Meet the trailblazing US conductor

We explore why the Austrian’s symphonies provoke such deep division

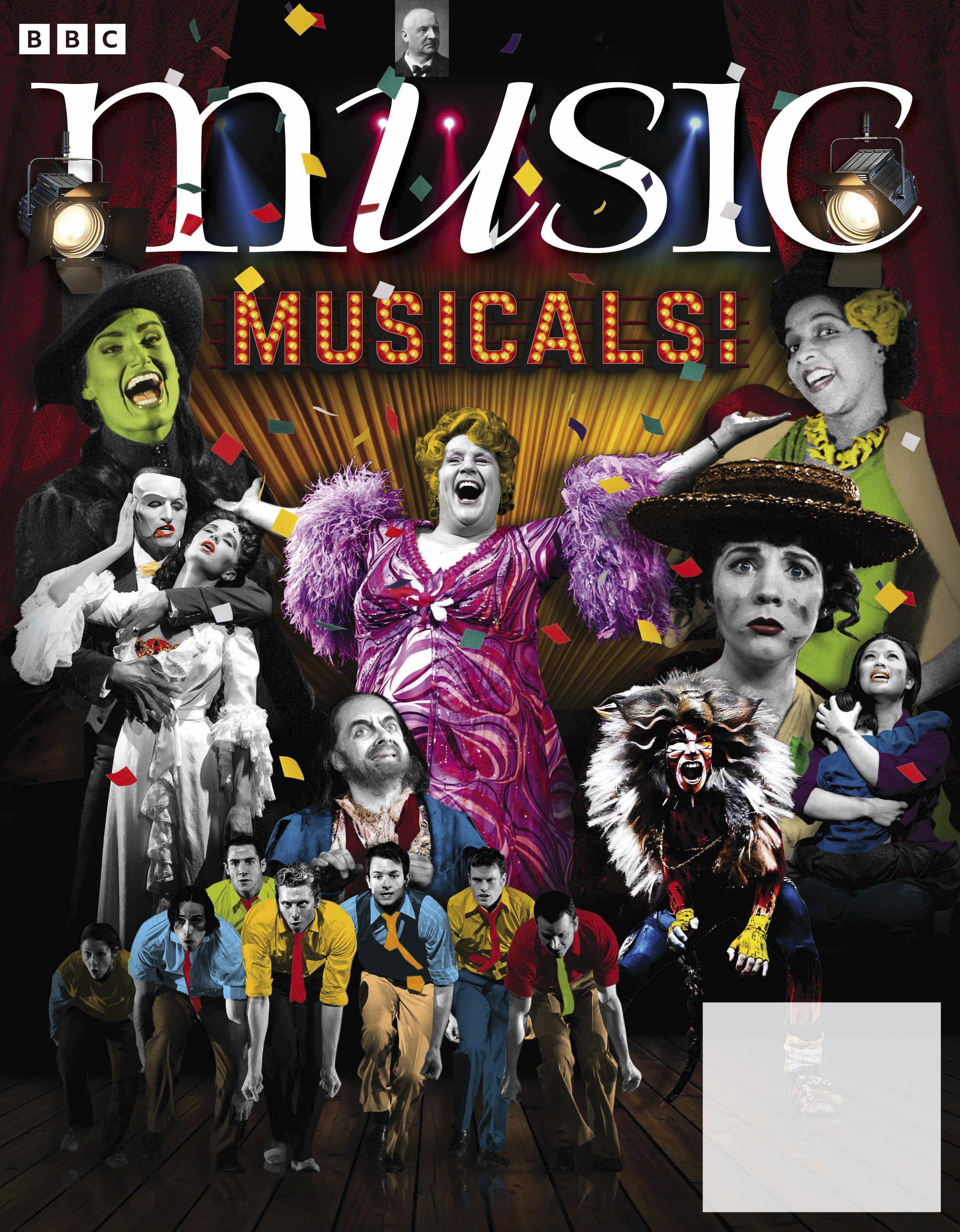

How opera gave birth to the world’s greatest stage shows

Also in this issue… Beethoven’s remarkable late creative surge

How Myra Hess brought joy to wartime Britain Smetana’s hymn of love to his Czech homeland

Pick a theme… and name your seven favourite examples

Violinist Augustin Hadelich selects outstanding works for his instrument by American

Born in Italy to German parents, Augustin Hadelich was a child prodigy who studied both violin and piano. He went on to attend the Juilliard School and, in 2006, won first prize at the International Violin Competition of Indianapolis. Since then, he has become one of the world’s best-known soloists, and regularly performs with orchestras including the Berlin Philharmonic and the Royal Concertgebouw. His new album American Road Trip – a journey across the vast US landscape – is out now.

