1 Volume 6 - Issue 3 December 2022

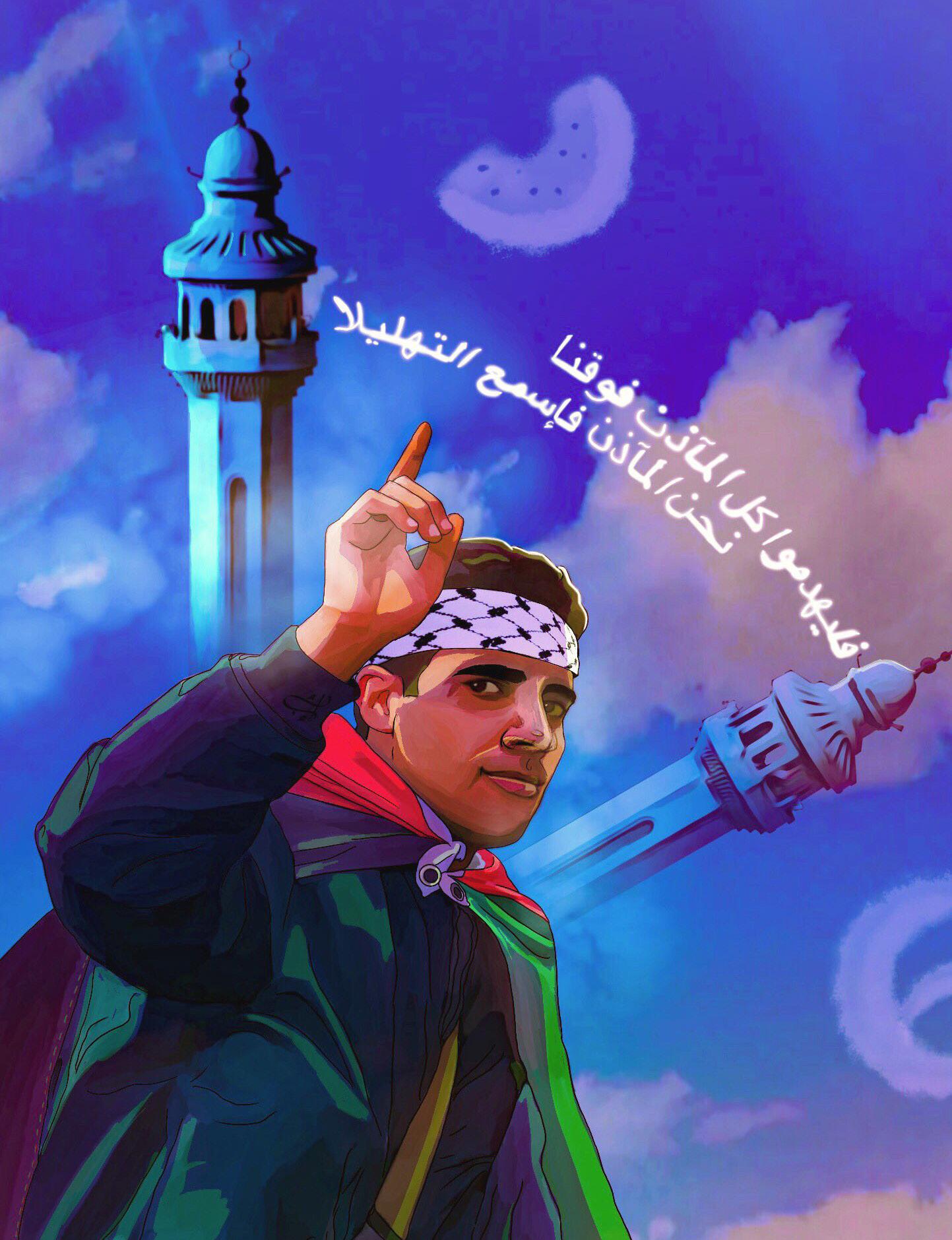

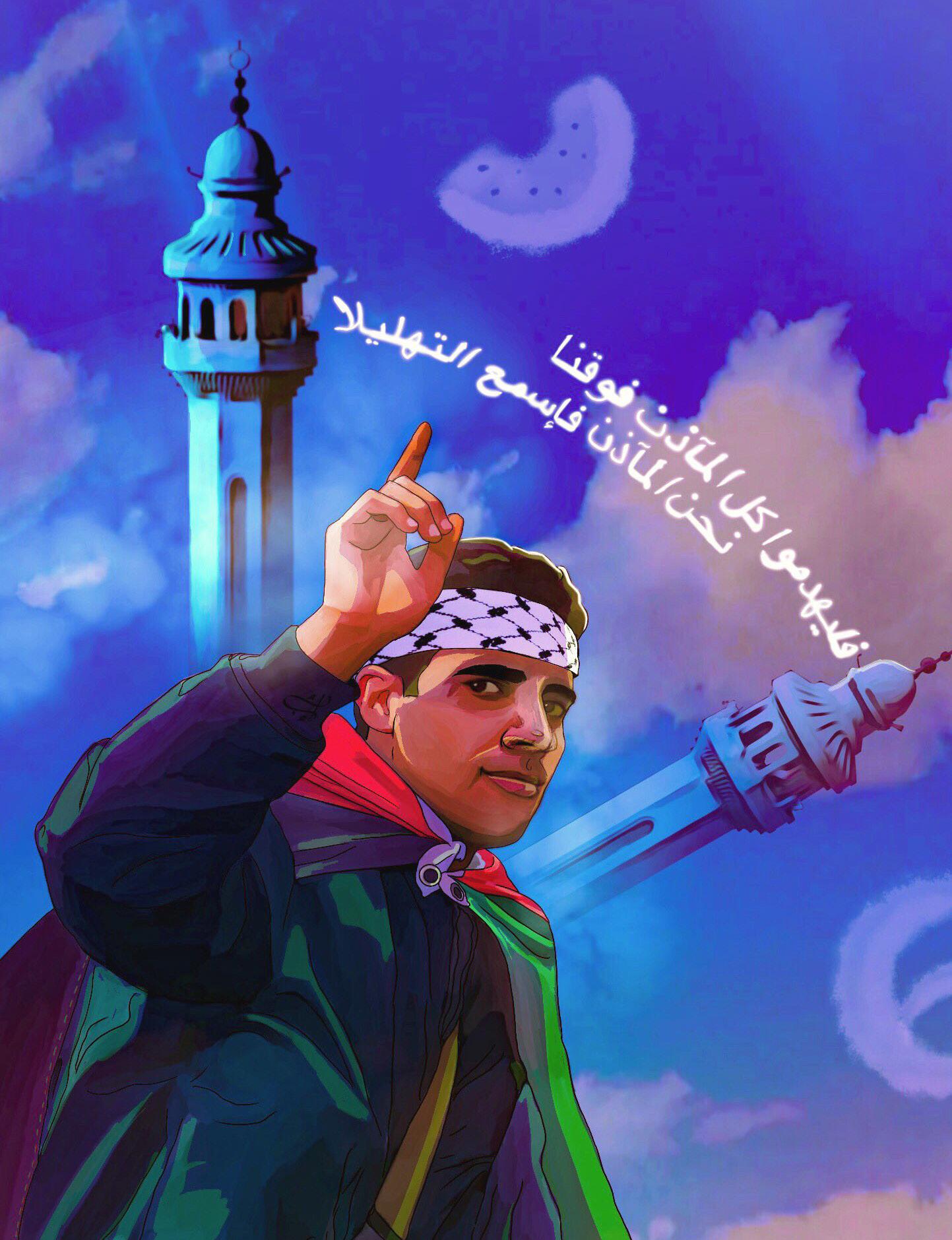

We’d like to extend a special thank you to Ibaa Al Rawahi for her beautiful artwork on the cover! Ibaa Al Rawahi is an Omani based Illustrator & concept artist for the animation, film, and game development industries. After receiving her BFA degree in Fine Art with a focus on animation at The Savannah College of Art and Design , she desires to further her skills and knowledge by working on story-driven projects that touch the heart! She hopes that she can produce an animated film in the near future that highlights stories from the Arab world but especially Palestine! You can follow Ibaa and her work on instagram at @ibaa.ahmed!”

2

Table

Hanna Nassar María Alejandra Torres García Lialie Mustafa Reem Farhat

Sereen Abdallatif Jamal Mustafa Zach Hussein Mona Mustafa Basman Derawi فيرشلا

3

of Contents

سدقلا ةنيدم نيبو ينيب بح ةصق يدنع Rania

يصقلأا يف يلصن حار 06. 08. 10. 12. 16. 17. 18. 20. 22. 25.

Under the Olive Trees New Light

Mustafa on Community, Change, and Hope We Met in the Summer Palestine, I Can’t See You The Things That Connect Us When You Leave Your Heart in Palestine The Lucky Guy’s Story

ىنمي

I am honored to share issue three of the sixth volume of Falastin. This issue, our theme was “Stories from Palestine.”

Because of the violent and forced ongoing displacement of our people at the hands of the occupation forces, we are very aware that “stories from Palestine” can take up very different forms. It is our intention that this issue reflects some of the diversity of the Palestinian experience, with stories from Palestinians living in Palestine, pieces from those of us privileged enough to visit Palestine in the summers, tales passed down from family members, and discussions of the ways Palestinians carry little pieces of Palestine with them all throughout the diaspora. Our contributors thought expansively and imaginatively about this theme, with pieces like Zach Hussein’s photo essay, “The Things That Connect Us” which explores how Palestinian identity manifests from thousands of miles away from home and Mona Mustafa’s “When You Leave Your Heart in Palestine” which shared her experience bringing her children to Palestine for the first time.

