Places to Practise

Building participatory practises in Barking & Dagenham through the Every One Every Day initiative.

Building participatory practises in Barking & Dagenham through the Every One Every Day initiative.

Most of all thank you to all the participants of Every One Every day for their excitement, ideas and contributions. Every One Every Day is inspired by the innovative work of hundreds of people locally and across the world who are finding new ways to reshape their communities and helping imagine what re-organised neighbourhoods might be possible in the future.

Participatory City Foundation Research Team

Tessy Britton, Founder

Nat Defriend, Chief Executive Officer

Katherine Michonski, Chief Operating Officer

Ivana Cosmano, Researcher

Dan Robinson, Head of Neighbourhood Development

Hayley Bruford, Head of Learning and Design

Iris Schönherr, Head of Programmes

Saira Awan, Head of Neighbourhood Development

Tim Warin, Head of Operations

Laura Rogocki, Learning and Graphic Designer

Nikitha Pankhania, Graphic Designer

Madeline Contos, Learning Designer

Andres Muniz, Assets and Premises Manager

Claudia Iacob, Operations Manager

Sarena Shetty, Programmes Designer

Adédolapo Yusuf, Project Designer

Bahar Kaplan, Project Designer

Farah Shahab-din-Chaudhry, Project Designer

Imogen Newman, Project Designer

Jessica Broughton, Project Designer

Jack Tatham, Project Designer

Louis Rutherford, Project Designer

Matthew de Kretser, Project Designer

Symbol Obinna Uzoukwu, Project Designer

Winter Lappin, Project Designer

With additional thanks to:

Aggie Pailauskaite

Stephanie Olowe

Ruchit Purohit

Amelie Pollet

Dee Pessoa

Brigitta Budi

Ola Ismail Olopoenia

London Borough of Barking and Dagenham

Saima Ashraf, Deputy Leader, Barking and Dagenham Council

Rhodri Rowlands, Director of Participation and Engagement

Monica Needs, Head of Participation and Engagement

Michael Kynaston, Participation Manager

Claire Brewin, Policy Officer, Community Solutions

Debbie Butler, Community Development Officer, Community Solutions

Trustees

Michael Coughlin

Sophia Looney

Hannah Rignell

Roland Harwood

Noel Moka

Akil Scafe-Smith

Rosanna Vitiello

Tom Hook

With additional thanks to:

Dan Hill

Olivia Smith

Alessandro Ricci

Cities Programme Partner

Friendship Centre Kjipuktutk/Halifax

Project Team

Aimee Gasparetto

Tammy Mudge

Killa Atencio

Kate Sunabacka

Jayme-Lynn Gloade

Richelle Kantor

Jocelyn Spence

Janine Annett

Nat Quathamer

Adria Maynard

Pamela Glode Desrochers

Cities Programme Partner

Corra Foundation

Funders & Partners

London Borough of Barking and Dagenham

Esmée Fairbairn Foundation

National Lottery Community Fund

City Bridge Trust

Greater London Authority

Bloomberg Philanthropies

Barking Riverside Limited

Ikea Lagom

Credit and thanks to Nishant Jain for cover illustrations

The evidence of the work, activities, achievements and outcomes set out in this research report (the third in a series), pay testament to the transformational combination of the active participation of Barking and Dagenham residents, the efforts and commitment of the Every One Every Day team, the backing of funding bodies and support from many others, including the Participatory City Board members and Global Advisors network.

As ever, the important quantitative data set out is trumped by the personal testimonies of residents. Many speak openly and passionately about the effect Every One Every Day has had on them, those close to them and their neighbourhoods and communities.

The quality of the work, integrity of the approach, and results achieved, continue to impress. They also strongly reflect the founding principle of putting people and neighbourhoods at the very centre of the work, with the object of encouraging collaboration between residents, to secure the outcomes they wish for themselves and others.

This report comes at a critical time, capturing as it does the period during the Covid-19 pandemic, which limited the scale and scope of participation opportunities and saw the work shift to developing learning and business development opportunities for residents. It is also half-way through the carefully planned final year of work with the residents of Barking and Dagenham, during which the creation of a sustainable legacy for the work has been the priority.

The past two years have been remarkable for Every One Every Day in many ways. More residents than ever - approximately 10,000 - taking part in more than 80,000 hours of activities, with almost 700 developing their skills and over 40 places improved.

All of this and more has enabled us to contribute to the body of evidence and practical know how around participation systems globally. The open source and shared nature of our practical, demonstrable learning has been a key feature of this. While the work with the people of Barking and Dagenham is foundationally important, we firmly believe there is significant wider value and benefit in this work and approach.

As we now work to leave a strong legacy, in the coming year we will focus on transitioning as much as possible of our practical work in Barking and Dagenham to other groups, bodies and communities; carefully and sensitively gifting assets to others; supporting the Every One Every Day team and capturing, curating and sharing in perpetuity a range of learning materials that will enable others, anywhere in the world to create inclusive, engaging, useful and enjoyable ways of participating, together, that promotes social cohesion.

Much will now depend on our legacy. This will in time be judged, of course, by the sustainability of the work in Barking and Dagenham but also by the replicability and scale of adoption elsewhere in the UK and globally.

None of this would have been achieved without the dedication, commitment and hard work of our Chief Executive, Nat Defriend and his amazing team of staff, many of whom have stepped up and shown such amazing passion and commitment throughout an extraordinarily challenging period.

Our funders have stayed the course and shown unbelievable faith in our work, with the London Borough of Barking and Dagenham playing a particularly important political and placeleadership role. At the heart of everything you read, see and hear about Every One Every Day are the thousands of Barking and Dagenham residents who have participated - often for the first time in their lives - in the activities and in doing so the development of the approach and the securing of so many achievements, successes, and lives changed for the better.

“We don’t have to engage in grand heroic actions to participate in the process of change. Small acts, when multiplied by thousands of people, can transform the world” - Howard

Zinn Michael Coughlin, Co-Chair Trustee Sophia Looney, Co-Chair TrusteeThis new report represents a significant contribution to our existing research on this innovative approach to building inclusive practical participation into our daily lives, both during and after the COVID-19 period.

This report is particularly exciting as it comprehensively outlines collaborative business programmes and enhances our understanding of how social capital is developed.

The true impact of this practical approach is revealed through the words of the residents themselves. Their accounts provide a more personal and human perspective, moving beyond abstract ideas of outcomes.

The scale of this project is truly impressive, and credit must be given to the remarkable residents of the borough. While the team provided the necessary infrastructure and creative strategies, it was the residents who actively fostered friendships and built trust. Importantly, these relationships have transcended cultural and social demographic boundaries. The highly detailed attention to inclusivity in every aspect of how this approach is at the core of this approach, and it proved to be highly effective.

Creating new avenues and opportunities for people to come together is of utmost importance, especially in increasingly diverse societies. The World Economic Forum has identified erosion of social cohesion as the 4th most severe global risk over the next decade. Building social cohesion requires deliberate effort and care, unlike the easier topdown campaigns that often contribute to polarisation and segmentation.

As evidenced by the stories of the residents of Barking and Dagenham over the past 6 years, building social cohesion and building social capital necessitates fostering meaningful relationships between people. As this report sets out, participation platforms hold the potential to create the conditions for this to be possible at scale.

Tessy Britton, FounderA lot has happened since we published our last research report, Tools to Act, back in early 2020.

