9 minute read

Introduction

Abstract Heritage in Beirut Myriad of Islands Project Proposal & Manifesto 7

How can acts of restoration be utilised and manipulated on ruins in Beirut in order to accommodate new queer spaces?

Advertisement

The Environmental & Technical Studies (ETS 5) thesis aims to develop a strategy to reuse existing heritage structures in Beirut in order to design ‘Third’ spaces for queer bodies in Beirut. Instead of demolishing recent ruins and rebuilding structures from new - adding more chaos to the fragments of the city - the thesis aims to explore different techniques of re-use that mutually deal with heritage restoration and the needs of queer bodies.

These heritage building are in danger as they have no legal protection. Current legislations date back to the 1930’s and only protect structures that were built before the eighteenth century. This allows current developers to exploit the ambiguous system and destroy the vast number of houses that remain.

Many of the historic buildings that characterise the architectural heritage of Beirut have already been lost since the 1990’s. Due to the reconstruction works after the civil war, urbanisation and globalisation, some developers have found an opportunity to demolish these original structures and build unintegrated skyscrapers. Even the structures that were saved back then were always threatened by ‘unintentional’ demolition. Now, after the explosion that occurred on the 4th of August 2020, some professional restorers and local NGOs have began protecting the remaining heritage and attempting to keep them standing using temporary scaffolding techniques, mesh protection and temporary roof fittings.

As part of the proposal, a new institution: ‘Bayt Akhar’ is formed. Acting on the duality of heritage restoration and queer production, it aims to create new brave spaces of care for the queer bodies of Lebanon, whilst re-birthing the rich heritage of the city. The report is intended to be used as a manual; where one site was chosen from approximately 250 potential heritage buildings (83 of which were around the immediate radius of the explosion), which can then be replicated to simultaneously deal with heritage restoration and the production of queer spaces - to enhance the legislation and realisation of queer bodies in Beirut, Lebanon.

The report is presented in 9 chapters; 7 of which are part of the institution’s manual. I will firstly discuss the urgent need of care for some heritage buildings that have recently been impacted by the blast, then convey the ways in which Queer bodies currently occupy the city, and the need of a physical space that inhabits safety and care. I will then demonstrate the method of extrapolating the potential sites of intervention and the act of surveying as both an archival and measurement tool. Then, the chosen site will be used as a primary example of re-use, re-design and re-build; starting off with the existing structure and the urgent maintenance required to protect it, then the tools of re-designing the ways in which the spaces work, and finally, the strategies in which the proposal will take place. These strategies act on both the old and the new; dealing with the existing language and re-shifting its use to allow it to be used by queer bodies.

Beirut, 1920

The heritage value of the Gemmayzeh and Mar Mikhael neighbourhoods dates back to the 19th century, with their architecture of the Ottoman and French mandate eras. They were among the first built after the expansion of the city of Beirut and of the few that still constitute a coherent historic urban fabric, only slightly affected by contemporary development. The Ottoman era architecture from the second half of the 19th century highlights residential buildings and villas with red tiled pitched roofs and large central halls featuring the famous triplearched bay, emblematic of Beirut.

Beirut is known to be rich with heritage buildings representing the architectural glamour of the Ottoman and French-mandate eras. Article 26 of Lebanon’s preservation laws dating back to 1933 legally obliges the Lebanese government to reimburse owners of buildings it has classified. This same obsolete heritage law preserves only monuments built before 1700.

Source: Saliba, R. (1998). Domestic Architecture between Traditionvand Modernity. Beirut: OEA.

Currently no new legislation has materialized concerning preservation of heritage buildings, despite efforts by former Culture Minister Raymond Areiji in 2016 to draft an updated heritage law. According to Areiji, the number of remaining heritage buildings in Beirut is 500. This number of enduring heritage buildings has decreased over time and more so following the unfortunate Beirut blast that occurred on August 4, 2020. As a result, 640 historic buildings (including heritage buildings) were damaged, 60 of which are at risk of collapse. The damaged buildings include old homes, museums, religious sites and cultural landmarks like Sursock Museum.

