THE FIRST CITIES OF SUMER

After three decades, a dig in southern Iraq reopens— and revolutionizes the story of Mesopotamia

After three decades, a dig in southern Iraq reopens— and revolutionizes the story of Mesopotamia

Go an a gastronomical journey through food and plant remains— from 600-year-old potatoes to 6,000-yearold strawberries!

SUMMER 2023 | VOLUME 65, NUMBER 1

1 4 A Trip to Troy with Homer

By C. Brian Rose and Sheila Murnaghan6 Zooming in on Asian Textiles

By Katy Rosenthal10 Kara Tepe: A Conversation Across Time

By Katherine Blanchard and Michael Campeggi14 In Search of an Archaeology That Uplifts

By Robert J. Vigar18 Greetings from Lagash

Back to Lagash

By Holly PittmanIt’s Five O’Clock, Sumer

By David MulderA New Story of Sumer's First Cities

By Reed GoodmanPartners in Search of the Past

By Zaid Alrawi38

A conversation with Lynn Meskell

2 From the Editor

3 From the Williams Director

44 In the Labs

46 Academic Engagement

48 Learning and Community Engagement

50 Welcome News

54 Membership Matters

56 Remembering Robert Ousterhout

PENN MUSEUM 3260 South Street, Philadelphia, PA 19104-6324 Tel: 215.898.4000 | www.penn.museum

The Penn Museum respectfully acknowledges that it is situated on Lenapehoking, the ancestral and spiritual homeland of the Unami Lenape.

Hours

Tuesday–Sunday: 10:00 am–5:00 pm.

Closed Mondays and major holidays.

Guidelines for Visiting

The Museum prioritizes a safe and enjoyable experience for all. Learn more about our guidelines for visiting, including booking timed tickets, at www.penn.museum/plan-your-visit.

Admission Penn Museum members: Free; PennCard holders (Penn faculty, staff, and students): Free; Active US military personnel with ID: Free; K-12 teachers with school ID: Free

Adults: $18.00; Seniors $16.00; Children (6-17) and students with ID: $13.00; Children 5 and under: Free.

Museum Library Call 215.898.4021 for information.

Above: Student curators Anna Hoppel, Sydney Kahn, and Qi Liu watch as Conservator Julie Lawson removes charred residue from a ceramic sherd for carbon-14 dating; photo by Megan Kassabaum.

On the Cover: The sun rises over the land that was once ancient Sumer. This reopened dig site in southern Iraq had been off limits to researchers for the past 30 years.

WHEN I BECAME THE EDITOR OF EXPEDITION in April 2023, I spent a few days thumbing through decades of back issues in the magazine archives. Story after story, I found myself stumbling over the same word: sherd. There were sherds from Mesopotamia, from Turkey, from Guatemala. Sherds come from all corners of the earth, but what on earth are sherds?

To an archaeologist, sherd is a foundational word—one that has no replacement. But like many of you, I’m not an archaeologist, or an anthropologist, and I have no expertise in ancient history. I’m here because I'm a writer and editor who has worked with hundreds of academics and researchers to tell their stories to the general public, most recently as an editor of University of Washington Magazine in Seattle. I’ve also been a journalist for 10 years, freelancing for publications such as WIRED, The Wall Street Journal, and The Philadelphia Inquirer.

Thanks to Penn Museum’s YouTube channel, I quickly learned the definition of sherd from one of our curators, Megan Kassabaum: “It’s a broken piece of pottery found at an archaeological site.” Like its more common cousin, “shard,” it’s a piece that has broken off from a larger object, as fragile things tend to do over thousands of years. Ancient cups, bowls, and containers often come to us as scattered sherds. Buried in centuries of sediment, they are ceramic echoes of lost civilizations.

To learn more about this, I went to see Katherine Blanchard, the Fowler/Van Santfoord Keeper of the Near East Section (p. 10). Blanchard spends her days surrounded by shelves upon shelves of ancient clay. “A sherd is a fragment of everyday life,” she told me. “It’s a beautiful and hidden fragment, and you can tell so much from a single piece.” Sherds have what Blanchard calls “extra secrets” that whole objects don’t have. Those broken edges let us peek inside the object: We can see the material it’s made from, if the clay is local or imported, and if it's been fired or left outside to dry. A sherd can also be used to mark and measure time, based on the style it was made in. For these reasons, sherds represent the process of history: They come to us in pieces, which we can arrange to tell different stories. We know that there will always be more pieces, that our stories will always have missing chapters.

This issue’s cover story is about the Museum’s return to southern Iraq (p. 18). You will read about Holly Pittman’s trailblazing effort to reopen a historic dig site. While our team will continue to lead this excavation, these days the sherds they find, like almost everything else, will remain in the host country. What our people will bring back are the stories, and you will always be able to find them in this magazine.

EDITOR

Quinn Russell Brown

PUBLISHER

Amanda Mitchell-Boyask

ASSOCIATE PUBLISHER

Emily Holtzheimer

ARCHIVES AND IMAGE EDITOR

Alessandro Pezzati

GRAPHIC DESIGN

Colleen Connolly

Christina Jones

COPY EDITOR

Page Selinsky, Ph.D.

ACADEMIC ADVISORY BOARD

Marie-Claude Boileau, Ph.D.

Richard Leventhal, Ph.D.

Simon Martin, Ph.D.

Janet Monge, Ph.D.

Kathleen Morrison, Ph.D.

Lauren Ristvet, Ph.D.

C. Brian Rose, Ph.D.

Page Selinsky, Ph.D.

Stephen J. Tinney, Ph.D.

Jennifer Houser Wegner, Ph.D.

Lucy Fowler Williams, Ph.D.

CONTRIBUTORS

Jessica Bicknell

Marie-Claude Boileau, Ph.D.

Jennifer Brehm

Kris Forrest

Sarah Linn, Ph.D.

Jo Tiongson-Perez

Alessandro Pezzati

PHOTOGRAPHY

Jennifer Chiappardi

Colleen Connolly

Francine Sarin

(unless noted otherwise)

INSTITUTIONAL OUTREACH MANAGER

Thomas Delfi

QUINN

RUSSELL BROWN, EDITOR© The Penn Museum, 2023 Expedition® (ISSN 0014-4738) is published three times a year by the Penn Museum. Editorial inquiries should be addressed to expedition@pennmuseum.org. Inquiries regarding delivery of Expedition should be directed to membership@pennmuseum. org. Unless otherwise noted, all images are courtesy of the Penn Museum.

Our last issue of Expedition was a grand celebration of our new Eastern Mediterranean Gallery: an immersive, innovative look at an ancient cultural crossroads that gave rise to developments that still shape our contemporary world, from three of the world’s widespread monotheistic religions to the alphabet. I was pleased to speak with many of you during the gallery's opening weekend, which reminded me that our Museum members really are a community; you support our work, and we gather together to enjoy the fruits of our labor in celebrations like this one.

Of course, these celebrations (and the galleries they celebrate) would be impossible without the cutting-edge research of Museum curators and affiliated scholars. Looking over the articles collected here, I’m impressed as always by the depth of research on display, and the deep reflection our scholar-curators demonstrate around their discoveries. This issue of Expedition is full of fresh insights from the field, including a fascinating article on recent excavations in Lagash, where researchers have uncovered a 5,000-year-old tavern that may revolutionize our understanding of the social order in Ancient Mesopotamia. This project has received attention in both the national and international press, demonstrating that our Museum, building on its long and robust tradition of fieldwork, remains at the forefront of the discipline.

This is true not only in the world of field archaeology, but in the larger realm of cultural heritage preservation. As the world grows more interconnected and complex, efforts to preserve global heritage have moved beyond the care and upkeep of monuments and other massive sites and towards a more nuanced, locally oriented approach—and our Museum-affiliated scholars are in the vanguard of this movement, as well. This issue features an interview with our own Lynn Meskell about the way cultural heritage preservation fits into geopolitical clashes and international conflict, and how heritage preservation is a part of mediating the effects of war, terrorism, and other forms of political violence (p. 38). Today’s heritage preservation projects also have a community focus. As Robert J. Vigar explains in this issue, collaborating with local communities is crucial to the long-term success of

any project seeking to preserve cultural heritage (p. 14).

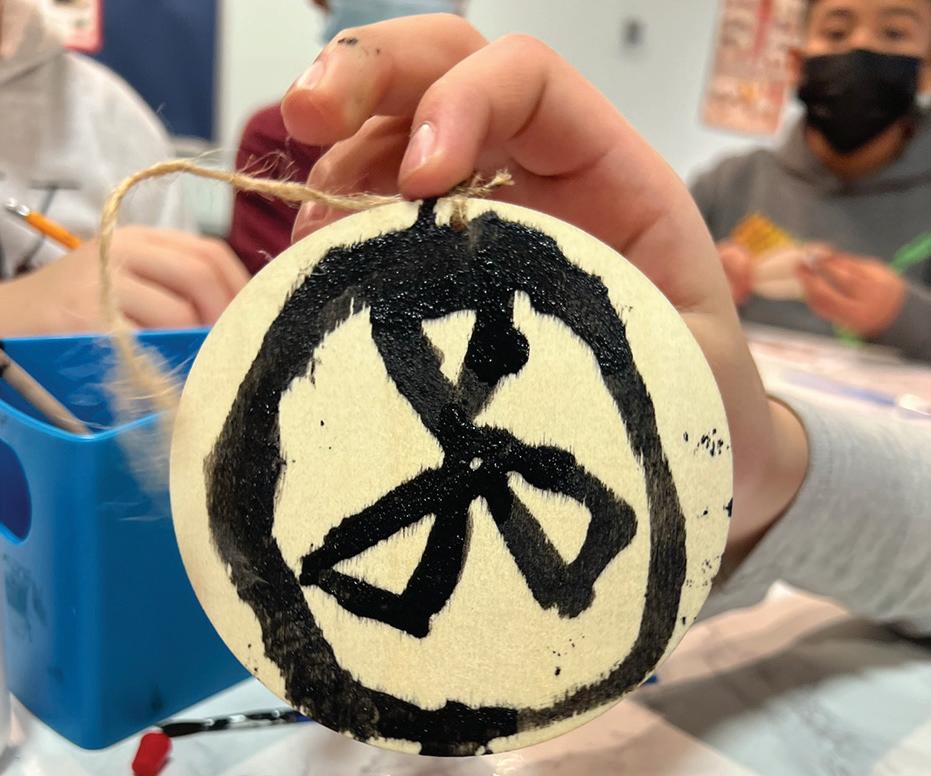

The Museum’s community focus is evident closer to home, as well, in our recent success with community partnerships. Tia Jackson-Truitt, our Chief Diversity Officer, and Jennifer Brehm, our Merle-Smith Director of Learning and Community Engagement, recently secured a prestigious program grant from the Sachs Program for Arts Innovation for Your Food Story, a program in which Sayre High School students will make connections between their local food culture and the ancient culinary customs on display in our new exhibition Ancient Food & Flavor. In addition, the Museum was recently selected for the first Culture and Arts Access award from the Mexican Cultural Center, in honor of our community-focused programming, like our annual CultureFest! Día de los Muertos program (p. 51).

Both globally and in the city we call home, the Penn Museum continues to involve communities in the excavation, preservation, and celebration of our common heritage. Thank you for being part of this ongoing investigation into our shared human story.

Warm regards,

CHRISTOPHER WOODS, PH.D. WILLIAMS DIRECTOR

CHRISTOPHER WOODS, PH.D. WILLIAMS DIRECTOR

The Spring 2023 interdisciplinary seminar “Troy and Homer,” co-taught by C. Brian Rose and Sheila Murnaghan, focused on the city of Troy both as an archaeological site and as the setting of the Trojan War. The class considered Homer’s Iliad together with the topography of the site of Troy in order to address a series of interrelated questions regarding literature, history, and archaeology.

