CHALLENGE FOR GRIZZLIES 100 DAYS YELLOWSTONE TO YUKON BONDED BY THE RIVER HEMINGWAY'S Cooke City Revival CONRAD ANKER COMMUNITY WILL SAVE US

2 EST. 1997 Big Sky, MT bigskybuild.com 406.995.3670 REPRESENTING AND BUILDING FOR OUR CLIENTS SINCE 1997

We have dedicated our lives to service. In fact, our brand is more than a story, it's part of American history.

Authentic, All-American and Award winning. It is our legacy in a bottle.

Official Bourbon Sponsor horsesoldierbourbon.com

San Francisco World Spirits Competition 2022

©2023 American Freedom Distillery. All rights reserved.

San Francisco World Spirits Competition 2022

©2023 American Freedom Distillery. All rights reserved.

4

“O

ering clients a great place to shop as well as a home design showroom.”

Jodee March

Owner/ Interior Designer

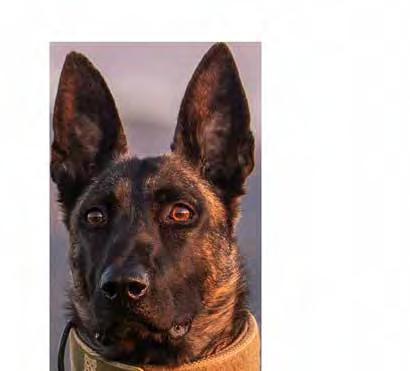

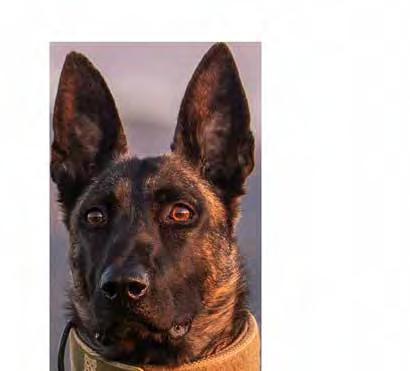

Are you ready to Svalinn love?

Svalinn breeds, raises and trains world class protection dogs. Choose a Svalinn dog and you’ll be getting real peace of mind in the package of a loyal, loving companion for you and your family.

5

svalinn.com 406.539.9029 Livingston, MT

BOZEMAN | BIG SKY | LIVINGSTON | ENNIS | BUTTE © 2023 Engel & Völkers. All rights reserved. Each brokerage is independently owned and operated. All information provided is deemed reliable but is not guaranteed and should be independently verified. Engel & Völkers and its independent License Partners are Equal Opportunity Employers and fully support the principles of the Fair Housing Act. www.montana406.com www.evranchland.com Your Bespoke Montana Real Estate Firm

7 FIND Chasing billfish in Costa Rica or Cabo or relaxing along the Emerald Coast of Florida, Jimmy Azzolini, Big Sky resident, is your authority on yacht ownership. Jimmy has been with Galati Yacht Sales, the largest family-owned yacht brokerage firm worldwide, since 2000. During this time, Jimmy has helped countless families match the right yacht to their lifestyles. Find out more about yacht ownership and how Jimmy and Galati Yacht Sales can help you create new memories. JIMMY AZZOLINI LICENSED + BONDED YACHT BROKER 850.259.3246 SCAN HERE TO LEARN MORE FL | AL | TX | CA | WA | MX | CR WWW.GALATI YACHTS .COM

FEATURES

31

COMMUNITY IN CONTEXT

Photos by Hazel Cramer and Christopher Boyer

Two Montana photographers put Community in Context with aerial photos shot from the belly of Chris Boyer’s red 1956 Cessna plane, and Hazel Cramer’s intimate portraits of the same towns from the ground. These visual profiles of Lame Deer, Anaconda and Big Sky invite us to contemplate the meaning of community.

78

THE BIG TWO-HEARTED RETREAT

By Toby Thompson

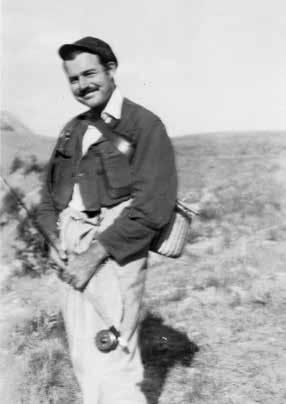

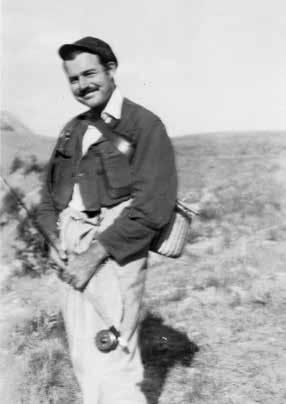

One of the most recognized American novelists in history, Ernest Hemingway is among literary scholars’ greatest curiosities. At the 2022 Hemingway Society Conference, scholars, writers and other prolific figures gathered in Montana’s rustic Cooke City to examine the writer’s relationship to the wild landscape of Montana and Wyoming, exploring topics from gender and sexuality to Hemingway’s affinity for killing at The Big Two-Hearted Retreat.

102

THE ARENA OF CHALLENGE FOR GRIZZLIES

By Benjamin Alva Polley

Amidst what experts describe as one of the biggest conservation wins in history, grizzly bear recovery in certain ecosystems has officials reevaluating the iconic bruins’ decades-old protection under the Endangered Species Act. In The Arena of Challenge for Grizzlies, stakeholders debate the species’ fate.

152

THE LANGUAGE OF BELAY

By Bella Butler

One of the greatest climbers in history, Conrad Anker has spent decades completing first ascents and notable mountaineering feats around the globe. Now, at age 60, the Bozeman local is translating The Language of Belay to the concept of community.

8

Cowboys at Big Sky PBR take a break from pirouetting off the backs of bulls for a quiet game of hacky sack behind the chutes. The annual summer event, produced by Outlaw Partners, pits the best bulls against the best cowboys and began 13 years ago in a sagebrush field, since growing to win 9x Event of the Year and gathering the community for a week of celebration each July. Photo by Tom Attwater.

9

2010 GILKERSON DRIVE, BOZEMAN, MT 59715 | SBCONSTRUCTION.COM | 406.585.0735

GENERAL CONTRACTING FOR LUXURY REMODELING & NEW CONSTRUCTION pjourney@jandsmt.com | 406.209.0991 | www.jandsmt.com WE CARE ABOUT EVERYTHING WE DO

