FOREWORD 8 INTRODUCTION 14 EPIGRAPH 16

Dogtrot 18 Riverbend 56 RCR 102 Five Shadows 142 Queen’s Lane 182

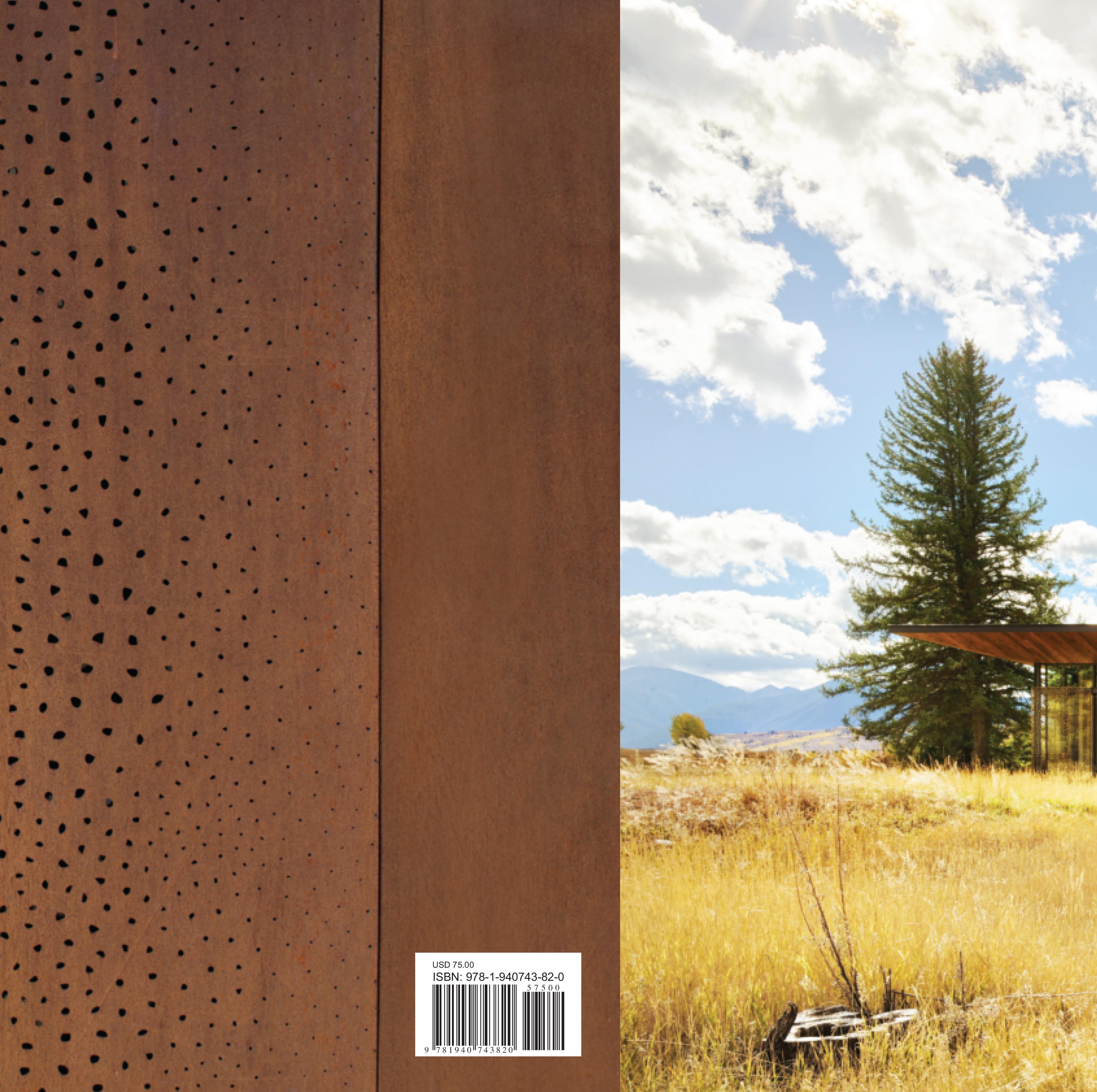

Boulder Retreat 216 Lefty Ranch 252 Lone Pine 286 Crescent H 328 Butte 364 Fishing Cabin 400

