2 families, 1.5 homes

Concrete-free passive house proves sharing is caring

Scotland’s passive house plans Government urged not to flip flop

Aiming for zero

Bio-based passive house sets sights on net zero carbon

Smart money Is finance getting real on green building?

Emma Stone show puts passive house up in lights

Issue 47 £5.95 UK EDITION INSULATION | AIRTIGHTNESS | BUILDING SCIENCE | VENTILATION | GREEN MATERIALS

Hollywood moment

ALDES GROUP

INTRODUCING OUR NEW PRODUCT

Switch to daily mode or activate a program

View indoor air quality and get feedback

Going on Holiday? Activate holiday mode

View indoor air quality by day, week and month

Be informed when it’s time to change lters and order them online

Set ventilation modes by hour to hour on a weekly basis

DESIGNED FOR EASY INVERSION OF AIRFLOWS ON SITE

CONFIGURATION A CONFIGURATION B

MVHR FOR RESIDENTAL APPLICATIONS

Elevate your indoor experience with InspirAIR Top MVHR system, a connected marvel of innovation designed to prioritise air quality, performance, comfort, and user interaction.

The unit is delivered in configuration A.

To switch to B, simply reverse the filters, confirm the change in the remote control and connect the condensate to the corresponding side.The change takes less than 5 minutes!

Exhaust air (outdoor) Fresh air (outdoor)

2 | passivehouseplus.ie | issue 41 EDITOR’S LETTER PASSIVE HOUSE+ aereco.co.uk

Download from AVAILABLE ON

.

Publishers Temple Media Ltd PO Box 9688, Blackrock, Co. Dublin, Ireland t +353 (0)1 210 7513

e info@passivehouseplus.ie www.passivehouseplus.co.uk

Design

Editor Jeff Colley jeff@passivehouseplus.ie

Reporter John Hearne john@passivehouseplus.ie

Reporter Kate de Selincourt kate@passivehouseplus.ie

Reporter John Cradden cradden@passivehouseplus.ie

Reader Response / IT Dudley Colley dudley@passivehouseplus.ie

Accounts Oisin Hart oisin@passivehouseplus.ie

Art Director Lauren Colley lauren@passivehouseplus.ie

Aoife O’Hara aoife@evekudesign.com | evekudesign.com

Contributors

Lenny Antonelli journalist Toby Cambray Greengauge Building Energy Consultants

Jarek Gasiorek Smith Scott Mullan

Nick Grant Elemental Solutions

Marc Ó Riain doctor of architecture

Jason Walsh journalist

Peter Wilkinson Ecodesign Architecture

Print

GPS Colour Graphics www.gpscolour.co.uk | +44 (0) 28 9070 2020

Cover The Seed, Dundee

Photo by David Barbour

Publisher’s circulation statement: Passive House Plus (UK edition) has a print run of 9,000 copies, posted to architects, clients, contractors & engineers.

This includes the members of the Passivhaus Trust, the AECB & the Green Register of Construction Professionals, as well as thousands of key specifiers involved in current & forthcoming sustainable building projects.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in Passive House Plus are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publishers.

editor’s letter

Iwrote my first editor’s letter for the progenitor magazine to Passive House Plus, a sustainable building magazine called Construct Ireland (for a sustainable future) over 21 years ago, a fact I am struggling to process. It was, with hindsight, an act of madness, fuelled by youthful self-righteousness, to launch a sustainable building magazine in the first place. The Celtic Tiger was nearing its peak, construction standards were generally abominably poor, and I, frankly, didn’t know what I was talking about. I had no background in architecture or engineering.

But it is one thing to know nothing. It is another to know that you know nothing. Fortunately for me, while I was new to sustainable building, sustainable building was not new. I found a surprising number of pioneering academics, designers, builders and expert suppliers who were willing to humour my questions, and to help me know something more than nothing, and to publish increasingly detailed articles on the minutiae of sustainable building.

Occasionally I have cause to dig out an early article, to seek out a half-remembered detail or quote to back up a point I want to make. I approach the old article with a little apprehension, bearing in mind what I’ve subsequently learned about, say, the limitations of natural ventilation, or the risks of leaning too heavily on passive solar design. But I’m surprised to find that these limitations were often acknowledged. The reason? We have always tended, where we can, to try to talk not just to the building’s designer, but to the occupant.

Over the years we’ve amassed several hundred detailed case studies on buildings of all shapes, sizes and uses, built or retrofitted using a wide variety of materials. Occasionally, I’ll hear someone advocate for

something apparently unprecedented and new, and a long-forgotten project will come to mind. Like arguing for timber buildings of more than four storeys in Ireland, when we were writing about Navan Credit Union’s five-storey mass timber tower – timber lift shaft and all - as far back as 2005. Or like arguing for connecting heat pumps to shared ground loop collectors, when we published a social housing project in Tralee that did precisely this nearly 20 years ago.

While some of our older case studies still need to be archived in digital form, all of the hundreds of case studies we’ve published since Construct Ireland became Passive House Plus are available on passivehouseplus.co.uk. In the vast majority, these case studies include galleries of plans and construction details showing airtightness and thermal bridging detailing - drawings to consolidate the detailed descriptions we have tried to provide in each case study, in addition to telling the story of the project. We continue to add to this wealth of exemplars, and the projects in this issue are no exception – and a two-storey home on ground screws is a first for us. Because it is one thing to know something.

There is no doubt that many of the articles we publish now are considerably more detailed than articles we published in the past, especially with regard to case studies. Take the fact of including embodied carbon calculations. If a building has an apparent score of, say, 450 kg CO2e/m2, I want to know how that figure breaks down, and most importantly, I want to be confident that the calculation is accurate. Because it is one thing to know something. It is another to know that you know something.

Regards,

The editor

About Passive House Plus is an official partner magazine of The Association for Environment Conscious Building, The International Passive House Assocation and The Passivhaus Trust.

ph+ | editor’s letter | 3 PASSIVE HOUSE+ EDITOR’S LETTER

ISSUE 47

Case Studies

Ace of Herts

Big Picture

Sometimes reality is stranger than fiction. And sometimes strange but breathtaking fiction subverts reality. This issue we’re taking a break from our normal approach to Big Picture, with good reason: passive house playing a starring role in an extraordinary US TV show.

News

Scottish government urged to hold its nerve on passive policy; embodied carbon and zero emission targets adopted in new EPBD; group of Irish house builders turn to passive house; and retrofit imperative to take centre stage at AECB conference.

Comment

Near the peak of the Celtic Tiger – at a time when developers were throwing up often sub-standard homes at a record pace, one self-build project pointed to a different approach, writes Dr Marc O’Riain.

St Albans developer backs bio-based passive house plus Fancy owning an energy positive, timber-based passive house in one of the most desirable locations in England, without the hassle of having to build it yourself? A new three-house development nearing completion in Hertfordshire may be just the ticket.

Living proof

Extraordinary Dundee co-living home shows a new way

Sometimes a building comes along that does almost too much. Passive house stalwarts Kirsty Maguire Architects’ latest opus is an award-winning architectural, engineering, and sustainability feat –which asks questions not just about how we build, but how we live.

Airtight delight

Low carbon timber home gives high comfort and tiny bills

The proof in the pudding with a notionally low energy building is in the eating. Since moving into their new passive house a little under two years ago, the Murray family’s heating costs have been scarcely believable – in a home that also blitzes the embodied carbon targets in the RIAI 2030 Climate Challenge.

4 | passivehouseplus.co.uk | issue 47 CONTENTS PASSIVE HOUSE+

8 24 32 COVER STORY

CONTENTS

08 16 22 24

32 44

58

Insight

Pathway to passive or road to ruin?

As governments come under increasing pressure to make real and significant reductions in energy use and carbon emissions while tackling energy poverty, interest in passive house has never been higher. But short of expecting regulators to commit to certified passive house, is there a way of adopting the key principles that make passive house work?

Green shoots for green building?

Is big finance getting serious about sustainability?

While tokenistic or poorly conceived attempts at supporting the decarbonisation and greening of buildings still abound in the finance sector, there are signs of structural changes on the horizon - changes designed to unlock widespread change. But do those changes go far enough?

Practice makes passive

One architectural firm’s journey to passive house

For established architecture practices who haven’t worked on passive house projects before, the idea of engaging with unfamiliar approaches may seem daunting. Jarek Gasiorek of Smith Scott Mullan explains how, with the right approach, architects have nothing to be afraid of with passive house.

72 Marketplace

Keep up with the latest developments from some of the leading companies in sustainable building, including new product innovations, project updates and more.

In defense of fabric

As the grid gets greener and the case for heat pumps as a decarbonisation silver bullet becomes increasingly compelling, questions are starting to be asked about how far we need to go with retrofitting building fabric – or whether we need improve fabric at all. We ignore fabric at our peril, warns Toby Cambray.

ph+ | contents | 5 PASSIVE HOUSE+ CONTENTS ph+ | contents | 5 44 58 64

64 68

74

Big Picture

Sometimes reality is stranger than fiction. And sometimes strange but breathtaking fiction subverts reality. This issue we’re taking a break from our normal approach to Big Picture, with good reason: passive house playing a starring role in an extraordinary US TV show.

By Jeff Colley

It can be hard to switch off after a day wrestling with one of the myriad intricacies of sustainable building, so when you turn on the TV to see a two time Oscar-winning star nodding passionately on the thermal bridging properties of passive house, you could be forgiven for thinking you need a lie down. But put the smelling salts away for now. In November, the passive house standard really did get front and centre coverage in a major television show starring none other than Emma Stone. The Curse, a pitch-black comedy thriller series created by the critically ac-

claimed duo of Benny Safdie (Uncut Gems) and Nathan Fielder (Nathan for You), has been singled out for praise as “an incredible show” by no less than Oppenheimer director Christopher Nolan.

The show has a skin-crawlingly uncomfortable set up: a privileged white couple come into a disadvantaged community, and film a TV show on their efforts to renovate homes profitably but ethically, oblivious to the adverse impact of gentrification on locals, and to the patronising tone of their performative virtue.

The first episode features Whitney interviewing Hans Feist, president of the Passive House Society, a thinly veiled reference to Passive House Institute founder Prof. Wolf-

In the show Stone and Fielder play Whitney and Asher Seigel, a newly married couple co-starring in a home renovation TV show, Fliplanthropy. Whitney, attempting to atone for the slum landlord parents who bankroll her, sets up a development company with Asher to renovate homes to the passive house standard in Espanola – a real town in New Mexico that has one of the highest crime rates in America.

8 | passivehouseplus.co.uk | issue 47

gang Feist. “What you end up with is a home that’s kind of like a Thermos,” says the DoppelFeist. “It maintains a consistent and comfortable temperature inside, while the air is kept healthy using heat recovery ventilation.”

Shortly after, Asher falls victim to the titular curse of the show’s name. While Asher’s crew are filming in the car park outside a discount store, a little girl street vendor, Nala, tries to sell Asher a can of Sprite. With the cameras rolling, Asher reluctantly gives the girl the only cash he has: a $100 bill. When the cameras stop, he takes the money back from her, and promises to come back with change, but the girl refuses and curses him. Asher’s creeping anxiety over the apparent curse hangs over the rest of the series, and the question of whether passive house is somehow involved in the curse even surfaces.