Barber Violin Concerto

When I perform this piece in Europe, I am sometimes asked where I discovered it, as though I dug it up in an attic. In the US, though, it is one of the most popular violin concertos. Barber’s music is lush and heartfelt, with none of the self-consciousness that some of his contemporaries felt about writing Romantic music during the time of modernism. For this piece to work you have to play it with a kind of innocence, without succumbing to the temptation to do too many slides. It’s not meant to be a cheese fest, and is in fact a deeply moving work.

John Adams Road Movies

John Adams is a master of Minimalism, and here he does a wonderful job of capturing the joys of driving in America. The first movement conveys the relaxed feeling of travelling down a long road. You feel the engine, wheels and maybe some potholes (roads in America can be really bad; you wouldn’t hear so many potholes if John Adams was German.) The second movement is languid, evoking a desert landscape or a traffic jam on a summer’s

day, while the third movement is like fast highway driving – by the end, I’m euphoric.

Coleridge-Taylor Perkinson

Louisiana Blues Strut

Perkinson had a varied career: he wrote serious music, arrangements and music for TV and commercials. This composition starts playfully, in the Blues style, with a real swagger to it, but there are all sorts of complex rhythmic tricks to surprise the audience, and sometimes the key goes off to weird places. What’s difficult is that it has to be played with ‘swing’ (which is hard enough for classical players), but not so much that it distorts the syncopations. So you have to turn the swing on and off constantly. It’s rhythmically one of the hardest pieces I know, but enormously fun for the audience, who will often clap along.

Amy Beach Romance

I sometimes find late Romanticism a bit emotionally exhausting, but in this short piece it’s just gorgeous. It’s a slow, sentimental work for violin and piano in a similar vein to Salut d’amour, and it’s one

of the best examples of its genre. It really pulls at your heart strings and yes, the way that Beach enjoys every suspension is quite indulgent. But there’s a real pleasure in playing something that’s so sweet.

Charles Ives

Sonata No. 4, ‘Children’s Day’ Ives always swam against the tide. In this piece, he evokes the memory of a religious children’s camp he attended in the 1870s. There was a lot of communal musicmaking at these camps, and in this piece, you hear several songs sung at the same time from different rooms in different keys, until eventually it gets quite cacophonous. I find it joyful but also nostalgic: you can imagine the soundscape of this camp, and you get the sense that these are intense memories for Ives. The slow movement, with its slow hymns, is really transporting.

Leonard Bernstein Serenade (after Plato’s ‘Symposium’) Although this piece is loosely inspired by the Symposium, Plato’s Socratic dialogue about the nature of love, I wish Bernstein hadn’t referred to this in the title: it makes audiences expect something intellectual and hard to understand when, in fact, it’s full of joy. There are beautiful moments of lyricism in the slow movement, while the rest is more playful and jazzy. It works best when players can connect with its warmth, as well as its elements of dance and jazz.

Eddie South Black Gypsy

South was a violinist and prodigy, who grew up in Chicago in the early-20th century. He was black, so couldn’t have a classical career in America. Instead, he played in jazz bands and travelled to Europe, where he met Django Reinhardt – godfather of Gypsy jazz – and absorbed many influences before returning to America. Black Gypsy is an effective little showpiece –jazzy, charming, sentimental – and one that doesn’t take itself too seriously. I’m sure if the music were easier to get hold of, it would be played all the time.