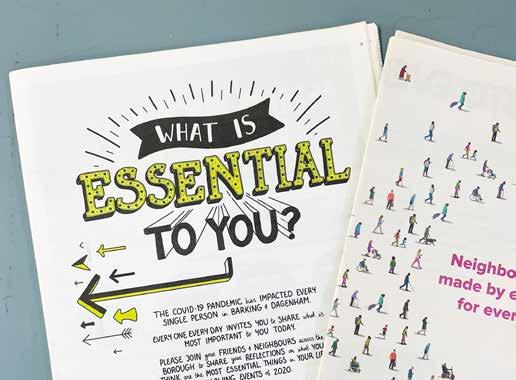

For the residents of Barking and Dagenham life has changed for ever with the borough still dealing with the impact of COVID-19 and the ongoing effects of an enduring cost of living crisis. For participants of Every One Every Day, the platform has changed around them. Firstly as parts of it became inaccessible. Then when it reopened in unfamiliar circumstances, with new limitations, protocols and safety procedures in place.

And for the project team, it has taken time, patience, ingenuity and effort to rebuild connections with residents and reignite the ecosystem of projects, programmes and collaborations which are the driving force behind the outcomes achieved through this model of participation.

In some significant ways things have changed irrevocably. It has not been possible to recapture the momentum which drove the development of Everyone’s Warehouse before March 2020 and some residents never returned to the project after the rupture of the pandemic. But in many others the project has been able to extend and develop its approaches, methods, understanding and impact over the intervening years since the publication of Tools to Act.

Most significantly, this report sets out our latest understanding of how the experience of participation creates social capital amongst participants which they can then use to create outcomes at individual, community and societal level.

It also introduces for the first time a comprehensive description and analysis of the collaborative business programme which has emerged as a key component of the model since it was initiated in 2018. As Chief Executive Officer it has been a privilege to lead Participatory City Foundation for the last two years. I want to pay particular thanks to our incredible team who have kept their enthusiasm and drive throughout everything which has been thrown at them over the past two years. I want to thank our amazing trustees, funders and partners who have supported the project so firmly.

And most of all I want to thank the people of Barking and Dagenham, who are creative, challenging (in a good way!), resourceful, resilient, and a constant inspiration.

Nat Defriend, Chief ExecutiveAt Esmée Fairbairn Foundation, we want to strengthen the bonds in communities, helping local people to build vibrant, confident places where they can fulfil their creative, human, and economic potential. As a funder, we have learnt that local, place-led funding can reach people and tackle challenges in uniquely innovative ways.

Every One Every Day is a fantastic example of that. Their approach supports local people to have a deeper level of participation, co-creating activities and projects with other residents, which offer benefits to the wider community. Whilst pandemic restrictions meant parts of their strategy had to be pushed back, they were able to adapt and respond to the community’s needs, and make faster progress in other areas. For instance, they developed a digital platform, providing an online space for residents to connect; provided free project toolkits to support activities at street level; and accelerated their collaborative business incubator programme. We’re grateful to Participatory City Foundation for sharing their journey, research and learning along the way, which continues to inspire and inform our place-based and place-led work.

Esmée Fairbairn Foundation

This report is the first publication from Participatory City Foundation for three years.

Since the publication of Tools to Act in early 2020, the world has changed dramatically, and with it, the lives of the residents of Barking and Dagenham. As the borough has changed, so have the approaches, methods, and day-to-day work of the Every One Every Day project.

Places to Practise brings the account of this work up to date (to December 2022). It summarises how the platform adapted to the unique challenges of the COVID-19 period, and emerged from it, including an assessment of how successful the platform was at recapturing the momentum lost to the pandemic.

For the first time, this report contains a comprehensive description and evaluation of the Collaborative Business Programme, which itself has been through multiple iterations over the past three years, and, as a key vehicle for self-directed learning, is properly understood as a fully integrated component of the full-scale participation system.

Alongside detailed descriptions of the evolution of the system and the new elements which have been prototyped and tested within it, this report sets out the latest evaluation evidence arising from the data analysis and research activities undertaken since early 2020.

These lead to a key insight within this report which, it is contended, is of critical importance for those involved in city leadership, urban policy and strategy, and community and neighbourhood development; this is the clear evidence emerging from this

research that, for participants, the accumulated experience of practical participation is directly linked to the development within individuals of increased social capital, understood as the trust, cooperation, and resources that are built and shared among individuals and groups through social connections.

Furthermore, this report also sets out the connection between increases in individual social capital, and the collective effect of this at scale for communities and society more generally.

This means that participation systems can be understood as infrastructure for the generation of social capital at scale.

As such, and drawing upon the extensive evidence base for the significance of social capital in improving lives and communities (for example, Bourdieu (1986), Coleman (1988), Putman (1993) and Cloete (2014)) it is contended that flourishing participation systems, enabling residents to connect, share, create and collaborate, should be an integral part of all communities as we meet the challenges and opportunities of the coming decades.

Aims and Purpose of the Report

Borough Context

Project Background

Project Development

Report Structure

50

An Interconnected social system

The participatory support platform

The participation ecosystem

Ecosystem growth

Registered participants

Participation patterns

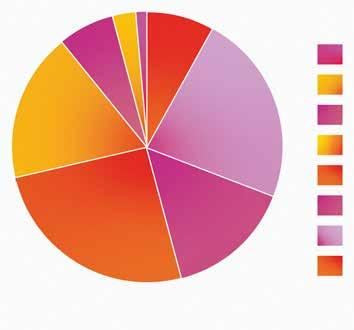

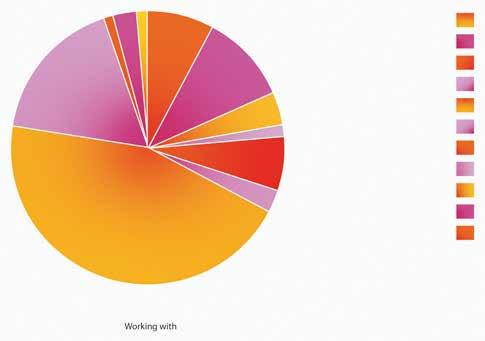

Participation diversity

Platform developments

Ecosystem developments

The COVID-19 Pandemic

138

The Participation Ecosystem

Collaborative Business Programmes

Ecosystem Case Studies

Model Adaptability and Partnerships

218

Key Findings, Platform Impact and Outcomes

Key findings and platform impact

Practical Participation in Context

Outcomes and Impact

Participant Case Studies

Multi-levels Outcome Framework

274

Summary and Conclusion

Key findings

Research limitations

What next?

Every One Every Day, hosted by Participatory City Foundation, is a research and demonstration project which, for the past five years, has been working at the heart of Barking and Dagenham in East London to build the world’s first full-scale practical participation system.

The project builds on eight years of prior research on new models for building sustainable urban neighbourhoods around the world.

These asset-based and decentralised approaches were highly diverse in form and content but united by a simple and powerful idea: that everyone has ideas and contributions to bring and that by designing for inclusion and with the right invitation, everyone could participate in building their neighbourhood.

The prior research also highlighted another key insight: that to survive, these participation projects had to convert to another form, such as a social enterprise or charity, and that in doing so they often lost their essential, inclusive, and participatory nature.

Every One Every Day is the first attempt anywhere in the world to build a local system that can enable the development of inclusive participatory opportunities at scale, and sustain them, whilst preserving the elements which make them different.

Participatory City Foundation’s previous publication, Tools to Act (2020), described the first two years of the Every One Every Day project, which included the initiation and growth phases. Subsequent reports were intended to describe how the project scaled across the borough, how it integrated with the existing systems present locally, and to evaluate and describe the impact created by inclusive practical participation for local residents.