We encourage you to reflect on your own stories from Palestine, whatever form those stories might take, and to share those stories with us in upcoming issues. The work in this issue is a result of the beautiful artistry and creativity in our community. We are incredibly grateful to all of our contributors for their work! We are also thankful to our sponsors and the PACC Board for supporting this magazine each issue. Lastly, thank you, reader, for supporting Falastin each and every issue. We hope these pieces inspire you to join in our resistance through art by sharing your stories with Falastin and invite you to share this magazine with anyone and everyone.

Thanks to you, 2022 has been a year to write down in the history books for the Palestinian American Community Center (PACC). You celebrated the inauguration of Palestine Way with our first-ever Palestine Way Street Festival which attracted over 5,000 people from around the tri-state area. This was a moment that we will make sure to share with our great-grandchildren. Thanks to you we are able to continue to grow and improve with every passing year. You have had a direct impact on our community by holding over 30 programs this year with over 600 attendees. You helped facilitate 50 different events that reached over 10,000 people, 8 of which were part of our Palestine Monday series where you were able to nationally spread awareness about different parts of the Palestinian struggle. You engaged in 14 marketing campaigns centered around the Palestinian struggle and that highlighted our community. Through these campaigns, you have reached over 40,000 people around the world on our social media outlets. You were there for those in need and hosted 9 social service-oriented events and you were able to help over 1,500 people. You held 32 community outreach and civic engagement efforts that benefited about 1,000 individuals. You have accomplished much more than these numbers can attest to; you have shifted our community culture from one that may have shied away from its identity into one that is ready to speak out and speak for the Palestinian struggle. We hope you include us in your end-of-year giving at paccusa.org/donate.

