Archaeology and Conservation in Derbyshire and the Peak District

Editor: Roly Smith, 33 Park Road, Bakewell, Derbyshire DE45 1AX Tel: 01629 812034; email: roly.smith@hotmail.com

For further information (or more copies) please email Del Pickup at: del.pickup@peakdistrict.gov.uk

Designed by: Sheryl Todd, Moose Design sherylt38@yahoo.co.uk

Printed by: Buxton Press www.buxtonpress.com

The Committee wishes to thank our sponsors, Derbyshire County Council and the Peak District National Park Authority, who enable this publication to be made freely available.

Derbyshire Archaeology Advisory Committee

Buxton Museum and Art Gallery

Creswell Crags Heritage Trust

Derbyshire Archaeological Society

Derbyshire County Council

Derby Museums Trust

Historic England (East Midlands)

Hunter Archaeological Society

University of Manchester Archaeology Department

University of Nottingham

Peak District Mines Historical Society

Peak District National Park Authority

Portable Antiquities Scheme

Sheffield Museums Trust

University of Sheffield, Department of Archaeology

South Derbyshire District Council

This issue of ACID is jam-packed with interesting and insightful articles about what has been happening in the world of archaeology and heritage in Derbyshire and the Peak District.

Iron Age archaeology from across the county is explored, from Graeme Guilbert’s feature on the new interpretation plan of Mam Tor in the north on page 4, to a possible timber boundary at Swarkestone in the south (p20) and a find of an Iron Age vessel fitting at Whitwell in the east (p14).

More recent heritage is discussed in articles about Victorian collector Thomas Bateman (p28) and an album of 19th-century watercolour landscapes recently acquired by Buxton Museum and Art Gallery (p26), while the news pages highlight a new digital interpretation app for the ruins of Errwood Hall, which was built in 1840 and demolished in 1934 (p25).

Several pieces in this issue explore work carried out at sites with religious heritage. The myths relating to the rock-cut Anchor Church at Ingleby are examined on page 8 and the restoration work to the stained glass at Haddon Hall’s chapel, demonstrating one of those wonderful before-and-after moments, is featured on page 23. The Roman Catholic connections with North Lees Hall above Hathersage are highlighted in an article by Stephen Maloney on page 10.

Science is increasingly playing an important role in archaeology through allowing existing excavation archives to be re-examined, such as Dr Tom Booth discusses in his piece about ancient DNA analysis of human remains in the collections of Buxton Museum and Art Gallery (p16). It also augments new fieldwork, such as the use of OSL (Optically Stimulated Luminescence) to date Hull Bank at Willington (p21) and archaeobotany to better tell the story of Romano-British Melbourne (p22).

2 Foreword

Martha Jasko-Lawrence, chair of the Derbyshire Archaeological Advisory Committee

It is always heartening to see young people being interested and participating in their area’s heritage. I have been involved with the Peak District Young Archaeologists’ Club for over a decade and on page 13 you can find out what the club has been doing recently.

Morgause Lomas reports on the continuing success of the Derbyshire Scout archaeology badge (p17). And the two organisations both celebrated Jack Goodchild, a Derbyshire Scout and a Peak District YAC member, winning an award for Young Archaeologist of the Year (p12).

I hope you find something you enjoy in the magazine and are inspired to get out and about to further explore the heritage of our amazing area.

The views expressed in the pages of this magazine do not necessarily reflect those of the editor or publishers. No responsibility will be accepted for any comments made by contributors or interviewees.

No part of this magazine may be reproduced without the written permission of the publishers.

4 Mam Tor – an archaeological Wonder of the Peak Graeme Guilbert describes a new interpretive plan of Mam Tor, one of the original ‘Wonders of the Peak’

7 Defending Mam Tor Anna Badcock, Sebastian Chew, Chris Locker and Phillipa Pusey-Broomhead report on the measures taken to alleviate visitor pressure on Mam Tor

8 Maybe the locals were right Ed Simons explores the fascinating past of Ingleby’s Anchor Church

10 A Short History of North Lees Hall Stephen Maloney, a University of Sheffield student placement, recounts his history of North Lees Hall

11 Another brick in the wall at Mickleover Ashley Tuck of Wessex Archaeology on the recent excavations of a former railway brickworks near Mickleover

12 Young Archaeologist of the Year

Morgause Lomas reports on a young Buxton scout’s “outstanding contribution to community archaeology”

13 From Barns to Bones

Martha Jasko-Lawrence, Leader of the Peak District Young Archaeologists’ Club, describes a busy year

14 Find of the Year: Taking the bull by the horns at Bolsover

23 Diamonds and seaweed in Haddon Chapel

Meghan King, Portable Antiquities Scheme Finds Liaison Officer for Derbyshire and Nottinghamshire, nominates her ‘Find of the Year’

15 Balancing development against respect for the past Reuben Thorpe, Development Control Archaeologist for Derbyshire County Council, describes his daily balancing act

16 ‘Dem not-so-dry bones’

DNA analysis from bones kept at Buxton Museum is revealing important new genetic evidence, as Dr Tom Booth of the Francis Crick Institute reveals

17 Derbyshire Scouts “prepared” for archaeology Morgause Lomas reports on the success of the new archaeology badge

18 Raider of the Lost Barques

Roly Smith catches up with popular TV archaeologist and historian Sam Willis, who describes his adventurous life

20 Were the Swarkestone timber posts an Iron Age boundary?

The timber post alignment found in the River Trent at Swarkestone has interesting parallels, reports Kris Krawiec

21 Hull Bank reveals its secrets

Kris Krawiec describes the finding of a prehistoric burial mound at Willington

22 Beer and gaming in Roman Melbourne

Georgia Day on a newly discovered Romano-British site at Melbourne

Genevieve Gorham describes recent restoration work to the east window of Haddon Hall’s chapel

24 News

News from around the county

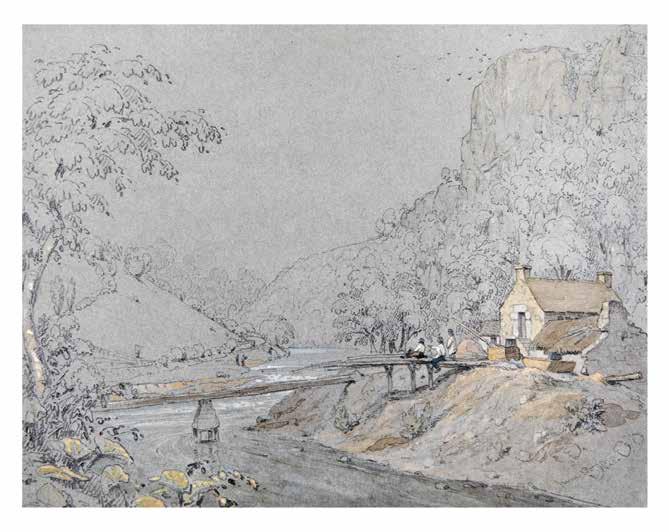

26 A Twopeny tour of Derbyshire Ros Westwood, Derbyshire Museums Manager, describes the latest acquisition at Buxton Museum and Art Gallery

28 Brought to Light: the Remarkable Bateman Collection

Martha Jasko-Lawrence, Curator of Archaeology at Sheffield Museums, describes the recent Thomas Bateman exhibition

29 Green light for Wingfield station Lucy Godfrey of the Derbyshire Historic Buildings Trust reports on a busy year, despite the pandemic

30 Back in business at the Old House

Introducing Mark Copley, the new manager of the Old House Museum in Bakewell

31 Out and about with the Hunter Ruth Morgan on the latest activities of the Hunter Archaeological Society

32 Bookshelf

Editor Roly Smith reviews the latest books on the history of the county

34 Our year in numbers

Planning and heritage statistics 2021/22

35 Our year in pictures

A pictorial selection of some of the things we’ve been up to

36 Picturing the Past Richard Arkwright’s Cromford

GUILBERT describes a new interpretive plan of Mam Tor, one of the original ‘Wonders of the Peak’

Anew interpretive plan of the summit of Mam Tor, charting the many natural and man-made surface features of the hilltop with unprecedented accuracy, has been published. The new plan, completed in 2018 and published at a scale of 1:2,000, is based on a photogrammetric plot of contours, derived from overlapping vertical air photographs.

