WONDERLAND issue

“If I had a world of my own, everything would be nonsense. Nothing would be what it is, because everything would be what it isn’t. And contrary wise, what is, it wouldn’t be. And what it wouldn’t be, it would. You see?” Lewis Carroll, 1865

Tatted Tales

Quirky ink and even-quirkier stories

By Delaney Callaghan Photography by Sky Byun65-67 Urban Inferno

How are Europe’s cities struggling to adapt to the climate crisis?

By Chloe Elsesser68-73

Murder We Wrote

Is our obsession with true crime a ecting the course of justice?

By Blu Clara Rapps-O’Dea Valey74-77

From BookTok to Book Stores

How one social media platform revitalized the publishing industry

By Chandler Sumpter Gillyard78-80

Hip-Hop is Dead

Who is to blame for the long list of shootings in the rap world?

By Blu Clara Rapps-O’Dea ValeyLe er from the Editor

This past Spring, I took a class with an inge nious English professor who asked us to read Lewis Carroll’s “Alice’s Adventures in Won derland”. In one of his a ernoon lectures, this pro fessor asked us to try and identify why Alice felt so frustrated by Wonderland’s inner workings; the an swer to this sounds fairly simple, no? Wonderland is beyond normal—the embodiment of all things bizarre, a cultural metaphor for the weird and ex traordinarily creative. Towards the end of this dis cussion, my professor offhandedly made a simple suggestion, one that knocked 20 years of a false sense of perceptive superiority out of me—what made us decide Wonderland was abnormal? Is there such a thing as a standard definition of nor mality, given how uniquely we experience things as individuals? As paradoxical as it sounds to suggest that norms are, well, subjective, there is an ironic truth to the notion.

Two years ago, the entire world had to redefine the concept of normalcy overnight (not unlike Alice herself). If there were an award for the most com mon utterance of 2020, it would go to the phrase, “I can’t wait for things to go back to normal.” And yet, even though our lives have now detached from the pandemic for the most part, sometimes, as I’m fumbling with my keys, half-running out the door, I still instinctively look for my mask. Muscle memory:

all the “normals” we live through are stitched into the very fiber of our beings.

At AUP, the Fall 2022 semester saw the arrival of the university’s largest-ever incoming class, with 610 new students who now call Paris home. The li ing of government lockdowns led to a sharp in crease in tourism (133% compared to the previous year) as the world attempts to make up for lost time. As our societies become global again, our proxim ity and interactions with different cultures compel us to readjust our definitions and perceptions of what it means to be “normal.”

As students of a university that prides itself on its global outlook, it is our responsibility to look out side of our relative bubbles to empathize with those who don’t have the same privileges. This year saw the beginning of the largest armed conflict on the European continent since WWII, the overturning of a pivotal marker of reproductive rights in the U.S., catastrophic floods in Pakistan, mass protests in Iran, the continued occupation of Palestine—now more than ever, it is vital for us to forgo the notion of a normative standard, as the first step towards a more empathic global community.

Despite our differences, there is one thing we all have in common; although our definitions of each may be subjective, we dream of utopias, of peace and connection, and of a space that allows for ar tistic and intellectual freedom—a shared desire for Wonderland.

Every piece in this issue is bold in its attempt to reconstruct and defend subjective definitions of normalcy. Lola Rock explores the dynamics of be ing sober in a city that prides itself on its refined drinking culture. In an insightful article on partisan ship, Jacob Shropshire highlights the unusual ben efits of media selectiveness. Isaac Bates interviews four AUP students who march to their own drums, carving a path for themselves as creatives, outside the context of their academic careers. Elsa Lindner puts a unique spin on Parisian aesthetics, explor ing the city through the lens of Wes Anderson in a carefully curated photo essay. In a scathing critique of anti-abortion messages in the media, Delaney Callaghan draws attention to exactly why normal ization can be dangerous, stressing the importance of standing firm in your convictions.

I am beyond grateful to have created this maga zine alongside the most special, committed individ uals. To our readers: I hope this issue inspires you to stay fantastically unusual. Fiercely defend your right to question, define, and create your own nor mal—whatever that may be.

As ever,

I want to thank Marc Feustel, an absolute pillar of the magazine, for his guidance and steadying sense of ease. Thank you to Jacob Shropshire for his ground ing words of advice and stairwell tea sessions, and to Caroline Sjerven for keeping me from losing my head.

I am incredibly grateful to Sky Byun for stepping up when needed, and to the rest of the Peacock board for being incredibly driven, inspiring individuals (and a de-facto support group). And last but not least, to Mia Baccei for her remarkable artistic vision, rambling voice notes, and fierce dedication, without which this issue wouldn’t be nearly as astounding.

Photography by Malala SamirhaPost-Roe Propaganda

You won’t hurt me this time, will you?”

This is the question asked of Marilyn Mon roe (portrayed by Ana de Armas) by a CGI fetus in the latest Monroe biopic, Blonde. The film— directed by Andrew Dominik—and its use of this scene in which a glowy, photorealistic fetus begs the iconic actress for its life has sparked controver sy and conversation about the role of anti-abortion propaganda in film and other forms of media.

In a statement re leased to the Holly wood Reporter, Car en Spruch, Planned Parenthood Feder ation of America’s national director of arts and entertain ment engagement, said, “While abor tion is safe, essen tial health care, an ti-abortion zealots have long contribut ed to abortion stig ma by using med ically inaccurate depictions of fetus es and pregnancy. Andrew Dominik’s new film, bolsters their message with a CGI-talking fetus, depicted to look like a fully formed baby.”

Blonde’s release in theaters and on streaming gi ant Netflix this past September came almost exactly three months a er the U.S. Supreme Court’s deci sion to overturn Roe v. Wade and the constitutional right to abortion. The reversal, undoing nearly 50 years of precedent and subsequently jeopardizing the health of millions of women, and the ensuing

By Delaney Callaghancontroversy have barely had time to settle. And yet, in the wake of this critical reversal of a long-stand ing pillar of reproductive rights, anti-abortion mes sages have found themselves at the forefront of our screens.

It’s important to note that one of the most sig nificant aspects of the overturning of Roe was the Supreme Court’s refusal to take public opinion into consideration. As of July 2022, 62% of Americans said that abortion should remain le gal in all or most cases. Similarly, 57% of adults in the U.S. disagreed with the court’s deci sion, according to the Pew Research Center. The center also found that a majority of regis tered voters (56%) said the issue of abortion would be very important in how they cast their votes in the fall 2022 midterms. It is clear that abor tion is an issue at the forefront of many minds in the U.S., but the de cision ultimately made by the court was incredibly discordant with the sentiments of the majority.

However, while critics of Roe may only repre sent the minority, some students like Morgan Rose, the vice president of ReSisters (a club dedicated to facilitating an open conversation on feminism at AUP) are all too familiar with anti-abortion dialogue in all forms of media and have even seen an uptick

is the media normalizing the controversial overturning of roe v. wade?

in pro-life content in recent months. “I’ve seen a lot of anti-abortion rhetoric on social media,” said Rose. “There’s an extreme that it goes to in produc ing something inaccurate, and not even real. It’s just shocking.”

Blonde is certainly not the first instance of an ti-abortion propaganda in the media. Unplanned (2019) retells the story of Abby Johnson, a former Planned Parenthood clinic director who went on to become an anti-abortion activist. The film—based on Johnson’s memoir of the same name—contains several embellished plot points that, intentionally or not, misconstrue informa tion about abortion proce dures as well as their over all safety. This past April, shortly before the dra of the Supreme Court’s ma jority decision to overturn Roe was leaked, family YouTubers Cole and Savan nah LaBrant released a vid eo titled “Abortion. (docu mentary).” In the video, the LaBrants claim to portray a “pro-love” message rather than pro-life or pro-choice but then go on to share harmful anti-abortion content, going so far as to compare the number of lives lost in the Holocaust to the number of abortions in the U.S.