DEPARTMENTS

TRAILHEAD

22 R EAD: Holding Fire reckons with the West’s bedrock of violence

22 R EEL: Wild Life braids love, conservation and culture

23 EVENT: Wildlands brings Grammy-winning artists to the stage of conservation

24 CAUSE: Big Sky’s pay-what-you-can art classes build community

25 V ISIT: Legacy Bike Park is northern Montana’s new playground

OUTBOUND GALLERY

31 Community in Context: Putting three Montana towns in perspective

ADVENTURE

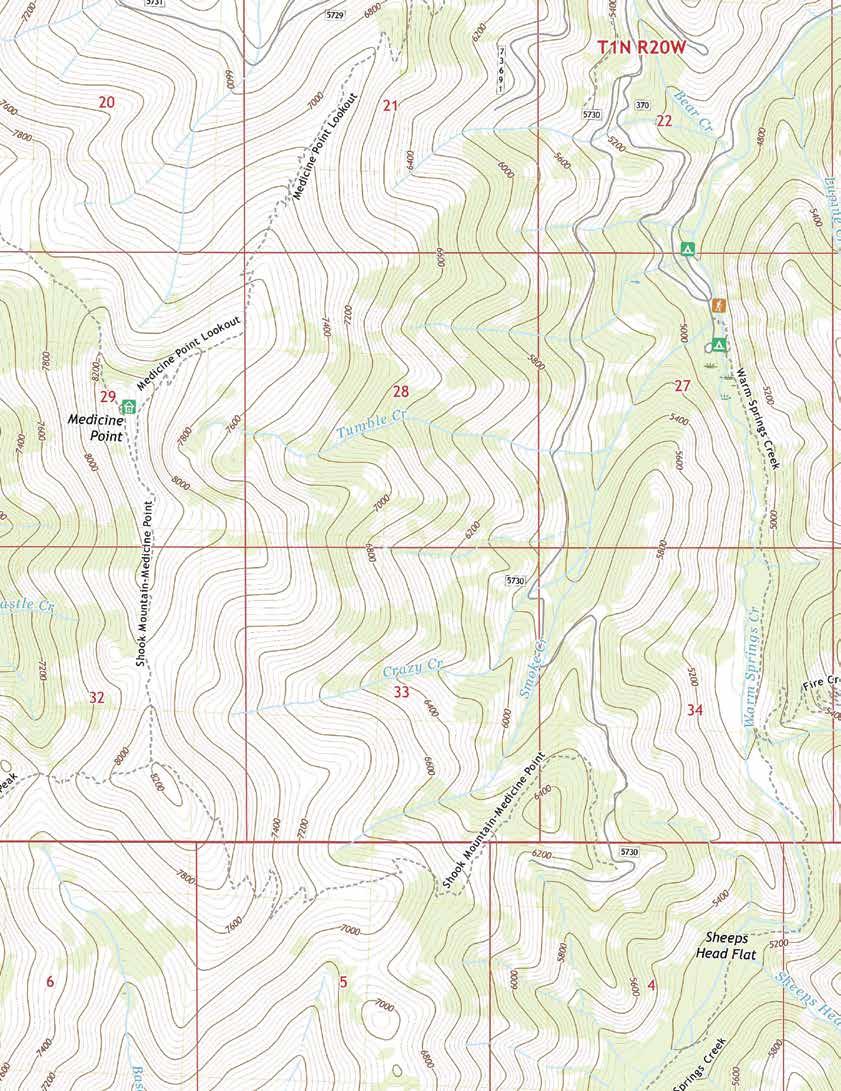

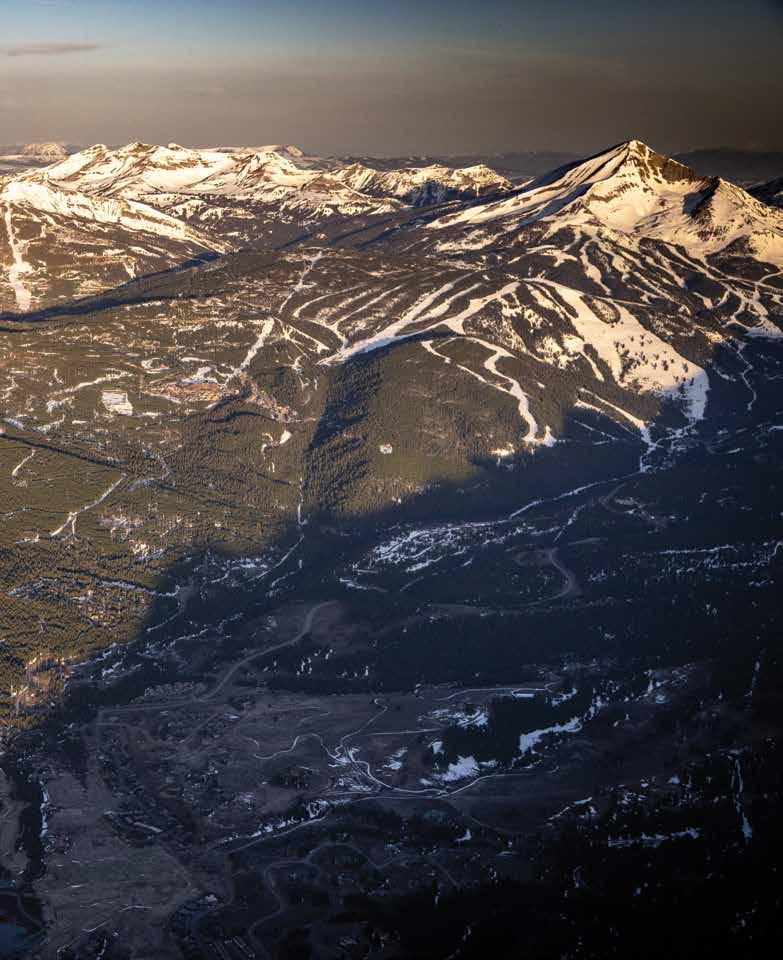

60 A Tale of Two Treks to Montana’s Medicine Point Lookout

66 Running the Grand Canyon, rim to rim to rim

68 Two women (and one dog) embark on an iconic 3,000-kilometer traverse

ROOTS

78 A Cooke City conference revives the rough and rugged Ernest Hemingway

86 Branding in Montana

90 Montana’s Williams family and a legacy of service

ENVIRONMENT & OUTDOORS 102 Grizzlies confront Endangered Species delisting 112 Building connection—and bike trails—in Big Sky 117 Thirty years protecting the Yellowstone to Yukon wildlife corridor 122 A community of river people SOCIETY 135 An outlook on Montana’s news landscape 142 A city boy’s introduction to the West 146 Turning waste into gold FEATURED OUTLAW 152 Conrad Anker reflects on community LAST LIGHT 168 Northern Lights

12

Montana artist Satsang performs in Big Sky, Montana, in June 2022 at Music in the Mountains. The first concert in the free summer series was a celebration of late Big Sky community members Mark Robin and Eric Bertelson, who both passed away from ALS. The annual event, known as Soulshine, gathers visitors and locals alike to remember these impactful people, and to celebrate community.

13

Photo by Gabrielle Gasser.

“WE’LL KNOCK OUT YOUR FLOORS IN 1 DAY” koconcretecoatings.com SCAN HERE FOR MORE INFO

15 406.993.6949 | bigskynaturalhealthmt.com | 87 Lone Peak Dr, Big Sky, MT Owned and operated by Dr. Kaley Burns, ND, Big Sky’s Only Naturopathic Doctor WHAT’S MORE IMPORTANT THAN YOUR HEALTH? Schedule Your Appointment Now! PRIMARY CARE NUTRIENT & REGENERATIVE IV THERAPY WELLNESS & NUTRITION

Owned and published in Big Sky, Montana.

PUBLISHER

Eric Ladd

MANAGING EDITOR

Bella Butler

ART DIRECTOR

Robyn Egloff

PRODUCER

Mira Brody

COPYEDITOR

Carter Walker

ASSISTANT EDITOR

Tucker Harris

ART PRODUCTION

ME Brown

Trista Hillman

Corey Ellbogen Beans

VIDEO DIRECTOR

Michael Ruebusch

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS

SALES & ADVERTISING

Ersin Ozer

Patrick Mahoney

Sophia Breyfogle

ACCOUNTING

Sara Sipe

Taylor Erickson

CHIEF MARKETING OFFICER

Megan Paulson

COO, VP FINANCE

Treston Wold

VP DESIGN & PRODUCTION

Hiller Higman

DISTRIBUTION

Ennion Williams

Mark McMann

Visit outlaw.partners to meet the entire Outlaw team.

featured contributors

Jason Bacaj, Amaya Cherian-Hall, Matt Crossman, Maria Lovely, Jeremy Lurgio, Christine Nichol, Benjamin Alva Polley, Jack Reaney, Bay Stephens, Dennis Swibold, Toby Thompson, Heather Waterous

CONTRIBUTING PHOTOGRAPHERS/ARTISTS

Tom Attwater, Dorothee Brand, Tristan Brand, Jake Burchmore, Chris Boyer, Amaya Cherian-Hall, Hazel Cramer, Frederick Coubert, Seth Dahl, Tom Fries, Gabrielle Gasser, Kyle George, Toni Greisbach, Aerin Jacob, Claire Jarrold, Maria Lovely, Jeremy Lurgio, Jim Peaco, Micah Robin, Stephen Simpson, Bay Stephens, Kent Sullivan, Madeline Thunder, Heather Waterous, Kenny Wilson

Subscribe now at mtoutlaw.com/subscriptions.

Mountain Outlaw magazine is distributed to subscribers in all 50 states, including contracted placement in resorts and hotels across the West. Core distribution in the Northern Rockies includes Big Sky and Bozeman, Montana, as well as Jackson, Wyoming, and the four corners of Yellowstone National Park.

To advertise, contact Ersin Ozer at ersin@outlaw.partners or Patrick Mahoney at patrick@outlaw.partners.

OUTLAW PARTNERS & Mountain Outlaw

P.O. Box 160250, Big Sky, MT 59716 (406) 995-2055 • media@outlaw.partners

© 2023 Mountain Outlaw Unauthorized reproduction prohibited

Check out these other outlaw publications:

ON THE COVER World-renowned alpinist Conrad Anker tops out on a climb in the Gallatin Canyon on May 13, 2023. This issue's Featured Outlaw, Anker reflects on a career in the climbing community and the lessons it has to offer. Read more on p. 152.

Jake Burchmore

The Language of Belay | p. 152

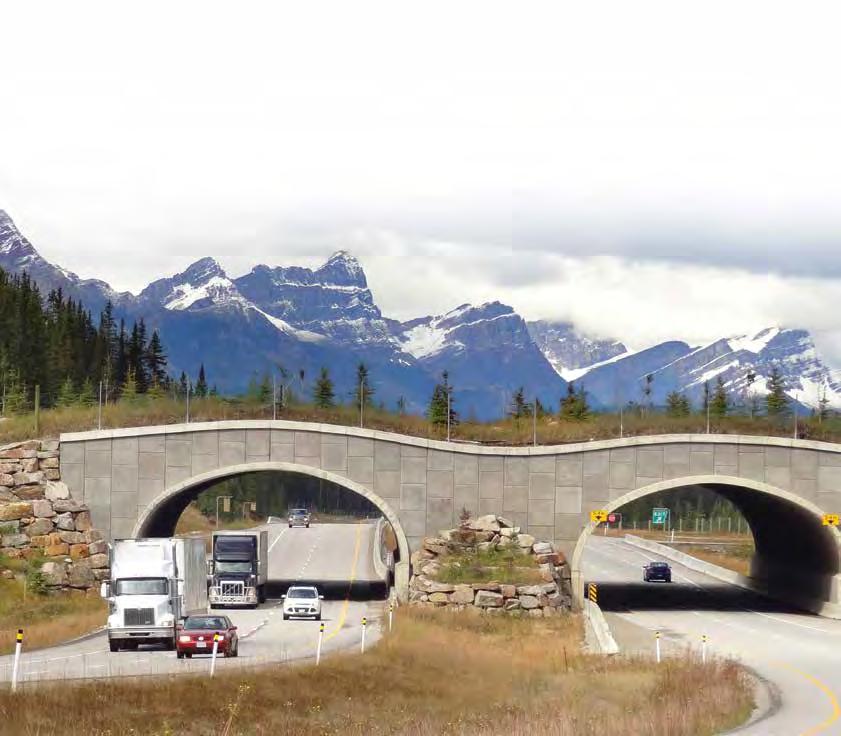

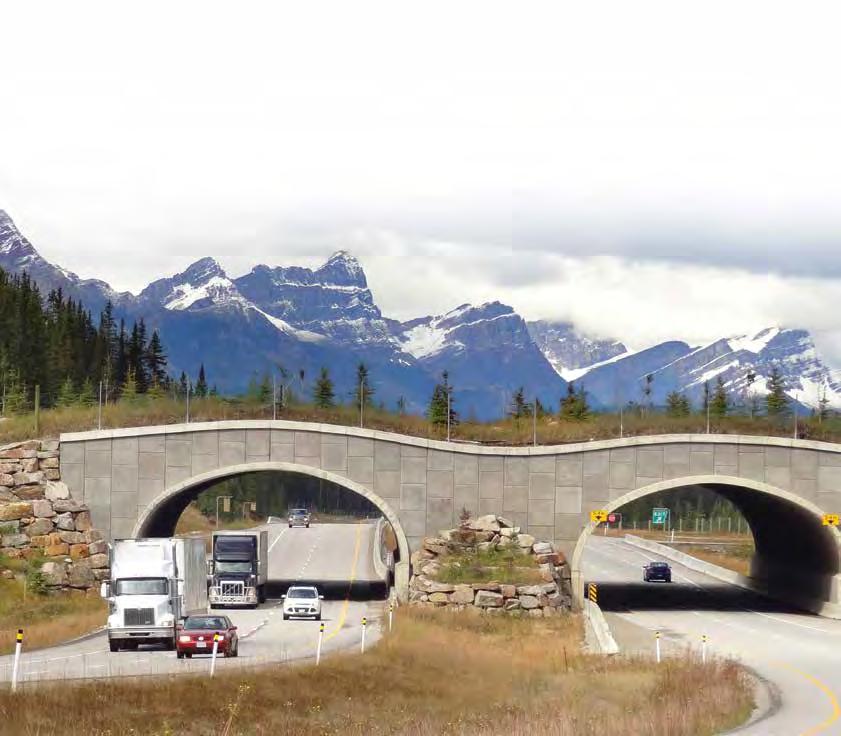

Jake Burchmore is a mountain lover, skier and photographer/ filmmaker based in Bozeman, Montana. He grew up in Telluride, Colorado, where he developed a passion for the outdoors and protecting the environment. As an artist and storyteller, Burchmore aims to captivate and inspire audiences toward positive change. Burchmore is a member of the Protect Our Winters Creative Alliance.

Maria Lovely

Lending a Hand | p. 86

Maria Lovely is a rugged, charismatic sixth-generation Montanan. She grew up in the mountains, attended school in a one-room schoolhouse, and still today spends every moment she can in the outdoors.

Hazel Cramer

Outbound Gallery: Communities in Context | p. 31

Hazel Cramer is entering her career as a documentary photographer and videographer. Passionate about raising awareness for humanitarian issues and underserved communities, she approaches her work with empathy and a critical eye. She was born in Seattle and graduated with a bachelor’s in multimedia journalism from the University of Montana. She lives in Bozeman with her roommates and plays outside as much as possible.

Benjamin Alva Polley

The Arena of Challenge for Grizzlies | p. 102

Benjamin Alva Polley is a placebased storyteller with stories published in Outside, Adventure Journal, Popular Science, Field & Stream, Esquire, Sierra, Audubon, Earth Island Journal, Modern Huntsman, and other publications at his website, benjaminpolley. com/stories. He holds a master’s in environmental science and natural resources journalism from the University of Montana.

