THE MAGAZINE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA MUSEUM OF ARCHAEOLOGY AND ANTHROPOLOGY

THE MAGAZINE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA MUSEUM OF ARCHAEOLOGY AND ANTHROPOLOGY

From David O’Connor’s Storied Career to the Penn Museum’s New Galleries

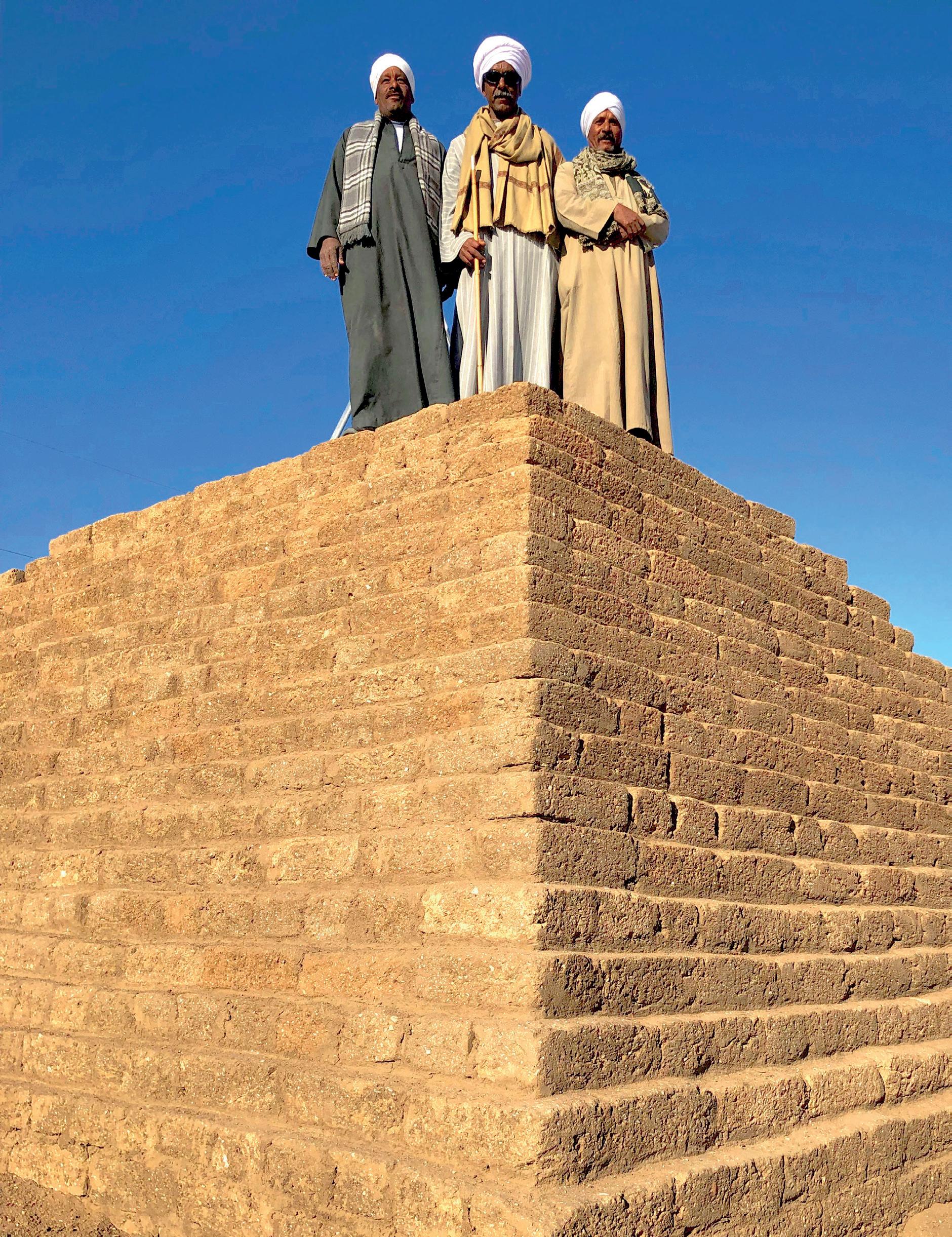

In December, I had the chance to visit the Museum’s research site at Abydos during a trip to Egypt with a group of our most loyal friends. While there, we were all enormously lucky to receive a tour from Joe and Jen Wegner, Curators in the Museum’s Egyptian Section, who helped us understand the full depth of the more than 50-year history of rich work at the site. Our work at Abydos has not only yielded important insights into Egyptian kingship and religion, it has also been a proving ground for generations of Egyptologists who have gone on to become leaders in the field. Much of this is due to the tireless efforts of the much-missed David O’Connor, to whom this issue is dedicated. The pages you are about to read contain numerous tributes by leading Egyptian scholars to Dr. O’Connor’s incredible intellectual curiosity and capacity for mentorship, as well as examples of how his life’s work continues to influence the Museum’s research and exhibitions. Our work at Abydos remains central to the Museum’s mission— as is attested by its leading role in the ongoing transformative renovations of our Ancient Egypt and Nubia Galleries, which broke ground last fall.

Of course, Abydos is only one part of the Museum’s vast research network, and Expedition readers are the first to hear about our new discoveries. In an upcoming issue, issue we’ll hear from Dr. Simon Martin, Curator of the Mexico and Central Mexico Gallery, about his latest research on the Classic Maya Collapse. Based on a series of inscriptions, including one in our own gallery, he’ll be pointing to new clues about this much debated mystery—one of the most significant in world archaeology.

Here in the Director’s office, I feel enormously privileged to be surrounded by scholars working at the leading edge of their fields, producing work with lasting relevance to the human story. One of these scholars is Joe Wegner, guest editor of this issue, and your marvelous guide through the many wonders of this ancient site, just as he was during my recent visit to Egypt. I know that your investigations into Abydos will be just as rewarding as mine.

Warm regards,

CHRISTOPHER WOODS, PH.D., WILLIAMS DIRECTOR

CHRISTOPHER WOODS, PH.D., WILLIAMS DIRECTOR

EDITOR

Quinn Russell Brown

PUBLISHER

Amanda Mitchell-Boyask

ARCHIVES AND IMAGE EDITOR

Alessandro Pezzati

GRAPHIC DESIGNERS

Colleen Connolly

Christina Jones

COPY EDITOR

Page Selinsky, Ph.D.

ACADEMIC ADVISORY BOARD

Marie-Claude Boileau, Ph.D.

Richard Leventhal, Ph.D.

Simon Martin, Ph.D.

Kathleen Morrison, Ph.D.

Lauren Ristvet, Ph.D.

C. Brian Rose, Ph.D.

Page Selinsky, Ph.D.

Stephen J. Tinney, Ph.D.

Jennifer Houser Wegner, Ph.D.

Lucy Fowler Williams, Ph.D.

CONTRIBUTORS

Jessica Bicknell

Marie-Claude Boileau, Ph.D.

Jennifer Brehm

Kris Forrest

Sarah Linn, Ph.D.

Anne Tiballi, Ph.D.

Jo Tiongson-Perez

PHOTOGRAPHY

Jennifer Chiappardi

Francine Sarin (unless noted otherwise)

INSTITUTIONAL OUTREACH MANAGER

Thomas Delfi

© The Penn Museum, 2024 Expedition® (ISSN 0014-4738) is published three times a year by the Penn Museum. Editorial inquiries should be addressed to expedition@pennmuseum.org. Inquiries regarding delivery of Expedition should be directed to membership@pennmuseum. org. Unless otherwise noted, all images are courtesy of the Penn Museum.

IN 1964, DAVID O’CONNOR, a 26-year-old Australian Ph.D. candidate in Egyptian Archaeology at the University of Cambridge, came to the University of Pennsylvania at the invitation of Museum Director, Froelich Rainey, with the goal of restarting the Museum’s excavations in Egypt. O’Connor remained at Penn for three decades, until 1995, and his work had a tremendous impact on the Museum’s Egyptian Section and its collections. This issue is dedicated to O’Connor and examines his legacy with a series of articles, many contributed by his former students and colleagues.

Arriving in Philadelphia fresh from excavations at Buhen in Sudan, O’Connor was given the enviable task of going to Egypt to identify possible sites for a long-term archaeological investigation. Due to the participation of the Pennsylvania-Yale Expedition during the early 1960s in the international salvage excavations in Lower Nubia, Penn had the opportunity to apply for work at a site within Egypt itself. After a visit to Egypt in 1965–1966 and detailed consideration of many prospective sites in both the Nile Valley and Delta, O’Connor applied for the site of Abydos, in the southern part of Middle Egypt, about 300 miles south of Cairo. One of the most important sites in the Nile Valley, with archaeological remains spanning five millennia from the Predynastic Period through Late Antiquity (ca. 4000 BCE–600 CE), Abydos offered great potential for renewed research. By 1966, O’Connor had received permission to work in North Abydos, which initiated the Pennsylvania-Yale Expedition to Abydos under the combined directorship of O’Connor and William Kelly Simpson of Yale University and the Peabody Museum of Natural History.