Such media pushes a harmful narrative that de monizes both abortion and those who utilize the procedure. Blonde attempts to use abortion as a device to portray Monroe’s fragile emotional state; Unplanned and the LaBrant family exploit a mor al high ground argument that looks to evoke guilt and shame from viewers. This kind of anti-abor tion rhetoric has previously been limited to seminiche online communities and low-level Christian film production companies, but Netflix’s distribu tion of Blonde is one of the first instances in which anti-abortion messages are amplified on a major

streaming/production platform. Thus, the turning point that Blonde represents is the anti-abortion movement coming into a moment in which they feel they finally have the power. Where the efforts by the LaBrant family and Unplanned were attempts to win the battle, Blonde shows us what happens when the minority wins the war.

This idea of giving a misleading sense of empow erment to the minority is an issue that weighs heavily on AUP senior Morgan Smith’s mind. As the president of ReSisters, Smith would hard ly say she shies away from a conversation on controver sial topics. However, since Roe’s overturning, Smith has felt a definite shi in dy namics between opposing ideologies, “I couldn’t count on my hands and toes the number of DMs I received from people telling me that I should take my social me dia posts down, or telling me that this was ‘ungod ly’ and wrong,” said Smith. “When you give somebody the platform, they take it. By overturning Roe v. Wade and giving this minority population the microphone, they become the majority, because they’re like, ‘The Supreme Court just decided it was OK to overturn abortion, so we’re actually just going to keep speaking on this.’”

Perhaps it’s less of a question of if we’ve adjusted too quickly, but rather an acknowledgment of what happens when the microphone is given–to put it in Smith’s terms—to a side that represents the beliefs of the minority. And then, at the core of the ac knowledgment, sits the concern of normalization.

Roe represented 50 years of legal precedent in the U.S. that was overturned in a single day. A pivot from previously pro-choice themes o en appear ing in movies and TV (see: “The Handmaid’s Tale”, “Plan B”, Unpregnant, “Jane the Virgin”, etc) places

Thus, the turning point that Blonde represents is the anti-abortion movement coming into a moment in which they feel they finally have the power. Where the LaBrant Family and Unplanned were efforts to win the battle, Blonde shows us what happens when the minority wins the war.

us in uncharted territory in which audiences are wit nessing a change in messaging from studios. The formidable influence of the media should never be overlooked—an increase in anti-abortion messag ing has the potential to lure the public into a sense of acceptance surrounding the decision.

Questioning the implications of normalcy and un derstanding how to combat false media messaging only sends us further down the rabbit hole, leading to chicken-egg debates such as whether the public affects the media or the media affects the public.

Supreme Court decision. However, the possibili ty of normalization looms constantly on the hori zon, hidden behind thinly-veiled and belligerent attempts at persuasion in the media we regularly consume. Avoiding media that pushes harmful and inaccurate information about abortions and sup porting other media that portrays the issue more accurately are crucial actions in reaffirming the feeling of the majority. Defiance, now more than ever, is critical in resisting the decision imposed on the population and preventing us from falling into a subdued sense of acceptance.

“I will say that I have seen people step up and even put themselves at risk,” said Smith. “A lot of people say that they’re willing to do things that could land them in jail because they want to help other people– I think that does show the resistance and force behind people, saying ‘Fuck you, we’re going to have abortions.’”

Rose takes the stance that it is the people who affect the media, for better or worse. “I think it’s im possible to separate human emotions and human sentiments towards certain subjects, because we’re the ones writing it,” said Rose.

On the other hand, Smith would argue that the opposite is true; going even further to cite an ex ternal (o en unseen) influence that possesses more control over both the media and the public than we may care to admit. “The media has the power be cause they get to control all of what we see on TV, online, and in newspapers every single day. All day long, we just take in what other people are putting out,” said Smith. “And while the majority of public opinion may believe one thing (you know, like sup porting abortion) because the media is in charge— and honestly, whoever pays their bills—they get to decide whatever they project.”

Drawing the simplest conclusion that we can, it would seem that we haven’t adjusted to the recent

Defiance, now more than ever, is critical in resisting the decision imposed on the population and preventing us from falling into a subdued sense of acceptance.

SOBER IN THE CITY

maintaining

europe’s booziest

capital

Like many Western countries, France places a bottle of alcohol at the center of its social sphere. Leading Europe as the highest con sumer of alcohol, the French drink more glasses per capita than any of their continental counterparts. But what makes the country’s drinking culture unique is not how much, but rather how they drink. The Par is we see today is focused on achingly-trendy wine bars, natural wine, and caves à manger, which line the streets of the Right and Le banks. Day and night, Parisians of all ages and backgrounds can be seen standing outside these bars and restaurants with a glass in hand, talking the night away and creating a sense of community around the bottle. Standing with a glass in hand is what many consider the perfect pastime. Unlike other cities, drinking in Paris is not just about the buzz; sharing a drink is a deeply rooted social and communal activity to en hance conversation and connection.

Drinking in France begins at home, around the dinner table with your parents. Because it’s intro duced so casually at a young age, it’s appreciated not as a tool to get drunk but as something that complements a meal. Wine doesn’t dominate the experience of a meal; it’s neither the main char acter nor a supporting act. Instead, wine and food are meant to elevate each other. Like croissants or cheese, wine is an integral part of the Parisian iden

By Lola Rocktity. Wine tasting, natural wine bars, and fine mix ology are true areas of personal interest for many Parisians, and drinks are a deeply integrated part of the culture.

your sobriety in

Standing with a glass in hand is what many consider the perfect pastime. Unlike other cities, drinking in Paris is not just about the buzz; sharing a drink is a deeply rooted social and communal activity to enhance conversation and connection.

At least in Western societies, consuming alcohol excessively has long been considered a significant part of the college experience. Media por trayals of frat rows, wild parties, and keg stands are commonly associated with the American college experience. Alcohol is widely acknowledged as a way to let go, make friends, and ease anxiety.

As young people today approach adulthood, Gen Zers have taken it slower than their elders, choosing to either abstain from alcohol entirely or drink less o en and in smaller quantities. Results from a study published by the European Journal of Public Health verify the decline, especially within high-income countries throughout Europe. A study by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) suggests that this trend was amplified even further during the COVID-19 lockdowns, when many young people were removed from their social environments.

Isabel, a student at the American University of Paris (AUP), began feeling sober-curious at the start of the pandemic. She says, “I think at the beginning of college, I used alcohol a lot just to cope with the pandemic environment and honestly bore dom.”

Isabel and other young people are trying to rede fine what it means to have a “good night out.” Pan demic stress, along with financial and social pressures, are among the main factors identified by researchers as causes of the decline in interest in drinking. A 2016 study by Espad (European School Survey Project on Al cohol and Other Drugs), revealed that regular alcohol consumption had decreased by more than 30% among French high school students since 2011.

Heightened knowledge of health risks also factors into this decline. For younger generations, learning is highly accessible through social media, primarily through on line communities like #SoberTok. Such platforms are al lowing Gen Zers, who live in alcohol-centric cities like Paris, a safe space to foster support and connect with like-minded people of a similar age.

Isabel spoke about the physical effects she felt drink ing was taking on her body. “I never thought I had a real problem, but a er a while, I got tired of how my body was feeling. I wouldn’t wake up sometimes until the end of the workday because I was tired, and it led to me fall ing behind in school.”

Sara, a senior at AUP, spoke about her experience with sobriety, stating, “I abstain from drinking for religious rea sons, so it’s all I’ve ever known.” When asked about how her social life is affected, Sara added, “I love trying a new restaurant with friends and going out to dinner. You can feel the energy of people in a restaurant rising through out the night. It doesn’t bother me, but I do notice it.”

Fortunately for sober Parisians, the mocktail trend is rising, and bars are now beginning to mix and make space on the shelf for low-alcohol and al cohol-free drinks. Today, bartenders are beginning to apply their mixology knowledge to non-alcohol ic beverages and are working even harder to unveil sophisticated recipes that provide an equally great experience. You no longer need to get a “fancy” soda, fruit juice, or a bland glass of sparkling water.

Le Panon Qui Boit (The Drinking Peacock) is the first non-alcoholic wine and spirits store to open Paris. Located in the 19th arrondissement, the store opened in 2016 and is paving the way for non- and low-alcoholic beverages, also offering an extensive range of exciting sodas and kombuchas that could serve as a fun non-alcoholic alternative.

