13 minute read

The Oklahoma Reader V55 N2 Fall 2019

Fall 2019: Finding Hope in the Hard Stuff

Wordsworth writes, “The world is too much with us.” Many of us feel theweight of the world quite tangibly lately. Teachers mayfeel that weight more fullyin our hope to bear it for our students. Perhaps you, like me, seek escape in light stories that offer a giggle or a nice tidy resolution. Our students do need to laugh whentheyread. Theyneed to relish solving a good mystery, marvel at nature, and settle in cozily with families and communities that resonate with love. But they also need to read the hard stuff. We—adult readers and the young people we care for—need to read about the wrong in history. We needbooks that challenge oversimplified and inaccurate societalnarratives often passed down in schools. We need to know war and injustice, loss and struggle. We need to read these stories because, collectively, they hold the hopeful truth that weare capable ofgreat courage, creativity, resilience, that we canspeak up and fightagainst wrong, that hope is stubborn and joy resides in the most marvelously unlikely places. The books featured in this article show individuals finding voice, facing adversity, identifying solutions, fostering community, and furthering justice. The stories they tell span time, space, and culture. They re-infuse the stories we think we know well with truths and voices thathave been silenced or pushed aside. They invite readers to revisit and re-envision persistent narratives that shape the way we view our lives and the world around us. Each book holds power but exploring common themes across texts brings readersto consider more deeply. These books, together, highlight persistence in society—the dread persistence of harm andhate, the dependable buoyancyof joy and hope, and the ever-present possibility of transformation though imagination, strength of conviction, and determined action. They also offer insights into what it takes to change the world for the better. Note that the books offered here include picture books appropriate fora wide range ofreadersas well asbooks aimed more directly at middle to young adult readers. All the books fosterdiscussion about what is and what might be.

Advertisement

They Called Us Enemyby George Takai, Justin Eisinger, Stephen Scott, and Harmony Becker (2019, Top Shelf Productions)

In this graphic novel memoir, well-known actor (Star Trek) and activist George Takai recalls his childhood imprisoned along with his family in an American internment camp. While the horror of losing everything is evident in the portrayal of his parents’ experiences, the reader views the experience through George’s child-view. His innocent acceptance (It’s cool to sleep where the horses slept and tags identifying prisoners are like train tickets) makes the cruel injustice stand out even more starkly. The memoir continues to follow the family’s return to Los Angeles upon release, having lost everything they’d worked for, forced to live on the street, and dealing with pointed racism and the related shame. Takai points to current contexts that frame ethnic groups as enemies, urging us to learn from the past and do better.

D uring World War II, in addition to the internment camps for Japanese-Americans who lived on the West Coast, the U.S. Department of Justice ran internment camps for people, mostly men and most of Japanese, German, or Italian descent, identified as “enemy aliens” accused of colluding with the enemy. The camp in Crystal City, Texas was deemed a family camp, imprisoning the men and their family members who chose to join them there. Haruko is angry with her father who she knows is hiding something and worried about her brother who is serving in the Army. Margot’s pregnant mother fears another miscarriage and her father, frustrated and angry, is being actively courted by Nazi factions in camp. Teens Haruko and Margot meet at the camp. Though vastly different they find connection in their worries, but a prison camp is not a place for teens to grow and these two find themselves changing.

Fred Korematsu Speaks Up by Laurie Atkins, Stan Yogi, and Yutaka Houlette (2017, Heyday)

In 1942, following the bombing of Pearl Harbor, the Korematsu family was rounded up along with more than 100,000 Japanese Americans living on the West Coast of the United States. 23-year-old Fred refused to go and went into hiding. He was found, arrested, and charged with defying government orders. Fred sued. The courts ruled against him, ruling that internment was necessary for national security. Forty years later, though, a historian discovered documents previously hidden from the courts showing that the Japanese-born citizens had not committed any treasonous acts and should not have been imprisoned. Fred’s case was reopened, leading to a 1983 ruling that overturned Fred’s conviction. Fred kept speaking up, leading eventually to the U.S. Government issuing an official apology and providing monetary reparations to every victim of the incarceration. Atkins and Yogi offer a multimodal text, employing poetry, historical explanations, paintings, timelines, and historical photographs to help Fred’s life and message speak to young readers.

Indian No More by Charlene Willing McManis and Traci Sorell (2019, Tu Books)

In the late 1940s and through the 50s, the U.S. government sought to terminate tribes and relocate Indians to urban areas. In this novel based on the childhood experiences of author Charlene Willing McManis, Regina’s Umpqua tribe is terminated. Stripped of their identity and unable to pay the inflated price of their land, the family is forced to move to Los Angeles where Regina’s father is to be trained for a new kind of work through the Indian Relocation Program. Regina and her family struggle to find their way without the support of their community and in a world marked by racism. This earnest and affecting historical fiction work expands our vision of the Civil Rights era by depicting a great injustice little known outside the Indian community.