APPENDIX 434

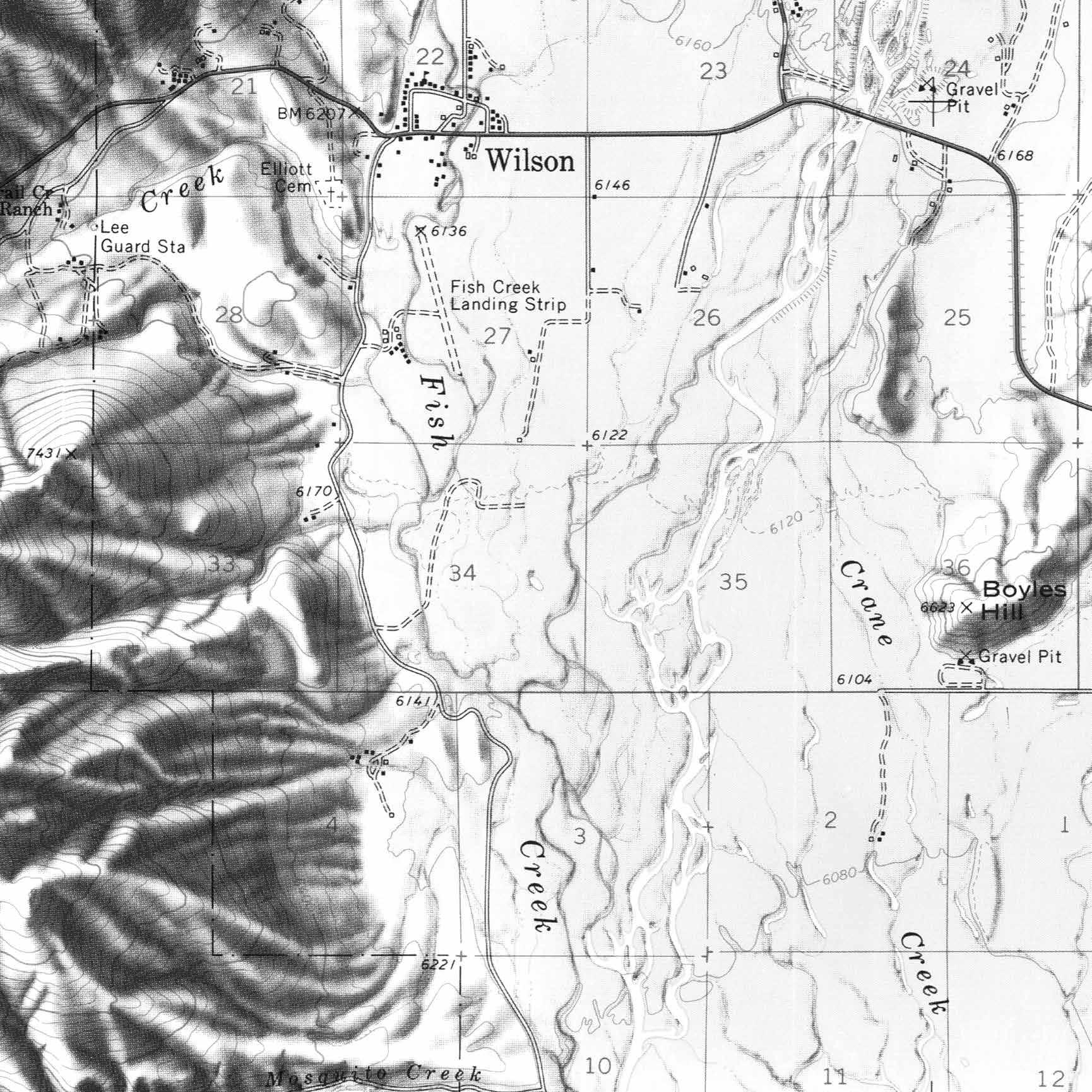

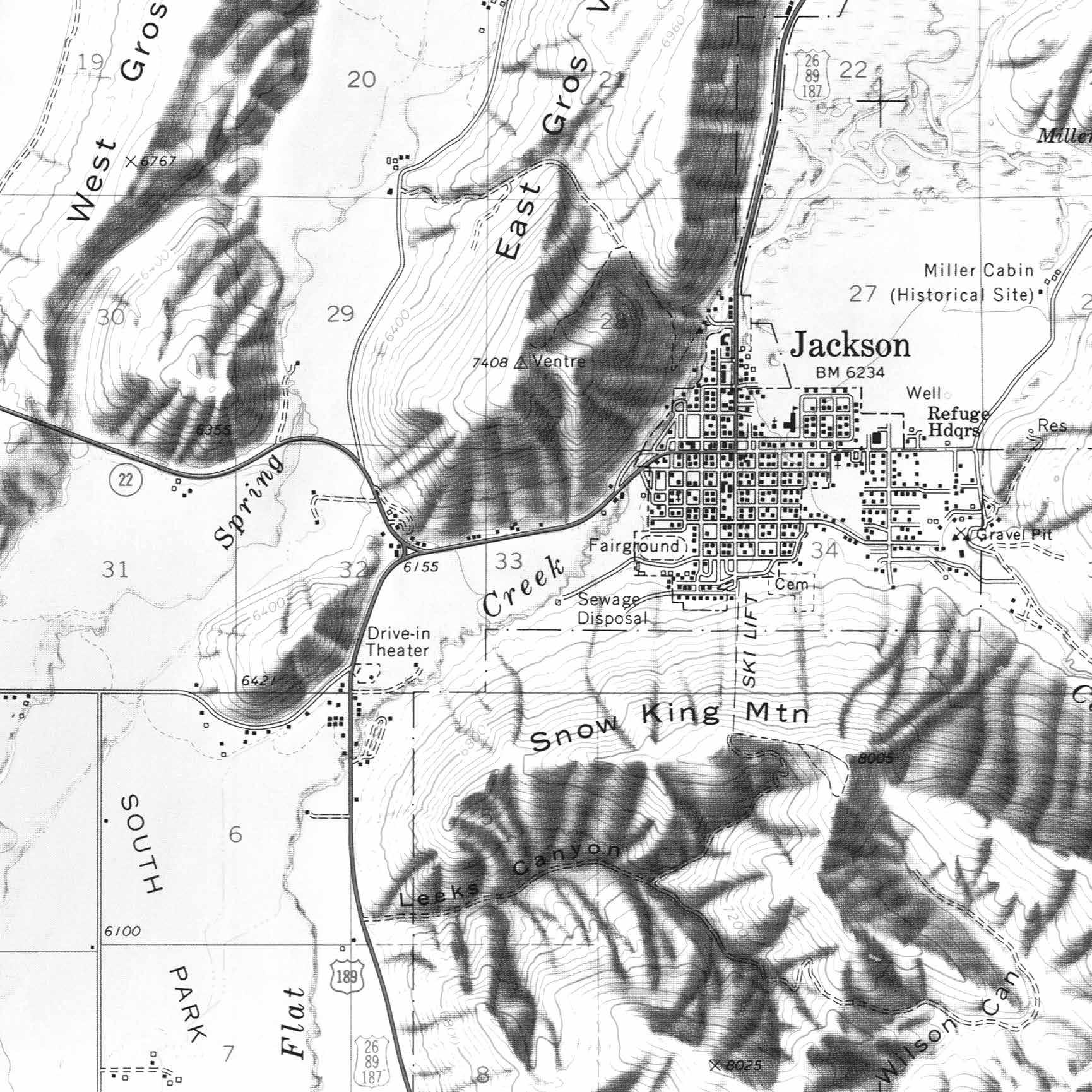

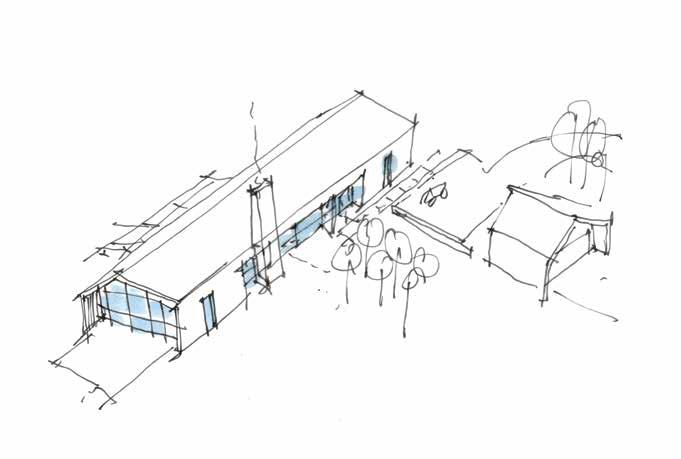

There’s a house at the very northernmost tip of Jackson, right where the grassy basin (or “Hole,” as the old prospectors would have it) dwindles to its narrowest point, sealed up again in the prodigious slopes of the Tetons. Approaching by the last road in the valley, the visitor discovers a clearing in the forest with a pair of raised struc tures, set at a ninety-degree angle and separated by a broad walkway-platform. Clad entirely in fine-grained cedar, with the deck opening at points to make way for live saplings, the place appears—at first—like a miniature monument erected by some unknown woodland tribe: a little Renaissance piazzetta, done over by the Swiss Family Robinson.

On closer inspection, what reveals itself is scarcely less astounding. The main house, the larger of the two, opens into a spacious living room comprising lounging, dining, and kitchen spaces, all of it vaulted over by a double-height ceiling and fronted on both sides by sheer expanses of glass. Out one side, nature and nothing but, the Snake River just beyond the trees; out the other, the guest house and platform, a little beachhead of civilization; inside, a bit of both, organic finishes