Participating students were able to visit the citadel mound of Troy along with other important sites in the surrounding area and in Istanbul. Seventeen graduate students took part, 16 from Penn (Graduate Groups in Classical Studies, Ancient History, and the Art and Archaeology of the Mediterranean World) and one from Bryn Mawr (Classical and Near Eastern Archaeology).

The trip to Troy during spring break in March of 2023 was made possible by generous gifts from Charles K. Williams II and Alix and Keith Morgan, as well as support from Penn’s Departments of Classical Studies and the History of Art. The Lauder Institute also awarded a Faculty Course Development Grant for the project.

LED BY DRS. MURNAGHAN AND ROSE and including playwright Ellen McLaughlin (New York) and Dr. Andrew Stone, former staff psychiatrist and director of the Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Clinical Team at the VA Medical Center in Philadelphia, our trip was a great success. Dr. Stone participated in the seminar throughout the semester and provided a very valuable perspective on combat trauma in both antiquity and the contemporary world, juxtaposing the experiences of Homeric warriors with those of veterans who fought in Iraq and Afghanistan. Ellen McLaughlin is an awardwinning playwright whose plays include Ajax in Iraq, Iphigenia and Other Daughters, The Trojan Women, Helen, The Persians, and Oedipus. She directed all of us in a reading of her play The Trojan Women, which was staged in the Roman Odeion at Troy; reflecting the play’s universal themes of exile and displacement after war, the cast delivered their lines in ten different languages.

We arrived in the city on Friday, March 3, and spent the following day touring Istanbul: the Hippodrome, Hagia Sophia, the Archaeological Museum, and the underground cisterns of Justinian. On Sunday, March 5, we traveled by van to Çanakkale, where we stayed for five nights. The hotel was very close to the colossal wooden horse used in the 2004 Warner Brothers film Troy with Brad Pitt, which is on long-term loan to Çanakkale. We spent all day Monday, March 6, at the site of Troy, where there were six oral reports by the students. On Tuesday we traveled to the tomb of Achilles and the sites of Alexandria Troas, the Smintheion (Temple of Apollo), and Assos (Temple of Athena), with another three oral reports. On Wednesday, March 8, we spent the morning at the Troy Museum, where the final eight reports were given.

Our performance of The Trojan Women was staged from 3:00–4:00 pm that day at Troy, followed by a lecture concerning archaeological surveys on the Gallipoli peninsula, delivered by Reyhan Körpe, professor of ancient history at Çanakkale University. The current director of the Troy Excavations, Rüstem Aslan, also attended, and gave the students a tour of Carl Blegen’s Excavation House at Troy earlier that day. On Thursday, March 9, we visited the Gallipoli memorials, during which we discussed the poetry written by British soldiers during and after the

campaign, in which they compared themselves to Homeric warriors.

On Friday, March 10, we returned to Istanbul, traveling across the new Dardanelles bridge, constructed almost 2,500 years after Xerxes built his pontoon bridge in the same location. The trip home provided plenty of opportunities to review all that we had seen and learned during the week.

C. Brian Rose is the Ferry Curator-in-Charge of the Mediterranean Section at the Penn Museum and the James B. Pritchard Professor of Archaeology in the Department of Classical Studies and the Graduate Group in Art and Archaeology of the Mediterranean World. He was head of Post-Bronze Age excavations at Troy for 25 years beginning in 1988. Sheila (Bridget) Murnaghan is the Alfred Reginald Allen Memorial Professor of Greek, Department Chair and Faculty Co-Director, PostBaccalaureate Program in the Department of Classical Studies.

BY KATY ROSENTHAL

BY KATY ROSENTHAL

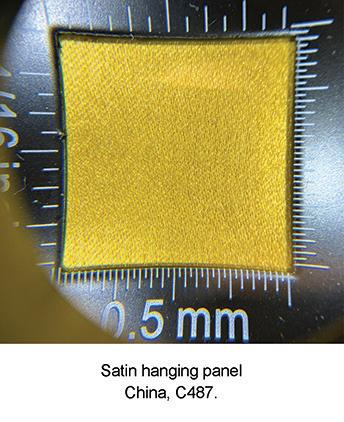

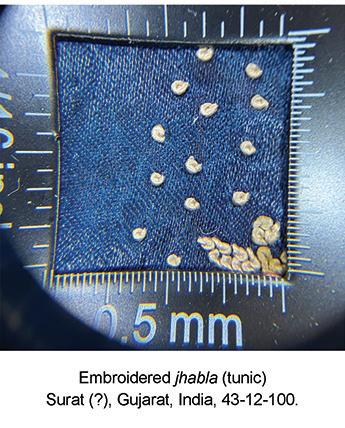

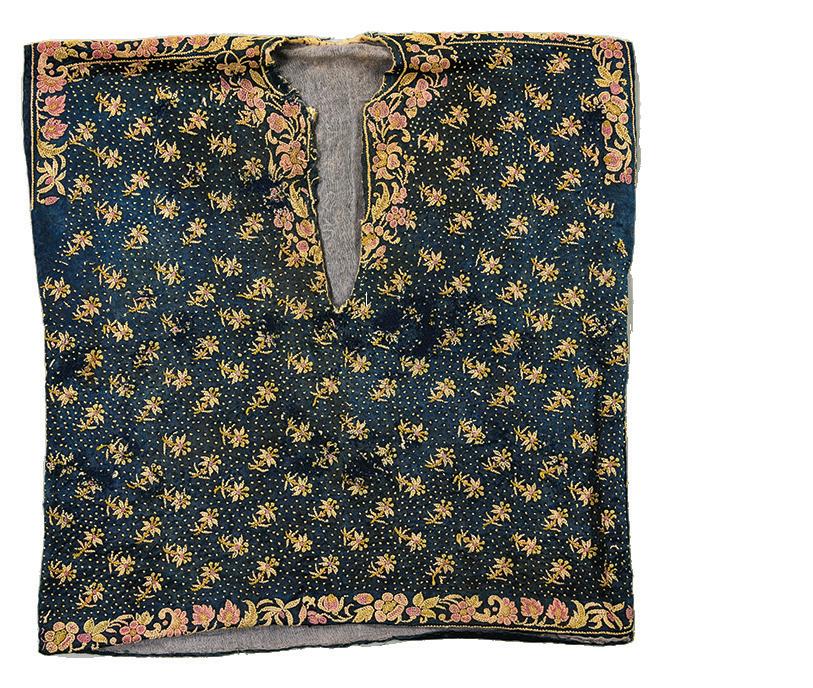

THE PENN MUSEUM has recently made a huge investment in its collection of textiles held in the Asian Section, photographing thousands of examples and making them available online. Much of the collection was accessioned before the establishment of the Penn Museum’s Registrar’s Office in 1929, and nearly all the rest before our current documentation standards had been developed. Photographs are crucial for bridging gaps in data because they allow the collection to be searched visually. In documenting the Asian section, care has been taken to capture details and multiple views of the textiles in order to approximate the experience of in-person viewing. While handling objects in person is ideal, the benefits of high-quality photographs are clear, especially for providing digital access to researchers who might not otherwise be able to see them up close. The scope of the collection makes it all the more important that such a documentation effort aids international access in particular.

I came to the Penn Museum just after the completion of this photography project as a graduate student

in History of Art at Bryn Mawr College. Working in the collection three days a week over the course of Summer 2022 was intended to complement the writing of my M.A. thesis, which focused on embroidered silk garments worn by the Parsi community in India beginning in the nineteenth century. My goals were three-part: to enhance my thesis research with material evidence, to increase my familiarity with a wide range of textiles from South Asia, and to bolster the data of the newly photographed pieces with any information I could provide. As my background is in textile production and design, I proceeded with an emphasis on identifying the techniques used in making them.

Equipped with a digital microscope, a loupe with a measuring scale, and a stack of books featuring photographed catalogs, I began to tackle the imposing list of object entries. Many of the textiles were collected in related groups, such as fine wool or pashmina choga (robes) from Kashmir. I pulled objects from collection storage group by group, recording what I discovered about their weave structure and the techniques of their

embellishments. Sifting through published material, I aimed to identify relevant comparanda to cross-check the information in the Penn Museum’s entries. When I found inconsistencies, I reevaluated the existing data and made suggestions for updates, and when more robust information was published on the comparison material, I took notes on what applied to the objects in question. As I came across non-English terms associated with the material, I took care to include them. Keeping track of my citations was of the utmost importance to the process, as the ability to audit the sources of information will assist others who come after me in the evaluation and reevaluation of the information moving forward.

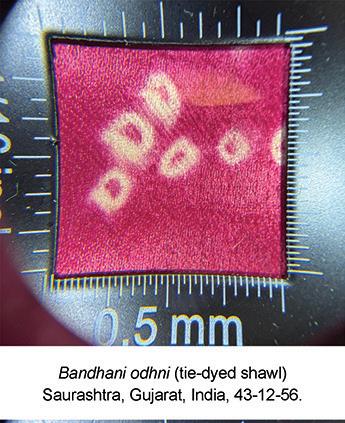

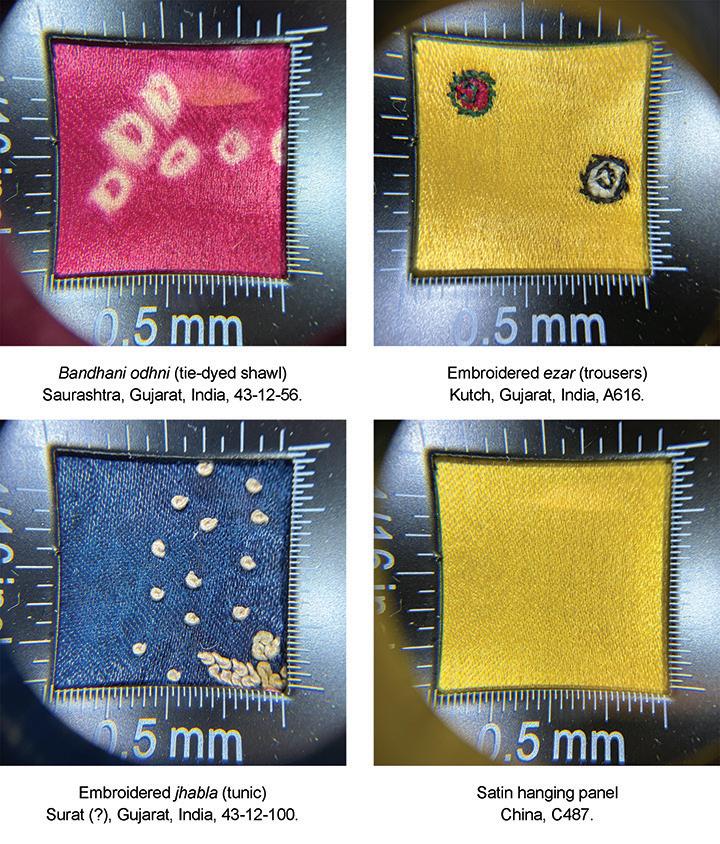

During this process I captured many magnified photographs which will accompany my notes on weave structures, material compositions, and embellishment techniques, hopefully providing clarity for those researching the technical aspects of textiles. One such series of captures yielded evidence for my own research on embroidered silk garments worn by the Parsi community. The embroideries resulted from Parsi involvement in trade conducted with China under the expansion of British imperialism, and the silk ground fabrics for the embroideries were predominantly produced in China. Pulling objects from across materials in the Asian Section, I compared four items with silk satin ground fabrics from the late 19th or early 20th centuries: a bandhani odhni (tie-dyed shawl) from Saurashtra in Gujarat, India; an ezar (pair of trousers) embroidered for the Muslim community in the Banni region of northern Kutch in Gujarat; a

jhabla (tunic) embroidered for the Parsi community in Gujarat, likely in Surat; and an embroidered hanging from Qing-dynasty China. My analysis of the eightend satin weave structures revealed that they were all indistinguishable at the observable level. Additionally, the ‘hand’ of the textiles—which can only be evaluated in person and includes factors such as sheen and drape—were all alike. This finding substantiates past research that suggested that silk satins from China were the inspiration for a satin fabric created by weavers in Gujarat referred to as gaji. The popularity of gaji silk satins for fine garments embroidered in midnineteenth to early twentieth century Kutch attests to the influence of Parsi merchants importing Chinese silks into western India during this period.

