I dedicate this book to my mother, Evangelia, who deserves all the credit and my deepest gratitude for guiding, nurturing, and shaping who I am.

And to my family — Sylvia, Tanya and Alexi — for their endurance and support for the person I have become.

FOREWORD by Dan Rosenfeld 9

PROLOGUE 10

CHAPTER ONE | THE BOY FROM ATHENS 13

CHAPTER TWO | LOS ANGELES’ MODERN POLITICAL AND CIVIC ODYSSEY 28

CHAPTER THREE | TRANSPORTATION 90

Funding of the Metro Rail 90

MTA Headquarters and Transit Center 109

Southern California Rapid Transit District 128

Universal City Metro Station 139

MTA and MCA Deal: Compromise or Public Betrayal? 140

The Demise of the East LA Subway 144

Los Angeles 1984 Summer Olympics 148

RTD/MTA Transit Police 153

The Sumitomo Debacle 157

John Dyer 160

CHAPTER FOUR | THE CHALLENGES WE FACE 162

Clean Energy 162

Water 170

CHAPTER FIVE | ARCHITECTURE 185

CHAPTER SIX | HOMELESSNESS 206

CHAPTER SEVEN | PROMOTING THE ARTS 228

CHAPTER EIGHT | THE EDGY NARRATIVE BEHIND THE STORY 253

Oil Drilling at Pacific Palisades 253

Northridge Earthquake 261

East LA Prison Controversy 270

The War Against Smog 275

Los Angeles International Airport 284

Private and Service Clubs 289

CHAPTER NINE | DINING OUT IN LOS ANGELES 299

CHAPTER TEN | OVERSIGHT OF PUBLIC PROJECTS AND AGENCIES 318

The $1.6 Billion White Elephant (I-405 widening) 318

Ribbon of Light (6th Street Viaduct) 324

A Bridge Home 329

The LAPD Administration Building 332

LAC + USC Medical Center 338

Los Angeles Department of Water and Power 339

Lessons Learned 347

Ratepayer Advocate 350

Board of Zoning Appeals 351

CHAPTER ELEVEN | PRESERVING LOS ANGELES HERITAGE 354

Los Angeles City Hall 354

Los Angeles Central Library 359

The Grand Central Market 369

Angels Flight 370

Ambassador Hotel: Robert F. Kennedy Community Schools 376

CHAPTER TWELVE | A NEW DOWNTOWN LOS ANGELES 380

Bunker Hill 380

Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels 385

Civic Center 389

LA Live 395

La Plaza de Cultura y Artes 398

Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) 401

State Office Facilities 406

Staples/Crypto.com Arena 409

Walt Disney Concert Hall 418

Metropolitan Water District Headquarters 430

One Santa Fe 433

James Wood 437

CHAPTER THIRTEEN | INITIATIVES THAT AFFECTED OUR LIVES 439

Transit Oriented Development 439

Linking schools to subway system 445

Greenways 447

Exposition (E) Line 457

Orange (G) Line 460

Benefit Assessment Districts 464

Rail Construction Corporation 467

Transit Industry Jobs Creation Initiative 470

Blue (A) Line alignment decisions 472

Measure R 474

Measure J 478

Measure M 478

Greenline (C) Connection to LAX 482

Los Angeles River 483

CHAPTER FOURTEEN | FINDING BEAUTY AND CREATING IT 495

Steel Cloud 495

Bridge Over 101 Freeway 502

Angels Walk 505

Universal Citywalk 517

CHAPTER FIFTEEN | ASPIRING FOR OFFICE 521

Los Angeles Mayor`s Race, 1993 521

Los Angeles Controller’s Race, 2009 525

CHAPTER SIXTEEN | ASSOCIATION WITH NATIONAL AND WORLD LEADERS 529

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN | THE GREEK CONNECTION 542

Greek American Community 542

Los Angeles — Athens Sister City Affiliation 544

Hellenic American Chamber of Commerce 552

Television and Radio Endeavor 557

Hellenic American Political Action Committee 557

American Hellenic Council 557

Impressive Tactic in Greek Elections 558

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN | OTHER 559

Prop. 187 559

Modest Investments 563

Reconfigure L.A. City Departments’ Roles and Responsibilities 568

EPILOGUE 574

TESTIMONIALS 576

INTERVIEWEES 578

ABBREVIATIONS 580

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 583

INDEX 584

Public buses in Los Angeles, as they head to the center of the city, bear the name “Patsaouras Transit Plaza” above their windshields.

Who is Patsaouras? What has he done to merit the honor?

The buses’ destination is not “Union Station,” “Civic Center,” nor “Downtown,” but rather the legacy of Nikolas Patsaouras—who journeyed from Athens, Greece, as a young man—an engineer, civic visionary, and resolute aspirant for the public good.

This is Nick’s story. But it is more than that. In addition to his unvarnished recollections as a formidable force in the evolution of Los Angeles, Nick has interviewed many contemporary civic leaders. It is their combined stories, in their own, often unedited, unembellished words, that, together, chronicle the legacy of Nick Patsaouras. It is a story that every Angeleno should know.

Nick is rational. In the long Greek tradition, Nick applies an engineer’s methodical logic to the complex challenges of a major city.

Nick is blunt. The candor in this narrative is unusual in memoirs; no punches are pulled. Nick is nothing if not opinionated—once, now, and always.

Nick was there. In the transformation of Los Angeles from a sleepy agglomeration of suburbs into one of the world’s greatest cities, Nick Patsaouras was at the center, often behind the scenes but never quietly, in politics (a Greek word if ever there was one), land use planning, transportation, the 1984 Olympics, the downtown renaissance, arts and music, culinary primacy, and more, at each step of the way. Especially in a city that prides itself on mobility— upward social mobility, fast-moving freeways, open-ended opportunities—the man at the hub of the transit system saw it all.

With the precision of Pythagoras, the persistence of Demosthenes, and the declamation of Pericles, this is Nick’s story.

So, απολαύστε το ταξίδι! Enjoy the journey!

—Dan Rosenfeld

I wrote this book because I have useful insights and observations to present that I hope will benefit the city I love. I am not a historian and this book is not a history.

It is a book that chronicles the fifty-year political and civic odyssey of modern Los Angeles from the viewpoints of major political, cultural, academic, and business leaders as well as my own. I personally gathered valuable information regarding the making of modern Los Angeles that I want to share with present and future leaders.