Unfortunately some of the references to passive house in the show don’t ring true, such as the assertion that passive houses take a long time to heat up if a door is left open, that certification is revoked if air conditioning is installed, and the related suggestion that passive houses in hot climates like New Mexico can be uncomfortably hot. In reality, air conditioning may be a feature of a passive house in Espanola – though the house should require a tiny amount of AC to maintain comfortable temperatures. There is also the implication that passive houses are a premium product for privileged greenies,

BIG PICTURE THE CURSE ph+ | the curse big picture | 9

Photos: John Paul Lopez, Richard Foreman Jr. and Katie Byron/A24/Paramount+ with Showtime

in spite of a growing number of examples of passive house schemes transforming the lives of low-income households, in some cases for little extra construction cost compared to regular new build or deep renovation.

It’s also worth noting the particular aesthetic choices Whitney made with house design. The homes are mirror-clad, inspired by the work of US artist Doug Aitken, though Whitney puts up a stout defence for this design flourish. “My homes are reflecting the local community, and his reflect nature,” she says – though tell that to the bird that met its maker in one episode after flying into the walls.

But why the passive house standard? Passive House Plus reached out to the show’s production designer Katie Byron to find out more.

“Nathan Fielder and Benny Safdie wrote passive house renovations into the show before I started,” says Byron. The standard

was picked to reflect a kind of aspirational sustainability-focused home and garden TV show Whitney and Asher were trying to get off the ground – albeit passive house through a slightly warped lens.

“Nathan is very careful with wanting to be as authentic as possible with everything in his work, so he really wanted to carefully research and understand the strategy and approach to building a passive home,” says Byron. “We watched every YouTube and documentary we could find on the subject.”

While most of the series was filmed on location in Espanola, no actual renovations took place. “I wish I could say that we did,” says Byron. “We built all of our facades. Parts of the interiors were built on a stage in Albuquerque and parts were shot on location in Espanola.”

It may be foolish for passive house advocates to get too caught up in picking holes in how passive house is represented in the show – after all, it’s a work of fiction, and it could be argued that the oxygen of publicity for passive house outweighs the risk of the show promoting misconceptions.

A case in point is how the airtightness of the homes is presented, and without giving away any spoilers, its role in the show’s finale. “All of our doors were custom made with triple locking systems and three seals between the door and the frame,” says Byron. “Nathan really wanted to make sure they felt like there was a suction feeling if you'd operate either. I don't want to give away the ending, but the idea of creating this perfectly sealed environment was an important part of the story.”

At one point when a window is opened, there’s an audible gush of air – as if a tyre has been punctured. When a prospective buyer complains about the house being too

warm, Whitney explains this away. “We did open the front door when we all came in,” she says. “And let in some air,” adds Asher. “It takes a little while for the temperature to equalise,” says Whitney. The visibly melting buyer asks how long that usually takes. “Five to seven hours, probably,” says Asher. “But once you get that temperature, you want to keep the doors and windows shut, because you got it locked in – it’s a nice 71-72 F [22 C]”. “Don’t open any doors or windows,” the buyer says. “Unless you want it to get hot or cold,” laughs Asher. “Like a Thermos,” says the buyer. “Or a prison”, says his partner.

Sigh. This, frankly, is wildly inaccurate, and it’s probably the point where you should remember that it’s a fictional show rather than a documentary, and that passive house is being used to serve the needs of the story. Brooklyn-based passive house stalwart Ken Levenson, executive director of the Passive House Network offers some perspective.

“I find it helpful to remind myself that this show is about the human condition and not passive house,” he writes, in an excellent review of the show on the PHN website.

“Clad in mirrors (à la Doug Aitken), passive house is a misunderstood alien, and the show’s producers treat it as such, ultimately unexplained and unexplored, because, after all, they have a story to tell. This isn’t surprising or (very) upsetting. I wouldn’t expect it to be a passive house explainer either, but as they tend to misrepresent passive house to get the desired effect, it’s more gags with the building.”

As to the condition of the particular humans at the centre of the story, the Siegels are a curious mix. “The newlyweds are maniacally insecure, loathsome, self-obsessed, pampered, and lifestyle-eco-consumer-so-

THE CURSE BIG PICTURE 10 | passivehouseplus.co.uk | issue 47

ph+ | the curse big picture | 11

THE CURSE BIG PICTURE 12 | passivehouseplus.co.uk | issue 47

BIG PICTURE THE CURSE ph+ | the curse big picture | 13

THE CURSE BIG PICTURE 14 | passivehouseplus.co.uk | issue 47

cial-art-entrepreneur icky,” says Levenson. “Their arrogance / insecurity is imposed on others (and us) while trapping them in rabbit holes of good intentions and unintended consequences.”

This ickiness is evident in Katie Byron’s production design, which scream of Whitney straining to be right-on and green, but oblivious to her own privilege. To be fair to Whitney, there are more egregious examples. (For an insight into the unsolicited awfulness a green building magazine publisher encounters: on the day I emailed questions to Byron, a doozy popped into my inbox with the subject line: "Solving the Environmental Stigma of Private Jet Travel: Interview with Hydrogen Powered Jet Pioneer".) What’s more, the construction industry is still replete with jarringly obvious examples of tokenistic or thoroughly empty attempts at sustainability – such as overly large houses of middling thermal performance specs and high embodied carbon materials, but with a visual green feature like organic paint, a solar array, or recycled / upcycled furniture and finishes. Whitney’s approach seems different. Whether by luck or design, she’s latched on to a science-seem based approach to sustainable building in passive house, and what appear to be modestly sized homes, at least in an American context. “Whitney is complex in her struggle to do the right thing,” says Byron. “I think deep down, she wants validation. Deep down she wants people to think she's a good person. She ultimately

wants redemption. So much so, that she'll be willing to take ethical missteps to make people think she's good. The idea of tearing down old and beautiful pueblo adobe homes to build her own version of a passive home obviously has environmental impact. They also have a food delivery subscription with lots of plastic and waste when they could be growing their own food or shopping at the local markets. I think Whitney is a bit confused as to where she draws the line for conservation.”

But if Whitney has a particular blind spot, it’s the inability to recognise how her own privilege pollutes her green efforts. “Her designs also are expensive which feels problematic to her goal to improve environmental issues,” says Byron. “The only people who can afford these homes will be high income earners from out of state. It's not very democratic or inclusive, but because optics are so important to her, she'd rather have a home that had high end finishes on TV than show homes that local people could actually afford. I think she desperately wants to [have] both but doesn't realize that the two are diametrically opposed ideas. It's a struggle that seems quite universal when it comes to climate change.”

While the Siegels might not be the ambassadors the passive house standard needs, and there are some problematic creative liberties taken in The Curse in terms of how passive houses look and perform, it’s important to recognise the show for what it is: an excep-

tional and important work. And anoraky concerns aside, Oscar Wilde’s words seem strangely apt: “There is only one thing in life worse than being talked about, and that is not being talked about.”

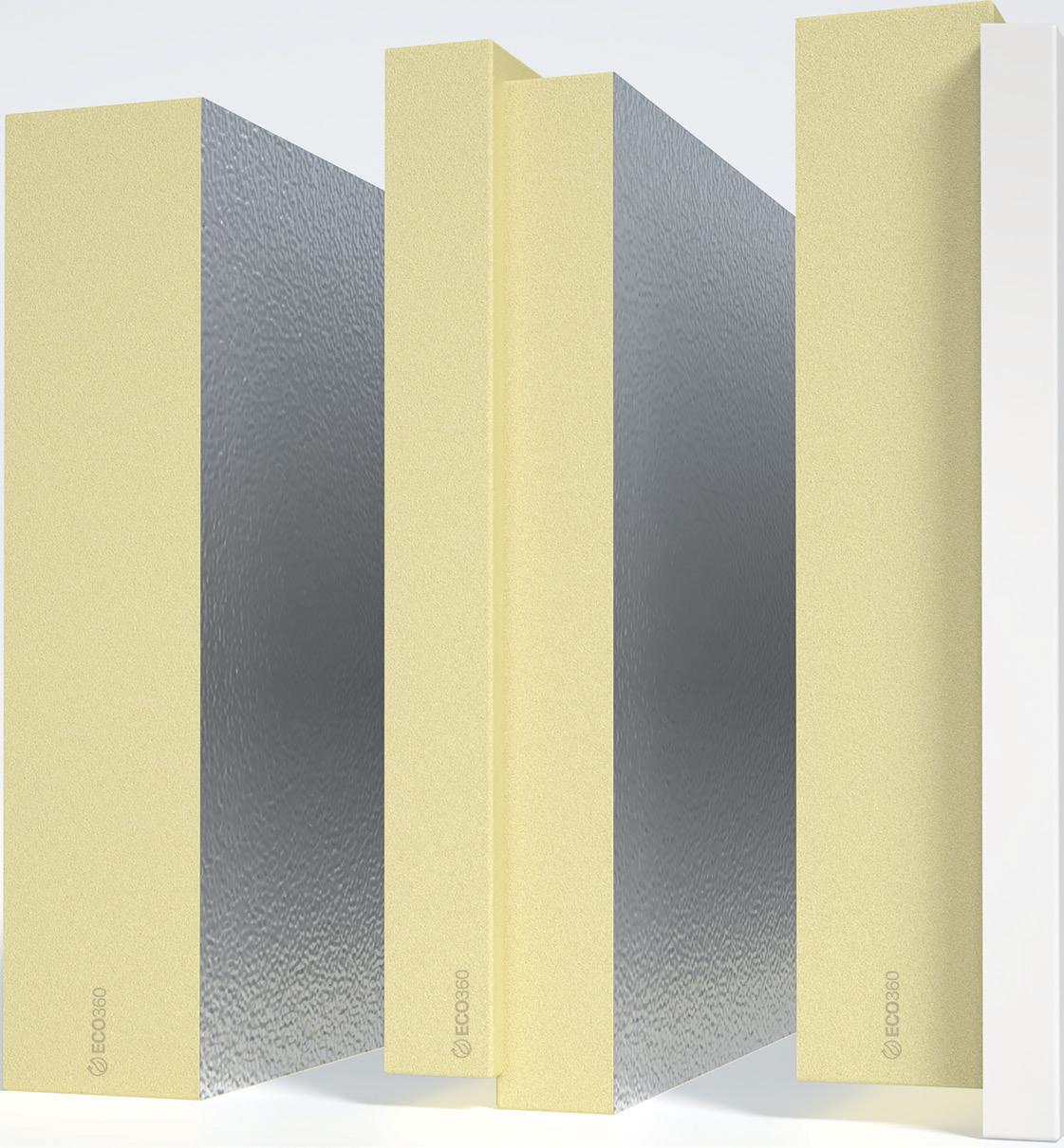

The piece de resistance for Ken Levenson was footage of Whitney explaining passive house insulation levels in a wall mock-up. “Who could not love this shot?” he says. “At the end of episode one, Whitney says, in a voice-over, ‘I can’t think of a better place to start our passive house revolution.’ Forgive me, but all I can hear is Emma Stone talking about a passive house revolution. Is it me?”

To read Ken Levenson’s marvellous review of The Curse, visit:

https://tinyurl.com/CurseReview

BIG PICTURE THE CURSE ph+ | the curse big picture | 15

Scottish government urged to hold its nerve on passive policy

Passivhaus Trust responds to Homes for Scotland's call to 'pause and review' Scottish Passivhaus equivalent plans.