Mam Tor, one of the fabled ‘Wonders of the Peak’, has long attracted attention in literature and captivated visitors. This fame was largely inspired by awe at a natural phenomenon, romanticising an extensive landslip, the great scar on the south-east flank of the hill towering over the head of the Hope Valley.

It was not until late in the 18th century that the earthworks ringing the hilltop received anything more than passing comment. Even the noted local antiquary, Hayman Rooke, paid little heed to the prehistoric fort in composing a watercolour of Mam Tor, probably in 1781, his caption making only the briefest mention of ‘an entrenchment cut by the ancients’ (see ACID 2018).

Yet in 1775, William Bray, a scholarly tourist from Surrey, paced his way around the rampart of the hillfort, and a first

plan of it appeared in his Sketch of a Tour into Derbyshire and Yorkshire (1783), one of few plans of British forts to have been put into print until then. The relationship of landslip to hillfort has intrigued countless writers, and Bray was among those preferring to envisage the drama of chunks of the fort tumbling into the dale.

In reality, however, the recently plotted contours confirm a more prosaic alternative, showing the sinuous course of the earthworks to have been contrived to complement preexisting and natural features of the hillsides, such that the two precipitous slip-scars became integral to the defensive circuit.

The hillfort on Mam Tor is a fine example nationally, its earthworks essentially comprising a pair of banks (purple in the plan) separated by a ditch, and with less regular quarryscooping just upslope of what would have been the main, inner, rampart. Reaching over 500m, this hillfort ranks with the highest dozen out of around 4,000 in the British Isles; and it is probably the highest among them known to incorporate a perennial spring, rising at 483m, its channel (blue in the plan) passing through a gap left in the encircling earthworks.

The latest plan (right) shows how two elaborate inturned entrances are positioned at the extremities of the fort, where they would best be able to control access from either direction along the ridge-crest. More than anything else, it is these characteristic entrances that imply an Iron Age attribution for this hillfort, at least in its final form, as seen today.

A fourth, simpler, gap in the western earthworks is

likely to have been broken through at a later stage, perhaps facilitating access to a series of irregular stone pits (yellow in the plan) scattered inside the fort and doubtless postdating its period of use. Those pits have not previously been recorded, and another element of the plan unfamiliar from earlier accounts is a ragged crack (grey in the plan), in places over 25m across, lying open along the north-west side of the hill, wholly outside the fort but threatening to encroach upon it. Here is a reminder that mass-movement, attested most starkly by the big landslips, has not yet done with Mam Tor.

Much of the 5.9ha of land within the hillfort is far from flat, and principal among its features, as portrayed in the new plan, are more than 200 curvilinear platforms (green in the plan), each recessed into the sloping sides of the ridge. Where best preserved, the floors of these platforms now range from about 4m to 10m across.

Some doubtless once carried buildings of some sort, while others may have been made for slighter structures or even to provide patches of level ground for various outdoor activities. At any rate, they are distributed in such density as to seem suggestive of a once-thriving settlement, and what appears to have been a terraced track (red dotted) passes between some of the western platforms.

In the north-east quarter, several platforms were sampled by excavation in the 1960s and numerous artefacts, particularly potsherds, were recovered. At the time, it came as a surprise to learn that many of these items seemed most at home in the Late Bronze Age, though subsequent excavations at other British hillforts have made this seem less remarkable.

Frustratingly, it must not be assumed that artefacts found on the platforms can be used for dating any stage in the

construction of the hillfort’s defences, which could well have developed periodically, perhaps culminating in the midst of the Iron Age. An earlier beginning of Mam Tor’s fortification cannot be discounted but some proportion of the platforms could have been made and occupied before the hillfort was conceived, so perhaps belonged to an unenclosed hilltop settlement. As if to corroborate that notion, re-interpretation of one of two narrow trenches opened across the earthworks in 1965-6 has intimated that at least one platform was buried by the building of the rampart.

For the immediate future, the greatest concern for Mam Tor remains the risk of undue deterioration inflicted by its relentless exposure to the boots of those either visiting the hilltop or walking the ridge-route where it passes through the fort. Despite the best efforts of the National Trust as landowners to stem the tide of erosion in the 1990s, the popularity of Mam Tor seems set to mean that this venerable and vulnerable hillfort, a precious archaeological resource, will pay a price through wear and tear (see feature opposite).

Yet both the quality and the complexity of the surface remains perched high on this landmark hill tell us that it deserves better, for such a noble monument surely should be counted among the archaeological Wonders of the Peak.

Footnote: A fuller explanation of the new plan is given in ‘Mam Tor, Derbyshire: new plans outlining hill and fort, internal platforms and all’, by Graeme Guilbert, in Challenging Preconceptions of the European Iron Age ‒ Essays in Honour of Professor John Collis, edited by Wendy Morrison (Archaeopress Publishing, 2022). See review in Bookshelf on p32.

On the previous pages (pages 4-6) Graeme Guilbert reported on a recent survey at Mam Tor and alluded to erosions problems from visitor pressure at this extremely popular Peak District landmark. The pressure has probably increased since the start of the Covid pandemic when parts of the Peak District National Park experienced very high visitor numbers.

It is wonderful that people are keen to visit important landmarks such as Mam Tor, but high visitor numbers can bring conservation challenges. The National Trust, which manages the site, is working hard and liaising closely with Historic England and the Peak District National Park to address some of the more noticeable areas of erosion.

In the past, the top of the hill has suffered erosion, and this is why there is a pitched stone surface around the summit and the trig point. Despite a good quality flagged path being laid over the whole summit and along the Great Ridge there are still some significant areas of rutting alongside it, as well as other eroded sections and “desire lines” on the ramparts.

Over time these will get worse; in wet conditions the ruts start to channel rainwater which increases the problem. The

Bronze Age barrow near the summit has also suffered from erosion as people stand on it to take in the panoramic views.

Temporary fences and signage will be needed to encourage people away from certain routes, to allow the vegetation to recover. So, if you are walking on Mam Tor, please play your part and observe any fences and signage. They are there for good reason and will help to protect this extremely important site into the future.

Anchor Church is an important, if secluded, landmark on the banks of the River Trent at Ingleby. It is commonly called a “cave” and most historical descriptions of it, including the Grade II listing description, imply that it is natural and somehow cut by the nearby river.

It has a recorded history dating back to the 13th century, but its present form was often cited as dating from the 18th century and that it was a creation to grace the estate of the Burdett family of nearby Foremarke Hall, which is now the home of Repton Preparatory School.

In 2021 the cave was the subject of archaeological analysis as part of the Rock-Cut Buildings Project, undertaken by the Cultural Heritage Institute of the Royal Agricultural University. This project is the first attempt to investigate habitable, rural rock-cut buildings on a large scale, and to understand their history and archaeology by creating robust typologies and developing techniques and methodologies for understanding their fabric and development. A huge number of sites have been investigated, the biggest concentrations being in the counties of Worcestershire, Staffordshire and

Shropshire, but with important outliers as far away as Cumbria and Kent.

It was clear from the start that there was no natural cave at Anchor Church. The cliffs have remained largely stable since the end of the Ice Age and all the excavations are therefore entirely artificial. This is a rock-cut building, not a cave, and had to be analysed as such. By using simple archaeological techniques adapted from those we use for conventional buildings it is possible to

The 18th- and 19th-century work is clearly evident; this constitutes the removal of two internal and two external walls, the part blocking of openings with brick and the addition of a chimney and stone and brick fireplace.

But in what structure did these later works take place? These works were an adaptation to, rather than the creation of, a space. Two narrow splayed doorways with channels for door frames and bolt holes survived in the main space, along with a very rustic debased pilaster cap in a former blind arch and the remnants of a tiny arched window.

date. This is also a site where monasticism was utterly destroyed by the Viking raid of 873 and not re-established until the founding of Repton Priory and Calke Abbey in the 12th century.

