Enjoy a dining experience that’s unique to your taste. Choose anything you like from our extensive regional menu at any time throughout your flight, from delicious canapés to a five-course meal, or indulge in dessert first.

EMIRATES FIRST

10 31

10 Streaming Wars — Has Jazz’s Tamasha cracked the code on monetizing content in Pakistan?

14 KSE at 100,000: What does it mean for Pakistan?

22 Hands On – Hats Off: How DTI’s Training Programs Drive Organizational Success

26 In an industry riddled with challenges, Treet Battery has proven its mettle. Can they seal the deal?

31 Thar Coal, once touted as the end to reliance on LNG, is capable of producing its own natural gas. What will it take?

Publishing Editor: Babar Nizami - Editor Multimedia: Umar Aziz Khan - Senior Editor: Abdullah Niazi

Editorial Consultant: Ahtasam Ahmad - Business Reporters: Taimoor Hassan | Shahab Omer

Zain Naeem | Saneela Jawad | Nisma Riaz | Mariam Umar | Shahnawaz Ali | Ghulam Abbass

Ahmad Ahmadani | Aziz Buneri - Sub-Editor: Saddam Hussain - Video Producer: Talha Farooqi Director Marketing : Mudassir Alam - Regional Heads of Marketing: Agha Anwer (Khi) Kamal Rizvi (Lhe) | Malik Israr (Isb) - Manager Subscriptions: Irfan Farooq

Pakistan’s #1 business magazine - your go-to source for business, economic and financial news. Contact us: profit@pakistantoday.com.pk

the

Tamasha, the favorite OTT platform of millions of Pakistanis has witnessed monumental growth over the past three years. But does it have all fronts covered?

By Hamza Aurangzeb

The days of passive television consumption are long gone. Viewers now command their entertainment destiny, summoning favorite shows with a mere tap on a smartphone or click of a remote. Streaming giants like Netflix, Amazon, HBO, and Disney have revolution-

ized how we consume content, transforming television from a scheduled experience to an on-demand universe.

Binge-watching has become more than a trend—it’s a cultural phenomenon. Viewers no longer wait for weekly episodes; entire seasons are devoured in marathon sessions, reflecting an insatiable appetite for storytelling that transcends traditional media boundaries.

For countries in South Asia, this digital

content revolution arrived fashionably late. Limited internet access and prohibitive subscription costs initially kept the region on the periphery of the global streaming landscape. But that was then.

Today, digital content consumption has evolved into a nuanced, immersive experience. Unlike fleeting digital interactions, Over-theTop (OTT) platforms now offer meticulously curated content that commands viewers’

undivided attention. The average OTT session now stretches far longer than traditional digital engagements, signaling a profound shift towards intentional, quality viewing.

This transformation has birthed a fascinating global content ecosystem in Pakistan. K-pop and K-dramas from South Korea sit alongside Japanese anime, while American psychological thrillers and Turkish historical narratives serve as a testament to the borderless nature of modern entertainment. Platforms like Netflix have become global cultural conduits, offering libraries that reflect this rich, diverse content landscape.

While Netflix dominated the Pakistani market since 2016, the post-COVID streaming landscape has become a battleground of emerging platforms. Amid numerous launches and quick exits, one player has emerged distinctly: Tamasha, Jazz’s OTT platform, which has carved a remarkable niche in merely three years.

But has Tamasha truly cracked the code of Pakistan’s streaming market? To understand its strategy and the broader competitive dynamics, Profit dives into the intricate world of streaming platforms.

The telecommunications sector in Pakistan remained an oversaturated market for an extended period characterized by intense competition and low margins due to the presence of numerous mobile network operators. The fierce competition in the industry depleted the overall ARPU of all telcos in Pakistan, while the high inflation and the Pakistani Rupee’s depreciation exacerbated the situation by dwarfing the numbers even further.

The introduction of mobile broadband completely changed the dynamics of the telecom industry and added to the wounds of the telcos as up until that point, the main mode of communication was phone calls and messaging services, which was the main source of revenue for them. However, as soon as telcos started providing high-speed data services at affordable rates, people began transitioning towards digital platforms like WhatsApp, which provided calling and messaging services for free. This meant that these telcos were providing data services to customers for using these platforms which were decimating their own major sources of revenue i.e. phone calls and messages.

This complication served as an impediment to the expansionary plans of Jazz, particularly in USD. Therefore, its parent company Veon developed the “Digital Operator 1440” strategy in 2021 which is now followed by Jazz and

all Veon-owned companies across various countries. The philosophy of this strategy is to capture the maximum attention of customers by offering a variety of digital services, where 1440 refers to the number of minutes in a day. As of September 2023, Veon serves around 103 million monthly active users across its digital services and platforms.

This new strategy enables the company to achieve multiple objectives, first, it allows the company to create a diverse range of business streams, secondly, it maximizes data consumption of its customers, and lastly, it authorizes the company to generate additional revenue from in-app purchases.

Hence, the company launched a variety of OTT services including Tamasha, a streaming platform which offers both video-on-demand and live television. It is available to customers of all the telecom operators in Pakistan and its content could be accessed by the users from anywhere, be it their home, car, or office.

Tamasha has emerged as the most popular OTT platform in Pakistan, where its remarkable success has caught many by surprise. It received the award for Best Online Streaming Platform at the Pakistan Digital Awards 2024 for the second consecutive time owing to its major contribution towards the evolution of digital entertainment in Pakistan.

The initial success of Netflix in Pakistan made it abundantly clear that Pakistan is transitioning from television to streaming to fulfill its entertainment needs. Several OTT platforms entered the market but lacked local content, which created a gap in the market. Jazz identified this gap quickly and launched its own

OTT platform by the name of Tamasha in 2021. Tamasha aims to offer local content on its OTT platform which aligns with the social norms, cultural values, and entertainment preferences of the masses.

Tamasha is inclined towards offering local content through mobile that was traditionally telecasted through television in order to make it accessible to a larger audience, however, its portfolio encompasses a wide range of content like popular Hollywood movies, classic international TV shows, flamboyant Bollywood movies, major sports tournaments, live local channels, and original local content.

Jazz developed the platform by leveraging its own in-house technical prowess, which resulted in an exemplary user experience. Furthermore, it employed its affordable data bundles and extensive network to provide sleek access to its users across both urban and rural regions, erasing the digital divide.

The business model of Tamasha differs a bit from the likes of Netflix, a popular international OTT platform. Netflix charges its users a subscription fee in order to provide an ad-free seamless experience, which allows them to binge-watch. Customers who opt for Its mobile package are charged Rs. 250 per month.

However, Tamasha has a dual revenue stream. It earns through subscriptions that range from Rs 10 a day with 2GB of streaming data to Rs 120 a month with 25GB of streaming data. Moreover, it generates revenue through advertisements by striking deals with brands and companies to showcase their ads during content streaming.

However, Tamasha is not the only local OTT platform in Pakistan but there are several other platforms that are operating in the country. Some of the other popular local platforms include Tapmad, a product of Tapmad Holdings Pte. Ltd., ARY ZAP operated by ARY

Group, Shoq, an OTT platform of Ufone, and Urduflix which was launched by Emax Media.

If we analyze the number of downloads for each of these platforms, we find that Tamasha (Rating: 4.37) leads the pack by a mile as it has been downloaded more than 45 million times, Tapmad (Rating: 2.28) grabs the second spot with 7 million downloads, ARY Zap (Rating: 3.48) holds the third place with 5.1 million downloads, while Shoq (Rating: 4.59) and Urduflix (Rating: 3.81) find themselves at the fourth and fifth place with 1.9 million and 1 million downloads, respectively.

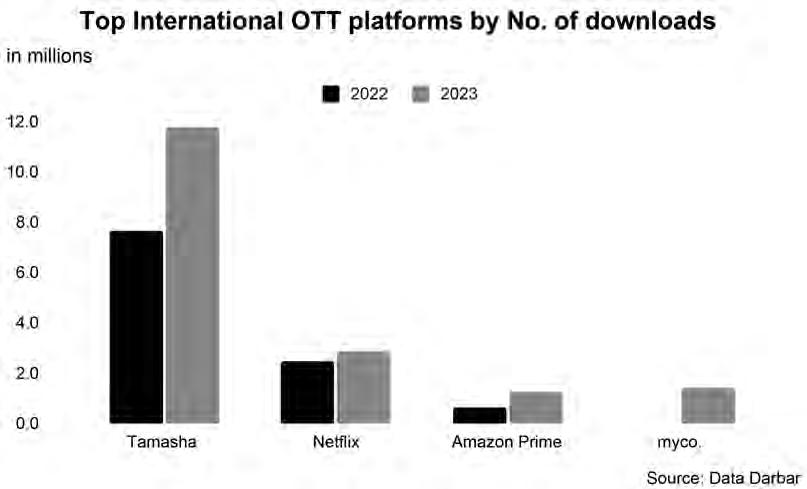

However, the story doesn’t end here as Tamasha has not only managed to steam past the local competition but has outperformed popular international OTT platforms like Netflix and Amazon Prime in terms of downloads for the past two years, consecutively. The Tamasha app had such a huge lead that the competition was nowhere to be seen, which validates its meteoric rise in the OTT space. According to Data Darbar, Tamasha recorded around 7.68 million downloads in 2022, which increased by 53.6% to 11.8 million downloads in 2023, Netflix was downloaded only 2.5 million times in 2022 and 2.9 million times in 2023, while Amazon Prime was downloaded 0.7 million times in 2022 and 1.3 million times in 2023, and myco. managed to gather 1.4 million downloads in 2023.

So what has made Tamasha so successful one would ask? The answer is one word: Cricket.

Pakistan is a cricket crazy nation, where individuals from all age groups and segments of society are obsessed with the sport. Although this has been the case since the beginning, one major transformation that has been observed is that the masses are increasingly transitioning towards digital platforms to watch the sport instead of traditional platforms like TV. This revolution is taking place due to the young demographic of Pakistan, where two-thirds of the population is under 30, and high mobile broadband penetration of about 53.2%.

