Power & Perception

Editor-in-Chief

Managing Editor

Executive Editor

Senior Editor

Senior Editor

Global Politics

Culture & Ideas

Law

Interviews & Events

Issue Design

Board of Directors

Kate Schneider

Fonie Mitsopoulou

Mats Licht

Justas Petrauskas

Ming Kit Wong

John Helferich

Sobha Gadi

Marta Kąkol

Zoe Lambert

Sanjana Balakrishnan

Jack Sagar

Miyo Peck-Suzuki

Danilo Angulo Molina

Jason Chau

Andrew Wang

Samuel King

Samuel Murison

Henry Ferrabee

Andrew Wang

Brian Wong

Michael Shao

Nicholas Leah Chang Che

Simon Hunt

Artwork on cover graciously provided by Ann Kozlowski-Hunt (Instagram: @annikinski) and inspired by the work of Faith Ringgold.

A sincere thank you to everyone who made submissions to this issue. All articles that appear in this issue will also be made available online in due course.

Some images have stood the test of time. Having catalyzed political change, they now remain instantly recognizable around the world.

Jeff Widener’s photo of an unknown man defiantly staring down and obstructing four tanks in a row, two shopping bags clutched in his fists, directed global attention towards the 1989 student protests at Tiananmen Square.

The haunting images of struggling workers and their families during the Great Depression by American photographer Dorothea Lange captured the despair of a generation wracked by poverty.

Huỳnh Công Út’s horrific photograph depicting desperate children fleeing the bombing of their village, crying out in pain as napalm showers down on them, solidified opposition to the Vietnam War.

And the heartbreaking photograph by Turkish photojournalist Nilüfer Demir of 2year

old Alan Kurdi, lifeless and washed up on a Turkish beach face down, brought public outcry against the treatment of Syrian refugees by European governments.

These photographs have persisted in our collective memory because of the powerful emotions they evoke. They demonstrate how images can connect with our humanity in a way that written appeals cannot. Something about seeing a human face contor ted in agony or lit up with joy speaks to us on a deeper level than endless statistics or numerous headlines ever will. A masterful photograph or painting manages to shrink down and immortalize large, worlddefining events into a brief but meaningful snapshot, preserving history in an almosttangible way for future generations. In this way, images are particularly adept at their ability to wrest us out of a state of emotional indifference.

The pieces in our ninth issue speak to this power of the visu

al. A few of our writers investigate images as constructed illusions: Cameron Scheijde examines the Palace of Westminster’s design as a product of Victorian mythmaking; Sean Moran explores the effect of ‘sportswashing’ in the world of Formula One; Yael Isaacs scrutinizes Zionist posters as reflecting Israeli efforts of nationmaking.

Other authors highlight how visuals can empower. Justas Petrauskas contemplates how architecture, particularly in postSoviet spaces, might fully embody the ideal of democracy; Simon Hunt argues for prioritizing both beauty and function when designing public transport systems.

Our contributors also unpack images as symbols. Bhumika Sharma looks at the central place beards hold over Indian politics, diving into the aesthetics of asceticism; Sapna Aggarwal muses over how flags emblematize national identities.

Visuals can also compel new

ways of thinking and serve as a call to action. Tanhā Kashfia Kate delves into film as a medium for calling out the dangers of nuclear proliferation.

Finally, unpacking different perceptions of history reveals that what is hidden is often just as informative as what is visible. Discussing the power of reflection, memoirs, and oftneglected heritage, Fonie Mitsopoulou interviews Avi Shlaim, worldrenowned scholar of international relations and Israeli history.

I would like to extend my thanks to our contributors for their pieces as well as to our dedicated team of editors who have worked tirelessly to review and shape these pieces alongside their authors. And, as always, endless thanks to our readers. Whether you are a longtime supporter or someone who has just picked up a copy to browse, we hope you will stick with us into the rest of 2023 and beyond.

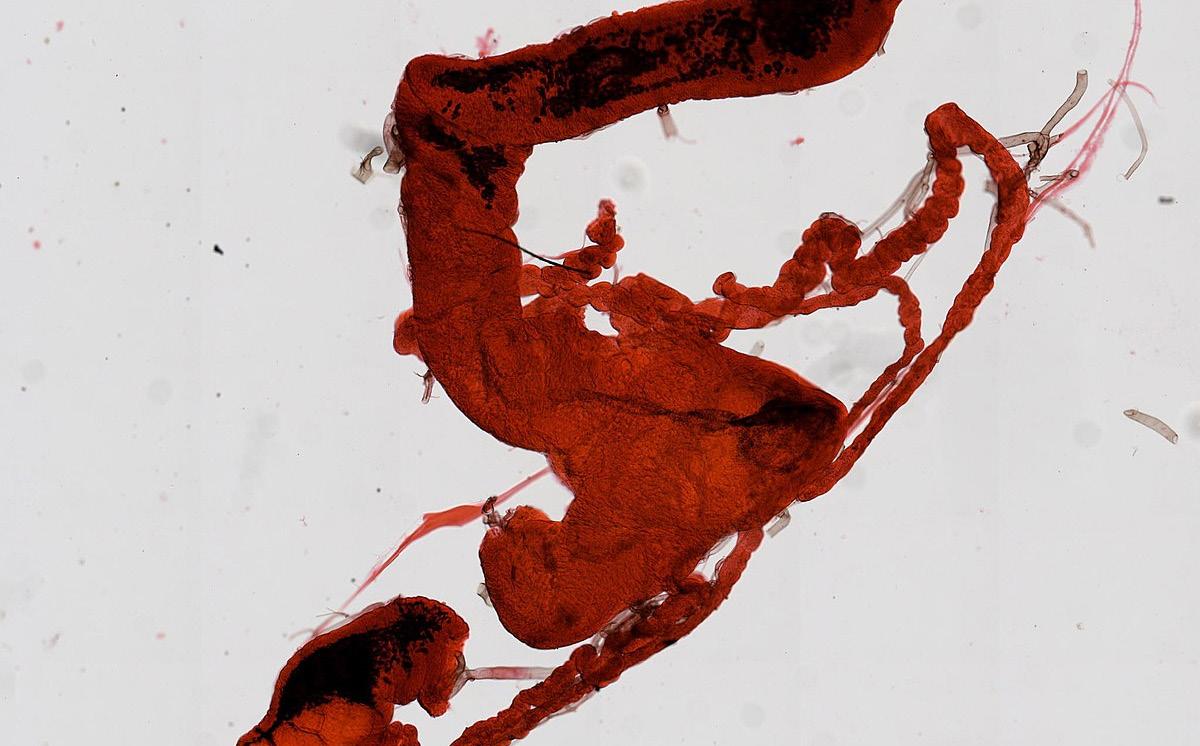

Kate Schneider Editor-in-Chief La Mort de Marat (1793) by Jacques-Louis David portraying the politically-motivated murder of radical French journalist Jean-Paul Marat in his bathtub.

Most of us are aware of the ease with which private and state actors can manipulate visual imagery for their benefit in the digital age. However, politically motivated iconography is a tool that far predates the postmodern period. Zionist movements in the 1920s1940s, and the Israeli government in later years, used posters and other visual aids to promote national state creation, further a sense of common Israeli identity, and present their own version of history to the public. Relying on a core narrative formed through selective inclusion and exclusion, these posters formed a crucial part of the

Israeli national mythbuilding effort.

Before the rise of political Zionism in the late 1800s, Jews in Ottoman Palestine comprised about 5% of the population. They comprised either Sephardic or Mizrahi Ottoman Jews and the occasional religiously motivated settler or Jewish refugee. Sephardi Jews originated from the Iberian Peninsula and settled in other parts of Europe, the MENA region, or South America after their expulsion from Iberia. The Mizrahi Jewish communities have lived in the MENA region since ancient times.