Interview

by

Hannah Nepilova

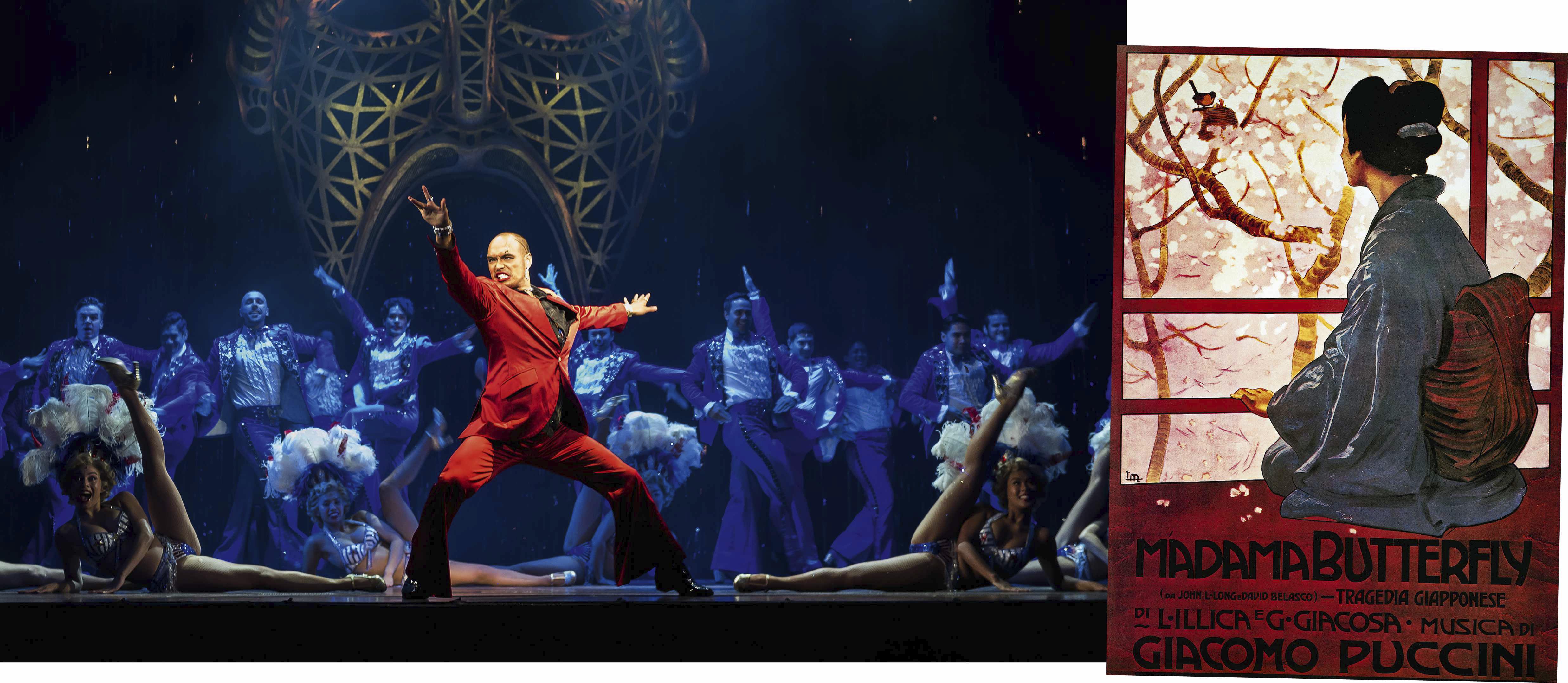

Were Rodgers & Hammerstein the Puccini of the mid-20th century? If so, where do operas end and musicals begin? James Inverne explores the classical origins of today’s musicals…

Immediately after the end of World War II, US Army forces marched into Bayreuth, shrine of Wagner’s operas and a beloved hang-out of Adolf Hitler. The famous Festspielhaus was repurposed and given over to various populist entertainments including musical revues – a calculated poke in the eye for Hitler’s ideal of the master artform for the master race. Yet, ignoring for a moment the Nazis’ twisted

artistic logic, is there really such a vast gap between the world of opera and the world of what revues evolved into –namely, musical theatre? With English National Opera performing My Fair Lady in 2022, to say nothing of John Wilson’s recording of Oklahoma! scooping BBC Music Magazine’s 2024 Opera Award, it’s a question worth asking.

In fact, if opera is ‘high art’ (not always) and musicals are ‘low art’ (not at all), the road that connects them is virtually flat, and well travelled. After all, what makes Mozart’s The Magic Flute, a piece of 18thcentury Viennese music-hall populism, combining speech, music and movement, not a musical of its day? It happens to be a sublime masterpiece, but then so is

How is The Magic Flute, a piece of musichall populism, not a musical of its day?