My work on the collection has only scratched the surface. Other areas in need of research, including inscription translation and iconographic analysis, will benefit from the expertise of future scholars. As Penn Museum Keeper Stephen Lang told me, the Asian Section also seeks further information on its sizable collection of textiles from beyond South Asia, including many from China, Japan, and Southeast Asia. Those working in the section are eager to hear from voices in the international field and always encourage visits from researchers. The primary goal of the photography project was to increase the accessibility and usefulness of these materials, including the accuracy of information, and suggestions for improvement are welcome.

I am grateful to Sylvia Houghteling, Assistant Professor of History of Art at Bryn Mawr College, for arranging this opportunity; to Stephen Lang (Lyons Keeper of Collections, Asian Section) for providing support for this project and generously opening the collection to me; and to Adam Smith (Associate Curator, Asian Section) and Dwaune Latimer (Friendly Keeper of Collections, African Section) for their assistance in accessing it.

Since some of my main sources were Victoria and Albert Museum publications, much of the comparanda material I compiled is provided through their website (www.vam.ac.uk).

Askari, N., and L. Arthur. 1999. Uncut Cloth: Saris, Shawls and Sashes. London: Merrell Holberton. Cohen, S., et al. 2012. Kashmir Shawls: The TAPI Collection. Mumbai: Shoestring Publisher in association with Garden Silk Mills Limited. Crill, R. 2015. The Fabric of India. London: V&A Publishing.

Crill, R., et al. 2021. Indian Textiles: 1,000 Years of

Art and Design. Washington, D.C.: The George Washington University Museum and The Textile Museum; London: Hali Publications Limited.

Fotheringham, A. 2019. The Indian Textile Sourcebook: Patterns and Techniques. London: Thames & Hudson and V&A Publishing.

Gillow, J., and N. Barnard. 1991. Traditional Indian Textiles. London: Thames and Hudson Ltd.

Hatanaka, K. 1996. Textile Arts of India. San Francisco: Chronicle Books.

Linton, L. 1995. The Sari. London: Thames and Hudson Ltd.

Murphy, V., and R. Crill. 1991. Tie-dyed Textiles of India. London: Victoria and Albert Museum.

Shah, S., and R. Crill. 2022. The Shoemaker’s Stitch: Mochi Embroideries of Gujarat in the TAPI Collection. New Delhi: Niyogi Books.

Shah, S., and T. Vatsal. 2010. Peonies & Pagodas: Embroidered Parsi Textiles: TAPI Collction. Surat: Garden Silk Mills.

Vogelsang-Eastwood, G., and W. Vogelsang. 2021. Encyclopedia of Embroidery from Central Asia, the Iranian Plateau and the Indian Subcontinent. London: Bloomsbury.

Making Workshops are hosted by the Museum’s Academic Engagement Department to encourage Penn undergraduate and graduate students to become more familiar with the objects in the collection by using their tactile senses. Because of her background in textile production and design, Katy Rosenthal was invited to host a workshop on the embroidery techniques used in the Museum’s collection of ornately embroidered Mandarin squares. Mandarin squares are embroidered badges of rank, sewn onto the outer coats of Chinese statesmen, military officials, and their wives from the 15th to 20th centuries CE. The Museum’s collection includes more than 150 Mandarin squares collected by Brigadier-General J.S. Letcher during the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937-1945), when he was stationed in Beijing.

At the beginning of the workshop, Penn Museum Keeper Stephen Lang gave a talk explaining the intricate and labor-intensive embroidery techniques used in the squares, illustrated by magnified detail images. Students then had the opportunity to examine a rich array of squares laid out on the table. Using a projector attached to a loupe to enable students to see her work, Katy Rosenthal then demonstrated simpler embroidery techniques to create a floral design, and coached and encouraged students as they created designs of their own using thread, cloth, and embroidery hoops.

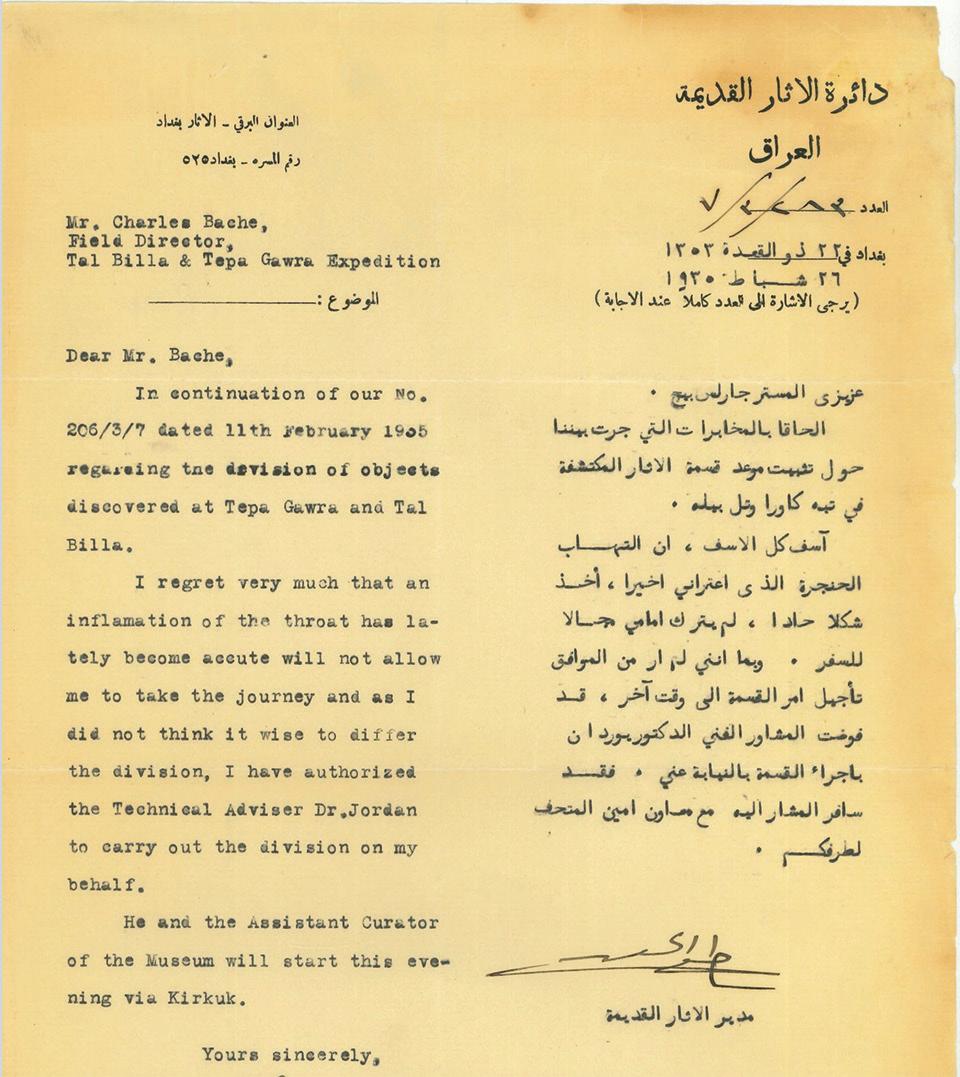

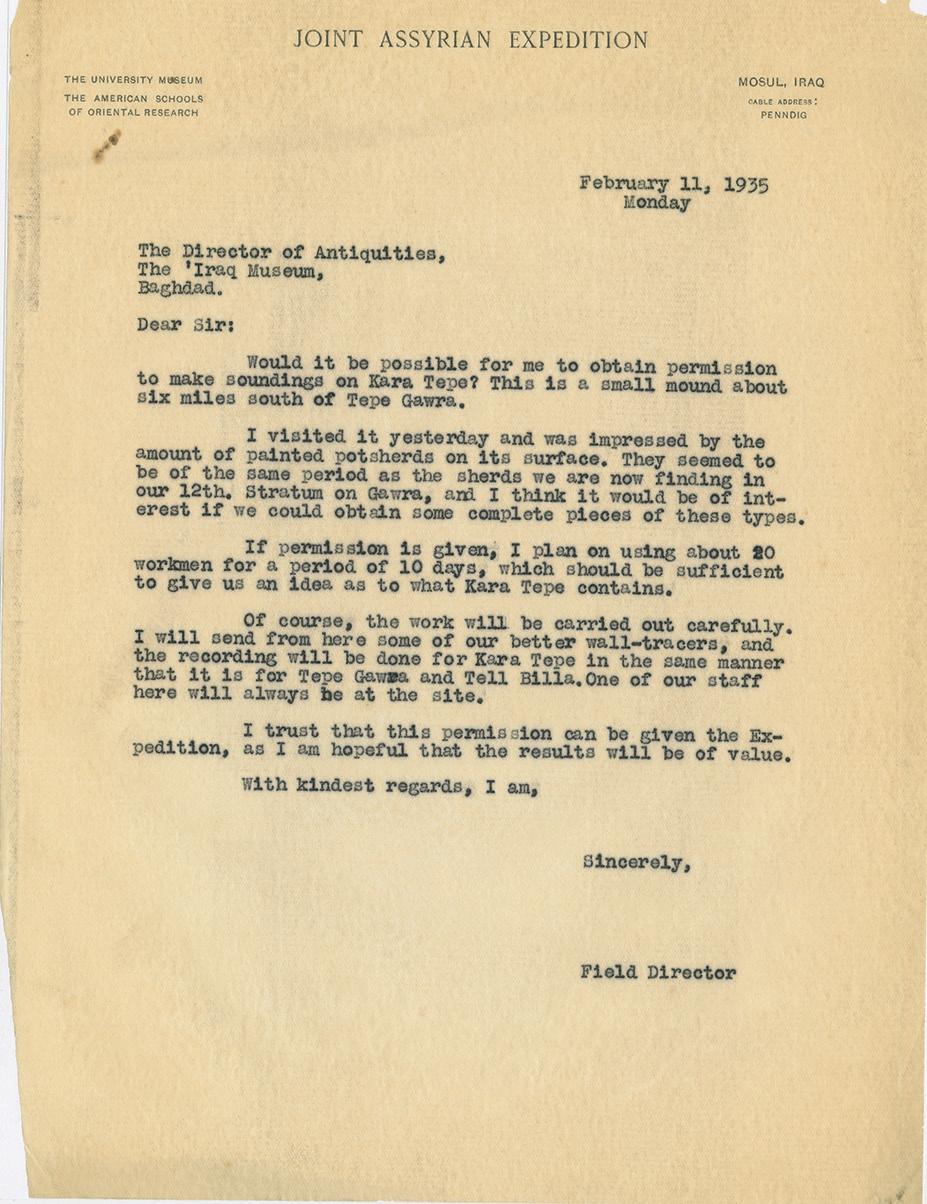

THE STRENGTH OF THE PENN MUSEUM’S NEAR EAST COLLECTION lies in the vast number of objects that come from the Museum’s own excavations. Each of these excavations was documented, and these archival records live at the Museum to this day. When requests come in to see unpublished material or little-known documents, the Penn Museum Archives can step in and help solve a mystery, connecting current and past research and creating space for a conversation across time.