In the 1920s, Jewish organi

sations in British Mandatory Palestine began to produce posters and other graphic publications to promote the image of a unified Jewish Palestinian identity. Communications scholar Ayelet Kohn and geographer Kobi CohenHattab argue that the posters reflected the sentiments of the artists designing them. These posters reveal the artists’ hopes for a return to Israel and the construction of a Jewish nation rooted in European culture. Crucially, these posters also depicted a paradigm shift: the pilgrimage and movement to Palestine were seen as culturally and politically — rather than religiously — motivated. For most of Jewish histo

Yael Isaacs is a Master’s student of Middle Eastern Studies at the University of Amsterdam.ry, the return of Jews to Zion was seen as only being possible at the coming of the Messiah. Therefore, any preZionist Jewish settlement in Palestine was founded on religious beliefs and based on individual interpretations of religious scripture. Political Zionism, a movement that advocated for the creation of a Europeanstyle nationstate where Jews would be the majority group, was conceptualized in response to increasing antisemitism in Europe despite the Enlightenment’s promise of tolerance. Zionist thinkers at the time proposed a Je wish homeland and selfgovernance so that they would not fall victim to the violent whims of the nonJewish majority. The movement aimed to construct this homeland based on an idea of common Jewish ancestry. Kohn and CohenHattab write that in the first few decades of the twentieth century, it became more common to view moving to Palestine as a ‘national act of settlement and revival.’ Tourism posters were, in many ways, a reflection of a growing desire for a Jewish settlement, and signalled an everincreasing Jewish interest in Palestine.

Zionist propaganda posters proliferated in the 1930s and 1940s. In addition to their aim of recruiting Jewish labour to construct a Jewish Palestine, they also promoted nonreligious tourism. Some early propaganda posters depicted strong, Germaniclooking Jewish men performing agricultural labour. Others contained orientalist motifs such as desert landscapes, lemon trees, and stereotypical figures supposedly representing the native population, depicting a EuropeanJewish settlement on an exotic land. Kohn and CohenHattab note that the artists of these posters were often new immigrants to Palestine from Germany and Austria, and were influenced by German and Russianstyle ideological art.

The images on these posters suggest that hard agricultural labour in an egalitarian society could create a strong state. Kohn and CohenHattab argue that many of the posters in this period combine artistic trends of the period with Zionist tropes, such as the holy land motif, with messages that promote European natio

nalism, modernism, and consumerism. In this way, these posters promoted the ways in which Israeli statehood could be achieved. This utopian image of statehood combined socialism, capitalism, the grand past of the ancient Jews, and the perks of modernity and secular European culture.

The ideology behind the two types of posters—those aimed at recruiting labour and those encouraging tourism—differed sharply. The recruitment posters maintained a socialist worldview and were influenced by the contemporary Soviet style of revolutionary propaganda. The paintings of Jews working in the fields, operating tractors, or living simply off the land are similar to socialist realism in that they glorify the proletariat. Furthermore, in the images where Jews work or feast together, there is no clear hierarchy; everyone is working in tandem for the social good without the watchful eye of an imperial agent. In contrast, as Kohn and CohenHattab write, the tourism posters with “oriental” figures and Levantine landscapes implied that the best way to build a state was through capitalistic

enterprise, particularly tourism. The desire for a socialist state paired with the practice of emphasizing private capital is characteristic of Zionism throughout the years. Until the neoliberal turn in Israel in the 1980s, there remained a façade of egalitarianism that did not correspond with the reality of stark inequality, particularly among Israel’s nonAshkenazi and nonJewish population.

In the three decades following Israeli independence, visual and literary media aimed to create a coherent Israeli identity by spurring nationalism and an ideal of Israeli oneness. In these decades, the ‘heroicnationalist’ genre, as described by Ella Shohat, depicted the main characters as heroic pioneers, with the Arab characters only existing on the periphery, merely benefiting from a Jewish presence. While Shohat’s analysis focuses on Israeli cinema, the images and tropes prevalent in movies are also present in posters. According to Stephen Sharot, visual media portrayed the Mizrahi and Sephardi Jews as primitive and inferior to the Jews of European descent, but nonetheless assimilable. These films returned to Israeli theatres with renewed enthusiasm after the 1967 war, and Israeli posters mimicked these trends.

According to art historian Inbal BenAsher Gitler, a vital aspect of early Israeli posters includes the representation of ethnic differences among Jews in Israel. The poster to the right commemorates the holiday of Shavuot, a harvest festival, and portrays a communal agricultural settlement, demonstrating the ideal of the original Zionist leaders. One of the children has darker skin and wears a hat and peyot (side locks), indicating that he is a Mizrahi immigrant. As Gitler

Palestine Foundation Fund 1929. Courtesy of Keren Hayesod, Circa 1930. Jerusalem.and Shohat both argue, in the 1950s, the representation of ethnic differences was manifested in the idea of kibbutz galuyot, or the ingathering of diverse Jewish exiles in Israel. Kibbutz galuyot is a part of an Israeli mythology that views preIsraeli diasporic life as existing outside of history and, therefore, renders that history unimportant. For Gitler, this strategy manifests itself in the homogeneity of the colours of the clothes in the poster, representing national unity. Other posters from this period also display groups of people with homogenous features and clothing. Artists often downplayed ethnic differences among Israelis in these, as evident from the delicate shades used in their skin tones and the lack of detail in their faces.

The orientalized images of some figures in these posters are ambiguous regarding whether they represent Palestinian Arabs or Mizrahi Jews. Both were considered “others” to Israeli identity, though only the latter were thought to be assimilable. Thus, while some posters depicted Mizrahi Jewish and nonJewish Middle Eastern figures as out of place and corresponding to stereotypical traditional tropes, others ignored ethnic differences entirely to promote an image of a singular Israeli identity. Both strategies contributed to the erasure of Mizrahi and Arab heritage: the former reinforced ethnic hierarchies by infantilizing the depicted Mizrahi Jews, while the latter ignored cultural differences and portrayed all Jews in Israel as abiding by the same norms and cultural practices. The notable absence of figures representative of Palestinians, with Islamic influence confined to the scenery and architecture, mirrors their political and social exclusion from Israeli so

ciety. The posters, in Gitler’s words, ‘render Israel’s Others as stereotypical and generalized.’

Finally, the importance of military strength in securing and keeping a peaceful ancestral home is another vital component of Israeli national myth. Many posters combine images of the Israeli military with Jewish symbols, demonstrating the importance of military strength in maintaining a Jewish state. Other posters depict a gentle interaction between Israeli soldiers and the land, such as soldiers dancing at festivals, demonstrating that military force is essential to nationbuilding and peace.

Anthropologists Rebecca Stein and Ted Swedenburg argue for the importance of examining popular culture’s relationship to hegemony in Israel and Palestine. In the British Mandate era, Zionist organizations used posters to attract Jewish settlers to Palestine as a historical homeland and a potential new home for Jews. In effect, these posters erased the presence of Palestinian Arabs who had been living there for centuries. Postindependence posters,

on the other hand, promoted a unified identity and advocated that Israel should be a “melting pot” for Jews while continuing to suppress any traces of Arab presence in Israel.

The Sephardi and Mizrahi Jews were eventually alleviated from the socioeconomic oppression they initially experienced. However, extreme social inequality continues to separate Mizrahi Jews from their Ashkenazi counterparts, while Black Jews and Arab Israelis still face severe social and cultural mo

bility barriers. These inequalities are obscured as the Israeli popular culture still plays with the idea of Israeli oneness, while the modern Settlement Movement still wields the idea of reclaiming land. Many of the myths propagated in early posters remain integral to Israeli national ideology. Given these myths’ tendencies to marginalize, generalize, and exclude Mizrahi and Arab Palestinians, they further undergird the existing inequalities that continue to plague Israel today.

Roli Studio (Gad Rothschild and Ze’ev Lipman), Bikkurim, CZA, KRA/1814. Courtesy of the Central Zionist Archives.

Roli Studio (Gad Rothschild and Ze’ev Lipman), Bikkurim, CZA, KRA/1814. Courtesy of the Central Zionist Archives.

After 52 years of dutifully standing still, with eyes turned confidently to communism’s bright future, the statue of Vladimir Lenin was taken down from its pedestal in Lukiškės Square in Vilnius, the capital city of former Soviet Lithuania, on August 23, 1991. As a crane lifted it up, the statue broke in half; with the crowd cheering, the upper twothirds of Lenin swung in the air, while the legs, suddenly depleted of the grandiosity provided by the body, remained oddly attached to the pedestal.