My Fair Lady. Bizet’s Carmen was judged to be so close to a musical that it was rejigged by orchestrator Robert Russell Bennett and lyricist Oscar Hammerstein II to become one in 1943, Carmen Jones. Even the most intellectual of composers haven’t kept their distance – Stravinksy wrote a ballet sequence for a 1944 Broadway revue, The Seven Lively Arts. William Schuman, before becoming a byword for uber-serious academia, penned popular songs with future

musicals king Frank Loesser. Zipping forward a few decades, in 2005 Thomas Meehan, the irrepressible script writer for Annie, Hairspray and The Producers, turned librettist for Lorin Maazel’s opera 1984. Meanwhile, 2003’s foul-mouthed, formally-constructed Jerry Springer: The Opera was either a musical that utilised the ennobling power of operatic form, or the other way round (or something).

Although the relationship between opera and musicals has always been

I like the idea that players can inject a lot of themselves into the music. But it involves trust, in both directions

As the US conductor marks 25 years as music director of the Buffalo Philharmonic, she speaks to Clive Paget about being a female trailblazer and the mentors who supported her

JoAnn Falletta is no stranger to milestones, but even she accepts that 25 years as music director of the Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra is a big one. Such landmark anniversaries are rare, and see her welcomed into an elite pantheon of quarter-centenarians that includes Zubin Mehta at the Israel Philharmonic and Iván Fischer at the Budapest Festival Orchestra. But Falletta is many things besides. She’s a double Grammy Award winner, a prolific recording artist with an omnivorously eclectic repertoire, and a tireless evangelist for community engagement.

‘It’s all gone very fast,’ she admits of her time in Buffalo, New York State’s second largest city, at times unfairly belittled as a blue-collar town with somewhat challenging weather patterns.

Today, her imprint is all over the orchestra. ‘At this point I’ve probably appointed more than two thirds of the players,’ she explains, speaking over Zoom from the US. ‘We’ve been through difficult times, like the pandemic, but the relationship has grown stronger. For me, it has created an orchestra with a personality, but one that has become more independent and more exuberant.’

As we chat away, it’s clear why Falletta is so admired and roundly liked in the business. She’s thoughtful, generous with her time and quietly modest about her achievements. Some of those traits she likes to think she’s fostered in her players. ‘I believe very much in flexibility,’ she says. ‘There’s a kind of plan you have in rehearsal and then a blossoming – or a risktaking – in the concert. I like the idea that players can inject a lot of themselves into the music, and of course when you know an orchestra you can let them do that. But it involves a lot of trust, in both directions.’

It’s a relationship founded on familiarity and mutual respect. ‘Being with a group of musicians for so long, you see so much of their lives,’ she explains. ‘The happy

Composer of the Week is broadcast on Radio 3 at 4pm, Monday to Friday. Programmes in October are:

30 Sept – 4 Oct Dorothy Howell

7-11 October To be confirmed

14-18 October Ives

21-25 October Margaret Bonds and her circle

28 Oct – 1 Nov Liszt

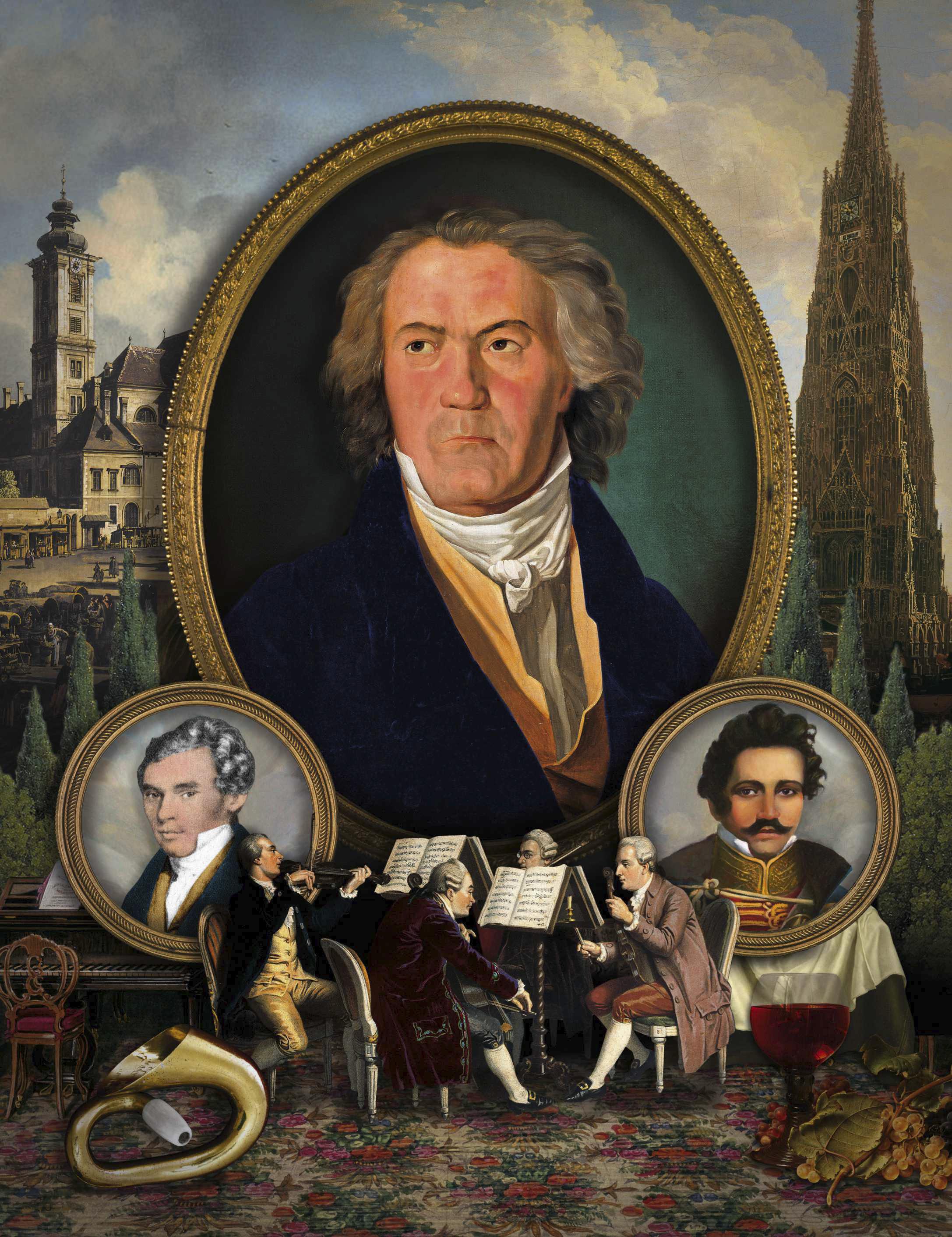

Though deaf and in badly declining health, the ageing Beethoven remained extraordinarily inventive to the end, as Misha Donat explains

ILLUSTRATION: MATT HERRING

Slow introductions

Each of the first three late quartets begins with a slow introduction, which returns at crucial points during the main body of the first movement like punctuation marks, giving the piece greater weight and seriousness and underlining its unity.

Multi-movement forms Among the late quartets, only the first and last are cast in a traditional four-movement form. The others have between five and seven movements, providing Beethoven with a larger canvas to work on, and lending the music an almost modular aspect.

Variations During the last dozen years or so of his life, Beethoven became increasingly attracted to variation form. In all but one of his five late string quartets the centrepiece is a set of variations – not a display piece, but a serene interlude that forms the work’s expressive heart.

Fugues Another preoccupation in Beethoven’s late period was the fugue. Like the ‘Hammerklavier’ Piano Sonata, the String Quartet Op. 130 was designed to culminate in an enormous fugal finale which made unprecedented demands of both performers and listeners. Beethoven’s next quartet, Op. 131, begins with a much smaller and more intimate fugue, this time based on a subject that could have stepped straight out of Bach’s (above) Well-Tempered Clavier.

On 7 May 1824, Beethoven directed the premiere of his monumental Ninth Symphony, with its famous Finale setting Schiller’s Ode to Joy, in Vienna’s Kärntnertor Theatre. Fortunately, a second conductor had been engaged, because the performance taking place in Beethoven’s mind had only a tenuous connection with what was happening on the stage. As the symphony came to an end, the deaf composer still had his head buried in the score, and he had to be turned round by one of the solo singers so that he could see the wildly enthusiastic applause, even if he couldn’t hear it.