The medieval fabric of Anchor Church cannot, therefore, date from a period extending from 873 to the 13th century. This, along with the possible connection with the 9th century Saint and deposed Northumbrian king Hardulph who, according to a 16th-century printed source, had “a celle in (a clyfee) a lytell frome trent”, may suggest an early origin for much of the fabric.

These features all predate the later work and are very similar to features found in securely dated medieval rock-cut sites elsewhere. In short, if you found the doors, pilaster cap and window in a conventional building, you could with some certainty identify it as broadly Romanesque.

What makes Anchor all the more intriguing however is its history and its name, which means the church of the anchorite. It was remembered as such as early as the 13th century, but there are no records relating to its use at this

This possible survival of early fabric shouldn’t be a surprise; it is one of a number of similar sites with surviving medieval and even early medieval features and known early histories. These sandstone sites can be surprisingly durable and have something of the quality of preservation found in caves. This is why the Roman Minerva carving of Chester or the great sandstone monastery at Guy’s Cliff near Warwick have survived, unprotected for so many centuries.

The project has identified a number of such sites and some which are even earlier, but Anchor Church remains one of the most beautiful and evocative. It is noticeable that if you stay for any length of time at Anchor Church, locals will walk by and tell you: “A hermit used to live here.” Historians have long suspected this but have not analysed the fabric until now, so it is rewarding to be able to confirm with the logic of archaeological method, that they are perfectly correct.

If you stay for any length of time at Anchor Church, locals will walk by and tell you: “A hermit used to live here”

STEPHEN

The North Lees estate at Outseats in Hathersage has captured the imagination of both fervent sightseers and historical film and TV actors alike with its natural beauty and ancient charms.

The estate centres on North Lees Hall and the surrounding farmland in the north of Outseats. It is situated on upland pastures which descend from Stanage Edge, and overlooks the Hope Valley and the village of Hathersage. The second part of the name of North Lees is derived from the Old English “leah”, meaning a field or clearing.

North Lees Hall was built in 1594 by the Jessop family. It features a tall turreted tower unusual in this part of England. It is thought to have provided the inspiration for “Thornfield Hall” in Charlotte Bronte’s 1847 novel Jane Eyre. “Thorn” is an anagram for “north” and “field” equating to “leah”.

It is thought that it was built on the site of an earlier timber hall, and has a history that goes back to England’s early modern period.

The first family to live in North Lees was the legendary Eyre family of the Hope Valley in 1449. The Eyres were devout Roman Catholics and, on the walls of North Lees Hall are engravings of mottos such as vincit qui patitur which translates as “he conquers who endures”. This may well refer to the persecution that Roman Catholics endured during the Reformation. Indeed, a later resident, Richard Fenton of Doncaster, was an infamous recusant, who lived at North Lees Hall in 1580.

In 1558, the Recusancy Acts passed by Elizabeth I imposed penal sanctions on all Roman Catholics. In 1588, the year of the Spanish Armada, the manor of North Lees was searched by crown officials and Richard Fenton was one of many recusants seized and later imprisoned in London, never to return.

This strong Roman Catholic history is further testified

by the existence of ruins in the grounds of North Lees Hall, which were believed to be an ancient Roman Catholic chapel, called the “trynity chapel”.

Writers on North Lees have speculated that these ruins were built in Hathersage around 1665 and sacked by Protestant mobs in the 1680s. However, evidence would suggest that this is a different chapel, with title deeds in 1615 citing that a “trynity chapel” was part of a conveyance between owners.

The evidence therefore suggests that the chapel at North Lees existed before the 17th century and may well have been used to hold secret Roman Catholic masses by Richard Fenton or others during the Reformation.

This short history of North Lees gives an indication of the fascinating hidden stories that are etched throughout the landscape of the Peak District.

In 1878, the Derbyshire and North Staffordshire extension of the Great Northern Railway opened. A tunnel was needed to the north of Mickleover, a village now part of the western fringes of Derby. The line never lived up to the optimism of its builders and today the tunnel entrances are buried.

Geophysical survey in 2013 by Pre-Construct Geophysics revealed the presence of zones of strong magnetic variation adjacent to the former railway tunnel. It was hoped that these were the remains of structures associated with the construction of the railway.

Thanks to Derby City Council’s archaeological advisors Wessex Archaeology were brought in by Orion Heritage on behalf of their client Bloor Homes, who proposed a residential development in the area. In 2021, my colleague Paula Whittaker led a team of archaeologists to investigate these anomalies. The fieldworkers discovered the remains of seven brick kilns, which correlated strongly with the geophysical results.

Six of these kilns were simple ‘clamp’ kilns, temporary structures that are rebuilt for each firing. They were evidenced by clay surfaces that had been baked by intense heat. The extent of the heat transformation was so great that it could be seen in the buried agricultural soil that had been sealed by the kilns, and also in the undisturbed geology below the soil.

It is thought these kilns at Mickleover were used very few times, most perhaps even only once. We can tell this by the coloured stripes in the kiln surfaces that reflect the layout of the bricks in the kiln. The stacks of bricks were separated by

gaps which acted as flues to aid the firing of the kiln, which could be seen in the regular stripes of the kiln surfaces.

The final kiln was technologically more complex. It was a ‘Scotch’ or updraught kiln, which was a semi-permanent structure designed to be used repeatedly. Although two different kiln technologies were in use, there is no reason to think that the Scotch kiln replaced the clamp kilns. Both types of kiln were probably in operation at the same time.

It was easier to control the quality of bricks produced by a Scotch kiln and this may have been used for the best bricks. Scotch kilns had walls and fireboxes where fires were set to heat the kiln. This particular Scotch kiln was a large example and had foundation pads for a central wall.

Short-lived brick kilns are sometimes associated with railways and it is likely that these kilns supplied bricks for the construction of the tunnel. The clay for the bricks may have come from the railway cutting leading to the tunnel.

A probable claypit also revealed during the archaeological excavation was not large enough to supply the whole operation but is possible that this claypit was used when the initial supply of clay ran out. It may represent a temporary reoccupation of the brickworks.

After this, the brick making operation may have moved across the road adjacent to Mickleover Station, where a longer lasting brick yard is recorded on many historic maps.

Jack Goodchild, a 10-year-old member of 17th Buxton (St Peters Fairfield) Cub Scout Pack, won the Young Archaeologist of the Year Award at last year’s national Festival of Archaeology.

The award, presented to “a young person under the age of 18 who has made an outstanding contribution to community archaeology or a youth engagement project”, was one of four launched with the Marsh Community Archaeology Awards in partnership with the Council for British Archaeology (CBA).

Jack was “ecstatic” to hear he had won the award out of a talented shortlist of three young archaeologists, all of whom were scouts, from all over Britain.

Making the award, Neil Redfern, executive director of the CBA said: “Congratulations Jack, your enthusiasm for archaeology came through in your Mum’s nomination and we’re delighted that you’re so happy. You are an inspiration.”

interested in Ancient Greece, Egypt, the Incas and the Neolithic period. It’s lovely to see him so keen to share his passion with others and we are extremely proud of him.”

After a 15 month hiatus, Peak District Young Archaeologists’ Club meetings resumed in July 2021. We began with a joint session with the Millers Dale Young Rangers learning about charcoal and trying some experimental archaeology making charcoal ourselves.

We joined the “Digging Deeper” project at Under Whitle Farm, which we had previously visited several times as part of the “Peeling Back the Layers” project, to carry out some excavation. For another session, we worked once again with the South West Peak Landscape Partnership to learn about historic barns and historic building recording. The YAC members practised their building recording skills at a wonderful example of a restored field barn, Hobcroft Barn near Warslow.

When Neil asked Jack if there was anything he would like to say about why people should be inspired by archaeology, Jack replied: “I just think archaeology is really good because it teaches you about your past and shows you what you should do with your future and what to not do. It teaches you great lessons.”