It was by far not a rare occurrence that year. As the Soviet Union was slowly but steadily

collapsing, hundreds of monuments dedicated to Lenin, Marx and Engels, Soviet soldiers, and industrial proletarians fell in Poland, Hungary, Estonia and other countries formerly under communist rule. With the totalitarian regime gone, the people behind the Iron Curtain could finally imagine a future for their polities based on the ideals of democracy, the rule of law, and general inclusivity. That future eventually came — for some countries earlier, for some later: a large part of the former Eastern bloc joined the EU in 2004 and are now imperfect, yet functioning, democracies. But as time went on, one thing did not change: throughout

the last thirty years, the space freed up by the fallen Lenin in Lukiškės Square has remained distinctively empty.

It was not that it looked good that way. Quite the contrary — the landscape architecture of the square was designed with a statue at its centre in mind. With Lenin and the pedestal gone, the emptiness of the large rectangle of gravel was disturbingly obvious. It was also not that the square was irrelevant or that people did not care. Located in one of the capital’s central areas, the square and the question of a replacement monument were a topic of public debate for most of the postindependence period.

Justas Petrauskas is a student of Philosophy, Politics, and Economics at Oriel College, University of Oxford.The problem was that finding agreement on Lenin’s replacement turned out to be very difficult. The case of Lukiškės Square is not an isolated one. After more than half a century of their existence, the communist governments left the territories of the Eastern bloc littered with millions of statues, parade squares, museums of “communism and revolutionary history,” grand administrative buildings, and imposing “palaces of the people.”

This project of incredible scale and commitment was hardly unique in its aims, namely to project and assert political ideals through architecture and urban design. It stood out, however, in the sheer distance between what was being projected and the reallife experience of the people. While the Soviet Union is often cited as an example of a wrongheaded economic project, it was also its politics that was a source of the inconsistencies between image and reality: its officially celebrated but meaningless elections, the prevalence of censorship and allreaching security agencies, and palaces of the people that never saw collective deliberation happening inside of them. At its core, the communist architecture was meant to project the idea that it was the unanimity of the people — and not the efforts of a handful of re volutionaries or, later, nomenklatura in Moscow — that initiated, supported, and sustained the kind of societal organization that characterized former Soviet countries. Nothing, however, could have been further from the truth. Lukiškės Square here again acts as a miniature illustration of history: a grim building across the street from the Lenin statue housed the central offices of the KBG and NKVD, two main security

agencies which were responsible for controlling the popular dissent from the regime, and where thousands were interrogated, tortured, and killed during the fifty years of the occupation. As a typical “parade of the people” dedicated to the 1917 October Revolution would march through that street, the discrepancy between the ideals projected and the reality experienced would appear at its finest. To the left of the crowd stood the statue of Lenin representing a unanimously decided direction towards the socialist tomorrow; to the right — the palace of the KGB and a painful reminder that that direction was neither chosen, nor supported by the people in question.

just a choice between replacing Lenin with a similar statue of a national hero or converting the square into a public park. It is the question of how to project a political ideal of democracy through architecture, without fixing it into perpetual conflict with reality.

Democracy: for open-endedness, against conceptual closure

To locate the solution to this problem, it is best to start by unpacking the ideal in question. To project the ideal of democracy through architecture is to project a particular valueweighting: namely the one which places primary weight on the ability of citizens of the political community to act collectively in the name of the whole. For the people formerly behind the Iron Curtain, this emphasis is based on their shared struggle under totalitarian rule and the wish to pursue a future for their polity based on goals which are deliberated collectively, not derived from class theory or the laws of history.

It is evident, then, why the question of Lenin’s replacement (and the fate of all remaining communist political architecture) has been so difficult. Having experienced the excessive divergence between what is projected and what is real through the halfcentury of Soviet rule, the people in the Baltics, Hungary, or Poland have faced a troubling tension between the wish to project ideals of democracy, popular sovereignty, and independence, and the knowledge that such attempts are prone to going absurdly wrong. In other words, the question reflected by the empty gravel rectangle in Lukiškės Square is more than

Deliberation and reflection, as Laurence Whitehead aptly notes, are crucial in conceptualizing democracy as an ideal. Democracy is about social consensus — but nonetheless, a consensus that is always interrogated, deliberated, and rechecked in the individual consciousnesses of the citizens. Because of its reflexive and deliberative nature, democracy as an ideal, in Whitehead’s words, ‘precludes the conceptual closure concerning its own identity.’ All worthwhile conceptions of democracy have to incorporate a cognitive capacity to challenge fixed orthodoxies. As an ideal, democracy calls for essential openendedness.

This is a big problem when it comes to projecting the ideal of democracy through architecture. The choice to fix the projection of an ideal in stone seems to run at odds with that ideal being openended. In other words, the activity of putting an ideal into plans and designs is precisely the case of conceptual closure regarding the identity of that ideal. The architecture of the Capitol Building in Washington, for example, might aim at projecting the ideals associated with American democracy, but whatever it projects is fixed by the decisions of the architects of the late 1800s. A fresco in the building’s rotunda, for instance, depicts the apotheosis of George Washington. Some of the ideals it embodies — the compatibility of democracy with slavery or idolization of the great men of history — have long been rooted out of the social consensus by critical collective reflection. The fresco, however, cannot, without being completely redone, reflect these changes. Deliberation may well happen inside the Capitol building concerning various questions, but the ideal projected through its architecture is conceptually closed.

In the same way, replacing Lenin’s statue with another grand statue would mean projecting ideals which were important

“While the Soviet Union is often cited as an example of a wrong-headed economic project, it was also its politics that was a source of the inconsistencies between image and reality.”

“The question reflected by the empty gravel rectangle in Lukiškes Square is more than just a choice between replacing Lenin with a similar statue of a national hero or converting the square into a public park.”

at the time of the building but closing down the way for incorporating reflection and deliberation into that projection.

The solution to this problem comes from how a similar conundrum is solved in urban planning. In his book Building and Dwelling, sociologist and urbanist Richard Sennet sets out the tension between two concepts: ville, the built environment which planners can influence and which is fixed once the plans are made, and cité, the human life that is led in that environment which, being uncertain, is beyond the deterministic influence of plans and designs. To focus entirely on planning the ville would mean ignoring the many ways humans unexpectedly alter their built environment and

committing the mistake of a topdown planned city. On the other hand, to trust only cité — that is, to leave everything for bottomup human behaviour and to abandon urban planning altogether — would also not be feasible.

Sennett’s solution lies in the concept of an open ville and a modest approach to urban planning. This requires sincerely involving dwellers in the process of planning, leaving space in the plans for unpredictable effects of the cité, and prioritizing, in the words of architect Robert Venturi, potential ‘richness of meaning rather than clarity of meaning.’

Towards an architecture of democracy in practice

For those wishing to project the ideal of democracy through architecture, two takeaways are critical: first, embracing modesty of ambition and leaving open the space for deliberation and, second, encouraging reflection on the ideal even after planning and building is complete.

To see how this looks in practice, return to the empty rectangle of gravel in Lukiškės Square. Following redevelopment works carried out in 2020, the square is now a multipurpose public space. There are green areas, benches, a ground fountain and even a dedicated space for a statue or a monument, if, in the future, the agreement on what it should be comes about. On warm summer days, it at

tracts a great diversity of people. Workers from nearby office buildings and government agencies traverse it on the way to lunch, the elderly chat on the benches in the shadow of trees, and children run around screaming and wet in the fountain area.

The square is not void of critical reflection, or apolitical in a dystopian sense. Demonstrations and protests often take place there and the use of the square itself from time to time resurfaces for a heated public debate; is it alright, for example, that a place steeped in historical suffering sometimes houses an artificial popup beach for a summer season? In that sense, it is a testament to Venturi’s and Sennett’s call for richness as opposed to clarity of meaning.

Because of the historical context of the place, it is not just a space for fun urban activities. Mixing complexity and contradiction, the square fulfils another obligation emphasized by Venturi — the truth it manifests is not in benches, a future statue, or demonstrations, but in its totality. That totality is the projection of the ideal of democracy. Where people once were squeezed between an imposing statue of a revolutionary demagogue and the omnipresent security agency building, marching for superficial ideals they never themselves chose, now there is a space which encourages collective deliberation of the goals of the polity and where one can sit, walk, think or run screaming into the fountain, if that feels like the right thing to do. This, far more than palaces of the people or great statues, reflects what architecture of democracy should look like: it is conducive to collective selfreflection, modest, and openended.