As I wrote the book, I knew how blessed I have been throughout my life. I came to Los Angeles at age seventeen, dedicated to schooling, and who then achieved a successful career in electrical engineering. The American dream never entered my mind. The American promise had occupied that space, the notion that hard work and worthy pursuits yielded fitting results. In turn, I promised America repayment through robust public service.

Public service was inculcated in my mind since my high school days when we were taught philosophy and political theory. We learned that in ancient Greece a person who did not get involved in civic affairs was defined as private (idiotis). The Greek historian Thucydides wrote, “We are the only ones who, whoever does not participate in political ‘commons,’ we do not consider to be idle, peaceful, but useless citizens.” With the passage of time, the word idiot came to be synonymous with the word dumb.

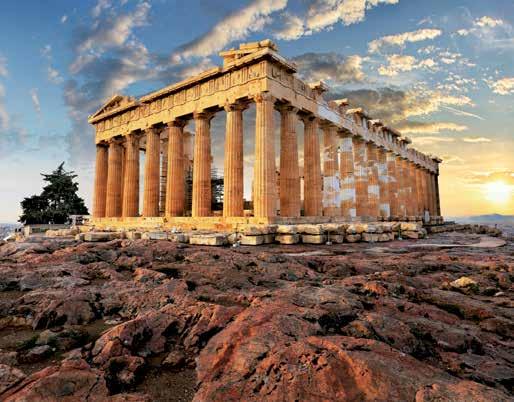

“It can be argued,” historian Kevin Starr wrote in 2003, “that few cities in the history of the human race have embarked upon a comparably ambitious program of public and private works. The building of the Acropolis in Athens, the redesign and reconstruction of Rome, the rebuilding of London after the fire of 1666, the high-rises and subways system of Manhattan as they emerged in the first three decades of the twentieth century—all these projects are in the league in which Los Angeles now finds itself.” I was blessed to be involved directly or indirectly in this “ambitious program.”

By plunging into the enigmatic political, civic, and cultural life of my adopted metropolitan area, I directly influenced a number of events, such as helping secure funding for the Los Angeles Metro Rail, thus catapulting the city into world prominence.

For half a century I was fortunate to befriend mayors, governors, presidential candidates, and presidents, and I helped deliver benefits to the public as a member of the transportation and water and power agencies. En route, I gathered captivating and intriguing details of crucial decisions often made for the benefit of private interests and not for public service.

Fifteen years ago, I decided to write a book on my experiences. I interviewed more than two hundred key individuals from the political, business, academic, and cultural fields who

shaped the city, and with whom I had genuine relationships. The conversations were candid, informative, and insightful.

I witnessed and participated in the development of Los Angeles as a world-class city. The picture-perfect city skyline did not mushroom without flawed backroom deals, and I describe some of them.

In this book I cover political intrigue, the Northridge earthquake, the renaissance of the rail system led by Mayors Tom Bradley, Antonio Villaraigosa, and Eric Garcetti, each with his own plan.

I describe in detail how the courageous stands of certain individuals preserved the city’s heritage, the battles waged by the Los Angeles Conservancy, the creativity of architect Brenda Levin, the persistence and perseverance of preservationist John Welborne, the ingenuity of developer and civic leader Nelson Rising, and the leadership of ARCO Chairman Lodwrick Cook.

I chronicle the vision and the efforts of Lewis MacAdams, my friend and founder of Friends of Los Angeles River, and of Melanie Winter and Dan Rosenfeld to revitalize the Los Angeles River.

Insights from cultural leaders on the arts in Los Angeles are detailed.

The smog saga and related conspiracy of the auto industry is explained.

I point out how shortsightedness and political selfishness squandered an opportunity to create a public space in Los Angeles like Trafalgar Square in London, Red Square in Moscow, Tiananmen Square in Beijing, Union Square in San Francisco, or the Pnyx in ancient Athens.

I describe the controversies and the personal blame-game that took place in the initial planning and designing of a dazzling landmark, the Walt Disney Concert Hall.

I explain how I watched homelessness become an existential crisis because our city and county leaders ignored it over the last thirty years and are now spending billions of dollars with very little tangible results, and I describe how we evolved into “The Homeless Industrial Complex.”

I delve into the legendary Gloria Molina’s battles as the first Latina to rise to the pinnacle of local politics, her crusade to build the Los Angeles County and University of Southern California Medical Center (LAC + USC Medical Center), her leadership to scuttle Governor George Deukmejian’s efforts to build a prison in slighted East Los Angeles, how she tried unsuccessfully amid political infighting and corruption to prevent the demise of the Eastside subway, her vision in establishing La Plaza de Cultura y Artes, and her determination to make the Gloria Molina Grand Park a reality.

I cover from my own personal experience a serious public betrayal that was staged by a governmental agency and a media conglomerate.

In addition, little-known facts are explained, such as the controversy over the Olympic flame. My personal participation helped diffuse the dispute between the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics Committee and the citizens of Olympia, Greece.

Also depicted is my over forty-year support of minorities and women’s rights in private and public arenas and in government. How I vigorously worked to expand greenspace and promote the arts and led the efforts early on for cleaner energy in Los Angeles. I also define

how my demand for accountability to taxpayers during my presidency of the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power board and through my authoring of “Ratepayer Advocate” yielded positive results.

I wrote this book to inspire, inform, and challenge the reader to get involved in public service. I sincerely hope I will succeed.

As you set out for Ithaka hope your road is a long one, full of adventure, full of discovery. Laistrygonians, Cyclops, angry Poseidon-don`t be afraid of them: you`ll never find things like that on your way as long as you keep your thoughts raised high, as long as a rare excitement stirs your spirit and your body.

Laistrygonians, Cyclops, wild Poseidon- you won`t encounter them unless your soul sets them up in front of you.

—constantine p. cavafy

The renowned Greek poet Constantine Cavafy encourages us to enjoy the journey to our Ithaka rather than rush toward the end. The journey is more important, exciting and pleasant than any arrival at a final destination.

The poem Ithaka seems to speak to Odysseus, the hero of Homer`s epic poem, the Odyssey, during the return to his homeland, the legendary Greek island, but Cavafy speaks to us, too. We have the responsibility to travel to Ithaka in our own lives, for self -discovery, exploration and growth.