Augustin Laborde, the owner, explained what led him to open the store saying, “I’ve been sober for 15 years. I used to try and find zero-percent alco hol on my own, but it’s not that easy to buy here. I wanted to open a place where people could access all the options in one place to make it easy.”

Le Panon Qui Boit showcases cutting-edge non-alcoholic wine and beer companies worldwide and focuses on the innovation ever-present in the French wine-making community.

Bars and clubs have also begun to mix and serve some non-alcoholic options, trying further to in clude the sober community in Parisian nightlife. The famous nightclub Pamela in the 6th arrondissement is one of many establishments developing creative mocktails. The bartender told me about the impor tance of mocktails and why the bar thought they should be added to the menu, saying, “We have

13 non-alcoholic options for our customers. We feel we should offer the same number of mocktails as the number of [drinks] with alcohol. Some are adapted off the regular menu, and some are new to this menu.”

Mocktails have also become increasingly popular not only with fully sober people but also with those who are looking for a dry night out. “We have many people order the non-alcoholic cocktails; people tell me they come here because of our options. I sometimes drink them too when I’m working, be cause I don’t drink actual alcohol with the custom ers until later in the night,” added the bartender at Pamela.

The drinking culture in Paris is changing, pulling further away from the alcohol itself and focusing on wine-and-spirits’ creativity and social importance. By adapting and welcoming non- and low-alcohol ic beverages into a longstanding traditional culture, Paris is beginning to reflect the changing outlook on drinking. Creating a more accessible community for non-drinkers has allowed a focus on innovation and creativity within the non-alcoholic world.

This shi in focus is, in many ways, more French. Parisian drinking culture has never been about the buzz. Instead, it’s about how a beautifully cra ed bottle can bring people together. This newfound acceptance of other kinds of drinkers just creates more room at the table.

Parisian drinking culture has never been about the buzz. Instead, it’s about how a beautifully crafted bottle can bring people together.Illustration by Mia Baccei

BURSTING THE

is online activism simply a performance?

By Malala Samirha Photography by Sky ByunYou are standing at the forefront of a protest: organizers are chanting, the police are mon itoring. As you walk alongside thousands of people, marching for a cause you are deeply com mitted to, the feeling of this impactful moment is abruptly halted. You watch as a camera crew and an influencer dressed in black hop out of a Range Rov er, carrying freshly made cardboard signs, looking to cash in on the action. They cut in front of you, snap a few shots with the crowd and scurry back to their parked car to edit and upload their “#Protest” pics. Hair-and-makeup, a five-minute photoshoot, and suddenly they’re an activist? You can’t shake the feeling of disbelief but you continue the march and return home, only to see that same influencer on Instagram and a post with hundreds of likes and comments praising their resilience. What do you do? Their platform brought thousands of people to pay attention to your cause but the influencer still benefited off the backs of actual protestors. Do you say thank you or make a fuss? How could their five-minute Instagram contribution equal your five hours of protesting? In the age of social media, it just might.

In the past twenty years, the way society protests has shi ed from actively participating in protests, rallies and sit-ins to social media posts and chang ing your profile picture every month: blue for Su dan, rainbow for pride, pink for breast cancer, black for BLM. Organizers used to reach out to com munities, hand out flyers and protests relied on word of mouth. Now, a sim ple Instagram post gets shared, a sto ry is reposted on Facebook or Twit ter and you have thou sands ready to march. That is one of the many ways social media has im pacted social movements.

Online ac

tivism usually take the form of a cute four-picture post, explaining the most recent crisis with a simple breakdown of brief historical context and ways to get involved. Simple, cute, and effective but this method of bringing awareness isn’t always positive. Reposting an infographic in place of attending a ral ly or donating to a cause is one way Gen Zers clear themselves of their moral obligations to actually get involved. With this form of slacktivism, time lines get oversaturated with the same information, desensitizing people and even sparking annoy ance. With constant awareness of global crises and suffering at all times on the internet, it’s common for people to become desensitized to social issues. When you have a constant stream of content about inequalities, performative activists rely on menial social media efforts as their contribution to ongoing movements that they don’t really care about.

There is a stark difference between the activists of to day and the ones who were forced to fight for their lives

blue for Sudan, rainbow for pride, pink for breast cancer, black for BLM.

and beliefs decades ago. The activist title was earned via sit-ins, actively campaigning for political change, or risking being arrested for a cause. Now the title of activist can be added to an Instagram bio a er posting a few infographics and hashtags. Pretending to be involved has be come an aesthetic; celebrities use it for attention, influencers protest for clout. The social media sav iors that pride themselves on compassion actually contribute very little to movements, while the true activists are being arrested for organizing protests. Wanting to seem involved without contributing is common in places where people have the privilege to not care. Everyday, there are inequalities in de veloping nations, civil rights issues in low income communities, and corrupt brutality being faced by millions of people around the world. Performative activism is a bubble of privilege for people that can afford to not be affected by these issues. Social issues as serious as genocide are lumped in with the daily TikTok trends cycle. Performative activists post infographics to their Instagram stories in be tween their outfit-of-the-day picture and #Brunch post. The level of privilege can be seen in the level of urgency people have when they get involved. Social media has created a click-based society,

with an endless scroll of content and no way to differentiate a social issue from an everyday selfie. Do we hold our tongues as we watch influencers use our protests as a photo opportunity, tainting committed activism with their opportunism? Al though slacktivism can bring awareness to a cause and people to a protest, we know that inauthen ticity and fake outrage aren’t enough. Do we as changemakers take the good with the bad? Do we, as a society, contain enough nuance to understand that all activism is a performance? They march to get attention, we march to bring attention; howev er selfish or selfless, the outcome is the same. The holders of power don’t see the intention of each protester— they just see a crowd.

Do we, as a society, contain enough nuance to understand that all activism is a performance? They march to get a ention, we march to bring a ention; however selfish or selfless, the outcome is the same.

FANTASTIC MS. FRANCE

By Elsa Lindner

exploring paris through the lens of wes anderson

by Sky Byun & Elsa Lindner PhotographyWe begin with a song— “Le temps de l’amour” by Francoise Hardy. Elsa Claire Lindner, Peacock writer and college ju nior, eager to discover a new perspective on her second favorite city, stands on the edge of the Seine. Her face fills the screen, kitschy vintage clothing and atypical hairstyle framed directly in the center of the scene. She makes direct and in tense eye contact with the camera, and it pans out, revealing a charming street framed symmetrically on either side of her. The setting? Paris, 2022, the year of the Water Tiger (according to the Chinese calendar). Her mission? To take a sightseeing tour of Paris, not through her own eyes, but through those of Wes Anderson.

The filmmaker Wes Anderson is known for mov ies that paint such an artistically pleasing picture, they could almost be watched with no sound. His creations are known for their artificial beauty and use of unrealistic color palettes and unrealistical ly symmetrical sets to create fanciful worlds. He expertly employs the extreme and intense use of different colors throughout his films. This o en cre ates a vintage feel in his movies, and Anderson’s worlds are awash with yellow hues, browns and vin tage greens. He also generously employs pastels, specifically the pastel pink which is so distinctive in The Grand Budapest Hotel. Bright red also appears o en in his work, a color believed to symbolize grief as it shows up in sad and emotional scenes.

In addition to his unique color palette, Ander son is also recognizable by his use of symmetry throughout his films. Most of his scenes frame the characters directly in the center of the shot and his buildings and sets are o en uncannily symmetrical. In every scene that appears, you get the sense that you might be look ing at a painting, a distinguishing feature of his work.

Wes Anderson currently lives in Paris, and it’s no secret that he takes inspiration from the streets of the capital and other cities in

France for many of his movies, particularly his lat est, The French Dispatch. At a premiere of the film, he shared with the audience in a Champs-Élysées theater, “I have a French air about me… I’ve spent my whole life feeling I am in a French movie.”