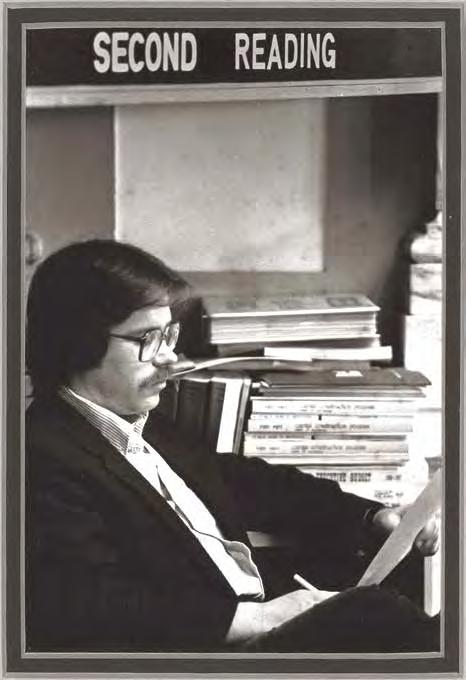

16

from the editor

THE THINGS WE HOLD TOGETHER

You may be hearing the word community a lot these days. Especially in this post-pandemic world of new norms, we lean on this word in our adopted vernacular of resilience. But how could nine little letters fully grasp the complexity of such an innate and essential thing? Community is derived from the Latin communis, or “in common.” Certainly, community is about the things that make us alike: where we live, how we spend our time, how we identity ourselves. But it encompasses more than that.

When simple words fail us, I tend to seek the thoughts of our time’s greatest ponderers. I think author Terry Tempest Williams got it right during a 1995 radio interview:

“I think community is a shared history, it's a shared experience,” she said. “It's not always agreement. In fact, I think that often it isn't. It's the commitment, again, to stay with something—to go the duration. You can't walk away. It's like a marriage, only I think it's more difficult to divorce yourself from community than it is to a human being because the strands are interconnected and so various.”

What Tempest Williams’ words illuminate is that community is not the things we hold in common but rather the things we hold together. As she put it, it’s not just what we agree on, and “often isn’t,” but rather the intrinsic threads that join us together to carry the world’s paradox of weight and beauty. We can’t carry this on our own.

I got to witness this when we spent time with world-renowned alpinist and Bozeman local Conrad Anker, who we’re privileged to have as this issue’s Featured Outlaw (p. 152). Tucked back

in a primitive corner of the Gallatin Canyon, Anker spent the day attached by a rope to Manoah Ainuu, an up-andcoming climber from Washington who also lives in Bozeman. Anker is nearly 30 years Ainuu’s senior, and they each came to climbing byway of their own distinct paths. And yet, they are bound by such threads, united in a community that is founded in collaboration and support.

The stories that you hold here in your hand grasp the meaning of community that’s hard to explain, but so knowable in our bones. Benjamin Alva Polley touches on what community demands of us when we do not agree in his examination of a forthcoming decision on removing the iconic grizzly bear from the Endangered Species list (p. 102). Similarly, sixth-generation Montanan Maria Lovely writes about the things that bring us together in her piece on branding in rural Montana (p. 86): ritual, and how “in the act of serving, you lose sight of greed and ego.”

When we take time to feel for them, we are reminded of these interconnected strands that tie us to community. In his story River People (p. 126), our publisher Eric Ladd recounts a lifetime spent on rivers, and how these bodies of water have built his community—and keep him connected.

The stories in this publication do what a simple word can’t; they reflect the fullest expanse of community. They inspire us to engage with it; to build it, to lean on it, to appreciate it. I love story for this reason, and I love this issue for this reason. We hope you do, too.

With humble gratitude to our Mountain Outlaw community, thanks for reading.

Bella Butler Managing Editor

17

18 NATURAL. SUSTAINABLE. HEALTHY. SHOP & EXPLORE MEMBERSHIPS AT REGENMARKET.COM BISON · BEEF · LAMB · PORK · POULTRY DRY GOODS · FROZEN MEALS LOCAL GRASS FINISHED & PASTURE RAISED FRESH MONTANA FOOD, DELIVERED TO YOUR DOOR. Free 30 d ay trial!

ARROW RANCH |

$38,514,500 | 14,982 ± acres

Explore

SHIELDS

$10,995,000 | 283 ± acres

Montana land for sale surrounded by breathtaking scenery, abundant resources, and diverse wildlife.

SPRING

$5,300,000 | 313 ± acres

If you are thinking of selling, buying, or just want to get our thoughts on the current real estate market, contact a member from our Bozeman office at your convenience.

$2,675,000 | 20 ± acres

19

the best

WWW.FAYRANCHES.COM | 800.238.8616 | INFO@FAYRANCHES.COM

BIG HOLE RIVER RETREAT | Melrose, MT

FAMILY FARM | Belgrade, MT

RIVER LODGE | Clyde Park, MT

Wisdom, MT

Stay Safe in Bear Country! Your bear awareness resource. Retail store & bear spray rentals. HEYBEAR.COM 11 Lone Peak Drive, Unit 104 Big Sky, MT 5973 LEARN MORE A BOUT OU R MISSION

STRAIGHT UP WHISKEY FROM A STRAIGHT UP PLACE. MontanaWhiskeyCo.com Enjoy responsibly.

TRAILHEAD

This summer we invite you, our readers, to experience community in the Rocky Mountain West through art and life. At this Trailhead, we point you in the direction of various mediums through which to experience our home, from films and books to nationally recognized events. Happy trails. —The Editors

Holding Fire: A Reckoning with the American West

To fully acquaint ourselves with the identity of our communities, we must intimately know their pasts. And to be a true member of these communities, sometimes we must challenge the narrative enforced by those pasts. In his 2023 memoir Holding Fire: A Reckoning with the American West, esteemed Montana author Bryce Andrews writes of his experience doing just that after he inherited his grandfather’s Smith & Wesson revolver, an event that forced him to confront the bedrock of violence which serves as the historical foundation for the iconic American West we know today: violence against wildlife, wilderness and the Indigenous peoples who have called the West home since time immemorial.

In honest prose, Andrews’ silver tongue creates a captivating narrative that is poignant in a time when the nation at large battles an epidemic of gun violence. In tandem with critique, the former Seattleite-turned-Montana-rancher explores how the West’s identity can evolve, and how its legacy doesn’t have to impede our ability to live better with the land and with each other.

Wild Life

As we as a species face the peril we’ve imposed on our planet’s wild spaces and their inhabitants, Oscar-winning filmmakers Jimmy Chin and Elizabeth Chai Vasarhelyi present a story about the fight for such places. An ode to the love story between conservationists Kris and Doug Tompkins, this National Geographic film, released in April, chronicles the former outdoor industry moguls’ departure from brand work to pursue the founding of several national parks in Argentina and Chile.

“On any scorecard, nature is losing,” Kris says in the film. Wild Life is an honest look at the couple’s quest to change that, and Kris’ perseverance in the wake of Doug’s death.

films.nationalgeographic.com/wild-life

22

Wildlands Festival

Community is one of the greatest catalysts we can summon for inspiring change, a truth that exists at the heart of the Wildlands Festival. Produced by Outlaw Partners, which publishes Mountain Outlaw, the festival joins people from near and far around Montana’s precious Gallatin River for three nights of live entertainment that will invigorate the Wildlands community with a passion to preserve the wild places outside that make us feel alive inside. This year it aims to serve as the largest-ever conservation effort for our life-giving rivers. The Wildlands Festival presents a lineup that supersedes anything else offered in the region. This summer, in its third year, the festival presents headliners Foo Fighters, Lord Huron and The Breeders, on stage on Aug. 5-6, and a charity dinner featuring actor Tom Skerritt, and comedians Orlando Leyba and Forrest Shaw on Aug. 4.

At the intersection of the 30th anniversary of Academy Award-winning film A River Runs Through It and the 50th anniversary of the highly influential river conservation organization American Rivers, Wildlands benefits American Rivers and the Gallatin River Task Force in their collective fight to save the Gallatin.

Produced in partnership with actor Tom Skerritt, Wildlands will by and large be the event of the summer, with an impact far transcending the three-day festival.

wildlandsfestival.com

23

TRAILHEAD

The Arts Council of Big Sky: Pay-what-you can art program

Amid sprawling development and high-tech chairlifts and recreation, resort towns are adding components to their communities that address liveability for the people working day and night to make the wheels turn. Among second homes and new hotels, affordable housing begins to pop up, and social services like food banks and behavioral health support are smattered between après parties and 12-hour shifts. In the community of Big Sky, one nonprofit is taking such offerings beyond basic needs, providing experiences that spark joy and inspire creativity.

The Arts Council of Big Sky last year launched the only pay-what-you-can art education program, which in its first year saw 1,000 registrations for classes spanning from pottery to woodburning. According to Arts Council Art Education and Public Director Megan Buecking, the program takes advantage of the unique economic structure of Big Sky that includes both people and funding mechanisms with deep resources as well as a population of people that benefits from supported opportunities. The program’s classes all advertise a suggested fee that covers operating costs for the class, but students have the option to pay more if they can—or less if they can’t. Because the class is available to everyone, not just the workforce, Buecking says it also builds community by introducing folks that otherwise might not interact in a peer-to-peer way outside of the studio.

Though the program is young, Buecking believes it has the opportunity to be scaled to other similar communities.

The Arts Council’s art education program is largely supported through donors and awards. Visit bigskyarts.com/give to learn more or support the effort.

24

Legacy Bike Park

A true homegrown dream come to life, Legacy Bike Park opened in 2021 on 175 acres near Lakeside in northwest Montana. The first of its kind in that region, the downhill bike park is gaining popularity, but daily capped ticket sales allow for a personal experience in a stunning landscape. With trails by Terraflow Designs that span all skill levels, the bike park is as much art as it is playground. Cut through a rustic evergreen basin, the flowy trails are designed with intention, built on the north side to keep the dirt cool and damp.

Legacy’s owners describe the young venture as being “in its infancy,” with more trails and offerings to come as the park continues to grow. Located in Montana’s beautiful Flathead County, the park also offers camping.

On any given day during the season, the park embodies community around sport, with riders high-fiving and swapping trail stories on the shuttle back up the hill. Legacy also epitomizes the sweet spot that captures recreation in Montana: five-star terrain with a personal, small-town feel.

legacybikepark.com

25

BLUE RIBBON LIVING

Introducing e Dri at North Forty. Twenty four residences in the storied town of Ennis, Montana— just minutes from the best shing and recreation opportunities that Montana has to o er.

26

THEDRIFTRESIDENCES.COM

NEW LUXURY RESIDENCES

Cortina perfects the shared culture of pasta making, Italian craft, heritage chops and worldly wines around the warm hearth of an Italian steakhouse. Open daily, visit us at Montage Big Sky. For reservations, call 406-993-8142. MontageHotels.com/BigSky | 995 Settlement Trail | Big Sky, Montana Exceptional Epicurean Experiences, Warm Montana Hospitality.