Consumed in our daily lives by easy and quick gratifications, we tend to forget that the journey is not only a path where we can gain knowledge, wisdom, and abundant new experiences, but it is also pleasurable and fulfilling. Cavafy reminds us that the reward lies not in reaching our goals but in becoming who we are. Throughout my life’s journey, I had to fight my own Laistrygonians, Cyclops, and angry Poseidons, and, as a result, I believe I came through it all a stronger and wiser person.

The Nazis patrolled the street of Athens when I was born on December 4, 1943. Italians invaded Greece on October 28, 1940, but the Greeks pushed the Italians back into Albania. Germans then occupied Greece in 1941. During the occupation by the Axis powers from 1941–1944, an estimated 300,000 people died of starvation in Greece, at that time a country of about 7 million. Greece had a solid resistance movement. The Allies began to liberate France and other parts of Europe, including Greece, in 1944. While World War II was over by 1945, the conflicts between Communists and the West that marked the beginning of the Cold War began to play out in the Greek Civil War, with confrontations that began in 1944 and then infighting from 1946–1949, which left Greece in more ruin than during World War II. The nation’s food supply had quickly collapsed, and tangible misery affected everyone. Each day was a challenge for poor families like mine.

The house where I was born was a single room that served as kitchen, study, and sleeping quarters. My living room was the unpaved street where I spent most of the time when not in school. We had neither electricity nor running water. Every morning we fetched water from a cold-water faucet in a common yard that also served three other families. Our morning cleansing was a quick splash on our faces.

The song Words of Grievance (“Paraponemena logia”) sung by George Dalaras, describes the surroundings of my childhood (“At the desks of need and in the school of poverty we learned the society…”) It is a song that I love to do the zeibekiko dance whenever I have a chance.

Christmas gifts were clothes, shoes, and books. It was rare when I could afford to rent a bicycle for ten minutes.

My neighborhood, Votanikos, was named for a large botanical garden nearby, less than a fifteen-minute drive from the Old Royal Palace and seat of the Hellenic Parliament in Athens’ City Center. But we were worlds apart. Truly, like they say, we lived on “the wrong side of the tracks,” in poverty’s deep pocket. Still, our toughness became legendary. Our neighborhood’s mangas—a Greek word that characterizes a tough but honest guy from a poor family, loved by women and idolized by friends—was celebrated in songs. Some phrases and tunes constantly resonate in my mind: “A mangas at Votanikos. He tells what he wants without fear…”

I am the oldest of three children, with a sister, Sevi, two years younger, now a retired banker, and a brother George, four years younger, now deceased. In his teen years, George

professional electrical engineer in Southern California and the youngest to serve as president of the Association of Consulting Electrical Engineers in Southern California. The lesson here is that an individual, often a teacher, can set the course of a life, just as former Los Angeles Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa remembers how his high school teacher, Herman Katz, changed his life.

In those early days I remember nights I would cry when I considered how long four years of schooling were, before graduation and my return to Greece. Even now, when I hear the song, “I wander like an exile” (San apokliros gyrizo) sung by Sotiria Bellou, one of most famous Greek singers of rebetika (Greek blues), tears swell up in my eyes. It is, if not the most, one of the most popular songs with Greeks who left the motherland.

I wander like an exile, in this hostile foreign land— strolling, miserable, far from my mother’s embrace.

…

And I cry too, my dear mother, for you, for I haven’t seen you in years.

I can only imagine my mother’s pain for not hearing my voice or seeing me for ten years. I really had no social life growing up in Greece. I left in 1961, and television did not arrive until 1966. We could not afford to go to the movies. But there was one outdoor movie screen, Lais, on a second floor in the neighborhood, and we would look up from the ground floor to see pictures move but we did not know what the story was about. By the time I finished college I had seen very few movies. Looking back, I believe I was emotionally challenged to deal with so many accumulated obstacles: away from family, no language, speaking little English, having no friends and coping with a demanding program. My days in college were not happy. An exhaustive schedule prevented me from spending time in the library or the cafeteria to socialize. I would work full-time, initially as a draftsman and two years later as an electrical designer, while being a full-time student. By law, as a foreign student I had to take twelve and a half units. At night after work, I studied with my dictionary.

My daily routine had me take the bus early in the morning for my 8:00 a.m. class. After three consecutive courses, I caught the 10:50 a.m. bus to work. At 5:00 p.m., I was back on the bus returning to the university until 9:00 p.m. The bus then took me home where I studied for two or three hours, grabbed three to four hours of sleep, then got up again at 5:00 a.m. to continue my studies before catching the bus back to school for my morning class. I worked five days a week from noon to 5:00 p.m., and all-day Saturday. Sundays were set aside to catch up with my reading and my laboratory work. In college, I befriended another foreign student, an Israeli named Ernest Amster, who owned a car. When he could, he would drive me to the office, he was kind of my older brother. We would study together on Sundays.

I did not learn to drive until I bought a used car during my last year at San Fernando Valley State College, now California State University, Northridge, where I received my Bachelor of Science degree. Sometimes, I assess life’s paradoxes and smile. As a student I depended solely on the bus for school and work. A few years later I was the president of the Southern California Rapid Transit District board of directors, the governing body of the public transportation agency.

Here a note of personal gratitude is in order. I want to express my appreciation to the people of California, because my education at that time was almost free. Tuition at junior college was about $6, and the cost of books was only $15 a semester. At Valley State College, the tuition was $60 a semester, and the cost of books was only $50 or $60. Without these very low costs, I would not have been able to finish my education. I could not wait until I graduated. During the last year, I counted the days and eventually the hours when I would finally earn my Bachelor of Science degree.