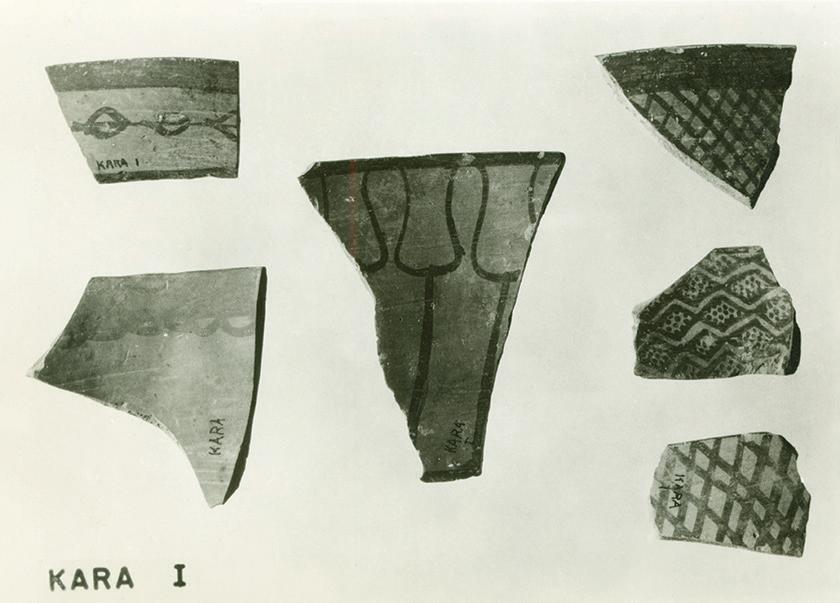

A study of one recent case shows a look behind the archival curtain. Researcher Michael Campeggi requested to see materials from Kara Tepe (Black Hill) in Iraq, a site the Museum excavated in the 1930s. During those years the Museum was excavating in northern Iraq at Tepe Gawra (Great Mound), a site

about 18 miles northeast of Mosul, led by E.A. Speiser and C. Bache. These missions are now well-known for uncovering the uninterrupted record of late prehistoric and protohistoric occupation. These communities ranged from the Halaf (6th millennium BCE) to the Late Chalcolithic (4th millennium BCE), which today still stand as a landmark reference point for this time and place in human history.

While the excavations at Tepe Gawra are wellpublished, very little is known about the team’s activity at the nearby site of Kara Tepe. In fact, Kara Tepe is only briefly mentioned—in a single sentence—in the 1950 Gawra report: “…excavations were carried out for five days at a neighboring mound, called Kara Tepe, where

remains of the so-called Tell Halaf period were discovered.” Elsewhere, the site is also mentioned by Ismail Hijara in his 1997 work on the Halaf period in Northern Mesopotamia.

The interest in Kara Tepe, and notably the materials the Museum has about it, has taken shape in the Ph.D. research project of Michael Campeggi, which explores the cultural changes between the Halaf (6th millennium BCE) and the Ubaid (6th–5th millennia BCE) periods in the Eastern Tigris region in Northern Mesopotamia, with a special focus on the site of Helawa in the Erbil Plain. Archaeological finds in 20th century point to the Halaf and Ubaid horizons in the Mosul area at sites such as Nineveh, Tell Arpachiyah and Tepe Gawra. This is shown through architectural remains—such as the typical Halaf circular structures (referred to as “tholoi”) and tripartite Ubaid buildings—along with painted ceramics and other small finds. How does this connect back to the archive? Putting fresh eyes on unpublished material from Kara Tepe could reveal new data on the Late Neolithic and Chalcolithic periods in a key area of Northern Mesopotamia.

Campeggi then contacted Katherine Blanchard, the Keeper of Near Eastern Collections, to inquire about the pieces. Blanchard went through storage to identify and photograph more than 60 items from Kara Tepe, the majority of which were painted Halaf ceramic sherds, with naturalistic and geometric decorations, as well as Ubaid sherds. The next step was for Campeggi to visit Blanchard and the Museum in person, where they could explore the Archives to search for documentation related to the excavation. There wasn’t much to go on, just a single sentence about the 1935–1936 season at Gawra, as well as a handful of sherds labeled with field numbers. And, of course, the name of the site. Because miracles happen in the Penn Museum Archives, access was granted to two maps. One was in German, detailing a site named Kara Tepe—but in Iran, not Iraq. (There is more material from that Iranian site, from the 1960s excavations in the area by Dr. Robert Dyson.) The other map was an oversized plan of a site with circular features (possibly Halaf) labeled Kara Tepe and dated February 19, 1935. Immediately the discovery was clear: This was the site plan for the 1930s Iraq excavation.

“Because miracles happen in the Penn Museum Archives...”

A search through images associated with the excavators of Gawra turned up ethnographic images depicting the landscape, workmen in the trench at Kara Tepe, and even puppies. And within the Archival documentation of the excavation of Tepe Gawra, there was the permit to excavate a sounding (in square plots, each measuring five by five meters) at Kara Tepe to see what the site held. A second visit to Archives even located the field register for those few days.

Also unearthed: letters written by Charles Bache describing the potential of the site, telling how he “…lunched, and prowled the surface, and picked

up dozens and dozens of fine painted pot-sherds” on the mound, which he immediately related back to those from the ongoing Gawra excavations close by.

At the close of the excavations, all the materials, except for the ones in the Penn collection, were sent to the Iraq Museum in Baghdad. That said, four sherds from Kara Tepe can currently be seen at the Museo Internazionale delle Ceramiche in Faenza, Italy. These objects went to Italy in the 1950s on an exchange from Baghdad, so there are potentially more sub-collections from the site, in other locations around the world, that are not yet known.

As more excavations and field projects open up in northern Iraq, and researchers request to see parallel materials to those of the newer excavations, this project highlights 64 pieces from Kara Tepe, Iraq, which are now visible on the Penn Database and available for active research. This is in addition to the more than 4,000 objects from Gawra, of course, in the Near East Section of the Museum. The collection here is relatively small, but it remains an incredibly rich resource to the field.

Katherine Blanchard is the Fowler/Van Santvoord Keeper of the Near Eastern Collection. She received her A.B. in Classical and Near Eastern Archaeology from Bryn Mawr College and her M.A. in Art History from Southern Methodist University. She has worked as a field archaeologist and registrar at Museum sites in Italy, Syria, and Israel, and she has the honor of working with researchers from all over the world on a daily basis. Michael Campeggi is a Ph.D. candidate in Near Eastern Archaeology at the University of Milan, Italy. He received his B.A. and M.A. in Archaeology at the Alma Mater Studiorum, University of Bologna, and has participated in excavations in Italy, Turkey (Karkemish, Kültepe), Iraq (Qadissiyah, Nineveh), and Iraqi Kurdistan (Tell Helawa).

Bache, C. 1935. The Joint Assyrian Expedition: Letters from Mr. Bache. Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 58, 1+5-9.

Hijara, I. 1997. The Halaf Period in Northern Mesopotamia. London: NABU. Gut, R. 1995. Das präistorische Ninive: zur relative

Chronologie der frühen Perioden Nordmesopotamiens. Mainz am Rhein: Verlag Philipp von Zabern.

Mallowan, M.E.L., and J.C. Rose. 1933. Excavations at Tall Arpachiyah. Iraq 2/1, i-xv+1-178.

Peyronel, L., C. Minniti, D. Moscone, Y. Naime, Y. Oselini, R. Perego, and A. Vacca. 2019. The Italian Archaeological Expedition in the Erbil Plain, Kurdistan Region of Iraq. Preliminary Report on the 2016-2018 Excavations at Helawa. Mesopotamia 54, 1-104.

Rothman, M. 2002. Tepe Gawra: The Evolution of a Small, Prehistoric Center in Northern Iraq. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology.

Speiser, A. 1935. Excavations at Tepe Gawra 1.

Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology.

Tobler, A. 1950. Excavations at Tepe Gawra 2

Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology.

Torcia Rigillo, M. 1999. Le ceramiche del Vicino Oriente Antico. Museo Internazionale delle Ceramiche in Faenza. Faenza: Edit Faenza.

BY ROBERT J. VIGAR

BY ROBERT J. VIGAR

THE FAN WHIRRED OVERHEAD, dispersing plumes of voluminous cigarette smoke around the small, dim room in the recesses of the Nubia Museum in Aswan. There were five of us crammed into this room. My research collaborator Yasmin and I were interviewing Mohamed, a retired engineer from the nearby island of Elephantine. We were accompanied by two museum staff members. It was late February 2020, and I was researching the relationship between archaeological sites and local communities in Aswan, trying to understand the value of archaeology to the local inhabitants.

The island of Elephantine, where Mohamed* had lived for most of his life, is home to several archaeological sites. Excavations have been ongoing for over 50 years, primarily through the German Archaeological Institute and the Swiss Institute, which maintain a dig house on the island. Given the long-term nature of excavations, and the extensive area that comprises the archaeological zone across the southern third of the island, I was keen to understand what the local population understood about the site, and what benefits they realized from its longstanding presence. Mohamed’s answer was succinct and troubling: “There is no benefit.”

For my Ph.D. research I conducted 39 interviews with local community members and archaeologists at sites around Aswan in southern Egypt, of which the island of Elephantine is a part. Mohamed’s opinion–that archaeology in the area presented little to no benefit to the local communities–was a relatively common response. This contrasted with the responses from archaeologists, the majority of whom were foreign. Several archaeologists I spoke with articulated part of their responsibility when working in Egypt was to help local communities, and that

*First names of interviewees in this article have been changed to protect their anonymity.

the primary mechanism through which they can do this is financially. “Archaeology can be a driver of economic development for local people,” stated Christopher, an excavation director at one of the archaeological sites around Aswan, in our interview in late 2020.

The naturalization of this logic, that archaeology can provide materially for local communities, is

abundant within the discourse of international funding organizations in Egypt. For example, USAID’s website states: “Egypt’s antiquities are both a part of its cultural heritage and an opportunity to create jobs and raise incomes. Since the mid-1990s, USAID has provided over $100 million in assistance to conserve monuments and masterpieces spanning from Pharaonic times to the late Ottoman period.” Indeed, their funding is often predicated upon this notion that investment in Egyptian cultural heritage will stimulate economic activity. In my interview with David, a former associate director of conservation at one of the major foreign institutions in Egypt, he argued that funding agencies were well within their rights to ensure financial support for archaeology, and that conservation was contingent upon not only academic output but also economic benefits. The exact mechanism through which this economic uplift is meant to occur is not immediately clear.

Lucía, who had worked for several years with Christopher’s archaeological excavations in Aswan when we spoke in January 2021, was unequivocal in her belief that archaeology was helpful for the local population in Aswan. When asked if it is beneficial, she responded: “Yes, definitely yes. In so many ways.” She went on to detail the ad hoc medical provision the team provides, the projects the team has funded in the village (such as a new school building), and the inflated rate of pay local men receive for working as laborers on the excavations. “They wouldn’t get as much in their usual jobs per week as they do working with the archaeologists.”

Despite these apparently altruistic provisions made by the archaeological teams, many admitted to not having much time to fully engage with the local community or to have the necessary relationships to assess their impact with this group. Christopher, the long-term archaeo -

logical site director, lamented that there is little time to develop a program of engagement and that “most of the local people have no idea what we are doing.”

Alienation, either through lack of engagement or through actively dissuading participation in archaeological endeavors, was a key theme which emerged from my interviews with local people. Fatima and Shireen, two women I met outside of the archaeological site on Sehel Island in

December 2021, attested to this. “We have no idea about the site, about the antiquities,” said Fatima. She and Shireen were selling handcrafted pieces to the few tourists who visited the site. This was the only form of economic activity the site generated for the local people, and both Fatima and Shireen confessed that outside of a brief window during the winter when tourists were more numerous, they made very little money from their efforts.

Shireen agreed with Fatima that the local community was not informed about the ‘authorized’ history of the site, what the many ancient Egyptian inscriptions meant, or why the site was important enough to erect 10-foottall concrete and steel walls around its perimeter. (Publisher's note: Such walls around an active archaeological site are often mandated by the Ministry of Antiquities as part of site management requirements.) Despite this, Shireen went on to detail how the archaeological site figures within the cultural geography of the island. Foreign archaeologists and tourists occasionally visit the site, but it is mostly void of life. The site, Shireen detailed, is a spectral space, where temporality is unstable and treacherous spirits live. “When the guard leaves at night, we see a light on the mountain [within the enclosed archaeological site], and for hours we hear strange noises. The people of the village say that Jinns (invisible creatures) guard the site from looters.” The archaeological site, to Shireen, was a malign place, which had promised much to the village (in terms of tourists and economic development) but delivered very little.