Upon starting work at Abydos in 1967, O’Connor built a house to

support the field staff. At that time, an abandoned house that had been used by John Garstang of the University of Liverpool still stood at Abydos. The location was a good one, situated on the floor of a low desert valley that ran through the cemeteries of Abydos. In ancient times, this sacred valley formed the processional route that led from the main town of Abydos and temple of Osiris— today called the Kom es-Sultan—to the Early Dynastic royal necropolis—the site today called Umm el-Qa’ab— where the Egyptians believed the god Osiris himself was buried. Because the ancient Egyptians kept this valley free of tombs and other buildings, a dig house could be built there without fear of intruding on or covering over ancient remains. O’Connor dismantled the Garstang house and built the Pennsylvania-Yale house on the same site. In designing the new house, O’Connor adapted his design from the dig house he had lived in during work with W.B. Emery at Buhen in Sudan. The Buhen house was, in fact, the original University of Pennsylvania house used during the Eckley Coxe Expedition to Lower Nubia in 1909–1911. It had been refurbished by the Egypt Exploration Society in the 1950s before being submerged beneath Lake Nasser in 1962. Under

O’Connor’s guidance, the spirit of the old Buhen house was fortuitously reborn at Abydos.

Large-scale excavations at Abydos were conducted in 1967–1969 focusing on the area of the Portal Temple of Ramses II. Vincent C. Pigott, a team member of the 1968 season, contributes a retrospective to this issue recalling his memorable experiences in that work. Important material from the 1960s excavations was included in a division of finds to the Penn Museum made by the Egyptian Antiquities Organization. This group of objects includes the magnificent Osiride statue (69-291), one of the iconic artifacts of the Museum’s Egyptian galleries. This statue is currently scheduled for a major new remounting in the renovated Upper Egyptian gallery, as discussed in the article by Kevin M. Cahail. Between 1970 and 1977, there was a hiatus in work at Abydos, which led O’Connor to excavate with Barry Kemp for several seasons at the 18th Dynasty palace site of Amenhotep III at Malkata on the west bank of Thebes, modern Luxor. Material from the Malkata excavations was also part of the division of finds by the Egyptian government—as discussed in this issue by Jennifer Houser Wegner—and forms the last group of archaeological material directly excavated by the Penn Museum to be accessioned into the Egyptian Section in 1981. The site of Malkata itself has turned out to be only part of an extensive zone of activity at Thebes during the reign of the 18th Dynasty king Amenhotep III, as Zahi Hawass discusses in his article on the recent discovery of the city of Tjehen-Aten After resuming work at Abydos in 1977, O’Connor continued excavations in the area of North Abydos, at that time developing a series of research projects and collaborations with Penn graduate students and others. This work included the Predynastic regional survey of Diana Patch, as well as excavations in the Kom es-Sultan by Matthew Adams, North and Middle Cemeteries by Janet Richards, and the Thutmose III chapel by MaryAnn Pouls Wegner, among others. Further to the south, in areas of Abydos not included in the original Penn concession, the Pennsylvania-Yale Expedition applied for work at the Ahmose pyramid complex (directed by Stephen Harvey) and the mortuary complex of Senwosret III (directed by Josef Wegner). Over the years these projects have continued to evolve in new

directions with other researchers becoming involved in the rich archaeology of Abydos. Excavations at South Abydos today form the focus of the Penn Museum’s work as discussed in the articles by Josef W. Wegner and Rolland Long. Renewed work in the area of the pyramid complex of Ahmose by a combined EgyptianAmerican project directed by Deborah Vischak and Ayman Damarany is shedding new light on the monuments of King Ahmose, which is also discussed by Emily Smith-Sangster. In addition to excavation, initiatives in site management and cultural heritage have become increasingly important as discussed in this issue’s articles on the new visitor building for the tomb of Seneb-Kay and the restoration of the Tetisheri pyramid chapel.

After leaving Penn in 1995, David O’Connor completed his later career as Professor of Egyptology at New York University’s (NYU) Institute of Fine Arts. There, O’Connor encouraged other research at Abydos including dissertation projects, as well as the ongoing NYU project developed by Ogden Goelet and Sameh Iskander at the Ramses II temple, as the article by Sameh Iskander

discusses. Today, archaeology at Abydos continues to thrive with a variety of ongoing field projects by both American and Egyptian missions, much of what is happening reflecting the encouragement and guidance that O’Connor brought to the site. Even after he stopped excavating in 2002, O’Connor’s particular interest in the archaeology of earliest Egypt remained an important aspect of his research as discussed in the contribution by Matthew Adams. O’Connor’s career at Abydos was capped by his 2009 book, Abydos: Egypt’s First Pharaohs and the Cult of Osiris, the first comprehensive synthesis of the archaeology and history of the site.

Even after he left the University of Pennsylvania in 1995, O’Connor maintained a strong interest in the collection and galleries. His three decades as Curator at the Penn Museum had included major exhibitions such as The Search for Ancient Egypt, and the installation of what was long the Museum’s most popular show: The Egyptian Mummy: Secrets and Science. Apart from material in the collection from his own excavations at Abydos and Malkata, O’Connor was particularly interested the Nubian collections excavated between 1907–1911 by the Coxe Expedition, as well as the magnificent remains of the Palace of Merenptah from Mit Rahina. During his time at Penn, O’Connor had a deep fascination with the Merenptah Palace and often spoke of future opportunities to reimagine that important material in the Museum’s displays. This issue closes with a brief look by Kevin M. Cahail at the Museum’s developing plans to finally reinstall the Merenptah Palace, as well as the Nubia galleries as part of the Museum’s Ancient Egypt and Nubia reinstallation project. After many years of planning, that transformative project officially entered its construction phase in 2023. As we explore in this issue of Expedition, the various areas of fieldwork in Egypt, as well as the Penn Museum’s collections and gallery initiatives, are interwoven with David O’Connor’s deep and lasting role in the Museum’s Egyptian Section.

JOSEF W. WEGNER, PH.D.

JOSEF W. WEGNER, PH.D.

The Penn Museum’s Egyptian collection spans ancient Egypt’s entire history, from the Predynastic Period (ca. 4000 BCE) through the Greco-Roman Period and into the Coptic Period (ending in the 7th century CE).

5000–3000 BCE

3000–2625 BCE

2625–2130 BCE

2250–2061 BCE

1980–1630 BCE

1630–1539 BCE

1539–1075 BCE

1075–656 BCE

664–332 BCE 332–31 BCE

Predynastic Egypt

Early Dynastic Period

DYNASTY 1-3

Old Kingdom

DYNASTY 4-8

First Intermediate Period

DYNASTY 9-11

Middle Kingdom

DYNASTY 12-14

Second Intermediate Period

DYNASTY 15-17

New Kingdom

DYNASTY 18-20

Third Intermediate Period

DYNASTY 21-25

Late Period

DYNASTY 26-31

Greco-Roman Period

DYNASTY 32-33, ROMAN AND BYZANTINE RULE

JOSEF W. WEGNER is the Penn Museum’s Project Director in Abydos. He is Professor of Egyptian Archaeology in the Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations, and Curator, Egyptian Section of the Penn Museum. He worked as a graduate student on the Penn Museum’s Ancient Nubia exhibition and is lead curator of the planned Nubia Galleries. He received his B.A. in 1989 and his Ph.D. from the University of Pennsylvania in 1996 on the topic of the development of the Osiris cult at Abydos during the Middle Kingdom. He is a specialist in the archaeology of Egypt’s Middle Kingdom (ca. 2050–1650 BCE).

VINCENT C. PIGOTT is a former Associate Director of the Penn Museum. He is a prehistorian of Southeast Asia and is Co-director of the Museum’s Thailand Archaeometallurgy Project. He is a Consulting Scholar in the Asian Section of the Museum.

SAMEH ISKANDER is Co-Director of the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World at New York University’s expedition at the Ramses II temple. He received his B.S. from Cairo University and his Ph.D from New York University in 2002. He is President Emeritus of the American Research Center in Egypt.

KEVIN M. CAHAIL is the Collections Manager of the Egyptian Collection of the Penn Museum. He holds a B.A. in Classics and Classical Archaeology from San Francisco State University and a Ph.D. in Egyptology from Penn, with his dissertation based on three seasons of excavation at tombs in South Abydos.

MATTHEW ADAMS is a Senior Research Scholar at the Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, where he has directed excavations at North Abydos since 1999. He holds a dual Ph.D. in Anthropology and Egyptology from the University of Pennsylvania.

ROLLAND X. LONG is a Ph.D. candidate in Egyptian Archaeology at the University of Pennsylvania. He has worked as a field archaeologist with the Museum’s excavations at South Abydos since 2018, and he is currently writing his dissertation on the post-Middle Kingdom habitation of Wah-Sut.

DEBORAH VISCHAK received her Ph.D. from the Institute of Fine Arts at New York University. She first worked in Abydos with David O’Connor in 1997, returning many times before co-directing the Abydos North Cemetery Project from 2018–2021. She now co-directs the Abydos South Project with Ayman Damarany, and is a research consultant with the Egyptian Section, Penn Museum.

AYMAN DAMARANY is an Inspector for the Baliana Inspectorate of the Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities in Egypt. He is an archaeologist and photographer and has worked at Abydos for many years. He has a B.A. from Sohag University and is completing an M.A. in Anthropology at Cairo University.

