12 minute read

Building Stronger Readers and Writers through Character Analysis

Dr. Roberta D. Raymond

Building Stronger Readers and Writers through Character Analysis

Advertisement

The students were scattered around the room with their classmates. Some were working alone, others with a partner, and some in a small group. The classroom was alive with constructive conversation as students actively discussed the characters from the books they were reading. The conversations were animated and sometimes intense. Dozens of students had their character trading cards clipped to their pants and they were discussing the latest books they had read. As I continued a student conference, two voices rose from the back of the classroom; the character literary mock trial was getting heated. There were also several students grouped on the floor developing wanted posters, creating a character analysis activity, and sharing their stories with each other. The students were bringing the elements of fiction to life in the classroom.

The scenario above is not always the scene that is playing out in the classroom. Students are not always able to connect to the character, even when reading books of choice. Students do not know how to analyze the characters in the stories they were reading. This cripples their enjoyment of and connection to the characters in the story; this can create both conversational and instructional obstacles in literature circles and reader’s workshops.

Character Type and Reader Motivation

Different characters drive the plot of different stories, and a reader's enjoyment of a character may be dependent on the character type. Typically, a story consists of a main character, or protagonist. The story's plot is centered around the protagonist, hence a reader who cannot relate to the protagonist may experience difficulty engaging in the story's plot. Such a situation provides an opportunity for an instructor to enhance a student's background knowledge through further exploration and analysis of the protagonist, including their motives, decisions, and relationships to other characters in the story. One of the other characters in the story may be the antagonist, or character who challenges the protagonist by influencing or creating the story's central conflict. Analyzing and discussing how the protagonist responds and interacts with the antagonist is another approach to increasing a reader's engagement with the text. Because a wellwritten character demonstrates complex and multi-faceted layers of interpretation, a student's initial opinion of a character can change throughout a story, allowing for additional instructional opportunities; character type matters.

Why Character Analysis?

Graves (2005) posits, Students deserve vivid characters-characters who are funny, flawed, hopeful, and triumphant. We who teach and read to children need to ensure their capacity and opportunities to become lost in books, immersed in the characters who lead them through patterns of living--patterns that are near to them, or wonderfully imagined. (p. 5)

Diving into character analysis enables student readers to make connections to characters in the stories they read, so readers are then able to apply these connections to the stories as well. Often, the critical relationship developed between reader and character is so strong that students feel as if they are real (Parsons, 2013). Roser and Martinez (2005) express, “it is through characters that readers come to care about and connect with literature; characters entice us to stick around and make literary meaning” (p. VI). This strong understanding of character enhances comprehension of the story (Emery, 1996). As readers continue to connect and engage with the text, they become invested readers who take control of their own learning (Durham & Raymond, 2016). Furthermore, when students learn a concept through reading this concept transfers to their writing ability making them stronger writers. When authors create strong characters, the story comes alive for the reader. It invites the reader to become part of the story. The Transactional Reader Response theory explores the transaction between the reader, writer, and text (Rosenblatt, 2013). The reader interacts with the text and works to construct knowledge from what they read. In turn, readers bring their own perspectives to their reading based on their background knowledge (Rosenblatt, 1978, 2004; Tracey & Morrow, 2006). Rosenblatt shares that readers can take an efferent or aesthetic stance while reading (2004). The efferent stance encourages the reader to focus on what is to be learned from the text (Rosenblatt, 2019/1994). For example, while students are reading they may be learning about the effects of bullying or about different cultures from their own. The aesthetic stance enables the reader to concentrate on the “lived experiences” (Rosenblatt, 2019/1994, p. 458). These experiences allow the students to immerse fully within the text and connect with the characters. This active engagement with text allows students to control their learning and not be a passive recipient (Durham & Raymond, 2016). To build stronger readers and writers it is important to connect reading and writing. Analyzing strong characters provides students with a model to use in their writing because they are able to use the rich descriptions to develop their own characters. Reading and writing do not work in isolation. Students bridge their literacy lives together by combining all four literacies: reading, writing, listening, and speaking. In addition to bridging the literacies, it is important for students to have authentic literacy experiences (Gambrell, 2015), those experiences that can be transferred into real-world application. For example, writing blogs, creating a podcast, or writing book reviews. These authentic experiences provide meaning to what the students are doing. Our goal as teachers is to create engaged, independent readers, writers, and thinkers. Therefore, it is important for students to be actively involved in analyzing characters through reading and writing because character analysis facilitates students to critically analyze what they read and write.