In the intervening years the world has turned on its head. In-person participation - the primary driver of individual outcomes in this model - became impossible due to social restrictions arising from the Covid-19 pandemic, and, while the project delivered a huge amount during this period, taken overall, an 18-month hole was knocked into the participation data collected by the project.

Since August 2021, the project has been able to reopen its doors to local residents and to begin, often painstakingly, to rebuild the momentum lost to COVID-19. In doing so, the project has worked with residents who were amongst the worst affected by the pandemic anywhere in the UK.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the project’s funders agreed to extend funding for a further two and a half years to allow the project to achieve its original research aims.

At the time of writing, Participatory City Foundation has raised over £9 million of investment into this research project through an enduring and deep collaboration with this extraordinary group of funders and partners. The project has engaged approximately 10,000 local residents, and created over 300 new projects, learning programmes, and collaborative business opportunities in the borough.

This report brings the story of the Every One Every Day project up to date. It reminds readers of the overarching aims of the initiative and goes on to describe how the core elements of its work have emerged from and been changed by the pandemic. This includes a detailed focus on the design and delivery of the collaborative business programme, which has developed substantially since the publication of Tools to Act.

The report contains a full presentation of all the data and other evaluative evidence gathered since the beginning of the project and analyses what this tells us about the impact of practical participation in Barking and Dagenham over the past five years. Most significantly, it updates the project’s outcomes framework to include how the model is a platform for the creation of social capital, and how increased participation results in increased levels of social capital.

This case is made throughout this report including the evidence amassed to support it. It is contended that this is a highly significant finding of relevance for all those with an interest in the way we design our social systems and communities, particularly those in urban settings.

This report should be read in conjunction with Tools to Act and is intended as the penultimate published output from the research and development phase of this project. A final, comprehensive reporting covering all aspects of the model, the data, and the evaluation evidence and the analysis, including recommendations for other places wishing to adopt this approach will be published in late 2024.

Every One Every Day is a research project that seeks to develop and test the impact and potential of practical participation at scale in a London borough.

The research was designed to examine a set of key questions, including feasibility, inclusivity, value creation, systemic integration, and scalability of the model.

The project applied a developmental evaluation approach to generating, analysing, and codifying the learning arising from the experience of building the participation platform in Barking and Dagenham.

This approach was selected for its suitability to the design-based, emergent, and iterative nature of system building. By engaging all team members, residents and partners in the research and design, the approach was able to adapt to the changing circumstances of the project over the past five years. This has been particularly important since the COVID-19 pandemic.

This report is the third research publication arising from the Every One Every Day project in Barking and Dagenham. It follows Made to Measure, published in April 2019, and Tools to Act, published in April 2020.

These two reports described the experience and learning generated by the project over its first two years as it set up and established itself in Barking and Dagenham and sought to scale its activities across the borough.

By early 2020, the platform had reached full scale before the COVID-19 pandemic necessitated a fundamental change to the project approach.

The original research strategy envisaged annual reports over the course of the five year research project, culminating in a final publication that would draw together all the learning in a comprehensive account.

As a result of the changes to project approach in March 2020, the project has not published a report since Tools to Act in April 2020.

This report therefore aims to bring the public account of the project up to date by describing how the platform adapted to the unique challenges caused by the social restrictions imposed in March 2020 and how it emerged from this phase and sought to rebuild momentum lost to the pandemic.

The report sets out for the first time a comprehensive account of the design and delivery of the Collaborative Business Programme, which has developed substantially since the publication of Tools to Act.

It also shares all the qualitative and quantitative data the project has gathered about the nature and scale of participation since project inception. It sets out the latest iteration to the project’s theory of change, which ties participation to the development of increased social capital amongst participants.

This report is intended to be the penultimate publication from the research and development phase of Every One Every Day in Barking and Dagenham.

Participatory City Foundation plans to produce a final comprehensive report covering the entirety of the project in 2024.

The London Borough of Barking and Dagenham (LBBD) is situated in East London with a population of 218,900 (2021). The borough has experienced the third highest population growth in England and Wales since 2011 at a rate of 18 percent. Barking and Dagenham’s demographics have also changed rapidly over the last 20 years, from 79 percent White British in 2001, to 45 percent in 2021.

In the last ten years, Barking and Dagenham witnessed the highest percentage change in residents born outside of the U.K. across London boroughs. This, in combination with the highest level of household deprivation in London, at 62 percent, has posed a challenge for community cohesion and resident well-being.

The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated the borough’s pre-existing inequalities. Many residents continued to go out to work as key workers. Rates of exposure and infection were high, putting additional strain on families and the health sector, while some lost their jobs and their family’s source of income.

The borough also faces a number of socio-economic challenges, including low incomes, underemployment, poor educational outcomes, and high levels of homelessness, teenage pregnancy, and domestic violence. Social cohesion also remains a challenge.

In recent years, the London Borough of Barking and Dagenham’s local council has worked closely with voluntary, community, and social enterprises (VCSEs) to establish stronger and more trusted relationships for developing social infrastructure. The Council has endeavoured to develop a facilitative and participative role in the borough, sharing a place at the table for VCSE organisations to do what they do best and improve outcomes for residents. Because these groups know what their communities need, sharing power between statutory and VCSE partners results in a better offer for residents.

This commitment to a more collaborative way of working and the associated social infrastructure was exemplified in the establishment of a locality model of cost-of-living support in autumn 2022, when the Council brought together a network of local organisations to provide informal triage support. This network stretched from the local hairdresser or faithbased organisations, to Council frontline services, to ensure that residents across every area of the borough can access the right help to get them through the crisis.

The combination of need and the adoption of a new way of working put LBBD in a unique position. The borough hosted the Every One Every Day initiative for three main reasons which remain true today:

• The level of need in the borough is widespread, everyone needs to see tangible improvements in their lives;

• The Participatory City model matches the ambitions for working collaboratively with residents;

• The leadership at the Council is united and determined to innovate to improve resident lives.

Five years into Every One Every Day’s setup, the Council continues to be a strong advocate for participation and the sharing of power between the state and communities. Participation and engagement are built into council strategy and stood as a pillar of the 2020-2022 Corporate Plan.

The Every One Every Day project created thousands of participation opportunities that have benefited residents, and has shown what can be achieved through collaboration and by allowing residents to take control of their own lives.

The Council is committed to embedding the approach of Every One Every Day across the borough for the long-term, to ensure that residents can continue to get involved in their communities.

Open conversations with the VCSE will help decide what the next steps are for the borough in embedding a participatory ecosystem. This will be done through a partnership approach between the council, Participatory City, and social infrastructure partners to continue to provide opportunities or residents to participate and enjoy the benefits that meaningful participation can bring.

The design for Every One Every Day resulted from over eight years of prior research into the nature, impact and practice of practical participation culture projects across the world.

These citizen-led local projects were achieving social outcomes through an emergent approach which involved a broad based and inclusive invitation to local residents to get involved in ‘common denominator’ activities such as cooking, learning, and making. The result was a community based project model which enabled people to co-produce something tangible as part of a group of equal peers.

Analysis of the outcomes produced by these projects showed that they were able to create many positive impacts for participants including learning, social cohesion and health. They did so by incorporating some or all of the following characteristics which have been adopted as inclusive design principles within Every One Every Day:

Equality

Attracting a diverse range of participants.

Mutual benefit Involves people contributing and benefiting in a single action.

Peer-to-peer Involves people working peer-to-peer on an equal footing.

Productive activity Involves producing tangible things together.

Open accessibility Involving as many people as possible, through working to reduce all types of participation barriers.

Analysis of these projects also demonstrated that their ability to achieve outcomes over the longer term was constrained by the lack of a supportive infrastructure which could enable them to continue to do so without converting to another form in order to raise funds.