and fine art, plush seating and custom hardware. Smaller rooms hide behind partitions and under stairways: children’s rooms and work alcoves, a bathroom with salvaged fixtures, narrow passag es that afford a constant and revolving sequence of views outward again to the wooded surrounds. The modality throughout is a kind of sleepy splen dor—luxe, calme et volupté—with a pronounced Western accent. This is a monument, all right, but not to some civic cult or long-dead tyrant. Completed in 2018, the Riverbend House is among the more recent in a series of projects that resemble—when seen as a whole, as in the

present volume—an ongoing experiment in res idential architecture. The technicians conducting this real-life research are Jackson-based firm CLB, and after 28 years in practice they have produced some rather startling results. If Riverbend memo rializes anything, it is a half-neglected conception of the very idea of home, and of the modern designer’s obligation to suffuse it with a special sense of place: to “take something ordinary and elevate it to something extraordinary,” as Samuel Mockbee, founder of the Rural Studio program at Auburn University, put it. While the great rural practitioner’s approach (to say nothing of their particular rural locale) could hardly be more dif ferent, CLB has pursued a similar expansion of the architecturally possible, similarly rooted in nature and in a thorough reexamination of first principles.

It hasn’t always been easy. For all its sce nic splendor, Jackson is also home to a deeply entrenched and deeply conservative local design culture. Or, rather, a lack of one: for while Miami Beach had its Morris Lapidus, the Hamptons its Norman Jaffe, and even Aspen the Bauhaustrained Herbert Bayer, Jackson Hole is peculiar among celebrated American resort towns in having no modernist practitioner of comparable stature to which local architects can appeal. This is partly owing to its somewhat later development; but the consequence is that Jackson’s architecture tends to be more retrograde, more old-fashioned, than that of better-established communities. Amidst a sea of oversized log cabins, CLB has been obliged to make up their own tradition almost ex nihilo, forging (in Kenneth Frampton’s oft-used formula) a new critical regionalism out of whole cloth. Cobbled together from diverse sources—collapsed barns, cast iron tools, auto mobile design—the firm’s regional poetics is the

more remarkable since its criticality has come about almost by accident. In the space of just a few square miles, CLB has somehow opened a small window onto an alternate universe of American design.

