1 DRAWING ROOM DISPLAYS Fleeting Encounters British Art and the Connoisseurial Gaze Hans C. Hönes 19 September 2022–6 January 2023

Attentive looking is commonly deemed one of the core skills of an art historian. Analysing, attributing, and appraising an artwork relies on close observation and careful investigation of the visual evidence. Countless art writers have eulogised this moment of immersion as the precondition for training the eye. In this spirit, Kenneth Clark advised the young Benedict Nicolson to “visit as many galleries as possible & look at all the pictures you like as long as possible”. In the eyes of many, this is what sets art historians apart from colleagues in other disciplines: when writing about art, historians or scholars of literature merely spout “witty phrases that betray the complete lack of any serious study of art”—as Jean Paul Richter (a friend of the connoisseurs Giovanni Morelli and Bernard Berenson) once phrased it. The art historian, on the other hand, had learned to look.

And yet, more often than not, the encounters between the art historian and their objects of study are brief, fleeting indeed. For historians of British art, this was perhaps particularly acute an issue, since many works have been in private possession until recently. Behind country house doors, or in the sales rooms of auction houses, they only became visible to the expert eye for brief, occasional glimpses.

1 Introduction

[opposite] A selection of items from the display [above] Item 3

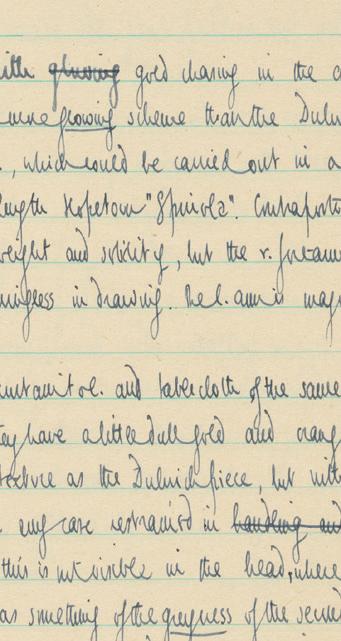

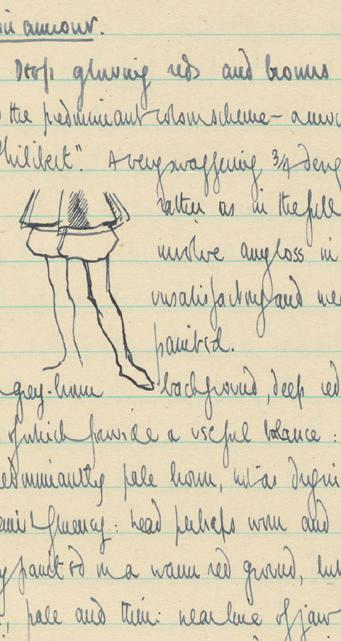

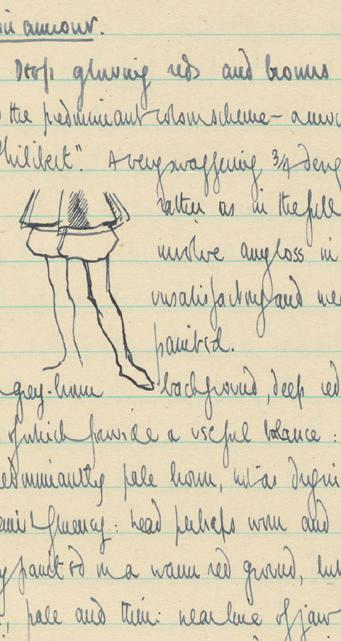

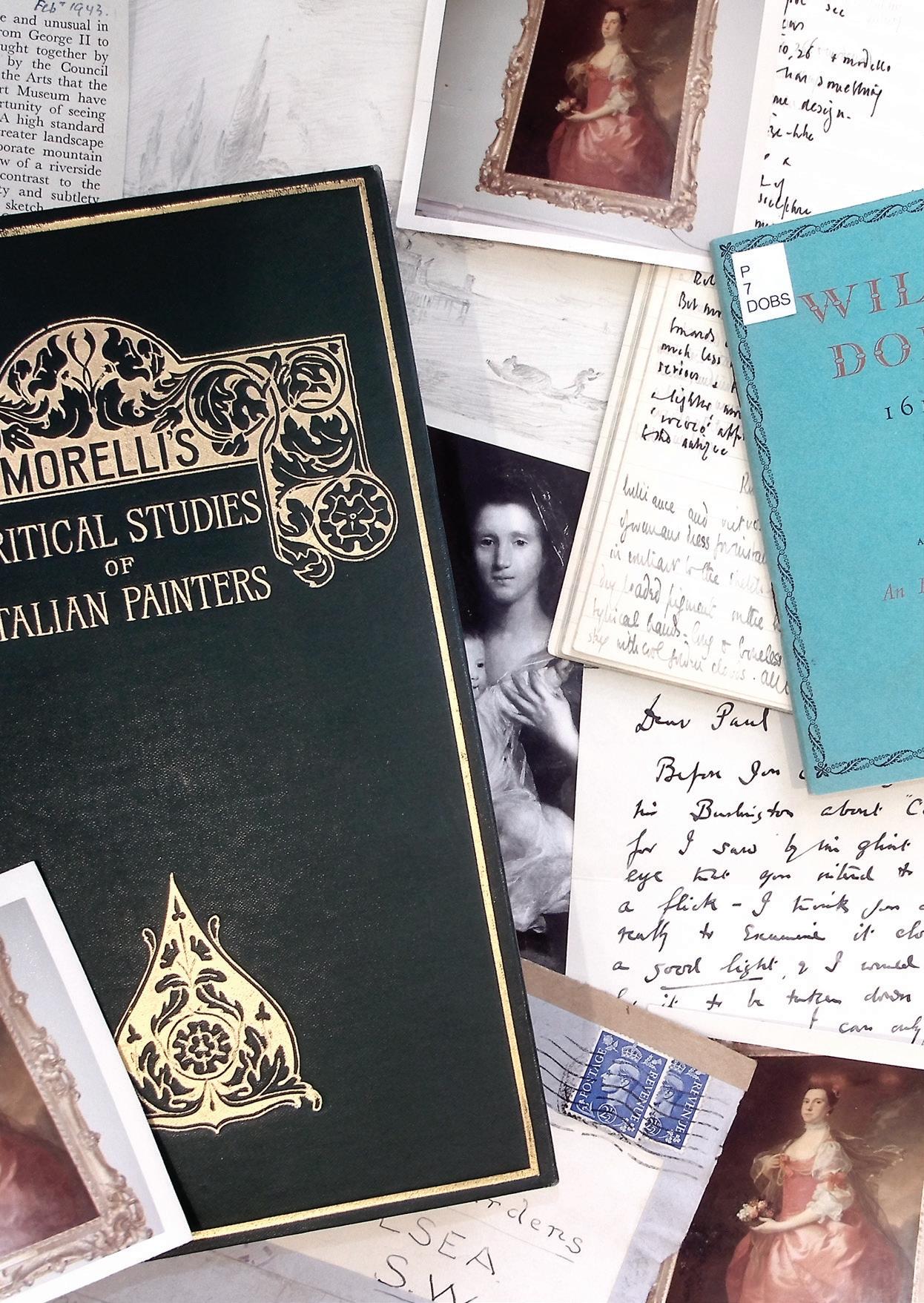

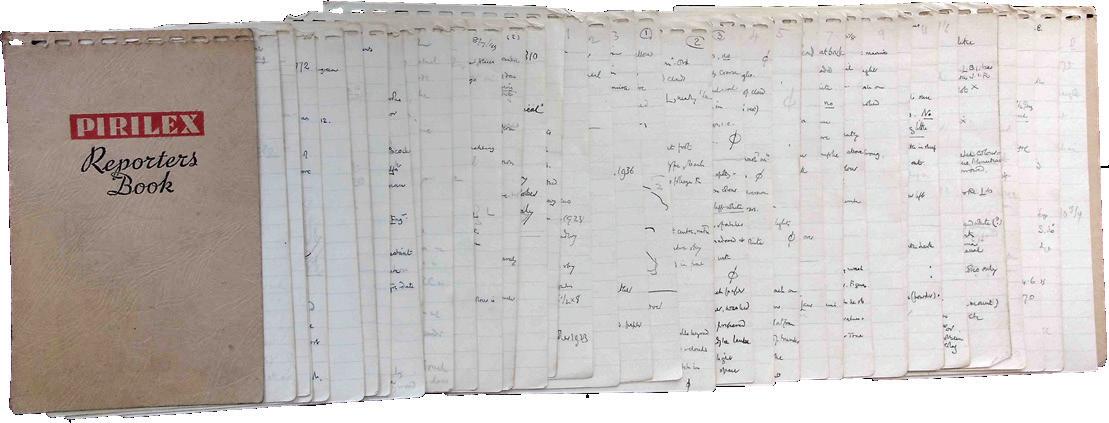

This display focuses on the material traces of such encounters, and on the myriad of ways with which art historians attempted to document their instantaneous impressions: on notepads, scribbled full with aesthetic observations and comments on technical facts; in postage-stamp-sized drawings, capturing key characteristics of the work in question; or by means photographs of works seen or unseen, and annotated with whatever struck the eye.

The materials assembled for this Drawing Room Display are mainly taken from the Paul Mellon Centre’s Collected Archives, and spotlight items from the archives of scholars such as W.G. Constable, Paul Oppé, Ellis Waterhouse, and Oliver Millar. Much of the material stems from the formational phase in British art history, before the subject’s academic expansion in the 1960s.

The period from the 1930s–1950s was a time where art historical research was still very much an informal business conducted between amateurs, private owners, and museum officials.

The documents on display are also evidence of the networks and practices of art historical scholarship in Britain at the time. The work of the scholars discussed in this display also documents the professionalisation of the field, and the increasing attempts to find ways of systematically documenting the history of British art.

2

[left & right] Front and back of Item 2

Upright Display Case

I. Fleeting Encounters

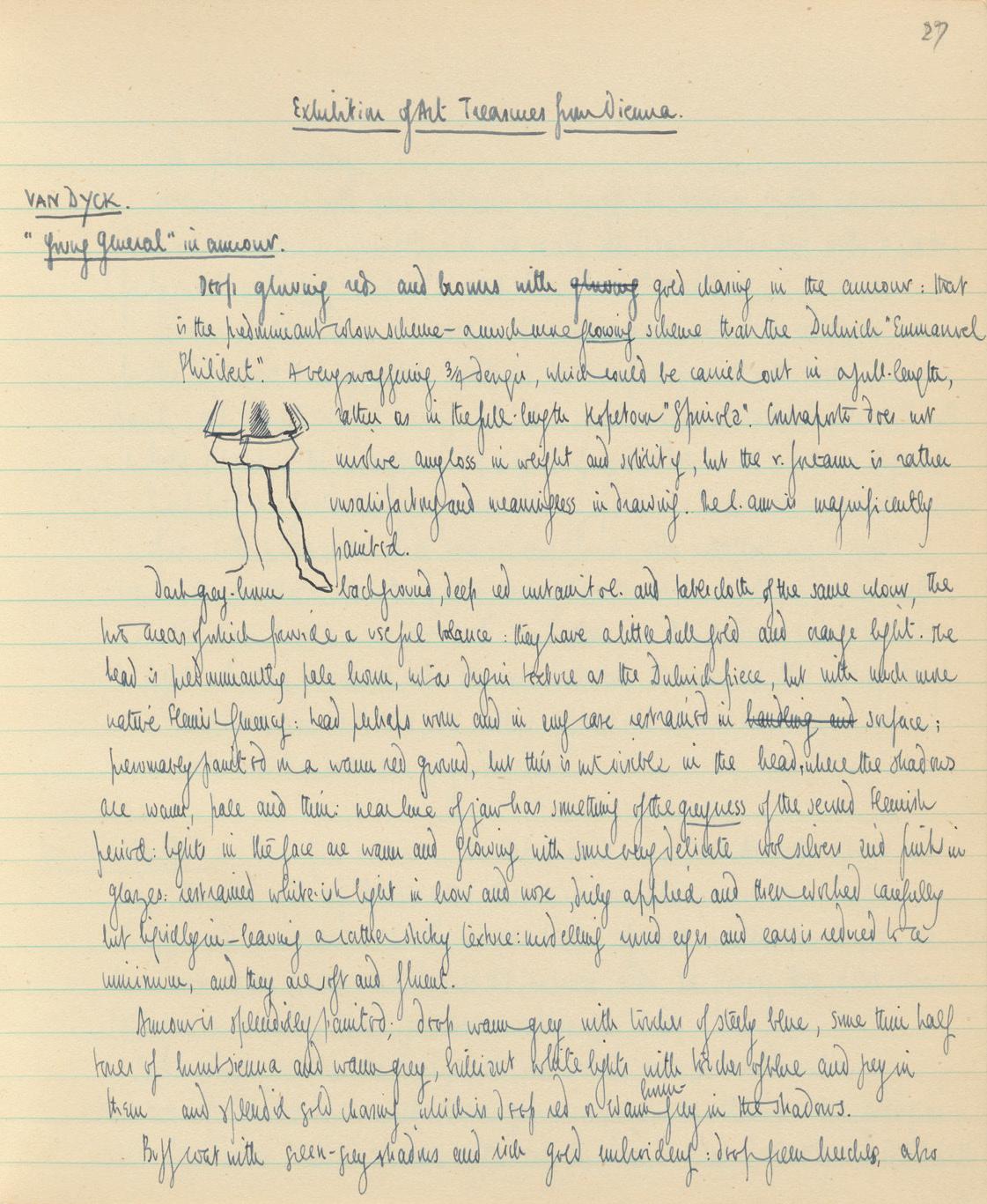

Few art historians have unlimited access to their objects of study. In many instances, scholars are only able to see the works they hope to study for short snatches of time— while visiting a museum abroad (where scores of other works are waiting to be inspected), between polite conversations during a visit to a private collector’s home, or in the salesroom before an auction. The art historian not only had to attempt to record their impressions in their visual memory. They also had to make snap judgements and instant observations—often rapidly scribbled down on whatever came to hand. Some scholars had a very systematic approach to note-taking:

1

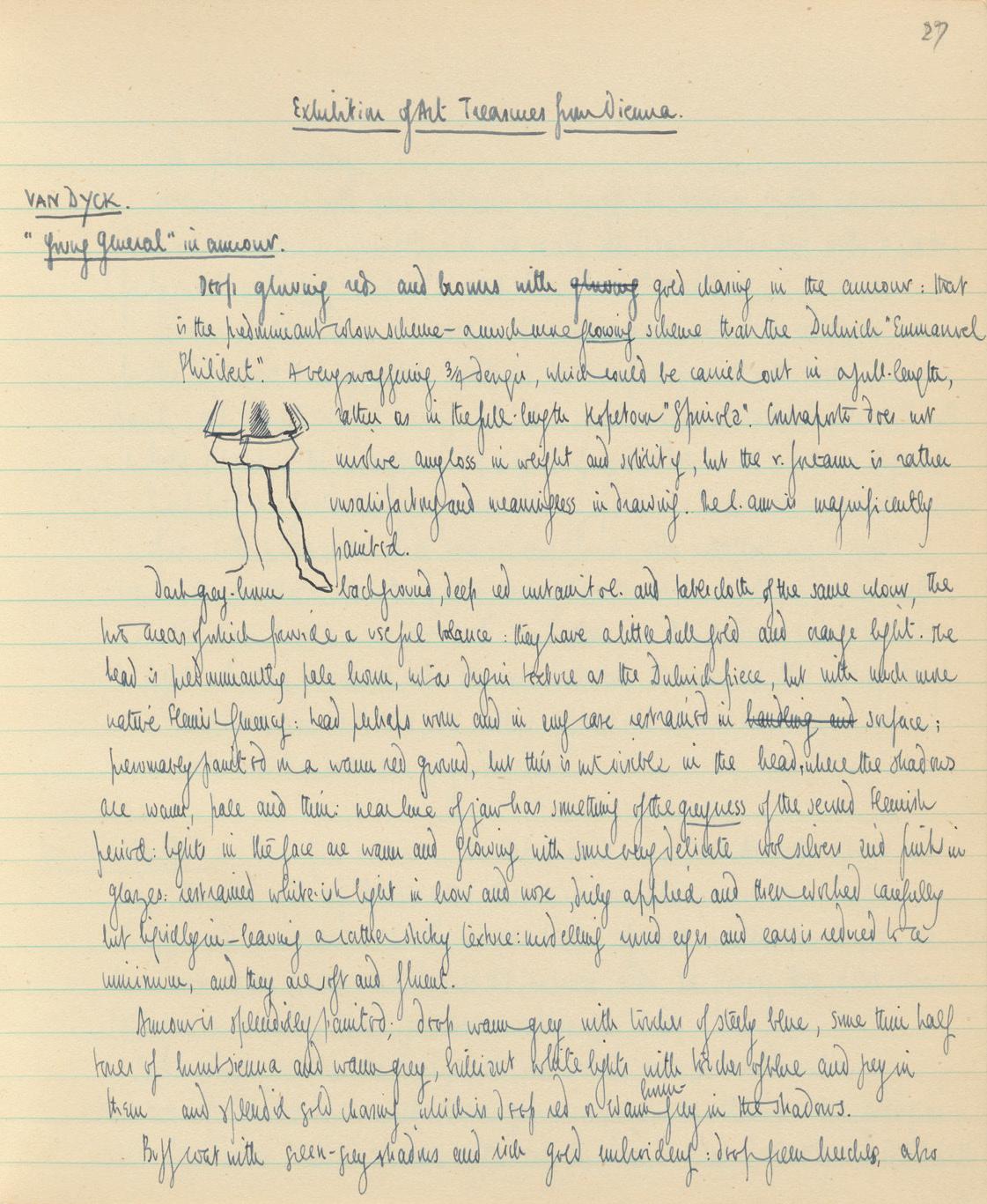

Oliver Millar, Notes from a Visit to the Exhibition “Art Treasures from Vienna”, Journal 5, 1949, 100.

AR: ONM/1/2/5

2

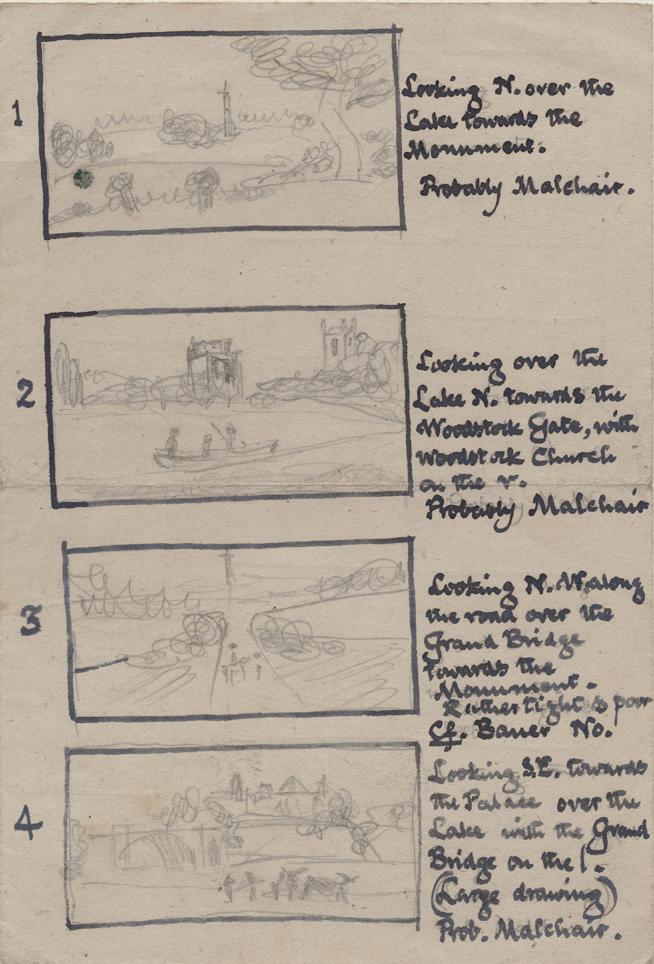

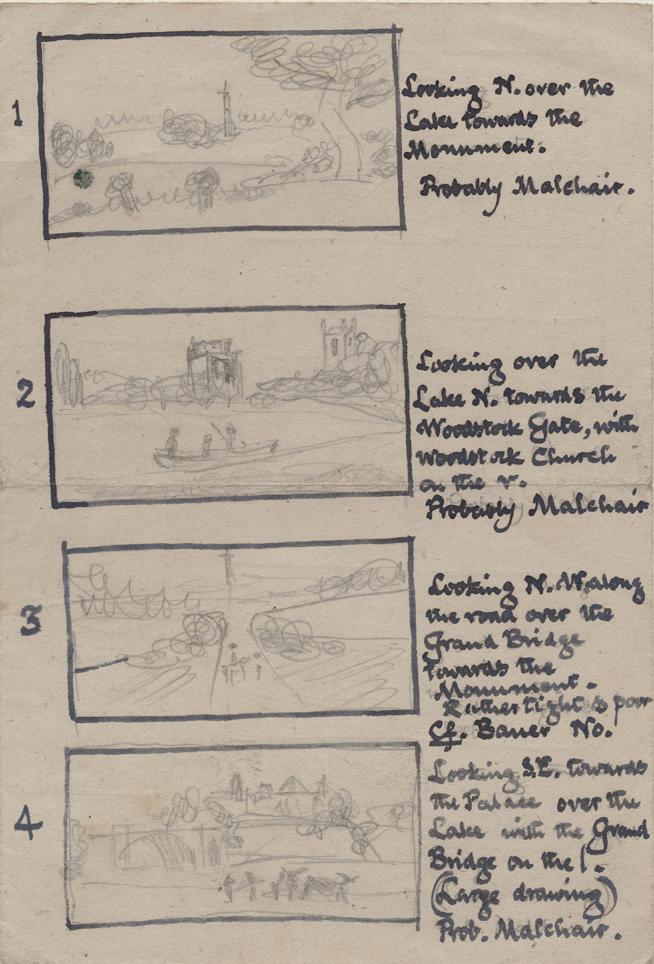

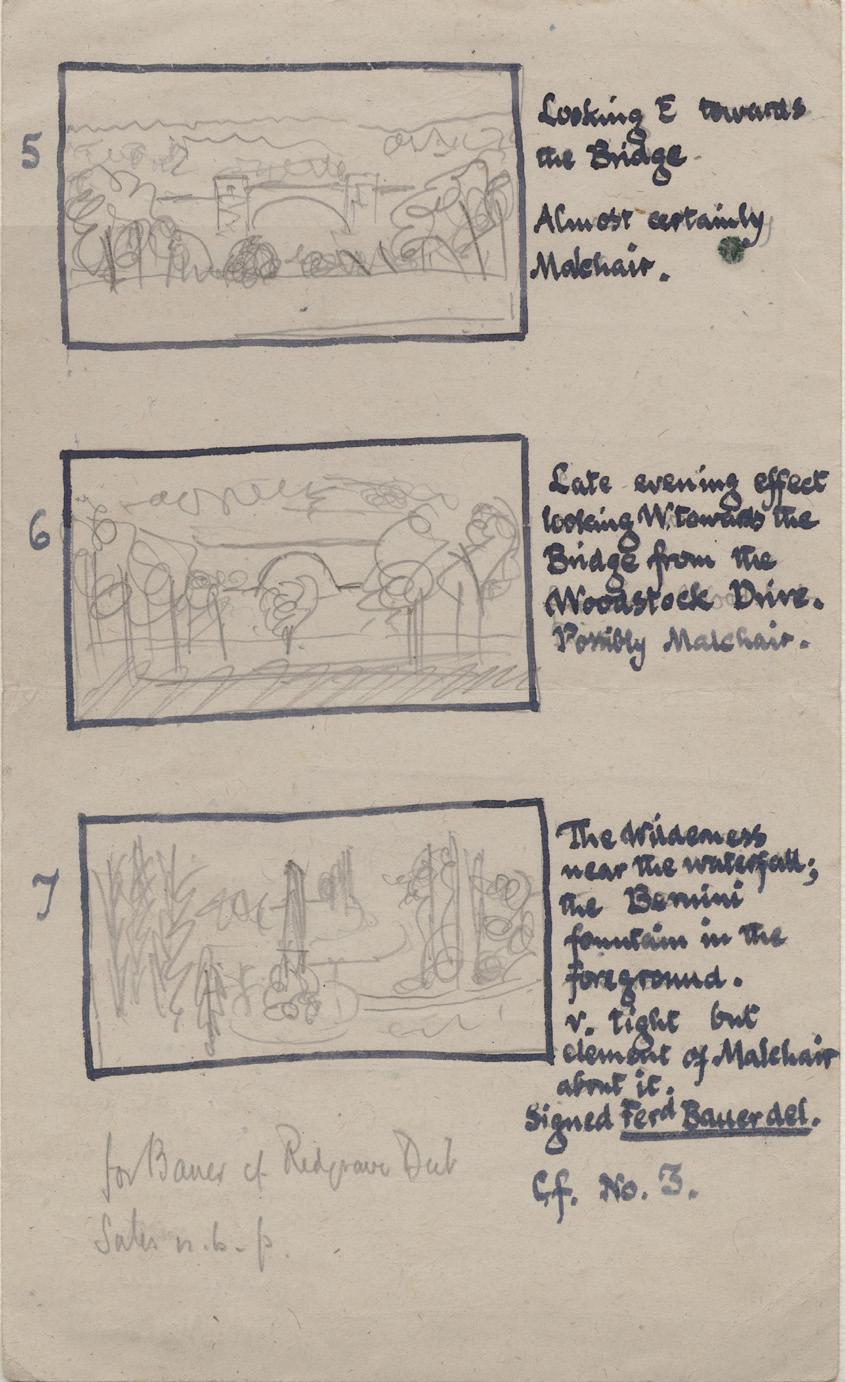

Paul Oppé, Research Notes on Works by John Baptist Malchair. Drawings.