Alienation from archaeological sites in Aswan is conditioned by a contentious history. Many of the communities which live near or among archaeological sites in Aswan identify as Nubian. Traditionally Nubia occupied a territory from Dongola in the south to Aswan in the north, however, through the construction of two dams on the Nile River, over two-thirds of Nubian land was flooded between 1902 and 1964. This necessitated the forced migration of Nubian people from their land, and destruction of their

lifeways and cultural resources. During this devastating period for Nubian people, archaeologists proliferated across the landscape, excavating and documenting the archaeological sites and monuments of ancient Nubia before they were inundated by the same rising waters that destroyed modern Nubia. The juxtaposition of international organizations deploying vast resources to ‘save’ the monuments of ancient Nubia while being seemingly oblivious to the plight of current Nubian people has not been forgotten and continues to condition Nubian peoples’ responses to archaeological work. Hajji Abdelrahman, a Nubian man in his seventies whose family was forcibly removed from the village of Kalabsha in the mid-20th century, reflected upon this painful situation in an interview conducted in December 2021: “The world came to save the monuments of Nubia, but they did not make a single attempt to save the people of Nubia.”

What solutions might archaeologists use to address these historical and ongoing issues of alienation and failed economic development? Solutions are difficult, especially when the problem lies with the very practice of archaeological work in Egypt. It is undoubtedly the

case that archaeological fieldwork in Egypt can be a form of scientific colonialism, whereby Western notions of hard data predominate, hierarchies are structured around Euro-American educational qualifications, and the work of producing knowledge about Egypt takes place primarily outside of Egypt, in the corridors of Western universities. Centering this kind of practice has led, in many ways, to the continued omission and inability to engage with local communities. The model of community research and engagement the Penn Cultural Heritage Center could provide is a potential scaffolding for addressing these issues. Decentering of power in archaeological decision-making is a key aspect of this research model. Rather than Western archaeologists coming to a community and dictating the research agenda, we can encourage local communities to create or co-create the research agendas within their own spaces. This model requires Western archaeologists to ‘let go’ of their academic privilege and to reposition themselves in relation to local community concerns. I have proposed

this model to some archaeologists working in Egypt and Sudan, but none have taken it up. Negotiating local politics, labor regimes, and bureacracy are potential impediments, however, such issues exist in most spaces where archaeology takes place and has not hindered the development of more equitable forms of research than those which predominate in Egypt today.

Decentering scientific colonialism also shifts the type of past you are seeking to represent, and in so doing it opens opportunities to explore subaltern or unauthorized histories. To do so in Aswan would create a radically different archaeological research program, one that integrates rather than alienates the local communities.

Robert J. Vigar is a doctoral student in Penn’s Department of Anthropology and a graduate affiliate of the Penn Cultural Heritage Center. His research explores the history and politics of archaeology in Egypt, with a particular focus on the cultural, economic, and political impacts of archaeological practice on local communities.

Reopening a dig site in southern Iraq after a 30-year hiatus, Penn Museum researchers made two stunning discoveries in the Sumerian city of Lagash: a 5,000-year-old tavern that served up dinner and drinks, and a sediment core that holds answers to ecological secrets for 20,000 years of history. The Lagash Archaeological Project analyzes their results with cutting-edge technology such as UAV drone photography, magnetometry, and geoscience, revealing the complex interplay between culture, society, and the environment. Along the way, the team works closely with the local community to improve their everyday lives and connect them to the stories of the people who came before them.

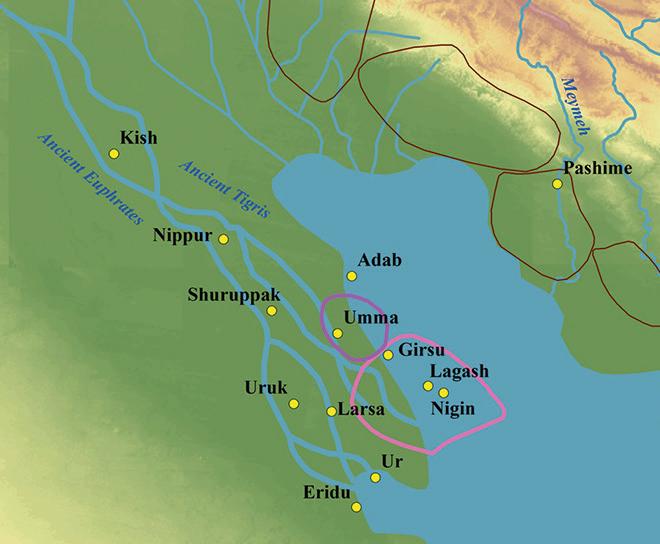

CITIES FIRST APPEARED, the Bible tells us, in southern Mesopotamia. Beyond such received knowledge, archaeologists and anthropologists have thought long and hard about why, how, and when this profound change in social organization took place in what was a verdant but precarious environment. Early explorations focused on the large sites of Nippur, Ur, Uruk, Telloh (Girsu), and Eridu watered by the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. Investigations focused almost exclusively on monumental structures, finding evidence for the origins of writing, monumental architecture, narrative visual arts, and organized religion. Work continued during the middle of the 20th century, by both Iraqi and international archaeologists, exploring ancient Lagash, known as Tell al Hiba, as well as sites

like Fara (ancient Shurupak), and Larsa. The primary focus continued to emphasize monumental architecture, cuneiform tablets, and spectacular works of art, as well as burial grounds including the Royal Tombs of Ur, which stunned the world with unexpected treasures. Until now little attention was given to investigate why this radical transformation in social organization happened at this particular place and time. Indeed, until the 21st century, with new methods and technologies, it was not possible to do much more than speculate and hypothesize.

The first scientific exploration of Lagash was sponsored by the Metropolitan Museum of Art and New York University’s Institute of Fine Arts, led by Donald P. Hansen and Vaughn Crawford. Early finds included

three temples and a royal administrative complex. I joined Hansen for my first excavation in Iraq in 1990, shortly after I came to the Museum and the University. During that season, we continued excavations of a monumental complex dated to the early part of the Early Dynastic period. This work was cut short by political events which cascaded into almost three decades of political instability and security challenges in Iraq.

In 2018, Penn Museum got the green light to return to southern Iraq after I secured a five-year permit to resume archaeological work at Lagash. Together with the University of Cambridge, and now with the University of Pisa, the Lagash Archaeological Project has had four productive seasons of work. Building on the results of the earlier campaigns, I decided to dedicate the new work to the exploration of how the “other half” lived in the cities of ancient Sumer, looking for evidence of craft industries as well as domestic and public spaces frequented by the everyday citizens of this enormous city in ancient Mesopotamia.

The land that was once Lagash is now known as Tell al Hiba, in the Dhi Qar province of southern Iraq. It is more than 125 miles north of the city of Basra at the mouth of the Persian Gulf, but in the third millennium BCE, it was close to the mouth of the Gulf, with marshes full of fish, birds, and reeds on one side and fertile alluvial soil to the west for productive agriculture. It

also had ready access by boat to trade with resource rich communities of the Iranian plateau. Our work has shown that until the middle of the fourth millennium BCE, this region was essentially underwater, in a rapidly evolving landscape—first marine, then estuary, then delta environments—to the riverine alluvium at the turn of the third millennium. The earliest settlement was likely small and religiously significant, settled in the midst of marshes, although this is still just an unexplored hypothesis. By the beginning of the Early Dynastic period, around 2900 BCE, we know that Lagash was a large city with distinct walled neighborhoods. Lagash grew and evolved into a center of industry and agricultural wealth.

We know from texts found at Telloh that Lagash was the largest of the three cities that made up the city state also called Lagash (like an ancient version of New York, New York). The cities were strung from north to south along the “Going to Nigin” canal, which ended at the port of Guabba as it entered the Gulf. To the west of the canal were rich agricultural fields: the breadbasket of Sumer at the end of the third millennium. Every city in Sumer had its own divine resident, and every citizen— from the most powerful ruler and priest to the workers in the fields—had to care for and feed this deity. The warrior god Ningirsu, for example, was the resident god of Girsu, the religious and political capital of the city state of Lagash.

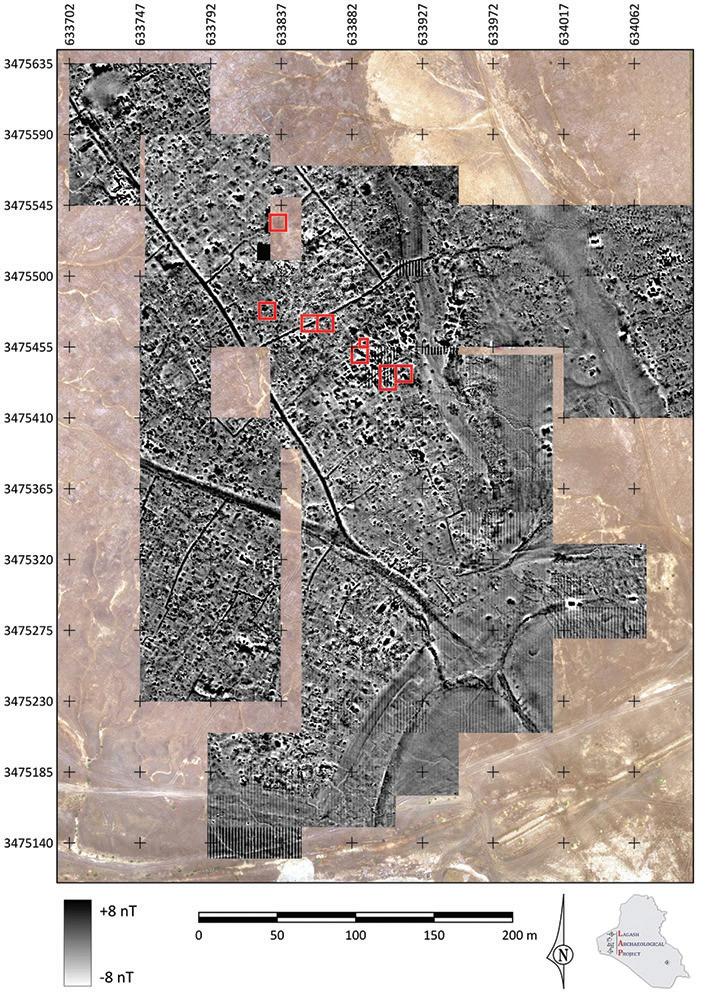

The Lagash Archaeological Project relies on a variety of methods to investigate the ways that people lived in the ancient city. The most powerful tool is remotesensing technology, including drone photography and fluxgate magnetometry, particularly useful for a large site like Lagash, which was spared the heavy overburden of later occupation that could obscure the periods we’re most interested in. When it rains, the features beneath the surface soil of the mound dry at differential rates, and as a result, features like walls and streets pop out as different colors and textures to be captured through UAV photography. This technology is augmented and enhanced at Lagash by using magnetometry, which detects naturally occurring

magnet signals of features beneath the soil. This technique allows us to “see” walls, kilns, streets, pits, open courtyards, and water features as different shapes and colors in the magnetogram. Beginning the work in 2019, we have expanded over the two seasons in 2022 to cover a large area in the southeastern sector of the city. With an expanded capacity, over the next series of campaigns we will prioritize acquiring such images over much of the site. This will allow us to identify monumental structures, as well as to characterize the built environment of different neighborhoods of the vast city: craft production zones, waterways and harbors, houses, streets, and public eateries.