EMILY SMITH-SANGSTER is a Ph.D. candidate in Egyptian Archaeology at Princeton University and archaeologist for the Abydos South Project. Her dissertation examines the expression of post-mortem identity at the Ahmose North Cemetery and more broadly across Upper Egypt during the early New Kingdom.

JENNIFER HOUSER WEGNER is Curator, Egyptian Section at the Penn Museum and Adjunct Assistant Professor of Egyptology in Penn’s Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations. She is a curator for the upcoming Ancient Egypt and Nubia Galleries.

ZAHI HAWASS is Director of Excavations in the city of Amenhotep III at Thebes. He served as Director of the Giza Plateau, as the Secretary General of the Supreme Council of Antiquities, and as the first Minister of State for Antiquities. He is the author of more than 50 books on Ancient Egypt. He received his Ph.D. from the University of Pennsylvania, and has served on the Board of the Penn Museum.

David O’Connor was not only an exceptional Egyptologist, but also an extraordinary human being. He was brilliant, empathetic, and kind, with a very wonderful sense of humor. One was always happy to see him, to be in his presence. I was very fortunate that my first professional excavating experience in the Middle East was with someone like David. I arrived at the University of Pennsylvania in the autumn of 1967 with some digging experience and I think that may be why, by the second semester of my first year there, David invited me to join his 1968 winter season at Abydos. My excavation experience was limited, but it is likely he did not know that. During my junior year at Hamilton College my anthropology advisor said that if I was keen on archaeology, I really needed some digging experience. I secured a place in a field school run in southeastern Colorado, my home state. We spent the early part of the summer digging a small Pueblo ruin and then at Fort Massachusetts, built 8,000 feet above sea level in 1852

in the San Luis Valley. Among other excavation skills, I learned to survey using a theodolite on a tripod. All valuable skills, it turned out.

David took a chance on me, a newcomer in the Department of Anthropology, and took me Egypt. He

introduced me to the Middle East which then became a focus of much of my career. It is hard to imagine a better team to have first field experiences with: David and his wife Gülbün, as well as Barry Kemp, from Cambridge, and Liz Dowman, a conservator from London. Their professionalism and guidance provided me with a solid introduction to excavating in the Near East. I still treasure the friendships I formed with David and Gülbün at that time. It was David’s calm demeanor that led and reassured me through an avalanche of new experiences.

I had hardly ever flown before, let alone been out of the U.S. I remember a telegram from David instructing me on when to arrive in Cairo and to be sure to bring duty-free liquor. Cairo, with its teaming streets, was a shock—but in a good way—and I had a hotel room overlooking the Nile. David took us for drinks at the historic Shepheard’s Hotel. Soon, I was in a Land Rover for a hair-raising, front seat drive down narrow canal levees from Cairo to Sohag the provincial capital, just north of Abydos. Shortly thereafter we moved into the newly finished Abydos dig house. We were a small team, but we got on well all season.

We lived very comfortably in the new dig house that David had built near the ruins of an older house that had been used by John Garstang of the University of Liverpool. The remains of Garstang’s house were by then a cobra-filled pile of rubble we were warned to steer clear of. I learned much from David about the techniques of excavation and how to manage it well.

The vastness of Abydos was awe-inspiring with its intact temples, its temple ruins, and its imposingly massive mudbrick structures spread out across a vast sandy plain ringed by high cliffs. We hiked up those cliffs to gaze down on Petrie’s excavations of the tombs of the kings of the 1st Dynasty (ca. 3100–2900 BCE). There were also a multitude of looted tomb chambers with potsherds and mummy fragments strewn about. (I often thought of Boris Karloff ‘aka Imhotep’ in his mummy wrappings, shuffling past my window late at night.) Abydos remains the most remarkable archaeological site I have ever seen.

“The tomb was filled with about 30 or so mummified dogs. To me this was quite surprising, but David simply took it in stride having seen it all before, showing me how to best excavate it.”

David immediately put me in charge of a team of about 60 workmen with their rubber buckets and hoes clearing sandy spoil off of temple foundations. One day walking with the reis (the team’s foreman) I almost stepped on a cobra and that poor snake ended up like the much-battered one in the comic strip “B.C.” I closed out the three-month season excavating a small mudbrick tomb near the ruins of the temple of Ramses II. The tomb was filled with about 30 or so mummified dogs. To me this was quite surprising, but David simply took it in stride having seen it all before, showing me how to best excavate it. I remember sitting later in the afternoons, as well as evenings by lantern light, drawing artifacts that had turned up including demotic ostraca—with David giving me pointers on how to do so. I will add here that we had on occasion the opportunity to meet the indomitable Omm Sety, a British woman, resident at Abydos, who dedicated her life to the study of the temple of pharaoh Seti I.

In the dig house at day’s end, after a tisht-bath with heated water supplied by the house staff and poured into a large basin (the tisht), we drank Egyptian beer and settled down with good dig food. I believe our chef had cooked previously at the American Embassy in Cairo. I remember spirited debates focused on whether the tea or the milk went into the teacup first. David’s splendid sense of humor helped pass the time.

I will close with a humorous “O’Connorism” that I carry with me to this day. Frequently after one said a rather innocent or innocuous statement, he would append with: “…said the Bishop to the chorus girl.” It’s a sure-fire laugh-getter and it will always remind me of David and his brilliant, clever mind and his mild and considerate nature. That one season at Abydos was for me a life-changing, transformative experience. Thank you, David.

All images courtesy Vincent C. Pigott

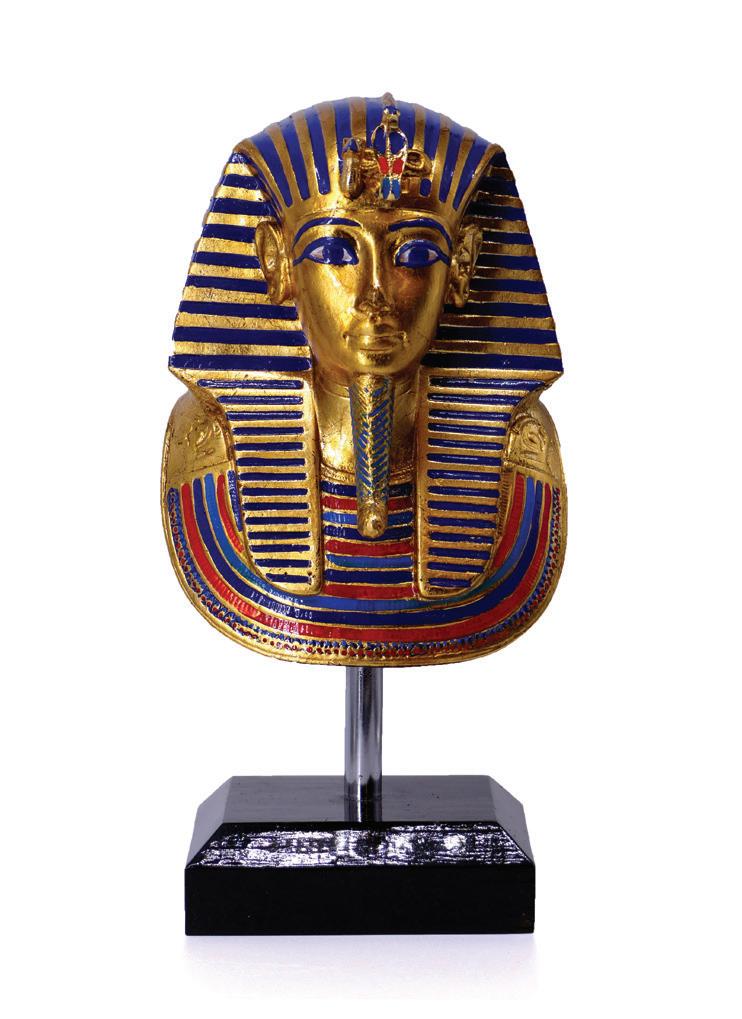

On April 15, 1967, Penn Museum Egyptologist David O’Connor unearthed fragments of a monumental statue portraying the 19th Dynasty king Ramesses II (ca. 1279–1213 BCE) at the site of Abydos. Abydos was home to the main temple of Osiris, ruler of the underworld. The tombs of Egypt’s earliest kings at the part of the site now called Umm el-Qa’ab had, by the New Kingdom, become inextricably intertwined with the mythology of Osiris. Although O’Connor didn’t know it at the time, the statue he unearthed would become one of the most beloved and iconic objects in the Penn Museum’s Egyptian collections. Generations of visitors have marveled at the statue’s brightly painted features, and probably more than a few have wondered: where did this statue come from, and what did it mean to the ancient Egyptians who created it? Though his lips seem tightly sealed, the Penn Museum’s statue of Ramesses II-as-Osiris has a story to tell and one we are still investigating. August Mariette was probably the first person to mention the statue in 1880, stating: “The remains of a colossus, representing Rameses wearing the attributes of Osiris, lie in the rubble.” For whatever reason, the statue was left untouched, but destructive digging in this area between 1880 and 1900 seems to have led to the fragments falling into a pit next to a much earlier chapel structure. These treasure hunters may have inadvertently saved this statue from ruin. In 1902–1903, William Matthew Flinders Petrie followed in Mariette’s footsteps and documented the Ramesses structure. His description and map recorded that the building’s “complete eastern part differs entirely in plan from the front of any known temple, and its ceremonial purpose must have been different from any temple ritual.” He concluded that the Ramesses building was an entrance chapel leading into the non-royal cemeteries to the south and dubbed the building the “Portal Temple.”