Our everyday life o en feels harsher than the so , warm colors in his films, and it sometimes proves hard to reconcile this reality with the aesthetic per fection created by Anderson. However, the unique city of Paris allows us to experience places that can provide an escape from real life and a journey into a charming, fantastical world. By strolling down its perfect streets, eating pastries bought from its pastel pink bakeries, and meeting the friends of fantastic Mr. Fox in it’s many museums, Par is allows us an escape into Wes Anderson’s world. This parallel universe can be found all over the city, simply by visiting a museum or getting off at the right metro stop—provided you know what you’re looking for. Let’s take a visual journey straight into Anderson’s world through the streets of Paris.

“I have a French air about me ... I’ve spent my whole life feeling I am in a French movie.”Illustration by Mia Baccei

Has the Media Gone Mad?

BY JACOB SHROPSHIRE DESIGN BY ABBY WRIGHT

BY JACOB SHROPSHIRE DESIGN BY ABBY WRIGHT

how partisanship in american news might not be so bad

If you took a map of the U.S. and put a red mark for every citizen who votes Republican, and a blue mark for every citizen who votes Democrat, you wouldn’t be surprised to find heavy blue pockets in cities and on coastlines, separated by vast red fields of rural voters. But even in Oklahoma, one of the most deeply red states in the nation, if you zoom in, you’ll find blue dots in the fields of red, the rare Democrat in a heavily Republican state.

From this, Layne Stansberry got their social media tag: The Diary of a Blue Dot.

“I don’t know what made me decide to do this series called, ‘What the Hell’s Going On in Okla homa?’ and I just did a two minute spiel of three or four different news stories,” said Stansberry. “Well, people really wanted that.”

Stansberry has built a significant social media fol lowing, racking up more than 55,000 followers on TikTok. Through their videos, Stansberry comments on everything from political debates, to high-pro file scandals and political violence. But what they talk about has one through line—almost all of it has to do with local Oklahoma politics. “Any time I talk about anything outside of Oklahoma, I don’t get very many views, I think most of my followers are here so they’re interested in what’s going on here,” said Stansberry, “TikTok kind of makes that decision for you.”

Stansberry’s work as a local progressive social media influencer, and their problem of a limited au dience, doesn’t exist in a vacuum—the media has fragmented all around us. What once was scheduled programming on public airwaves has become indi vidual shows streamed on-demand at your heart’s desire through any number of platforms like Net flix or Hulu, Spotify or Apple Music. People simply aren’t experiencing the same content at the same time like they did at one point, and that gives every one a different frame of reference to see the world through.

This fragmented media so o en pushes people into different chambers of thought that the same event is seen with vast differences depending on which side of the aisle you land on. Mass protests in the streets against systemic racial inequality, or an armed insurrection on the U.S. Capitol building, can be viewed through mediated lenses that have be

come further and further apart from one another. One person views the first event as righteous and the second as criminal, while another might see them as exactly the reverse.

that, broadly speaking, Facebook pushes conserva tive readers to view content that’s about 30% more conservative than the content they’re already view ing, and a similar effect was seen among progres sive Facebook users. In short, echo chambers lead to polarization.

The fragmented media environment puts peo ple into these echo chambers where they listen to nothing but media they agree with, pushing the “both sides of the argument” model to the side. This model isn’t entirely gone, but it simply lays the groundwork for the conversation about politics, in stead of shaping it like it used to. Maybe that’s for the best; a er all, impartiality can give equal weight and airtime to two opposing views, no matter how clearly right or wrong they may be. A climate sci entist who says the climate is getting catastrophi cally warmer is given the same amount of column inches as Jerry the snowcone guy who says climate change isn’t real because his sales go down when it gets cold in the winter. The truth isn’t necessarily partisan, but it isn’t always in the middle either, and that’s the distinction the both sides model doesn’t handle so well.

So, instead of broad media which is trying to appeal to the largest audience possible by way of impartiality, some companies and individuals can swoop in to fill the gap, reaching out to smaller seg ments of the population and relying on consumer loyalty instead of huge ratings. Fox News and Tuck er Carlson cater to the right wing Americans out there, while MSNBC and Rachel Maddow cater to the le . Former Trump administration officials make podcasts for Republicans to listen to on the way to work, and Obama-era political experts make theirs for Democrats to listen to on the drive home.

Local political activists like Stansberry make con tent geared towards a specific community in a way that relates to their media experience, while com pletely (and necessarily) abandoning the media ex periences of other audiences.

These are echo chambers and they push the par ties further apart from each other everywhere they go. Facebook, for example, is where about a third of Americans get some part of their news diet. But researchers at the University of Virginia have found

When you move people to partisan information gathering structures, the risk for mis- and disinfor mation rises. People and organizations, whether honestly or dishonestly, choose facts and figures that help them, sometimes entirely without regard to the bigger story or accuracy. While both sides delight in accusing each other of this, the general trust in news organizations fades even more among those caught in the middle, the very people the media machines on both sides should be most in terested in welcoming in.

But that’s an issue of morals, not of structure. The structure of partisan media machines is built to see things through a worldview, to validate events as through the lens of a partisan ideology, whatever the facts. The idea is about repackaging the news as a frame that convinces people who are uncertain, and embeds ideas further for the people who have made up their minds. Fake news, just like real news, will be filtered through that lens and organizations that choose fake news over real news should be punished for it, no matter the political perspective.

Partisan media might very well be bad for de

The truth isn’t necessarily partisan, but it isn’t always in the middle either, and that’s the distinction the both sides model doesn’t handle so well.

mocracy. Perhaps it’s a race to the bottom to see who can create the most effective propaganda structures so that one day one party can control everything.

“I do feel like I polarize people,” Stansberry ad mitted. Mentioning the t-shirts they o en wear in videos, they talked about how clothing with politi cal symbols or phrases could turn people off of their message from the start. “I do the tax the churches [shirts], which offends a lot of Oklahomans,” they said. “By having a shirt on that said that, automati cally people are going to be like, ‘I’m not going to listen to her.’ But that gets people’s attention too, so I don’t know, it’s a toss up.”

It’s worth considering what things would look like if one party didn’t participate in the media game. What outsized media advantage would the other side have in that fight to persuade or turn out vot ers, and ultimately to win elections and enact their will on the people? If anything, it’s necessary for that first party to engage in the fight, to not leave their voters behind, and to fight for some amount of moderation in policy at the end of the day, if not a movement in their own direction. To not engage is to concede.

This is where U.S. progressives are stuck. Fox News, Breitbart, thousands of microblogs and oth er media creators all got a head start before anyone else, and they’ve spent years hammering a message that supports Republicans and attacks Democrats in a coordinated and systematic way. And if a sin gle factor could be attributed to the rise in far-right ethnonationalism leading up to the 2016 election, the conservative media machine might just be it.

The very nature of the Democratic Party as a highly diverse coalition of voters from all kinds of backgrounds means that Democrats are fighting an uphill battle in an effort to reach specific community groups. Where Re publicans can speak to two or three major groups, and create one-off systems to attract other groups in cer tain places where it makes a differ ence, Democrats

are trying to attract hundreds of different minority groups, each with their own way of communicating internally and externally. Speaking to Black voters in Atlanta is an entirely different task from speaking to the queer community in San Francisco or work ing-class union members in Philidelphia. Coming up with a message delivery system that speaks to all of these groups with one voice is nearly impossible.

So, Democrats need a media machine of thou sands of different programs, podcasts, shows, or re

curring segments to speak to each group in the way they receive the message best. The good news is they’re working on it, and with all the different kinds of media that progressives are putting out, good headway is being made. But Democrats in the U.S. are eight to ten years behind Republicans in this fight between media machines. It’s like pitting a lit eral elephant against a literal donkey in a fight—the elephant is almost certain to win, even if the donkey makes a hell of a lot of noise going down.

The best outcomes in democracy come when you have a fair fight between positions, and both sides fight as hard as they can, because that’s when citi zens can make the best decisions. And right now, it isn’t a fair fight at all. The positions of progressives in the U.S. are undeniably popular, the campaign infrastructure is equal to, if not better than that of Republicans, and extremism on the right has even driven a relatively competitive donor base to the le of center. All that is le for Democrats is to put together a media ecosystem that appeals to people across the country, and ultimately one that mobiliz es them to political action in the system.