Jack’s mum, Emma, related how Jack’s interest in archaeology had begun: “From an early age we have encouraged Jack’s thirst for knowledge and information, and through our own love of exploring, he’s developed a keen passion for the past and different cultures. He’s especially

Jack was recently introduced to the Young Archaeologists’ Club after joining an archaeology session run by the Derbyshire Scout Archaeology team at his Cub pack. Team Lead of the Derbyshire Scout Archaeology team, Morgause Lomas, said: “This is exactly why we created the Derbyshire Archaeology Badge, so young Scouts like Jack could pursue their love for archaeology, as well as to introduce the topic to youngsters who haven’t heard of it.”

Jack has gone on to inspire many other members of 17th Buxton Cub pack to join up to the Young Archaeologists’ Club and pursue their interest further.

Derbyshire Scouts County Commissioner Sue Harris was excited to hear Jack’s great news. She commented: “We love to celebrate all achievements within Derbyshire Scouting, so I’m thrilled to hear that Jack has been awarded the prestigious Young Archaeologist of the Year, showing that he has really worked hard on pursuing his love for the past.

“Well done, Jack.”

Rosalind Buck, National Trust archaeologist for the East Midlands, took us on a tour of the parkland at Ilam Park, near Dovedale, to identify some of the archaeological features there. Over the past decade Ilam Learning Centre has been a regular base for YAC so it was interesting to investigate the landscape surrounding it.

There have been a couple of visits to Sheffield Museums venues. We explored the archaeology and Ancient Egypt galleries at Weston Park Museum and enjoyed some archaeology-based party games for our YAC Christmas party.

On a second occasion, the group visited the museum store, which is not normally open to the public, and found out about the Bateman collection and how the museum cares for the collections it holds.

Themed sessions have included exploring Ancient Greek art, where we painted ‘vases’ in Greek style, and osteology which involved recording an inhumation burial created by volunteer leader Michelle using a replica human skeleton and ‘grave goods’ she selected from her home.

It has been fantastic restarting the meetings after the pandemic but several of our former members have passed the upper age limit or found other interests, so we are rebuilding the membership numbers. One recent joiner, Jack Goodchild,

COVER STORY: YAC member Beatrix Lawrence explores making charcoal drawings at Millers Dale

was named Young Archaeologist of the Year (see opposite page) so the quality of our members is high.

Anyone aged eight to 16 interested in archaeology can join. We are also looking for more adult volunteer leaders. See www.yac-uk.org.uk for details of your nearest branch and who to contact.

“Congratulations Jack, your enthusiasm came through in your Mum’s nomination –you are an inspiration”Morgause and Jack with his award MARTHA JASKO-LAWRENCE, Branch Leader, Peak District Young Archaeologists’ Club describes a busy year

One of the most interesting finds from the past year found in Derbyshire and recorded on the Portable Antiquities Scheme database, is this copper alloy vessel fitting, discovered by a metal detectorist in Whitwell, Bolsover.

The object dates from the late Iron Age to early Roman period, between 43 and 200 AD, and is in the form of a bull’s head. The complete PAS record can be found at: DENODA9526 at https://finds.org.uk/database/artefacts/record/ id/1007479.

The object is an almost complete, copper-alloy swing handle bucket fitting or escutcheon which comprises a bovine head with forward projecting horns, moulded rounded eyes and small sideways protruding ears. Projecting from the bovine neck is a suspension loop for the handle of the bucket or vessel. A smaller, now broken, loop is below the muzzle. The reverse of the fitting is hollow and appears to retain traces of a possible lead-based material.

It has been categorised by PhD student Rebecca Ellis as a Bovine Group 10, category 3: two rivet type of forehead and tongue piercing. At the time of recording the Derbyshire example was only the sixth known of this type. There are

other examples of this type of fitting recorded on the PAS database, the closest parallel to DENO-DA9526 being BERK-A03B79 at https://finds.org.uk/database/artefacts/ record/id/798902#, which was found in Cassington, West Oxfordshire.

While these bull’s head fittings typically date to the 1st or 2nd centuries AD, with comparable examples being excavated from the Roman legionary fortress at Usk, they have their origins in the Iron Age. However, these prehistoric examples often appear to be more stylised rather than this relatively realistic depiction.

Iron Age objects can be difficult to spot, for example DENO-765295 at https://finds.org.uk/database/artefacts/ record/id/1047474 was thought to be a modern strap slide, until further investigation by the Finds Liaison Officer (FLO) revealed it to be an Iron Age harness fitting.

The best way to get finds like these identified is by handing them in to your local FLO to be recorded on the PAS database. At the time of writing there are currently only 50 Iron Age records from Derbyshire on the PAS database, therefore if you think you may have an Iron Age object found in Derbyshire it would be very beneficial to the PAS and the local area to get it recorded.

If you would like to find out more about the Portable Antiquities Scheme, or have found any items that you would like recorded, please contact Meghan King, Finds Liaison Officer for Derbyshire and Nottinghamshire, on 01332 641903 or at meghan@derbymuseums.org

quality and significance of any archaeology on a site as well as the level of impact any development may have on it

When I was asked to contribute to “A day in the life...” in April 2022, I had been the Development Control Archaeologist for Derbyshire County Council for all of two weeks! Because of lockdowns and home working, my experience of changing jobs felt a bit strange (different job, but same location in my home office). Immediately it was great to be part of such a warm, informed, professional and open-handed team. But – getting my apologies in early – I am still very much a newbie.

I have worked in archaeology for a number of years; I was born in Yorkshire, raised in north Derbyshire and studied Archaeology and Prehistory at the University of Sheffield. While at university I went digging or undertaking fieldwork whenever I could, usually for different units in different parts of the UK, and I ended up, on graduation, running the excavation of a late Roman farmhouse at Roystone Grange, near Parwich, for the university.

Since then, archaeology has taken me to a wide variety of places in the UK (the life of an archaeologist is often an itinerant one) from Hampshire to North Yorkshire and now back to Derbyshire with detours along the way working in France, Lebanon, Syria, London, Macedonia, Kosovo and Sweden. My intention was always to get back, my ambition to raise my own family and have a place we can call home in the small part of the world that I love most.

To give some background to development control archaeology: archaeology on any site in Derbyshire, as in the rest of the country, is a material consideration for planning authorities when applications for planning permission, or requests for advice on such sites, are submitted. Put simply, the work of the Development Control Archaeologist is to: • advise the local authority when asked on the presence,

• help applicants, prospective applicants, and their contractors to collaboratively design appropriate and proportionate schemes of works, in response to planning rules, so that they are proportionate and balanced against set and agreed criteria.

So, what does this translate to in terms of what I get up to on a day-to-day basis? One day I can be out on site (that’s the bit I love), checking the work of the contract archaeologists, making sure their field work is compliant with regulations, of a high quality and to agreed specifications and national standards. I share with them my thoughts on the interpretation of the landscape and what that means for the planning application.

People often ask me if archaeology is found, does that mean the planning application is refused? The answer is not so straightforward, and the keyword is balance; I help balance the needs of development in the modern world against our collective incumbent duty to the past. One day I will be on site, the next day I can be based in the office consulting with local authorities on planning applications or checking reports, project designs or written schemes of investigation.

The job is varied and never dull. But it also helps hugely that archaeology is my passion. For me it’s not just a job but has always been a vocation, I think since being a little kid and finding part of a Lancaster bomber on Kinder Scout with my Dad or imagining Roman soldiers looking out from their fort in Chesterfield with my Grandma after buying my first vinyl single.

I am lucky to be able to spend my working life doing something I love, trying to interpret the past and assisting in that endeavour. I am doubly lucky now because, as a local lad, my own sense of self is entwined with the local past. After all, we live in the present, but our historic environment speaks to us all on many levels about who we are and where we live.

DNA analysis from bones kept at Buxton Museum is revealing important new genetic evidence, as DR TOM BOOTH, Senior Research Scientist at the Francis Crick Institute explains

Buxton Museum and Art Gallery looks after human remains excavated from a wide range of archaeological sites around the Peak District. While these collections have always been important, developments in archaeological science have meant that they have taken on additional biological potency as important bioarchives of biomolecular information.

Advances in technology over the last 15 years have vastly improved our ability to sequence DNA from the bones of ancient people. Ancient DNA continues to provide us with new insight into a diverse range of questions about the past, including reproduction between humans and other hominins, major prehistoric migrations, and familial connections in prehistoric cemeteries and tombs.