Many of the projects which did survive eventually had to develop a business model or adopt a charitable form for this to be possible. As they did they lost the essential inclusive and participatory approach which made them different and entered into a challenging and competitive environment for local funding.

Over nine years of testing and planning, including four research cycles, Participatory City Foundation has drawn on this analysis to develop a comprehensive systems approach to growing a large network of projects which can create an inclusive environment for people to participate.

Throughout our literature including this report, this is referred to as the Participation Ecosystem. This term is used to convey that the intended outcome is an inclusive environment made up of interconnected elements, but not dependent upon any single one for its continuation.

In the envisaged participatory ecosystem individual residents will come and go as their lives change; projects will emerge, develop, adapt, scale and close. The ecosystem will remain irrespective of what happens to any particular part.

This ecosystem is supported by the Participation Platform made up of social infrastructure which is designed to be fitted into cities, boroughs and neighbourhoods and which acts to enable the development of the ecosystem in the form of participation projects and networks of residents. This model is based on Designed to Scale, the first attempt to articulate a comprehensive account of this design approach to a system built around 14 (now 15) inclusivity principles for practical participation.

Every One Every Day is the first attempt anywhere in the world to attempt to build a prototype of this system at scale in a city environment.

To achieve this has required the support and strategic input of an extraordinary group of Trustees, and a

funding collaboration involving The London Borough of Barking and Dagenham, Esmee Fairbairn Foundation, the National Lottery Community Fund, City Bridge Trust, Bloomberg Philanthropies, and the Greater London Authority.

During the first phase of the project in particular, these funders aligned their funding and reporting requirements to enable an iterative and emergent implementation strategy aimed at producing a broad set of outcomes and capable of adapting to the changing context.

Underpinned by a close working relationship with the council, particularly the Participatory and Engagement Team, the result is a unique body of evidence about the design, feasibility, impact and potential of social infrastructure for practical participation.

Tools to Act covered the first two years of the project plan, up until the end of July 2019. By July 2019, the platform had reached nearly full capacity, with the fourth neighbourhood space opening in Martins Corner in November 2018 and the recruitment of six new project designers. The 2019 autumn programme, which ran from October to December 2019, saw a continuation of the rapid growth pattern in participation levels that had characterised the project since it’s inception. With another shop space opening in Marks Gate in 2020, there was every expectation that this growth pattern would be replicated over the succeeding months and years.

At the point the pandemic hit, the project was on the brink of its 2020 spring programme. This would have been the biggest programme since the launch of Every One Every Day , including for the first time activities in the Marks Gate area of the borough. Restrictions on social gatherings were imposed from March 2020. This severely limited the ability of the project to create outcomes by bringing together as many people as possible as often as possible. Participatory activities were not classified as essential activities and therefore were not permissible reasons for in-person contact under the new restrictions.

In one fell swoop, the key tool for generating outcomes through this form of participation became impossible. In the immediate period after March 2020, the project sought to reshape its approach towards supporting the borough-wide pandemic relief effort and to build models of participation capable of being implemented under social restrictions.

Participatory City Foundation was a key partner in the development and execution of the Council’s approach to co-ordinating and providing relief, called BDCAN. BDCAN coordinated the provision of food and medical supplies to local residents at risk of being made vulnerable. Every One Every Day’s largest space, Everyone’s Warehouse, became a critical centre for the assembly and distribution of food parcels through local volunteers.

To adapt the participation model to social restrictions, in mid-April 2020 the team launched an online participation space, using the Mighty Networks platform. In June, it had developed a new approach

to enabling street level collaborations with minimal requirement for in-person support from the team, called Tomorrow Today Streets.

These steps had some success in ensuring that Every One Every Day continued to provide opportunities for participation, even under stringent social restrictions. However, the ability to attract new members was severely undermined and effectively flatlined during the two years where social restrictions applied. Another key development during the COVID-19 pandemic, was the launch of the Every One Every Day Kickstarter programme.

With funds from the HM Treasury Kickstart scheme, a programme aimed to create 25 local apprenticeships for young people on universal credit and invited them to build the foundations for their own locally owned worker co-operatives focussed on the production of goods essential to people’s lives. This scheme was permissible under social restrictions because it was work that was only possible to deliver in-person due to the training and production element involving Warehouse workshop spaces. This scheme ran for six months from April 2021.

In summer 2021, it became evident that there was the potential for a lasting relaxation of social restrictions and therefore the possibility of a gradual resumption of in-person participation. Recapturing the momentum lost during the pandemic was critical to the research and development strategy underpinning Every One Every Day. Nearly 18 months of participation data was lost due to social restrictions, jeopardising the project’s ability to effectively evaluate the model and produce learning and recommendations for the future development of participation approaches. Re-opening after a long and unplanned period of closure was complex and involved an entirely new layer of procedures and processes over existing participation approaches in order to comply with ongoing restrictions.

Examples included social distancing and space limitations at neighbourhood events, requirements for masking and one-way systems for entry and exit to spaces. As with other changes in behaviour caused by the pandemic, the residents of Barking and Dagenham also changed their participation patterns.

Residents were much more likely to participate closer to where they live, and less able to access opportunities further afield.

This particularly limited resident use of the Warehouse, and the ability of the project to run programmes from this building. Over the course of 2021 and 2022, a number of prototypes for how to recapture this lost momentum and rebuild resident confidence were developed. Some of these experiments have been successful and have significantly advanced knowledge about the model (for example Grounded, a collaborative coffee shop incubated by the platform), others have been less so.

This report provides a comprehensive account of the adaptations made to the model to rebuild after the experience of social restrictions, with a particular focus on the developments surrounding the Collaborative Business programme.

Under the original project plan set out in 2017, Every One Every Day was due to conclude its research and development phase by July 2022 with the aim of publishing all learning and data at this point alongside the case for continuing the project. In response to the reduction of participation data due to the COVID-19 pandemic, in November 2021, the project funders agreed to invest funds to extend the project to 2024.

This aimed to enable the platform to recapture lost momentum, further iterate the approach, and complete the research and development phase. This second phase of the project was based upon an updated research plan, designed to incorporate new learning about how the participation approach adapted to the experience of the pandemic and its aftermath. This plan included a focus upon integration with other parts of the social infrastructure in Barking and Dagenham and an emphasis upon testing the participation ecosystem as a unique, self-directed learning environment for residents.

The first section of the report sets out the research approach, describing the key developments, research questions, data gathering methodology, and analysis approach.

The main body of the report contains a summary of the research data gathered by the Every One Every Day project as well as a descriptive account of the key components of the participation system and their developments since the publication of Tools to Act over three years ago. The centrepiece of this section is the first full account of the development of the Collaborative Business Programme, which is now understood as an integral part of the participation system.

The descriptive section has been written with contributions from members of the Every One Every Day team who have provided case studies to illuminate elements of the platform and ecosystem in detail.

The ‘Key Findings’ section on page 218 sets out the link between the experience of practical participation and the development of social capital for individuals.

The final section of the report summarises the preceding content and draws together some highlevel conclusions including the implications for the remaining elements of the research plan for Every One Every Day.

Research

Research developments

Research aims

Research questions

Research design and methodology

Qualitative fieldwork

Qualitative research stages

Data analysis

The research strategy behind Every One Every Day in Barking and Dagenham is based on over eight years of prior research that has demonstrated the value of practical participation projects in creating more sustainable cities. The goal of Every One Every Day is to establish a network of participatory culture projects on a large-scale, which can achieve longterm social outcomes that benefit individuals, their communities, and society as a whole.