While Democrats have to fight for their politi cal lives to keep the U.S. experiment in democra cy from driving itself off a cliff, we should also put some effort into really repairing this media system of ours in the first place. This means creating new media moments that everyone sees, hears and ex periences, so we all have those moments in our col lective culture. And using those moments as gate ways, we have to talk to people we disagree with about literally anything, to disarm and humanize each other in our minds.

“If you know someone, and you are able to talk to them and not just call them names, you can actually break through,” said Stansberry.

The point of partisan media machines isn’t to break people apart at all, even if it sometimes does that too well; it’s to find them where they are and meet them there. It’s about going to every commu nity, to talk with every member of an extremely di verse coalition of cultures and beliefs, and speak to them with genuine interest in what they have on the line. And at the end of the day, it’s about persuad ing them—one voter at a time—to show up.

pitting

It’s like

a literal elephant against a literal donkey in a fght—the elephant is almost certain to win, even if the donkey makes a hell of a lot of noise going down.

talking through the taboo

how young adults are dealing with their sexual trauma

By Anastassia de Bailliencourt Design by Abby WrightLola escapes the metro, her coat slipping off her shoulder. She grabs her phone and calls her best friend. She doesn’t respond.

The metro doors close with the man inside. He grins at her with his yellow teeth.

She decides to call her other friend.

“Hello?” she says rapidly, when he picks up.

“Dude, it’s 11pm on Monday,” her friend says, yawning.

Lola trembles, and pulls down her skirt even lower and looks around the empty metro. “I - Something happened.”

“Where are you?”

“In the metro. A guy walked towards me, and I didn’t think anything of it until he looked me up and down and sat next to me,” Lola gulps down her saliva. “He put his hand on my leg and wouldn’t take it off. I moved my leg but his hand came back and grabbed it even harder. There were only five other people on the metro and nobody did anything. I have no idea where I am.”

“What were you wearing?”

“What? That has nothing to do with it!” Lola screams, holding back tears in her eyes.

“Well kinda,” he says.

“You’re not helping. I was touched in the freaking metro dude, I don’t know what to do.”

The UK’s National Health Service (NHS) defines sexual assault as “non-consensual sexual touching where the perpetrator has no reasonable belief that the victim is consenting.” Lola’s story shows that there are different types of sexual molestation which go far beyond the horrible act of rape but can be instances where the perpetrator uses force and threats, like grabbing or touching the victim. For young people who have been sexually touched without their consent, many don’t understand that they have experienced assault because they were too young when it happened and because of the lack of conversation surrounding the topic.

A European study found that more than one in three women and almost one in six men were as saulted by the time they graduated university. Men in particular are unfortunately unlikely to report as sault out of fear of being labeled weak and emascu lated. The reactions to sexual assault are informed by gender biases and power dynamics between the sexes.

While much of the focus is on the short-term trauma associated with sexual assault, it can also o en lead to long-lasting psychological conse quences, such as intimacy issues with a partner or developing an addiction to help cope with the af termath. Unwanted touching and aggression can lead to depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and anxiety. Interestingly, in Europe, only 5% of men receive this diagnosis a er experiencing sexual assault, and only around 10% of women.

The mental anguish that stems from sexual as sault can last for years and most victims feel alone and unable to talk about their experience with any body. Lou, an undergraduate student at the Amer ican University of Paris (AUP) says, “Talking with people about the experience can help to redefine it as a positive sexual experience.”

Research has shown that only between 20% to 25% of women and around 8% of men talk about their experience with close friends, therapists or family. Sexual trauma is still not discussed enough and this lack of discussion prevents people from understanding what sexual assault really is and how to deal with its consequences.

guy i

oral sex,

In an attempt to help victims of sexual assault feel heard, I interviewed three university stu dents in France between the ages of 20 and 35: two women and a man. Their experiences are important for other victims to know that they have a voice and to know that they are not alone.

LOU

Lou is a 20-year-old student at AUP, who was born and raised in NYC. She has a weird obsession with Marche d’Aligre, a market in the 12th arrondisse ment of Paris. She likes to paint, dance, read essay books, and watch Al Jazeera’s “start here” videos.

How and when did you experience sexual trauma?

When I was fourteen, I was sexually assaulted by an adult. For a few years a er that, I didn’t date a lot of people because I didn’t comprehend that I had

“a

knew emotionally blackmailed me into giving him

and since then i’ve been living with ptsd.”

been sexually assaulted. For me, it wasn’t as if I was actually raped at that time so I didn’t know what it was, especially being 14, and never having had any other experiences. When I was 18, I was raped by someone I met that night and never interacted with them again, thankfully.

Since then, have you been able to move on? What has helped you?

I was really nervous about losing my virginity, I felt like the next time someone touched me I would panic. When I lost my virginity, it was so different. I think it was because I had never had any sexual experience before I was sexually assaulted. I real ized that sexual assault and rape are not about sex in any way, shape or form. And when you do have sex when you want it, it’s so different and obviously there are times when you have down moments or uncomfortable moments but I really tried to focus on separating those two instances.

Do you tend to have one night stands or do you want to get to know the person first?

I really tend to have one night stands. I tend to really not wait. A er what happened when I was 18, I was scared to have sex, and I wanted the person I was going to have sex with to be someone that I had already had sex with, was already comfortably with. One night I was super drunk, and said “Fuck this shit, I’ve been waiting for so long for someone that doesn’t exist. I just want to rip off the bandaid and move on.” A er my first time, I broke down, be cause I was not ready and frustrated.

I think one night stands are easier sometimes, be cause I think when I know someone very well, I want to disclose everything I’ve been through with them. So if it is a drunk one night stand and I know that I’ll never see them again, I don’t have to go through all the emotional aspects of it.

Have you seen a therapist about it?

I started therapy last October, but for me person ally, it’s still been difficult to talk about it with a ther apist. It’s always been easier to talk to my friends who were there when it happened, because they know the situation rather than having to explain ev erything to a new person, like a therapist. But see ing a therapist, and talking about it in conceptual ways is definitely helpful as well.

Is there any advice you would give to peo ple who want to be sexually liberated?

I don’t know if there’s one general piece of ad vice, because every experience varies. For me, it would be to constantly remind myself to sep arate my traumatic experiences, reminding my self that they had nothing to do with me or sex.

EILEEN

Eileen is a 22-year-old French student, who hopes to become a communications director. She speaks three languages: French, English, and Russian. She’s a cosmopolitan girl who intends to travel some more in the future.

How did you experience sexual trauma?

When I was sixteen, a guy I knew emotionally blackmailed me into giving him oral sex, and since then I’ve been living with PTSD. A er that, I’ve had issues with sexual intercourse in dark spaces, be cause I relive the moment.

When did you finally get comfortable with sex again?

I think it got better when I met my boyfriend, which is very cheesy to say, but he makes me feel confident and safe. I know it’s him when we have sex, I can smell his scent and I have known him for three years so I know he won’t hurt me.

What helped you put this experience in the past?

What helped me was to see a therapist who helped me work on myself to be able to trust some one.

Did you see the therapist with the purpose of helping you with your trauma?

No, I went to see her because I was suffering from an eating disorder. I did develop anxiety af ter my sexual assault, so it could have led me to my binge eating.

Did you talk about your assault with your current partner?

Yes, it was one of the first things I told him. When I met him, I was drinking a lot, smoking a lot, and selfharmed quite a bit. At that moment, I was an open book about my feelings and being open about it helped me be more comfortable with my new partner. GEOFF

“i very much felt pressured into doing it, and i didn’t know what to do or how to escape the situation besides going through with it.”

GEOFF

Geoff is a 30-year-old AUP student originally from San Francisco, CA. He grew up all over the Bay. He is fond of architecture, music (including rock, jazz, rap, classical), and is a Giants fan.

How did you experience sexual trauma?

I had a lot of women who were very forward with me, very overt and touchy. I don’t like people touching me, no matter who they are if I don’t know them well. When I was sixteen, I got into a car with a girl I had never met before, and she stuck her hand down my pants. I didn’t know what to do because I thought it was normal, but I was very uncomfort able. My parents didn’t tell me about these things, so I didn’t know. I’m very sensitive to touch, and a lot of women have touched me either in a drunk state or when they think it’s okay.