The ancient genomics laboratory at the Francis Crick Institute is undertaking a Wellcome Trust-funded project (aGB: A Thousand Ancient Genomes from Great Britain) which is aiming to sequence DNA from at least 1,000 people who lived in Britain over the last 10,000 years.

The main aim of our project is to track changes in genetic variants associated with disease through time. This will aid our understanding of these diseases by showing how frequencies of associated genetic variants have changed in response to environmental and cultural shifts.

We will also generate information on ancient individuals’ genetic sex, ancestry and close relationships with other ancient people. Analysis of an ancient person’s genetic ancestry can tell us whether they were descended from populations who lived outside Britain, which would suggest that either they were a first-generation migrant or a descendent of recent migrants.

Population-level analysis of changes in genetic ancestry

can highlight periods of major migrations. For instance, analysis of Mesolithic, Neolithic and Bronze Age human genomes from Britain has shown that there were at least two periods of migration into Britain from continental Europe which coincided with new developments in culture, economy and technology: one at the beginning of the Neolithic, around 4000 BC and another in the Chalcolithic (Copper Age)-Early Bronze Age, from around 2500 BC. This genetic ancestry information will also shed light on the character of more recent migrations between Britain and continental Europe that may have taken place through the Roman period, into the Early Middle Ages and beyond.

We have sampled a portion of human remains from Buxton Museum’s collections as part of our aGB project, which encompass a wide variety of sites and monuments in the Peak. They include Neolithic burials from Fox Holes, Deep Dale and Carsington Pasture Caves, and monuments such as Arbor Low and Five Wells; Bronze Age skeletons from Liff’s Low, Grin Low and Hindlow Cairn; Roman burials from Ecton Hill and Frank i’ the Rocks caves and a burial dating to the Early Middle Ages from Newhaven.

So far, we have found that DNA preservation in the Buxton Museum collections is generally excellent. Further analysis will help us understand how national-scale patterns of prehistoric migration and ancestry change played out among the inhabitants of the Peak District. DNA from the Hindlow Cairn burials will tell us whether they were close relatives and whether Hindlow Cairn was associated with particular families.

We also plan to radiocarbon date some of the skeletons we sample for DNA. Direct dating will address longstanding questions surrounding certain skeletons, for instance whether the body buried at the centre of the Neolithic Arbor Low monument is genuinely prehistoric or whether it is a later interment from the Early Middle Ages.

In its first two years, over 500 Derbyshire Scout Archaeology (DSA) badges have been awarded to Scouts throughout the county. The badge was launched in January 2021 and is for Derbyshire Scouts from the ages of six to 25. It involves a multitude of activities, from defining archaeology, to creating Stone Age tools and taking part in excavations.

Over 1,000 Scouts have taken part in “Intro to Archaeology” sessions, which have been offered during evening meetings and camps, giving young people a whistle-stop tour of what archaeology is through multiple fun hands-on activities.

In May last year, we were excited to introduce Natasha Billson, archaeologist and presenter of Channel 4’s Great British Dig, as the Ambassador of the DSA, who will be helping us to spread the word, getting more young people involved with the badge.

The badge is facilitated by the DSA Team, who run the Intro to Archaeology sessions as well as creating lots of exciting resources, activity ideas and running large scale projects. The biggest project has been Derbyshire Archaeological Adventures, which ran for its second year during the summer of 2022. It provides Scouts with free access and discounts to some of Derbyshire’s biggest historic sites.

The team has also led small scale excavations, the first being 10 test pits in collaboration with St John’s Primary School in Ripley, involving nearly 150 young people, who had a go at excavating. There was plenty to be found, from ceramics to glass and animal bones.

We are always on the lookout for excavation projects, so if you have anything of interest please get in touch via archaeology@derbyshirescouts.org

In October last year, the DSA Youth Committee was launched, to make sure that the DSA Badge and Team were as “youth-shaped” as possible. The youth committee is made up of 10 young Scouts from throughout Derbyshire ranging from the ages of 9-17.

One of these is Jack, a Cub Scout from Buxton who won the CBA’s Young Archaeologist of the Year Award in 2022 (see page 12). The first youth committee meeting took place at Derbyshire’s very own palaeolithic site at Creswell Crags. The young people took a tour inside the caves and took part in archaeological activities, as well as workshops and discussions on what they wanted to gain from the DSA, and ideas for future events that they had.

We are always on the lookout for more members to join our team. The great thing is that you don’t have to be a Scout or have any scouting experience. If you’re a Scout already, you don’t need any archaeology experience. We’re just looking for enthusiastic people who want to inspire young people to engage with Derbyshire’s archaeology.

More information about the badge and team can be found at www.derbyshirescouts.org/activity/archaeology. We can also be found on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and YouTube just search Derbyshire Scout Archaeology.

Britain’s Fortified History enabled him to pursue yet another of his passions, that of why and how castles were built. “It’s always interested me why, for example, in the Civil War of the 17th century, it was thought necessary to destroy castles which were built three or four centuries before,” said Sam.

Sam Willis could be described as a modern-day Indiana Jones, as an award-winning historian, archaeologist and adventurer. He is also one of the world’s leading authorities on maritime and naval history.

Sam’s work has taken him on adventures all round the world, and he has made more than 10 TV series for the BBC and National Geographic that have been watched by millions of viewers.

He has made films and documentaries on such diverse subjects as castles, weapons, pirates, highwaymen, shipwrecks, submarines, Antarctic exploration, invasions, the Spanish Armada, and the First and the Second World Wars.

His 2014 three-part series for BBC4 entitled Castles:

He added: “I’m particularly fond of the history and archaeology of the Peak District, not least the magnificent Peveril Castle at Castleton. So few castles from the earliest wave of Norman invaders and castle-builders survive and yet here at Peveril you have a magnificent stone keep that was built by Henry I in 1176.

“It literally towers over the landscape and is such a powerful reminder of what the Normans were trying to do –not just conquer the land but demonstrate to everyone that they were in charge.

Sam continued: “Bolsover is another castle that I’m very fond of – because it is so different to Peveril. More than four centuries later and you can see how the whole conception and techniques of castle building has changed. Part stately

home, part castle and, importantly, full to the rafters with ghosts.

“I’ve always wanted to make a series called Britain’s Haunted History. No luck so far, but I’d definitely start with Bolsover!”

Sam, now 45, was born and brought up far from the sea in St Albans, Hertfordshire, and moved to his present home in Exeter after studying history and archaeology at university there, graduating in 2000.

“Doing things entirely the wrong way round” as he explains, he earned a PhD in Naval History from the same university, studying under Prof Nicholas Rodger. He then went on to research for an MA in Maritime Archaeology from the University of Bristol, where he studied under Time Team’s Prof Mark Horton. He is now a visiting Fellow in Maritime and Naval History at the University of Plymouth and a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries.

In 2013, Sam was navigator on the nine-man crew led by Dan Snow who recreated John Wesley Powell’s epic 1869 voyage down the uncharted Colorado River through the Grand Canyon in tiny wooden rowing boats, which was broadcast by BBC2 in January 2014. “It was the trip of a lifetime,” said Sam. “It was very, very hot and tough going for sure, but I loved every minute of it.”

So where did his abiding love of the sea and ships come from? Sam recalls: “Although my father was an accountant, our house was filled with pictures of naval officers and ships, because both my grandfather and great grandfather served in the Royal Navy, so I can only think I may have inherited it from them.”

His life of history, travel and adventure began more than a decade ago with an archaeological excavation of a mass grave of sailors from the time of Nelson’s navy at English Harbour in the Caribbean island of Antigua, as recorded in Nelson’s Caribbean Hell-Hole, a 2012 film for BBC4.

Since 2016, Sam has hosted the chart-topping and live “Histories of the Unexpected” podcast show with Prof James Daybell and has written several books based on the series with his co-presenter, notably the fascinating pot pourri of historical facts entitled Histories of the Unexpected (Atlantic Books, 2018).