AR: APO/1/14/2

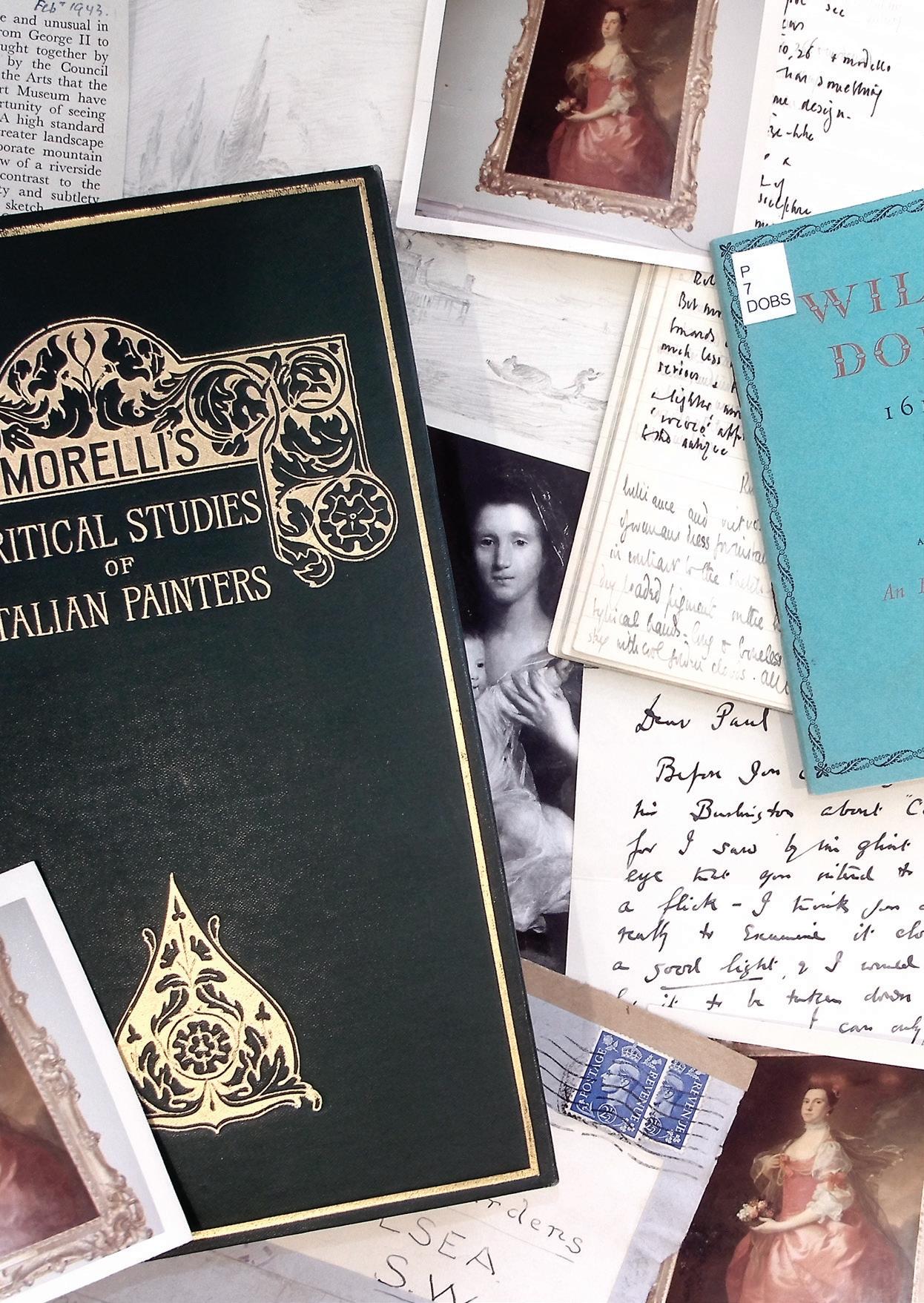

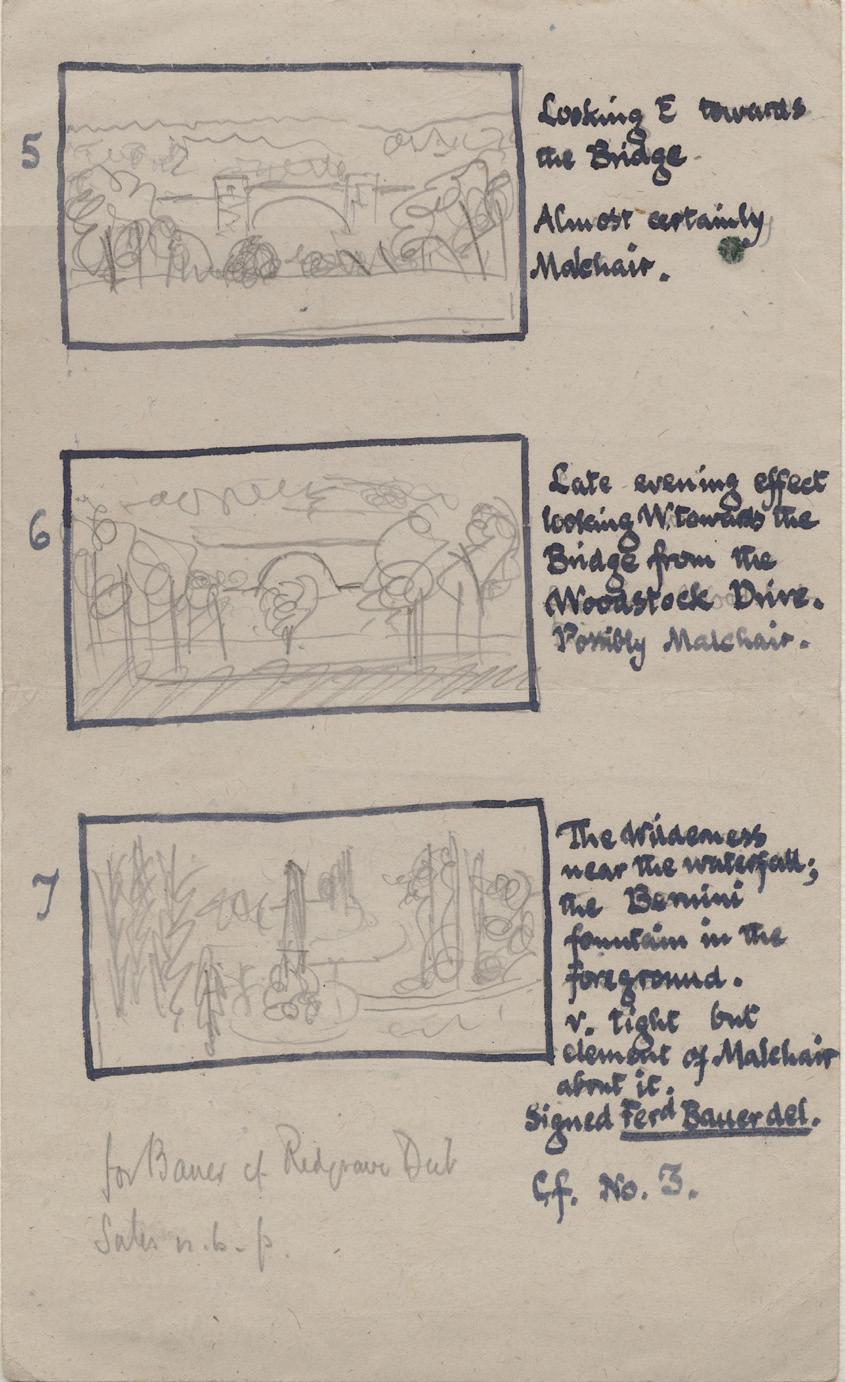

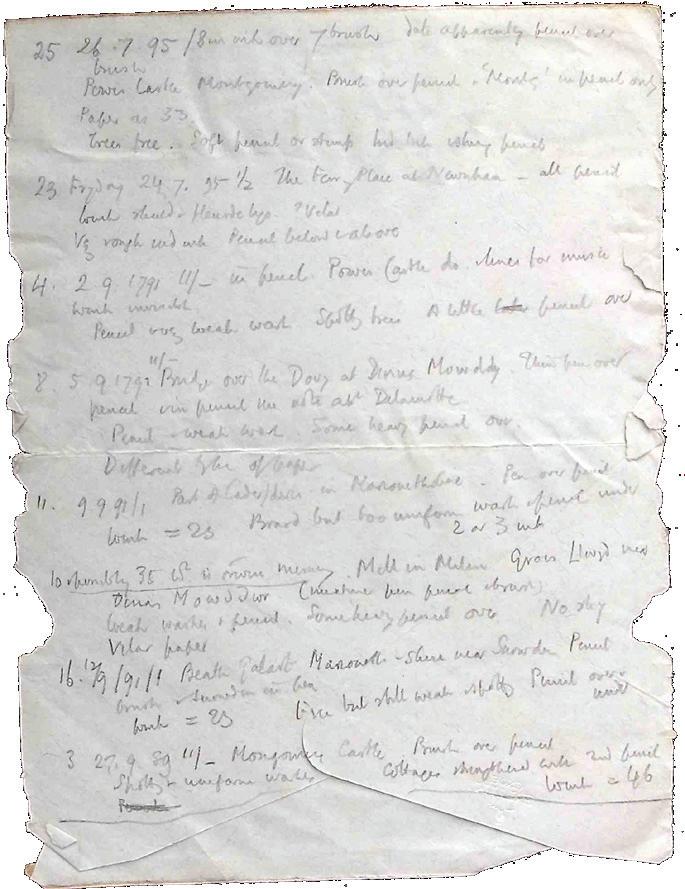

Oliver Millar [1] always travelled with elaborate, bound notebooks, creating a comprehensive record of everything he had seen. Others frequently resorted to more impromptu means of notation: leaves torn from an office notepad, or the back of an envelope [3, 4]. Many also attempted to create at least a rudimentary visual record of what they had seen, by making quick sketches of details, or the composition as a whole [1, 2]. These documents allow a glimpse into the working practices of art historians, and to reconstruct their first and spontaneous encounters with artworks.

3

Paul Oppé, Research Notes on Works by John Baptist Malchair. Spiral Notepad.

AR: APO/1/14/2

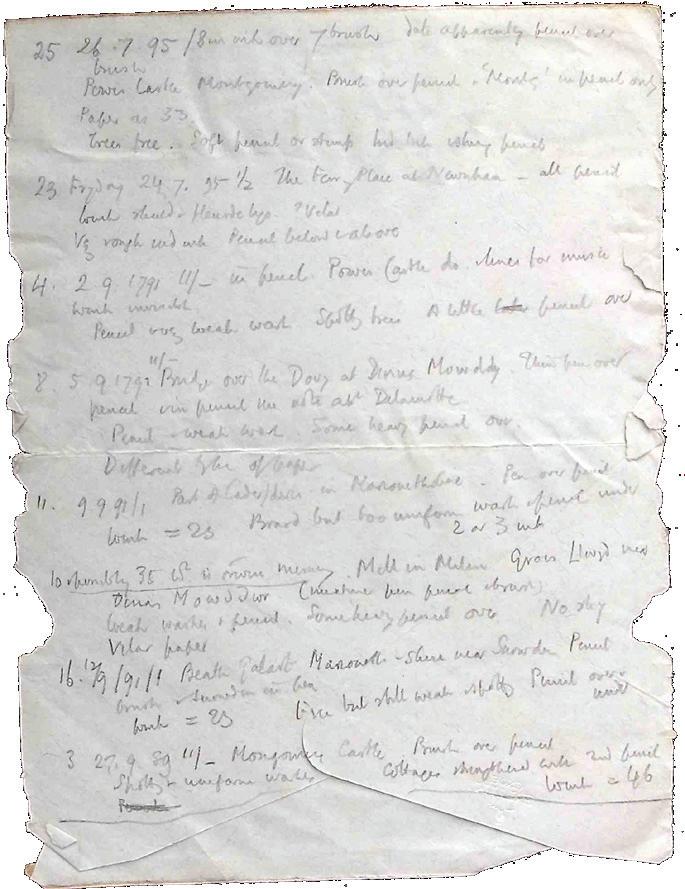

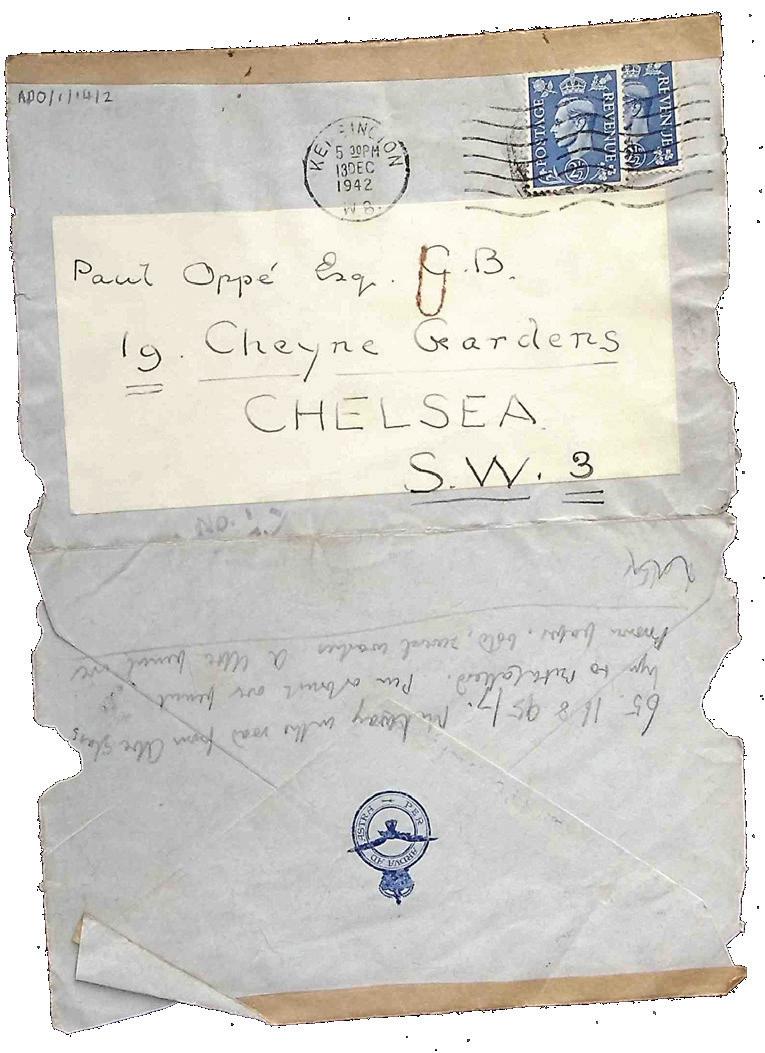

4

Paul Oppé, Research Notes on Works by Alexander Cozens, on the back of an envelope.

AR: APO/1/5/5

4

and back of

5 Front

Item 4

6 Front cover of Item 5

II. Close Looking and Connoisseurship

Among art historians, the qualities of the “connoisseurial gaze” have been hotly debated, especially since late nineteenth-century authors such as Giovanni Morelli aimed to professionalise connoisseurship and develop a “method” for attribution [5]. Some scholars insist on attribution as a scientific practice, based on virtues such as close looking and scrupulous study of detail, taking into account also technical analysis. This scientific approach is represented by a methodological intervention such as W.G. Constable’s “Art History and Connoisseurship”. Here, the first Director of the Courtauld Institute made a plea for connoisseurship as an empirical practice [7].

Other scholars, however, consistently highlight the necessity of a sudden personal connection between the artwork and the sensitive eye of the expert. In a review of Constable’s book, Ellis Waterhouse (the leading expert in the art of Gainsborough and Reynolds) criticised the author for omitting the “psychological process involved”, and the “spiritual struggle” between connoisseur and the work under scrutiny.

Most connoisseurs attempted to straddle both poles, aiming to integrate both deep contemplation

and sudden inspiration in their art-historical practice or as Kenneth Clark phrased it: “Looking at pictures requires active participation, and, in the early stages, a certain amount of discipline” [6]. This of course also implied that, once an eye is properly trained, the expert is equipped to make instantaneous judgement calls, based on an “embodied” experience. Clark’s conclusion seems that, to an educated eye, personal connection matters more than pedantic, prolonged study.

5

Giovanni Morelli, Italian Painters: Critical Studies of their Works (London: Murray, 1900).

LR: OPPE-1900-2

6

Kenneth Clark, Looking at Pictures (London: Murray, 1960).

LR: 7.01 CLA

7

W.G. Constable, Art History and Connoisseurship. Their Scope and Method (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1938).