At 23, I got locked in a bathroom with this 35-year-old married woman. It was at this post-pro duction theater party. She came in, closed the door, and stood in front of it and started to get naked and said, “Are you gonna be a man and fuck me?”

I thought, “Is that what I’m supposed to be?” I very much felt pressured into doing it, and I didn’t know what to do or how to escape the situation besides going through with it. And during it, the woman had long nails and without asking me first, she stuck her finger in my ass and it really hurt and she said, “Stop being a pussy”. Later that night, I passed out at the house, and I don’t remember if she passed out with me, because I don’t remember a lot, but I woke up in the middle of the night and she was riding me. And I don’t remember if I okay-ed it, cause I was drunk. I woke up the next day and felt gross, and there was nobody else in the house besides the two of us and the person who owned the house.

Since then, have you been able to move on? What has helped you?

Yes, I kinda developed a sixth sense about wom en who are a little too forward or overly touchy, and I became sensitive to this thing. I keep my distance with people until I trust them a lot more. I’ve just grown an awareness of how people treat each other physically, being a little more selective and mindful of the people I want to connect with and treating sex a little more respectfully. There’s sexual trauma such as rape and assault, but anoth

er form of trauma can come from hurting someone by making them think that you love them when you just really want sex. I’ve been there too, more on the perpetrator side. I try to be aware of all those things now.

Do you like one night stands?

One night stands occur, when you have a real ly quick connection with someone. When I drink, I feel it’s okay to let myself be a little bit more open and more wild, as opposed to during the day when I have work. Sometimes, someone is on the same wavelength as you and if you’re having fun in the moment, it’s great. These things happen really quickly and you go along with it. I wouldn’t say I’m above one night stands, but it has to be with some one you are feeling it with, and I don’t like having to talk someone into it. If they are not on the same wavelength as me, it is not a compatible match.

Do you have tips that could help other peo ple to feel better a er being assaulted? To feel better sexually, to feel liberated?

Critical self-analysis was helpful, looking at my actions to protect myself and people around me from it. I’m a very skeptical person. As a guy I un derstand what it’s like to just want to have sex and to use whoever is around or available for that. I think being open and honest is a good thing as far as choosing your partners and not decieving them by telling them its about love when it’s only about sex. Treating sex with the respect that it deserves, because you are basically giving a part of yourself and receiving a part of someone else, and you have to make sure this person is someone you want to give that part of yourself to. Writing about it helps because it allows me to see my thoughts so that they aren’t just running around in my head, but I can see them in a concrete form and view them and feel separate from them, as opposed to feeling like they are possessing me, in a sense. Counseling and talking to people I really trust also helps.

While I felt violated, I didn’t feel physically con trolled, I felt more emotionally frozen; not knowing how to handle the situation, and not knowing how to draw boundaries. “No” was not an option for me really, when I was younger.

EAT ME, DRINK ME

international students share their favorite, most indulgent meals

By Chandler Sumpter Gillyard & Lola Rock Photography by Sky ByunIngredients:

- 1 lb. of potato peeled and chopped

- 1 teaspoon salt

- 5 cups water for boiling

- 1 ½ tablespoons olive oil or vegetable oil

- 1/4 cup onion finely chopped

- 2 small garlic cloves finely minced - ½ teaspoon salt

- 1 cup vegetable oil for frying - 16 warm corn tortillas

Toppings:

- 3 cups iceberg lettuce shredded

- 1/2 cup sour cream

- 1 cup homemade tomato salsa

- 1 cup cojita cheese

“I grew up eating them since I can remember and there’s so many toppings you can choose from. But for me it’s comfort food that reminds me of home.”

Tacos de papa

By Mayka EscutiaIngredients:

- 1 two to three lb. rotisserie chicken

- 2 medium onions

- 1 lb. turnips

- 6 garlic cloves

- 1 tbsp. thyme leaves

- 3 tbsp. unsalted butter

- 2 1/2 tsp. kosher salt

- 1 1/2 tsp. freshly ground black pepper

- 3 tbsp. all-purpose flour, plus more for surface

- 1 cup dry white wine

- 2 cups heavy cream, divided

- 1 ten ounce bag frozen peas

- 1 fourteen ounce box puff pastry, thawed overnight

“My mom makes chicken pot pie every year when we go on our annual family ski trip. It’s special to be because I only get to eat it once a year and it’s connected to some of my favorite child hood memories skiing with my family”

chicken pot p ie

By Lola RockPASTA AMATRICIANA

By Eleonora Marcone

By Eleonora Marcone

Recipe:

1. Sautée onions with oil in a pan

2. Add a small spoonful of tomato paste when onions are fragrant and let simmer until oil changes color

3. Add tomato sauce and let it reduce on low heat for 15-30mins

4. Add lardons

5. Simmer in sauce for 15 mins

6. Add basil and cover while pasta cooks

7. Once done add tsp of pasta water

Salt and pepper accordingly, serve with fresh parm

“This pasta is my favorite dish for a few reasons, it’s quick and easy to make but most im portantly it reminds me of family. I first learned how to make this with my dad, who would make it all the time because it is a traditional dish from the region of Italy where I am from. Since it was o en made for me growing up it works as a perfect quick pick me up for when I’m feeling a little down.”

By Sara Bashiti“I grew up eating mujaddara that my mom made. It’s a Palestinian dish that has been passed down for generations. It’s one of the easiest dishes to make because of the staple ingredients, so it has become my go-to dish. It’s usually referred to as ´the poor man’s food’ because of the relatively cheap ingredients but it was always the perfect meal to me because it’s guaranteed to fill you up and has an amazing balance between the sweet caramelized onions with the cumin in the rice and lentils and the fresh taste of the salad and yogurt on the side. It reminds me of my mom and my family back in Palestine which is always comforting.”

brooklyn wahine shoyu chicken

By Mehana PlaceresIngredients:

- 7 1/2 pieces boneless, skinless chicken thighs - 1/2 cup shoyu

- 2 1/2 cloves garlic, mortared - 1/2 small sweet onion, chopped - 1 1/2 thumbs ginger, mortared - 1/2 tbsp. black pepper - 1/2 tbsp. dried oregano - 1/2 tsp. red pepper flakes - 1/2 tsp. ground paprika

“Shoyu chicken is one of my favorite things my mom makes and it was the first recipe she passed down to me.

My mom couldn’t cook much when i was growing up but when i was about 10, my step dad needed a caterer for his photo shoot and my mom stepped in to help him out. this turned into my mom creating a catering company and deciding to teach herself how to cook out of necessity.

by the time i was in middle school my mom had managed to open up a pop-up restaurent in brooklyn called brooklyn wahines where she made food from home - poke from her birth place in hawaii, banh mi’s in honor of my Ba Ngoai and shoyu chicken of her own creation inspired by huli huli chicken.

She always said shoyu chicken is better grilled and on warm summer nights we would get that treat. When i was growing up, we used to have bbqs on the roof of my building with all my neighbors and a view of the manhattan skyline. my moms shoyu chicken was always a hit.

This chicken not only represents my mom and her creativity and resilience but it also tastes like home.”

GET IN LOSER, WE’RE GOING SHOPPING

gories of products. What was once a necessary task of haggling evolved into shopping for pleasure, and people purchased items they enjoyed in their homes or for themselves. This shi would introduce

By Ava Castaneda Photography by Sky ByunIn need of making yourself feel better from stress, anxiety, sadness, or any other overwhelming emotions? The more responsible approaches include exercise, meditation, cutting out alcohol and making sure you get those eight to 10 hours of sleep. You may even find yourself sitting in therapy working it all out. But what if you are in need of a quick fix to get you out of that rut? If so, you may indulge in retail therapy; nothing like a mountain of clothes to drown out all the noise in your head. Yet with each new clothing haul, you may bring home a lot more baggage than you intend to. Is swiping away with our credit cards really the solution to our problems?