Congratulations to our Falastin staff for launching the third issue of our sixth volume! I am so proud of Falastin and everything it stands for! Thank you to our sponsors for making this possible. Thank you to our Board of Directors for your continuous support! Thank you to our Falastin staff for their dedication and hard work! Thank you for reading Falastin and supporting PACC!

4

5

Artwork by Maisaa Al Mannai IG: @artisanalbym

Under the Olive Trees

Hanna

Nassar

In October of 1998, fall was at its peak and crisp air filled the villages of Palestine. Serene orchards of never-ending olive trees with ripe green olives ready for harvest filled the mountains of the tender red soil. My recollection of the whistling brisk wind blowing between the leaves in the stillness of the orchards brings me back to that exact moment. It was then I fell in love with this land and all it holds.

I never felt so connected to this country like I did during the olive harvest season. It was the pure simplicity of life that I will forever hold on to and crave. My heart yearns for the slow pace of everlasting days, long evenings, and pure bliss under the olive trees. These are the memories of an American Palestinian during the Palestine olive harvest season of 1998. Olive harvest season was a celebration for the Palestinian people, it was truly a holiday in itself. Joy and anticipation filled the Palestinian villages as everyone prepared for the harvest. Sensations of excitement spread throughout the villages as families gathered ready to begin the annual traditions. For the next few months, many Palestinian familes would began their challenging yet rewarding months of annual harvest. I was 10 years old when I was privileged to experience this humbling tradition; a tradition I will forever cherish and hope to one day experience with my own children. My favorite day began in the prime of the morning in October 1998.

The sunrise pierced through my curtains waking me up to the sound of the birds chirping and my mom in the kitchen. I stood aside watching my mom pack our supplies and a lunch to take with us for what looked like the entire village. We gathered with extended family at my grandpa’s plot of land overlooking the captivating view of our humble village. My aunts, uncles, and cousins were all wide awake ready for the harvest. I sat sleepily on the blanket my mom laid under the olive tree and watched everyone prepare

to begin their task. It was a tranquil moment, a scene out of a movie. My younger siblings and cousins ran around the trees and their laughter trailed through the row of orchards as everyone else socialized and began the harvest.

Midafternoon approached; buckets were now filled with plump olives spilling from the brim. Our fingers were stained from hand picking the olives and our clothes looked like they hadn’t been washed for months. My mom and aunts prepared the lunch and called us all over to eat. We all gathered under the olive tree and ate one of the tastiest picnics I have ever had. The warmth of the sun hit my back as I sat and enjoyed my mouth-watering watermelon was a moment of comfort and peace I will never forget. We enjoyed our delicious well-prepared picnic and watched the birds play in the trees as the sun rays shone between the leaves. As sunset arrived, we packed our belongings and headed home to rest for the next day of harvest.

Thus, the treasured memory of my experience under the olive tree will always be stamped in my heart. I like to imagine that the olive trees have secrets, and stories from the villagers that will be kept and held onto until the next harvest season. My mind will forever be flooded with visions of that day, a memory I will preserve, desire and never take for granted. I dream of the day that I am blessed with another harvest season in Palestine. Until then, I will carry on my story of a genuine and delightful time under the olive trees in 1998.

6

7

New Light

María Alejandra Torres García

To my best friend:

I’m sorry you had to slyly slip Palestine’s gold borders off your finger and into your mother’s hand in Newark Airport as El Al staff scrutinized the warm embrace of Allah’s silky love around her face

I’m happy you had Leila Khaled’s strength vibrate in your palm as they pried into your app-framed life

I’m angry that private accusatory fingers—nails stained with a Hate tip—dug into the hills of your body, when all you have ever cultivated is joy

I’m sorry that at the Tel Aviv (Yafa) airport you had to distort the melodies of your ancestors’ names and clip the origins of your tongue

I’m angry that you sat alone in a room where a revision of your parents’ story and erasure of their hawiya was your non-machine issued entry permit into your land

I’m happy that you washed their genocidal marks off your body and the gleam of your unwavering smile

8

Artwork by Melina

@melinasobi.art

bounced off the golden top of the Al-Aqsa Mosque at fajr

I’m angry we were pulled off the bus at a checkpoint and passed through security where you dimmed the light of your name and emptied your bag, but not your dreams

I’m sorry the blasphemous graffitied gash scorched the peaceful roots of your olive trees, but it did not separate you from Leila Khaled

I’m happy the chanafah greeted you and your father’s childhood home in Al-Jeeb nourished you

I’m angry sound bombs teared through your silent prayers in the Al-Khalil Mosque

I’m sorry you witnessed our bus driver burn his tongue with colonizer languages to demand passage through a checkpoint into Ramallah after we were randomly denied

I’m happy the souls of your elders traveled through the soles of your dabka

I’m happy the breeze off the Mediterranean Sea tickled your curls and whispered the name of your future daughter: Haifa and you navigated Akka with your zaghreet, your shoulders rolling to the rhythm of the sea as it clapped under you

I’m sorry that our taxi driver in Bethlehem did not have the right permit to drive from one holy city to the next because the military occupiers like to play God and there are too many Palestinian martyrs and humans must squeeze through bars (is that what they mean by “humanitarian”?) to pass

I’m angry the Zionist eye tracked your kufiya-ed prance through Al-Quds and rifles attached to two teenagers stopped you on your way to buy gifts for Palestinians who have intergenerational souvenirs––freedom is not a refrigerator magnet

I’m happy the cadence of the kufiya flowing around your hips in the breath of the Jordanian valley sprinkled its flowers

I’m sorry you had to pack your memorabilia in someone else’s luggage only to be clawed and scanned at the airport by devices that did not register your pulsating heart

But I’m happy the echoes of your laughter will remain in falastin

And I hope one day you are on a road that leads to a free Palestine entrance to which is dangerous for white settler colonizers

InshAllah.