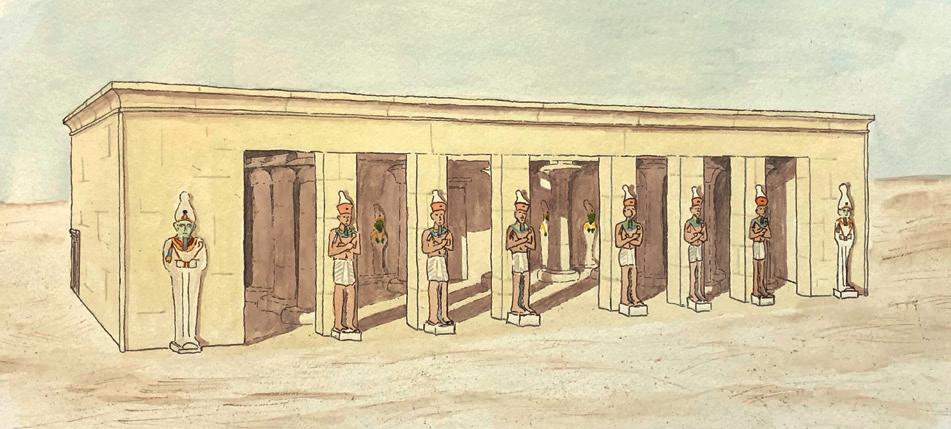

Top: Theoretical reconstruction of the engaged Osiris statues in the northeast corner of the open courtyard. Bottom: Artist’s reconstruction of the unique north facade of the “Portal Temple”; watercolor paintings by Kevin Cahail.

Following his work in the Nubian Salvage operation during the early 1960s, David O’Connor was appointed Curator of the Egyptian Section of the Penn Museum. One of his first roles for the Museum was to survey sites in Egypt to find a new location to dig. Abydos was chosen and excavations began in mid-February 1967. O’Connor’s first target was the partly exposed Ramesses Portal Temple described by both Mariette and Petrie. O’Connor himself was the first to call the building “one of the minor mysteries of Abydos.” While he set out to explore this

mystery, his excavations ultimately exposed a group of earlier Middle Kingdom (ca. 2055–1650 BCE) commemorative structures below the foundations of the Ramesses building. Called mahats in Egyptian, these cenotaphs were simple chapels where offerings to the dead could be left. Though he documented the Portal Temple in his unpublished notebooks, his interest in the Middle Kingdom structures took precedence in his research. This is not to say that the Ramesses Portal Temple was not important in its own right. Its unique structure incorporated reused stones and bricks dating to the reigns of Seti I and even as far back as the reign of Akhenaten. However, since most of the building was badly damaged, the form and function of the Ramesside structure still remain somewhat mysterious.

The preserved architecture includes an open court (Block A) surrounded by mudbrick walls, and possible remains of a pylon at the northeast. South of this are two columned balconies (Block B), each fronted by a low wall decorated with a procession of fertility gods bringing offerings to a series of deities including Banebdjedet and Thoth. The columns in these two vestibules show the king making offerings to Osiris, Isis, and other

deities whose names are not preserved. The doorway on the temple’s central axis was decorated with images of baboons whose arms were raised in a gesture of praise, alternating with the cartouches of Ramesses II. Egyptian books of the underworld tell us that these baboons played the role of gatekeepers and were also responsible for handing out divine offerings to the souls of the dead. As gatekeepers, they would face out of the building, reinforcing the idea that the front of the building may have been to the south rather than to the north.

The open courtyard at the heart of the building (Block C) would have been a unique space without parallel among known Egyptian temples. A row of columns fronted a C-shaped wall, spaced evenly within which were engaged statues of Osiris, some standing on a low molding at the bottom of the wall and others set into niches within the wall. The feet of a few of these statues were discovered by Petrie and again by O’Connor. In all cases, they represent the wrapped mummiform Osiris, but smaller in scale than the Penn Museum’s Ramesses-as-Osiris. It was in the southeastern part of this courtyard that O’Connor’s excavators came upon the remains of colossal statues near the end of his 1967 season. O’Connor recorded that very moment with the somewhat sparse description in his field notebook: “It was at this low level that we found on 15.Apr. well preserved fragments of a colossal limestone figure of a king, presumably Ramesses; the upper part of the face and the beard, shoulders (with necklace) and lower lip were found and some distance away the broken fragments of a double crown belonging to the figure.”

Much to his surprise, the Egyptian government assigned the statue fragments to the Penn Museum as part of the division of finds at the end of the 1967 season. The face, shoulders, double crown, lips, and large unwrapped feet were all transported to the Museum, slated for inclusion in the 1970 exhibition titled Abydos in Egypt and the University Museum: 1898–1969. However, when the pieces were finally brought together, there was a problem: not only did the unwrapped feet not match the form of the statue as Osiris, but the Double Crown didn’t fit on top of the statue’s head. O’Connor realized at this point that he had fragments of

two different monumental statues, one of mummiform Osiris with the king’s face, and the other representing the living Ramesses II himself with bare feet and wearing the Double Crown.

The White Crown of Rameses-as-Osiris was restored, and the fragments belonging to the statue of the king were relegated to storage. On the one hand the reassembled statue of Ramesses-as-Osiris gave a face to the mysterious Portal Temple, while on the other hand the existence of a colossal statue of the king from the same context deepened the mystery of the building, since all of the statue feet from the building’s main courtyard belong to Osiris statues. Unwrapped feet belonging to an engaged statue do exist in the columned vestibules at the Portal Temple, but both these and all the Osiris feet still in place are too small to accommodate the Penn Museum statues. They must have come from somewhere else in the building.

O’Connor interpreted the structure as a temple whose entrance faced north and theorized that its sanctuary and other important rooms at the south had simply disappeared from the site (Block D). However, another possibility is that the building did not follow the plan of a standard temple and actually faced south rather than north, a clue suggested by aspects of the building’s decoration such as the baboon figures. In this case, the southern end of the columned courtyard would have been the front of the building, which could have been decorated with monumental images of Ramesses II as the living king, alternating or bookended with statues of Osiris with the king’s face. Such an orientation would have made the building face towards the site of Umm el-Qa’ab where the Ancient Egyptians believed Osiris was buried.

Left: Overview of the Ramesses “Portal Temple” looking south with the funerary enclosure of Khasekhemwy in the background at the right; photo by David O’Connor. Above: Watercolor by Kevin Cahail of the worshipping baboons in the Block B doorway.

Though the Penn Museum’s Ramesses-as-Osiris has delighted visitors for over 50 years, it was taken off display in 2023 to undergo some much needed conservation. This work will prepare Osiris to make his triumphal return in the redesigned Ancient Egypt and Nubia galleries. While the statue will remain largely unchanged, in the newly renovated galleries he will regain his monumentality. The statue will be mounted at its original height with the body section indicated by a painted panel. The ancient artisans who carved the statue intended it to be seen at this height, and modified the king’s proportions so that it would look correct. Visitors will now be able to experience the statue as it was originally designed and explore its history through an interactive digital program.

O’Connor, D. 1967. “Abydos: A Preliminary Report of the Pennsylvania-Yale Expedition, 1967.” Expedition 10(1): 10–23.

O’Connor, D. 1968. “Fieldwork in Egypt.” Expedition 11(1): 27–30.

O’Connor, D. 1969. “Abydos and the University Museum: 1898-1969.” Expedition 12(1): 28–39.

O’Connor, D. 1976. “Abydos: The University MuseumYale University Expedition.” Expedition 21(1): 46–49.

O’Connor, D. 1985. “The “Cenotaphs” of the Middle Kingdom at Abydos.” Mélanges Gamal Eddin Mokhtar Vol. 2. Cairo: IFAO.

O’Connor, D. 2009. Abydos: Egypt’s Fist Pharaohs and the Cult of Osiris. New York: Thames and Hudson.

O’Connor, D. 2014. “The Last Partage: Dividing Finds from the 1960’s Excavations.” Expedition 56(1): 54–56.

Petrie, W.H.F. 1916. “A Cemetery Portal.” Ancient Egypt 4, 174–180.

Pouls Wegner, M. 2010. “The Construction Accounts from the ‘Portal Temple’ of Ramesses II in North Abydos.” Millions of Jubilees: Studies in Honor of David P. Silverman. Cairo: Conseil Suprême des Antiquités de l’Égypte.

Silverman, D.P. 1989. “The So-Called Portal temple of Ramesses II at Abydos.” Akten des Vierten Internationalen Ägyptologen Kongress, München 1985. Hamburg: Helmut Buske Verlag.