Lebanon has a rich and diverse heritage inherited from many civilizations that existed on its territory. Lebanon, once home to the Phoenicians, has been colonized and conquered by many countries, all of which left a huge cultural heritage and traditions in the country. Lebanon’s heritage mostly dates back to the 19th century, and it has been largely and mainly influenced by both the Ottoman and the French eras. Among Lebanon’s huge heritage are the traditional and historical buildings that are mostly still present in Lebanon’s capital city, Beirut. Unfortunately, Beirut’s historic buildings are now at risk of collapse following the devastating explosion that rocked the port area of the capital, on the 4th of August 2020, and destroyed parts of the city and the surrounding regions, such as Achrafieh, Gemmayze, Rmeil, Medawar, Karantina, and Mar Mikhael. That is why Lebanese officials and architects around the country are calling for quick action on reconstructing, preserving, and restoring these houses, in an effort to preserve Lebanon’s culture.

The growth of Beirut domestic typology; 1840 - 1920

Source: Saliba, R. (1998). Domestic Architecture between Traditionvand Modernity. Beirut: OEA.

The urban fabric of the city visualises the constant war between the intended heterogeneity of the urban form, and the mere individuality that results. The city could be described as a ‘myriad of islands,’ a territory divided into fragments, each representing a specific agenda. Hitherto, the fragments represented a specific religious affiliation, demonstrating a distinct social identity and way of life. Today, religious affiliation is replaced by political ideologies, a mean of occupying space as an access to power; both a foreshadow to the political climate to come and a mere representation of the city’s violent history.

“The city of Beirut was at once the product, the object, and the project of imperial and urban politics of difference: overlapping European, Ottoman, and municipal civilising missions completed in the political fields of administration, infrastructure, urban planning… and architecture”.

Hanssen, J., (2005). Fin de Siècle Beirut: The Making of an Ottoman Provincial Capital. Oxord: Clarendon Press. p. 4.