Participatory City Foundation has developed a systems approach that facilitates the development of a wide range of neighbourhood project opportunities and provides the necessary support for these projects to succeed. The approach aims to create a Participatory Ecosystem that consists of interconnected neighbourhood projects and networks of residents, along with a Support Platform to maintain and grow these initiatives.

Since its launch in July 2017, the Every One Every Day project has aimed to prototype a new model where societies are more inclusive, equal and where citizens are at the centre of their communities with access to tools and resources they need to drive positive change on a personal and societal level.

Year one findings from the project showed that residents’ involvement in practical participation projects triggers a series of individual, collective, and networked effects, resulting in positive outcomes for individuals, families, and neighbourhoods. Repeat participation appeared crucial so that these effects could be triggered, however, the sequence through which these effects were produced did not appear clear.

Two years after the project was initiated, research was conducted to further investigate the benefits achieved through participation, providing more insights into how outcomes are achieved.

Year two research findings highlighted that there is a “bundle of outcomes” relating to individual agency and personal well-being that constitute the gateway to other “compound outcomes”. Again, findings confirmed that repeat participation is crucial for outcomes to be achieved, as these accumulate over time.

The project faced an 18-month gap in participation data during the COVID-19 pandemic, limiting its capability to continue researching the value created by the participatory model in Barking and Dagenham. Since the reopening of the shops in August 2021, the project has worked to redefine its research strategy to tackle new compelling questions and further the understanding of the model.

Overall, findings from years one and two proved that Every One Every Day’s systems approach applied in Barking and Dagenham was succeeding in building large-scale participation that benefits individuals and communities, contributing to empowering individuals, enhancing their well-being, and strengthening communities ties.

The latest phase of the research and development project has focused on understanding the role that participatory models play in increasing social capital, fostering a sense of neighbourhood belonging, and civic engagement. This phase has provided insights into how applying participatory culture models positively impacts numerous dimensions of social life, ultimately resulting in a greater sense of wellbeing and quality of life for individuals and communities.

The current report builds upon the previous research findings to further develop the body of evidence around this approach to participation. It sets out a revised framework of research aims and questions which aim, on the one hand, to review previous findings and, on the other, to shed new light on the diverse dynamics of participation and related outcomes.

To do so, the research aimed to identify the main drivers of resident participation. It explored individual journeys of participation and the main drivers, expectations, and aspirations for residents and the borough. From this, a typology of participation was developed and used to investigate whether different types of participation can be tied to different participation outcomes.

Contextualising individual participation journeys also helps uncover all the potential outcomes that inclusive practical participation opportunities provides. These findings can help practitioners and researchers use the model to address specific social challenges or achieve specific goals, such as creating equitable, resident-led community development.

Understand people’s motivations to participate

Explore people’s participation journeys, particularly how motivations, expectations, and aspirations may change

Understand the benefits of participation that accrue to individuals

Understand the benefits of participation that accrue to society

Explore how participation can create social capital and social cohesion

Below are the research questions that guided this phase of research.

By answering these questions, this report hopes to contribute to the scholarship on participatory research and enhance understanding of how social capital and cohesion in urban settings can be achieved through participatory activities.

In doing so, it can help catalyse positive social change that is co-designed and directed by citizens.

• What motivates people to participate?

• What are the different types of participation and their related outcomes?

• Has participating helped improve people’s lives by building their agency? If so, how and to what extent?

• What outcomes are generated through the large-scale nature of the project?

• Is the systems approach still creating value for individuals and the community that was observed in Year 1 and 2? Has this changed? How and why?

• What benefits did participation culture generate for people on both a personal and community level?

• What is the project’s theory of change and how does it achieve impact?

• What evidence do we have that the platform creates social capital amongst participants?

• Which participation experiences drive the creation of social capital?

• Does the model create meaningful and real change in people’s lives?

• What is the value of the model for communities and societies? What is the value of implementing at a large scale?

• How can the model be improved so that it can be further scaled to future communities?

The research applied a mixed research methodology, using both quantitative and qualitative methods of data collection.

As the project progressed, additional research methodologies have been developed in order to address emerging research questions and fill gaps in previous research, as well as to reflect new research objectives.

A complete list of the research methods applied during the second phase of this project and their purposes are outlined below.

Data-gathering methods:

• Daily reflections

• Participation dashboards

• Weekly developmental evaluation report

• Sign-up form

• Equality, diversity and inclusion monitoring survey

• Interviewee profile

• Structured interview

• Semi-structured interview

The team maintains a daily diary of reflections and observations about participation arising from the experience of hosting shops and delivering programmes. These reflections are a critical source of data on participation across the platform including who attends, whether they are new or returning participants, if they were accompanied, how long they stayed and what they did.

The daily reflections are aggregated and summarised into an automated participation dashboard that provides a real-time picture of participation patterns and growth across the ecosystem. The dashboard helps identify participation patterns across shops, activities, and programmes.

Each team completes a weekly developmental evaluation analysis, inviting them to reflect on: what happened in the shop that week, notable features in the data, reflections on the model, and one new idea to try. This evaluation approach enables the teams to regularly analyse the effectiveness of the platform and to use evidence to iterate their plans and approaches. This approach also helps Participatory City Foundation test hypothesis and improve understanding of what types of participation are most successful and why.

Residents that come into shops are invited to fill out a “sign-up form” to join the Every One Every Day mailing list and receive information about events in the shops. The form enables residents to share information about their backgrounds and interests so that project communications can be targeted to them appropriately. By signing up, residents also give permission to be contacted for research purposes.

This survey collects anonymous demographic data about participants, helping the team build a better understanding of who is participating and to ensure that the project remains inclusive

The structured interview is a primary tool in qualitative fieldwork. It assesses the strength of participants’ commitment to participation as well as their general expectations and motivations to participate. Combining this data with those collected by the interviewee profile and semi-structured interview, can help determine how commitment levels relate to individuals’ expectations and ambitions for change. This helps identify any relationships between repeat participation and outcomes.”

Residents who agreed to be contacted for research on their sign up form may be invited to be interviewed about their experience of participation, creating an Interviewee Profile. The profile gathers demographic data and qualitative information about their participation experience. This information helps assess how dimensions such as gender, ethnicity, employment status, education level, and marital status affect participation. Finally, the data collected in the profile helps to deepen the understanding of similarities and differences in participation dynamics, as well as patterns leading to outcomes.

The semi-structured interview is a one-to-one in-depth interview with residents in the form of a natural conversation between the researcher and the participant. It examines the participant’s personal participation journey, and aims to capture the impact of the model on people’s lives, as well as individual and broader outcomes. The main aim of the semi-structured interview is to assess the model’s potential to generate wider benefits at a borough level, providing insights into how the model creates social capital.

In autumn of 2022, qualitative fieldwork was carried out to enhance understanding of a model and its benefits for participants.

This qualitative fieldwork was designed to provide a comprehensive understanding of how the model operated in Barking and Dagenham, as well as to assess its suitability in other areas.

This section provides a detailed account of the data collection process, as well as information about participants interviewed as part of the fieldwork. It also includes the research aims and questions for each data collection method used.

Aims

The fieldwork approach aimed to achieve the revised research objectives, address new inquiries, and most importantly, evaluate the model’s ability to create social capital and improve social cohesion in the Borough.

Although each method targeted diverse research aims and questions, their results were triangulated not only to verify the accuracy of the data analysis but also to gain deeper insights into participants’ experiences and identify participation patterns that resulted in both personal and social benefits.

A total of 30 participants were recruited and interviewed on the basis of two sets of criteria:

• The duration and frequency of participation (how long had they participated for and how much did they participate)

• The nature of participants’ relationship to the project (for example through shops, the Warehouse or via the collaborative business programme).