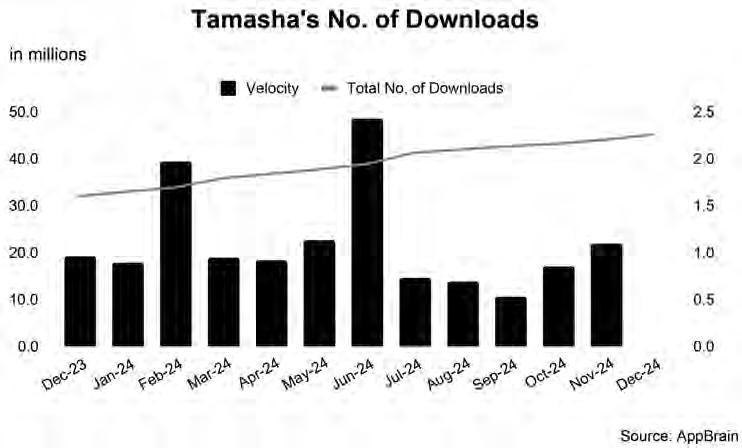

Well, Tamasha has a diverse range of content on its platform including 90 plus TV channels, however, its most popular content has proven to be live streaming of major cricketing tournaments. Tamasha has developed this innovative strategy to pull in the masses towards its platform by establishing partnerships with major sports channels and cricket boards in order to acquire licenses to broadcast cricket championships. Although Tamasha was already experiencing significant growth, this strategy has proven to be a game-changer. It has expedited the expansion of the platform across the country, its rapid growth is conspicuous in the reported numbers.

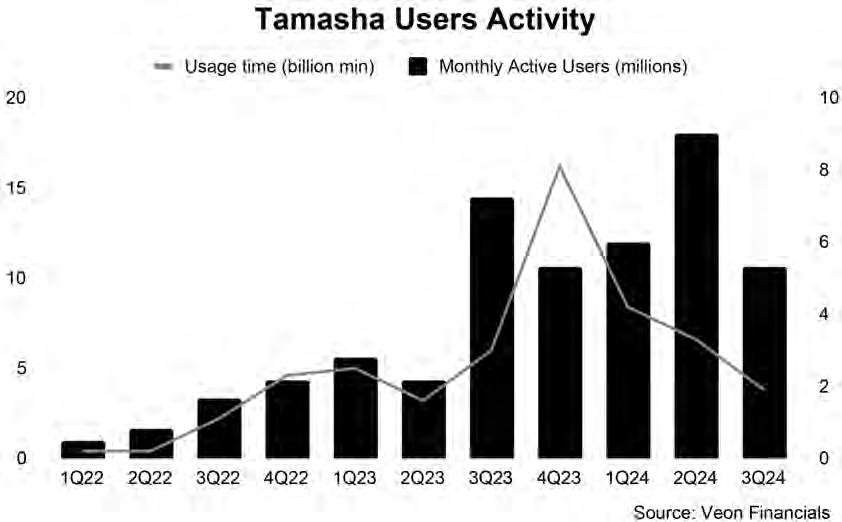

The number of monthly active users for the app stood at 4.3 million, whereas the total watch time hovered around 1.6 billion minutes during 2Q23 but as soon as the platform commenced broadcasting major cricket competitions like Asia Cup 2023, Cricket World Cup 2023, PSL 2024, and World T20 2024 its monthly active users increased to 18 million while its watchtime reached the level of 3.3 billion minutes during 2Q24. This meant that the users were glued to the app for four consecutive quarters.

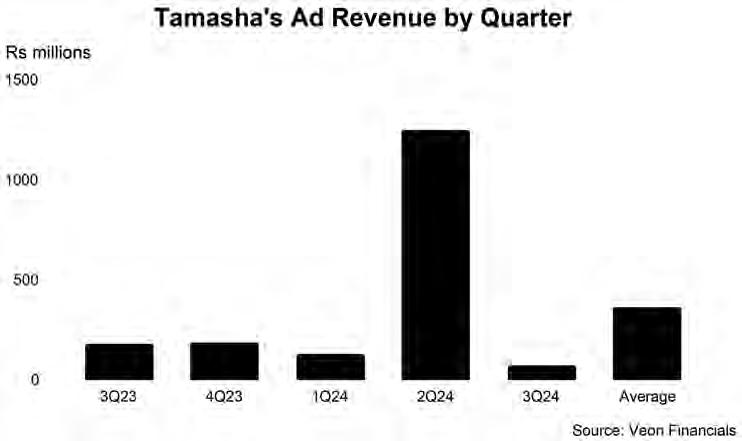

The live streaming of cricket tournaments allowed the platform to generate a revenue of Rs 1.75 billion ($6.3 million) over the course of four quarters from 3Q23 to 2Q24, where the bulk of the revenue, around Rs 1.25 billion ($4.5 million) 71.5% of the total was produced in 2Q24 due to the ongoing World T20 2024. Tamsha has expansive coverage across the country and a high interaction rate. During 2Q24, its users logged in for 293 million sessions, where 50.6%

of the users belonged to other networks and the average usage time per user per day hovered around 18 minutes.

This persuaded numerous leading brands and companies in Pakistan to collaborate with Tamasha and advertise their commercials through its platform as it provided a cost-effective solution for them to reach a wide and diverse audience. By the end of 2Q24, it had established partnerships with more than 50 international and domestic brands, which showcased that it had cemented its spot as the premier OTT platform for brand endorsements in the local market.

Tamasha has successfully implemented its live cricket streaming strategy, which has played a fundamental role in establishing it as the go-to platform for millions of Pakistanis. However, the platform is significantly dependennt on this single strategy, perhaps even over-reliant because as soon as the major cricketing tournaments conclude, the number of downloads and watchtime of the app falls dramatically.

This trend is evident in all major metrics of the app, let us analyze the numbers of 3Q24, where no major cricket tournament was broadcasted. In this quarter, Tamasha generated a meagre revenue of Rs 73 million only, which is 80% less than the average revenue of Rs 365 million in the past five quarters. Moreover, its monthly active users declined to 10.6 million, its total watchtime plummeted to 1.9 billion minutes, and the average usage time per user per day fell to 14 minutes.

The platform needs to be wary of the increasing competition in acquiring broadcasting rights for major cricket championships. There are other OTT platforms in the market as well

such as myco., Tapmad, Shoq, and ARY ZAP which are following a similar screening strategy. Although Tamasha has the rights for live streaming tournaments like Champions Trophy 2025, Men’s Test Championship, and all Women ICC events throughout 2025, it is very much possible that it might fail to outbid other OTT platforms in the future leading to a breakdown of its business model.

Moving on to the local content such as the dramas, movies, and entertainment shows acquired by it from domestic media houses and film productions. Although it gives the platform an edge over international OTT platforms, it does a minuscule job of distinguishing the platform from the rest of the local streaming avenues. On top of that, the latest local content is available on YouTube for free along with the websites and apps of media houses themselves like ARY, Geo, and HUM. According to estimates for the last 30 days, ARY earned about $1.21 million, Geo accumulated a revenue of $1.16 million and HUM

gathered a sum of $0.71 million from YouTube, which means an average revenue of $1.21 per 1000 views, a substantial revenue considering the Pakistani market.

The platform offers a diverse range of content but lacks depth, as your choices are restricted. It definitely has some entertaining international shows and movies which would help you pass a couple of hours but its library of international programs is limited in comparison to giants like Netflix and Amazon Prime. This is the case because it is expensive to buy foreign content. According to industry experts, foreign content can consume up to 40% of the revenue. Hence, the only feasible option for Tamasha at the moment to diversify its content is production of original content. It will allow the platform to offer fresh and exclusive content that adheres to the priorities of its massive user base, while captivating their attention span and persuading them to maximize their engagement. Moreover, it will enable the platform to regulate content in a more efficient manner and enhance revenue significantly by providing a different flavor. The platform has explored the endeavor of generating original content to some extent by producing dramas like ‘Family Bizniss’ and “Bashu”, however, the platform has a long way to go in this segment.

While Tamasha has established a promising presence in the Pakistani streaming market, the competitive landscape presents significant challenges. Despite maintaining a robust content pipeline for the immediate future, the platform cannot rest on its laurels. The cautionary tale of Hotstar in India—which experienced a dramatic subscriber exodus of 4.6 million in the third quarter of 2023 after losing crucial IPL digital rights—serves as a stark reminder that sustained success in the streaming industry hinges on continuous innovation, strategic content acquisition, and the ability to adapt rapidly to evolving market dynamics. n

At a time of political instability and a tentative economic recovery, the KSE-100 index has crossed a major milestone. What does the market’s rally mean for Pakistan?

By Farooq Tirmizi

The KSE-100 index – the benchmark index that seeks to measure total returns of a representative sample of stocks on the Pakistan Stock Exchange – has hit 100,000 for the first time. It is generally not a good idea to read too much into the day-to-day movements of the stock index, even when it reaches such momentous psychological levels, but one thing can be said with certainty: the optimists are right to believe in the upward trajectory of the Pakistani economy, and the Pakistani capital markets provide a strong mechanism for middle class Pakistanis to generate wealth for themselves and their families through the capital markets.

The above point is one this publication has made several times in the past, though perhaps in slightly less categorical terms. So what has changed? In a word: data.

