Langkow

Mina and Raymond Larsen

Jimmy Larsen

Eric B. Larson

Kristina Larson

Linda Larson

Willard Larson M.D.

Kristin Lasher

Daniel Laxdall

Leadership Tomorrow

Alumni Association

Solveig M. Lee

John & Don Legg

Finn Lepsoe

Adrian Leven

C. Stephen and Donna Lewis

Kerstin Liland

Vivi-Anne Lindback

Mary Lindholm

Kathleen Lindlan

Elmer and Joan Lindseth

John Linvog

Steve Jensen and Vincent Lipe

Lithuanian American Community, Inc Washington Chapter

The Lockspot Café

Pat Loftin

Gary and Kaisa

London

Flemming L. Lorck

Donna Lou and Peter Bladin

Svenn L. Lovlie

Limback Lumber

Erna Lund

Gil Lund

Ivan Lund

Jo Ann Lund

Kristy Lunde

Renee Lund

Olav Lunde

Patricia J. Lundgren

Steven Lundholm

Florence Lundquist

Lori Lynn Phillips and David Lundsgaard

Birgit Lyshol

Jon Magnusson

Josephine and William Mahon

Ann Maki

Victor and Karen Manarolla

Eva and Heikki Mannisto

E A Marks

Kristin Martin

Cheryl Matakis

Tom and Carolee Mathers

Heidi Mathisen

Yara Silva and Lars Matthiesen

Julia Maywald

Colleen McArdle

Gary McCausland

Karen McGaffey

Jim McManus

Robert S. McEwen

Eeva and Jeffrey McFeely

Jason and Rebecca Meaux

Dick Medina and Joyce Gauntt

Medina

Tushar Mehta

Bruce and Carol Meyers

Kaare Mikkelsen

Karen Mildes

Jennie Mildes

Ronda and Brad Miller

Darlene and Rick Miller

Joan Miller

Luanne and John Mills

Don Moe

Maiken MoellerHansen

Megan Knight and Alison Mondi

Arya Monson

Andrew Snoey and Kelly Morgan

Laura Cooper and Stuart Mork

Kay Most

Katie Moulster

Lynn Mowe

Lynnette M. Muenzberg

Ritva and Harvey Musselman

Laurie Boehme and Mark Muzi

Irene Myers

Peter and Mary Ann Namtvedt

Brian and Nola

Nelson

John & Harriet Nelson

Isa G. Nelson