Afterwards, participants were organised into categories according to:

• Length of participation (i.e., long term (above 2 years participation) or recent participants (less than 2 years participation))

• Primary entry point into participation (i.e., shop, Warehouse, collaborative business programme)

• Depth of participation (for which levels of induction into various aspects of the platform was used as a proxy)

These selection criteria were chosen to create a heterogeneous sample of participants, which specifically captured a diverse range of experiences and outcomes reflective of the main groups within the project’s participants.

This approach was selected for its suitability to enable an analysis of how outcomes are achieved for individual participants and to begin to formulate a participation typology which can become the basis of future research.

Limitations to this sampling method

This sampling method does not capture the experience of those in the very early stages of participation, or who had stopped participating. While some barriers and constraints on participation can be inferred

from the qualitative research, additional research with those whose participation had ended would be needed to develop firm hypotheses and conclusions.

It is also clear that the sample, though reflective of the diversity of the borough, is not proportionally representative of the prevalence of diverse groups. This limits the extent to which the findings can be generalised and the resulting conclusions presented in this report, should be understood as representing new hypotheses, rather than firm findings.

A two-stage recruitment process was employed to select participants. In Stage 1, the shop teams identified potential participants who met the participation criteria. In the Stage 2 , each potential participant was contacted via email, phone, or in person by the shop teams and research staff.

Each participant was invited to one or more research activities, such as structured and semi-structured interviews. Interviewees who agreed to participate in semi-structured interviews were required to complete an interviewee profile and structured interview before the actual interview. To improve the likelihood of recruitment, £5 vouchers were offered to interviewees.

The process of recruiting participants commenced in early September 2022, and the fieldwork interviews were conducted between October and November in Barking and Dagenham. The primary fieldwork locations were the Every One Every Day Shops and Everyone's Warehouse. To accommodate participants' specific needs, some interviews were conducted online.

The qualitative research fieldwork activities included an interviewee profile, structured and semi-structured interview, and focus groups. Those activities were divided into two stages focussed on achieving distinct research aims.

To map sample participants’ demographic profile.

To understand residents’ participation patterns in relation to their expectations and motivations.

The semi-structured interview helped evaluate the impact of the model on participant’s lives. By quantifying outcomes and categorising participation patterns, it also aimed to assess the project’s potential to generate social capital for participants.

• Who are the Every One Every Day fieldwork participants?

• How do the individual demographic variables intersect with each other to create different experiences of participation?

Participants in the research project were asked to complete a survey asking questions about their demographic profile. The resulting demographic profiles enabled triangulation of research methods to address research questions from multiple angles, mitigate biases, and deepen the understanding of the model.

• How long have participants been involved with Every One Every Day?

• How frequently do they participate?

• What are the main factors that motivate them to participate?

• What benefits do they ascribe to their participation?

• What is the relationship between participation duration and frequency and outcomes for individuals, families, and neighbourhoods?

The structured interview collected general information about people’s participation patterns, including duration, intensity, and motivations. Furthermore, it collected subjective data on the actual and desired outcomes achieved through participation.

The structured interview comprised 18 multiple-choice questions that helped inform the semi-structured interview. The structured interviews developed a narrative of the resident’s participation journey, generating case studies that outline the role of repeat participation and the specific outcomes that result from it.

• How do residents understand and describe their participation journeys and motivations for participation?

• What direct and personal outcomes do participants report and how do these relate to increases in individual agency?

• What are the potential social outcomes of participation, specifically participants’ potential to develop collective agency and social capital.

The semi-structured interview comprised 37 open-ended questions, in which the research participants were invited to articulate their views and opinions in depth.

Additional questions were added for participants on the collaborative business programme. Interviews took place in an Every One Every Day location and lasted about one hour.

The research has been designed and conducted in accordance with best ethical practice for social research.

A structured approach to data collection and management is critical to be able to conduct social research ethically and efficiently.

In order to ensure accuracy, both semi-structured interviews and focus group discussions were recorded using audio equipment.

Once transcribed, the voice recordings were securely disposed of. These recordings were uploaded to a shared drive immediately after the interviews were completed and will be kept for a maximum of three years after the end of data collection.

The recorders were cleared of all recordings after the upload. The transcriptions were completed by a team of transcribers and then uploaded to Delve, which is a tool for qualitative coding and analysis.

To protect the privacy and identities of the participants, their information has been anonymised and they have been assigned pseudonyms. The confidentiality of the shared information has been guaranteed, and no information has been disclosed without consent.

Before starting the interview, each research participant was provided with a participant information sheet detailing the purpose of the study, the methodology applied, their involvement in the research and information about data storage and confidentiality.

Participants were also asked to complete a consent form requiring them to confirm that they understand the voluntary basis of their involvement in the research and agree to allow the project to gather and use the information they provide.

The primary method of data analysis used in this research is grounded theory, which is based on inductive reasoning to reveal meaning, patterns, and behaviour.

The research used open coding, axial coding, and selective coding to generate new concepts, codes, categories, and subcategories, ultimately leading to the identification of one core category that represents the main theme of the study.

Interviews were conducted until theoretical saturation was reached. In addition to qualitative methods, the research relied on various quantitative data sources to investigate the phenomenon of participation from different perspectives, addressing multiple research objectives.

To ensure the validity and reliability of the data analysis, the research applied data triangulation, including method triangulation and data source triangulation.

Method triangulation involves the use of multiple qualitative and quantitative research methods, such as interviewee profiles, structured interviews, semistructured interviews, daily reflections, weekly participation dashboards, and developmental evaluation reports, to answer specific research questions.

Data source triangulation involves collecting data from multiple types of research participants to capture multiple perspectives and nuances of the same phenomenon. Ultimately, the research relied on data analysis triangulation to draw findings and concepts from the data using an inductive method.

The research utilised different research methods to understand different research questions. Quantitative data analysis was used to answer general questions about the feasibility of the model and its impact on the neighbourhood from the perspective of residents. Semi-structured in-depth interviews were used to answer specific questions about the value, outcomes, and overall impact of the model on a personal and immediate community level.

The interviewee profile and structured interviews were used to understand the needs, aspirations, and expectations of change of different categories of participants on a personal and societal level.

The participatory support platform

The participation ecosystem

Ecosystem growth

Registered participants

Participation patterns

Participant diversity

Platform developments

Ecosystem developments

The platform during COVID-19 Pandemic

Every One Every Day is the first attempt anywhere in the world to build a full-scale system for practical participation.

The system aims to create a diversity of opportunities for local people to participate in their neighbourhoods and further afield. Through inclusive participation, people learn and share skills, connect and develop ideas with one another, and create their own communities.

This system is made up of two components;

The participation support platform is infrastructure, such as spaces, access to a skilled project design team, project resources, and making opportunities. All elements of the system are designed according to 15 inclusivity principles that help ensure opportunities are accessible and fit around people’s lives.

The participation ecosystem is an ever-changing network of local people, projects, and collaborations that create thousands of inclusive opportunities for local residents to participate in practical, enjoyable activities in their neighbourhoods.

Design principles for inclusive participatory ecosystem

Low time and commitment. No or low cost.

Simple and straightforward. Many opportunities with wide variety. Nearby and accessible.

Opportunities from beginner to expert. Promote directly and effectively. Introduce or accompany.

Tangible benefits to people. Attracting talents not targeting needs. Fostering inclusive culture.

100% open - no stigma. Build projects with everyone. Welcome children. Everyone on equal footing.

A collection of many and varied practical ‘participatory culture’ projects and collaborative businesses.

