A CROSSROADS

CULTURES

A new series inspiring dialogue, connection, and activism about the most pressing issues of our time.

A new series inspiring dialogue, connection, and activism about the most pressing issues of our time.

SERIES KICKOFF: April 26, 2023 | 5:30 pm | 21+ ECO-SCIENCE SOCIAL

Short talks from Penn experts Susanna Berkouwer, Ph.D., Wharton; Barri Gold, Ph.D., Environmental Humanities; Jon Hawkings, Ph.D., Earth and Environmental Science; and Kathy Morrison, Ph.D., Anthropology • Local vendors and action groups Tour the CAAM Labs • Zero-waste bites and drinks (first drink on us)

SPECIAL GUEST: JOY HARJO

Internationally renowned performer and writer of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation and U.S. Poet Laureate, 2019–2022

Members of the Fellows Circle and above receive complimentary admission, a copy of Joy Harjo’s memoir Poet Warrior, and a chance to meet her during a post-event book signing. To join the Fellows Circle, visit www.penn.museum/membership.

Co-sponsored by Environmental Innovations Initiative at the University of Pennsylvania and CxRA. Ms. Harjo’s participation is made possible by Carrie Cox, PAR, and members of the Director’s Council.

www.penn.museum/seeds

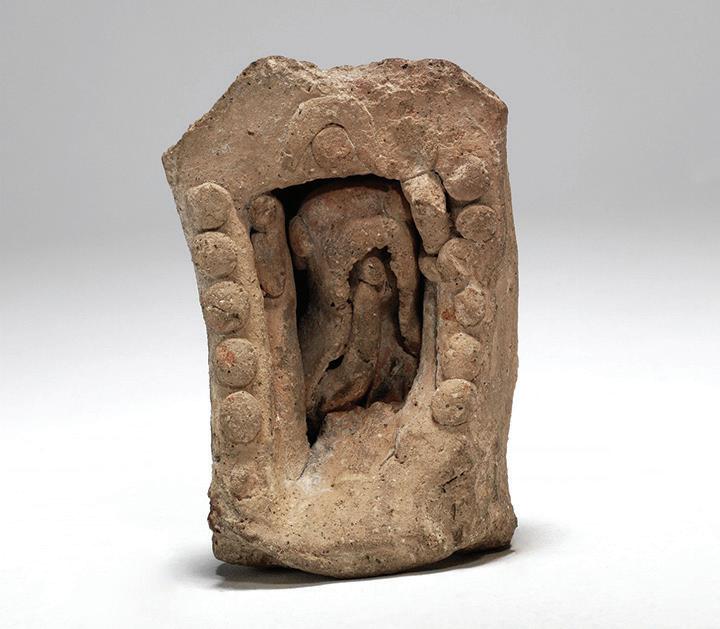

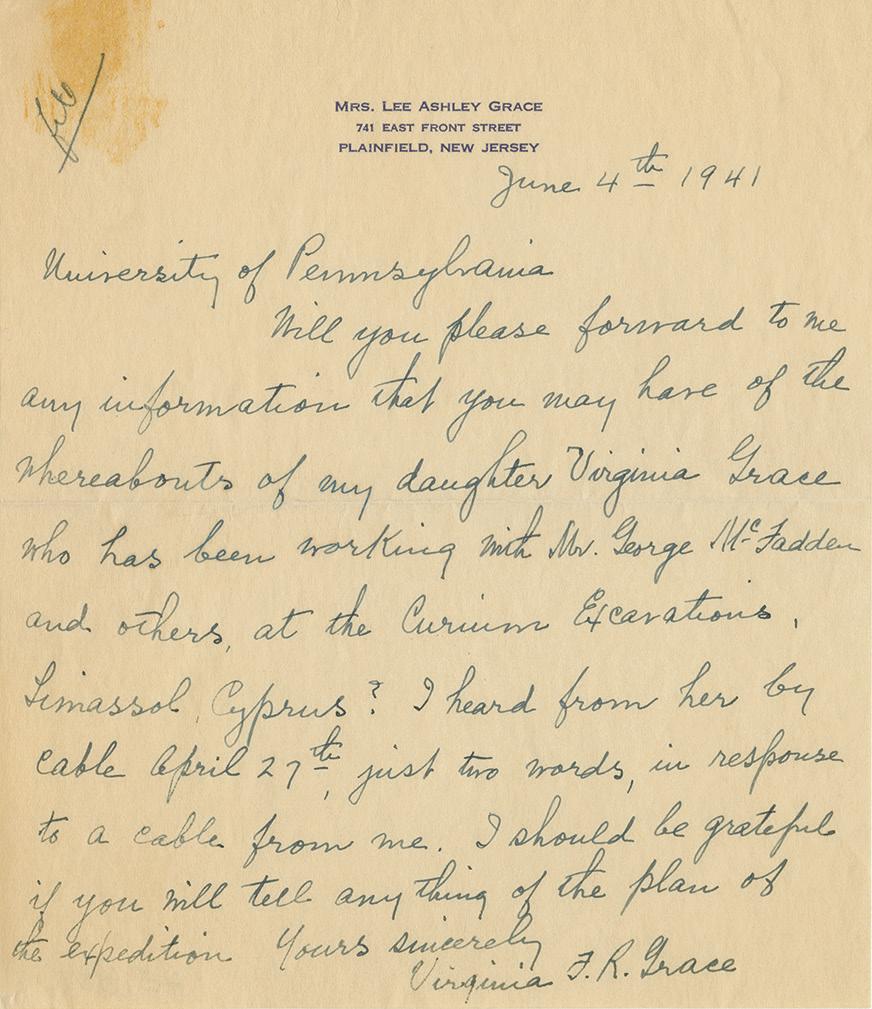

By Virginia Herrmann and Adam Smith58 Prayer and Protection

RITUAL ACTS AND MAGICAL OBJECTS IN THE ANCIENT EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN

By Eric Hubbard By Joanna S. Smith66 Family Portraits

FROM PALMYRA TO PHILADELPHIA

By Lauren Ristvet By Joanna S. Smith74 Archaeology, Archives, and Empire

By David MulderWINTER 2023 | VOLUME 64, NUMBER 3 DEPARTMENTS

By Joanna S. Smith By Joanna S. SmithPENN MUSEUM 3260 South Street, Philadelphia, PA 19104-6324 Tel: 215.898.4000 | www.penn.museum

The Penn Museum respectfully acknowledges that it is situated on Lenapehoking, the ancestral and spiritual homeland of the Unami Lenape.

Hours Tuesday–Sunday: 10:00 am–5:00 pm. Closed Mondays and major holidays. Museum Library Call 215.898.4021 for information.

Admission Penn Museum members: Free; PennCard holders (Penn faculty, staff, and students): Free; Active US military personnel with ID: Free; K-12 teachers with school ID: Free

Adults: $18.00; Seniors $16.00; Children (6-17) and students with ID: $13.00; Children 5 and under: Free.

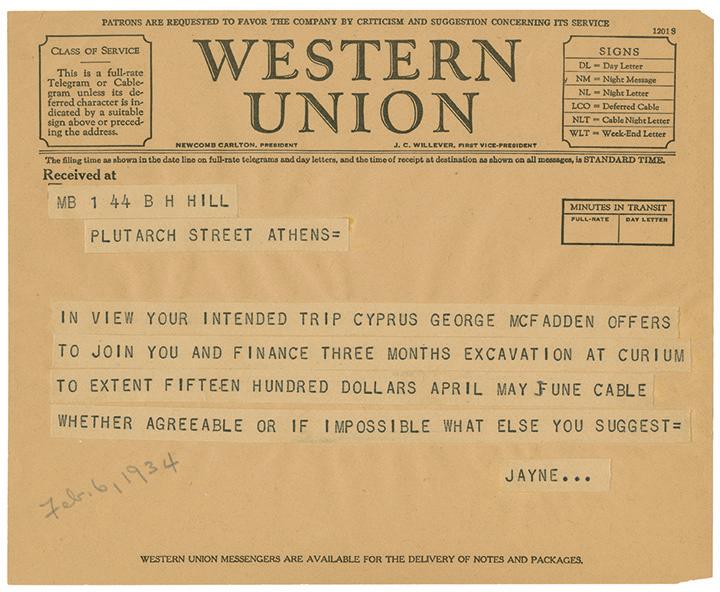

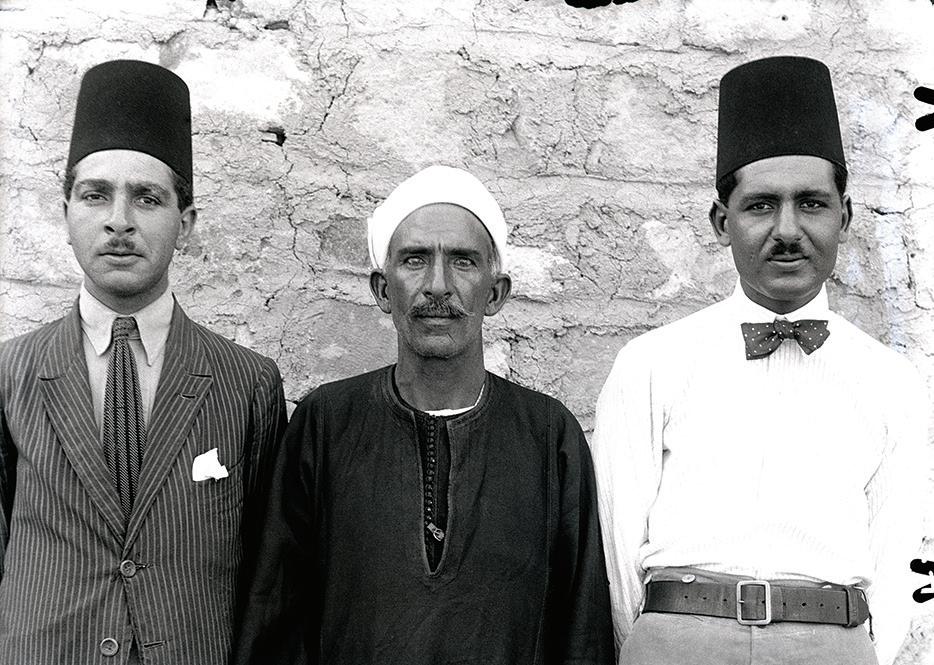

EXCAVATING BETH SHEAN IN BRITISH MANDATE PALESTINE By Eric Hubbard

86 On the Rim of a Volcano

A WORLD WAR II STORY FROM THE ARCHIVES

By Janessa Reeves2

Above: Cylinder Seal, Beth Shean, 1500–1250 CE (29-104-138).

On the Cover: Opening weekend visitors taking in the scale of the restored sarcophagus from Beth Shean in the Eastern Mediterranean Gallery. See page 36. Photo by Eddy Marenco

GUEST EDITORS

Lauren Ristvet, Ph.D.

Virginia Herrmann, Ph.D.

Eric Hubbard

Joanna S. Smith, Ph.D.

PUBLISHER

Amanda Mitchell-Boyask

ASSOCIATE PUBLISHER

Emily Holtzheimer

ARCHIVES AND IMAGE EDITOR

Alessandro Pezzati

GRAPHIC DESIGNERS

Colleen Connolly

Christina Jones

COPY EDITOR

Page Selinsky, Ph.D.

ACADEMIC ADVISORY BOARD

Marie-Claude Boileau, Ph.D.

Richard Leventhal, Ph.D.

Simon Martin, Ph.D.

Janet Monge, Ph.D.

Kathleen Morrison, Ph.D.

Lauren Ristvet, Ph.D.

C. Brian Rose, Ph.D.

Page Selinsky, Ph.D.

Stephen J. Tinney, Ph.D.

Jennifer Houser Wegner, Ph.D.

Lucy Fowler Williams, Ph.D.

CONTRIBUTORS

Jessica Bicknell

Marie-Claude Boileau, Ph.D.

Jennifer Brehm

Kris Forrest

Jo Tiongson-Perez

Alessandro Pezzati

PHOTOGRAPHY

Francine Sarin

Jennifer Chiappardi

Colleen Connolly

(unless noted otherwise)

INSTITUTIONAL OUTREACH MANAGER

Thomas Delfi

© The Penn Museum, 2023 Expedition® (ISSN 0014-4738) is published three times a year by the Penn Museum. Editorial inquiries should be addressed to expedition@ pennmuseum.org. Inquiries regarding delivery of Expedition should be directed to membership@ pennmuseum.org. Unless otherwise noted, all images are courtesy of the Penn Museum.

THE EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN GALLERY, opened November 19, 2022, celebrates the Penn Museum’s history of excavation and research in the cultural crossroads that includes modern-day Israel, Jordan, the Palestinian territories, Syria, Lebanon, and Cyprus. This special commemorative issue of Expedition includes essays by curators and graduate students that shed new light on this region—from essays about excavations in the 1920s and 1940s to new analyses of “Phoenician” ivories.

Initial discussions about the intellectual trajectory of this gallery came out of a working group in 2016 and 2017 that included professors and researchers from across Penn. Many who contributed to those discussions— including Professors Robert Ousterhout, C. Brian Rose, Thomas Tartaron, and Julia Wilker—broadened the chronological and geographical scope of the project, expanding the focus from the previous “Canaan and Ancient Israel” gallery to the region as a crossroads, encompassing the Eastern Mediterranean from the Late Bronze Age to the Islamic period.

After a hiatus, our curatorial team of four began meeting regularly with Museum staff to plan the gallery in January 2020. Suddenly, a few weeks later, the COVID lockdown barred all of us from the Museum for months and continued to limit access to the objects, archives, and libraries for more than a year. We quickly switched to an online workspace, which worked well for brainstorming, putting together narratives, and working on design, but not for working with and researching objects. The library became available via extended access to digital publications and eventually books by mail. Objects and archives, however, needed other solutions.

We were lucky that Yael Rotem photographed and documented many of the objects in the collection during her curatorial fellowship in 2016–2018. Without her work, it would not have been possible to design this gallery during lockdown. But there were still objects that we needed to see before we could include them in the gallery. Eventually, we came up with a way to do this at one-step removed, with a few pieces at a time. Online study sessions became invaluable. Registrar

Elizabeth Caroscio, Near East Section Keeper Katherine Blanchard, and Mediterranean Section Keeper Lynn Makowsky were allowed to come to the Museum a few days a week. They live-streamed objects on Zoom, took measurements, answered our questions, and generally provided key information about the objects. In the Archives, Alessandro Pezzati and Evan Peugh filmed themselves leafing through archival folders so that we could see what they contained and photographed key documents for us. In this way the team devised an enormous list of over 600 objects, which we eventually winnowed down to the approximately 400 objects displayed in the gallery.