Kindly leant by Hans C. Hönes

7

8

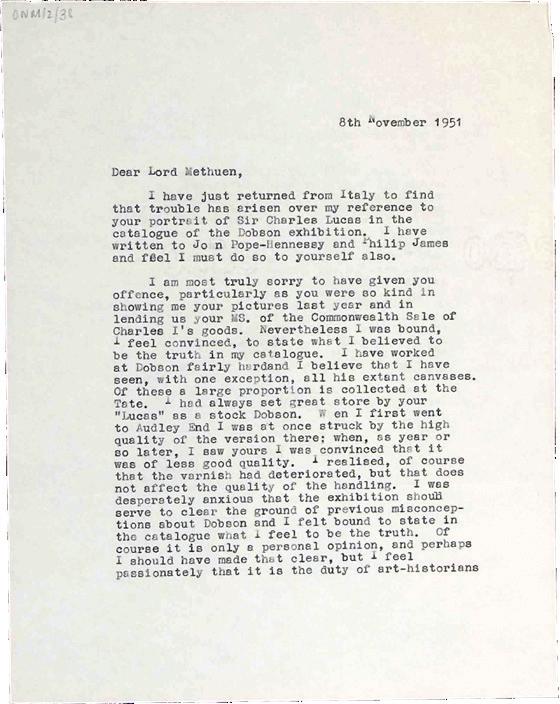

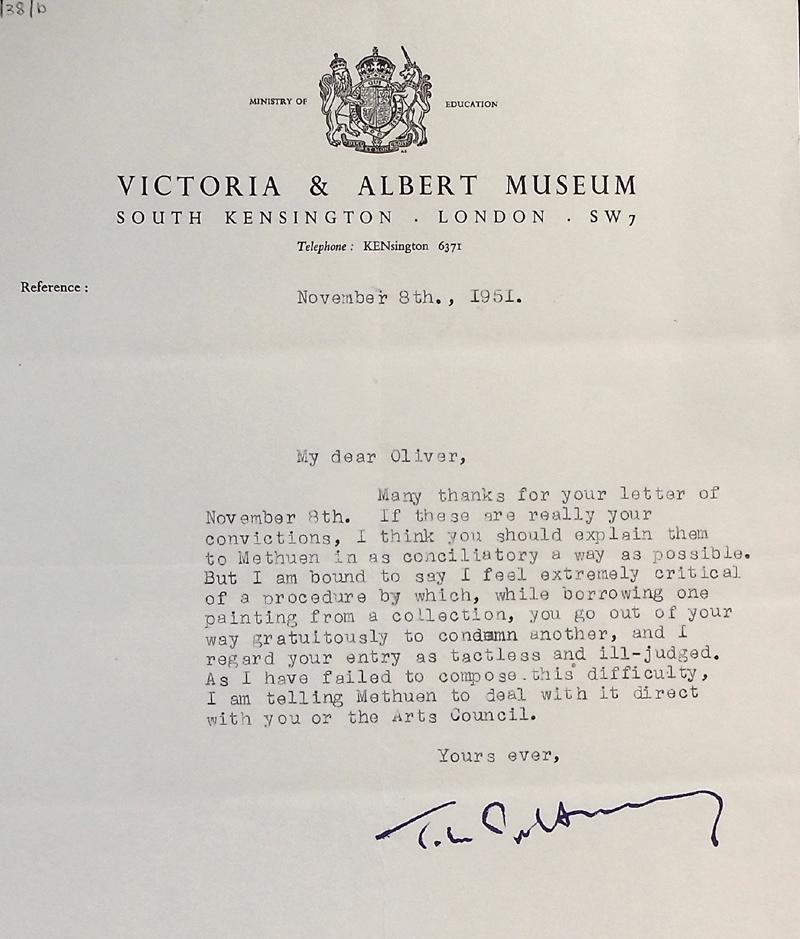

III. Controversies

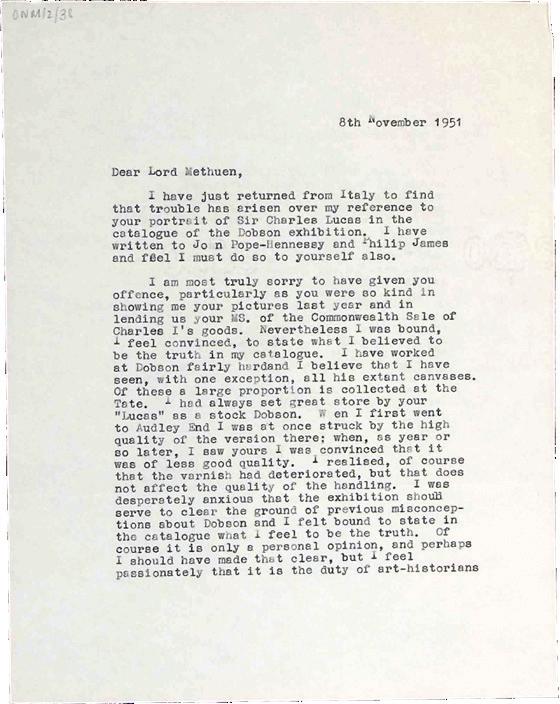

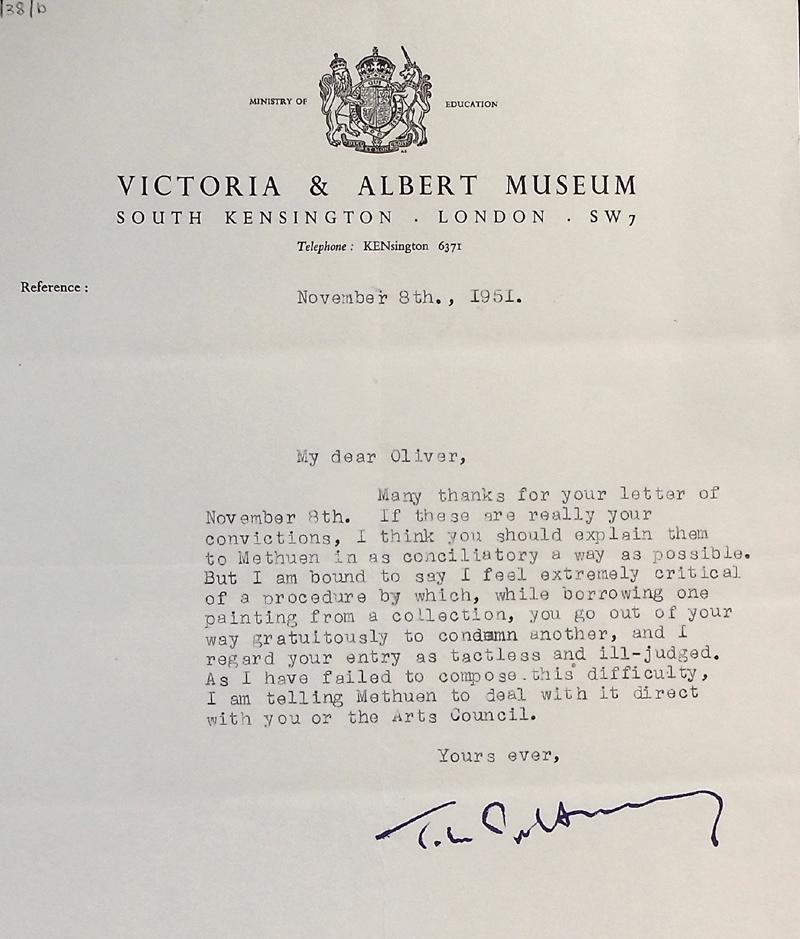

Questions of attribution are always questions of authority. For a long time in Britain, it was common practice not to challenge attributions of works in the possession of private owners: property rights trumped the legitimacy of scholarly enquiry. This unspoken rule led to many acrimonious controversies when challenged by art historians. This shelf documents one such controversy, sparked by Oliver Millar’s reattribution of a “William Dobson” in the possession of Lord Methuen [8]. Millar argued that “it is the duty of art-historians to put down what they honestly believe to be the truth” [9]; yet many contemporaries deemed this “tactless and ill-judged” [10]. Whenever a controversial attribution is made, the question of autopsy became crucial for contesting unwelcome attributions or interpretations. Among art historians, this was the perfect way to kick out the legs under one’s opponents: to claim that they have not, or not extensively enough, looked at the work in question—and thus arrived at wrong conclusions based on insufficient observation.

Perhaps Millar’s critics had a point: in his diary, he admitted that the visit to Corsham Court was “slightly hurried” [11]. This might have also been one of the reasons why, in a subsequent exchange of letters, Millar struck a more conciliatory tone and offered to re-visit Corsham Court, in order to look again and contemplate the work in question more thoroughly.

[opposite] Front cover of Item 8 [right] Item 9 9

Oliver Millar, William Dobson, 1611–1646: An Exhibition of Paintings at the Tate Gallery, 1951.

LR: 7 DOBS (PAMPHLETS)

9

Letter by Oliver Millar to Lord Methuen, 8 November 1951.

AR: ONM/2/38

10

Letter by John Pope-Hennessy to Oliver Millar, 8 November 1951.

AR: ONM/2/38

11

Oliver Millar, Journal VI, December 1949–June 1950: “Corsham Court (February 28th, 1950).