According to Benedict Anderson, ‘nationality’ and ‘that word’s multiple significations, nationness, as well as nationalism, are cultural artefacts of a particular kind.’ Indeed, they are performative gestures effected on a motley of objects as symbolic national emblems. For postcolonial countries in the Asian continent, like India, Pakistan, Indonesia, and others, the national flag as one such emblem has been both the site of nationalist struggle for independence from colonial rule, as well as the focal point around which a distinct national identity has been built postindependence. The

performance of nationhood is inscribed on the body of the flag every time it is employed to evoke national consciousness. It becomes the site where symbolic discourses of national grandeur are etched. However, once devoid of this symbolism, what is left of the flag is an inanimate piece of cloth (and other material) that was carved into a certain shape and formed by a cut. The laceration is the very body of the flag. It is usually this body which is left out of discussions on the flag as a politiconational symbol of power and prestige. The real body of the flag is the actual site of crime — the wounded fragment of cloth —

which is ascribed the illusory meaning of national unity and wholeness. This meaning is betrayed by the fragmentariness of the visual and tangible body of the flag — a cut of cloth that is painted in multiple (and hence partial) shades — which always lurks potently underneath narratives of greatness.

The wound that is the flag was strikingly exposed in 2017 during the 29th Southeast Asian Games held in Kuala Lumpur, when Malaysia mistakenly printed Indonesia’s flag upside down in its guidebook. The upsidedown flag resembled that of Poland,

Sapna Aggarwal is an MA student South Asian Area Studies at SOAS, University of London. The question of the wound as a sign and a symbol is still open. [...] The wounds of the Crucifixion, the holes of the nails and the cut on Christ’s side made by the Roman’s spear, are sacred signatures.leading Indonesia to take it as an insult to its ‘national identity.’ In becoming interchanged with each other, the visual body of the two flags collapsed the statemanufactured identity/ies on pieces of cloth, thereby establishing that symbolic narratives of distinct nationalpolitical identities are externally attached to these bodies and not intrinsic to the flags themselves. Indonesia’s Youth and Sports Minister, Imam Nahrawi, described this incident as an ‘error,’ one that was ‘very painful.’ If pain is but visceral manifestation of a wound, this episode was experienced as a laceration on the body of the nation. The cut, however, was made neither on the body of the nation nor its emblematic flag. Rather,

the materiality of the body of the flag was the cut itself. The whole incident made the flag a measure of lack and deficiency, rather than a performing agent of symbolic wholeness, that induced pain and suffering through its very body.

The body of the flag as a cut/

wound/fragment that could bleed and induce the experience of pain emerged more powerfully during the years of the Indian independence movement, when it became a site of struggle, resistance, and national pride, as argued by writer Sadan Jha. In the course of the fight against British colonialism, there were multiple flags (read: fragments) that were internally vying to become the one, the supposed ‘whole’ as the national flag. As political scientist Sudha Pai observes, these fragments were ‘the “Congress” flag, the saffron flag or Bhagwa Dhvaja of the RSS [Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh], and the green flag associated with the Muslim League.’ These were later incorporated into a sutured wholeness in the colour palette (saffron, white, and green) of the final version of the Indian national flag. Despite their specific symbolic associations, the colours of the national flag remain in the last instance corporeal fragments — portions painted in a specific shade on a piece of cloth. Professor Galili Shahar describes fragments as ‘a form of a wound.’ He notes that ‘fragments, like wounds, have the texture of a cut. […] Like the wounded body, the fragment bears the form of a rupture and stands as evidence of deficiency and imperfection. The fragment is thus the written form of absence and pain.’ The body of the flag(s) is thus a cut, a wound. It might be sutured multiple times in dif

ferent forms and colours, but it remains, visually and tangibly, gaping, betraying the symbolic wholeness. It is a marker of deficiency, lack, and pain which refuses to embody perfection and unity as a selfcontained unit. These fragments

as wounds are therefore not emblems of national unity and pride, but underlying ruptures symptomatic of partition(s), loss, violence, and hostilities in the history of postindependence South Asia.

Any attempt to merge and create an undivided whole out of alreadygaping fragments of hues and shapes must remain chasmal. The Pakistan High Commission in Dhaka was forced to confront this reality in July 2022, when it tried to replace Bangladesh’s flag from its official Facebook page with a ‘collage picture’ that merged the flags of Pakistan and Bangladesh by superimposing a moon and crescent onto the original red and green Bangladeshi flag. Bangladesh objected to Pakistan’s amnesic endeavour to forge unity and eventually forced the High

Commission to take it down. What this case demonstrates is that the merging of the two flags could not make a seamless whole as the body is already a wound on two levels: first, as a cut of fabric in itself; and second, through the real division of Bangladesh from Pakistan. The former constitutive cut as the body of the flag sits parallel to the latter as a historical site of conflict and violence. The body thus surfaces as a symptom, such that ‘the form of the symptom is that of a fragment,’ to borrow the words of Shahar. Far from representing the grandeur of national unity and federation that is attributed to it in official narratives, it is precisely the fragmentariness of the body of the flag which embodies the very essence of nationstates.

The real cut of the body of the flag can undermine both the political signification of national unity that is historically layered onto the flag and attempts to create alternate national visions through it. In a recent decision made by the Union government in 2022 to amend the Flag Code of India (2002), certain materials other than khadi or handspun cloth have been allowed for the national flag. Given that khadi has historically been associated with Gandhi and his legacy of struggle for independence in India, this amendment has effectively leveraged the materiality of the flag to undercut the flag as a symbol of na

“The cut, however, was made neither on the body of the nation nor its emblematic flag. Rather, the materiality of the body of the flag was the cut itself.”

“It might be sutured multiple times in different forms and colours, but it remains, visually and tangibly, gaping, betraying the symbolic wholeness.”

tionness and nationalism of the kind associated with the legacy of the Congress. At the same time, the body of the flag also undermines the Bharatiya Janata Party’s (BJP) attempt to make it their own. In 2022, the party launched the Har Ghar Tiranga campaign to mark the 75th year of Indian independence. Moving away from the erstwhile ‘formal and institutional’ connection with the flag, this campaign is meant to foster a ‘personal connection to the Tiranga.’ It is supposed to make the flag ‘an embodiment of our commitment to nationbuilding.’ This narrative of building a newer connection to the nation as opposed to an old one is associated with the party’s politics of religious nationalism that it wants to ascribe to the body of the flag, as well as the nation by extension. BJP has created a ‘frenzy’ around the national flag in a bid to be the new flag bearers of Indian nationalism. As a matter of fact, the Ekta Yatras (National Integration Rallies) that they have carried out in the past two decades have ended precisely with the unfurling of the national flag. However, once juxtaposed with the local portrayals of the flag, these narcissistic discourses of putative nationness and nationalism come crashing down as the body of the flag resurfaces in the moments of its mere physical existence. In some evocative pictures taken in a neighbourhood, resonating with the ethos of the campaign, on India’s Independence Day in 2022, photojournalist Chirodeep Chaudhuri captures the national flag in its most informal, domestic, and plain settings. In one of the pictures, the flag is depicted as torn — a visual, tactile cut/wound set against a prosaic background of everyday life — in a moment of ironic realization of the alleged intent of

the campaign by BJP. The image thus juxtaposes the mundanity of the body of the flag against symbolic meanings of anticolonial nationalism and politicosocial partisanship. It betrays these largerthanlife narratives that are written allegorically on the body, thereby functioning as a foil to the nationalist politics that the BJP indulges in. Chaudhuri focuses on the tedious visuality of the body of the flag by in

troducing it as an interruptive cut. It is literally torn apart as a nonsymbol; it can be seen and touched as a mere piece of cloth. It becomes dissociated from political partisanship as well as the symbolism of patriotism and national unity at the same time.

Thus, the body of the flag is in and of itself neither pronationalist nor antinationalist in its political orientation. The flag is rather a visual/tactile cut which only gains symbolic currency by means of a performance of metanarratives through and on its body. The irony is that the body of the flag in its material reality is a mere cut of fabric, a cut which is far from being a sacred signature on the body of Christ and which undermines the very nationalist and identitarian discourses that are inscribed on it.