28

LETS TALK.. Make the most of your summer with a relaxing getaway at our resort. A Montana vacation unlike any other, the Rainbow Ranch Lodge combines the rustic Wild West with classic elegant sophistication; a place where exceptional food, wine, and accommodations are our passion, and hospitality is instinctive. Welcome to our little paradise on the banks of the Gallatin River in Big Sky, Montana. www.RainbowRanchBigSky.com 42950 Gallatin Rd Gallatin Gateway MT 59730 406.995.4132 EXPLORE THE QUIET SIDE OF BIG SKY

RAINBOW RANCH LODGE

29 Devotion to your experience Precision in craft Design Build Project Management Client Representation bindinteriors.com 406.813.8381

Mastering The Art of 3 MPH

BE ADVENTUROUS | BE PRESENT | BE INSPIRED

5 Night + 6 Day

Premier Rafting Trips

Middle Fork Salmon River, Idaho

boundaryexpeditions.com

OUTBOUND GALLERY

LAME DEER // 32

ANACONDA // 38 BIG SKY // 44

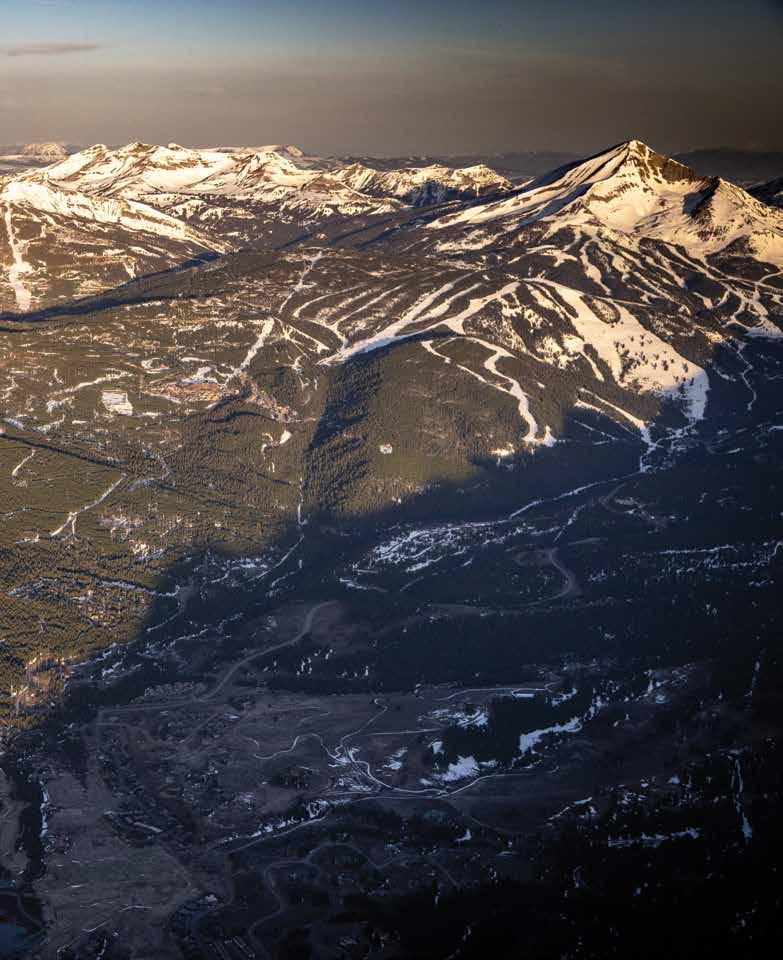

Like people, communities are characters. They are defined by identity, history, adversity and place. And like people, we acquaint ourselves with communities through reputation, a brief meeting or meaningful time spent together. In this gallery, Bozeman-based pilot and photographer Christopher Boyer introduces us to three distinctly unique Montana communities through an aerial view captured from his 1956 red Cessna plane. Upon first glance, we gain information about these places; we put them in context: What natural features surround them? What relics of history are they built around? How do the built communities interact with the landscape they exist within?

Through photojournalist Hazel Cramer’s work, we’re then afforded a more intimate experience in these communities. Who are their members? What are their challenges? What does their resilience look like? What are their identities?

This issue, we invite you to explore these portraits of Lame Deer, Anaconda and Big Sky and acquaint yourself with a visual take on community.

–The Editors

–The Editors

31

32

LAME DEER

The Northern Cheyenne Reservation, one of the seven in the state of Montana, was established in 1884. Nestled in its hills on the edge of Montana’s eastern plains sits Lame Deer. Evidence of systemic racism and cultural genocide is planted throughout the community, which continues to deal with daily hardship as a result. And yet, this place is a generational home that breeds community, connection and a love for the land.

33

Photo by Christopher Boyer

Above: Teanna Limpy, Northern Cheyenne’s culture and resource preservation officer, sits at her desk in Lame Deer, Montana. “There’s a saying that the land we have today was fought for. The literal blood of our people,” Limpy said. “This land has provided everything for us, it’s always been a cherished part of our homeland.”

Left: This U.S. Federal Government building is on the north side of Lame Deer. “Lame Deer is our biggest district,” Limpy said. “It’s the economic hub of the reservation.”

34

35

Above: Lynette Two Bulls stands in the early spring educational garden of the Yellow Bird Lifeways Center (YBLC). The YBLC, founded in part by Two Bulls, is a nonprofit organization focused on reciprocity for its community. The educational garden is a part of their food sovereignty program.

Right: Two Bulls holds sacred Northern Cheyenne heirloom corn in the YBLC greenhouse. “I think it’s really important for our community to come together to heal, and now science is catching up with what our people always knew- that the land heals us,” Two Bulls said.

Above: Arlene Rogers (front) and her daughter, Danielle Shotgunn, lost their son and brother, Shane Shotgunn, to alcohol abuse. The wall of photos behind them is to remember him. "He was so friendly,” Rogers said. “He would strike up a conversation with anyone, even strangers.”

Above right: Trash and other debris surround a burnt vehicle alongside a residential street in Lame Deer, Montana. "The Majority of us who live here live in poverty," Rogers said on April 18, 2023.

36

37

Right: Vikki and Troy Cady own the Flower Grinder, the only coffee or flower shop in a 25-mile radius. During the pandemic, Vikki kept a record of all the events she prepared flowers for. "I ended up doing about 120 funerals that year," she said.

38

ANACONDA

A child of the Anaconda Copper Mining Company of the late 1800s, Anaconda, Montana, is both a place petrified in its history and fertile with new opportunity. The community is a patchwork of a predominantly older demographic with young entrepreneurs and families woven in. While relics like “The Stack” (top left) remain as a museum of the town’s past, new shop fronts and new faces indicate the community is undergoing an identity shift.

39

Photo by Christopher Boyer

Smelter City Brewing, Anaconda’s only brewery, opened in 2017. “It was one of the first new ‘Happenin’ Businesses’,” said Matt Johnson (featured on the following page). “It gave us, the newer folks, somewhere to go.”

40

Straight streets and homogeneous housing characterize the town. Anaconda was a pre-planned city, built in the early 20th century with the purpose of running the smelter, so the houses east of Main Street look like this to accommodate more workers.

41

42

Far left: Born and raised in Anaconda, Nicole McDonald, 29, rolls silverware at Firefly Cafe, a place where customers and employees know each other on a first-name basis. “I would stop to chat some more, but I get paid to work, so I gotta keep working,” McDonald joked. “I have to get my money if I want to get out of this town someday.”

Left: Kim Magnusson, who has lived in Anaconda for 20 years, stands in the kitchen of her bar, Carmel’s Sports Bar & Grill. “Our community is mostly older people since the smelter closed,” Magnusson said. “The younger people move away when they get old enough because there’s nothing to offer them.”

Far left: Matt Johnson and his wife, Emily Adams (not pictured), moved to Anaconda in 2019 and opened their bike shop in April 2022. “The community is changing from when I first recognized it 10 years ago,” Johnson said. “The town seemed sleepier and quieter… just not like the outdoor recreation place that it’s turning into.”

Left: Logan Dublin is starting a new life in Anaconda. She just completed her second job interview since moving from Colorado last week. “It’s definitely small-town vibes,” she said on April 19, 2023. “At first, I was a little nervous, but everyone has been really welcoming.”

43

BIG SKY

Founded by famous newscaster Chet Huntley in 1974, Big Sky, Montana, was established with the intention of creating opportunities for people to enjoy wide open spaces and experience the mountains. Today, Big Sky is an increasingly popular tourist destination and second (or third) home location. And yet, the town is also a community, home to longtime locals, eager newcomers and seasonal workers. As the demand for a piece of this paradise climbs, so does the cost of living, and striking the balance between economic growth and livability becomes somewhat of a white whale.

44

45

Photo by Christopher Boyer

when we were growing up here, and now that’s not necessarily the case.”

Right:

a complex of high-end condominiums and penthouses, is being built in Town Center, one of Big Sky’s distinct areas. According to the development’s website, short-term rentals will be allowed in the building, and the average unit price is $2.76 million.

46

Above: Ethan Schumacher (left) and Holden Samuels are geared up for some spring turns at the Beehive Basin trailhead. “Big Sky has changed a lot,” Samuels said. “Literally everyone knew everyone

The Franklin Residences,

Ben Bonesho stands in the back room of East Slope Outdoors, a gear and rental shop where he works. “The main issue here is housing,” Bonesho said. “I know people, like our other manager, that drive an hour and a half to come work here.” According to the Big Sky Chamber of Commerce, 50% of the workforce commutes from other towns.

47

Right: David O’Connor is the executive director of the Big Sky Community Housing Trust (BSCHT), a nonprofit that identifies community housing challenges and seeks to address them. Big Sky is unincorporated, meaning there is no organized local government to fulfill such services. Instead, it is run by a network of special districts and nonprofits, like BSCHT. “We’re such a young community, there was no mining town here first,” O’Connor said. “So we have a great opportunity to decide our values and identify what it means to be from Big Sky.”

Below: Daniel Bierschwale, executive director of the Big Sky Resort Area District, addresses a crowd at the groundbreaking event for a new long-term rental workforce housing development. The construction of Riverview Place started on May 3, 2023.

48

49

Hazel Cramer is a documentary photographer and videographer based in Bozeman, Montana. She acknowledges her previous status as a guest on Northern Cheyenne land, and says a special thank you to Ȟokšilá Šahíyelá íčíčaǧá Mesteth for his help with this story.

Christopher Boyer is a commercial pilot and photographer flying survey, mapping and photography projects throughout the Northern Rockies and Great Plains.

Signs of Montana employees Micah Harvey (top left) and Wyatt French install the official sign on Cowboy Coffee’s new Big Sky location. The business, which started in Jackson, Wyoming, opened its second walk-in coffee shop in 2023 and is among many new businesses to move into Town Center.

Analytical cannabis testing that you can trust.

Montana family, and female, owned and operated. Fidelity Diagnostics specializes in advanced THC, Terpene and Contaminant compliance testing. Consistent and reliable sampling services from our exceptional Field Technician team. Laboratory integrity that you can trust.