K athleen Burkinshaw’s mother was four when the atomic bomb dropped on her hometown, Hiroshima, Japan. Burkinshaw’s historical fiction novel The Last Cherry Blossom draws upon those experiences. The novel begins with everyday life. Japan is at war and there, as in the U.S., war efforts influence every aspect of daily life. U.S. planes buzz overhead and sirens sound, sending everyone scrambling for cover. But life goes on for Yuriko. Her widowed father is getting married as is her aunt, mother to her annoyingyounger cousin—and they are all moving in together. Yuriko and her classmates practice protecting themselves with bamboo spears in school, and a favorite jazz record—banned along with other Western products—becomes a secret pleasure. As life changes, Yuriko is also changed when she learns some troubling family secrets. And then the bomb drops. Burkinshaw doesn’t shy away from depicting the horrific effects of the bombing—something readers absolutely need to understand—but there is hope as we witness Yuriko’s determination to survive. Burkinshaw’s additions of radio transcripts, newspaper snippets, and propaganda posters provide additional authenticity.

The Amazing Age of John Roy Lynch by Chris Barton and Don Tate (2015, Eerdmans Books for Young People)

The Civil War happened and slaves were emancipated, right? In much school curriculum, our country’s entrenched racist history may not be mentioned again until the study of the mid-twentieth century Civil Rights Movement. In this piece, Barton and Tate explore the reconstruction period, when the granting of freedoms propelled African Americans forward and incited violent backlash that solidified again the racist structure of our society. John Roy Lynch emerged from slavery to become the first African American speaker of the Mississippi House of Representatives. U.S. Congressman or not, a black man could still find himself barred from certain hotels. But that wasn’t the worst of it—not by far. Back home, white terrorists burned black schools and churches. They armed themselves on Election Day to keep blacks away. They even committed murder. In a way, the Civil War wasn’t really over…. The good people of Mississippi were not outnumbered, but they were outgunned and on their own. Reading and talking about this book should foster important conversations about the persistence of racism and very present struggles related to race and rights.

Ghost Boys by Jewell Parker Rhodes (2019, Little, Brown Books for Young Readers)

Jerome is shot and killed when his toy gun, on loan from his friend Carlos in hopes that it will deter bullies, is mistaken asa real one by a police officer. As a ghost, Jerome witnesses the aftermath of the events that took his life: the grief and struggles of both families and Carlos, court proceedings, and broader effects on the community. He also encounters other “ghost boys”--including, significantly, the ghost of Emmett Till--who seek to stop history from repeating itself. The only living person who can see Jerome and the other ghost boys is Sarah, the daughter of the officer who killed Jerome. Together they try to find a way to heal the suffering and help their loved ones find a way forward. By examining the deadly persistence of racism and the human toll it takes on individuals and society, Rhodes prods readers to consider how we might begin to do better.

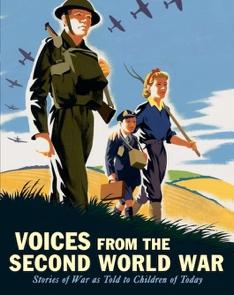

This unique volume is populated with stories of individuals who lived through World War II, many as told to children who interviewed the survivors. Originally published in Britain, an extension of a series in a British children’s newspaper, the book focuses primarily on the European theater but includes stories from Japan and Africa as well. Tales include memories from the perspectives of children, adult civilians, and combatants. One section is devoted entirely to women’s experiences and another to the resistance efforts. From the U.S. perspective, we read an account by the navigator on the Enola Gay juxtaposed with another from a man who was 8-years-old in Hiroshima when the bomb detonated. The book overflows with photographs and other primary source artifacts. Voices from the Second World War is ideal for giving readers young and old an idea of the enormous scope and impact of this war and of the lasting effects any war has on the people who experience it.

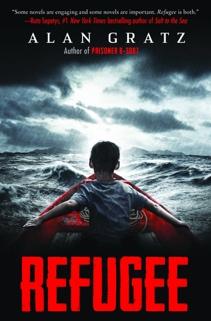

Refugee by Alan Gratz (2017, Scholastic Press)

Alan Gratz tells the harrowing and heart-rending stories of three families in crisis, each fleeing for survival in a different decadebut connected in various ways. Refugee is historical fiction, but the contexts and events are historically accurate. Josef, a Jewish boy, and his family flee Nazi Germany to Cuba in the 1930s. Isabel’s family joins the treacherous exodus of Cubans seeking refuge in the United States in the mid 1990s. Mahmoud’s story brings us to the present as he and his family are on the runafter their homein Syriais destroyed by a missile. Gratz’s young protagonists take the lead in their stories and he doesn’t sugar coat the realities of these treacherous journeys. The result is a gripping experience that brings readers to understand the grim realities of immigration and care about the people affected.