“The real cut of the body of the flag can undermine both the political signification of national unity that is historically layered onto the flag and attempts to create alternate national visions through it.”

Standing on a hill in the west country city of Bristol is one of Britain’s most interesting buildings: a perpendicular gothic edifice dedicated to Henry Overton Wills, a tobacco magnate whose fortune constructed much of Bristol’s redbrick university. Its giant vaulted ceilings are taller than the nave of Wells Cathedral, and each intricately carved gargoyle and stained glass window evokes the height of collegiate gothic architecture in the 15th and 16th centuries. When visiting the building to give a talk in the impressive, oakpanelled Great Hall, former Prime Minister Gordon Brown commented that it evoked an abbey, a cathedral, or the Hou

ses of Parliament.

The Wills Memorial, however, is no ancient wonder; it is not even a century old. It is a folly built in 1925 to evoke the grandiosity of Oxford and Cambridge, and is the last secular gothic building built in England — quite unlike the abbeys or cathedrals Brown had in mind when first seeing the building, whose histories often span nearly a thousand years, but perhaps not as dissimilar from his old workplace as some may think.

The Palace of Westminster, home to the Houses of Parliament, summons a similar sense of ancient grandiosity, giving the impression of a

building and institution stretching back centuries. Its carving more ornate and golden gilding more impressive than any other secular building in the country, it presents a vision of a democracy built through centuries of tradition and reverence to the Crown. As John Bright commented in 1865, it is the ‘mother of all parliaments.’ New members are inducted to the strange ways of the palace from the very start, when they are presented with coat storage complete with sword hook. The day begins with “prayers” and a Speaker’s procession through the beje welled and mosaicladen Central Lobby, where a police officer announces to those present ‘hats off, strangers’,

Cameron Scheijde is a researcher and journalist based in London. He holds Master’s degrees in Political Theory and African Studies from the University of Oxford.and one must remove their headwear. Until 1998, members had to quickly don a collapsible hat if they intended to make a point of order; the Speaker would not hear them without it.

Many, perhaps most, of these traditions are indeed as ancient as British parliamentary democracy, though identifying precisely when rules about hat wearing and prayers began is difficult. On first viewing one might think that the palace itself might have prompted these parliamentary oddities — both the Lords and the Commons chambers are far too small for the num

ber of members, and the Lords area of the palace is constructed around the supremacy of the monarch, with portraits and busts of sovereigns dating back to the Normans.

However, the reality is that most of the palace is a masterpiece of set design, a relatively modern building — with the exception of Westminster Hall — constructed in the 1850s with the intent of creating a perfect environment for quirks, oddities and invented traditions. It was rebuilt after fires destroyed much of the old palace, and its choice of design illustrates a Victorian obsession with national mythology. The modern State Opening is one of the most publicized displays of this invented culture: the monarch arrives in a golden state coach built in 1851, walks through the Sovereign’s entrance finished in 1860, and announces the government’s planned legislation in a Chamber constructed in 1847, wearing the Imperial State Crown, designed in its current form in 1932. Most of the ceremony dates back no further than Queen Victoria.

For context, this places the Palace of Westminster, with its sword hooks and Norman kings at about the same age as the United States’ Capitol Building, whose domed roof and surrounding corinthian capitals date to 1866. The

bolism and representation. It feels as though everything in Washington comes in a set of 50. A history of revolution has necessitated a design that makes no secret of inventing histories, from the usage of neoclassical Greek architecture to the gridbased physical distribution of the legislature, executive and judiciary. Back in Westminster, a closer look at the palace might betray its age. Despite its crumbling fixtures and wellpublicized rat infestation, the physical

White House predates much of the Houses of Parliament. Yet the story Washington hopes to tell is, unsurprisingly, altogether different. A custombuilt capital city, every corner filled with a similar appeal to sym

layout of the place is far from organic: one can stand in Central Lobby and look directly from the Speaker’s chair in the Commons to the throne in the Lords. It is a physical manifestation of British parliamentary democracy as it purports to operate today, not an ancient, untouchable cocktail of tradition, convention and extremely cautious reform. Rather, it is an invention of a period of history defined by an obsession with being seen. Historian Kelly Mays describes this Victorian mythbuilding as the ‘“rearview mirror” of the future’; as ‘nineteenthcentury Britons imagined their own present one day becoming the object of the same sort of scrutiny, fascination and misinterpretation to which they subjected the past’, they ‘habitually sought to make the present present, by imaginatively looking back at it from the future.’ The spoils of aggressive, violent colonialism no doubt aided this endeavour.

If the customs, traditions and physical building of the heart of British politics stretch back barely 200 years, how should

this change our attitudes to reform? Firstly, by viewing the building as a piece of cultural heritage to be protected, separate from the politics that occur inside it. Invented or not, it is a masterpiece constructed out of the embers of a palace brought down twice by fire, allowing the current version to succumb to the same fate would be an act of cultural vandalism. Secondly, and just as importantly, by critically reflecting on the role these customs continue to play in British politics. Beginning the day with prayers might not present a large democratic challenge, but reserving a role in the legislature for clergy does. Finally, by being less careful with the metaphorical bonfire of tradition: customs are invented, and can be abolished and reinvented with similar ease.

Adopting bold, largescale democratic reform such as abolishing the Lords or moving MPs out of the pa lace altogether and construc ting a chamber that can ac tually fit all 650 of them are less of an intrinsic institutional threat when the flimsy historical grounds upon which these institutions are built are seen in their full light. One could even begin to consider abolishing the monarchy.

Like the Wills Memorial, the Palace of Westminster is a beautiful, iconic folly, designed to look centuries older than it is and to uphold certain values of tradition and consistency with the past.

Decoupling the palace and the work that takes place within it would transform how politics is done in the UK, and present the unique opportunity to be re volutionary and forwardlooking in democratic design. The demands of modern politics require it.

“Customs are invented, and can be abolished and re-invented with similar ease.”

“The White House predates much of the Houses of Parliament.”

Beards have been an indelible feature of India’s social and political landscape. While an almost entirely bearded cricket team represented India at the World Test Championship in 2021, the country has seen four bearded men in the prime minister’s chair over the past three decades. The semiotics of beards across the political spectrum in India — asceticism and masculinity — are ubiquitous. Although India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi and the opposition politician Rahul Gandhi come from contesting poli

tical camps, the invocation of ascetic imageries is a common strategy in their respective political guidebooks for popular appeasement.

Prime Minister Modi spor ted a fullgrown flowing beard between 2020 and 2021, which was seen by many to have given him a sagesaviour persona during one of the most devastating periods for the country when COVID19 infections were surging and lockdown induced a brutal economic slump. The initial speculation that it may have been a message to promote physical

distancing behaviour quickly proved unfounded when Modi continued to grow the beard well after the national lockdown was lifted. This image transformation generated a range of reactions from Twitter users and seasoned political commentators alike. Modi’s new look inspired an array of comparisons — from Plato’s philosopher king to poetphilosopher Rabindranath Tagore, and from a masculine strongman to a Hindu nationalist ascetic. Keen observers viewed the Prime Minister’s newfound ‘fleecy magnificence’ as an attempt at ele

vating his status from a populist politician working at the whims of the electorate to a more spiritual leader who could lead the people out of a national crisis and onto the proverbial path of light.