9

Artwork by Zachariah Hussein IG@zachhusseinvisuals

نيبو ينيب بح ةصق يدنع

Lialie Mustafa

Growing up, I had the privilege to be able to visit Palestine almost every summer. The summer of 2022 was by far one of the most memorable summers of my life so far. I was privileged to visit Palestine for six weeks and deeply and critically explore my country to truly connect with the land.

The most memorable part of my trip was Jerusalem. Right off the bus, I made it into an office across the street from the Damascus Gate. The office is around 100 years old and one of the oldest around. From there, I was able to get onto the balcony and see the entire old city in front of me. The sound of the cars zooming by, children laughing and running around on the sidewalks, vendors selling falafel sandwiches, and the view of the Dome in the Rock in the distance to top it all off was exhilarating.

I found myself thinking: this feels like home, this is home. Standing in front of Bab Al-Amoud (Damascus Gate) marks your entry into the old city of Jerusalem. It’s impossible to not just stand in awe and look around and absorb your surroundings. I saw the view of Jerusalem from the Mount of the Olives, walked through every quarter, made my way into the many Churches in the Armenian quarter, walked through the Jewish quarter where I encountered a Jewish neighborhood, and even stopped by at a family’s house who resided in the Old City and was able to hear their story of how the occupation impacts them living here everyday.

I ended my trip by praying in the Dome of the Rock. Every wall, street, and corner had a story behind it with a historical significance. I couldn’t stop thinking to myself how grateful I am to be here at this moment and how badly I did not want it to end. I remember our tour guide, Osama, telling me نيبو ينيب بح ةصق يدنع سدقلا ةنيدم which translates to, “ I have a love story

between me and the city of Jerusalem.” At first I did not understand what he meant, but after the day ended it finally clicked in my mind and I understood and realized that I also have my own love story with the old city- along with everyone other Palestinian who lives and has visited Jerusalem. This was the connection to the land I was always looking for, and it felt like all the pieces had put themselves together. The rich history of Palestine will live on forever and I am grateful to have the privilege to experience Palestine and its beauty= from Jerusalem all the way to my village, Mukhmas. Thank you, PACC, for providing me with this experience to go on this trip, I am forever grateful. And thank you to our tour guide, Amo Osama, who took us around every inch of the old city that day and gave the most memorable tour of Jerusalem. Until Freedom.

10 سدقلا

ةنيدم

Photo taken by Lialie Mustafa IG: @photosbylialie

11

Photo taken by Lialie Mustafa IG: @photosbylialie

Rania Mustafa on Community, Change, and Hope

Reem Farhat

Anyone familiar with the New Jersey Palestinian community can recognize Rania Mustafa. As the executive director of PACC, she is a pillar in our local community, a smiling and energetic face, and someone who is truly committed to cultivating community. I’ve had the privilege to grow up in the center, from my sophomore year of high school to my last semester of graduate school, PACC has been there for me. Rania has been a mentor and a big sister to me personally, which is why I am honored to interview her for this piece and to highlight all of the amazing work she’s done in these past nine years as executive director at PACC. I can speak first hand to the transformative effect that this center has had on our community under her leadership. And while it’s bittersweet to see her transition out of her role as Executive Director, we are all so excited to watch her continue to transform the lives of people around her.

Take us to the beginning, how did your journey as the Executive Director of PACC start?

The journey started when I graduated college. I graduated from NYU in 2014. And at the time, this was just like an idea to start a community center. So we did things a little bit backwards, where they purchased the building, but then they didn’t know what to do. So I was approached, and they’re like, “What do you think about, basically applying for the position?” At the time, I was unsure because I planned to go to grad school and was taking a gap year. And I thought to myself, you know what, I’ll just apply. I have been involved with nonprofit community work in a more formal capacity since I was 16, –I just always wanted to do different things for our community. I’ve always been very community oriented, and that’s what drew me to the idea. I also felt like our community was missing something and we needed to change our game and I want it to be involved in any new initiative. Our initiative was to

have a center focused on Palestinian education and a space for our community to do community activities.

What was it like in the early days of PACC?

We started in August of 2014. At first, our agreement was that I would start 20 hours a week and I would set my own schedule. I didn’t know what to do so I just started meeting with people that I knew were influential in our community or really cared about the community and talked to them about PACC and asked for their input. I would take notes and then we’d start with programming. The first program ever was actually ping pong, we had ping pong tables and different community members would come at night and play in a safe and relaxed setting. This was before I was even involved. But we wanted to expand to different demographics, so we started tutoring and dabka.

How do you think PACC has influenced the community?

I think it’s in three main areas. One, in terms of their Palestinian identity. I think I kind of epitomize this in a way. I was always very proud to be Palestinian. But you always felt like this need to kind of shy away from your identity sometimes because of the outside world and social pressures. And I think we definitely have increased the need for people to be loud and proud about being Palestinian, which I think is so important. And I see these little kids that literally were little kids with us when they first started and now they’re in high school or college, and they’re so loud and vocal about Palestine.

Second thing, I think we’ve gotten a lot more organized. We have a lot more people in political office, and I think this is a direct result of PACC. There’s a lot more push to get organized as a

12

community, there’s a lot more push for local representation. And that’s something PACC has worked to cultivate consistently.