50

GROW WITH FIDELITY | fidimt.com

Season-spanning, all-conditions gear built to outperform and outlast. FLAGSHIP STORES Bozeman, MT Pagosa Springs, CO SHOP VOORMI.COM EMBRACE THE ELEMENT™ Sun Protection Moisture Wicking Quick Drying Water Resistant CHALET PULLOVER

RIVER RUN HOODIE

THE FUTURE OF CLOTHING

V1 RAIN JACKET

From High Desert, high altitude and the coast,

Voormi’s tech-textiles Embrace the Element

Words by

It’s a Yosemite spring like the park rarely sees. Record snowpack in the Sierra Nevada and warming temps have released a torrent of water. The runoff gushes from the valley’s rim down both its famous waterfalls and new unnamed ones, pushed down crevasses and over cliff edges by the unrelenting force of gravity. The infamous Yosemite Falls sounds like a semi trailer lumbering down an interstate, the water eager to plunge into the Merced River below.

The anomalous snow year in the West is giving way to an intensely wet season of rebirth—one my partner Kenny and I have been fortunate to witness as we pass through the lower Rocky Mountains, red rock deserts, High Sierra and lush green and redwood-specked coast. From the 111 degrees we felt in Death Valley, to snowfall in Yosemite, to the dry 85 in the Grand Canyon and dense fog of the Mendocino Coast, we’ve both shivered and sweated, sometimes in the span of two hours and 200 miles.

On a trip of extremes, you wonder what kind of gear to pack without bringing a caravan to it. Truth is, I’ve been wearing Voormi® clothing for most of it. Between driving from Alabama Hills outside of Lone Pine, California, where high-desert temps and flowers were in full swing, to reaching the High Sierra and arriving during a late-season snowstorm in Yosemite Valley, I was comfortable with my minimal repertoire of their Easy Tank paired with the Chalet Pullover and knit beanie to stave the chill the dense coastal range clouds brought in.

That’s because Voormi as a company was founded on similar principles. Not only rooted in the region that contains the highest concentration of 14ers in the Lower 48, Voormi’s founders are outdoors people, guides and

mountaineers. In fact, the idea for minimal but heavy-lifting clothing was inspired by a guide trip through Alaska.

Their River Run Hoodie base layer kept me warm when wind chills in Moab, Utah, dipped below 30 degrees, but also kept me cool when the sun rose above the red monoliths of Zion National Park to kiss the morning with warmth. Their Short Sleeve Tech Tee dried me when, in my haste to take my first shower in after five days, I had forgotten a towel. In all cases, it’s a t-shirt that goes beyond simply covering my body in moderate temperatures and has instead pulled its weight on trail runs filled with sunshine and red rock dust and even to that post-run beer by the fire.

Voormi’s home base is in a remote, rugged town nestled in the San Juan Mountains of Colorado just over Wolf Creek Pass, where mountain pursuits are a little more extreme and the people tougher. With stores in Pagosa Springs, Colorado, and Bozeman, Montana, Voormi takes pride in producing a lifestyle-backed brand of clothing that is tough, tactical and looks great doing it all.

Voormi’s team thrives on the foundation of an

52

Sponsored Content

Mira Brody | Photos by Mira Brody & Kenny Wilson

industry-unique ethos: textiles are a technology that needs to progress like any other. The truth is, not much has changed since humans put a couple hides together to produce clothing over 10,000 years ago, something they’re working to change with the creation of Voormi’s proprietary CORE CONSTRUCTION® and other patented textile technologies. Uniquely, Voormi's CORE CONSTRUCTION® allows the ability to insert advanced functional materials into the center of fabric - from integrated weather protection to printed electronic circuitry. This patented process changes the game when it comes to breakthrough performance in textiles, and when worn, remains comfortable and excels in extreme conditions.

Take the High-E Hoodie for example—it includes Voormi’s Surface-Hardened™ technology and is made with a durable 21.5 micron wool reinforced by an array of outer-facing nylon fibers. Finished off with a durable water repellent coating, it becomes a multi-use backcountry staple built to work on its own, or layered with your favorite shell. Another great textile advancement in Voormi's fleet is its PHASE S.C.™ concealment technology. Phase S.C. is achieved by coloring the textile down to the yarn level instead of using surface-printed camo. This eliminates the “synthetic glow” common to hunting in sunrise and sunset conditions with traditional synthetic camo. With virtually unlimited uses, Voormi garments are cross functional in every sport, lifestyle and recreation type. These textiles work hard, are moisturewicking when you start to sweat, insulating when the temps drop, and water repelling when it starts to precipitate — meaning there’s no need to change layers when the weather does. Voormi’s clothing is the first and last pieces you’ll buy for every single type of element.

Kenny and I end our trip on California’s Pacific Coast before heading home to Montana and are greeted once again by an abnormal but healthy wet spring. The fog is dense and the ocean waves along the beautiful Sonoma Coast crash into the sand, sending sea spray into the already-humid air. Although it’s chilly, my Chalet Pullover is impenetrable, making this and each adventure before it feel less biting, and instead more refreshing than anything.

53

55 Tell your Montana story with PureWest. PUREWESTREALESTATE.COM Behind every move is a story. We’ll help you with the next chapter. Behind every move is a story. We’ll help you write yours. 88 Ousel Falls Road, Suite B | Big Sky, MT 59716 406.995.4009 | www.BigSkyPureWest.com

56 eralandmark.com Robyn

Each office independently owned and operated.

Erlenbush, CRB, Broker/Owner.

3 BEDS | 2.5 BATHS | 22.5 ACRES | BOZEMAN | $1,950,000 MLS# 380760 | Chelsea Stewart 406-579-0740

3 BEDS | 3.5 BATHS | 2,482 SQ FT | BOZEMAN | $1,495,000 MLS# 380757 | Hannah Comaratta 406-589-2732

3 BEDS | 2.5 BATHS | 1,653 SQ FT | LIVINGSTON | $479,000 MLS# 380763 | Gillian Swanson 406-220-4340 & Sarah Swanson 406-220-2045

Bozeman, Big Sky, Livingston & Ennis, Montana

Specializing in making Montana dreams come true since 1976. Ready to follow your dream?

5 BEDS | 5 BATHS | 3,878 SQ FT | BIG SKY | $2,990,000 MLS# 380923 | Dan Delzer 406-580-4326

ESCAPE TO

PARADISE

We’re not sure a more perfect combination exists – adventures by day across Paradise Valley, followed by the comforts of Sage Lodge by night. With Sage Lodge as your basecamp, you can enjoy fly fishing on the Yellowstone River, private spring creeks, or in nearby Yellowstone National Park. And while Paradise Valley is known for its abundant, blue-ribbon waters, there’s also more to enjoy at Sage Lodge. Grab a hearty Montana-inspired meal in the Fireside Room or The Grill, pamper yourself at The Spa, and kick back with a cocktail on the patio while taking in breathtaking views of Emigrant Peak.

VISIT SAGELODGE.COM OR CALL 855.400.0505.

Sage Lodge Drive, Pray, MT 59065

55

58

Jeremy Lurgio and his family trekked to the historic Medicine Point Lookout in the Bitterroot Mountains two years in a row during the lookout’s opening summer week. The photo essay on page 60 juxtaposes the family’s two adventures through drastically different landscapes due to the fickle nature of Montana mountain weather.

Jeremy Lurgio and his family trekked to the historic Medicine Point Lookout in the Bitterroot Mountains two years in a row during the lookout’s opening summer week. The photo essay on page 60 juxtaposes the family’s two adventures through drastically different landscapes due to the fickle nature of Montana mountain weather.

ADVENTURE A TALE OF TWO TREKS // 60 DOWN IS OPTIONAL UP IS MANDATORY // 66 100 DAYS FROM YELLOWSTONE TO THE YUKON // 68 59

Photo by Jeremy Lurgio.

A Tale of Two Treks

A lesson in Montana adventures, from one summer to the next

Words

Words

and Photos by Jeremy Lurgio

She wanted to wear her snow boots.

She insisted. She didn’t care it was the last day of June. She didn’t care the climb to the fire lookout was 2,000 vertical feet over 3.5 miles. She was steadfast about the snow boots.

If you know anything about 7-year-olds, they can be particular and stubborn about attire. Our Amelia was no different. Gold cape with colorful ski socks on Monday, sure. Michael Jackson-style red leather jacket with striped socks and polka dot shorts on Tuesday, okay. Shorts for every sub-freezing day of the year, fine. As parents we try our best to teach our kids to be prepared, but we also kind of pride ourselves on our kids being Montana tough.

Yet against Amelia’s best judgment, as we prepared for our journey to the Medicine Point Lookout in the southern Bitterroot Mountains, my wife and I convinced our free-spirited daughter that comfortable sneakers were indeed the proper shoes for the hike.

The night before we left, a summer cold front blew through western Montana, bringing freezing temperatures and possible snow to the high country. With our backpacks geared up for an overnight adventure, we drove from Missoula to the trailhead near Sula, Montana. Based on the dusted snow line adorning the high peaks of the Bitterroots from Lolo Peak all the way to the range’s highest point at Trapper Peak, the weathermen had nailed it.

Three months into the pandemic, we were excited to have the first available night booked at the lookout, which is available from June 30 through early September. We pulled off Highway 93 and started up the dirt Forest Service road. As we drove higher, we could see the silhouette of the lookout perched on the 8,409-foot Medicine Point, which was blanketed in white. We knew there’d be some snow up top.

Packs on and dogs in tow, we started up the first third of the hike through a forest of Douglas fir and purple lupine. Our daughter and our 10-year-old son, Lachlan, had never stayed in a lookout, so excitement fueled the first leg. The sun was out and things were good.

Left: After hiking 3.5 miles through dirt, mud and snow, Amelia Lurgio slogs through 10 inches of snow on her way up the final ridge to the Medicine Point Lookout on June 30, 2020, the first day the lookout is available for overnight stays. Above: A year later, Lachlan and his dog, Awa, gaze toward a wildfire in the Sapphire Mountains while hiking Medicine Point. Topo maps courtesy of U.S. Geological Survey.

Right: During their first ever trip to a fire lookout, Amelia, left, and Lachlan, right, still shine smiles despite the adventurous 2,000 vertical feet climb to the lookout.

Below: A year later, Lachlan, left, and Amelia, right, don similar smiles during their second trip to the lookout. They carried a bit more weight in their backpacks and the weather was drastically different the second time around.

Top: Amelia trudges through deep snow in a final push to the 14-foot by 14-foot Medicine Point Lookout, which is perched on a 10-foot-tall tower at the top of Medicine Point at 8,409 feet. Bottom: Lachlan Lurgio looks out toward a smoky sunset as he hikes to the historic lookout, which has been restored to reflect a lookout of the 1940s.

Top: Amelia trudges through deep snow in a final push to the 14-foot by 14-foot Medicine Point Lookout, which is perched on a 10-foot-tall tower at the top of Medicine Point at 8,409 feet. Bottom: Lachlan Lurgio looks out toward a smoky sunset as he hikes to the historic lookout, which has been restored to reflect a lookout of the 1940s.

Top: After a wet, cold climb to Medicine Point, Lachlan, left, and his sister, Amelia, curl up in a sleeping bag together, happy for the shelter and warmth at the lookout. Bottom: A year later, Lachlan, left, and Amelia, play a game of Pass the Pigs after a sunny summer hike to the lookout. The lookout provides a vast 360-degree view of the surrounding mountains and wilderness.