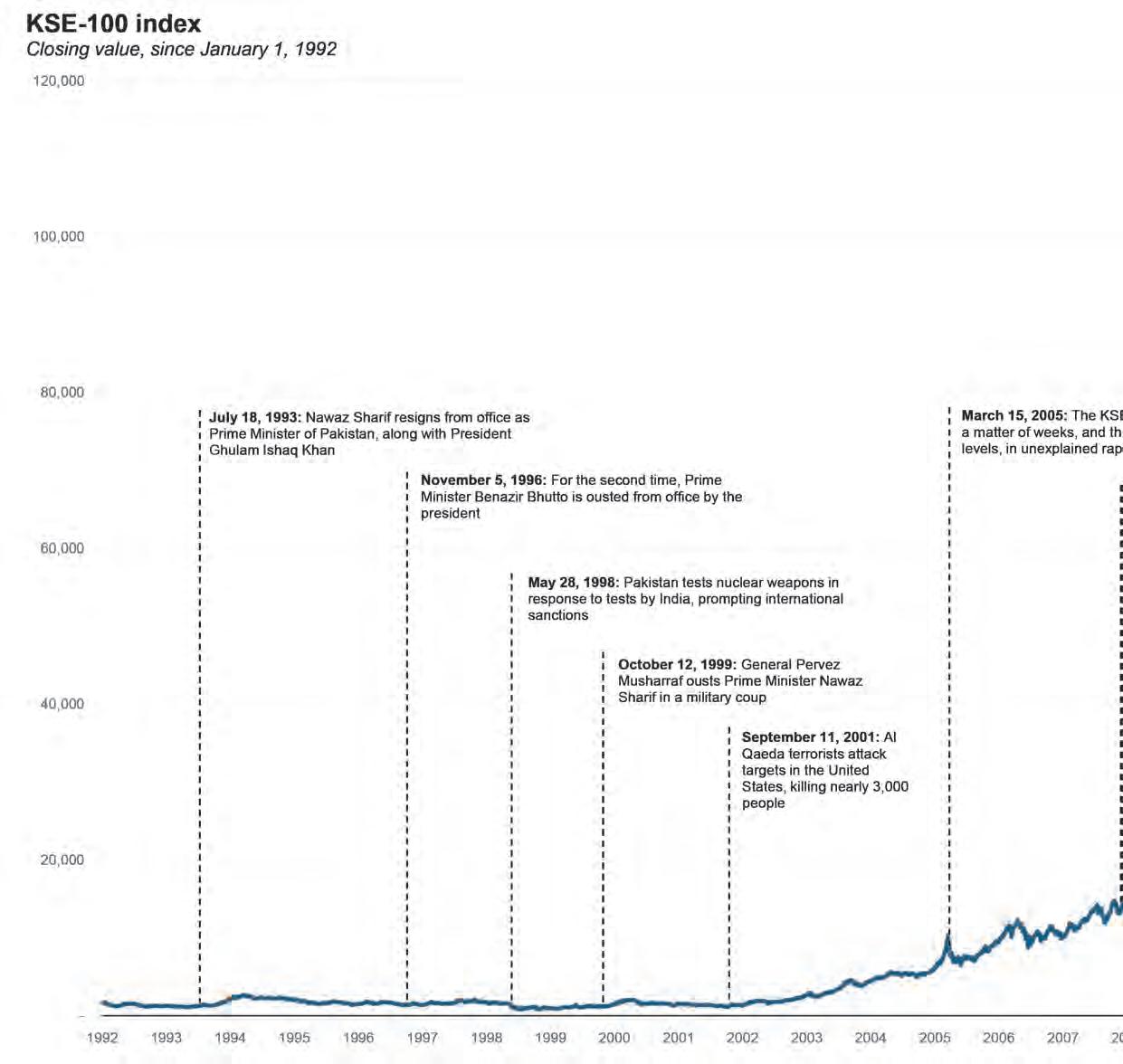

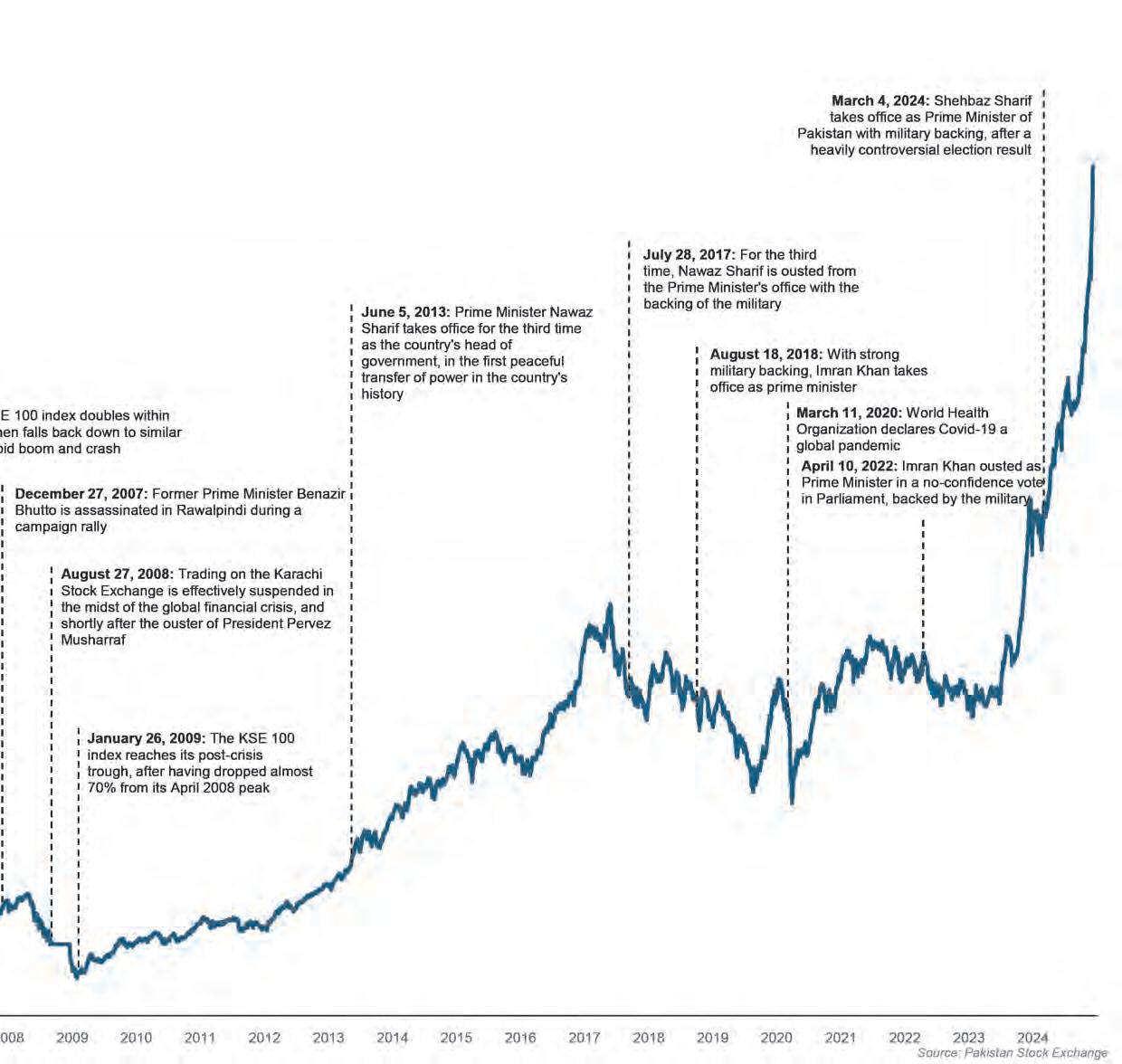

There is now 33 years of data – roughly a whole generation’s worth – that demonstrates the value of investing in Pakistani stocks. During those 33 years, the country has seen unstable democracy, military coups, war in Afghanistan, refugee crises, dozens of International Monetary Fund (IMF) bailouts, and several cycles of extreme economic upheaval. The market has had several hard crashes, and several euphoric rises.

Is the market volatile? Yes. But now we know how it reacts to just about anything this country can throw at it, and so fewer and fewer of the sceptics reasons for not investing in Pakistani stocks make sense with each passing year. In any given year, is there a very high likelihood that your investment in Pakistani stocks will lose money? Yes. Is there now a reasonable expectation that if you do not panic sell during the market’s crashes, the next bull run will more than make up for your losses? Also, yes.

In this article, we will do something a bit different. We will not just give you the cold mathematical facts about investing in Pakistani stocks (“if you had invested RsX at Y date, you would have had RsZ by now”). We will address the messy reality of it from the perspective of living, breathing, emotional human beings.

We will trace the history of the market from the genesis of the KSE-100 index in November 1991, examine how the market has reacted to 33 years of political and economic

change in Pakistan, and then look at what it would mean to have been an investor throughout that whole period, including the good, the bad, and the ugly.

We will then address what it means to be an investor in Pakistani stocks, and in this section, we will address the valid criticism that the universe of publicly listed companies is not representative of the sector breakdown of the broader economy, and that some of Pakistan’s most promising companies remain privately held.

Our conclusion: it is very hard to be an investor in Pakistani stocks, and there are many valid reasons to be a sceptic. But it is worth it to invest anyway.

A generation of Pakistan’s political economy, as told through the KSE-100 index

The Karachi Stock Exchange has existed since 1948, but it was not until November 1, 1991 that the exchange got its first stock index: the KSE-100 index, which was meant to mimic indices in other more mature markets and seek to quantify the total returns on the stock exchange. It is, briefly, the weighted average of stock price changes – and dividend payouts – of a representative sample of 100 stocks listed on what is now called the Pakistan Stock Exchange.

To make this history of Pakistan’s capital markets more real, let us view it through the lens of a hypothetical graduate of the Institute of Business Administration (IBA) Class of 1991.

This person graduates in June 1991 and starts working, earning, let us assume, the median IBA graduate salary at the time of around Rs8,000 per month. This is a young 22-yearold, so let us assume they live at home, and are able to save about a quarter of their salary: Rs2,000 per month.

One other assumption we will make is that this person is not able to maintain this high savings rate in the future as his expenses increase. They do, however, manage to increase the monthly savings number by at least inflation every year. Savings as a percentage of income goes down as his expenses increase, but at least the real value of each month’s saving does not decline.