AR: ONM/1/2/6

10 8

11 [opposite] Item 10 [above] Item 1

12 Item 14

Small Display Case

IV. Looking Once, Looking Twice…

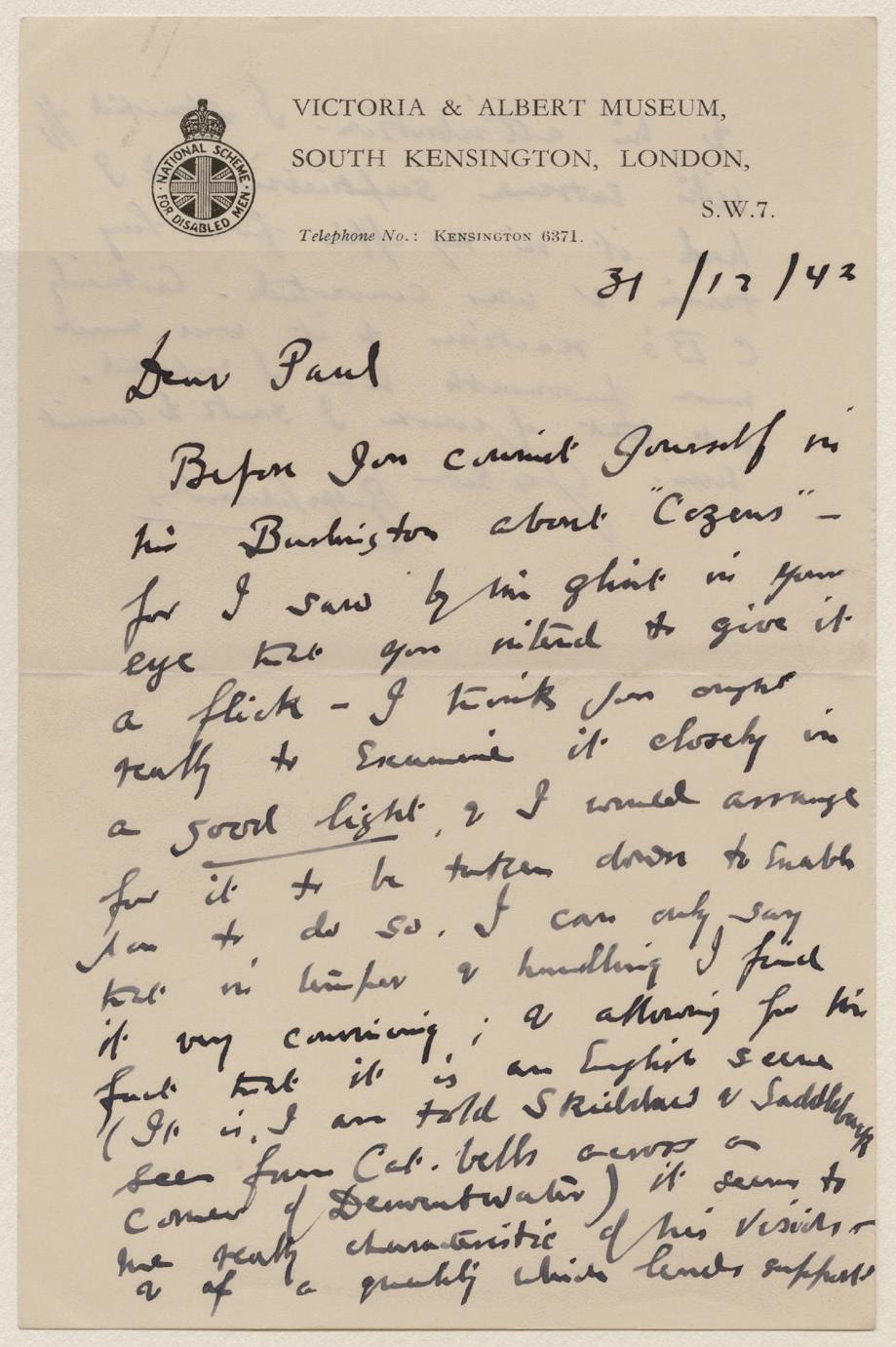

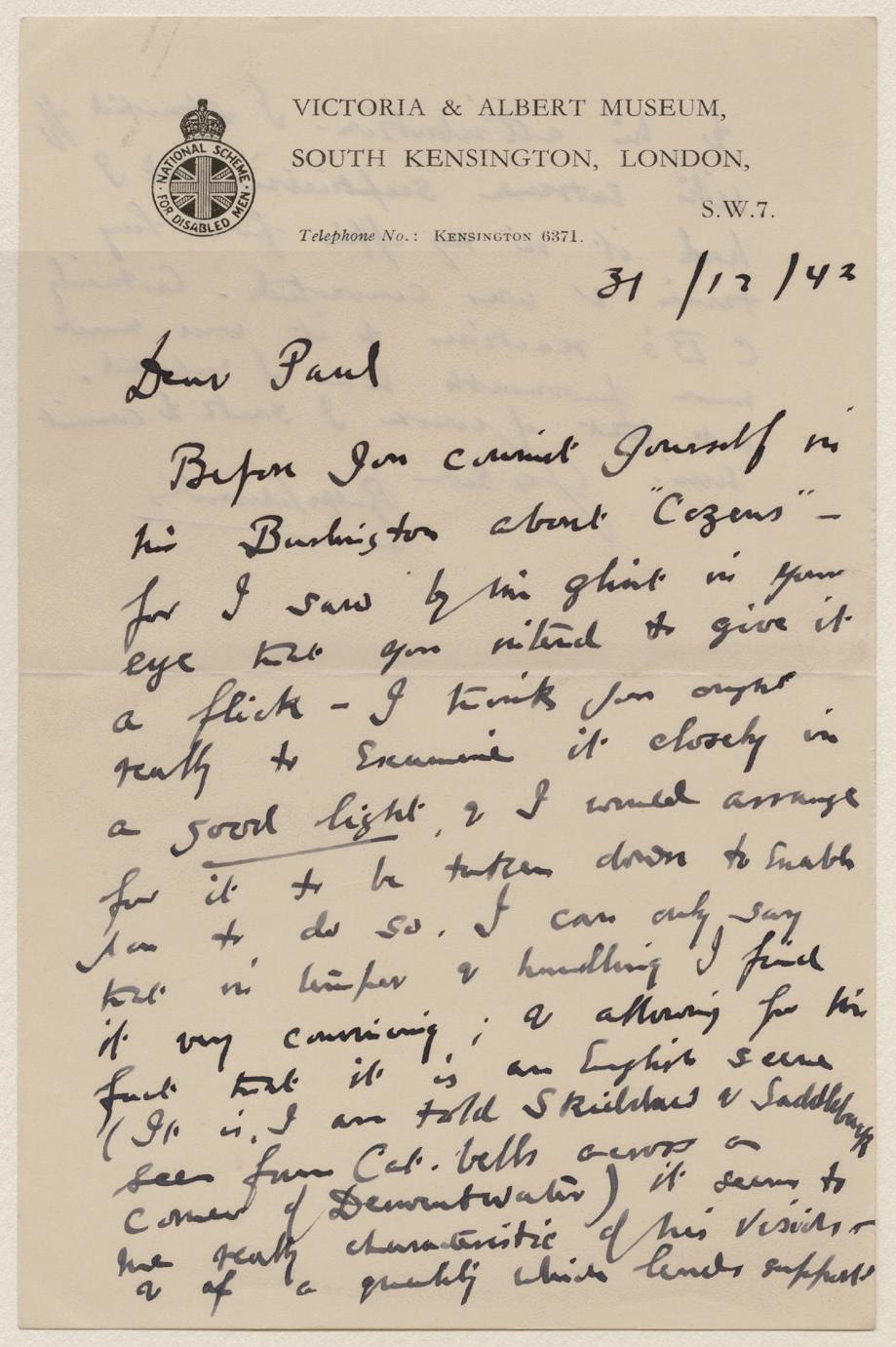

In practice, art historians see many objects of their study not just once, but repeatedly. Visit upon visit to print rooms and gallery floors refines their familiarity with key works and hones their judgement. Art historians hold repeated contemplation of works in high esteem. Especially in instances of disagreement, the plea to “look again!” is all too common. In 1943, Ralph Edwards (curator at the V&A) wrote to art historian Paul Oppé, urging him to look at a Cozens painting again “in good light”—in the hope that Oppé would revise his doubts about the painting’s attribution that he had voiced in an exhibition review for the Burlington Magazine [13, 14]

Surprisingly perhaps, few art historians have reflected systematically on this “layering” of visual impressions, and on the question of to what extent (and why) visual judgements might change over the course of time. John Berger, for example, discussed two visits to Grunewald’s Isenheim Altar, ten years apart [12]. Berger reflects on his changing opinions, but also highlights the extent with which this is bound up with a changing political and cultural landscape.

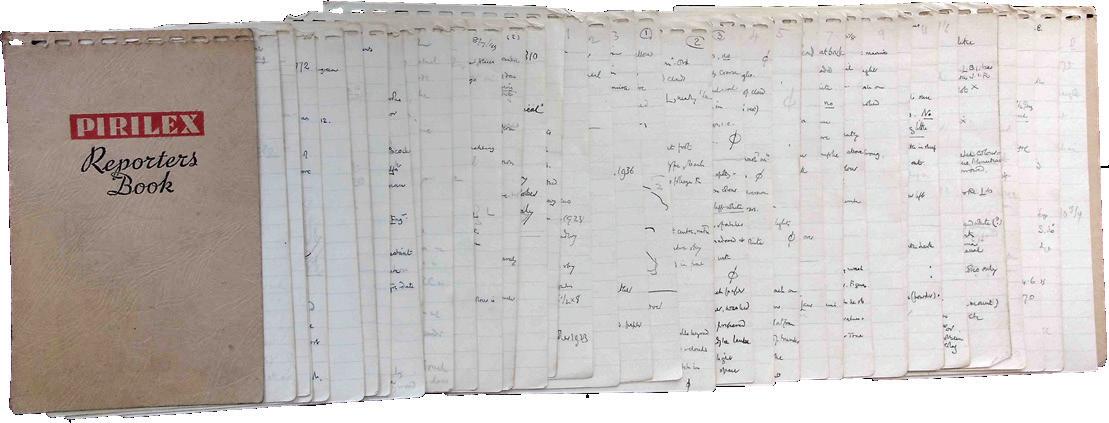

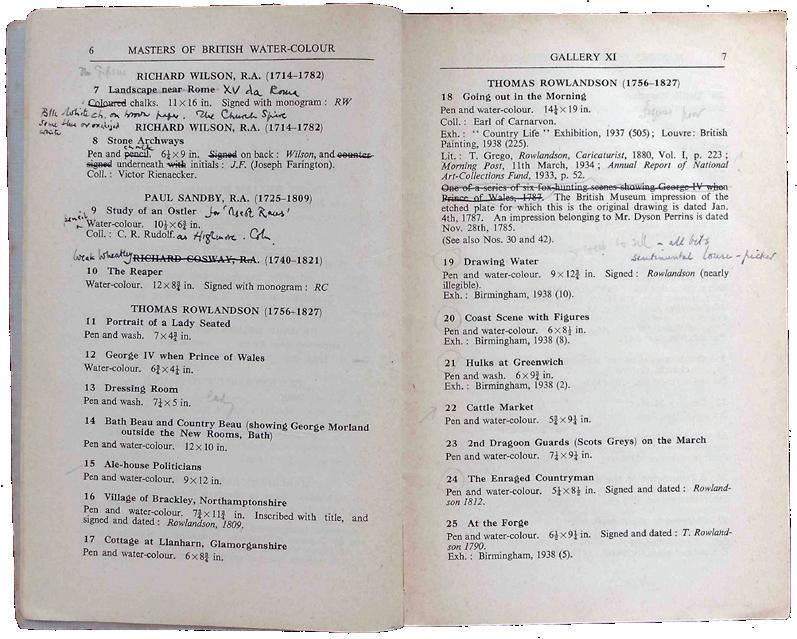

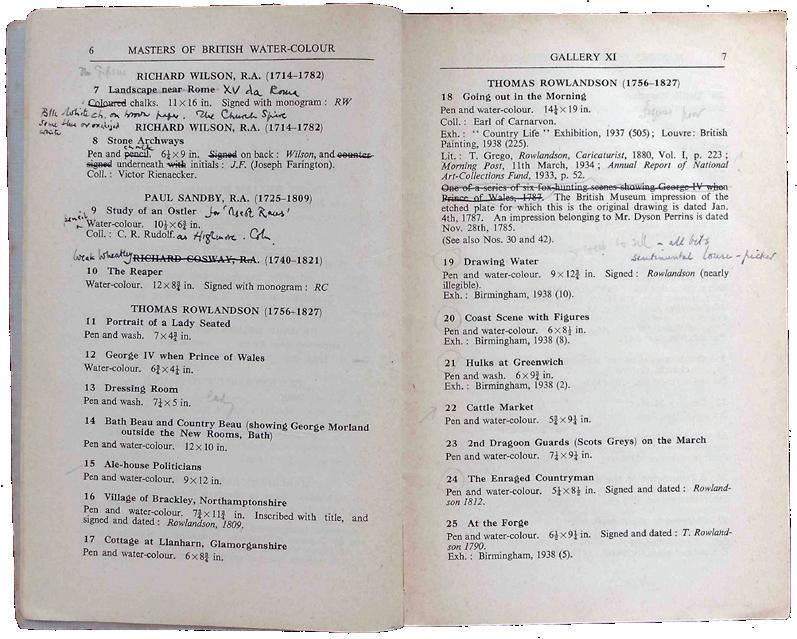

The working notes of art historians allow us to reconstruct said “layering” of impressions: we are able to gain archival glimpses on whether or not repeated viewing altered their opinions and, if so, how. In the Oppé archive, for example, there is a set of notes taken during visits to Sir John Soane’s Museum between 1947 and 1948, where Oppé studied works by Alexander Cozens [15]. Notes in blue ink are followed by pencil marks. Clearly, Oppé was not able to see certain details on his first visit (e.g. No. 5: “Back not seen”), which he made up for on later visits. Evidence for such repeat visits are also exhibition catalogues from Oppé’s collection: evidently, he visited certain exhibitions several times, adding new comments in the margins every time. Sometimes, he corrected himself on second sight [16].