Top: After a wet, cold climb to Medicine Point, Lachlan, left, and his sister, Amelia, curl up in a sleeping bag together, happy for the shelter and warmth at the lookout. Bottom: A year later, Lachlan, left, and Amelia, play a game of Pass the Pigs after a sunny summer hike to the lookout. The lookout provides a vast 360-degree view of the surrounding mountains and wilderness.

The second leg of the journey got slick and a bit muddy from the melting snow. By the time we reached the saddle below the last third of the climb, we could see the snow we had thought might be a dusting was indeed something heavier. Clouds shrouded the peak.

As we started up the last 500 vertical feet, 1 inch of wet snow became 3, and then pretty quickly, 6. Feet were wet. Feet were cold.

Amelia erupted with tears. “I told you I wanted to wear my snow boots,” she wailed. “My feet are so cold.”

“Yup, you were right, we were wrong,” I replied. “Let’s take a break and figure out a plan.”

I moved onward taking really small, 7-year-old stride length steps to pack down the snow so it didn’t get above her shoe cuffs. I joked that I’d rub her cold digits and I’d blow hot air on her stinky feet to keep them warm. And I did. Then we played the animal game where one person picks an animal and the others have to ask yes and no questions to solve the riddle.

Bolstered by gummies, energy bars, reassurance and the excitement for the warmth of the lookout, we managed to keep moving. In some places, the snow was 10 inches deep. My wife and I have spent a lot of time backpacking, backcountry skiing and mountain biking and have endured countless events of that oddly treasured Type Two Fun, but there was something special about sharing this misery with our family of four. As we built a fire in the stove, the kids nestled in a sleeping bag together. They gazed through the lookout’s windows with a 360-degree view for miles. In minutes, the siblings were laughing and giggling, the recent postholing forgotten.

We looked at maps, read about the history of the lookout and perused journal entries from past guests. The kids were in awe of this 14-foot by 14-foot shelter perched atop Medicine Point. There’s something primal, something instinctual, that happens when setting up camp in a remote place; I feel deeply grounded as the exhilaration of wild places blends with the calmness of sanctuary.

By nightfall we all joked that we had to do this again next year, and we did. But true to the fickle nature of weather in Montana, a year later we hiked to the lookout on a 70-degree day; the distant ridges weren’t blanked in white snow, but instead shrouded in early wildfire smoke. Despite this classic Northern Rockies juxtaposition, the wildness remained, as did the beautiful rustic sanctuary.

This photo essay is a comparison of two trips, nearly a year apart, to the remarkable Medicine Point Lookout.

Jeremy Lurgio is a freelance photographer and filmmaker based in Missoula, Montana. He is also a professor of photojournalism and multimedia storytelling at the University of Montana School of Journalism. In his downtime he enjoys skiing, mountain biking, cyclocross racing, fly fishing and exploring the wilds of Montana with his family and dogs.

Top: The fire in the lookout’s woodstove provides heat to dry wet socks, boots and sneakers, but it also provides some muchneeded warmth for Lucky, one of the family’s two dogs.

Middle: Caroline, Lachlan, Amelia and Jeremy pose for a selfie halfway between the trailhead and the Medicine Point Lookout.

Bottom: Jeremy, Amelia, Caroline and Lachlan pose for another selfie a year later. This time not in winter gear, but in t-shirts and shorts.

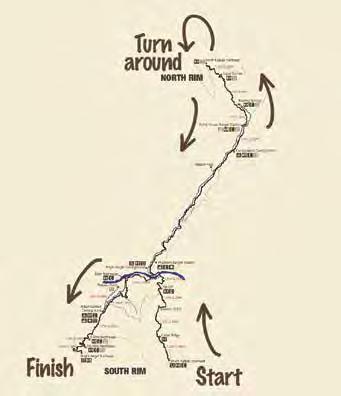

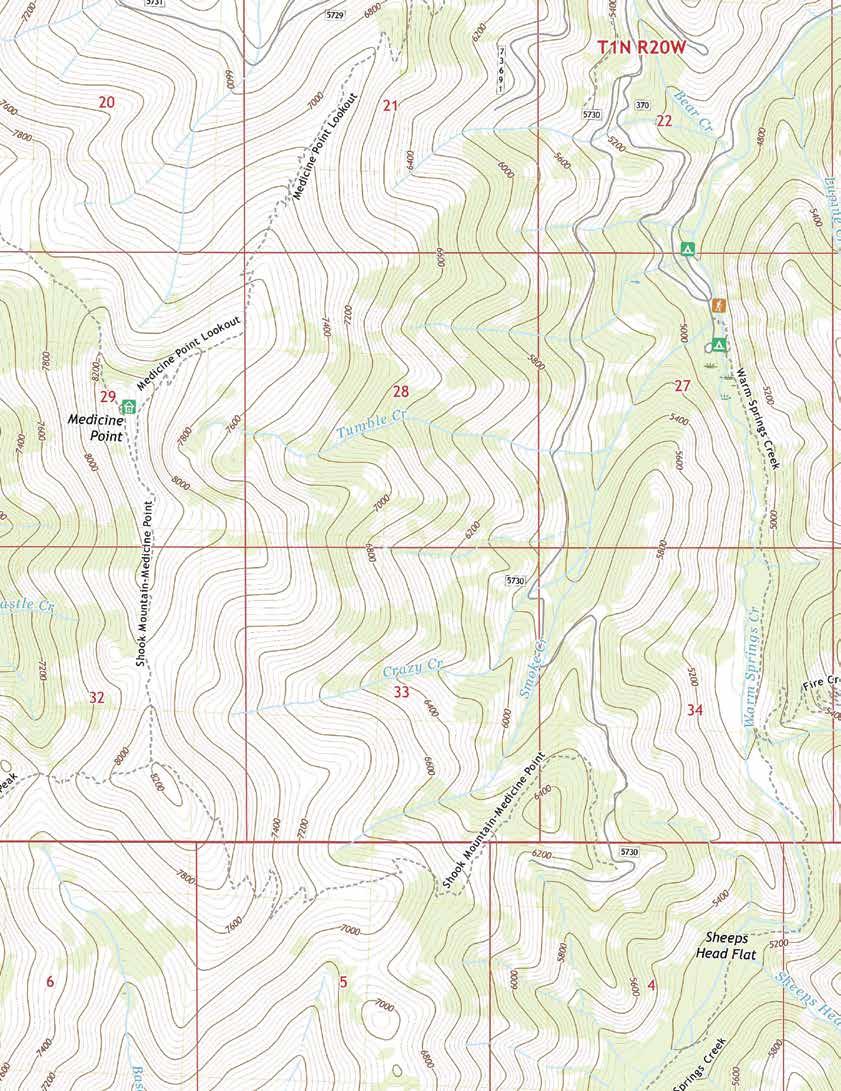

Words and Photos by Mira Brody

The color of the trail beneath our fast-moving feet changes according to where we are on this mile-deep map of geologic time that dates as far back as 1.84 billion years. A cross-section of this kind of history can only exist here, in the Grand Canyon. With each step, we gain distance but lose time—the push and pull of submitting yourself to a vast landscape. Currently, we’re somewhere in Redwall Limestone, a 500-foot band formed during the Mississippian age more than 300 million years ago. Blood-red dusty proof stains my shoes. A canyon hiker steps aside as our crew of three women run by, the first rays of the morning sun warming our skin on an otherwise chilly November morning.

as it is succinctly referred to, is a not-so-succinct undertaking. From our chosen route—starting at South Kaibab trailhead, summiting at North Kaibab trailhead and concluding at Bright Angel trailhead— we cover 48 miles and over 11,000 feet in elevation gain.

The experience is as much individual as it is communal. R3 is a globally revered bucket list accomplishment for thru hikers and runners and while we’ll spend many miles of the day alone, there’s a small migratory community inside the labyrinth of the canyon all striving for the same goal in the same giant hole in the ground. We see each other only for brief moments in time, exchange a nod, greeting or intel about the last few hours of our lives. And then, never again.

“Are you doing all three rims?” the hiker asks us, the first of many times we’d be asked that question on our long journey. “Today?” he asks. Time is relative down here. Distance however, is not.

We tell him yes between short breaths and the hiker exudes a sound somewhere between admiration and disgust. I feel the same.

Grand Canyon National Park sees more than 6 million annual visitors. Ninety-nine percent of them view it from the visitor center, taking in the great chasm from above; and some hike portions of it from nearby trailheads. A lucky few snag coveted backcountry campgrounds along the canyon’s base and backpack at a leisurely pace.

Fewer still choose to run its entire breadth twice in a single day—my friends and I among these indulgers of Type 2 fun.

We cross paths with a woman in her 50s just shy of the North Rim who has run the Grand Canyon every single year for 15 years. This year she invited a friend, a first-timer, to the sufferfest and asked us to pass along words of encouragement to her a few switchbacks down. Then, while refilling water at the Manzanita water spigot, we meet a man from Oregon and gleefully compare bagged goo flavors, a delicacy on the trail.

The day wanes and we exit the snow patches on the canyon’s chillier north side, accidentally startling an older gentleman as he slowly and steadily works his way back to Phantom Ranch where he’ll stay the night. We had seen him hours previous when he was climbing the North Rim, boasting that he had just turned 70.

With three rims to summit and descend, Rim to Rim to Rim, or R3

Deep in the lower gorge, the ground is a light yellow-

66

Traversing the Grand Canyon is no small feat—the trail system summits and descends the canyon’s rim three times, covering 48 miles and over 11,000 feet of elevation gain. The canyon is also home to layers of rock from bygone eras showing a near perfect cross-section of North America’s geologic history.

brown as our feet pound the Vishnu Schist layer, more than 600 million years old. Bright Angel Creek, which we’ve followed for most of the afternoon, fills the otherwise quiet trail before flowing back into the Colorado River. Lights from a passing campground flicker on as darkness descends. Campers are preparing dinner and I almost wish I could stay down here with them, in this alternate layer of time. Instead, we’re pulling clothes out of our packs as the otherwise warm fall day fades in time for our third rim, and final climb.

There is no sunset 6,000 feet underground. One minute there’s a faint light glowing from the edge of the rim above us, and the next we’re crossing the Colorado River in complete darkness.

Our company dwindles down to a few headlamps twinkling in the void that swallows us. Without any indication of distance, these bobbing lights appear to be either 10 or 1,000 feet away, indistinguishable from the galaxy that has appeared above our heads. Unless we pause to look up, our world is limited to the 2-foot halo cast by our own headlamps for the entire 9-mile ascent from the river. Even the colors of the rock layers are invisible, our sense of deep time erased.

Suddenly, a change in pressure and a 25-degree drop in temperature hits us with a chilly headwind. We are out of the inner gorge, referred to as “the box,” and walking along the Tonto Platform, a 500-million-year-old layer of impermeable shale that divides the upper canyon from the lower.

We pass another trickling creek and greet two young

women we had seen earlier that morning. They are dressed in vibrant Native ribbon skirts that glisten and sway by the light of our headlamps. We plunge back into the darkness for what will be the longest 2-mile so-called run of my life, following a series of meticulous switchbacks that hug the side of the upper canyon wall.