One of the co-curators, Joanna Smith, is grateful that she had studied in person many objects related to the Eastern Mediterranean Gallery in years prior to 2020. She had engaged in research projects with the Museum’s collections of Cypriot objects and taught two History of Art seminars in the Museum during 2016 and 2017: one about ancient textiles, the other about a hypothetical Cyprus gallery for the Museum. There are echoes of these seminars in the Eastern Mediterranean Gallery, especially in the displays about sea trade, textiles, copper, and the sanctuary of Apollo at Kourion on Cyprus. All of us are grateful to the graduate students from AAMW, Religious Studies, NELC, and Art History who, with their specializations in periods and cultures across the gallery’s expanded scope, were key to telling the region's complex story.

Other members of the gallery team faced unusual challenges as well, which they overcame creatively. In Conservation, Jessica Byler and Lynn Grant found ways to document and treat each object despite the closure of their laboratory during the opening months of the pandemic. Similarly, Director of Exhibitions Jessica Bicknell and Director of Preparation Ben Neiditz came up with

workarounds when supply chain problems made procuring casework, especially glass, nearly impossible.

The Eastern Mediterranean Gallery showcases a region that has long been a crossroads of diverse peoples and cultures, as well as a center of innovation. Designing this gallery in 2020–2022 brought home to us the significance of connections and creativity in the present and inspired us to look at the past in new ways. The rapid global spread of COVID-19 reinforced how interconnected our modern world is, while the ongoing shortages of goods and of essential workers and their expertise let us see what happens when those connections break down. These conditions encouraged us to improvise and innovate, to find new ways of telling old stories. The Eastern Mediterranean Gallery is a product then of many of the same processes it studies; it would not have been as rich if we had created it during a different time.

We hope you enjoy this issue of Expedition and that you have a chance to visit the new gallery in the coming months.

In our last issue of Expedition, I looked forward to welcoming you to our newly reimagined Eastern Mediterranean Gallery; now it’s my privilege to introduce this special issue devoted to this immersive new exhibition. You’ll hear from the curators about the historical, social, and cultural contexts for the region’s world-changing innovations (Virginia Herrmann and Adam Smith on the alphabet, page 12), and about the process of building the gallery itself (Joanna S. Smith on displaying a Late Bronze Age ship, page 24). You’ll also learn more about the socio-political context of the excavations which produced many of the artifacts in the gallery—as in the article by Janessa Reeves about the political tensions around the excavation site of Kourion, in Cyprus, before, during, and immediately after World War II. The depth, range, and scholarly detail on display in these pages makes them a fitting companion piece to the gallery itself. I hope you’ll turn to them, before and after you visit, to immerse yourself more fully in a region that has been so central to the development of the human story.

It was a great pleasure to see so many of you during Member Previews and the Opening Weekend. Amid enjoying Middle Eastern food and wine and watching friends and families playing drums and learning traditional dances, I took a moment to walk through the new gallery myself. I was struck by how close I felt to the ancient Eastern Mediterranean; this is a testament to the excellent work our curators and Exhibits team have done to make the gallery immersive and engaging, but also to the many interconnections between this ancient era and our own. An increasingly global civilization, riven by conflict but rich with intercultural exchange: this description could apply just as easily to our world as it does to theirs. Since becoming Williams Director, I’ve stressed that our Museum must demonstrate the relevance of the past to the problems of the present—and I can’t think of a better example than this newly reimagined gallery, which presents the enormous potential for human innovation in a multicultural world.

As 2023 gets underway, I'm looking forward to the months ahead, which will be pivotal for the Museum. We’re embarking on a Strategic Visioning process: a comprehensive consideration of all aspects of our institutional mission. At the heart of this process is a museum-wide interpretive plan: a series of common themes that will guide our exhibitions and programs in the years to come. The first fruit of this process will be the renovation of our Egypt and Nubia Galleries; the construction phase of these galleries will begin before the end of the year, eventually creating a stateof-the art home for one of the most important parts of the Museum’s collection and an educational resource for Penn, our larger community, and audiences from around the world.

Looking back on 2022 and considering what’s to come, I want to take this moment to thank you for the support you give the Museum, and for being a part of our programs and exhibitions. It’s a privilege to be on this journey of discovery together.

Warm regards,

CHRISTOPHER WOODS, PH.D. WILLIAMS DIRECTOR

CHRISTOPHER WOODS, PH.D. WILLIAMS DIRECTOR

LAUREN RISTVET, PH.D., Lead Gallery Curator, is the Robert H. Dyson, Jr. Associate Curator in the Museum’s Near East Section. Dr. Ristvet earned her Ph.D. in Near Eastern archaeology from the University of Cambridge. Her research focuses on the emergence of early states, the intersection of religion and politics, and the rise of ancient empires. She founded and is co-director of the Naxcivan-Archaeological project in Azerbaijan (from 2006 until the present) and was associate director of excavations at Tell Leilan, Syria from 2006 to 2011.

VIRGINIA HERRMANN, PH.D., Gallery Co-Curator, earned her Ph.D. in Near Eastern archaeology from the University of Chicago. Her research on the Ancient Near East focuses on the construction of state and social identities through monuments and the development of ancient cities in periods of state formation and imperialism. She has been the co-director of excavations at Zincirli, Türkiye since 2014.

ERIC HUBBARD, Gallery CoCurator, is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Anthropology whose research interests focus on Bronze Age settlement and water dynamics in the Middle East and South Central Asia; remote sensing applications to archaeology; and cultural heritage politics. Eric is a member of the Penn Museum's Graduate Advisory Council and a Graduate Guide. He earned his M.A. in anthropology from the University of Chicago and a B.A. in archaeology from the College of Wooster in Ohio. He has participated in fieldwork spanning the U.S. Midwest, Israel, Palestine, Cyprus, and Azerbaijan.

JOANNA S. SMITH, PH.D., Gallery Co-Curator, is a Consulting Scholar in the Museum’s Mediterranean Section. Her other museum projects include reinstallations of Cypriot art at The John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art and The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Dr. Smith specializes in interconnections among the arts of the Mediterranean, Near East, and Egypt from the Bronze Age to the Hellensitic period. She codirects the Princeton University archaeological fieldwork project at Polis Chrysochous, Cyprus. Dr. Smith earned her Ph.D. from Bryn Mawr College.

ADAM SMITH, PH.D., is Keeper and Associate Curator in the Museum’s Asia Section, and teaches courses in the School of Arts and Sciences at Penn. He specializes in the study of Chinese excavated manuscripts and inscriptions dating from the beginnings of literacy in China in the 2nd millennium BCE through to the early medieval period.

DAVID MULDER is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of the History of Art. His research focuses on the art of ancient Mesopotamia, with particular interests in Early Dynastic seals and sealings and in terracotta figurines and mold-made plaques of the 3rd through 2nd millennia BCE.

JANESSA REEVES is a Masters student in the Art and Archaeology of the Mediterranean World Program. She has excavated at a Roman site in Romania, a historic site in West Philadelphia, and at Gordion in Turkey. She is a Graduate Guide, currently leading tours of the Eastern Mediterranean Gallery. Her research interests include Roman art and archaeology, social identity, and ancient glassmaking.

In November 2022, a series of events celebrated the unveiling of our reimagined Eastern Mediterranean Gallery—a wonderful opportunity to invite old friends and new visitors to experience the full range of activities that the Museum has to offer.

At the Opening Celebration Weekend on November 19 and 20, visitors enjoyed opportunities to hear from the gallery curators and were invited into the Museum Archives to see up-close documentation of historic excavations throughout the world, to enjoy demonstrations of cutting-edge archaeological techniques in the Center for the Analysis of Archaeological Materials, and to learn about cylinder seals and try their hand at making their own (cork versions). Our galleries were full of rhythm and laughter, as families also enjoyed performances and workshops by Middle Eastern dancers and musical ensembles.

A week of previews began with a Golden Gala, held Friday, November 11, and continued with preview events for Penn students, Museum members, and the press.

Our Golden Gala on November 11, co-chaired by Cason Crane and Fran McGill, and Alice and Herb Sachs, felt particularly festive this year because it was our first in-person gala celebration since 2019. After exploring the gallery’s rich displays and interactives and enjoying Eastern Mediterranean wines and a buffet of grilled meats and vegetables, guests followed a band of musicians and dancers to the Sphinx Gallery, where Williams Director Chris Woods spoke about the curators’ vision and the gallery’s main themes, connections between this ancient region and our own, and where the Eastern Mediterranean fits in the Museum’s ongoing transformation. We were particularly honored that Penn President Liz Magill joined us for the celebration, adding some thoughts of her own about the importance of the region to world history, and about the Museum’s important position within Penn as a whole. After this introduction, guests reconvened in the Museum’s Rotunda for a Mediterranean feast, followed by drinks and dancing in the upper-level Egypt Gallery.

On November 15, Visionaries and Supporting Circle Members were invited for an exclusive first look at the newly reimagined gallery. The event included an introduction from Lead Curator Dr. Lauren Ristvet, giving greater scholarly context about the gallery. This was followed by a tour of the gallery itself, including helpful guidance from graduate students, who were on hand to offer expertise in their fields of interest; the information they provided sparked many conversations about the objects on display. Attendees also enjoyed Mediterranean food and drink, including desserts featuring special flavors from the region, like quince and pistachio. There was also a preview for all Members on November 18; the Museum was open late, to give members an opportunity to take a leisurely look at their own pace, immersing themselves in features like the precise replica of a merchant ship’s cargo hold, modeled after an ancient Phoenician shipwreck.

November 19 and 20 marked the gallery’s Opening Weekend, where the public had their first chance to see the new gallery, to hear more background on the exhibit from scholars and archivists, and to enjoy music and dance performances and workshops. Curators provided talks on some of the gallery’s main themes and important objects, giving more context to this fascinating region, which served as an ancient hub for cross-cultural exchange. Children in attendance had the chance to make crafts based on artifacts in the gallery, like cylinder seals, while the drumming and dance workshops brought families together with movement and music. The two-day event was an enormous success, bringing visitors from across the region and beyond to draw, dance, and explore in our galleries.

On November 16, Penn graduate and undergraduate students were invited to their own gala as part of the Museum’s Academic Engagement program, which seeks to make the Museum a hub for Penn’s larger academic community. After tours by Penn Museum Graduate Guides, they heard brief remarks from Williams Director Chris Woods and Lead Curator Lauren Ristvet about the unique role of the region in the story of human development. Students had a chance to sample spices that were traded throughout the ancient Eastern Mediterranean, to take candid shots in a portable photobooth, and to enjoy drinks and dancing in the Egypt Galleries.

The Penn Museum Eastern Mediterranean Gallery would not have been possible without the outstanding leadership of the following supporters:

The Giorgi Family Foundation

Naming Donor

David Berg Foundation

McLean Contributionship

Elizabeth R. McLean, C78

National Endowment for the Humanities

Gretchen P. Riley, CGS70, and J. Barton Riley, W70, PAR

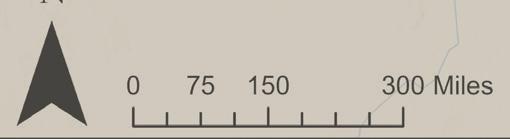

From its Eastern Mediterranean birthplace, the alphabet spread across Asia through trade, religion, and empire. The map detail at left illustrates the locations of important early alphabetic discoveries; map inset by Virginia Herrmann.

The alphabet*—it’s a seemingly simple invention with a deeper history and longer journey than many people realize. The ancestor of most alphabets used today was invented in the Levant (Eastern Mediterranean coastal region), and the Penn Museum’s new Eastern Mediterranean Gallery showcases this invention as one of the region’s most influential legacies for the modern world. In the three stories that follow, we highlight little-known chapters of the alphabet’s amazing history.

In comparison with the earliest writing systems, Mesopotamian cuneiform and Egyptian hieroglyphs, whose signs convey multiple sounds or whole words and are read differently depending on context, an alphabet has far fewer signs and takes less time to learn. Instead of hundreds of signs, students of alphabetic writing only need to learn twenty to thirty letters to spell out the basic sounds of their spoken language.

To those raised in an alphabetic environment, this writing system appears so logical and self-evidently advantageous that it is no surprise that the alphabet has spread far and wide. As continued prominence of

a complex writing system like Chinese hanzi shows, however, widespread literacy does not require an alphabet, and some argue that expressive nuance and creative potential are lost in an alphabet’s simplicity.

Many people know that the Latin alphabet used for English and other languages today developed from the Greek alphabet, and that the Greeks adapted theirs from the Phoenicians. Our first story follows the alphabet’s history back further, to its murky and hotly debated origins in encounters between ancient Egyptian and Levantine people and explores why it took a millennium to come into widespread use. The second story spotlights a remarkable find whose decipherment revealed how both the form and the order of the alphabet we use today could have taken a different path. Finally, the third story takes us off the well-worn road from the Phoenicians to the modern West and follows instead the alphabet’s long eastward journey through Asia, where it played a role in Mongolian and Chinese empires, the Silk Road, and the spread of Buddhism and Christianity.

These remarkable episodes in the long life of the first alphabet show that its present global dominance was far from inevitable but depended on the twists and turns of history.

Herodotus recounts that the Phoenicians taught the alphabet to the Greeks, and, at least on this point, the sometimes fanciful ancient historian has been vindicated by archaeological discoveries. The earliest known

Greek alphabetic inscriptions date to the 700s BCE, when Phoenician ships sailed the Mediterranean. For the alphabet’s earlier history, pure speculation was for centuries the only option, until exploration in the Sinai desert led to a breakthrough. Now, a rash of recent discoveries has fed new ideas about how the alphabet

came to be and why it took so long to take hold.

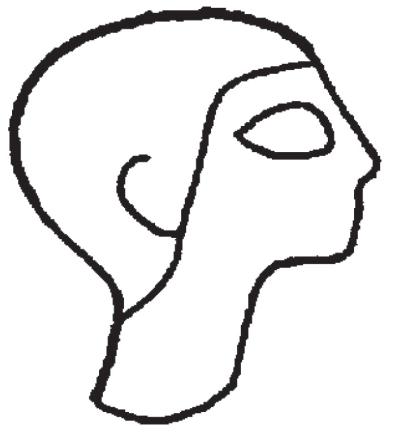

In 1905, pioneering archaeologists Flinders and Hilda Petrie explored the Egyptian turquoise mines and Hathor temple at Serabit el-Khadim in the Sinai Peninsula. Among many Egyptian hieroglyphic and hieratic inscriptions there, they also recorded a few dozen unusual pictographic carvings—their signs were similar to certain hieroglyphs, but the inscriptions could not be read as Egyptian. A few years later, Egyptologist Alan Gardiner realized that these were the pictographic prototypes for the linear Phoenician alphabet! Each letter’s sound-value had been derived from the first consonant of the West Semitic word for the object illustrated by the pictograph (a principle known as acrophony): for example, a human-head hieroglyph (read in Egyptian as tp) became the letter r, because the West Semitic word for “head” was raʾsh (later Hebrew rōʾsh). In fact, most Phoenician letters retained the names of their pictorial inspiration—ʾaleph for the ox-head sign, bēt for the house, etc. Since these turquoise mines dated to the 2nd millennium BCE, the Sinai alphabet was a plausible precursor for the Phoenician alphabet written centuries later. Other evidence showed that many Canaanites native to the southern Levant worked the mines in the Pharaoh’s service, placing West Semitic speakers on the scene for the earliest known alphabetic writing.