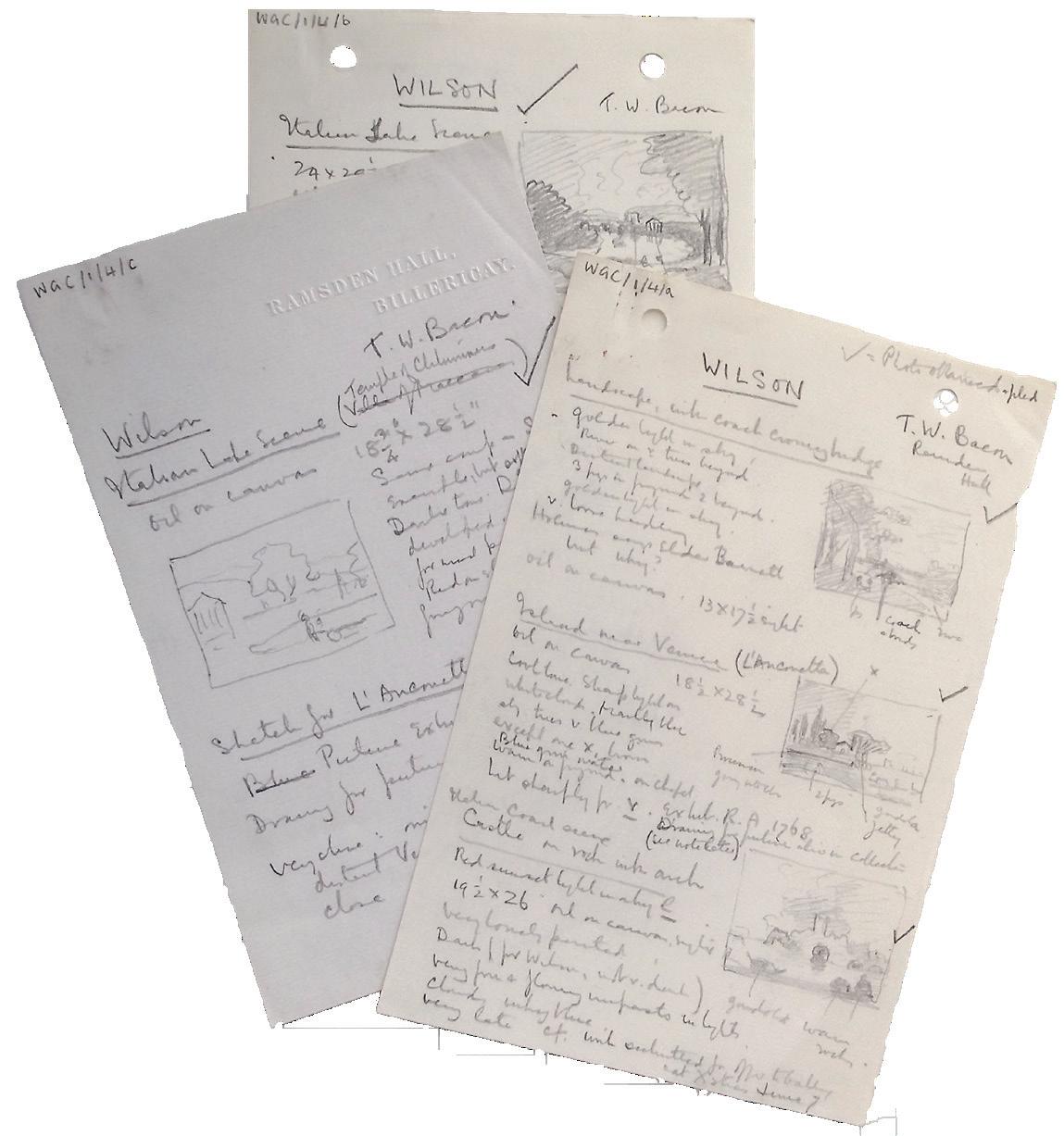

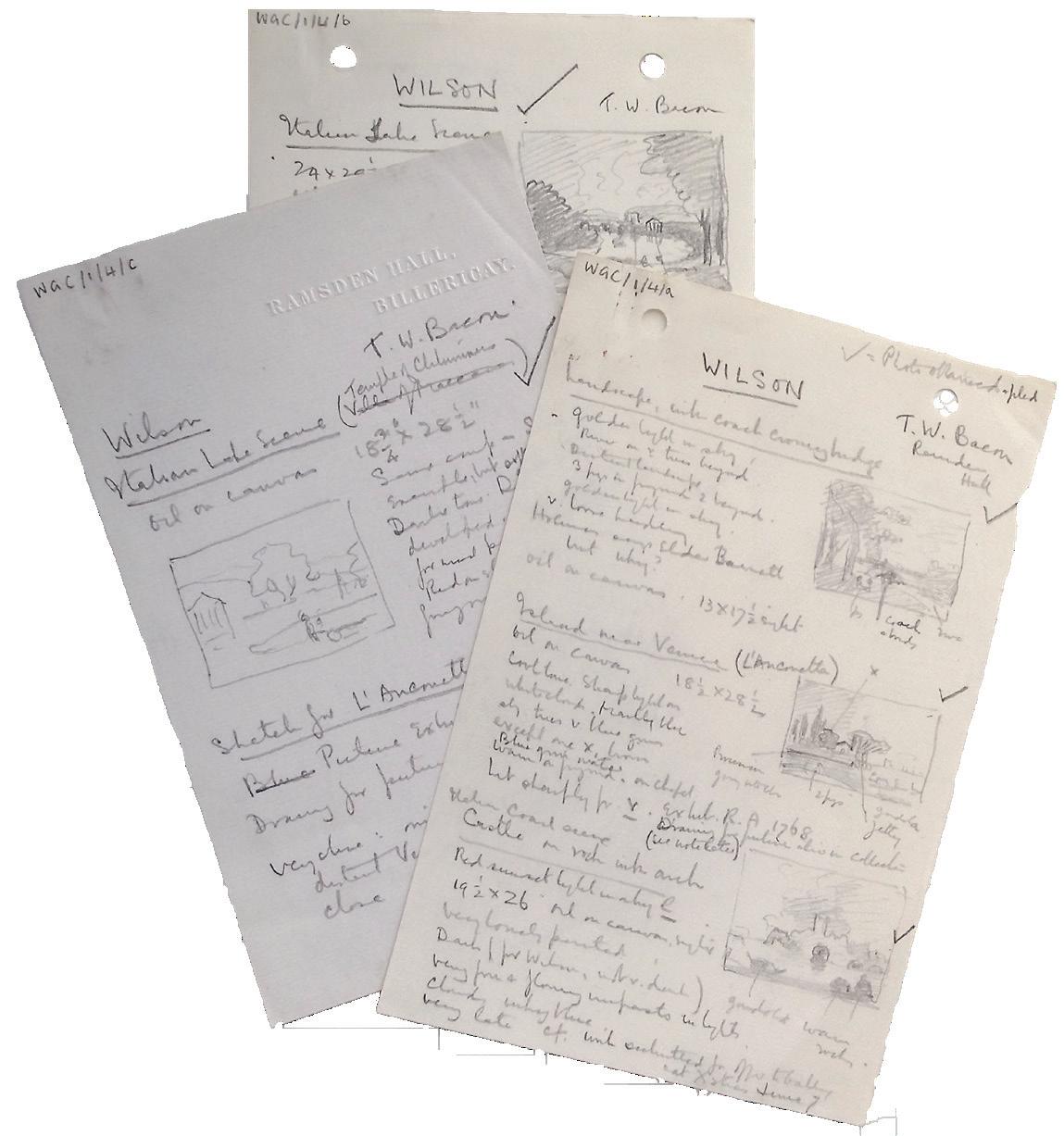

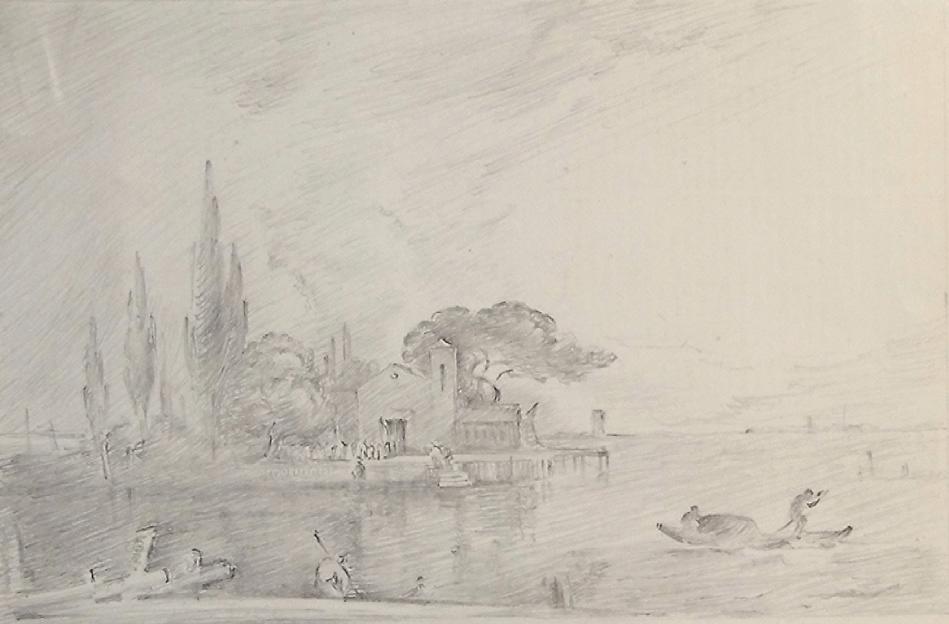

Others “outsourced” the problem of looking again: during a visit to Ramsden Hall, W.G. Constable made several drawings after a set of works by Richard Wilson [17]. Of most works, a “photo [was] obtained and filed”, as a little side note informs us. The art historian was now able to revisit the works (albeit in reproduction) from the comfort of his own study.

13

John Berger, “Between Two Colmars”, The Guardian, 17 April 1976, 9.

Kindly supplied by the British Library NEWS.REG1610

13

Paul Oppé, “British Landscapes in Oil at the Victoria and Albert Museum”, The Burlington Magazine, February 1943; clipping.

AR: APO/2/10

14

Letter by Ralph Edwards to Paul Oppé, 31 December 1943.

AR: APO/2/10

15

Paul Oppé, “Rough Notes on Soane Mus. Series”.

AR: APO/1/5/5

16

Annotated copy of Catalogue of the Exhibition of Masters of British Water-Colour (17th–19th Centuries):

The J. Leslie Wright Collection (London: Royal Academy of Arts, 1949).

LR: OPPE-1949-14

17

W.G. Constable, Notes on Works by Richard Wilson in Ramsden Hall.

AR: WGC/1/14/1

14 12

15 [opposite] Page 6-7 of Item 16 [above] Item 17

16

Large Display Case

V. Judging from Afar

For every art historian, autopsy of the original works of art they hoped to study is commonly considered an essential prerequisite, especially when questions of attribution are concerned. However, for many art historians, the objects of their study were not always easily accessible: some works are untraceable; others are located in remote locations.

For a long time, this proved an almost unsurmountable hurdle for the art historian; the situation only changed when photography became widely, and cheaply,

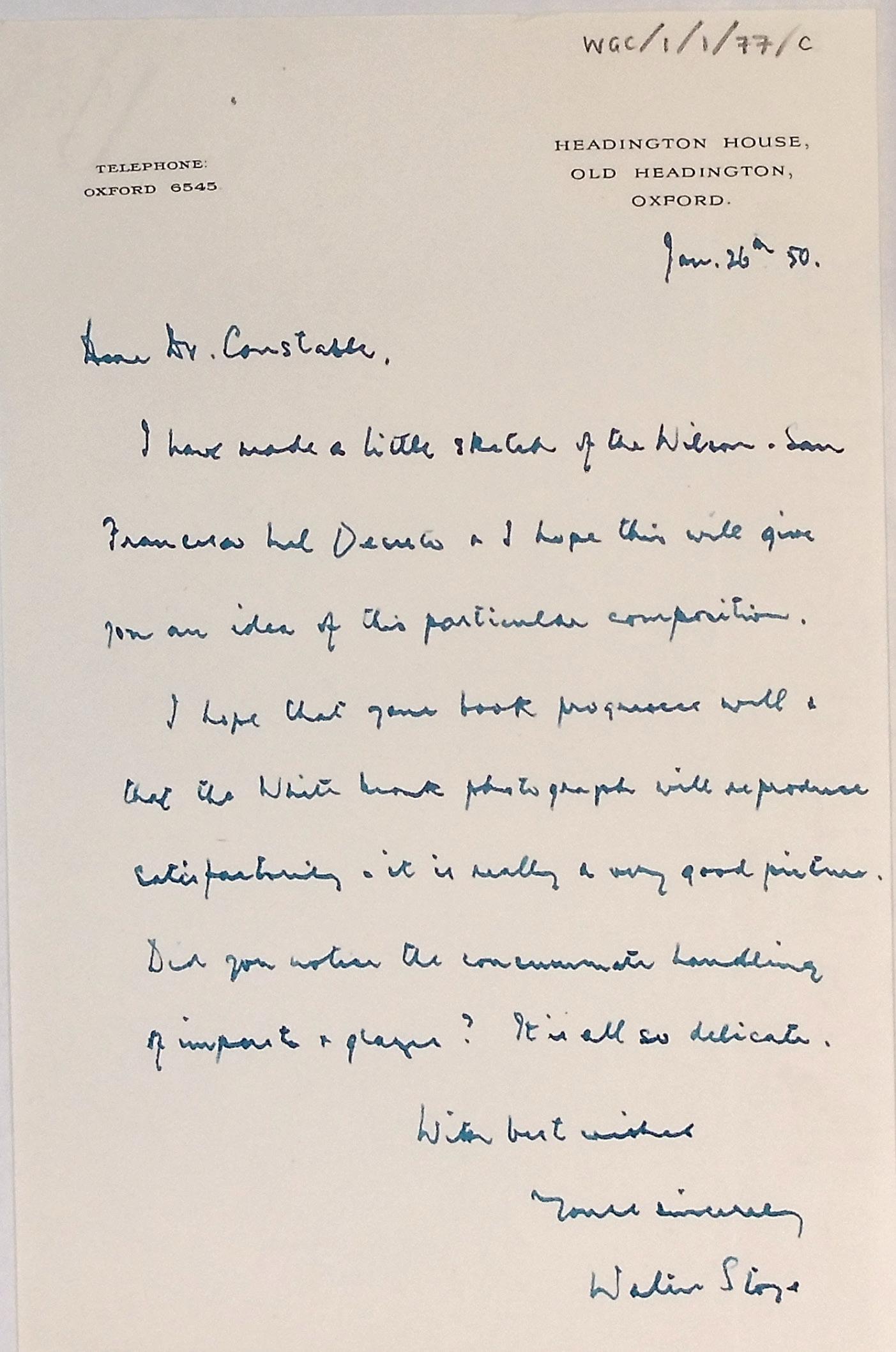

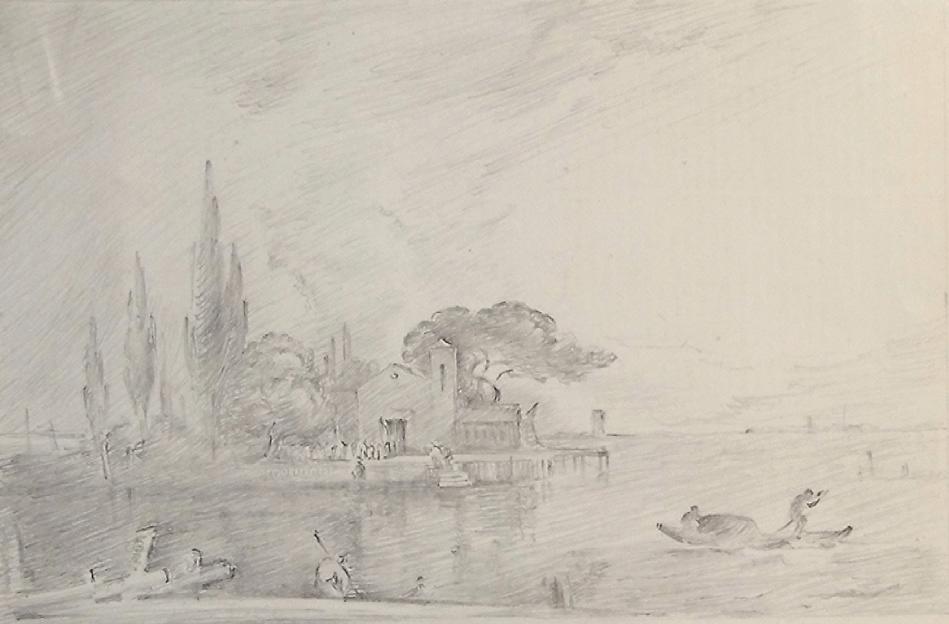

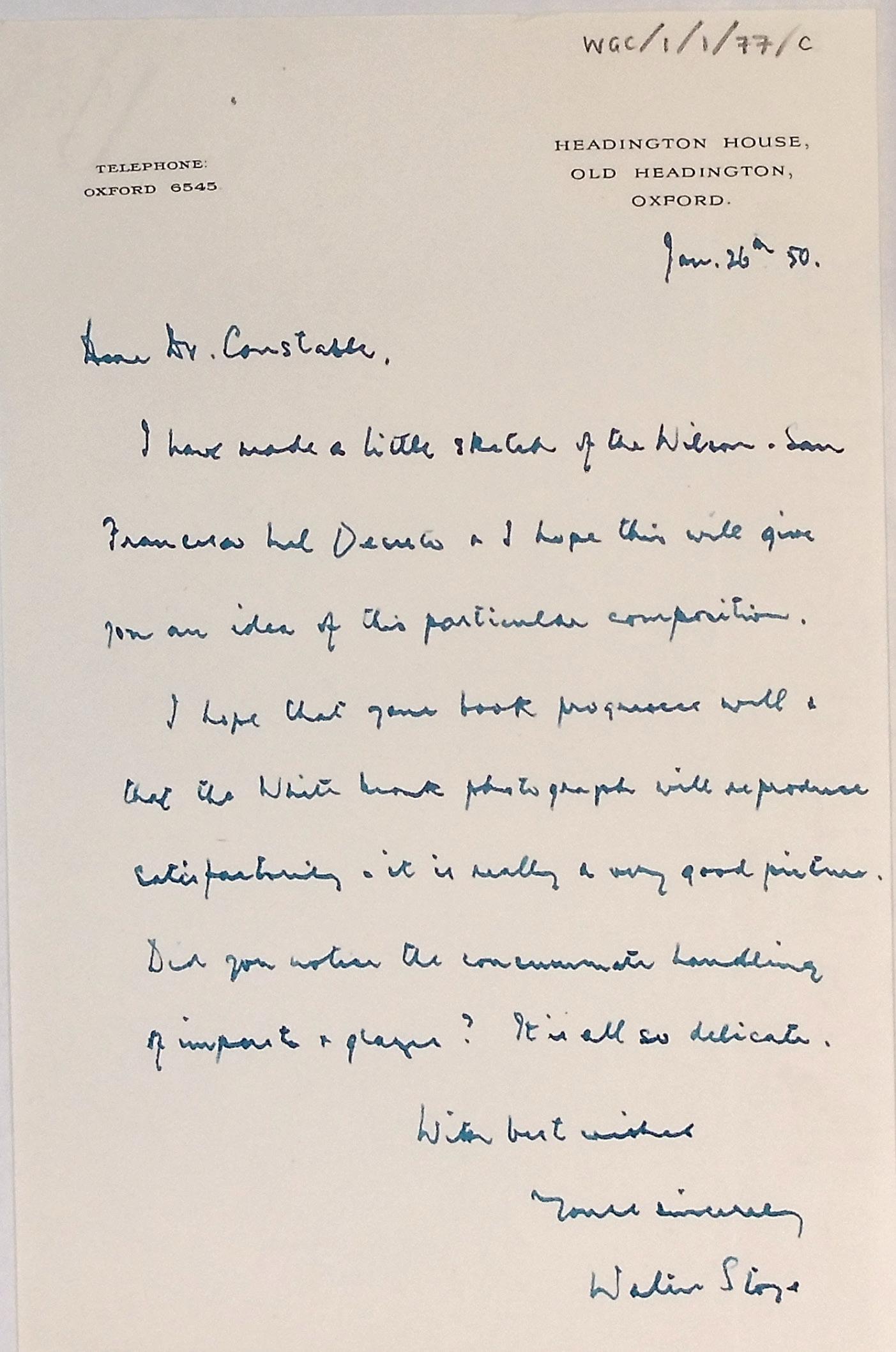

available. Until the 1950s, owners sometimes drew sketches of works in their possession, hoping to give an enquiring art historian a general idea of the work’s composition [18]. For questions of attributions, this was of course of little value.