Implementing Reader Response Activities for Character Analysis

As students’ progress through each grade level, the student expectations for the depth of character analysis increases. This increase in complexity can be seen in the Oklahoma Academic Standards for Language Arts. Students move from a simple description of characters at the knowledge level to analyzing and synthesizing multiple characters. The following reader response activities helped my fifth and sixth grade students develop their character analysis skills, which in turn developed their comprehension, critical thinking skills, and writing. For these activities, I chose to use the story, The True Story of the 3 Little Pigs by John Scieszka. This story is appropriate for all grade levels, but is especially appealing to fifth and sixth grade students, because they can make connections to the original story of The Three Little Pigs. Before teaching this story, I introduced students to point of view, which helped them look at the character from a different perspective. I began the character study by reading the story aloud to the students and then I provided eight classroom copies so that students possess the text to identify textual evidence. I started our character analysis by introducing each of the following three activities using the gradual release model also known as I do it, We do it, You do it together, You do on your own (Fisher & Frey, 2014). The I do it section centers on providing purpose, instruction, and teacher modeling. The lesson then moves into We do it, which shifts to student centered learning, with teacher support, commonly referred to as guided instruction. Next, the You do it together is the collaborative piece where students take what they have learned and apply it (Fisher & Frey, 2014). Finally, the lesson transitioned to You do on your own. During You do on your own students take complete control of their learning and apply the information learned independently. This use of the gradual release model provided students with support prior to independent work. This in turn enabled them to have confidence to dive into character analysis.

Activities to Increase Character Analysis and Response

The three activities I chose were character interview, advice letter, and character trading cards. You can complete the following three activities in any order, but the order shared below enables students to continue to strengthen their analysis and response through each activity. Please note that you may need to stay longer on one activity, until you feel your students are comfortable and ready to move forward. We generally spent one to two class periods working through each activity from the I do it to the You do it together. Then students were able to work the You do on your own during reading and writing workshop time. Finally, we do not want these activities to live in isolation; they are jumping off points to build analysis skills while students are reading their book of choice.

Character Interview We began with character interviews which immersed students in understanding the character’s point of view. You could also create a character panel or a talk show as alternatives to one-to-one character interviews. As a class, we discussed the purpose of interviewing, how to conduct yourself in an interview, such as how to listen, how to take notes, how to respond, and finally I modeled using a character from a previously read book. I was the “character” and the students interviewed me. (I do it)

Next, we divided into partners, one student would pretend to be the character, and the partner was the reporter. The reporter asked the “character” questions using cards with the following questions on each card; (1) If you could choose three words to describe you what would they be and why?, (2) Describe your relationships with others, (3) What problems with other people have you had in your life?, (4) Describe one of your most exciting moments, (5) Describe a time in your life where you have struggled, (6) Describe a moment you were most proud of and explain why, and (7) where do you see yourself in the future? These are guiding questions for the students, but they may also add additional questions. (We do it) When the students finished, they worked together to create a newspaper article using the www.readwritethink.org student interactive, Printing Press. (You do it together) This authentic writing activity motivated students to continue to write newspaper articles that focused on classroom and school events. (You do on your own)

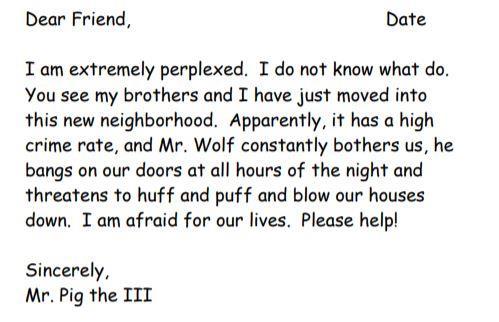

Advice Letter We continued our dive deeper into character analysis, comprehension, and working on advancing writing skills by writing advice letters. Other alternatives could include diary entries, blog posts, Tweets, or a Twitter chat. We began the lesson with the guiding question: What is advice? The students collaborated using think-pair-share about the question. We then discussed as a whole group our thoughts on the definition of advice. After students had a clear definition of advice, I shared a couple of example advice letters. (I do it) After reading the examples, we brainstormed the essential components of an advice letter and mapped it onto an anchor chart. We came up with the following: a salutation such as “Dear” or “Hi,” a thank you or an acknowledgement for writing in for advice, two suggestions for their problem, and a closing such as “Thank you,” “Sincerely,” or “Yours truly,” and “Signature.” (We do it) The students then worked together in small groups to give advice to the Third Little Pig, see Figure 1 for an example of the letter they answered. The groups took turns sharing their letters. (You do it together)