The Passivhaus Trust is calling on the Scottish government to continue its plans for newbuild housing that will cut heating demand in Scottish homes by almost 80 per cent, and hold fast against housebuilder calls to ‘pause and review’ its proposed Scottish passive house equivalent policy.

The policy, which is due to be adopted as legislation in December, has been developed in response to strong popular support from the Scottish Climate Assembly.

Homes for Scotland has issued its call to rethink the Scottish passive house equivalent policy in response to the housing availability crisis and the recent announcement that the Scottish government is dropping its 2030 climate targets.

The Passivhaus Trust contends that improving energy efficiency standards will not adversely affect Scotland’s housing shortage, pointing out that higher standards were not found to be a constraint on housing supply in two recent UK government studies. At the same time, the trust acknowledges the difficulties currently being experienced within the Scottish construction industry – which is why it is calling for a transition period for the policy implementation to allow the industry to prepare and upskill.

While the Passivhaus Trust is disappointed by the recent announcement that the Scottish government has dropped its 2030 climate targets, it argues that this is no reason to jettison its passive house policy. The trust points out that a passive house equivalent would deliver more than reduced carbon emissions, tackling the cost-of-living crisis, reducing spending on expanding the grid infrastructure, and saving the NHS money. The Passivhaus Trust estimates that the additional costs of building to passive house are 4-8 per cent, which can come down further with economies of scale and familiarity. Building to the passive house levels of performance would reduce heating demand in homes by up to 79 per cent compared to current Scottish building regulations.

Alex Rowley MSP, whose Member’s Bill forms the basis of the legislation, commented: “Building a passive house is the epitome of a spend-to-save approach. By investing now, we save both financially and environmentally over the term of the project. It will benefit Scottish households by radically reducing energy bills, addressing fuel poverty, and delivering healthy mould-free homes.”

Route map

The Passivhaus Trust has also responded to Homes for Scotland's concerns regarding the claimed "lack of a clear and co-ordinated delivery route map.”

Passivhaus Trust research and policy director Sarah Lewis said: “Drawing on the leading international low energy building standard, complete with design tools, skills training, qualifications, and a rapidly growing supply chain, offers the perfect clear and coordinated delivery route map. It is hard to think of another solution that has been more robustly tested. In our view, setting this as the ultimate goal, with a suitable transition period, should offer the perfect route map for housebuilders to work towards.”

Passivhaus Trust CEO Jon Bootland said: “In developing the Scottish passive house equivalent policy the Scottish government has shown global leadership. We urge the Scottish government to hold its nerve and not abandon this ground-breaking policy. A Scottish passive house equivalent would deliver so many benefits to the people of Scotland in terms of radically reduced energy bills, improved health outcomes, and improved grid capacity through reduced peak demand.

“We understand that it is challenging for housebuilders to change their practices but would argue that passive house is not the big leap they might be imagining. We have seen the Scottish construction sector rise to the challenge of building to passive house in the schools sector – with thirty-five passive house schools currently underway in Scotland. We

would urge Homes for Scotland members to work with us to develop solutions. We have identified key recommendations for how the policy could be implemented in Scotland and have emphasised the need for a transition period to allow the industry to upskill and prepare.” •

16 | passivehouseplus.co.uk | issue 47 NEWS PASSIVE HOUSE+

NEWS

(above) Passivhaus Trust research and policy director Sarah Lewis says that when it comes to energy performance it is “hard to think of another solution that has been more robustly tested” than the passive house standard.

Group of Irish house builders turn to passive house

Anumber of Ireland’s largest house builders are turning to the passive house standard, to meet the need for proven approaches to delivering high performance sustainable buildings.

Freshly elected Passive House Association of Ireland (PHAI) chair Caroline Ashe revealed details of the developer group at the ZEB Summit in the RDS on 22 February.

The group, which includes Ballymore Group, Cairn Homes, D/Res Properties, Durkan Residential, Fraser Millar, Kelland Homes, OCC Construction, Park Developments and Setanta Construction, was brought together by passive house experts MosArt.

Speaking to Passive House Plus, MosArt director Tomas O’Leary said: “The developer group emerged after it became clear that several different entities were investigating – in isolation – the potential application of passive house to their portfolio. Rather than everyone re-inventing the wheel, it would surely make sense to collaborate and share real-world experiences.”

The group first met for a knowledge-sharing session organised by MosArt’s director of growth and innovation, Stephen Donoghue, at the Maldron Hotel in Newland’s Cross on Bloom’s Day, 16 June 2023 – a date which may come to represent the anniversary of the passive house standard truly blooming in Ireland.

According to O’Leary, the fact that some of the developers in the room, such as Durkan Residential, Fraser Millar and Setanta Construction, already had experience of building passive helped up the ante. “I think it’s fair to say that the developers who had achieved passive house already lay down a challenge to the bigger players to give passive house a go, [saying] ‘If we can do it, so can you’,” said O’Leary.

Contrary to some of the most common arguments against adopting passive house, cost didn’t trouble the group. “I recall a general agreement in the room that cost of going passive was not a major concern for any of the attendees,” said O’Leary. “It was more about delivering and achieving quality issues than loading on extra cost.”

O’Leary recalls pinching himself when the meeting ended. “I sat into the car afterwards with Stephen Donoghue, turned to him and said, “did that really just happen?” Having spent two decades of my career promoting, educating and drip-delivering passive house in Ireland, it looked like the dam was about to burst and the science-based approach to high performance housing was finally going mainstream.”

Reflecting on the Bloom’s Day meeting, Cairn’s head of sustainable construction and reporting, Stephen O’Shea, emphasised the role the developers who had already built passive played. “John Carrigan of Fraser Millar in particular spoke very well.” he said.

The meeting was followed up with a site visit to Fraser Millar’s Lancaster Park scheme in Belfast on 24 July and Durkan Residential’s Egremont scheme in Killiney in October. “At that stage it was pretty much agreed that we would step out of the shadows at the upcoming ZEB Summit.” said O’Shea.

Perhaps the surest sign of developer engagement on passive house turning into tangible results is Cairn’s first passive house development, a 590-unit apartment scheme at Pipers Square, Charlestown, which is currently on site. “For us, this initiative delivers two key benefits; a dramatic reduction in the building’s carbon footprint, and significant benefits for the building’s owners and residents,” the company said.

It looked like the dam was about to burst and the science-based approach to high performance housing was finally going mainstream.

As a large company, Cairn is mandated to report on emissions in several defined scopes under the Sustainable Financial Disclosure Regulations (SFDR), including scope 1 (emissions from sources owned by the company), scope 2 (emissions indirectly caused by the company’s energy use) and scope 3 (all other emissions indirectly caused by the company up and down its value chain). Speaking at the ZEB Summit, O’Shea said the decision to go passive would play a key role in helping the company reduce its scope three emissions, by reducing energy-related emissions from the users of the buildings it builds.

In a statement to Passive House Plus, Ballymore said: "Ballymore is thrilled to participate in the passive house movement here in Ireland. We see this as the modern benchmark in home performance. MosArt has played a key role in our passive housing journey to date, pushing our design and our supply chain to a standard that far exceeds norms of the industry.” •

ph+ | news | 17 PASSIVE HOUSE+ NEWS

(above left) Pictured at Durkan Residential’s Egremont passive house scheme in Killiney are MosArt director Stephen Donoghue and (back row, l-r) Ballymore’s senior development manager Anthony Coakley and sustainability designer Charlie Conlan; Fraser Millar director John Carrigan; Setanta director Mark Gribbin; Durkan Residential director Barry Durkan, and Cairn head of sustainable construction Stephen O’Shea. (above right) Newly elected PHAI chair Caroline Ashe announcing the new developer group at the ZEB Summit on 22 February.

High performance buildings essential for climate and quality of life

The en masse global shift to high performance buildings is essential to meeting the climate challenge and improving quality of life around the world, an international conference has heard.

With the theme “Metrics of Success: Securing Real Progress Toward Sustainable Buildings”, the second annual summit of Enniscorthy Forum’s Buildings Action Coalition (BAC) brought together an international mix of policy experts, building practitioners and officials from both sides of the Atlantic to explore how to decarbonize buildings and create more resilient, liveable communities.

Held in Enniscorthy, Co Wexford on 8-10 April, the summit was designed to advance the agenda of the Buildings and Climate Global Forum, led by France and the UN Environment Programme in March 2024 in Paris, and its Chaillot Declaration.

In his opening remarks, Ireland’s housing minister Darragh O’Brien said: “The overall objective of the Enniscorthy Forum’s Buildings Action Coalition, to achieve high performance in buildings and the built environment rapidly and at global scale, strikes at the heart of the critical challenges we face. It is essential that all these efforts lead to improved quality of life –improved health, better economic, social, and environmental resilience, social justice, better levels of comfort, affordability, indoor and broader urban air quality. We are pleased to see Ireland take a leading role in advancing these principles globally.”

150 participants joined the summit either in person or online to consider issues and opportunities related to buildings and the built environment. The summit set forth a range of policies and approaches that are being deployed to advance high performance buildings and insisted on the need for cross-cutting education and training. Notably, leading universities presented their vision for educating the next-generation professionals needed for sustainability in buildings, and international centres of excellence shared the training approaches they apply to im-

prove the industrial ecosystems that deliver high performance in buildings.

The summit featured case studies in collaborative leadership from Brussels and Washington DC as capital cities, and from Pittsburgh and Glasgow as cities delivering quality of life in a post-industrial context.

Two specific topics, using the integration of buildings and grids as a bridge to the future and addressing the growing energy demands of data centres, were the subject of much discussion. Integrating buildings and grids efficiently offers improved energy services for buildings, an important source of grid stability, and an opportunity to integrate intermittent renewables into the energy mix.

One of the key objectives under the vision of the Buildings Action Coalition is to change construction industry culture. Enniscorthy Forum is undertaking to achieve that shift in culture through its networks of academia and centres of excellence, and engagement with youth organisations and use of the creative and performing arts to both teach and inspire young people on the principles of high performance. The summit launched a fifth pillar of the Buildings Action Coalition, the Youth Movement and Social Action League (YSL), and the Enniscorthy Forum signed letters of intent with the Youth Democracy Movement (YDM), the Union of Students in Ireland (USI), the Organising Bureau of European School Student Unions (OBESSU), the Commonwealth Students Association (CSA), and the Irish Second-Level Students Union (ISSU).

In the closing segment of the summit, students from New York City working with Passive House for Everyone! and the city of New York presented an inspiring set of art, music, and demonstration projects, notably an ice cream challenge that was conceived to minimize melting by proper design.

Delegates visited Ireland’s first passive house office building, Senan House, for a presentation

of technology innovations from Trinity College Dublin’s Innovation and Entrepreneurship Centre, before signing in new members of BAC at Enniscorthy Castle. In addition to the letters of intent signed with the YSL, new members included Wicklow-based passive house stalwarts MosArt and Bulgarian energy efficiency centre EnEffect.

Closing the event, Enniscorthy Forum CEO Barbara-Anne Murphy said: “Getting buildings and the built environment right is the one thing that can deliver important, impactful results in a relevant timeframe. We don’t need to wait for nuclear fusion – we have the technology, we have the capital, and we have the know-how to make a real difference in the performance of buildings.”