After excavating in the area of the “Portal Temple” in the 1960s and ‘70s, David

O’Connor turned to one of the most important aspects of ancient Abydos: its relationship to Egypt’s first kings. The work of British archaeologists in the early 20th century had shown that kings of the 1st and 2nd Dynasties (ca. 3050–2750 BCE), whose tombs were in the royal necropolis today known as Umm el-Qa’ab, were also active in another part of the site. This was less than 2 kilometers away at the edge of the Nile floodplain. Here, on an expansive desert terrace now called the “North Cemetery,” which overlooks the ancient town, were two fortress-like, walled enclosures built by the 2nd Dynasty kings Peribsen and Khasekhemwy, both of whom were buried at Umm elQa’ab. Nearby, in his final season at Abydos in 1921–22, the well-known British Egyptologist Flinders Petrie had found rectangular arrangements of small tombs (tombrectangles), each associated with the reign of a different ruler of Dynasty 1. These rulers were King Djer, King

Djet, and Queen-Regent Mer-Neith (mother of King Den). The layouts of the tombs suggested there could be additional monuments inside.

O’Connor’s initial excavations in the 1980s focused on the only example of these early royal monuments still standing: the huge mudbrick structure known locally as the Shunet el-Zebib, or the Shuneh for short. The earlier British archaeological work had produced inscriptions that showed it to have been built by King Khasekhemwy, but little was known about its actual use and subsequent history. The new work revealed that much evidence remained from the time of Khasekhemwy, as well as from two millennia later, when the monument was repurposed as a burial place of a sacred bird, the ibis, in their hundreds if not thousands.

Excavation inside one of the enigmatic tombrectangles—that belonging to King Djer of the 1st Dynasty—demonstrated conclusively that they once contained a monumental structure, a huge mudbrick walled enclosure very much like the Shuneh. On that

basis, a comparable enclosure could be confidently projected as having stood inside the nearby tombrectangle of Djet. The excavations of Petrie and one of his contemporaries, T.E. Peet, had already revealed parts of a similar structure inside the rectangle of Queen Mer-Neith.

The Shuneh has a singular significance in Egypt’s cultural heritage. Its survival was, and is, seen as essential to the integrity of the site of Abydos.

The excavations also revealed enigmatic mudbrick remains just east of the Shuneh that at the time appeared to be possibly the remains of one or more additional royal enclosures. Further work in 1991 produced perhaps the most sensational discovery of David O’Connor’s many years of fieldwork: a series of 12 long, narrow mudbrick structures, laid out in parallel and oriented east to west. Each of these structures was built to encase—or perhaps to entomb—the wooden hull of an actual boat. The boats were around 25 meters long, on average. These “boat graves” clearly belonged to the Early Dynastic Period, like the nearby royal enclosures, and must have been associated with one or more of them.

O’Connor moved on from his Penn Museum role in 1995—though he remained an emeritus curator and emeritus faculty—and continued his career as the Lila Acheson Wallace Professor of Egyptian Art and Archaeology at New York University’s Institute of Fine Arts (IFA). The first IFA-sponsored field season in 1997 essentially continued his longstanding field program. Investigation of the Shuneh continued and revealed important new information about not only its original use in the 2nd Dynasty, but also much more about its long subsequent history. This season also focused on another of Petrie’s discoveries, a royal enclosure he called the “western mastaba.” Petrie had published just three short sentences about this monument. The walls were heavily denuded and had been damaged by the construction of later shaft-tombs and offering chapels, particularly during the Middle Kingdom. This later activity destroyed the east corner of the enclosure, where one of its gateways probably once stood, and greatly complicated the search for any remaining original features inside the monument. However, most of the basic footprint of the structure survived, which showed clearly that it fit well into the architectural tradition of the other known royal enclosures. The new excavation also showed that Petrie significantly misplaced it on his site plan. Notably, the corrected position showed that the boat graves discovered in 1991 aligned almost perfectly with the west wall of the enclosure, which suggests they may have been associated with it.

The 1997 season was the last that O’Connor directed on the ground. Shortly thereafter, recognizing that his teaching and other responsibilities at IFA would not allow time for the regular fieldwork program he envisioned, O’Connor invited me to join him at IFA as Abydos Field Director. The first major initiative of our partnership was the comprehensive architectural conservation of the Shunet el-Zebib. By the 1990s, observation over many years had shown the Shuneh to be at great risk of catastrophic structural failure. Great voids and gaps in its walls, deep structural cracks, hundreds of smaller holes, and extensive undermining by animal burrows and 19th century excavation combined to threaten the survival of the monument. Since the Shuneh is the only exemplar of Egypt’s most ancient royal monumental building

tradition still standing, it has a singular significance in Egypt’s cultural heritage. Its survival was, and is, seen as essential to the integrity of the site of Abydos.

The first steps were the systematic documentation of the existing condition of the monument and a series of assessments by preservation architects and structural engineers of the nature of the problems affecting it. A comprehensive stabilization plan was then developed, one that would entail years of work, most of which was supported by a series of grants from the American Research Center in Egypt (ARCE), with funding provided by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID).

Most structural instabilities affecting the Shuneh were mitigated by replacing missing original masonry with new mudbricks. These were made locally to

specification, of the same dimensions and materials as the originals. The visible surfaces of “in-fills” were textured to reflect the irregularities of the surrounding eroded original masonry. Where the east wall was heavily undermined and had already lost nearly half its original thickness, a below-grade, hidden mudbrick footer was constructed, on top of which new masonry could be added that re-established the line of the original wall and supported the surviving original fabric. These interventions were not intended to recreate the short-lived appearance of the monument when newly constructed, but rather to preserve its existing character, the product of its nearly 5,000-year-long history. The one notable exception to this approach was in the

treatment of the enclosure’s four original gateways. Here, the gateway openings were reconstructed to varying degrees, as necessary to allow unstable areas of wall adjacent to them to be addressed.

The conservation program at the Shuneh was also an opportunity to further the archaeological investigation of the monument. In many areas, the lower parts of the walls could not be documented or assessed without excavation. The result has been transformative for understanding both its original use in Dynasty 2 and its long subsequent history. Of greatest significance, perhaps, is the extensive evidence for the performance of an offering cult on a grand scale in Khasekhemwy’s time. Huge deposits of thousands of pottery beer jars have been found outside along the south wall of the enclosure, within which were groups of bovine crania, seal impressions, and quantities of charcoal. It appears that offerings were being made inside the enclosure consisting in large part of beer, parts of cattle, and incense, presumably to or on behalf of King Khasekhemwy. This constitutes the best evidence ever recovered as to the original use of one of the Abydos royal enclosures.

In tandem with the work at the Shuneh, the broader investigation of early royal activity at Abydos continued. Northwest of the known monuments, the remains of a cluster of four additional enclosures were discovered, all accompanied by the modest subsidiary tombs of courtiers and retainers who were almost certainly sacrificed to accompany the king into the next world. Most of these tombs had been robbed in

the ancient past, but much of the original contents, as well as the remains of the occupants, were still present. Inscriptions showed that the enclosures belonged to King Aha of early Dynasty 1, predecessor of Djer, bringing this monumental building tradition—as well as the practice of sacrificial burials—back nearly to the beginning of Egyptian history.

The fieldwork in north Abydos has continued since O’Connor’s 2017 retirement from IFA. Most recently, it has focused on a large brewery complex that appears likely to have produced the huge quantities of beer used in the rituals conducted in the royal enclosures. This and additional work planned for the near future are but points along the trajectory on which O’Connor set the project nearly 40 years ago. His sense of Abydos’s unique significance in Egypt’s early history was prescient. His vision for how that could be better defined and more thoroughly understood still shapes the parameters of the project’s work today. What has been learned about

Abydos in the 1st and 2nd Dynasties in the intervening years has been transformative and will stand—rightly— as a large part of David O’Connor’s scholarly legacy.

Adams, M. 2012. “Conservation of King Khasekhemwy’s Funerary Cult Enclosure at Abydos.” Bulletin of the American Research Center in Egypt 200: 23–30.

O’Connor, D. 1989. “New Funerary Enclosures (Talbezirke) of the Early Dynastic Period at Abydos.” Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt 26: 51–86.

O’Connor, D. 1991. “Boat Graves and Pyramid Origins: New Discoveries at Abydos, Egypt.” Expedition 33(3): 5–17.

O’Connor, D. 1995. “The Earliest Royal Boat Graves.” Egyptian Archaeology 6: 3–7.

O’Connor, D. 2009. Abydos: Egypt’s First Pharaohs and the Cult of Osiris. New Aspects of Antiquity. London: Thames & Hudson.

It is an honor to dedicate this article to the memory of David O’Connor. During the time I knew him, first when I was a student and later as an Egyptologist, he was a source of rich inspiration and encouragement. Although he was not officially involved in our work on the temple of Ramses II, he provided invaluable guidance for both me and Ogden Goelet at a site he knew exceptionally well through his decades of research. Having worked on the Portal Temple of Ramses II, discussed on page 13 of this issue, O’Connor was quite interested our work on the other temple that Ramses II built at Abydos. In this article, I will present a synthesis of some of the archeological data from our recent excavations in Abydos that cover a remarkable timeframe: from the Late Old Kingdom (2300 BCE) to the Late Antique Period (750 CE).

