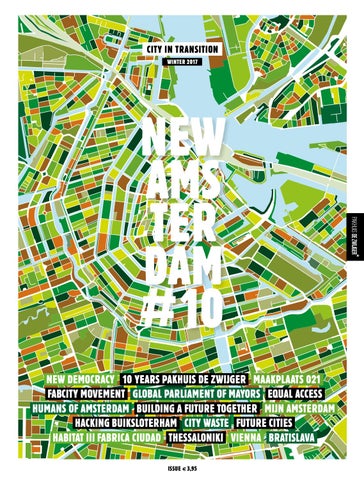

CITY IN TRANSITION WINTER 2017

NEW DEMOCRACY 10 YEARS PAKHUIS DE ZWIJGER MAAKPLAATS 021 FABCITY MOVEMENT GLOBAL PARLIAMENT OF MAYORS EQUAL ACCESS HUMANS OF AMSTERDAM BUILDING A FUTURE TOGETHER MIJN AMSTERDAM HACKING BUIKSLOTERHAM CITY WASTE FUTURE CITIES HABITAT III FABRICA CIUDAD THESSALONIKI VIENNA BRATISLAVA ISSUE E 3,95