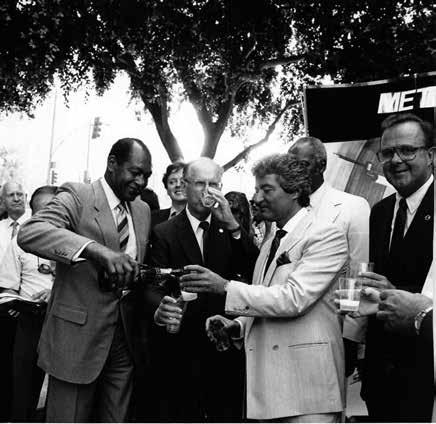

With Supervisor Kenneth Hahn. Photo: courtesy of Metro

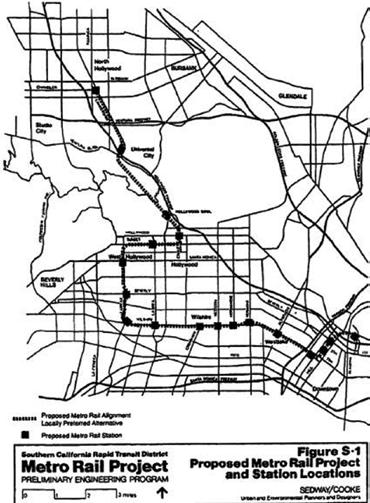

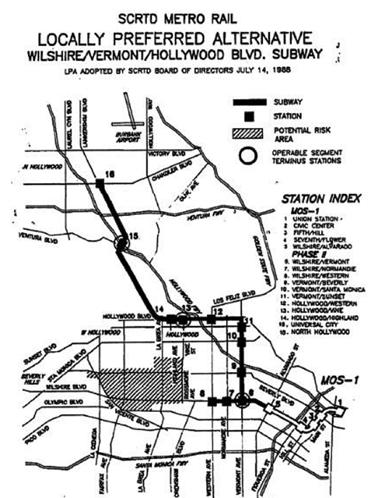

projects in the County. The Wilshire subway would be the project’s backbone. Supervisor Hahn used the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission (LACTC) that California Assemblyman Walter Ingalls, then Chairman of the Assembly Transportation Committee had established in 1976, to place Proposition A on the ballot.

In July 1981, the Southern California Rapid Transit District (RTD) awarded $6 million worth of contracts for engineering of the first segment of the Metro Rail starter line. The following year an additional $42 million was approved for continued engineering.

With the adoption of route and station locations by the RTD in 1982, strong opposition was voiced by numerous groups, chief among them the Hancock Park Homeowners Association. They were alarmed about prompting gentrification where land values increased and long-time residents priced out. More realistically, they feared an influx of new residents that could change the character of their community, and they feared the potential for crime by subway riders. The Westside Civic Federation, an alliance of homeowner and community groups, said it opposed both elevated and subway routes on Wilshire through the Fairfax area.

Behind the expressed opposition lurked racial motives and the fear that minorities would ride the trains “to come and steal televisions.” Renowned actor George Takei, an RTD board member and Hancock Park resident, said “low-income people” were unwelcome by the residents, and they “didn’t want those people.” Even Senator David Roberti acknowledged that area residents “didn’t want working people stopping here.” When asked if this referred to blacks, he replied, “I think so.” The Hancock Park homeowners and the Wilshire Homeowners Alliance, collectively known as “Rapid Transit Advocates” (RTA), filed a lawsuit against RTD on January 18, 1985, on the narrow issue of whether Appellants RTA had a standing to argue that RTD had violated the Urban Mass Transportation Act. The Federal 9th Circuit Court of Appeals found that RTA did not have standing and the case was dismissed.

On September 23, 1986, on an appeal brought by RTA, the California Appellate Court held that there was no requirement that the RTD’s proposed rail project be consistent with the general development plans of counties and cities. The South Brookside Homeowners Association, another opponent of the subway, noted it was unable “to accept what appears to be an unwarranted assault on our neighborhood.” Likewise, the Boulevard Heights Homeowners Association claimed that a subway station at Crenshaw “would destroy the surrounding neighborhoods.” Curiously, the City of Beverly Hills opposed the subway because it would result in an “alien invasion.”

Original Red Line route with a Hollywood Bowl Station. Courtesy of Metro

Built Red Line without Hollywood Bowl Station. Courtesy Metro

Arch project opponent, influential Congressman Henry Waxman from the Westside, had said the key first phase of the proposed Los Angeles Metro Rail system is too risky to construct as a subway and had called on the Los Angeles City Council and the RTD to abandon that part of the project. Reporter Ryan Reft, writing about the Los Angeles Subway in Topics of Meta, on January 28, 2015, said the Fairfax situation differed from Hancock Park. “Home to a long-standing Jewish population dating back to just after World War II, residents worried about rising property values and rents negatively afflicting the neighborhood’s aging residents.” He quoted then subway opponent Los Angeles City Council Member Zev Yaroslavsky, an ally of Congressman Waxman: “Henry and I were both elected seven years apart…and we were elected by the same constituency of old Jewish mothers who are important to us both culturally and politically.” Roberti concurred, “It would pretty much destroy an ethnic community that was long established in Los Angeles. If your constituents don’t want thousands of commuters coming in, there’s not a politician in the world who is not going to respond to that, okay?”

Following a protracted period of bickering among community groups, business heads, and elected officials, the RTD proposed to replace the subway in Hollywood with an aboveground line. The trains would run on Sunset Boulevard through the heart of Hollywood and on Wilshire Boulevard into the Fairfax District but deferred until December 1988 a decision on whether to build below or above ground on Wilshire Boulevard. Despite its attempt to balance the interests of all parties, the RTD came under vigorous attack by homeowners and

Funding for the first 4.4 mile starting line totaled $1,167,600 broken down as follows: (in millions) UMTA, $176; Federal gas tax, $428; Federal funds for construction, $10.6; State of California, $213; LACTC, $176; Los Angeles City, $34; Private Sector (Benefit Assessment Districts), $130.

Waxman, however, once again in August 1986 tried to sidetrack Metro Rail with a surprise amendment in the House, saying that he didn’t act sooner “because I thought the Reagan Administration would stop it.” But when Secretary Dole agreed to a funding package on July 11, he tried to block it in the House Rules Committee. When that failed, he introduced his surprise amendment that was meant to stop Federal money for the subway until a new Environmental Impact Report was completed. As reported by the Los Angeles Herald Examiner, I remobilized and sought to defeat the amendment in its second hearing in the House.

In September Waxman admitted he struck a deal with me to support Metro Rail but told reporter Linda Breakstone that his position “evolved to one of distrust for the entire project.” He claimed that he lost confidence with RTD planners because “they used political considerations instead of safety, technical, or practical reasons” in designing Metro Rail. He did not act earlier because he believed the project would never be approved.

The deal struck with me was threefold: RTD would not tunnel through Fairfax, a technical committee would evaluate the 4.4 miles of the 18.6-mile system, and a safety study would be completed for the rest of the proposed route. All commitments made by the RTD were carried out.