Arguably, the image of Modi as a Hindu nationalist ascetic has been carefully curated over the past several years by the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). He is said to have left home for the Himalayas at the age of seventeen to live with ascetics for two years who taught him ‘to align himself with the rhythm of the universe.’ In 2019, the BJP shared pictures of the prime minister wearing saffron robes, meditating in a cave near the Kedarnath temple — a shrine dedicated to Lord Shiva, one of the Gods of Hindu Trinity. Leaving his wife

selfprofiteering tendencies. For instance, while addressing a rally in 2016 on the issue of corruption, the Prime Minister famously quipped, ‘arey hum toh fakeer aadmi hai, jhola leke nikal lenge (I am a hermit, I will exit with my little belongings),’ almost as if reassuring the gathering — and the nation at large — of his selflessness and good intentions.

daughter Indira Gandhi, and its youngest Prime Minister in Indira’s son and Rahul’s father, Rajiv Gandhi. Recently, conversations have been brewing around the bushy, unkempt beard of Rahul Gandhi while he was on the 150day long Bharat Jodo Yatra — a “Journey Bringing India Together” against hate and divisiveness — until January this year.

only a short while after getting married to pursue a public life, Modi’s separation from his spouse also bolstered his ascetic image, playing into the broader trend in Indian politics in which having no spousal or familial ties is interpreted as a complete devotion to public service. From a moralethical lens, the popularity of these leaders can be attributed to an appreciation for values such as celibacy and sacrifice in Indian culture. Moreover, the bachelorhood of politicians also seems to inspire a sense of confidence among voters that their leaders would not be motivated by nepotistic and

Furthermore, Modi’s persona has closely been associated with that of a Karmayogi — one who works without desire for the fruits of their labour. Elements of Karma Yoga or Karma Marg (Yoga of Action or Path of Action) have been found in Vedic and postVedic scriptures. It was, however, the Bhagwad Gita — part of the famous Indian epic the Mahabharata — which lent recognition to selfless action as a means of attaining spiritual liberation. In December 2022, senior leaders of the BJP lauded the prime minister as a ‘true Karma yogi’ for ‘putting the nation first’ despite suffering personal loss, as he continued with his official engagements right after performing his late mother’s last rites. Additionally, the Prime Minister’s victory speech after the 2019 elections was a performance of ‘ascetic humility’ aimed at amplifying the narrative that his humble origins are in sharp contrast with the dynastic politics that have operated at the helm of power centres in India for several decades.

Often at the receiving end of such derogatory attacks of dynastic privilege is Rahul Gandhi. Gandhi is a prominent leader of the Indian National Congress and scion of the NehruGandhi dynasty which gave independent India its first Prime Minister in Jawaharlal Nehru, its first female Prime Minister in Nehru’s

entrant to the Indian political scene, Gandhi sported stubble when protesting for tribal rights against land acquisition by the global natural resources conglomerate Vedanta Group in the Niyamgiri hills of Odisha. This constituted a pivotal moment in Gandhi’s political evolution. Championing an alienated community not only won him fanfare, but also granted the Congress Party a strategic advantage in actively reaching out to a social group that had once been a significant vote bank for the party. Gandhi’s Che Guevaraesque appearance seemed suitable for the purpose of projecting him as the messiah — further demonstrating the political power of ascetic imagery in Indian politics.

With his new bearded look, Gandhi drew all sorts of comparisons as well — including Karl Marx and Saddam Hussein. Image experts, however, have referred to this attempt at reinventing his image as the ‘Forrest Gump approach’ — an attempt to invoke the image of a wandering mendicant. Seen sporting a white Tshirt throughout the Bharat Jodo campaign, Gandhi and his saltandpepper beard also seemed to exude a ‘son of the soil’ look, as opposed to the cleanshaven look which to many gave him an appearance of an immature youth. This strategy may help him break free from the label “Pappu” — one who is naive and inept at doing things — which has been used to mock Gandhi since the run up to the 2014 national elections. Addressing a press meet during the Yatra, Gandhi claimed that, ‘India is a country of ascetics, not of priests,’ and went so far as to call himself an ascetic. Notably, in 2010, as a relatively new

Asceticism and the use of its imagery is not new to the Indian political scene. Mahatma Gandhi’s ascetic activism is an early example of this usage dating back to India’s antiimperial nationalist struggle. The ‘halfnaked, seditious fakir,’ as Winston Churchill once described Gandhi, propagated ideals such as truth, celibacy, selfsacrifice, nonviolence, nonviolent resistance, and nonpossession as tools of not just political action against the British, but also social and religious reforms in Indian society. One of Gandhi’s biggest contributions to Indian political thought was popularizing a synthesis between the two inherently opposing ideologies prescribed in Vedic philosophy: nivritti (renunciation) and pravritti (worldly engagement). In attempting to reconcile the dichotomy between these two divergent worldviews, he made use of verses in Bhagwad Gita, which to him made it clear that ‘man cannot exist even for a moment without pravritti.’ Gandhi advocated the use of aus

“From a moral-ethical lens, the popularity of these leaders can be attributed to an appreciation for values such as celibacy and sacrifice in Indian culture.”

“Image experts, however, have referred to this attempt at reinventing his image as the ‘Forrest Gump approach’ — an attempt to invoke the image of a wandering mendicant.”

tere discipline and corporeal suffering required for sexual renunciation — otherwise a very private ascetic religious ritual — as a tool for nonviolent public action, the most

sponses to the British colonial imagination concerning Indian asceticism. The British saw ascetics as representative of what was problematic with Hinduism and a hindrance to their modernizing and “civilizing” ambitions in India. The idea of attaining a higher state of being and world renunciation, which called for “wilful idleness” and socalled “political apathy,” were seen as a social and political challenge to the British vision of “humane imperialism.”

to fanaticism. The wandering “fanatic fakir” who refused to lead a sedentary life, as well

FakirSanyasi Rebellion of the 1770s which inspired the novel Anandamath. Published as a part of the novel for the first time was a poem called ‘Vande Mataram,’ which later became the national song of India. Ascetics, therefore, have been an integral part of the nationalist struggle against colonial rule since its early days.

moral and highest form of political engagement, for Swaraj or political selfrule. The deployment of such means of political resistance were re

A popular subject for magic lantern show readings, the Indian ascetic and his way of life was stripped of its original cultural context and sensationalized by the British for the sake of entertaining audiences in the Western world. Taking a reductionist view of Indian spiritual traditions, the British defined the ascetics as “miserable men” and attributed their practices of austerity and bodily mortification

as a few highly organized ascetic militias who controlled many of the trade routes, posed a nuisance to the British administrators and their obsession with control, orderliness, and profits. The criminalization of ascetics after the British conquest of Bengal in the eighteenth century led to several clashes, including the

In today’s globalized and multicultural context, which promotes a profound appreciation for different spiritual and cultural traditions, the image of an ascetic might not appear to most people as the ‘male iconography of primitiveness’ they were once deemed to be. Seen in their unique contexts, it becomes apparent that both pogonotrophy and asceticism have been and will continue to remain central to India’s sociocultural milieu and national identity.

“One of Gandhi’s biggest contributions to Indian political thought was popularizing a synthesis between the two inherently opposing ideologies prescribed in Vedic philosophy: nivritti (renunciation) and pravritti (worldly engagement).”

“The idea of attaining a higher state of being and world renunciation, which called for “wilful idleness” and so called ‘political apathy,’ were seen as a social and political challenge to the British vision of “humane imperialism.””

Tanha Kashfia Kate is a student in the MPhil in Development Studies at Cambridge University.

The invention of the first nuclear bombs demonstrate that scientific discoveries can play an enabling role toward the state’s murderous ends. The detonations in Hiroshima and Nagasaki killed 130,000 to 215,000 human beings, either from direct exposure to the blasts or longterm side effects of radiation. Individuals from historically underrepresented backgrounds, who could have otherwise sympathized with the future victims of the bombs, instead contributed to the science that led to the detonation, including the PolishFrench scientist Marie Curie who codiscovered radium, HungarianGerman

American scientist and exiled Jew Leó Szilárd who invented the nuclear chain reaction, as well as multiple African American chemists, physicists, and mathematicians. In other words, members of any tribe, race, class, gender, religion, or belief system are capable of participating in collective brutality and horror should powerful stakeholders deem such a course of action necessary.

The realization that a small number of people — i.e. weapons manufacturers, buyers, and the policymakers on their payroll — disproportionately benefit from a world constantly on the verge of nuclear war

contrasts with the democratic promises of art, a medium presumably available to anyone wishing to indulge their creative aspects. Yet, the art industry regretfully reinforces various social inequities and operates, in large parts, like a plantation economy.

Visual art can nevertheless play a positive role as a form of resistance. Different visual art pieces concerning nuclear war can mobilise people through their depiction of material reality and alternative future scenarios, as well as by humanizing fellow members of the human community whom any group or state perceive of as “the enemy.”