The “Proto-Sinaitic” alphabetic inscriptions, as they came to be known, could only be partially understood, but most scholars accepted Gardiner’s theory that Canaanite predecessors of the Phoenicians had invented the alphabet with the inspiration of Egyptian hieroglyphs, possibly as early as 1800 BCE. One specialist argues that the inventors were previously illiterate Canaanite miners seeking to express devotion to the goddess of turquoise in their own tongue. Later excavations in Israel and Palestine turned up several more early-alphabetic inscriptions, dated to 1700–1100 BCE and scratched or written in ink on pottery and stone, that showed the letters’ development toward their later abstract linear forms.

Recently, new discoveries of early-alphabetic inscriptions outside the southern Levant hint at hitherto unsuspected chapters in this now century-old story. First, two inscriptions were found at Wadi el-Hol, Egypt, a rocky valley west of the Nile. The alphabetic inscriptions were carved next to Egyptian inscriptions and graffiti dating to the late Middle Kingdom, ca. 1900–1800 BCE. This discovery supported an early date for the Sinai inscriptions, but also raised the possibility that Egypt itself had been the alphabet’s birthplace, rather than the Egyptian-Levantine border. Nearby Egyptian inscriptions mention the leader of a Levantine mercenary force, and much other evidence points to a large migration from the Levant into Egypt during the Middle Kingdom that culminated in the rule of northern Egypt by “Hyksos” kings of Canaanite ancestry. Perhaps, then, Canaanite expatriates immersed in Egyptian culture were the ones who devised a way to write their own language.

Then came another startling revelation. In an archive from Babylonia dating to ca. 1500 BCE, several cuneiform tablets had short linear alphabetic inscriptions along one edge—the earliest known instance of the practice of writing an alphabetic filing label, or “docket,” on a tablet for easier reference by bilingual scribes. Scholars were amazed that the alphabet had already traveled to Mesopotamia by this early date, and not as an imported novelty, but as a casual expedient in a multilingual setting. This evidence hints that our knowledge of the alphabet’s early use is the tip of an iceberg.

Finally, last year a new study of clay “tags” excavated in a tomb at Umm el-Marra, Syria, cautiously made the case that the inscribed linear symbols are related to the Proto-Sinaitic alphabet. This is a sensational claim, given that the tomb securely dates to ca. 2400–2300 BCE, five to six centuries before the Sinai and Wadi el-Hol inscriptions! Though these inscriptions are short and the letters’ resemblance could be coincidental, if future discoveries uphold this date for the earliest alphabet, it would upend prevailing theories about its invention in the intensive Egyptian-Levantine interactions of the Middle Kingdom and bring it substantially closer to the advent of cuneiform and hieroglyphs between 3400 and 3100 BCE.

In the 13th century BCE a document at Beth Shemesh, Israel, possibly recording a quantity of wine given to several named people, was inked on a fragment of pottery. By this date, the letters had become more abstract and their origins as pictographs harder to detect. Left: Puech, E. 1986. Origine de l’alphabet. Documents en alphabet linéaire et cunéiforme du IIe millénaire. Revue Biblique 93(2): 161–213, fig. 4:5; Right: Grant, E. 1931. Ain Shems Excavations (Palestine), 1928-1929-19301931. Part I. Haverford, PA: College Press, Pl. X.

These new finds do more than extend the early alphabet’s age and geographic range. They also heighten the long-standing mystery of why we have so few alphabetic inscriptions for a millennium (or more) after the script’s invention. The thread of continuity in the alphabetic tradition across centuries appears remarkably flimsy. Once someone made the breakthrough to create a simple phonetic system, why don’t we see an explosion of literacy, littering the soil with grocery lists and postcards to grandma and grandpa? Part of the answer must be the organic material (namely, papyrus) that the alphabet was designed for, whose perishable nature (outside of extreme conditions) has obliterated most documents from this period. But the rarity and terse character of early inscriptions compared to those from the 1st millennium BCE is nonetheless striking. Some propose that alphabetic writing arose and spread

widely within circles of professional scribes, serving as a practical but unofficial script for centuries without breaking through to the vast majority who lacked formal training. Social and political conditions were not yet ripe for widespread literacy. The same scribal community who perpetuated the alphabet were also guardians of the established traditions of cuneiform and hieroglyphs, whose complexity increased the value of their skills. It took the upheaval of the end of the Bronze Age around 1200 BCE, in which Eastern Mediterranean empires fell or retreated and many smaller kingdoms disappeared, to break the dominance of old traditions in the Levant and let a script designed for local languages thrive.

Gardiner, A.H. 1916. The Egyptian Origin of the Semitic Alphabet. Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 3:1–16.

Koller, A. 2018. The Diffusion of the Alphabet in the Second Millennium BCE: On the Movements of Scribal Ideas from Egypt to the Levant, Mesopotamia, and Yemen. Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections 20:1–14.

Sanders, S.L. 2009. The Invention of Hebrew. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

Schwartz, G.M. 2021. Non-Cuneiform Writing at ThirdMillennium Umm El-Marra, Syria: Evidence of an Early Alphabetic Tradition? Pasiphae 15: 255–66.

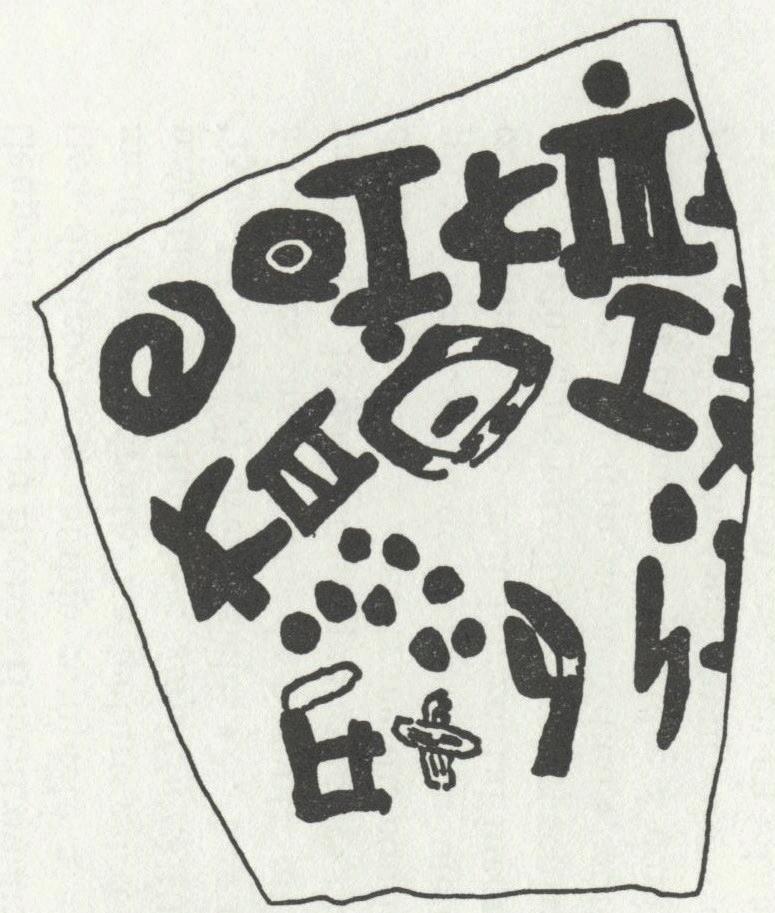

The 1933 excavations at Beth Shemesh in present-day Israel unearthed a most unusual clay tablet that has raised as many questions as it has answered about the early history of the alphabet. Just four years earlier, an alphabetic type of cuneiform script dating to the 13th century BCE had been discovered in Syria, and experts quickly realized that the Beth Shemesh tablet bore the same type of writing.

By the 2nd millennium BCE, cuneiform writing, invented in Mesopotamia, was in widespread use by the royal courts of the Eastern Mediterranean. Cuneiform, like Egyptian hieroglyphs, was a complex script with hundreds of signs that took years to master. In the north Syrian city Ugarit, scribes trained in cuneiform also learned the linear alphabetic script and creatively adapted it to the cuneiform wedges produced by a stylus on clay, thereby inventing the first and only cuneiform alphabet. While they used the regular cuneiform script to write foreign correspondence in the Mesopotamian Akkadian language—the lingua franca of the Near East and Eastern Mediterranean in that period, used for example in the Amarna letters—they wrote epic literature and religious texts in their own Ugaritic alphabet and language (related to later Phoenician and Hebrew). When Ugarit was destroyed ca. 1185 BCE, the cuneiform alphabetic tradition died with it; however, the linear alphabet lived on.

The Beth Shemesh tablet was the first discovery of alphabetic cuneiform so far south, over 500 km from

Ugarit, but many things about it were peculiar. The signs looked backwards, some were non-standard in form, and they ran counter-clockwise around the edge of the tablet instead of making neat lines. Scholars even wondered if the tablet—elongated and flat on one side, instead of the usual rectangular pillow shape—had been formed in the mold for a metal axe. It is no wonder, then, that the first

attempts to decipher the inscription came up with rather odd, and ultimately incorrect results—a prayer to cure stammering, written in mirror-writing for magical effect, or an incantation addressed to the birth-goddess.

Fifty years passed before Russian scholar A.G. Lundin recognized the Beth Shemesh text for what it was: an abecedary (a text giving the alphabet in

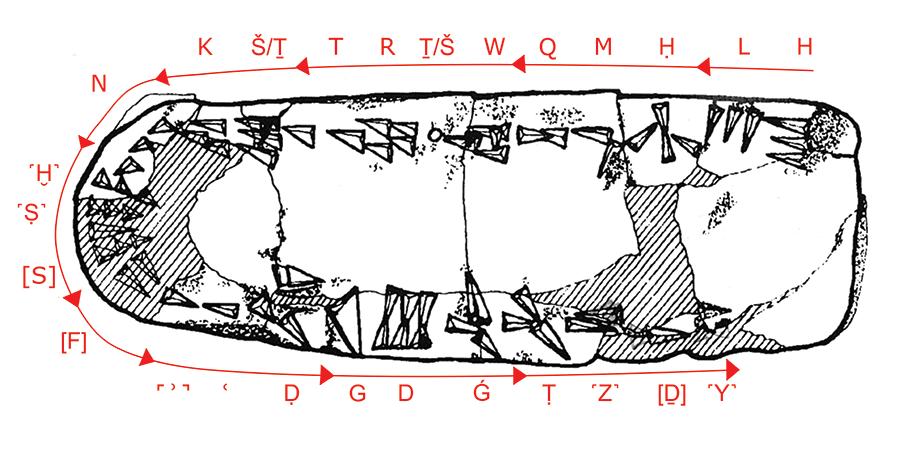

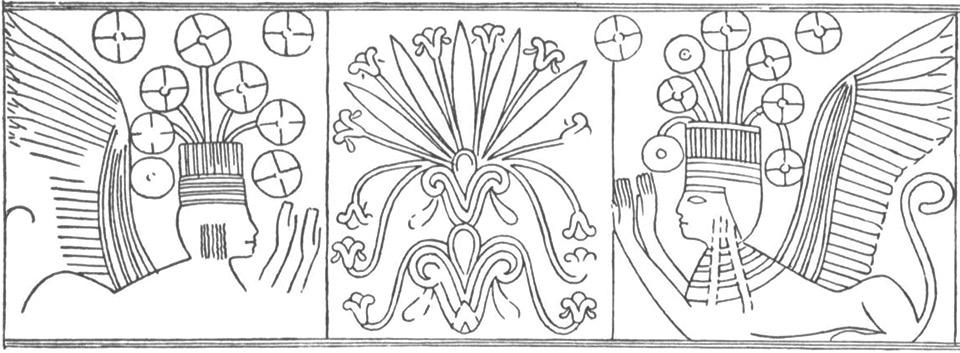

Above: The signs of alphabetic cuneiform are here written right-to-left instead of left-to-right and wrap around the tablet from the top right to bottom right. The letters follow the halaḥam order instead of the more familiar ’abgad order and show some variation in their shapes from the standard cuneiform alphabet. Drawing after Puech 1991: 47, annotated by the author. Left: Abecedaries (lists of the letters in order) of the Ugaritic and Phoenician alphabets, which used the ’abgad order and ultimately became a-b-c-d in the Latin alphabet, and the Old South Arabian and Beth Shemesh tablet alphabets, which used the halaḥam order still found today in Ethiopian languages. Letters with extra signs symbolize consonants not found in English. Letters in brackets would fall in the damaged part of the Beth Shemesh tablet.

order for teaching or study), with a twist. Instead of the more familiar ʾ(a)-b-g-d…(ʾabgad) letter order used by the Ugaritic and later Phoenician and Hebrew alphabets—from which our a-b-c-d… derives—the Beth Shemesh letters had the order h-l-ḥ-m…. This was not a random sequence, but the standard letter order used by abecedaries first attested a millennium later in South Arabia. The Old South Arabian script developed as a distinct southern branch of the alphabet and spread to Eastern Africa, where Ethiopian scripts still use a variant of the h-l-ḥ-m… order today.

Lundin’s brilliant realization at once sparked three new insights:

1. the South Arabian alphabetic tradition was at least as old as the Ugaritic/Phoenician one, not derivative of it, as previously believed;

2. it had been used not only in Arabia, but also alongside the ʾabgad tradition in the Levant, where it may even have been invented; and

3. its early use there was significant enough to warrant its adaptation to cuneiform for writing on clay tablets.

Subsequent discoveries of another halaḥam cuneiform abecedary (halaḥamary?) at Ugarit itself and possibly a third such abecedary found in Egypt and dating even earlier confirmed Lundin’s deductions

and showed that the Beth Shemesh abecedary was not a one-off experiment but part of a robust alternative alphabetic tradition.

Major questions remain about this fork in the early history of the alphabet, which, if it had gone a different way, might have resulted in millions of preschool children today singing a very different alphabet song. Where and why did the split between these two competing alphabetic orders occur? Where and how did the alternative halaḥam order survive to resurface in South Arabia centuries later? Was it associated already in the 2nd millennium BCE with particular Semitic languages—possibly South Semitic languages like those of Yemen and Ethiopia? And why would someone form a tablet for alphabet study in an axe mold? At the moment, our evidence is silent on these points. But any day, another new discovery like the Beth

Abecedary: A listing of the letters of the alphabet in a traditional sequence, usually used for teaching and learning.