Metro Rail Groundbreaking, with Chris Stewart, Kenneth Hahn, Tom Bradley, Nate Holden, and Gilbert Lindsay. Photo: courtesy of Metro

SCRTD-Metro Rail Groundbreaking, 9/29/1986. Photo: courtesy of Metro

Congressional Representative Ed Roybal inserted a new twist to Waxman’s actions, stating that “if he doesn’t want it in his district, we ought to look at putting it in East Los Angeles where most of the people live, where jobs are needed, and where they really need transportation.” Waxman’s efforts failed.

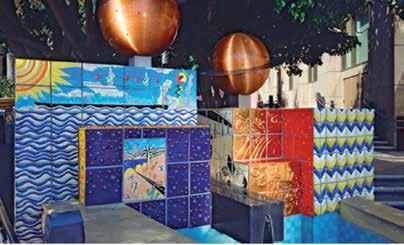

were selected. Michael Amescua adapted the Latin American craft of paper cutouts into the medium metal for the “Guardians of the Track,” elegant, patterned metal fences, guardrails, and wall motifs decorating the Plaza. The bus shelters are etched glass and ribbed wings and vine-like structures, metal work so complex that an out-of-state firm that builds roller coasters was used.

The pedestrian connection between the Plaza and the intersection of Cesar Chavez Avenue and Vignes Street was originally a Spartan design with limited enhancements, an oversight remedied by then City Councilman Richard Alatorre. The Councilman requested more prominent and striking improvements along the pathway. Three tiled fountains by Roberto Gil de Montes, Elsa Flores, and Peter Shire now decorate the passageway, creating a mini park experience, affectionately referred to as “Alatorre Park.” It is one of the most traveled corridors in the Gateway complex. Inside the building, at the entrance to the cafeteria, Margaret Nielsen’s panoramas of memory are captured in postcards from Los Angeles past, the glamorous 1930s and 1940s.

Patrick Nagatani’s mural collage “Epoch” at the boardroom entrance, a series of 1887 photographs by photo pioneer Eadweard Muybridge, that show a naked man in motion drew complaints and was covered. Some workers were shocked, others were amused. At the man’s feet are postcard images of trolleys, trains, and antiquated modes of transportation. Around him are NASA photographs of space. National TV stations and media covered the

Fountain at Richard Alatorre Park/ Paseo Cesar Chavez. Artists: Elsa Flores, Peter Shire, Roberto Gil de Montes. Courtesy of Metro

controversy. I told the media, “Personally, my view is that the Sistine Chapel has ten times more nudity than this. Art should provoke debate.” The ACLU of Southern California sent a letter condemning the covering of the mural as censorship and an “unconstitutional abridgement of free speech under the 1st Amendment.” Eventually the curtain was removed, eliciting applause from dozens of employees.

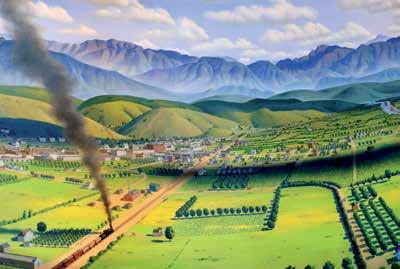

In the lobby of the building, visitors can admire James Doolin’s bird’s-eye-view murals. Visions of Los Angeles transportation are used as a device to cut through time and space from “Circa 1870,” where a train moves toward a new century, to “Circa 1910,” a city falling in love with cars, to “Circa 1960,” a sprawling smog covered metropolis, and “Circa 2000,” a mural at the third floor that envisions a city of the future with the MTA building and the Hollywood sign clearly seen.

Then Assembly Speaker Antonio Villaraigosa said he had been concerned about the agency’s commitment to building a heavy rail system. “There is no question in my mind that heavy rail is not the best investment of our precious transit resources. Light rail, busways, and improved bus service are a better solution to the area’s transportation needs.”

In November 1998, Los Angeles County voters approved Proposition A, the MTA Reform and Accountability Act that was sponsored by Yaroslavsky, and barred the use of county sales tax money for all future subway projects. That was the final nail in the Eastside subway’s coffin. The Westside killed the Eastside subway.

However, Molina was determined to bring a rail line to East Los Angeles. She worked with the Eastside congressional representatives and especially Lucille Roybal-Allard to salvage the funds that had been designated for the aborted subway. The six-mile Light Rail Line from Union Station to Atlantic Boulevard in unincorporated East Los Angeles opened in November 2009. In recognition of these efforts, the Metro board voted in March 2023 to name the East Los Angeles Civic Center Station, Gloria Molina Station.

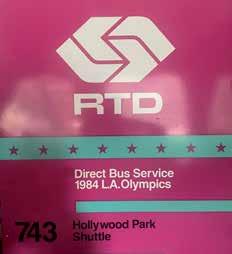

The Traffic Nightmare that Wasn’t | The 1984 Summer Olympics (officially the Games of the XXIII Olympiad) were held from July 28 to August 12, 1984, in Los Angeles, California. In the mid-1970s, only two cities made serious bids for the 1984 summer games, Los Angeles and Tehran, Iran. Tehran withdrew its bid in June 1977 as the Iranian Revolution erupted.

Announcing the RTD Olympic Service Plan: With Mayor Tom Bradley. Photo: courtesy of Metro

RTD bus stop sign, the colors of the 1984 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles.

That left Los Angeles’s bid and it was accepted by the International Olympic Committee. The official announcement was made in Athens, Greece on May 18, 1978.

In March 1984, a spat developed between the Los Angeles Olympic Organizing Committee and the Hellenic Olympic Committee. Peter Ueberroth, LAOOC president, made an announcement that, “The problem with Greek officials—who objected to using the Olympic flame to raise money—was only ‘a misunderstanding’ and had been clarified to the satisfaction of both parties.” He also said $3,000 contributions for those wanting to sponsor one kilometer of the run would be accepted through April 10, 1984.