And then the third way is I just feel like the community is more welcoming in a way than it was when we grew up. Communities were centered in either the mosques of the churches, but there was no other center of community. I feel like PACC is kind of like the catch all for everybody else. And that actually transformed the way I see things, because when I grew up, I grew up with the masjid. And for me, I thought that was everybody. But there’s a lot of people that just didn’t grow up with the masjid or it wasn’t the place they built community. And I think PACC gave people options of building community.

In terms of individual growth, what has it been like to watch people grow up in the center?

We’re in our ninth year of operation and for me, PACC’s magic is the way that people transform the way they think and the way people are coming out of the center as leaders. You have the kids that started at PACC when they were seven or eight and now they’re graduating high school. These kids don’t remember life before PACC and it’s actually so beautiful. PACC is just such an ingrained part of who they are and their world that they don’t even understand what life was without PACC and that is I think one of the most beautiful things because you see the indirect effect of it.

13

Photo taken by Reem Qasem

Through my work at PACC, I’ve seen the personal confidence growing, the personal growth as a leader, that’s really important to me. And I’ve seen that countless times where people come in, not having a sense of community, not having friends, and then they emerge with a strong sense of community and a strong support network. Also their understanding of Palestinian identity. Someone could be like, my great grandfather, lived in Palestine but I’ve been a couple generations removed from Palestine, what does that mean? And what does that look like? That’s also something that’s been beautiful to watch and see people navigating their identity and then recommitting themselves in one way or another to give back to their identity.

What are some of the biggest accomplishments you are proud of?

The renaming [of Main Street to Palestine Way] is definitely one. I remember just standing there for a little bit to soak in the moment. I took a couple minutes and just was like, I need to soak this in. Because it was the culmination of years of work. I know it’s symbolic, and that it didn’t do anything for Palestine. But I was so happy about it because growing up, I remember thinking do we belong?

Another big accomplishment was our first PACC day in 2015. I remember thinking, how did we get all these people here? We had a full house with over 1000 people here. I was so shocked. It was a very surreal moment. We didn’t bring the headline speakers or anything, we just had out community members performing, but it was enough to fill the auditorium. So I remember thinking, we’re onto something with this.

Also, when we got a $50,000 grant from the state to organize around the census. I remember I cried, that was our first big grant we’ve ever received. And we were the only Arab organization or Muslim organization in the states that got it. So it was a huge honor.

14

Artwork by Amjad Al-Siyabi IG: @amjedalsiyabi

And then definitely 2020 was a big one.

What was that like, riding the pandemic through the center? Because I remember just as someone in the community, PACC was doing so much.

COVID hit and that’s when we put out a call. And I remember hesitating, I wasn’t sure if we should do it or not. But we did. My dad put out a message basically saying, “We’re here for you. If anyone needs anything, let us know.” And the floodgates opened, we were getting calls from all over the country.

For the first week or so, we kept referring out because we’re not a social service agency. Then the need became so great that we were like, “I guess we’re gonna become a social service agency.” So temporarily, we became one and that was crazy and a lot of work in itself. And that’s how we started doing community relief work. We also had one big donor donate 10,000 masks and sanitizers. Then we ended up giving out like countless packages of things that we started putting together and were serving the county and people from all over northern New Jersey.

Local officials started to recognize this. It was mutual aid. We never limited it to the Arab community ever. We did it for everybody. And I think that transformed the game for us. Because it’s one thing for you to say we’re here for you and then to actually be .

What went into your decision to step down as executive director?

I think a few things. Walking into this, this never was my long term thing. Second thing just from my knowledge of nonprofit experience and with the community, it’s really important that we pass on the baton. And my thing that I keep saying right now is I want to pass on the baton, when I still have the energy, I still have the time or I still have the love and desire to work for PACC, that I can help coach this next person to bring it to the next level. But if I’m getting to the point where I’m so burnt out where I

can’t do anything, then I am basically not continuing the legacy. I’m just ending it there. And my goal since day one is to make PACC run in a way that it runs so well without me. I don’t want it to run just with me. Because if it’s running without me and running without the first executive director, then that means this is an actual success.

What are your hopes for the future of PACC?

I hope that PACC is around for my great, great, great, great grandchildren. I want to get to the point where we are such a strong institution that’s unshakable. I think there’s a lot of internal work that needs to be done to get to that point, and I’m confident we can get to that point. On an external level, hopefully when we get to the point of stability, that we can emulate this all over the country, and that we create a coalition of PACCs that we come meet together, we discuss things together and we create the change Inshallah. That we get to see a free Palestine. Hopefully, we can keep these going until we all go back to Palestine. That’s my hope.

And then my last question is do you have any parting words for PACC community members listening?

I have so many things I want to say but one thing I always say is once a PACC family member, you’re always a PACC family member. This is an institution that made it this far because of the work of the community. And I want us to continue working on this as a community to continue this growth and to continue creating all this positive change.

15

We Met in the Summer

Sereen Abdallatif

This summer of ‘22, I roamed the unpaved roads of Palestine.

Finally one with my roots, she greeted me with a hospitable smile, Welcome home.

Her scent was nostalgic, like a long lost love–United in a world keeping us apart.

She showed me every side of her, Burning salts of the Dead Sea, Peaks of the Nablus mountains, The shimmering dome of Al-Aqsa, Her beauty was shy and humbling, Too bright for my prodding eyes. She implored me to explore every crevice, I craved to stay with her for eternity.

In the howling nights I treaded carefully, Where the soil met the sand, I wished it could stay this way. A familiar shadow loomed over me, Stained of blood and anguish; She urged me to live. Live for my people, live for who was lost, live for my country, It binds us, it courses through our veins; Urges us to fight for what is ours. Sorrowful tears threatened my eyes while my heart yearned deeply, As she showered me in her unrelenting strength.