Acrophony: The pictorial representation and/or naming of a letter by a word whose initial sound that letter represents.

Alphabet: A set of letters, or written signs, that each represent one of the basic phonemes (distinct units of sound) of a language.

Consonantal writing: A writing system that does not represent vowels, but only the consonants and “semi-consonants” (like w and y) of a language. Both Egyptian hieroglyphs and the early Semitic alphabets use consonantal writing.

Cuneiform: A writing system that used a reed stylus to impress wedge-shaped signs into clay. Cuneiform was invented in Mesopotamia in the 4th millennium BCE and used to write a variety of languages until the 1st century CE. Although a cuneiform alphabet was

Shemesh tablet could revolutionize our understanding of the alphabet’s complex history.

Pardee, D. 2006. The Ugaritic Alphabetic Cuneiform Writing System in the Context of Other Alphabetic Systems. In Studies in Semitic and Afroasiatic Linguistics Presented to Gene B. Gragg, C. L. Miller, ed. Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization 60. Chicago: Oriental Institute, 181–200.

Puech, E. 1991. La tablette cunéiforme de Bet Shemesh: premier témoin de la séquence des lettres du sudsémitique. In Phoinikeia Grammata. Lire et écrire en Méditerannée. Actes du Colloque de Liège, 15-18 novembre 1989, eds. C. Baurain, C. Bonnet, and V. Krings. Liège, 33-47.

developed at Ugarit, most cuneiform writing used sets of hundreds of signs that could be read either phonetically, as syllables, or logographically, as whole words. Each sign had multiple possible readings depending on its context.

Hieroglyphs: A pictographic writing system such as that used by the ancient Egyptians beginning in the 4th millennium BCE and continuing until the 5th century CE. In Egyptian hieroglyphs, the symbols could be read either phonetically, as one or more consonants, or logographically, as whole words. Each sign had multiple possible readings depending on its context. Egyptian hieroglyphs were a consonantal writing system.

Pictograph: A symbol in a writing system that graphically represents a physical object. Sometimes also called a pictogram.

Proto-Sinaitic and Proto-Canaanite: The earliest known alphabet, a consonantal writing system used to write Semitic languages in the Levant and Egypt in the 2nd millennium BCE. The form found in the Sinai Peninsula is called Proto-Sinaitic, while inscriptions found in the Levant are called Proto-Canaanite.

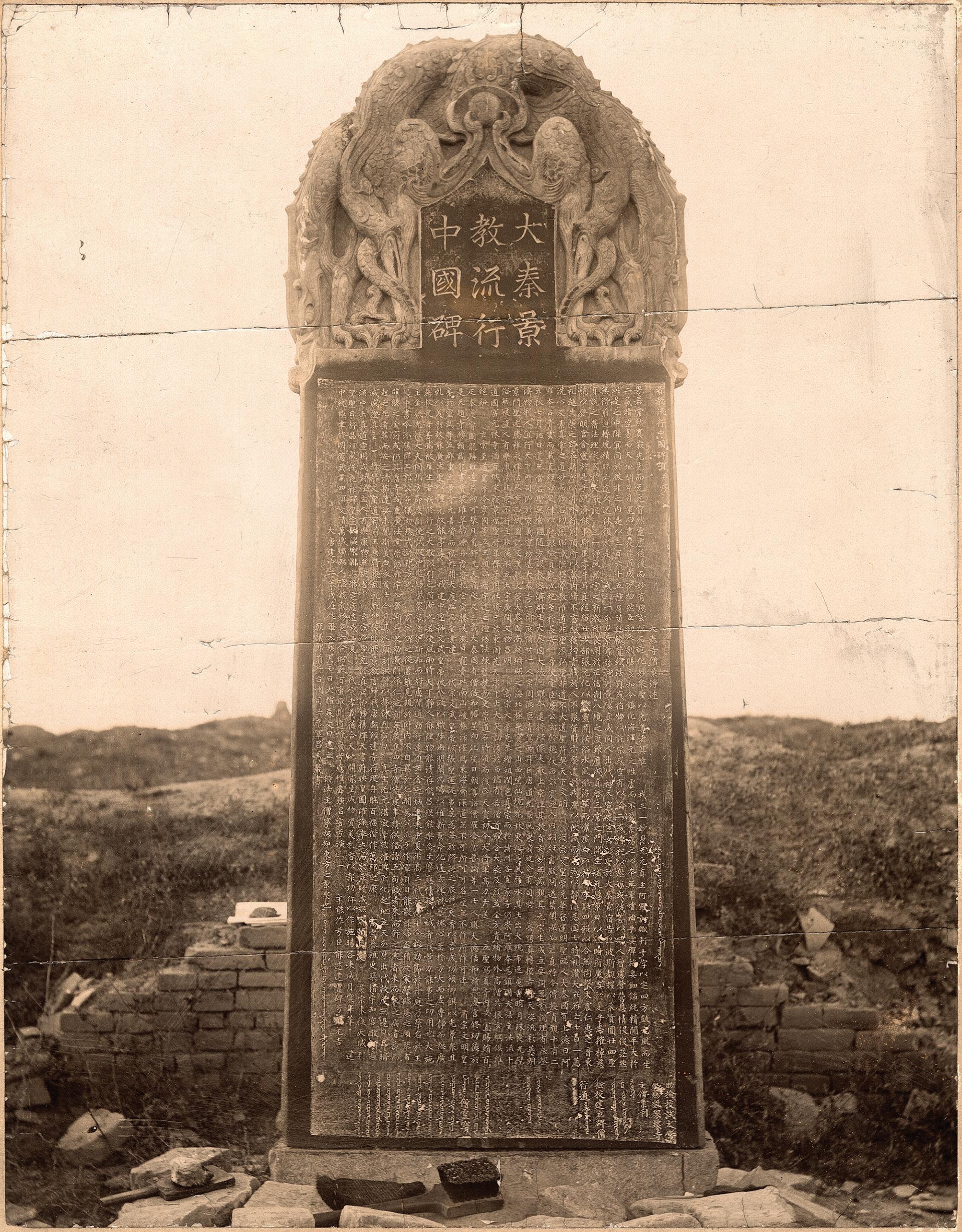

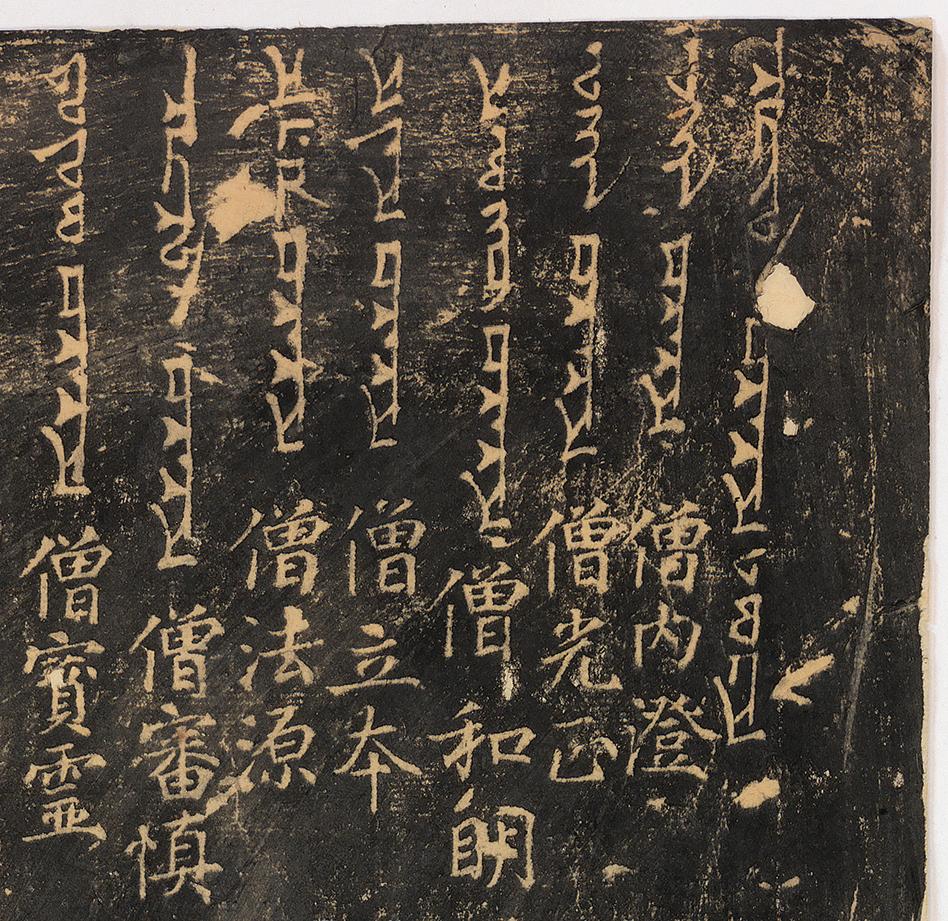

Early photograph (before 1896) of an ink-squeeze rubbing being taken of the 781 CE Syriac Christian stone inscription, Xi’an, China. The monument was thrown down and lost during a persecution of foreign religions in the 9th century, and then rediscovered in the 17th century; 19122.

Around the same time that the Greeks were adapting Phoenician letters to write their own language, speakers of Aramaic, a language closely related to Hebrew, did the same. The Greeks initiated the spread of the alphabet westwards around the Mediterranean and ultimately all over Europe. The use of Aramaic by the Greeks’ rivals, the Achaemenid Persian Empire, established its use throughout the Near East and gave rise to a dazzling cascade of further borrowings and adaptations that over the course of two thousand years reached regions as far away from the Mediterranean as Manchuria and Beijing, and languages as diverse as Mongolian, Sogdian, Uyghur, and Gāndhārī.

The Achaemenid Empire and the reach of the Aramaic alphabet extended east as far as the Indus and Central Asia. After the fall of the Achaemenids, the conquests of Alexander in the 4th century BCE brought the Greek language and its alphabet to those same regions. The two cousin alphabets, Greek and Aramaic, appear together in a famous bilingual rock inscription near Kandahar, Afghanistan, carved for the Indian king Ashoka in 260 BCE, half a century after Alexander. Ashoka carved monumental inscriptions on exposed rock surfaces and stone pillars all over the

Indian subcontinent, in scripts tailored to regional linguistic variation. Alongside Greek and Aramaic, the most northerly inscriptions are in an Indian language, written in the Kharoṣṭhī alphabet. The letter forms and sounds of Kharoṣṭhī are easily matched to those of Aramaic from which this Central Asian variant derived. Ashoka’s inscriptions throughout the rest of India are written in yet another alphabet, Brāhmī. The first appearance of the Brāhmī alphabet, in inscriptions by a king who also used Aramaic, suggests that it too may have been inspired by an Eastern Mediterranean alphabet. The letter forms are much harder to match convincingly, and however, for that reason the origins of Brāhmī and connections to Aramaic are unresolved. Whatever its origins, Brāhmī developed into the alphabets for countless languages of South and Southeast Asia and Tibet.

There were still Greek kings in Central Asia, in what is now Afghanistan and Pakistan, with Greek names and using the Greek and Kharoṣṭhī alphabets, for more than two centuries after Alexander. The name of King Menander I (2nd century BCE) appears on the coin seen in the center of this page. Like Ashoka’s Kandahar inscription, the legend on the coin is bilingual, with Greek on one side and the Aramaic-derived Kharoṣṭhī alphabet on the other.

Buddhist tradition recognizes King Ashoka as the great early patron of Buddhism, who distributed the Buddha’s relics (bodily remains) in commemorative monuments across his Indian empire. King Menander also appears in Socratic dialog with the Buddhist sage Nāgasena in an early text, “The Questions of Milinda,” the title of which uses an Indian version of his name. The Kharoṣṭhī alphabet used by both kings was also the medium for Buddhist literature. The earliest Buddhist manuscripts that survive today are written using the Kharoṣṭhī alphabet in Gāndhārī, another Indian language.

The creation of the Chinese script around 1300 BCE was completely independent of the alphabet and other

Near Eastern writing systems. For about two thousand years, Chinese was the only script that most people in East Asia would ever encounter. During the early medieval period, foreign communities that settled in the Chinese-speaking regions that are now the People’s Republic of China often brought their languages and their Aramaic-derived alphabets with them.

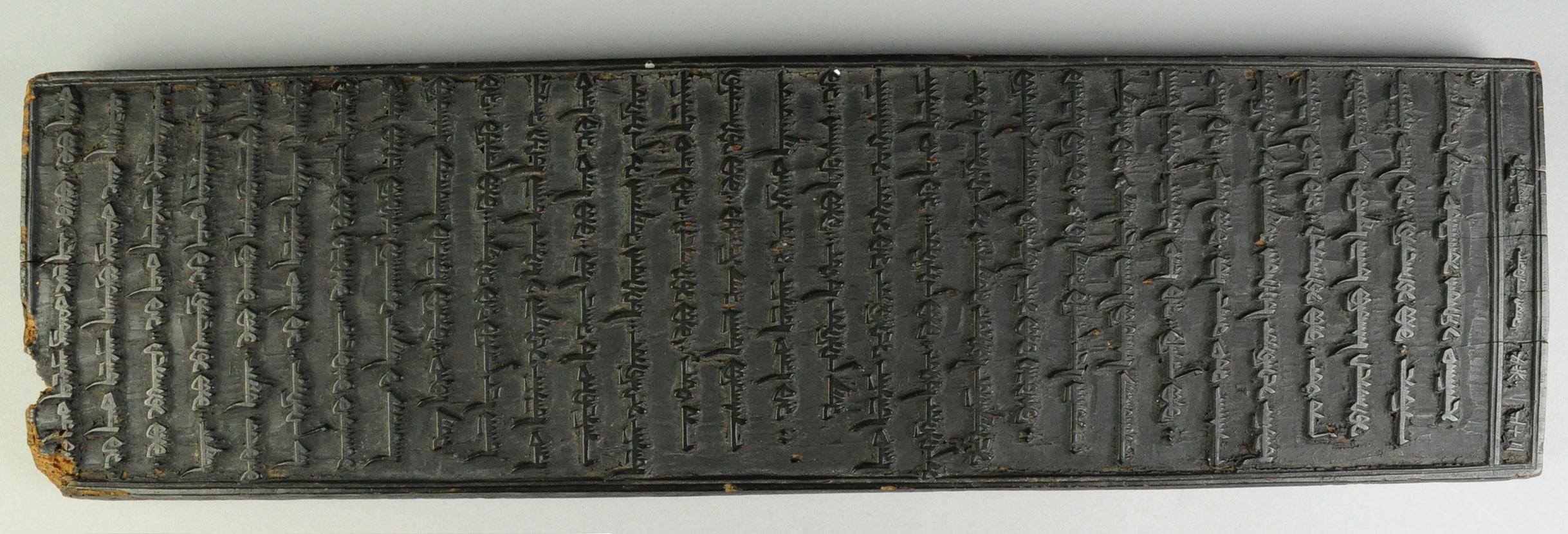

The Sogdians dominated Silk Road trade between the medieval Chinese states and Sogdian homelands in Central Asia. Sogdians living in Chinese cities in the 6th century CE were commemorated upon their deaths with epitaphs inscribed in their own Iranian language using the alphabet. Syriac Christians similarly brought their language and script with them when they established a community in the Tang dynasty’s capital city, Chang’an. Their most famous monument is a stone inscription erected in 781 CE. Most of the inscription is in Chinese, commemorating the arrival of Syriac Christians during the reign of the Taizong emperor a century earlier and listing their core religious beliefs. A shorter text appears in the Syriac alphabet together with a list of priests’ names.