A collection of co-ordinated shared infrastructure

Network of shops and warehouse

Makes it easier for many people to participate regularly in practical projects that fit with their everyday life.

Operations and logistics

Makes it easier to support, maintain and grow collections of projects.

Design principles of support platform

A system of practical support. Makes it easier to start and grow ideas. Works quickly.

Reduces and shares personal risk. Proper co-production design. More people involved as co-builders. New ways for organisations to collaborate. Support collections of projects. More opportunities to grow confidence.

Trained team

The participation support platform comprises the infrastructure that enables the production of the ecosystem.

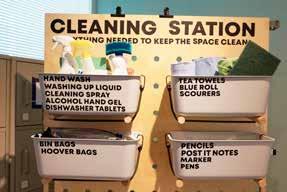

There are three core components of the support platform: spaces, a skilled team, and access to tools and resources.

The network of neighbourhood spaces act as incubators for neighbourhood-based project development. They are strategically located across the borough to be accessible to where residents actually live and work. The goal is for all residents to be less than a 15-minute walk from a neighbourhood shop.

The team of project designers are specially trained in inclusive project design principles and models of collaboration. They have a skill set that includes: working with people, hosting spaces, co-designing projects and programmes, and co-delivering activities and events on a large scale.

The last part of the support platform is inclusive access to the tools needed to deliver the ideas emerging from co-design. These tools range from project materials needed to run sessions, to the machinery and functional spaces housed in Everyone’s Warehouse. Inclusivity is created by a set of operational processes including access to insurance, certified training (food safety, health and safety, etc), keyholding inductions, and booking systems to reserve spaces.

A system of practical support

Makes it easier to start and grow ideas

Works quickly

Reduces and shares personal risk

New ways for organisations to collaborate

Co-production design

More people involved as co-builders

Support collections of projects

More opportunities to grow confidence

The participation ecosystem is a constantly evolving set of project ideas and activities that are continuously being designed, tested, grown, paused, discarded, or replicated. Analogous to ecosystems in the natural world, the participation ecosystem is a complex system that develops organically, is unpredictable in form, and is rooted in the shifting and interdependent relationships of many diverse and distinct parts.

The participation ecosystem shares the following characteristics with other organic models:

• Interdependence and diversity of parts

• The ability to adapt, learn and evolve

• Emergent behaviours or properties

• Organic or natural growth and renewal patterns

These properties are generated by a design approach centred on a set of 15 inclusivity principles which by ensuring the ecosystem is open to the greatest possible diversity of residents, invites a constant stream of new ideas, new perspectives, and new skills into the ecosystem, continually changing the range and scope of possibilities in the process.

By applying this design approach, Every One Every Day project designers engage residents in a unique co-production zone, in which contributions from the team, such as resources, stimulation ideas, and communications, are combined with contributions from residents, including their ideas, local connections, and project ingredients.

This approach means residents can self-direct to the opportunities most suitable and accessible to them, and can do so as contributors, makers, teachers, and learners, instead of users and consumers of services and products.

Many opportunities - wide variety

Introduce or accompany

100% open - no stigma

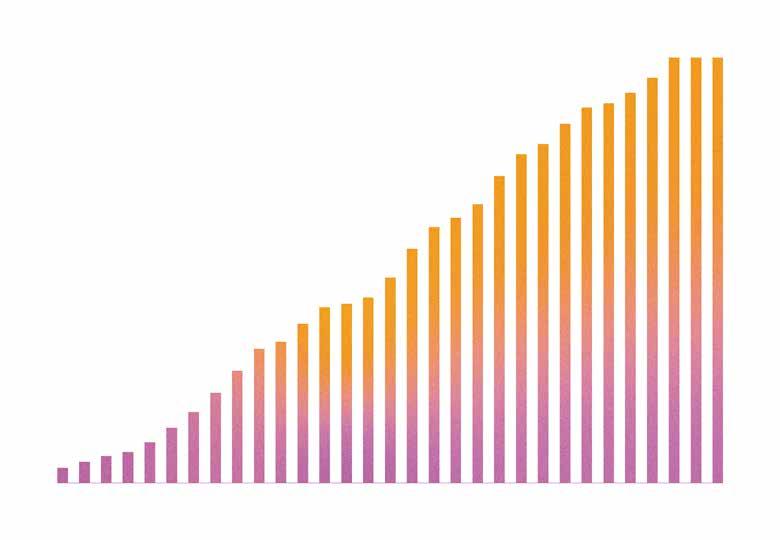

The ecosystem data in this report sets out the growth of the Participation Ecosystem from project inception to December 2022. In considering this section, it is important to note that data collection was heavily affected by the COVID-19 pandemic which effectively resulted in an estimated 18-month gap in participation data. As a consequence, the growth patterns in years three and four in particular should be treated with a degree of caution.

Against these key metrics a general pattern emerges up to March 2020 of linear growth in the size and scale of participation opportunities created by the project and a corresponding growth in the numbers of residents participating as members or nonmembers of Every One Every Day. This was in keeping with the theory of change underpinning the approach.

Once social restrictions were in place, in person participation became impossible and, while some forms of project development were amenable to being co-produced online, there was a predictable and inevitable impact on overall growth in the size of the ecosystem.

As can be clearly seen in the data shared here, it is now clear that the pandemic had two key impacts on ecosystem development. Firstly it effectively stalled growth for the periods in which social restrictions were in place. Secondly it significantly undermined the momentum which the project had built prior to March 2020. This latter effect can be seen in the much slower rate of growth in the post COVID-19 period than was the case before it.

From accounts shared as part of this research, residents described a complex interplay of multiple factors affecting their lives in the post pandemic world, particularly as this began to intersect with an emerging cost of living crisis in late 2021. These included changed family and personal priorities, challenging economic circumstances, anxiety about the future, and decreases in self-confidence.

When considered in the light of anecdotal evidence from team members which highlighted increased reluctance on the part of residents to travel across the borough to access participation opportunities, it is clear that resident behaviour changed markedly after the pandemic.

The effect of this was particularly marked at Everyone’s Warehouse, where it was noticeably more difficult to draw residents across the borough to access learning and other opportunities being developed there.

Conversely, the experience in the neighbourhood shops, particularly at the Heathway shop, which opened in August 2021, was that residents responded strongly and immediately to the opportunities available to them in a highly accessible location. The growth in registered and non-registered participants after August 2021 was notably driven by the new shops in Heathway and Marks Gate and provides further evidence of the importance of neighbourhood infrastructure to drive participation outcomes.

Aside from in person participation, the pandemic created an urgent need and an opportunity to develop online forms of participation capable of driving some participation outcomes. As described on page 73 the project deployed the Mighty Networks software to enable people to connect, share ideas, knowledge, and participate in activities online. While this was successful in ensuring that some residents were able to remain connected and involved, it was clear that the vast majority of members did not make the transition to online forms of participation.

Once in person participation became possible once again, the team de-prioritised online participation models in order to resume neighbourhood based work. This accounts for the small numbers of additional members of the online community in year five and beyond.

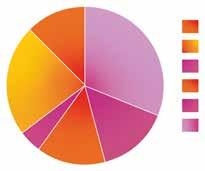

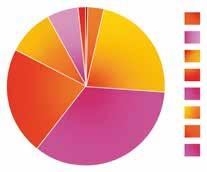

New (37.2%)

Returning (62.8%)

Visits by time of day

Morning (34.1%)

Afternoon (58.7%)

Evening (7.2%)

Planned vs walk-ins

Planned (30.2%)

Walk-ins (69.8%)

Between March and December 2022, Every One Every Day launched five programmes: Spring, Pre Summer, Summer, Pre-Autumn, and Autumn.