Looking forward, we designed a research agenda that takes advantage of technologies and methods that weren’t available 40 years ago. Specifically, our plan is to test a hypothesis recently put forward by Prof. Monica L. Smith at the University of California Los Angeles. Smith posits that pristine urban settlement required the presence of a robust “middle class,” defined in this case as actors or communities that have economic agency who contribute to the complex economic fabric of an urban settlement. We will test this through magnetometry, as well as survey and test pits, on three or four neighborhoods across the large site. In each one we will open horizontal excavation of comparable contexts, from domestic housing to open-air public installations such as public eateries, streets, and craft production areas. Through this systematic sampling, we will determine similarities or differences and evaluate where they seem to be located on a continuum between the non-elite and elite sectors, based on what we know

through earlier excavations. We will also factor in evidence such as texts and monuments. After three decades away from Lagash, we are seeing how new data and new technology can tell new stories, and how rich an interdisciplinary venture can be, combining the tools of archaeology and anthropology as well as art history, geophysics, agricultural sciences, and beyond.

Holly Pittman is a Curator in the Near East Section and the Bok Family Professor in the Humanities in the History of Art Department. In addition to Iraq, she has excavated in Cyprus, Turkey, Syria, and Iran.

We can see many throughlines from the 3rd millennium BCE to today, including watermanagement strategies, use of marsh resources, and mud-brick architecture. The lush greenery seen here in the garden next to the dighouse dispels stereotypes of the Middle East as a barren desert. In this quiet early morning scene, water buffalo graze under a warm sky and the drooping power lines of modern Iraq. The low ancient mound lies in the far-off, hazy distance, beyond soccer fields and the pale silhouette of a treeline.

BY DAVID MULDER

BY DAVID MULDER

WHAT DOES IT TAKE to reconstruct a bustling metropolis from 5,000 years ago? A great deal of fieldwork, collaboration, and imagination, not to mention a fair bit of luck. With all of those factors in tow, Penn Museum’s Lagash Archaeological Project made a discovery that opens up a portal to the past, allowing us to envision a normal day in the life of an ancient Sumerian.

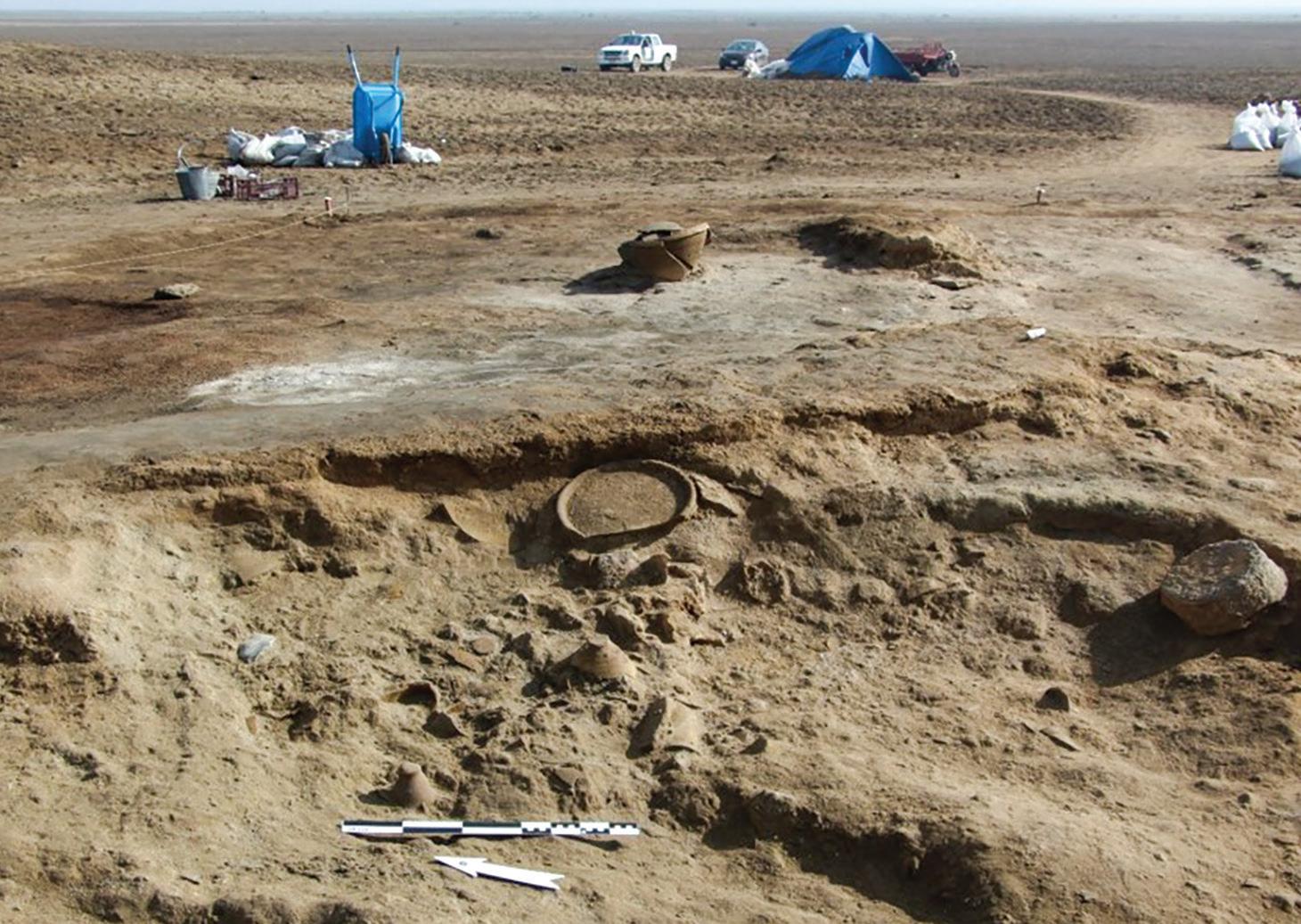

Unlike some mounds that tower steeply over their surroundings, Tell al-Hiba (the modern name for Lagash) is low and sprawling. Set against the marshes and irrigated farmland that surround it, the site now looks dry and barren. The ground is salty and cracking where it has not been disturbed by shoes, tires, and the paws of stray dogs.

There are few landmarks by which to orient oneself on the mound—spoil heaps of the old excavations, the shining green dome of a modern shrine—but Lagash of the third millennium BCE would have been navigable by a network of lanes and broad thoroughfares running to or from the city gates in the great outer wall. Within the fortified perimeter, thinner walls partitioned the city into distinct neighborhoods. One such wall revealed itself to the excavation team after a day of particularly hard rains that paused digging. Since the groundwater evaporates at different rates based on the quality of the underlying mudbrick architecture, the line of the wall became starkly visible from the surface. The team had actually been crossing over this feature every morning while walking from the parked trucks to the trenches,

not realizing we might have been retracing the steps of ancient commuters coming in and out of the city’s southeastern sector.

The surface of the area demarcated by this wall is littered with pottery sherds and pieces of slag, the byproducts of kilns and furnaces used for making ceramic and metal artifacts. It seems that in the Early Dynastic III period, around 2500–2350 BCE, this part of the city was an industrial zone for craft specialists. In two of the trenches dug last season, we found large round or oblong kilns that were filled with ashes, slag, and potsherds.

Another trench produced the corner of what seems to be another workshop building, bordering on a street and a narrow alley. In one room of this building was a basin of pure red clay full of the shells of freshwater mollusks— evidently the raw material for pottery, being soaked and refined here before it was shaped and fired in the kilns down the road.

But before this area was taken over by industrial production, the architectural remains suggest another story: It had a more residential character. We discovered a small portion of what must once have been a sizeable house not far from the pottery workshops. This house was well furnished with a plastered bench, platform, and storage facilities, including a vat sunk into the floor to keep foodstuffs cool. About 20 domed roundels of clay, just small enough to be cupped in the palm of one hand, were found on the floor of the central room. Pressed

over the mouths of storage jars, these would have acted as airtight stoppers (like ancient Tupperware, more or less). We also uncovered stone tools, beads, and clay tokens of the sort normally used in accounting. Although they speak to a different kind of labor from what we see in the kilns and workshops nearby, these artifacts are testaments to the daily work of managing and provisioning a substantial household.

Surely the inhabitants of the neighborhood would have tired of making and storing their own food from

Hundreds of bowls—still full of fish and other animal bones—fallen on to the floor of what must have been the main larder indicate a varied and hearty diet. Most of these vessels were tipped upsidedown and jumbled together in a heap, right where they had fallen nearly 5,000 years ago when the shelves collapsed.

time to time. Luckily for them, dining out appears to have been an option in ancient Lagash. Near the edge of the neighborhood, almost abutting the wall, was a public eatery with a well-stocked pantry, a huge oven, and even a sort of cooler cut into the floor with a domed covering constructed of reused potsherds. A courtyard with benches nearby allowed diners to enjoy their meals in comfort.

The patrons of this establishment ate well, it seems, provided they enjoyed a good pickled fish. We found hundreds of bowls—still full of fish and other animal bones—in what must have been the main larder, indicating a varied and hearty diet. Most of these vessels were tipped upside-down and jumbled together in a heap, right where they had fallen nearly 5,000 years ago when the shelves collapsed. Apart from this collapse, there is no indication that the building burned down or was intentionally demolished. For now we have no idea what calamity robbed these Sumerian tavern-goers of their dinner. We modern archaeologists can only be grateful that nobody ever came back to clean up the mess.

Unlike the food preparation and storage facilities excavated at other sites of the period, the Lagash “tavern” was attached to neither a major institution (a temple or a palace) nor a private residence. The quantities of food prepared inside would certainly have exceeded the requirements of any one household, but there is no

reason to think that the meal was prepared for some extraordinary occasion, like a ceremonial feast or a banquet. In this regard, it is a unique and groundbreaking discovery, as it sheds light on an aspect of early Mesopotamian urban life not reflected in most of the known textual and archaeological sources. It is likely that this building served as a gathering place for residents of the neighborhood going about their daily business, like a local pub or a canteen in any modern city. The “tavern” at Lagash offered the city-dwellers of ancient Sumer a quick meal, a cold drink, and a place to sit with friends and neighbors: in short, the same comforts that beckon us to a resturauant today.

David Mulder is a Ph.D. candidate in the History of Art Department. His research focuses on the art of early Mesopotamia, with a particular concentration on seals and seal impressions of the Early Dynastic period.

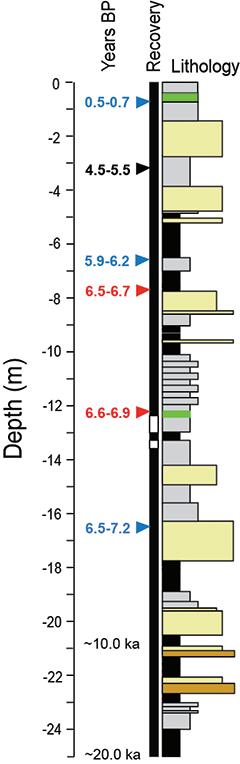

A LARGE EXPANSE of Iraq’s central floodplain, once thriving with life, now lies abandoned beyond the reach of modern agriculture. The dull beige of windswept desert stretches in all directions, marked only by the low rise of abandoned settlements, roaming dune sands and bygone canal levees. Subtle depressions shimmer white beneath the hot sun, betraying poisonous salts that choke all but the hardiest shrubs. Freshwater, the key to existence, is nowhere to be found. How did such an Ozymandian landscape, hostile to even the most intrepid among us, once harbor one of the most ancient and influential urban civilizations in history? This important question has stumped Mesopotamian archaeologists since the discipline’s founding, and it remains largely unanswered to this day.

Set within Iraq's historic urban heartland, the ancient city of Lagash presents an ideal opportunity to unravel this mystery. Looking to integrate a long-term paleoenvironmental research component into the Lagash Archaeological Project, we set out to reconstruct ecological changes at the site and across the region. To achieve such an ambitious goal, we forged a partnership with Dr. Liviu Giosan, a geophysicist at the Woods Hole Oceanographic

Institution on Cape Cod, along with geochemists at the National Ocean Sciences Accelerator Mass Spectrometry facility, also housed at Woods Hole.