Mayor Tom Bradley, while in Athens, in early February 1984 during his trip to Greece to establish the LA–Athens Sister City affiliation, explained to the Greeks that “the commercialization of the torch” was a misunderstanding, because the funds would be used for philanthropic purposes. Bradley participated in a meeting with the International and Hellenic Olympic Committee to “resolve the misunderstanding.” The HOC issued an angry statement seeking an explanation to Ueberroth’s comments. In a telex sent to the HOC, LAOOC declared that it had stopped accepting new contributions. The Greeks, led by Spyros Fotinos, the mayor of the city of Olympia, objected to the commercialization of the New York–Los Angeles Olympic Torch relay (see Los Angeles–Athens Sister City section).

The Olympic flame, carried by a torch, is lit several months before the Games at Olympia, the birthplace of the Olympics, where the Ancient Olympic Games took place. The flame is lit by a holy priestess using the sun’s rays and a parabolic mirror. The 1984 Summer Olympic torch relay began in New York City and ended at Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum, crossing thirty-three states and the District of Columbia. I was proud to sponsor my daughter Tanya so she could be a participant, running with the Olympic torch for a short distance in Los Angeles. Rafer Johnson, winner of the decathlon gold medal at the 1960 Summer Olympics,

CHAPTER SEVEN

Art washes away from the soul the dust of everyday life.

The most perfect structure ever built, the Parthenon, stimulated my love for art and beauty. As a young boy living adjacent to this acclaimed monument, I was inspired by the ingenuity of the ancient builders and artists. Frequent visits broadened my sense of art and enhanced my admiration for the brilliance of the carved marble under the blue Athenian sky, the flawlessness of the physical beauty, and the satisfaction it conveyed to the mind and the eye. The sculptures seemed alive, the temples flawless, the environment preserved. A motivating equilibrium prevailed.

Years later, when visiting my son Alexi, who was studying philosophy at Oxford, I was disheartened when I saw the Parthenon Marbles at the British Museum—sculptures violently hacked by Lord Elgin and carried off to London in 1801 in what the Guardian reported as “a blatant act of serial theft.” Greece’s decades-long campaign for the antiquities’ reunification has been reinvigorated, an undertaking I strongly supported. My father also played a central role in expanding my exposure to the arts. At an early age, I was frequently taken to the Athens Symphony and museums.

This love and understanding of the arts and their influence on society convinced me to pursue programs that make art accessible to all. As Dr. Seuss, the children’s author, said, “Be who you are and say what you feel because those who mind don’t matter and those who matter don’t mind.” In 1984, as President of the Southern California Rapid Transit District, with the support of fellow director George Takei, I convinced a reluctant board of directors to require half a percent of the cost of a subway station structure to be allocated to the “Artsin-Transit” program.

Consequently, artwork in various media—painting, sculptures, engravings, murals, holograms—are among the art form types found in the Los Angeles subway, light rail, and busway stations today. In addition, coveting even greater artistic impacts, computers, rotating art displays, stained glass and sound-and-light presentations have been utilized. More than 1,000 artists have already added their talents to this program, and their number is growing as new rail lines are added to the system. Among them is Frank Romero, a pioneer of the Chicano art movement. Romero painted Going to the 1984 Olympics, owned by Jim and

Regarding the Geffen Contemporary, Nicholas confided to me that he hired Gehry to design the architecture for two warehouses. So good was the project that people liked it better than the regular MOCA, added Nicholas.

For almost a decade Danielle Brazell persistently nudged City Hall to support the Los Angeles nonprofit art scene. In 2014, she was appointed by Mayor Eric Garcetti to head the Department of Cultural Affairs, the progressive arts and cultural agency of the city which supports and provides access to visual, literary, musical, performing, and educational arts programs. Further, the DCA makes funds available to arts organizations and individual artists. Brazell explained why she felt the arts were so important in Los Angeles. “It connects the city and the people to the past. The city is incredibly dynamic, constantly evolving.” “This is a global city.

We are an exemplary manifestation of cultural diversity. There is no shortage of commitment from our intra-agencies, there is no shortage of commitment from our artists,” she added. She praised the efforts of other city departments and pointed to the Metro in the Arts program.

“What we lack is support for noncommercial creative production, affordable live-work space for artists,” she summarized. The absence of community platforms to celebrate their cultural identity and expression was also on her mind.

It was always difficult not to notice Merry Norris, a dear friend of mine, called the ”godmother of art and architecture in Los Angeles.” Alissa Walker of Curbed Magazine wrote that she dressed head-to-toe in prerequisite black, draped in whimsical accessories, with an asymmetrical bob that tucked around her chin like a piece of site-specific sculpture.” Wherever she went a crowd gathered. And she always occupied the center. Norris began to enhance her fascination with art and design while serving as a patron and docent at the Santa Barbara Museum of Art in the mid-1960s. And then she began to collect. In the early 1970s, she married William Norris, who was running for California state attorney general, a race he lost. The couple relocated to Los Angeles and shared their mutual interests in arts and politics.

Over lunch, she confided that she took trips to New York to attend art auctions and bidding and to visit galleries. Although Los Angeles had many good artists, she was repeatedly told that nothing was really happening there. I cited what Fred Nicholas had told me, that while he had as clients almost 80 percent of LA galleries, there truly was no activity.

In 1984 Mayor Tom Bradley appointed her to the city’s Cultural Affairs Commission. “I wasn’t sure what that was, but it sounded like a nice honor.”

Norris eventually became chair of the Commission and changed the way LA designed public buildings, reported the Los Angeles Times. By enlisting architects, she oversaw a revamp of the city’s design standards, resulting in transformative civic landmarks such as the Central Library expansion in Downtown, and contextual neighborhood outposts like fire, police, and water and power stations.

“The Commission did not have an architect on staff but occasionally borrowed one from Recreation and Parks who showed little interest,” she told me. “Everything looked like Taco Bell,” she said. So, she went seeking help from celebrated architect Jon Jerde who put together a group that had an architect advising her at every commission meeting.

She mentioned George Takei, the actor best known for his role as Mr. Sulu in the original Star Trek television series, a very valuable member of the Commission. Takei, a member of the Rapid Transit District (RTD) Board of Directors, strongly supported my art program for Metro stations which, he said, gave meaning and identity to the stations, a sense of place. “The station artwork gives the ridership a sense of continuity with the community.”

Norris was widely known as a co-founder of the city’s MOCA and was instrumental in founding the influential architecture school, SCI-Arc, and served on its board of trustees. When the Community Redevelopment Agency offered land on Bunker Hill if enough money was raised for an arts museum that had community support, Norris accepted the challenge, saying. “That’s when I became a fundraiser.”