The Kaibab Limestone layer was formed 270 million years ago, which is approximately how old we feel as we crest the final rim of the stuff and hobble through the parking lot. Forty-eight miles on the body and soul is an intimate feeling, a mixture of pride and pain. Part of you wants to curl up and never walk again; but there’s another, smaller part of you that wonders how much more you might be capable of.

It’s 10 p.m., exactly 15 hours and 17 minutes from our start. The parking lot is as sparsely filled as when we left it, the sky just as dark. The three of us girls get into our car and eagerly pass around a Ziploc bag of cold pizza as we unceremoniously ponder what we’ve done.

We share a collective sigh: a mixture of relief, exhaustion and accomplishment and somehow embodies that entire span of time—a span that included millions of years of geology, a community of people and an entire landscape.

67

Mira Brody is an avid runner and writer in Bozeman, Montana. She is the producer of Mountain Outlaw and content production director at Outlaw Partners.

Taking on our final stretch up Bright Angel Trail just after 6 p.m., the concluding 9 miles of our day is not only stacked on top of 40 miles behind us, but also made in complete darkness.

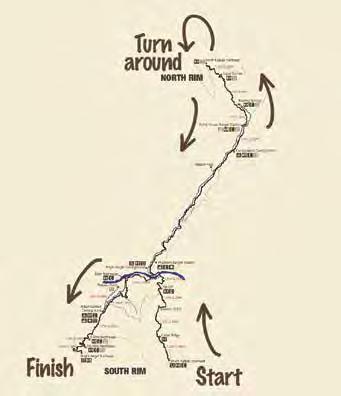

Days from Yellowstone to the Yukon

ever-changing,

By Heather Waterous and Amaya Cherian-Hall

✖ ✖

Two women (and one dog) embark on an

human-powered journey across one of North America’s most iconic wildlife corridors

Amaya Cherian-Hall (left) and Heather Waterous (right) take a shady break to refuel and smell the wildflowers on June 17, 2022. The two women completed a nearly 3,000-kilometer journey from Yellowstone National Park to the Yukon over 100 days. Photo by Hazel Cramer.

Editor’s Note: This is the story of two women who set out to complete a 5,000-kilometer human-powered traverse of the Yellowstone to Yukon wildlife corridor. After experiencing such a massive feat together, it was only right to have them tell their story in the same sort of parallel they journeyed in for five months. Their transitions are signaled by their names.

It takes a special kind of friend to say yes to a five-month backcountry trip after a 10-minute phone call. But Heather is that kind of friend.

By the end of that 10-minute call in March of 2020, we had committed to a 5,000-kilometer human-powered expedition that would traverse the Yellowstone to Yukon (Y2Y) wildlife corridor. The plan: start in Yellowstone in May and finish in Dawson City, Yukon, by early October. We would begin by hiking the Continental Divide Trail to the Canadian border, then connect to the Great Divide Trail. After four months of hiking, we would switch to bikes and cycle the Alaska Highway to Northern Canada. Our trip would finish with a 700-kilometer canoe. That was the plan. Here’s what happened.

AMAYA: Heather and I are both drawn to expeditionstyle trips because we understand the relationship that is built when you take time to travel over land. There is an intimacy and understanding that is missed from inside a car or plane.

Following in the footsteps of bears and wolverines who rely on the Y2Y wildlife corridor, we would be building a connection to the land that links both of our homes: Heather’s in the mountains of British Columbia and mine in the Yukon.

HEATHER: That out-of-the-blue call changed many things for Amaya and me over the next two years. During that long period of preparation, we each reflected on why this trip was such a special undertaking for us. We’ve both worked in outdoor education and have had many of our own adventures. Through these experiences, we’ve learned the importance of having female role models and communities of women in the outdoors.

An adventurous woman doesn’t simply burst into being. She grows through nurturing, mistakes, hilarity, heartbreak, moments of wonder, physical pain, determination and love. Adventurous women come into being through access, support and community, not in isolation. In pursuing our dream expedition, we were following in the footsteps of many other strong, adventurous women.

Our final weeks of preparation sped by in April of 2022, food and gear purchases made possible in part due to a Women's Expedition Grant from the Royal Canadian Geographical Society. And then, quite suddenly, we were on our way. Just the two of us and Jasper the trail dog at Raynolds Pass, Montana,

69

Waterous (left) and Cherian-Hall (right) plan the next day’s route after a well-deserved dinner. Both women had just finished biking up MacDonald Pass near Helena, Montana, in 90-degree heat on June 16, 2022. Photo by Hazel Cramer.

facing the immense prospect of the next 5,000 kilometers.

AMAYA: At the start of our trek we took stock of our belongings: Regretfully heavy backpacks— check. Hiking poles—check. Jasper the trail dog—check. With butterflies in our stomachs and snowshoes on our feet, it took us about 300 meters of walking to realize we had left one of our bear sprays on the roof of the car. Oops.

Energized by the excitement of finally being en-route, we trudged through forest and cow pastures and settled into a snow-covered camp for our first night. We went to bed content but apprehensive of the distance ahead.

HEATHER: The early days of the trip were a reality check featuring extensive side-hilling, massive snowy wolf prints, hangry tears, teamwork piggy-backs across creeks, and ultimately a difficult decision point in a winter-wonderland meadow.

We made our distance goal easily on day one, but days two and three (which were longer pushes) were another story. While we were using snowshoes, we hadn’t counted on the sheer quantity of snow. That, paired with warm temperatures, meant we were often slogging through knee-deep mush.

That afternoon found us contemplating the reality of meeting our timeline in these conditions. Wanting the expedition to be a success, we channeled our inner flexibility and changed our plans on the fly.

Our decision to reroute was immediately affirmed when Amaya woke up the next morning to swollen and painful Achilles tendons. We headed for the nearest road, stuck out our thumbs and hitched a ride.

AMAYA: And so it was that Heather and I found ourselves in Lima, Montana, three days early.

Lima is a small, quintessential roadstop town. Over the trip, Heather and I passed through Lima three different times and became sentimental toward the place. We booked a motel room and began replanning the first two months of our trip. Re-hashing an expedition of this magnitude— which required

booking popular campsites half a year in advance—was no small feat, logistically or emotionally. Thankfully, my flexible nature and Heather’s attention to detail allowed us to come up with a great new plan.

After a brief flirtation with potentially road-walking, we decided to bike. Our new plan involved biking back to Yellowstone, exploring the park, then roughly following the Continental Divide Mountain Bike Route to the U.S.-Canadian border where we hoped to rejoin our hiking itinerary. Heather’s parents very generously drove down and traded us our bikes and panniers for Jasper, and we were off again.

HEATHER: Our revised route and mode of travel proved successful. Though injuries would continue to accompany us both (Amaya’s Achilles remained stubborn, and I developed a persistently grumpy knee), we cycled onward. Throughout the rest of our trip, we were able to continue supporting each other in difficult physical and emotional moments, and ultimately made our trip work for both of us—because this trip was for both of us. The whole experience is now made up of a tapestry of memories, ones we will always look back upon fondly. And it truly began with us backtracking into Yellowstone National Park.

Our first night in Yellowstone found us quietly sitting by the edge of the Madison River, engrossed in capturing the magic of the evening glow in watercolors. We were surprised by some bison splashing through the river in front of us; a sight that had us both grinning as we gathered up our paints and notebooks.

Bison are ubiquitous in Yellowstone, though this hasn’t always been the case. Exploring Yellowstone by bike was surprisingly intimidating when it came to navigating both tourist traffic and herds of these thousand-pound animals. Throughout the park, the picture beyond our handlebars was painted with the jewel tones of geysers, while our hearts were full of the Tracy Chapman songs I belted out nonstop on a number of long descents while Amaya drafted me and giggled at my ecstatic singing.

AMAYA: At home, I often feel tired in the middle of the day for no reason. When tired on a trip, though, I know I have earned it. One day, outside Yellowstone, we were biking in freezing sideways sleet and there

Waterous enjoys rest in a field of flowers in the national forest near Helena, Montana. During this heat wave, the adventurers had to stop their bike ride at noon this day when temperatures climbed to 95 degrees F. They found reprieve in a creek and meadow.

70

Cherian-Hall cheeses through the snow on the pair’s first day on bikes a few hours after leaving Lima, Montana. Photo by Heather Waterous.

Photo by Amaya Cherian-Hall.

was nothing we could do but ride faster. The power of the storm thrummed in our numb legs. Unable to decide between laughing, crying or screaming as water streamed up our sleeves and down our collars, we scream-laughed our way down the highway. I’m not sure I’ve ever been so cold, and it’s rare that I’ve felt so strong.

HEATHER: Not all days were a battle against the elements. We spent a glorious week exploring the Pioneer Mountains Scenic Byway. Book-ended by idyllic hot springs on one end and a 15-kilometer downhill on-bike dance party on the other, the byway stands out as both a relaxing respite and raucously hilarious time.

AMAYA: Northern Montana in June graced us with cold, clear lakes, freshly blooming flowers on the bones of old forest fires and friendly fellow bikers heading in all directions. Many towns in that area and their residents have embraced cycling culture. Ovando, Montana, offered us a plethora of free accommodation options including a tent, the basement of

a church and an old jail. Elsewhere, homeowners shared their guest rooms and dinner tables. The owners of a little Alpaca farm treated us to lunch and we let ourselves be convinced to spend the night. We were often invited to camp, even when campgrounds were full. One campground host shared his fire and showed us the beautiful fairy houses he was carving. Surprising us, this unassuming man also told us of the murder mystery novel he was writing and of his former life as a detective and forensic artist.

HEATHER: While there was comfort in the communities we found along the way, we also enjoyed peaceful quiet. We each did a solo hike to Morrell Falls in the Swan Mountain Range of Montana. Pre-dawn, I sang to myself as I walked, feeling an immense level of gratitude for all the beautiful places we’d been. I rounded a corner to the misty falls and walked right into the spray, basking in the feeling of a million tiny cool kisses.

We also rode separately up the Going to the Sun Road

in Glacier National Park; each reveling in our own special moments of mountain solitude. We had left at the crack of dawn and were the first and only ones at the top as the sun rose over the park’s iconic peaks.

AMAYA: Each day was its own experience; occasionally one contrasting completely with the next.

On June 15, we went to bed early, too cold to enjoy sitting outside. The following day, we biked in 90-degree heat while climbing a 600-meter pass as the sun baked into the black asphalt. Somehow, between one short shady stop and Kendrick Lamar’s new album pumping through my headphones, we made it to the top of the pass, one sweat-inducing pedal stroke at a time. Overjoyed by the cool breeze on our way down, we blew right past our campsite.

It seemed juxtapositions were everywhere, from the “wild” of protected park lands butting up against towns, cities and ranch lands, to prairies meeting the Rocky Mountains.

HEATHER: While we passed through the ever-changing landscapes, we fell into a routine made up of the vital constants that marked each passing day.

We began each morning with a session of core work, pushups and stretching; listening to the birds and our bodies. Even now, we try to keep each other accountable to this routine from afar—though it’s not quite the same feeling in my living room as on a grassy hill under a pink dawn above the Yukon

River, having finished our crossing of Lake Laberge the previous evening.