The non-profit Enniscorthy Forum was established to support the United Nations’ sustainable development agenda, focusing on buildings and the built environment, energy, diplomacy, health, and education. The forum and its partners work in collaboration with UNEP to promote and demonstrate the transformative benefits of high-performance buildings and to ensure take-up of best practice methods in planning, design, and construction across the world.

The Building Action Coalition will continue to press on the range of its activities and initiatives in the areas of best practice dissemination, communication and deployment of high-performance principles, education, training, and research, and development of case studies as proofs of concept. Coalition members provide hour-long webinars on the second Wednesday of each month to explore and explain novel approaches they have developed. The first regional summit is being organized with a BAC member, The Energy Coalition. It will take place in Autumn 2024 in Los Angeles, California. The third BAC summit will take place in summer 2025. • (above) Members of the Buildings Action Coalition pictured on the roof of Enniscorthy Castle at a signing ceremony of new members.

18 | passivehouseplus.co.uk | issue 47 NEWS PASSIVE HOUSE+

Retrofit imperative to take centre stage at AECB conference

‘Retrofit Now’ will be the theme for the Association of Environment Conscious Building (AECB)’s annual conference on 27 September.

Hosted at the National Self Build & Renovation Centre (NSBRC) in Swindon, the conference will show how the AECB’s CarbonLite suite of standards are gaining considerable traction in new build and retrofit projects.

The conference will focus on practical solutions to decarbonising buildings, with a particular emphasis on approaches which offer most potential to deliver low energy, healthy buildings at scale, while minimising the use of precious resources and impact on the environment.

Headline speakers for the event include National Retrofit Hub director Rachael Owens, BDP architect Ed Dymock, Spring Design AECB CarbonLite certifiers Jonathan Davies and Jaime Moya.

Owens’s talk will focus on the future of retrofit and the retrofit landscape of today, drawing from her work at the National Retrofit Hub, a non-profit collaborative organisation focusing on enabling the local delivery of retrofit at scale. Owens is also the head of sustainability at Buckley Gray Yeoman, a practice that champions the adaptive reuse of existing buildings, and was named a RIBA Journal Rising Star for her work in practice to communicate sustainable design and within the Architects Climate Action Network to campaign for the regulation of embodied carbon emissions. A WELL-accredited professional, Rachael joined the RIBA Stirling Prize jury in 2023 as the sustainability expert.

Meanwhile Ed Dymock’s talk will focus on Prospecthill, a 15-storey tower block in Greenock owned by social housing provider River Clyde Homes, who manage over 6,000 homes in the Inverclyde area. The project is the largest building to be retrofitted to the AECB’s CarbonLite standard to date.

Davies and Moya – both of whom are certified passive house designers and AECB approved CarbonLite certifiers, will update delegated on efforts to lobby for regulatory change to new build energy standards for social housing in Wales – efforts which have resulted in the acceptance by Welsh Government of the CarbonLite New Build standard for social housing grant funding in Wales.

For information on tickets, visit www.aecb.net, and for sponsorship opportunities email conference@aecb.net. •

speak at the AECB Conference 2024 on 27 September.

Winners announced for 2024 ASBP Awards

Abio-based passive house build, tool wash system, digital construction data tools, and a biobased modular build system were among the winners of the sixth annual awards of the Alliance for Sustainable Building Products (ASBP).

The awards were presented at the ASBP’s 8th annual conference on 29 February in London, which focussed on biodiversity, forestry, and health & wellbeing. All attendees had the opportunity to vote for their favourite entry in the project, product and initiative categories of the awards, following short presentations from the nine finalists.

Winners were announced under three categories, which in each case included a judges’ award decided following a series of site visits and interviews, and a people’s prize. The inaugural winner of a new award, created in memory of late, great green building pioneer Neil May, who helped set up ASBP and many other sustainability organisations, was presented to Richard Oxley.

Bio-based passive house project Goldfinch Create & Play, designed by SEB + FIN Architects, won the judge’s award in the project category, with Houlton Secondary School by van Heyningen and Haward Architects winning the people’s prize, and dRMM’s East Ham Old Fire Station a runner-up.

In the product category the judge’s award went to Geosentinel’s Washbox, a tool wash system which can be used by painters, plasterers, blocklayers, tilers and any trades person to wash their tools in recycled water. The people’s prize went to Natural Building Systems’ Adept integrated and demountable biobased modular build system. The runner up was EMR’s Reusable Steel, which integrates steel recovery services with low carbon new steel supply.

In the initiative category the judge’s award went to Grosvenor’s supplier mentorship programme, while the people’s choice award went to Qflow’s decarbonising construction digital tools, with Preoptima taking the runner up slot with their early stage carbon optioneering for significant emissions avoidance.

Launched in 2018 by the Alliance for Sustainable Building Products, the awards have provided a platform for industry leaders, innovators and radical thinkers to showcase their exemplar building projects, problem solving products and transformative ideas. To date, over seventy-five applicants have been shortlisted, with thirty winners being awarded a coveted ASBP Award trophy for accelerating the pace of change in industry. Submissions were judged by members of the ASBP board and executive team, who have expertise from across the construction industry, and assessed against the ASBP’s “Six Pillars of Sustainable Construction.”

The awards were sponsored and supported by Lime Green Products, Lumybel, Ecology Building Society, natureplus, Natural Building Store and Futurebuild.

The ASBP was launched at an event at the Palace of Westminster in November 2011 and now has over 140 members.

Please see www.asbp.org.uk for more information. •

(above) The 2024 ASBP Awards were held at an evening reception at the ASBP Healthy Buildings Conference & Expo in London.

ph+ | news | 19 PASSIVE HOUSE+ NEWS

(above) National Retrofit Hub director Rachael Owens and BDP architect Ed Dymock will

Embodied carbon and zero emission targets adopted in new EPBD

All new homes in Europe must meet binding embodied carbon reduction targets and produce zero on site emissions by 2030, due to changes led by Irish Green Party MEP Ciarán Cuffe.

Adopted on 12 April, the new recast of the Energy Performance of Buildings Directive will also ratchet up requirements to retrofit Europe’s existing building stock, including mandatory minimum energy performance standards and binding retrofit targets for non-domestic buildings, and requirements for each country to reduce the average primary energy of their residential buildings – along with requirements for sustainable mobility including cycling and EV charging infrastructure.

The principal architect of the new directive, Green Party MEP for Dublin Ciarán Cuffe said: “This is an important step on the path to decarbonising buildings in the EU. In the coming years it will reduce energy bills, reduce our greenhouse gas emissions and allow people to live in cleaner, greener, healthier homes.”

With buildings responsible for around 40 per cent of the EU's energy consumption and 35 per cent of energy-related greenhouse gas emissions, the EU’s intention is expressed at the start of the directive’s first article, setting the context of “achieving a zero-emission building stock by 2050.”

According to Cuffe, the European Parliament’s special rapporteur on the recast directive, the onus in the climate fight is on taking decisive action now. The directive was adopted just before European elections which may significantly impact the direction of Europe’s decarbonisation efforts. “This is the decade of change,” he told Passive House Plus. “It’s important that we have strong green representation in Europe in the coming years as we ramp

up our efforts on tackling climate change.

Embodied carbon in, and ZEB instead of NZEB Even in sustainable building circles, efforts to calculate and reduce embodied carbon of buildings have historically been few and far between, but provisions in the directive are set to bring embodied carbon from obscurity to ubiquity in a handful of years. The issue is addressed in the directive term "life cycle global warming potential" (GWP), which includes emissions of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases from both operational energy and embodied carbon across the building’s notional lifespan.

From 2028 the requirement to calculate life cycle GWP will apply to all new buildings over 1,000 m2, extending to all new buildings from 2030. In addition, member states will be required to introduce limit values for total cumulative life-cycle GWP of all new buildings, with targets for new buildings from 2030, followed by a “progressive downward trend” for different building typologies.

The directive also ups the ante on efforts to tackle operational energy demand, with the current nearly zero energy building standard being superceded by a new zero emission building (ZEB) requirement, defined as a building with “very low energy demand, zero on-site carbon emissions from fossil fuels and zero or a very low amount of operational greenhouse gas emissions.” The directive states that all new buildings must be ZEBs by 2030, and existing buildings should be transformed into ZEBs by 2050.

To prepare for that goal, each member state will adopt its own national trajectory to reduce the average primary energy use of residential buildings, by 16 per cent by 2030 and 20-22 per cent by 2035. For non-residential buildings,

they will need to renovate the worst-performing 16 per cent of buildings by 2030 and the worst-performing 26 per cent of buildings by 2033, with certain exempted building types.

The directive also requires member states to support citizens in their efforts to improve their homes, including a requirement for the establishment of one-stop shops for independent advice on building renovation, with provisions on public and private financing to make renovation more affordable and feasible.

The commission raised concerns as far ago as 2016 about nearly zero energy buildings being undermined by energy performance gaps and poor indoor environmental quality, and the new recast includes measures to prevent a repeat. Changes in the new directive are set to require an overhaul of national energy performance calculation methodologies such as Ireland’s Dwelling Energy Assessment Procedure (DEAP) and Non-Domestic Energy Assessment Procedure (NEAP).

The directive states that calculation methodologies “should ensure the representation of actual operating conditions and enable the use of metered energy to verify correctness and for comparability”, instructs member states to set energy performance requirements that “take account of optimal indoor environmental quality, in order to avoid possible negative effects such as inadequate ventilation” and advises member states to “focus on measures which avoid overheating”. •

(above) Passive House Plus editor Jeff Colley chaired a joint IGBC/European Parliament panel discussion on the recast EPBD in Dublin on 15 March.

20 | passivehouseplus.co.uk | issue 47 NEWS PASSIVE HOUSE+

Pictured are (l-r) Jeff Colley; IGBC CEO Pat Barry; IGBC chair and Dublin City Architect Ali Grehan; Dublin MEP Ciarán Cuffe; and Arup director Oonagh Reid.

Be part of something bigger

The Association for Environment Conscious Building (AECB) is an independent, not-for-profit organisation run for its members.

Our vision is to create a world in which everyone in the building industry contributes positively to human and planetary health. We work with our members to inspire, develop and share sustainable and environmentally responsible building practice.

Our Standards are a key pillar of the deployment of environmentally responsible building practices and the creation of sustainable low energy, low carbon buildings.

and

the

ph+ | news | 21

www.aecb.net

you

webinar

ongoing throughout

year

gain knowledge

insight directly

experts. Webinars Keep up to date with all the latest news in the sustainable building world with our free newsletter. Newsletter Established in 1989, the AECB works to increase awareness within the construction industry and has built up a vast library of technical articles and media resources. Knowledgebase The AECB CarbonLite™ Training Centre offers cutting edge training for the buildings sector, plus expert written, well established courses in Retrofit and PHPP training. AECB CarbonLite™ Our online shop provides software packages such as the Passive House Planning Package, design PH, AECB PHribbon and the AECB Carbon Calculator. Software For more information visit our website, and don’t forget to follow us too! Be a part of the UK’s largest sustainable building community, a vibrant network to feel part of through collaboration, research, and best practice. Membership

Bringing

a

programme

the

to

from

Out of the Blue A Passive Revolution

Near the peak of the Celtic Tiger – at a time when developers were throwing up often sub-standard homes at a record pace, one self-build project pointed to a different approach, writes Dr Marc Ó Riain

Over the past seven years, as I've penned this series of articles, I have documented the unfolding progress of solar housing, renewable technologies, building technology, and the emergence of environmental policies. Our present construction landscape bears the imprint of a rich tapestry woven by pioneers, researchers, authors, legislators, and architects. Today, both in Ireland and the UK, we stand capable of constructing and renovating A-rated, energy-positive, and passive standard houses.