As Sam explains: “It’s an entirely new way of thinking about history – challenging yourself to think about how and why things are as they are,” Sam explains. “It’s a bit like a Swiss cheese – there are far more holes than cheese, the challenge is filling in the holes!”

Sam’s latest venture is The Mariner’s Mirror Podcast –the World’s No.1 podcast dedicated to maritime and naval history.

“I’ve always wanted to make a series called Britain’s Haunted History. No luck so far, but I’d definitely start with Bolsover!”Sam meets a medieval knight outside Bamburgh Castle in Northumberland Sam outside the gatehouse of Caerlaverock Castle in Dumfries and Galloway

Timbers traversing the sand bar. The grey alluvial clay post-dates the structure

The timber post alignment found in the River Trent at Swarkestone has interesting parallels, reports KRIS

KRAWIECDuring the monitoring of soil removal in May 2021 at the Tarmac sand and gravel quarry at Swarkestone, York Archaeology recorded the remains of an 80m long timber post alignment. The work was prompted by Derbyshire County Council’s archaeological team.

An excavation was carried out and a total of 105 upright oak posts were recorded in a broadly north-west to south-east alignment. The posts traversed a sand bar and palaeochannel that form part of the wider Trent floodplain and continue beyond the current limit of extraction.

A single sample was submitted for rangefinder radiocarbon dating which returned an Iron Age date (c.789 to 544 BC). A subset of 35 of the timbers were also submitted for dendrochronological dating which unfortunately did not cross-match with the regional dating curve. However, three groups of timbers did cross-match within the timber group assessed which indicates possibly three phases of felling for

the construction of the alignment. In addition it seems clear that some of the timbers were cut in half and used in different parts of the alignment.

A curious feature of the Swarkestone timbers is each post had been trimmed to a flat base and inserted into a posthole cut into the sand bar. Such alignments dating to the Iron Age have been excavated in other regions with the largest being that excavated at Fiskerton in the Witham Valley in Lincolnshire, with other examples excavated in the Waveney Valley in Suffolk, at Beccles, Geldeston and Barsham. The Suffolk examples are considered as monuments, with no superstructure to speak of and no indication of a practical revetment function. The timbers in these instances were too large to suggest a trackway, and the surrounding environment was shown to be seasonally dry, therefore making an elaborate, elevated causeway unnecessary. In the case of Fiskerton, the structure contained both mundane and ceremonial elements, with ground-level pegged walkways as well as votive metalwork deposition.

A recent discovery at Tucklesholme Quarry, Staffordshire recorded a similar alignment of posts, although the preservation of the timbers was more variable due to the context of the site. Here there were two alignments, comprising 49 and 37 posts respectively, which were trimmed to a flat base and inserted into postholes. Only six timbers survived in the first alignment and 17 in the second, with the Iron Age date provided by radiocarbon date determination. This site provides the closest parallel to the Swarkestone timbers.

The Swarkestone alignment represents the remains of a linear monument traversing the complex and dynamic floodplain of the River Trent. It has echoes of the long lines of pits recorded elsewhere in the valley which are considered to represent the boundaries between territories and can extend for hundreds of metres. These features often extend to the floodplain edge and are located in close association with significant landscape features such as river confluence zones.

The structure at Swarkestone represents a rare survival for the region and the upcoming further study should provide valuable insights into the later prehistoric period in the valley.

As part of a planning application for a proposed extension at Willington Quarry, York Archaeology were commissioned by JBA Consulting, on behalf of Cemex UK Operations, to undertake a trial trench evaluation. This was done in order to provide further detail to understand the significance of known heritage assets and the potential archaeological resource at the request of Derbyshire County Council’s archaeological team.

A geophysical survey was also carried out which identified a rectangular enclosure, and a previous study carried out by Guilbert and Garton in 2007 identified a possible prehistoric burial mound within the higher gravel terrace area. The mound, known as “Hull Bank”, had not been subject to intrusive investigation and therefore its age and character were not precisely known.

A series of trenches were excavated in order to characterise both the mound and the enclosure. Two trenches were excavated across the mound which provided an open section through the upstanding material and revealed a curvilinear ditch, which was also excavated to determine its age and character. A series of bulk samples and material for Optically Stimulated Luminescence (OSL) dating, which records the last time the sediment was exposed to sunlight,

were recovered from the terrace gravels, mound and ditch.

The underlying terrace surface returned dates within the Mesolithic period, indicating the mound material directly overlies a post-Mesolithic land surface; a situation recorded at several other sites recorded in the Trent valley. An OSL sample from within the mound material returned a late Neolithic-Early Bronze Age date (c.4050-1920 cal BC).

This date range is broad but does fall within the period when round barrows were being constructed, typically covering a period from 3000 BC to 1500 BC, with the main period of construction being around 2000-1500 BC.

During the 1970-1972 excavations to the north-east of the site, sections were recorded through two barrow ditches, which discovered the remains of mound material.

In contrast to the Swarkestone Lowes barrows, no features were recorded beneath the mound material at Willington. The lack of human bone recovered from the burials is likely due to the acidity of the soil, and the same would probably apply for the mound at Willington. Indeed, no human remains were recovered during the evaluation.

The enclosure, which was located to the south-west of the mound, has subsequently been subject to open area excavation and is firmly 2nd to 3rd century Roman in date. Environmental samples from the Roman features show evidence for the processing of oat, barley, and wheat crops at the site. The enclosure may have respected the edge of the mound during its use, although subsequent erosion and deflation of the mound material has seen the soil ‘creep’ over a wide area.

This limited investigation into the Hull Bank mound has confirmed the monument is the remnant of a round barrow, one of the few upstanding and unexcavated barrows left within the Trent Valley. This work also represents the first time OSL dating has been carried out for this feature type within the valley, the success of which is of importance given the poor preservation of charred material and bone from such monuments. The work was critical to confirming the identification of the mound as a monument and provided a unique opportunity to investigate the feature using a combination of limited excavation and specialist dating in order to understand its significance. This further understanding has meant the monument and its immediate environs have been preserved in situ and will not be impacted by development.

Plan of site showing trench locations and geophysical anomalies

The evaluation dig underway (above) Samian ware from the site (right)

GEORGIA

In 2021, University of Leicester Archaeological Services (ULAS) undertook an archaeological trial trench evaluation and subsequent strip, map and sample excavation on land between King’s Newton and Melbourne, in advance of residential development. This was thanks to South Derbyshire District Council’s archaeological advisors.

The initial trenching was undertaken in January and revealed previously unknown buried archaeological remains dating to the late Roman period. Further investigation uncovered the remains of a small-scale rural industrial complex, notably including a large, stone-built malting oven and six small industrial features including a possible stonelined lead working furnace.

Across the base of the malting oven, a layer was identified which comprised a compact, charcoal-rich silt with lenses of redeposited natural clay containing germinated glume wheat bases and detached embryos. The sprouted embryos still attached to the grain could be approximately measured and were all shown to be of the same length, indicating the germination of these cereal grains was a controlled and deliberate act, indicating a function associated with the

malting process, in this instance, for the brewing of wheat beer. This feature appeared to have either collapsed or been deliberately demolished during antiquity and pottery dating to the Anglo-Saxon period was found in its upper layers, perhaps indicating a date for its destruction.

Unfortunately, the small furnace did not contain any evidence of its use. However across the development site high temperature residues, fuel ash and small quantities of lead were recovered which are characteristic of waste produced during smelting and are indicative of lead working in the area.

The extraction and processing of lead ore is known at sites throughout Roman Britain and the Peak District was one of the major sources of lead ore. However, due to the amount of lead already in circulation it is likely that lead working in this period focussed on re-use of existing lead rather than processing newly-extracted ore.

The remains of two possible late Roman sunken featured buildings were also identified, possibly used as workshops associated with the industrial activity. Structures of this type dating to the Roman period are not well understood yet, and so their recording at this site will help to inform future archaeological works throughout Britain.

A large assemblage of late Romano-British pottery was recovered and comprised a range of locally made wares alongside imported types such as Samian. A ceramic games counter was recovered, as were fragments of blown window glass, box flue tiles and a handle belonging to a small glass jug.