Just a month earlier, Beethoven’s equally

to the virtual exclusion of all else. At no other stage in his career did he involve himself for such a long period with a single genre, and his five late quartets form an artistic testament of a unique kind – one in which each individual work has its own distinctive shape and character, while at the same time forming part of a single overarching project with common threads running through it.

Beethoven completed the first of his three quartets for Prince Galitzin just in time for its premiere on 6 March 1825, and he had already begun sketching ideas for the next quartet. In the autumn of that year, the conductor Sir George

Beethoven was to concentrate on composing quartets to the virtual exclusion of all else

large-scale Missa solemnis received its first performance – not in Vienna, but in St Petersburg. The event was organised by Prince Nikolai Galitzin (or Golitsin), who had first approached Beethoven in November 1822, telling him: ‘Being both a passionate musical amateur and a great admirer of your talent, I am taking the liberty of writing to you to ask if you would consent to compose one, two or three new quartets, for which I would be pleased to pay you the fee which you will judge appropriate for your trouble.’ With the labours of the Mass and the symphony behind him, the idea of turning his attention to the more intimate sphere of chamber music must have come as a welcome change to Beethoven.

As things turned out, during the last years of his life Beethoven was to concentrate on composing string quartets

Smart travelled to Vienna to meet Beethoven and discuss with him the tempos for his symphonies, including the Ninth, of which he was due to conduct the English premiere. On 9 September, Smart witnessed the first, semi-private, performance of Beethoven’s latest string quartet. The members of the quartet led by the renowned violinist Ignaz Schuppanzigh had assembled at the Viennese tavern Zum wilden Mann, where the publisher Maurice Schlesinger, who had acquired the rights to the new work, had rented a room for the occasion.

The meeting between Smart and Beethoven was engineered by the quartet’s second violinist, Karl Holz. Smart noted in his journal: ‘There was a numerous assembly of professors to hear Beethoven’s second new manuscript quartette, bought by Mr. Schlesinger. This quartette

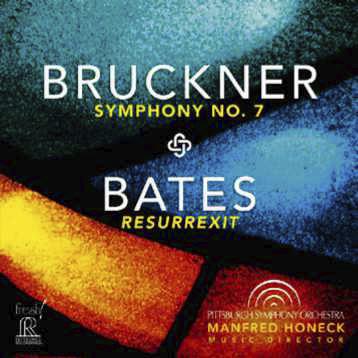

We can’t seem to move for composer anniversaries lately, from Holst and Schoenberg’s 150th in September to Bruckner’s 200th in October. The latter’s Seventh Symphony has been treated to a glorious live recording by the Pittsburgh Symphony, as you’ll discover opposite, while Schoenberg’s Pelleas und Melisande takes the lead spot in Orchestral. He does share the podium with Fauré’s take on the story, but that’s also timely as we’re creeping up on the centenary of the French composer’s death in November. In fact, this issue is a bit of a Fauré feast, with new releases scattered throughout, including those from Renaud Capuçon, Le Concert Spirituel, Robin Michael and Daniel Tong, Aline Piboule and the figure humaine kammerchor. Michael Beek Reviews editor

This month’s critics

John Allison, Nicholas Anderson, Michael Beek, Terry Blain, Kate Bolton-Porciatti, Geoff Brown, Michael Church, Christopher Cook, Martin Cotton, Christopher Dingle, Misha Donat, Jessica Duchen, Rebecca Franks, George Hall, Claire Jackson, Michael Jameson, Berta Joncus, John-Pierre Joyce, Nicholas Kenyon, Ashutosh Khandekar, Erik Levi, Andrew McGregor, David Nice, Freya Parr, Ingrid Pearson, Steph Power, Anthony Pryer, Paul Riley, Suzanne Rolt, Jan Smaczny, Jo Talbot, Anne Templer, Sarah Urwin Jones, Barry Witherden

KEY TO STAR RATINGS

HHHHH Outstanding

HHHH Excellent

HHH Good

HH Disappointing

H Poor

eloquent performance

Mason Bates • Bruckner

Bruckner: Symphony No. 7; Mason Bates: Resurrexit Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra/Manfred Honeck Reference Recordings FR-757SACD 77:02 mins

Manfred Honeck has already released Bruckner’s Fourth and Ninth symphonies with the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra, to widespread acclaim. This new Seventh ups the ante further: it’s undoubtedly one of the best recordings of the symphony in the digital era.