Cheap photography was a true game-changer for art historians, and the discipline in its modern guise is indeed unimaginable without this technology. Now scholars were able to compile and compare visual evidence of a wide range of artworks, without having

17

[opposite and this page] Item 18

18 [above] Item 19 [opposite] Item 20

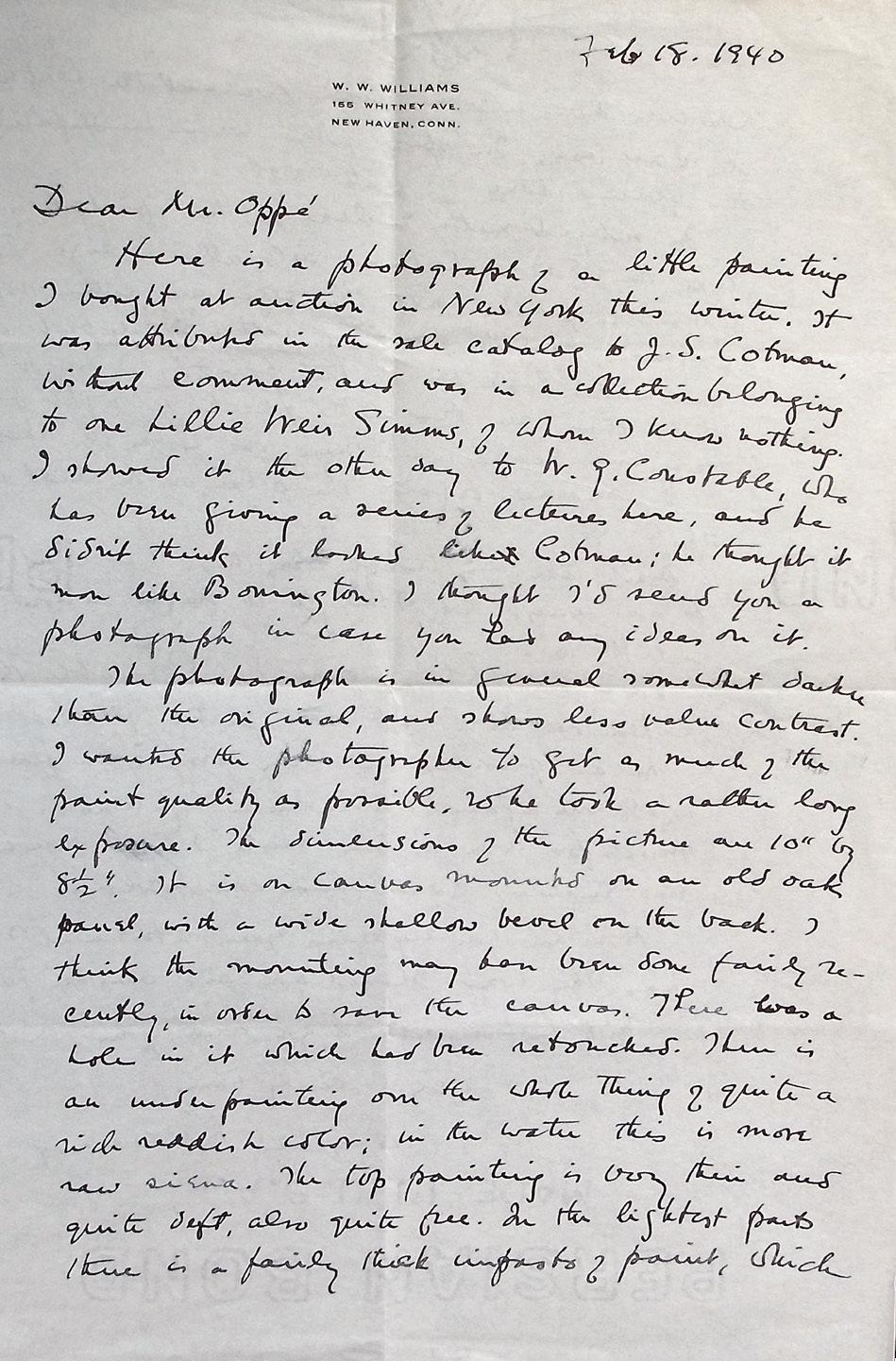

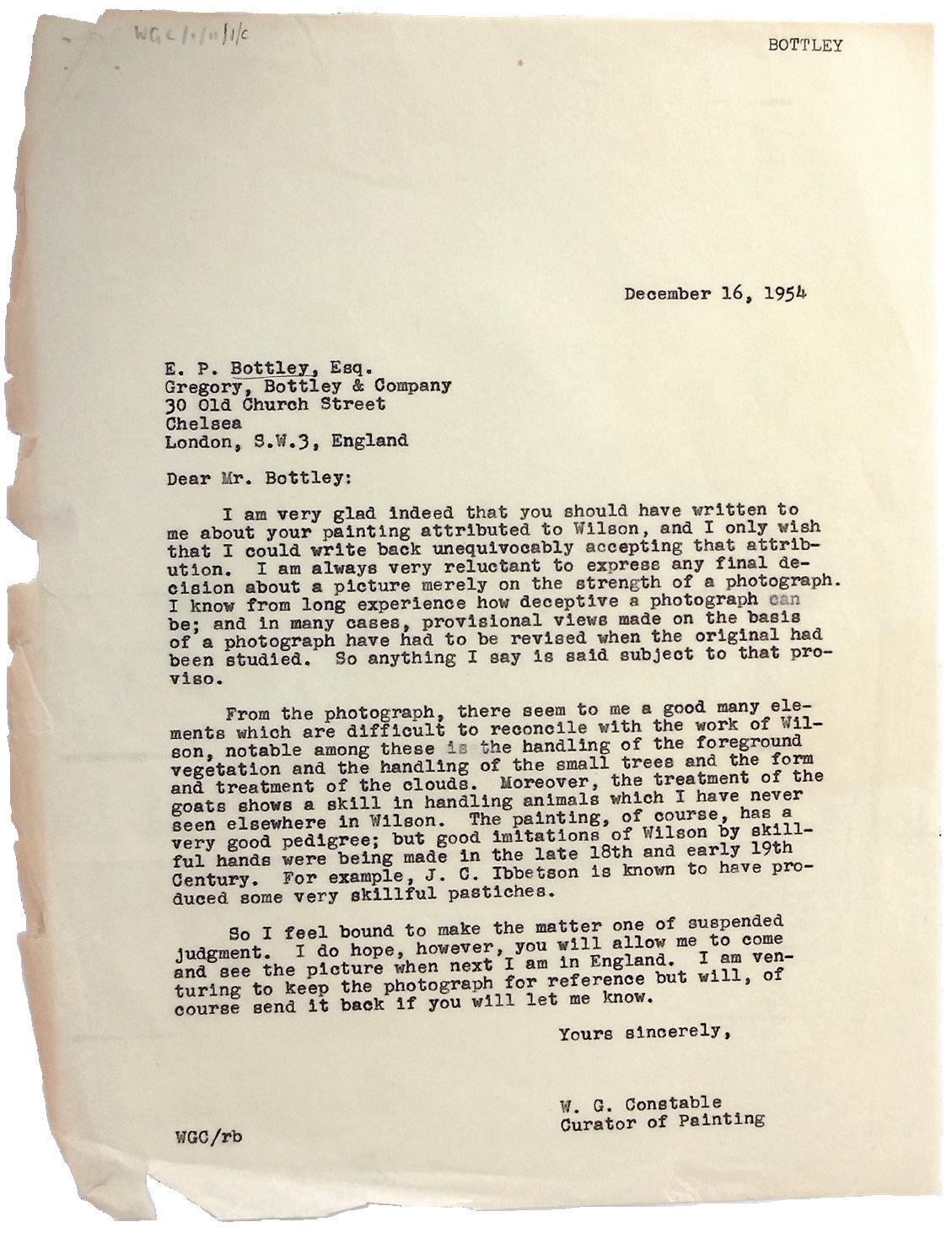

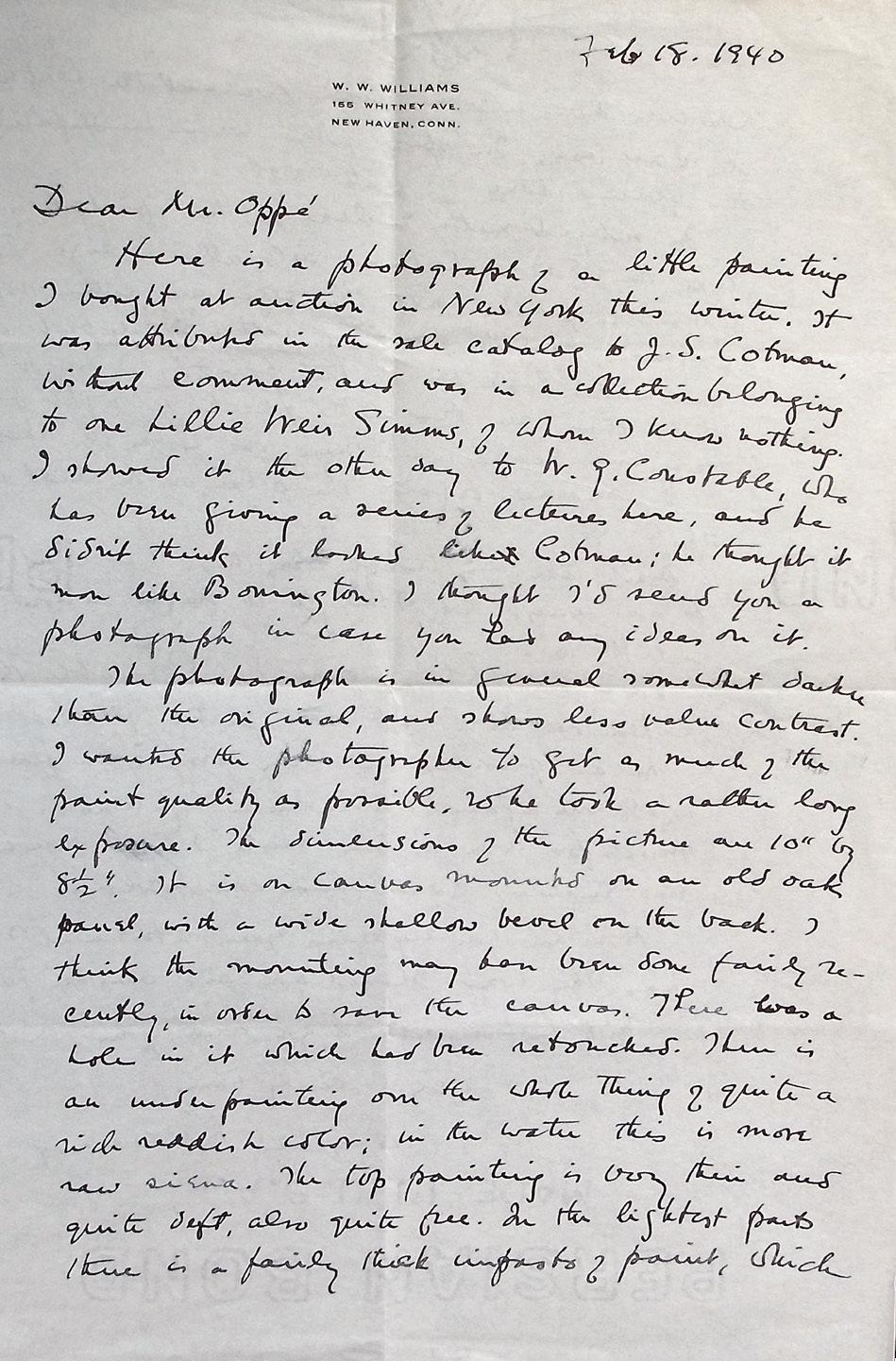

to rely solely on visual memory and notes taken in situ. But photography did not solve all problems. Many a time, only poor photographs were available, and they had to be supplemented with sketches of details such as signatures [24]. Many art historians thus thought long and hard on how to photograph paintings, in order to facilitate attributions. In a letter to Oppé , a W.W. Williams wrote: “I wanted the photographer to get as much of the paint quality as possible, so he took a rather long exposure”. But every photographic decision also had its downside; in this case, the photograph “is in general somewhat darker than the original and shows less value contrast” [21]. In the end, descriptions needed to supplement where the photograph failed.