We finished each day curled in our sleeping bags, writing in our daily journals and listening to an audiobook. Our “story time” became a way to unwind, aided by the trade of nightly massages. We helped each other soothe sore muscles as books soothed our tired minds.

The consistency in our routines and our companionship created a sense of a traveling, two-person community that was briefly immersed in many other community bubbles along the way. Upon reaching Canada, this feeling was both amplified and challenged as we left our bikes behind and began the hiking section of our trip.

At this point Amaya took a two-week break to rest her Achilles tendons, and I began hiking the Great Divide Trail without her; a foreign feeling after her constant presence the previous two months.

I reveled in the utter solitude of my hiking days, grateful to have so many special moments for just myself and simultaneously desperately wishing I could be sharing other moments with Amaya.

One particular night, the wildest storm I’ve ever experienced thrashed around me in my tent. I cried and wished to share the sleeplessness of the night with a friend before eventually drifting off. The following morning, I woke to an eerie sunrise. The storm, refusing to move on, was whipping the tent

72

Waterous crosses a creel on a single-track alternate route along the Pioneer Scenic Byway where a bridge had been removed.

Photo by Amaya Cherian-Hall

around. I knew I would soon be racing the same storm along the castle-like ridge. Despite the absurdity of the night before, and knowing that the coming day would be challenging, I laughed at the sun-painted sky and sealed the memory of the moment away.

The next day, my knee became a serious problem and I was once again thrown into the turmoil of the unknown and the necessity to re-plan a section of our trip. This involved Amaya taking on some solo hiking time while I sought medical attention and let my body heal as best I could.

AMAYA: Heather and I met up before I began hiking. She passed off some gear and we talked about what our trip could look like going forward. At different points we had both come to terms with one of us carrying on and finishing the trip alone. We were one another’s cheerleaders, and I felt Heather rooting for me as I set off.

I always thought the world-famous parks of the Rockies were overrated. Now, having spent a few weeks linking one spectacular trail to another, running into bears, moose, marmots and more, I understand why Heather had chosen to build herself a life in this part of the world.

I wasn’t sure how my Achilles were going to hold up so I started slow, progressing from traveling 10 kilometers in a day to 30. Each day brought new mountain ridges, Jasper’s constantly wagging tail, and a feeling of euphoria. The peaceful walking also allowed plenty of time for reflection and I realized that the best way to finish this trip would be with my friend. Heather picked me up from Yoho National Park and we roadtripped through Northern British Columbia up to the Yukon.

HEATHER: Arriving in Whitehorse, surrounded by Amaya’s welcoming family, was a milestone. For so long, the Yukon had felt out of reach.

The rawness of the late summer Yukon landscape followed us into our canoes onto the Yukon River, across Lake Laberge, and onward downstream. Our pebble-beach camps, the late summer mosquitoes, a hint of fall in the air and unexpected wildlife around each bend all breathed a sense of aliveness back into me that had been missing after my three-week hiatus from the expedition. Falling asleep to the sounds of the river calmed my ever-busy mind.

We woke early on our final morning, poised to make it to Dawson City and off the river in time for the Annual Outhouse Race. This weird and wonderful race, with teams of absurdly dressed participants pulling outhouses on wheels, embodies the eclectic northern town. Dawson is a

melting pot of gold-rush history, defined by its quirky traditions and equally quirky people. The day unfolded to include a reunion with Amaya’s mum, a failed attempt at the Sour-Toe cocktail (they were closed!), and a David Bowie tribute band. It was a night of dancing past when our feet hurt; the grins never leaving our faces and the laughter pouring from our lips. As a last, surreal way to say goodbye to a wild, challenging and wonderful expedition, we made the paddle back to our camp across the river in the dark at 3 a.m., just as we had started: as a team.

Late August found us parting ways, the expedition at a close, after exactly 100 days of moving our bodies across expanses of landscape.

Eight months post-trip, we reflect on the more than 3,000 kilometers we traveled by bike, foot, and boat, and why this experience had such an impact on us. I will leave you with this:

There is something about the mountains, specifically soaring rock-and-snow peaks at dawn, that cracks open our hearts and fills them with a glowing giddiness and simultaneous feeling of timelessness and insignificance. There is something about the endless plains and the constant movement of rivers that embodies the infinite and makes it tangible. And there is something about the love and companionship of a friend who truly sees all sides of you, day-in and day-out, that holds space for the wildness, tenderness and vulnerability that lives inside of each of us. I have rarely felt all this at any other point, in any other place.

Heather Waterous lives and works in Invermere, BC. In her free time, she can be found mountain biking, skiing, playing crib, dancing in the kitchen, or cuddling her two cats (Miro & Nebs) or her partner’s pup (Otto). Actually, your best bet for finding her is cuddling with one or more of the animals.

Amaya Cherian-Hall lives in a cabin with her dog in the woods of northern Canada. She loves spending time outside, playing board games, and eating. "I have never seen Amaya not eating" - quote from a friend

Waterous and Jasper the trail dog enjoy the view across the Yukon River as the adventurers approach Lake Laberge on their first day paddling. While the lake is technically a widening of the river rather, Waterous says this 50-kilometer section feels like a lake with no sense of helpful river currents to move their boat along. Photo by Amaya Cherian-Hall

74 Thinking about living in Big Sky, Montana? Perhaps now’s the time. The Big Sky Real Estate Company is the Exclusive Brokerage for Moonlight Basin and Spanish Peaks Mountain Club. BIG SKY IS CALLING. YOU MIGHT WANT TO ANSWER THAT. BIGSKYREALESTATE.COM MOONLIGHTBASIN.COM SPANISHPEAKS.COM MONTAGERESIDENCESBIGSKY.COM 406.995.6333

76

Horses stand at the ready during a spring branding event. The epitome of community, sixth-generation Montanan Maria Lovely writes about the tradition of brandings in Lending a Hand on p. 86.

Horses stand at the ready during a spring branding event. The epitome of community, sixth-generation Montanan Maria Lovely writes about the tradition of brandings in Lending a Hand on p. 86.

THE BIG TWO-HEARTED RETREAT // 78 LENDING A HAND // 86 THE DNA OF WHO WE ARE // 90 77

Photo by Maria Lovely.

ROOTS

THE BIG TWO-HEARTED RETREAT

A modern-day exploration of Ernest Hemingway's relationship to wild Montana and Wyoming

By Toby Thompson

By Toby Thompson

The scholars are dancing. It’s the last night of the 2022 Hemingway Society Conference and aficionados of the American novelist from as far distant as Japan boogie feverishly. They hustle, jitterbug, sashay and two-step beneath a ceiling of hand-hewn logs and sturdy beams canopying the Range Rider Lodge in Silver Gate, Montana. The conference goers have sampled a bevy of Hemingway cocktails distributed gratis: Papa Dobles, Old Fashioneds, Jack Roses and Pauline’s Preferences. Within this cathedral to masculinity hangs an exhibit of photographs of Ernest Hemingway fishing, hunting and posturing manfully. To the scholars’ left, a display of Hemingway-era rifles and pistols, a grizzly hide and tie-flying gear further connect to lore of the writer’s virility and this rustic Montana setting. Dancers gyrate to a band that roars as loudly as might the mountain beasts that surround them—the bears and wolves of Yellowstone National Park and the Absaroka-Beartooth Wilderness.

Amid celebrants at the conference is Chris Warren, author of the 2019 book “Hemingway in the Yellowstone High Country,” a work which changed much in Hemingway scholarship. Warren is the director of this leg of the 2022 Sheridan/ Cooke City/Silver Gate conference and is a compact man of 50, with a dark crewcut and stubble beard, wearing loose khakis and black sneakers.

“It was a handful,” Warren says of organizing the fete. “First it was the pandemic, which canceled the 2020 and 2021 conferences, then the floods,” which closed access via the Beartooth Highway and the northeast entrance to YNP, thereby isolating Cooke City/Silver Gate from the world. As conference director Larry Grimes has quipped, “We’re waiting for the locusts.”

Previous scholarship has downplayed Hemingway’s time near Cooke City, but as Warren has written, “Hemingway stayed at the L-Bar-T ranch, 13 miles from Cooke, in 1930, ’32, ’36, ’38 and ’39,” for long summers and falls. “He wrote significant parts of [the novels] Death in the Afternoon, To Have and Have Not, For Whom the Bell Tolls, and [the stories] “Light of the World, A Natural History of the Dead, and the preface to The First 49 Stories here.” The region also appears in [the books] Green Hills of Africa, True at First Light, For Whom the Bell Tolls, Across the River and into the Trees, Islands in the Stream, [the stories] The Gambler, the Nun and the Radio, A Man of the World, Fathers and Sons, and The Clarks Fork Valley, Wyoming

It seems to have been, in numerous ways, Hemingway’s last good country. “But the

79

Range Rider Hotel, Silver Gate, Montana. Circa 1945. Photo courtesy: WaterArchives.org

2021 Ken Burns film on Hemingway gave one sentence to Wyoming and Montana,” Warren says.

What the Pulitzer-and-Nobel-Prizewinning Hemingway loved about the Cooke City area, with its trout-heavy Clarks Fork of the Yellowstone River and rugged Beartooth Mountains, was its isolation. With 200-400 inches of snow a year, an 80-person population and limited access, the town was cut off, even in summer, from the outside world. Hemingway could write in the mornings and fish or hunt in the afternoons. He spoke of being “cockeyed happy” there. His second wife, Pauline, and their two sons camped with him in the L-Bar-T’s rustic log cabins, and friends regularly visited. But as scholars at this conference reminded, the writer’s infamous demons nagged.

There was his trophy hunting of grizzlies, mountain sheep and elk, and his larder-stuffing pursuit of trout; all a manifestation of his extravagant interest in killing wed to compulsive risk-taking and an obsession with suicide. As he later told an acquaintance, “I’ve spent a lot of time killing animals and fish so I won’t kill myself.”

On Friday morning of the conference in Silver Gate, and again that afternoon, Stephen Gilbert Brown, of the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, spoke of Hemingway’s deep psychological wounds. Even the most casual devotee of the Hemingway saga knows that at age 19, as a Red Cross ambulance driver on WWI’s Italian Front, he was hit by machine gun and mortar fire and spent half of the next year in treatment for extreme lacerations of his legs. The PTSD he suffered from that wounding manifested itself as sleeplessness, a near life-long dependence on alcohol, and possibly his suicide in 1962.

But he was the victim of psychological trauma that occurred before his service, scholars argue, ones inflicted by his mother, who twinned him with his older sister, Marcelline, and dressed him as a girl until he was almost 7. Gender confusion resulted, as did the suppression of his feminine side and the hyper-expression of his masculine one. He fist-fought, fished, philandered and killed, yet was androgynous in

bed. These contradictions are discussed in Brown’s 2019 book, Hemingway, Trauma and Masculinity: In the Garden of the Uncanny.

“The critical assumption,” Brown notes, “is that these two wounds (war and androgyny) are in reality the same wound: a wound of emasculation— suffered in infancy, sustained through childhood, boyhood and adulthood, and compounded by the wounds not only of war, but love.”