The archaeological remains were observed to extend beyond the eastern, western and southern limits of excavation and represent the first evidence of structural Roman archaeology found in the village.

The work undertaken during this project has shown that, during the late Roman period, people were living and working in Melbourne, malting grain to make beer, processing crops and smelting lead. It has also identified the remains of three possible late Roman sunken featured buildings, a building tradition that we are still in the early stages of understanding for this period. The finds from the site show that people used both locally made and imported pottery as part of their daily lives, and the presence of window glass, wall and roof tiles, and box flue tiles associated with a hypocaust are all indicative of a high status residential area nearby, possibly even a villa.

Extensive restoration work was recently completed to the east window of the Chapel at Haddon Hall, including glass conservation and stonework repairs. The work was funded by grants from the Historic Houses Foundation and Historic England Cultural Recovery Fund.

The work involved the careful removal, repair and conservation, and reinstatement of the historic glazing, and associated repair of the historic masonry tracery and surrounding stonework within the Chapel’s east window.

The approach to the repair and conservation work was to carry out as little as possible but as much as necessary to secure the longevity of the east window, its historic stonework and glazing. Given the importance of the east window, both as a fine example of medieval stained glass and to the Manners family, the scope considered some enhancement of the window.

The Chapel dates from the 13th-century, with later 14thand 15th-century alterations. Internally, the Chapel has fine “grisailles” wall paintings in the nave. The Chapel, like the rest of Haddon Hall, is constructed of a mixture of limestone and gritstone and was subject to restoration in the 20th century.

The window itself is of five lights in the Perpendicular Gothic order, with gritstone stone mullions and tracery. The surviving stained glass in the window is thought to be 15thcentury and is attributed to stained glazing works by John Thornton of Coventry (c.1427-30).

Much of this glass was destroyed or stolen during the 19th century, and the majority of the surviving stained glass was returned to the window in 1858. At this time the stained glass was not returned to its original location but reformatted and inserted alongside large panels of plain diamond “quarries” (the architectural term for diamond-shaped panes of glass), to fill in missing areas.

As part of the work, fragments of the 15thcentury stained glass were found to exist

in the hall’s estate store. These have been reviewed, catalogued and taken for further analysis and conservation by the stained glass specialist as part of the project.

Conservation cleaning was carried out to all the glazing removed from the window.

Archival research and review of appropriate levels of conservation was carried out through reference materials and consultation with academics Tim Ayres and Heather Gilderdale Scott.

Numerous reviews were undertaken with the contractors to identify the different ages of glass, graffiti, and brush marks to prioritise the important pieces to retain.

The design team reviewed a number of rearrangements to determine the most appropriate level of conservation. The restored window rearrangements included:

• retention of the 19th-century glass in the outer lights

• introduction of 45 new ‘seaweeds’ (seaweed is the term used to describe diamond panes with a decorative floral motif)

• introduction of ground and mounds to the missing evangelists

• introduction of painted lines where there was clear contextual information from adjacent pieces of glass.

One key move was slightly raising the figure of Christ so the head did not lie across the ferramenta (the structure of metal bars which support the glazing). This was particularly important as the cleaned glass revealed such a finely painted face.

The restoration should ensure that the east window can continue to be viewed and appreciated by the family and public for years to come. The chapel is now re-opened so the public can view the conservation work.

With thanks to the design team, contractors and the grant-giving bodies, Historic Houses Foundation and Historic England.

(top) and after it was

Radbourne Hall, built in 1742 for the Pole family and lived in by their descendants ever since (see ACID 2022), had fallen into a sad state of disrepair since its last major renovation in the 1950s.

Now a three-year restoration project involving the enhancement and protection of the building’s architecture has won the prestigious Restoration Award from the Historic Houses Association.

As well as essential structural works to the roof and services and utilities, windows were reinstated and an entirely new staircase constructed on the house’s garden front, giving the saloon on the principal floor access to the grounds. A 20mm gap separates it from the historic fabric of the Palladian mansion, meaning the listed building did not have to be directly disturbed.

The prestigious award, sponsored by Sotheby’s auction house, was created in 2008 and recognises outstanding examples of the work being carried out by private owners, up and down the country, to protect and preserve the historic buildings in their care. This keeps them fit for purpose as family homes, and often as places for the public to enjoy, learn, or stay, in addition to keeping them standing for future generations.

Ben Cowell, Director General of the not-for-profit Historic Houses co-operative association, said: “I congratulate Lady Chichester on her terrific achievement at Radbourne and hope it will spotlight the plight of places still struggling to emulate her efforts.”

“The award is an important way of illustrating what is done by private owners, in almost all cases without any help from the taxpayer, to keep the nation’s heritage safe. It is estimated that there are £1.4billion of outstanding repairs

needed across 1,500 Historic Houses member properties around the UK, of which £500million are urgent.

“Our members who were lucky enough to receive government money from the Culture Recovery Fund, created as part of the response to Covid, have been able to achieve amazing things – new roofs, for example, which will provide huge value by safeguarding the ability of these places to employ local people in tourism and hospitality and thrive as businesses.”

Ben added that private owners of historic houses didn’t face a level playing field, compared to publicly or charitably owned ‘museum houses’ on all sorts of issues from rates to planning.

“There is still much work to do to make sure we don’t return to the bad days when much of our national heritage in private hands was lost forever.”

Anew Augmented Reality (AR) app about Errwood Hall has been developed by the South West Peak Landscape Partnership (SWPLP) and Derby-based digital media company Bloc Digital, thanks to funding from the Peak District National Park Foundation and The Big Give Christmas Challenge 2021.

It includes a 3D model of how the hall once looked –complete with AR capability – and also a 3D image of how the hall looks today, fact files and sound files for audiences to peruse.

Catherine Parker Heath of the SWPLP said: “It is amazing what has been achieved within a limited budget and timeframe and the result is a multi-media app that everyone can enjoy. One of the aims behind the creation of the app is to engage new audiences in the heritage around them.

“A feature of it is that not only can it be used on-site but it can be activated off-site too, so those who cannot get to see the ruins in person can still see it in all its 3D glory!”

Katy Stead, head of content development and production at Bloc Digital said: “We’re delighted to be part of this project using our digital visualisation and immersive technology to help bring Errwood Hall’s rich history to life in the palm of a hand.”

The standalone app is free and available to download on the App Store and Google Play.

1828, possibly with his brother and his wife and young family. The 34 drawings and watercolours were pasted into a large format volume with half calf bindings made by Colnachi and Sons of Pall Mall. The pictures have been arranged as a tour, and therefore are a little out of date order.

The last thing I’d imagined I’d be doing during lockdown was buying a new acquisition. So my thanks go to colleagues at Peak District Mining Museum in Matlock Bath for bringing the sale of this album of drawings “mostly of Matlock”, from Wooperton Hall in Northumberland, to my attention.

The auction house catalogued three separate volumes; the first was inscribed to Mary Twopeny, and the album we acquired was the third of them. Romantically I thought she was the artist, but Prof David Hill, an expert on Victorian paintings, suggests that this is the work of David Twopeny (1804-1875), her husband and also her first cousin.

It records tours of Derbyshire in August 1827 and June

We follow the journey from the Rock Houses at Mansfield and arrival at Ashover in June 1828, with distant views of Ogstone Hall and Ford House in high summer. Roads and lanes are busy with travellers and wagons, field hedges meticulously shown dense with foliage, while people and animals give scale. Working mostly in pencil, the application of wash provides highlight and texture.

On June 7, Twopeny arrived in Matlock staying at the New Bath Hotel. An interesting drawing is of an ancient lime tree with a circumference of 95 feet in the gardens, now only remembered in local street names. He draws High Tor and the ferry on the River Derwent. Significantly there are two drawings of the lead mines at Lady Gate and Side Mine.

On June 10, Twopeny stopped at Haddon Hall, having

visited the year before and, probably staying in Bakewell, paints views across the water meadows showing Bakewell Church deprived of its spire in 1812, and a sweeping landscape from below Hulme Hall. There is a diversion to Stoney Middleton and, stepping back in time to 1827, to Peak Cavern and the rope walk at Castleton.