The Pittsburgh cellos exude a wonderfully reassuring confidence in the expansive opening theme, and the violins display a similar savoir-faire on taking it over a

page later. This is an orchestra by now deeply acculturated to the Austrian conductor’s essentially old-school style of Bruckner interpretation, with warmly blended tones and a meticulously gradated approach to the music’s architecture.

The Adagio is beautifully paced, much of its eloquence deriving from the forensic detail Honeck bakes into dynamics and accentuation, without obtrusive fussiness. The long ascent towards the movement’s principal peroration is made in masterly fashion, and Honeck thrillingly includes the cymbal crash at its summit. The four Wagner tubas in the coda are ideally dignified and sonorous. Follow that, as they say. And Honeck does, in a bristling account of the Scherzo with bounding folk-dance rhythms and shards of birdsong jagging sharply through the textures. Bruckner adored the natural world, and Honeck mentions in his detailed booklet essay the proliferation of bird sounds woven into the fabric of the movement. Bruckner as musical ornithologist, half a century

before Messiaen? Honeck suggests as much, in the sharp rusticity of the woodwind playing in his interpretation.

The Finale launches with purposeful alacrity, the violin theme sporting an almost Mozartian joie de vivre, echoed athletically in the lower string responses a few bars later. So often in performances of the Seventh, what comes after the Adagio seems curiously anticlimactic, as though its sombre meditations make afterthoughts superfluous. Not here – in Honeck’s view both the Scherzo and Finale are bracingly consequential, and the symphony ends with an almost jaunty optimism and a brilliantly flaring contribution from the excellent Pittsburgh brass section.

Unusually there is a coupling: Resurrexit, an 11-minute piece by American composer Mason Bates. Commissioned to mark Honeck’s 60th birthday and performed alongside Bruckner’s Seventh at concerts in Pittsburgh in March 2022,

The symphony ends with a brilliantly flaring contribution from the brass section

it is exotically scored, punchily expressive and well worth hearing. Based on the Christian Easter narrative, the piece requires a phalanx of extra percussion instruments, including the semantron (a large wooden plank hammered by mallets). The flavour is

Do you prefer to record live?

I don’t like studio recordings very much. It’s always my intention to get the sound on the recording as close as possible to what you would hear in the hall. I think the sound engineer did a wonderful job setting the microphones, so that you really feel that you are sitting in Heinz Hall and listening to the orchestra. Fortunately, Heinz Hall sounds great, with a lot of great resonance; it’s perfect for Bruckner and his world.

Middle Eastern, with swirling woodwind ululations and scatter-gun brass fanfares at the exultant conclusion.

It’s a more than interesting makeweight, but the Seventh is what most listeners will go to this album for, and they will not be disappointed. It’s a glowing testament to the high levels of synergy and mutual comprehension that Manfred Honeck and the Pittsburgh Symphony have achieved in his 16 years as music director, particularly in Bruckner.

The live recording of both works is excellent, catching both the power and splendour of the Pittsburgh playing, not to mention its manifold subtleties of tone and inflection.

PERFORMANCE HHHHH

RECORDING HHHHH

What do you bring to Bruckner? I have conducted Bruckner a lot, and I sang all the motets as a choirboy, so I would say I was very familiar with Bruckner in childhood. He has a reputation of being very religious, and so the sacred element has been very prominent in interpretations, and for others the intellectual line is more important; he was a fantastic professor. But one of the things which has been a little bit ignored is Bruckner’s love for Austrian folk music (the dances, the Ländlers), and I think this is very important to know. It’s one of the aspects that I wanted to bring out within Bruckner’s world. It shows Bruckner as a whole, in a complete way.

Tell us about pairing Bruckner with Mason Bates… I was impressed by the pieces of his I had conducted; so at one point I said to him, ‘Why don’t you do a spiritual piece?’ He thought for a long time about it and this was the result. I did not expect that the Pittsburgh Symphony would be commissioning the piece for my 60th birthday! So I’m very thankful for that. When I decided to have the Bruckner 7 on an album, it was the first thing that came to mind to pair it with.