At the dawn of the new century, the Kyoto Protocol had just been inked in 1998, gradually integrating into the EU Directive on the Energy Performance of Buildings by 2002. While the UK had responded to the first oil crisis in 1974 with the introduction of building energy standards, Ireland, in contrast, only adopted Part L energy conservation in buildings regulations in 1997. These standards, mirroring draft elective standards from 1974, marked a significant statutory stride but demonstrated little environmental ambition. By 2002, both nations were refining elemental standards for dwellings, with Ireland introducing Building Energy Ratings (BERs) via the DEAP calculation method, and the UK employing the SAP method. The industry transitioned from elemental performance to assessing the overall performance and energy consumption of fixed loads in buildings. The DEAP & SAP methodologies evolved from the pioneering energy calculation methods showcased at Energy World

in Milton Keynes in 1985. BER certificates were more user-friendly, replacing elementally focused design approaches, thus highlighting a transformative shift in building regulations and providing a clear indication of how energy efficient one's home was at a glance.

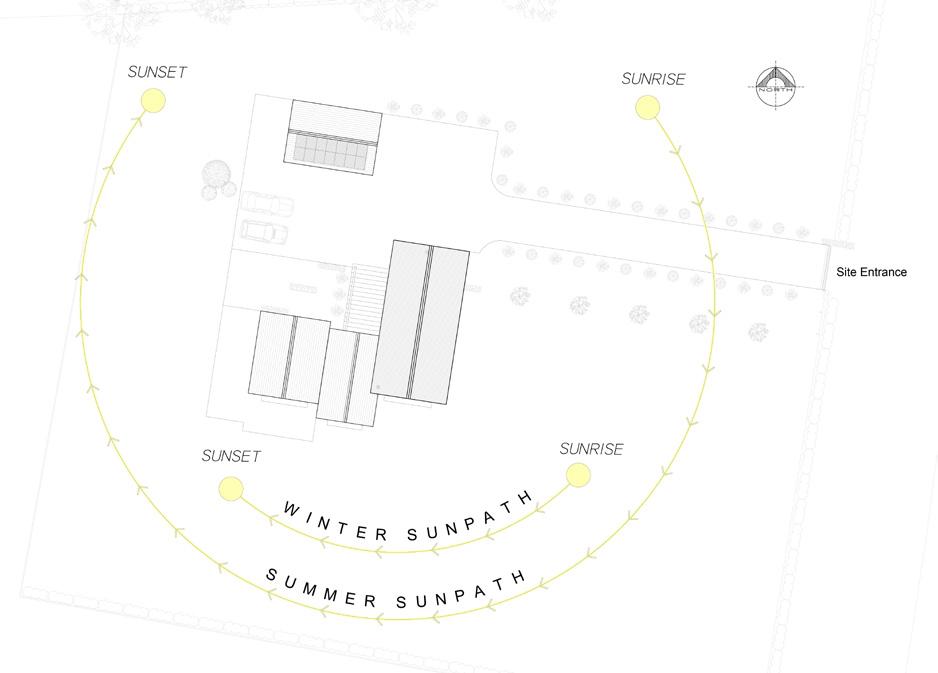

Amidst this backdrop, a young landscape architect embarked on constructing a pioneering low energy house near Brittas Bay, Wicklow, south of Dublin. Inspired by Harold Orr's Saskatchewan House (1977) and Wolfgang Feist's pioneering passive house in Darmstadt (1991), Tomas O’Leary erected Ireland and the UK's first passive house in 2004.

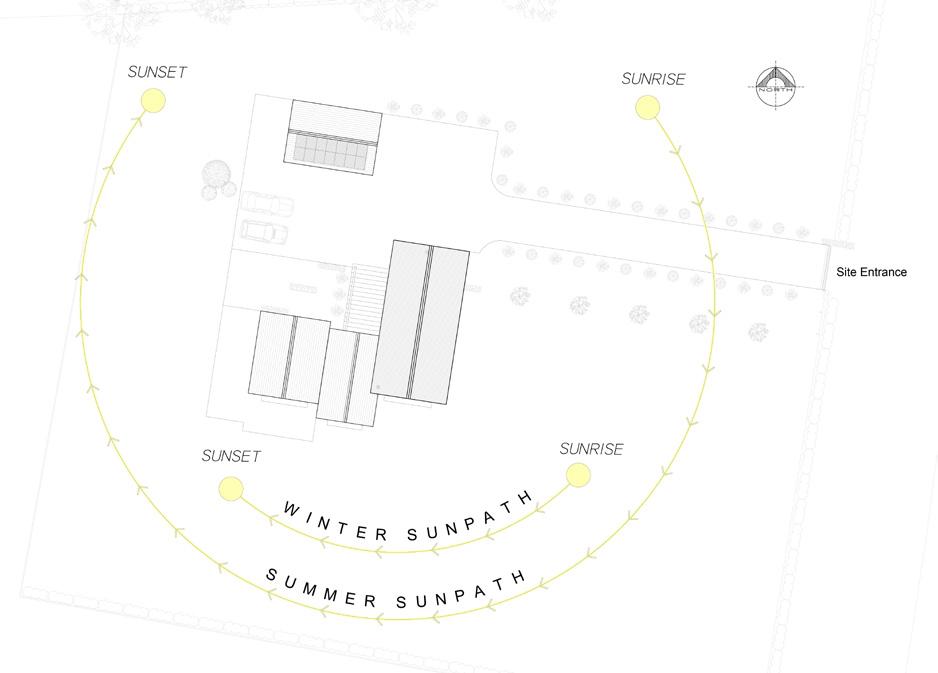

Drawing from the solar housing insights of the 1960s, the house optimised its orientation to the south for passive solar heat gain in winter. Super insulation, akin to Wayne Schick’s Lo-Cal house (1974), minimised heat loss. Frank Lloyd Wright's Usonian Houses (1937) informed the shading elements, while achieving an airtightness of 0.6 air changes per hour at 50 Pascals set new standards heretofore not seen in Ireland. Heat recovery ventilation and a pellet boiler supplemented the passive approach. Despite its 350 m² size, the house's 2008 heating bill totalled a mere €250 annually, equivalent to €0.71c/m²/yr or £0.61p/m²/yr.

In 2010, a BER assessment yielded a highly respectable A3 rating for the six-year-old house, reflecting its energy efficiency and good design. In 2023, to mark the 20th ‘birthday’ of the house, Tomas added a 6.5 kWp PV system which recovers two-thirds of the combined

regulated and unregulated loads on an annual basis. Tomas's advocacy of passive house design helped catalyse a shift towards low energy building in Ireland and the US, steering industry practices towards passive house principles. While passive house and building regulation approaches coexist, passive house standards demand rigorous adherence to higher standards encompassing shading, mechanical ventilation, airtightness, and thermal bridges. Though building regulations are progressing, the validity of BER as a desktop calculation, rather than a reflection of actual energy consumption, limits its relevance in the era of energy-positive buildings.

In retrofits, the BER may offer a more practical and cost-effective solution than passive house Enerphit, which requires substantial structural modifications to attain the necessary airtightness. Achieving an A1 BER rating is primarily feasible through external interventions, as demonstrated by RUA Architects’ renovation of a 1982 bungalow in early 2024. This approach minimises disruption to occupants while mitigating the loss of embodied energy.

Tomas O'Leary's 'Out of the Blue' passive house helped spark a paradigm shift in the construction industry, inspiring a second wave of industry pioneers to turn to passive house to deliver that most elusive of things: genuinely low energy buildings. It was the success of these projects that led this magazine’s progenitor, Construct Ireland (for a sustainable future), which had been founded in 2003 as Ireland’s first green building magazine, to become Passive House Plus and, encouraged by the AECB, expand into the UK in 2012.

Ireland’s first passive house was a catalyst, which heralded a significant amount of upskilling of designers and tradespeople in passive house courses, the rise of new manufacturers, business models, and the delivery of superior quality homes across Ireland and the UK.

In the next issue, we will delve deeper into the impact of building energy ratings and the evolution of low-energy retrofit strategies. n

Dr Marc Ó Riain is a lecturer in the Department of Architecture at Munster Technological University (MTU). He has a PhD in zero energy retrofit and has delivered both residential and commercial NZEB retrofits In Ireland. He is a director of RUA Architects and has a passion for the environment both built and natural.

DR MARC Ó RIAIN COLUMN 22 | passivehouseplus.co.uk | issue 47

A Complete System Approach

PH15 offers a construction system that is healthy for the planet, for the builders and for you. We will take care of the technical challenges, leaving you to enjoy high comfort and low utility bills.

Designed by Passivhaus experts, the PH15 system includes supply of a low carbon, fully insulated, airtight, timber frame, that is simple to erect using UK carpenters. PH15 includes the triple-glazing and ventilation system too.

The system is adaptable to a wide range of house shapes and external finishes to suit your vision. Ask for our PH15 Design Guide and aim to involve us early, before full planning submission, to optimise your project. We also offer house design packages.

Reimagining timber construction for a net zero future

Discover more at phhomes.co.uk

BOPAS Buildoffsite Property Assurance Scheme

ACE OF HERTS

ST ALBANS DEVELOPER BACKS

BIO-BASED PASSIVE HOUSE PLUS

Fancy owning an energy positive, timber-based passive house in one of the most desirable locations in England, without the hassle of having to build it yourself? A new three-house development nearing completion in Hertfordshire may be just the ticket.

By Jason Walsh

IN BRIEF

Development type: Three-unit private development

Method: Timber frame, insulated foundations, bio-based materials, hot water heat pump, PV

Location: St Albans

Standard: Passive house classic (pending), HQM and EPCs of A and comfortably above 100 in each case

Energy cost: Estimated net profit of £370-670/yr.

See 'In detail' panel for more information.

£370-670 net profit per year

24

What if a small development could prove a point? What if it could prove two? A new development in St Albans hopes to do just that: firstly, that world-class sustainable building could be the norm and, secondly, that it makes sense for the institutions financing house building and buying to consider energy use.

James Fisher, who developed the scheme along with business partner Troy Pickard says that, from the outset, the plan was to develop sustainable homes.

The two met while Pickard was working on another project and discovered that their interests aligned, specifically to create a development that acted as a kind of pilot light, signalling how residential building could be better.

“He was fed up with the industry’s resistance to new techniques. In the end we decided we had the perfect combination of skills,” Fisher said.

The project, located at 1-3 Haven Place, Park Street Lane in St Albans, consists of three dwellings, all detached and constructed using an offsite timber frame system on a

semi-rural brownfield site, with units one and two being three-storey and unit three being two-storey. All three are set to be certified to the passive house plus standard.

Fisher and Pickard functioned as their own main contractor, something that allowed them to control every aspect of the build and, they hoped, prove that sustainable house building was economically viable.