Shortly after they start working, the KSE-100 index is launched in November 1991,

and let us assume this person is then prompted by that announcement to start investing their monthly savings in Pakistani stocks via the handful of equity mutual funds that existed at the time. For simplicity’s sake, let us assume these funds have returns that exactly track the KSE 100 index, net of fees. (In reality, the only private sector equity fund from that era that is still operational – the AKD Golden Arrow Fund – significantly outperforms the KSE 100 index.)

Now let’s look at what is happening in Pakistan at the time. It is 1991. The powerful military dictator Ziaul Haq was brazenly assassinated only three years ago, and nobody knows who did it. The first post-Zia elected government of Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto did not even last two years before being kicked out by President Ghulam Ishaq Khan, on charges of corruption and incompetence.

The new prime minister, Nawaz Sharif, is in favour of privatization, which seems like it will undo the damage of the 1970s-era nationalization drive. But corruption and incompetence do not seem to have abated much. Still, there is some optimism in the air, and so this person takes the leap and invests.

A little over a year-and-a-half later, for reasons that do not entirely appear clear at the time, the prime minister and president both resign in short order. This is still an era of extreme political censorship, so it is not at all clear from the newspapers as to what actually happened, except that the Army was probably involved in the ouster.

The political uncertainty means that nearly the whole previous year, from August 1992 to June 1993, the investment is in a loss. It is early days, though, so this investor soldiers on.

In October 1993, Benazir Bhutto is re-elected Prime Minister, and the market really starts to pick up momentum. By April 1994, this investor has some real returns. Since starting their saving journey in November 1991, they have saved Rs65,000 but the value of their portfolio is Rs119,000, or about 83% above the principal investment amount. One suspects this investor is starting to feel really good about their decision to invest.

But the second Bhutto term’s corruption starts to become apparent very quickly. The prime minister’s husband, Asif Ali Zardari, is being called “Mr 10%” and it is clear that the government is not actually good at governing. Inflation is rising, and the KSE-100 index – having risen to a level above 2,600 points –starts going down again.

By the time Benazir Bhutto is ousted for a second time in November 1996, the market has erased most of its gains. Sure, the index is still around 1,500 points, but this investor had been systematically investing even at the higher prices, meaning that their total portfolio value is down about 7% from their principal amount invested. It is also clear that political instability is just a fact of life in Pakistan.

In February 1997, elections are held and Nawaz Sharif comes back to power, and for a while there is hope again. By August 1997, the index is flirting with the 2,000 point mark, and our investor friend is sitting on a portfolio value about 24% above his principal amount invested.

Then India decides to test a nuclear weapon, and the world goes to hell.

By June 1998, our investor is down massively on their investment: they invested Rs220,000 in principal, and have a portfolio worth only Rs129,000 – a nearly 42% loss in just two weeks!

At this point, let us leap into the world of fiction and assume this investor decides not to give up hope and just sticks with his plan and keeps on investing. Almost nobody actually did that (famously, Arif Habib did, and that is why he is as rich as he is today, but you get the idea as to how rare it was).

The next year is a frozen hell in the market, and while there is a slow and painful recovery for much of 1999, when Nawaz is finally ousted by General Musharraf, our investor is still down about 15% of his principal investment amount, despite continually investing even at these lower prices.

The Musharraf era starts of promising and by April 2000, our investor is up 42% on their principal amount. By this time, his monthly investment amount is up to Rs4,000 per month, though at a salary of around Rs30,000 per month, this is around 13% of his income, about half the savings rate as when he first started.

Then comes 9/11, and for a few weeks, it looks like hope is gone again. By October 2001, our investor is down 22% on their principal amount, and stays down well into January 2002.

Consider what has just happened over the past 10 years to this investor. Of the 122 months between November 1991 and January 2002, this investor has been down relative to their principal investment for 58 months, or about five out of the 10 years that they have been investing. That is an absolutely miserable track record.

Life gets a bit better during the remainder of the Musharraf era, up to a point. There is that period of insanity in the first six months of 2005 when the market goes from 5,000 to 10,000 points, and then back down to 6,000 points all within weeks.

But by this point, our investor is well within a profitable range and never looks back. The Musharraf era feels stable, and the market’s upward trajectory feels like it is based on real economic growth.

This, of course, does not mean that the market does not throw uncomfortable gyrations. Far from it: the worst is yet to come. On April 18, 2008, the KSE-100 index reaches its Musharraf-era peak of 15,676 points, and then begins an unprecedented plunge that causes the brokerage firms that owned and controlled the exchange to panic and effectively shut down the market for almost five months from September 2008 through January 2009.

When the market finally re-opened, it continued its plunge until January 26, 2009, when the KSE-100 index hit 4,815 points, representing peak-to-trough plunge of 69.3% in just 9 months. It would take the market more than four and a half years – until October 2012 – when it would recover the levels it last saw in April 2008.

But from January 2009 through the end of May 2017, the market had a nearly relentless rise from that low of 4,815 points to the third

Nawaz term peak of 52,876 points, an 11x rise in about 8 years. This was a period when religious extremism was at its peak in Pakistan, with the war in Swat in 2009, the Salmaan Taseer assassination, nearly weekly bombings in all major cities in Pakistan, the APS Peshawar attack in 2014, and so much else besides.

But it looked like Pakistan’s politics was becoming more stable, with the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) and Pakistan Muslim League Nawaz (PML-N), the two parties that oversaw that chaotic 1990s decade, finally learning to play by an agreed set of rules, and the Pakistan Army largely staying out of the limelight.

Then came 2017, and a combination of Finance Minister Ishaq Dar’s unsustainable obsession with the rupee’s exchange rate staying at close to Rs100 to the US dollar, and the rise of Imran Khan – backed by the military – started a downward spiral again. By August 2019, a year into Imran Khan’s administration, the index had plunged to 28,764 points, when it was clear that – for all their tall claims of a “competent, uncorrupt team” – the Pakistan Tehrik-e-Insaf (PTI) had no game plan for governing Pakistan.

The market then largely kept gyrating between that level and around the 40,000-point market for the next four years, barely reacting to Imran Khan’s ouster from office, until it was clear than the military was going to be able to get its way and have a pliable political partner in office through the 2023 elections. Since then, the market has had a meteoric rise to now cross over 109,000 points on December 6, 2024.

By this time, our investor – who started off as a 22-year-old young professional – is now a senior 55-year-old. He probably makes north of Rs800,000

per month, and is investing about Rs38,000 per month (or less than 5% of his income) every month. His savings rate is one-fifth of what it was at the start of his career, because he may be earning a lot more money, but he also has a lot more financial responsibility.

He has invested a total of Rs40 lacs in principal contributions and has a portfolio that has a current value of Rs5.1 crore, and he still has about 10 years to go until he retires. But given the value of his portfolio, what this also means is that he can effectively choose to retire any time over the next 10 years when the market looks like it is doing well, cash out this investment and place it in safer investments (government bonds, or other fixed income investments), and spend the rest of his days with steady passive income.

Here is the part we want to highlight, though: remember the first 10 years of his investing career, when he was facing a loss of principal about half the time? That period of stagnant market returns accounts for fully 40% of his portfolio’s value. Meaning, if he had panicked early on, sold everything, and not entered the market until the boom of the Musharraf era, he would have had 40% less money. And if he waited until the first year of the Musharraf era boom was already over (most likely scenario for a panic seller), he would have had 60% less money, even if he had been a thoroughly well-disciplined investor after that!

How can this be? How does that period of low-returns contribute such an outsized amount of his total portfolio value? Simple: all else being equal, you want the first 10 years of your investing career to be a period when the market does not go up at all, or better still, keeps going down.

Why? For two reasons that play on top of each other:

1. The early years are when you have the least amount of money, so you want stocks to be cheaper so that you can buy more of them every month. If stocks are not going up,

that means you do not face rising prices every month, and if they are going down, you actually get more per month.

2. The shares you buy in the early years have the most time to compound, so by definition, they will always contribute an outsized amount of your total portfolio value.

The fact that Pakistan’s political economy was a complete basket case throughout the first decade of this person’s career was a good thing that made this investor literally twice as rich as he otherwise would have been. It is not smart to avoid investing during periods of political uncertainty. It is precisely the opposite.

Of course, there are two assumptions underpinning the assertion that this strategy would work. The first is that the assets being purchased are worth investing in, and the second being that prices eventually do rise. We will address both of these points next.

If you are a regular reader of this magazine, it is unlikely that you believe the standard Pakistani drawing room banter about “this country will never progress” or “who knows if Pakistan will even last in the future” nonsense. We would go one step further and argue that the Pakistani economy has some favourable fundamentals that are worth investing in, at least for those of us who live here.

Earlier this year, we ran a four-part series on the bull case for Pakistan’s economy, which we will briefly recap: Pakistan is the largest country in the world with an above-replacement fertility rate, and is poised to reap its demographic dividend over the next 30 years.

The government of Pakistan has not done nearly enough to solve problems like improving literacy and health outcomes, or providing macroeconomic stability, but the people of Pakistan are on their way to solving these problems without the government’s help. The

four ingredients needed for the country to be able to capitalize on the demographic dividend are coming into place. They are:

1. Electricity generation, which needs to be above 500 kilowatt-hours per person per year in order for the country to have enough electricity to begin the industrialisation process, which has been the case in Pakistan for two decades.

2. Stabilising fertility, which means having a fertility rate below 3.0 in order to have the right balance of dependents and working age adults in the population to work, save, and grow the economy; Pakistan will reach this point sometime in the early 2030s.

3. Sufficient literacy, specifically meaning adult literacy above 70% in order to have a workforce that can do basic skilled tasks in industrial settings, and educate their children to move even further up the value-chain; Pakistani urban areas have already reached this threshold.