No one could have guessed when John and Nancy Carney, now retired from the firm, arrived on the scene in 1992 that northern Wyoming would prove a perfect staging ground for such an ambitious enterprise. Although the influx of the well-heeled was already well in train, it had not reached anything like the stampede it has since become. Local lore has ascribed the “discovery” of Jackson Hole to a 1982 financial conference, whose organizers selected the spot in the belief that it would help lure Fed chairman and known fly-fishing enthusiast Paul Volcker. The gambit worked—though doubtless there were other factors that led to Jackson’s soaring popularity, not the least being its suitability as both a winter and a summer destination, equally ideal for hiking and skiing. By the late ’90s, upscale travelers began to catch on en masse, and with Eric Logan and Kevin Burke already onboard CLB was poised to prosper, turning out everything from ski lodges to parks facilities to, increasingly, exceptional custom homes.

As the younger partners (most recently joined by Andy Ankeny) have matured and forged an ever-tighter collaborative bond, they have contin ued to benefit from the firm’s first-on-the-scene good luck. Every golf club in Phoenix aspires to be the Arizona Biltmore, just as every ranch house in Palm Springs aspires to be the Kaufmann Desert House; in this regard at least, CLB has been bless ed to work out their domestic fantasies without constantly looking over their shoulders to some artificial genius loci. The sense of liberation is pal pable in their recent work—their Dogtrot House,

with its wide-open breezeway connecting parallel flanking volumes, seems to be readying itself for flight; the sports car-ish roofline of Tokala Ranch, on the western side of the valley, might be seconds from speeding off down Highway 191. Even after almost three decades in the area, and dozens of projects in all manner of aesthetic registers, the firm appears to relish the relatively blank slate that is Jackson Hole.

And yet…Echoing in the background of CLB’s oeuvre is a key episode from Jackson’s past. Not just of local interest, it marks one of the great “what-ifs” of architectural history, and its echo has grown only louder as the firm’s work has grown more sophisticated, becoming more and more like a glimpse of what might have been. It seems particularly resonant at the moment—an augur, perhaps, of what might come, both for Jackson and for the place-inspired architecture that CLB has pioneered there.

The Bauhaus was long shuttered, little work was coming in, but Ludwig Mies van der Rohe refused to pull up stakes. In the summer of 1937 a wealthy young architecture enthusiast from America approached the then 51-year-old German architect and asked him to design a Manhattan apartment; Mies refused, telling his eager visitor—whose name was Philip Johnson— that he had pressing business in Berlin. This was a lie, or mostly so: Mies did have one promising offer, though not for a project in Europe. It was from another American, still more affluent than Johnson and dangling a far more appetizing com mission, a guest house on a large country estate. Even as he declared that he was “still a German” and would stay at home, Mies was laying plans to come to the U.S. to see the prospective site, locat ed in far-off Jackson Hole.

Winding through the valley floor, the Snake River Ranch was, and remains, the largest private estate in the area. Then as now, it was the per sonal retreat of the Resor family, whose patriarch Stanley B. had amassed a considerable fortune in advertising and who began frequenting the region in the late 1920s, following friends like the Rockefellers, whose JY Ranch lay just up the road. Also like the Rockefellers, Stanley’s wife Helen was in the circle of New York’s Museum of Art, and had been introduced to Mies through MoMA’s famed director Alfred Barr. When the couple decided to build another structure on their Wyoming prop erty, they first turned to Philip Goodwin—the architect of the museum’s original building—but found his work unsatisfactory. They then solicited Mies to extend an already completed portion of the Goodwin design. In time, Mies would develop a proposal to completely junk the Goodwin wing and produce a house in his then-emerging style, a spare ribbon of glass and steel.

