Evan Hughes: Chris, this is the second exhibition in Australia and your works have come a long way, they are more complex and narrative has begun to take shape. Where has this energy come from?

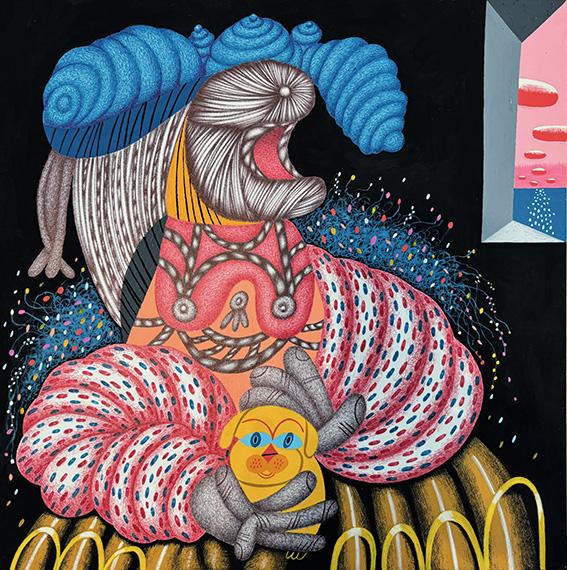

CJ Pyle: The work just goes where it takes me, rather than the other way around. I rarely have any preconceived ideas for an image. I work using an automatic drawing process in the beginning, and slowly the portraits emerge from that method. This body of work is twenty years old now, so more and more visual possibilities have taken shape over time and found their way into the work in a very natural, organic kind of way that adds to the complexity of the portraits.

The pandemic series is almost a standalone body of work, but somehow I have always felt that your figures speak to each other. How does the way a body of work forms for you reflect upon how each of your pieces interact?

The images are definitely in a dialogue with one another. The image that I might be working on at the time is in dialogue with past and future portraits. It might be a curious analogy but I look at the total body of work almost like a school yearbook in the way that the characters all relate to each other in a way, like classmates do, but can be stylistically similar, or stylistically very different, but all have unique personalities that somehow manage to come through.

Tell me a little about how you work and the process each of your characters develop their sense of identity?

I have a small private studio in my backyard behind my home. I usually get started working at about 8AM. I love working in the morning as I feel the most refreshed then. I work for an hour or two and then take a short break for my eyes. I usually repeat that pattern until about 4PM. When I am in the creative process of outlining the images by drawing, I draw and erase over and over again (again, the Automatic method) until I reach the desired conclusion. While I am in this beginning drawing stage I am also subconsciously thinking about the different texture and color choices that I might apply to the image after the outlining stage. Sometimes the images form very quickly, and other times there might be more of a struggle.

Your works are executed on the back of LP record covers. Does your background as a rock and roll drummer have any connection to your method and chosen materials?

It’s a faded memory at this point, but I believe that I was compelled to draw one afternoon on the road and a ballpoint pen and torn LP jacket were what was available. There was always a box of ballpoint pens around because that’s what we made out the bands nightly set list with. It’s all a happy accident really, and certainly not calculated. It just so happens that the pen and that particular paper surface react a certain way and give me the detailed line that I’m looking for. The fact that it relates to my identity as a musician is just a wonderful, random coincidence. Over the years, people have become very interested in what musical artist is on the other side of the drawings and that has become part of the overall work in a humorous way.

Can you tell me a bit about how your identity as a musician and a visual artist coalesced or coexisted? Did you make works on the road?