4. Sufficient domestic savings, specifically a domestic banking sector large enough to result in relatively lower costs of capital, and absorb the government’s inefficiency by allowing it to finance its budget deficit without having to print money or borrow from abroad; Pakistan will reach this point sometime in the early 2030s when fertility rates hit the sweet spot.

The stock market provides ordinary investors the opportunity to capitalize on the opportunity from this economy, and has done so for decades now.

In the 1990s, while the PPP and PML-N were busy fighting it out, the government privatized two of the five major banks and allowed many more new private sector banks to come into existence. It publicly listed Pakistan Telecommunications Company (PTCL), and the new private sector power plants started being publicly listed, as did the newly privatized cement manufacturers powering the boom in urban construction.

In the 2000s, the government privatized more banks, publicly listed its energy company holdings, including then the largest company

in Pakistan, the Oil and Gas Development Company (OGDC). It liberalized the financial services sector, allowing more financial services companies to be publicly listed. Consumer lending powered a boom in automobile manufacturing, most of it done by publicly listed companies. And increasing urbanization continued to power growth in the cement industry.

The 2010s were admittedly a somewhat stagnating decade, but the economy is now liberalizing again. After decades of being strangled by price controls, the pharmaceutical industry is being allowed to set their own prices a bit more freely, boosting profitability in the sector and creating opportunities for newer players like BF Biosciences to be listed.

Increasing literacy and internet penetration is creating an ever-larger market for consumer electronics like smartphones and laptops to be manufactured inside Pakistan, and companies like Airlink (also publicly listed) are providing investors the opportunity to capitalize on that trend.

Do these publicly listed companies represent the full spectrum of opportunities coming up in the Pakistani economy? No. For example, none of the major e-commerce or fintech companies is publicly listed, and those represent a major opportunity for growth in the economy.

But those companies will eventually get big enough to seek a public listing, and when they do, there will be a larger, ever-growing population of investors to finance the next phase of those companies’ growth.

This is (probably) not a bubble

The next question that gets asked frequently is: since the market has gone up so much, are we in a bubble? Should I wait until the market comes down before investing?

Firstly, it is a fool’s errand to try to time the market. The best you can do is hope you get lucky, and a far better approach is just to have a systematic investment plan, where one sets aside a consistent amount of money every month to save.

On the issue of whether or not the market is a bubble, we would posit that while the run-up in stock prices has been rapid and a correction cannot be ruled out, the data seems to suggest that the sharp rise in Pakistani stock prices has less to do with a bubble and more to do with the fact that the market was artificially depressed for about seven years.

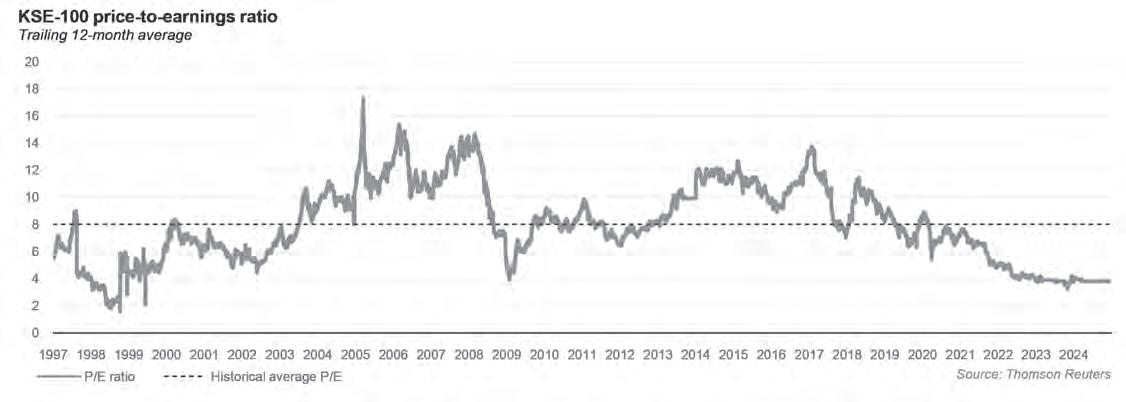

Indeed, one could argue that, relative to historical levels, Pakistani stocks are still undervalued, and even the historical levels of valuation for Pakistani stocks are far from being astronomical.

The most reliable measure of the relative valuation of stock prices is the price-to-earnings (P/E) ratio. Since 1997, the average P/E ratio of stocks that form part of the KSE-100 index has been around 8.0 times earnings. Despite the massive rise in stock prices over the past 18 months, stock prices are currently trading at about 4.1 times earnings, which implies that the market could double from its current level and still only just barely reach its fair value.

And strong bull runs can continue for a surprisingly long time in Pakistani stocks. Between October 2001 and October 2002, the KSE-100 index climbed over 100%, which must have felt like a massive post-9/11 bubble to everyone who was invested at the time. Over the next five and a half years, the market went up another 7 times from that “bubble” level. If, in October 2002, you had waited for the market to come down before investing again, you would have waited forever. It never came back down to those levels ever again. And you would probably had missed a major chunk of that 7x rally that came after the market

doubled.

All valuation indicators suggest that the Pakistani market’s recent boom is a shaking off of the artificially deflated prices of the past 7 years. There might be a correction, certainly, but if the market simply reverts to its historical mean valuation levels, and keeps growing earnings, there is a lot more room left in the rally despite the already stunning rise.

“Past performance is no guarantee of future results” is a phrase that most investment advisors are legally obligated to say, and since I am a Investment Advisor registered with the United States Securities and Exchange Commission, I will say this too.

The market can certainly take all sorts of bad turns, and if there is one thing that we have learned from experience, it is that Pakistani stocks are no place for short-term investing and best suited for investment horizons that are equal to or exceed 10 years.

But what the past 33 years also demonstrate is a resilience of the Pakistani markets and the ability of both businesses and investors to keep operating, even when it seems like the world is changing for the worse for Pakistanis. This is now at least enough of a track record for us as Pakistanis to know what the market’s reactions look like to various destabilizing events.

And while historical patterns rarely repeat precisely, they do rhyme, so while the past does not offer guarantees of future returns, it at least informs what we should set our expectations to be, and perhaps gives reason to keep hope alive.

None of what we have written will convince the cynics, and they will continue to sound smart to those who do not know better.

The optimists, however, particularly the well-disciplined ones, will continue to make money. n

For young Pakistanis from lower-income backgrounds, the journey to financial independence and stable employment can often seem daunting. Many lack access to higher education or the resources to pursue traditional career paths. DTI (Descon Technical Institute), a leader in vocational training in Pakistan, is committed to changing this by providing practical skills that enable young people to build meaningful careers in various technical fields. DTI’s mission is to uplift these communities by equipping the youth with the competencies needed to meet industry demands, empowering them to secure employment and break free from the cycle of poverty. Through accessible training and a robust curriculum, DTI is preparing students to not only enter the workforce but also to contribute meaningfully to Pakistan’s growing industries.

DTI offers a wide array of technical and vocational training courses aimed at equipping young Pakistanis with in-demand skills for sustainable livelihoods. Designed to meet industry standards, DTI’s curriculum encompasses following specialized trades: Welding: Covering both pipe and plate welding, DTI’s welding program ensures that students, many of whom come from under-resourced backgrounds, gain hands-on skills aligned with industry standards. These competencies open doors to roles in sectors where precision and expertise are highly valued.

Electrical: With courses in electrical installation, PLC programming, and maintenance, DTI prepares students for jobs in industries that have a strong demand for electrical expertise. By providing practical training, DTI provides students who cannot afford traditional costly education,alternate routes while still attaining skills that enhance employability.

QHSE (Quality, Health, Safety, and Environment): Offering globally recognized certifications such as NEBOSH-UK and IOSH-MS, DTI’s QHSE program enables students from varied backgrounds to gain credentials respected worldwide, making them valuable assets for organizations with rigorous safety standards.

Automation: In the era of digital transformation, DTI offers training in automation systems, including programming and control systems. These courses provide students with industry-relevant skills, making them competitive candidates for tech-forward industries without the prohibitive costs of formal higher education.

DTI’s fabrication courses focus on metalworking, equipping students with hands-on skills for the construction and manufacturing sectors. This training prepares them to excel in local projects or establish small-scale businesses in their communities.

DTI’s carpentry courses provide practical expertise in woodworking, enabling students to take on roles in construction or launch small businesses. The skills gained empower them to contribute meaningfully to their communities.

DTI’s civil training programs cover essential areas like quality surveying, preparing students for critical roles in Pakistan’s infrastructure development. With a focus on real-world applications, these courses empower graduates to secure stable careers and contribute to regional growth and development.

DTI’s millwright training focuses on machinery maintenance, equipping students with the technical expertise needed in high-demand industries. This training opens pathways to stable employment, enabling graduates to support their families and drive economic progress in their communities.

Each of these programs is designed not just to educate but to build competence in real-world applications, an approach that has earned DTI over 35,000 graduates across Pakistan. DTI’s offerings have grown to include more than 60 courses, with both in-person and virtual options, under the guidance of over 50 experienced instructors across 20 dedicated workshops.

DTI’s programs serve as a powerful engine for socioeconomic mobility. By empowering individuals with marketable skills, DTI enables graduates to secure stable employment and improve the quality of life for themselves and their families. This economic uplift extends to local communities, as DTI-trained professionals contribute to Pakistan’s economic landscape and drive regional development.

Through a commitment to providing

skills for livelihood, DTI’s training aligns with Pakistan’s broader goals of poverty alleviation and youth empowerment, making a meaningful difference in the lives of individuals and communities alike.

Acore component of DTI’s success lies in its robust partnerships with industry leaders and employers who recognize the value of a skilled workforce. By collaborating with these organizations, DTI tailors training programs to meet specific industry demands, thereby ensuring that graduates possess the competencies that employers seek. Employers benefit from the partnership as they gain access to a pool of skilled professionals who can meet their operational needs and contribute to higher productivity and safety standards. Many employers praise DTI’s graduates for their reliability and readiness, affirming DTI’s role as a trusted provider of skilled labor.