We wanted to piece together clues that could shed light on the ecological transformations that rendered this once-fertile land inhospitable, with a particular focus on the environmental conditions of the 4th and 3rd millennia BCE—a momentous period of city and state development in the Lagash region. During our inaugural season we established a geoarchaeological sampling program where remote-sensing data, including drone-based imagery, allows us to target subtle variations in topography, indicative of past features like watercourses, for geoarchaeological study. The latter includes the collection of sediment samples through augering and coring at strategic locations across the low-lying and sprawling tell, as well as offsite areas. This combines the bird's-eye view of the landscape with the laser-focused precision of sediment sampling by hand auger and drill.

The initial findings reveal a fascinating, dynamic history

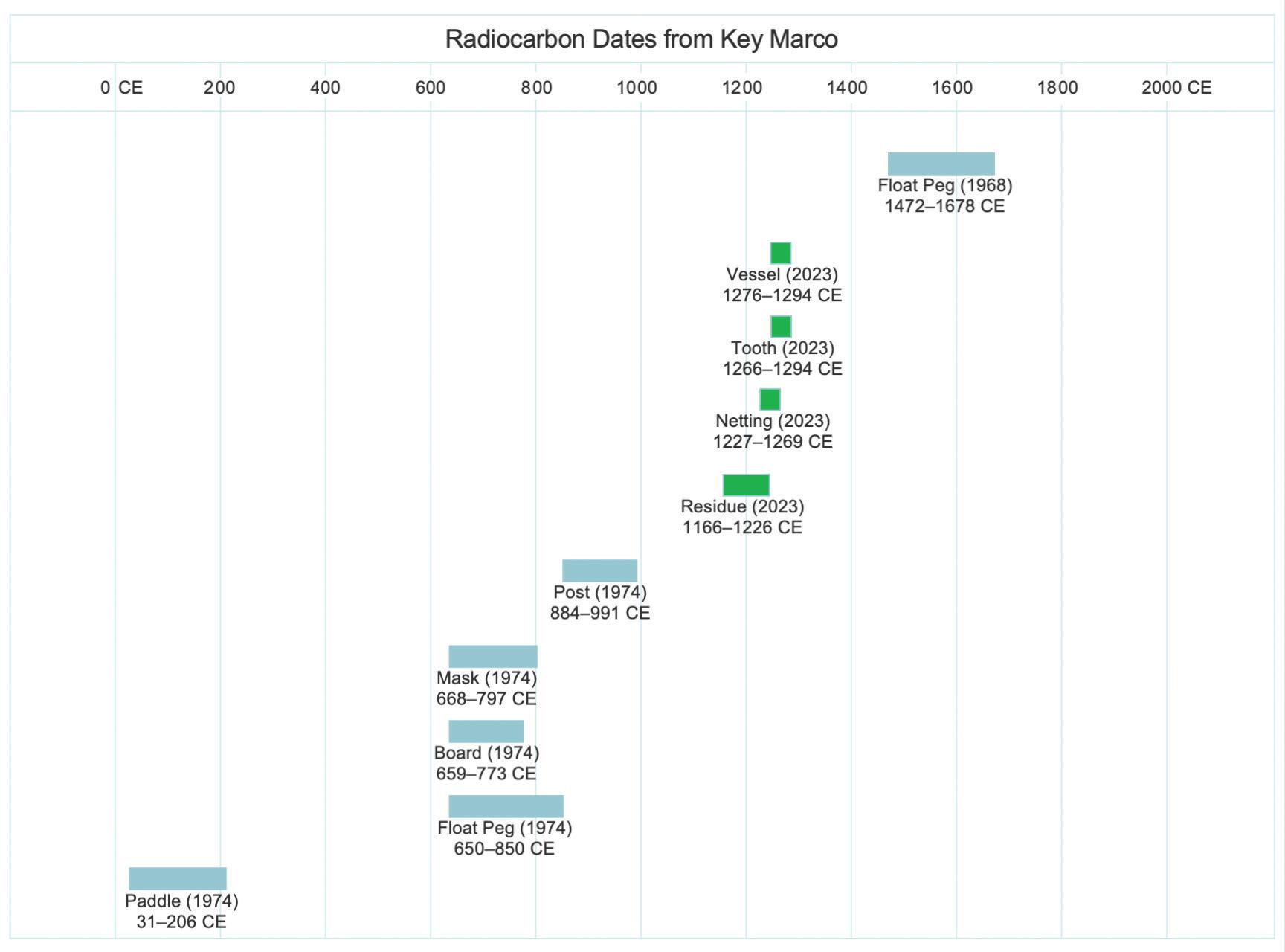

Based on the breakthrough data collected by the author, these two maps illustrate a revolution in our understanding of Sumer’s first cities: The place where Lagash was first inhabited was underwater in the 4th millennium BCE, indicating that people could not have settled there until long after the establishment of western cities on the Euphrates, like Ur and Uruk. By the time Lagash emerged from the water, around 3200 BCE, it benefited from hundreds of years of cultural development in the western cities, such as the invention of the wheel, the cuneiform writing system, and the institutions of formalized religion.

of environmental change. Analyzing the geochemistry and biology of the sediments indicate past environments, including marshes, lakes, canals, and levees. Perhaps more importantly, cutting-edge methods in radiocarbon dating have allowed us to correlate these environmental signatures with the growth and decline of the city.

Our ongoing analysis continues to fill in the picture. For example, paleontological study of the sediment samples reveal the remains of unicellular aquatic organisms called ostracods and forams. While their protective shell is all that we have, they nevertheless offer invaluable insights into the range of environmental conditions that once persisted in our study area. Different classes of organisms inhabit specific types of waters, from fresh to salt to brackish (a mixture of fresh and salt).

We can now trace the evolution of this region from a once shallow sea, when the Persian Gulf reached far north of its present position during the Middle Holocene, to an increasingly anthropogenic landscape, as the advancing

Tigris-Euphrates delta replaced seawater first with vast intertidal flats and then with nutrient-rich muds fit for agriculture.

We are also finding that as the 3rd millennium BCE progressed, the Lagash city-state found itself quite literally upstream without a paddle. First, as the former shoreline moved farther south and east through time, the Gulf’s tidal influence decreased, depriving the area of timely and economic flood waters. Next, the Tigris and Euphrates themselves began to change course, in part because of hydropolitics, with upstream power centers redirecting water away from their downstream foes, or polluting the rivers to render them useless. It’s no coincidence that the first recorded war in history was a dispute over water in the Lagash region, and that the city-state of Lagash ultimately fell for this reason.

Ultimately, as once-abundant freshwater sources gradually declined, and the tidal powers of the Gulf disappeared, communities looked to the construction

of extensive canal networks to maintain opportunities for irrigation and transportation, a necessity for what had now become a predominantly urban lifeway. At the same time, without excess water to flush salts from the surface, the landscape’s productive potential began to drop. Marked decreases in water availability spelled impending disaster. The resulting environmental stressors would eventually contribute to the decline of many Sumerian cities, forcing populations to migrate to more favorable locales.

Our collaborative research has provided crucial insights into the complex interplay between human activity and environmental factors that shaped the rise and fall of these incredible sites. Our rigorous geoarchaeological analysis has only begun to unravel the intricate tapestry of ecological changes that transformed the once-prosperous floodplain into the desolate desert we see today. Moreover, the implications of our findings extend beyond understanding the environmental history of ancient Mesopotamia. As modern societies grapple with the challenges of climate change, dwindling water resources, and agricultural sustainability, lessons from the past take on new relevance. The fate of the these once-thriving urban centers in southern Iraq offers a cautionary tale about responsible water management and environmental stewardship.

Further research will continue to refine our understanding of the complex interplay between human activities, climate fluctuations, and environmental degradation at Lagash. Our Lagash Project team, in collaboration with our partners, plans to continue these paleoenvironmental investigations, expanding the scope of the project to encompass a broader geographic range and a more comprehensive array of data sources. By

combining archaeological evidence with cutting-edge scientific techniques, we hope to paint as nuanced and detailed a portrait as possible of the ecological conditions that shaped the lives of the ancient inhabitants of Mesopotamia.

In addition to the paleoenvironmental research, the Lagash Archaeological Project is investigating material evidence that can shed light on the daily lives, economy, and political structures of the ancient city. These findings, alongside our paleoenvironmental data, will contribute to a more holistic understanding of the complex and interrelated factors behind the rise and fall of one of the world's first cities.

We hope that the interdisciplinary nature of the Lagash Archaeological Project, blending archaeology with geoscience, serves as a model for future research in the region. As we continue to investigate humanlandscape interactions, we are reminded of the timeless adage that the past is a foreign country. The lessons we learn can help guide us as we navigate the challenges and uncertainties of our own rapidly changing world. This journey, far from being a mere academic exercise, holds one key to understanding the interplay between culture, society, and the environment, and may ultimately help shape a more sustainable and resilient future for Iraq, a place that finds itself once again at the brink of environmental collapse.

Reed Goodman earned his Ph.D. in 2023 while researching the relationship between social institutions and waterscapes in southern Mesopotamia. His work combines art history with high-tech data from remotesensing and geoarchaeology to look at the rise of the city-state.

SINCE THE 1980s, archaeological work in southern Mesopotamia has been challenged by waves of political instability, economic sanctions, and armed conflict. Under such conditions, only brief investigations or survey work could occur, and these decades of unrest gutted the highly professional and active archaeological community. These specialists were based both in universities and in the State Board of Antiquities and Heritage, the Ministry of Culture and Tourism department that oversees the myriad cultural heritage projects in Iraq.

Then the tide began to turn. Around 2017, after security was reestablished in the South, Iraqi and international expeditions began to return to the heartland of cities in the southern alluvium of Mesopotamia. This was exciting news for the Penn Museum, which had been

active in southern Iraq before World War II. Work at the site of Nippur had seeded the earliest collections of the Museum, and the most notable Mesopotamian excavations were at Ur, through joint excavation with the British Museum led by Sir Leonard Woolley.

From 1922 until 1934, Woolley ran an ambitious investigation of the Temple Precinct of Nanna. There was of course the famous Royal Tombs of Ur, but also the Ziggurat and more Royal Tombs of the Ur III kings. As with Nippur—and following the practice of partage with the Iraqi government—one quarter of the nonunique materials from those excavations came to the Penn Museum, and are now the core of the new Middle East Gallery, Journey to the City

Returning to Iraq in the 21st century, the obligations and the commitments of foreign expeditions are different from those under which Woolley worked. The Lagash Archaeological Project has built a commitment to train Iraqi archaeologists into its research design and

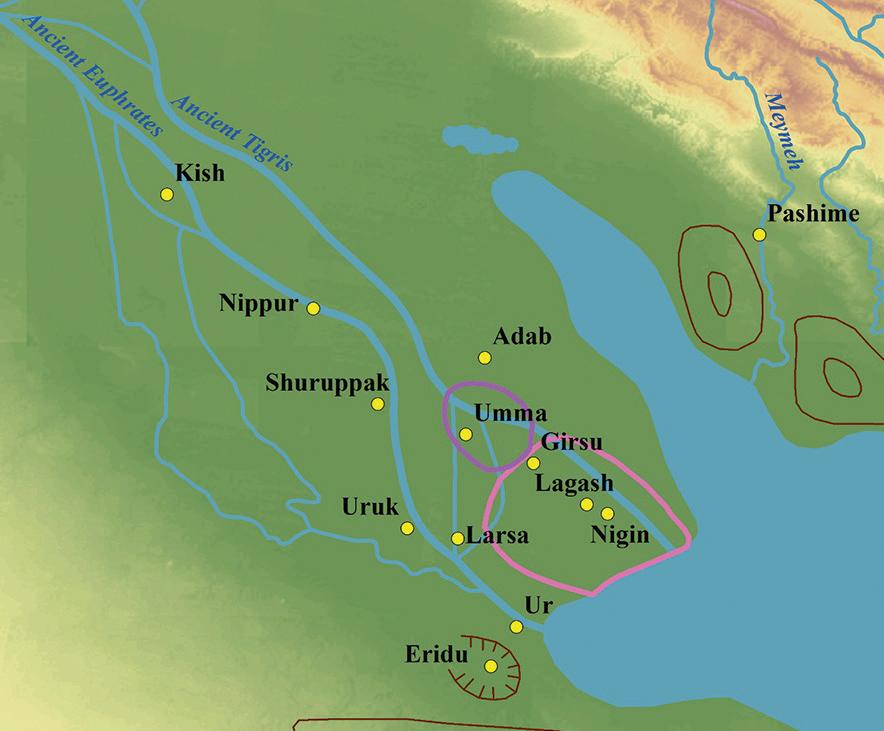

funding structure. This includes not only the multiple representatives required by the Iraqi government, but also sourcing from the community of archaeologists in Dhi Qar province who want to work with us. As a landscape archaeologist and project manager, I regularly provide training lectures on geographical information systems and mapping of landscape features.