Retail therapy is the act of shopping to make yourself feel better. It’s a practice that people use more commonly than you think. The term was first coined in the 1980s by journalist Mary Schmich in the Chicago Tribune. Shopping frequently became more common during the Industrial Revolution as a result of the increased production. With that came the creation of department stores and a shi in the way shopping was approached. People could now browse through one building that had endless cate

retail therapy as an activity for people to escape the rapidly changing world.

Retail therapy isn’t just about buying clothes. Whether it is treating yourself with a donut a er a long week of work, or finally splurging on those sneakers a er a big accomplishment— it’s a kind gesture to yourself. The reason why there is such a positive emotional response to retail therapy is because the trigger that pushes us to shop is o en the result of feeling a lack of control. The feelings of sadness, frustration or anxiety come from situa tions that seem hopeless, where we have no control over the outcome. Therefore shopping is choosing to take control of the situation; purchasing products

what baggage are you actually bringing home with that retail therapy spree?

We are now able to shop in a quantity we never have before, courtesy of the digital age.

helps release dopamine, the chemical most associ ated with pleasure. Scrolling on our phones is one of the addictive habits many of us have begun to in clude in our daily routines. On apps like Instagram or TikTok, we are exposed to an over whelming amount of products. Social media has opened the doors for the lifestyle industry to spread and evolve. Through the inter net, we are able to know which brands are trending, what’s the best waterproof mascara, the latest decor piece, or the coolest app to get on. Yet while we enjoy connecting with each other, hungry companies see this as an opportunity to in fluence the market. Today, lifestyle companies use social media as their most lucrative marketing tool. Have you ever seen a product pop up on your feed and it looks like it could fit perfectly in your life? In between posts from family and friends, you will stumble across an ad, a recommended post from a company, or even a convincing influencer promot ing a product. You will like one post about it, and then suddenly your feed is bombarded with tons of different websites with similar products.

When asked about social media’s negative ef fects in relation to retail therapy, Donatella Jackson, a graduate student at the American University of Paris (AUP), said, “I think all of the negative emo tions from social media: anxiety, depression, and insecurity kind of keep up in a cycle of why we need retail therapy, and ultimately just helps other big companies, regardless of keeping us in this sad state.”

Every day we see more and more companies in vesting their advertising and marketing money into influencers. Think about all the times that a fash ion blogger or lifestyle YouTuber recommended a product and you felt more inclined to buy it, and sometimes you just caved and did. While influ

encers have shi ed what makes up fashion today, they have also influenced our consumption. With one click, your ability to shop has multiplied with easy access to so many online retailers. It takes just a couple of seconds to plug in your cred it card information and come home to a mountain of packag es. We are now able to shop on a scale we never could before, courtesy of the digi tal age.

A er better under standing the way so cial media marketing has taken control of the lifestyle indus try, where does that leave us with retail therapy? Sometimes all the posts make us feel like we aren’t keeping up or make us

“If I am feeling sad I go shopping, if I feel happy I will go shopping. Even though I go to normal therapy, I know shopping is a way to switch my mood faster.”

and I think retail therapy is real for me. If I am feel ing sad I go shopping, if I feel happy I will go shop ping. Even though I go to normal therapy, I know shopping is a way to switch my mood faster. It’s more about having clothes and a good outfit so I will feel better. I know it’s superficial but it helps.”

All good things—like retail therapy—need to come in moderation. A shopping spree once in a while can be a good cure on some days, but par taking in it too much, too o en can lead to a down ward spiral of receipts. This lighthearted coping mechanism can have an adverse effect on your wallet. Once you begin shopping too much in comparison to what your lifestyle can support, this coping mechanism becomes a problem, spreading into other avenues of your life. An unrestrained overspending habit will have you in crippling debt. This is o en the result of lying to oneself, another negative that comes with using retail therapy. Lying to yourself to justify excessive shopping is how one gets wrapped up in receipts and bill notices. A per son may lie to themselves about how easily they fall for marketing tactics, or change the perception of the truth to find the smallest excuse to buy that new shirt. Marcone added, “I think now, instead of fo cusing on the problem causing us to go shopping, going and shopping takes away from the problem. We just end up in this loop, associating the mood changes with shopping. Even for myself, it is a su perficial way to ‘solve’ the problem.”

Lying to yourself shopping habits is the first step to self-deception and retail therapy no longer be comes an actual therapeutic tool, but a compul sive behavior. All of a sudden, every time you are feeling anxious or sad, the instinctual cure is a purchase. This unhealthy coping mechanism can turn into a shopping addiction or a compulsive buying disorder. Compulsive buying disorder, or oniomania, is the compulsion to spend money regardless of need. According to the Cleveland Clinic, this kind of addiction is very similar to sex or gambling addictions. There are even cas es where people have blackout shopping episodes with no recollection of making a purchase.

One of the key signs of retail therapy turn ing toxic and becoming an addiction is the

feeling a er a purchase. The negative feelings that follow are usually disappointment with yourself and feeling as if you are not in control of your spend ing. Retail therapy is an attempt to regain a sense of control. If your reaction to shopping is adverse, un controllable, or unmanageable, then retail therapy is not the best coping mechanism for you.

However, if done responsibly, practicing retail therapy can still be helpful. An unplanned shopping trip can ease a poor mood, according to a publica tion from 2014 by the Journal of Consumer Psychol ogy. One of the main ways shopping aids in alleviat ing negative emotions is by distracting us from our anxiety. There are some things you can implement

spending, track your purchases. Additionally, be very intentional with what you are buying. If you’re unsure about something, try enjoying window shopping instead to give yourself and your wallet a break.

While shopping, be conscious of what brought you there in the first place and how you’re feeling. Are you avoiding work or are you just bored? Being more aware of your intentions allows you to catch yourself when you are slipping. Make sure that in addition to retail therapy, you are alleviating your stress with other healthy habits: eating healthy, sleeping enough, exercising. And if there comes a point when you are struggling, therapy can actual ly help. Talking to a professional can help you find the root of the problem and address it with a more direct solution.

All in all, everyone indulges in a little retail therapy now and then. These days, we are more inclined to do so because of the ability to shop on our phones. Yet as our tendency to swipe on our phones in creases, so does the tendency to swipe away our feelings with a card, and we are more vulnerable

to spiraling. Our escape from these overwhelming problems doesn’t always have to be a bad thing. To enjoy retail therapy requires us to really reflect on why we are partaking in it. You wouldn’t expect such a frivolous activity to push us to be so intui tive, but it does. So once in a while, treating your self with a purchase may just be the sweet escape you’re looking for.

“We just end up in this loop, associating the mood changes with shopping. Even for myself, it is a super cial way to ‘solve’ the problem.”

THE ACE UP THEIR SLEEVE

a spotlight on four of aup’s up-and-coming creators

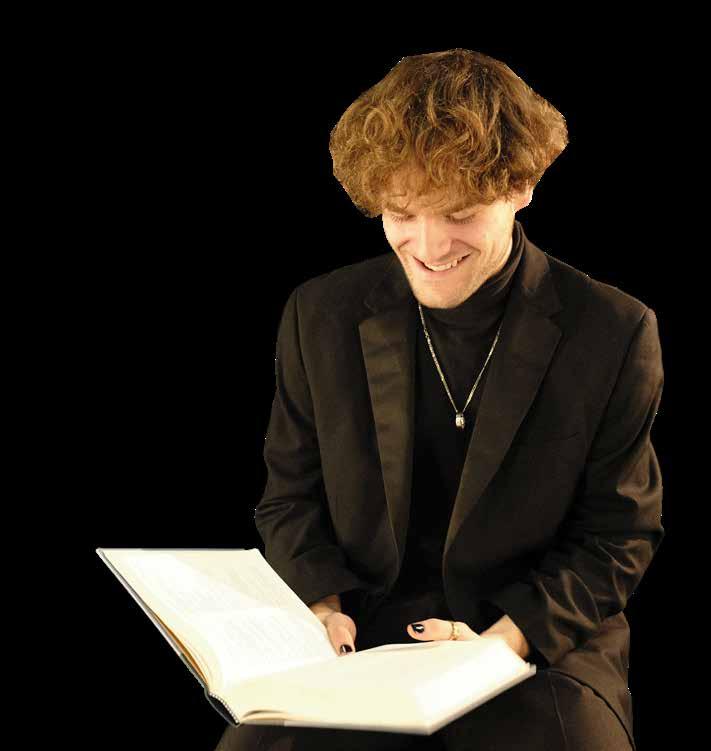

By Isaac Bates Photography by Sky ByunDeep in the forests of a faraway land, lives a hunter named Herne. Following a standoff with a wild deer that leaves him close to mortally wounded, Herne forever roams the forest as a half-beast humanoid, stalking and tormenting its in habitants as fulfillment of an agreement he made with the Devil to keep his life.