Agrowing number of DTI alumni are finding opportunities abroad, including on Descon’s international projects. These individuals not only achieve financial independence but also serve as ambassadors of Pakistan’s skilled workforce, earning foreign exchange that strengthens the national economy. This contribution underscores the global relevance of DTI’s training programs, which empower individuals to compete and excel in international markets.

Skilled workers are the backbone of many industries, from construction and manufacturing to technology and health and safety. Through their expertise, resilience, and work ethic, they drive industrial growth and infrastructure development while ensuring the

smooth functioning of operations. Recognizing the dignity and respect these workers deserve, DTI celebrates their invaluable contributions through its “Hands On – Hats Off” campaign—uplifting workers while honoring their indispensable role in society.

DTI is committed to continuous improvement and innovation in vocational training. The institute tackles the unique challenges vocational institutions face in Pakistan, such as limited access to modern equipment and evolving industry standards. By embracing technological advancements and refining its curriculum, DTI stays ahead of these challenges, equipping students with skills that remain relevant in a rapidly changing job market.

In addition, DTI is the first accredited NEBOSH Learning Partner in Pakistan to achieve Gold status, a testament to the institute’s commitment to high-quality education in health and safety. This recognition underscores DTI’s focus on excellence, which translates to well-prepared graduates who make significant contributions to their fields.

As the demand for skilled labor in Pakistan continues to grow, DTI’s vision remains steadfast. The institute is actively working to expand its reach to new industries and enhance its programs to adapt to the shifting landscape of the workforce. DTI aims to broaden its curriculum, increase its capacity for virtual and on-campus learning, and develop partnerships across a wider range of industries. Through these efforts, DTI not only strengthens the pipeline of skilled workers in Pakistan but also builds a foundation for sustained organizational success. Employers across sectors can look to DTI-trained graduates as assets who bring valuable skills, resilience, and a strong work ethic to their roles. n

The battery sector is recovering and Treet has emerged as a strong contender in the industry. Now, it may be time to look for fresh capital, and an IPO is the way to go

By Zain Naeem

When the Treet Corporation launched its battery manufacturing business in 2018, it was not exactly the smoothest entry into a new industry.

Treet Battery hit the market at a time when the battery industry was just about to hit a slump. By the time Treet began to come out of its initial birthing pains, the industry was facing some steep challenges. Load-shedding was at an all time low, meaning people did not need to buy batteries for their UPS as regularly. The auto-industry was experiencing plummeting demand and car companies were regularly halting assembly. And on top of demand falling, there was an increase in lead prices and a devaluation of the rupee.

It was a disaster to put it mildly. Battery manufacturers that had been in the game for years found themselves floundering. In fact, the 2018-21 period marked the worst period for battery manufacturing in Pakistan. And here was a new entrant just a couple of years into its existence suddenly thrown into the deep-end.

Which is why it might come as a surprise

to money that Treet Battery has come out the other end in pretty good shape. Not only has the company managed to become profitable, it has managed to increase its market share by taking away from bigger and older manufacturers like Exide and Atlas. In 2024, they earned a revenue of Rs 8.4 billion, giving them control of just under 12% of the overall market in only seven years of operations.

But there is a problem. Treet needs money. While their revenues have been increasing at an impressive rate during a difficult period for the industry and the economy, their debt costs are weighing them down. The answer to this problem is clear. Treet needs to raise more money, and perhaps the best option to do that is through an Initial Public Offering (IPO). Before we get to that, however, we must understand how Treet found itself struggling with this debt in the first place.

When you really think about it, it is astounding Treet has managed to carve a healthy position out for itself in the battery manufacturing sector.

Treet Battery began operations in 2018 when its battery manufacturing plant was

established. This plant was established under the First Treet Manufacturing Modaraba. For those unfamiliar, a Modaraba is an Islamic financial instrument that sort of works like a holding company. This is essentially a financial contract where the profit and losses made by the manufacturing company is divided between the investors. It can be considered an investment vehicle which invests on behalf of the investor in order to yield a return. Sort of like a holding company which runs different divisions under it.

Now, the Treet Modaraba already had the corporation’s soap manufacturing and corrugated box business under it. The battery division was a new entry into it. This will become important later.

The plant for battery manufacturing was established in February of 2018 with the help of Korean brand Daewoo which supplied the technical expertise to the workforce and trained them accordingly. The company prided itself on manufacturing maintenance free batteries which did not require periodic maintenance by the customers as its unique selling proposition.

In the initial years, the company saw losses as it was carrying out extensive training which was weighing down its performance. The bulk of the material required for the manufacturing had to be imported, and the prices of these inputs were increasing, further compounding the issues. But this was not a Treet specific problem. The inputs were equally expensive for all of the players, and the whole sector suffered some of its worst years in their history from 2018 to 2021.

Perhaps nothing is more telling of the challenges Treet faced as a new entrant as the drubbing the older players were taking. Pakistan’s battery manufacturing industry is primarily dominated by a few large players. These companies have been established for decades and have market penetration which they have built over time. Exide Battery was set up in 1953 and is considered one of the pioneers. Atlas Battery was set up in 1966 by the

Atlas Group. It signed a technical collaboration with Japan Storage Battery Limited in 1969 to produce Japanese quality batteries in Pakistan. The production started in 1969 under the brand name of AGS in which A stands for Atlas while GS for Genzo Shimadzu who was the founder of Japan Storage Battery.

Both these companies are involved in the manufacturing of lead acid batteries which are used for automotive and power backup solutions. Their latest accounts show that Atlas earned topline revenues of Rs 41 billion while Exide raked in Rs 26 billion in terms of its sales. Other than these two, the rest of the industry is made up of smaller players like Osaka, Phoenix, Millat and Bridge Power which have a small portion of the market distributed among them.

The battery industry was hit by a double whammy of sorts in 2018. On one hand, demand was down as new power generation plants started to come online leading to a decrease in demand for UPS inverters. On the supply side, the price of lead saw an increase which led to costs rising as well. Raw material makes up more than 85% of the cost of manufacturing from which a huge chunk is attributable to lead. As most of the lead is imported, the cost of lead is based on international price of lead and the dollar value.

The industry had already been hit by record high prices in October of 2007 as the price was trading at around $3,683 per ton, however, due to lower competition, companies were mostly able to pass the cost on to their customers which meant their margins were not impacted. This could not be done later when, from November of 2015 to January of 2018, the price increased by 59% from $1,647 per ton to $2,620 per ton.

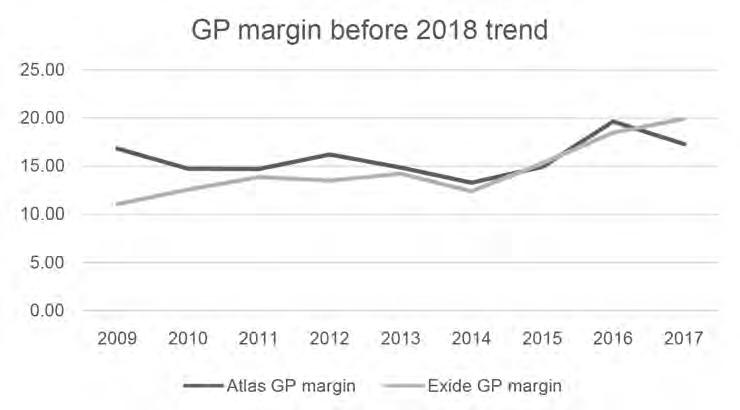

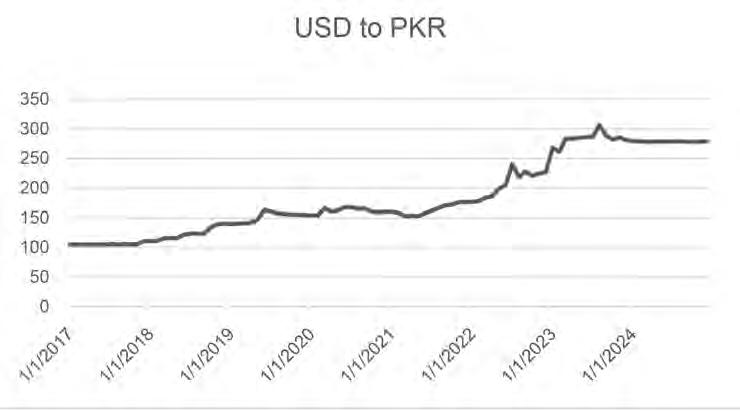

The price had finally fallen back to Rs 1,600 by May of 2020, however, from 2018 to 2020, the rupee had depreciated against the dollar from Rs 100 per $ to Rs 160 per $. The impact of these two economic variables working against the industry was disastrous. From 2009 to 2018,

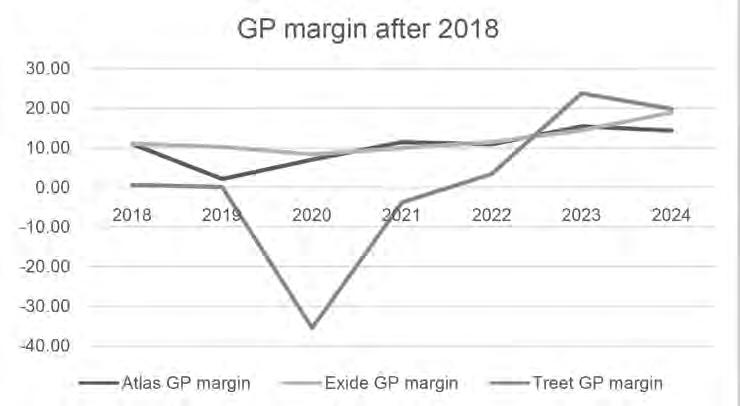

Exide battery was able to earn an average gross profit margin of 14.6% with nearly 20% margin seen in 2017. Even before 2009, the industry had seen depressed margins caused by the lead prices seen in 2007 which lowered the margins. Similarly, Atlas battery also saw average gross margin of 15.8% from 2009 to 2017 hitting a high of 19.6% in 2016.