Paul Zimmerman, a survey and remote-sensing specialist, designed his survey to be bilingual so that both Arabic and English platforms are available for recording. In the fall 2022, for three days, we welcomed employees of the Iraqi State Board of Antiquities and Heritage from Baghdad, hosting them in our house, and training them in excavation, survey, and drone photography techniques.

Beyond our commitment to building capacity in the Iraqi archaeological and cultural heritage sector, we are deeply committed to the community in which we live. Last year we met with local elders and asked how

we could best help the community. We first offered to improve one of the main roads that we drove on every day, but they told us something they needed more: to work on the primary school. With the money we contributed, they added roofs over the toilets, ran running water to the facility, and built up the fence around the school to provide more privacy. They were even able to pave the playground in front of the school, which meant that children could play at recess even if it had rained. When we return next year, we will provide educational materials in Arabic to tell the children and their parents about the historic site that they, by virtue of living here, watch over every day.

Unlike many of the ancient mounds in the region, Lagash has never been the focus of extensive looting, which was especially bad in the South during the Gulf War and the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq. Sites like Umma, to the north, are pocked with looter holes. Throughout all the instability, the people of the village of Tell al-Hiba protected the site time and time again. We want to share with them what we are learning about the people who lived in their land more than 5,000 years ago. Not just about the kings and queens and priests, but the regular people who, like them, lived in a constantly changing environment, and did their best to steward and safeguard it.

Near the beginning of the fall 2022 dig season, the Lagash team dug three small test pits to the north of the main area of excavations, close to the central part of the mound. These were meant to test whether a dried-up watercourse, clearly visible in aerial photographs of the site, had been present during the Early Dynastic heyday of the city of Lagash, or whether it had washed over the remains of an earlier occupation.

The test pits all revealed mudbrick architecture below the water-laid sediments, and a particularly surprising discovery lay in Test Pit 2: a clay nail, the sort that early Mesopotamian rulers often used to

commemorate their major construction projects. This nail bore a cuneiform inscription with the name Enanatum I of Lagash, who probably ruled sometime around 2450 BCE. Enanatum I oversaw the building of the Ibgal temple of Inana, the structure that was excavated in the southwestern area of the mound in 1968.

A grayish layer of sediment just above this nail marked the calamitous flooding that put an end to building on this part of the site. Dating of samples through optically stimulated luminescence indicated that the flooding occurred around 2330 BCE. This date is precisely when we know from other texts that Lagash was sacked and destroyed by the invading Lugalzagesi, ruler of Uruk and Umma, and again shortly thereafter by Sargon of Akkad. Without expecting it, we had uncovered traces of Lagash’s political apogee and subsequent demise at the end of the Early Dynastic period, a crucial period in the city’s history—all encapsulated within a two-by-three meter square.

Many people and institutions have contributed to the Lagash Archaeological Project. The Penn Museum would like to thank the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the National Endowment for the Humanities, the National Science Foundation, the National Geographic Society, the Janeway Foundation, the Reickett Fund at the University of Cambridge, the University of Pisa, the Italian Office of Foreign Affairs, the University of Pennsylvania Research Foundation, the Charles K. Williams II Publication Fund, the Penn Museum Director’s Field Funds, and the Bok Family Chair in the Humanities.

In February 2023, Lynn Meskell boarded a plane to Belgium. The Penn Integrates Knowledge Professor and Penn Museum curator had been invited to speak at the NATO headquarters in Brussels. This was no ordindary day in the life of a curator, but Meskell had been tapped for her rare set of skills. NATO had summoned an international panel of scholars with expertise about cultural heritage sites. The panel was faced with an urgent question: How do we protect our world’s most historic places in the wake of rampant, catastrophic war?

From the Russian invasion of Ukraine to conflicts in Iraq, Syria, and Afghanistan, the clash of armies often leads to indiscriminate bombing of precious and sacred spaces. NATO now takes a broader view of the issue: It has begun to position the protection of heritage sites under initiatives dedicated to Human Security and the Protection of Civilians. The panel spoke directly to national delegations, military leaders, and NGOs.

Meskell got the call from Dr. Frederik Rosén, the director of the Copenhagen-based Nordic Center for Cultural Heritage & Armed Conflict. Rosén and his team have been working with NATO around cultural property issues for a decade. Back home in Philadelphia, Meskell continued the collaboration with Rosén and an international team of experts on matters of heritage, security, and policy at NATO, and she later went to Rome to resume dialogue and develop new research on the consequences of war for communities across the globe. She also organized a workshop at the Royal Netherlands Institute in Rome with her colleague Ankie Peterson, Cultural Property Protection Officer in the Dutch Armed Forces, to continue dialogue and develop new research on the consequences of war for communities across the globe. This work also connects to Meskell’s project about World Heritage and conflict risk, which she works on with Witold Henisz, Vice Dean and Faculty Director of the Environmental, Social, and Governance Initiative at the Wharton School.

Expedition spoke with Meskell about her time in Belgium. Why is cultural heritage and international security such a high-profile issue right now?

The recent concern with protection of cultural heritage at NATO comes in the wake of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, but it certainly follows on from conflicts in Iraq, Syria, and Afghanistan. It’s true that cultural heritage sites have been a concern for NATO operations in Libya and Kosovo, in particular World Heritage properties. And they have encountered challenges with cultural heritage in operations not led by NATO, as in the U.S. War in Iraq or the United Nations peacekeeping mission in Mali. However, it is only since 2014, with the rise of Islamic State and the perceived weaponization of sites, that NATO allies have been galvanized into action. At the same time, there have been international highlevel debates on cultural heritage and conflict. NATO recognizes that protecting people and their heritage must now to be taken into account across the spectrum of conflict, including in prevention, conflict resolution, post-conflict reconstruction, peace operations, and humanitarian assistance. I think there is finally a realization that exploiting heritage in war has direct, negative ramifications for the rise of identity politics, ethnic or cultural cleansing, and the globalization of conflict and crisis.

You’ve worked on UNESCO World Heritage in conflict since 2011. What’s the relationship between UNESCO and NATO?

Initially, I would have said, “Not a lot,” certainly not from the UNESCO side. But the more I get to understand how an emerging heritage-security nexus is developing across international bodies—from the International Criminal Court and UN Security Council to NATO—the more I see how these organizations are connected. And often that’s not in entirely functional ways. Some at NATO would consider, quite wrongly I think, that they can outsource this type of work to UNESCO and, as I’ve written about extensively, UNESCO doesn’t have the funds, capacity, or political power to get its Member States on board. Like UNESCO, NATO has an expansive bureaucracy that is slow and not always as effective as we might imagine.

Both organizations increasingly factor in heritage destruction and preservation to their respective versions of “mission success.” I’d argue, however, that UNESCO’s conventions and modes of thinking are the products of World War II, and specifically Europe’s post-war reconstruction, in both process and sentiment. They do not adequately capture contemporary events and contexts. In particular, UNESCO’s heritage conventions don’t go far enough in understanding or protecting the local heritage valued by communities.

Today we have other ways of understanding conflict and post-conflict contexts, especially in respect to the communities involved. In Brussels this February, military personnel asked how they could identify and protect those places that mattered most to local people and predict the implications of their actions on the ground. Quite simply, they need to start by by asking—rather than assuming. That’s also when I spoke about our collaboration with the Princeton-based Arab Barometer, a nonpartisan research network focused on the social, political, and economic attitudes and values of ordinary citizens in the Arab world. It is now feasible for international agencies to educate themselves as to peoples’ priorities, rather than just assume EuroAmerican preferences for UNESCO World Heritage properties, museums, and archaeological sites.

Since 1945, we have become accustomed to seeing nostrike lists issued by foreign governments, international bodies like UNESCO, and now by private heritage foundations and international experts. These lists identify the sites deemed important through the mapping of cultural heritage on foreign soil. An example: Iraq has been the subject of extensive mapping and external decision-making in the context of the Gulf War, the Iraq War, and Islamic State insurgency since 2014. While site listing and monitoring is now an accepted facet of both conservation as well as military operations and post-conflict rehabilitation, there are more equitable processes for heritage recognition. This involves garnering public opinion and community priorities, and representing a cross-section of people and faiths, within an ethical framework. When that military representative

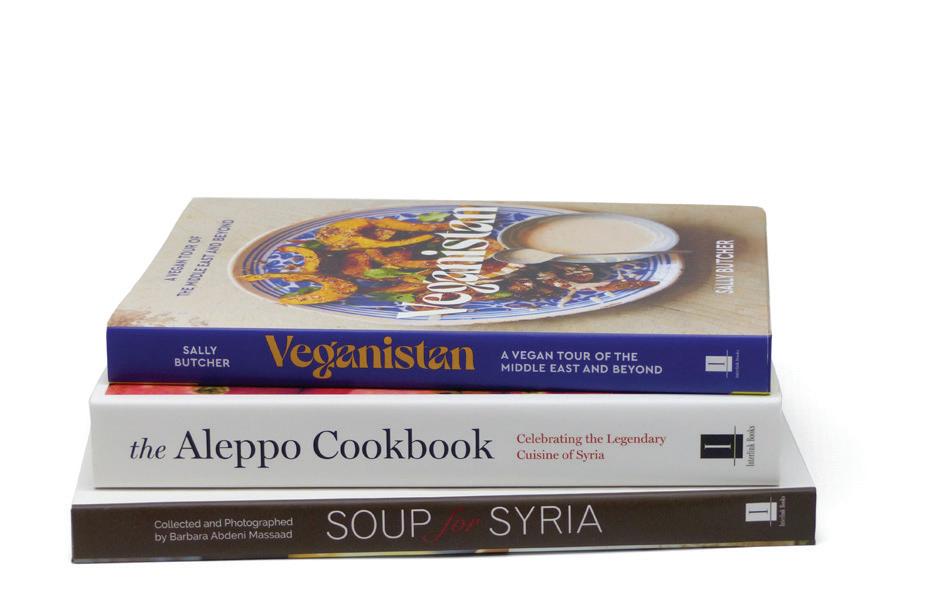

asked me how he could grasp the priorities of people, especially in nations that are unfamiliar to its operations, I offered the example of the large-scale public opinion surveys we conducted in Mosul, Iraq, and Aleppo, Syria, where we interviewed more than 3,000 people in total. Results such as these might yield greater heritage potentials not only for healing and rehabilitation, but also for delimiting the material and immaterial destruction caused during the kinetic phase of conflict.

How did your time in Brussels relate to your projects in the Middle East, your work on the Islamic State, and post-conflict reconstruction?

It provided a great opportunity to get the message out to a very different kind of audience—national delegations, military leaders, and NGOs—about issues

“there is finally a realization that exploiting heritage in war has direct, negative ramifications for the rise of identity politics, ethnic or cultural cleansing, and the globalization of conflict and crisis.”A view from NATO: Lynn Meskell (front row in the red shirt) sits with colleagues and military members in Brussels; photo courtesy of NATO.

of responsibility and accountability in what they do and how they must do better.

It’s fair to say that the city of Mosul, more than most, has had a concentration of heritage projects and agencies working there in recent years, receiving millions of international donor dollars. With my colleague Ben Isakhan and the Arab Barometer in Princeton, we surveyed local public opinion about heritage destruction and reconstruction, and assessed the degree to which that aligns with foreign-led programs.