“I’ve spent 25 years telling everyone to be more energy efficient. The exceptionally large homebuilders, because the planners don’t know about development finance, are able to get away with [not doing] it. They just want to make as much money as they can.”

As a result, 1-3 Haven Place’s experimental nature led to the third, two-storey, unit in particular being a focus for proving the point.

“Will we recoup it? This is the experiment that we are going to have on that third home. It will have an EPC [Energy Performance Certificate] of 120. That’s groundbreaking for the south of England; it barely uses any energy across the year. We will find out if there’s a value case,” he said.

Architect Heather McNeill, director at AD Practice in St Albans, says Fisher came to the practice because of its reputation for energy efficient designs. (McNeill’s previous work on an Enerphit Plus project in nearby Harpenden was featured in issue 43 of Passive House+).

“We'd done some work on his own house before, and he knew about the passive house stuff we were doing. With this, he wanted to do a showcase project,” she said.

Working with Fisher, McNeill says, it soon became obvious that Fisher was committed to building ultra-low energy homes: “Certainly he feels there should be a drive toward passive house.”

Similarly, Fisher was more than confident in choosing AD Practice. “We knew that Heather and the practice have a strong appetite for passive house. There was no sales [effort] required,” he said.

Nonetheless, the project was breaking new ground for AD Practice, which hitherto had concentrated its efforts on retrofits.

“This was our first new build passive, because we started the hard way with retrofits,

CASE STUDY ST ALBANS ph+ | st albans case study | 25

The right mortgage provider will give a 1.5 per cent discount. Will the market respond to that? I think it will.

and it was the only one that has got more than one unit,” McNeill said.

The three cellulose-insulated timber frame buildings were prefabricated offsite by passive house stalwarts PYC in Welshpool, and sit on an Isoquick insulated foundation system.

Planning, often contentious in the south of England, was a challenge as the modern, timber-clad houses sit in counterpoint to the nearby bungalows and traditional houses in the leafy locale.

Two of the houses have their bedrooms on the ground floor, responding to the site.

“It’s a very wooded site. The fact that the two houses are ‘upside-down’ was done to make the most of the view, and it was also a case of [avoiding] overlooking with neighbours,” McNeill said.

However, AD Practice was able to design dwellings that offer significant architectural interest and also respond to a common problem with British houses: a lack of light inside.

“Obviously, they do look very different, but they're not really on a street view, so that did give us a possibility to do things that are a little different. They’re obviously highly glazed,” McNeill said.

This touches on a common misconception about passive houses: that they must have small windows. In fact, the houses at Haven Place deliver more light than is traditional across the UK’s housing stock.

“They do follow the traditional north side having very few openings, but we were concerned with getting natural light, and ventilation in during the summer.”

“From our point of view, if you were to take a site and design a traditional passive house, it probably wouldn't look like these. The forms didn’t lend themselves to it, but it had an architectural vision. It shows what can be done with some effort,” she said.

Green financing

A notable part of the plan for 1-3 Haven Place was to prove that energy-efficient houses made economic sense, both in terms of energy saving and also financing.

Indeed, the UK government has been encouraging mortgage lenders to develop green mortgage products since publishing its Clean Growth Strategy in 2017.

Fisher said that getting developers, and plan-

ners, to recognise this was important as he felt homebuyers would clearly see the benefit.

Ecology Building Society, the development mortgage provider on the build, provided a discount based on the building’s planned performance, something Fisher said was worth noting and could have a positive impact on developments by supporting a drive to aim higher when it comes to sustainability.

“The right mortgage provider will give a 1.5 per cent discount. Will the market respond to that? I think it will,” he said.

Other factors changed the calculations slightly, but not disastrously, and they were felt universally across the industry, such as material cost increases due to the perfect storm caused by Covid, Brexit and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

“We got hit by the supply chain crunch and cost rises. We have cedar cladding [for example],” he said.

The development stays true to the original principles of passive house, in that it really

does rely almost entirely on internal gains from appliance use, optimised passive solar gains, high quality heat recovery ventilation, and high performance fabric, rather than on hydronic heating.

And as the scheme nears completion, there are already signs that the strategy is working. Across a warm weekend at the end of March, Fisher noted the temperatures throughout the day were hovering around 16 C - before the electrical connections had been turned on, and therefore without the benefit of any internal gains “from anything basically”, and with no heat recovery ventilation.

Two direct electric radiators - described by Fisher as “belt and braces” have been provided for each house to boost temperatures as a last resort, but these are expected to be ornamental. An electric towel rail has been fitted in all bathrooms – in recognition of the fact that people tend to look for higher temperatures when coming out of showers or baths. Fisher may add post heaters to the ventilation