My first visual encounter with Little Boy and Fat Man — as the bombs detonated in Japan were nicknamed — was through Stanley Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove, a 1964 film satirizing Cold War fears of a nuclear clash between the US and the Soviet Union. Dr. Strangelove stars English actorcomedian Peter Sellers in multiple roles, including US President Merkin Muffley, Group Captain Lionel Mandrake (a British liaison officer), and Dr. Strangelove, a wheelchairusing former Nazi and President Muffley’s primary scientific advisor. In one of the most iconic moments in film history, President Muffley intervenes in a confrontation between a highranking US general and the Russian ambassador, saying, ‘Gentlemen, you can’t fight in here! This is the War Room.’

The brilliance of Dr. Strangelove is difficult to capture fully in words, but the most important takeaway, driven home by Sellers’ multifaceted performance as a Nazi, an American president, and a British officer, is the fundamental interchangeability of these roles. The ease with which Sellers switches between characters at the boundary of victor and vanquished made me consider that the individuals that composed each of these groups were, ultimately, fellow humans who could be found to have much in common with their antagonists. WarGames (1983) is another film exploring the possibility of a nuclear winter. It stars Matthew Broderick as David Lightman, a high school hacker who unexpectedly accesses a US military supercomputer that controls the state’s nuclear arsenal. To prevent World War III and, therefore, the destruction of humanity, Lightman instructs the supercomputer to play tictactoe against itself. After

multiple simulations, the machine realizes that there is no winner in a nuclear war and that such a game is not worth playing at all.

The doctrine of Mutually Assured Destruction (MAD), as this condition of supposed equilibrium has since been described, was first coined by military analyst Donald Brennan. Brennan was opposed to MAD for two reasons: first, an extended deadlock accomplishes little to guarantee longterm US security interests. And, second, as long as people possess weapons of mass destruction, superpowers such as the US and the Soviet Union — and other countries with nuclear weapons in today’s context — will fight to achieve an advantage over the other.

Hence, Brennan advocated for an antiballistic missile defence system to eliminate enemy warheads before they could be detonated. Although the required technology was far from finalized, the Soviets also attempted to pursue an antiballistic missile defence; shrinking military budgets and the eventual collapse of the Soviet Union spelled the end of these attempts. Still, in the aftermath, visionary policymakers, including former US Senator Richard Lugar, led highly successful bipartisan efforts towards nonproliferation and arms control worldwide, although the reduction or total elimination of nuclear weapons is not yet a policy objective of any major world power.

There is an important distinction between the plots of Dr. Strangelove and WarGames While the strategy of MAD prevents the destruction of humanity in WarGames, a communication hiccup in Dr.

Strangelove between the base and its troops ultimately leads to a nuclear detonation. Put another way, Dr. Strangelove helps us consider that the nuclearweaponinduced end of life on Earth is inevitable as long as weapons of mass destruction exist and the activities maintaining the lifecycle of such weapons continue, even if adversarial parties decide to cooperate. So, as long as there is a risk of annihilation in the world that we actually live in, why do governments continue to build weapons of mass destruction? Why do global actors not have a plan of action to pursue complete disarmament as soon as is prudently possible?

In The Holy Family, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels make the following remark about history which can clarify matters: ‘History [...] does not use people to realize its own ends, as though it were a particular person: it is merely the activity of people pursuing their own objectives.’ In the context of nuclear weapons, then, most people (especially elite decisionmakers) have a personal belief about nuclear armageddon that keeps individuals merely pursuing their own objectives while not accounting for the devastating future effects of their actions. The belief is that the “other” will die, but “we” will somehow survive, even in a falloutdevastated landscape.

The distinction between

“them” and “us” when it comes to the harms of nuclear weapons, however, is largely fictitious. Consider that the US has conducted 1,054 nuclear tests — some within national borders, such as in Denver and New York — costing more than $100 billion and causing immeasurable harm to individuals, communities, and the environment. Furthermore, in the hyperglobalized world we inhabit, detonations in remote places may not be as safe as we might believe since every part of the Earth is functionally inhabited or is related to a community whose cultural and economic products could very well be a crucial component of the modern supply chains on which we all depend. In the aftermath of a nuclear detonation, gamma radiation from the fallout would penetrate even the best shelters and create health problems. Without large numbers of people to carry out socially necessary economic tasks, such as the production, distribution, and consumption of products and services, social systems would become significantly inefficient, even if supply chains were largely automated.

Additionally, the environmental effects of a nuclear winter cannot be understated. Entire species of nonhuman animals could become extinct, along with severe disruptions to soil health and global agricultural production. These impacts would be felt most directly by marginalized communities globally, such as black and other racialized people, women, disabled folks, and those already residing in climaterisky areas, should they survive at all. Such inequalities, which also shape the global wealth distribution, have already been shown to harm the functioning of healthy democracies in far too many “advanced” econo

“The distinction between “them” and “us” when it comes to the harms of nuclear weapons, however, is largely fictitious.”

mies, and would endanger the possibility of wellfunctioning postnuclear democracies. Ultimately, homo sapiens is a social animal. Given the material reality of our interdependence, we cannot afford to be so blasé about nuclear testing and the risk of detonation, whether near or far.

The risk of these harms results from the belief that mass violence is necessary for “our” safety, that there is no alternative, and that the militaryindustrialcomplex operating across both the Global North and South must wage war against humanity itself to guarantee “national interests.” Surprisingly, civilians often consent to, or even wholeheartedly welcome, the preparation and maintenance of nuclear capacity and disproportionate retaliation towards human beings “on the other side.” To illustrate, a 2015 Pew Research Center survey found that 56% of Americans believed that the use of nuclear weapons

during the Second World War was justified, with 34% saying it was not. In Japan, however, 14% said the bombing was justified, versus 79% who said it was not.

There is significant opposition to nuclear weapons from nonnuclear weapon states, but elite decisionmakers and intellectuals rarely heed such calls. A painful reminder of such inaction in the face of democratic opposition is Picasso’s Guernica, a large black and white oil painting currently housed in Museo Reina Sofía in Madrid. A gored horse, a bull, screaming women, a dead newborn, a mutilated soldier, and flames represent the anguish caused by arbitrary exercises of violence. Picasso produced the piece at the request of Spanish nationalists in response to the bombardment of Guernica, a rural Basque town in northern Spain, by Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy in 1937. The Allied powers, in response, posed no

meaningful opposition. Guernica was presented at the 1937 Paris International Exposition, as well as at other venues across the globe. Although Guernica did little to prevent the Second World War, it remains relevant today as a reminder that the establishment, alienated from the material realities of the global majority, often treat the lives of regular citizens as nothing more than a score in a computer game to enhance their power.

sequent reliance of the US and the Soviet Union on nuclear weapons undermined both international legal instruments. Today, research into weapons promising to kill “better and faster” continues to be backed by education institutions, corporate establishments, and government facilities.

The gaze through which our individual lives are viewed as disposable is reminiscent of a quote from I Am Cuba, Mikhail Kalatozov’s 1964 anthology drama, where a personified Cuba says: ‘Look! I am Cuba. For you, I am the casino, the bar, the hotels. But the hands of these children and old people are also me.’ Policy and security discourse, especially in the face of nuclear threat, often drown out the multiplicity of human voices for the ease and convenience of elite strategists, government officials, and private actors.

Democratic contestation surrounding nuclear weapons and the regimes that sustain them continue to gain popularity, owing largely to the work (often uncompensated) of multiple international and local grassroots actors. However, the successes of these initiatives are obstructed by the lack of readiness on the part of state officials. For example, although two watershed milestones in international law were produced in the aftermath of the Second World War — the adoption of the United Nations (UN) Charter and the Nuremberg Trials — the sub

Most recently, the 2017 Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) established standards of international humanitarian law (IHL) that apply to all governments and deemed nuclear weapons as violating IHL. Still, the five nucleararmed permanent members of the UN Security Council, the United States, the United Kingdom, France, Russia, and China, have all opposed the TPNW. Due to these countries’ lack of political will and other shortcomings, we, as citizens of this world, are resigned to depend on a security system that is ethically, legally, and intellectually corrupt at its core. All of us must figure out how to learn and teach the difficult lesson which our irrational self does not want to believe: collective state organized violence and war — and the profits they make for private stakeholders — will never make us safe. Frightened and worried as we might be, the worldwide danger we live with today can only be quelled by an enduring peace where we are free from the fear of any weapon of mass destruction. The pursuit of real security, in a democratic fashion that leaves no one behind, requires not only that we organize vigorously and unapologetically around our objectives but also that the leaders of our world, who continue to obstruct complete disarmament, stop pursuing theirs.