How could you be so resilient? I weeped, She placed a dusty kiss on my cheeks; Saying she believes in freedom. Where children can roam the vineyards, And fear was only an idea, not a reality. Falastin, I admire you so.

16

Photo taken by Sereen Abdallatif

Palestine, I Can’t See You

Jamal Mustafa

Jamal Mustafa

An indistinct mirage. A preternatural fantasy. An illusion before me or a delusion within me?

I dream, I wake. I run, I stumble. I love, I hate.

It’s my homeland. I am told you are beautiful, The most eye-catching And yet I’m blind to see you. Can I not see or are you hiding?

I’m far, I’m near. I’m without, I’m within. I’m alone, I’m accompanied.

It’s my homeland. I resent you for not letting me see you, 16 years is too long. Are you still where I remember? Have you been taken away from me? Let me see, Are you real?

17

Artwork by Zachariah Hussein IG@zachhusseinvisuals

The Things That Connect Us

Zach Hussein

Many of the Palestinians living within the diaspora are two or more generations removed from living on their grandparents’ land; in fact more Palestinians live outside their homeland than in it. But despite this great distance, Palestinians abroad are still connected to their land. For many, this connection has been fostered by and lives through physical manifestations of Palestinian culture. What it means to be Palestinian is built by stories told of the times before occupation and items passed down through many generations that form connections with the homeland. It is also embodied in the tales of resistance and hardship to maintain identity.

Karma Al-Hashemi, a Palestinian/Jordanian art student in Brooklyn incorporates her identity into her artwork. Her paintings bring her back home and connect her to experiences that she has never lived in reality. Depicting Arab places, whether Amman or an imagined Palestine, her art tackles a feeling that many living away from the homeland experience: the very real yet “abstract and far away” idea of home. She was raised with a connection to Palestine, she said the connection was “brought to me through my mother, my grandmother, the food, and the dialect.” Despite being decades removed from her ancestors’ land, Karma projects her identity strongly and wants to make it clear to people that she is Palestinian. The culture remains in her life as a way of resistance. “I feel like my artwork is going to stay, it’s always going to be there so if I’m making art about the cause or about Palestine, I feel like that’s resistance.” To Karma, being a Palestinian “means being resilient and being a fighter in every sense of the word.” The fact that these notions can be found in someone who has never been to Palestine is threatening to the occupation, as evidenced by Israel consistently denying Palestinian Americans entry to their homeland. The idea that Palestinians can find meaning and love for their land from 70 years and thousands of miles away is powerful.

18

Photo by Zachariah Hussein IG@zachhusseinvisuals

Photo by Zachariah Hussein IG@zachhusseinvisuals

Being Palestinian in the diaspora, and holding onto that feeling is something that Karma believes is more apparent in the current generation of Palestinians living in the diaspora.“A lot of the people in our generation have a lot of anger towards what’s happening [in Palestine] and the generations that are coming are going to be even better than us,”said Karma.

Emad Khattab, a Palestinian/Jordanian studying Media, Culture, and Communication in Manhattan feels similarly. Though he and his parents have never been to Palestine, he said, “It’s always been something that’s so dear to who I am and how I identify.” He believes that by holding onto Palestine, and being in touch with the culture is actively taking part in the resistance. He manifests this through his necklaces, one in the shape of historic Palestine

and the other a medallion proclaiming “FREE PALESTINE.” They are conversation starters that allow him to bring up the struggle of Palestinians and share the culture, also acting as “a way for me to be constantly reminded of Palestine.” Emad’s resistance embodies the Palestinian ideals of the diaspora, where Palestinians use their “resistance power” as Emad puts it and are driven to be more determined through the distance from Palestine. “I would like to believe that my Palestinian identity in exile became more intense because I am in exile,”said Emad. Growing up being told romantic stories of the resistance crafts Palestinians like Emad into resilient fighters, ones who without weapons push for change from oceans away in the face of their identity being stripped from by both the occupation and integration into their homes in exile.

19

Photo by Zachariah Hussein IG@zachhusseinvisuals

For Brooklyn born Omar Ahmad, a Palestinian entrepreneur and chemical engineer who moonlights as an ambient music composer, visits to Palestine have made his experience of Palestine different from most in the diaspora. He has been able to go back to his grandparents’ village, albeit under the difficult conditions imposed by the occupation. He believes that there is more power in being from the diaspora, as they are able to make the conscious decision to endanger themselves in returning. “I’m making an active choice to go somewhere that is very challenging for me to go, that when I get there I’m detained for several hours, interrogated, questioned heavily in a very dehumanizing way and that actually bolsters my connection to the place,”said Omar. While Omar’s physical connection is more unique than some in the diaspora, both his parents and himself have no citizenship in the land they’re from, rendering them no more than guests in the eyes of the occupation. Omar channels his identity through various objects he has collected, “Seeing my grandmother’s tatreez hanging on my wall or this letter I received from a student at Birzeit University that includes her tatreez feels really distinctly Palestinian to me… they take me into a subconscious space that doesn’t have a physical home, a weird flow state that makes me feel tied directly.” Like most in the diaspora, Omar became Palestininian through the community he was raised in and through the distinctly Palestinian values his parents instilled in him, which were passed to them from their own parents. “Being Palestinian is being passionate” and it means to “live with a vigor and an intensity,” says Omar. He feels brought back to the land of his ancestors through small things, directly in the face of trauma he and his family have faced simply for being Palestinian. The feeling of longing and homelessness Palestinians in exile and diaspora feel is found across the diaspora. Not quite American, but not entirely Palestinian, Palestinians in the diaspora are made to struggle with a multitude of conflicting feelings and ideas. Being raised in a group of people with intergenerational trauma who all have the same stories of being