The Ramses II temple was first cleared by August Mariette between 1861 and 1869 and published in 1881. That early excavation was limited to the temple’s main stone structure and did not include its wider precinct. No further excavation or conservation work was undertaken since Mariette’s efforts save for work in the 1990s by the Supreme Council of Antiquities. That work included just one season of excavation and miscellaneous restoration. As such, the temple has been sadly overlooked for more than 150 years while subjected to the ongoing effects of weathering and damage. To address this, in 2008, we launched a comprehensive archeological project that included architectural and epigraphic documentation under the auspices of New York University. Once the documentation phase was completed, we turned our attention to excavation and restoration of the temple and its surroundings. These excavations revealed important, multifaceted, new perspectives of the development of the temple precinct over time. Additionally, the work has resulted in the discovery of a massive, still enigmatic structure located to the local northeast of the temple and dating much earlier than the period of Ramses II.

of the temple precinct. The excavations have revealed various occupation and abandonment contexts that span the Ramesside (19th and 20th Dynasties) to the Late Roman periods. The precinct occupies an area of about 2.5 hectares delineated by a 3-meter-thick mudbrick enclosure wall that encompasses 35 magazines, various spaces, and a temple palace. The location of the temple palace is analogous to those of several other Ramesside palatial structures, referred to as temple palaces, namely at those of Seti I in Abydos and Gurna, and in western Thebes (the Ramesseum and the Merenptah and Ramses III temples) in that they are all located at the southeast of their corresponding temples. However, the interior at

Abydos is lined with limestone blocks, a feature that is absent from all the others.

I start with a discussion of the complete excavation

The term “temple palace,” which we have adopted for our structure—in contrast to an actual residential palace—was first coined by Uvo Hölscher referring to this type of structure during his excavations in the temple of Ramses III at Medinet Habu, Thebes. Although no inscriptions were found in these structures, ancient documents do refer to this type of palace linked to a temple. Papyrus Harris I, dating to the 20th Dynasty, makes a reference to a palace housed within a temple precinct, where the king addresses Amun: “I made for thee an august royal palace within it (the temple), like

the palace of Atum which is in heaven, the columns, the door jambs, and the doors of gold and the great window of appearance of fine gold.” The newly discovered temple palace at Abydos is an example of this kind of building that connected the king with temples dedicated both to the gods and to the king himself.

Within the Ramses II precinct we have come across three different areas used for unusual and unrelated animal burials. The ceramic analysis indicates that the burials are associated with stratigraphic contexts dated to the Ptolemaic Period (305–30 BCE) and Late Roman periods. The first burial we encountered was a full skeleton of a bovine laid carefully under the floor of the temple palace. The second consisted of several skulls of cattle packed inside holes in the mudbrick walls of the magazines. The third was a large deposit in one of the magazines located near the northwest corner of the precinct. It contained over 2,000 skulls of rams mixed with bones, papyri, leather shoes, and garments.

The tantalizing questions are why and from where did all the various contents of the second and third burials come from? Were they removed from some other area(s)

in Abydos, possibly to clear space for human habitation or additional ritual burials? Abydos was the site of several significant animal cemeteries from the Late Period onward. It is dotted with burials of falcons, ibises, shrews, raptors, snakes, and dogs, but no burials of rams are known at the site. Dogs may have been brought from one of the dog cemeteries in Abydos. Generally, the rams represent either Khnum, as the Ba-spirit of Osiris, who was the great god of Abydos, or Amun-Re, manifestation of Osiris and Re fused together. Although the three unrelated burials of the animal bones discussed above may represent different traditions at different times, they were undoubtedly part of the funerary rituals related to Osiris, one of the most popular gods in ancient Egypt. This also points to the fact that Ramesses II was still very much honored during the Ptolemaic and Late Roman Period, when these objects were buried in his temple precinct. That is a thousand years after his death—a long span of time, indeed.

Most of the northern part of the precinct was converted to a desert farm during the Late Roman Period by spreading a very thick mud layer (50–75 cm) produced

Within the Ramses II precinct we have come across three different areas used for unusual and unrelated animal burials. … The tantalizing questions are why and from where did all the various contents of the second and third burials come from?

from crushing the mudbricks of the magazines and enclosure wall within this area. We removed this mud layer and reused it for manufacturing new mudbrick for the restoration work of the first pylon and elsewhere. This process has been a case resurrection of bricks for the purpose of conservation and site management. Our other excavation area is located outside the temple to the local northeast, where we made a startling discovery that has major implications for our understanding of the landscape and occupation of Abydos. While working on the restoration of the foundation of the temple’s first pylon, we encountered a massive mudbrick enclosure wall dated to the late 6th Dynasty and First Intermediate Period, based on pottery analysis. It runs east-west and turns to the north with a round corner and a buttress for 160 meters. The wall is 5 meters wide, and its current height is about 2 meters. We estimate its original height to have been 10 to 15 meters, as wall heights are usually 2 to 3 times their width according to ancient Egyptian wall architectural proportions. There is a well-preserved limestone gateway through the wall. No objects or inscriptions were found, except a graffito incised on the outside jambs of the gateway bearing the hallmarks of the First Intermediate Period style. This massive wall must have enclosed key features that remain to be investigated.

enclosures can encompass temples and storage facilities, as well as centers of political power: residential and administrative buildings. Which of these aspects— or which combination is the most important in our case—can only be established by more excavation. Architecturally, there are two features to go by: the round corner and the great thickness of the wall, the reasons for which we expect will become clear as excavations expand in coming seasons at Abydos. Analysis of archeological data from different regions within Egypt points to evidence indicating that settlements flourished and expanded during the late Old Kingdom and First Intermediate periods in the south of Egypt. Textual and archaeological records from Abydos point to the existence of elite population during this period, and we may postulate that they have resided within this enclosure wall. As such, our massive structure might have served as an enclosure wall for major urban expansion at Abydos. I hope that our future excavations and research will provide further understanding of the new data obtained within the temple precinct, as well as for the wider Abydos landscape.

This type of structure, referred to as hwt in ancient Egyptian, has close parallels during Egypt’s late Old Kingdom and First Intermediate Periods (ca. 2300–2100 BCE). Examples are known from sites such as Bubastis, Edfu, Ain Asil, and Elephantine, usually in the surroundings of a sanctuary or a temple. Such hwt

Iskander, S, and O. Goelet. 2015–2021. The Temple of Ramesses II in Abydos (3 volumes). Atlanta, GA: Lockwood Press.

Iskander, S. 2023. “Preliminary Report on the 2019 and 2020 Seasons of the New York University-ISAW Project at the Temple of Ramesses II in Abydos.” Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt 59:87–112.

During an initial site survey at Abydos in 1966, David O’Connor briefly examined South Abydos: a part of the site which had not seen substantial excavations since work from 1899–1904 by the British Egypt Exploration Fund. This area of Abydos includes the royal mortuary complexes of the 12th-Dynasty king Senwosret III (ca. 1850 BCE) and the 18th-Dynasty king Ahmose (ca. 1550 BCE), the founding pharaoh of Egypt’s New Kingdom. South Abydos remained highly promising for renewed archaeological work. O’Connor mapped and photographed the landscape at that time and even made trial excavations into deposits close to the pyramid of Ahmose.

Although O’Connor initially applied to the Egyptian Antiquities Service to excavate through the entire site of Abydos, he was only granted permission to dig at the area of North Abydos where he started work in 1967. Later, in the 1990s, separate permission was granted for new work at the Ahmose complex, initially excavated by Stephen Harvey from 1993–2007 as part of the Ahmose and Testisheri Project, and now under the aegis of the

Egyptian-American ASP project (see article by Vischak and Damarany on Page # of this issue). Excavations under my direction in the Senwosret III area were initiated in 1994 and continue to this day as the Penn Museum excavations at South Abydos. Over the last two decades, numerous discoveries have come from the broader environs of the Senwosret III mortuary complex including the 2013–14 discovery of the tomb of King Seneb-Kay discussed in this issue

In the late 1990s, one of the noteworthy discoveries at South Abydos was the identification of the ancient town of Wah-Sut-Khakaure-maa-kheru-em-Abdju (usually shortened to Wah-Sut), which translates to “Enduring are the Places of Khakaure-justified-in Abydos.” This presence of a settlement site in this part of Abydos had been observed by earlier archaeologists including O’Connor. In 1902–03, working for the Egypt Exploration Fund, the Canadian archaeologist Charles Currelly excavated two large houses in this area, which he attributed to the period of King Ahmose. In the 1990s, we discovered that this site was, in fact, the town of

Wah-Sut, founded ca. 1850 BCE to house the community involved in maintaining the mortuary cult of Senwosret III. One of the first parts of the town identified was the mayoral residence, “Building A,” a complex of palatial dimensions (53 by 85 meters). Excavation of that structure, which spanned many seasons, was completed in 2015 and final publication of the results are in progress. Work in areas adjacent to the mayor’s residence revealed smaller scale houses arrayed in planned town blocks composing a substantial, state-planned urban center that had been built as a kind of satellite community or “suburb” to the main town of Abydos.

Small objects from the town excavations 2022–23: a duck amulet (upper left), ivory inlay with a baboon (upper right), a scarab (lower right), and miniature statuette of a man (lower left); photos by Ayman Damarany.