Norris cited the “percent for art” fee whereby 1.5 percent of all construction, improvements, or renovation projects undertaken by the city be set aside for public art projects, while a similar fee must be set aside by private developments. However, using her husband’s contacts with ARCO she brought in Bill Kieschnick, the company president and chief executive officer, who eventually stabilized MOCA, while serving as the museum’s board chairman.

She also told me about Lennie Greenberg, who with her husband were major art collectors. “Lennie was a fundraiser volunteer,” she said, and eventually became president of the board.

Norris also mentioned Marcia Weisman, the sister of Norton Simon, an avid modern art collector. With her husband, Fred, she hosted many parties and lectures in their home and a community of collectors formed around these conversations. She is credited for her generosity and the founding of MOCA, which contains much of her collection. But Norris confided

Atlantic Richfield Tower Photo: Courtesy of L.A. Conservancy

tomb so impressive it was regarded as one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. From King Mausolus we get our word ‘mausoleum.’ The structure stood almost 150 feet tall, and its spectacular roof was pyramidal.

According to Clark Construction, the general contractor, with AC Martin Partners the designer, the retrofitted City Hall can withstand a magnitude 8.2 earthquake.

“Its architecture, and particularly its Spring Street entrance and grand rotunda, have helped City Hall stand out as a visually striking location in scores of television productions and feature films,” said Phil Sokoloski, vice president of integrated communications for FilmLA. “The building remains a captivating shooting location.”

For the late City Councilman Tom LaBonge, “City Hall was his second home,” his wife, Brigid, said. She recalled the days when her husband would drive around the city with the family, noting that for years no buildings were allowed to be taller than City Hall.

As a matter of fact, from 1928 until the late 1950s, it was the tallest building in Los Angeles and shared the skyline with only a few structures having decorative towers, including the twelve-story Richfield Tower on South Flower Street and the thirteen-story Eastern Columbia Building on Broadway.

A 1905 municipal ordinance set the maximum height at 130 feet. Subsequently, there were so many requests for variances the city voters approved a City Charter amendment effective 1911 establishing the 150-foot height limit that remained until 1958.

The first “skyscraper” constructed after the height limit was rescinded was the eighteen-story United California Bank building at Sixth and Spring streets, built in 1961. It is presently an apartment building. The thirty-story One Wilshire high rise followed in 1966,

and then the forty-story Union Bank Plaza on Bunker Hill at Fifth and Figueroa streets, built in 1968.

Paul Gleye, an architectural historian, said that the idea that the height limit arose from earthquake concerns was a popular misconception. The San Francisco earthquake occurred in 1906.

The truth is that Los Angeles residents did not want their city to become another Manhattan. The main factor was aesthetics, Gleye said.

Los Angeles’s representational persona, a few years from its 100th birthday, star of television and film, lies in splendor embraced by modern structures. Its observation level on the twenty-seventh floor provides a panoramic view of the City of Angels, while viewers far and wide can look at the civic center and see the majesty of City Hall and feel the pulse of its city.

Los Angeles City Hall was designated a Los Angeles Historic Cultural Monument in 1976.

An Essential Rebirth | have been particularly interested in the Los Angeles Central Library for more than fifty years. My consulting engineering office for many years was at the six story Beaux Arts building previously known as the Pacific Mutual Building and now known as PacMutual at Sixth and Olive streets. I would see the library building almost daily as I walked back and forth between my office and the Jonathan Club, which is on Sixth and Figueroa and is the place I used as my gym, daily parking, and venue for my social, professional, and political meetings and events for decades. I therefore followed with great interest what was happening with the library building over the years.

The Central Library, dedicated in 1926, was designed by architect Bertram Grosvenor Goodhue, FAIA. The library sits where the State Normal School was built in 1881, which later evolved into the University of California, Los Angeles. The person who helped lay the Los Angeles Public Library groundwork was Charles F. Lummis, a journalist and activist for Indian rights and historic preservation, who was appointed city librarian in 1905. Lummis’ acquisitions brought acclaim to the library’s special collections on the history of California and the West. Lummis was a scholar, before entering Harvard University, his minister father had taught him Greek, Latin and Hebrew. He resigned as head librarian in 1911 and established the Southwest Museum.

The library building includes architectural elements of Egyptian, Spanish Colonial, Roman Byzantine and various Islamic civilizations and displays formal minimalism. The second floor of the library has a high-domed rotunda full of light and color, and at the center of the dome is an illuminated globe chandelier with the signs of the zodiac. Twelve murals on the walls painted by Dean Cornwell in 1933 depict the history of California.

There was a plan since the late 1970s to tear down the Los Angeles Central Library, sell the property, and build a new library, according to Donald Spivack, deputy chief of operations and policy for the Los Angeles Community Redevelopment Agency. Architect Charles Luckman had recommended the replacement of the library and had drawn plans in the late

Inglewood because it was easier, Roski and me preferred downtown because it was better.” He concluded that football can’t be played downtown because it requires tailgating. “People get there at 8 in the morning and tailgate all morning and all night. You need exceptionally large, dedicated parking spaces.”

But Staples Center came alive. After an implausible start, stormy public debates, myriad acts motivated by political intrusions and developer interests, the blessings of a Cardinal and the skepticisms of detractors, a world-class sports and entertainment venue became real, hosting four professional sports franchises, and holding more than 250 events and more than four million guests annually.

Located at the spectacular LA Live complex downtown, Staples Center added to Los Angeles’s international fame and its position as a prominent world-class city.

Widely advertised as “the happiest place on earth,” Disneyland has long claimed magical characteristics. Therefore, when the concept of the Walt Disney Concert Hall was officially announced it was natural to assume that it would have the same legendary Disney enchantment. But on the way to becoming Los Angeles’s symphonic masterpiece the project limped badly and almost crashed, victimized by disturbing funding shortages, bickering, and protracted construction holdups.

For years, the prospect of never hearing a note reverberate on its walls had become real and disheartening. A disharmony had ensued that stigmatized the project and its stewards, and a bitterness surfaced that was widely viewed as a dark omen for the concert hall.