The Turkic-speaking Uyghurs adopted and modified the alphabet of the Sogdians,

and it was Uyghur scribes that brought literacy to the Mongol empire of Genghis Khan and his successors. Unlike earlier Aramaic-derived scripts, the UyghurMongolian script runs top-to-bottom in vertical columns, like the traditional Chinese script. It is only ever written cursively, with ligatures (connecting lines) joining letters and flourishes at the start and end of words, which set it apart visually from the earlier alphabets from which it evolved. The Mongolian alphabet is still an important part of cultural identity for Mongolian speakers in the People’s Republic of China and Mongolia today.

The Manchu Qing Dynasty conquered and ruled China from the palace halls of the Forbidden City in Beijing from the 17th century until 1911. Like the Mongols, they were an ethnolinguistically distinct ruling class in the Chinese-speaking world. The use of the Mongolian alphabet to write their Manchu language (unrelated to Mongolian and Chinese) was the last major step in the spread of the Aramaicderived alphabets in East Asia. Most subjects of the Qing empire never spoke or wrote any Manchu, but

they would have seen it in symbolic or ceremonial uses, rather like the use of Latin in the United States on coins, mottoes, and diplomas. The Qing government sometimes rewarded loyal service with documents in Chinese and Manchu bestowing elaborate honorific titles on the recipient’s deceased parents. Qing coins also had legends in Chinese and Manchu, representing the only Manchu writing that most Chinese people would ever encounter. Manchu writing would have evoked for them the distinctive identity of the ruling dynasty, but its remote origins among the alphabets of the Eastern Mediterranean millennia ago would have been as illegible as the script itself was for most readers.

Daniels, P.T. and W. Bright (eds.). 1996. The World’s Writing Systems. New York, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Keevak, M. 2008. The Story of a Stele: China’s Nestorian Monument and Its Reception in the West, 1625-1916. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

Salomon, R. 1998. Indian Epigraphy: A Guide to the Study of Inscriptions in Sanskrit, Prakrit, and the other Indo-Aryan Languages. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

sea-going trade expanded in the Mediterranean in the Late Bronze Age (ca. 1600–1100 BCE). The catastrophes that led to the sinking of ships— including foul weather, perilous rock formations, and pirates—created deposits that preserve glimpses into the movement of people and cargoes. The Eastern Mediterranean Gallery includes a display of a merchant ship that frames objects that could have been carried on and used by those who sailed these ships.

A shipwreck preserves objects that sank at one moment in time. By contrast, the objects displayed in our ship at the Penn Museum span the Late Bronze Age. Objects from shipwrecks—the ships, the personal effects of sailors, and the ship cargoes—were in transit over long distances at the time of their sinking. Objects on land could also have traveled over long distances, but they are found in more localized use contexts, such as houses, workshops, administrative buildings, storage rooms, temples, and tombs. Creating the ship display for our exhibition brought out similarities and differences among the forms, functions, and values of objects found underwater and similar objects that come from sites on land in Jordan, Israel, Cyprus, Egypt, and Greece in collections of the Penn Museum.

Merchant sailing ships in the Late Bronze Age traversed the Mediterranean, connecting Egypt and the coast of Western Asia with Cyprus, Greece, and places further west. Merchant vessels could carry luxury gifts sent from one ruler to another or could carry goods for other forms of exchange.

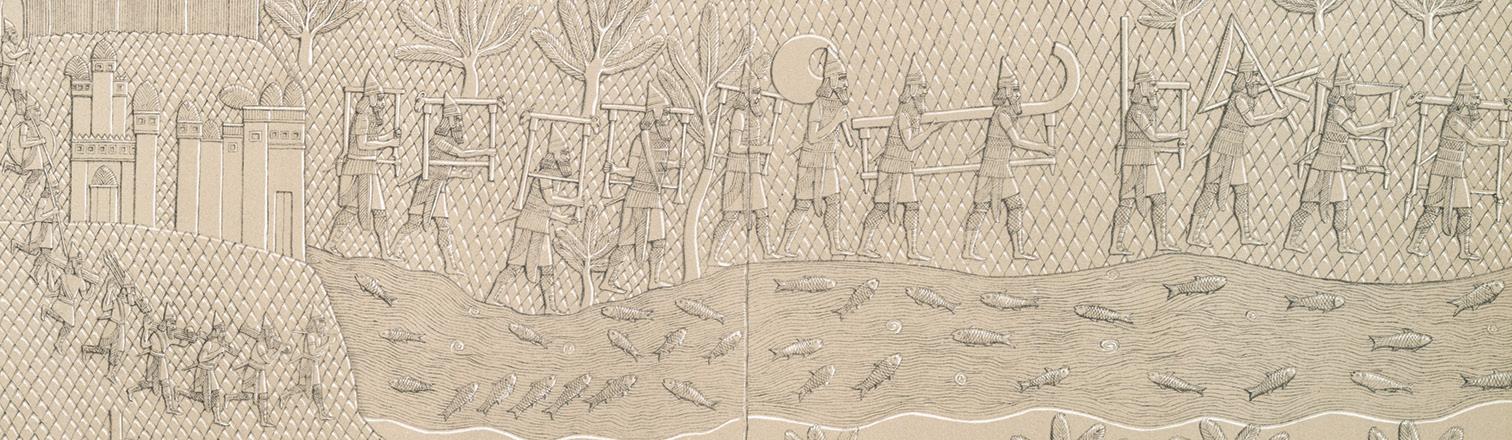

The structure of the ship displayed in the Penn Museum draws especially on evidence from Syrian merchant sailing ships portrayed in the New Kingdom tomb of Kenamūn at Thebes, Egypt, and a 15-meter-long (50 ft) ship that sank ca. 1335–1305 BCE off the southern coast of Turkey near Uluburun. Smaller ships thought to be of similar design

sank ca. 1200 BCE off the coast of Point Iria in Greece and near Cape Gelidonya on the southern coast of Turkey. Our ship display gives visitors a sense of the size and scale of a merchant ship, but does not recreate any particular ship, a specific cargo, or a crew’s origin or final destination. A full-sized ship would not fit in the gallery, hence the ship is a cut-away view of one end of a hull, unspecified as to whether it is the bow or the stern. An unfurled sail hangs above. The emphasis is on the cargo hold, thus details of the deck, railings, and rigging have been omitted.

George F. Bass was a graduate student at the University of Pennsylvania when he directed the pioneering excavation of the Cape Gelidonya ship in 1960, the first to employ techniques of land excavation at an underwater site and the first excavated by archaeologists also trained as divers. Underwater excavations of merchant ships have documented ship parts, cargoes of finished products and raw and/or recyclable materials, and personal belongings of the crew. The Penn Museum’s collections from sites in the Eastern Mediterranean region do not include objects found during the excavation of a ship or parts of a ship vessel. Objects in our display that compare with the personal belongings of Late Bronze Age merchant ship sailors come mainly from two inland sites in Israel: Beth Shean, the site that

is at the core of the Eastern Mediterranean Gallery (see Hubbard, page 74), and Beth Shemesh. Each of these cities had a population of Canaanites who lived under Egyptian rule in the Late Bronze Age. Objects in our ship that compare with the cargoes of Late Bronze Age ships are from many sites that formed parts of the Eastern Mediterranean long-distance trade network. In addition to Beth Shean and Beth Shemesh, the objects are from the coastal towns of Gournia on Crete, Greece, and Kourion-Bamboula, Cyprus. There is also one object each from Tell el-Amarna in Egypt and the Baq’ah Valley in Jordan.

People from many regions sailed on merchant ships. A drawing in the gallery includes two men from a hypothetical crew. Weight sets suggest that there were three or four merchants on board the Uluburun ship who served as crew and captain.

Merchants carried weights for measuring out quantities of precious metals. Next to the ship display is a case about merchants that includes hematite weights. One weight (29-107-627) at 27.72 g is the equivalent of three shekels, a widely used standard of weight between 9.3 and 9.4 g.

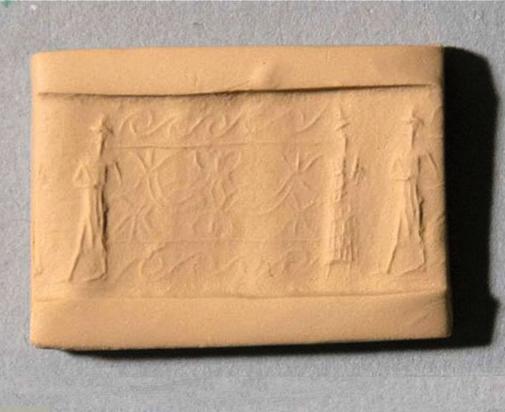

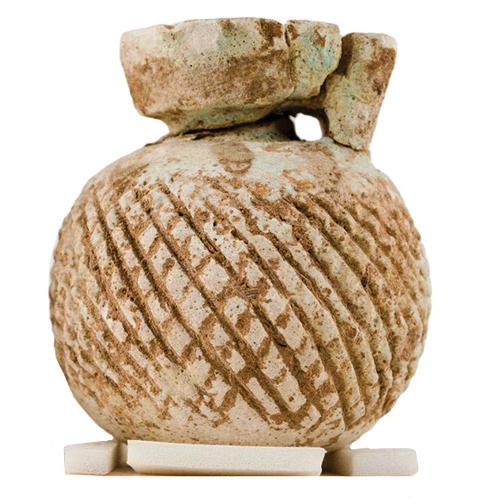

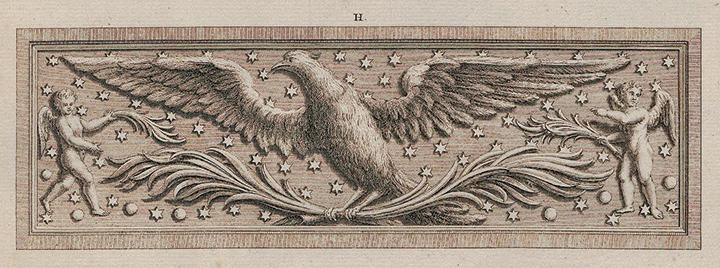

Merchants also carried seals, small objects worn as amulets and used to make impressions in clay as a kind of signature. A north Syrian cylinder seal, made of faience ca. 1600–1400 BCE, in the ship display has a carved design that includes a pair of lions and two men worshipping a sacred tree, emphasizing divine protection for the wearer.

Seals could be strung like beads. Beads similar to a round faience bead in our display (49-12-279) have been found all around the Eastern Mediterranean and were carried also as cargo on ships.

Sailors also wore amulets with symbols of their gods, similar to two gold pendants in our ship. One with an incised eight-ray star disk represents the star of Ishtar (Venus) (29-105-93). A crescent-shaped pendant may represent the moon god. Venus and the moon would have been important to sailors in navigation.

Crews would have used ceramic vessels for meals and terracotta oil lamps for light on board ship. Traces of burning are still visible on the pinched nozzle of a bowlshaped lamp in the ship display.

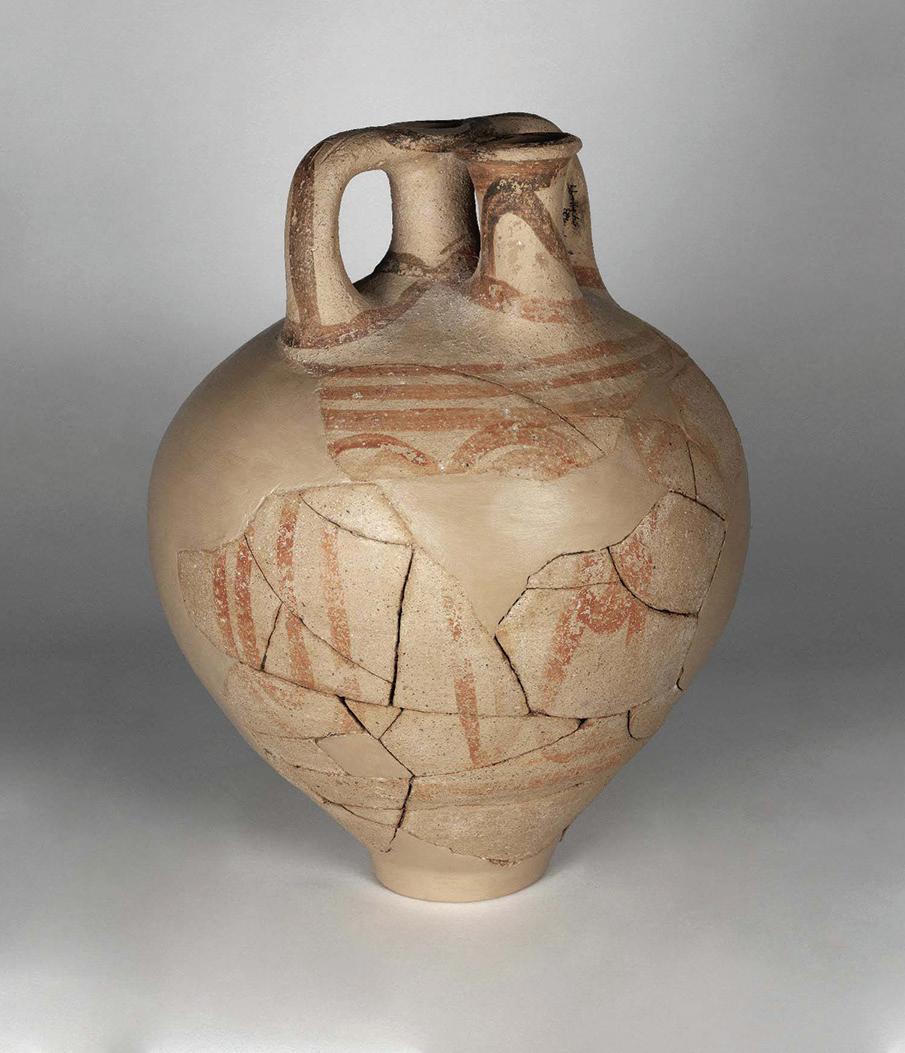

Much of a ship’s cargo, like fruit, wine, oil, and likely also textiles was shipped in containers. As on land, rarely are vessels found with their contents intact. A typical Late Bronze Age olive oil shipping container has two stirrup-shaped handles. Stirrup jars originated in Mycenaean Greece. Potters elsewhere copied the design, creating vessels like the one from Beth Shean in the ship display (32-15-146).