In recent seasons, we have been engaged in expanding the excavations of the Wah-Sut town site with the goal of exhaustively excavating the preserved and accessible areas of the ancient town. One of our primary areas of interest is the ways in which the town adapted to and made use of its environmental setting at the edge of the Nile floodplain. In ancient times, one of the perennial

concerns of inhabitants of the Nile Valley was the reach of the waters of the annual Nile inundation, which reliably flooded the cultivated landscape flanking the river every year between June and September. The Nile flood, called Hapy by the Egyptians and envisioned as a god of fertility, was a benefit to Egypt’s riverine ecosystem and formed the basis of agriculture in Egypt by continual replenishment of the iron-rich alluvium. However, the flood was also a logistical concern for the Egyptians. Because they built their domestic and urban sites primarily from mudbrick dug from the floodplain

In many areas of the Nile Valley, the edge of the desert was an inviting location for situating settlements. Wah-Sut is one such settlement.

itself, habitation sites needed to be situated on parts of the landscape that lay above the normal reach of the flood waters. In some parts of Egypt, high mounds developed along old river levees gradually building into huge settlement mounds called tells or koms (such as the Kom es-Sultan at North Abydos). In many areas of the Nile Valley, the edge of the desert was an inviting location for situating settlements. Wah-Sut is one such settlement.

With support from the Penn Museum’s Director’s Field Fund, the generous support of E. Jean Walker and Nina Robinson Vitow, and crucial grant support

from the American Research Center in Egypt, during our 2021–2023 seasons we completed large exposures inside the town of Wah-Sut, as well as test units in areas between the modern buildings aimed at investigating the extent of urban remains and studying the town’s relationship with its wider landscape. To the local south of the mayoral residence (Building A) are a series of additional large residences arranged in blocks of four contiguous houses (Buildings B though M). The blocks are separated by access streets forming a planned urban layout. It was two of these that Charles Currelly first exposed in 1902–03, mistakenly dating their initial construction to the New Kingdom (we now know they

belong to the Middle Kingdom). Although the houses excavated by Currelly are now mostly covered by modern buildings, others of similar design are accessible and have been a priority for excavation.

During the summer of 2022, a large exposure revealed something that we had long sought evidence for at WahSut: smaller scale houses. It has long been clear that the southern and higher elevated side of the town was dominated by the large, elite residences. We theorized that smaller houses should compose the bulk of the town and were likely located on the lower-elevated parts of the landscape directly abutting the floodplain where primary agricultural activities occurred. Indeed, one surviving late Middle Kingdom papyrus that mentions our town refers to the “fields and orchards of Wah-Sut,”

Discovered in 2023 at Wah-Sut: a granite palette (top), a husking tray (left), and a flint knife (right), photos by Ayman Damarany.

and from 2016–2020 we excavated a bakery and brewery complex close to the temple of Senwosret III that indicates extensive food production activities along the floodplain flanking Wah-Sut. To the north of the blocks of elite residences, we found that the housing blocks are half as wide and divided into houses one quarter the area of the larger ones.

This crucial sector of the town is still under investigation, and we hope to be able to trace remains down the sloping edge of the low desert into the area now covered by the modern floodplain. Over the last four millennia, through the deposition of silt, the inundation has incrementally raised the alluvium, thereby pushing the Nile floodplain outwards and upwards burying areas of the low desert that once lay beyond the reach of the flood. Preservation in and adjacent to the floodplain is much more limited than what survives at higher elevation on the desert edge. Although much of this lower status housing along the edge of the cultivation is probably destroyed, we hope to gain crucial evidence through future work to trace the full extent of the town and see how it related to its floodplain surroundings.

As part of the program to fully document the still accessible areas of Wah-Sut, during the 2023 season, we completed the exposure of two of the large houses— Buildings F and H—that lie to the south of the mayoral residence. Excavating in 10-by-10 meter squares, and gradually expanding our exposure over two months, we witnessed the structure of an ancient Egyptian neighborhood emerge. Carefully designed houses that had been formed by an architect’s blueprint had been lived in by generations of people spanning several centuries and changed in ways to suit their needs. In some areas we found doors were blocked up, and staircases added or removed. Although the town’s ruins have been severely impacted over the last four millennia, the surviving architecture and deposits provide crucial evidence on the way these households

were used by ancient Egyptians. A wide variety of artifacts—from objects of adornment to tools used in domestic production and industry—reflect the long-ago life of Wah-Sut.

As we continue to excavate and work toward reconstructing this ancient town and the life of its inhabitants, a welcome source of information are artifacts that records the identity of the people who once lived here. In past seasons, this crucial evidence has come in the form of clay sealings impressed by means of scarab and stamp seals. Seals were sometimes inscribed with hieroglyphic texts that record the names and titles of people who lived and worked at Wah-Sut. On this

Two fragments of Middle Kingdom stelae discovered in 2023. The text on the stela at the top records a man who was a “phyle director of King Khakaure.” The lower shows men (above) and women holding lotuses (below), one of whom is the “Lady of the house, Renseneb”; photo by Ayman Damarany.

basis we have been able to recover the identity of many of the mayors who once administered Wah-Sut and reconstruct a local mayoral history for the community between ca. 1850 and 1650 BCE. Many other members of the community are also recorded on seals.

Another source, though in many ways still a mysterious one, are fragments of inscribed objects—stelae, statuettes, and offering tables—that we find scattered inside and around the ancient buildings. Although these often record the names and titles of Wah-Sut’s inhabitants, it is not clear if these fragments originated from domestic shrines where people commemorated and made offerings to their deceased family members, or if some of these have been displaced from nearby chapels or shrines that lay in the town’s wider vicinity. Although many thousands of people clearly lived and died at Wah-Sut over its centuries-long history, we have yet to conclusively identify the location of the private cemeteries linked with Wah-Sut. Some of the inscribed objects suggest they may originate from ancient cemeteries in the vicinity. It is immensely rewarding to see the names and faces of these ancient people as they recorded themselves on these artifacts of commemoration. Excavations planned for coming years aim to further probe the desert and floodplain surroundings of the Wah-Sut town site to help us further understand the way this community lived and evolved over several centuries, and how this state-planned “suburb” of Abydos might have adapted to major social and political changes that occurred in Egypt’s late Middle Kingdom and Second Intermediate Period.

Wegner, J. 2000. “A Middle Kingdom Town at South Abydos,” Egyptian Archaeology 17:8–10.

Wegner, J. 2006. “Echoes of Power: the Mayor’s House of Ancient Wah-Sut.” Expedition 48(2): 31–37.

Wegner, J. 2014. “The Palatial Residence of Wah-Sut: Modeling the Mayor’s House at South Abydos,” Expedition 56(1): 24–31.

Wegner, J. 2023. “New Light on the Mayors and Ruling Family of Wah-Sut,” in F. Scalf and B. Muhs (eds.), A Master of Secrets in the Chamber of Darkness: Egyptological Studies in Honor of Robert K. Ritner. Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures. Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization 73, Chicago, 349–384.

The study of ancient Egyptian urbanism is still developing. Traditionally, temples and tombs, rather than towns and cities, have primarily helped Egyptologists learn about pharaonic civilization. The frequent location of urban sites in or adjacent to the Nile floodplain—today often buried beneath alluvial deposits or modern habitation—makes settlement evidence generally harder to access than standing monuments or tombs in the desert. Nevertheless, archaeologists in recent decades have embraced new techniques of remote sensing, geoarchaeology, and excavation methodology to expand our understanding of the nature of towns and cities. Therefore, within Egyptology, the study of urban sites and their evolution through time, along with the examination of the social, political, and economic forces that transformed them, is one of the most fruitful directions of research.

Questions pertaining to the organization and functioning of pre-industrial cities are now being broadly examined in Egyptian archaeology. One set of issues regards the developmental mechanisms that produced state-planned settlements—which are characterized by rectangular buildings, often laid in blocks, and regularly spaced streets—and how they differ from settlements that developed and grew according to more “organic” principles. Given that they are generally established for specific purposes, how long did such state-initiated “planned” settlements last? To what extent, if at all, did

An artist’s trial carving with what appears to be a rendering of part of the name of the “King of Upper and Lower Egypt, Nebpehtyre” (Ahmose); photo by Ayman Damarany.

“planned” settlements eventually develop into cities of the “organic” type?

The site of Wah-Sut was established by royal mandate in connection with the mortuary cult of King Senwosret III and excavated by the Penn Museum since the 1990s. Wah-Sut has proven to be an archetypal settlement of the state-planned kind. In recent field seasons, a major research priority has been shedding light on the changing character of Wah-Sut’s habitation across the late Middle Kingdom and Second Intermediate Period (ca. 1750–1550 BCE). Did the settlement of Wah-Sut survive the decline of the Middle Kingdom state?

Even independent of this question, the character of later, particularly New Kingdom occupation (1500–1000 BCE) in the area of South Abydos had been a longstanding issue that dogged excavations since the very beginning. In 1902, large quantities of New Kingdom artifactual material in the layers overlying the earlier Middle Kingdom structures led Canadian archaeologist Charles Currelly to understandably (but mistakenly) date several buildings in Wah-Sut to the New Kingdom. David O’Connor examined this area in 1966 and even excavated a trial cut into some of the settlement refuse but decided that other areas were more inviting.

Vast swaths of New Kingdom debris, primarily ceramics but including many other types of artifacts, are still being found over Middle Kingdom architecture to this day. The astounding quantity of this later New Kingdom debris has led members of the Penn Museum research team to repeatedly ponder its source, perhaps originating from a later, now-missing architectural phase of Wah-Sut. In close cooperation with the Abydos South Project (ASP), discussed in this issue by Vischak and Damarany on page 40, several archaeological units meant to specifically investigate the matter were finally placed between 2022–2023, around the eastern limits of Penn’s concession where the concentration of New Kingdom ceramics grows the strongest.