attacked and removed from their lands has led to the Palestinian diaspora in particular to embrace feelings of resistance and embrace their culture even more simply as a way to come together. For millions of Palestinians, being Palestinian was learned through their parents, grandparents, trinkets, dresses, food, and culture. The Palestine they were told about was one that was ravaged by a foreign enemy, one of loss and suffering. But it was not only that. It was the home of people who fight back, who resist without apology, who come together and express themselves despite an oppressing set of restrictions imposed on their own sense of being. The things that connect Palestinians, whether small or large, physical or manifested, are extremely powerful. The fact that people who have never experienced their own culture in practice still embody it and are willing to fight for it without tire is something deeply worrying to the occupation that is relentlessly trying to erase their identity, and is in a sense, one of the greatest weapons to defeat it and make the collective dream of return come true.

20

Photo by Zachariah Hussein IG@zachhusseinvisuals

21

Photo by Zachariah Hussein IG@zachhusseinvisuals

When You Leave Your Heart in Palestine

Mona Mustafa

“Where are you going ?” They asked me as the plane was ready to land.

“Palestine!” I exclaimed with all the pride and joy there was in my heart. As I uttered my reply it felt surreal the entire time. The fact that I was finally going back to my homeland after 12 years away from it, so many years and life changes later. I was no longer a young girl going with her family, instead I was now a mother of three bringing her own children to connect with their roots and find out where they come from.

“Where?!” Replied the passenger once more.

“I’m going to Palestine,” I reiterated as my eyes met the eyes of a woman on the plane who seemed to be deeply offended by my words. I thought nothing of it, but a few seconds later I overheard the woman speaking sarcastically telling her family, “Do you hear how she says it with all the confidence in the world as if she’s not going to Israel!?” She continued to let others in the plane know what I said as if I had committed a crime.

My heart shook with anger and pain and I was filled with confusion. How could my mere utterance of the word Palestine be seen as an offense? How could my pride and happiness at being able to say I was finally going back home to Palestine make someone angry?!

I explained to her that the place I am going to is indeed Palestine and that she should respect that. All I got in return was a smirk that I decided to ignore and move on from. This small encounter had taught me the lesson I needed to know going into my two month journey through Palestine. It taught me that despite the brainwashing and misinformation that seeks to erase Palestine from the minds of people like this woman I encountered and despite the maps

that may not show our names or our villages, we as Palestinians around the world in the diaspora or at home have Palestine written within us. There is nothing that can be done to erase this. Our seeds have been planted and our love for our homeland only grows deeper with every blow that is thrown our way.

That woman’s words motivated me to fall even deeper in love with the word “Palestine.” She made me want to use it in any conversation I can. She made me think deeply about the land I was on and because of her words, I was even more intentional in every beautiful corner of Palestine that I was blessed enough to step foot on. She symbolized to me those in the world who work hard to deny Palestinian existence, they are the reason why now even more than ever we have to strengthen our roots and work harder to make our voices reverberate as far and wide as they can.

Yes! I was in Palestine and it was a life changing summer that gave me the chance to live out my dream of both teaching in Palestine and having my own children be students there. I was given the amazing opportunity to work at Ramallah Friends School in the heart of my favorite city in the world. Here I taught middle schoolers in the “I Know I Can” Summer Academy and got to work one with Palestinian students, many of which were living in refugee camps such as the Shufaut camp.

I tried to show them how connected they could be with the rest of the world’s children and how much the world could learn from them. I saw and heard firsthand what life for children living under occupation looks like and despite their struggle, the loudest thing I heard was the immense amount of hope and light that these students carry. They are the future of Palestine and the ones who are strong

22

enough to grow up and show the world that Palestine deserves to be free from the shackles of occupation. I would love to tell this woman again that, “Yes! I spent my summer in Palestine and it was a dream come true.”

The cities I visited left their mark on me each in their own unique way. Ramallah, Alquds, Mukhmas, Nablus, Al Khalil, Msafer Yatta, Akka, Yafa, and Bethlehem are all Palestine. Every inch of the land is and always will be our beloved Palestine, the place where my heart still remains despite the miles that separate me from it.

I put my entire heart into this trip and got so much more in return. My identity as a Palestinian mother and teacher grew stronger. I know now more than ever where I come from and how proud I should be that I come from a land whose people do not give up. Instead, no matter what, they keep on smiling, keep on working, keep on living. They are the epitome of human strength.

Remembering that woman on the plane who could not accept hearing me say “Palestine” and all those who think in the same narrow minded way, it goes without saying, “Yes! Palestine exists, yes that’s where I was, and yes, no matter the circumstances that Israel or the world has put the Palestinian people through, they still wake up everyday and live life to its fullest. They create art, they open businesses, they study, they learn, they live!”

In the words of my favorite poet Rafeef Ziyadeh, “We Palestinians teach life after they have occupied the last sky. We teach life after they have built their settlements and apartheid walls, after the last skies. We teach life, sir!”

We will continue to plant the seeds of love and life in our children and the generations that follow them. I pray that we can all be blessed with many more opportunities to visit our beautiful homeland and remain connected to it no matter where we are in the world.

23

Photo taken by Mona Mustafa

The Lucky Guy’s Story

Basman Derawi

The lucky guy’s story

Basman Derawi

After 2019, I have been nominated For being “The luck guy,” A title for honoring me Traveling twice outside Gaza.