Th e Unwanted: Stories of the Syrian Refugees by Don Brown (2018, HMH Books for Young People)

What happens when war comes and takes away your home? Where do you go? Who will help you and protect you? What will happen to you? When Syria erupted in violence in 2011, refugees flooded out to neighboring countries. Though some were welcomed, the very numbers of desperate seekers overwhelmed the destinations. This drain on resources led to resentment and, fueled by a growing global antiimmigrant rhetoric, even hatred and violence against displaced people. In this affecting graphic novel, Don Brown tells the stories of individual refugees including moments of great trauma and heartrending hope. Just as he did with 9- 11 and Hurricane Katrina, Brown captures the complexity of crisis and the very human toll exacted by violence.

Whether she is creating fantasy worlds or setting her stories in real historical times, Jennifer Nielsen crafts complex, courageous, and captivating characters, placing them in difficult situationswhere they embark on quests filled with suspense and intrigue. Words on Fire is her latest historical fiction, set in 19 th century Lithuania during Russian occupation. Russia sought to crush the culture by outlawing the Lithuanian language and any book written in that language. 12-year-old Audra has become adept at avoiding the Cossack soldiers but when they arrive at her family home, her parents give her a package and tell her to run. Audra’sparents are arrested and their home is burned. Delivering the package leads Audra to discover her parents’ involvement in a smuggling ring bringing books written in the Lithuanian language into the country. Audrajoins the smugglers in this dangerous endeavor in hope of saving her parents and her country.

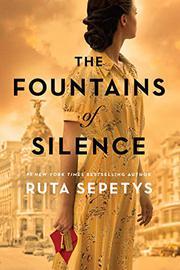

The Fountains of Silence by Ruta Sepetys (2019, Philomel Books)

L ithuanian-American author Sepetys is known for historical novels that bring lost or silenced history into focus. In The Fountains of Silence, she zooms in on the terror resulting from General Francisco Franco’s brutal dictatorshipin mid-19 th Century Spain, and on the broad silencing of his countless victims. Daniel, an aspiring photojournalist and the son of a wealthy Texas oilman, explores his mother’s birth countrywhile his father brokers a business deal. There he meets Ana, a hotel maidassigned to care for Daniel’s family. Her father was killed and mother imprisoned for their part in the resistance, so Ana’s very survival depends on maintaining silence. But Daniel, beginning to noticethe darker sides of the country through his lens, pressures her to tell him more.

Amal Unbound by Aisha Saeed (2018, Nancy Paulsen Books)

A mal wants to know everything there is to know and dreams of becoming a teacher. When, as the oldest daughter, she has to leave school to care for her younger siblings, she holds to those dreams. But when Amal stands up to the son of a wealthy landlord, he retaliates by having his father call in a debtAmal’s father owes. Her father cannot raise the money, so Amal is forced into indentured servitude for the Khan family. Miserable and lonely despite some kindness from her mistress, Amal finds solace in reading poetry she pilfers from the family library and begins to teach the other servants how to read. Ultimately she is befriended by a teacher at a local literacy center who helps Amal discover her own agency and work, with others, toward freedom.

11-year-old Ali is a fan of America. He reads Superman comics, loves watching American TV, and English is his favorite class. But now his hometown of Basra, Iraq, is being bombed by the coalition of forces seeking to stop Suddam Hussain. Ali’s well-to-do Kurdish family is sheltering from bombs, living off rations, and missing his father. The experiences are narrated by Ali, who laments that his beloved America is now going to try to kill him. Ali chronicles the daily changes in his life, including a litany of traumas, from the regrettable loss of his beloved comic book collection (burned for fuel), persistent fearhis father may be dead, and unspeakable terrors such as being forced to watch a public execution. Based on co-author Ali Kadhil’s real-life experiences, Playing Atari with Saddam Hussain narrates the reality of war in a way young readers can grasp, and reminds us of the human toll of a war dubbed in America as “the video game war.”

Suzii Parsons believes that books truly matter in the lives of young people. She is the Jacques Munroe Professor of Reading and Literacy at Oklahoma State University. You can contact Dr. Parsons at sue.parsons@okstate.edu.