Since 2018, Exide saw its average gross margin fall to 10.2% caused by the fall in demand and increase in its costs till 2022 with a low of 8.3% in 2020. From 2018 onwards, the margins fell to an average margin of 8.5% for Atlas Battery from 2018 to 2022 hitting a low of 2% in 2019.

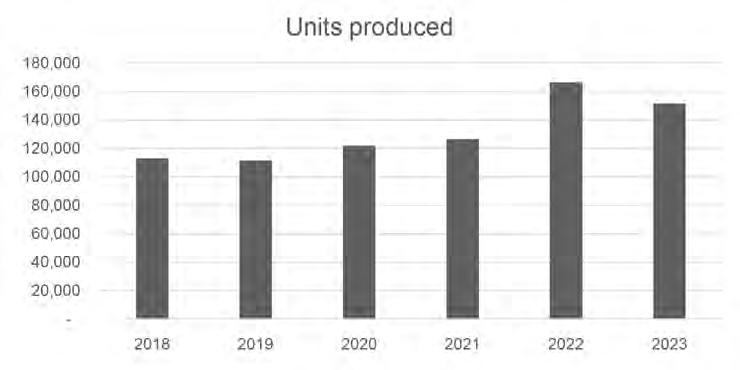

The overall industry has seen a bit of a recovery in the past couple of years. At the end of financial year 2023, the overall sector earned Rs 172 billion in revenues, compared to Rs 104 billion at the end of 2022. Even though the revenues increased, the number of units sold actually decreased from 152,000 units down from 166,000 units a year ago. The decrease in sales was countered with an increase in price which led to the increase in turnover. The trend in the industry has been on the mend in recent years as the industry saw production of 113,000 units in 2018. 2018 saw the start of a period where

the sector was hit by low demand fluctuating between 111,000 in 2019 to 127,000 in 2021. 2022 was the first year where production passed the 150,000 threshold in five years.

The reason the trend was broken in 2022 and 2023 was due to the increase in solarization that has taken place all over the country. In the past two years, there has been a stampede in the country to use solar energy which has invigorated some of the demand being seen.

Naturally, Treet was in as much of a fix as its competitors. On account of them having just entered the market, it was worse if anything. The initial years of production saw revenues of Rs 32 crores in 2018 which increased to Rs 5 billion by the end of 2022. Due to high cost of manufacturing, the company suffered losses of Rs 28 crores in 2018 while showing a net profit in 2022 of Rs 33 crores. This was no small achievement by any measure.

In order to comprehend the magnitude of this feat, it has to be considered that the company was entering a market which was dominated by two major companies. In an oligopolistic industry, the company had to face an uphill battle in order to generate demand. In addition to the Herculean task in front of it, the company also had to deal with falling demand and rising cost while being a new entrant in the market.

In the face of such towering challenges, it seems like the company has come on the other side with some pride left intact. At the end of 2024, the company has shown revenues of Rs 8.7 billion which are respectable for a company which had only 7 years under its belt.

In terms of market share as well, Atlas was able to earn revenues of Rs 41 billion in 2024 while Exide made Rs 25 billion in sales.

In the same period, sales of Treet clocked in at around Rs 9 billion. A simple back of the envelope calculation shows that in 2019, the three companies collectively made sales of Rs 24 billion out of which Treet made up 7.42%

of the share. In 2024, this ratio has increased to 11.5% which shows that the company is taking away market share from the two of its biggest competitors.

Another sign which shows that the company is able to outpace its competitors is the fact that in 2023, the company earned a gross profit margin of 23.8% in comparison to Atlas which had a margin of 15.4% and Exide which earned a margin of 14.4%. In 2024, the situation stabilized as Treet was able to show margins of 19.8% which was matched by Exide at 18.9% and beat Atlas which was at 14.3%. It seems that the company had a potential to grow and with the rebound in the auto sector and solarization, things were looking up. Except for a regulation that got in the way.

Since its inception, Treet has been under the control of Treet group. This meant that the company was propped up and supported by the management in the early days. Treet Corporation and the Treet Modarba were investing and lending the battery manufacturing the necessary financing it needed to establish itself. After the close of 2023, it was seen that the company was ready to spread its wings and fly by itself. According to the laws governing the corporate sector, the division first needs to be demerged from the modaraba and then the respective assets and liabilities are transferred to the new company.

The rationale behind this move is that investors have invested in the modaraba considering that they are investing in the companies that are in its portfolio. Once a division is being spun off, the legal requirement is to first carve out the assets and liabilities and transfer them accordingly. The current investors are given a share in the new entity that they now own in addition to their shares in the modaraba. Due

to this regulation, First Treet had to divide up the assets and liabilities and give out new shares in Treet battery where the assets and liabilities would be transferred as well.

Once the battery division started to show signs of profitability, it was demerged from the modarba and bifurcated as an entity by itself. As the company was being demerged, the assets and liabilities were separated and a new company was created. In addition to that, the shareholding of the new company was based on the shareholding in the modarba which meant that Treet Corporation and Treet Holdings ended up owning 99% of Treet battery.

The process for the demerger has to be sanctioned by the Lahore High Court which it carried out in effect from April of 2023. By June, the new shares had been credited into the accounts of the shareholders. The next step that was carried out was to list the shares of Treet Battery on the stock exchange which was completed by December 2023.

As the demerger was finalized, the issue at the heart of the company started to take shape. Treet battery had a large amount of debt that it had taken from Treet Corporation, Treet Holdings and Treet Modaraba. Before the demerger

took place, the company had assets worth Rs 9.3 billion while its liabilities were Rs 8 billion. Even though share capital of Rs 8.8 was issued by Treet battery, the assets and liabilities would not reconcile. In order to allow this to happen, a demerger deficit was created valued at Rs 8.2 billion. This was done to dampen the issued share capital of Rs 8.8 billion. In essence, what happened here was that equity was only worth Rs 1.3 billion while liabilities were Rs 8 billion. These two sources were used to fund the assets of Rs 9.3 billion.

The company that had been carved out was loaded with debt as short term borrowings were Rs 6.8 billion in 2023. By 2024, the short term borrowings had increased to Rs 7.7 billion. With no new source of funds, there was little that could be done to pay back much of this debt and was a ball and chain hanging around the ankle.

The effect of this borrowing was that even though it earned gross margins of 20% in 2024, the company saw a finance cost of Rs 1.2 billion in 2024 which made up around 14.5% of its revenues and was 73% of its gross profit. The high finance cost led its net margin actually becoming -3.27%. In comparison to this, Atlas saw net margin of 3.24% while Exide saw net margin of 4.89%.

Treet battery stands out among its competitors as it was the only company to register a loss in 2024. The fact that the company is not able to translate its gross margins into profits is the major reason why the company is still making losses. Around 60% of the assets of the company are being funded by short term borrowings which are leading to higher finance costs.

If the borrowings are broken down, it can be seen that islamic mode of financing is making up Rs 2.2 billion of these loans while Rs 5.5 billion are made by lending carried out by Treet group. The interest generated from these loans is worth Rs 56 crores to the financial institutions while Rs 65 crores are payable to Treet Corporation. The terms negotiated with Treet

are to pay weighted average cost of capital of the parent company. On the face of it, it can be seen that the rate being paid to the parent comes to around 11.8% while for the financial institutions it is more than double. This is one thing that Treet can be commended for is that it is providing a loan at much cheaper rates compared to the market. However, a question can still be raised in terms of what the company can do in order to stop this hemorrhage of profits.

Once the demerger and listing of the company had been carried out, Treet as the parent company could have considered going for an IPO which could have raised necessary funds. When an IPO takes place, the major shareholder goes to the investing public and offers a share in the company against investment. The investor gets to own a piece of the company in terms of its assets and profits while the company gets access to additional funds that they can use to either pay down its debt or use it in working capital needs. The sacrifice that is made by the majority shareholder is that his ownership is decreased in return for the funds that are raised.

If the impact on the balance sheet is considered, the company increases its capital while also giving a boost to its assets as new money is injected. These funds reduce the proportion of debt and can help alleviate some of the funding gaps that are present. Compared to debt, there is also a relaxed obligation in terms of paying back the investors which increases the future profitability as well. Considering that the company was performing well by the end of 2023, the investors could even have been given the shares at a premium which would have further strengthened its equity position.

This is where Treet is stuck. Due to low equity, the company needs to be funded through liabilities which are helping it meet its working capital needs. The best solution for this problem now would be to inject fresh capital into the company which can decrease the need for the debt that it has taken on. In this case, if the right issue is announced, most of the rights would have to be subscribed by the parent company itself which will need additional funds in order to do so. In reality, the opposite is being done.

From the time the company was listed, Treet Corporation has steadily liquidated its equity investment as it has seen its shareholding go from 99% to around 85% by now. This has depressed the price of the share in the market as well which touched highs of Rs 55 and beyond at one point but are languishing at Rs 18 right now.

The high finance cost that the battery manufacturer is facing can also be looked into. The company has given a short term loan to its subsidiary which charges a higher rate of interest. A long term loan can be given or some of the debt converted into equity in order to relieve some of the pressure. Again, the issue with that is that any additional equity given will be subsequently liquidated over time as well. Treet group would look to sell this portion of shares once they are given to them. Section 199 of the Companies Act 2017 also restricts the parent in giving a loan to a subsidiary which is too laxed or undercuts the market rate being asked for. A restructuring of the loan with the parent company can also be negotiated which is agreeable to the authorities.