If that happens to me A third time, Most probably the big vein In my head would explode From the blessing and Die even before.

Most of my friends have Never been outside Gaza. Never received the opportunity or The permission to travel. Many of my people have lived And died seeing only one place.

But what I share with my friends We’ve never seen our homeland. The occupation never allows us to. My friend has never seen Jaffa, Sitting with his grandfather on Its shore and fishing.

I have never been to Beersheba. Never been able to sit under My grandmother’s olive tree, Watching here as she’s baking Taboon. I have been to Europe in 2019 And through the hard journey to Get there I was laughing too hard on How Europe can be an easier option Compared to my homeland. A kind of laughing that makes you bite The skin of your lips and bleed.

Yet every time I look at Photos of Palestine And close my eyes. I see her shining into my head Like an eternal skin, My heart gets warm as If I have been hugged by my mother.

I never try to explain this phenomenon Or ask why As if I already know that God dug Palestine into my heart, Into my DNA. As the olive tree digs its root Into my grandfather’s land.

24

25 يصقلأا يف يلصن حار فيرشلا ىنمي نامك انتغل اوقرسيام لبق يبرعلاب يكحأ ينولخ نامك ينولتقي ام لبق و انحإ ينباي ،نامز يلاكح يوبأ يصقلأا يف يلصن حار ةعمجلا و ديعلا ةلاص يلصن حار كباحصأ و كناوخإ عم بعلت و ضكرت حار ؟ىصقلأا نيو و ؟يوبأ اي ىتم؟ىتم سب انودسي مع يللا لاجرلا نم ىصقلأا فياش شم انأ مهولتقي مع يللا لاجرلا و يسان و يوبأ و يمأ فياش رابك تلايع اومسرب لافطلأا لك شيل ؟انسفن ريغ ادح مسرنب ام انحإ و ينم اهوذخأ ةفانك و يلاود انلمعت تناك يللا اتيت ىتح ايفوك يلطيخت مع تناك يللا اتيت هورمد مهلك يللا نوتيزلا رجش اهدنع تناك يللا اتيت، نوتيزلا تيز مهنم لمعت تناك يللا اهدياب نوجعم نخسلا زبخلا و رتعزلاب نوتيزلا تيز طخلا نف نسحأ بتكي ناك يللا وديس ىتح هنم اورتشي ناشلع رود ع نيفاص اوناك سانلا و تايولح يرتشن ناشلع ناكدلا دنع انذخاي ناك يللا وديس تايكحلا نسحأ انليكحي ناك يللا وديس يف مهعم ضكرأ و معم بعلا تنك يللإ يناوخإ ىتح ينم مهوذخأ ،ةسه مهعم شيعأ مع يتح وأ ،للاطلأا ةقورسم يضرأ ،ملاع اي مهعبت اهنإ اولوقيب يللإ يضرأ انعبت اهنإ نيدكأتم انحإ سب لوسرلا مايأ سدقلا هاجتإ اولصي اوناك و انيمحي حار انبر اندنع سب ةمحر اودنع ءامسلا يف انبر ةمحر مهدنع ام ضرلأا ىلع يللإ لاجرلا نكل عم انولتقيل ةحلسأ ريغ مهدنع ام رمحلأا نوللا ريغ مهيديأ ىلع نول مهدنع ام و اتيت مد و ايوبأ مد و يمأ مد و يسان مد نول رمحلأا نوللا ياه وديس مد لاطبلأا لثم اوبراحب نيينيطسلفلا نإ اولوقيب اوناك انلثم اوبراحي مع لاطبلأا نإ موي ولوقي حار سب انضرأ كرتن حار شم ىصقلأا يف يلصن حار ،

We Will Pray in the Aqsa

(translated poem from page 25)

Yumna Elsherif

Allow me to speak in Arabic before they steal our language too

And before they kill me too

My dad told me long time ago, son

We will pray in the Aqsa

We will pray Eid and Friday prayer

You will run and play with your siblings and friends

But when? When dad? And where is the Aqsa?

I can’t see the Aqsa from the men that are blocking it

All I see is my mom, dad, and my people while the men are killing them

Why do all the children draw a big family, And we only draw ourselves?

Even my grandma who made stuffed grape leaves and kunafa for us, they took her from me

My grandma who would sew me a kufiya

My grandma who had olive trees that they took all down, the ones she used to make olive oil from

Olive oil with thyme and hot bread made from scratch from her hands

Even my grandpa who used to make calligraphy so great that everyone would stand in lines to buy from him

My grandpa who would take us to the convenience store to buy candy

My grandpa who would tell us the best stories

Even my siblings that played with me and ran around in the ruins, or even lived with me, they took them from me

Oh world, my land is stolen

My land that they are saying it belongs to them

But we are sure that it belongs to us

And they used to pray towards Jerusalem at the time of the Prophet

But we he have our Lord to protect us

Our Lord in the heavens has mercy

But the men on land don’t have mercy

All they have is weapons to kill us with

They don’t have any color on their hands except red

This red color is the color of my people’s blood, my mom’s blood, my dad’s blood, my grandma’s blood, and my grandpa’s blood

They used to say Palestinians fight like heroes

But they will say one day that heroes fight like us

We won’t leave our land

We will pray in the Aqsa

26

27

28

29

Artwork by Amjad Al-Siyabi IG: @amjedalsiyabi

30

31

32

33

34 Al-Dal’ouna Dabka Team Zaffa, Dabka, Grand Entrance! Al-Dal’ouna Dabka Team @aldalouna_dabka Email: dalounadabka@gmail.com (973) 262-8511

35

36

Jamal Mustafa

Jamal Mustafa