“Our individual lives are viewed as disposable.”

Avi Shlaim is Emeritus Professor of International Relations at the University of Oxford. Fonie Mitsopoulou is a writer currently based in Cairo.

Iwould like to start off by talking about your intentions behind writing Three Worlds: Memoir of an Arab-Jew. Did you come into it with the intention of recounting some really interesting stories that you’ve experienced? Or was it to shed a light on these issues that you’ve been writing about from an academic perspective for so much time, but instead from a more personal angle?

My academic discipline is international relations. And my main research interest is the ArabIsraeli conflict. So I always knew that the main victims of the ArabIsraeli conflict are the Palestinians. In 1948, when Israel was born, they suffered. In Israel, it’s

called the 1948 War, the War of Independence. For the Palestinians, it was the Nakba, the Catastrophe.

But, much later in life, in the last decade or so, I began to realize that there was another category of victims of Zionism. And that is the Jews of the Arab lands. And that’s when I became much more interested in the history of the Jews in Iraq, and the history of my family, and the impact of the Zionist movement on our community. One major factor that enabled me to start writing [my memoir] was reading a book by an Israeli scholar, Orit Bashkin. She wrote a wonderful book, New Babylonians, a history of the Jews in Iraq in the first half of the 20th century. And I learned a

huge amount from this book about the place of the Jews in Iraqi society. And having read that book, I was able to place my own story and my family’s story within the wider context of the Jews of Iraq — more broadly, even, Arab Jews, and the impact of the Zionist movement on Arab Jews.

It is quite interesting to think about the oral histories of your family being passed from [your mother’s] grandmother to herself to you. I was wondering how you made the decisions on how to situate your stories within the wider political context of the time?

Yes, that was an issue that preoccupied me because my book is not a traditional au

tobiography, which is simply about the person who is writing it. And, therefore, the key challenge was to interweave, to combine, interlace the personal with the political. And I tried to do this as best I can, by telling my story, or in the case until we moved to Israel, the family story, but set it against the wider canvas of what was happening in Iraq at the time.

So the book is chronological. And at every stage, I tell the family story against the wider background. For example, in 1948, when the war in Palestine broke out, the Jews were very, very insecure, uneasy, because they were associated with the Zionist movement. And it was a period of anxiety for Iraqi Jews and for my family, because Zionism gave the Jews a territorial dimension, which they didn’t have before. Until Israel was born, we were a minority in Iraq, just one minority among many — were treated no better, but no worse, than the other minorities. And there was a long tradition of religious tolerance in Iraq. So unlike Europe, which had a Jewish problem, Iraq did not have a Jewish problem. Nor did it have a history of antisemitism. Antisemitism is a European malady. From Europe,

it was exported to the Middle East. And interestingly, there was no antisemitic literature in Arabic. So European literature had to be translated.

We, the Jews, had been in Iraq since the Babylonian exile two and a half millennia ago. We were not newcomers. We were not outsiders. We were there long before the rise of Islam in the seventh century. But Zionism changed all that. Or, perhaps I should say, nationalism changed all of it. Because nationalism is a very divisive, a negative force. For nationalism, you need enemies. And nationalism is divisive be

er was the Zionist movement, which was in the process of dispossessing the Palestinians from Palestine and taking over the country.

So, once Israel was created, it was possible for Iraqis to say to Jews, ‘You’re not from here. You don’t belong here. You’re outsiders. You are the allies of the Zionists who are dispossessing Palestinian brothers.’ And also there were rightwing parties, like Hizb alIstiqlal, the Independence Party, which attacked the Jews and regarded them as a fifth column. Having been a very positive and constructive element in Iraqi society, the Jews now were viewed as a problem, as the outsider. And that was the background to the persecution at the official level that began a persecution of the Jews by the government after the end of the 1948 War.

flict about land. There were two peoples in one land; this is what the conflict is about. And to put it even more simply and crudely, it’s a real estate dispute over land. But obviously, there are different layers to this conflict — religion is one of them.

tween us and them, We and the Other. So, the two forces that changed the situation of the Jews in Iraq for the worst: one was the rise of Arab nationalism in the 1930s and the oth

To what extent does religion make a nation? Because, on the one hand, you talk about how you are, in a way, a proponent of a one state solution. You talk about how easily, in Iraq, Jewish people and Muslims could coexist until a certain point. On the other hand, you point out that when Iraq was created, it was created in a way that did not account for different religious groups.

As a continuation of this question, what was your family’s experience like going to Israel, having come from a very different background and very different culture, different language from all the European Israelis. Was religion enough to create a sense of nationhood at the time?

The role of religion is not crucial. In the ArabIsraeli conflict, it’s a factor. But the ArabIsraeli conflict is basically conventional geopolitical con

And, in fact, religion has been of growing importance in this conflict. For example, look at the rise of Hamas within the Palestinian community. But that’s not what it is essentially about. Judaism is a religion. It’s also, as Martin Buber said, a civilization. And there is a rightwing view associated with the Harvard professor Samuel Huntington called “clash of civilizations,” which says that conflict in the mo dern world is not between countries and nations, but between civilizations. And I think this is a really silly and superficial notion. But it was taken up by some rightwing Israelis to say that the conflict between Israel and the Palestinians is not a traditional conflict. It’s a clash of civilizations.

And what the story of my family demonstrates is that there was nothing preordained about hostility between Muslims and Jews. Arabs and Jews will live very happily together for generations. It’s nationalism that got in the way. So the problem that my community faced in Iraq was not a cultural one. It’s a political one. We were ArabJews. We spoke Arabic. Our culture was Arabic. Food was Arab food, Middle Eastern food. My parents’ music was a very attractive blend of Arab and Jewish music. So that’s the key point in the book: that the problem which led to the displacement of the Jews of the Arab world to Israel was not cultural or religious or ideological. It was political. The Zionist project of an independent Jewish state in Isra

“Iraq did not have a Jewish problem. Nor did it have a history of antisemitism. Antisemitism is a European malady. From Europe, it was exported to the Middle East. “

el created a deep rift between Jews on the one hand and Arabs on the other hand.

You mentioned before this feeling of being between three different worlds. Could you expand a bit on how your identity was formed spending all those years in the UK, also being raised by a family that felt distinctly Arab but having spent a lot of the formative years growing up in Israel? How do you think this has impacted you and the thinking behind this book?

The three worlds are Iraq, from when I was born in 1945 until 1950, when I was five years old and we moved to Israel. Then Israel, from the age of five to 15. And London, where I went to school from the age of 15 to 18. And when I was an international relations scholar, I didn’t know anything about social history. Only international history — history from above, not history from below. And very naively I thought that we are given an identity and off we go.

But when working on this nov

el, trying to make sense of my own life, I learned that identity is a much more complex thing. First of all, we all have multiple identities. But secondly, we don’t entirely form our own identity, it’s formed for us. And not only by positive forces, but also by negative forces. In my case, my initial identity was that of an ArabJew. There’s no better way to describe my first identity. I was an ArabJew. But in Israel, the term ArabJew is very much frowned upon. It is

erased my Arab identity and gave me a new identity as an Israeli. And this affected me profoundly.

said to be an ontological impossibility. You’re either Jewish, in which case you’re not an Arab, or you’re an Arab, in which case you are not a Jew. But for me, the hyphen in ArabJew doesn’t divide. That hyphen unites. And Zionism largely affected my identity. It

The book starts with an episode when I was about 10 years old, playing with my friends in the street in Ramat Gan, wearing shorts and sandals. And my father comes towards us and he looks foreign. He looks alien. He wears a three piece suit with a white shirt and a tie. And he speaks to me in Arabic. And I’m acutely embarrassed because Arabic is the language of the enemy. Arabic in Israel was considered a primitive and ugly language. So I’m acutely embarrassed, and I reply in monosyllables. What I wanted to say to him is that, ‘it’s okay to speak Arabic at home, but in front of my friends, I’d rather you spoke to me in Hebrew.’ But I was very confused and I just wished the Earth would open up and swallow me.

So that’s just one illustration of the imposition of an identity on a young and impressionable boy. And there was also the education that we all received at school. There was a