Stirrup jars were shipped all around the Eastern Mediterranean, often being reused, sometimes for a different commodity. A squat stirrup jar in the ship display was made in Greece, but was found in the Baq’ah Valley, Jordan (81-14-641). A larger, coarser example with an octopus design was made on Crete, but it was found at Kourion-Bamboula, Cyprus. On one handle is an undeciphered Cypro-Minoan mark, perhaps added by a Cypriot merchant.

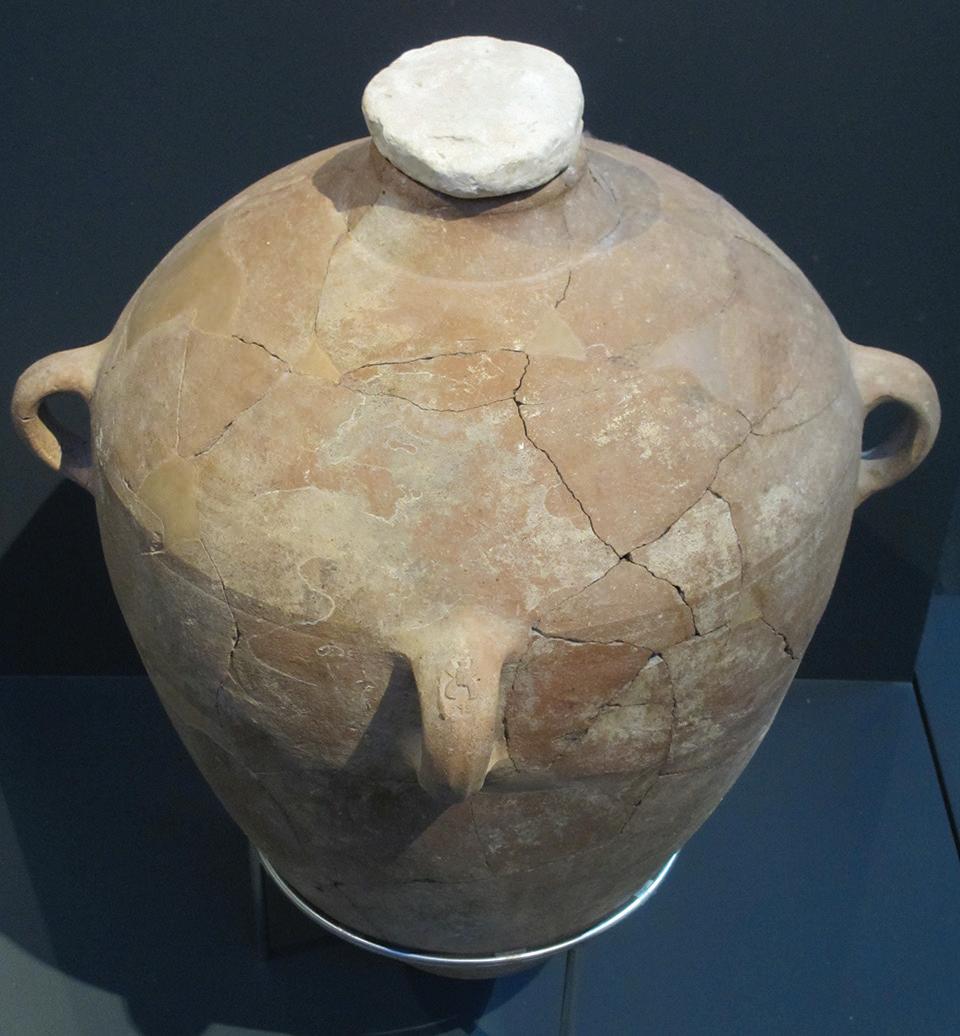

Enormous Cypriot storage vessels called pithoi served as shipping containers. They compare in shape and size with large ones from land sites, where pithoi stood on floors or were placed in pits cut into the floors. Due to their size, none of the many whole pithoi found at Kourion-Bamboula were exported to Philadelphia.

Goods were also shipped in Canaanite jars. The only complete Canaanite jar in the Penn collections (29-103168), reconstructed from many fragments, was not stable enough to be put on permanent display. A crew member in a drawing that accompanies the ship display carries one of these vessels. Its pointed base could be stuck into soft ground to stabilize it on land and these vessels were stacked inside cargo holds, often with the pointed base of one resting on the flat shoulder of another vessel below. For an idea of the size and shape of these shipping containers, the gallery instead features a transport amphora (54-41-41) from ca. 600–500 BCE in a display about Phoenicians placed next to the ship and a pithos from Roman-period Kourion (see Smith, page 49).

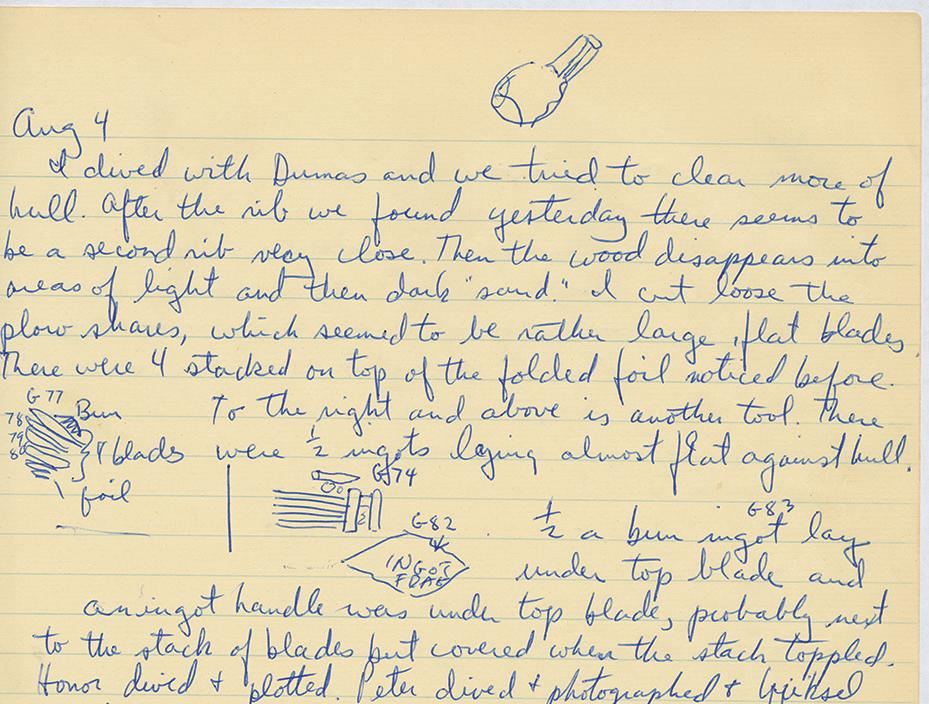

A drawing in the gallery shows a deck that covers a ship’s cargo hold, but the deck likely would not have covered the cargo hold entirely. Cargo was stacked tightly. George Bass described the stacking of raw copper ingots from Cyprus

and scrap metal in the form of broken bronze plowshares in his Cape Gelidonya field notebook. In his publication he cited an example from Beth Shemesh (61-14-2570) as a close parallel for some plowshares from his excavations.

Bronze vessels like one from Kourion-Bamboula in our display were carried as finished products or scrap metal, but their thin bodies do not survive well underwater, often leaving only the thickened rims behind.

Raw metals like copper were shipped in much larger quantities in standardized shapes of similar weight called ingots. Finding a whole ingot on land is rare in the Eastern Mediterranean. Copper “oxhide”-shaped ingots with four protruding handle-like corners are porous rather than solid, making it possible to divide them with a blow of a hammer. The ship display includes one of four fragments of ingots found at Gournia, Crete (MS4563B). Scientific analysis showed that the ingot fragments from Gournia were made of copper mined in Cyprus.

The ship display also includes a fragment of a blue glass ingot (E845.24). It retains part of the flat surface of the ingot made in a disc-shaped, slightly conical mold.

The Eastern Mediterranean Gallery has many finely crafted luxury objects that might have been carried on merchant ships. For conservation reasons, the small ivory cosmetic box lid in the ship display (4912-245) will alternate with another, similar example to preserve their delicate material. Removing one to return to storage and replacing it with the other also symbolically allows the ship in the gallery to unload and load cargo periodically. Their circular shapes measuring 5.6 and 5.8 cm in diameter show how they were made from slices of hippopotamus tusks. Ivory was also shipped in the form of tusks, but on land it is rare to find a whole one.

Cypriot table wares come from many sites around the Eastern Mediterranean. They could be carried as ship ballast to add weight after other more intrinsically valuable cargoes were unloaded. On land, as at Kourion-Bamboula, Cyprus, Cypriot white-slipped and hard-fired bowls (49-12-248) and jugs (49-12-316) with ring-shaped bases served as colorful and often shiny table wares.

Outside Cyprus, similar vessels might have been valued as exotica or antiques, as suggested by two vessels in the ship display. A hard-fired Cypriot jug with a ring-shaped base found at Beth Shemesh and a Cypriot jug with a shaved surface and pointed base found at Beth Shean (29-102-764) were likely manufactured a century or more before their final use.

People used the objects that we have selected for the ship display in their daily lives—at home, at work, and in worship—before losing, breaking, or deliberately burying them.

Residents of Kourion-Bamboula would have consumed the contents of the Cretan stirrup jar. They also placed vessels—the white-slipped bowl, bowl and jug with ringshaped bases, and the bronze bowl—in tombs as parts of funerary dining equipment. Family members there also offered the ivory cosmetic box lids and the faience bead as gifts for the dead.

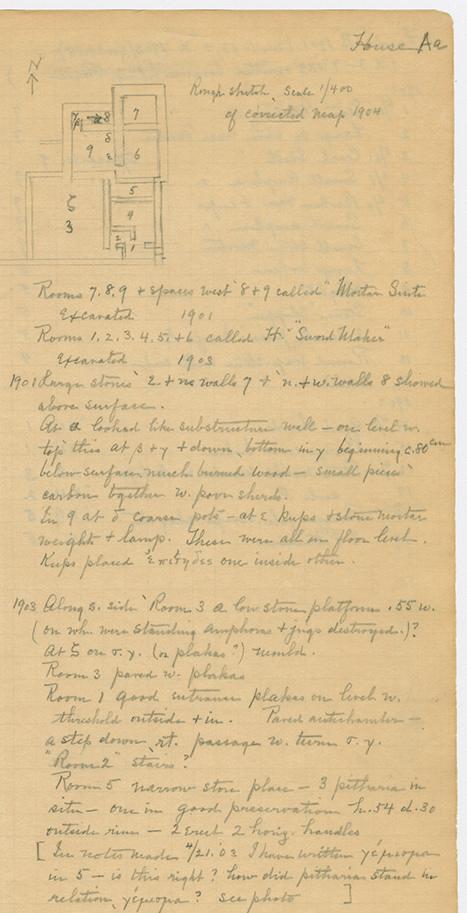

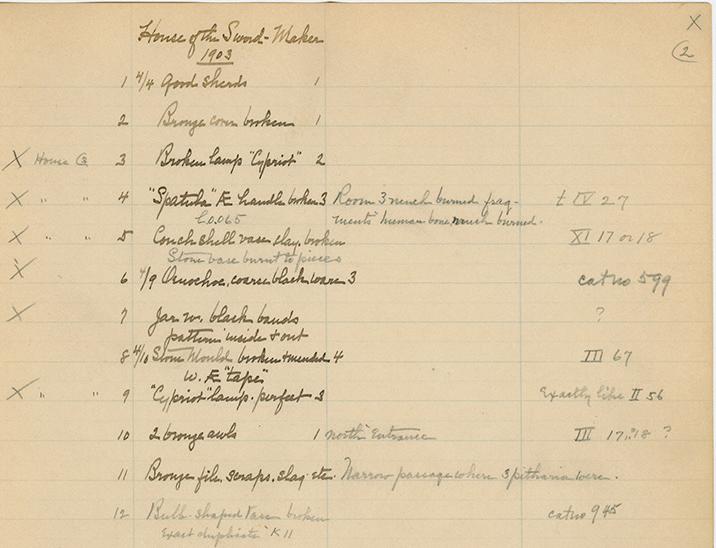

A glass-worker likely discarded the glass ingot fragment in a workshop at Tell el-Amarna. The Gournia excavation notes make no mention of copper ingots. Possibly they were thought to be slag, the waste material from metalworking. The only mention of slag appears in notes for “House of the Sword Maker”, termed House Aa and published as House Ea. There slag was found in a storage space among pithos vessels, which compares with the find locations of several other copper ingots and

their fragments on Crete. Recent excavations at Gournia have discovered evidence for bronze-working in the same part of the ancient town. Most likely a bronzesmith stored these ingot chunks, which could be melted down and made into tools, weapons, or other objects.

People at Beth Shean lit their house with the Canaanite lamp. Mercantile activity required the use of the hematite weight—among others—in a forerunner of the commander’s house. Also from Beth Shean are the small Cypriot jug with a pointed base, the Syrian faience cylinder seal, and the pendant amulet with the star of Ishtar. They were found in a temple (see Hubbard, page 58), placed there as dedications or used as temple equipment.