On May 12, 1987, Lillian Disney, Walt’s widow, donated $50 million to the Music Center to construct a new home for the Los Angeles Philharmonic—one of the largest single cash donations to support the arts. Her conditions were firm, among them being its location on a Los Angeles County-owned parking lot across 1st Street from the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion at the Los Angeles Music Center, and of course, it being named after her late husband. Her offer was subject to approval of Los Angeles County, the Music Center, and the Philharmonic Association within thirty days. Required also was a county agreement to build an underground parking garage on the 3.6-acre site with groundbreaking in five years, by December 31,1992, or the gift would be rescinded. Lillian Disney also insisted that any adjoining development be designed by the same architect who designed the hall.

Attorney F. Daniel Frost was then chairman and chief executive officer of the Music Center, but it was his wife, Camilla, a member of the influential Chandler family that owned the Los Angeles Times, who immediately recommended Frederick Nicholas to chair the Walt Disney Concert Hall Committee. She had voiced her staunch support noting that Nicholas was an old hand in dealing with civic complexities, had built the Museum of Contemporary Art and was also MOCA’s chairman.

I had known Nicholas since the mid-1970s, and had always respected and admired the quality and elegance of his work, combining his legal career with major real estate

engagements. Indeed, for me, he was a notable builder of institutions for the arts in our city. Besides his role in the building of MOCA, the Geffen Contemporary, and the Walt Disney Concert Hall (for which he was called “Mr. Los Angeles Downtown Culture”), Nicholas practiced real estate law for more than fifty years and was involved in founding Public Counsel, the largest pro bono law firm in the world; developing numerous shopping centers and office tower complexes around the country; and major activism in Democratic politics. Over lunch he explained to me that when the offer came, he was not sure he could take on the added responsibility, but his wife insisted.

“Well, let me talk to Mrs. Disney,” he finally said, and described for me the reason; he wanted to “get her feelings about what she wanted and whether or not I can do the job.” Nicholas was driven to her house in Carolwood Estates in Holmby Hills and had an hour-long meeting. The meeting was crucial, he told me, because he was seeking answers on significant subjects, first being his desire to know if she wanted a world-class architect. “If not, I’m not interested in the project.” “You were not interested in building a box,” I surmised. “Yeah, a box it cannot be. It had to be world-class.” “That’s what I want: a world-class project,” Lillian Disney said, according to Nicholas’ recollection of their meeting. “I want lots of flowers, a beautiful garden.”

The conversation continued, embracing other fundamental issues, before Nicholas became unusually assertive. “I want to resolve another issue with you.” “What’s that?” she asked. “I’m Jewish, and I want to know if that’s a problem for you.” “Why would you ask me a question like that?” she wondered.

“Because your husband, Walt Disney, had a reputation of being anti-Semitic.” Her response was genuine and straightforward. “That is the most ridiculous thing I’ve ever heard. Of course, I have no objection.”

The realization that there would be many years, even decades, before Measure R could deliver on its promise prompted Metro, Denny Zane, and community leaders to envision what it would take to accelerate these investments.

Metro supported Connecticut Senator Chris Dodd's legislation to create a National Infrastructure Development Bank. It was envisioned the bank would provide access to federal dollars secured by Measure R revenue to enable acceleration of transit investments so that Metro could build the thirty-year Measure R plan in just ten years. President Obama endorsed the National Infrastructure Development Bank, but it fell aside during the struggle to create the president's signature Affordable Care Act.

Jaime De La Vega, Villaraigosa's transportation deputy, and Richard Katz, Metro board member, designed a second ballot measure for November 2012 that would extend Measure R’s term from thirty years to sixty years, Measure J and the "30/10 Plan." The additional revenue Measure J would provide in the second thirty years, it was argued, would allow Metro to secure greater and more favorable bond and federal financing and enable the acceleration of the Measure R`s 30-year program such that it might be built in 10 years.

However, Measure J failed on November 6, 2012, to reach the required two-thirds vote, though it won a supermajority of 66.11 percent with a relatively low turnout election and limited campaign funds. It can be argued that if the Gold Line (L Line) in San Gabriel Valley had been included in Measure J, the voters might have approved it. Measure J demonstrated that LA County voters had a real appetite for investment in transportation progress and were not afraid of taxing themselves to pay for it.

Possibly, the loss of Measure J was fortuitous. Measure J made Measure M possibleanother half-cent sales tax for November 2016. Measure M proposed to not only accelerate Measure R projects but also to add more projects around the county to ensure all the county's communities would benefit. Measure M had no sunset and amended Measure R to eliminate its thirty-year sunset.

Both measures would be operative until L. County voters might elect to end them. Together, they could provide, along with Propositions A and C, a permanent funding for investments in Los Angeles County`s transportation modernization.

Mayor Eric Garcetti, elected in 2013, started to put together a plan for a new Metro countywide ballot measure in his second month in office. It would be similar to Measure R, which was approved by the voters during Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa's administration in 2008. Garcetti’s vision was big, thinking regionally, emphasizing the importance of working with every mayor in Los Angeles County. He wanted to be seen as a consensus and coalition builder. He delegated the project to his capable and savvy deputy for transportation,

Mayor Eric Garcetti’s rail plan for the 2028 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles. Courtesy of Jake Berman of 53 Studio

Borja Leon. Garcetti convened a meeting in City Hall with the majority of the mayors of the eighty-eight cities in Los Angeles County. Borja made a presentation on the state of transportation and infrastructure in Los Angeles County. Garcetti asked the mayors if they would be supportive of another transportation ballot measure that would further fund Metro’s rail, bus, and highway programs. Almost all the mayors raised their hands in support of another ballot measure. The next step was to do a countywide poll to determine if the voters would support such a measure. The services of Garcetti’s pollster Fred Yang and chief strategist Bill Carrick were enlisted. In the fall of 2013, a poll was conducted, and the measure received decent support.

During that time, Metro was conducting an outreach effort to all the subregions in the county to identify all transportation related priorities. The effort was helpful to understand the different projects that were important at different parts of the county. This effort started after Measure J failed to be approved in 2012. Measure J would have extended the existing one-half cent sales tax for additional years. Because of the failure of Measure J, several Metro board members were reluctant to support a new measure. Los Angeles County Supervisor and Metro board member Michael Antonovich argued that Measure J favored the acceleration of projects within the City of Los Angeles. This time, however, Antonovich initiated the meetings with the cities trying to get their buy-in by asking them to give Metro a list of possible projects, what Metro called the “Mobility Matrix.”