Nothing was ever built—heavy rains came in the spring of 1943, and they swept away what little had been put in place. The clients gave up on the idea, while Mies went on to make considerable hay with his second plan, using the collage-like renderings to secure subsequent commissions like the Farnsworth House. Largely forgotten, however, is his initial design, the extension to Goodwin’s: not yet the austere planar assemblage of the collages, the first proposal was warmer, almost rustic. Partially clad in wood, it launched over a narrow creek bed (the same that would eventually doom the project), leaping it in a single stride. Notably, en route to Wyoming, Mies had stopped in Spring Green, Wisconsin. There, in what was intended as a one-day visit, he spent the better part of a week with Frank Lloyd Wright at

Taliesin, enchanted by the gracious organicism of the hillside house-cum-studio. “Freedom! This is a kingdom,” Mies reportedly declaimed, look ing over the landscape from the lip of Wright’s courtyard. Never again would Mies show a similar affinity for Wright or his work; never again would Wright’s influence be so manifest as in the origi nal Snake River Ranch scheme.

And never again would Mies return to Wyoming—an absence with far-reaching impli cations. Following his Jackson interlude, Mies embarked on the mature phase of this career, the one that set the tone for postwar modernism in American cities, the age of Seagram and Lake Shore Drive. But imagine, just for an instant, that the Resor House had been built, and built more or less according to the original pattern. At a bare minimum, the house would have become a pilgrimage site for young American designers, an invitation no less coveted than one to the Glass House, Philip Johnson’s later Miesian exercise in Connecticut. One could imagine more—that Mies had continued in the same vein, that his admirers had followed suit, built more in the area. What if, instead of the stringent Chicago School, there had grown up under the shadow of the Tetons a dif ferent brand of architecture? A “Jackson School,” espousing a fusion of Bauhausian rigor and Wrightian earthiness? What if it had flourished after the war? What if this, rather than the Mies we know, had become the normative model for the profession, the idyll of the academies, the default style for museums and towers and civic buildings… The “what-ifs” multiply.

Speculation is good fun, of course. But all that is certain is this: the floods deprived Jackson not just of a house, but of a whole potential identity, a formal expression that might have put it on the

modern architecture map. Even as the area grew over the ensuing decades, gradually infiltrating the national consciousness as one of the country’s most glamorous beauty spots, it did so without an endemic design language of its own. There was simply no one there to articulate it, to elaborate it, and refine it. Until, at last, there was.

Forty employees strong, occupying modest but tasteful digs in downtown Jackson, CLB has grown from being a small fish in a small pond to a very large fish in a pond that now extends as far as southern Montana, where they maintain a satel lite office in Bozeman, and further still to Canada and to both coasts, where the office is increasingly making inroads. Change has come as well to the firm’s own hometown, which appears less and less insular with every passing year. Nowadays, Jackson has overrun its banks.

Evident in the firm’s current catalog is a strong impulse to keep pace, projects that have dilated CLB’s professional scope. In Teton Village, the firm completed Caldera House, a project that enfolds high-end residential units within a multi-use complex that includes a boutique hotel and private ski club. The units—large apartments for seasonal guests looking to stay as near as possible to the slopes—are essentially CLB houses in miniature, squeezing the formal excitement of their larger residences into a denser frame. Showing what the designers can do in a quasi-urban context, the apartments also highlight the work of the firm’s in-house interiors team, a burgeoning sector of the practice that is now producing its own furniture for use in other projects.

Also pushing the envelope is Daisy Bush, an affordable condominium development sponsored by the Jackson Hole Community Housing Trust, the city’s primary builder of low-cost housing.