ST ALBANS CASE STUDY 26 | passivehouseplus.co.uk | issue 47

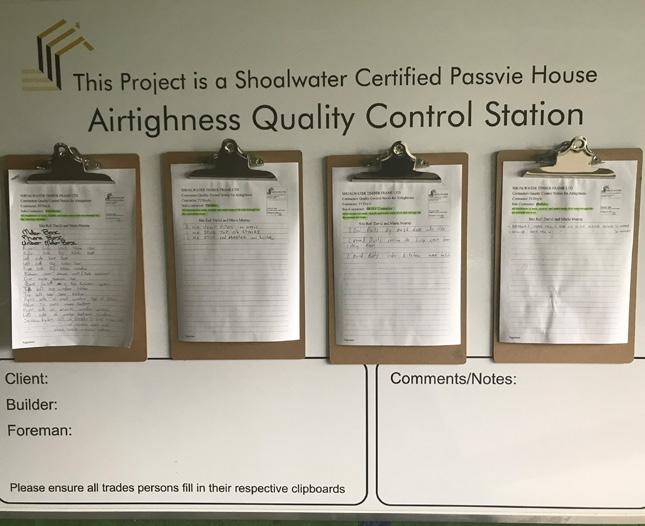

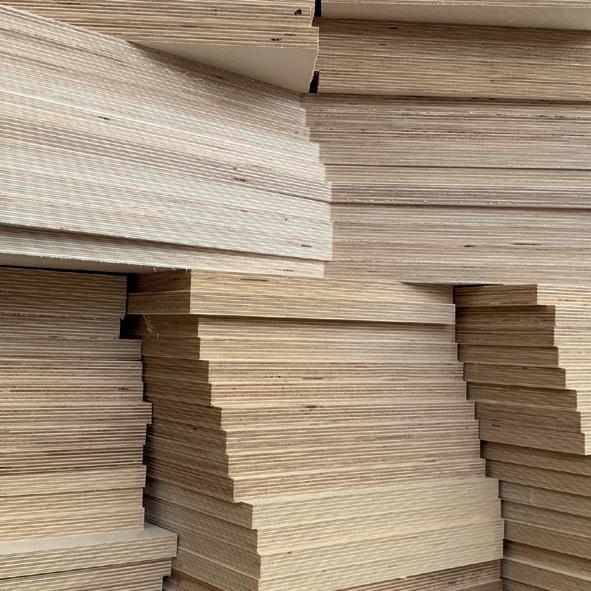

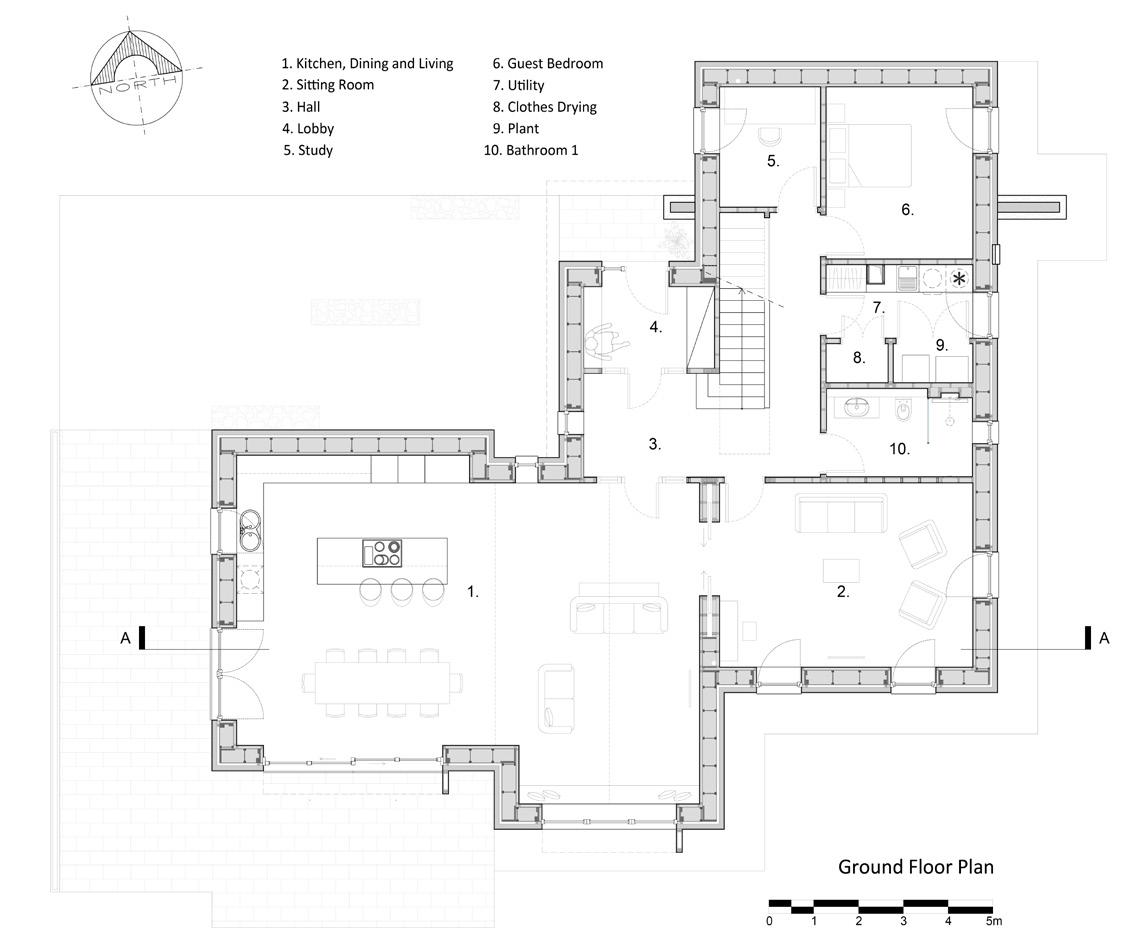

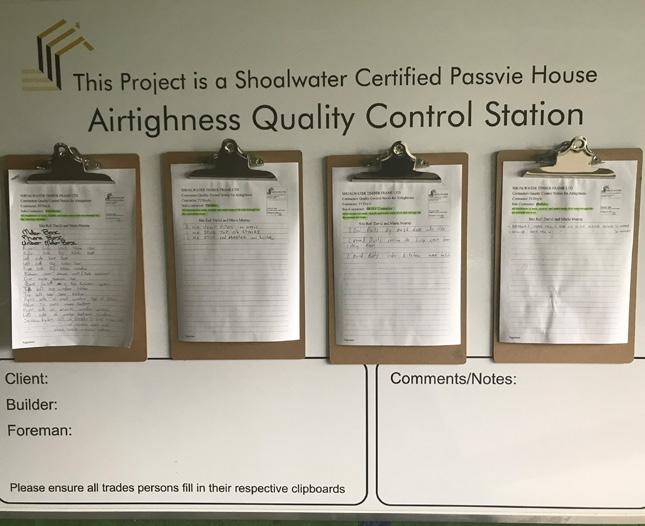

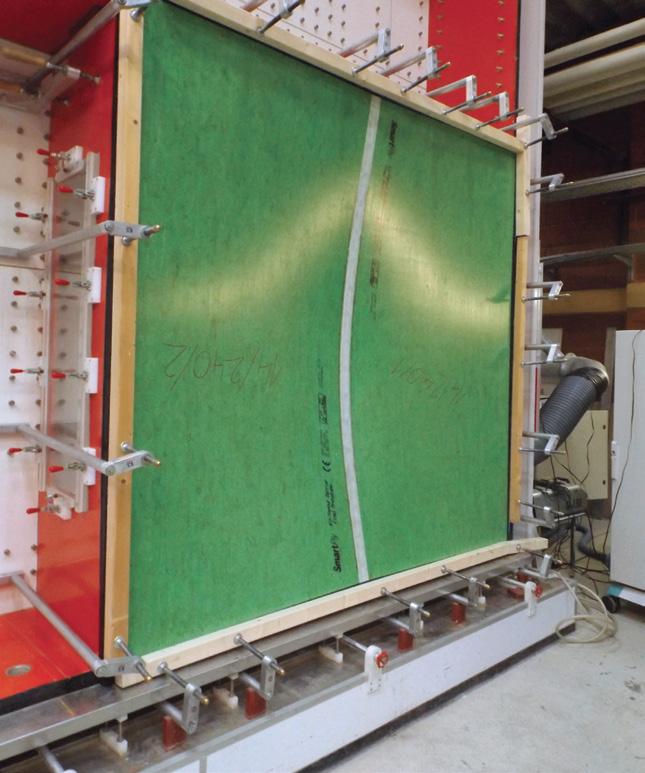

1 & 2 The existing bungalow on site which was demolished; 3 site cleared in preparation for the new build; 4, 5 & 6 ground floor build-up features a passive house certified Isoquick insulated raft foundation system; 7 erection of the timber frame structure which was prefabricated offsite by passive house stalwarts PYC; 8 & 9 timber frame walls with Smartply Airtight OSB airtight layer; 10 bolted flitch plate at glulam roof beam and post connection; 11 stainless steel ductwork for the MVHR system; 12 Fronta WA breather membrane protects the frame, with battens and counterbattens awaiting cladding.

system if the houses require it in reality.

Although the development is small compared to those of the mainstream UK homebuilders, Fisher says 1-3 Haven Place has the potential to act as a harbinger of how to build better. Noting the International Capital Market Association’s Green Bond Principles – which include passive house among the benchmarks for green building – he says there is no reason to think energy-efficient buildings will be difficult to finance.

The industry realising this, he says, would transform the country’s housing landscape.

“When you watch Grand Designs or George Clarke, all the people who do passive houses are self-builders. We don’t see many passive houses for sale. I felt I had to do my bit to change that,” he said.

“We have houses here that are meeting the UK’s future housing needs.”

SELECTED PROJECT DETAILS

Client: Surreal Estate Developments

Architect: AD Practice

Mechanical/electrical engineer: 21° (formerly known as Green Building Store)

Structural engineer: PYC

Energy consultant:

Ashby Energy Assessors

Project management:

Surreal Estate Developments

Main contractor:

Surreal Estate Developments

MVHR system: Ubbink

MVHR contractor: Apex Ventilations

Airtightness testing: Ashby Energy Assessors

Passive house certifier:

Mead Consulting

Build system,wall, roof and floor

insulation: PYC

Insulated foundation system: Isoquick, via Build Homes Better

Building boards: Medite Smartply

Windows and doors: 21° (formerly known as Green Building Store)

Cladding: Millworks

External slab screed: Base Concrete PV/heat pump: Solinvictus

CASE STUDY ST ALBANS ph+ | st albans case study | 27 3

WANT TO KNOW MORE? The digital version of this magazine includes access to exclusive galleries of architectural drawings. The digital magazine is available to subscribers on passivehouseplus.ie & passivehouseplus.co.uk 4 1 2 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12

discover your core strength

WITH MORALT FERRO DOOR BLANKS FROM JAMES LATHAM

Available in the UK from James Latham, Moralt’s FERRO door blanks offer the highest levels of strength and performance. The range includes FERRO Passiv, Moralt’s energy saver door blank which is perfect for Passive House projects. Its high-quality thermal insulation and technically sophisticated construction provide optimum conditions for a comfortable indoor climate. The specially isolated flat iron stabilizer prevents any thermal bridges and avoids condensation problems. Moralt FERRO door blanks benefit from a 10 year anti-warping guarantee and with innovative core technologies to suit your particular specification, the FERRO range really does offer a door for everyone...

| issue 47

For more info visit lathamtimber.co.uk or email info@lathams.co.uk

Developer James Fisher, whose day job is the head of strategic relationships at the Building Research Establishment (BRE), stressed that the project was independent of the company. However, there is an interesting overlap, as Fisher is putting the development through the BRE’s Home Quality Mark (HQM) certification process.

Rooted in BRE’s BREEAM standard for sustainable construction of commercial and industrial standards, HQM was introduced in 2015.

However, BRE has a history of offering sustainability certification in the residential sector. Immediately predating HQM was the UK’s Code for Sustainable Homes voluntary standard, which was developed with input from BRE, implemented by the British government in 2007 and withdrawn in 2015, when some aspects were folded into Building Standards. Prior to the code, BRE’s EcoHomes rating scheme performed a similar function from 2000 to 2007.

Jennifer Dudley, product manager for residential housing at BRE, said that HQM’s foundation in BREEAM means that it is rooted in science, but the two standards differ as HQM reflects the specificities not only of residential construction, but of how people live in homes.

“It’s designed to be a holistic view of sustainability, but with the homeowner and improving the home for the occupant at its core. At its heart it's a BREEAM scheme; it’s built on the same 30 years of history and science as the BREEAM,” she said.

Homes rated under HQM are independently evaluated by a BRE-licensed assessor who analyses a dwelling’s overall running costs, the impact on the occupant’s health and wellbeing, the home’s environmental footprint, its resilience to flooding and overheating, and transport links.

“Broadly, one of things that HQM does

that is different is we looked at the change in the sector over the last decade, [and so we decided] to look at the quality of the process, so it looks at things like handover and aftercare.

“We have a number of minimum requirements to meet any level of stars across HQM, so there is an entry level, and we have what you might call the menu of credits above that,” Dudley said.

Internally within HQM, a certain amount of tradability is allowed, meaning buildings do not have to score highly in every area in order to be certified. However, Dudley said the standard has measures in place to ensure that buildings are not given overly optimistic ratings, for instance with mediocre fabric offset by large renewable energy systems.

“Another difference is we introduced indicators: every home gets a triple bottom line indication and there are backstops within those, meaning you have to achieve some credits in each area,” she said.

As noted in BRE’s HQM Technical Manual, backstop indicators seek to ensure that “key issues (specific to that indicator) are not overlooked when targeting a high score [...] For example, to achieve a score of three in the 'wellbeing' indicator, a home must achieve three credits in the 'daylight' issue.”

BRE says that HQM includes measurement of embodied carbon as part of a wide-ranging assessment of the environmental impact of construction materials. This measures impact compared to benchmark values in Ecopoints. However, this means that although carbon impacts are measured, they cannot easily be reported.

Dudley acknowledges this, but says carbon is considered and further developments in HQM will address it more directly.

For example, with version 7, BRE wants to move away from Ecopoints and explicitly measure embodied carbon impacts and introduce additional carbon reporting functional-

ity that covers both embodied carbon and operational carbon emissions from energy water and refrigerant gases.

“We have an energy category for operational [energy use], we have a materials category, [and] we have things like pollution and water, things that relate to carbon. We measure and analyse each separately, but don't report it yet,” she said.

“It currently outputs an Ecopoint and doesn't translate hugely well into how industry talks about carbon,” she said.

This will change as HQM adapts to version 7 of BREEAM, which is expected to be published later this year and integrated into HQM after that: “We’re looking to shift that for version 7, which is to draw out these things and standardise the metrics, including embodied carbon,” Dudley said.

Version 7 is also intended to bring deeper integration with the EU taxonomy for sustainable activities, with BRE noting that customers have, despite the UK’s exit from the bloc, recognised the benefit of aligning to the taxonomy. In addition, Dudley said, stakeholders beyond developers and homeowners have expressed interest in HQM, notably investors seeking better environmental, social and governance (ESG) and socially responsible investing (SRI) rankings.

In the meantime, Dudley says BRE sees HQM as a rating that will be easy for buyers to understand but also rooted in rigorous standards and real, scientific testing.

“The independent, third-party element of the certification is important. It's not self-claimed.

“BREEAM recognises performance that goes beyond legislation. By recognising current best practice and outstanding performance levels. So BREEAM moves forward in line with legislation and best practice,” she said.

CASE STUDY ST ALBANS ph+ | st albans case study | 29

MARKING QUALITY AND SUSTAINABILITY

ST ALBANS CASE STUDY 30 | passivehouseplus.co.uk | issue 47 01938 500 797 | info@pycgroup.co.uk www.pycconstruction.co.uk Experts in Passive House offsite timber frame construction U values ranging from 0 13 - 0 10W/m²K Guaranteed airtightness below 0 6ach Highly sustainable product using Warmcel insulation UK wide installation Call 01953 687332 or visit beattiepassive.com Net Zero Healthy Homes Low Bills