6914 Number of visitor to shops between March and December 2022

Programmes have historically been able to drive participation within the Every One Every Day spaces, as fluctuations in number of participants per week during programmes and in-between programmes demonstrate. Usually, the platform experiences less interactions with participants in between programmes and in periods when the team is working on developing new ones. Also, attendances are impacted by the schedule of events that usually have high attendance, school holidays, and the lengths of programmes itself, which usually vary in length, with the maximum length of the programmes mentioned above being 10 weeks (Summer Programme, 05 July 08 - Sept 2022) and the minimum 4 weeks (Autumn Programme 17 Nov - 15 Dec). Hence, differences in participation should be attributed to many reasons.

37% Percentage of participants who are visiting for the first time and 63% returning

Over a period of several months between March and December 2022, the Every One Every Day spaces were visited 9818 residents (including approximately 2800 children who attended with adults). Most of the people who attended were residents of the Barking and Dagenham Borough (89%); 37% were new participants, and 63% were returning. These figures confirm a trend, indicating that residents who are returning to the spaces to engage in activities are in greater numbers than those visiting the spaces for the first time. Regarding the time of the day people usually visit the shops, the vast majority prefer to visit in the afternoons and a smaller percentage in the mornings. Further to this, data shows that between March and December 2022 seven out of 10 people walked into the shop, while three out of 10 planned their visit ahead of time.

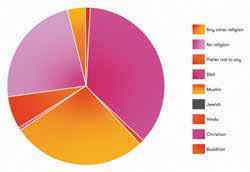

Overleaf is a summary of the equality data pertaining to Every One Every Day project participants, which has been gathered from a total of 151 people who agreed to share equality and diversity data - gather in a new sign-up form launched in June 2022 - out of a larger group of 806 participants who registered between June and December 2022.

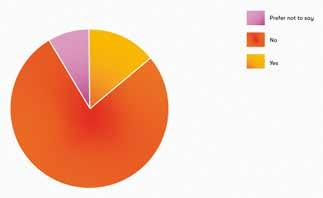

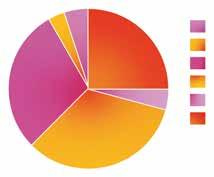

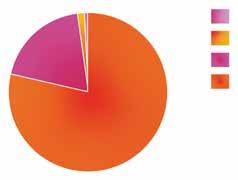

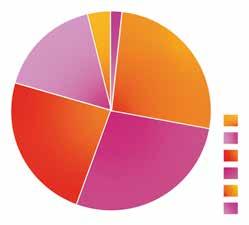

What is your sexual orientation?

Heterosexual (74.3%)

Homosexual (0.7%)

Lesbian (0.7%)

Bisexual (3.7%)

Other (4.4%)

to say (16.2%)

to say (8.6%)

Full-time (31.3%)

Part-time (14.8%)

Self-employed

Unemployed

Retired (4.5%)

to say (12.5%)

What gender you identify with?

Male (19.2%)

Female (78.8%)

Non-binary (1.3%)

to say (0.7%)

What is your religion or belief?

Christian (36%)

Muslim (27.5%)

Hindu (1.1%)

Buddhist (1.1%)

Sikh (0.5%) Jewish (0%)

Any other religion (3.7%)

No religion (23.3%)

Prefer not to say (6.9%)

What is your age group?

Under 16 (0.5%)

19-29 (22.5%)

30-39 (34.6%)

40-49 (22%)

50-59 (9.4%)

60-69 (6.3%)

Since the publication of Tools to Act there have been a number of key developments in relation to the platform which have altered the capacity of the participation system to simulate and respond to resident project ideas.

From the outset of the project the location of Every One Every Day spaces was governed by the aim to achieve borough wide coverage and the available project resources

This resulted in a project plan which sought to expand to five locations across the borough over the course of the project’s first three years, with the optimal team size in each space set at a minimum of two and a maximum of four depending on factors including footfall and project designer experience.

By February 2020 this had been achieved, with the project’s fifth shop opening in Marks Gate.

As described elsewhere in this report, following the COVID-19 period, patterns of resident participation changed in some fundamental ways substantially affecting comparative footfall across the shop locations.

At the same time, new opportunities emerged across the borough including through the project’s connections and partnerships with, amongst others, Be First, the council’s development and regeneration arm, Barking Riverside London, the developers of the Thames and Riverside area, and the GLA.

This saw the project move out of two spaces in Porter’s Avenue and Church Elm Lane and into new premises in the Heathway Shopping centre, at the same time adopting an approach to building new hubs for participation activity through partnership with new organisations.

The original project strategy always envisaged the development of hubs for participation approaches across the borough which could implement participation project models with reduced reliance on the shops and the team.

As lockdown took hold in March to June 2020, with the team unable to work directly with residents, this aspect of the strategy was accelerated. The aim was to develop a way for residents to stay connected through practical participation in their streets and neighbourhoods despite the restrictions in place.

The resulting approach - Tomorrow Today Streetswas developed in partnership with the IKEA Live Lagom programme, and launched in early June 2020. It comprised 24 project starter kits build on kit donated by IKEA, distributed to participating residents. Resident street teams were then supported to implement the projects themselves through a series of online and socially distanced workshops delivered by the neighbourhood team.

During late summer and autumn 2020 over 60 streets applied to implement projects in their neighbourhood and 12 eventually launched their Tomorrow Today Street in the spring of 2021 (the originally planned launch date of August 2020 had to be deferred due to new lockdown restrictions imposed at that time).

As described in Tools to Act, in 2018, Participatory City Foundation received a capital grant of £850,000 to build the practical making infrastructure as part of the participation system. This included the fit out and equipment of Everyone’s Warehouse, based at 47 Thames Road.

Whilst the core elements of the Warehouse were in place by March 2020, the pandemic delayed full completion of the capital spend. This unforeseen hiatus enabled the plan to be focussed to support Post COVID-19 recovery and specifically deploying remaining capital towards equipping a distributed making platform across the neighbourhood shops.

This approach saw a ‘Warehouse in a Box’ designed for each of the neighbourhood spaces, containing smaller scale equipment for cooking, fabric work, repair and plastics repurposing.

In Mark’s Gate, at the opposite end of the borough to the Warehouse, a more comprehensive set of workshop equipment has been installed, including woodworking and urban gardening.

In May 2020, Tessy Britton published Universal Basic Everything, a medium post which set out a post-COVID 19 vision for how our local economies and communities could produce the things we most need, in ways which do not harm our social and environmental ecosystems.

This thinking influenced a refocus of the making infrastructure to equip the borough with the means to develop and test circular economy models of local economic growth. A key element of this approach took the form of the UK’s first precious plastics machinery imported from the builders in Holland and installed in the messy making area of Every One’s Warehouse. This machinery creates the

Ripple Road

55 Ripple Road, IG11 7NT

Porters Avenue

5 Porters Avenue, RM10 5YS

Rose Lane

111 Rose Lane, RM6 5NR

Heathway Unit 11, The Mall, Heathway,

Church Elm Lane

116 Church Elm Lane, RM10 9RL

6 Thames

47 Thames Road, Barking, IG11 0HQ

capability for waste plastic to be ground up and pressed into sheets to be used on other machines such as laser cutters and CNC cutters, or to be pressed into moulds.

Coupled with the Maker In Residency programme this has seen approximately one ton of plastic repurposed, more than 100 sheets created, many prototype plastic products created, 40+ residents and 2 organisational members trained in the delivery of the process for shredding, pressing and moulding thermoplastics.