Port of Beirut: point of impact from the blast

Site

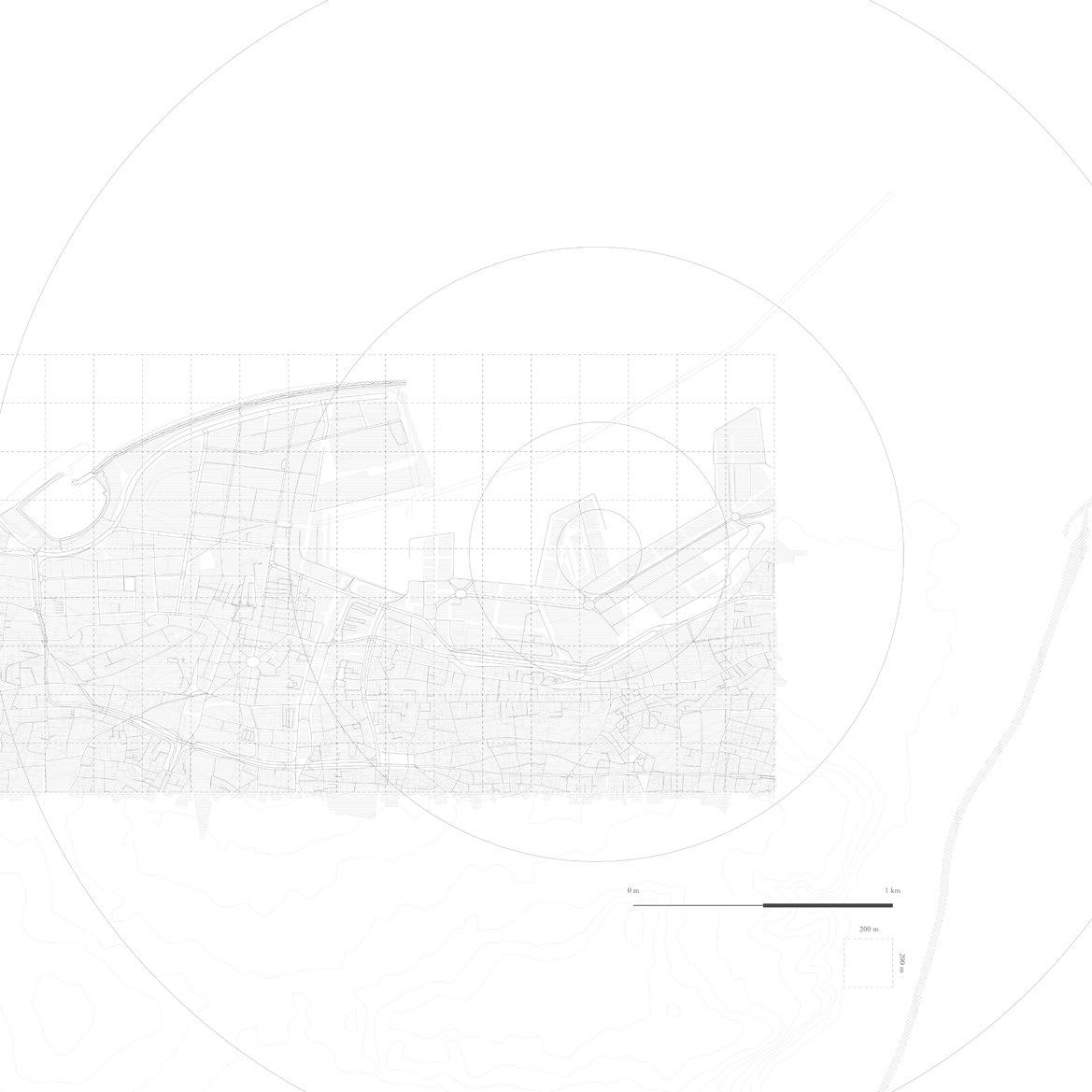

Focus area of Gemmayzeh and Mar Mikhael. Land use showing industrial, commericial, park, and heritage sites

August 4 2020

On the 4th of August 2020 - in the midst of a global pandemic, a national economic crisis and a continuously evolving government regime - an explosion erupted at the main port of Beirut, destroying the surrounding areas, killing over two hundred people, and impacting infrastructure, homes and people more than 10 kilometres away from point of impact.

People were left in a state of isolation, where systems of care and solidarity are lost, Parallel to the post-civil war period in Beirut, and the many disruptive situations that occurred since, this serves as a platform for potential possibilities of a new democracy and political reform.

It mainly interrupted what is known as the ‘hip’ district, Gemmayzeh and Mar Mikhael. A place of heritage and migration where buildings have witnessed and endured two world wars, a fifteen year civil war and several Israeli attacks.

Now, the country remains divided, and a new agenda for fostering a network of care commences.

Existing

Urban Heritage

Queer community

Project: sex, ruin(s) & (3rd) space

Urban Heritage

Queer community

The project deals with the mutuality between the urban fabric, the neglected heritage and the ignored queer community. It aims to encompass and join the elements that have been forgotten and attempt to bring back the rich heritage of the city whilst giving space to a new public sphere for a group of queer individuals.

Using the sites impacted by the explosion, can those spaces of heritage and destruction become potential spaces for productive queer spaces?

I propose an institution that acts on both rebuilding heritage whilst creating spaces of the future. The aim of queer visibility is not to include queers in the dominant ‘heteronormative’ culture, but to continually question normativity in the public spheres. The notion is to take the concept of defensive and offensive spaces and potentially use architecture as a tool to progress the legalisation of queer bodies in Beirut.

Object -> Room -> House -> Street -> City Micro -> Macro

Countercultural Centre - an anti-institution:

The project is an archive; a collection of images, videos, voices and buildings - that all have the same goal to progress queer rights. The design serves as a house and an educational centre, of a counterculture, to legitimise the community as a present group within the city, to protect their safety, house the vulnerable and to educate ones within and out on the history and importance of the queer subculture.

The project (design) aims to build a sharing platform that will try to create aspiration for the surrounding, and be a catalyst for better communication between the queer community and the majority.

The acts proposed include :

(1) Identify the needs of members of the queer subculture; their needs, safety, inclusion-related concerns through intersectional relationships.

(2) Extract sites, plots and buildings that require rehabilitation and/or care.

(3) Survey specific sites to discover context-specific elements or fragments that determine the language of existing structures.

(4) Determine urgency of physical care to existing structures and spatial possibilities.

(5)Rebuild and (re)design the network of spaces to create a gradient of privacy within and their relationship to the internal and external members, the public and the city.

(6)Ultimately, build a shared platform that will question the normative whilst generating a safe space of inclusion within the institution and its affiliations.

Demolition Preservation

Restoration

(Adaptive) Re-Use

The different tactics of heritage care can be utilised to mutually deal with the delicate heritage and to fit the new purpose of the institution.