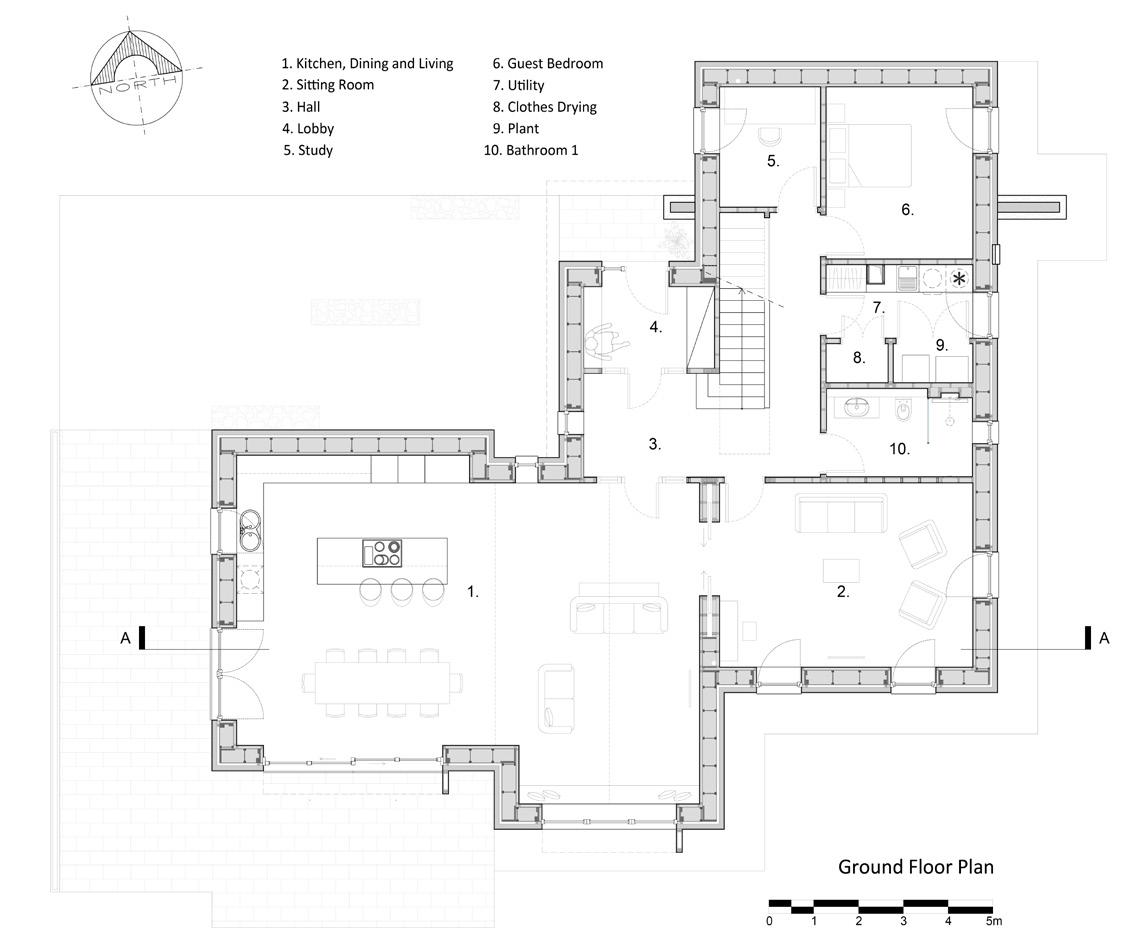

Development type: Three detached, offsite timber frame homes.

Dwelling 1: 287 m2, three-storey.

Dwelling 2: 281 m2, three-storey.

Dwelling 3: 157 m2, two-storey.

Site type & location: Brownfield site (demolition of existing bungalow), semi-rural location, just outside St. Albans in Hertfordshire.

Completion date: Expected April 2024.

Budget: £3,000/m2 including professional fees but excluding land purchase.

Passive house certification: Passive House Plus certification pending across all three units.

Space heating demand (PHPP): 13 kWh/m2/ yr (unit 1), 12 kWh/m2/yr (unit 2) and 15 kWh/m2/ yr (unit 3).

Heat load (PHPP): 11 W/m2 (unit 1), 10 W/m2 (unit 2) and 11 W/m2 (unit 3).

Primary energy non-renewable (PHPP): 102 kWh/m2/yr (unit 1), 94 kWh/m2/yr (unit 2) and 136 kWh/m2/yr (unit 3).

Primary energy renewable (PHPP): 72 kWh/m2/ yr (unit 1), 76 kWh/m2/yr (unit 2) and 106 kWh/m2/ yr (unit 3).

Heat loss form factor (PHPP): 2.99 (unit 1), 3.02 (unit 2) and 3.51 (unit 3).

Overheating (PHPP, calculated percentage of year above 25 C): 6 per cent (unit 1), 7 per cent (unit 2) and 8 per cent (unit 3).

Assumed occupancy: 2 adults & 2 children for each dwelling.

Environmental assessment method: BRE’s Home Quality Mark 4 stars targeted across all three units. Result pending.

Airtightness (At 50 Pascals): Interim results after second test. Final results & test pending. 0.28 ACH (unit 1), 0.23 ACH (unit 2) and 0.34 ACH (unit 3).

Energy Performance Certificate (EPC): Results will be confirmed after final set of airtightness tests. 107 A (unit 1), 111 A (unit 2) and 120 A (unit 3).

Embodied carbon: No assessment has been completed.

Measured energy consumption: Properties not

yet occupied.

Thermal bridging: The PYC engineered I-beam has solid ‘flanges’ on both sides which are connected by an 8 mm web of OSB, which, being so narrow reduces thermal bridging to extremely low levels. The complex shape of the I-beam is easily filled with pressure injected Warmcel insulation to the required high densities maintaining insulation continuity. Y-factors (from SAP) calculated for each home, at 0.0276 W/m2K (dwelling 1), 0.0274 W/m2K (dwelling 2) and 0.031 W/m2K (dwelling 3)

Estimated energy bills: All houses estimated to be generating net profits on energy costs, considering bills versus feed in tariff payments. Costs calculated from SAP 2012 worksheet. Inclusive of all heating & hot water costs but exclusive of standing charges.

Dwelling 1: -£371.05

Dwelling 2: -£604.32

Dwelling 3: -£670.04

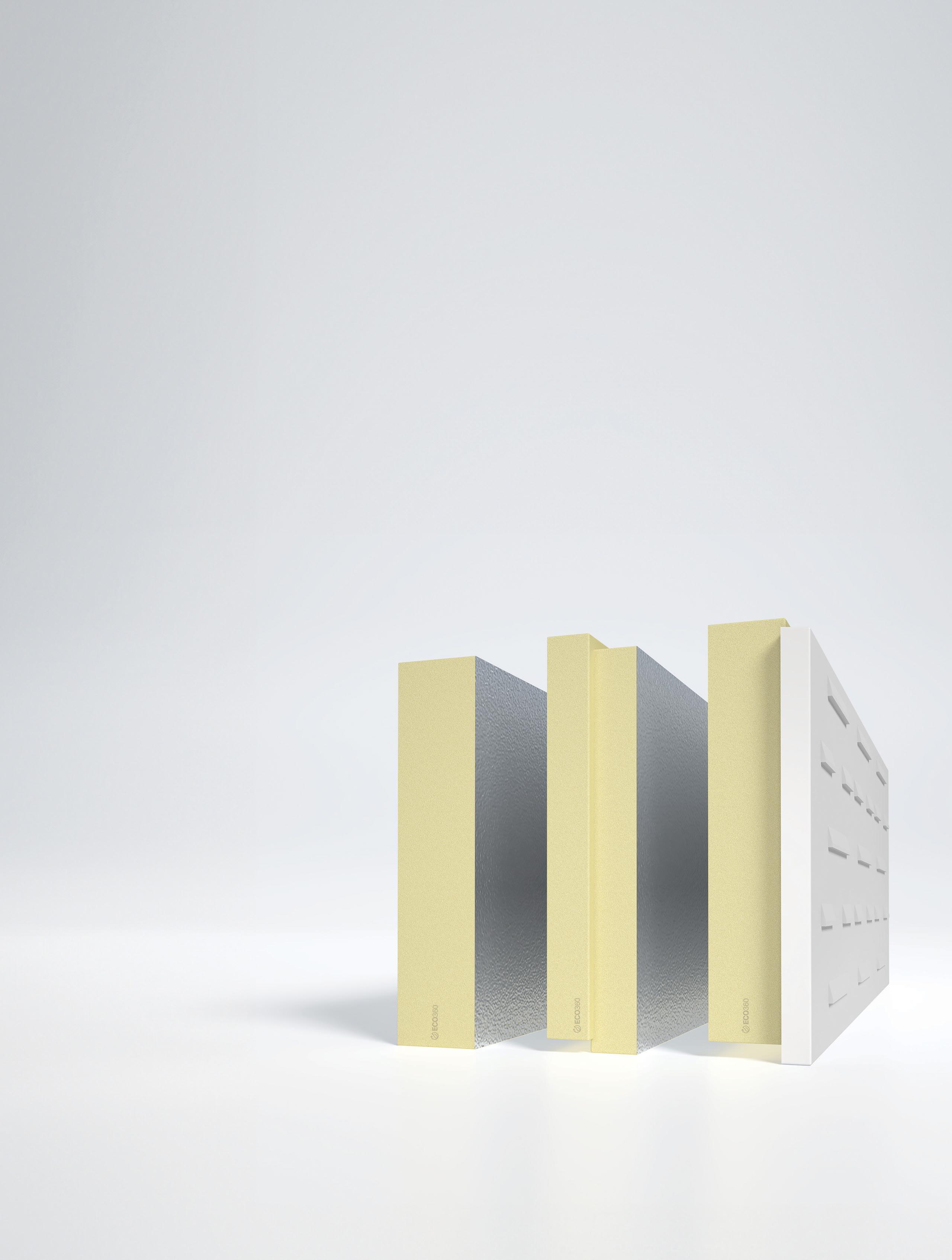

Ground floor: The Passive House Institutecertified Isoquick insulated raft foundation system from Build Homes Better has been used on all plots and has been designed for a 250 mm reinforced concrete slab, using the EM10 edge profile. Units 1 and 2 had 250 mm EPS, and a U-value of 0.11 W/m2K, while unit 3 had 300 mm of EPS, and a U-value of 0.09 W/m2K. The floor system is PHI certified.

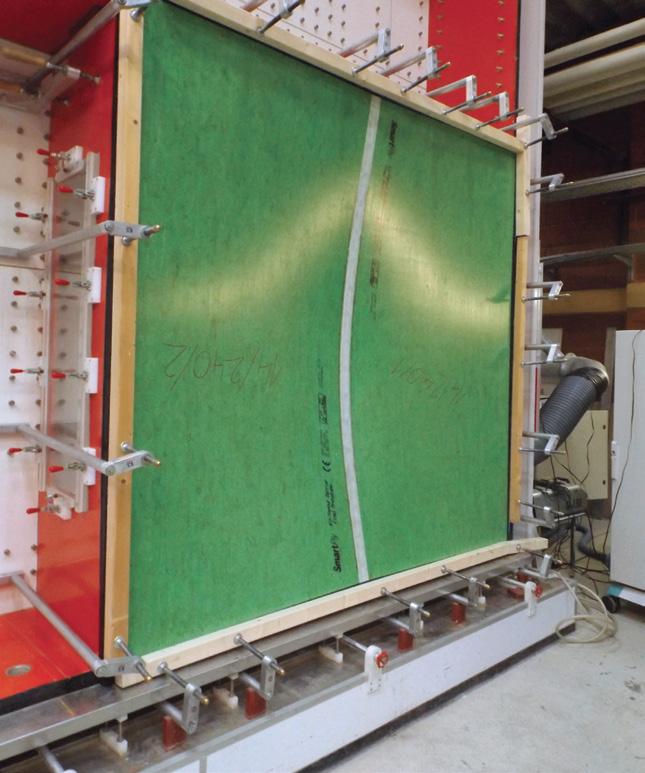

Walls (across all three dwellings): 45 mm service void; 12.5 mm Smartply Airtight OSB board; 300 mm I-beam fully filled with Warmcel cellulose fibre insulation; 12 mm Medite Vent breathable sheathing board; Proclima Fronta WA breather membrane. U-Value 0.125 W/m2K.

Roofs (across all three dwellings): 45 mm service void; 12.5 mm Smartply airtight OSB board; 300 mm I-beam fully filled with Warmcel cellulose fibre insulation; 12 mm Medite Vent breathable sheathing board; Proclima Solitex Plus breather membrane. U-Value 0.126 W/m2K.

Windows and external doors: timber framed Ultra (now GBS98) triple glazed windows with a U-value of 0.75 W/m2K. Ultra (now GBS98) timber triple glazed doors or insulated panel doors with