Figure 1. Advice letter

Finally, each student was able to choose a character from either their book of choice or from the True Story of the Three Little Pigs and give them advice. They had to provide textual evidence to support their advice. The students had access to a variety of writers' tools to assist in publication, such as stationery, markers, stickers, computer, etc. Writing advice letters enables students to demonstrate their higher-order thinking skills. (You do on your own)

Character Trading Cards

Finally, we wrapped up our character study with character trading cards, which enabled the students to take everything they learned and apply it to an individual project. (You do on your own) Students used the interactive trading card maker found at www.readwritethink.org to create their own character trading cards. Students considered five categories about their character. They were description (source, appearance, and personality), insights (thoughts and feelings), development (problem, goals, and outcome), memorable interactions (quote, action, interactions), and a personal connection. Please note these categories are from the trading card creator. When students completed their trading cards they printed them and carried them around to share with their classmates.

Closing Thoughts

Analyzing characters through these reader response activities help students think deeper and more meaningfully about character. The stories come alive for them, which in turn builds their comprehension and writing skills. While these activities are centered around one story, they are not meant to remain that way. As students begin to understand the different modes of response they will then have the ability to choose the characters they want to develop further. Ultimately, it is important for students to transfer their learning into their independent reading and writing lives. These activities can be adjusted, so that they will fit into most elementary and secondary classrooms. In essence, the text will drive the complexity of the activities. As students continue to dive into characters they will have a richer understanding of story analysis and writing which will increase their proficiency in literacy.

Dr. Roberta Raymond is an assistant professor at the University of Houston-Clear Lake. She may be reached at Raymond@uhcl.edu

References

Durham, P. & Raymond, R. D. (2016). Building cognitive reading fluency through ‘tagging’ for metacognition. Texas Journal of Literacy Education, 4, 46-56. Emery, D.W. (1996). Helping readers comprehend stories from the characters’ perspectives. The Reading Teacher, 49(7), 534-541. Fisher, D. & Frey, N. (2014). Better Learning Through Structured Teaching: A framework for the gradual release of responsibility, 2 nd ed. Alexandria: ASCD. Gambrell, L. B. (2015). Getting students hooked on the reading habit. The Reading Teacher, 69(3), 259–263. doi: 10.1002/trtr.1423. Graves, D.H. (2005). The centrality of character. In N.L. Roser, M. G. Martinez, J. Yokota, & S. O’Neal (Eds.), What a Character! Character Study as a Guide to Literary Meaning Making in Grades K-8 (pp. 2-5). Newark, DE: International Reading Association. Parsons, L.T. (2013). An examination of fourth graders’ aesthetic engagement with literacy characters. Reading Psychology, 34(1), 1-25. Rosenblatt, L.M. (1978). The reader, the text, the poem: The transactional theory of literacy work. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press. Rosenblatt, L.M. (2004). The transactional theory of reading and writing. In R. B. Ruddell & N.J. Unrau (Eds.), Theoretical models and processes of reading (5 th ed., pp. 1363 –1398). Newark, DE: International Reading Association. Rosenblatt, L.M. (2013). The transactional theory of reading and writing. In D. Alvermann, R. N.J. Unrau, & R. B. Ruddell (Eds.). Theoretical models and processes of reading (6 th ed., pp. 923-956). Newark, DE: International Reading Association. Rosenblatt, L.M. (2019). The transactional theory of reading and writing. In D. Alvermann, R. N.J. Unrau, Sailors, M., & R. B. Ruddell (Eds.). Theoretical models and processes of literacy (7 th ed., pp. 451-477). NY: Routledge. Roser, L.N. & Martinez, M.G. (2005). Why character. In N.L. Roser, M. G. Martinez, J. Yokota, & S. O’Neal (Eds.), What a Character! Character Study as a Guide to Literary Meaning Making in Grades K-8 (preface). Newark, DE: International Reading Association. Scieszka, J. & Smith, L. (1996). The true story of the three little pigs. New York: Puffin Books. Tracey, D. & Morrow, L. (2006). Lenses on reading. New York, NY: Guilford Press.