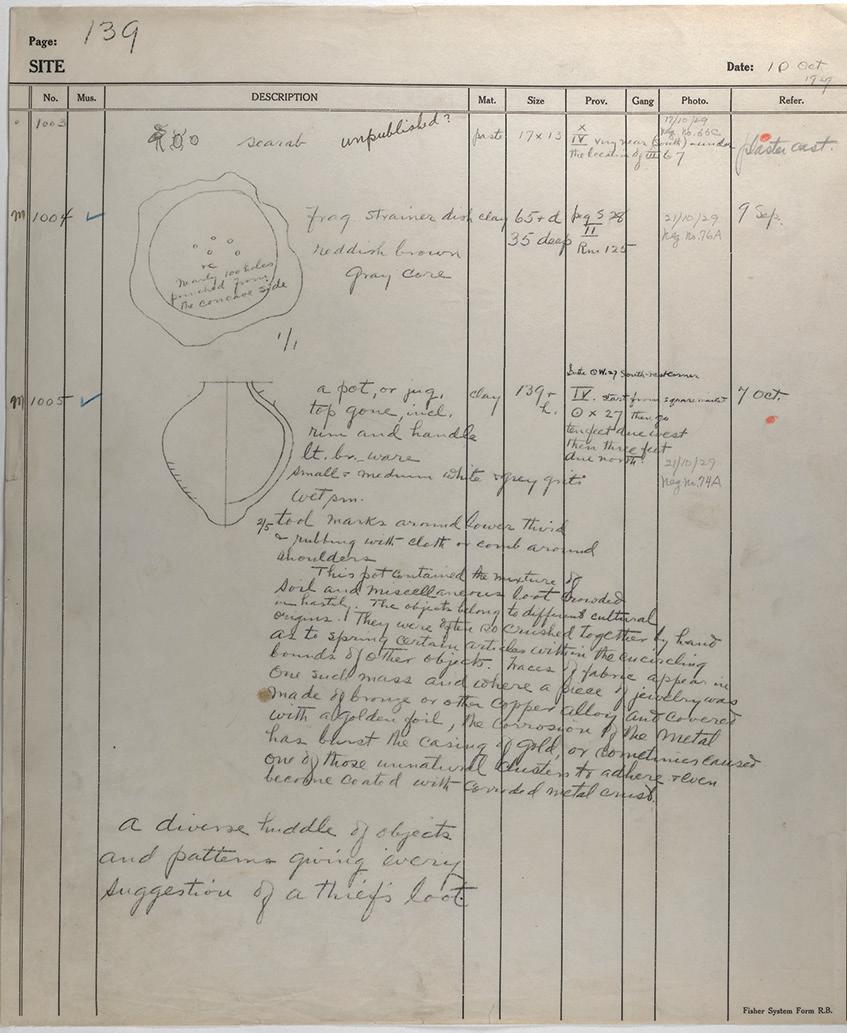

Someone at Beth Shemesh buried the crescent-shaped amulet as part of a hoard of gold and precious stones buried in a house. Elihu Grant, director of the Haverford College excavations at Beth Shemesh, described this find as a “thief’s loot.” We now understand this hoard— contained in a ceramic jug—to be one of many similar burials of precious materials from the end of the Late Bronze Age. The crescent likely was no longer valued as an amulet, but as one of many bits of precious metal and stone stored in the pot as a kind of currency. The owner likely had every intention of retrieving it rather than leaving it buried for millennia.

The objects that fill the Penn Museum ship provide views into the dynamics of merchant shipping and the consumers of the objects carried on board ships. The condition of these objects at the time of discovery and their find contexts reveal overlaps and divergences in the function and value of similar objects during transit and these objects at their final destinations.

The author would like to thank Cemal Pulak for sharing his thoughts about reconstructions of the Uluburun ship and Moritz Jansen for comments about studies of the copper ingots found at Gournia.

Bass, G.F. 1967. Cape Gelidonya: A Bronze Age Shipwreck. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, new series vol. 57, part 8. Philadelphia: The American Philosophical Society.

Benson, J.L. 1972. Bamboula at Kourion: The Necropolis and the Finds, Excavated by J. F. Daniel. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Fotou, V. 1993. New Light on Gournia: Unknown Documents of the Excavation at Gournia and Other Sites on the Isthmus of Ierapetra by Harriet Ann Boyd. Aegeaum 9. Liège: Université de Liège.

Grant, E. 1932. Ain Shems Excavations (Palestine) 19281929-1930-1931, Part II. Biblical and Kindred Studies

4. Haverford: Haverford College.

Jackson, C.M., P.T. Nicholson, and W. Gneisinger. 1998. Glassmaking at Tell el-Amarna: An Integrated Approach. Journal of Glass Studies 40:11–23.

James, F.W., and P.E. McGovern. 1993. The Late Bronze Egyptian Garrison at Beth Shan: A Study of Levels

VII and VIII. University Museum Monograph 85. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology.

McGovern, P.E. 1986. The Late Bronze and Early Iron Ages of Central Transjordan: The Baq’ah Valley Project, 1977–1981. University Museum Monograph 65. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology.

Palaima, T.G., P.P. Betancourt, and G.H. Myer. 1984. “An Inscribed Stirrup Jar of Cretan Origin from Bamboula, Cyprus.” Kadmos 23.1: 65–74.

Pulak, C. 2008. The Uluburun Shipwreck and Late Bronze Age Trade. In Beyond Babylon: Art, Trade, and Diplomacy in the Second Millennium B.C., edited by J. Aruz, K. Benzel, and J.M. Evans, pp. 288–385. New York. The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Wachsmann, S. 1998. Seagoing Ships and Seamanship in the Late Bronze Age Levant. College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press.

Watrous, L.V. et al. 2015. “Excavations at Gournia, 2010–2012.” Hesperia: The Journal of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens 84.3: (2015) 397–465.

Wheeler, T.S., R. Maddin, and J.D. Muhly. 1975. Ingots and the Bronze Age Copper Trade in the Mediterranean: a Progress Report. Expedition 17 (summer):31–39.

Assemblage and stratigraphy are fundamental concepts for understanding archaeological sites and these ideas bookend the Eastern Mediterranean Gallery. At one end is a mosaic made up of many small pieces of cut stone called tesserae. This object embodies the idea of horizontal proximity, the association or assemblage of objects found together in one context. At the other end of the gallery is an interactive display that engages the visitor in vertical stratigraphy, the layering of soils, architecture, and objects—sequences of contexts—at a site over time.

These principles also help us to understand objects, such as stone seals that were refashioned for new owners. The gallery displays seals of many shapes, sizes, and materials. Seals were closely tied to their owners’ identities because seals were used as a form of signature, by stamping or rolling the object in clay to make one’s mark for legal or administrative purposes. They were also used as amulets (see Hubbard, page 58).

A display about object reuse features recut Late Bronze Age cylinder seals from Kourion, Cyprus, one of which was illustrated in Expedition 64.2. Other seals in the Eastern Mediterranean gallery also have layers of carving. A display about royal greeting gifts includes a

reworked cylinder seal found at Beth Shean, Israel. This tiny object is 1.5 cm in height and less than a centimeter in diameter. Its colorful blue stone, lapis lazuli, comes from Afghanistan. Looking closely at this seal shows how it changed as it passed from owner to owner in Mesopotamia, Syria, and the southern Levant.

On the seal and in its modern impression, one can detect two scenes. Two figures are sharply cut with some depth into the stone. Between their backsides is a more shallowly engraved floral design flanked by connected spirals. While this pattern and the figures are now visible together, forming one viewing context, these two scenes were made at two different moments in time.

There are several clues to the object’s use life. First, the more angular figures visibly differ in carving style from the more curvilinear patterns. Second, the part of the seal with the two figures is taller than the portion with the floral and spiral patterns. On that part of the seal, the surface is worn down and the original design is no longer visible, possibly from wear over time but more likely due to purposeful abrasion. Third, the ends of the seal reveal that the hole drilled through the object is off center, positioned more toward the shorter side of the object. To redesign the seal, a carver worked more on the side with the floral and spiral patterns than on the side with the two figures, creating an asymmetry in the object’s shape.

Seen in impression, the two figures are a king with his right arm across his chest facing left and a female goddess, called lama, facing right with her two forearms raised up. These figures are characteristic of Mesopotamian seals

known as Old Babylonian. Usually, an inscription appears with these two figures. Likely this original design on the seal was cut in the 18th century BCE. The more shallowly engraved spiral and floral pattern is characteristic of Syrian seal carving. Parallels for parts of the floral and spiral design date as early as the late 18th to 17th century BCE, but its closest parallels are Late Bronze Age, close to the date of the object’s 15th to 14th century BCE find spot at Beth Shean. The spiral and floral pattern forms a new layer in the object’s history. It was carved over and fills the space where the inscription would be expected. Perhaps the inscription meant nothing to the new owner, leading to the seal’s alteration.

The seal’s edges are well worn from handling and the seal must have changed hands several times before its final deposit at Beth Shean between 1470 and 1300 BCE. During its lifetime, it also changed from a seal into a bead, perhaps valued most for its exotic blue color and less for the carvings on the seal. A cylinder seal’s piercing normally allowed the wearer to suspend the seal vertically on a cord, usually attached to the clothing with a toggle pin. Thus, it was on one’s person, but easily accessible for making impressions. Looking at the ends of the seal, however, there is one more clue to the object’s history. The wear on the hole itself is off to one side. This detail shows that someone likely wore this seal horizontally on a necklace at some point. It might still have had value as an amulet, but on a necklace it would have been much harder to use as a sealing tool.

Aruz, J., K. Benzel, and J.M. Evans, eds. 2008. Beyond Babylon: Art, Trade, and Diplomacy in the Second Millennium B.C. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Collon, D. 2005. First Impressions: Cylinder Seals in the Ancient Near East. Revised edition. London: The British Museum.

Smith, J.S. 2018. Authenticity, Seal Recarving, and Authority in the Ancient Near East and Eastern Mediterranean. In Seals and Sealing in the Ancient World: Case Studies from the Near East, Egypt, the Aegean, and South Asia, edited by M. Ameri, S.K. Costello, G. Jamison, and S.J. Scott, pp. 95–124. Cambridge: University of Cambridge.

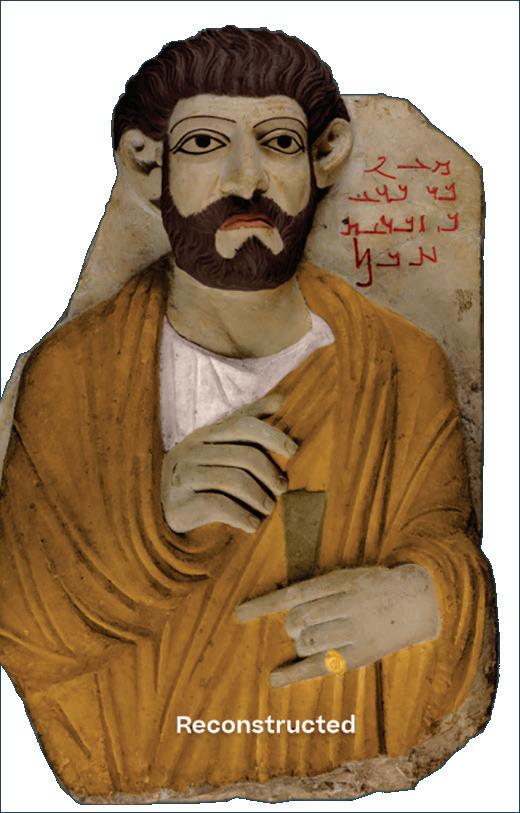

It is rare that an artifact lets us put a face on antiquity, making a museum visitor feel that they are standing directly before a person from the remote past. While every object in the Penn Museum’s Eastern Mediterranean Gallery tells a story about the people who made, used, altered, or even destroyed or discarded it, the anthropoid coffin lids from Beth Shean are uniquely compelling because they seem capable of returning their viewer’s gaze. In a case in the center of the gallery lies a single, complete sarcophagus, restored from fragments, much as it would have lain in situ in one of the rock-cut tomb chambers in Beth Shean’s Northern Cemetery when it was first interred (between 1200 and 1000 BCE). It is a great hollow cylinder with a domed top, large enough to contain a human body. Some 50 such sarcophagi were excavated at Beth Shean between 1922 and 1931, and more examples from around the same period have also been uncovered at sites in northern Israel, the Negev, and Gaza. The concept of burying the dead in this type of coffin would have arrived in Canaan from Egypt, where mummies had been buried in anthropoid sarcophagi since the Middle Kingdom (ca. 2040–1650 BCE).

Whereas Egyptian coffins were typically wood or stone, those found at Beth Shean are ceramic. It would have taken immense skill and ingenuity for local artisans to adapt the anthropoid coffin form to this new medium. The potters certainly would have been working on a scale they had never attempted in their usual production, even for a large handmade pithos like the one displayed at one of the gallery entrances. The sarcophagi were too large for firing in conventional kilns, and the variable temperatures of the open fires in which they were baked are likely responsible for the uneven surface coloration. Some examples began to show cracks after firing and had to be repaired with plaster or string bindings.

To create the overall form of the coffin, the potters built up walls of clay coils, which they then smoothed with their fingers. Next, they cut holes into the clay body: one in the base, sometimes three more in the back to let out fluids from the body as it decayed, and one in the top to make a lid.

Onto the lids the potters then applied clay faces, arms, and hands. The arms of the restored coffin in the gallery are crossed in the typical pose of Egyptian mummies, but the long, splayed fingers are distinctive. The face was rendered with high cheekbones, thin lips, and long, lanceolate eyes. This particular lid exemplifies what the first publications of the Beth Shean sarcophagi

called the “naturalistic style”: the facial features are subtly modeled, cohesive, and organic, notwithstanding a certain degree of abstraction.

On the other side of the case, the visitor encounters a wall of six disembodied faces, lids for which the rest of the sarcophagi could not be completely restored. On the left are four more “naturalistic” faces, exhibiting noticeable variants in the presence/absence of beards and the rendering of the ears and eyes, but using the same technique of modeling as the lid of the restored example.

Contrast these with the two lids on the right side, where we find an entirely different mode of rendering the face. In these examples, the features are not so gently and seamlessly combined into a face at the center of the lid. Instead, long, thin coils of clay denote the sharp contours of the eyes, the eyebrows, the ears, and the protruding nose. The ridge-like lines they form are arrayed all over the lid’s surface, creating a wide, flat, jack-o’-lantern-like

visage. These lids’ unnaturalistic distortions of the face earned them the moniker of the “grotesque style.” The terms “naturalistic” and “grotesque” have stuck in the current scholarship, although they require the caveat that today, at least, they are intended as merely descriptive and do not imply a value judgment that the naturalistic was the better of the two.

Why are two markedly different artistic styles both represented in the Beth Shean sarcophagi? Some scholars have proposed that the styles reflect change over time or different ethnic identities of the makers or occupants of the coffins. In particular, the headdresses of the “grotesque” lids look very similar to those worn by figures in certain New Kingdom Egyptian reliefs,

which represent groups of migrants from the Aegean region whom the Egyptians called “Sea Peoples.” According to the Egyptians, these Sea Peoples tried to attack Egypt, but the pharaoh Rameses III (1187–1156 BCE) defeated them and resettled them along the Eastern Mediterranean coast. Might the “grotesque style” coffins then be the burials of Sea Peoples stationed as mercenaries in the Egyptian garrison at Beth Shean? While conclusive evidence still eludes us, the parallels in the Egyptian reliefs and the reported presence of Sea Peoples in Egyptian imperial outposts point toward that identification.