In its own defence, Syed Sheharyar Ali, Chief Executive Officer at Treet battery stated that “In 2022, when the demerger was being

executed, it was the worst year for IPOs in a decade. 2022 only saw 3 IPOs in Pakistan all year, which raised approx Rs 1.2 billion combined. Yes, had the investment climate been different and had Pakistan not been going through a once-in-a-generation reserves crisis, made worse by a global commodity super cycle driving high inflation and record interest rates, we may have considered a share issue also, but the macro economic conditions at the time were extremely non-conducive.”

He states that the climate is better now with the KSE 100 index hitting new highs and investors gaining an appetite for investing in the bullish market.

This brings the argument back to the fact that an IPO was and still is one of the best solutions that can help the company grow further. Raising funds through an IPO can still help the battery manufacturer to shed some weight in terms of its debt while the group could have decreased their shareholding by selling it to the public. The initial step to demerge the company was mandated by law and required considerable time and resources in order to be carried out. The next step that the company should consider is to look into an offer which will help reduce some of its burden of debt while allowing it to show the profitability it is actually earning.

Considering the potential that the battery division has, there is a likelihood that the coming years can see higher demand in terms of better auto sales and solarisation drive in the country. It looks quite possible that the battery company is poised to take advantage of this opportunity and keeps chipping away at the market share of its competitors. It can still be expected that the demand increase in the future can still prove to be beneficial for Treet Battery as it looks to capitalize on the opportunity presented to it. The only caveat that has to be placed here is that the recovery can be faster and better if an alternative source of funds is looked into. n

once touted as the end to reliance on LNG, is capable of producing its own natural gas. What will it take?

When the first Thar Plant went live in 2019, it was supposed to reduce Pakistan’s reliance on imported gas. What does it mean if Thar’s Lignite can be gassified?

By Abdullah Niazi

On a hot April afternoon in 2019, Pakistan fired up its first ever power plant fueled by domestic coal. The shiny new plant, run by the Sindh Engro Coal Mining Company, was the sort of project bureaucrats, politicians, and development sector flunkies dream about and doodle the name of in their secret diaries.

For starters, it was the first to exploit the 175 billion tonnes of lignite that was spread across the 900 km2 coal fields in Tharparkar, which is possibly the second largest coal reserve in the world.

Check.

The project was being run through a public-private partnership between the Sindh Government and Engro Corporation, which is by far one of the most responsible organisations in corporate Pakistan.

Double check.

And the real kicker? Engro’s Thar Project came under the China Pakistan Economic Corridor with $50 billion of proposed investment in infrastructure projects. At the time this was one of the most talked about projects in terms of how China’s Belt and Road Initiative was impacting the global energy landscape.

Triple check.

But the timing, dear reader, was awfully ironic.

The Thar Coal fields had first been discovered in 1991 through a joint mission (we used that term very liberally) of the Pakistan Geological Survey and the United States Agency for International Development. With an estimated 175 billion tonnes of lignite, the Thar Coal Fields have the capacity to produce 100,000 MW of electricity for the next 200 years.

To put that into perspective, as of now the largest coal reserves in the world exist in the USA with just under 250 billion tonnes of recoverable coal.

The opportunity to exploit the coal fields was massive. The world was becoming wiser to the dangers of fossil fuels by the 1990s, but energy consumption still operated like the Wild West. But developing Thar Coal would take time, money, and a lot of technical assistance. And in the time between 1991 and 2019, Pakistan’s energy mix became a mess. Up until the 1990s, the largest source of electricity in Pakistan was hydel. But as demand for power grew and the desire to make new dams evaporated, the government increasingly began relying on imports.

In the late 1980s and throughout the 1990s, these imports came in the form of furnace oil used by Independent Power Produc-

ers (IPPs). From 2013 onwards, Pakistan was relying on importing coal for the coal plants set up by the third Nawaz Administration in Punjab, as well as allowing the private sector to import LNG.

Of course there was a problem with this. Imported sources of fuel tend to get expensive, especially when you do not have a strong export oriented economy. Energy prices in Pakistan were dependent on the whims and stability of the international market and the global order. So much so that by the time Engro’s plant went live in 2019, it was S&P Global reported on it with the headline “Pakistan’s Thar wager pits coal against LNG in its power mix.”

Thar Coal was supposed to be the answer to Pakistan’s reliance on LNG and other imported sources of fuel. At least to some extent. While it was not clean fuel, it was cheap, domestic, and readily available. The idea was that you would set up more plants close to Thar and figure out how to transport coal to other regions. However, as time has proven, transporting Thar Coal and setting up power plants in the Thar region is not the easiest task in the world. And for many years now, one fantasy has persisted somewhere in the collective hive-mind of our policymakers: turning Thar Coal into gas that can feed our thermal power plants and replace the crippling need for LNG.

Now, a recent study has indicated this can be done in an economically feasible way. However, it is not the first time the government has tried to cash in on the concept of turning Thar’s Lignite into gas. And it did not go very well the first time around.

It is a simple problem. Pakistan relies heavily on imported fuel sources such as reliquified natural gas (RLNG) to produce electricity. Whenever there is an international crisis, such as the Russia-Ukraine war, Pakistan’s energy sector is rocked by the ripple effect. There is a simple solution. Cheaper fuel — something like coal perhaps. And the source is right there too. Spread over more than 9000 km2, the Thar coal fields are one of the largest deposits of lignite coal in the world — with an estimated 175 billion tonnes of coal that according to some could solve Pakistan’s energy woes for, not decades, but centuries to come.

Currently, Pakistan produces around 2600 MW of electricity through Thar Coal. Just over five years ago, this figure was zero. The total reserves from Thar Coal are more than the combined oil reserves of Saudi Arabia and Iran. The reserves are around 68 times higher than Pakistan’s total gas reserves. Com-

pared to this potential the current utilisation of Thar Coal in the total power generation mix is around 10% which means that there is huge opportunity to expand in this sphere.

But as of now, imported fuel continues to be a big force in Pakistan’s electricity mix. What matters is that we are currently in a situation where we are dependent on RLNG. When RLNG was introduced into Pakistan’s energy mix, it was relatively cheaper and also environmentally friendlier than coal. Although long-term agreements with Qatar still provide gas at a relatively affordable rate, the spot market is a blood bath. Pakistan has been turning more and more to the spot market to address the growing local demand for gas.

The average cost of gas is rising at a very rapid pace due to the Ukraine war and subsequent global supply chain disruption. It is an issue Profit has covered in the past. During the Nawaz administration, the government decided to increase the generation capacity cheaply at the risk of it getting expensive later, which it has now. By 2022, the increased reliance on both imported coal and LNG, Pakistan was generating just over 52% of its electricity from purely domestic sources. That was down from 84% in 2005, and 71% as recently as 2012. This made Pakistan’s market more vulnerable to the whims of the international market. This has only gotten worse. According to data from NEPRA, thermal power plants running on imported fuels accounted for roughly 62% of Pakistan’s generation capacity in fiscal year 2022-23, with fuel costs alone representing an overwhelming 83% of the total generation expense. This heavy reliance on imports leaves the nation’s energy security at the mercy of global markets and exchange rates, an increasingly untenable position as the Pakistani rupee continues to slide against the U.S. dollar. Efforts to mitigate these costs, such as allowing coal imports from Afghanistan, have been undercut by the dollar-based payment system, negating any potential savings.

However, when it comes to the use of Thar Coal, there are some possibilities. The proportion of imported coal in the generation mix declined in FY 2022-23 as compared to FY 2021-22, owing to the introduction of more plants utilizing locally sourced coal, including ThalNova Power Thar (Pvt.) Limited, Thar Energy Limited, and Thar Coal Block-I Power Generation Company (Pvt.) Limited, facilitated by Shanghai Electric. In the case of recently commissioned Thar Coal power plants, the availability of the transmission line was delayed.

At the same time the country’s indigenous energy resources—hydropower, local coal, wind, and solar—remain underdeveloped or face significant production declines. These dependencies, coupled with a weakening currency and rising global interest rates, are

driving electricity costs to unsustainable levels for a country already burdened by economic instability.

Now, those that have gone all in on Thar Coal will tell you it is the solution to all of Pakistan’s electricity problems. The difference in the cost of producing electricity from domestic coal and imported coal is substantial. The cost of producing electricity from the Engro plant, which uses domestic Thar coal, is Rs 10.44/kWh, whereas the Lucky Electric plant which uses the same type of coal (lignite) but imports it costs Rs 20.92/kWh, according to data from Nepra’s latest monthly fuel cost adjustment report.

But the Lucky Plant has failed to gain access to Thar Coal. In a recent state of the industry report, NEPRA claimed challenges remain.

Currently, the local coal-based power plants rely on coal from Block-I and Block-II of Thar Coal. The development of Block-II has progressed through its envisioned three phases, but financial closure for Phase-III is still pending. Notably, Lucky Electric Power’s 660 MW project, primarily a Thar Coal based project, operates on a blend of Thar Coal and Imported Coal due to delayed Thar Coal supply.

You have a situation where the requirement is to have more coal plants that can produce electricity through the lignite that is available in Thar, and you need to find cheap ways of transporting it. This challenge has persisted, and even though Thar Coal has come a long way in the past decade, one dream that has remained in the backdrop is the idea to turn coal into gas.

Let us start by getting one thing straight, this is yet another pipe-dream that the government of Pakistan has. They believe that if Thar Coal can be converted into gas in an economically feasible way, they will be able to transport this gas through an extensive network of pipelines and provide it to all kinds of gas consumers. It will essentially be a replacement for expensive and volatile LNG and will do the same job. Almost like discovering new gas reserves.

Of course, this huge network of pipelines does not exist. There is no gas pipeline in Thar currently, and all of this infrastructure will have to be built. But what if they can pull it off? Coal gasification is a process that transforms coal into synthetic natural gas.

Coal gasification and liquefaction technologies have been around since the 18th century. Their supporters argue that they are relatively less harmful to the environment than directly burning coal for energy. Their critics

allege that these technologies have massive capital and operational costs and are too complex to operate smoothly.