On June 12, 1828, he sees the ruins of the Orphanage House at Litton Mill, derelict after a fire in about 1815. The mill’s waterwheel was still an engineering marvel. He draws the imposing limestone crag at Raven’s Tor before climbing

to Monsal Head, recording a family of travellers struggling up the hill in a view of the valley, then without the Headstone Viaduct of course. Two views of Dovedale from 1827 complete the tour, capturing both familiar views and the very unusual.

Albums are always difficult to share with all the visitors, but each page has been photographed and will be included in the industry exhibition. Several people have helped research this album. We are exceedingly grateful to each of these people, and their enthusiasm for this album.

The Barrow Knight section explored Thomas Bateman’s Peak District excavations and included some of his handwritten excavation notes (left) The exhibition emphasised the family roots of the Bateman collection and its continuing legacy (right)

over 200 prehistoric barrows in the Peak District earning him the nickname “The Barrow Knight”. He died at the early age of 39 and his collection passed to his son Thomas William Bateman (1851-1895).

In ACID 2021, with Sharon Blakey, I wrote about Sheffield Museums’ plan to mark the bicentenary of the birth of Victorian antiquarian Thomas Bateman with an exhibition at Weston Park Museum. At the time of writing our plans were already in flux due to the Covid-19 pandemic so I had to be non-committal about the opening date and the content. Our aim was to change the perception of the Bateman collection as an assemblage of local archaeological material and show that the original collection was vast in numbers of objects and breadth of subjects. The final exhibition Brought to Light: The Remarkable Bateman Collection, which opened in May 2022, certainly achieved this aim, showcasing over 270 items from Sheffield’s collection, complemented by nearly 40 objects loaned from other institutions.

Thomas Bateman (18211861) was an antiquarian whose collection was held at his private museum at Lomberdale House in Middleton-by-Youlgreave. Best known locally as a pioneer of early archaeology, he excavated

In 1876, he loaned part of the collection to Weston Park Museum in Sheffield. The museum subsequently purchased this material in 1893. The dispersal of the remaining collection took place through a series of sales in 1893 and 1895.

Research for Brought to Light revealed the extent to which Bateman items are spread across the different collections at Sheffield Museums. The popular perception was that the Bateman collection was formed mainly of archaeological material, an impression reinforced by the catalogue published by the museum in 1895 that detailed only the Bateman “antiquities”. The natural history collection has not been as well documented, but this too contains many interesting and significant specimens, including two complete ichthyosaur fossils.

Generous loans from other museums showed the diversity of the original collection. The University of Manchester lent one of several ex-Bateman collection medieval illuminated manuscripts held at John Rylands Library, along with the Trier book binding, an exquisite ivory-inlaid book cover dating to 900-1300. Bateman’s interest in ethnography was highlighted by loans from Pitt Rivers Museum and the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of Cambridge.

One exciting discovery was a letter written by Thomas Bateman, held in the Special Collections Library, University of Sheffield. The museum’s archive contains 10 volumes of letters sent to Thomas Bateman, but letters he wrote to others are much rarer.

Although the exhibition closed in January, our intention is to keep the legacy going with a small display in the permanent archaeology gallery and to share the research online.

LUCY GODFREY of the Derbyshire Historic Buildings Trust (DHBT) reports on a busy year, despite the pandemic

As for many organisations, the pandemic has been a challenge for the Derbyshire Historic Buildings Trust (DHBT) over the past 12 months. Nonetheless, the Trust has very been active, as the following events will show.

The Grade II* Station near Alfreton is one of the world’s rarest rural railway stations. Despite 40 years of total neglect, the 1840 building remained largely intact and unchanged. With financial support from Historic England and the National Lottery Heritage Fund, we appointed a specialist

contractor (ASBC Heritage & Conservation Specialists) to undertake urgent repair works. Work started in midOctober with scaffolding going up overnight on the trackside elevation of the building. Time pressure was great: Network Rail only allowed “possession” of the mainline past the station for a few hours. But all went smoothly, and re-roofing was achieved by June last year.

In May 2022 we received the wonderful news that our second Lottery application had been successful and we’re now raising £250,000 to ‘match’ their £667,000 pledge of funds to finish the restoration.

In July 2021, the owners kindly let us hold a summer garden party in their home in Market Place, Wirksworth. The house was built by the Duchy of Lancaster in 1750, which also bought the adjacent Hopkinson’s House, to incorporate the garden of that property too. Hopkinson’s House, restored by DHBT between 1981 and 1985, is now the HQ for the Trust.

At the party, we displayed a recently conserved fragment of decorative plaster found in the “garage” – the former Hall chamber of the house built in 1631 by William Hopkinson.

We’ve also run several popular, free Wingfield Station tours. Further dates are on our website, so people can see the impact of the capital works so far.

Our Derbyshire visits included trips to Sudbury village and Gasworks; Bonsall village; Bennerley Viaduct; Ashbourne; St Wilfrid’s Church, Barrow upon Trent, and Milford.

We’ve also launched a YouTube channel showcasing some of our projects and explaining what we do. Find our channel by searching for Derbyshire Historic Buildings Trust and subscribe so you don’t miss anything.

If you’d like to find out more about DHBT or support our project at Wingfield Station, please visit our website: www.derbyshirehistoricbuildingstrust.org.uk

Wingfield Station under scaffolding in October 2022

Inset: The station as it looked in October 2020

July saw us back in Castleton to see Colin Merrony’s site at New Hall, a now demolished 17th-century house. Numerous fragments of plasterwork suggested fine ceilings. The walls however have been thoroughly robbed, making it difficult to disentangle the sequence of events.

Bakewell Old House Museum is enjoying its first full season, post-Covid. We’ve been welcoming back our local visitors, and engaging tourists to Bakewell and the wider Peak District with our amazing local stories.

This has coincided with a new museum manager, Mark Copley, starting at the museum, who is looking forward to developing the museum’s relationship with the local community in particular. Mark has worked in museums in Hertfordshire, Cambridgeshire and London before moving up to the beautiful Peak District. He commented: “Look out for new exhibitions, talks and other events – especially at Halloween and Christmas.”

Much of the focus of the museum last year concentrated on the Queen’s 70th Jubilee. This season, we have our “Celebrating 70: Gems of the Collection” exhibition, which showcases some of our volunteers’ favourite items from the

costume collection. Children have been colouring-in bunting and people of all ages have been writing about their thoughts and memories tied in with the Queen’s 70-year reign.

In June, we had over 60 neighbours at our Jubilee Street Party. Fabulous homemade food was created – all with a red, white and blue theme, of course!

As well as museum visits, we provide engaging guided tours of Bakewell for groups of all ages. These cover AngloSaxon, Tudor, Medieval, and Victorian Bakewell. And all this is on top of our weekly “Secrets and Legends” tour on Thursdays and some Tuesdays. Bakewell has so much to offer.

The museum provides an active and friendly environment, so if you’re looking for some volunteering opportunities, there’s something for everyone. Similarly, the Bakewell and District Historical Society, which operates the museum, is a wonderful way of meeting like-minded people who are passionate about the Peak District.

Contact Mark Copley email: markc@bakewellhistory.com; Tel: 01629 813642 or see our website www.oldhousemuseum. org.uk for information on the various volunteer roles and details on how to join the Society.

The Hunter Archaeological Society, active across South Yorkshire and north-east Derbyshire, takes seriously its role in keeping members up to speed with current archaeological work in the region.

Throughout the year, in addition to a programme of talks, we arrange visits to fieldwork projects and excavations, and benefit from the effort site managers put in to give us a comprehensive overview of their work. Sometimes they can offer members opportunities to dig or help in other ways. For example, a volunteer group is currently helping with postexcavation work by washing bones and measuring glass.

So, to give a few examples of visits we did last year: In the spring, we visited the World War 2 Prisoner of War camp at Redmires, high up on the western edge of Sheffield, where University of Sheffield archaeology students were working on projects they had devised. A repurposed World War 1 training camp, from 1939 to 1947 it housed several thousand German and Italian PoWs. The concrete hut bases are still very clear, though badly in need of more protection. The students later did a poster presentation of their results.