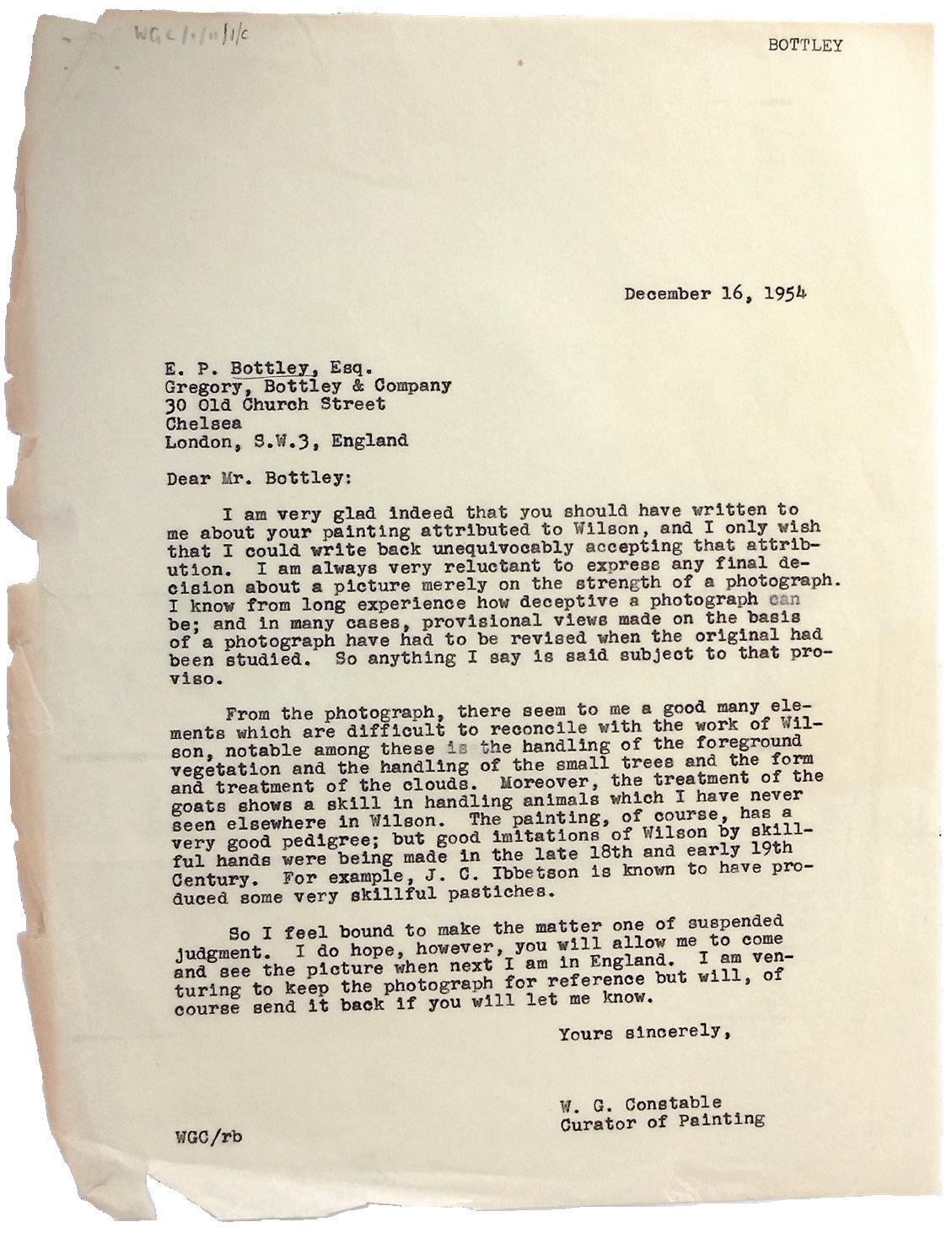

Many art historians were fully aware of the limits of photography. As W.G. Constable wrote, in 1954: “I am always very reluctant to express any final decision about a picture merely on the strength of a

photograph. I know from long experience how deceptive a photograph can be” [22]. In practice (and in the case of Constable’s letter exhibited here), however, many attributions were nevertheless made on the basis of photographs, some of which were of “revolting” quality [23]. Where such snapshots were deemed an insufficient base for reaching a verdict, the art historian needed to see the work

19

20

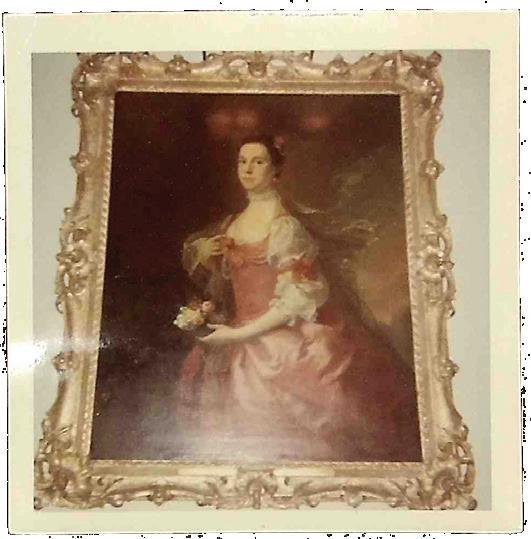

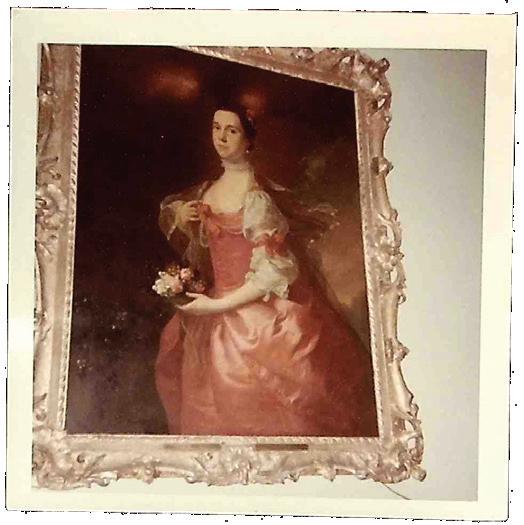

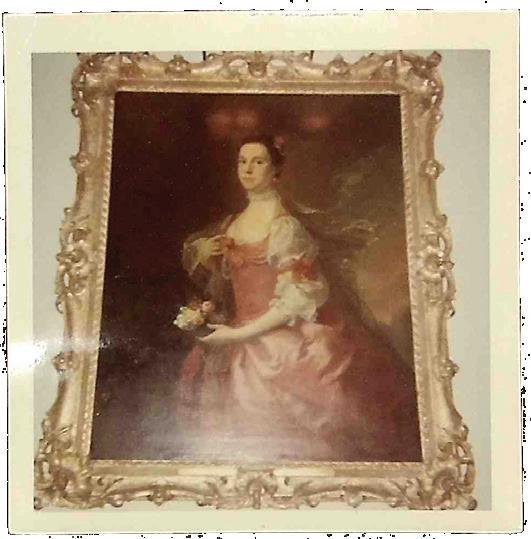

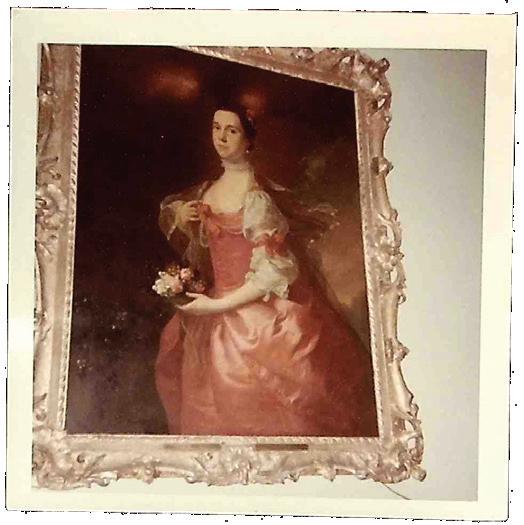

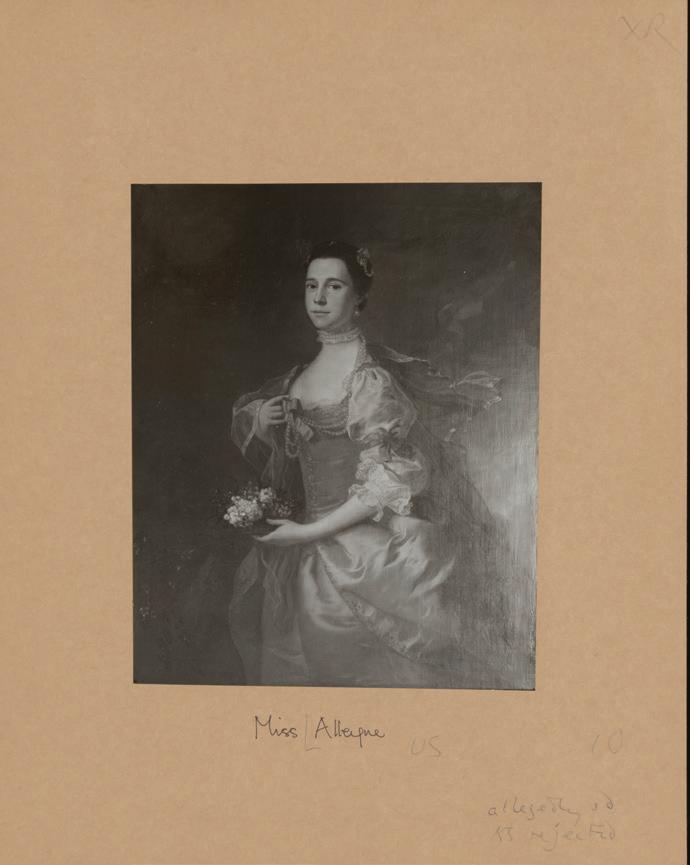

in person—or at least commission better photography. In 1968, for example, Alastair Smart’s interest in a work in a private collection in the United States was first sparked by a crude photograph taken by the owner who hoped the work in his possession was by the Scottish portrait artist Allan Ramsay. Smart then arranged for a professional photographer (paid, incidentally, by the Paul Mellon Foundation, the precursor of today’s Centre) to take better pictures [19]. High-quality photography finally allowed for a definitive verdict: alas, for the poor owner, it was negative.

18

Letter by Private Owner to W.G. Constable, 26 January 1950; with “little sketch of the Wilson”.

AR: WGC/1/1/77/13

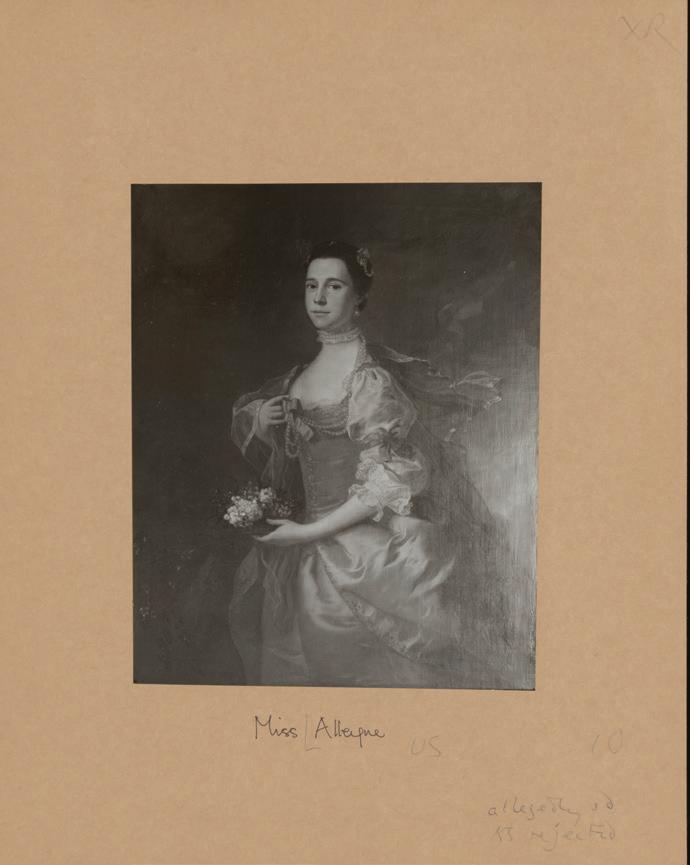

19

Letter by Alastair Smart to William Diebold, 6 June 1968; polaroids of portrait of “Miss Alleyne” (attr. Allan Ramsay; rejected by Smart), sent by the owner; professional photograph of the same.

AR: AS formerly Box 8

20 Allan Ramsay, Miss Alleyne, from the Paul Mellon Centre’s photoarchive. PA-F02448-0023

21

Letter by W.W. Williams to Paul Oppé, 18 February 1940, with “photograph of a little painting I bought at auction in New York this Winter”.

AR: APO/1/4/1

22

Lettery by E.P. Bottley, 16 December 1954. With photograph of painting in Bottley’s possession.

AR: WGC/1/11/1

[opposite & left] Item 21

21

23

Letter by Sidney Sabin to Ellis K. Waterhouse, 30 September 1957. With a “revolting photograph” of “quite a decent picture of Lady Cathcart”.

AR: EKW/1/307

24

Letter by Private Owner to W.G. Constable, 30 October 1949; with photograph and detail drawing of “R. Wilson’s painting of Lake Nemi”.

AR: WGC/1/1/100

[above & right] Item 22

22

Archives & Library Fellowship

Hans C. Hönes is a Lecturer in Art History at Aberdeen University. In 2021/22, he held the Paul Mellon Centre’s Research Collections Fellowship, with a project on British art historiography in the post-war period. He has worked extensively on the history of art history and art theory since the eighteenth century, and has written and edited books on Heinrich Wölfflin (2011), eighteenth-century antiquarianism (2014), Aby Warburg (2015) and art history and migration (2019), as well as publishing articles in journals such as Oxford Art Journal, Architectural History and Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte, among others. He has just completed his third monograph, a new biography of Aby Warburg (forthcoming with Reaktion Books).

Hans is the PMC's second Archives & Library Fellow, winning the award in 2020. For more information about this fellowship, visit https://www.paul-mellon-centre. ac.uk/fellowships-and-grants/ archives-and-library-fellowship

Acknowledgments

Display and text prepared by Hans Christian Hönes (University of Aberdeen / PMC Research Collections Fellow 2021/22)

The author would like to thank Mark Hallett, Martin Myrone, Charlotte Brunskill, Bryony Botwright-Rance, and Hannah Jones for their help in preparing this display.

Associated Events

Art History in Britain: A Scottish Innovation - A Research Lunch by Hans C. Hönes Friday 7 October

For more information and how to sign up to this event, please visit https://www.paul-mellon-centre. ac.uk/whats-on/forthcoming

[opposite] Item 23 24

26 The Centre is confident that it has carried out due diligence in its use of copyrighted material as required by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (as amended). If you have any queries relating to the Centre’s use of intellectual property, please contact: copyright@paul-mellon-centre.ac.uk For more information about our research Collections see our website: www.paul-mellon-centre.ac.uk. Alternatively contact us by email at collections@paul-mellon-centre.ac.uk or phone 020 7580 0311