The “naturalistic” coffins also invite questions over the identities of their occupants. The hairstyles, folded arms, and beards of their lids are all reminiscent of Egyptian coffins, which could suggest that personnel of Egyptian origin stationed in the garrison commissioned them as a way of approximating the burial customs of their native land. But the Beth Shean coffins show important differences from those of Egypt. For one thing, the dead at Beth Shean were not mummified but left to decompose inside the coffins. For another, grave goods were often placed within the terracotta sarcophagi, whereas Egyptian burials typically kept such materials in the tomb chambers outside the coffins. Because Egyptian mortuary customs were so firmly codified, especially with regard to the preservation of the individual, these deviations hint that the occupants of the Beth Shean tombs were not native Egyptians trying to replicate the mode of burial they knew, but rather local Canaanites who had been incorporated into the Egyptian imperial administration, emulating and adapting Egyptian practices for the prestige that came from their association with the ruling elite. The Egyptian-born officials who served at Beth Shean may have preferred to be returned home for burial rather than spend eternity in a foreign land.

The likenesses on the coffin lids, even of the “naturalistic” type, tend to be heavily schematized, but they have just enough particularizing features to make us think that we are looking at specific individuals (a pointed chin here, a pinched mouth there, a distinctive hairstyle, round cheeks, heavy brows, and so on). Are we wrong to view them as mimetic portraits in this way? We do not know which features, if any, were modeled

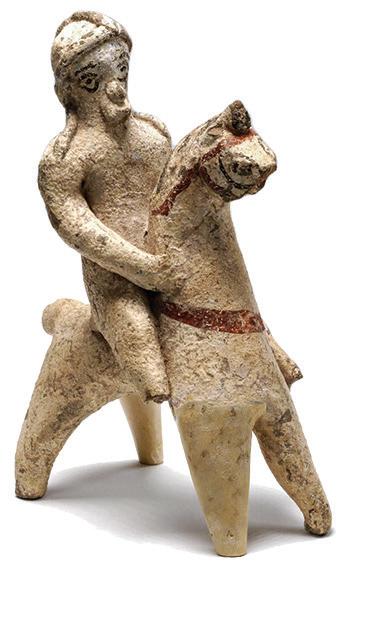

Terracottas placed inside the sarcophagi included both Egyptian-style ushabtis and simpler handmade figurines like this one; 31-50-110.

after individual faces and which were mere artistic idiosyncrasies, or whether some of these characteristics had a symbolic value beyond their reference to real people. Hairstyles, for instance, might signify social positions or connect the deceased with a divinity, like the Egyptian-style wigs and Osiris beards visible on some of the lids from Beth Shean.

But even if the sense we might have that we are looking at true likenesses of ancient individuals may be illusory, we must admire the artists’ abilities to conjure the impression of a personal presence. And when one stands in the gallery in front of these faces from the past, it is hard not to imagine that their mouths could open at any moment and divulge their secrets.

McGovern, P.E. 1994. Were the Sea Peoples at Beth Shean? In N.P. Lemche and M. Müller, eds., Fra dybet: Festskrift til John Strange, pp. 144–156. Forum for bibelsk eksegese 5. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanus and University of Copenhagen.

Oren, E.D. 1973. The Northern Cemetery of Beth Shean. Leiden: Brill.

Pouls Wegner, M.-A. 2015. Anthropoid Sarcophagi of the Late Bronze Age to Early Iron Age in Egypt and the Near East: A Re-Evaluation of the Evidence from Tell El-Yahudiya. In T.P. Harrison, E.B. Banning, and S. Klassen, eds., Walls of the Prince: Egyptian Interactions with Southwest Asia in Antiquity, pp. 292–315. Leiden: Brill.

Rakic, Y. 2014. Anthropoid Coffin Lid. In J. Aruz, S.B. Graff, and Y. Rakic, eds., Assyria to Iberia: At the Dawn of the Classical Age, pp. 44–45. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

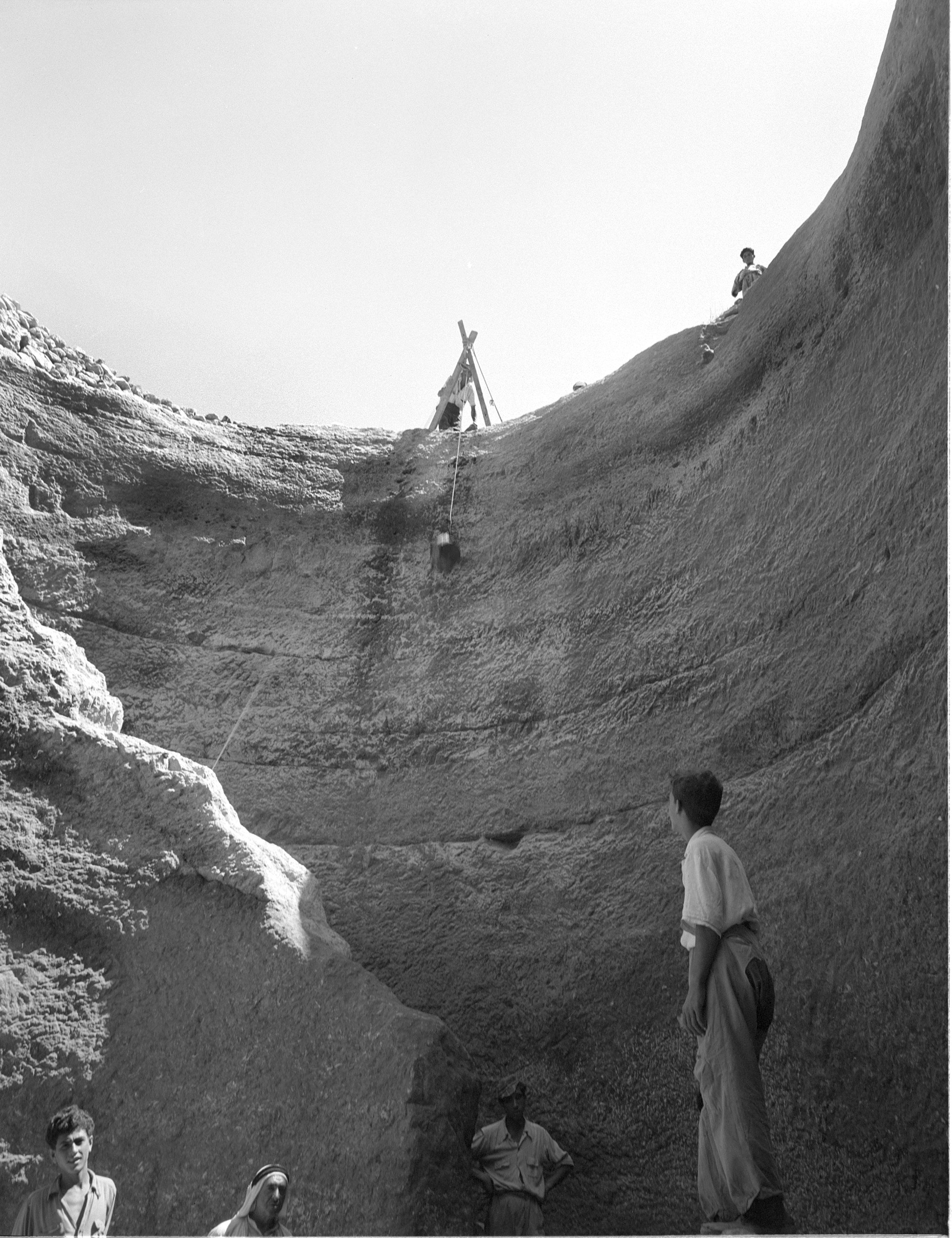

The great cylindrical shaft known as the “pool of Gibeon” after a reference in the Bible was cut into the bedrock under the town of Gibeon in ancient times to give access to the spring water below. A spiral staircase around the edge ended in an underground tunnel leading to the water chamber below; Gibeon, Expedition Records.

In Gibeon, Where the Sun Stood Still, James B. Pritchard, director of the Penn Museum’s 1956–1962 excavations at this site (modern el-Jib, Palestinian Territories), gave clear expression to what he found to be the ultimate significance of his discoveries there:

“The results of the excavations at el-Jib are unique in that they can be related with a high degree of certainty to specific events described in the Old Testament.…The tangible results of the archaeologist can both measure the trustworthiness of tradition and supplement it with additional information, which for one reason or another has been rejected or neglected in the written tradition.” (1962, ix).

The biblical archaeology of Pritchard’s day was motivated—in reaction to biblical skeptics—by a desire to empirically test the historicity of the events described by the Hebrew Bible. In 45 references in these texts, the town of Gibeon, only 5 miles from Jerusalem, appears as the setting of dramatic events in the biblical stories surrounding the rise of the kingdom of Israel. Pritchard considered that a material foundation for the basic veracity of these stories was supplied by his discoveries

at el-Jib: a fortified town of the right period, inscriptions mentioning Gibeon, and even a large water shaft that he equated with the “pool of Gibeon,” where the rival factions of David and Saul’s son were said to have clashed (2 Samuel 2:12–17.)

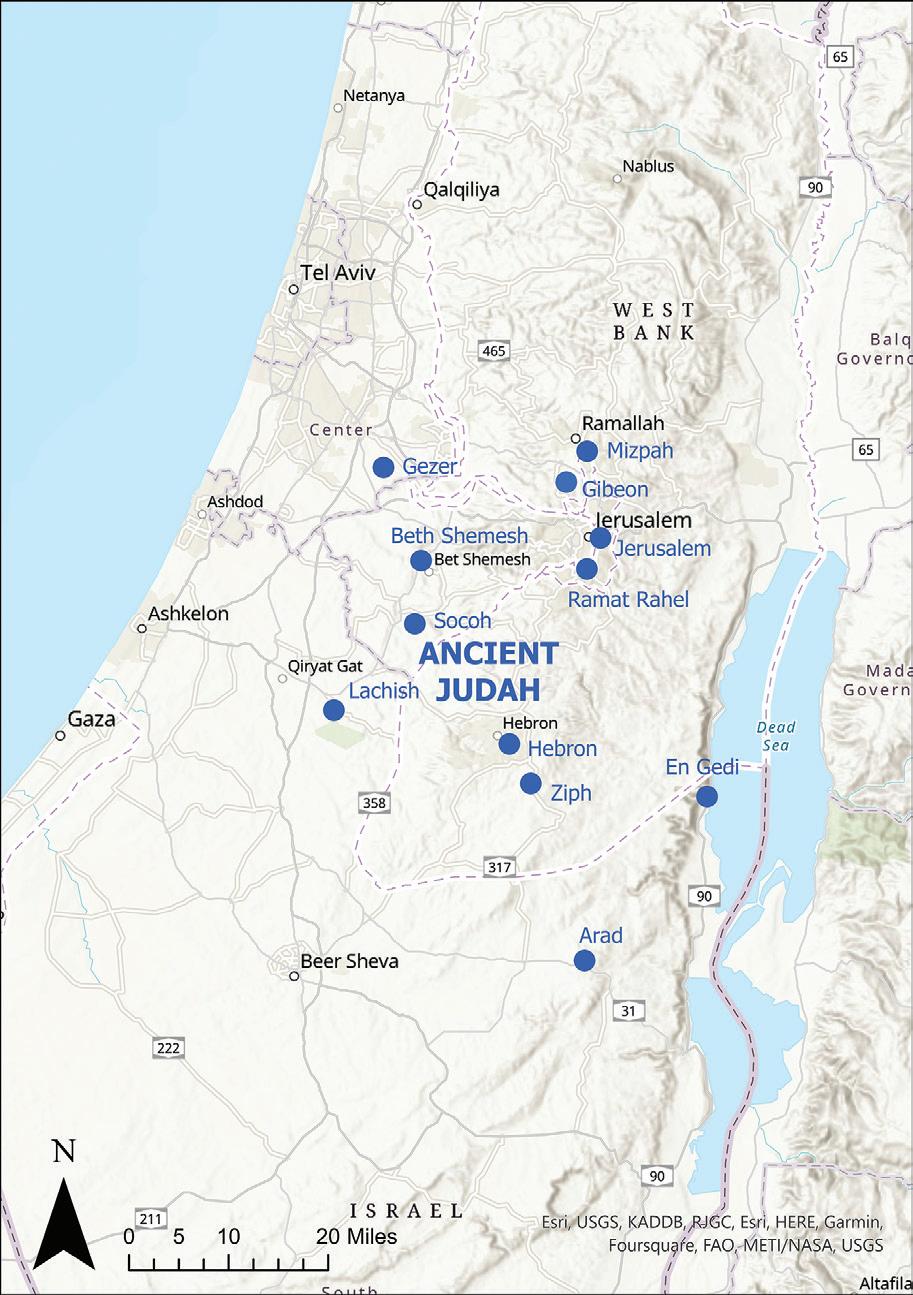

Today, however, most scholars consider archaeology a better tool for identifying long-term patterns in social and economic life and cultural history than for detecting short-term events. They also acknowledge how subjective readings of ancient texts can influence archaeological interpretation. In the decades since the excavations at Gibeon, archaeologists and historians have found more of interest in the broken objects discarded in the debris filling in that great cylindrical shaft–part of that “additional information” mentioned by Pritchard. Among this “trash,” stamped and inscribed jar handles and figurine fragments of the 8th to 6th centuries BCE play an important role in reconstructions and debates about a pivotal period in the history

Above: This storage jar handle bearing a lmlk (“belonging to the king”) stamp impression was found in the filling of the “pool” of Gibeon and probably dates to the late 700s or early 600s BCE. A winged scarab is framed by Old Hebrew letters reading lmlk above and mmšt below; 60-13-74.

of ancient Judah when it fell under the domination of the Assyrian, Babylonian, and Persian empires. Here, a closer look at the many stamp impressions attesting one aspect of Judah’s administrative system in this period will demonstrate how such fragments can be assembled to tell part of a larger story.

In the early 1st millennium BCE, Israel and Judah were among the many small Eastern Mediterranean kingdoms that developed in the power vacuum resulting from the fall or decline of previously dominant great empires. However, it was not long before Assyria, in northern Mesopotamia to the east, recovered strength and began to assert its power over neighboring kingdoms. By the late 700s BCE, the Assyrians were knocking on the door of Israel and Judah, and when Israel resisted, the kingdom was conquered and annexed, with many of its people deported to other lands. After its own nearly disastrous attempt at resistance, Judah fared better in the 600s BCE through compliance

with Assyrian demands for tribute and loyalty. The Babylonians of southern Mesopotamia then conquered Assyria in 612 BCE and sought to take over its former subject territories in the Eastern Mediterranean. Finding Judah again resistant, in 586 BCE they sacked Jerusalem, burned its temple, and deported much of the population to Babylonia. When Cyrus the Great of Persia (modern Iran) then conquered Babylon in 539 BCE, he sought to win over former Babylonian subjects by reversing earlier policies. This included allowing many exiles, among them the Judeans, to return to their homeland and rebuild. Judah became a largely self-governing province called Yehud. The demands and depredations of imperial domination, together with the expansion of trade and cultural connections that these empires helped bring about, had a profound effect on Judah, not only politically, but also on its economy, society, and religion. More than ever before it was connected to the wide world beyond its borders; in reaction Judeans developed a distinctive identity and historical consciousness.