Exploratory units set down in the winter field season of 2022–2023 exposed several hastily constructed structures not far to the east of the known Middle Kingdom town, each with flimsy walls just one brick in width, either built over or cut into a massive New Kingdom ceramic debris layer. Several months later, the ASP excavations uncovered a sizable but enigmatic New Kingdom complex directly south (see the article by Emily Smith-Sangster on page 44), to which we believe our lightly constructed buildings are related. Research to

determine the nature of this locality is ongoing, but Penn and ASP archaeologists agree that activity from this single complex cannot be the sole source of the substantial New Kingdom pottery in the area.

We have also been scouring areas within the Middle Kingdom domestic buildings of Wah-Sut town for information on the nature of New Kingdom activity. The exact mechanisms responsible for the blanket of New Kingdom ceramic material over the site are still not entirely clear. However, in the summer of 2023 we gained further validation that the phenomenon known as sebakh-digging is one of the most important factors responsible for the seeming invisibility of later architectural phases. Sebakh (an Egyptian Arabic word referring to dug-out mud bricks from archaeological sites) is organic-rich material that was dug out of ancient settlement sites in modern times for use in agriculture. The practice was particularly prevalent during the 19th century. It appears highly likely that both architecture and organic-rich room contents were systematically dug out of the site before modern archaeological work started at South Abydos at the tail end of the 1800s.

What remains to be fully understood is how the town of Wah-Sut evolved and was altered or redeveloped when King Ahmose added his pyramid complex to the south.

In this case, substantial areas of New Kingdom settlement (forming an upper architectural layer) may have been swept away, leaving the deflated pottery deposits blanketing the site, and dumped inside the lower level of Middle Kingdom town remains. These deposits are full of informative finds reflecting the chronology of occupation as well as the continued habitation during the reign of King Nebpehtyre Ahmose. The lower, Middle Kingdom layer was also dug into and damaged by the sebakh-diggers, but its architecture survives in a better state of preservation. In this line of analysis Wah-Sut, may have been a multiphase town that grew upwards through time, forming a low kom or tell site (see the previous article in this issue). The upper levels have been substantially removed and the site flattened, leaving the lower levels at surface level with the pottery testifying to the largely vanished New Kingdom architecture.

However, excavations in 2023 have also provided evidence for a more complex pattern of settlement use than a simple two-phased superimposition of New Kingdom over Middle Kingdom town. While exposing Building H, one of the original Middle Kingdom buildings of WahSut, we found a pedestal of accumulated material that had inexplicably been left intact by the pitting of sebakh diggers around it. Embedded ceramics date to the New Kingdom. Prior to 2023, archaeological excavation at South Abydos has never revealed intact New Kingdom strata and architectural remains to accompany the plentiful New Kingdom ceramic layer. Built on and cut into this pedestal were three small brick bins of varying depth, occupying the central space that had once been a residential area for the Middle Kingdom owners of

Pottery types such as these vessels with molded heads of the goddess Hathor are useful in understanding chronology of the site. Hathor was a mortuary goddess in the Theban area, often taking the form of a cow, and she was also the goddess of love, music, and joy; photo by Ayman Damarany.

the building. Ancient residents eventually closed off an entryway in the south of the room with an insubstantial blocking wall during this later phase as well. In the transverse room south of it, we found layers of a floor also dating to the New Kingdom, though they lay at a lower level. It seems clear then, that some of the original buildings of Wah-Sut, first constructed in the 12th Dynasty (ca. 1850 BCE) were reused in the 18th Dynasty, some three centuries later.

What remains to be fully understood is how the town of Wah-Sut evolved and was altered or redeveloped when King Ahmose added his pyramid complex to the south. Despite the massive amounts of settlement debris, evidence for actual New Kingdom habitation as we have in Building H has been hard to locate. Important questions linger and are the focus of ongoing research. Was Wah-Sut abandoned and then selectively re-inhabited by people connected with the cult of Ahmose? Was there a substantial New Kingdom town that grew up on top and/or partially overlapping the Middle Kingdom town ruins, with some of the earlier, still-standing buildings repaired and reused? Was there a continued use of parts of the state-planned Middle Kingdom town all the way through the Second Intermediate Period to the redevelopment of South Abydos by King Ahmose? These and other questions are part of the ongoing study of what happened in this town, but with relevance to understanding Egyptian society more broadly. Future work will hopefully provide solutions to such questions and have the potential to contribute to our understanding of ancient Egyptian urbanism and the forces that shaped towns and cities.

Iam very happy, along with my colleague Ayman Damarany, to contribute this overview of some of our recent work in the area of the mortuary complex of King Ahmose at South Abydos. Like many of the contributors, I did my graduate work under David O’Connor’s guidance. The most transformative experience of my career was traveling with him to Abydos in 1997, where he showed me what it meant to do archaeological work in this place and with the modern communities who live in and around Abydos. That experience continues to greatly inform how the collaborative Egyptian-American Abydos South Project seeks to prioritize the protection of the site and its current and future value to the local communities.

At the southern end of Abydos, and adjacent to the archaeological sites relating to King Senwosret III, are a series of monuments constructed under King Ahmose (ca. 1539–1517 BCE), the founding pharaoh of Egypt’s 18th Dynasty. Ahmose built a series of related monuments extending across the low desert: from the

edge of the Nile Valley to the desert cliffs. From east to west and spanning a distance of more than 1 km, these include a stone-built pyramid with associated temples in honor of himself and his wife, Ahmose-Nefertari; a mudbrick pyramid in honor of his grandmother, Tetisheri; an underground tomb or cenotaph; as well as a temple, the “Terrace Temple,” built against the lower part of the desert cliffs.

The Abydos South Project, whose work is currently focusing on these monuments, was initiated by a group of Inspectors from the local Baliana and Sohag offices of the Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities. Their first season was in 2018, when they relocated the underground tomb (in all likelihood not a functional tomb, but rather a cenotaph referencing the actual tomb elsewhere) that Ahmose’s builders had cut into the bedrock deep below the low desert surface. They then continued with a second season in 2021 funded by an Antiquities Endowment Fund grant from the American Research Center in Egypt, during which they focused

on clearing the site of modern refuse and debris and building enclosure walls to further protect it. This area of the Ahmose complex had been left for many years unprotected, resulting in modern encroachment, dumping of garbage, and extensive looting. The Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities inspectors began work primarily with an eye toward rescuing the site.

During this same time, I had been working in North Abydos, but in 2021 the Egyptian team invited me to join them with the goal of expanding the archaeological program in the Ahmose area. In the spring 2022, we continued to implement their vision for protecting the site by removing all remaining garbage, completing the enclosure walls, and installing guards across the site. In our second season, from January through June of 2023, we turned our attention toward excavation and conversation work at the site. We completed excavation

in the area to the local north of the Ahmose pyramid, work that is discussed in the article by Emily SmithSangster on page 44. The second part of the season was an excavation and conservation project at the mudbrick pyramid of Queen Tetisheri, one of the more fascinating monuments on the landscape of South Abydos.

We chose to focus initially on the pyramid of Tetisheri because the monument had been subject to damaging illegal digging over the years when the site was unprotected. We felt that a focused conservation project could salvage and restore what remained of this important royal monument, make it accessible to visitors, and thereby enhance the long-term protection of the site. To tackle this project, we enlisted the help of Anthony (Tony) Crosby, a renowned expert in mudbrick architecture and conservation, who had worked with David O’Connor for many years.

The Tetisheri pyramid was built by Ahmose to honor and deify his grandmother, Queen Tetisheri. Famously, the pyramid originally housed an inscribed stela dedicated by Ahmose in her memory. The text of the stela paints an unusually intimate portrait of the royal family and discusses how Ahmose decided to build a pyramid for her at Abydos. That stela, discovered by Charles Currelly in 1902, is now in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. The pyramid itself is 24 square meters, and it is constructed using a rare building technique of internal chambers (referred to as “casemates”) that were filled with bricks and rubble. A similar technique was used to build platforms for palaces at the site of Deir el Ballas in the period just prior to Ahmose’s work here in Abydos. Therefore, we can see evidence for the development of architectural techniques by royal builders of the period. The only accessible parts of the pyramid were a long corridor entered from the local east face leading to a chapel space at the monument’s center, where the stela was originally located. The corridor had a brick-paved floor, and the walls were plastered and whitewashed.

We determined based upon the surviving walls that the slope of the pyramid was approximately 62–63 degrees or angled with a 2:1 ratio. This means that when completed, the pyramid would have risen to a height of 24 meters (78 feet). While restoring the monument to its initial height was a tempting proposition for the team,

the substantial scale of the structure put that outside of our reach. Instead, the overall goals of the project were to stabilize and protect the structure into the future, and to restore enough to make it very clear exactly how the pyramid was constructed and to some extent show how the pyramid eventually collapsed and was denuded of much of its brickwork. Important features to clarify by partial restoration were as follows: (1) the actual slope of the exterior walls, (2) the basic pyramid geometry, (3) the structural system and how it performed, and (4) showing how structural deformation occurred leading to failure and collapse of the pyramid superstructure.