Eight units in all, the project is remarkable for how not-below-market it appears: simple volumes, set at an angle and back a few steps from a quiet suburban street, each structure has ample front as well as rear gardens; inside, each unit affords comfortable living spaces for working families with an economy of space that recalls a Brooklyn brownstone, but with floor-to-ceiling windows, spacious decks shaded by dramatically projecting eaves, and façades sporting CLB’s signature pair ing of wood and metal surfaces. In a nation where hostility to affordable housing is a major hurdle, Daisy Bush is a prime example of how to turn NIMBY into YIMBY.

The firm has even ventured into public art. The latest in a series of installations around Jackson, “Town Enclosure” is situated on a vacant site (one of the few left in the town) opposite the Center for the Arts, and it features large wood slabs—unfinished on one side, charcoal black on the other—arranged in a circular formation on a bed of crushed stone. The piece, formally and functionally, does at least triple duty: as a framing device, it does affectionate homage to Snow King, the nearby mini-mountain and beloved commu nity ski slope; as land art, it creates a moment of hushed sublimity, a timber Stonehenge of mys terious meaning; and as a civic gathering point, it provides a town with few shared amenities a genuinely public space. Hosting exhibitions and performances by local artists, “Town Enclosure” comes very close to the conceptual heart of CLB’s entire practice, an exploration of Heideggerian “place-ness” (Ortschaft) and the mystical connec tion between humans and their environment.

Expanding CLB’s range into such adven turous realms, projects like these have built upon what was already an outsized typological

wheelhouse—Jackson’s airport was co-designed by the office, as was the Center for the Arts itself. The firm’s workshop environment makes its architects particularly well-suited to this kind of work, with all the designers coming together alongside clients and consultants to tackle projects of dizzying complexity. But residential work still remains at the core of the office’s repertoire, and it is there that the firm’s evolution has been the most rapid and the most telling. In an 8,000-square-foot house for a California client, the firm’s technical know-how takes pride of place: sweeping and impressive, the house also contains a mechanical suite of breathtaking complexity and elegance; every finish, every detail has been executed with unrivaled precision, a credit to CLB’s discrim inating choice of (and warm relations with) the local contracting community. At the Five Shadows Residence, the designers were confronted with a peculiar property embedded halfway into a hill side in a densely populated neighborhood; through careful siting, landscaping, and a processional log ic that draws visitors as quickly as possible to the rear of the house, the team succeeded in making it feel as isolated as any house in the area. Logistical and infrastructural challenges like these are only going to become more pressing as Jackson Hole grows increasingly developed. Thus far, CLB seems well ahead of the curve.

Now that the world has caught up with Jackson, the area’s most dynamic architects find themselves at a crucial juncture. With Teton County’s population continuing to grow (more than doubling since the firm was founded), and the seasonal traffic swelling with every passing year (the latest phenomenon: cross-country tour ing buses filled with excited tourists), everybody seems to be beating a path to CLB’s door, and the

designers—ever sensitive to the needs of a diverse client base—are ready to greet them. The proj ects in this book testify that the firm’s approach, incubated in its hometown, has grown sufficiently pliable, their group ethic sufficiently durable, as to render their regionalism (if it even remains that) a highly portable one. Jackson Hole has found its architects, however belatedly, and it would seem only natural that a place with so much global cultural cache should launch an architecture firm with similar reach.

Which also, possibly, has been a long time com ing. Way back on another dusty Wyoming road, past a cluster of old log cabins, one reaches an unruly field of dandelions and swaying cottonwoods. In the middle, in a marshy depression, there stand a pair of solid concrete piers, the indentations from the formworks still visible—all that remains of what would have been Mies’s guest house at the Snake River Ranch. Whether the house, in its ear lier, woodsier iteration, would have catapulted the area to architectural renown will never be known; even if it had, there might never have emerged a viable and identifiable “Jackson School.” On the other hand, it could yet turn out that that tantaliz ing counter-historical prospect was never entirely foreclosed. Maybe, just maybe, it was only delayed.

—Ian Volner

—Ian Volner