The story of Herne was not only imagined by one of AUP’s students, but written, produced and directed into a short film as well—Chassé. Georgy Keburiya, the maker of the film, consid ers himself a full-time filmmaker.

It is reasonable to assume that Keburiya must live and breathe film. And yet, he doesn’t. Absent from clubs like Screenwriting and Creative Production, Keburiya’s process is completely in dependent from the university. He does not even study film at AUP, choosing instead to pursue a degree in Global Communi cations. One would think that most people with such talent and passion would complement their abilities through university, but Keburiya is not an exception and in fact represents a much larger trend hidden within the AUP student body.

There is a small, yet significant community of talented students who are releasing outstanding work in their respective creative mediums, completely independent from AUP. Like Keburiya, Allen Blackwell, a graduate student, also writes and directs, and has released several short films in recent years. Oscar Padula, a Global Communications student, is an up-and-coming rock musician with multiple demos in the process of release. Paudu la regularly performs at small venues throughout Paris with his band members. Dylan Kornhauser, an aspiring author, has sev eral novels in the works, and hopes to publish his literature by the end of the year. These are just a few of the several students who have chosen to perfect their cra without making use of the university’s support and resources.

As a whole, these students are indicative of a movement, one which represents an underground current of individual creativi ty, and is significantly underdiscussed throughout the university. These side-hustlers, intense enthusiasts, or subject matter ex perts have yet to be properly revealed within AUP despite the impactful work they have produced.

I sat down with four such students and interviewed them sep arately, asking them to reveal their creative methods, speak on their inspirations, and share how they got their start.

GEORGY KEBURIYA

Though Keburiya admits he has years of learn ing and improving his material ahead of him, he is no novice in the field of filmmaking. Over recent years, three of his last five films have won awards, while several others have made it to fi nalist and semi-finalist rounds, gaining recognition in film festivals like the Independent Short Awards, Believe Psychology Film Festival, Toronto Film and Script Awards, and more.

Elaborating on his film Chassé, Keburiya de scribed how his love for film developed, and ex actly how he was inspired to make his horror movie following this murderous, mythical creature.

“My parents used to have a summer house where I spent my whole childhood. Previous owners had le video cassettes of old films behind. I remember how my mom randomly put on a film she found in the closet. It was Tim Burton’s first Batman screen adaptation.”

This moment would change Keburiya’s life, as it created an immeasurable bond between him and the villains, vigilantesand monsters of his favorite films. “For me, Burton’s Batman was bringing atten tion to the dark side of this world, a part that is pres ent in all of us— the fear of mayhem and madness.”

“That is why I use a monster in Chassé. I fell in love with monsters from a very young age. Despite their exaggerated and terrifying features, they o en dis play a touch of humanity, either in their behavior or appearance. Monsters represent deeply-hidden aspects of ourselves and can remind us of the po tential dangers that arise from indulging in our own primal impulses. They are a fundamental part of us as a species, reminding us of our past, tempting us to explore faraway lands, but also discouraging us from entering dangerous territory.

Keburiya spoke specifically on how his passion for the horror genre developed. “I once found a cassette of Jaws, I remember watching it and be ing completely shocked from the first shark attack. That was the starting point of my horror-genre ob session. While trying to get my hands on any acces sible foreign films, I was able to feel the fears of dif ferent cultures that filmmakers tried to showcase. This shaped my taste and gave me a desire to input my own personal fears through my work.”

The filming of Chassé was tough, according to Keburiya, as choosing a setting appropriate for a horror film can be challenging. “A er finishing the script, we understood that the hardest chal lenge would be finding the right location in order to effectively create the right atmosphere, which needed to be eerie, yet hypnotizing. The film was entirely made in Georgia, in a small village called Kesalo. The shooting process was surprisingly quick despite the harsh environmental factors—mosqui toes and the extremely hot temperatures.”

Keburyia briefly spoke of his newest film, which he plans to release shortly. “Right now, I am work ing on another short horror film called The Portrait, which I hope to be finished with in December. More details soon.”

Monsters represent deeply-hidden aspects of ourselves and can remind us of the potential dangers that arise from indulging in our own primal impulses.

ALLEN BLACKWELL

Allen Blackwell is another accomplished di rector who has made a name for himself outside of AUP. Though he has also re leased several short horror films in the past, he is most proud of his nonfiction, short documentaries which follow the intense stories of WWII veterans.

Speaking on one of his accomplishments—the short documentary following the gruesome mis sion that earned a wounded B26 pilot a Silver Star in WWII—Blackwell detailed the story behind mak ing his film, Lt. Joe Stevens.

“One thing I do is make documentaries with my father on WWII veterans; mostly B26 pilots be cause my grandfather was a B26 pilot. One day my dad was looking through a book of stories writ ten by other pilots, and he came across one that was written about my grandfather. It turns out, the author was his co-pilot on a mission. My dad con tacted the author, Joe Stevens, who turned out to be alive and living in Orbisonia, Pennsylvania. We reached out to him, and he expressed a lot of inter est in talking to us. With permission from him, my family flew up from Mississippi with a camera crew and we met with him. He was as sharp as a tack and was very observant. You could tell he was a great pilot.”

“We recorded him retelling the story of how he earned his Silver Star. He saved his crew’s lives in Germany with his piloting skills, and that is what this film is about.”

Though Blackwell did not submit his documenta ry to any festivals in hopes of winning an award, his film was deeply impactful not just to Lt. Joe Stevens and his family, but to the community of Orbisonia, Pennsylvania as well. The film gained recognition by the Department of Veterans Affairs and even caught the attention of a Pennsylvania congress man.

“Once we premiered it and showed it to Joe and his family, the Local V.A. contacted us saying they wanted to do a full presentation for Joe, and screen it in front of the entire town. They contact ed a Pennsylvania congressman, he then asked us for a copy of the film. Eventually, our documentary made the news, and we presented the film for the entire town of Orbisonia. Though the congressman couldn’t make it to the screening, one of his repre

sentatives gave a speech a er, announcing that the bridge in Orbisonia would then on be known as the Joe Stevens Memorial Bridge.”

“That was a direct outcome of our documenta ry. Nobody knew about Joe until we made a movie about him.”

When asked about his specific creative process and what in particular he draws inspiration from, Blackwell gave a straightforward answer, “I love telling stories and filming unique circumstances. I think the best stories are the ones that have some truth to them, or the ones that have already hap pened, but are so shocking or intense that you’re le in disbelief. I simply try to make films that are grounded in reality.”

Elaborating further, Blackwell stated his inten tions for his future films. “I recently had a producer express interest in buying one of my films. If I can get this movie sold, it’d be a gamechanger for me. As far as my upcoming works, right now I’m looking to film someone who fought for Germany, and al ready have someone who fought in the French Re sistance. He joined a er his small village was raided by the Germans, but that’s a whole other intense story I won’t get into.”

I think the best stories are the ones that have some truth to them, or the ones that have already happened, but are so shocking or intense that you’re left in disbelief. I simply try to make films that are grounded in reality.

DYLAN KORNHAUSER

Dylan Kornhauser, a senior at AUP and an as piring author, has written a number of short stories. Although he has more experience writing academic pieces since he came into univer sity, he has recently transitioned into more creative writing.

He briefly detailed his past works. “Before I got here I was mostly writing academic research. I wanted to be involved in political science and phi losophy, so my writing was built off what I was al ready learning in class. Though since I’ve arrived in Paris, I have been discovering my passion for litera ture, reading and creative writing.”

He highlighted the story behind one of the novels he is most proud of, “The Pit Queen”, and the emo tions he felt while writing that piece.