I started drawing and painting seriously when I was about 10 years old. I actually considered myself a proper artist then. I started seriously playing the drums at around age 13. I was such a natural at it that I became a working professional drummer at 15. I had to be driven to and from my gigs because I couldn’t drive legally yet. I also had to take my breaks in a separate room because of the alcohol laws. I had a sizable reputation as a drummer by the time I graduated High School, so I was offered jobs and went on the road touring immediately. I was home more with a young son in the second half of the 80s, and that’s when I started devoting most of my time to making and studying art. This body of work that I’m known for started to emerge around 2003 and I have been working in this way since then. I still play the drums professionally, but I play mostly because I love the way it makes me feel physically. I’ve never gotten tired of playing the drums, and I feel like my body is in harmony with itself when I’m performing, so mentally it’s a very positive activity for me. And as any artist will tell you, making artwork can be quite meditative as well.

Being completely self-taught, have you found it challenging finding a distinct voice in both the outsider and more traditional art circles?

Actually, it has been a little harder than I expected as far as categorizing the work is concerned. I consider myself a self-taught contemporary artist. A lot of people want to lump me in with the Outsiders because of the “look” that my work has, and others don’t think that that my work belongs in that group at all. I think that the truth lies somewhere in the middle, as the saying goes.

I first got to know your work exhibiting at the Carl Hammer gallery, a legendary Chicago institution in its own right. Clearly there is a connective tissue that draws you together with distinct Imagist artists such as Jim Nutt. Where do you feel your work lies?

I get the comparisons with the Imagist and Hairy Who artists quite frequently. I’m not so much directly influenced by them I don’t think, but we do have a lot of the same influences in common. Mad magazine, Comic books, advertising art, cartoons, and also Hot Rod culture and “lower” forms of artistic expression in general. I’m from the heart of the Midwest just like they are, so sometimes I think that there just must be something in water around here.

You drew my attention to the work of Lee Godie. What influence did her completely introspective but thoroughly public portraits have on your practice?

When I think of a few iconic Chicago artists that I was only slightly aware of until I started working with Carl Hammer, Lee Godie and Christina Ramberg immediately come to mind. I wasn’t necessarily stylistically influenced by Godie, but it was reassuring to me by being aware of her working process that it was perfectly fine to focus on portraiture and all of its variations, which I too was interested in.

You still work as a live musician. How is the American music scene today?

Being a lifelong musician, I could go on for hours on this, but in keeping it short, at the heart of it all, music in America is healthy. You just have to know how to find it. There will always be the corporate driven artists, served up like a McDonald’s hamburger, but there are thousands and thousands of great artists out there writing and performing wonderful music. Some are making state of the art recordings in their own bedrooms and managing to get their music to the public. You just have to research and dig a little bit to find them. The great thing is that music is still very important to most people, which keeps it healthy. I’m paraphrasing here, but a famous philosopher once said, “Life without music would be Gods cruelest joke.”

It is fair to say that work that is intricate and near-abstract in its figurative nature can be devoid of politics. The compelling ugliness of some of your figures however make a viewer wonder if there is a peek into the politics prevailing in the States at the moment. Do you eschew politics and cultural commentary entirely?

My work doesn’t have anything to do with any Washington DC political issues at all. As a matter of fact, my creative process is a way to totally forget about those matters. Politics are the furthest thing from my mind when I’m working in my studio. Cultural issues in regards to my work are a different matter I think. I know a lot of really beautiful people who are ugly and a lot of ugly people who are really beautiful. I think that that point of view might have something to do with my artwork, but politics are really not involved in it.

When we first met in Chicago, America was recovering from the global financial crisis and social bonds were less frayed than they seem to an outsider today. Where do you see America in ten years and how do you envisage your depictions might reflect upon it?

It’s a bad time here in America right now, if I could state the obvious. I’m 67 years old and I’ve been through a lot, but nobody here has ever seen anything quite like this. Family’s divided, friendships dissolved, tense work environments. All because of a sick cult. The USA will survive I think, but the recovery will be a long and hard one. On a lighter note, people looking at my work ten years from now might think, “Man! There must’ve been some crazy shit going on when this guy made these.” And they would be correct.

C J PYLE | FROM THE NECK UP, 2024

C J PYLE

C J PYLE | FROM THE NECK UP, 2024

C J PYLE